1. Introduction

Quantum tunneling is ubiquitous in quantum mechanics where a particle has a non-zero probability of passing through a classically forbidden energy barrier, even though it doesn’t have enough energy to overcome that barrier according to classical physics [

1,

2]. This behavior arises from the wave-like nature of particles at the quantum level, and can be thus observed also for classical waves such as light and sound waves (see e.g. [

3,

4,

5,

6]). One of the main predictions of quantum tunneling is the instability and decay of a quantum particle trapped by potential barriers of finite heights, a prototypal example being

-decay in nuclear physics [

7,

8]. Perhaps the simplest one-dimensional quantum mechanical model possessing quasi-stationary (resonance) states, decaying via tunneling leakage, is the double rectangular potential barrier model [

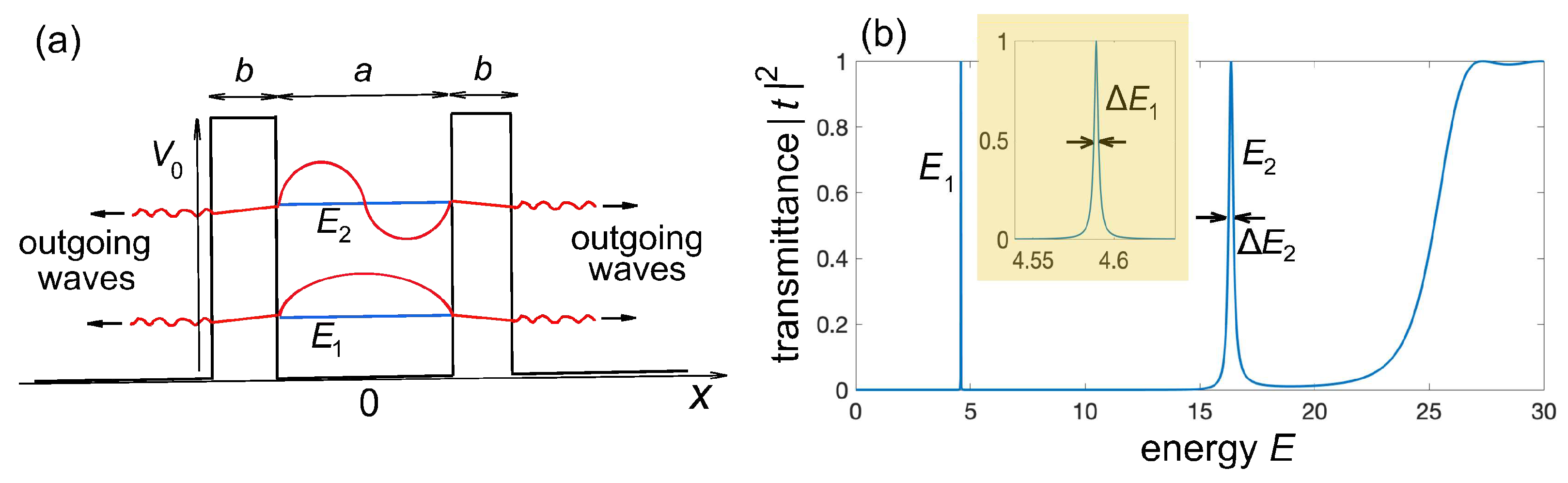

Figure 1(a)], which was introduced in a famous paper by Gamov to model

decay [

7]. When the barrier height

is infinite, the system sustains a set of stationary (non-decaying) bound states at some quantized energies, however when the barrier height

is not infinite some of these states, those with energies close to the bottom of the barriers, become metastable, i.e. they become resonance states (also known as Gamow or Siegert states, or quasi-bound states; see e.g. [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] and references therein). This means that an initial wave function prepared in a bound state of the infinite barrier approximately maintains its shape but decays in time in a nearly exponential manner through tunneling leakage across the barriers, generating small-amplitude outgoing waves that spread outward the barrier region [

9,

10,

11]. The signature of resonance states are the characteristic Breit-Wigner resonance peaks in the transmission spectrum of the double potential barrier, and the lifetimes of the resonance states are of the order of the reciprocal of the widths of the Breit-Wigner resonances [

11] [see

Figure 1(b)].

