Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The bighorn sheep is listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. By interspecies somatic cell nuclear transfer (ISCNT), other endangered species are cloned using somatic cells as nuclear donors, fusing them with enucleated oocytes from heterologous domestic species. On the other hand, resveratrol added during in vitro maturation (IVM) of domestic sheep oocytes favors the development of embryos produced in vitro. The aim of this study was to treat O. aries oocytes with resveratrol during IVM using them as cytoplasts in ISCNT via handmade cloning (HMC), evaluating its effect on the in vitro development of Mexican bighorn sheep (O. c. mexicana) cloned embryos. Post-mortem skin fibroblasts from an adult male specimen from the Chapultepec Zoo were frozen for 8 years, thawed, and reseeded for 8 cell passages. For IVM, O. aries oocytes were treated with 0, 0.5, or 1.0 µM resveratrol. Matured oocytes were manually enucleated, and triplets (O. aries cytoplast-O. c. mexicana karyoplast-O. aries cytoplast) were formed and electrically fused. The reconstructed embryos were chemically activated and cultured until they developed into blastocysts. For IVM, no differences were found between treatments, yet at 0.5 µM, resveratrol significantly increased (p<0.05) the blastocyst rate and decreased the fragmentation rate.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In vitro Culture of Fibroblasts from Bighorn Sheep (O. c. mexicana)

