Submitted:

31 August 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

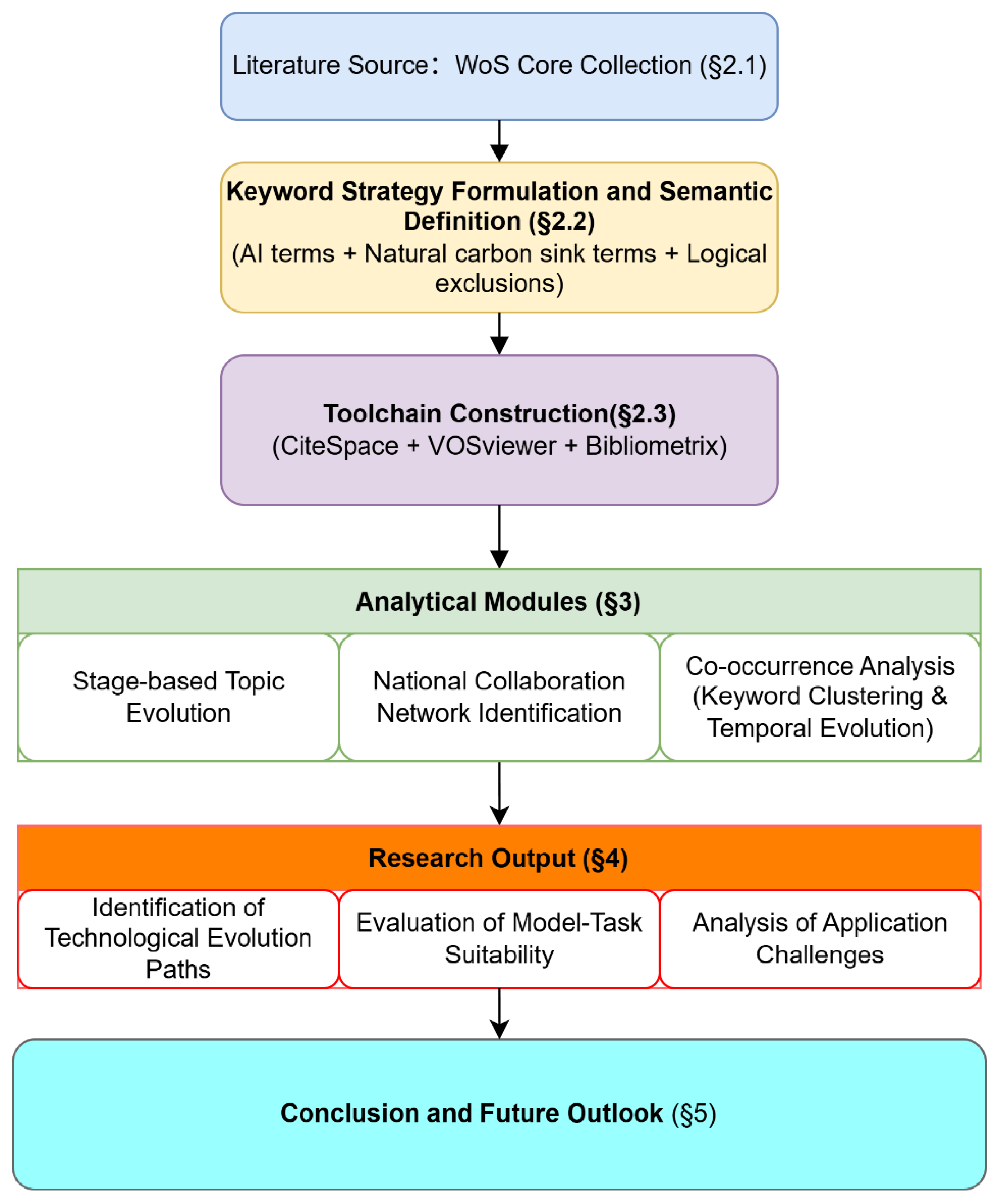

2. Research Methodology and Data Collection

2.1. Data Collection and Search Strategy

2.2. Data Analysis Tools and Methodological Framework

3. Results and Analysis

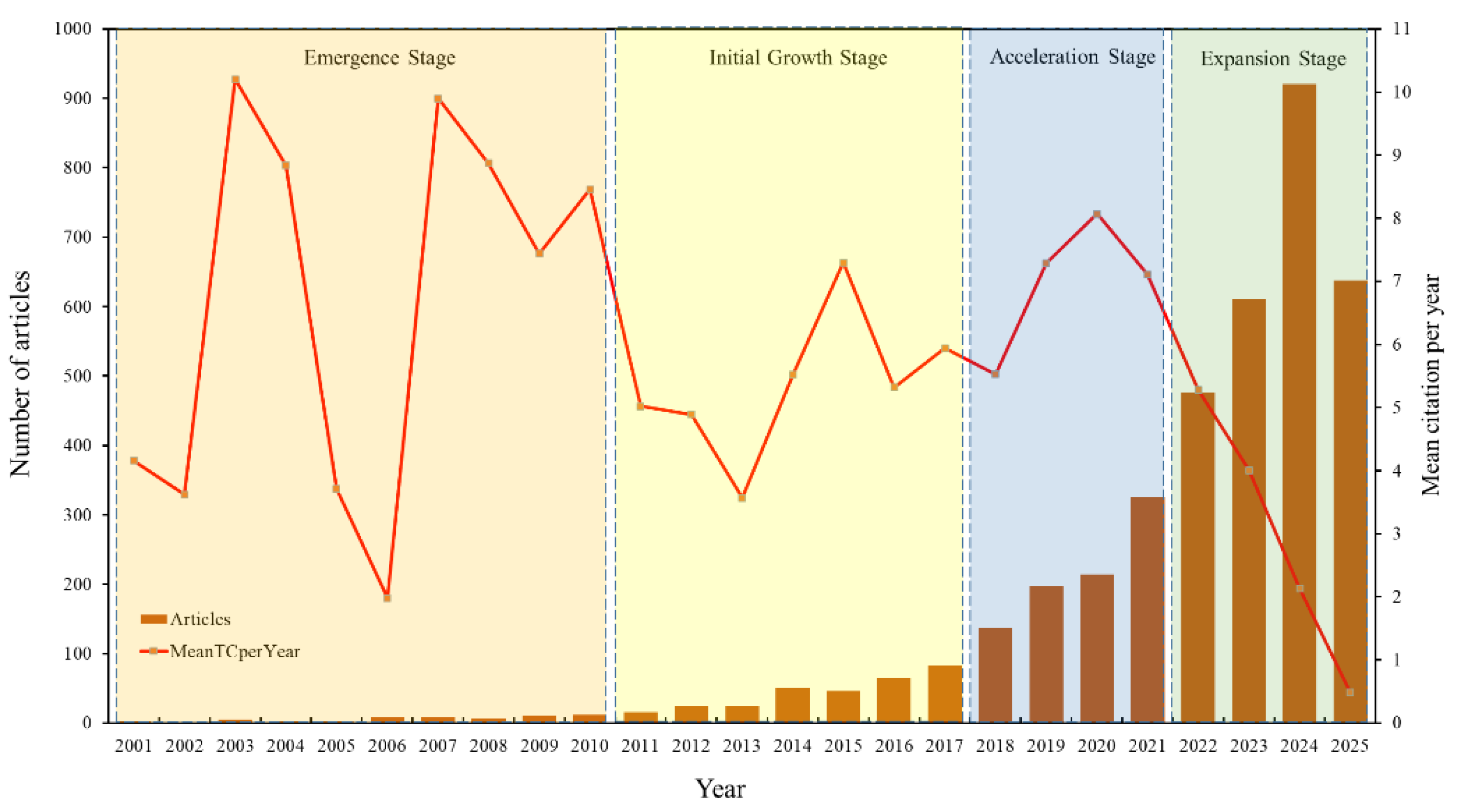

3.1. Phase Division

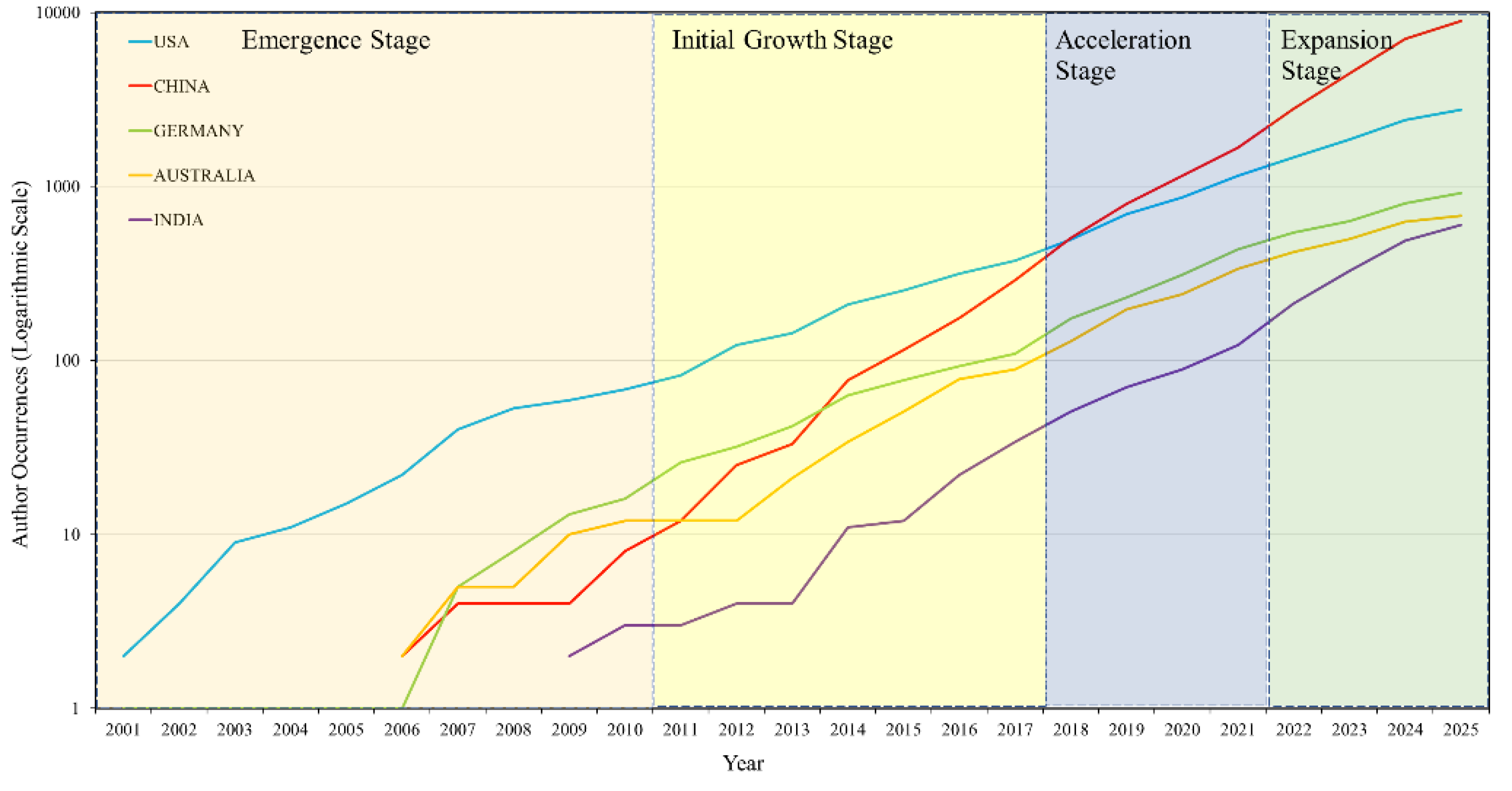

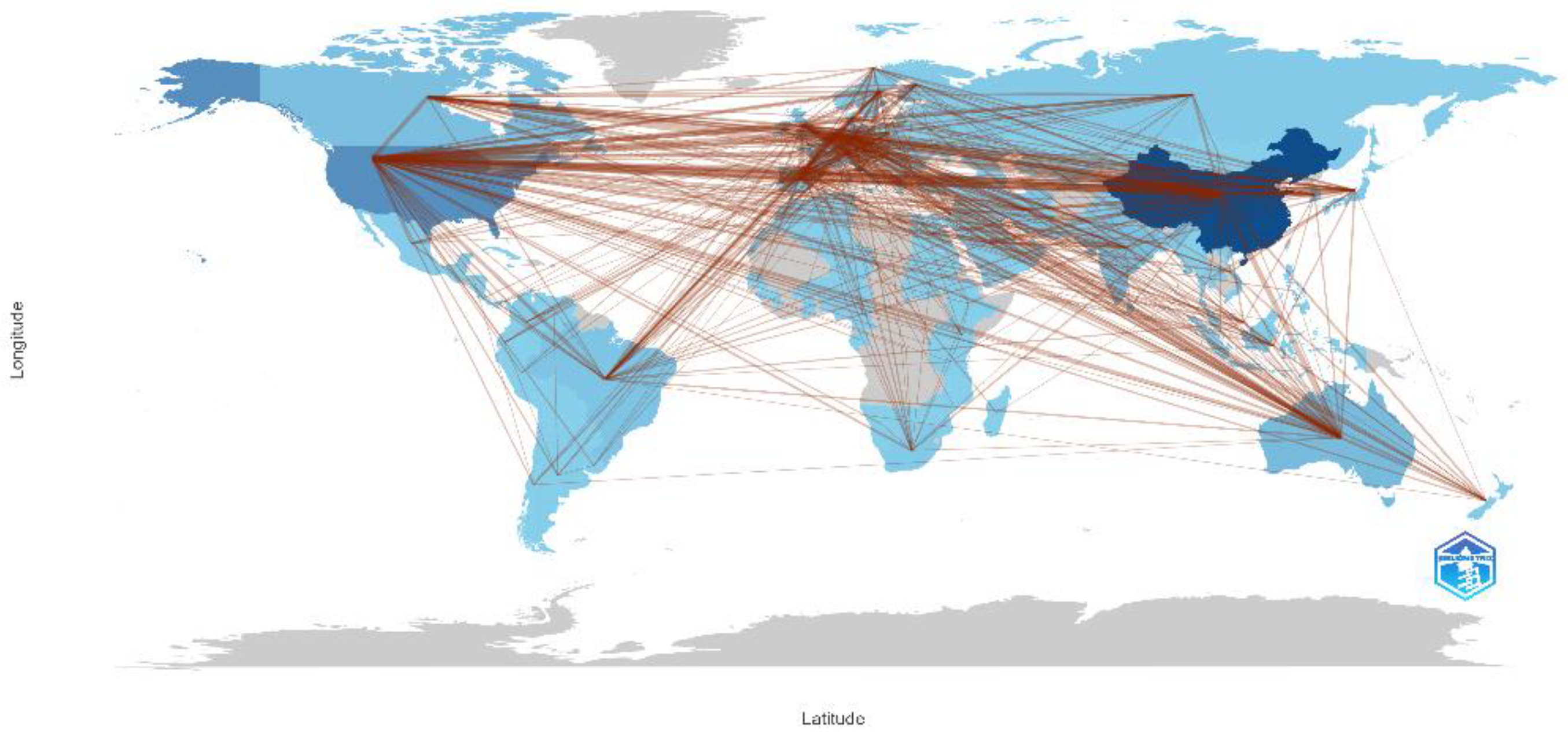

3.2. National Research Landscape and Collaboration Network

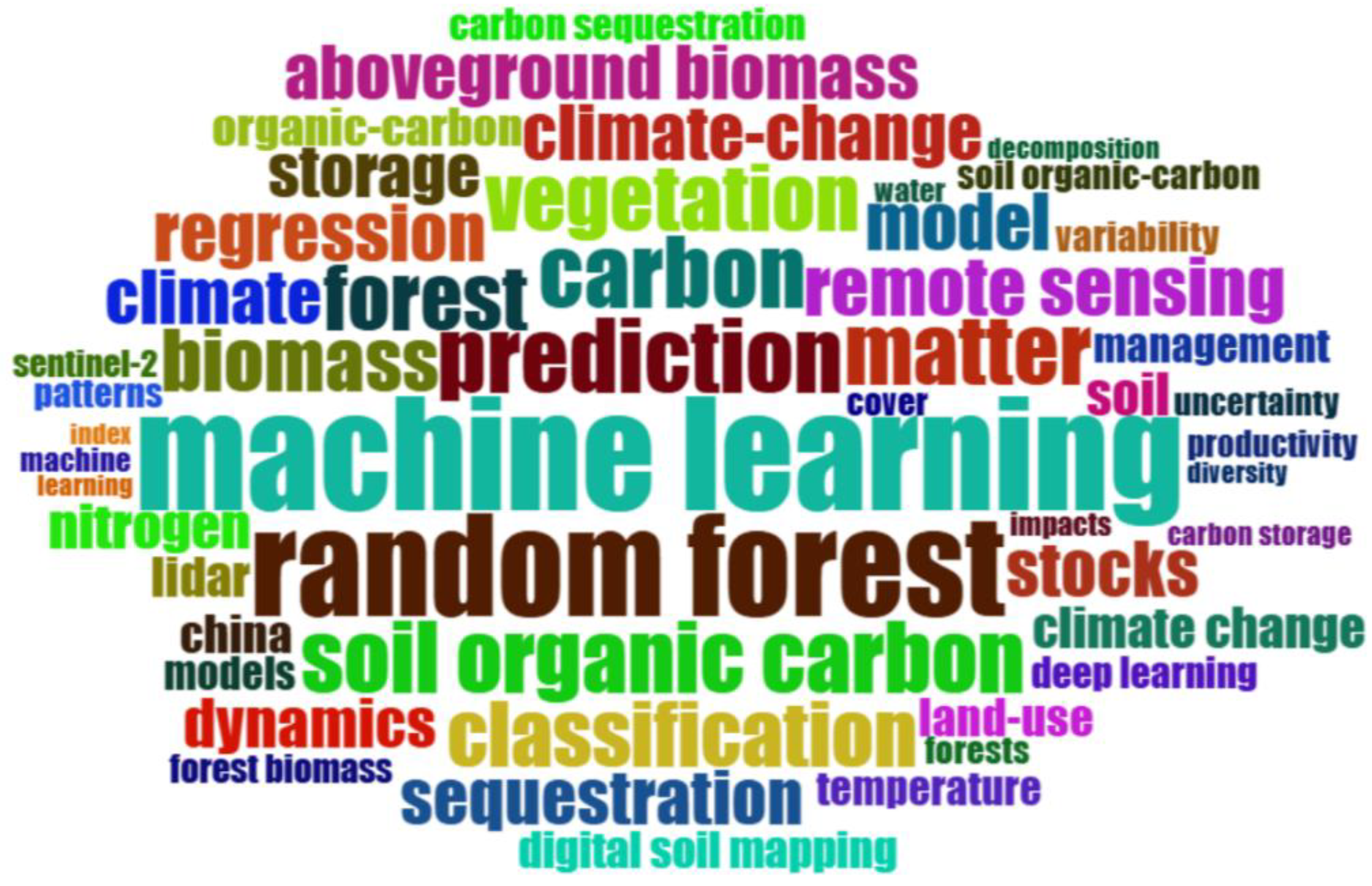

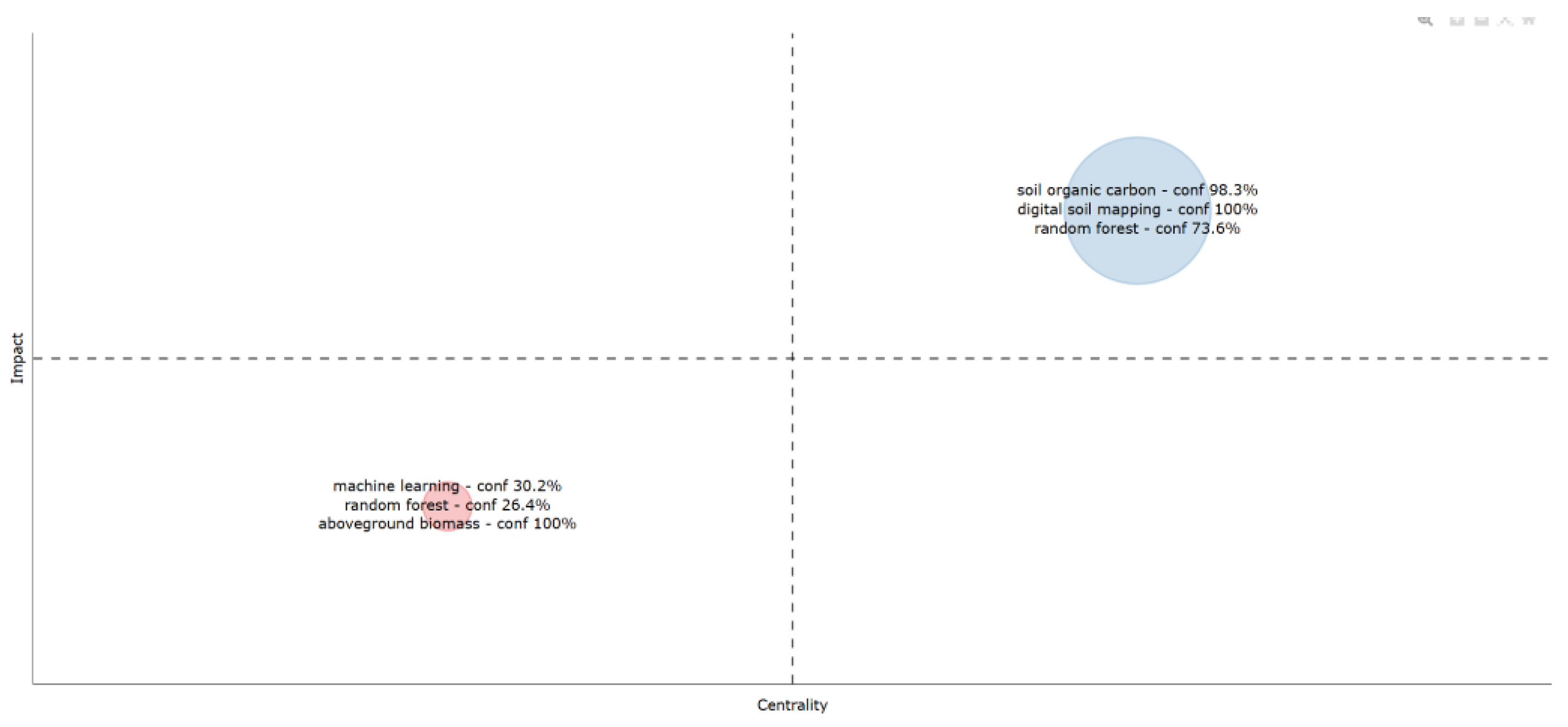

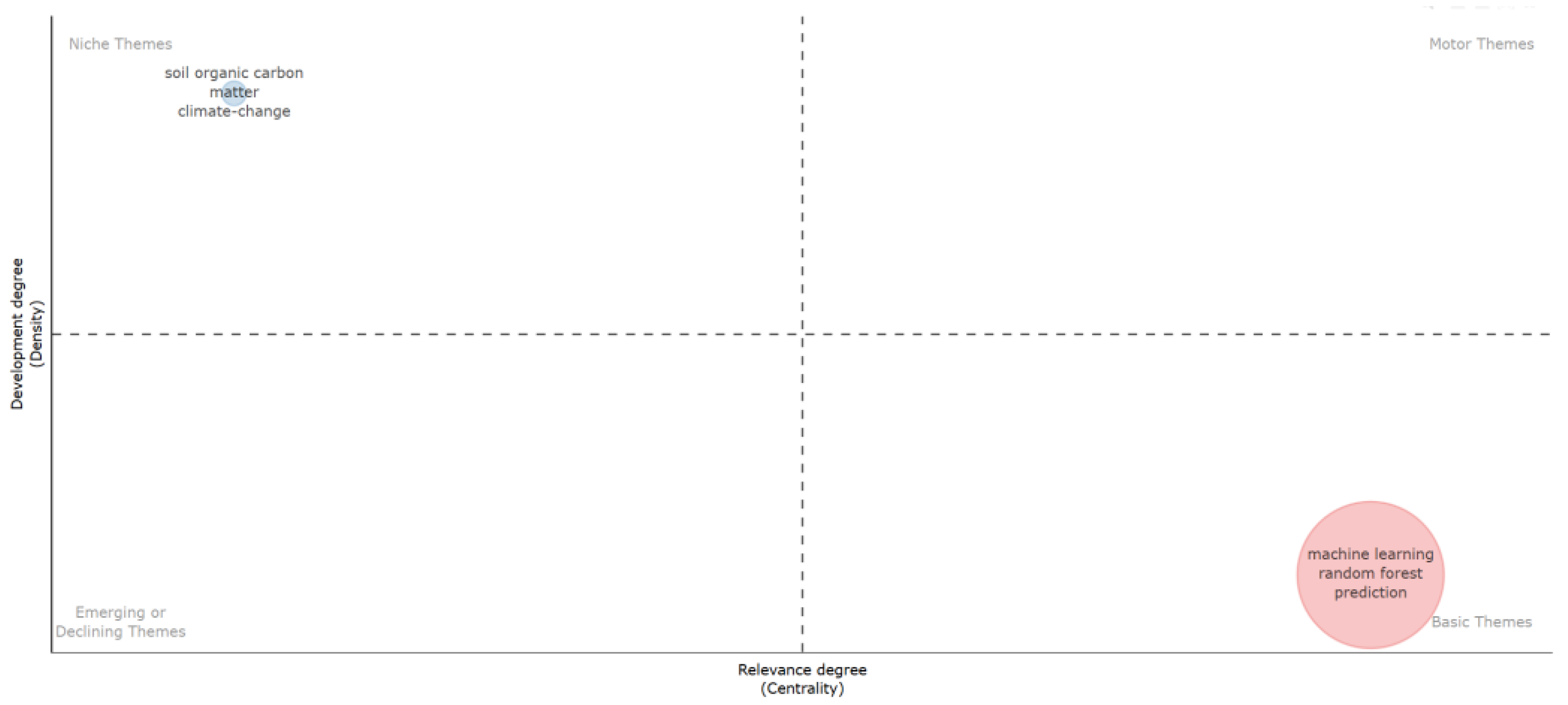

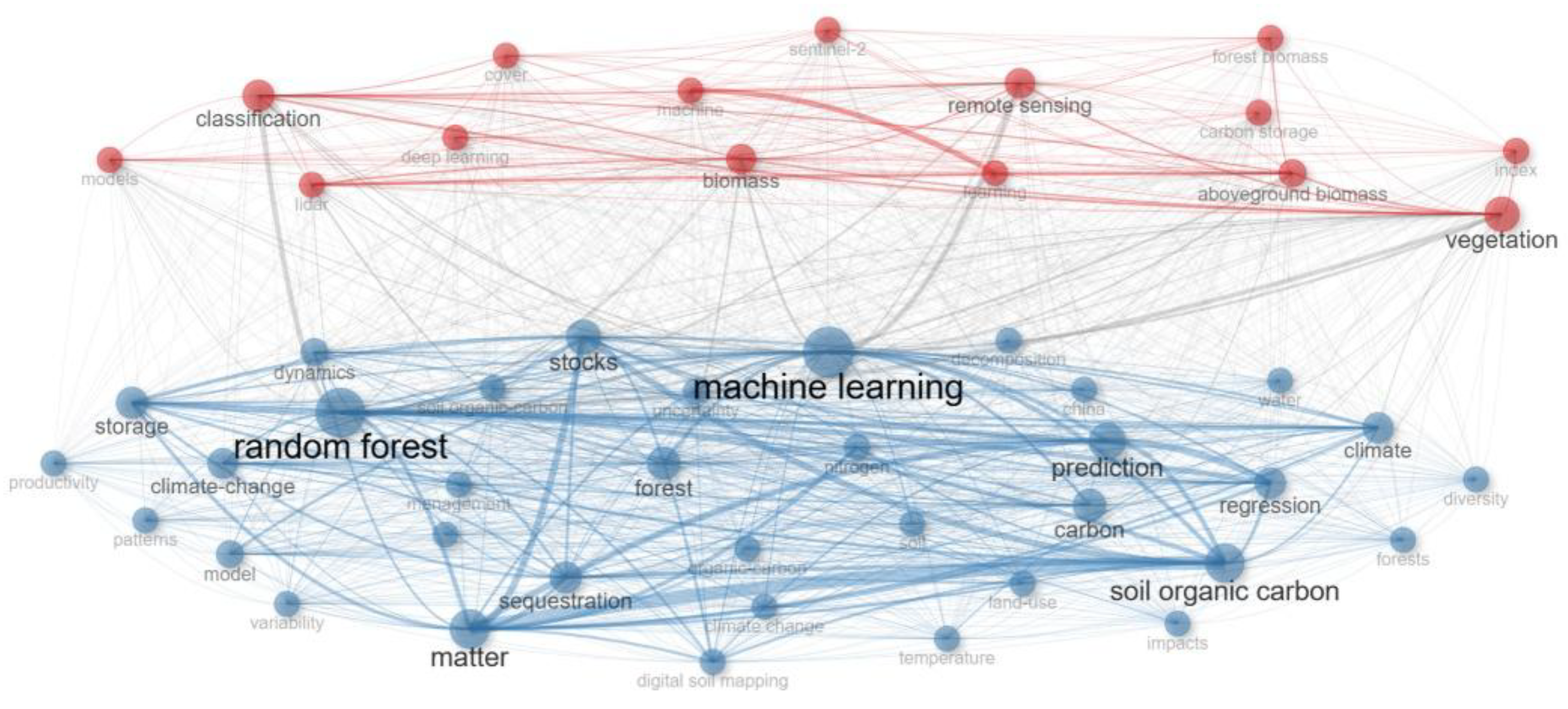

3.3. Keyword Clustering and Research Topic Identification

3.4. Evolution of Research Hotspots and Methodologies

4. Discussion

4.1. Task Alignment and Applicability Differences of AI Algorithms in Natural Carbon Sink Research

4.2. Evolutionary Mechanisms of AI-Enabled Natural Carbon Sink Research

4.3. Application Challenges and Future Prospects

| Research Pain Point | Current Technical Limitations | Future Research Trends | Key Technologies and Methods | Potential Application Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Heterogeneity and Missing Data Issues | Difficult integration of highly heterogeneous spatiotemporal remote sensing and field data; lack of high-quality training datasets | Building an integrated system combining remote sensing, ground-based, and IoT data | Multi-source data fusion, spatiotemporal interpolation, self-supervised learning | Improve model accuracy, generalizability, and regional adaptability |

| Model Opacity and Lack of Interpretability | Traditional DL “black box” fails to reveal underlying mechanisms | Advancing XAI and causal learning modeling frameworks | SHAP, LIME, causal graphs, feature attribution | Enhance result credibility and support policy formulation |

| Lack of Process-Based Mechanistic Drivers | Purely data-driven models overlook ecological-climatic process mechanisms | Model integration: Hybrid paradigm combining physical models and AI | Hybrid models, ecological mechanism embedding | Deepen understanding of natural system structure and evolutionary mechanisms |

| Static Estimation Lacks Predictive Power | Focus on current-state estimation, unable to address future scenario changes | “Prediction—Explanation—Intervention” three-stage modeling framework | Multi-scenario simulation, GNN, reinforcement learning | Support carbon neutrality scenario modeling and decision optimization |

