Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

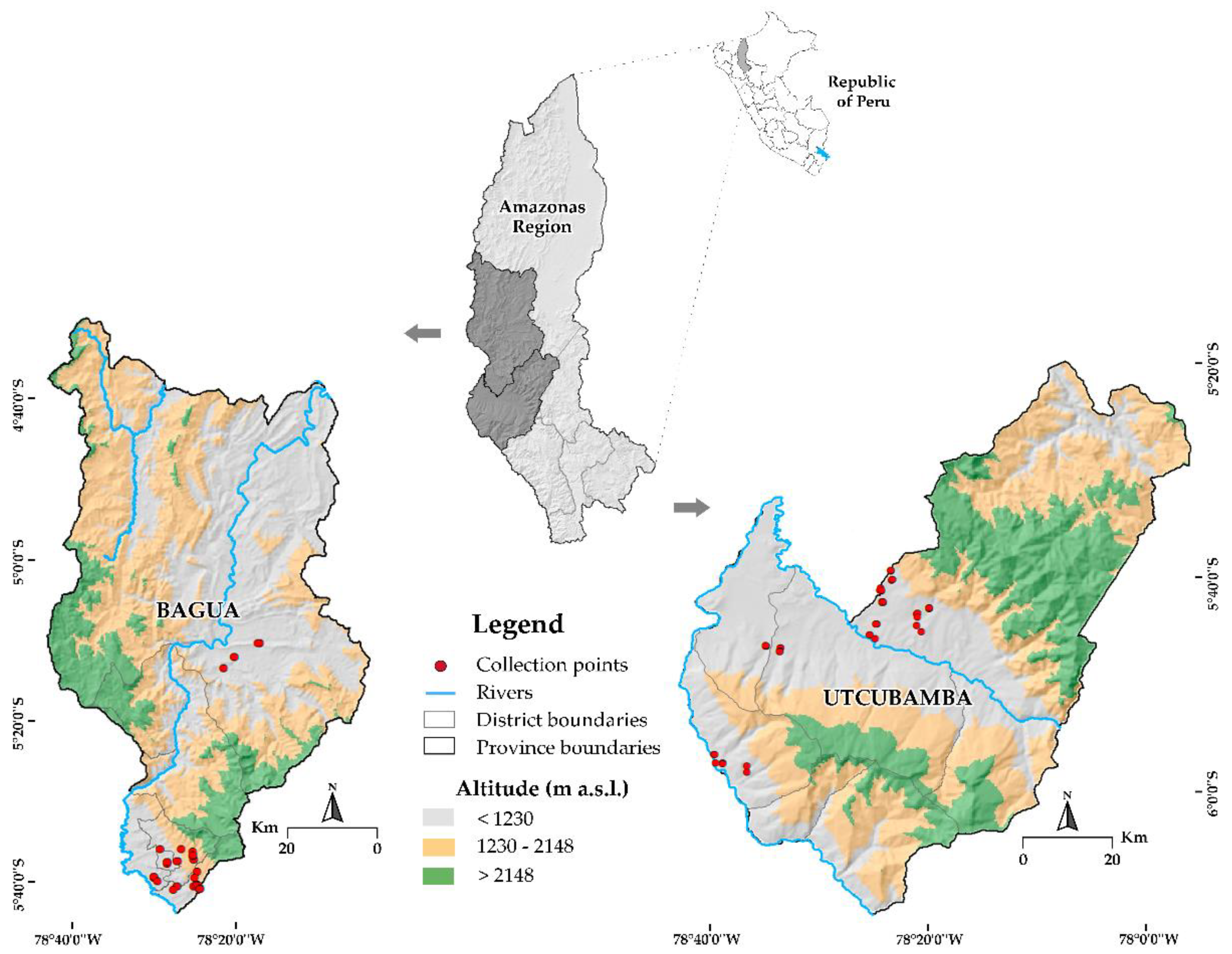

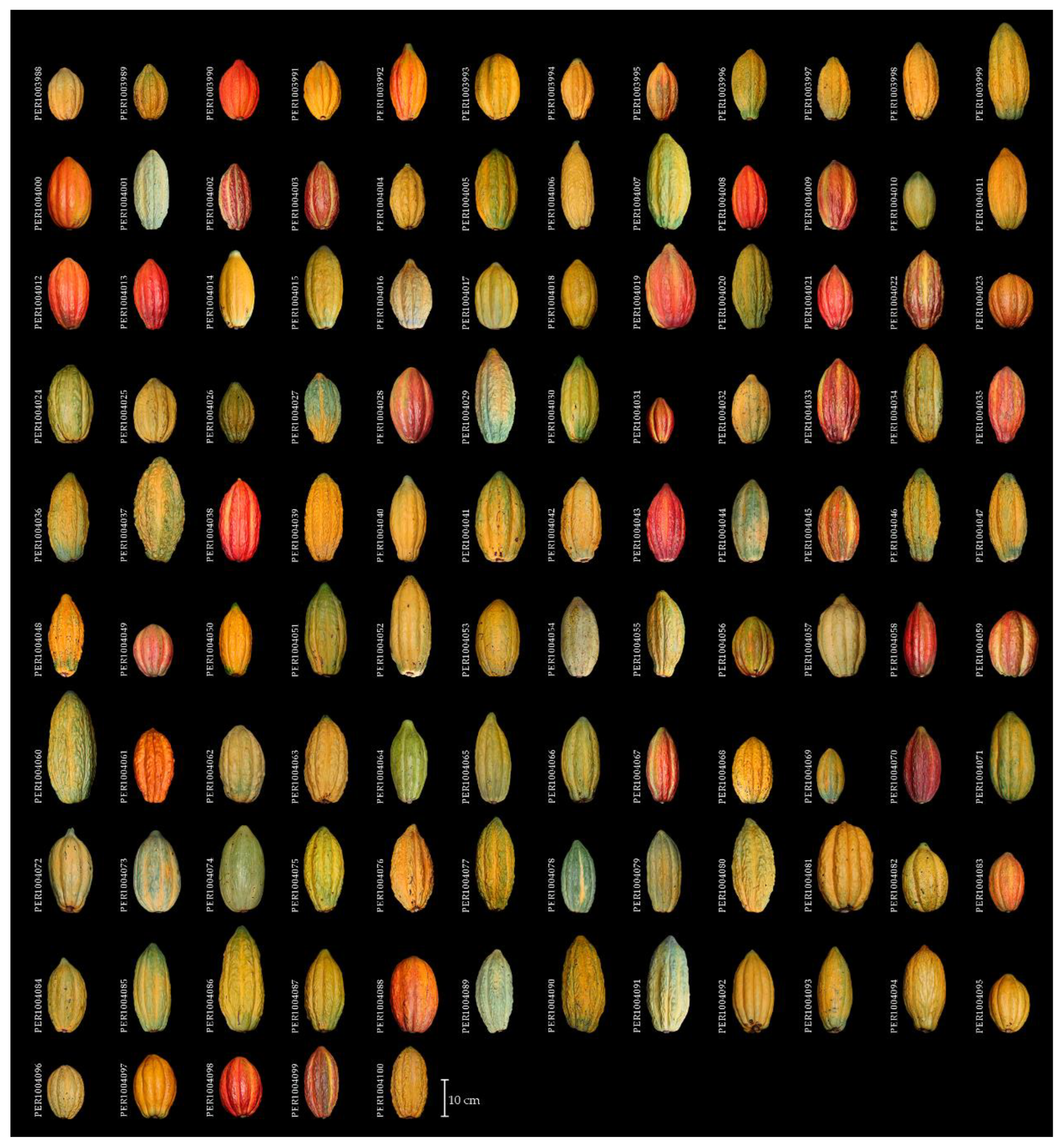

2.1. Plant Germplasm

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Study Location

2.4. Agronomic Management

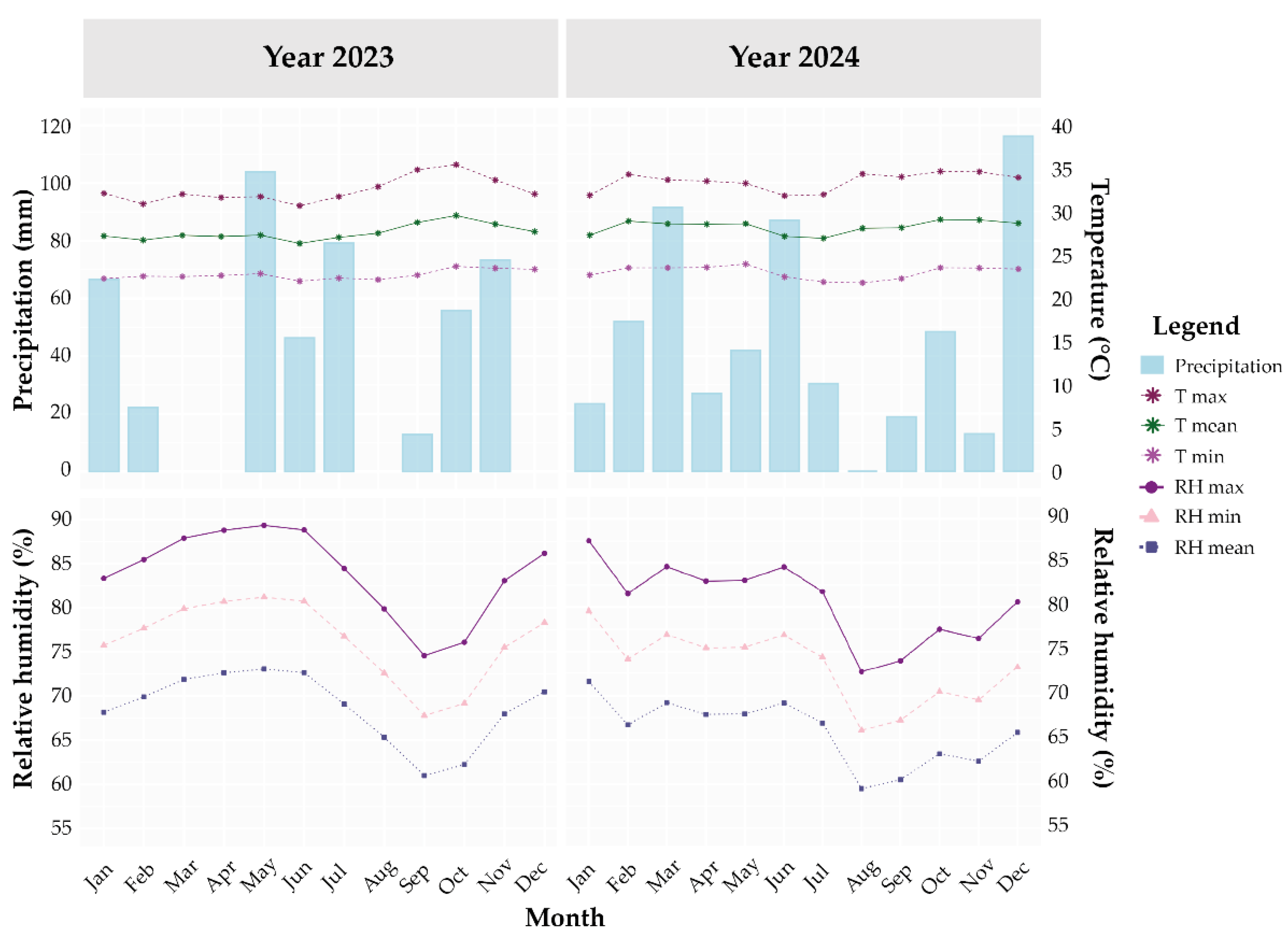

2.4. Agroecological Conditions

2.5. Agromorphological Characterization

2.5.1. Quantitative Descriptors

2.5.2. Qualitative Descriptors

| Structure | Descriptor | Acronym | Categorical Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Leaf base shape | LBS | Acute (1), Obtuse (2), Rounded (3) and Codiform (4) |

| Leaf apex shape | LAS | Apiculate (1), Acuminate (3) and Caudate (5) | |

| Young leaf color | YLC | Green (3), Brown and Red (5) | |

| Flower | Pedicel color | PC | Green (1), Reddish green (2) and Reddish (3) |

| Anthocyanin in sepals | ASe | Absent (1) and Present (2) | |

| Anthocyanin in staminodes | ASt | Absent (1) and Present (2) | |

| Anthocyanin in filament | AF | Absent (1) and Present (2) | |

| Anthocyanin in ovary | AO | Absent (1) and Present (2) | |

| Anthocyanin in ligule | AL | Absent (1) and Present (2) | |

| Fruit | Immature fruit color | IFC | Green (1), Pigmented green (2) and Red (3) |

| Mature fruit color | MFC | Yellow (1), Orange (2), Green (3) and Red (4) | |

| Fruit shape | FS | Oblong (1), Elliptic (2), Oboved (3), Rounded (4) and Ovate (5) | |

| Fruit shape | FAS | Attenuated (1), Acute (2), Obtuse (3), Rounded (4), Nipple shaped (5) and Dentate (6) | |

| Basal fruit constriction shape | BCSF | Absent (0), Slight (1), Intermediate (2) and Strong (3) | |

| Roughness of the fruit peel | RFP | Absent (0), Mild (1), Intermediate (3) and Rough (5) | |

| Seed | Seed cross-section shape | SCSS | Flattened (1), Intermediate (2) and Rounded (3) |

| Longitudinal seed shape | LSS | Oblong (1), Elliptic (2), Oval (3) and Irregular (4) | |