The quantum decay does not strictly follow a simple exponential decay law, and deviations from an exponential decay universally arise in the short and long time scales [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], leading to Zeno-like dynamics, i.e. the deceleration (Zeno effect) or the acceleration (anti-Zeno effect) of the decay by frequent observations of the system (see, e.g., [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] and references therein). Strong deviations from an exponential decay law are generally observed because of interference between different decay pathways, strong coupling with a featureless bath or with an engineered bath, which introduce memory effects and non-markovian behavior, or in the presence of edge effects or localized states, such as in disordered systems, leading to revivals and limited quantum decay [

26,

27,

28].

Quantum leakage dynamics in the double-barrier potential is clearly modified when lateral barriers are added. Such additional barriers introduce interference effects and make the quantum decay greatly non-exponential rather generally. Naively, one could think that additional barriers would preferentially slow down the decay, since the tunneling is expected to become less probable and because of the back flow into the original excitation region. For example, for stochastic barriers one expects Anderson localization [

29,

30], leading to a highly non-markovian dynamics, Rabi-like oscillations and limited quantum decay [

27,

28,

31]. However, this picture may fail in other cases as multiple interference effects could play in a reversed way.

In this work we unveil the rather counterintuitive effect of quantum decay acceleration of a resonance state in the double barrier model induced by additional later barriers: rather than slowing down the decay, they can greatly accelerate the quantum decay, even when the height of barriers are unbounded. This unusual phenomenon is explained in terms of resonant tunneling (hopping) and studied by considering in details the decay of resonance states in potential barriers on a tight-binding lattice, which can be emulated in photonic settings using evanescently-coupled optical waveguide lattices [

32,

33,

34] or grating structures [

35,

36,

37].

2. Acceleration and deceleration of quantum decay in the double barrier model: some preliminary considerations

Before considering quantum decay in tight-binding models with on-site potential barriers, it is worth presenting some preliminary results and discussion on the decay dynamics of resonance states in the Gamov’s model for the continuous Schrödinger equation in one spatial dimension, which is written in dimensionless units as

where

is the wave function and

is the potential. Let us first assume that

describes a double rectangular barrier, with barrier height

, barrier width

b and barrier distance

[

Figure 1(a)].

Figure 1(b) shows a typical behavior of spectral transmittance

versus energy

E of the incidence plane wave. The transmission amplitude

can be calculated by standard textbook methods and reads

where

and

are the reflection and transmission amplitudes of the single barrier, given by

and

The spectral transmittance clearly shows resonance peaks at some energies [two peaks at energies

in the plot of

Figure 1(b)], which correspond to quasi bound states. In the high-barrier limit, i.e. very narrow resonances [such as the first resonance at

shown in the inset of

Figure 1(b)], the resonance curve is Lorentzian-shaped to a high degree of approximation (Breit-Wigner resonance) and the corresponding quasi bound state can be roughly speaking written as

where

,

E are close to the bound state wave function and corresponding (possibly shifted) eigenenergy in the infinite

limit,

is the lifetime of the quasi bound state,

is the full-width at half-maximum of the Breit-Wigner resonance, and

describes the small-amplitude outgoing waves in the outer regions of the barriers [see

Figure 1(a)]. An example of a nearly-exponential decay of the lowest resonance state is shown in