| Lack of Application-Oriented Transformation | Algorithm engineering disconnected from management, industry, and governance practices | Promoting a “Technology–Policy–Practice” integration mechanism | Decision support systems, digital twin ecological platforms | Build a “measurable, manageable, and controllable” carbon sink management system |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global CCS Institute (2023) Global status of CCS 2023. Melbourne, Global CCS Institute.

- Aleissaee, A. A., Kumar, A., Anwer, R. M., Khan, S. H., Cholakkal, H., Xia, G. & Khan, F. S. (2022) Transformers in remote sensing: a survey. Remote. Sens., 15, 1860. [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D. M. (2023) Current status and emerging perspectives of coastal blue carbon ecosystems. Carbon Footprints, 2, N/A-N/A. [CrossRef]

- Amziane, A., Losson, O., Mathon, B. & Macaire, L. (2023) MSFA-net: a convolutional neural network based on multispectral filter arrays for texture feature extraction. Pattern Recognition Letters, 168, 93-99. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M. & Cuccurullo, C. (2017) Bibliometrix: an r-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11, 959-975. [CrossRef]

- Bartell, S. M. (2024) Biophysical economy: theory, challenges, and sustainability, CRC Press.

- Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. (2016) Random forest in remote sensing: a review of applications and future directions. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing, 114, 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Besnard, S., Carvalhais, N., Arain, M. A., Black, A. T., Brede, B., Buchmann, N., Chen, J., Clevers, J. G. P. W., Dutrieux, L. P., Gans, F., Herold, M., Jung, M., Kosugi, Y., Knohl, A., Law, B. E., Paul Limoges, E., Lohila, A., Merbold, L., Roupsard, O., Valentini, R., Wolf, S., Zhang, X. & Reichstein, M. (2019) Memory effects of climate and vegetation affecting net ecosystem CO2 fluxes in global forests. PLoS ONE, 14. [CrossRef]

- Besnard, S., Carvalhais, N., Arain, M. A., Black, A., Brede, B., Buchmann, N., Chen, J., Clevers, J. G. W., Dutrieux, L. P. & Gans, F. (2019) Memory effects of climate and vegetation affecting net ecosystem CO2 fluxes in global forests. PloS one, 14, e0211510. [CrossRef]

- Bhavana, B., Raju, S. P., Kodipalli, A. & Rao, T. (2024) Carbon dioxide emission by cars: a performance analysis of diverse machine learning regressors and interpretation using explainable AI. 2024 3rd International Conference for Advancement in Technology (ICONAT), 1-6.

