1. Introduction

Energy generated from traditional resources such as fossil fuels causes air pollution in the short term. In the long run, it leads to an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide, thereby triggering global warming [

1]. Therefore, vigorously developing renewable energy and clean energy is one of the crucial approaches and goals for promoting the current energy transition and achieving global carbon neutrality [

2]. In recent years, hydrogen has gradually attracted attention due to its unique advantages of zero carbon emissions, storability, transportability, and multi-energy conversion capabilities [

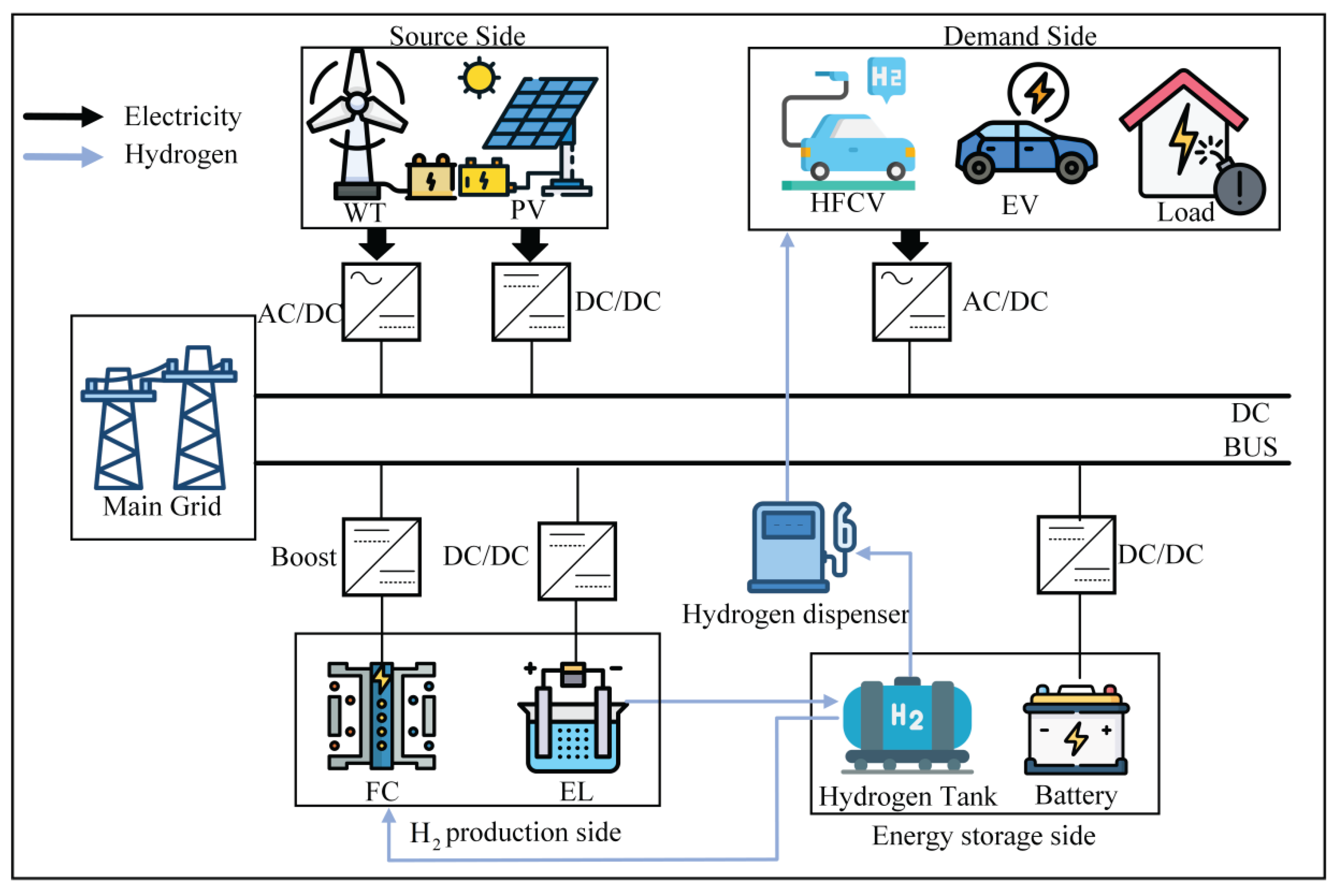

3].The IHES, consisting of fuel cell(FC), hydrogen storage tank(HST), electrolyzer(EL), and supplementary batteries, can realize the functions of hydrogen production and storage, which is conducive to achieving zero emissions in the energy system. The energy supply of the IHES is highly dependent on distributed energy sources such as PV and wind power. However, the output of such energy sources is significantly affected by natural conditions, exhibiting characteristics of intermittency, volatility, and randomness [

4].In addition, electric loads are also influenced by factors such as users’ living habits and seasonal climate, featuring large intraday peak-valley differences and sudden demand surges [

5]. On the other hand, the deployment of new technologies such as electric vehicles(EVs) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicle(HFCVs) introduces greater complexity and uncertainty to load forecasting [

6].The superposition of prediction deviations on both the energy supply and demand sides makes it difficult to achieve temporal matching in the multi-energy conversion chain of the IHES. Aspects such as the hydrogen production power of EL and the charging-discharging strategies of batteries all rely on accurate supply and demand forecasting schemes. Consequently, the decline in forecasting accuracy will make it difficult for the IHES to meet the preset economic dispatch targets [

7].

Scholars have conducted extensive research on various issues in IHES; in terms of new energy forecasting, Emrani et al. [

8] constructed a wind and PV power generation forecasting model based on on-site meteorological data, and by acquiring meteorological data, they predicted PV output power using a coupled model of solar irradiance and temperature, forecasted wind power output based on local wind speed piecewise functions and high wind speed characteristics, and verified the critical role of accurate forecasting in improving the economy and reliability of energy systems. Mellit et al. [

9] took a specific PV system as the research object, investigated the forecasting performance of deep learning algorithms with different time steps and frameworks, validated the performance, training efficiency, and accuracy of the single Deep Learning Neural Network (DLNN) model, and demonstrated the application value of the single DLNN model in PV and wind power forecasting. Mirza et al. [

10] proposed a hybrid deep learning model integrating ResNet, Inception modules, and bidirectional weighted LSTM/GRU for short-term and medium-term forecasting of wind and PV power based on wind and PV data from the State Grid Corporation of China and wind farm data from South Africa, and verified its accuracy and stability in wind and PV power forecasting. Sarmas et al. [

11] constructed four basic LSTM models, used Support Vector Regression (SVR) to build a meta-learner that dynamically fuses the forecasting results of the basic models to adapt to the characteristics of different PV systems, and validated the model’s accuracy in PV power forecasting using power generation data from a PV plant in Portugal. After confirming that accurate renewable energy forecasting is a prerequisite for ensuring the efficient operation of IHES, the academic community has also carried out extensive basic and applied research on the structural design of the system itself to provide theoretical and experimental support for multi-energy conversion and supply-demand balance: Li et al. [

12], in their research on IHES for net-zero energy buildings, configured a hydrogen energy subsystem consisting of an EL, a high-pressure HST, FC, and meanwhile realized a power coordination scheme using max-min game theory to achieve the goal of zero-carbon emission buildings; Shao et al. [

13] proposed a structural framework for IHES that incorporates a hydrogen transportation subsystem, where hydrogen production stations powered by renewable energy produce and compress hydrogen, the hydrogen is then transported by trailers and finally stored in hydrogen refueling stations to supply hydrogen loads, filling the gap in the transportation aspect of IHES; Du et al. [

14] proposed an off-grid-grid-connected hybrid design for IHES, which integrates a cooling-waste heat recovery module and auxiliary equipment, recovers waste heat generated during the operation of PEMEL and PEMFC through heat exchange plates, and optimizes the operating status of equipment via multiphase flow and thermal balance modeling to effectively reduce the frequency of PEMEL start-ups and shutdowns, thus enabling more efficient operational coordination of the hydrogen-electric coupling system. The aforementioned studies have explored IHES under different application scenarios from various perspectives, but few studies have considered the efficiency decline of EL and FC caused by their lifespan reduction—which in turn leads to decreased hydrogen production by EL and thus affects the operation of IHES [

15]; additionally, the electric load exhibits significant peak-valley differences due to the randomness of EVs and HFCVs, making system dispatch optimization more challenging.