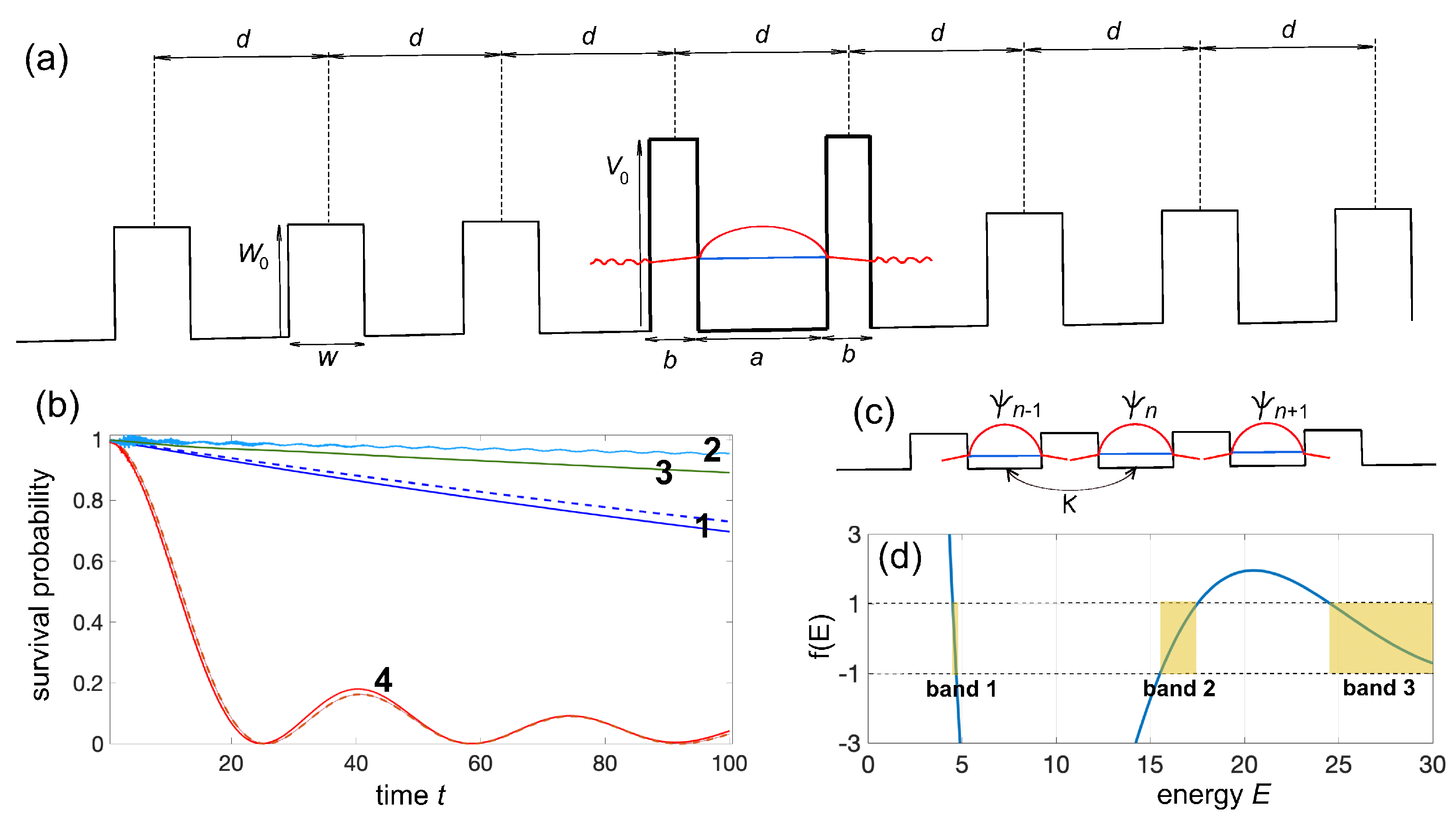

Figure 2(b), which depicts the decay behavior of the survival probability to find the particle between the two barriers,

normalized to its initial value

. Here,

is assumed to be close to the lowest-energy bound state of the same barrier model but with

, i.e.

for

and

otherwise, propagated for a short time interval (

) to remove fast transient oscillations in the behavior of

. The results are obtained by numerical integration of the time-dependent Schrödinger Equation (

1) using an accurate pseudospectral split-step method. The decay dynamics [solid curve 1 in

Figure 2(b)] is quite well fitted by an exponential curve [dashed curve 1 in

Figure 2(b)] with a lifetime close to the theoretical value

predicted from the spectral width

of the lowest Breit-Wigner resonance peak. A similar behavior is found when the system is initially prepared in the second resonance state, i.e.

for

and

otherwise, the exponential decay displaying a much shorter lifetime (

), according to the larger width

of the second resonance peak in

Figure 1(b).

Clearly, the decay dynamics is greatly modified and can largely deviate from an exponential law when we consider additional lateral barriers, because the outgoing waves that escape via tunneling from the two barriers can be back reflected and re-injected into the original spatial region

. The final decay law

is the result of a complex multiple interference process which, depending on the choice of the additional barriers, can either decelerate or accelerate the decay. The fact that additional barriers can slow down the decay of the survival probability is not surprising, however it is more elusive how and why the decay can be accelerated in some cases. One of the main mechanism that explains decay acceleration is

resonant tunneling (see e.g. [

38]). This point can be illustrated by considering, as an example, the case of an array of equally-spaced barriers; see

Figure 2(a). Besides the two barriers as in

Figure 1(a), we now add a sequence of equally-spaced barriers of height

, same space separation

, and barrier width

w. Barrier height

and width

w can be rather generally different than

and

a. Curves 2 and 3 in

Figure 2(b) show the decay dynamics of the survival probability when either or both

w and

differ than

b and

, clearly indicating that the additional barriers decelerate the decay. However, a striking effect is observed when

and

: the decay of survival probability is much faster and the decay dynamics greatly deviates from an exponential law [curve 4 in