- Bracarense, N., Bawack, R. E., Fosso Wamba, S. & Carillo, K. D. A. (2022) Artificial intelligence and sustainability: a bibliometric analysis and future research directions. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 14, 9. [CrossRef]

- Bricklemyer, R. S., Lawrence, R. L., Miller, P. R. & Battogtokh, N. (2006) Predicting tillage practices and agricultural soil disturbance in north central montana with landsat imagery. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 114, 210-216. [CrossRef]

- Canadell, J. G. & Raupach, M. R. (2008) Managing forests for climate change mitigation. science, 320, 1456-1457. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z., Han, M., Wang, J. & Jia, M. (2025) CarbonChat: large language model-based corporate carbon emission analysis and climate knowledge q&a system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.02031.

- Caruso, C. M., Soda, P. & Guarrasi, V. (2024) MARIA: a multimodal transformer model for incomplete healthcare data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14810. [CrossRef]

- Change, I. P. O. C. (2014) AR5 climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Chauhan, K., Tomar, H., Kamal, K. & Goel, P. (2023) Feature extraction from image sensing (remote): image segmentation 2023 5th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N), IEEE.

- Chen, C. (2016) CiteSpace: a practical guide for mapping scientific literature, Nova Science Publishers Hauppauge, NY, USA.

- Chen, G., Hay, G. J. & Zhou, Y. (2010) Estimation of forest height, biomass and volume using support vector regression and segmentation from lidar transects and quickbird imagery. 2010 18th International Conference on Geoinformatics, 1-4.

- Chen, Y., Fan, K., Chang, Y. & Moriyama, T. (2023) Special issue review: artificial intelligence and machine learning applications in remote sensing, MDPI.

- Cheng, F., Ou, G., Wang, M. & Liu, C. (2024) Remote sensing estimation of forest carbon stock based on machine learning algorithms. Forests, 15, 681. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Zhou, X., Zhao, H., Gu, J., Wang, X. & Zhao, J. (2024) Large language model for low-carbon energy transition: roles and challenges 2024 4th Power System and Green Energy Conference (PSGEC), IEEE.

- Cohrs, K., Varando, G., Carvalhais, N., Reichstein, M. & Camps-Valls, G. (2024) Causal hybrid modeling with double machine learning—applications in carbon flux modeling. Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 5.

