Our system contains

N coupled Luttinger liquid wires that are adiabatically connected to two non-interacting leads. Both forward scattering and multi-particle backscattering processes occur inside the interacting region

. Bosonised description of this setup starts from assigning two chiral fields,

and

to each channel,

. In terms of

-dimensional vector

where the

N-dimensional vectors are

, the Lagrangian density can be written as,

where the canonical term defines the commutation relations in the operator formulation, and the Hamiltonian,

, contains forward scattering and backscattering terms,

Outside the wire (interacting section of length

L) matrix

tends to the diagonal matrix

, where

is the velocity of the

i-th channel in electrodes. The contacts are assumed to be adiabatic, with the confining potential varying slowly along the wire on the scale of the Fermi wavelength for the electrons originating from the leads. This requirement results in reflectionless contacts so that any particle in the wire will transmit into the leads. The bosonic collective excitations described by a Luttinger liquid represent long-wavelength oscillations and, therefore, spatial dependences of the forward-scattering matrices inside and outside the system do not affect adiabaticity.

This bilinear form defines an

n-dimensional vector space of backscattering vectors

that satisfy this condition. In the limit of strong backscattering, which will be considered for the rest of the paper, backscattering Hamiltonian pins all

sectors of the field to zero modulo

. Exciting oscillations around this minimum configuration costs energy, resulting in a gap in the spectrum. Therefore it is natural to rotate the problem into a basis that distinguishes between these sectors of the field. We transform the fields via the

matrix

M

such that the commutation relations are unchanged. This enforces that

with the group of possible transformations being the split orthogonal group

. The transformation to the gapped and gapless sectors of the field can be described by the column vectors

of matrix

M, with the requirement that

. For later calculations, it is useful to define these column vectors as,

2.1. Scattering And Transfer Matrices

Calculating the conductance through 1D systems requires a description of the contacts and external leads. In both the original quantisation of conductance for a non-interacting system [

18] and when there is a region of forward scattering [

19,

20,

21,

22], the leads solely determine the d.c. conductance. The dominance of the leads suggests that we can consider the transport problem with a scattering matrix that connects the incoming and outgoing original chiral fields,

and

. These fields propagate freely outside the interacting section of the wire but are mixed up inside the wire. However, when incoming excitations are in the energy gap, all the gapped sectors of the field will not be supported inside the wire and must be reflected in the low temperature limit. Therefore, there will be a simple description of the `scattering’ matrix in terms of the gapped and gapless modes. The gapped and gapless modes are not guaranteed to be chiral, so they are not related simply to incoming and outgoing modes, but the equivalent ’scattering’ matrix still relates the values of the fields on either side of the interacting region.

The crux of the problem is that our knowledge of the sectors of fields is for local linear combinations of the original chiral fields, but the S-matrix is a non-local object. In order to change the local basis of the S-matrix we first must create the appropriate transfer matrix. Then the local transformation of fields can be applied, and the corresponding scattering matrix in terms of the original chiral fields can be found. An important point to note is that transfer matrices cannot be meaningfully defined when there is perfect reflection, so the limit of perfect reflection can only be taken for the S-matrix.

