Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Fish Maintenance

2.3. RNA Extraction

2.4. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

2.5. Bioinformatic Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

2.6. cDNA Synthesis

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

2.8. Imaging and Analysis of the Tg(hb9: GFP) Embryos

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

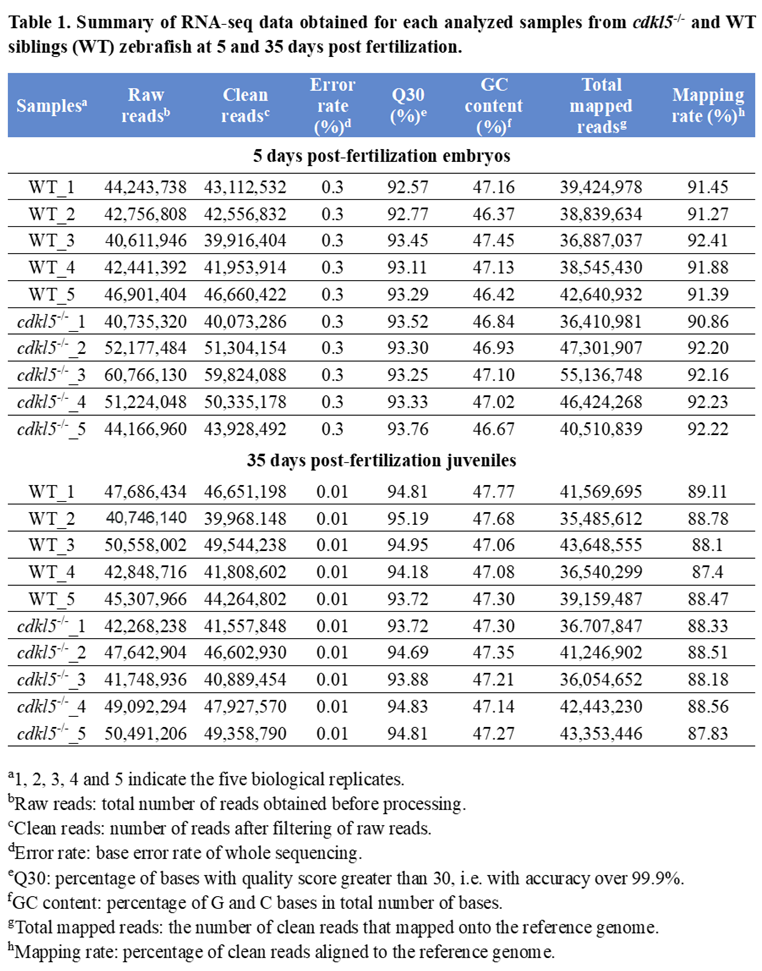

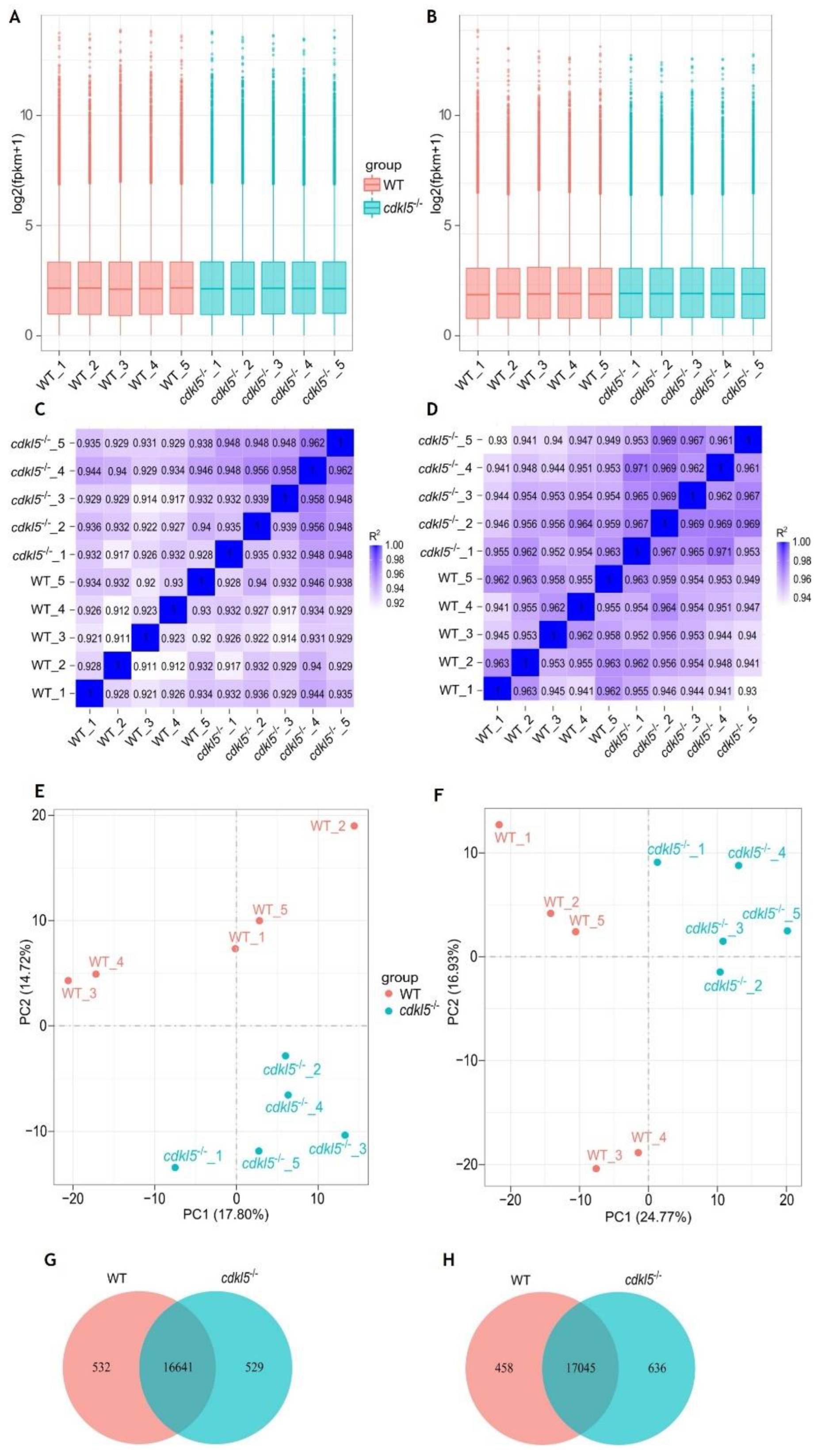

3.1. RNA-seq Data Description and Validation

3.2. Gene Expression Analysis of cdkl5-/- Mutant and WT Siblings’ Zebrafish

3.3. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes Between cdkl5-/- and WT Siblings’ Zebrafish

3.4. Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment Analysis of the Differentially Expressed Genes Between cdkl5-/- and WT Zebrafish

3.5. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of the Differentially Expressed Genes Between cdkl5-/- and WT Zebrafish