- Da Silva, A. F., Nathaniel, J., Wong, K. C., Watson, C., Wang, H., Singh, J., Chamon, A. A. & Klein, L. (2022a) Netzeroco 2, an ai framework for accelerated nature-based carbon sequestration 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), IEEE.

- Da Silva, A. F., Nathaniel, J., Wong, K. C., Watson, C., Wang, H., Singh, J., Chamon, A. A. & Klein, L. (2022b) Netzeroco 2, an ai framework for accelerated nature-based carbon sequestration 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), IEEE.

- Da Silva, A. F., Nathaniel, J., Wong, K. C., Watson, C., Wang, H., Singh, J., Chamon, A. A. & Klein, L. (2022c) Netzeroco 2, an ai framework for accelerated nature-based carbon sequestration 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), IEEE.

- Dąbrowska-Zielińska, K., Budzynska, M., Tomaszewska, M. A., Malińska, A., Gatkowska, M., Bartold, M. & Malek, I. (2016) Assessment of carbon flux and soil moisture in wetlands applying sentinel-1 data. Remote. Sens., 8, 756. [CrossRef]

- Dai, F., Kahrl, F., Gordon, J. A., Perron, J., Chen, Z., Liu, Z., Yu, Y., Zhu, B., Xie, Y. & Yuan, Y. (2023) US-china coordination on carbon neutrality: an analytical framework. Climate Policy, 23, 929-943. [CrossRef]

- Dantas, D., Terra, M. D. C. N., Schorr, L. P. B. & Calegario, N. (2021) Machine learning for carbon stock prediction in a tropical forest in southeastern brazil. Revista Bosque, 42, 131-140.

- Delbeke, J., Runge-Metzger, A., Slingenberg, Y. & Werksman, J. (2019) The paris agreement Towards a climate-neutral Europe, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Dharumarajan, S., Kalaiselvi, B., Suputhra, A., Lalitha, M., Vasundhara, R., Kumar, K. S. A., Nair, K. M., Hegde, R., Singh, S. K. & Lagacherie, P. (2021) Digital soil mapping of soil organic carbon stocks in western ghats, south india. Geoderma Regional, 25. [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y., Zhang, C., Liu, J., Liang, Y., Hou, X. & Gong, X. (2011) Optimization model to estimate mount tai forest biomass based on remote sensing Conference on Control Technology and Applications.

- Díaz, E., Adsuara, J. E., Martínez, Á. M., Piles, M. & Camps-Valls, G. (2022) Inferring causal relations from observational long-term carbon and water fluxes records. Scientific Reports, 12. [CrossRef]

- Diligenti, M., Roychowdhury, S. & Gori, M. (2017) Integrating prior knowledge into deep learning. 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), 920-923.

- Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A. & Kleypas, J. A. (2009) Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Annual Review of Marine Science, 1, 169-192. [CrossRef]

- Ethayarajh, K. & Jurafsky, D. (2021) Attention flows are shapley value explanations Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Fang, J., Bowman, K., Zhao, W., Lian, X. & Gentine, P. (2024) Differentiable land model reveals global environmental controls on ecological parameters.

- Fang, J., Fang, J., Chen, B., Zhang, H., Dilawar, A., Guo, M. & Liu, S. A. (2024) Assessing spatial representativeness of global flux tower eddy-covariance measurements using data from FLUXNET2015. Scientific Data, 11, 569. [CrossRef]

- Fetting, C. (2020) The european green deal. ESDN Report, December, 2, 53.

- Friedlingstein, P., O'Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Li, H., Luijkx, I. T. & Olsen, A. (2024) Global carbon budget 2024. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 2024, 1-133.

- Fu, Z., Chen, F., Zhou, S., Li, H. & Jiang, L. (2024) LLMCO2: advancing accurate carbon footprint prediction for LLM inferences. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02950. [CrossRef]

- Fuss, S., Canadell, J. G., Peters, G. P., Tavoni, M., Andrew, R. M., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Jones, C. D., Kraxner, F., Nakicenovic, N., Le Quéré, C., Raupach, M. R., Sharifi, A., Smith, P. & Yamagata, Y. (2014) Betting on negative emissions. Nature Climate Change, 4, 850-853. [CrossRef]

- Green, J. & Keenan, T. F. (2022) The limits of forest carbon sequestration. Science, 376, 692 - 693. [CrossRef]

- Griscom, B. W., Adams, J., Ellis, P. W., Houghton, R. A., Lomax, G., Miteva, D. A., Schlesinger, W. H., Shoch, D., Siikamäki, J. V. & Smith, P. (2017) Natural climate solutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 11645-11650. [CrossRef]

- Günen, M. A. (2022) Performance comparison of deep learning and machine learning methods in determining wetland water areas using EuroSAT dataset. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 21092-21106. [CrossRef]

- Guo-Qing, S. B. X. (2002) Radar backscatter model and its application in terrain-effect reduction of radar imagery. National Remote Sensing Bulletin.

- Halkos, G. E. & Aslanidis, P. C. (2024) Green energy pathways towards carbon neutrality. Environmental and Resource Economics, 87, 1473-1496. [CrossRef]

- Han, P., Yao, B., Cai, Q., Chen, H., Sun, W., Liang, M., Zhang, X., Zhao, M., Martin, C. & Liu, Z. (2024) Support carbon neutral goal with a high-resolution carbon monitoring system in beijing. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 105, E2461-E2481. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Li, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, H., Dong, W., Du, E., Chang, S., Ou, X., Guo, S. & Tian, Z. (2022) Towards carbon neutrality: a study on china's long-term low-carbon transition pathways and strategies. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 9, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Heroux, M. A., Shende, S., Mcinnes, L. C., Gamblin, T. & Willenbring, J. M. (2024) Toward a cohesive AI and simulation software ecosystem for scientific innovation. ArXiv, abs/2411.09507.

- Ho, V. H., Morita, H., Bachofer, F. & Ho, T. H. (2024) Random forest regression kriging modeling for soil organic carbon density estimation using multi-source environmental data in central vietnamese forests. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B. & Cheng, Y. (2023) Predicting regional carbon price in china based on multi-factor HKELM by combining secondary decomposition and ensemble learning. Plos one, 18, e0285311. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Luo, L. & Pu, C. (2022) Self-supervised convolutional neural network via spectral attention module for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 19, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Yang, L., Zhang, L., Pu, Y., Yang, C., Wu, Q., Cai, Y., Shen, F. & Zhou, C. (2022) A review on digital mapping of soil carbon in cropland: progress, challenge, and prospect. Environmental Research Letters, 17, 123004. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Song, X., Wang, Y. P., Canadell, J. G., Luo, Y., Ciais, P., Chen, A., Hong, S., Wang, Y., Tao, F., Li, W., Xu, Y., Mirzaeitalarposhti, R., Elbasiouny, H., Savin, I., Shchepashchenko, D., Rossel, R., Goll, D. S., Chang, J., Houlton, B. Z., Wu, H., Yang, F., Feng, X., Chen, Y., Liu, Y., Niu, S. & Zhang, G. L. (2024) Size, distribution, and vulnerability of the global soil inorganic carbon. Science, 384, 233-239. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Wang, Y. P. & Ziehn, T. (2021) Nonlinear interactions of land carbon cycle feedbacks in earth system models. Global Change Biology, 28, 296 - 306. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (2022) Global warming of 1.5°c: IPCC special report on impacts of global warming of 1.5°c above pre-industrial levels in context of strengthening response to climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Jaber, S. M., Lant, C. & Al-Qinna, M. I. (2011) Estimating spatial variations in soil organic carbon using satellite hyperspectral data and map algebra. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 32, 5077 - 5103. [CrossRef]

- Justice, C. O., Townshend, J., Vermote, E. F., Masuoka, E., Wolfe, R. E., Saleous, N., Roy, D. P. & Morisette, J. T. (2002) An overview of MODIS land data processing and product status. Remote sensing of Environment, 83, 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Kabashkin, I. & Susanin, V. (2024) Unified ecosystem for data sharing and AI-driven predictive maintenance in aviation. Computers, 13, 318. [CrossRef]

- Kersten, T., Wong, H. M., Jumelet, J. & Hupkes, D. (2021) Attention vs non-attention for a shapley-based explanation method. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.12424.

- Khan, M. S., Jeon, S. B. & Jeong, M. (2021) Gap-filling eddy covariance latent heat flux: inter-comparison of four machine learning model predictions and uncertainties in forest ecosystem. Remote Sensing, 13, 4976. [CrossRef]

- Kia, S. (2017) Uncertainty associated with scaling spectral indices of carbon fluxes at various spatial and temporal scales, University of Southampton.

- Kim, S. T., Conklin, S. D., Redan, B. W. & Ho, K. K. H. Y. (2024) Determination of the nutrient and toxic element content of wild-collected and cultivated seaweeds from hawai‘i. ACS Food Science & Technology, 4, 595-605. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., Sajjad, H., Tripathy, B. R., Ahmed, R. U. & Mandal, V. P. (2017) Prediction of spatial soil organic carbon distribution using sentinel-2a and field inventory data in sariska tiger reserve. Natural Hazards, 90, 693-704. [CrossRef]

- La Notte, A. (2024) How to account for nature-based solutions as the ecological assets that support economy and society. Nature-Based Solutions, 6, 100164. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. (2004) Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma, 123, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, P. J., Schwieder, M., Pötzschner, F., Pinto, J. R. R., Teixeira, A. M. C., Pedroni, F., Sanchez, M., Rogass, C., van der Linden, S., Bustamante, M. M. C. & Hostert, P. (2018) From sample to pixel: multi-scale remote sensing data for upscaling aboveground carbon data in heterogeneous landscapes. Ecosphere.

- Li, S., Wang, H., Song, L., Wang, P., Cui, L. & Lin, T. (2020) An adaptive data fusion strategy for fault diagnosis based on the convolutional neural network. Measurement, 165, 108122. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, M., Li, C. & Liu, Z. (2020) Forest aboveground biomass estimation using landsat 8 and sentinel-1a data with machine learning algorithms. Scientific reports, 10, 9952. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, X. & Guo, Y. (2024) CNN-trans-SPP: a small transformer with CNN for stock price prediction. Electronic Research Archive.

- Liddicoat, C., Maschmedt, D., Clifford, D., Searle, R. D., Herrmann, T. N., Macdonald, L. M. & Baldock, J. A. (2015) Predictive mapping of soil organic carbon stocks in south australia’s agricultural zone. Soil Research, 53, 956-973. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G., Migliavacca, M., Reimers, C., Kraft, B., Reichstein, M., Richardson, A. D., Wingate, L., Delpierre, N., Yang, H. & Winkler, A. J. (2024) DeepPhenoMem v1.0: deep learning modelling of canopy greenness dynamics accounting for multi-variate meteorological memory effects on vegetation phenology. Geoscientific Model Development.

- Liu, H., Mou, C., Yuan, J., Chen, Z., Zhong, L. & Cui, X. (2024) Estimating urban forests biomass with LiDAR by using deep learning foundation models. Remote Sensing, 16, 1643. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zhou, Y., Ma, J., Zhang, Y. & He, L. (2025) Domain-specific question-answering systems: a case study of a carbon neutrality knowledge base. Sustainability, 17, 2192. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Lei, H., Wang, X. & Paredes, P. (2025) High-resolution mapping of evapotranspiration over heterogeneous cropland affected by soil salinity. Agricultural Water Management.

- Lyu, G., Wang, X., Huang, X., Xu, J., Li, S., Cui, G. & Huang, H. (2024) Toward a more robust estimation of forest biomass carbon stock and carbon sink in mountainous region: a case study in tibet, china. Remote. Sens., 16, 1481. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., Wang, X., Mo, B., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zong, W. & Bai, M. (2025) Knowledge map-based analysis of carbon sequestration research dynamics in forest and grass systems: a bibliometric analysis. Atmosphere, 16, 474. [CrossRef]

- Maguluri, L. P., Geetha, B., Banerjee, S., Srivastava, S. S., Nageswaran, A., Mudalkar, P. K. & Raj, G. B. (2024) Sustainable agriculture and climate change: a deep learning approach to remote sensing for food security monitoring. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems Sciences, 1-13.