On the other hand, on the load side of IHES, with the popularization of new energy vehicles(NEVs), the strong uncertainties exist in users’ choices of charging/hydrogen refueling time and variations in travel routes, resulting in the load side exhibiting characteristics of large peak-valley differences and high volatility. Among existing studies on NEVs, for instance, Hussain et al. [

16] proposed a local demand management model that integrates vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) services with the welfare maximization-soft actor-critic (SAC) deep reinforcement learning approach. By means of dynamic pricing and charging-discharging optimization, and on the basis of considering the differences in EVs owners’ sensitivity to remaining battery capacity, battery degradation, and incentive prices, this model effectively alleviates the problem of distribution network transformer overload under high EV penetration rates, and realizes the coordinated optimization of owners’ welfare and power grid security. Eghbali et al. [

17] put forward a scenario-based stochastic model; by fitting probability distribution functions for three types of uncertain parameters of NEVs, namely arrival time, departure time, and driving distance, and simultaneously combining with demand response programs, this model achieves the optimal dispatch of IHESs containing multiple energy sources and multiple ESS under the objective of minimizing the total system cost. Habib et al. [

18] proposed a three-stage stochastic optimization structure, which generates parameter scenarios based on the normal distribution to address the uncertainty of NEVs; by combining vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology, demand response, and energy storage, this structure realizes the optimal operation of a distribution system with four IHESs, thereby reducing costs and improving system performance. Wu et al. [

19] proposed a two-layer model predictive control strategy, which samples the EV connection time and initial SOC, incorporates uncertainty sampling for extreme scenarios, and combines with EV arrival feedback to handle the uncertainty of EVs. This strategy optimizes the charging and discharging processes to reduce prediction errors and minimize the power exchange between the IHES and the main grid.

Given the aforementioned characteristics of volatility and randomness in source-load forecasting, researchers have conducted extensive studies on the dispatch optimization of IHES to improve the economic efficiency and stability of IHES. For example, Dong et al. [

20] focused on the dispatch optimization of IHES, with hydrogen-water hybrid energy storage as the core. They adopted scenario-based algorithms to handle uncertainties and mixed-integer programming to clarify the relationships among multiple energy sources; this deterministic dispatch approach effectively reduced operating costs and increased the utilization rate of renewable energy. Zheng et al. [

21] addressed the dispatch of biomass-integrated IHES, using Monte Carlo simulation to handle source-load uncertainties such as electric load and photovoltaic output. Combined with load shifting algorithm optimization, and under the consideration of time-of-use electricity prices and demand response, their work effectively mitigated the impact of source-load uncertainties on dispatch. For the hydrogen-electric hybrid energy storage system in IHESs with wind and photovoltaic generation, Li et al. [

22] constructed a distributionally ambiguous set based on the Wasserstein distance, and applied distributed robust optimization to handle the source-load uncertainties of wind and photovoltaic output. They established a capacity optimization model targeting system economy and reliability, realizing the coordinated configuration of hydrogen and electric energy storage. Dong et al. [

23] focused on the dispatch optimization of isolated hydrogen IHES.First, they used a bidirectional LSTM-CNN model to predict wind and photovoltaic output as well as load, thereby reducing source-load forecasting errors; then, they combined Monte Carlo simulation to generate stochastic scenarios for quantifying source-load uncertainties; finally, they applied deep reinforcement learning to solve the stochastic optimization dispatch problem involving energy storage capacity degradation, achieving the minimization of the IHES life-cycle cost. For hybrid IHES with green hydrogen production, Kim et al. [

24] constructed a multi-period, multi-time-scale stochastic optimization model. They used Markov decision processes combined with deep Q-networks to handle source-load uncertainties, and simultaneously employed Monte Carlo simulation to generate stochastic scenarios of wind and photovoltaic output and load, realizing the coordinated optimization of capacity investment and energy management. Wu et al. [

25] targeted IHES with hydrogen fuel cell stations, adopting a data-driven chance-constrained approach to handle the source-load uncertainties of wind and photovoltaic output as well as electric-hydrogen load, while using distributed robust optimization to address electricity price uncertainties. Through converting the problem into a mixed-integer linear programming via an affine strategy, they achieved system dispatch optimization. Based on the above studies, it can be concluded that existing works have effectively handled source-load uncertainties through various methods such as scenario-based algorithms, Monte Carlo simulation, and distributed robust optimization, providing technical support for the dispatch optimization of IHES [

26,

27]. However, most of these studies take fixed time-of-use electricity prices or static electricity prices as constraints, and have not fully explored the core value of dynamic electricity price regulation in addressing source-load fluctuations and optimizing dispatch strategies [

28].

Compared with traditional IHES based on EL/HST/FC, research considering HFCVs and hydrogen refueling stations remains relatively limited. References [

13,

18,

25] have discussed and explored this topic, but they do not account for the lifespan impact of two critical components: PEMEL and PEMFC. Furthermore, in most studies, the randomness of NEVs and their characteristic of significant peak-valley differences are often overlooked, which may lead to misjudgments regarding the hydrogen production capacity of PEMEL and the hydrogen absorption capacity of new energy sources. In addition, electricity prices—an important means of regulating demand response—are usually neglected. Therefore, this paper proposes a day-ahead dispatch optimization scheme for IHES that considers the impact of electricity prices on demand response. This scheme incorporates the lifespan-efficiency effects of PEMFC and PEMEL, and predicts the load side based on the probability density function of vehicle owners’ behaviors. To summarize, the contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) A lifespan-efficiency model for PEMFC and PEMEL is established, which accounts for the impact of PEMFC and PEMEL lifespans on efficiency. Additionally, lifespan degradation models for PEMFC and PEMEL under different operating conditions are developed to enhance the accuracy and reliability of hydrogen prediction in IHES. (2) A load forecasting model for NEVs is constructed. Based on the probability density function of vehicle owners’ behaviors, Monte Carlo simulation is used to predict daily driving mileage, charging start time, and required electricity demand of NEVs, and finally load curves on the load side under different scenarios are obtained. (3) A dynamic pricing strategy considering demand response is proposed. First, dynamic balance equations for the power supply side and load side are established; the system is then divided into several different operating states based on the energy imbalance between the power supply side and load side. Subsystems are weighted and combined using fuzzy weights, and linear matrix inequality (LMI) equations are applied to enable the system to meet preset performance requirements.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized as follows:

Section 2 presents detailed mathematical models;

Section 3 introduces the electricity pricing strategy and the algorithm for mathematical constraints; case studies are illustrated in

Section 4; and finally, conclusions are given in

Section 5.

Figure 1.

System Architecture Diagram.

Figure 1.

System Architecture Diagram.

