4.1. Preliminary Results

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 present some descriptive statistics, namely the mean and standard deviation (Std.Dev.) for both time series.

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 report the results for the countries (which are grouped according to the categories in

Table 1), and

Table 6 reports the results for the world regions. The penultimate column of each table shows the values of the unconditional correlation between GDP and CO

2 emissions per capita. The null hypothesis of unconditional correlation equal to zero was tested (with a t-test using the t-statistics), and the results are displayed in the last column.

As was expected, high-income countries report higher mean GDP (and standard deviation) values, and generally higher mean CO2 emissions. However, it is curious to observe that the Principality of Monaco reports the highest mean GDP value but does not report one of the highest values of mean CO2 emissions. Monaco’s highest mean value of GDP per capita can be explained by its robust financial sector, luxury tourism, and the presence of wealthy residents. Unlike countries with high industrial output, Monaco's economy does not rely on heavy manufacturing or large-scale industrial activities that typically result in significant CO2 emissions. Thus, despite its high economic wealth, Monaco has a low carbon footprint, which may reflect Monaco’s implementation of stringent environmental regulations and sustainable practices. This combination of a service-oriented economy and proactive environmental policies could explain why Monaco enjoys a high GDP per capita without correspondingly high CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, Qatar is the country that reports the highest mean value of CO2 emissions, which can be explained by the extensive oil and gas industry, which is a major contributor to the country's economy. Despite the significant revenues from hydrocarbons, Qatar's wealth distribution, population size and economic structure result in a lower GDP per capita compared to other countries with diversified and technologically advanced economies. Qatar's economic model, which is heavily reliant on fossil fuels, could explain its high CO2 emissions but without a corresponding high GDP per capita.

The countries with the highest levels of CO2 emissions are Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, all of which are countries with large reserves of oil and natural gas (the exploitation of these natural resources being fundamental pillars of their economies) and economies that are heavily dependent on the production and export of hydrocarbons, which can explain their higher values of mean CO2 emissions.

Considering the values of estimated unconditional correlation (between the mean GDP per capita and the mean CO

2 emissions per capita), the relationship between GDP and CO

2 emissions per capita varies significantly between the different groups of countries, according to their stage of economic development. Except for the high-income countries, most of the correlations are positive and statistically significant, meaning that, on average, incomes have led to increased emissions over the 1990–2020 period; this is in line, for example, with the findings of Narayan et al. [

19].

For the high-income countries, 24 unconditional correlations (of the 47 possible) are negative and statistically significant, which could mean these countries passed the inflection point of the EKC. These results seem to be not only in agreement with the EKC hypothesis but also with the energetic transition theory, which suggests that as countries develop, they pass from traditional energy sources to renewable and clean energy sources. From high-income countries to low-income countries (as the income levels decline), the percentage of positive and statistically significant correlations increases. This preliminary evidence seems to agree with the EKC hypothesis, i.e., countries of high-income levels seem to have reached a point where their economic growth is not strongly associated with an increase in CO2 emissions.

The evidence found for the upper-middle and lower middle-income countries could be a sign that these countries are still in the ascending phase of the EKC, where economic growth results in higher levels of CO2 emissions.

Concerning low-income countries, although this category has the smallest number of countries, 77.78% of these countries display positive and statistically significant unconditional correlations, suggesting that even in the early stages of development, there exists a clear relationship between economic growth and CO2 emissions.

Considering the world regions, North America, post-demographic dividend regions (mostly high-income countries where fertility has transitioned below replacement levels), and high-income regions, are the ones that report the highest level of mean GDP per capita and simultaneously the highest mean values of CO

2 emissions. The Euro area follows these regions in terms of mean GDP per capita but not in terms of mean CO

2 emissions, which the OECD members follow. This could mean that countries outside the Euro area are the major ones responsible for CO

2 emissions among the OECD members (as only 19 of the 38 OECD members are from the Euro area). This could also be a sign that the Euro area could have implemented more effective policies and technologies in terms of the reduction of CO

2 emissions than other members of the OECD. Thus, the Euro area could be viewed as an example of how high levels of development can coexist with lower levels of emissions through strict environmental policies. Regarding the OECD countries, our results do not seem to agree with the EKC hypothesis, which contradicts the findings of Galeotti et al. [

38], who found evidence for the EKC. This could be a sign that OECD countries may need to address the global nature of environmental issues.