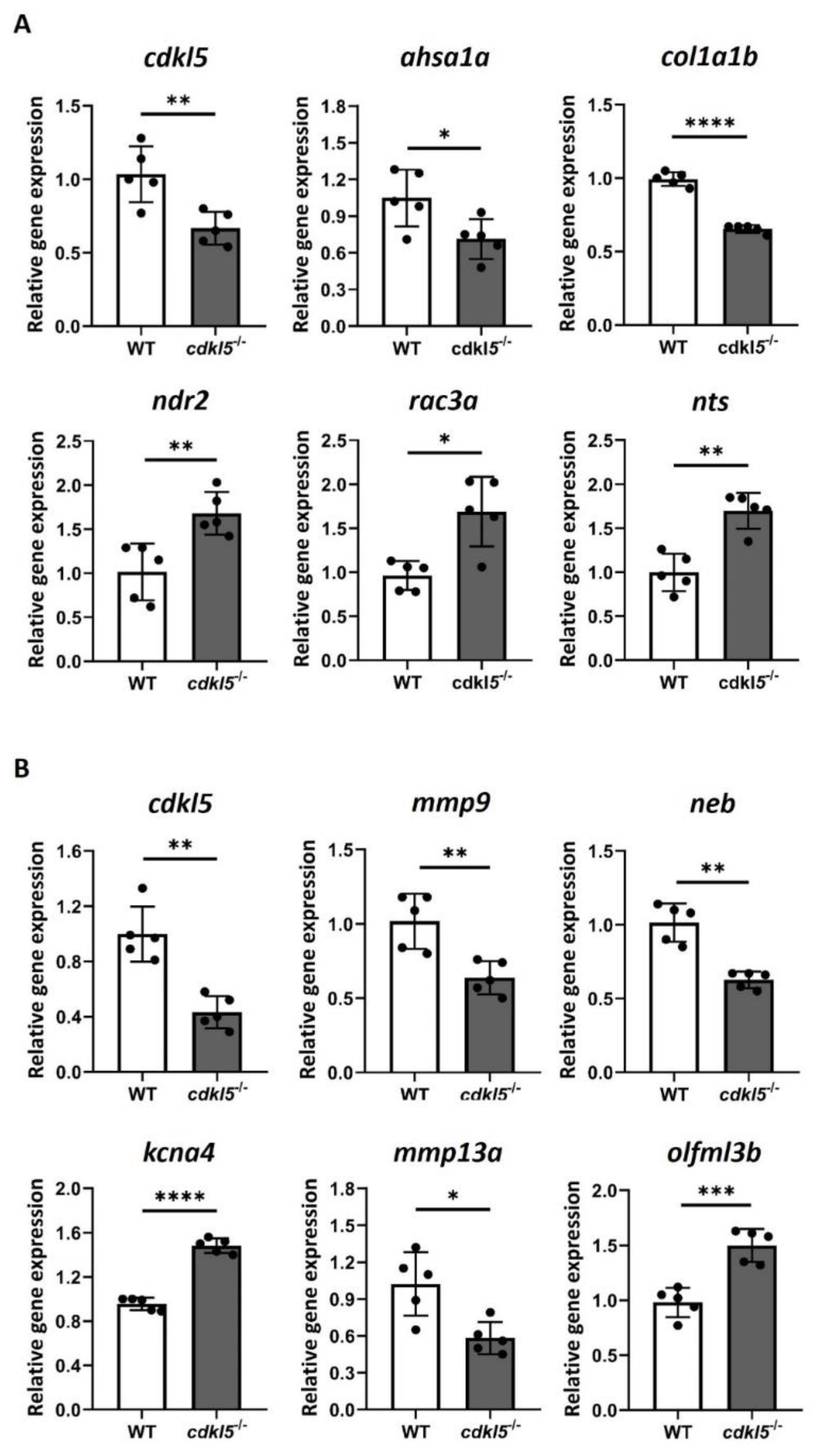

3.6. Validation of the RNA-Seq Differential Gene Expression by RT-qPCR

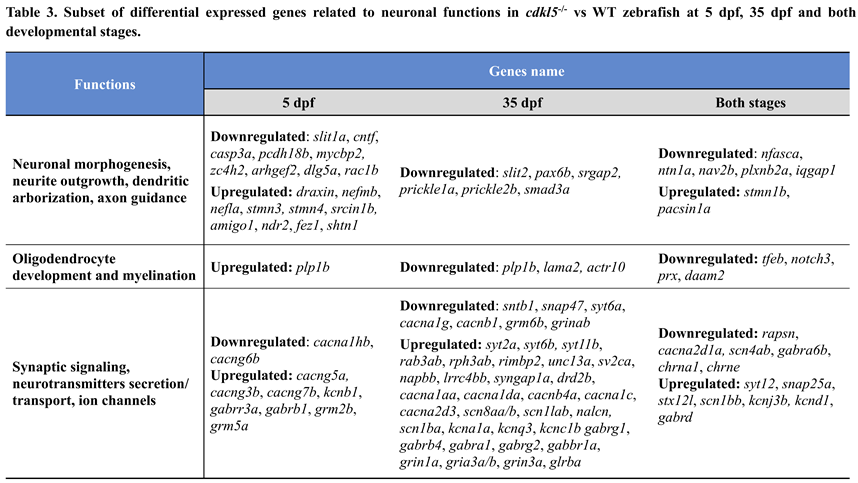

3.7. Impact of Cdkl5 Loss on Zebrafish Nervous System

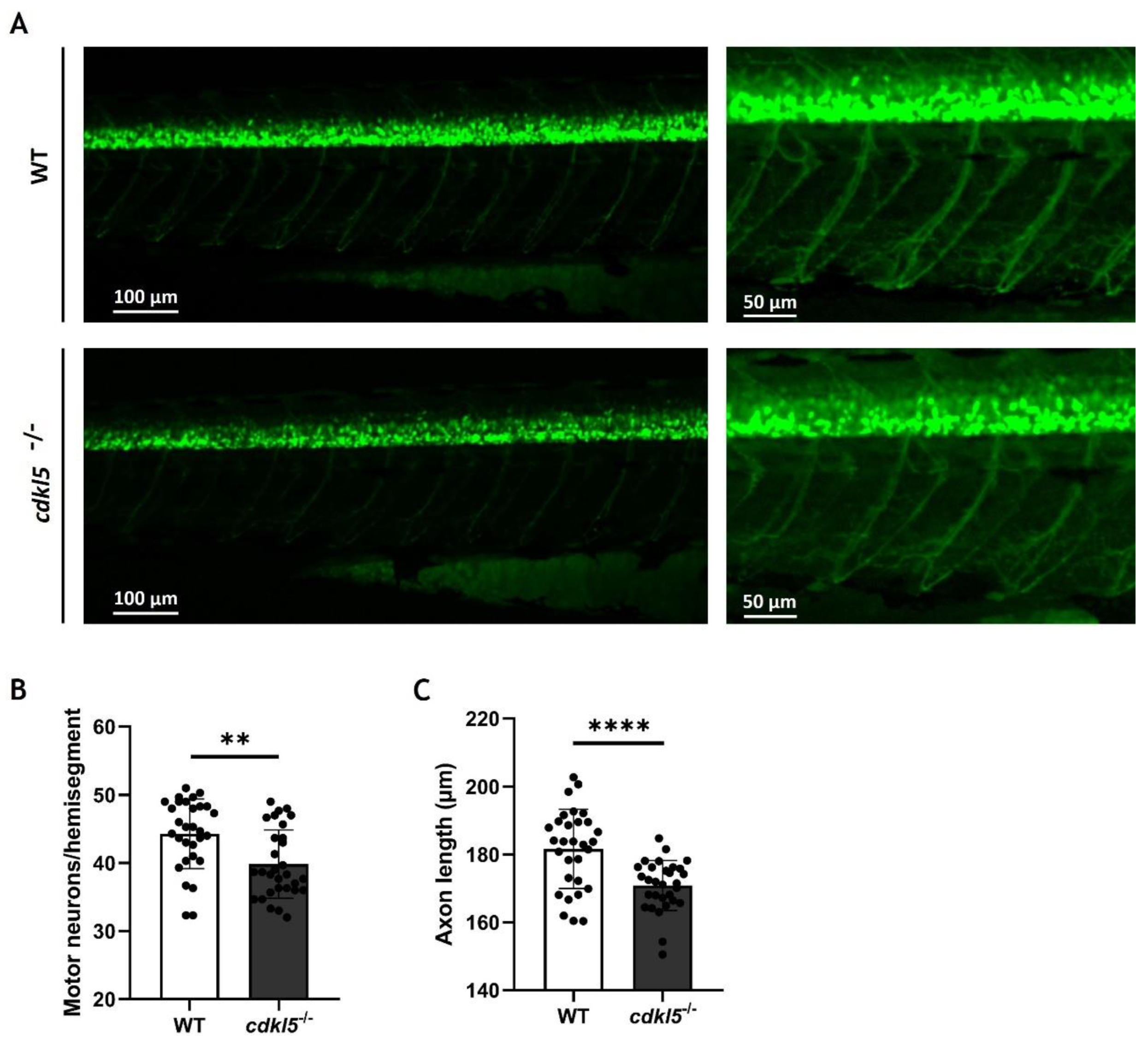

3.8. Effects of Cdkl5 Deficiency on Zebrafish Motor Neurons

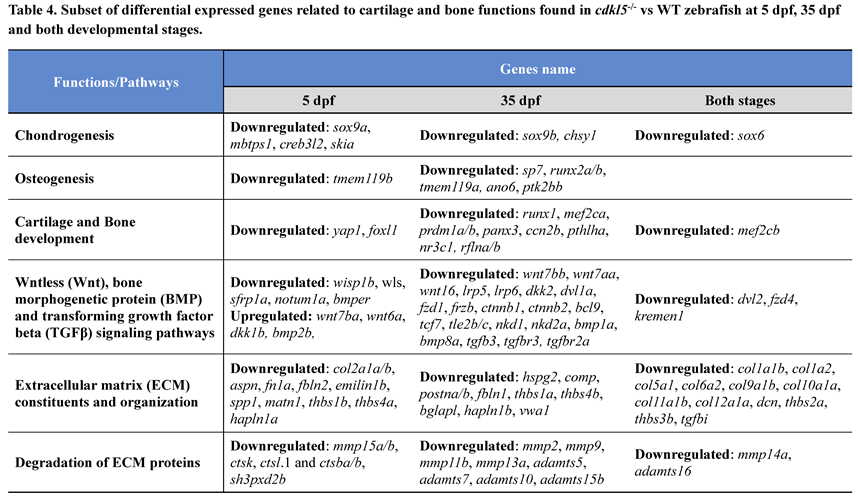

3.9. Impact of cdkl5 Loss on Zebrafish Skeletal System

4. Discussion

4.1. Deficiency of Cdkl5 in Zebrafish Causes Alterations in Genes Associated with Muscle System

4.2. Cdkl5 Deficiency in Zebrafish Leads to Dysregulation of Genes Involved in Neuronal Functions

4.3. Loss of Cdkl5 in Zebrafish Disrupts the Expression of Genes Associated with the Skeletal System

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hector, R.D.; Dando, O.; Landsberger, N.; Kilstrup-Nielsen, C.; Kind, P.C.; Bailey, M.E.S.; Cobb, S.R. Characterisation of CDKL5 Transcript Isoforms in Human and Mouse. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0157758. [CrossRef]

- Kilstrup-Nielsen, C.; Rusconi, L.; La Montanara, P.; Ciceri, D.; Bergo, A.; Bedogni, F.; Landsberger, N. What We Know and Would Like to Know about CDKL5 and Its Involvement in Epileptic Encephalopathy. Neural Plast. 2012, 2012, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, L.; Salvatoni, L.; Giudici, L.; Bertani, I.; Kilstrup-Nielsen, C.; Broccoli, V.; Landsberger, N. CDKL5 Expression Is Modulated during Neuronal Development and Its Subcellular Distribution Is Tightly Regulated by the C-terminal Tail. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 30101–30111. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhu, Y.-C.; Yu, J.; Miao, S.; Zheng, J.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Tao, J.; et al. CDKL5, a Protein Associated with Rett Syndrome, Regulates Neuronal Morphogenesis via Rac1 Signaling. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 12777–12786. [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, S.; Ungaro, F.; Hambrock, M.; Rademacher, N.; Stefanelli, G.; Brambilla, D.; Sessa, A.; Magagnotti, C.; Bachi, A.; Giarda, E.; et al. CDKL5 ensures excitatory synapse stability by reinforcing NGL-1–PSD95 interaction in the postsynaptic compartment and is impaired in patient iPSC-derived neurons. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 911–923. [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, L.; Kilstrup-Nielsen, C.; Landsberger, N. Extrasynaptic N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Stimulation Induces Cytoplasmic Translocation of the CDKL5 Kinase and Its Proteasomal Degradation. 2011, 286, 36550–36558. [CrossRef]

- Van Bergen, N. J. et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: molecular insights and mechanisms of pathogenicity to fast-track therapeutic development. Biochem Soc Trans 50, 1207–1224 (2022).

- Nawaz, M.S.; Giarda, E.; Bedogni, F.; La Montanara, P.; Ricciardi, S.; Ciceri, D.; Alberio, T.; Landsberger, N.; Rusconi, L.; Kilstrup-Nielsen, C. CDKL5 and Shootin1 Interact and Concur in Regulating Neuronal Polarization. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0148634. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhu, Y.-C.; Yu, J.; Miao, S.; Zheng, J.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Tao, J.; et al. CDKL5, a Protein Associated with Rett Syndrome, Regulates Neuronal Morphogenesis via Rac1 Signaling. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 12777–12786. [CrossRef]