Figure 2(b)]. The decay acceleration can be explained on the basis of resonant tunneling (hopping) between resonant quasi bound states that are sustained by adjacent double-potential barriers, as schematically shown in

Figure 2(c). In fact, for

and

the potential

is strictly periodic with period

, and such a periodic potential corresponds to the well-known Kronig-Penney model in solid-state physics [

39,

40]. Basically, the various resonant quasi-bound states sustained in adjacent double-barriers hybridize and give rise to a set of bands. The dispersion curves

of the various bands are defined implicitly by the relation (see e.g. [

40])

where we have set

In the above equation,

k is the Bloch wave number, which varies in the first Brillouin zone

. The band dispersion curves, defined by the relation

, can be solved graphically, as shown in

Figure 2(d). The low-energy narrow-band in

Figure 2(d), indicated as band 1 and centered at around

, arises from the weak overlapping (hybridization) of resonant quasi-bound states with energies

in adjacent unit cells of the crystal, and its bandwidth

defines the hopping amplitude

between adjacent sites within a tight-binding description. In the nearest-neighbor approximation, an initial excitation of one of such quasi-bound mode can jump from one unit cell to its neighbor in either direction with a rate

, and the spreading dynamics is ballistic and governed by the set of coupled equations (see e.g. [

40,

41,

42] )

where

is the amplitude of the quasi bound state at the

n-th unit cell. The decay behavior of the survival probability is then given analytically in terms of

Bessel function, namely [

41]

The solid curve 4 in

Figure 2(b) shows the numerically-computed behavior of

for

and

, which is very well fitted by the theoretical prediction given by Eq.(10) (dashed curve 4), in which the hopping rate

is estimated from the width of the narrow band of

Figure 2(d). Clearly, the decay of survival probability greatly deviates from an exponential curve and in the early stage it is much faster than other cases [curves 1-3 in

Figure 2(b)], where resonant tunneling is prevented: the hopping dynamics enabled by resonant tunneling makes the decay faster.

3. Decay acceleration by resonant tunneling in tight-binding lattices

The phenomenon of decay acceleration in the early stage of the dynamics mediated by hopping between adjacent resonant quasi bound states, discussed in the previous section, suggests to re-examine quantum decay and tunneling effects in the framework of simple tight-binding models [

32,

43,

44]. Such models, besides to be simpler to study and simulate, can be readily implemented in photonic settings using engineered arrays of evanescently-coupled optical waveguides. In fact, they have served over the past two decades as feasible laboratory tools for the observation of non-exponential decay features and Zeno dynamics with photons [

5,

33,

34,

45,

46,

47]. The simplest two-barrier system sustaining one resonance state on a tight-binding lattice is described by the Hamiltonian [