2.2. In Vitro Maturation of Domestic Sheep (O. aries) Oocytes

2.3. Production of O. c. mexicana Cloned Embryos by ISCNT Via HMC

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

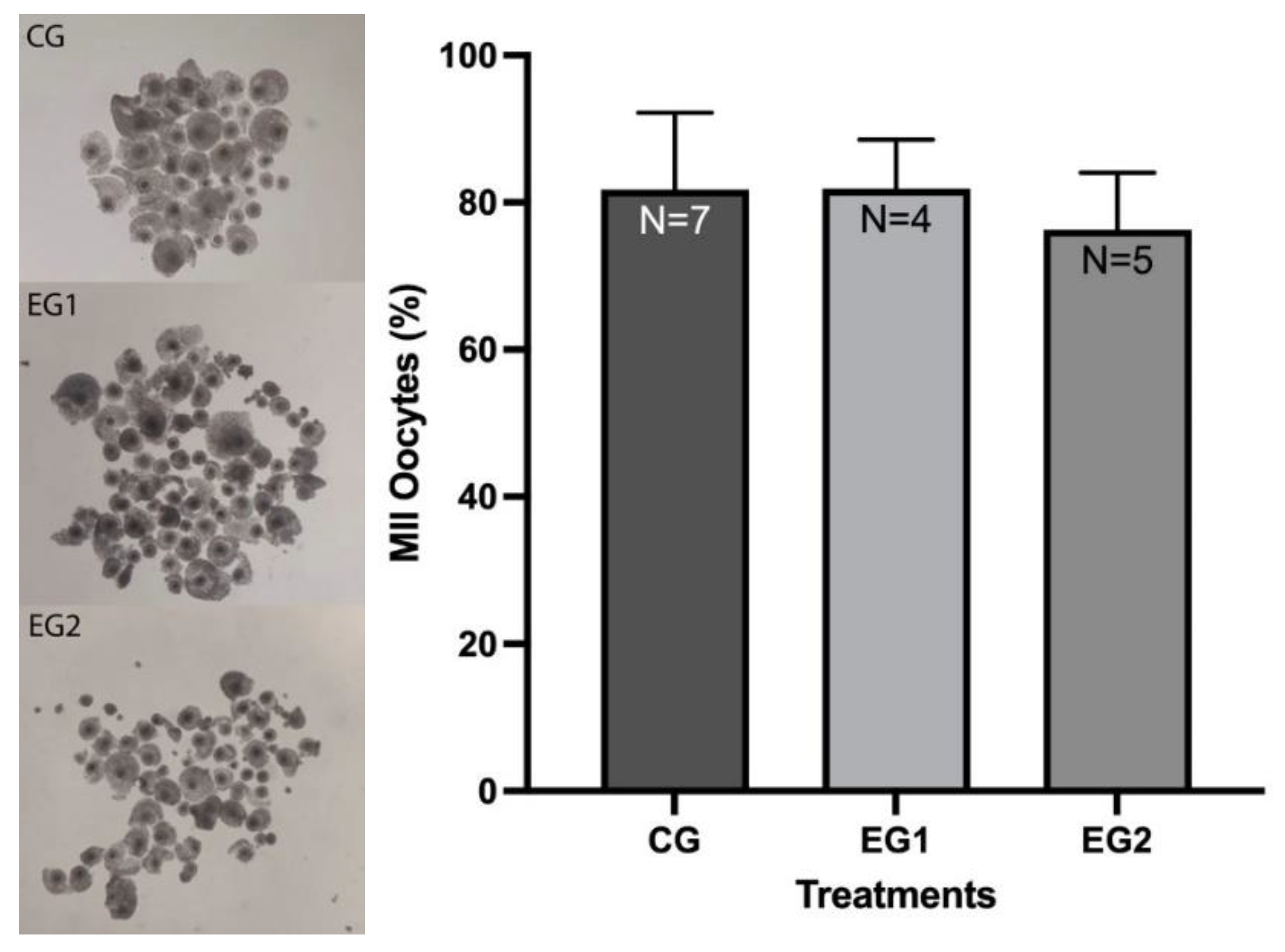

3.1. Effect of Resveratrol on the IVM Rate of O. aries Oocytes

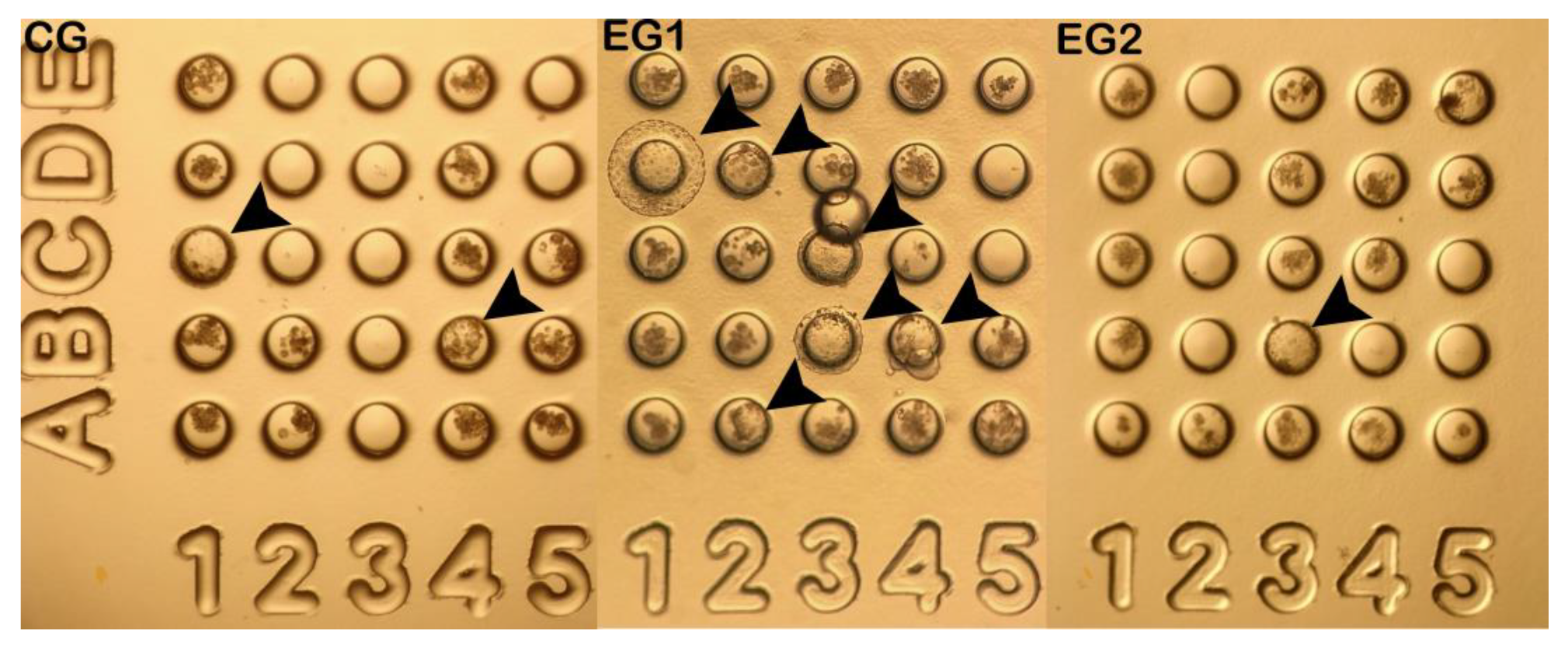

3.2. Production of O. c. mexicana Cloned Embryos by ISCNT Via HMC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gobierno de México. (17 de noviembre 2023). Bancos de germoplasma, protectores de la soberanía nacional. https://www.gob.mx.

