Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

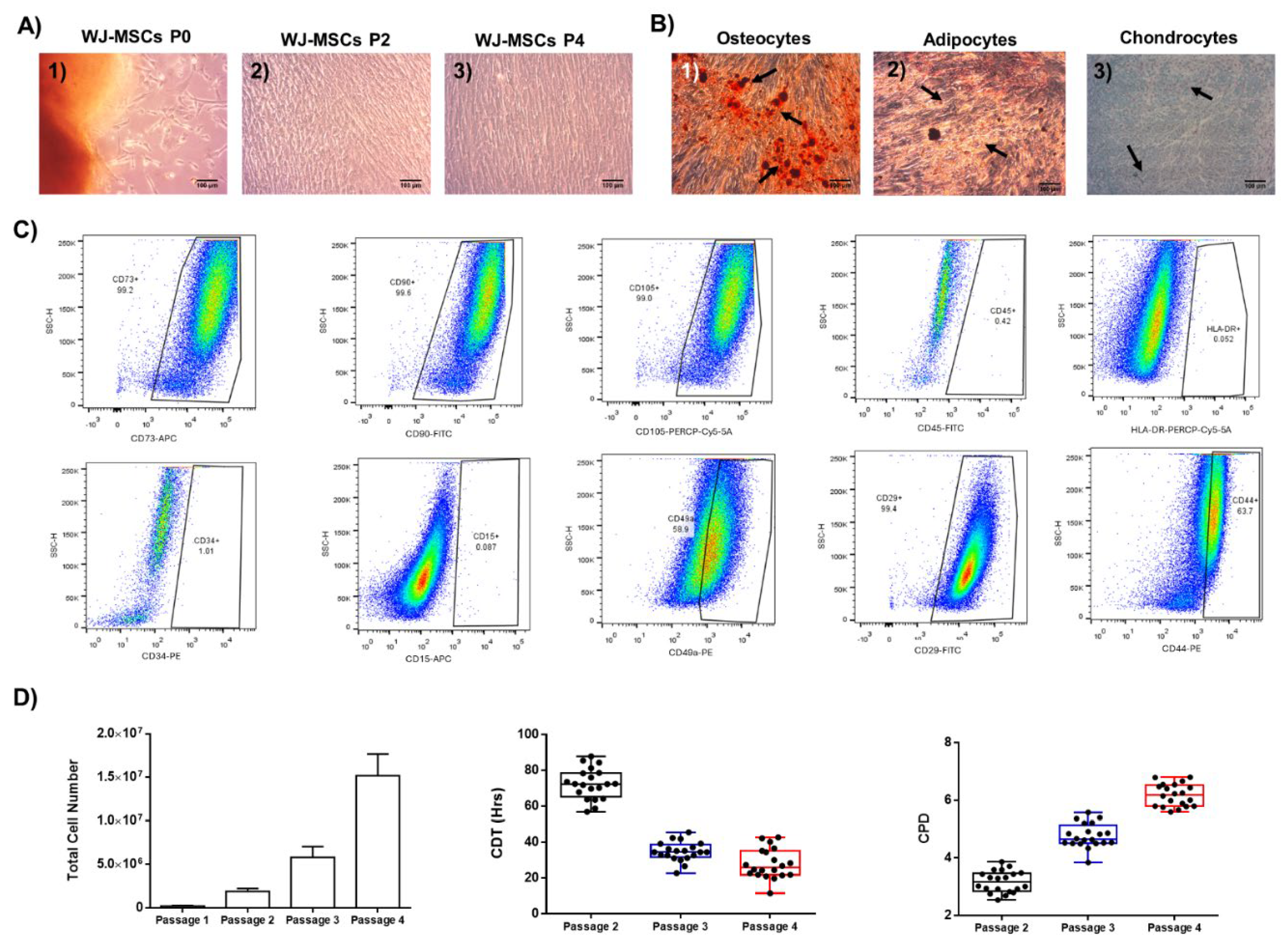

2.1. Characterization of Well-Defined Wj-Mscs

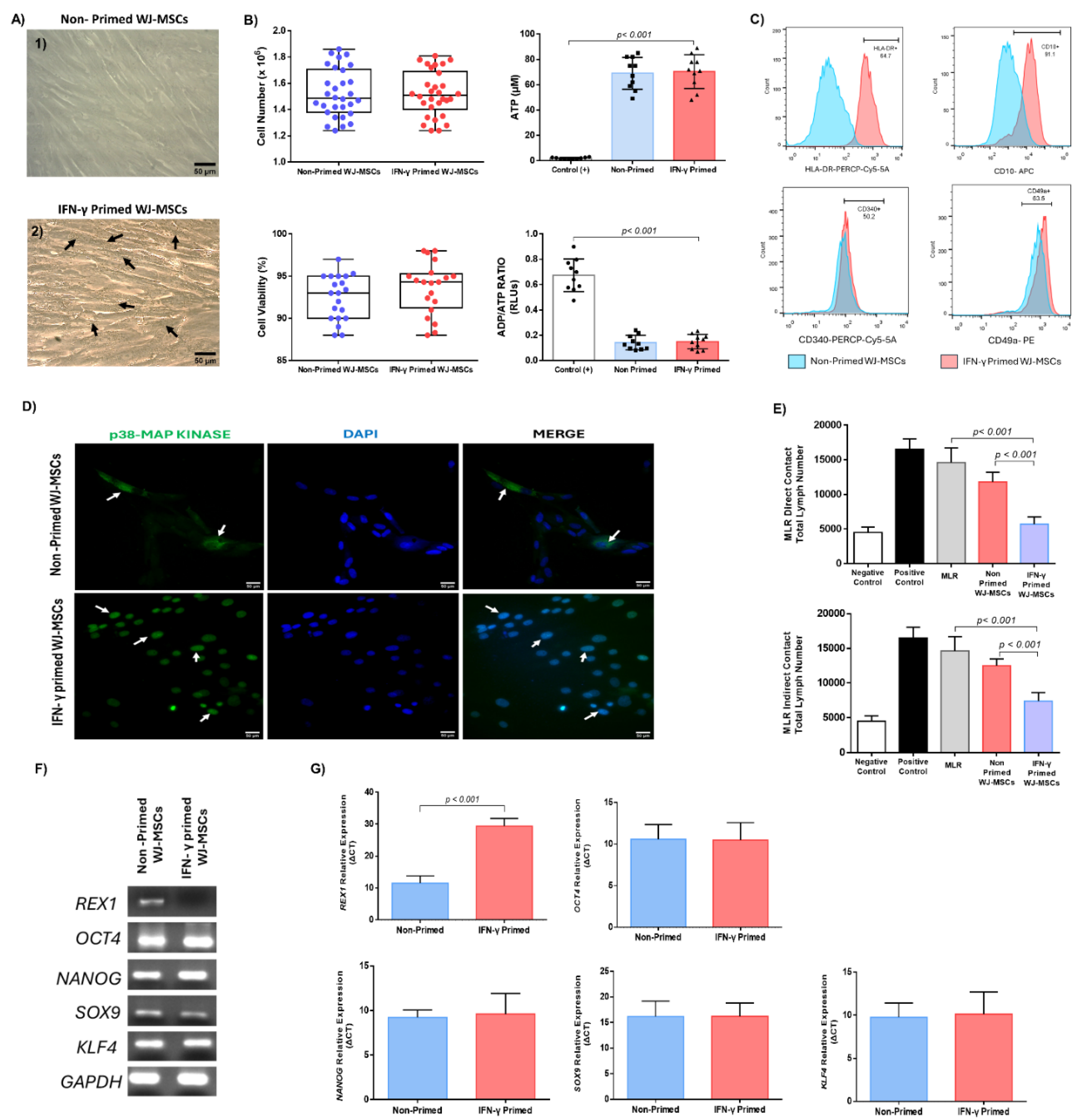

2.2. Impact of Ifn-Γ Priming On Wj-Mscs Characteristics

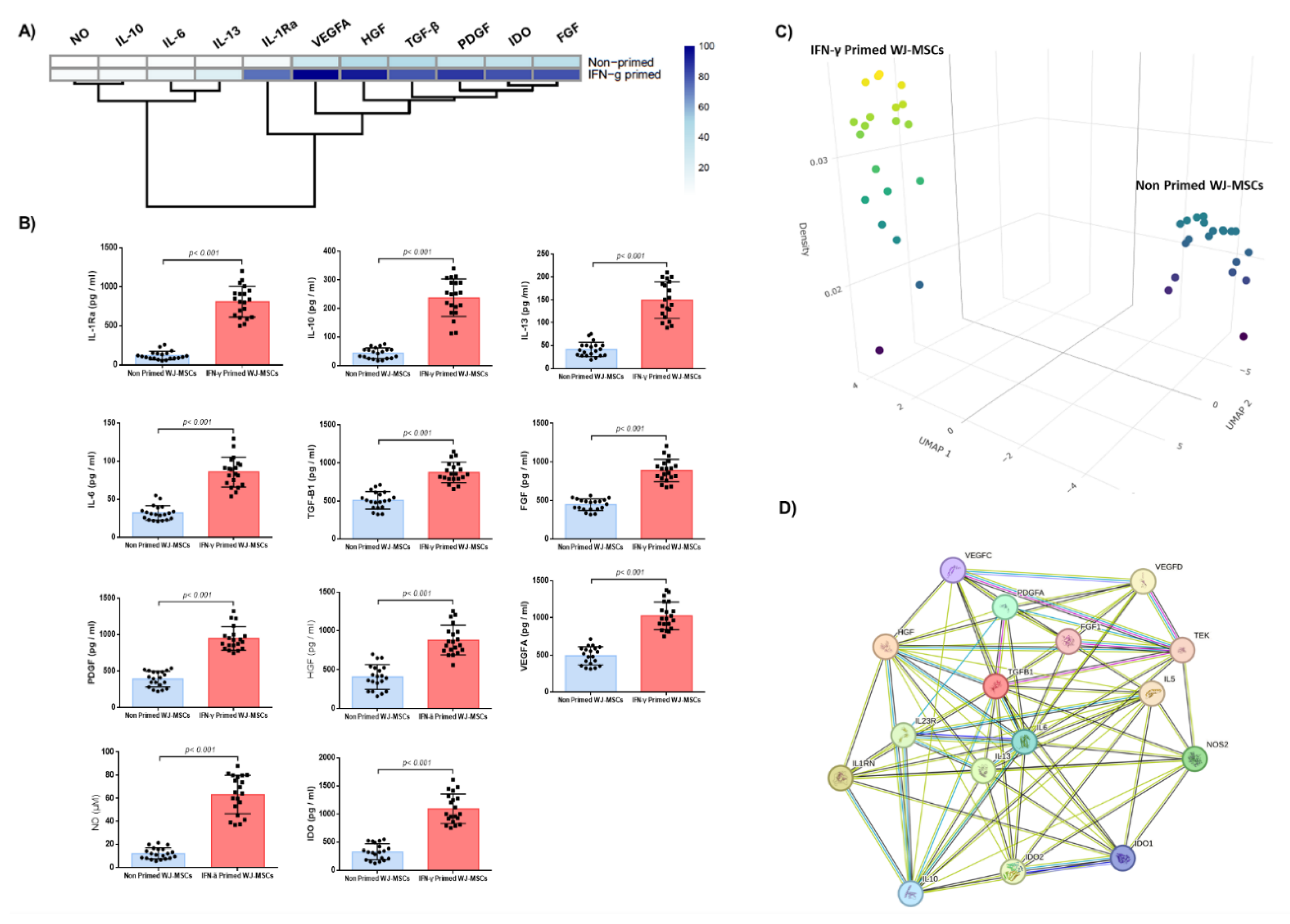

2.3. Biomolecules Quantification

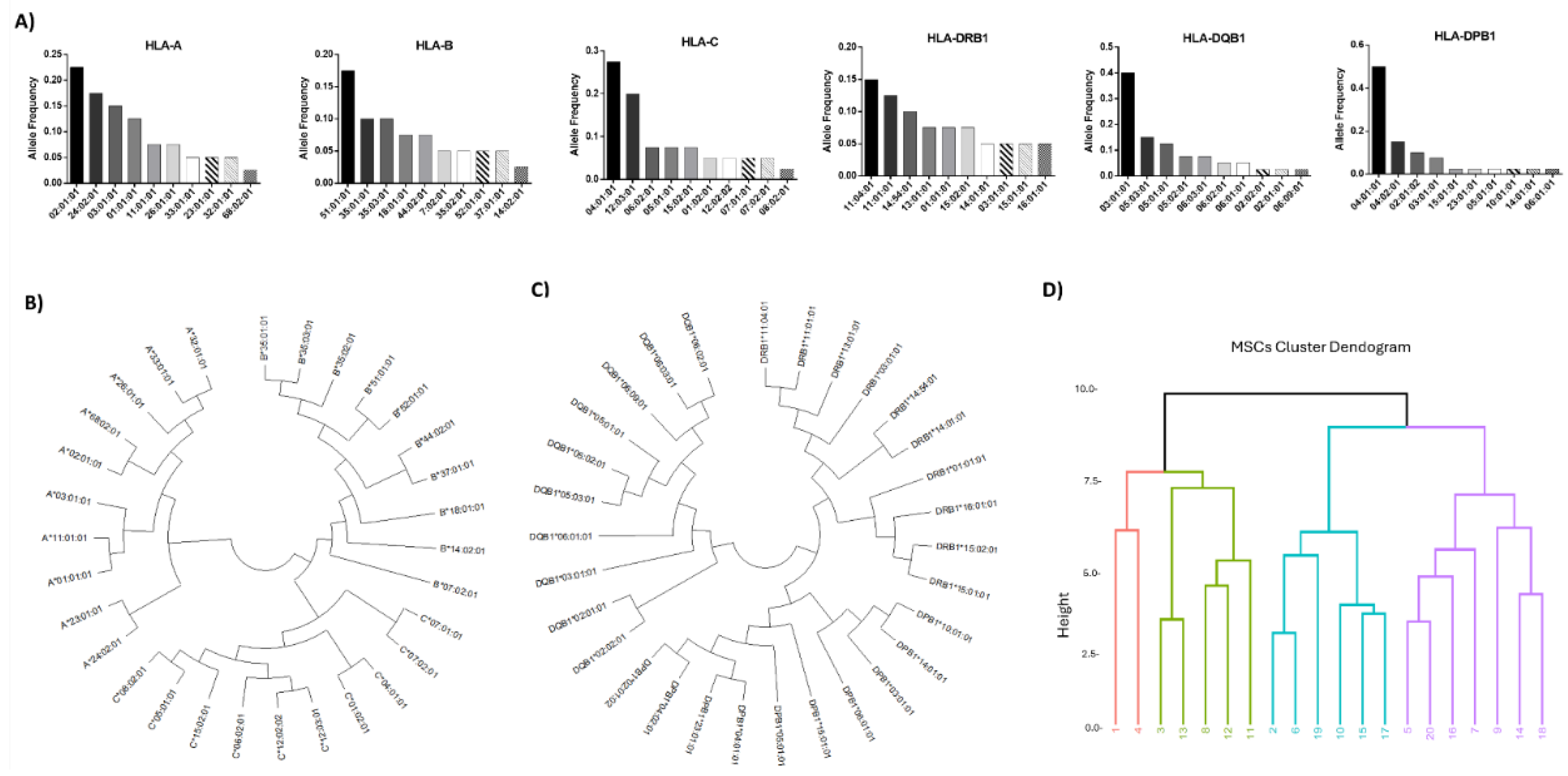

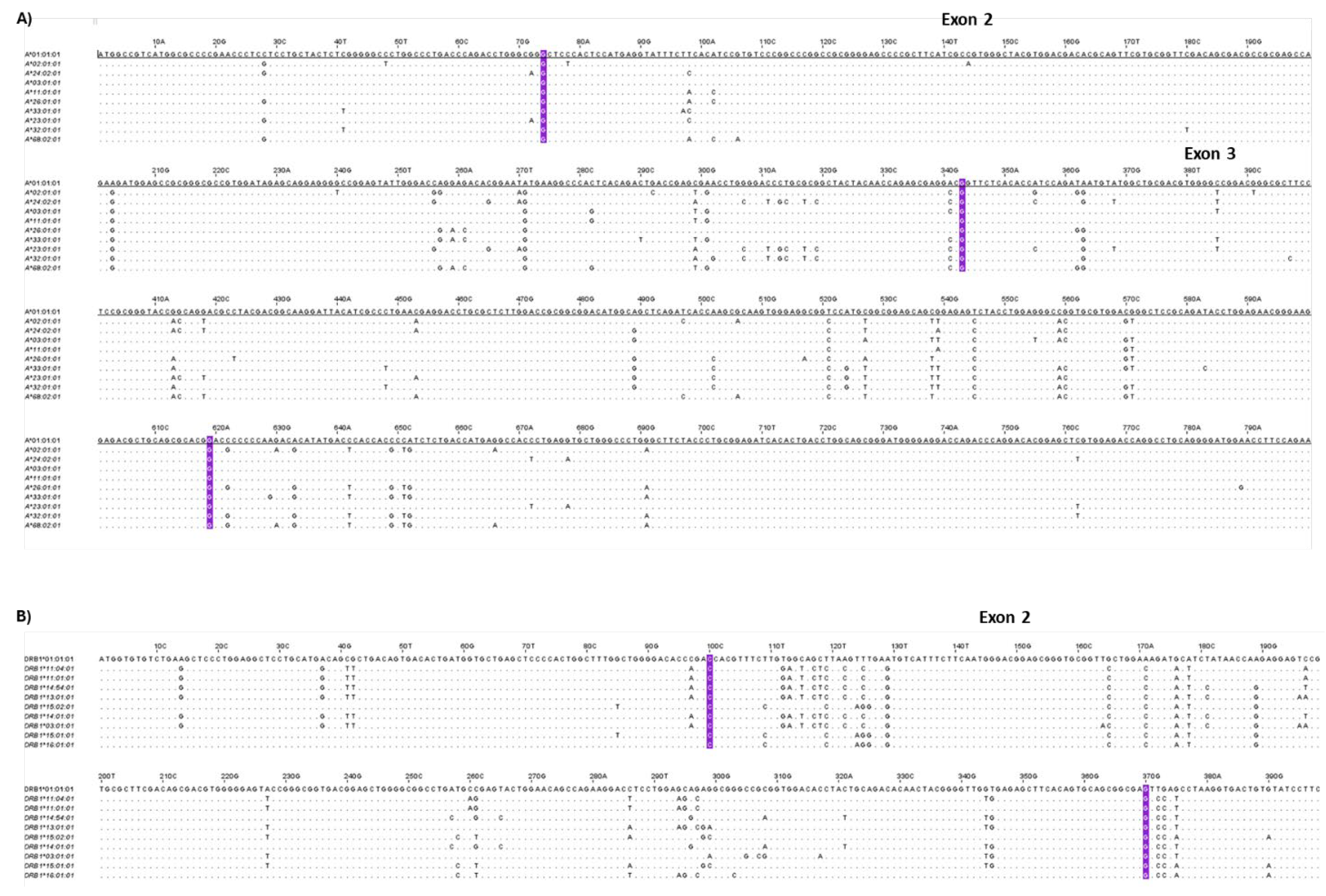

2.4. Analysis of Hla Class I and Ii Alleles In Wj-Mscs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Statement

4.2. Isolation and Expansion of Wj-Mscs

4.3. Growth Kinetics of Wj-Mscs

4.4. Immunophenotypic Analysis of Wj-Mscs

4.5. Trilineage Differentiation of Wj-Mscs

4.6. Ifn-Γ Priming of Wj-Mscs

4.7. Evaluation of Ifn-Γ Primed Wj-Mscs Properties

4.8. Estimation of Cell Proliferation Using The Atp Assay

4.9. Adp/Atp Assay

4.10. Quantification of Biomolecules Produced from Primed WJ-MSCs