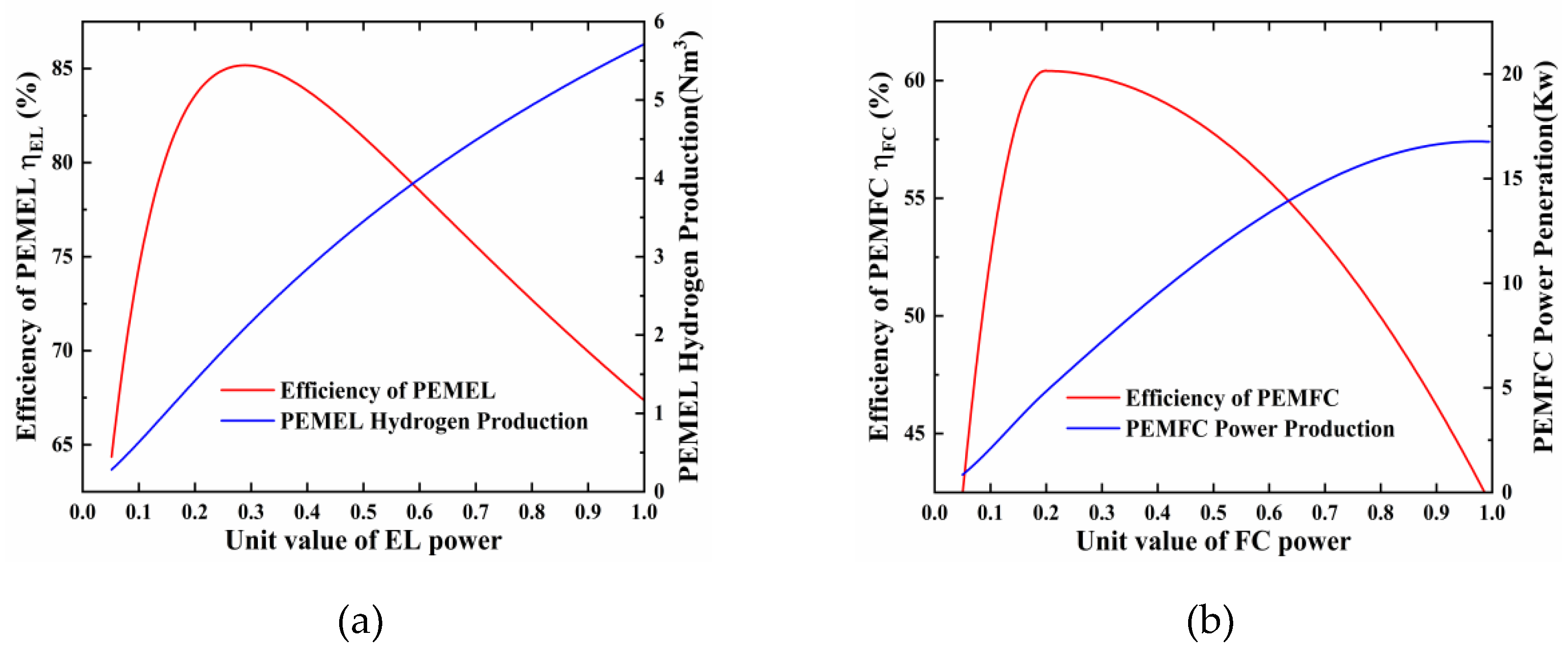

Figure 2.

Efficiency-Power Curves of PEMEL and PEMFC (a) Power-efficiency curve of the PEMEL (b) Power-efficiency curve of the PEMFC.

Figure 2.

Efficiency-Power Curves of PEMEL and PEMFC (a) Power-efficiency curve of the PEMEL (b) Power-efficiency curve of the PEMFC.

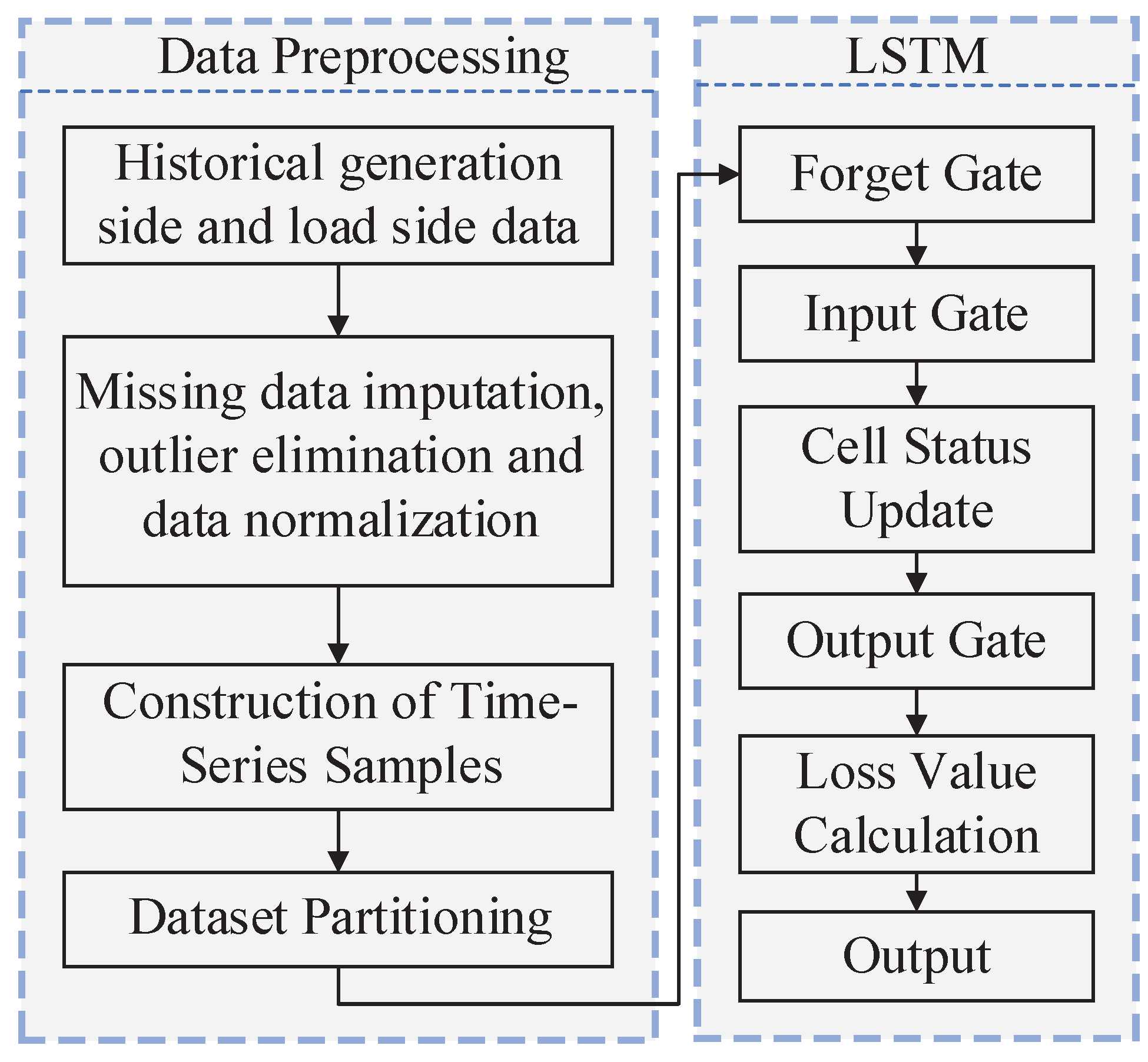

Figure 3.

Flowchart of LSTM-Based Source-Load Side Prediction.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of LSTM-Based Source-Load Side Prediction.