The relationship between GDP and CO2 emissions per capita also varies between the different world regions, with most of the correlations being positive and statistically significant, meaning that, on average, incomes have led to increased emissions over the 1990–2020 period. The world, as a whole, displays a positive and statistically significant correlation between the analyzed variables, meaning that global economic growth and CO2 emissions are still strongly associated, which could mean that the world as a whole is still at an early or intermediate stage on the EKC.

Globally, 40 out of the 158 countries (25.3%) and 11 of the 44 world regions (25%) display a negative and statistically significant unconditional correlation between GDP and CO

2 emissions per capita. This percentage is higher than the one found by Narayan et al. [

19], which, considering the period 1960–2008, found 20 countries (of 181 analyzed) with this pattern. These results indicate that, as GDP per capita increases, CO

2 emissions decrease, reflecting a significant change in the traditional relationship between economic growth and CO

2 emissions, which could mean that economic growth is no longer necessarily associated with higher CO

2 emissions in many countries. At the same time, and considering the perspective of the EKC, this could mean that more countries have reached the inflection point or are in the process of reaching it. However, this transition is not yet universal, which is confirmed by the different results for the world regions.

4.2. Cross-Correlation Coefficient Analysis

The correlations obtained in the previous sub-section are static and do not allow us any insight into how these relationships will behave in the future. Thus, to get some insights in this respect and evaluate how GDP per capita is negatively or positively correlated with CO

2 emissions over the past (lags), and in the future (leads), the CCC proposed by Narayan et al. [

19] was estimated, and the results are displayed in

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10 for countries (which are grouped according to the categories in

Table 1) and in

Table 11 for world regions.

The third and fifth columns of each table report the sum of the cross-correlation coefficients over the past 20 lags and the future 20 leads of CO

2 emissions, respectively. The fourth and sixth columns report the mean values of the same lags and leads, respectively. If past/future values of CO

2 emissions per capita, i.e., lags/leads, are positively/negatively correlated with the current values of GDP per capita, there is evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship (identified with an “X” in the seventh column of

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11). This means that the CO

2 emissions increased with GDP in the past, but will decline in the future, supporting the EKC hypothesis. However, in addition to this scenario, another three can be observed: (i) negative cross-correlation between both past and future values of CO

2 emissions (lags and leads) and the current level of GDP per capita (identified with an “X” in the eighth column of

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11), meaning in this case, increasing GDP per capita has led in the past, and could lead in the future, to a reduction in carbon emissions, which partially supports the EKC hypothesis; (ii) past/future values of CO

2 emissions per capita, i.e., lags/leads, could be negatively/positively correlated with the current values of GDP per capita, meaning that, although in the past an increase in the GDP level led to a reduction of CO

2 emissions per capita, in the future it will not happen (identified with an “X” in the ninth column of

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11); (iii) positive cross-correlation between both past and future values of CO

2 emissions (lags and leads) and the current level of GDP per capita, meaning in this case, increasing GDP per capita has led in the past, and will probably lead in the future, to an increase in carbon emissions (identified with an “X” in the tenth column of

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11).

To verify whether our results are consistent, we begin our analysis by verifying whether the sign of the sum of the CCC for the lags and leads and their averages are similar, i.e., whether they are both (sum and average) negative or positive. As displayed in

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11, they are. Thus, we can consider as valid the values of the averages of the CCC in our analysis.

