Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

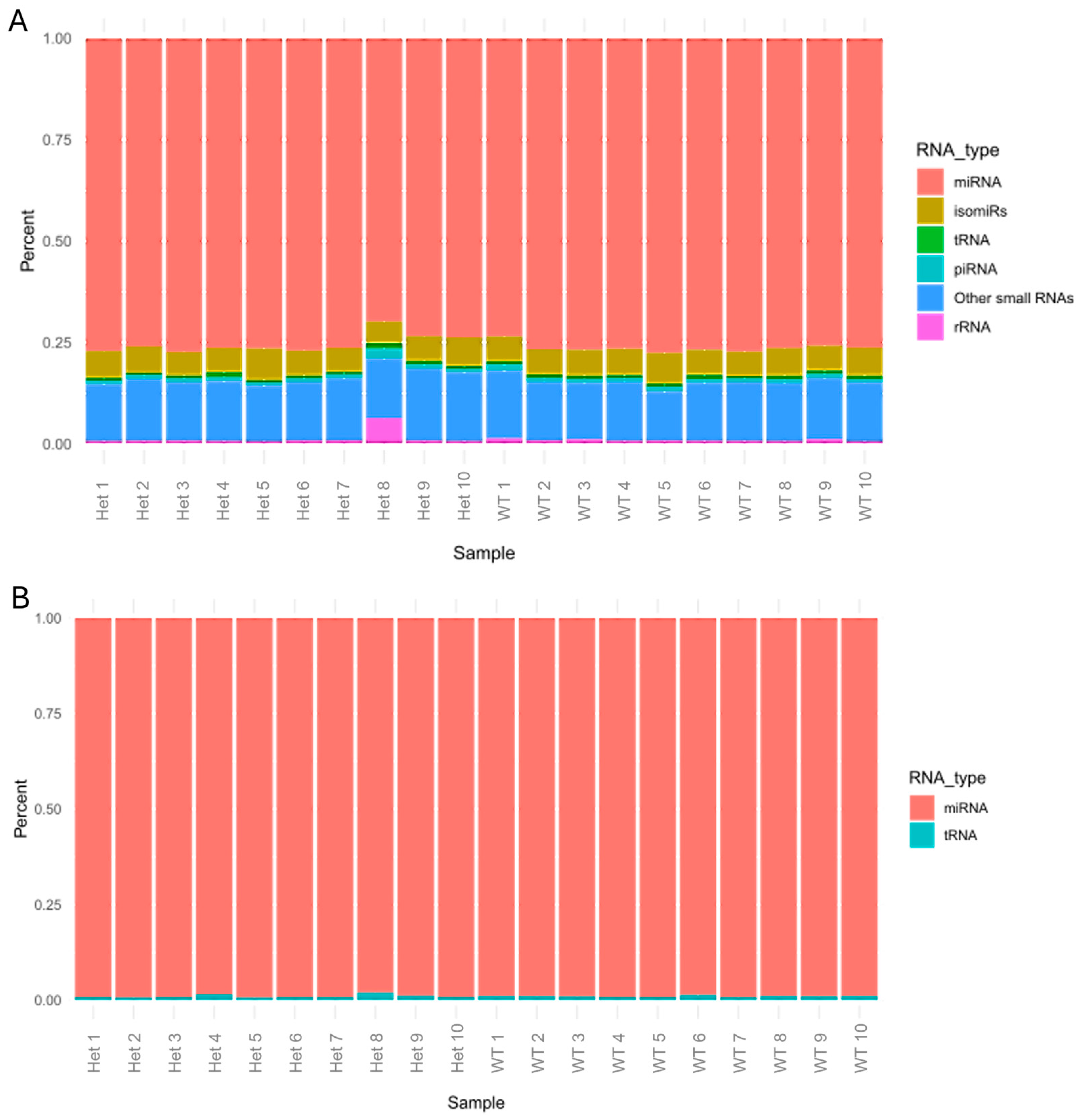

2.1. Distribution of Small RNAs in Our Samples

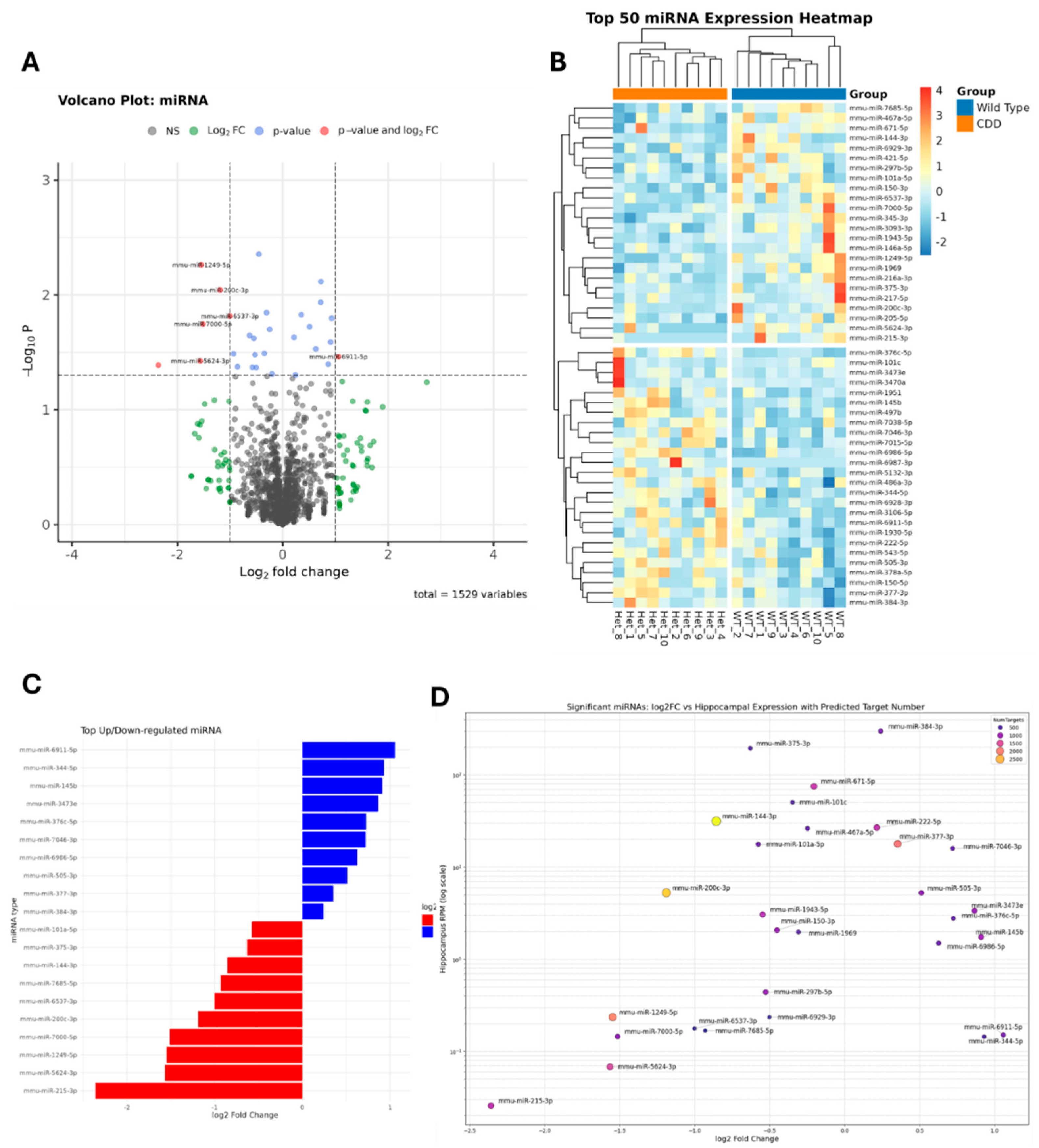