- Sekiguchi, M.; Katayama, S.; Hatano, N.; Shigeri, Y.; Sueyoshi, N.; Kameshita, I. Identification of amphiphysin 1 as an endogenous substrate for CDKL5, a protein kinase associated with X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 535, 257–267. [CrossRef]

- Katayama, S.; Sueyoshi, N.; Kameshita, I. Critical Determinants of Substrate Recognition by Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-like 5 (CDKL5). Biochemistry 2015, 54, 2975–2987. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, I.M.; E Morgan, M.; Peltier, J.; Weiland, F.; Gregorczyk, M.; Brown, F.C.; Macartney, T.; Toth, R.; Trost, M.; Rouse, J. Phosphoproteomic screening identifies physiological substrates of the CDKL 5 kinase. EMBO J. 2018, 37. [CrossRef]

- Baltussen, L.L.; Negraes, P.D.; Silvestre, M.; Claxton, S.; Moeskops, M.; Christodoulou, E.; Flynn, H.R.; Snijders, A.P.; Muotri, A.R.; Ultanir, S.K. Chemical genetic identification of CDKL 5 substrates reveals its role in neuronal microtubule dynamics. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99763. [CrossRef]

- Kameshita, I.; Sekiguchi, M.; Hamasaki, D.; Sugiyama, Y.; Hatano, N.; Suetake, I.; Tajima, S.; Sueyoshi, N. Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 binds and phosphorylates DNA methyltransferase 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 1162–1167. [CrossRef]

- Mari, F.; Azimonti, S.; Bertani, I.; Bolognese, F.; Colombo, E.; Caselli, R.; Scala, E.; Longo, I.; Grosso, S.; Pescucci, C.; et al. CDKL5 belongs to the same molecular pathway of MeCP2 and it is responsible for the early-onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1935–1946. [CrossRef]

- Bahi-Buisson, N.; Nectoux, J.; Rosas-Vargas, H.; Milh, M.; Boddaert, N.; Girard, B.; Cances, C.; Ville, D.; Afenjar, A.; Rio, M.; et al. Key clinical features to identify girls with CDKL5 mutations. Brain 2008, 131, 2647–2661. [CrossRef]

- Fehr, S.; Wilson, M.; Downs, J.; Williams, S.; Murgia, A.; Sartori, S.; Vecchi, M.; Ho, G.; Polli, R.; Psoni, S.; et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 21, 266–273. [CrossRef]

- Jakimiec, M.; Paprocka, J.; Śmigiel, R. CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder—A Complex Epileptic Encephalopathy. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 107. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, H.; Downs, J.; A Benke, T.; Swanson, L.; Olson, H.; Demarest, S. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 563–576. [CrossRef]

- Olson, H.E.; Daniels, C.I.; Haviland, I.; Swanson, L.C.; Greene, C.A.; Denny, A.M.M.; Demarest, S.T.; Pestana-Knight, E.; Zhang, X.; Moosa, A.N.; et al. Current neurologic treatment and emerging therapies in CDKL5 deficiency disorder. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Amendola, E. et al. Mapping Pathological Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of CDKL5 Disorder. PLoS One 9, e91613 (2014).