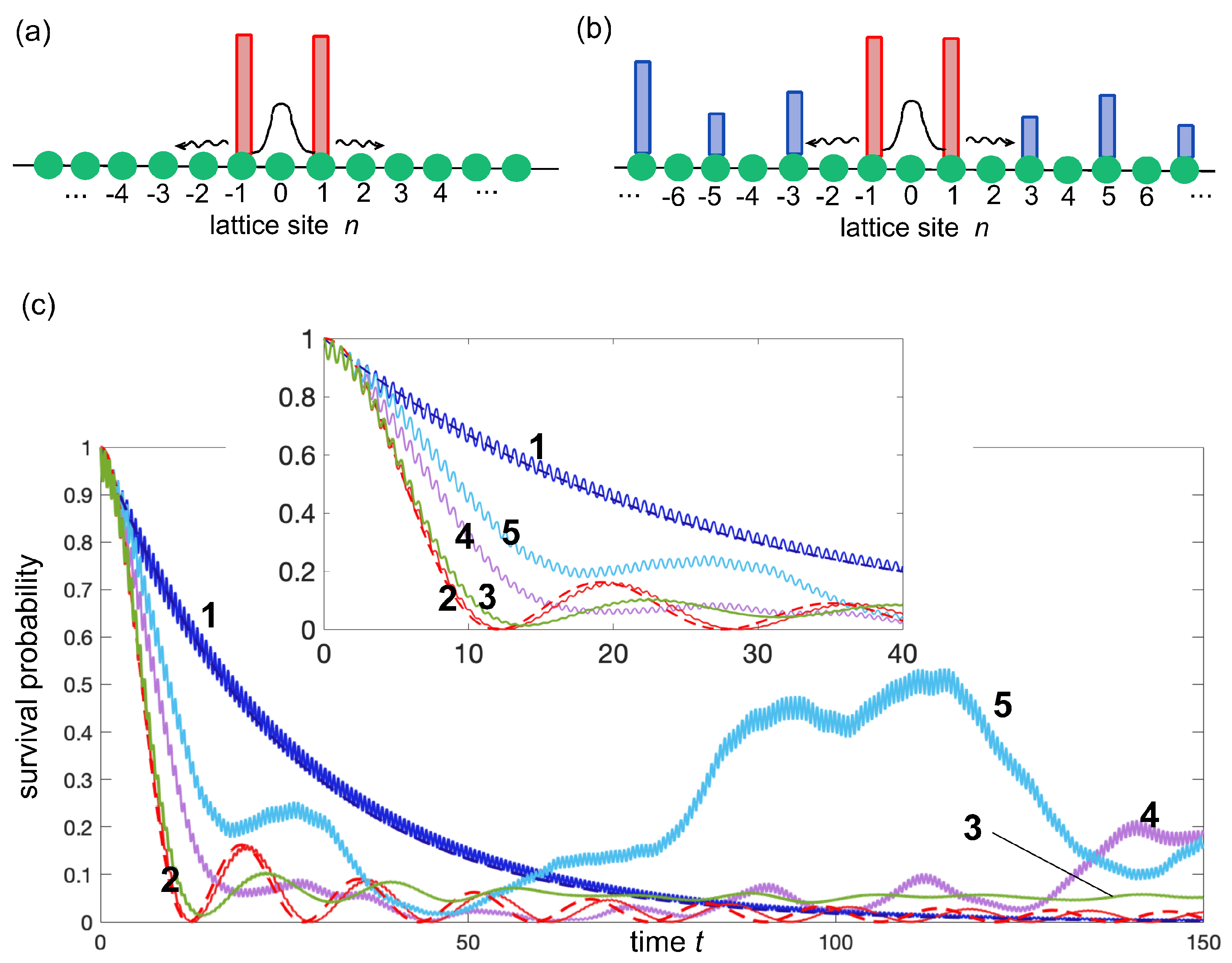

Figure 3(a)]

where

is the hopping rate between adjacent sites of the lattice and

is the on-site potential barrier at the two sites

. For the sake of definiteness we assume

, however on a lattice a quasi bound state is also sustained for

. Indicating by

the wave amplitude at the

n-th lattice site, i.e. after letting

, the Schrödinger equation

yields the set of coupled equations

In the high-barrier limit

, an initial excitation at time

of site

, trapped between the two high potential barriers, is metastable and the survival probability,

, decays in time nearly exponentially, as observed in numerical simulations of Eqs.(12) assuming the initial conditions

; see curve 1 in

Figure 3(c). Note that a small-amplitude and fast oscillation is superimposed to the exponential decay, the amplitude of the oscillations vanishing in the

limit. The lifetime of the quasi-bound state at site

can be readily estimated by adiabatic elimination from the dynamics of the small amplitudes at the sites

. In fact, in the high barrier limit

one can assume in Eqs.(12)

,and thus

Taking into account for symmetry reasons that

, after letting

and

for

, from Eqs.(12) and (13) one obtains

where we have set

The reduced model (14) can be cast in the standard Friedrichs-Lee (or Fano-Anderson) model, describing the decay of a single bound state weakly coupled to a featureless tight-binding continuum (see e.g. [

34,

48,

49]), and in the markovian approximation the survival probability can be calculated as

where the lifetime

is given by (see Appendix A for details)

The exponential decay predicted by Eqs.(16) and (17) turns out to be in good agreement with the exact decay behavior found by numerical simulations [compare solid and dashed curves 1 in the inset of

Figure 3(c)].

When lateral barriers are introduced, the decay dynamics is rather generally modified and does not follow anymore the exponential law Eq.(16). In order to observe decay acceleration by resonant tunneling as suggested in Sec.2 above, the potential barriers are added at odd potential sites solely; see

Figure 3(b). The Hamiltonian of the system reads

where

is the strength of the potential barrier at odd lattice sites, with

and

for

n even. We mention that in photonics the tight-binding model (18) can be implemented using arrays of evanescently coupled optical waveguides, in which a uniform coupling constant

and engineered propagation constant shifts

are realized by judicious design of waveguide widths and spacing. For example, a linear gradient potential was realized in semiconductor waveguide arrays to demonstrate optical Bloch oscillations in Ref. [

50].