2.1.1. Dysregulated microRNAs

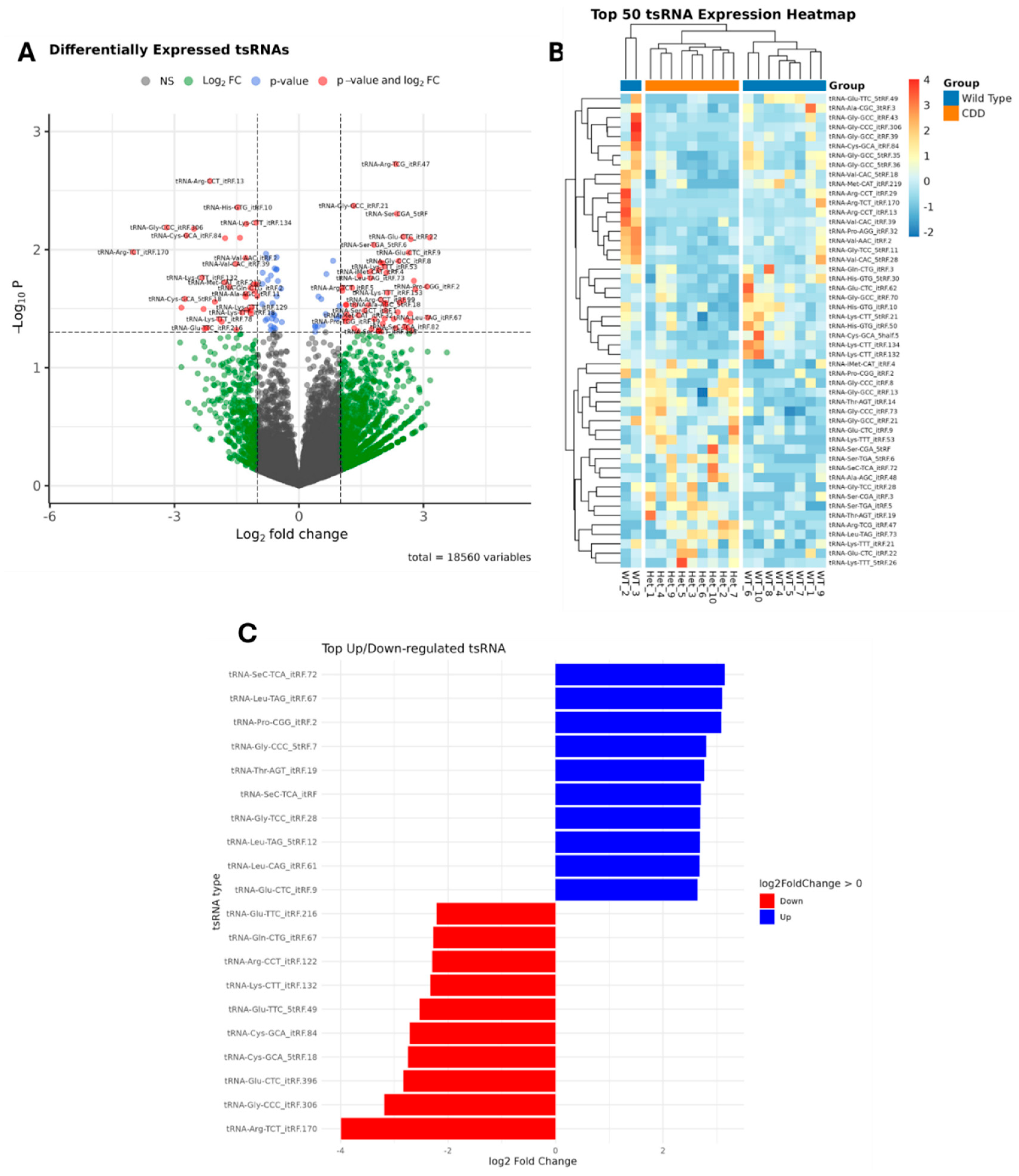

2.1.1. Transfer RNA

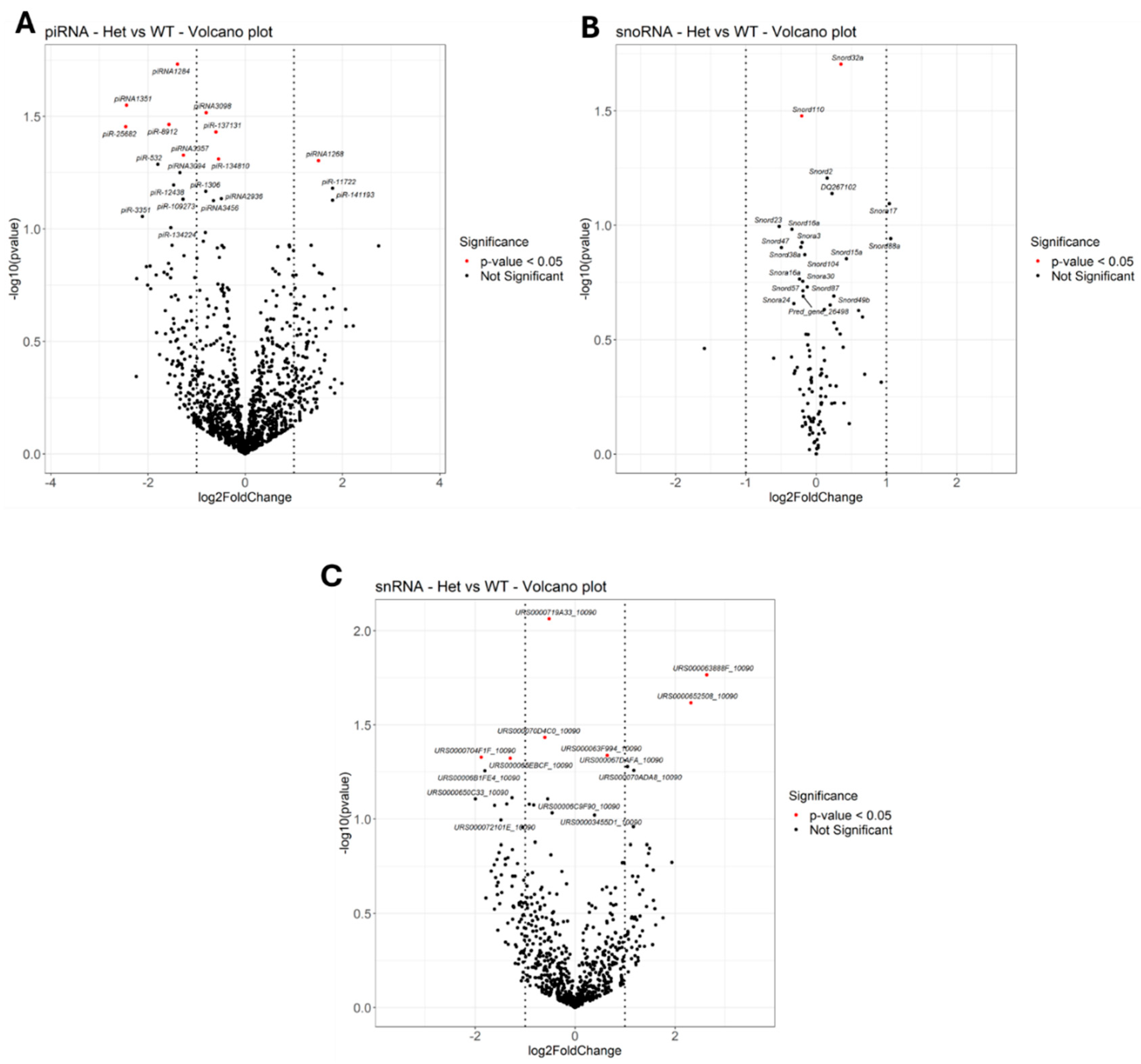

2.1.3. Other Small ncRNAs