- Mas, J. F. & Flores, J. J. (2008) The application of artificial neural networks to the analysis of remotely sensed data. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 29, 617-663. [CrossRef]

- Masria, A. & Abouelsaad, O. (2025) Artificial intelligence applications in coastal engineering and its challenges–a review. Continental Shelf Research, 105425. [CrossRef]

- Mei, L., Rozanov, V., Jiao, Z. & Burrows, J. P. (2022) A new snow bidirectional reflectance distribution function model in spectral regions from UV to SWIR: model development and application to ground-based, aircraft and satellite observations. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 188, 269-285. [CrossRef]

- Meng, G., Wen, Y., Zhang, M., Gu, Y., Xiong, W., Wang, Z. & Niu, S. (2022) The status and development proposal of carbon sources and sinks monitoring satellite system. Carbon Neutrality, 1, 32. [CrossRef]

- Miehe, R., Finkbeiner, M., Sauer, A. & Bauernhansl, T. (2022a) A system thinking normative approach towards integrating the environment into value-added accounting—paving the way from carbon to environmental neutrality. Sustainability, 14, 13603. [CrossRef]

- Miehe, R., Finkbeiner, M., Sauer, A. & Bauernhansl, T. (2022b) A system thinking normative approach towards integrating the environment into value-added accounting—paving the way from carbon to environmental neutrality. Sustainability.

- Milodowski, D. T., Smallman, T. L. & Williams, M. (2023) Scale variance in the carbon dynamics of fragmented, mixed-use landscapes estimated using model–data fusion. Biogeosciences.

- Moffat, A. M., Papale, D., Reichstein, M., Hollinger, D. Y., Richardson, A. D., Barr, A. G., Beckstein, C., Braswell, B. H., Churkina, G. & Desai, A. R. (2007) Comprehensive comparison of gap-filling techniques for eddy covariance net carbon fluxes. Agricultural and forest meteorology, 147, 209-232. [CrossRef]

- Mou, C., Xie, Z., Li, Y., Liu, H., Yang, S. & Cui, X. (2023) Urban carbon price forecasting by fusing remote sensing images and historical price data. Forests.

- Mu, H., Li, H. & Chen, Z. (2024) Research on the impact of change features for remote sensing image change detection MIPPR 2023: Remote Sensing Image Processing, Geographic Information Systems, and Other Applications, SPIE.

- Nguyen, A. & Saha, S. (2024) Machine learning and multi-source remote sensing in forest carbon stock estimation: a review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.17624. [CrossRef]

- Nie, M., Chen, D., Chen, H. & Wang, D. (2025) AutoMTNAS: automated meta-reinforcement learning on graph tokenization for graph neural architecture search. Knowledge-Based Systems, 310, 113023. [CrossRef]

- Niu, X., Liu, Y. N. & Ma, M. (2024) A transformer-based model for time series prediction of remote sensing data International Conference on Intelligent Computing.

- Oehmcke, S., Li, L., Trepekli, K., Revenga, J. C., Nord-Larsen, T., Gieseke, F. & Igel, C. (2024) Deep point cloud regression for above-ground forest biomass estimation from airborne LiDAR. Remote Sensing of Environment, 302, 113968. [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, F. (2023a) AI-powered carbon accounting: transforming ESG reporting standards for a sustainable global economy. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Ogunyemi, F. (2023b) AI-powered carbon accounting: transforming ESG reporting standards for a sustainable global economy. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research in Science, Engineering and Technology, 6. [CrossRef]

- Orobinskaya, V. N., Mishina, T. N., Mazurenko, A. P. & Mishin, V. V. (2024) Problems of interpretability and transparency of decisions made by AI 2024 6th International Conference on Control Systems, Mathematical Modeling, Automation and Energy Efficiency (SUMMA), IEEE.

- Padarian, J., Minasny, B. & Mcbratney, A. B. (2019) Using deep learning for digital soil mapping. SOIL, 5, 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Padarian, J., Minasny, B. & Mcbratney, A. B. (2019) Online machine learning for collaborative biophysical modelling. Environmental Modelling & Software, 122, 104548. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., Zhao, J. & Xu, J. (2019) An object-based and heterogeneous segment filter convolutional neural network for high-resolution remote sensing image classification. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 40, 5892 - 5916. [CrossRef]

- Paris Agreement (2015) Paris agreement report of the conference of the parties to the United Nations framework convention on climate change (21st session, 2015: Paris). Retrived December, HeinOnline.

- Park, J., Choi, B. & Lee, S. (2022) Examining the impact of adaptive convolution on natural language understanding. Expert Systems with Applications, 189, 116044. [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, M., Kamangir, H., Starek, M. J. & Tissot, P. E. (2020) Review and evaluation of deep learning architectures for efficient land cover mapping with UAS hyper-spatial imagery: a case study over a wetland. Remote. Sens., 12, 959. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W., Haron, N. A., Alias, A. H. & Law, T. H. (2023) Knowledge map of climate change and transportation: a bibliometric analysis based on CiteSpace. Atmosphere, 14, 434. [CrossRef]

- Peón, J., Fernández, S., Recondo, C. & Calleja, J. F. (2017) Evaluation of the spectral characteristics of five hyperspectral and multispectral sensors for soil organic carbon estimation in burned areas. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 26, 230-239. [CrossRef]

- Piao, S., He, Y., Wang, X. & Chen, F. (2022) Estimation of china’s terrestrial ecosystem carbon sink: methods, progress and prospects. Science China Earth Sciences, 65, 641-651. [CrossRef]

- Pimenow, S., Pimenowa, O., Prus, P. & Niklas, A. (2025) The impact of artificial intelligence on the sustainability of regional ecosystems: current challenges and future prospects. Sustainability, 17, 4795. [CrossRef]

- Protocol, K. (1997) United nations framework convention on climate change. Kyoto Protocol, Kyoto, 19, 1-21.

- Qian, H., Bao, N., Meng, D., Zhou, B., Lei, H. & Li, H. (2024) Mapping and classification of liao river delta coastal wetland based on time series and multi-source GaoFen images using stacking ensemble model. Ecological Informatics, 80, 102488. [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. (2024) Enhancing carbon sequestration through tropical forest management: a review. Journal of Forestry and Natural Resources, 3, 33-48.

- Rastetter, E. B., Griffin, K. L., Kwiatkowski, B. L. & Kling, G. W. (2023) Ecosystem feedbacks constrain the effect of day-to-day weather variability on land–atmosphere carbon exchange. Global Change Biology, 29, 6093 - 6105. [CrossRef]

- Rasul, K., Ashok, A., Williams, A. R., Ghonia, H., Bhagwatkar, R., Khorasani, A., Bayazi, M. J. D., Adamopoulos, G., Riachi, R. & Hassen, N. (2023) Lag-llama: towards foundation models for probabilistic time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.08278.

- Reichstein, M., Camps-Valls, G., Stevens, B., Jung, M., Denzler, J., Carvalhais, N. & Prabhat, F. (2019a) Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven earth system science. Nature, 566, 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M., Camps-Valls, G., Stevens, B., Jung, M., Denzler, J., Carvalhais, N. & Prabhat, F. (2019b) Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven earth system science. Nature, 566, 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Reiersen, G., Dao, D., Lütjens, B., Klemmer, K., Amara, K., Steinegger, A., Zhang, C. & Zhu, X. (2022) ReforesTree: a dataset for estimating tropical forest carbon stock with deep learning and aerial imagery Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Rolnick, D., Donti, P. L., Kaack, L. H., Kochanski, K., Lacoste, A., Sankaran, K., Ross, A. S., Milojevic-Dupont, N., Jaques, N. & Waldman-Brown, A. (2022) Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 55, 1-96. [CrossRef]

- Romijn, E., Herold, M., Kooistra, L., Murdiyarso, D. & Verchot, L. (2012) Assessing capacities of non-annex i countries for national forest monitoring in the context of REDD+. Environmental science & policy, 19, 33-48.

- Rossel, R. V. & Behrens, T. (2010) Using data mining to model and interpret soil diffuse reflectance spectra. Geoderma, 158, 46-54. [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, S., Diligenti, M. & Gori, M. (2021) Regularizing deep networks with prior knowledge: a constraint-based approach. Knowl. Based Syst., 222, 106989. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, R., Arencibia-Jorge, R., Tagüeña, J., Jiménez-Andrade, J. L. & Carrillo-Calvet, H. (2024) Exploring research on ecotechnology through artificial intelligence and bibliometric maps. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, 21, 100386. [CrossRef]

- Safari, A., Sohrabi, H., Powell, S. & Shataee, S. (2017) A comparative assessment of multi-temporal landsat 8 and machine learning algorithms for estimating aboveground carbon stock in coppice oak forests. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 38, 6407-6432. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, Y. & Upadhyay, V. K. (2024) Environmental application of digital twins: a review. Environmental Risk and Resilience in the Changing World: Integrated Geospatial AI and Multidimensional Approach, 287-295.

- Sangha, K. K., Ahammad, R., Russell-Smith, J. & Costanza, R. (2024) Payments for ecosystem services opportunities for emerging nature-based solutions: integrating indigenous perspectives from australia. Ecosystem Services, 66, 101600. [CrossRef]

- Schimel, D., Pavlick, R., Fisher, J. B., Asner, G. P., Saatchi, S., Townsend, P., Miller, C., Frankenberg, C., Hibbard, K. & Cox, P. (2015) Observing terrestrial ecosystems and the carbon cycle from space. Global Change Biology, 21, 1762-1776. [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T. D., Wirsenius, S., Beringer, T. & Dumas, P. (2018) Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature, 564, 249-253. [CrossRef]

- Sen, D., Deora, B. S. & Vaishnav, A. (2025) Explainable deep learning for time series analysis: integrating SHAP and LIME in LSTM-based models. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management.