| Seed color | SC | White (1), Pink (2), Violet (3) and Purple (4) |

2.6. Phytochemical Characterization

2.6.1. Colorimetric Measurement, Titratable Acidity, and pH

2.6.2. Bioactive Compound Profile

2.6.3. HPLC Screening of Methylxanthines and Phenolic Compounds

2.6.4. FTIR Spectroscopy Screening

2.7. Statistical Processing

3. Results

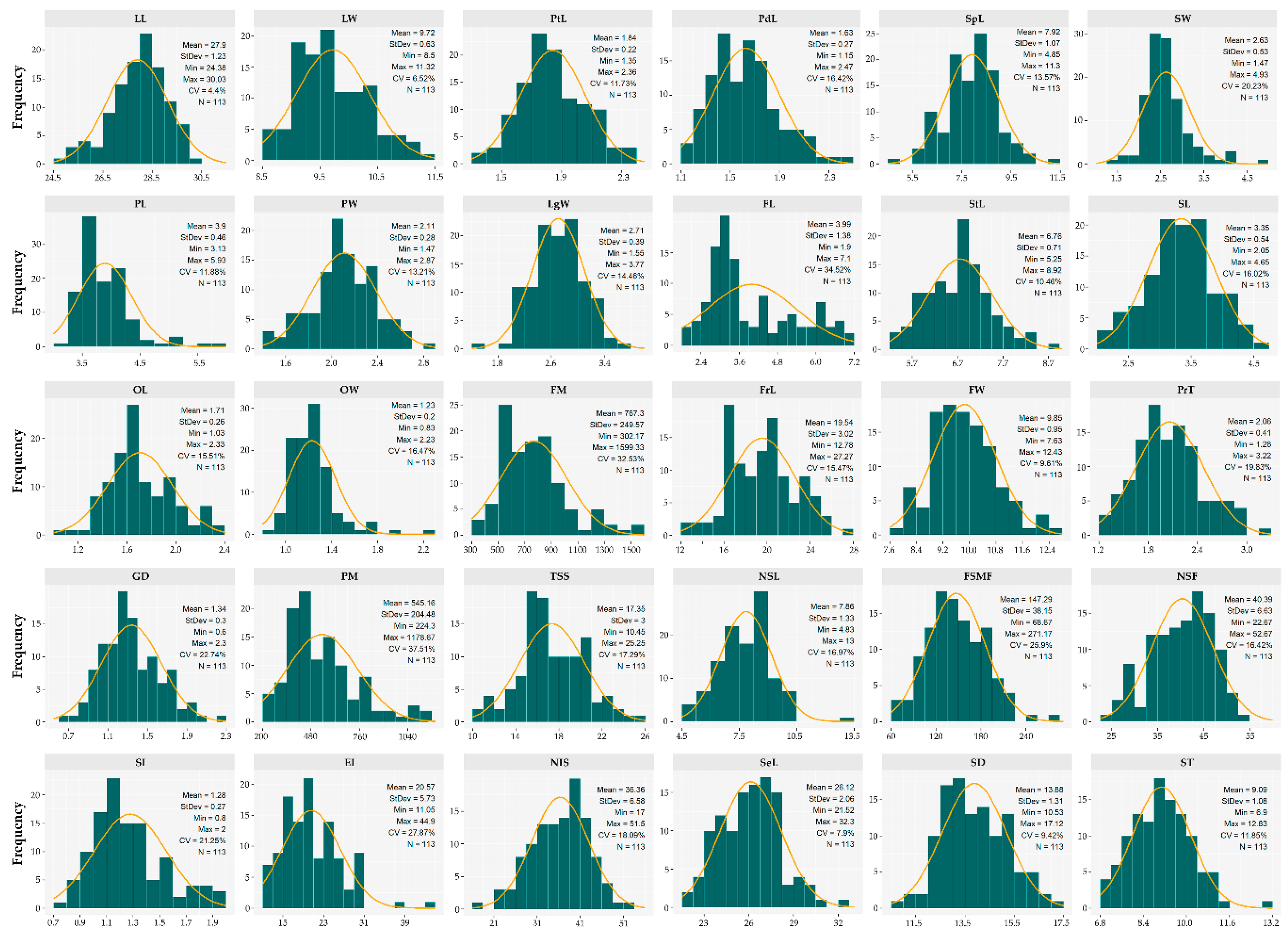

3.2. Variation Patterns in Quantitative Descriptors

3.3. Estimation of Quantitative Genetic Parameters

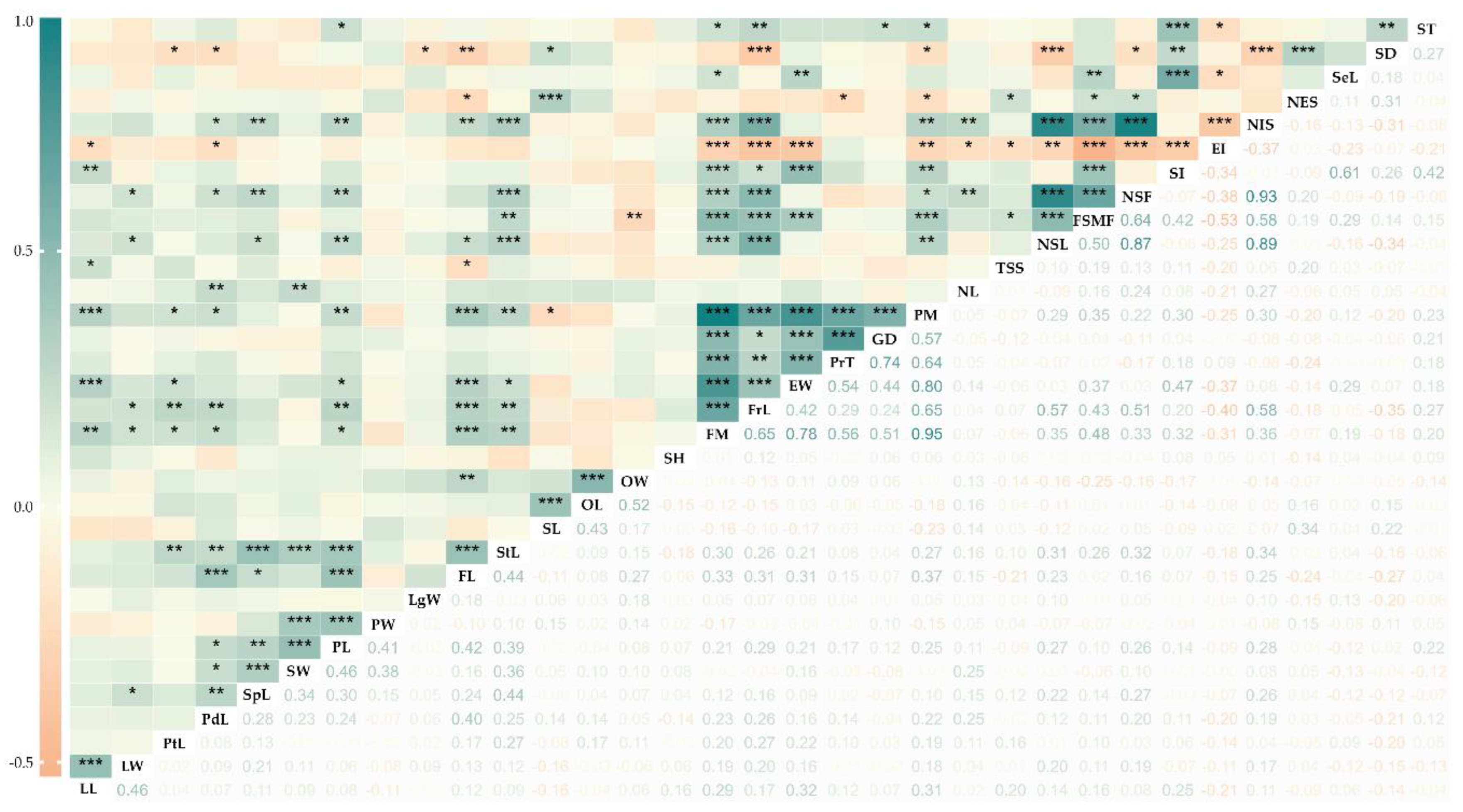

3.4. Association Analysis Among Quantitative Descriptors

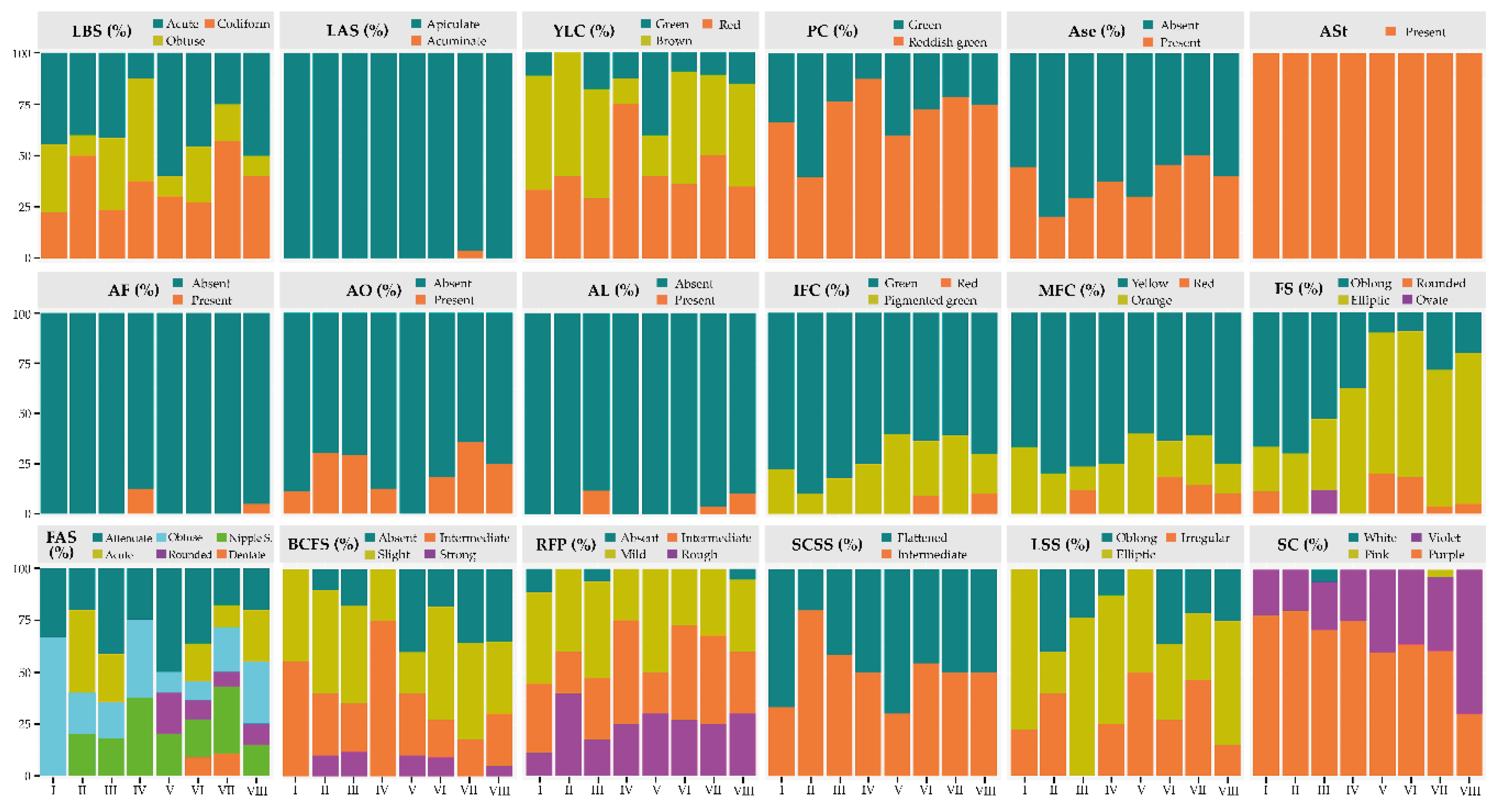

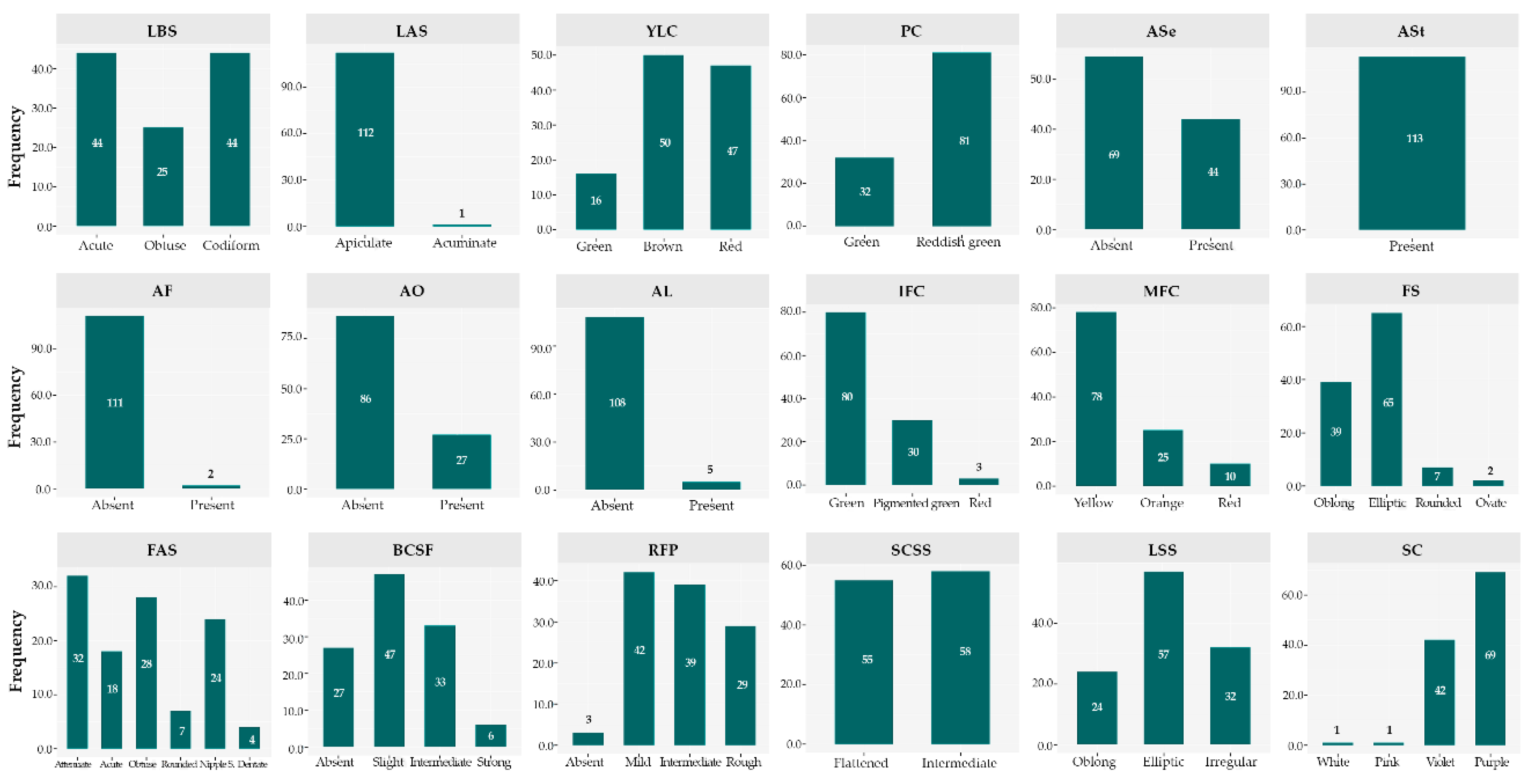

3.5. Patterns of Variation in Qualitative Descriptors

3.6. Structural Organization of Germplasm

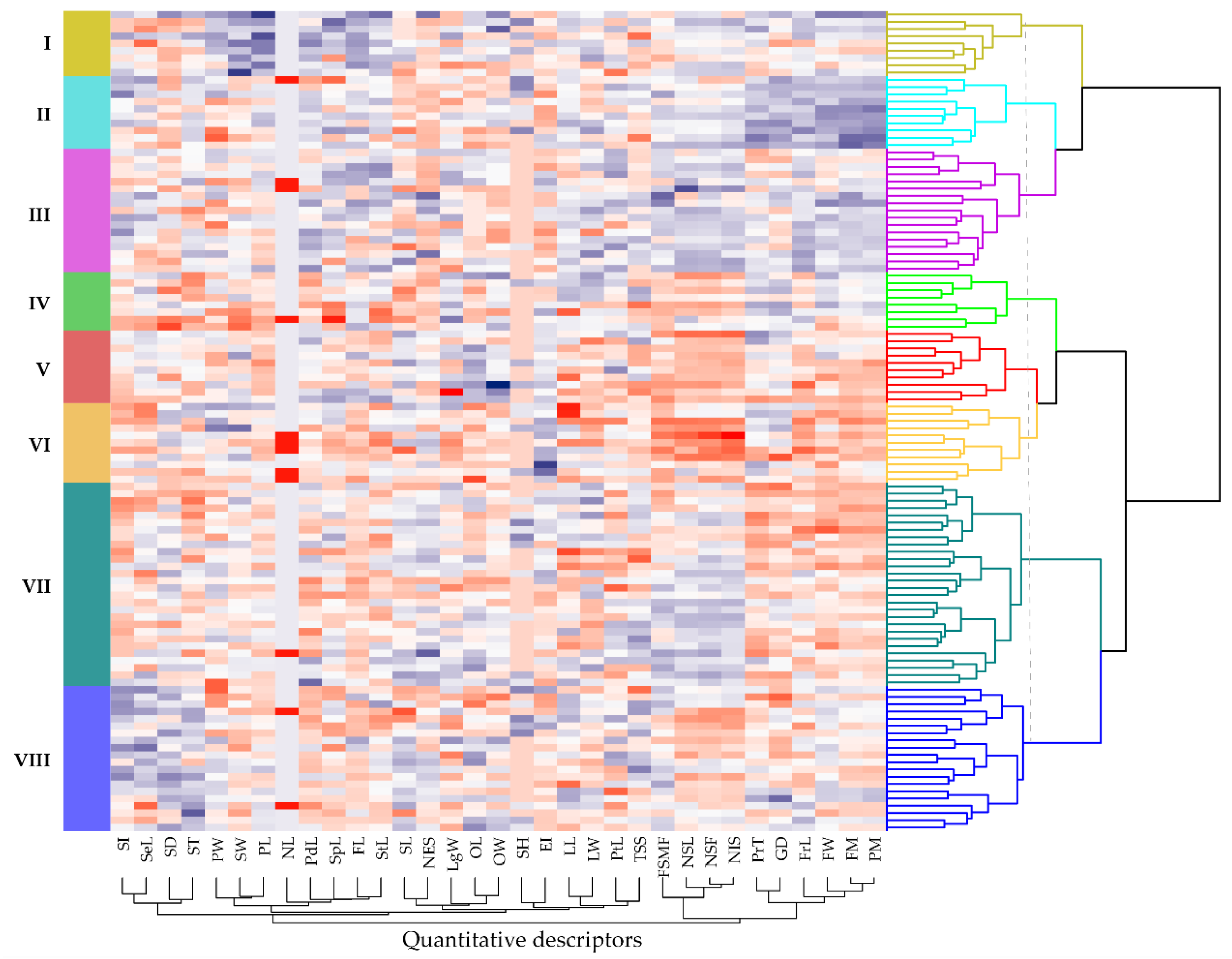

3.7. Structural Analysis for Quantitative Descriptors

3.8. Structural Analysis for Qualitative Descriptors

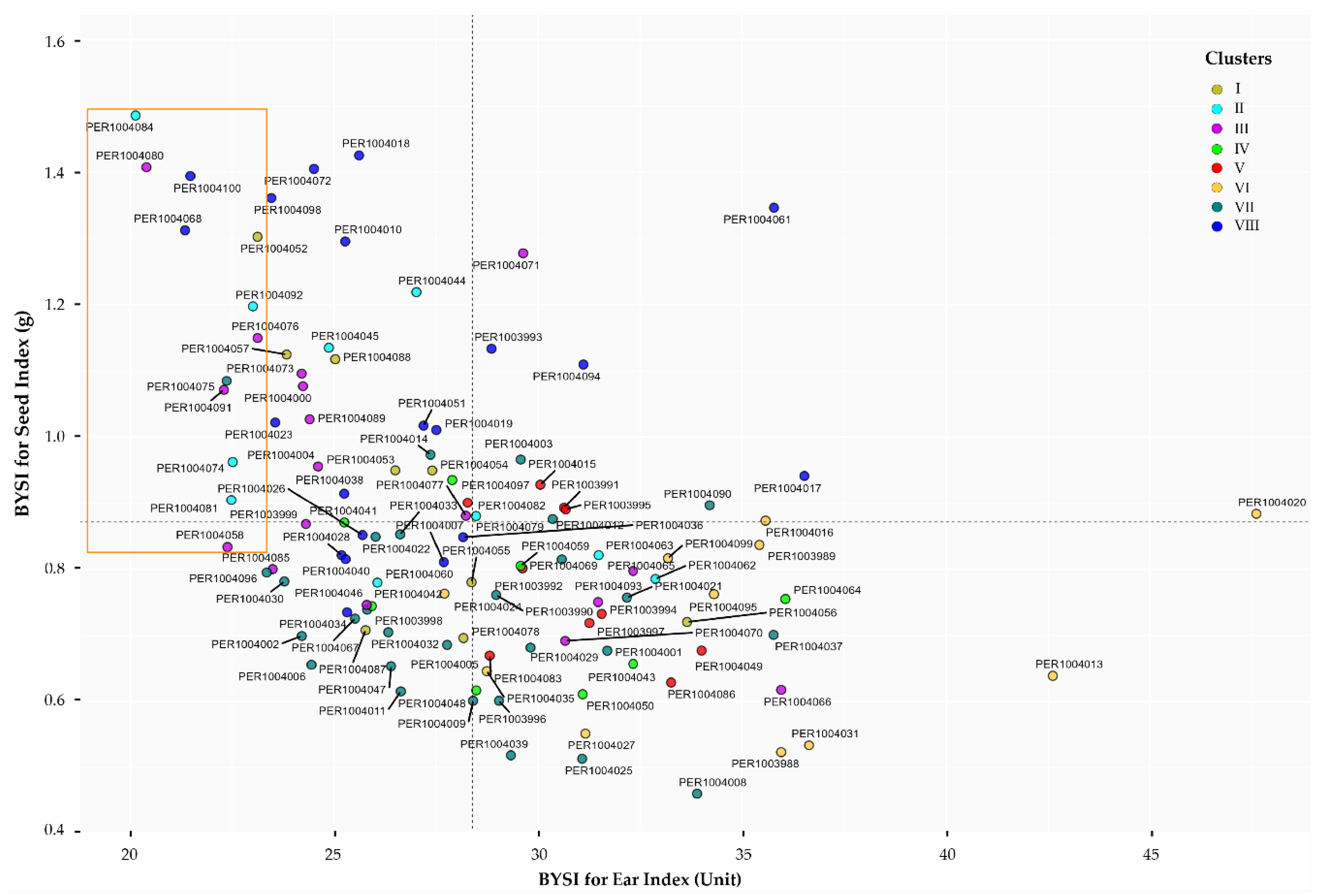

3.9. Selection of Promising Accessions

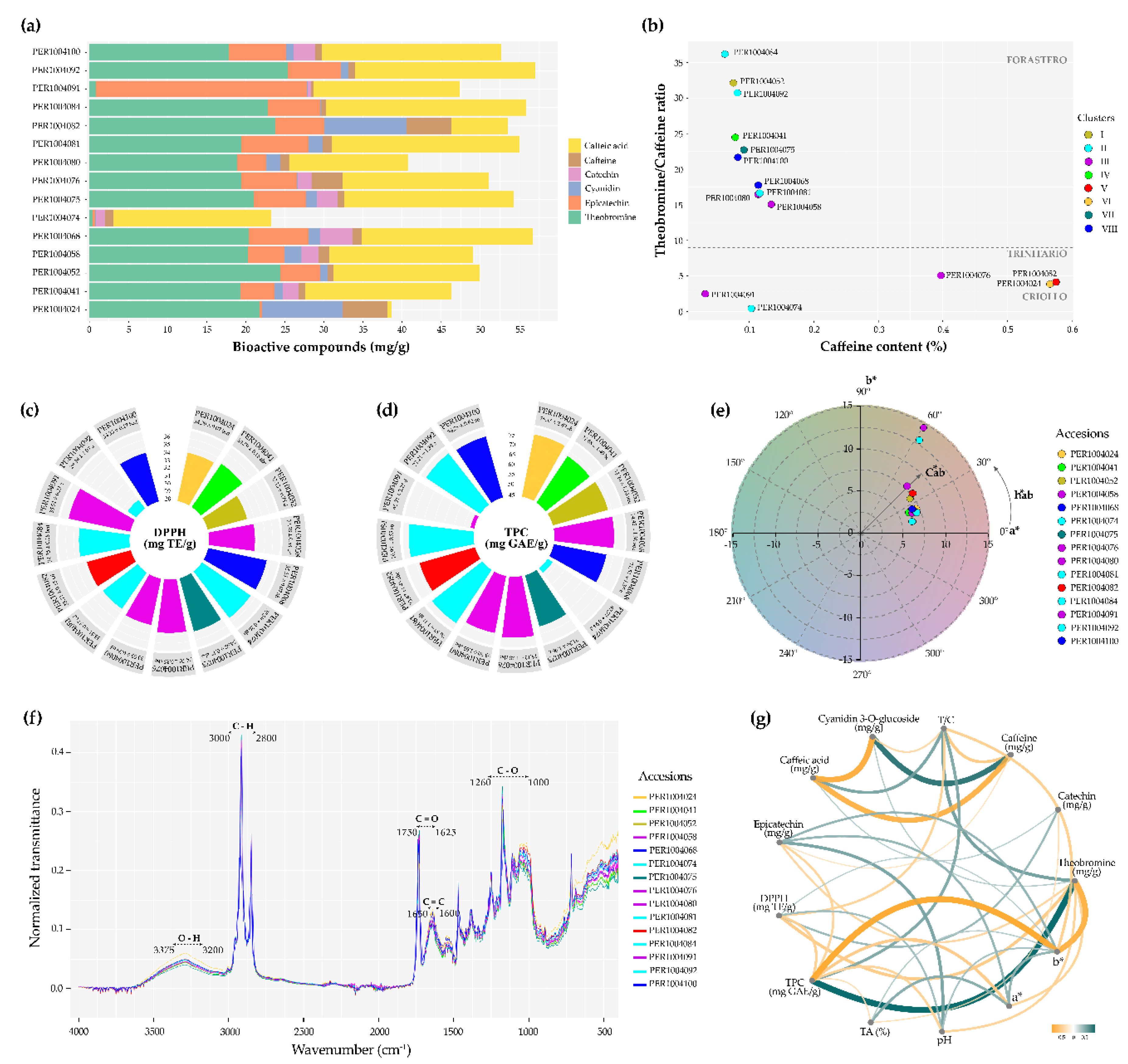

3.10. Phytochemical Profile of Selected Cacao Cotyledons

4. Discussion

4.1. Ex Situ Germplasm Collection Management

4.2. Phenotyping of Genetic Resources

4.3. Phytochemical Profile of Fine-Flavor Cacao

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boukrouh, S.; Noutfia, A.; Moula, N.; Avril, C.M.; Louvieaux, J.; Hornick, J.L.; et al. Ecological, morpho-agronomical, and bromatological assessment of sorghum ecotypes in Northern Morocco. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouam, E.B.; Kamga-Fotso, A.M.A.; Anoumaa, M. Exploring agro-morphological profiles of Phaseolus vulgaris germplasm shows manifest diversity and opportunities for genetic improvement. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alverson, W.S.; Whitlock, B.A.; Nyffeler, R.; Bayer, C.; Baum, D.A. Phylogeny of the core Malvales: evidence from ndhF sequence data. Am. J. Bot. 1999, 86, 1474–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamayor, J.C; Lanaud, C. Molecular analysis of the origin and domestication of Theobroma cacao L. In Managing plant genetic diversity, Proceedings of an international conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12-16 June 2000; Engels, J.M.M., Ed.; Engels, J.M.M.; Ramanatha Rao; Brown A.H.D.; Jackson M.T.