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Care and Ethical Approval

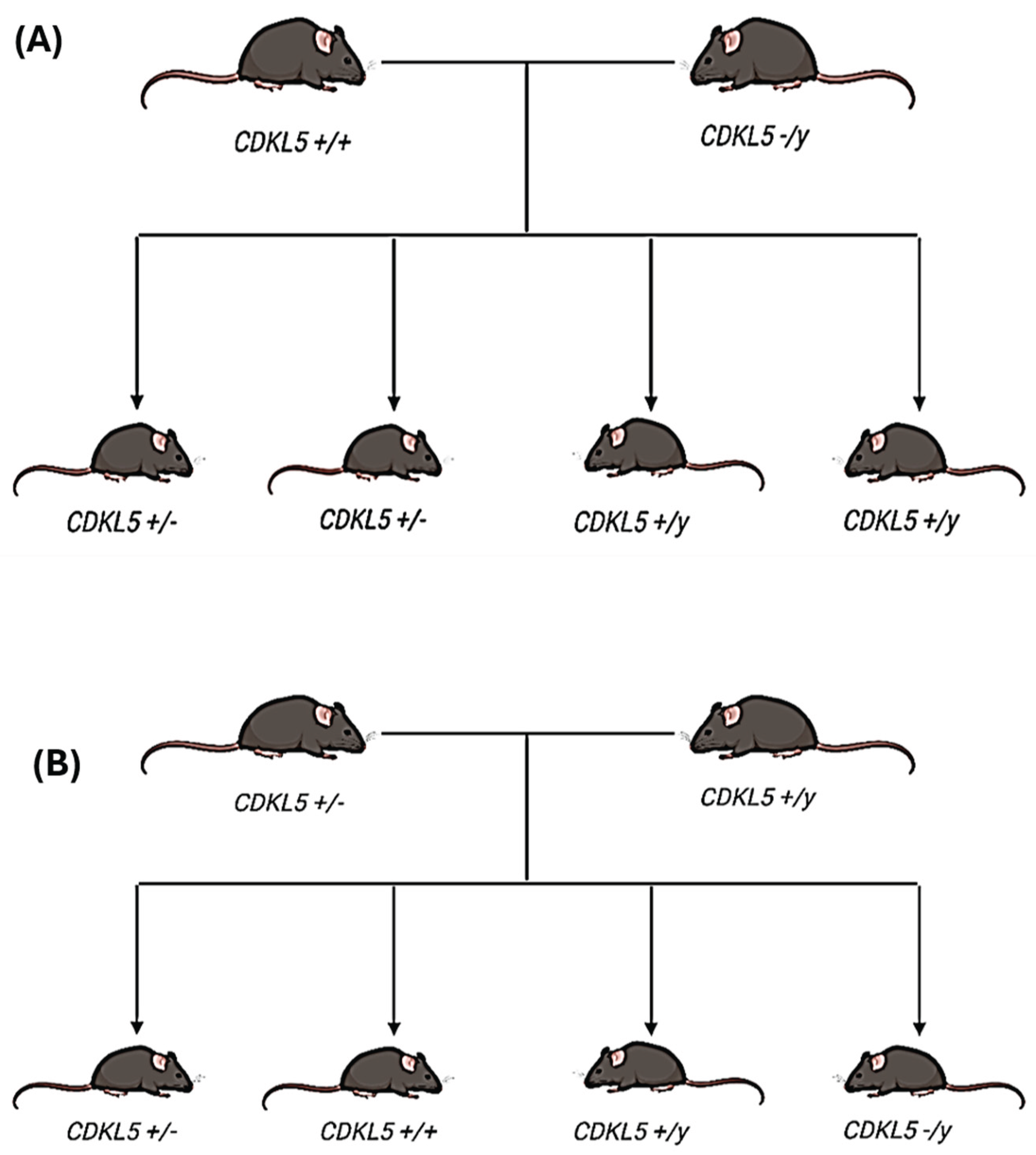

4.2. Animal Model Used in the Study

4.3. Small RNA Sequencing of Hippocampal Tissue

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leonard H, Downs J, Benke TA, Swanson L, Olson H, Demarest S. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(6):563–76. [CrossRef]