- Festa-Bianchet, M. (2020). Ovis canadensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T15735A22146699. [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México. (5 marzo 2015). En franja de recuperación, borrego cimarrón en México. Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. https://www.gob.mx.

- Rosete, F, J, V., Álvarez, G. H., Urbán, D. D., Fragoso, I. A., Asprón, P. M. A., Ríos, U. A., Pérez, R. S., & De La Torre, S. J. F. (2021). Biotecnologías reproductivas en el ganado bovino: cinco décadas de investigación en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias, 12 (Supl 3):39-78. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Maldonado, M. C., García, A. D., & Serrrano, H. (2003). Técnicas de clonación de embriones. Ciencia Veterinaria, 9-2003-4.

- Lagutina, I., Fulka, H., Lazzari, G., & Galli, C. (2013). Interspecies somatic cell nuclear transfer: advancements and problems. Cellular reprogramming, 15(5), 374–384. [CrossRef]

- Folch, J., Cocero, M. J., Chesné, P., Alabart, J. L., Domínguez, V., Cognié, Y., Roche, A., Fernández-Arias, A., Martí, J. I., Sánchez, P., Echegoyen, E., Beckers, J. F., Bonastre, A. S., & Vignon, X. (2009). First birth of an animal from an extinct subspecies (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) by cloning. Theriogenology, 71(6), 1026–1034. [CrossRef]

- Loi, P., Ptak, G., Barboni, B., Fulka, J., Jr, Cappai, P., & Clinton, M. (2001). Genetic rescue of an endangered mammal by cross-species nuclear transfer using post-mortem somatic cells. Nature biotechnology, 19(10), 962–964. [CrossRef]

- Lanza, R. P., Cibelli, J. B., Diaz, F., Moraes, C. T., Farin, P. W., Farin, C. E., Hammer, C. J., West, M. D., & Damiani, P. (2000). Cloning of an endangered species (Bos gaurus) using interspecies nuclear transfer. Cloning, 2(2), 79–90. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, S., Hernández-Pichardo, J.E., Vazquez-Avendaño, J.R., Ambríz-García D.A. & Navarro-Maldonado M.d.C. (2020). Developmental dynamics of cloned Mexican bighorn sheep embryos using morphological quality standards. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 6, 382–392. [CrossRef]

- Wilmut, I., Schnieke, A. E., McWhir, J., Kind, A. J., & Campbell, K. H. (1997). Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature, 385(6619), 810–813. [CrossRef]

- Verma, G., Arora, J. S., Sethi, R. S., Mukhopadhyay, C. S., & Verma, R. (2015). Handmade cloning: recent advances, potential and pitfalls. Journal of animal science and biotechnology, 6, 43. [CrossRef]

- Galli, C., & Lazzari, G. (2021). Current applications of SCNT in advanced breeding and genome editing in livestock. Reproduction. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ibarra, J.L., Espinoza-Mendoza, E.A., Rangel-Santos, R., Ambriz-García, D.A., & Navarro-Maldonado, M.D.C. (2018). Effect of resveratrol on the in vitro maturation of ovine (Ovis aries) oocytes and the subsequent development of handmade cloned embryos. Veterinaria México, 5(4). [CrossRef]

- González-Garzón, A. C., Ramón-Ugalde, J. P., Ambríz-García, D. A., Vazquez-Avendaño, J. R., Hernández-Pichardo, J. E., Rodríguez-Suastegui, J. L., Cortez-Romero, C., & Del Carmen Navarro-Maldonado, M. (2023). Resveratrol Reduces ROS by Increasing GSH in Vitrified Sheep Embryos. Animals, 13(23), 3602. [CrossRef]