After adiabatic elimination of the small amplitudes

as discussed above [Eq.(13)], the decay dynamics of

could be framed in the form of a single-level Fano-Anderson model, where the additional barriers

clearly structure the continuum of states into which the state

is coupled, and could induce localization phenomena responsible for strong backflow and revivals in the dynamics [

26,

27,

28]. It is precisely these effects that make it possible decay acceleration in the early stage of the dynamics. The canonical Fano-Anderson form describing the decay process for the Hamiltonian (18) is detailed in the Appendix A, which derives the general form of the memory function entering in the integro-differential equation describing the decay dynamics of the amplitude

. The memory function basically includes all the multiple reflection phenomena and delay effects arising from wave scattering of additional lateral barriers, which make the decay strongly non-markovian. The form of the memory function depends in a complex way on the eigenstates of the bath Hamiltonian, and even if its form might be calculated analytically in very special cases [

51], it is hard to provide general insights into the decay dynamics as governed by the integro differential equation. However, for our purposes we do not need to resort to the canonical Fano-Anderson model and in the following analysis we will provide some direct examples of quantum decay acceleration adopting the full Hamiltonian (18). To this aim, it is worth noting that the system described by Eq.(18) is bipartite, and thus one can write the wave function as

. The evolution equations for the wave amplitudes

and

at even and odd lattice sites read

which should be solved with the initial condition

and

.

Let us now discuss a few prototypal examples of decay acceleration, observed in the early stage of the dynamics, induced by the additional lateral barriers.

(i) The first example of decay acceleration is obtained by assuming

for

n odd, which is the discrete analogue of the Kronig-Penney model considered in the previous section [

Figure 2(c)]. In this case the Hamiltonian (18) describes a bipartite lattice sustaining two bands. In the high barrier limit

, to calculate the decay of the survival probability we can adiabatically eliminate the small amplitudes

from the dynamics by letting

so that from Eq.(19) one obtains

where we have set

The solution to Eq.(22) with the initial condition

is given in terms of Bessel

function [

41,

42] and the corresponding decay behavior of the survival probability reads

Curve 2 in

Figure 3(c) shows the numerically-computed decay behavior of

for

, which turns out to be quite well fitted by the theoretical prediction given by Eq.(24). Clearly, the decay largely deviates from an exponential law and, most importantly, it is accelerated as compared to curve 1, at least in the early-to-intermediate time scale of the decay.

(ii) As a second example of decay acceleration, let us assume that at odd sites

n, with

, the potential

can take two possible values, either

or

, with probabilities

p and

, respectively (Bernoulli model [

52]). Curve 3 in

Figure 3(c) shows the numerically-computed decay behavior of the survival probability for

,

,

and

, averaged over 200 realizations. Also in this case one can clearly observe an acceleration of the decay in the early stage of the dynamics, in spite of Anderson localization can take place in this model (see Appendix B). This means that, unlike the previous example (i), at long times the decay is not complete.

(iii) The third example of decay acceleration concerns with deterministic potential barriers with continuously-increasing and unbounded heights, namely we assume symmetric Stark potential barriers with

and

Curve 4 in

Figure 3(c) shows the numerically-computed behavior of the survival probability

for

and

, clearly showing the acceleration of the decay in early stage of the decay. This is a rather striking and unexpected result, given that the added barriers have a monotonously increasing and unbounded height and the corresponding Hamiltonian (18) has an almost pure point spectrum with localized eigenstates (see Appendix B and [

53]).

(iv) The fourth example of decay acceleration is analogous to the previous case, but with a quadratic (rather than linear) increase of barrier heights, i.e. we assume

and

Curve 5 in

Figure 3(c) shows the numerically-computed behavior of the survival probability

for

and

, clearly showing the acceleration of the decay in early stage, with strong revival at longer times.

It should be remarked that decay acceleration mediated by the resonant tunneling effect, observed in all above models, occurs only in the early stage of the dynamics, as shown in

Figure 3(c). In fact, at long times the the survival probability

can become smaller when there are no additional lateral barriers, because the backflow arising from multiple scattering processes and localization effects, responsible for strong non-markovianity and deviation of the decay from an exponential curve, induce revival effects in the survival probability, which are prevented in the simple two-barrier case.