1. Introduction

The Landauer-Büttiker [

1,

2] has served as a cornerstone of mesoscopic physics for decades, providing an elegant and powerful framework for describing electrical conduction in quantum systems. A central tenet of this approach is the quantization of conductance, universally expressed as an integer or fractional multiple of the quantum of conductance,

e2/

h. Hence, in the case of an orifice with

N transverse mode the conductance and resistance are respectively. This fundamental constant, derived from the core principles of quantum mechanics, unequivocally establishes Planck's constant (h) as an indispensable parameter in characterizing quantum transport phenomena [

3,

4]. Its explicit appearance reflects the wave-particle duality and the inherent quantization of energy and momentum, underpinning phenomena ranging from ballistic transport in semiconductor nanowires [

5,

6] to the precise plateaus observed in the integer and fractional quantum Hall effects [

7,

8].

Here, we investigate the longitudinal conductance of a two-dimensional (2D) quantum wire subjected to a highly localized potential barrier. Such systems are central to modern quantum electronic devices, forming the basis for quantum point contacts, tunable field-effect transistors, and components in quantum computing architectures [

3,

9]. Our theoretical model considers a wide 2D wire (width W) where

, allowing for a multitude of propagating transverse modes. Crucially, the wire incorporates a strong and narrow potential barrier characterized by height

and width

, satisfying

and

. These conditions place the system squarely in a tunneling regime, where electrons interact strongly with the barrier, yet its narrowness permits an accurate approximation as a short-range scatterer, a limit widely explored in quantum scattering theory [

10].

Contrary to the ubiquitous presence of Planck's constant in quantum transport laws, the derivation of the conductance for this specific system yields an analytical expression that is explicitly

independent of Planck's constant (h) and the

electron density, depending solely on the Fermi energy (

), the electron effective mass (

), the wire's width (

w), and the barrier's integrated strength (

). This finding is particularly striking because the system operates in a 'heavy quantum regime' where tunneling through a classically impenetrable barrier is the dominant transport mechanism. While the Fermi energy itself is unequivocally a quantum mechanical concept, originating from the Pauli exclusion principle and the filling of discrete quantum states [

11], its definition does not, in itself, necessitate an explicit reliance on the electron's wave-like properties in the same manner as interference or typical tunneling probabilities do. The quantum of conductance,

e2/

h, on the other hand, is a direct consequence of the wave nature of charge carriers propagating through quantum channels [

3].

The explicit cancellation of h and n in our final conductance formula therefore points to a profound emergent behavior. It suggests that in this specific parameter regime—a wide wire with a high, narrow barrier—the 'wave-like' quantum characteristics, normally encoded in the explicit appearance of h, are effectively suppressed or averaged out in the global transport observable. This leaves a conductance value primarily dictated by the Fermi energy, which appears to function as a more fundamental 'state-counting' quantum parameter. This unique manifestation of quantum transport, where the 'residual' signature of the wave nature of the electron seemingly vanishes from the conductance, is puzzling and invites a re-examination of how and when different facets of quantum mechanics (state quantization vs. wave phenomena) explicitly shape macroscopic observables. Our work highlights a subtle yet significant departure from typical quantum conductance scaling, potentially offering new insights into the interplay of fundamental constants in mesoscopic systems and hinting at novel regimes for electronic device design.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II details the theoretical framework for a generic analytical approximate expression for the resistance of a 2D quantum wire. Section III provides an exact numerical derivation for a rectangular barrier case, and illustrate the validity of the generic expression. Section IV presents a possible experimental realization. Finally Section V concludes with a summary of our findings and outlines potential avenues for future theoretical and experimental investigations.