- Demarest ST, Olson HE, Moss A, Pestana-Knight E, Zhang X, Parikh S, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: Relationship between genotype, epilepsy, cortical visual impairment, and development. Epilepsia. 2019;60(8):1733–42.

- Fehr S, Wilson M, Downs J, Williams S, Murgia A, Sartori S, et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(3):266–73. [CrossRef]

- Daniels C, Greene C, Smith L, Pestana-Knight E, Demarest S, Zhang B, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder and other infantile-onset genetic epilepsies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2024;66(4):456–68.

- Lindy AS, Stosser MB, Butler E, Downtain-Pickersgill C, Shanmugham A, Retterer K, et al. Diagnostic outcomes for genetic testing of 70 genes in 8565 patients with epilepsy and neurodevelopmental disorders. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1062–71.

- Demarest S, Pestana-Knight EM, Olson HE, Downs J, Marsh ED, Kaufmann WE, et al. Severity assessment in CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;97:38–42. [CrossRef]

- Benke TA, Demarest S, Angione K, Downs J, Leonard H, Saldaris J, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder. GeneReviews®[Internet]. 2024;

- Amin S, Monaghan M, Aledo-Serrano A, Bahi-Buisson N, Chin RF, Clarke AJ, et al. International consensus recommendations for the assessment and management of individuals with CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Front Neurol. 2022;13:874695.

- Van Bergen NJ, Massey S, Quigley A, Rollo B, Harris AR, Kapsa RMI, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: molecular insights and mechanisms of pathogenicity to fast-track therapeutic development. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022;50(4):1207–24.

- Katayama S, Sueyoshi N, Inazu T, Kameshita I. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-Like 5 (CDKL5): Possible Cellular Signalling Targets and Involvement in CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Neural Plast. 2020;2020(1):6970190.

- Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Rusconi L, La Montanara P, Ciceri D, Bergo A, Bedogni F, et al. What we know and would like to know about CDKL5 and its involvement in epileptic encephalopathy. Neural Plast. 2012;2012(1):728267.

- Szafranski P, Golla S, Jin W, Fang P, Hixson P, Matalon R, et al. Neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioral characteristics in males and females with CDKL5 duplications. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(7):915–21.

- Hao S, Wang Q, Tang B, Wu Z, Yang T, Tang J. CDKL5 deficiency augments inhibitory input into the dentate gyrus that can be reversed by deep brain stimulation. J Neurosci. 2021;41(43):9031–46. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Eilbeck K, Smith B, Blake JA, Dou D, Huang W, et al. The development of non-coding RNA ontology. Int J Data Min Bioinform. 2016;15(3):214–32.

- Ulitsky I. Interactions between short and long noncoding RNAs. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(17):2874–83.

- Dupuis-Sandoval F, Poirier M, Scott MS. The emerging landscape of small nucleolar RNAs in cell biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6(4):381–97.

- Luteijn MJ, Ketting RF. PIWI-interacting RNAs: from generation to transgenerational epigenetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(8):523–34.

- Brennan GP, Henshall DC. MicroRNAs as regulators of brain function and targets for treatment of epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(9):506–19.

- Henshall DC, Hamer HM, Pasterkamp RJ, Goldstein DB, Kjems J, Prehn JHM, et al. MicroRNAs in epilepsy: pathophysiology and clinical utility. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(13):1368–76. [CrossRef]

- Mohr AM, Mott JL. Overview of microRNA biology. In: Seminars in liver disease. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2015. p. 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466(7308):835–40.

- Helwak A, Kudla G, Dudnakova T, Tollervey D. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell. 2013;153(3):654–65.

- Mathew BA, Katta M, Ludhiadch A, Singh P, Munshi A. Role of tRNA-derived fragments in neurological disorders: a review. Mol Neurobiol. 2023;60(2):655–71.

- Lv X, Zhang R, Li S, Jin X. tRNA Modifications and Dysregulation: Implications for Brain Diseases. Brain Sci. 2024;14(7):633.

- Zhu L, Liu X, Pu W, Peng Y. tRNA-derived small non-coding RNAs in human disease. Cancer Lett. 2018;419:1–7.

- Jia Y, Tan W, Zhou Y. Transfer RNA-derived small RNAs: potential applications as novel biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(17):1092.