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford UK, 2002; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrillo, S.; Gaikwad, N.; Lanaud, C.; Powis, T.; Viot, C.; Lesur, I. , et al. The use and domestication of Theobroma cacao during the mid-Holocene in the upper Amazon. Nat. Ecol. Evol. [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Cruz, M.; Goñas, M.; Bobadilla, L.G.; Rubio, K.B.; Escobedo-Ocampo, P.; García Rosero, L.M.; et al. Genetic Groups of Fine-Aroma Native Cacao Based on Morphological and Sensory Descriptors in Northeast Peru. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 896332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Cruz, M.; Mori-Culqui, P.L.; Caetano, A.C.; Goñas, M.; Vilca-Valqui, NC.; Chavez, S.G. Total Fat Content and Fatty Acid Profile of Fine-Aroma Cocoa From Northeastern Peru. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 677000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, A.M.; Dunwell, J.M. Cacao biotechnology: current status and future prospects. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Valderrama, J.R.; Leiva-Espinoza, S.T.; Aime, M.C. The History of Cacao and Its Diseases in the Americas. Phytopathology. 2020, 110, 1604–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Martínez, W.J.; Johnson, E.S.; Somarriba, E.; Phillips-Mora, W.; Astorga, C.; et al. Genetic diversity and spatial structure in a new distinct Theobroma cacao L. population in Bolivia. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Lachenaud, P.; Mota, J.W.S.; Loor, R.; Kuhn, D.N.; Brown, J.S.; et al. Geographic and Genetic Population Differentiation of the Amazonian Chocolate Tree (Theobroma cacao L). PLoS ONE. 2008, 3, e3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Zonneveld, M.V.; Loo, J.; Hodgkin, T.; Galluzzi, G.; Etten, J.V. Present Spatial Diversity Patterns of Theobroma cacao L. in the Neotropics Reflect Genetic Differentiation in Pleistocene Refugia Followed by Human-Influenced Dispersal. PLos ONE. 2012, 7, e47676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INDECOPI. Denominación de Origen Cacao Amazonas Perú. 2016. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/indecopi/informes-publicaciones/5227603-denominacion-de-origen-cacao-amazonas-peru-2016 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- ICCO. Panel recognizes 23 countries as fine and flavour cocoa exporters. 2016. Available online: https://www.icco.org/icco-panel-recognizes-23-countries-as-fine-and-flavour-cocoa-exporters/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Pridmore, R.D.; Crouzillat, D.; Walker, C.; Foley, S.; Zink, R.; Zwahlen, M.C.; et al. Genomics, molecular genetics and the food industry. J. Biotechnol. 2000, 78, 251–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Castro, J.B.; Torres Armas, E.A. Caracterización de productores en la cadena de valor del cacao fino de aroma de Amazonas. Universidad San Pedro. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Doaré, F.; Ribeyre, F.; Cilas, C. Genetic and environmental links between traits of cocoa beans and pods clarify the phenotyping processes to be implemented. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanatha Rao, V.; Hodgkin, T. Genetic diversity and conservation and utilization of plant genetic resources. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2002, 68, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, O.O.; Ariyo, O.J. Diversity Analysis of Cacao (Theobroma Cacao) Genotypes in Nigeria Based on Juvenile Phenotypic Plant Traits. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, S1348–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Cruz, M.; Goñas, M.; García, L.M.; Rabanal-Oyarse, R.; Alvarado-Chuqui, C.; Escobedo-Ocampo, P.; et al. Phenotypic Characterization of Fine-Aroma Cocoa from Northeastern Peru. Int. J. Agron. 