- Fuchs, C.; Gennaccaro, L.; Trazzi, S.; Bastianini, S.; Bettini, S.; Martire, V.L.; Ren, E.; Medici, G.; Zoccoli, G.; Rimondini, R.; et al. Heterozygous CDKL5 Knockout Female Mice Are a Valuable Animal Model for CDKL5 Disorder. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Takao, K.; Watanabe, A.; Miyakawa, T.; Mizuguchi, M.; Tanaka, T. Comprehensive behavioral analysis of the Cdkl5 knockout mice revealed significant enhancement in anxiety- and fear-related behaviors and impairment in both acquisition and long-term retention of spatial reference memory. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0196587. [CrossRef]

- Judy, W. I.-T. et al. Loss of CDKL5 disrupts kinome profile and event-related potentials leading to autistic-like phenotypes in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 21516–21521 (2012).

- Jhang, C.-L.; Huang, T.-N.; Hsueh, Y.-P.; Liao, W. Mice lacking cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 manifest autistic and ADHD-like behaviors. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 3922–3934. [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Lee, K.-Z. CDKL5-mediated developmental tuning of neuronal excitability and concomitant regulation of transcriptome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 3276–3298. [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, M.; Cunha, N.; Conceição, N.; Cancela, M.L. Expression pattern of cdkl5 during zebrafish early development: implications for use as model for atypical Rett syndrome. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 45, 445–451. [CrossRef]

- Varela, T.; Varela, D.; Martins, G.; Conceição, N.; Cancela, M.L. Cdkl5 mutant zebrafish shows skeletal and neuronal alterations mimicking human CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- de Sena-Tomás, C. et al. Neutrophil immune profile guides spinal cord regeneration in zebrafish. Brain Behav Immun 120, 514–531 (2024).

- Flanagan-Steet, H.; Fox, M.A.; Meyer, D.; Sanes, J.R. Neuromuscular synapses can form in vivo by incorporation of initially aneural postsynaptic specializations. Development 2005, 132, 4471–4481. [CrossRef]

- Benjaminit, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Statist. Soc. B vol. 57 (1995).

- Arshadi, C.; Günther, U.; Eddison, M.; Harrington, K.I.S.; Ferreira, T.A. SNT: a unifying toolbox for quantification of neuronal anatomy. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 374–377. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, C.M.; Nielsen, M.S.; Nykjær, A.; Jacobsen, L.; Tommerup, N.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Røigaard, H.; Gliemann, J.; Madsen, P.; Moestrup, S.K. Molecular Identification of a Novel Candidate Sorting Receptor Purified from Human Brain by Receptor-associated Protein Affinity Chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3599–3605. [CrossRef]

- Mazella, J. et al. The 100-KDa Neurotensin Receptor Is Gp95/Sortilin, A Non-G-Protein-Coupled Receptor*. http://www.jbc.org (1998).

- Sakuma, H.; Murakami, A.; Fujimaki, T.; Inana, G. Isolation and characterization of the human X-arrestin gene. Gene 1998, 224, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cámara, S.; Alexandre-Moreno, S.; Bonet-Fernández, J.-M.; Atienzar-Aroca, R.; Aroca-Aguilar, J.-D.; Ferre-Fernández, J.-J.; Méndez, C.-D.; Morales, L.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Cuenca, N.; et al. Role of GUCA1C in Primary Congenital Glaucoma and in the Retina: Functional Evaluation in Zebrafish. Genes 2020, 11, 550. [CrossRef]

- Libell, J.L.; Lakhani, D.A.; Balar, A.B.; Khan, M.; Carpenter, J.S.; Joseph, J.T. Guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase deficiency: Case report and brief review of the literature. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 4331–4337. [CrossRef]

- Vizovišek, M.; Fonović, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins in extracellular matrix remodeling: Extracellular matrix degradation and beyond. Matrix Biol. 2019, 75-76, 141–159. [CrossRef]

- Kahai, S., Vary, C. P. H., Gao, Y. & Seth, A. Collagen, type V, α1 (COL5A1) is regulated by TGF-β in osteoblasts. Matrix Biology 23, 445–455 (2004).

- Peter, A.K.; Rossi, A.C.; Buvoli, M.; Ozeroff, C.D.; Crocini, C.; Perry, A.R.; Buvoli, A.E.; Lee, L.A.; Leinwand, L.A. Expression of Normally Repressed Myosin Heavy Chain 7b in the Mammalian Heart Induces Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e013318. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.S.; Shi, X.; Voelker, K.A.; Grange, R.W.; Garcia, J.A.; Hammer, R.E.; Garry, D.J. Foxj3 transcriptionally activates Mef2c and regulates adult skeletal muscle fiber type identity. Dev. Biol. 2010, 337, 396–404. [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.W.-H.; Kogoy, J.M.; Pfister, K.K. The DYNLT3 Light Chain Directly Links Cytoplasmic Dynein to a Spindle Checkpoint Protein, Bub3. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11205–11212. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Gimple, R.C.; Wu, X.; Prager, B.C.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Daggubati, V.; Mariappan, A.; Gopalakrishnan, J.; Sarkisian, M.R.; et al. Superenhancer activation of KLHDC8A drives glioma ciliation and hedgehog signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ueba, T.; Christie, B.R.; Barkho, B.; McConnell, M.J.; Nakashima, K.; Lein, E.S.; Eadie, B.D.; Willhoite, A.R.; Muotri, A.R.; et al. Mice lacking methyl-CpG binding protein 1 have deficits in adult neurogenesis and hippocampal function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 6777–6782. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.E.; Howie, S.E. The role of megalin (LRP-2/Gp330) during development. Dev. Biol. 2006, 296, 279–297. [CrossRef]

- Greiling, T.M.; Houck, S.A.; Clark, J.I. The zebrafish lens proteome during development and aging. 2009, 15, 2313–2325.

- Lima de Carvalho, J. R. et al. Effects of deficiency in the RLBP1-encoded visual cycle protein CRALBP on visual dysfunction in humans and mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 295, 6767–6780 (2020).

- Irum, B.; Khan, S.Y.; Ali, M.; Kaul, H.; Kabir, F.; Rauf, B.; Fatima, F.; Nadeem, R.; Khan, A.O.; Al Obaisi, S.; et al. Mutation in LIM2 Is Responsible for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Cataracts. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0162620. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Bakshi, A.; Anamika; Singh, V.; Paul, P.; Murugan, N.A.; Maurya, S.K. Co-localization and co-expression of Olfml3 with Iba1 in brain of mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2024, 394, 578411. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.; Kim, G.W.; Jeon, Y.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Kwon, S.H. Drawing a line between histone demethylase KDM5A and KDM5B: their roles in development and tumorigenesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 2107–2117. [CrossRef]

- Chinen, A.; Hamaoka, T.; Yamada, Y.; Kawamura, S. Gene Duplication and Spectral Diversification of Cone Visual Pigments of Zebrafish. Genetics 2003, 163, 663–675. [CrossRef]