- Blaze J, Akbarian S. The tRNA regulome in neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27(8):3204–13.

- Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43(4):613–23.

- Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, Dawra N, Tisdale S, Kedersha N, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(14):10959–68. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science (80- ). 2016;351(6271):397–400.

- Dhahbi JM, Spindler SR, Atamna H, Yamakawa A, Boffelli D, Mote P, et al. 5′ tRNA halves are present as abundant complexes in serum, concentrated in blood cells, and modulated by aging and calorie restriction. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:1–14.

- Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(2):94–108. [CrossRef]

- Kuscu C, Kumar P, Kiran M, Su Z, Malik A, Dutta A. tRNA fragments (tRFs) guide Ago to regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally in a Dicer-independent manner. Rna. 2018;24(8):1093–105. [CrossRef]

- Keam SP, Hutvagner G. tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs): emerging new roles for an ancient RNA in the regulation of gene expression. Life. 2015;5(4):1638–51.

- Sobala A, Hutvagner G. Transfer RNA-derived fragments: origins, processing, and functions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011;2(6):853–62.

- Dieci G, Preti M, Montanini B. Eukaryotic snoRNAs: a paradigm for gene expression flexibility. Genomics. 2009;94(2):83–8.

- Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(12):861–74. [CrossRef]

- Huang Z hao, Du Y ping, Wen J tao, Lu B feng, Zhao Y. snoRNAs: functions and mechanisms in biological processes, and roles in tumor pathophysiology. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):259.

- Ozata DM, Gainetdinov I, Zoch A, O’Carroll D, Zamore PD. PIWI-interacting RNAs: small RNAs with big functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(2):89–108.

- Wang J, Shi Y, Zhou H, Zhang P, Song T, Ying Z, et al. piRBase: integrating piRNA annotation in all aspects. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D265–72.

- Stoyko D, Genzor P, Haase AD. Hierarchical length and sequence preferences establish a single major piRNA 3′-end. Iscience. 2022;25(6).

- Perera BPU, Tsai ZTY, Colwell ML, Jones TR, Goodrich JM, Wang K, et al. Somatic expression of piRNA and associated machinery in the mouse identifies short, tissue-specific piRNA. Epigenetics. 2019;14(5):504–21.

- Wang X, Ramat A, Simonelig M, Liu MF. Emerging roles and functional mechanisms of PIWI-interacting RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(2):123–41.

- Czech B, Munafò M, Ciabrelli F, Eastwood EL, Fabry MH, Kneuss E, et al. piRNA-guided genome defense: from biogenesis to silencing. Annu Rev Genet. 2018;52(1):131–57.

- Mirzaei S, Gholami MH, Hushmandi K, Hashemi F, Zabolian A, Canadas I, et al. The long and short non-coding RNAs modulating EZH2 signaling in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):18. [CrossRef]

- Aalto AP, Pasquinelli AE. Small non-coding RNAs mount a silent revolution in gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24(3):333–40.

- Redis RS, Calin GA. SnapShot: non-coding RNAs and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017;25(1):220.

- E Nicolas F. Role of ncRNAs in development, diagnosis and treatment of human cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2017;12(2):128–35.

- Karnati HK, Panigrahi MK, Gutti RK, Greig NH, Tamargo IA. miRNAs: key players in neurodegenerative disorders and epilepsy. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015;48(3):563–80.

- Nwaobi SE, Lin E, Peramsetty SR, Olsen ML. DNA methylation functions as a critical regulator of Kir4. 1 expression during CNS development. Glia. 2014;62(3):411–27.

- Petazzi P, Sandoval J, Szczesna K, Jorge OC, Roa L, Sayols S, et al. Dysregulation of the long non-coding RNA transcriptome in a Rett syndrome mouse model. RNA Biol. 2013;10(7):1197–203. [CrossRef]

- Obiols-Guardia A, Guil S. The role of noncoding RNAs in neurodevelopmental disorders: the case of Rett syndrome. Neuroepigenomics aging Dis. 2017;23–37.

- Wang ITJ, Allen M, Goffin D, Zhu X, Fairless AH, Brodkin ES, et al. Loss of CDKL5 disrupts kinome profile and event-related potentials leading to autistic-like phenotypes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(52):21516–21.

- Rishik S, Hirsch P, Grandke F, Fehlmann T, Keller A. miRNATissueAtlas 2025: an update to the uniformly processed and annotated human and mouse non-coding RNA tissue atlas. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(D1):D129–37. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D127–31.

- Schroeder E, Yuan L, Seong E, Ligon C, DeKorver N, Gurumurthy CB, et al. Neuron-type specific loss of CDKL5 leads to alterations in mTOR signaling and synaptic markers. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(6):4151–62.