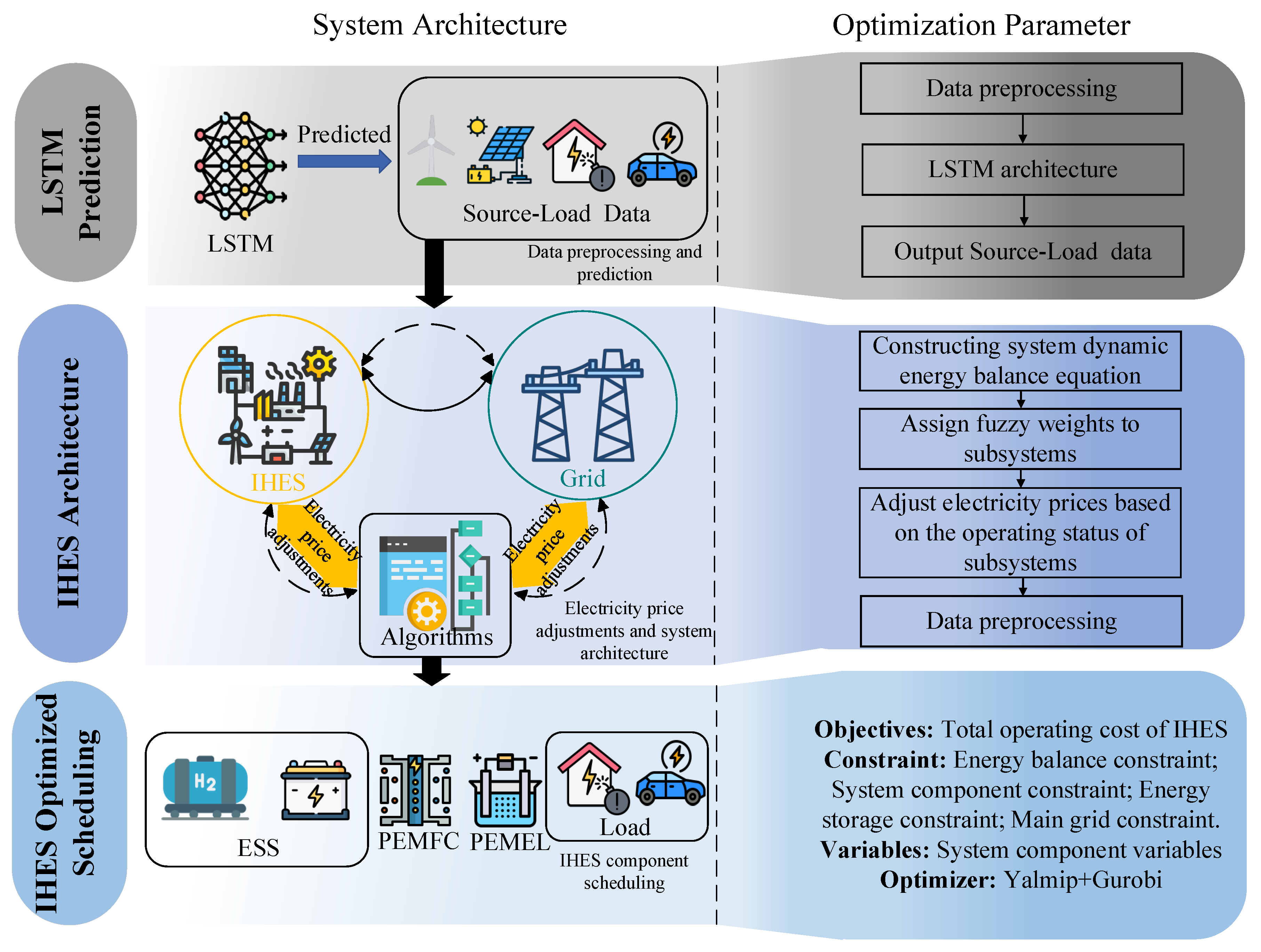

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the Algorithm.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the Algorithm.

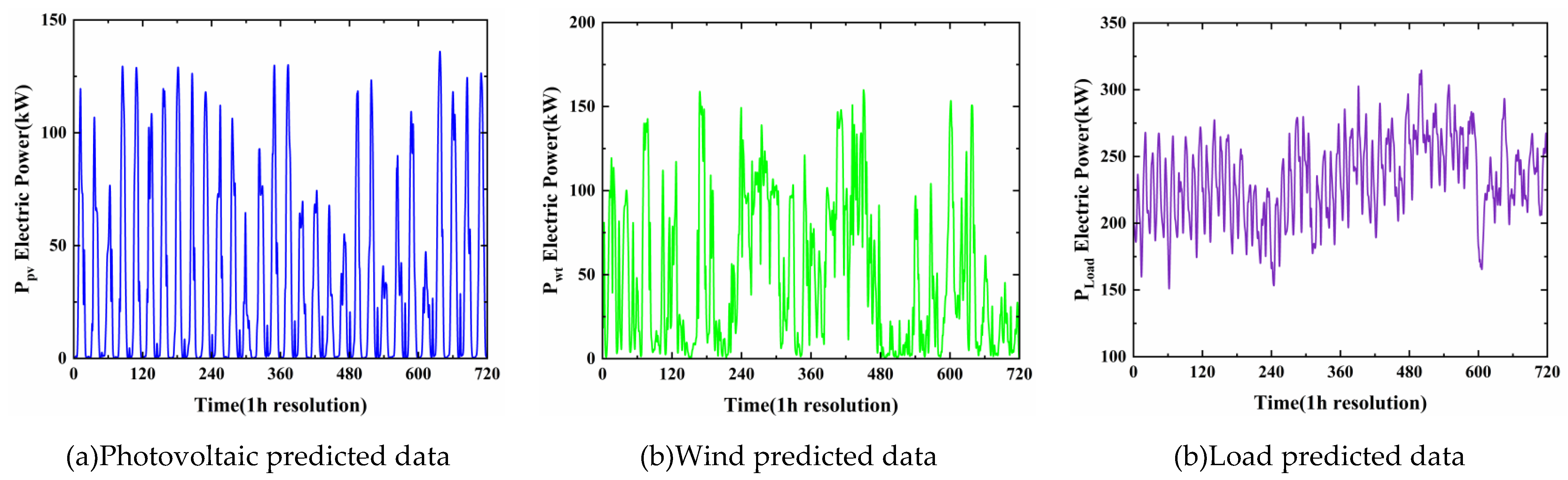

Figure 5.

Monthly predicted data of photovoltaic power generation, wind power generation, and load (a) Photovoltaic predicted data (b) Wind predicted data (c) Load predicted data.

Figure 5.

Monthly predicted data of photovoltaic power generation, wind power generation, and load (a) Photovoltaic predicted data (b) Wind predicted data (c) Load predicted data.

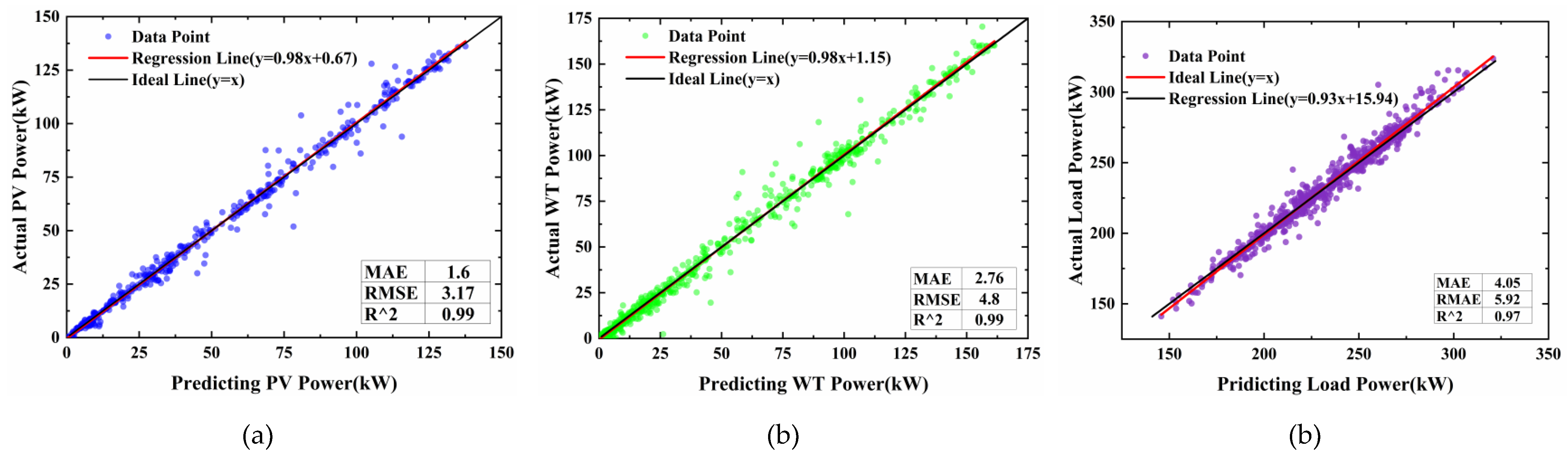

Figure 6.