2. Generic Approximate Solution

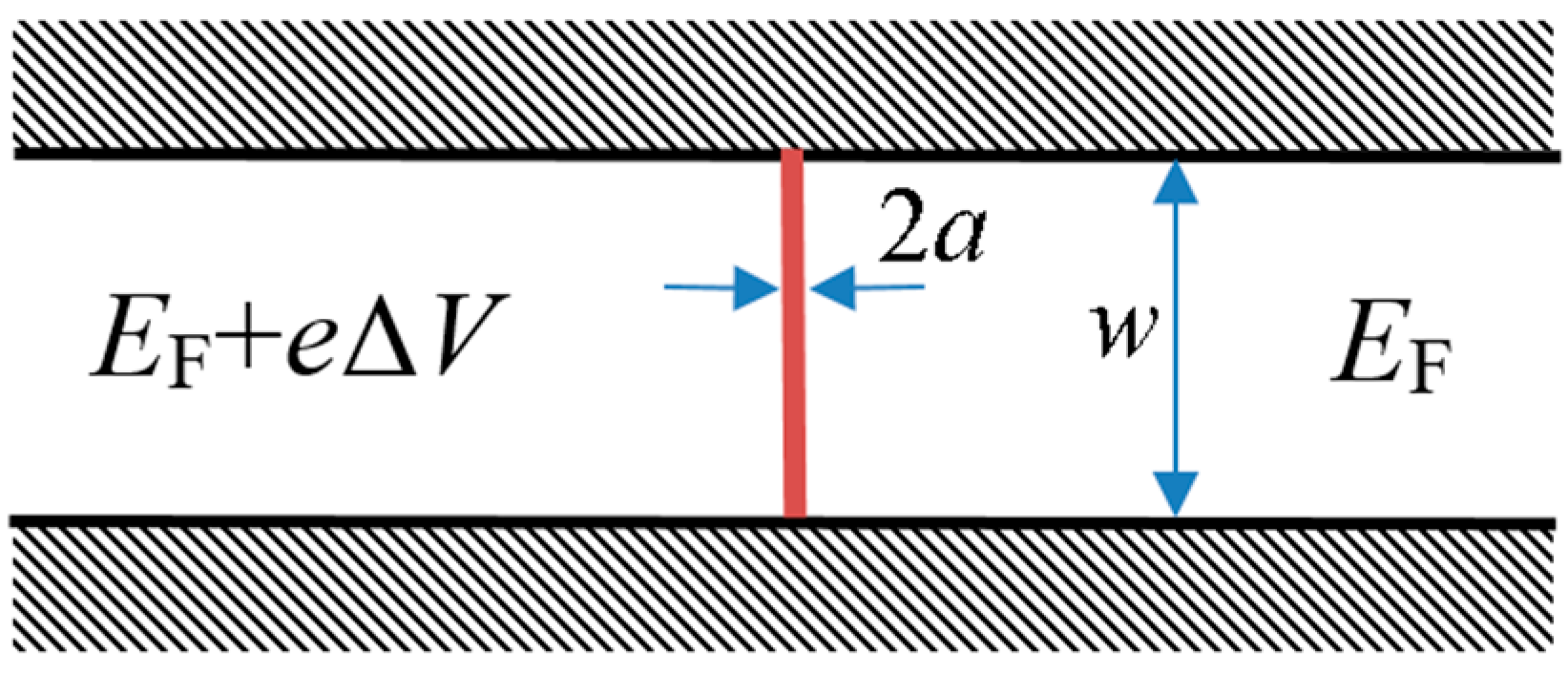

The system, illustrated in

Figure 1, comprises a wide, planar quantum wire (extending in the y-direction) featuring a narrow, high barrier of width 2a placed along the electron transport direction (

x-axis). This system is governed by the stationary Schrödinger equation:

where the potential consists of two parts:

The wire’s boundaries and the narrow membrane (barrier)

It should be emphasized that these two requirements can be less restrictive, i.e., the wire’s boundaries potential do not have to be infinite, and the barrier does not have to vanish beyond the [-a,a] domain. It just needs to be localized there.

Due to the Cartesian symmetry of the system, the propagating eigenstates can be written simply as

In case where the barrier width is considerably narrower than the electron’s de-Broglie wavelength, i.e.,

, or

, where the subscript “F” represents the Fermi wavenumber and Fermi-energy respectively, the solution for the longitudinal component can be written using the one-dimensional (1D) Green function

where

. The Green function (7) solves the differential equation

Therefore, in the narrow barrier regime, the solution reads

After substituting the Green function

in (9), the stationary solution reads

where

Therefore, beyond the barrier,

and the transmission coefficient of the

nth transverse propagating mode is

When the barrier has a rectangular profile, i.e.,

then

Eqs. (13) and (14) are consistent with the transmission of a delta function potential barrier, i.e.,

. The conductance is reached by substituting (13) in [

3]

where

is the number of propagating modes.

In the regime, where the wire’s width is much wider than the electron’s Fermi wavelength, i.e.

, and therefore the number of modes is very large

the summation in the conductance formula can be replaces with a corresponding integral

where

This integral has an exact analytical solution

This generic solution depends on the Planck constant both in the universal conductance

and in

D , however, in case

Therefore, the resistance can be written

The first term in (20) correspond to the resistance of a free wire

. However, the second term in (20), which represents the resistance of the barrier, is independent of the Planck constant:

In case the barrier has rectangular profile

While Eqs. (21) and (22) show a dependence on the Fermi energy, a quantum mechanical property, no residue of its wave-like nature is evident.