4.11. Indirect Immunofluorescence for p38 MAP Kinase

4.12. Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction

4.13. Gene Expression Analysis

4.14. HLA Typing

4.15. Multivariate Data Analysis using RStudio

4.16. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jasim, S.A.; Yumashev, A.V.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Margiana, R.; Markov, A.; Suksatan, W.; Pineda, B.; Thangavelu, L.; Ahmadi, S.H. Shining the Light on Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy in Autoimmune Diseases. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2022 13:1 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J Orthop Res 1991, 9, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies: Immunomodulatory Properties and Clinical Progress. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2020 11:1 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchakian, M.R.; Baghban, N.; Moniri, S.F.; Baghban, M.; Bakhshalizadeh, S.; Najafzadeh, V.; Safaei, Z.; Izanlou, S.; Khoradmehr, A.; Nabipour, I.; et al. The Clinical Trials of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Therapy. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021, 1634782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G.; Di Bernardo, G. Clinical Trials Based on Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Are Exponentially Increasing: Where Are We in Recent Years? Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, K. Le; Dazzi, F.; English, K.; Farge, D.; Galipeau, J.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kadri, N.; Krampera, M.; Lalu, M.M.; Nolta, J.; et al. ISCT MSC Committee Statement on the US FDA Approval of Allogenic Bone-Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cytotherapy 2025, 27, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushahary, D.; Spittler, A.; Kasper, C.; Weber, V.; Charwat, V. Isolation, Cultivation, and