Monthly predicted data error comparison of photovoltaic power generation, wind power generation and load (a) Photovoltaic error comparison (b) Wind error comparison (c) Load error comparison.

Figure 6.

Monthly predicted data error comparison of photovoltaic power generation, wind power generation and load (a) Photovoltaic error comparison (b) Wind error comparison (c) Load error comparison.

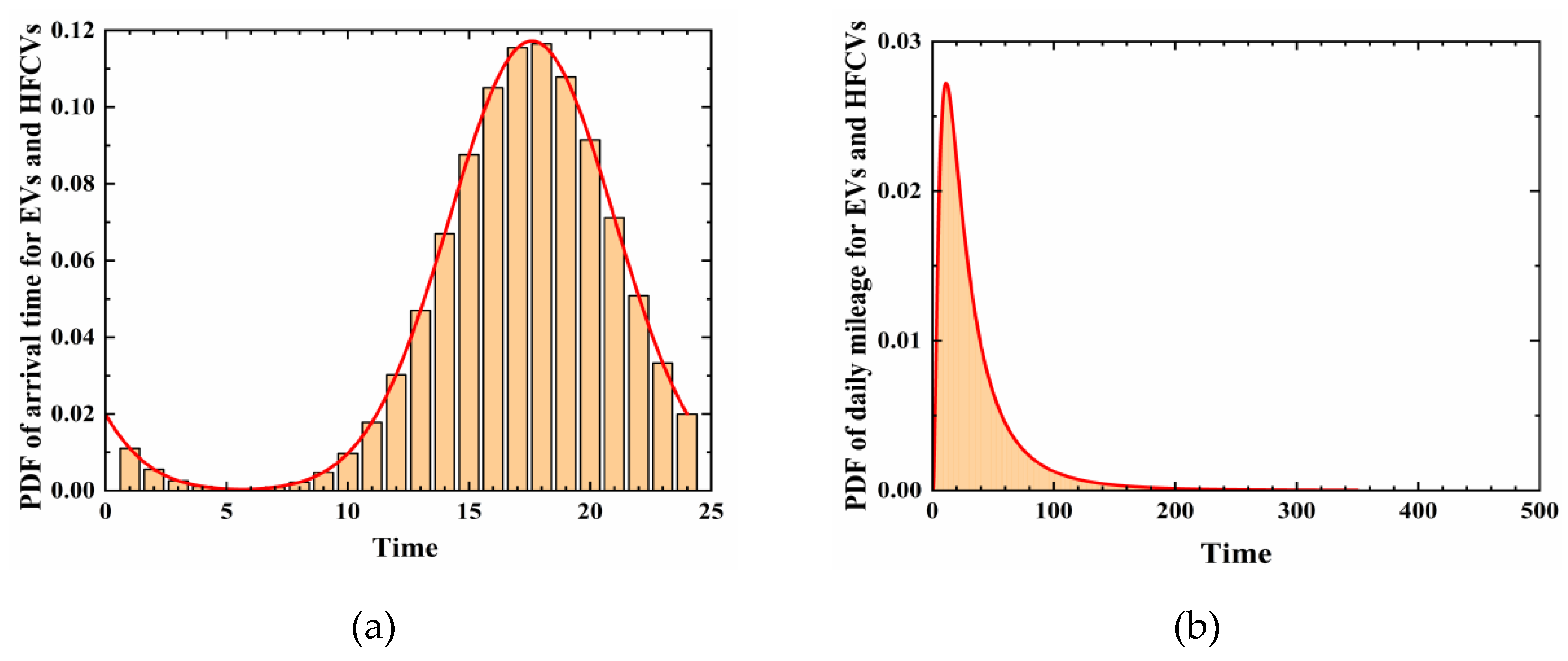

Figure 7.

PDF of Vehicle Owners’ Probabilistic Behaviors (a) PDF of arrival time for EVs and HFCVs (b) PDF of daily mileage for EVs and HFCVs.

Figure 7.

PDF of Vehicle Owners’ Probabilistic Behaviors (a) PDF of arrival time for EVs and HFCVs (b) PDF of daily mileage for EVs and HFCVs.

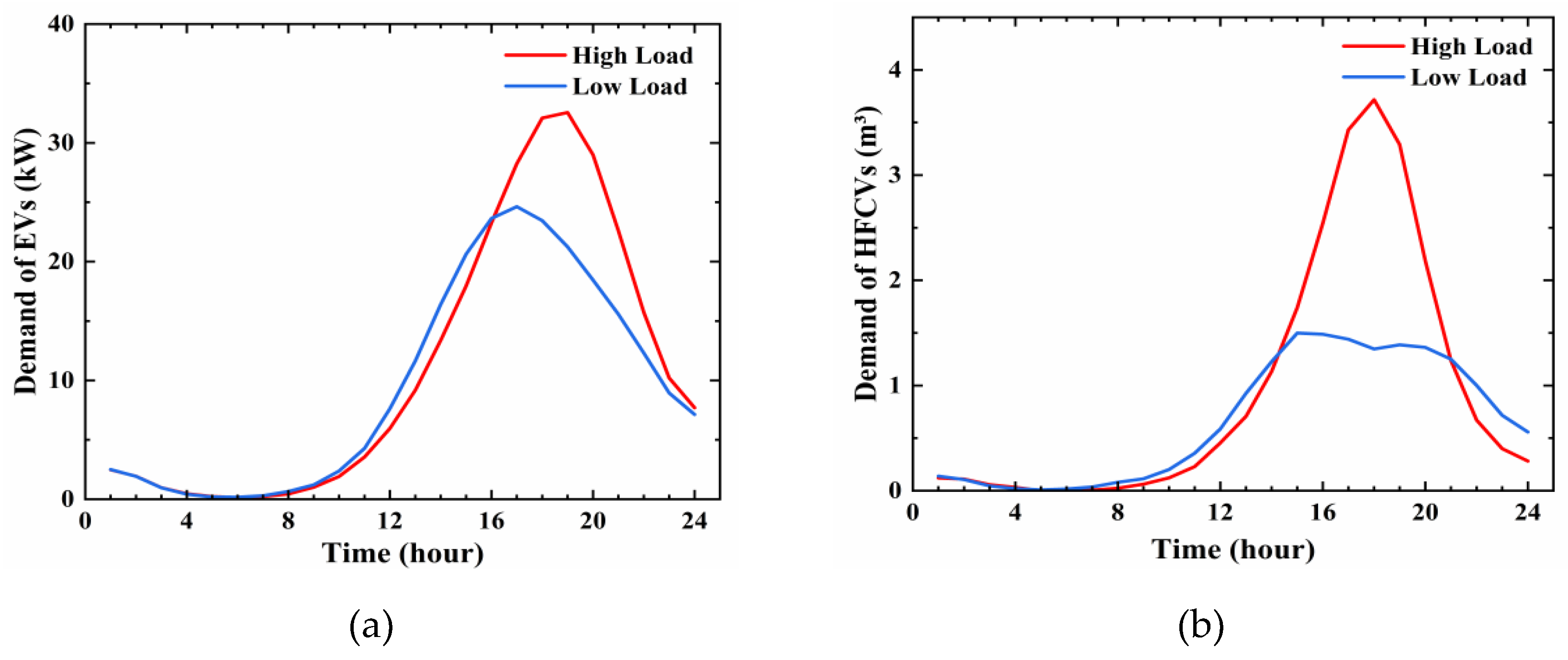

Figure 8.