Considering the results of the average CCC (that can soften outliers and provide a clearer view of the general pattern), displayed in

Table 7, for the 47 countries categorized as high-income countries, only three (namely, The Bahamas, Monaco, and Poland) show signs of an inverted U-shaped relationship between the current levels of GDP per capita and past and future values of CO

2 emissions. On the other hand, Czechia, Germany, Hong Kong, Luxembourg, Singapore, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Arab Emirates (a total of nine countries), reveal negative mean values of the CCC over the lags and leads, which may be a sign that for these countries the CO

2 decreased in the past and will continue to decrease in the future, with the increase in GDP per capita. These results partially agree with the EKC hypothesis and corroborate the results of Narayan et al. [

19] in the cases of Czechia, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Sweden and Switzerland. For the majority of high-income countries (26 countries), we find a negative cross-correlation for the lags and a positive for the leads, which could mean that although, in the past, an increase in GDP level led to a reduction of CO

2 emissions per capita, it will not happen in the future. The remaining countries of this panel (precisely, nine countries) display positive cross-correlation for the lags and leads, meaning that increasing GDP per capita has led in the past, and will probably lead in the future, to an increase in carbon emissions.

Considering the 44 upper middle-income countries, the results suggest that 10 countries (namely, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Botswana, Colombia, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Romania, the Russian Federation and Suriname) agree with the EKC hypothesis, although Bulgaria is only in partial agreement. For the remaining countries in this panel, 17 reveal negative/positive cross-correlations for the lags/leads and 16 positive cross-correlations for the lags and leads.

For the lower middle-income countries, 12 (namely, Algeria, Belize, Bolivia, Cameron, the Congo Republic, Eswatini, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Tanzania, Vanuatu, Zambia and Zimbabwe) show evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship, and three (Nigeria, Ukraine and Uzbekistan) are only in partial agreement with the EKC hypothesis, displaying negative average CCC for the leads. For the remaining countries (34), the results do not provide any support for the EKC hypothesis.

For the panel of 18 lower-income countries, four (namely, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Guinea-Bissau, and Malawi) show an inverted U-shaped relationship. For the remaining 14 countries, two (Togo and the Yemen Republic) reveal negative/positive cross-correlations for the lags/leads and 12 positive cross-correlations for the lags/leads.

If we compare our results with those of Shahbaz et al. [

32], who explored the nexus between globalization and energy demand for 86 high, middle, and low-income countries over the period 1970–2015, we can highlight that: (i) some countries have changed, in relation to the income level criteria, their category/classification; (ii) several countries of different income levels (but mostly from high-income levels) have maintained or improved the relationship between the mean GDP per capita and the mean CO

2 emissions for the lags, but have displayed a similar pattern for the leads. However, there are four countries, namely Denmark, the United States, Gabon and the Philippines, which, although revealing a similar pattern for the lags, display a positive (sum and average) CCC for the leads [while in the study of Shahbaz et al. [

32] they displayed a negative CCC (sum and average), indicating an undesirable inversion on their pathway to sustainable development; (iii) on the other hand, Botswana, Algeria, Bolivia and the Congo Republic, although revealing a similar pattern for the lags, display a negative (sum and average) CCC for the leads (while in the study of Shahbaz et al. [

32] they displayed a positive CCC (sum and average)), also indicating an inversion on their pathway to sustainable development. However, for these countries, it is a desirable one, since a reduction in CO

2 emissions is expected with increasing GDP; (iv) for Albania, Ghana and Sudan, increasing GDP has led in the past, and will lead in the future, to rising CO

2 emissions, entirely contradicting the findings of Shahbaz et al. [

32]; (v) on the other hand, for Sweden and Nigeria, increasing GDP has led in the past, and will lead in the future, to decreasing CO

2 emissions, also entirely contradicting the findings of Shahbaz et al. [

32].

Considering the results of the average CCC displayed in

Table 11, for the 44 regions, only three (namely, Europe & Central Asia (excluding high-income), Europe & Central Asia (IDA & IBRD countries) and Pre-demographic dividend) show signs of an inverted U-shaped relationship between the current levels of GDP per capita and past and future values of CO

2 emissions. This evidence suggests that these regions are managing to balance economic growth with effective environmental policies. On the other hand, Central Europe and the Baltics, Europe & Central Asia, fragile and conflict-affected situations, IDA blends, and low-income regions, reveal negative mean values of the CCC over the lags and leads, partially supporting the EKC hypothesis. For fragile and low-income regions, it may be a positive sign that economic growth is not being achieved at the expense of increasing carbon emissions, but these results may also reflect economic challenges that limit growth. For 13 regions, the results reveal negative cross-correlation for the lags and positive ones for the leads, which could mean that although in the past an increase in GDP level has led to a reduction in CO