- Gambini, J., López-Grueso, R., Olaso-González, G., Inglés, M., Abdelazid, K., Alami, M. E., Bonet-Costa, V., Borrás, C., & Viña, J. (2013). Resveratrol: distribución, propiedades y perspectivas. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología, 48(2), 79-88. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S. S., Cheong, S. A., Jeon, Y., Lee, E., Choi, K. C., Jeung, E. B., & Hyun, S. H. (2012). The effects of resveratrol on porcine oocyte in vitro maturation and subsequent embryonic development after parthenogenetic activation and in vitro fertilization. Theriogenology, 78(1), 86–101. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K., & Yamanaka, S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell, 126(4), 663–676. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Maldonado M. C., Hernández-Martínez S., Vázquez-Avendaño J. R., Martínez-Ibarra J. L., Zavala-Vega N. L.,Vargas-Miranda B., Rivera-Rebolledo J. A. & Ambríz-García D. A. (2015). Deriva de células epiteliales de tejido de piel descongelado de Ovis canadensis mexicana para la formación de un banco de germoplasma. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n. s.), 31(2): 275-282.

- Vazquez-Avendaño, J. R., Hernández-Martínez, S., Hernández- Pichardo, J. E., Rivera-Rebolledo, J. A., Ambriz-García, D. A., & Navarro-Maldonado, M. C. (2017). Efecto del uso de medio secuencial humano en la producción de blastocistos de hembra Ovis canadensis mexicana por clonación manual interespecies. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.), 33(2), 328-338.

- Asociación para el Estudio de la Biología Reproductiva (ASEBIR). (2015). Criterios ASEBIR de valoración morfológica de ovocitos, embriones tempranos y blastocistos humanos. Cuadernos de embriología clínica (3th ed., pp. 9–75). Madrid: ASEBIR.

- Vajta, G., Korösi, T., Du, Y., Nakata, K., Ieda, S., Kuwayama, M., & Nagy, Z. P. (2008). The Well-of-the-Well system: an efficient approach to improve embryo development. Reproductive biomedicine online, 17(1), 73–81. [CrossRef]

- Wakayama, S., Ito, D., Hayashi, E., Ishiuchi, T., & Wakayama, T. (2022). Healthy cloned offspring derived from freeze-dried somatic cells. Nature Communications, 13:3666. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. K., Kang, M. H., Gurunathan, S., Cho, S. G., Park, C., Park, J. K., & Kim, J. H. (2015). Pifithrin-α ameliorates resveratrol-induced two-cell block in mouse preimplantation embryos in vitro. Theriogenology, 83(5), 862–873. [CrossRef]

- Itami, N., Shirasuna, K., Kuwayama, T., & Iwata, H. (2015). Resveratrol improves the quality of pig oocytes derived from early antral follicles through sirtuin 1 activation. Theriogenology, 83(8), 1360–1367. [CrossRef]

- Nagafuchi, A., Shirayoshi, Y., Okazaki, K., Yasuda, K. & Takeichi, M. (1987) Transformation of cell adhesión properties by exogenously introduced E-cadherin cDNA. Nature, 29, 341–3.

- Watson, A. J. & Barcroft, L.C. 2001. Regulation of blastocyst formation. Frontiers in Bioscience 6, d708-730, May 1, 2001.

- Stroud, T.K., Xiang, T., Romo, S., & Kjelland, M.E. (2014). Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis) embryos produced using somatic cell nuclear transfer. Reproduction, Fertility and Development, 26(1), 133-133. [CrossRef]

- Vajta, G., Lewis, I. M., Hyttel, P., Thouas, G. A., & Trounson, A. O. (2001). Somatic cell cloning without micromanipulators. Cloning, 3(2), 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Kragh, P., Zhang, X., Purup, S., Yang, H., Bolund, L., & Vajta, G. (2005). High Overall In Vitro Efficiency of Porcine Handmade Cloning (HMC) Combining Partial Zona Digestion and Oocyte Trisection with Sequential Culture. Cloning And Stem Cells, 7(3), 199-205. [CrossRef]

- Kumbha, R., Hosny, N., Matson, A., Steinhoff, M., Hering, B. J., & Burlak, C. (2020). Efficient production of GGTA1 knockout porcine embryos using a modified handmade cloning (HMC) method. Research in Veterinary Science, 128, 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Liu, P., Dou, H., Chen, L., Chen, L., Lin, L., Tan, P., Vajta, G., Gao, J., Du, Y., & Ma, R. Z. (2013). Handmade cloned transgenic sheep rich in omega-3 Fatty acids. PloS one, 8(2), e55941. [CrossRef]