- Lamber, E.P.; Guicheney, P.; Pinotsis, N. The role of the M-band myomesin proteins in muscle integrity and cardiac disease. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ito, T.; Kijima, Y.; Yoshitake, K.; Asakawa, S.; Watabe, S.; Kinoshita, S. Zebrafish Danio rerio myotomal muscle structure and growth from a spatial transcriptomics perspective. Genomics 2022, 114, 110477. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Maeda, T.; Mullett, S.J.; Stewart, A.F. Transcription cofactor Vgl-2 is required for skeletal muscle differentiation. Genesis 2004, 39, 273–279. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhang, F.; Ping, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. vwa1 Knockout in Zebrafish Causes Abnormal Craniofacial Chondrogenesis by Regulating FGF Pathway. Genes 2023, 14, 838. [CrossRef]

- Kriebel, M.; Wuchter, J.; Trinks, S.; Volkmer, H. Neurofascin: A switch between neuronal plasticity and stability. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 694–697. [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, S.; Salpietro, V.; Malintan, N.; Poncelet, M.; Kriouile, Y.; Fortuna, S.; De Zorzi, R.; Payne, K.; Henderson, L.B.; Cortese, A.; et al. Biallelic mutations in neurofascin cause neurodevelopmental impairment and peripheral demyelination. Brain 2019, 142, 2948–2964. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, E.C.; Jan, L.Y. Ion channel genes and human neurological disease: Recent progress, prospects, and challenges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999, 96, 4759–4766. [CrossRef]

- Weir, C. J. Ion channels, receptors, agonists and antagonists. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine 14, 410–416 (2013).

- Serrano, R.J.; Lee, C.; Douek, A.M.; Kaslin, J.; Bryson-Richardson, R.J.; Sztal, T.E. Novel preclinical model for CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Quintiliani, M.; Ricci, D.; Petrianni, M.; Leone, S.; Orazi, L.; Amore, F.; Gambardella, M.L.; Contaldo, I.; Veredice, C.; Perulli, M.; et al. Cortical Visual Impairment in CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Front. Neurol. 2022, 12, 805745. [CrossRef]

- Loi, M.; Bastianini, S.; Candini, G.; Rizzardi, N.; Medici, G.; Papa, V.; Gennaccaro, L.; Mottolese, N.; Tassinari, M.; Uguagliati, B.; et al. Cardiac Functional and Structural Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5552. [CrossRef]

- Stansauk, J.; Fidell, A.; Benke, T.; Schaffer, M.; Demarest, S.T. Analysis of electrocardiograms in individuals with CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2022, 191, 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Koleske, A.J. Mechanisms of Synapse and Dendrite Maintenance and Their Disruption in Psychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 33, 349–378. [CrossRef]

- Melom, J.E.; Littleton, J.T. Synapse development in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011, 21, 256–261. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.-J.; Sheng, Z.-H. Presynaptic perspective: Axonal transport defects in neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223. [CrossRef]

- Engle, E.C. Human Genetic Disorders of Axon Guidance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a001784–a001784. [CrossRef]

- Rathjen, F.G.; Wolff, J.; Chang, S.; Bonhoeffer, F.; Raper, J.A. Neurofascin: A novel chick cell-surface glycoprotein involved in neurite-neurite interactions. Cell 1987, 51, 841–849. [CrossRef]

- Koticha, D.; Babiarz, J.; Kane-Goldsmith, N.; Jacob, J.; Raju, K.; Grumet, M. Cell adhesion and neurite outgrowth are promoted by neurofascin NF155 and inhibited by NF186. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2005, 30, 137–148. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, H.; Nanda, I.; van Riesen, A.; McMichael, G.; Hu, H.; Hambrock, M.; Papon, M.-A.; Fischer, U.; Marouillat, S.; Ding, C.; et al. ZC4H2 Mutations Are Associated with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita and Intellectual Disability through Impairment of Central and Peripheral Synaptic Plasticity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 92, 681–695. [CrossRef]

- Guerrier, S.; Coutinho-Budd, J.; Sassa, T.; Gresset, A.; Jordan, N.V.; Chen, K.; Jin, W.-L.; Frost, A.; Polleux, F. The F-BAR Domain of srGAP2 Induces Membrane Protrusions Required for Neuronal Migration and Morphogenesis. Cell 2009, 138, 990–1004. [CrossRef]

- Okuda, H.; Miyata, S.; Mori, Y.; Tohyama, M. Mouse Prickle1 and Prickle2 are expressed in postmitotic neurons and promote neurite outgrowth. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4754–4760. [CrossRef]

- Kvarnung, M.; Shahsavani, M.; Taylan, F.; Moslem, M.; Breeuwsma, N.; Laan, L.; Schuster, J.; Jin, Z.; Nilsson, D.; Lieden, A.; et al. Ataxia in Patients With Bi-Allelic NFASC Mutations and Absence of Full-Length NF186. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 896. [CrossRef]

- Smigiel, R.; Sherman, D.L.; Rydzanicz, M.; Walczak, A.; Mikolajkow, D.; Krolak-Olejnik, B.; Kosińska, J.; Gasperowicz, P.; Biernacka, A.; Stawinski, P.; et al. Homozygous mutation in the Neurofascin gene affecting the glial isoform of Neurofascin causes severe neurodevelopment disorder with hypotonia, amimia and areflexia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 3669–3674. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lim, B.C.; Kim, K.J.; Chae, J.-H. Variable Phenotypes of ZC4H2-Associated Rare Disease in Six Patients. Ann. Child Neurol. 2022, 30, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Bassuk, A.G.; Wallace, R.H.; Buhr, A.; Buller, A.R.; Afawi, Z.; Shimojo, M.; Miyata, S.; Chen, S.; Gonzalez-Alegre, P.; Griesbach, H.L.; et al. A Homozygous Mutation in Human PRICKLE1 Causes an Autosomal-Recessive Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy-Ataxia Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 572–581. [CrossRef]

- Bayat, A.; Iqbal, S.; Borredy, K.; Amiel, J.; Zweier, C.; Barcia, G.; Kraus, C.; Weyhreter, H.; Bassuk, A.G.; Chopra, M.; et al. PRICKLE2 revisited—further evidence implicating PRICKLE2 in neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 1235–1244. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Medici, G.; Trazzi, S.; Gennaccaro, L.; Galvani, G.; Berteotti, C.; Ren, E.; Loi, M.; Ciani, E. CDKL5 deficiency predisposes neurons to cell death through the deregulation of SMAD3 signaling. Brain Pathol. 2019, 29, 658–674. [CrossRef]

- Masson, M.; Nait-Oumesmar, B. Emerging concepts in oligodendrocyte and myelin formation, inputs from the zebrafish model. Glia 2023, 71, 1147–1163. [CrossRef]

- Elitt, M.S.; Barbar, L.; Shick, H.E.; Powers, B.E.; Maeno-Hikichi, Y.; Madhavan, M.; Allan, K.C.; Nawash, B.S.; Gevorgyan, A.S.; Hung, S.; et al. Suppression of proteolipid protein rescues Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease. Nature 2020, 585, 397–403. [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Contreras, A.Y.; Zarate-Lopez, D.; Torres-Chavez, A.L.; Gonzalez-Perez, O. Role of Oligodendrocytes and Myelin in the Pathophysiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 951. [CrossRef]

- Khelfaoui, H.; Ibaceta-Gonzalez, C.; Angulo, M.C. Functional myelin in cognition and neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ashery, U. et al. Chapter Two - The molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic transmission: A view of the presynaptic terminal. in The Synapse (eds. Pickel, V. & Segal, M.) 21–109 (Academic Press, Boston, 2014). [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C. THE SYNAPTIC VESICLE CYCLE. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 27, 509–547. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V. N. & De Camilli, P. Cell biology of the presynaptic terminal. Annu Rev Neurosci 26, 701–728 (2003).