- Zhu ZA, Li YY, Xu J, Xue H, Feng X, Zhu YC, et al. CDKL5 deficiency in adult glutamatergic neurons alters synaptic activity and causes spontaneous seizures via TrkB signaling. Cell Rep. 2023;42(10). [CrossRef]

- Silvestre M, Dempster K, Mihaylov SR, Claxton S, Ultanir SK. Cell type-specific expression, regulation and compensation of CDKL5 activity in mouse brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;1–13. [CrossRef]

- Eddy SR. Non–coding RNA genes and the modern RNA world. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2(12):919–29.

- Chen Y, Mateski J, Gerace L, Wheeler J, Burl J, Prakash B, et al. Non-coding RNAs and neuroinflammation: implications for neurological disorders. Exp Biol Med. 2024;249:10120.

- Wang SW, Liu Z, Shi ZS. Non-coding RNA in acute ischemic stroke: mechanisms, biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Cell Transplant. 2018;27(12):1763–77.

- Salvatori B, Biscarini S, Morlando M. Non-coding RNAs in nervous system development and disease. Front cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:273.

- Siqueira E, Velasco CD, Tarrasón A, Soler M, Srinivas T, Setién F, et al. NEAT1-mediated regulation of proteostasis and mRNA localization impacts autophagy dysregulation in Rett syndrome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(4):gkaf074.

- Henshall DC. MicroRNAs Fine-Tune Brain and Body Communication in Health and Disease. Brain-Body Connect. 2025;311–37.

- Mari F, Azimonti S, Bertani I, Bolognese F, Colombo E, Caselli R, et al. CDKL5 belongs to the same molecular pathway of MeCP2 and it is responsible for the early-onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(14):1935–46.

- Carouge D, Host L, Aunis D, Zwiller J, Anglard P. CDKL5 is a brain MeCP2 target gene regulated by DNA methylation. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38(3):414–24.

- Urdinguio RG, Fernandez AF, Lopez-Nieva P, Rossi S, Huertas D, Kulis M, et al. Disrupted microRNA expression caused by Mecp2 loss in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Epigenetics. 2010;5(7):656–63. [CrossRef]

- Ashhab MU, Omran A, Gan N, Kong H, Peng J, Yin F. microRNA s (9, 138, 181A, 221, and 222) and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in developing brains. Transl Neurosci. 2013;4(3):357–62.

- Yousefi MJ, Rezvanimehr A, Saleki K, Mehrani A, Barootchi E, Ramezankhah M, et al. Inflammation-related microRNA alterations in epilepsy: a systematic review of human and animal studies. Rev Neurosci. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Rajabi M, Kalantar SM, Mojodi E, Salehi M, Firouzabadi RD, Etemadifar SM, et al. Assessment of circulating miRNA-218, miRNA-222, and miRNA-146 as biomarkers of polycystic ovary syndrome in epileptic patients receiving valproic acid. Biomed Res Ther. 2023;10(9):5884–95.

- Szydlowska K, Bot A, Nizinska K, Olszewski M, Lukasiuk K. Circulating microRNAs from plasma as preclinical biomarkers of epileptogenesis and epilepsy. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):708.

- Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Höchsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. Rna. 2004;10(10):1507–17.

- Vorozheykin PS, Titov II. Web server for prediction of miRNAs and their precursors and binding sites. Mol Biol. 2015;49:755–61.

- Christopher AF, Kaur RP, Kaur G, Kaur A, Gupta V, Bansal P. MicroRNA therapeutics: discovering novel targets and developing specific therapy. Perspect Clin Res. 2016;7(2):68–74.

- Hogg MC, Raoof R, El Naggar H, Monsefi N, Delanty N, O’Brien DF, et al. Elevation of plasma tRNA fragments precedes seizures in human epilepsy. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(7):2946–51.

- Jirström E, Matveeva A, Baindoor S, Donovan P, Ma Q, Morrissey EP, et al. Effects of ALS-associated 5’tiRNAGly-GCC on the transcriptomic and proteomic profile of primary neurons in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2025;385:115128.

- Schaffer AE, Pinkard O, Coller JM. tRNA metabolism and neurodevelopmental disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20(1):359–87.

- McArdle H, Hogg MC, Bauer S, Rosenow F, Prehn JHM, Adamson K, et al. Quantification of tRNA fragments by electrochemical direct detection in small volume biofluid samples. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7516.

- Fagan SG, Helm M, Prehn JHM. tRNA-derived fragments: A new class of non-coding RNA with key roles in nervous system function and dysfunction. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;205:102118.

- Kapur M, Ganguly A, Nagy G, Adamson SI, Chuang JH, Frankel WN, et al. Expression of the Neuronal tRNA n-Tr20 Regulates Synaptic Transmission and Seizure Susceptibility. Neuron. 2020 Oct;108(1):193-208.e9. [CrossRef]

- Karijolich J, Yu YT. Spliceosomal snRNA modifications and their function. RNA Biol. 2010;7(2):192–204. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Huang R, Lai Y. Expression signature of ten small nuclear RNAs serves as novel biomarker for prognosis prediction of acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18489.