2 emissions per capita, in the future, this will not happen. These results may indicate that these regions may face the risk of reversing the environmental gains they have achieved in the past, which may be due to a possible lack of continuity in environmental policies or new economic challenges. Thus, for these regions, there is an urgent need to implement or reinforce environmental policies that ensure that future economic growth does not increase CO

2 emissions. Finally, the majority of regions (23) display positive cross-correlation for the lags and leads, meaning that increasing GDP per capita has led in the past, and probably will lead in the future, to an increase in carbon emissions. In these regions, the growth of per capita GDP has historically led, and will probably continue to lead, to a rise in CO

2 emissions, which may indicate that these economies are at an early stage of the EKC. It is, therefore, essential that these regions adopt strict environmental policies and promote clean technologies to reverse this trend.

Table 12 summarizes all the above results for a brief and easier analysis. The first column ((+)/(-)) identifies the number and percentage of countries and regions that, considering the average CCC for the 20 lags and 20 leads, reveal a pattern in agreement with the EKC hypothesis. The second column identifies the number and percentage of countries and regions that reveal a pattern in partial agreement with the EKC hypothesis. The last two columns show the number and percentage of countries and regions for which it is expected that, in the future, there will be an increase in CO

2 emissions with GDP per capita. It is interesting to note that high-income countries are the ones that are in least agreement with the EKC hypothesis. It was expected that these countries, being economically well-established and having the necessary infrastructure and resources to maintain and promote a cleaner environment, would be in greater agreement with the EKC hypothesis, but this is not verified.

Generally, the results suggest that 18.35% of the countries (29 out of 158) and 6.82% of the world regions (three out of 44) support the EKC hypothesis. Comparing our results with the ones of Narayan et al. [

19], which found 12% with clear evidence supporting the EKC hypothesis), the percentage of countries in agreement with this hypothesis has increased. Considering the countries/regions that are in partial agreement, i.e., the ones in which it is expected that an increase in the GDP will be accompanied by a reduction in CO

2 emissions in the future, our results reveal that only 8.23% of countries, and 11.36% of world regions, seem to be aligned with this pattern. If we compare this result with the one of Narayan et al. [

19], which found that 27% of the countries partially agree with the EKC hypothesis, our results are not very encouraging regarding CO

2 reductions in the future. According to our results, it is expected that 73.42% of countries and 81.82% of world regions will see an increase in CO

2 emissions with an increase in GDP.