- Casillas-Espinosa, P.M.; Powell, K.L.; O’brien, T.J. Regulators of synaptic transmission: Roles in the pathogenesis and treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 41–58. [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, R.; Gurgone, A.; Castroflorio, E.; Amendola, E.; Gross, C.; Sassoè-Pognetto, M.; Giustetto, M. Lack of Cdkl5 Disrupts the Organization of Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapses and Parvalbumin Interneurons in the Primary Visual Cortex. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 261. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Lou, S.; Yang, G.; Feng, X.; Xu, W.; Huang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Xiong, Z. CDKL5 deficiency in forebrain glutamatergic neurons results in recurrent spontaneous seizures. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 517–528. [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Wang, Q.; Tang, B.; Wu, Z.; Yang, T.; Tang, J. CDKL5 Deficiency Augments Inhibitory Input into the Dentate Gyrus That Can Be Reversed by Deep Brain Stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 9031–9046. [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Fukaya, M.; Watanabe, A.; Murakami, T.; Hagiwara, M.; Sato, T.; Ueno, H.; Ogonuki, N.; Komano-Inoue, S.; et al. CDKL5 controls postsynaptic localization of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors in the hippocampus and regulates seizure susceptibility. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 106, 158–170. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Terzic, B.; Wang, I.-T.J.; Sarmiento, N.; Sizov, K.; Cui, Y.; Takano, H.; Marsh, E.D.; Zhou, Z.; Coulter, D.A. Altered NMDAR signaling underlies autistic-like features in mouse models of CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2655. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, I.-T.J.; Yue, C.; Takano, H.; Terzic, B.; Pance, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Cui, Y.; Coulter, D.A.; Zhou, Z. Loss of CDKL5 in Glutamatergic Neurons Disrupts Hippocampal Microcircuitry and Leads to Memory Impairment in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 7420–7437. [CrossRef]

- Crèvecœur, J.; Kaminski, R.M.; Rogister, B.; Foerch, P.; Vandenplas, C.; Neveux, M.; Mazzuferi, M.; Kroonen, J.; Poulet, C.; Martin, D.; et al. Expression pattern of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2014, 40, 191–204. [CrossRef]

- Pavinato, L.; Stanic, J.; Barzasi, M.; Gurgone, A.; Chiantia, G.; Cipriani, V.; Eberini, I.; Palazzolo, L.; Di Luca, M.; Costa, A.; et al. Missense variants in RPH3A cause defects in excitatory synaptic function and are associated with a clinically variable neurodevelopmental disorder. Anesthesia Analg. 2023, 25, 100922. [CrossRef]

- Lipstein, N.; Verhoeven-Duif, N.M.; Michelassi, F.E.; Calloway, N.; van Hasselt, P.M.; Pienkowska, K.; van Haaften, G.; van Haelst, M.M.; van Empelen, R.; Cuppen, I.; et al. Synaptic UNC13A protein variant causes increased neurotransmission and dyskinetic movement disorder. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1005–1018. [CrossRef]

- Kontaxi, C.; Ivanova, D.; Davenport, E.C.; Kind, P.C.; Cousin, M.A. Epilepsy-Related CDKL5 Deficiency Slows Synaptic Vesicle Endocytosis in Central Nerve Terminals. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 2002–2020. [CrossRef]

- D'Adamo, M.C.; Liantonio, A.; Conte, E.; Pessia, M.; Imbrici, P. Ion Channels Involvement in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuroscience 2020, 440, 337–359. [CrossRef]

- Hü Bner, C. A. & Jentsch, T. J. Ion channel diseases.

- Rodan, L.H.; Spillmann, R.C.; Kurata, H.T.; Lamothe, S.M.; Maghera, J.; Jamra, R.A.; Alkelai, A.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Atallah, I.; Bar-Yosef, O.; et al. Phenotypic expansion of CACNA1C-associated disorders to include isolated neurological manifestations. Anesthesia Analg. 2021, 23, 1922–1932. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. et al. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function de novo CACNA1A mutations cause severe developmental epileptic encephalopathies in the spectrum of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia 60, 1881–1894 (2019).

- Pinggera, A.; Lieb, A.; Benedetti, B.; Lampert, M.; Monteleone, S.; Liedl, K.R.; Tuluc, P.; Striessnig, J. CACNA1D De Novo Mutations in Autism Spectrum Disorders Activate Cav1.3 L-Type Calcium Channels. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 816–822. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro-Castañeda, M.; Baltussen, L.L.; Lopes, A.T.; Qiu, Y.; Sirvio, L.; Mihaylov, S.R.; Claxton, S.; Richardson, J.C.; Lignani, G.; Ultanir, S.K. Epilepsy-linked kinase CDKL5 phosphorylates voltage-gated calcium channel Cav2.3, altering inactivation kinetics and neuronal excitability. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ziobro, J.; Robinson-Cooper, L.; Hodges, S.L.; Chen, Y.; Edokobi, N.; Lopez-Santiago, L.; Habig, K.; Moore, C.; Minton, J.; et al. Epilepsy and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy in a mouse model of human SCN1B-linked developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Brain Commun. 2023, 5, fcad283. [CrossRef]

- Gardella, E. & Møller, R. S. Phenotypic and genetic spectrum of SCN8A-related disorders, treatment options, and outcomes. Epilepsia 60, S77–S85 (2019).

- Wagnon, J.L.; Barker, B.S.; Hounshell, J.A.; Haaxma, C.A.; Shealy, A.; Moss, T.; Parikh, S.; Messer, R.D.; Patel, M.K.; Meisler, M.H. Pathogenic mechanism of recurrent mutations of SCN8A in epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2015, 3, 114–123. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bolt, E.; Newmaster, K.; Osei-Bonsu, W.; Cohen, S.; Cuddapah, V.A.; Gupta, S.; Paudel, S.; Samanta, D.; Dang, L.T.; et al. SCN1B Genetic Variants: A Review of the Spectrum of Clinical Phenotypes and a Report of Early Myoclonic Encephalopathy. Children 2022, 9, 1507. [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.C.; O'Malley, H.A.; Hull, J.M.; Kleeman, A.; Patino, G.A.; Isom, L.L. β1-C121W Is Down But Not Out: Epilepsy-AssociatedScn1b-C121WResults in a Deleterious Gain-of-Function. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 6213–6224. [CrossRef]

- Aledo-Serrano, Á.; Gómez-Iglesias, P.; Toledano, R.; Garcia-Peñas, J.J.; Garcia-Morales, I.; Anciones, C.; Soto-Insuga, V.; Benke, T.A.; del Pino, I.; Gil-Nagel, A. Sodium channel blockers for the treatment of epilepsy in CDKL5 deficiency disorder: Findings from a multicenter cohort. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 118, 107946. [CrossRef]

- Kalm, T.; Schob, C.; Völler, H.; Gardeitchik, T.; Gilissen, C.; Pfundt, R.; Klöckner, C.; Platzer, K.; Klabunde-Cherwon, A.; Ries, M.; et al. Etiological involvement of KCND1 variants in an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder with variable expressivity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 1206–1221. [CrossRef]

- Miceli, F. et al. Early-onset epileptic encephalopathy caused by gain-of-function mutations in the voltage sensor of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 potassium channel subunits. Journal of Neuroscience 35, 3782–3793 (2015).

- Ambrosino, P. et al. A novel KCNC1 gain-of-function variant causing developmental and epileptic encephalopathy: “Precision medicine” approach with fluoxetine. Epilepsia 64, e148–e155 (2023).

- Miceli, F. et al. Distinct epilepsy phenotypes and response to drugs in KCNA1 gain- and loss-of function variants. Epilepsia 63, e7–e14 (2022).