- Matera AG, Terns RM, Terns MP. Non-coding RNAs: lessons from the small nuclear and small nucleolar RNAs. Nat Rev Mol cell Biol. 2007;8(3):209–20.

- Watkins NJ, Bohnsack MT. The box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs: key players in the modification, processing and the dynamic folding of ribosomal RNA. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3(3):397–414.

- Ruggero D, Pandolfi PP. Does the ribosome translate cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(3):179–92. [CrossRef]

- Falaleeva M, Stamm S. Processing of snoRNAs as a new source of regulatory non-coding RNAs: snoRNA fragments form a new class of functional RNAs. Bioessays. 2013;35(1):46–54.

- Zhong F, Zhou N, Wu K, Guo Y, Tan W, Zhang H, et al. A SnoRNA-derived piRNA interacts with human interleukin-4 pre-mRNA and induces its decay in nuclear exosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(21):10474–91.

- Ricciardi S, Ungaro F, Hambrock M, Rademacher N, Stefanelli G, Brambilla D, et al. CDKL5 ensures excitatory synapse stability by reinforcing NGL-1–PSD95 interaction in the postsynaptic compartment and is impaired in patient iPSC-derived neurons. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(9):911–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhao P ping, Yao M jin, Chang S yuan, Gou L tao, Liu M fang, Qiu Z long, et al. Novel function of PIWIL1 in neuronal polarization and migration via regulation of microtubule-associated proteins. Mol Brain. 2015;8:1–12.

- Ghosheh Y, Seridi L, Ryu T, Takahashi H, Orlando V, Carninci P, et al. Characterization of piRNAs across postnatal development in mouse brain. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):25039.

- Nandi S, Chandramohan D, Fioriti L, Melnick AM, Hébert JM, Mason CE, et al. Roles for small noncoding RNAs in silencing of retrotransposons in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(45):12697–702. [CrossRef]

- Leighton LJ, Wei W, Marshall PR, Ratnu VS, Li X, Zajaczkowski EL, et al. Disrupting the hippocampal Piwi pathway enhances contextual fear memory in mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2019;161:202–9.

- Yang Z, Chen KM, Pandey RR, Homolka D, Reuter M, Janeiro BKR, et al. PIWI slicing and EXD1 drive biogenesis of nuclear piRNAs from cytosolic targets of the mouse piRNA pathway. Mol Cell. 2016;61(1):138–52.

- De Fazio S, Bartonicek N, Di Giacomo M, Abreu-Goodger C, Sankar A, Funaya C, et al. The endonuclease activity of Mili fuels piRNA amplification that silences LINE1 elements. Nature. 2011;480(7376):259–63. [CrossRef]

- Reuter M, Berninger P, Chuma S, Shah H, Hosokawa M, Funaya C, et al. Miwi catalysis is required for piRNA amplification-independent LINE1 transposon silencing. Nature. 2011;480(7376):264–7.

- Baillie JK, Barnett MW, Upton KR, Gerhardt DJ, Richmond TA, De Sapio F, et al. Somatic retrotransposition alters the genetic landscape of the human brain. Nature. 2011;479(7374):534–7.

- Blaudin de Thé F, Rekaik H, Peze-Heidsieck E, Massiani-Beaudoin O, Joshi RL, Fuchs J, et al. Engrailed homeoprotein blocks degeneration in adult dopaminergic neurons through LINE-1 repression. EMBO J. 2018;37(15):e97374. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, Samimi H, Gamez M, Zare H, Frost B. Pathogenic tau-induced piRNA depletion promotes neuronal death through transposable element dysregulation in neurodegenerative tauopathies. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(8):1038–48.

- Schulze M, Sommer A, Plötz S, Farrell M, Winner B, Grosch J, et al. Sporadic Parkinson’s disease derived neuronal cells show disease-specific mRNA and small RNA signatures with abundant deregulation of piRNAs. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:1–18.

- Zhan L, Chen M, Pang T, Li X, Long L, Liang D, et al. Attenuation of Piwil2 induced by hypoxic postconditioning prevents cerebral ischemic injury by inhibiting CREB2 promoter methylation. Brain Pathol. 2023;33(1):e13109. [CrossRef]

- Saxena A, Tang D, Carninci P. piRNAs warrant investigation in Rett Syndrome: an omics perspective. Dis Markers. 2012;33(5):261–75.

- Qiu W, Guo X, Lin X, Yang Q, Zhang W, Zhang Y, et al. Transcriptome-wide piRNA profiling in human brains of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;57:170–7. [CrossRef]

- Iossifov I, O’roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515(7526):216–21.

- Roy J, Sarkar A, Parida S, Ghosh Z, Mallick B. Small RNA sequencing revealed dysregulated piRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease and their probable role in pathogenesis. Mol Biosyst. 2017;13(3):565–76. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).