2021, 2021, 2909909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Bio Yerima, A.R.; Achigan-Dako, E.G.; Aissata, M.; Sekloka, E.; Billot, C.; Adje, C.O.A.; et al. Agromorphological Characterization Revealed Three Phenotypic Groups in a Region-Wide Germplasm of Fonio (Digitaria exilis (Kippist) Stapf) from West Africa. Agronomy. 2020, 10, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Espinosa, R.; Gutiérrez-Reynoso, D.L.; Atoche-Garay, D.; Mansilla-Córdova, P.J.; Abad-Romaní, Y.; Girón-Aguilar, C.; et al. Agro-morphological characterization and diversity analysis of Coffea arabica germplasm collection from INIA, Peru. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 2877–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshitila, M.; Gedebo, A.; Tesfaye, B.; Degu, H.D. Agro-morphological genetic diversity assessment of Amaranthus genotypes from Ethiopia based on qualitative traits. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2024, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudoin Wouokoue, T.J.; Fouelefack, F.R.; Leticia Liejip, N.C.; Biakdjolbo, W.E.; Mafouo, T.E.; Morphoagronomic and Phenological Characteristics of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L. ) Grown in Sudano-Sahelian Zone of Cameroon. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 2025, 5568972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachef, A.; Bourguiba, H.; Cherif, E.; Ivorra, S.; Terral, J.F.; Zehdi-Azouzi, S. Agro-morphological traits assessment of Tunisian male date palms (Phœnix dactylifera L.) for preservation and sustainable utilization of local germplasm. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virga, G.; Licata, M.; Consentino, B.B.; Tuttolomondo, T.; Sabatino, L.; Leto, C.; et al. Agro-Morphological Characterization of Sicilian Chili Pepper Accessions for Ornamental Purposes. Plants. 2020, 9, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, F.; Butler, D.R. Proposed short list of cocoa descriptors for characterization. In Working Procedures for Cocoa Germplasm Evaluation and Selection, Proceedings of the CFC/ICCO/IPGRI Project Workshop, Montpellier, France, 1–6 February, 1998.