Monte Carlo Simulation of Charging Load for Vehicles (a) EVs load demand curve (b) HFCVs load demand curve.

Figure 8.

Monte Carlo Simulation of Charging Load for Vehicles (a) EVs load demand curve (b) HFCVs load demand curve.

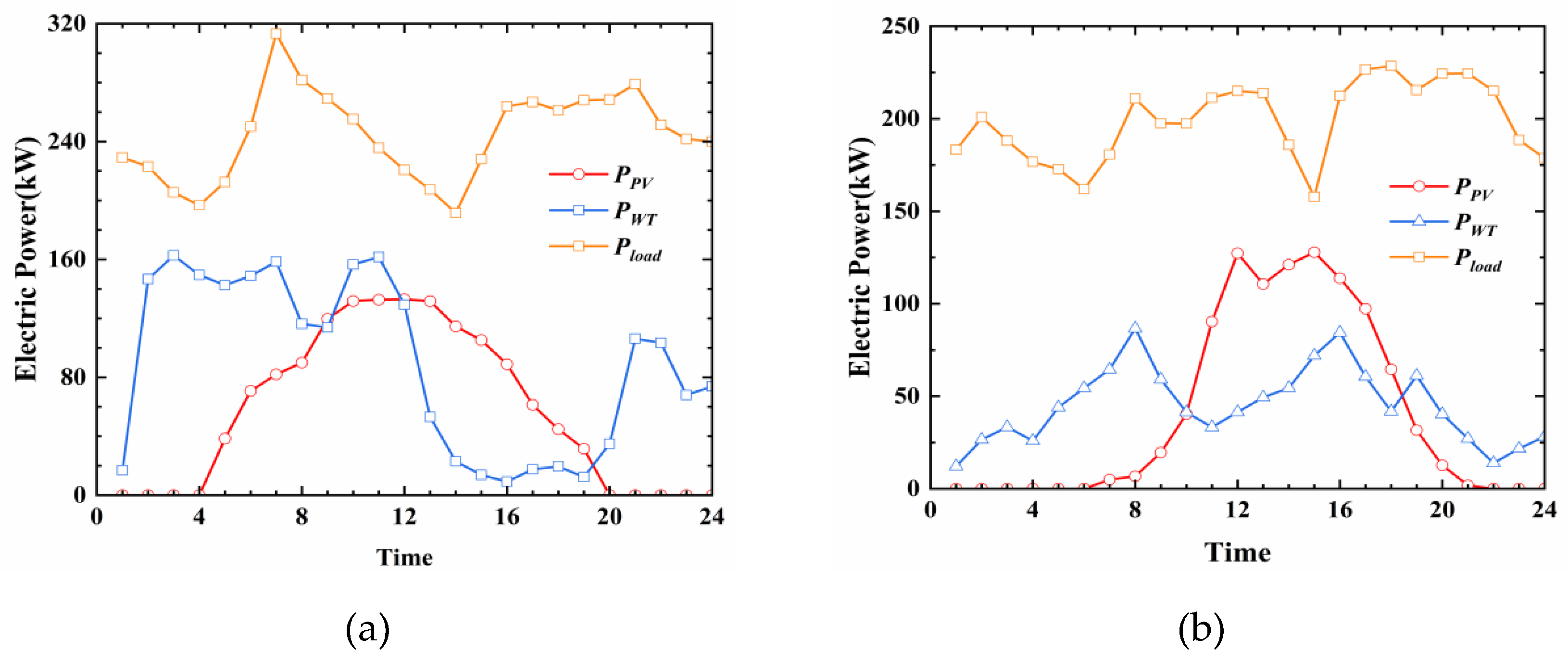

Figure 9.

Comparison of New Energy Power Generation and Load Forecasting (a) Typical day with high WT and PV power generation and high load (b) Typical day with low WT and PV power generation and low load.

Figure 9.

Comparison of New Energy Power Generation and Load Forecasting (a) Typical day with high WT and PV power generation and high load (b) Typical day with low WT and PV power generation and low load.