3. Exact Numerical Solution

Even when the number of modes is finite and the barrier has a finite width (unlike a delta function potential), Eqs.(20-22) remain valid. To show this, we numerically solve for the conductance of a finite-width wire with a finite-width barrier. The rectangular barrier case, i.e.,

, can be solved analytically (see, for example, Ref. [

12]). In this case the longitudinal wavefunction obeys

where

. The coefficients

and

can be derived from the boundary conditions on the wavefunction and its derivative (for details, see [

12]). The final transmission coefficients

can be substituted in (15) to obtain

From (24), the exact barrier resistance can be derived

.

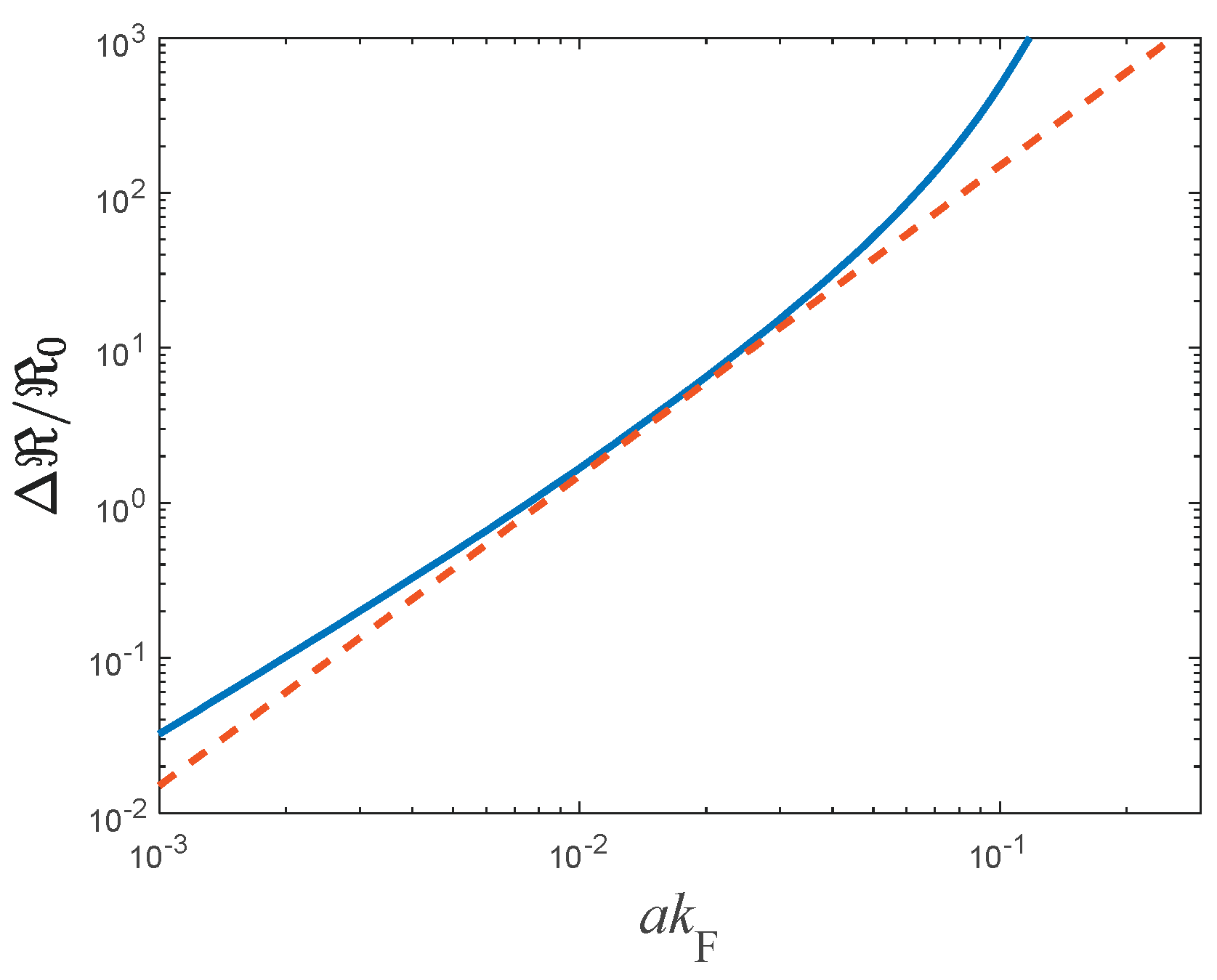

Figure 2 displays the plot against the barrier's normalized width. It can be observed that the approximate expression is consistent with the accurate one over at least an order of magnitude.