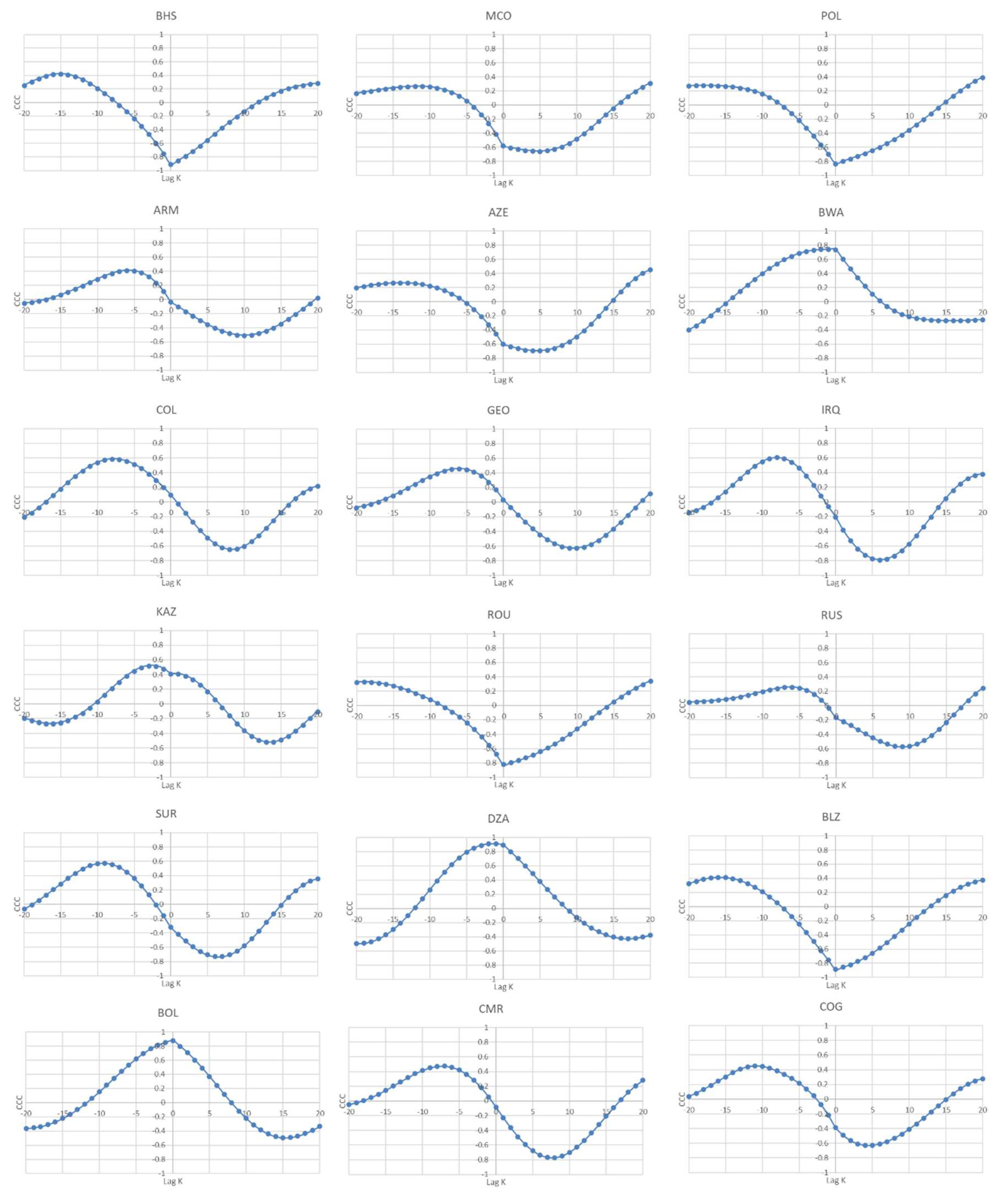

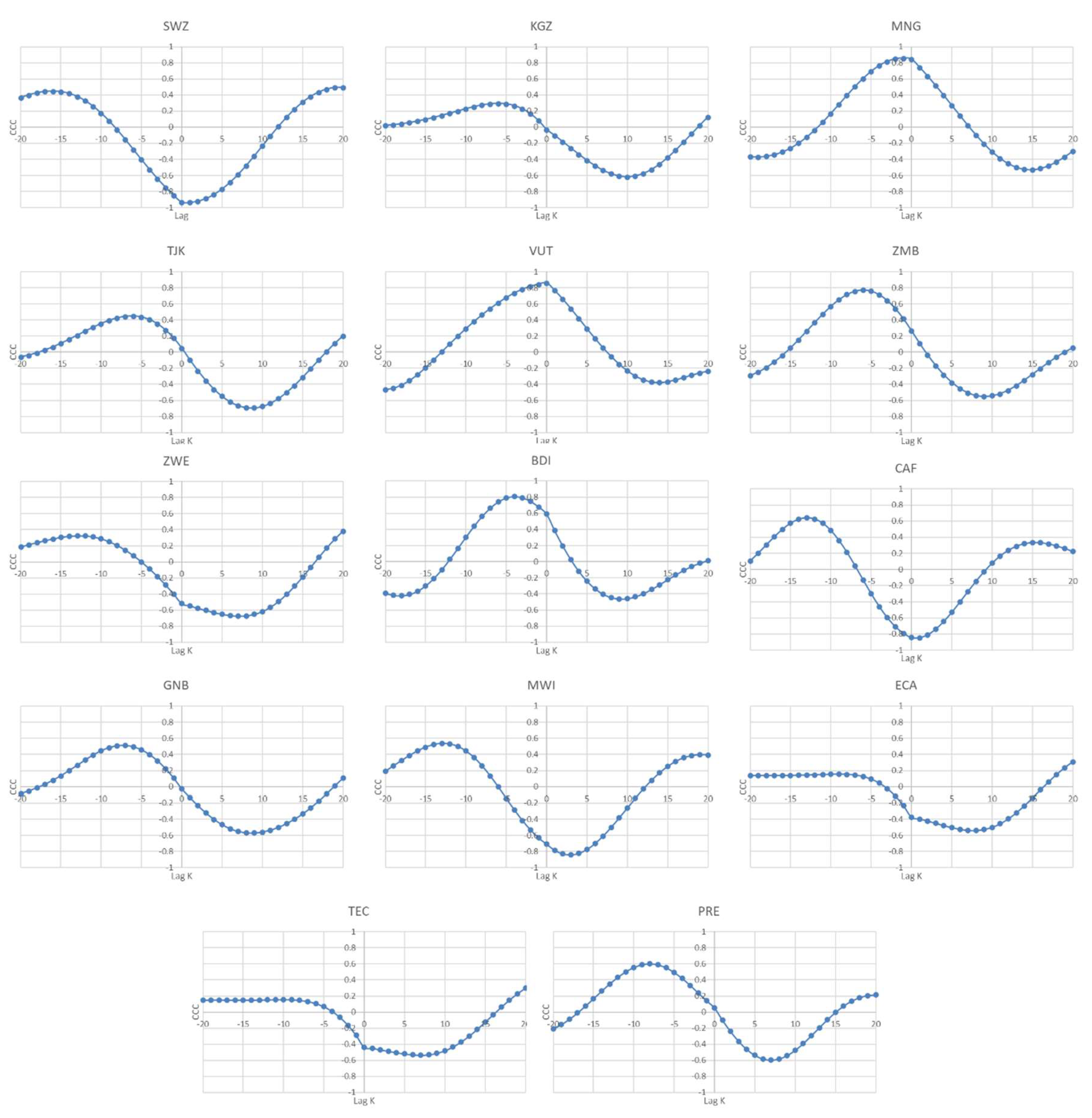

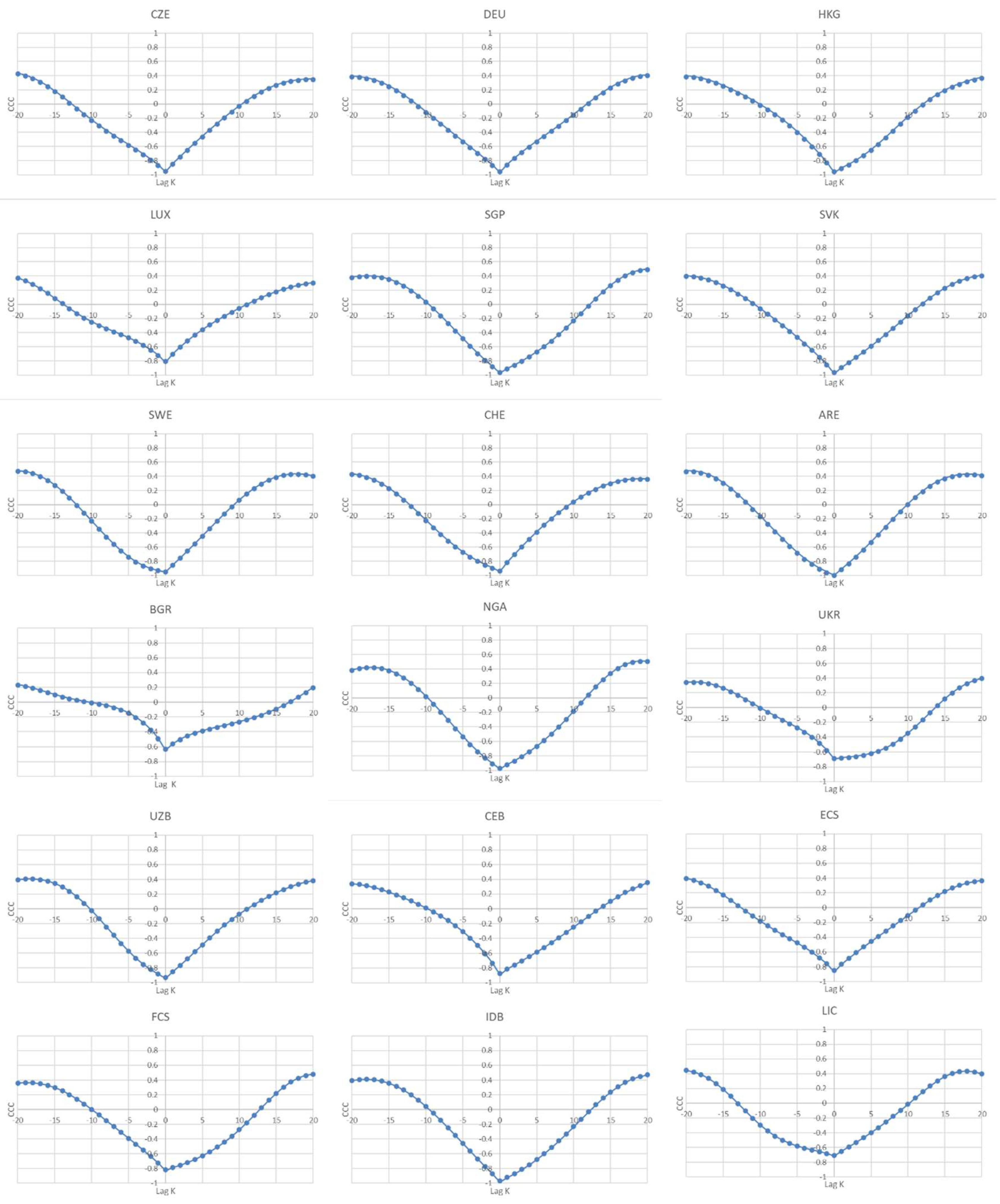

For a more accurate analysis of which countries and regions agree with the EKC hypothesis using the CCC proposed by Narayan et al. [

19], it is crucial to consider both the average values of the lags and leads as well as the detailed graphical representation of these coefficients over the 20 lags and 20 leads. Although the average values of the lags and leads provide a simplified and aggregated view of the relationship between GDP and CO

2 emissions, we must not forget some possible limitations related to this analysis. Using averages can mask significant variations and trends within the individual lag and lead periods. Furthermore, a graphical presentation of the CCC for each of the 20 lags and leads allows a more nuanced and detailed analysis. The graphs will enable