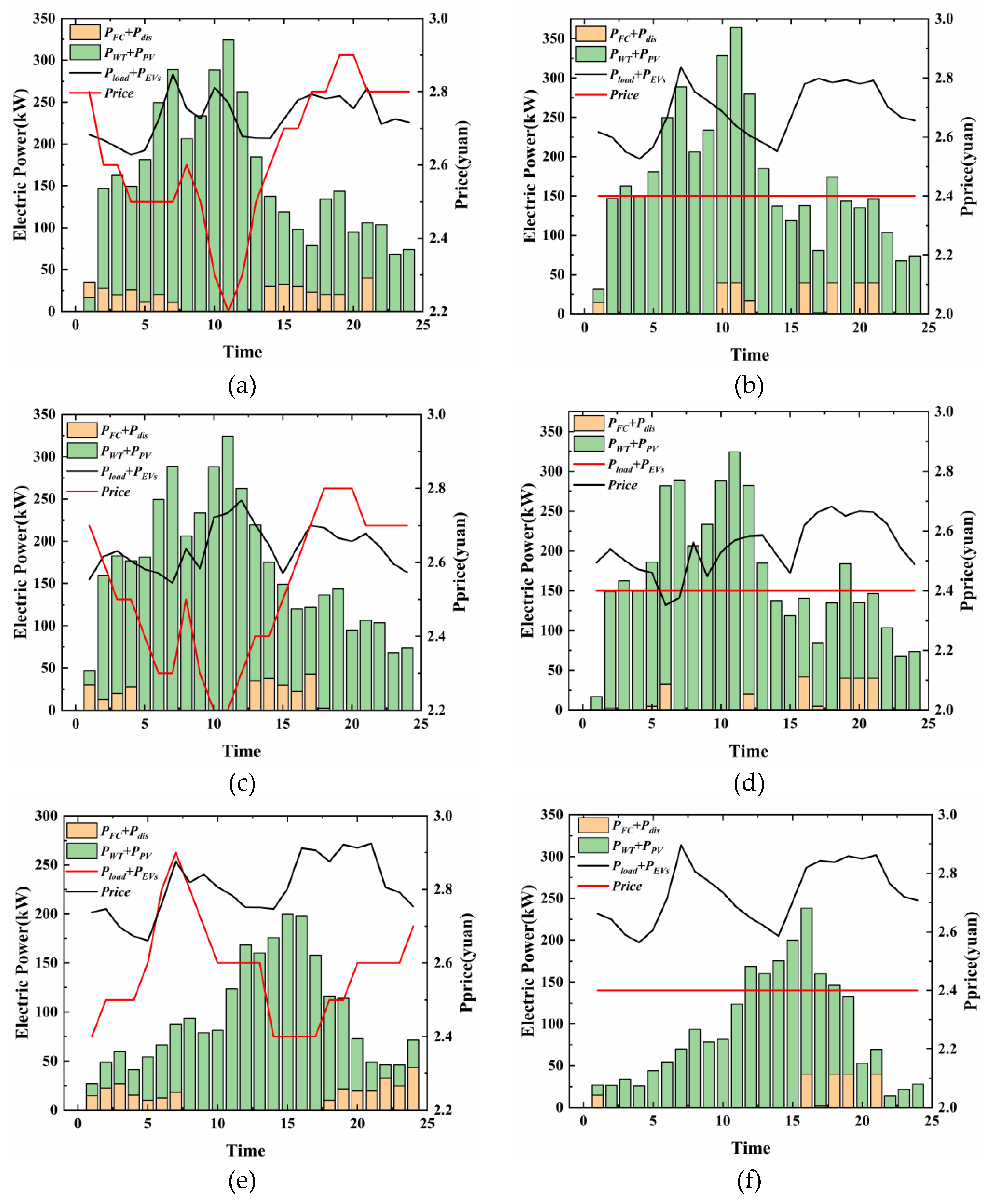

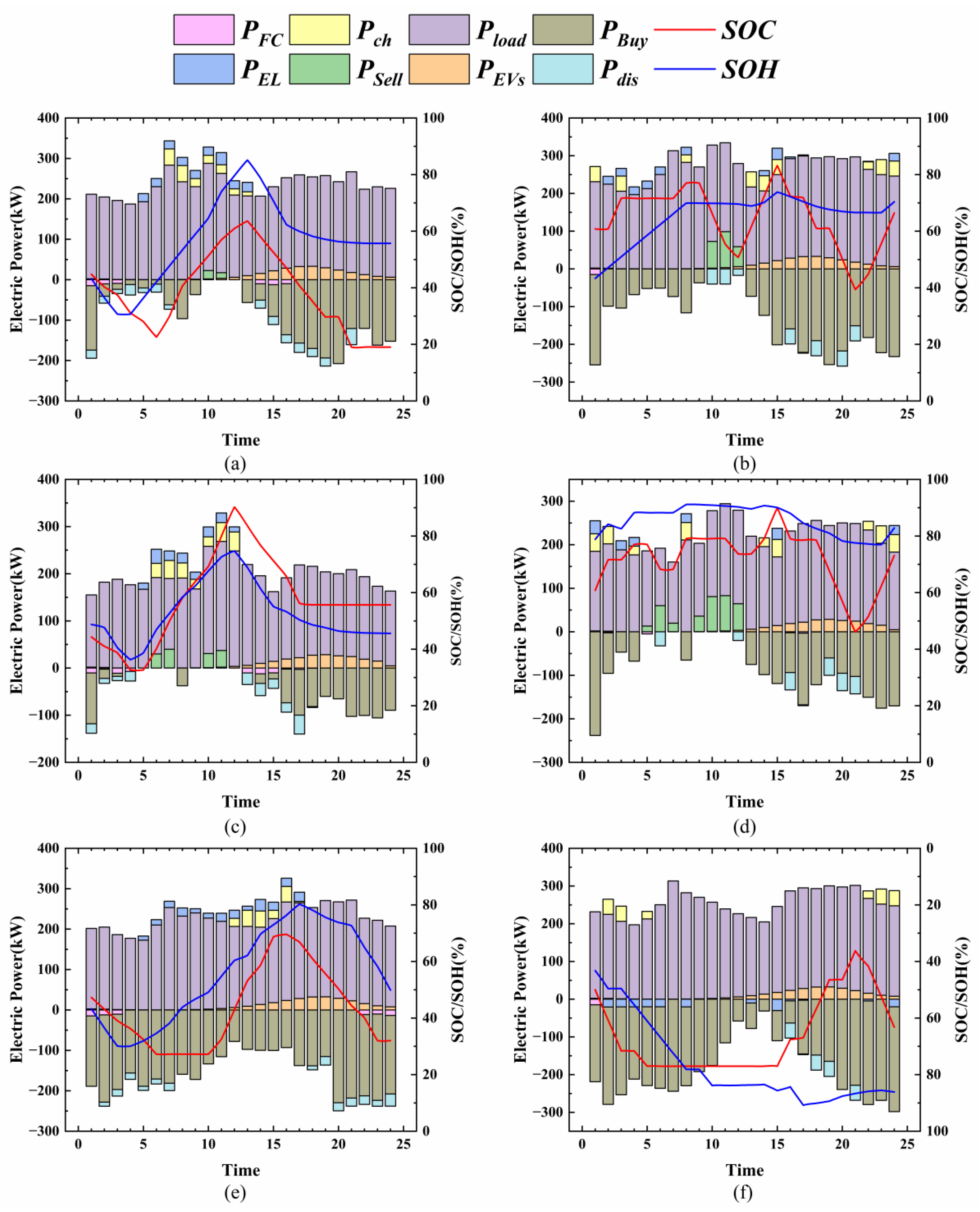

Figure 10.

Electricity Price on Dispatched Units and Load Reduction (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (b) Case I constant price strategy scheduling situation (c) Case II dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (d) Case II constant price strategy scheduling situation (e) Case III dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (f) Case III constant price strategy scheduling situation.

Figure 10.

Electricity Price on Dispatched Units and Load Reduction (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (b) Case I constant price strategy scheduling situation (c) Case II dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (d) Case II constant price strategy scheduling situation (e) Case III dynamic pricing strategy scheduling situation (f) Case III constant price strategy scheduling situation.

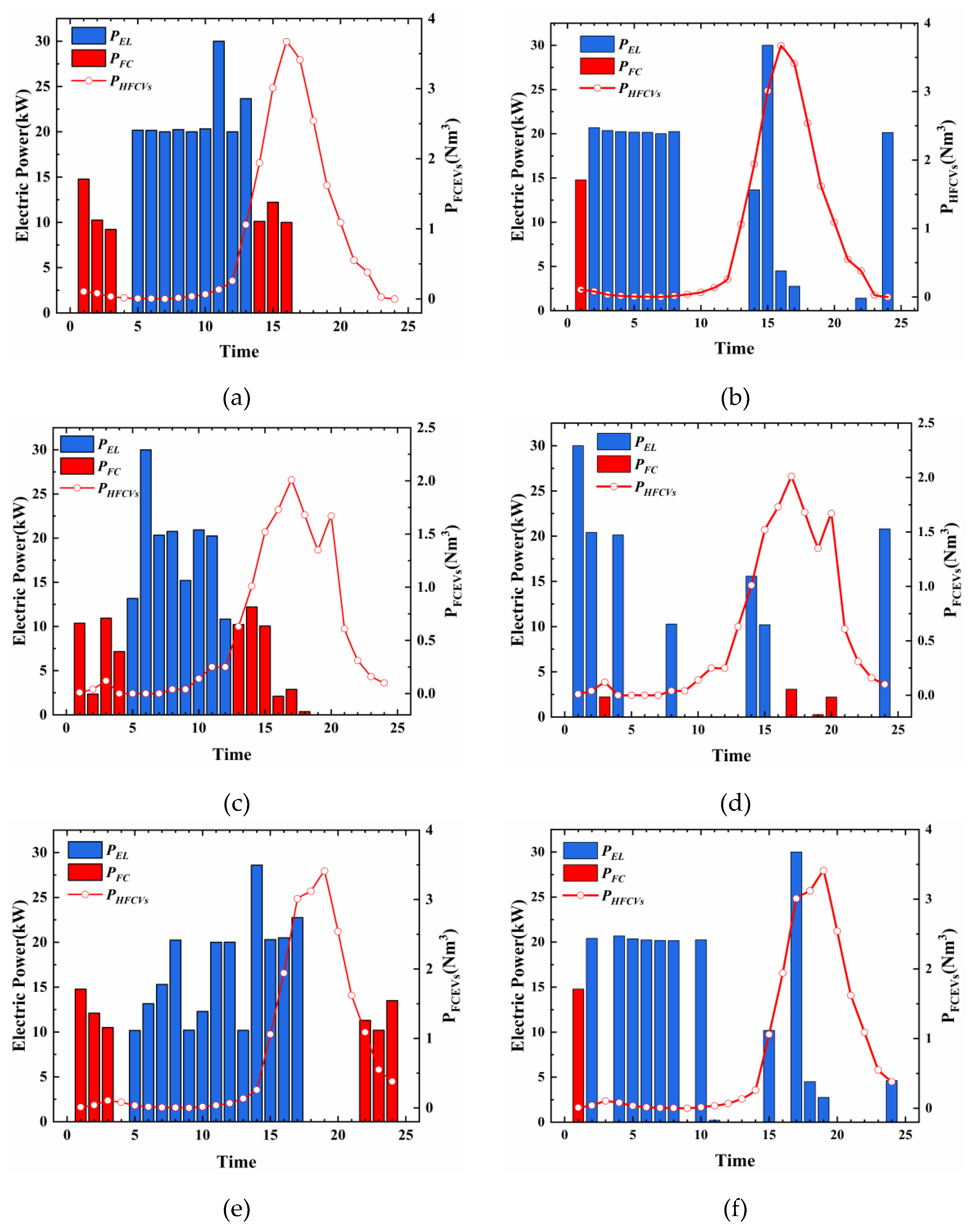

Figure 11.