- MIDAGRI. Banco de Germoplasma del Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria. 2025. Available online: https://genebankperu.inia.gob.pe/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- MINAM. Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú - Datos hidrometeorológicos a nivel nacional. 2025. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?&p=estaciones (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Bekele, F.L.; Bidaisee, G.G.; Singh, H.; Saravanakumar, D.; Morphological characterisation and evaluation of cacao (Theobroma cacao L. ) in Trinidad to facilitate utilisation of Trinitario cacao globally. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 621–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imán Correa, S.A.; Samanamud Curto, A.F.; Paredes Meneses, C.; Chuquizuta Del Castillo, B.; Arévalo Pinedo, M.T. Descriptores para cacao, Lima, Perú. 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12955/2457 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Compañía Nacional de Chocolates, S.A.S.; Protocolo para la caracterización morfológica de árboles élite de cacao (Teobroma cacao L.), Medellín, Colombia. 2018. Available online: http://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://chocolates.com.co/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Cartilla_Protocolo_Cacao_dic20_VFF.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Cortez, D.; Flores, M.; Calampa, LL.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Goñas, M.; Meléndez-Mori, J.B.; et al. From the seed to the cocoa liquor: Traceability of bioactive compounds during the postharvest process of cocoa in Amazonas-Peru. Microchem. J. 2024, 201, 110607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, D.; Quispe-Sanchez, L.; Mestanza, M.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Yoplac, I.; Torres, C.; et al. Changes in bioactive compounds during fermentation of cocoa (Theobroma cacao) harvested in Amazonas-Peru. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Viena R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Komsta, L. Outliers: Tests for Outliers. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/outliers/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Comtois, D. summarytools: Tools to Quickly and Neatly Summarize Data. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/summarytools/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Popat, R.; Patel, R.; Parmar, D. variability: Genetic Variability Analysis for Plant Breeding Research. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/variability/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Harrell, F.E.Jr. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Hmisc/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J.; et al. corrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Hubert, M.; Hornik, K.; Schubert, E. cluster: ''Finding Groups in Data'': Cluster Analysis Extended Rousseeuw et al. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cluster/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Gu, Z.; Hübschmann, D. Make Interactive Complex Heatmaps in R. Bioinformatics. 2022, 38, 1460–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, T. dendextend: Extending 'dendrogram' Functionality in R. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dendextend/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Hadfield, J.D. MCMC Methods for Multi-Response Generalized Linear Mixed Models: The MCMCglmm R Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Negrete, L.; Orozco-Orozco, L.F.; Torres, J.M.C.; Medina-Cano, C.I.; Grisales-Vasquez, N.Y. Fiber production repeatability and selection of promising fique (Furcraea spp.) genotypes. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 2666–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/agricolae/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Wickham, H. tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the 'Tidyverse'. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyverse/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Pedersen, T.L. ggforce: Accelerating 'ggplot2'. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggforce/index.html (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Hanson, B.A. Exploratory Chemometrics for Spectroscopy. 2025. Available online: https://bryanhanson.github.io/ChemoSpec/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Meléndez-Mori, J.B.; Guerrero-Abad, J.C.; Tejada-Alvarado, J.J.; Ayala-Tocto, R.Y.; Oliva, M. Genotypic variation in cadmium uptake and accumulation among fine-aroma cacao genotypes from northern Peru: a model hydroponic culture study. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2023, 35, 2287710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tineo, D.; Bustamante, D.E.; Calderon, M.S.; Oliva, M. Comparative analyses of chloroplast genomes of Theobroma cacao from northern Peru. PLos ONE. 2025, 20, e0316148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, A.; Lang, C.; Fischer, M. Genetic authentication: Differentiation of fine and bulk cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) by a new CRISPR/Cas9-based in vitro method. Food Control. 2020, 114, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fister, A.S.; Landherr, L.; Maximova, S.N.; Guiltinan, M.J. Transient Expression of CRISPR/Cas9 Machinery Targeting TcNPR3 Enhances Defense Response in Theobroma cacao. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Pierides, I.; Zhang, S.; Schwarzerova, J.; Ghatak, A.; Weckwerth, W. Multiomics for Crop Improvement. In Sustainability Sciences in Asia and Africa; Pandey, M.K., Bentley, A., Desmae, H., Roorkiwal, M., Varshney, R.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imán, S.A.; Samanamud, A.F.; Ramirez, J.F.; Cobos, M.; Paredes, C.; Castro, J.C. Development and phenotypic characterization of a native Theobroma cacao L. germplasm bank from the Loreto region of the Peruvian Amazon: implications for Ex situ conservation and genetic improvement. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2025, 6, 1576239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.E.; DuVal, A.; Puig, A.; Tempeleu, A.; Crow, T. Interactive and Dynamic Effects of Rootstock and Rhizobiome on Scion Nutrition in Cacao Seedlings. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 754646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, D.E.; Motilal, L.A.; Calderon, M.S.; Mahabir, A.; Oliva, M. Genetic diversity and population structure of fine aroma cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) from north Peru revealed by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 895056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, F.; Phillips-Mora, W. Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Industrial and Food Crops; Al-Khayri, J., Jain, S., Johnson, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2019; pp. 409–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixão, V.; Nunez-Rodriguez, J.C.; del Olmo, V.; Ksiezopolska, E.; Saus, E; Boekhout, T. ; et al. Evolution of loss of heterozygosity patterns in hybrid genomes of Candida yeast pathogens. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombart, T.; Devillard, S.; Balloux, F. Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet. 2010, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, R.F.; Gustian; Efendi, S. Morphological Characterization of Cacao Plants (Theobroma cacao L.) from Dharmasraya Regency of West Sumatra. CELEBES Agric. 2023, 4, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamayor, J.C.; Risterucci, A.M.; Lopez, P.A.; Ortiz, C.F.; Moreno, A. , Lanaud, C. Cacao domestication I: the origin of the cacao cultivated by the Mayas. Heredity. 2002, 89, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlahig, S.; Mohamed, A.; Triki, T.; Yahia, Y.; Yehmed, J.; Yahia, H.; et al. Integrated agro-morphological and molecular characterization for progeny testing to enhance alfalfa breeding in arid regions of Tunisia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 20, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidot Martínez, I.; Valdés de la Cruz, M.; Riera Nelson, M.; Bertin, P. Morphological characterization of traditional cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) plants in Cuba. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, M.A.; Reyes-Palencia, J.; Jiménez, P. Floral biology and flower visitors of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) in the upper Magdalena Valley, Colombia. Flora. 2024, 313, 152480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Baek, I.; Hong, S.M.; Lee, Y.; Kirubakaran, S.; Kim, M.S.; et al. Cacao floral traits are shaped by the interaction of flower position with genotype. Heliyon. 2025, 11, e42407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Guarín, J.A.; Berdugo-Cely, J.; Coronado, R.A.; Zapata, Y.P.; Quintero, C.; Gallego-Sánchez, G.; et al. Colombia a Source of Cacao Genetic Diversity As Revealed by the Population Structure Analysis of Germplasm Bank of Theobroma cacao L. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-García, J.; Santos-Pelaez, J.C.; Malqui-Ramos, R.; Vigo, C.N.; C, W.A.; Bobadilla, L.G. Agromorphological characterization of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) accessions from the germplasm bank of the National Institute of Agrarian Innovation, Peru. Heliyon. 2022, 8, e10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trunschke, J.; Lunau, K.; Pyke, G.H.; Ren, Z.X.; Wang, H. Flower Color Evolution and the Evidence of Pollinator-Mediated Selection. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 617851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Medina, C.; Arana, A.C.; Sounigo, O.; Argout, X.; Alvarado, G.A.; Yockteng, R. Cacao breeding in Colombia, past, present and future. Breed. Sci. 2019, 69, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzuni; Ambardini, S. ; Widyaningsih, A.S.; Ismaun. Morphological and physiological characteristics of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L. var. criollo) infected by Phytophthora palmivora in cocoa plantations in Southeast Sulawesi Indonesia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2704, 020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daymond, A.j.; Hadley, P. Differential effects of temperature on fruit development and bean quality of contrasting genotypes of cacao (Theobroma cacao). Ann. Appl. Biol. 2008, 153, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoopen, G.M.; Deberdt, P.; Mbenoun, M.; Cilas, C. Modelling cacao pod growth: implications for disease control. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2012, 160, 260–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Orduña, H.E.; Müller, M.; Krutovsky, K.V.; Gailing, O. Genotyping of cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) germplasm resources with SNP markers linked to agronomic traits reveals signs of selection. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2024, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparno, A.; Arbianto, M.A.; Prabawardani, S.; Chadikun, P.; Tata, H.; Luhulima, F.D.N. The identification of yield components, genetic variability, and heritability to determine the superior cocoa trees in West Papua, Indonesia. Biodiversitas. 2024, 25, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, J.A.; Ortiz-Mejía, F.N.; Parada-Berríos, F.A.; Lara-Ascencio, F.; Vásquez-Osegueda, E.A. Caracterización morfoagronómica de cacao criollo (Theobroma cacao L.) y su incidencia en la selección de germoplasma promisorio en áreas de presencia natural en El Salvador. Rev. Minerva. 2019, 2, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenaud, P.; Motamayor, J.C. The Criollo cacao tree (Theobroma cacao L.): a review. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 1807–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifah, E.N.; Sari, I.A.; Susilo, A.W.; Malik, A.; Fukusaki, E.; Putri, S.P. Characterization of fine-flavor cocoa in parent-hybrid combinations using metabolomics approach. Food Chem: X. 2024, 24, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongor, J.E.; Hinneh, M.; de Walle, D.V.; Afoakwa, E.O.; Boeckx, P.; Dewettinck, K. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean flavour profile — A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Martínez-Bolaños, M.; Reyes-Reyes, A.L.; Aragón-Magadán, M.A.; Reyes-López, D.; López-Morales, F. Genotype-environment interaction of genotypes of cocoa in Mexico. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez-Vasconez, P.A.; Castro-Zambrano, M.I.; Rodríguez-Cabal, H.A.; Castro, D.; Arbelaez, L.; Zambrano, J.C. Exploring Theobroma grandiflorum diversity to improve sustainability in smallholdings across Caquetá, Colombia. Int. J. Agron. 2025, 20, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falque, M.; Vincent, A.; Vaissiere, B.E.; Eskes, A.B. Effect of pollination intensity on fruit and seed set in cacao (Theobroma cacao L.). Sex. Plant Reprod. 1995, 8, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, J.G.B.; Tellez, H.B.H.; Atuesta, G.C.P.; Aldana, A.P.S.; Arteaga, J.J.M. Antioxidant activity, total polyphenol content and methylxantine ratio in four materials of Theobroma cacao L. from Tolima, Colombia. Heliyon. 2022, 8, e09402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tušek, K.; Valinger, D.; Jurina, T.; Sokač Cvetnić, T.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Benković, M. Bioactives in Cocoa: Novel Findings, Health Benefits, and Extraction Techniques. Separations. 2024, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.M.; Santana, L.R.R.; Maciel, L.F.; Soares, S.E.; Ferreira, A.C.R.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; et al. Phenolic compounds, methylxanthines, and preference drivers of dark chocolate made with hybrid cocoa beans. Res. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, e22912440782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oracz, J.; Nebesny, E.; Zyzelewicz, D.; Budryn, G.; Luzak, B. Bioavailability and metabolism of selected cocoa bioactive compounds: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1947–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.V.S.; Moura, F.G.; Gofflot, S.; Pinto, A.S.O.; de Souza, J.N.S.; Baeten, V.; et al. Targeted metabolomics for quantitative assessment of polyphenols and methylxanthines in fermented and unfermented cocoa beans from 18 genotypes of the Brazilian Amazon. Food Res. Int. 2025, 211, 116394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Alvarez, A.; Bedoya-Vergara, C.; Porras-Barrientos, L.D.; Rojas-Mora, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cabal, H.A.; Gil-Garzon, M.A.; et al. Molecular, biochemical, and sensorial characterization of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) beans: A methodological pathway for the identification of new regional materials with outstanding profiles. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e24544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, S.; Fisette, T.; Pinto, A.; Souza, J.; Rogez, H. Discriminating Aroma Compounds in Five Cocoa Bean Genotypes from Two Brazilian States: White Kerosene-like Catongo, Red Whisky-like FL89 (Bahia), Forasteros IMC67, PA121 and P7 (Pará). Molecules. 2023, 28, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.A.; Mohd Daud, I.S.; Mohamad Rojie, M.H.; Hussain, N.; Rukayadi, Y. Effects of Candida sp. and Blastobotrys sp. Starter on Fermentation of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) Beans and its Antibacterial Activity. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 10, 2501–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, N.N.; de Andrade, D.P.; Ramos, C.L.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Antioxidant capacity of cocoa beans and chocolate assessed by FTIR. Food Res. Int. 2016, 90, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deus, V.L.; Resende, L.M.; Bispo, E.S.; Franca, A.S.; Gloria, M.B.A. FTIR and PLS-regression in the evaluation of bioactive amines, total phenolic compounds and antioxidant potential of dark chocolates. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, G.; Boffa, L.; Binello, A.; Mantegna, S.; Cravotto, G.; Chemat, F.; et al. Analytical dataset of Ecuadorian cocoa shells and beans. Data Br. 2019, 22, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Gómez, I.; Carrera-Lanestosa, A.; González-Alejo, F.A.; Guerra-Que, Z.; García-Alamilla, R.; Rivera-Armenta, J.L.; et al. Pectin Extraction Process from Cocoa Pod Husk (Theobroma cacao L.) and Characterization by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. ChemEngineering. 2025, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Sambony, F.; Barrios-Rodríguez, Y.F.; Medina-Orjuela, M.E.; Gutiérrez-Guzmán, N.; Amorocho-Cruz, C.M.; Carranza, C.; et al. Relationship between physicochemical properties of roasted cocoa beans and climate patterns: Quality and safety implications. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 216, 117320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Estructure | Descriptor | GV | PV | GCV (%) | PCV (%) | H2 (%) | GA | GAM (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | LL | 27.90 | 0.60 | 1.51 | 2.78 | 4.40 | 39.91 | 1.01 | 3.62 |