4. Experimental Realization

To observe this effect in GaAs/AlGaAs 2DEG we suggest

choosing realistic parameters: electron density

ns = 1 × 10

11 cm−2 and low temperature (

) giving Fermi energy

. Since the electron mass is

then the Fermi wavelength is

[

13]. Choosing wire width

correspond to

modes. Modern MBE and e-beam lithography produce ~2 nm barriers via AlGaAs insertion or split-gate depletion [

14,

15,

16]. Accordingly , we take barrier width

and height

, i.e.

. For these parameters

while

.

These values can eaily be fabricated and measured. In the presence of disorder, finite temperature, or contact resistance fluctuations, extracting

may require careful subtraction of background contributions [

5,

15]. Nonetheless, the predicted

is large enough to appear above such noise floors.

5. Summary

In this work, we have presented a theoretical investigation of electron transport through a two-dimensional (2D) quantum wire containing a narrow but high potential barrier. The system was analyzed under specific conditions: a wide wire () ensuring multiple open transverse modes, and a barrier characterized by extreme parameters ( and ), allowing for its treatment as a short-range scatterer dominating the longitudinal transport.

The central finding is the derivation of an analytical expression for the wire's conductance, performed within the Landauer-Büttiker formalism, that exhibits an unexpected independence from both Planck's constant (h) and the electron density (). Instead, the conductance is found to depend solely on the Fermi energy (), the electron effective mass (), the wire width (w), and the effective strength of the potential barrier (). This result, given by , underscores a unique limit of quantum transport.

The h-independence of the overall conductance is particularly intriguing because the system operates in a profoundly quantum regime, where transport occurs via tunneling through a classically impenetrable barrier. We suggest that while the Fermi energy is undeniably a quantum mechanical concept rooted in the Pauli exclusion principle and state counting, its definition does not, by itself, explicitly rely on the wave-like properties of the electron that are intrinsically tied to h. Thus, the absence of h in our final conductance formula indicates that for this specific set of physical conditions, the 'wave-like' signatures of quantum mechanics, usually manifest through h in the explicit scaling of conductance, appear to be effectively absorbed or cancelled within the energy- and geometry-dependent sum of transmission probabilities. This leads to an emergent transport behavior primarily dictated by the system's energy scale () and scattering strength, rather than the explicit quantum unit of conductance or carrier concentration.

This work sheds new light on an unconventional manifestation within the Landauer framework, demonstrating how the intricate interplay of system geometry and potential characteristics can lead to unexpected forms of scaling in macroscopic observables. Our findings offer a unique perspective on how different facets of quantum mechanics (e.g., state quantization versus wave phenomena) contribute to observable transport properties.

Looking forward, several avenues for future research emerge from these results. It would be valuable to explore whether similar h-independent transport regimes can be found in other low-dimensional systems or with different types of scatterers. Investigating the robustness of this behavior against small deviations from the ideal conditions (e.g., finite barrier width effects, intermediate barrier heights) would also be crucial. Furthermore, our findings could stimulate experimental efforts to detect this intriguing quantum phenomenon, providing empirical validation and potentially opening new pathways for the design of quantum electronic devices with tailored transport characteristics.

References

- Landauer, R. Spatial variation of currents and fields in metal films and surfaces. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1957, 1, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttiker, M. Four-terminal phase-coherent conductance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Beenakker, C.W.J. Random-matrix theory of quantum transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1997, 69, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wees, B.J.; van Houten, H.; Beenakker, C.W.J.; Williamson, J.G.; Kouwenhoven, L.P.; van der Marel, D.; Foxon, C.T. Quantized Conductance of Point Contacts in a Two-Dimensional Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 60, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouwenhoven, L.P.; van Wees, B.J.; Harmans, C.J.P.M.; Williamson, J.G.; van Houten, H.; Beenakker, C.W.J.; Foxon, C.T.; Harris, J.J. Nonlinear Conductance of Quantum Point Contacts. Physical Review B 1989, 39, 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Klitzing, K.; Dorda, G.; Pepper, M. New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, D.C.; Stormer, H.L.; Gossard, A.C. Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouwenhoven, L.P.; Austing, D.; Tarucha, S. Few-electron quantum dots. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2001, 64, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J.; Schroeter, D.F. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, N.W.; Mermi, N.D. Solid State Physics; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Merzbacher, E. Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.H. The Physics of Low-Dimensional Semiconductors: An Introduction; Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tsu, R.; Esaki, L. Tunneling in a Finite Superlattice. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1973, 22, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantram, M.P.; Datta, S. Current-Fluctuation in Mesoscopic Systems with a δ-Function Barrier. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 16390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, C.; Quinn, J.J. Quantum Transport through a Short Barrier in a Wide Quantum Wire. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 15893. [Google Scholar]

- Imry, Y. Introduction to Mesoscopic Physics, 2nd ed.; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).