- Shah, S. A. A., Manzoor, M. A. & Bais, A. (2020) Canopy height estimation at landsat resolution using convolutional neural networks. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr., 2, 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Soman, M. K. & Indu, J. (2022) Sentinel-1 based inland water dynamics mapping system (SIMS). Environmental Modelling & Software, 149, 105305. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Yang, L., Li, B., Hu, Y., Wang, A., Zhou, W., Cui, X. & Liu, Y. (2017) Spatial prediction of soil organic matter using a hybrid geostatistical model of an extreme learning machine and ordinary kriging. Sustainability, 9, 754. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., Liang, L., Zhao, X., Zhang, Y., Li, M. & Wang, Y. (2024) Estimation of terrestrial ecosystem NEP coupled with remote sensing and ground data 2024 12th International Conference on Agro-Geoinformatics (Agro-Geoinformatics), IEEE.

- Streck, C., Keenlyside, P. & Von Unger, M. (2016) The paris agreement: a new beginning. Journal for European Environmental & Planning Law, 13, 3-29. [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A., Gabbasova, I., Komissarov, M., Suleymanov, R., Garipov, T., Tuktarova, I. & Belan, L. (2023) Random forest modeling of soil properties in saline semi-arid areas. Agriculture, 13, 976. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N., Hossain, S. Z., Abusaad, M., Alanbar, N., Senan, Y. & Razzak, S. A. (2022) Prediction of biodiesel production from microalgal oil using bayesian optimization algorithm-based machine learning approaches. Fuel, 309, 122184. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P., Wu, Y., Xiao, J., Hui, J., Hu, J., Zhao, F., Qiu, L. & Liu, S. (2019) Remote sensing and modeling fusion for investigating the ecosystem water-carbon coupling processes. Science of the total environment, 697, 134064. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T., Yamamoto, K., Miyachi, Y., Senda, Y. & Tsuzuku, M. (2006) The penetration rate of laser pulses transmitted from a small-footprint airborne LiDAR: a case study in closed canopy, middle-aged pure sugi (cryptomeria japonica d. Don) and hinoki cypress (chamaecyparis obtusa sieb. Et zucc.) Stands in japan. Journal of Forest Research, 11, 117-123. [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, S. & Islam, K. A. (2023) Development of trustable deep learning model in remote sensing through explainable-AI method selection 2023 IEEE 14th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), IEEE.

- Tempel, F., Groos, D., Ihlen, E. A. F., Adde, L. & Strümke, I. (2024) Choose your explanation: a comparison of SHAP and GradCAM in human activity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16003. [CrossRef]

- Terziyan, V. Y. & Vitko, O. (2023) Causality-aware convolutional neural networks for advanced image classification and generation. Procedia Computer Science.

- Tian, H., Zhu, J., Lei, X., Chen, X., Zeng, L., Jian, Z., Li, F. & Xiao, W. (2024) Timber and carbon sequestration potential of chinese forests under different forest management scenarios. Advances in Climate Change Research, 15, 1121-1129. [CrossRef]

- Tsui, O. W., Coops, N. C., Wulder, M. A. & Marshall, P. L. (2013) Integrating airborne LiDAR and space-borne radar via multivariate kriging to estimate above-ground biomass. Remote Sensing of Environment, 139, 340-352. [CrossRef]

- Ugbemuna Ugbaje, S., Karunaratne, S., Bishop, T. F. A., Gregory, L., Searle, R., Coelli, K. & Farrell, M. (2024) Space-time mapping of soil organic carbon stock and its local drivers: potential for use in carbon accounting. Geoderma.

- Unesco (2023) UNESCO's recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence: key facts, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Vahedi, A. A. (2017) Monitoring soil carbon pool in the hyrcanian coastal plain forest of iran: artificial neural network application in comparison with developing traditional models. Catena, 152, 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Vašát, R., Kodešová, R. & Borůvka, L. (2017) Ensemble predictive model for more accurate soil organic carbon spectroscopic estimation. Computers & Geosciences, 104, 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Velastegui-Montoya, A., Montalván-Burbano, N., Peña-Villacreses, G., de Lima, A. & Herrera-Franco, G. (2022) Land use and land cover in tropical forest: global research. Forests, 13, 1709. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Chen, Y., Yan, Z. & Liu, W. (2024) Integrating remote sensing data and CNN-LSTM-attention techniques for improved forest stock volume estimation: a comprehensive analysis of baishanzu forest park, china. Remote. Sens., 16, 324. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Liu, J., Qin, G., Zhang, J., Zhou, J., Wu, J., Zhang, L., Thapa, P., Sanders, C. J. & Santos, I. R. (2023) Coastal blue carbon in china as a nature-based solution toward carbon neutrality. The Innovation, 4. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Chen, Y., Feng, W., Yu, H., Huang, M. & Yang, Q. (2019) Transfer learning with dynamic distribution adaptation. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), 11, 1 - 25. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Feng, L., Palmer, P. I., Liu, Y., Fang, S., Bösch, H., O Dell, C. W., Tang, X., Yang, D., Liu, L. & Xia, C. (2020) Large chinese land carbon sink estimated from atmospheric carbon dioxide data. Nature, 586, 720-723. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Sun, X., Cheng, Q. & Cui, Q. (2020) An innovative random forest-based nonlinear ensemble paradigm of improved feature extraction and deep learning for carbon price forecasting. The Science of the total environment, 143099. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Yu, G., Han, L., Yao, Y., Sun, M. & Yan, Z. (2024) Ecosystem carbon exchange across china's coastal wetlands: spatial patterns, mechanisms, and magnitudes. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 345, 109859. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Bai, Y., Wang, J., Qin, F., Liu, C., Zhou, Z. & Jiao, X. (2022) A transferable learning classification model and carbon sequestration estimation of crops in farmland ecosystem. Remote Sensing, 14, 5216. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Wang, Y., Teng, F. & Ji, Y. (2023) The spatiotemporal evolution and impact mechanism of energy consumption carbon emissions in china from 2010 to 2020 by integrating multisource remote sensing data. Journal of Environmental Management, 346, 119054. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Guo, Z., Shang, D. & Li, K. (2024) Carbon trading price forecasting in digitalization social change era using an explainable machine learning approach: the case of china as emerging country evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change.

- Wang, P., Haron, N. A., Alias, A. H. & Law, T. H. (2023) Knowledge map of climate change and transportation: a bibliometric analysis based on CiteSpace. Atmosphere, 14, 434. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhang, M., Jiang, X. & Li, R. (2022) Does the COVID-19 pandemic derail US-china collaboration on carbon neutrality research? A survey. Energy Strategy Reviews, 43, 100937. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhang, W., Xia, J., Ou, D., Tian, Z. & Gao, X. (2024) Multi-scenario simulation of land-use/land-cover changes and carbon storage prediction coupled with the SD-PLUS-InVEST model: a case study of the tuojiang river basin, china. Land, 13, 1518. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. (2024) Improved random forest classification model combined with c5. 0 algorithm for vegetation feature analysis in non-agricultural environments. Scientific Reports, 14, 10367. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Yue, C., Wang, Y., Wang, X., Lyu, G., Wei, J., Yang, H. & Piao, S. (2025) Progress and challenges in remotely sensed terrestrial carbon fluxes. Geo-Spatial Information Science, 28, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, L., Li, S., Wang, Z., Zheng, M. & Song, K. (2022) Remote estimates of soil organic carbon using multi-temporal synthetic images and the probability hybrid model. Geoderma.

- Wang, X., Zhu, J., Yan, Z., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., Chen, Y. & Li, H. (2022) LaST: label-free self-distillation contrastive learning with transformer architecture for remote sensing image scene classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 19, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Were, K., Bui, D. T., Dick, Ø. B. & Singh, B. R. (2015) A comparative assessment of support vector regression, artificial neural networks, and random forests for predicting and mapping soil organic carbon stocks across an afromontane landscape. Ecological Indicators, 52, 394-403. [CrossRef]

- Whata, A. & Chimedza, C. (2022) Evaluating uses of deep learning methods for causal inference. IEEE Access, PP, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Wiesmeier, M., Barthold, F., Blank, B. & Kögel-Knabner, I. (2011) Digital mapping of soil organic matter stocks using random forest modeling in a semi-arid steppe ecosystem. Plant and soil, 340, 7-24. [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. (2018) VOSviewer. Technical Services Quarterly, 35, 219-220. [CrossRef]

- Wong, W. Y., Al-Ani, A. K. I., Hasikin, K., Khairuddin, A. S. M., Razak, S. A., Hizaddin, H. F., Mokhtar, M. I. & Azizan, M. M. (2021) Water, soil and air pollutants’ interaction on mangrove ecosystem and corresponding artificial intelligence techniques used in decision support systems-a review. Ieee Access, 9, 105532-105563. [CrossRef]

- Xi, L., Shu, Q., Sun, Y., Huang, J. & Song, H. (2023) Carbon storage estimation of mountain forests based on deep learning and multisource remote sensing data. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing, 17, 014510 - 014510. [CrossRef]

- Xie, T. & Wang, X. (2024) Investigating the nonlinear carbon reduction effect of AI: empirical insights from china’s provincial level. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12, 1353294. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., He, J. & Shu, Y. (2020) Transfer learning and deep domain adaptation. Advances and Applications in Deep Learning.

- Ye, F., Li, X. & Zhang, X. (2019) FusionCNN: a remote sensing image fusion algorithm based on deep convolutional neural networks. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78, 14683-14703. [CrossRef]

- Yewle, A. D., Mirzayeva, L. & Karakuş, O. (2025) Multi-modal data fusion and deep ensemble learning for accurate crop yield prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06062. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Sun, Y., Shi, W., Guo, D. & Zheng, N. (2021) An object-based spatiotemporal fusion model for remote sensing images. European Journal of Remote Sensing, 54, 86-101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Li, H., Miao, Y., Zhou, Z., Lyu, H. & Gong, Z. (2025) Remote sensing retrieval method based on few-shot learning: a case study of surface dissolved organic carbon in jiangsu coastal waters, china. IEEE Access, 13, 3014-3025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. & Ma, J. (2009) State of the art on remotely sensed data classification based on support vector machines. Advances in Earth Science, 24, 555-562.