| LW | 9.72 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 4.22 | 6.52 | 41.83 | 0.55 | 5.62 | |

| PtL | 1.84 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 6.35 | 14.10 | 20.28 | 0.11 | 5.89 | |

| Flower | PdL | 1.63 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 14.26 | 17.95 | 63.11 | 0.38 | 23.34 |

| SpL | 7.92 | 0.96 | 1.27 | 12.36 | 14.21 | 75.59 | 1.75 | 22.13 | |

| SW | 2.63 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 17.71 | 20.27 | 76.30 | 0.84 | 31.86 | |

| PL | 3.90 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 10.40 | 12.36 | 70.82 | 0.70 | 18.03 | |

| PW | 2.11 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 9.08 | 13.21 | 47.26 | 0.27 | 12.86 | |

| LgW | 2.71 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 11.43 | 16.16 | 50.05 | 0.45 | 16.66 | |

| FL | 3.99 | 1.67 | 2.06 | 32.36 | 35.98 | 80.90 | 2.39 | 59.96 | |

| StL | 6.76 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 8.84 | 10.46 | 71.38 | 1.04 | 15.38 | |

| SL | 3.35 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 2.99 | 24.02 | 1.55 | 0.03 | 0.77 | |

| OL | 1.71 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 11.89 | 17.43 | 46.50 | 0.29 | 16.70 | |

| OW | 1.23 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 14.31 | 17.64 | 65.76 | 0.29 | 23.90 | |

| Fruit | SH | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 27.90 | 27.90 | 100.00 | 0.21 | 57.48 |

| FM | 767.30 | 53286.70 | 68984.54 | 30.08 | 34.23 | 77.24 | 417.94 | 54.47 | |

| FrL | 19.54 | 7.29 | 10.56 | 13.81 | 16.62 | 69.04 | 4.62 | 23.65 | |

| FD | 9.85 | 0.67 | 1.05 | 8.32 | 10.38 | 64.19 | 1.35 | 13.73 | |

| PrT | 2.06 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 17.58 | 20.97 | 70.27 | 0.63 | 30.36 | |

| GD | 1.34 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 21.17 | 23.31 | 82.47 | 0.53 | 39.61 | |

| PM | 545.16 | 34718.83 | 47675.19 | 34.18 | 40.05 | 72.82 | 327.56 | 60.08 | |

| NL | 4.89 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 2.57 | 2.57 | 100.00 | 0.26 | 5.30 | |

| TSS | 17.35 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 7.09 | 7.09 | 100.00 | 2.53 | 14.60 | |

| Seed | NSL | 7.86 | 0.67 | 2.60 | 10.43 | 20.52 | 25.81 | 0.86 | 10.91 |

| FSMF | 147.29 | 985.50 | 1809.02 | 21.31 | 28.88 | 54.48 | 47.73 | 32.41 | |

| NSF | 40.39 | 24.52 | 57.81 | 12.26 | 18.82 | 42.42 | 6.64 | 16.45 | |

| SI | 1.28 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 13.86 | 25.51 | 29.55 | 0.20 | 15.52 | |

| EI | 20.57 | 1.60 | 64.09 | 6.15 | 38.93 | 2.50 | 0.41 | 2.00 | |

| NIS | 36.36 | 18.69 | 61.61 | 11.89 | 21.59 | 30.33 | 4.90 | 13.49 | |

| NES | 4.03 | 1.32 | 8.40 | 28.48 | 71.86 | 15.71 | 0.94 | 23.26 | |

| SeL | 26.12 | 2.35 | 5.14 | 5.87 | 8.68 | 45.78 | 2.14 | 8.18 | |

| SD | 13.88 | 0.86 | 2.16 | 6.67 | 10.59 | 39.74 | 1.20 | 8.67 | |

| ST | 9.09 | 0.28 | 1.82 | 5.79 | 14.83 | 15.25 | 0.42 | 4.66 |

| Descriptors | Cluster I Mean ± S.D | Cluster II Mean ± S.D | Cluster III Mean ± S.D | Cluster IV Mean ± S.D | Cluster V Mean ± S.D | Cluster VI Mean ± S.D | Cluster VII Mean ± S.D | Cluster VIII Mean ± S.D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | 28.28 ± 0.68 ab | 28.46 ± 0.60 a | 28.13 ± 0.71 ab | 28.34 ± 1.45 ab | 27.17 ± 1.05 ab | 26.87 ± 1.71 b | 27.78 ± 1.26 ab | 28.19 ± 1.28 ab |