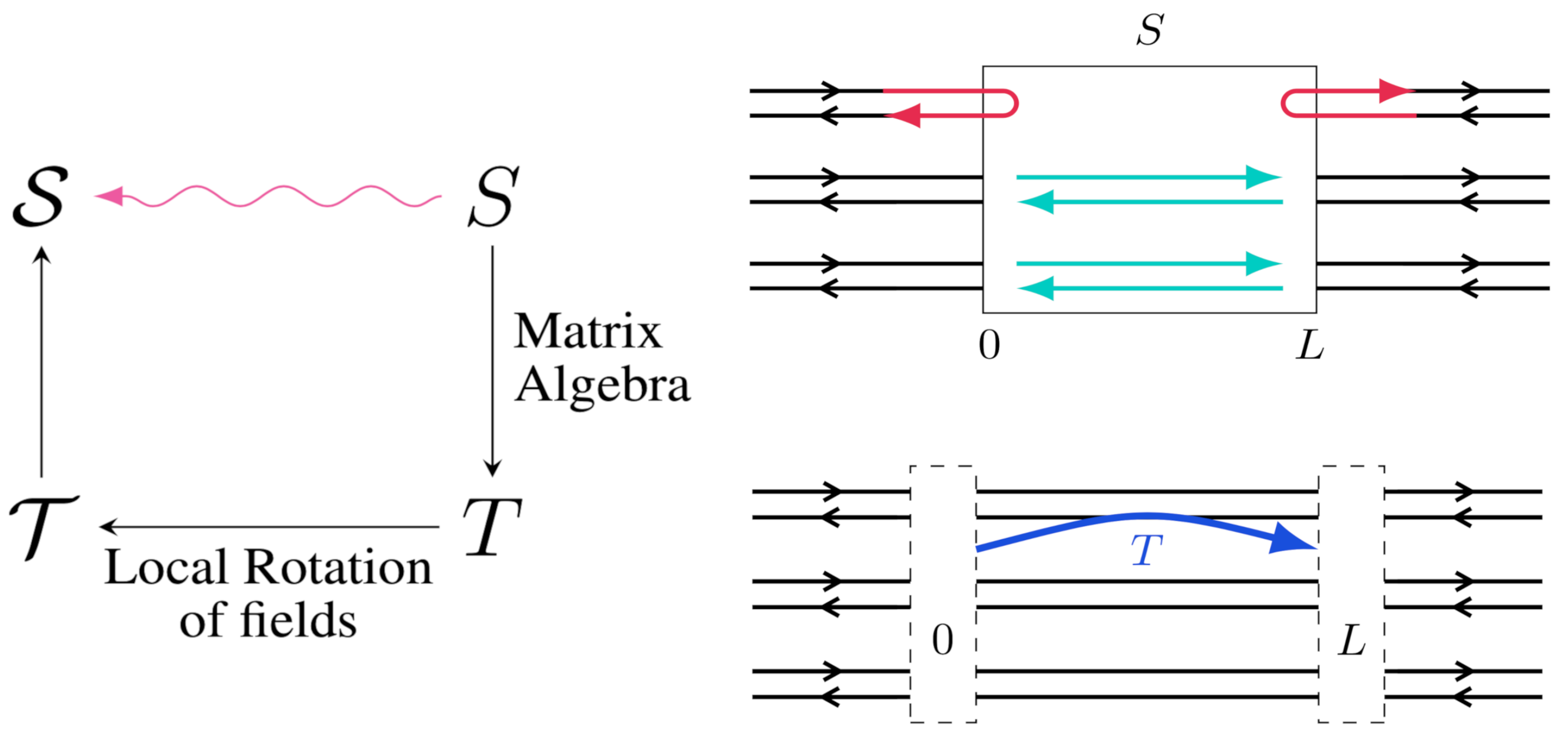

Figure 1.

Demonstrating how to relate scattering matrices in different bases through implementing the local rotation of fields on the transfer matrices, which are local objects. The S matrix relating combinations of fields at can be determined easily in the gapped and gapless basis but this is a non local object, while the transfer matrix acts on local combinations of fields.

Figure 1.

Demonstrating how to relate scattering matrices in different bases through implementing the local rotation of fields on the transfer matrices, which are local objects. The S matrix relating combinations of fields at can be determined easily in the gapped and gapless basis but this is a non local object, while the transfer matrix acts on local combinations of fields.

The scattering matrix

and the transfer matrix

are defined by a combination of the original chiral fields at two points

,

The two matrices can be related to each other through matrix algebra,

where

are

matrices that connect the right and left movers at different positions

. The transfer matrix for the rotated fields

T can be found by applying the transformation

M

which defines the relation between the transfer matrices

. Finally we can get the

S-matrix in the rotated basis through inverting Equation (

8). In this basis, for energies below the size of the gap at low temperatures and small voltages, the gapped sectors will fully reflect, and the gapless sectors will perfectly transmit. However, as mentioned earlier, due to the divergence of the transfer matrices, we cannot assume that the

S-matrix perfectly reflects, and therefore we must consider the more general case and take the perfect reflection limit at the end.

To illustrate the process, we start with the one-channel case. In the rotated fields, we can write the scattering matrix as

with current conservation, giving the conditions

. We only consider the situation of complete reflection

and perfect transmission

, which means that we can consider

and

. The corresponding transfer matrix in this basis can be expressed using

Although the perfect transmission limit is well defined as , the limit diverges. This can be understood as a transfer matrix that gets reflected, will not relate the fields on either side of the wire, resulting in a singular matrix.

Performing any local rotation of chiral fields on the transfer matrix and then finding the equivalent scattering matrix

for the rotated fields will result in the

limit producing a finite

matrix with only non-zero off-diagonal elements. Upon implementing current conservation, the off-diagonal elements will be equal to one and match Equation (

10). In the one-channel case, this states something obvious, that any linear combinations of chiral fields on either side of the interacting section are completely unrelated to each other in the case of perfect reflection. This freedom of choice in rotation of the chiral fields is a product of the

limit and will manifest again when we include more channels into the description.