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, J., Wu, W. & Tao, R. (2024) Integrating system dynamics, land change models, and machine learning to simulate and predict ecosystem carbon sequestration under RCP-SSP scenarios: fusing land and climate changes. Land, 13, 1967. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Ke, C., Dong, X., Li, J. & Feng, X. (2005) Landsat TM multispectral classification using support vector machine method in low-hill areas Image Processing and Pattern Recognition in Remote Sensing II, SPIE.

- Zhao, W., Wu, Z. & Yin, Z. (2021) Estimation of soil organic carbon content based on deep learning and quantile regression 2021 ieee international geoscience and remote sensing symposium igarss, IEEE.

- Zheng, M., Wen, Q., Xu, F. & Wu, D. (2025) Regional forest carbon stock estimation based on multi-source data and machine learning algorithms. Forests, 16, 420. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C., Li, T., Bi, R., Sanganyado, E., Huang, J., Jiang, S., Zhang, Z. & Du, H. (2023) A systematic overview, trends and global perspectives on blue carbon: a bibliometric study (2003–2021). Ecological Indicators, 148, 110063. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Wei, G., Wang, Y., Wang, B., Quan, Y., Wu, Z., Liu, J., Bian, S., Li, M. & Fan, W. (2025) Estimating regional forest carbon density using remote sensing and geographically weighted random forest models: a case study of mid-to high-latitude forests in china. Forests, 16, 96. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Wang, S. & Woodcock, C. E. (2015) Improvement and expansion of the fmask algorithm: cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection for landsats 4–7, 8, and sentinel 2 images. Remote sensing of Environment, 159, 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Zodage, P., Harianawala, H., Shaikh, H. & Kharodia, A. (2024) Explainable AI (XAI): history, basic ideas and methods. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, 3.

| Rank | Country | Articles | Frequency | % | MCP1% | Total Citations | Avg Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHINA | 1772 | 8901 | 45.6 | 27.7 | 26333 | 14.90 |

| 2 | USA | 487 | 2765 | 12.5 | 32.9 | 14395 | 29.60 |

| 3 | GERMANY | 164 | 916 | 4.2 | 55.5 | 8422 | 51.40 |

| 4 | INDIA | 144 | 599 | 3.7 | 28.5 | 2058 | 14.30 |

| 5 | AUSTRALIA | 122 | 677 | 3.1 | 46.7 | 6772 | 55.50 |

| 6 | CANADA | 97 | 527 | 2.5 | 34 | 1719 | 17.70 |

| 7 | BRAZIL | 92 | 484 | 2.4 | 42.4 | 2090 | 22.70 |

| 8 | IRAN | 87 | 318 | 2.2 | 63.2 | 2417 | 27.80 |

| 9 | FRANCE | 71 | 476 | 1.8 | 54.9 | 2205 | 31.10 |

| 10 | ITALY | 66 | 329 | 1.7 | 45.5 | 2168 | 32.80 |

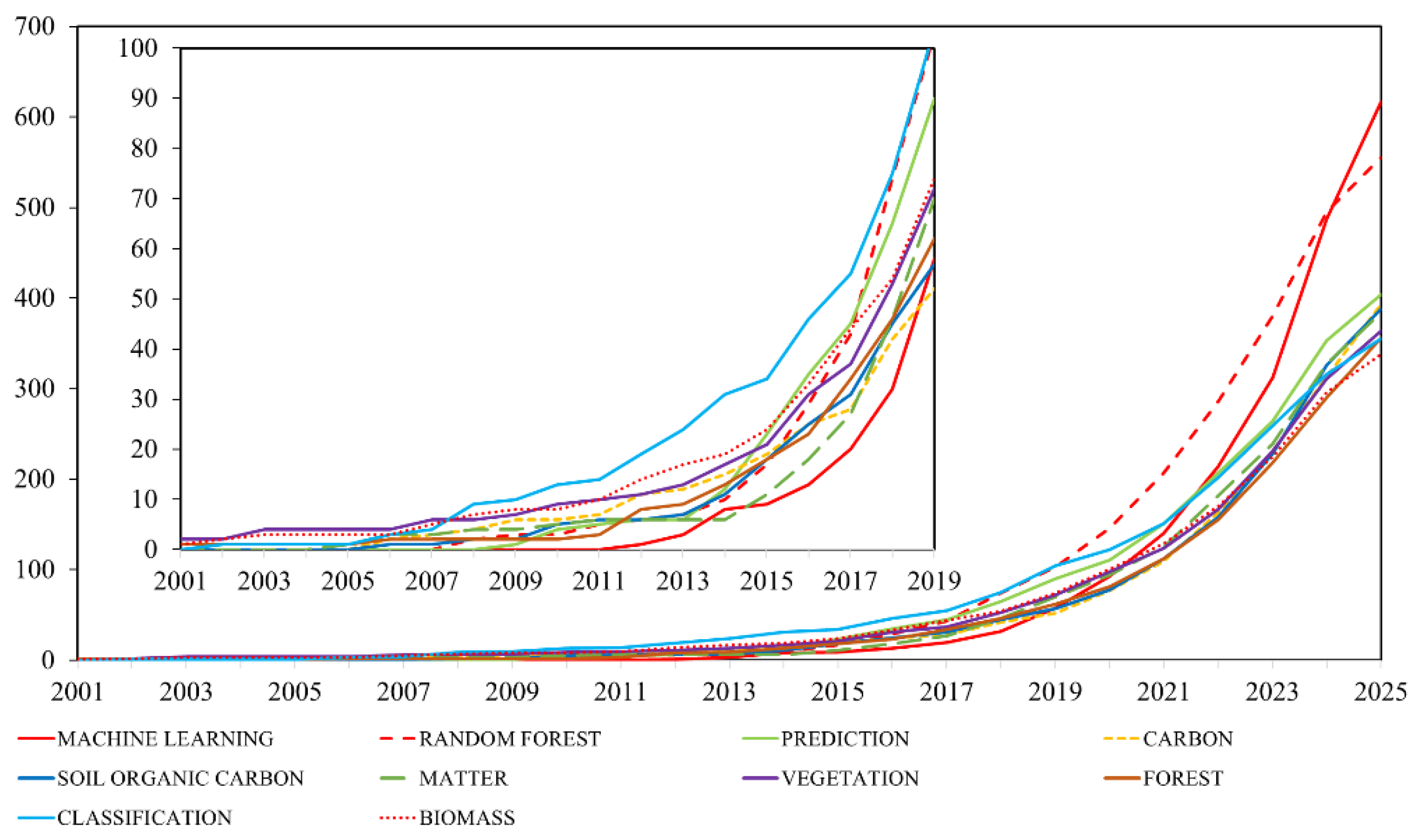

| Evolution Type | Representative Keywords | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Trend Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emerging-Explosive | ML, china, DL, vegetation mapping, microbial necromass, ch4 | 2022–2024 | 2024–2025 | 2024–2025 | Rapid surge after 2022; accelerated integration of AI and natural carbon sinks |

| Rapidly Evolving | RF, prediction, carbon, SOC, classification | 2019–2021 | 2022–2023 | 2024 | Sharp rise in the mid period; became mainstream methods and indicators |

| Mid-Term Active | forest biomass, carbon stocks, boreal forest, variable selection | 2018–2019 | 2020–2021 | 2023–2024 | Gained traction around 2018; consistently maintained research popularity |

| Early Declining | ANN, biomass estimation, pedotransfer functions, radar backscatter, SVR, imaging spectroscopy, glas, water-vapor, tm data, small-footprint lidar, queensland, vegetation structure, jers-1 sar, discrete-return lidar, tree cover | 2008–2017 | 2014–2020 | 2018–2022 | Early-stage methods now experiencing declining attention or marginalization |

| Algorithm Type | Typical Application Tasks | High-Frequency / Representative Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| RF | Soil carbon content estimation, land-use classification, feature importance identification | SOC, digital soil mapping, land-use, classification |

| DL | Semantic segmentation of remote sensing images, forest carbon stock inversion, LiDAR data processing | DL, aboveground biomass, lidar, vegetation, sentinel-2 |

| Regression Models | Soil property modeling, carbon flux prediction, carbon stock trend fitting | regression, carbon stocks, prediction, carbon sequestration |

| SVM/ANN | Early exploration of remote sensing–carbon estimation, nonlinear modeling experiments | SVR, ANN, backscatter |

| Ensemble Modeling Methods | Multi-model ensemble optimization, error propagation control, multi-source data fusion modeling | ensemble learning, uncertainty, variability |

| Development Phase | Representative Methods/Algorithms | Core Research Topics | Dominant Interaction Mechanism | Tech-Problem Paradigm Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Emergence Stage (2001–2010) | ANN, SVM, KNN, and other early statistical learning methods | Vegetation classification, preliminary estimation of soil carbon | Problem-Driven | Methods mostly served as auxiliary tools, relying heavily on expert ecological knowledge for modeling |

| The Initial Growth Stage (2011–2017) | RF、SVR、Ensemble Learning | Spatial interpolation of soil carbon, forest carbon measurement | Data-Driven | Enhanced coupling of remote sensing and field data; AI integrated into high-resolution mapping and modeling |

| The Acceleration Stage (2018–2021) | DL (e.g., CNN), high-dimensional feature learning | Carbon stock prediction using multi-source remote sensing, scenario simulation | Problem + Data | Models began replacing parts of expert-driven processes; AI embedded in mid-level layers of carbon sink modeling |

| The Expansion Stage (2022–2025) | Transformer, GPT, temporal prediction models | Multi-scale carbon flow modeling, zero-shot estimation, cross-domain transfer | Algorithm-Driven | AI transformed from a “tool” to a “cognitive agent,” contributing to paradigm construction and theoretical abstraction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).