| LW | 9.93 ± 0.58 ab | 9.76 ± 0.65 ab | 10.02 ± 0.63 ab | 10.14 ± 0.60 a | 9.29 ± 0.35 b | 9.31 ± 0.55 b | 9.75 ± 0.75 ab | 9.60 ± 0.40 ab |

| PtL | 1.83 ± 0.23 a | 1.88 ± 0.16 a | 2.00 ± 0.22 a | 1.85 ± 0.11 a | 1.82 ± 0.25 a | 1.78 ± 0.14 a | 1.77 ± 0.21 a | 1.83 ± 0.24 a |

| PdL | 1.91 ± 0.23 a | 1.71 ± 0.21 abc | 1.79 ± 0.27 ab | 1.45 ± 0.19 c | 1.73 ± 0.19 abc | 1.55 ± 0.11 bc | 1.59 ± 0.31 bc | 1.45 ± 0.16 c |

| SpL | 8.88 ± 1.39 a | 7.98 ± 1.29 abc | 8.50 ± 0.89 ab | 6.99 ± 0.37 c | 8.01 ± 1.04 abc | 7.69 ± 0.84 abc | 7.92 ± 0.78 abc | 7.40 ± 0.82 bc |

| SW | 3.69 ± 0.64 a | 2.43 ± 0.26 bc | 2.59 ± 0.28 bc | 2.18 ± 0.52 c | 2.73 ± 0.45 b | 2.79 ± 0.66 b | 2.60 ± 0.28 bc | 2.38 ± 0.32 bc |

| PL | 5.00 ± 0.57 a | 3.98 ± 0.33 b | 3.91 ± 0.33 bc | 3.56 ± 0.20 cd | 3.52 ± 0.19 d | 3.83 ± 0.32 bcd | 3.78 ± 0.26 bcd | 3.86 ± 0.27 bcd |

| PW | 2.40 ± 0.23 a | 1.98 ± 0.33 b | 2.09 ± 0.29 ab | 1.98 ± 0.22 b | 2.05 ± 0.19 b | 2.26 ± 0.31 ab | 2.08 ± 0.23 ab | 2.10 ± 0.27 ab |

| LgW | 2.63 ± 0.44 ab | 2.66 ± 0.25 ab | 2.79 ± 0.40 ab | 3.08 ± 0.35 a | 2.73 ± 0.57 ab | 2.50 ± 0.37 b | 2.76 ± 0.28 ab | 2.57 ± 0.41 b |

| FL | 6.21 ± 1.03 a | 4.75 ± 1.02 b | 4.65 ± 1.52 b | 4.39 ± 0.97 bc | 4.16 ± 1.35 bc | 2.82 ± 0.53 d | 3.22 ± 0.67 cd | 3.53 ± 1.13 bcd |

| StL | 7.58 ± 0.62 a | 6.93 ± 0.47 abc | 7.27 ± 0.69 ab | 6.47 ± 0.86 c | 6.61 ± 0.73 bc | 6.42 ± 0.66 c | 6.53 ± 0.53 bc | 6.57 ± 0.56 bc |

| SL | 3.25 ± 0.44 ab | 3.00 ± 0.34 b | 3.32 ± 0.61 ab | 2.83 ± 0.32 b | 3.71 ± 0.44 a | 3.33 ± 0.54 ab | 3.46 ± 0.40 ab | 3.45 ± 0.67 ab |

| OL | 1.72 ± 0.20 b | 1.56 ± 0.16 b | 1.70 ± 0.16 b | 1.62 ± 0.28 b | 2.03 ± 0.21 a | 1.47 ± 0.20 b | 1.73 ± 0.25 ab | 1.76 ± 0.31 ab |

| OW | 1.35 ± 0.31 ab | 1.20 ± 0.15 ab | 1.15 ± 0.13 b | 1.32 ± 0.23 ab | 1.42 ± 0.34 a | 1.14 ± 0.09 b | 1.19 ± 0.12 ab | 1.22 ± 0.19 ab |

| SH | 0.39 ± 0.12 ab | 0.43 ± 0.13 a | 0.31 ± 0.02 b | 0.33 ± 0.07 ab | 0.34 ± 0.08 ab | 0.35 ± 0.08 ab | 0.36 ± 0.09 ab | 0.38 ± 0.12 ab |

| FM | 852.33 ± 148.86 bc | 1267.08 ± 195.55 a | 958.86 ± 162.81 b | 769.7 ± 73.47 cd | 606.5 ± 116.97 de | 543.5 ± 125.93 e | 618.6 ± 123.27 de | 726.9 ± 132.81 cde |

| FrL | 21.00 ± 2.26 ab | 23.52 ± 1.71 a | 22.40 ± 2.18 a | 19.05 ± 2.25 bc | 17.01 ± 1.90 c | 16.77 ± 2.65 c | 18.34 ± 2.12 bc | 19.15 ± 2.43 bc |

| FW | 10.32 ± 1.00 b | 11.28 ± 0.56 a | 10.30 ± 0.76 b | 10.22 ± 0.98 b | 9.50 ± 0.73 bc | 9.06 ± 0.55 c | 9.11 ± 0.56 c | 10.07 ± 0.55 b |

| PrT | 2.15 ± 0.37 b | 2.67 ± 0.30 a | 2.05 ± 0.26 bc | 2.31 ± 0.28 ab | 2.13 ± 0.47 b | 2.18 ± 0.39 b | 1.71 ± 0.29 c | 2.01 ± 0.29 bc |

| GD | 1.30 ± 0.24 bc | 1.81 ± 0.15 a | 1.32 ± 0.22 bc | 1.56 ± 0.27 ab | 1.37 ± 0.21 bc | 1.36 ± 0.32 bc | 1.16 ± 0.19 c | 1.27 ± 0.35 bc |

| PM | 642.40 ± 139.25 b | 972.28 ± 137.75 a | 663.81 ± 125.82 b | 600.78 ± 86.20 b | 398.56 ± 96.74 c | 407.16 ± 110.11 c | 401.39 ± 85.58 c | 515.21 ± 127.65 bc |

| NL | 5.00 ± 0.01 a | 4.90 ± 0.32 ab | 4.88 ± 0.33 ab | 4.88 ± 0.35 ab | 5.00 ± 0.01 a | 4.55 ± 0.52 b | 4.96 ± 0.19 a | 4.90 ± 0.31 ab |

| TSS | 16.05 ± 2.95 a | 16.81 ± 0.45 a | 17.85 ± 2.13 a | 16.81 ± 3.95 a | 16.10 ± 3.60 a | 16.18 ± 1.13 a | 17.94 ± 3.07 a | 18.45 ± 3.48 a |

| NSL | 8.50 ± 0.73 a | 8.43 ± 0.64 ab | 9.09 ± 1.42 a | 7.15 ± 1.21 c | 6.42 ± 0.58 c | 6.52 ± 1.37 c | 8.43 ± 0.84 ab | 7.19 ± 0.83 bc |

| FSMF | 136.3 ± 18.68 bc | 166.9 ± 28.72 ab | 180.4 ± 35.64 a | 117.3 ± 11.39 cd | 111.8 ± 23.35 cd | 97.4 ± 21.99 d | 155.1 ± 33.74 ab | 160.4 ± 28.27 ab |

| NSF | 43.48 ± 3.42 a | 41.92 ± 4.40 ab | 46.02 ± 3.58 a | 35.15 ± 3.97 cd | 32.83 ± 2.76 cd | 31.88 ± 6.35 d | 45.18 ± 4.16 a | 37.31 ± 4.21 bc |

| SI | 1.34 ± 0.26 abc | 1.44 ± 0.28 ab | 1.36 ± 0.25 abc | 1.14 ± 0.14 c | 1.18 ± 0.14 bc | 1.11 ± 0.17 c | 1.11 ± 0.18 c | 1.53 ± 0.29 a |

| EI | 18.68 ± 3.71 b | 17.63 ± 5.05 b | 18.06 ± 5.27 b | 21.87 ± 4.45 b | 23.49 ± 2.18 ab | 29.18 ± 7.32 a | 20.19 ± 4.30 b | 18.82 ± 5.00 b |

| NIS | 39.72 ± 4.73 a | 39.78 ± 4.66 a | 41.95 ± 4.61 a | 33.04 ± 3.64 bc | 29.15 ± 3.23 bc | 27.44 ± 6.35 c | 39.89 ± 3.73 a | 33.27 ± 4.55 b |

| NES | 3.76 ± 2.93 ab | 2.14 ± 0.80 b | 4.07 ± 1.62 ab | 2.11 ± 0.85 b | 3.68 ± 1.33 ab | 4.44 ± 1.85 ab | 5.29 ± 2.29 a | 4.04 ± 1.70 ab |

| SeL | 25.19 ± 2.12 ab | 26.68 ± 2.11 ab | 26.37 ± 1.75 ab | 26.00 ± 1.91 ab | 26.57 ± 1.11 ab | 24.66 ± 1.93 b | 25.64 ± 1.66 ab | 27.37 ± 2.61 a |

| SD | 13.37 ± 1.56 b | 12.96 ± 0.74 b | 13.32 ± 0.82 b | 12.95 ± 1.81 b | 13.59 ± 0.83 b | 14.19 ± 1.15 ab | 14.04 ± 1.05 ab | 15.16 ± 1.16 a |

| ST | 9.22 ± 1.03 abc | 9.60 ± 0.55 ab | 9.21 ± 0.90 abc | 7.98 ± 0.92 d | 8.82 ± 0.57 bcd | 8.88 ± 1.01 bcd | 8.49 ± 0.83 cd | 10.20 ± 1.01 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).