- Veale, E.L.; Golluscio, A.; Grand, K.; Graham, J.M.; Mathie, A. A KCNB1 gain of function variant causes developmental delay and speech apraxia but not seizures. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1093313. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, F. Potassium channel-related epilepsy: Pathogenesis and clinical features. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 891–905. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yao, H.; Negraes, P.D.; Wang, J.; Trujillo, C.A.; de Souza, J.S.; Muotri, A.R.; Haddad, G.G. Neuronal hyperexcitability and ion channel dysfunction in CDKL5-deficiency patient iPSC-derived cortical organoids. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 174. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.B.; Valakh, V. Excitatory/Inhibitory Balance and Circuit Homeostasis in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Neuron 2015, 87, 684–698. [CrossRef]

- Kan, A. S. H. et al. Understanding paralogous epilepsy-associated GABAA receptor variants: Clinical implications, mechanisms, and potential pitfalls. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121, e2413011121 (2024).

- Sun, J.-H.; Chen, J.; Valenzuela, F.E.A.; Brown, C.; Masser-Frye, D.; Jones, M.; Romero, L.P.; Rinaldi, B.; Li, W.L.; Li, Q.-Q.; et al. X-linked neonatal-onset epileptic encephalopathy associated with a gain-of-function variant p.R660T in GRIA3. PLOS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009608. [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson, L.; Zhang, Z.; Das, S.S.; Tran, P.; Andersson, Å.; Portes, V.D.; Altuzarra, C.D.; Remerand, G.; Labalme, A.; Chatron, N.; et al. GRIN1 variants associated with neurodevelopmental disorders reveal channel gating pathomechanisms. Epilepsia 2023, 64, 3377–3388. [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, B.; Bayat, A.; Zachariassen, L.G.; Sun, J.-H.; Ge, Y.-H.; Zhao, D.; Bonde, K.; Madsen, L.H.; Awad, I.A.A.; Bagiran, D.; et al. Gain-of-function and loss-of-function variants in GRIA3 lead to distinct neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Brain 2023, 147, 1837–1855. [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, K.; Miyoshi, K.; Sun, J.-H.; Hamada, K.; Komatsubara, T.; Saida, K.; Tsuchida, N.; Uchiyama, Y.; Fujita, A.; Mizuguchi, T.; et al. Amelioration of a neurodevelopmental disorder by carbamazepine in a case having a gain-of-function GRIA3 variant. Hum. Genet. 2022, 141, 283–293. [CrossRef]

- Ahring, P.K.; Liao, V.W.Y.; Gardella, E.; Johannesen, K.M.; Krey, I.; Selmer, K.K.; Stadheim, B.F.; Davis, H.; Peinhardt, C.; Koko, M.; et al. Gain-of-function variants in GABRD reveal a novel pathway for neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy. Brain 2021, 145, 1299–1309. [CrossRef]

- Musto, E. et al. GABRA1-related disorders: From genetic to functional pathways. Ann Neurol 95, 27–41 (2024).

- Yennawar, M.; White, R.S.; Jensen, F.E. AMPA Receptor Dysregulation and Therapeutic Interventions in a Mouse Model of CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 4814–4828. [CrossRef]

- Gennaccaro, L.; Fuchs, C.; Loi, M.; Roncacè, V.; Trazzi, S.; Ait-Bali, Y.; Galvani, G.; Berardi, A.C.; Medici, G.; Tassinari, M.; et al. A GABAB receptor antagonist rescues functional and structural impairments in the perirhinal cortex of a mouse model of CDKL5 deficiency disorder. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 153, 105304. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.; Smits, P. Transcriptional control of chondrocyte fate and differentiation. Birth Defects Res. Part C: Embryo Today: Rev. 2005, 75, 200–212. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V. & Bhattaram, P. Vertebrate skeletogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol 90, 291–317 (2010).

- Hernández-García, F.; Fernández-Iglesias, Á.; Suárez, J.R.; Gil Peña, H.; López, J.M.; Pérez, R.F. The Crosstalk Between Cartilage and Bone in Skeletal Growth. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2662. [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, F.; Bek, J.W.; Besio, R.; De Clercq, A.; Leoni, L.; Salmon, P.; Coucke, P.J.; Willaert, A.; Forlino, A. Zebrafish: A Resourceful Vertebrate Model to Investigate Skeletal Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 489. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.; Huang, W.; Harley, V.R.; Goodfellow, P.N.; de Crombrugghe, B. SOX9 Is a Potent Activator of the Chondrocyte-Specific Enhancer of the Proα1(II) Collagen Gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 2336–2346. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Tanaka, K.; Tsumaki, N.; Yamada, Y. Identification of an Enhancer Sequence within the First Intron Required for Cartilage-specific Transcription of the α2(XI) Collagen Gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 12712–12718. [CrossRef]

- Genzer, M.A.; Bridgewater, L.C. A Col9a1 enhancer element activated by two interdependent SOX9 dimers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 1178–1186. [CrossRef]

- Lamandé, S.R.; Bateman, J.F. Genetic Disorders of the Extracellular Matrix. Anat. Rec. 2019, 303, 1527–1542. [CrossRef]

- Saltarelli, M.A.; Quarta, A.; Chiarelli, F. Growth plate extracellular matrix defects and short stature in children. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 27, 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wu, R.W.; Lam, Y.; Chan, W.C.; Chan, D. Hypertrophic chondrocytes at the junction of musculoskeletal structures. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101698. [CrossRef]

- Ortega, N.; Behonick, D.J.; Werb, Z. Matrix remodeling during endochondral ossification. Trends Cell Biol. 2004, 14, 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Mackie, E.J.; Ahmed, Y.A.; Tatarczuch, L.; Chen, K.-S.; Mirams, M. Endochondral ossification: How cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 46–62. [CrossRef]

- Komori, T. Regulation of bone development and extracellular matrix protein genes by RUNX2. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Kneissel, M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 179–192. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Koide, M.; Uehara, S.; Okamoto, M.; Ishihara, A.; Kayama, T.; Saito, M.; Marumo, K. The Regulation of Bone Metabolism and Disorders by Wnt Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5525. [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, Y.; Mortier, G.; Boudin, E.; Van Hul, W. WNT Signaling and Bone: Lessons From Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 165. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.-P.; Paulson, C.; Shao, J.-Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Chen, W. Wnt and the Wnt signaling pathway in bone development and disease. Front. Biosci. 2014, 19, 379–407. [CrossRef]

| Gene symbol | Protein name | Log2(fold change) | p-value | padj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 days post-fertilization embryos | ||||

| sort1a | Sortilin 1a | 1.8794 | 2.9996e-13 | 1.1657e-09 |

| tdo2b | Tryptophan 2,3-Dioxygenase 2b | 0.8033 | 9.0703e-11 | 1.9583e-07 |

| cflara | CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator a | 0.7984 | 1.3040e-10 | 2.5339e-07 |

| ube2l3a | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L 3a | 2.2685 | 4.5907e-10 | 6.8616e-07 |

| pdap1a | pdgfa associated protein 1a | 0.8095 | 1.3519e-08 | 1.3135e-05 |

| csrp2 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 2 | 0.7129 | 1.4895e-08 | 1.3782e-05 |

| igfbp1b | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1b | 0.9922 | 2.3254e-08 | 2.0442e-05 |

| guca1c | Guanylate cyclase activator 1C | 0.9678 | 2.9697e-08 | 2.4044e-05 |

| nts | Neurotensin | 4.3662 | 1.9960e-07 | 0.0001 |

| tmem240b | Transmembrane protein 240b | 1.1948 | 2.8351e-07 | 0.0002 |

| ndufs7 | NADH Dehydrogenase [Ubiquinone] Iron-Sulfur Protein 7 | 1.0968 | 3.1092e-07 | 0.0002 |

| c7b | Complement component 7b | 1.7532 | 3.7864e-07 | 0.0002 |

| mt2 | Metallothionein 2 | 1.2515 | 9.1100e-07 | 0.0005 |

| phf13 | PHD finger protein 13 | 0.5807 | 2.5537e-06 | 0.0012 |

| krt15 | Keratin 15 | 0.9521 | 2.9615e-06 | 0.0013 |

| cspg4bb | chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4bb | 1.7450 | 4.0039e-06 | 0.0017 |