Scheduling and Operation Results of Hydrogen Components (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy hydrogen components scheduling situation (b) Case I constant price strategy hydrogen components scheduling situation (c) Case II hydrogen components scheduling situation (d) Case II hydrogen components scheduling situation (e) Case III hydrogen components scheduling situation (f) Case III hydrogen components scheduling situation scheduling situation.

Figure 11.

Scheduling and Operation Results of Hydrogen Components (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy hydrogen components scheduling situation (b) Case I constant price strategy hydrogen components scheduling situation (c) Case II hydrogen components scheduling situation (d) Case II hydrogen components scheduling situation (e) Case III hydrogen components scheduling situation (f) Case III hydrogen components scheduling situation scheduling situation.

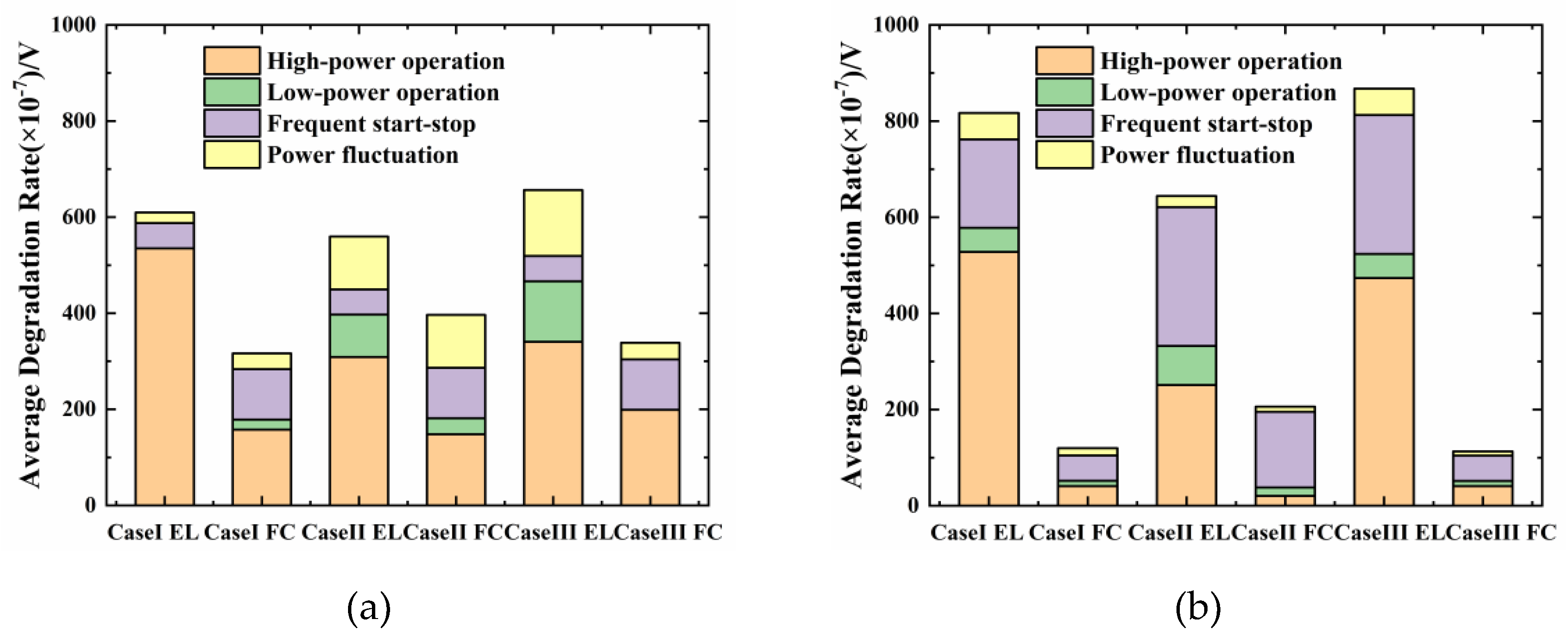

Figure 12.

Degradation of PEMEL and PEMFC (a) Dynamic pricing strategy degradation (b) Constant electricity price degradation.

Figure 12.

Degradation of PEMEL and PEMFC (a) Dynamic pricing strategy degradation (b) Constant electricity price degradation.

Figure 13.

Day-ahead scheduling results of three different scenarios (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (b) Case I constant price strategy system scheduling result (c) Case II dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (d) Case II constant price strategy system scheduling result (e) Case III dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (f) Case III constant price strategy system scheduling result.

Figure 13.

Day-ahead scheduling results of three different scenarios (a) Case I dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (b) Case I constant price strategy system scheduling result (c) Case II dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (d) Case II constant price strategy system scheduling result (e) Case III dynamic pricing strategy system scheduling result (f) Case III constant price strategy system scheduling result.

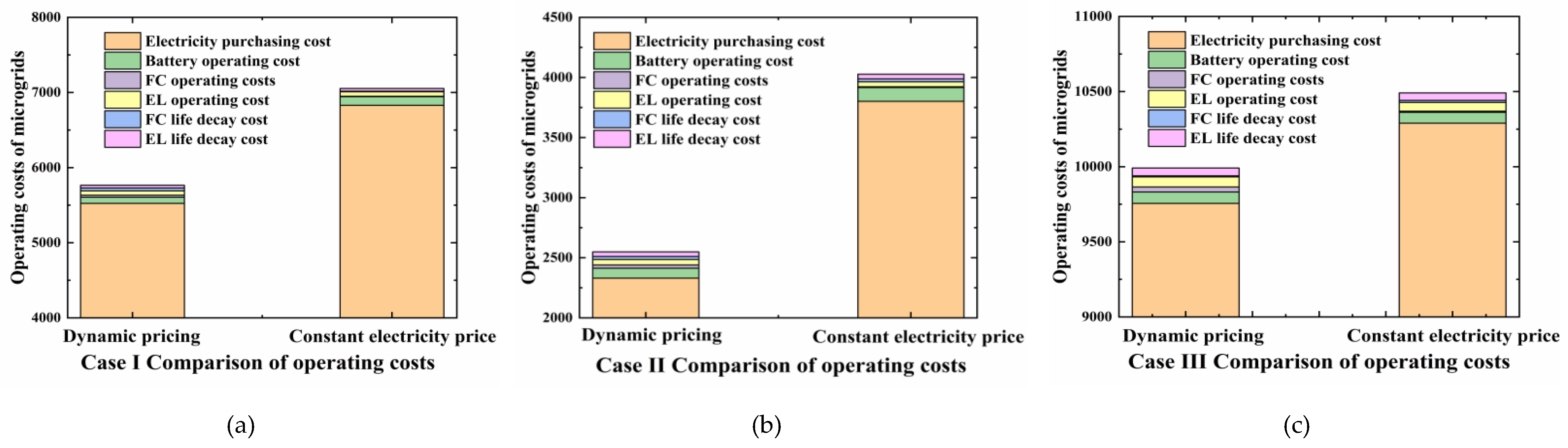

Figure 14.

Comparison of IHES operation costs (a) Case I comparison of operation costs (b) Case II comparison of operation costs (c) Case III comparison of operation costs.

Figure 14.

Comparison of IHES operation costs (a) Case I comparison of operation costs (b) Case II comparison of operation costs (c) Case III comparison of operation costs.