- Tecirlioglu, R. T., Cooney, M. A., Lewis, I. M., Korfiatis, N. A., Hodgson, R., Ruddock, N. T., Vajta, G., Downie, S., Trounson, A. O., Holland, M. K., & French, A. J. (2005). Comparison of two approaches to nuclear transfer in the bovine: hand-made cloning with modifications and the conventional nuclear transfer technique. Reproduction, fertility, and development, 17(5), 573–585. [CrossRef]

- Vajta, G., Lewis, I. M., Trounson, A. O., Purup, S., Maddox-Hyttel, P., Schmidt, M., Pedersen, H. G., Greve, T., & Callesen, H. (2003). Handmade somatic cell cloning in cattle: analysis of factors contributing to high efficiency in vitro. Biology of reproduction, 68(2), 571–578. [CrossRef]

- Cortez, J., Murga, N., Segura, G., Rodríguez, L., Vásquez, H., & Maicelo-Quintana, J. (2017). Capacidad de Dos Líneas Celulares para la Producción de Embriones Clonados mediante Transferencia Nuclear de Células Somáticas. Revista de Investigaciones Veterinarias del Perú, 28(4), 928-938. [CrossRef]

- Lagutina, I., Lazzari, G., Duchi, R., Colleoni, S., Ponderato, N., Turini, P., Crotti, G., & Galli, C. (2005). Somatic cell nuclear transfer in horses: effect of oocyte morphology, embryo reconstruction method, and donor cell type. Reproduction (Cambridge, England), 130(4), 559–567. [CrossRef]

- Selokar, N. L., George, A., Saha, A. P., Sharma, R., Muzaffer, M., Shah, R. A., Palta, P., Chauhan, M. S., Manik, R. S., & Singla, S. K. (2011). Production of interspecies handmade cloned embryos by nuclear transfer of cattle, goat, and rat fibroblasts to buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) oocytes. Animal reproduction science, 123(3-4), 279–282. [CrossRef]

- Priya, D., Selokar, N. L., Raja, A. K., Saini, M., Sahare, A. A., Nala, N., Palta, P., Chauhan, M. S., Manik, R. S., & Singla, S. K. (2014). Production of wild buffalo (Bubalus arnee) embryos by interspecies somatic cell nuclear transfer using domestic buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) oocytes. Reproduction in domestic animals = Zuchthygiene, 49(2), 343–351. [CrossRef]

- Duah, E.K., Mohapatra, S.K., Sood, T.J., Sandhu, A., Singla, S.K., Chauhan, M.S., Manik, R.S., & Palta, P. (2016). Production of hand-made cloned buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) embryos from non-viable somatic cells. In Vitro Cell Development Biology Animal. Dec;52(10):983-988.

- Pan, X., Zhang, Y., Guo, Z., & Wang, F. (2014). Development of interspecies nuclear transfer embryos reconstructed with argali (Ovis ammon) somatic cells and sheep ooplasm. Cell biology international, 38(2), 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Hajian, M., Hosseini, S.M., Forouzanfar, M., Abedi, P., Ostadhosseini, S., Hosseini, L., Moulavi, F., Gourabi, H., Shahverdi, A.H., Vosough Taghi Dizaj, A., Kalantari, S.A., Fotouhi, Z., Iranpour, R., Mahyar, H., Amiri-Yekta, A., Nasr-Esfahani, M.H., 2011. “Conservation cloning” of vulnerable Esfahan mouflon (Ovis orientalis isphahanica): in vitro and in vivo studies. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 57, 959–969. [CrossRef]

| Group | No. | Cleavage N (%) |

4-16 cells N (%) |

Morula N (%) |

Blastocysts N (%) |

Fragmented N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 40 | 38 (94±8.0) | 6 (16±18.5) | 9 (21±15.4) | 6 (16±3.2)a | 17 (46±8.8)a |

| EG1 | 69 | 69 (100) | 12 (20±22.9) | 16 (24±6.5) | 22 (31±12.0)b | 19 (25±10.4)b |

| EG2 | 32 | 32 (100) | 8 (20±19.9) | 8 (26±17.3) | 2 (6±6.3)a | 14 (42±6.4)a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).