| ccdc149a | coiled-coil domain containing 149a | 2.0997 | 5.2690e-06 | 0.0021 |

| arr3b | Arrestin 3b | 0.7502 | 5.3098e-06 | 0.0021 |

| tcnba | Transcobalamin beta a | 0.7376 | 7.0446e-06 | 0.0024 |

| cel.2 | Carboxyl ester lipase, tandem duplicate 2 | 0.5815 | 8.2700e-06 | 0.0028 |

| gamt | Guanidinoacetate N-methyltransferase | -3.1079 | 1.1615e-92 | 2.2569e-88 |

| nucks1a | Nuclear casein kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate 1a | -1.3425 | 5.4136e-19 | 5.2596e-15 |

| pir | Pirin | -1.3499 | 3.3308e-17 | 2.1574e-13 |

| ctsl.1 | Cathepsin L.1 | -1.2024 | 2.3532e-13 | 1.1431e-09 |

| card19 | Caspase recruitment domain family member 19 | -1.5736 | 8.6568e-12 | 2.8035e-08 |

| ugt1b5 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide B5 | -1.8045 | 2.4384e-11 | 6.7686e-08 |

| dynlt3 | Dynein Light Chain Tctex-Type 3 | -0.8301 | 1.6882e-10 | 2.9821e-07 |

| klhdc8a | Kelch domain containing 8A | -6.1579 | 2.4233e-10 | 3.9239e-07 |

| ccdc120 | Coiled-coil domain containing 120 | -1.9919 | 6.3624e-10 | 8.8305e-07 |

| foxj3 | Forkhead box J3 | -0.7362 | 9.5553e-10 | 1.2378e-06 |

| slc15a2 | Solute carrier family 15, member 2 | -0.8038 | 8.1421e-09 | 8.3268e-06 |

| slc12a10.1 | Solute carrier family 12, member 10, tandem duplicate 1 | -1.8439 | 2.4197e-08 | 2.0442e-05 |

| cishb | Cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein b | -1.8439 | 7.1115e-08 | 5.4873e-05 |

| mbd1b | Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1b | -1.1586 | 7.3423e-08 | 5.4873e-05 |

| slc41a1 | Solute carrier family 41, member 1 | -4.4974 | 2.1192e-07 | 0.0001 |

| rs1a | Retinoschisin 1a | -0.5785 | 2.2400e-07 | 0.0001 |

| etnk2 | Ethanolamine kinase 2 | -5.2767 | 3.2897e-07 | 0.0002 |

| lrp2b | Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2b | -1.2138 | 5.5833e-07 | 0.0003 |

| gnl3l | G protein nucleolar 3 like | -2.7313 | 8.3341e-07 | 0.0004 |

| myh7ba | Myosin heavy chain 7B | -0.8244 | 1.2271e-06 | 0.0006 |

| col5a1 | Collagen type V alpha 1 chain | -0.4288 | 1.2532e-06 | 0.0006 |

| 35 days post-fertilization juveniles | ||||

| olfml3b | Olfactomedin-like 3b | 5.2512 | 1.5620e-78 | 1.6759e-74 |

| kdm5ba | Lysine Demethylase 5Ba | 1.5014 | 3.4759e-16 | 6.2161e-13 |

| crygm2d18 | crystallin, gamma M2d18 | 2.4337 | 7.8911e-15 | 1.2096e-11 |

| ipo9 | Importin 9 | 2.0313 | 8.7711e-15 | 1.2549e-11 |

| rlbp1b | Retinaldehyde binding protein 1b | 1.9842 | 2.3868e-14 | 3.2013e-11 |

| ggctb | Gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase b | 1.0173 | 3.8752e-12 | 4.3769e-09 |

| lim2.4 | Lens intrinsic membrane protein 2.4 | 1.2252 | 1.4216e-11 | 1.4528e-08 |

| tfcp2l1 | Transcription factor CP2-like 1 | 1.1479 | 4.2758e-11 | 3.6703e-08 |

| krt15 | Keratin 15 | 1.5442 | 1.1659e-10 | 9.0605e-08 |

| crygm2d15 | Crystallin gamma M2d15 | 2.2803 | 1.2171e-10 | 9.0605e-08 |

| crygm2d16 | Crystallin gamma M2d16 | 2.3116 | 1.2224e-10 | 9.0605e-08 |

| crygm2d11 | Crystallin gamma M2d11 | 1.5472 | 1.2244e-10 | 9.0605e-08 |

| rrp9 | Ribosomal RNA processing 9 | 1.6369 | 1.4287e-10 | 9.8906e-08 |

| cryba2a | Crystallin beta a2a | 1.1551 | 2.3574e-10 | 1.5809e-07 |

| crygm2d13 | Crystallin gamma M2d13 | 1.6363 | 4.4261e-10 | 2.7139e-07 |

| parapinopsinb | Parapinopsin b | 2.9711 | 6.3436e-10 | 3.5825e-07 |

| foxq1a | Forkhead box Q1a | 0.6750 | 7.2768e-10 | 3.9040e-07 |

| dynlrb1 | Dynein light chain roadblock-type 1 | 0.8483 | 8.6657e-10 | 4.5358e-07 |

| timm17a | Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 17A | 1.4058 | 2.2971e-09 | 1.0060e-06 |

| crygm2d14 | Crystallin, gamma M2d14 | 1.8210 | 2.5513e-09 | 1.0950e-06 |

| opn1lw2 | Opsin 1, long-wave-sensitive, 2 | -4.8460 | 4.6970e-108 | 1.0080e-103 |

| opn1lw1 | Opsin 1, long-wave-sensitive, 1 | -4.5892 | 3.4828e-70 | 2.4914e-66 |

| gnl3l | G protein nucleolar 3 like | -3.1493 | 4.3148e-58 | 2.3149e-54 |

| nucks1a | Nuclear casein kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate 1a | -1.4428 | 4.5028e-30 | 1.7153e-26 |

| pir | Pirin | -1.9600 | 9.5388e-29 | 2.9243e-25 |

| slc41a1 | Solute carrier family 41, member 1 | -4.2114 | 2.8678e-26 | 7.6930e-23 |

| ccdc120 | Coiled-coil domain containing 120 | -2.7935 | 6.8052e-23 | 1.6227e-19 |

| ugt1b5 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide B5 | -1.4197 | 1.1478e-18 | 2.4631e-15 |

| dynlt3 | Dynein Light Chain Tctex-Type 3 | -0.8398 | 1.6501e-17 | 3.2191e-14 |

| nfasca | Neurofascin a | -1.0500 | 1.0572e-12 | 1.3345e-09 |

| mbd1b | Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 1b | -1.6633 | 3.8504e-12 | 4.3769e-09 |

| myh7ba | Myosin heavy chain 7B | -0.8647 | 3.0928e-11 | 2.8019e-08 |

| ehd2b | EH-domain containing 2b | -0.4425 | 1.2915e-10 | 9.2386e-08 |

| igfn1.1 | immunoglobulin like and fibronectin type III domain containing 1, tandem duplicate 1 | -1.1561 | 4.2629e-10 | 2.7139e-07 |

| cishb | Cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein b | -1.6556 | 4.3495e-10 | 2.7139e-07 |

| htra1b | HtrA serine peptidase 1b | -0.6314 | 4.9847e-10 | 2.8959e-07 |

| myhc4 | Myosin heavy chain 4 | -1.5783 | 6.6454e-10 | 3.6570e-07 |

| vgll2b | Vestigial-like family member 2b | -1.2804 | 1.3015e-09 | 6.3616e-07 |

| myom2a | Myomesin 2a | -1.1321 | 1.3043e-09 | 6.3616e-07 |

| vwa1 | von Willebrand factor A domain containing 1 | -0.5727 | 1.4088e-09 | 6.7183e-07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).