us to highlight the specific periods where the relationship changes, providing relevant information about the temporal dynamics that the average values cannot capture. For instance, a graph might show that the correlation is positive for the initial few lags/leads but starts to decline and eventually turns negative as we approach the 20th lag/lead. This transition is critical in understanding how economic activities can influence environmental outcomes over time and supports a more robust interpretation of whether a country/region agrees with the EKC hypothesis. Moreover, graphical analysis can help us identify any anomalies or outliers that could significantly affect the average values. Visualizing the CCC over time can also illustrate the consistency or volatility of the relationship between the analyzed variables, providing context essential for interpreting the results accurately. This dual approach ensures that we capture the full complexity of the relationship between the analyzed variables, allowing more accurate conclusions about agreement of countries/regions with the EKC hypothesis. For these reasons,

Figure 1 displays the plots for the countries/regions whose behavior seems to agree with the EKC hypothesis (with reference to the positive sign (+) for the average CCC for the lags, and the negative (-) one for the average CCC for the leads), and

Figure 2 displays the graphs for the countries/regions which seem to be in partial agreement with the EKC hypothesis, i.e., the ones that display negative sign (-) for the average CCC for the leads. We plotted the graphs for the 20 lags and leads for all the countries and regions (a total of 202 graphs). However, due to space constraints, it is not possible to present all of them here, but they are all available upon request.