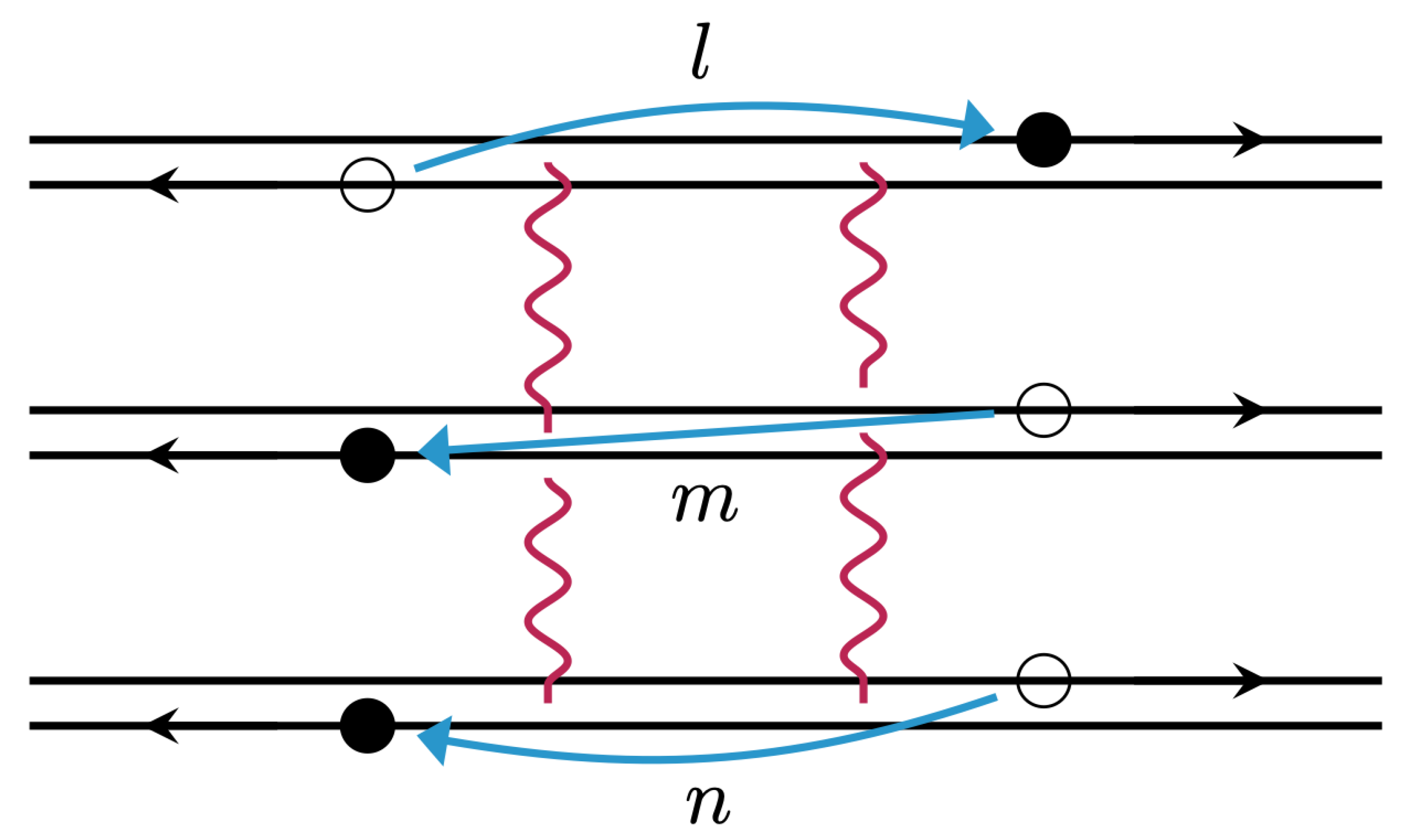

For multiple channels, the scattering matrix will be given by

where

are all

matrices with entries

and these describe the reflection and transmission of each channel. Current conservation now becomes the expression

, but if we assume that there is no scattering between channels, then we will have current conservation in each channel so that

. Then the total transfer matrix can be written as

where

is the reflection ratio for each channel. For any of the

that correspond to gapless modes, these can be safely taken to be 0 as the transfer matrices are well defined. The remaining

, where

a now only indexes the gapped sectors, can be set to the same value

as they will all be taken to be infinite. This allows us to simplify the transfer matrix to be

where repeated indices now imply summation. Using the transformation in Equation (

9) we can find the transfer matrix in the original fields, for

where

are

N-dimensional vectors,

The

matrix can be explicitly inverted to give

where

with the equality guaranteed from the Haldane criterion in Equation (

4). The matrix

refers to the

-th element of the inverse of matrix

. Therefore, the scattering matrix in the new basis will be

which defines the transmission and reflection elements in the original basis. In the total reflection limit, we can see that

, which then means that the operators become projectors.

= 1mathvariantdouble-struck2N - 2ΠG for being the projector onto the space G.

The d.c. current through the system can be written in terms of the scattering matrix by symmetrising the current on either side of the scattering region. Using the ’parity’ vector

of Equation (

3), the total d.c. current is defined as,

To show that these two expressions are equivalent, subtract the two vectors and use the particle conservation requirement. This equality implies that the total current is constant across the system. This then allows the total current to be written as a symmetrisation of the previous equation

where

. The incoming currents are emitted from the reservoirs at chemical potentials

for the left and right reservoirs, respectively. The voltage drop across the system will be the difference between the chemical potentials and therefore the conductance is given by

All of the details of the forward scattering interactions drop out in the d.c. limit and the conductance is entirely determined by the space created by the backscattering vectors. Note that this can be represented as projecting to the orthogonal complement space to

G. This space

can be decomposed into two orthogonal spaces

and

F, where

and the free space is what remains,

. From Equation (

4), we can see that the spaces

G and

are orthogonal. Therefore the projector can be written as

. However, due to the structure of vectors

, as they must satisfy

due to current conservation, the projector

does not contribute to the conductance in Equation (

21). The conductance can then be written as

, the overlap of the parity vector with the projection of the parity vector on the free space.