Characterization of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cytometry Part A 2018, 93, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costela-ruiz, V.J.; Melguizo-rodríguez, L.; Bellotti, C.; Illescas-montes, R.; Stanco, D.; Arciola, C.R.; Lucarelli, E. Different Sources of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Tissue Regeneration: A Guide to Identifying the Most Favorable One in Orthopedics and Dentistry Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, D.G. Alexander Friedenstein, Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Shifting Paradigms and Euphemisms. Bioengineering (Basel) 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, R.; Kasper, C.; Böhm, S.; Jacobs, R. Different Populations and Sources of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC): A Comparison of Adult and Neonatal Tissue-Derived MSC. Cell Commun Signal 2011, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal Stem versus Stromal Cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Committee Position Statement on Nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal Criteria for Defining Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy Position Statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polchert, D.; Sobinsky, J.; Douglas, G.W.; Kidd, M.; Moadsiri, A.; Reina, E.; Genrich, K.; Mehrotra, S.; Setty, S.; Smith, B.; et al. IFN-γ Activation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment and Prevention of Graft versus Host Disease. Eur J Immunol 2008, 38, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, J.M.; Leng Teo, G.S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Homing: The Devil Is in the Details. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 4, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.L.; Tang, K.C.; Patel, A.P.; Bonilla, L.M.; Pierobon, N.; Ponzio, N.M.; Rameshwar, P. Antigen-Presenting Property of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Occurs during a Narrow Window at Low Levels of Interferon-γ. Blood 2006, 107, 4817–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, J.C.; Skokos, D. Th17 Response and Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases. Int J Inflam 2011, 2012, 819467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrish, C.L.; Chen, Y.; Blumenschein, W.M.; Mattson, J.; Basham, B.; Sedgwick, J.D.; McClanahan, T.; Kastelein, R.A.; Cua, D.J. IL-23 Drives a Pathogenic T Cell Population That Induces Autoimmune Inflammation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2005, 201, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Jia, F.; Li, X.; Kong, Y.; Tian, Z.; Bi, L.; Li, L. Biophysical Cues to Improve the Immunomodulatory Capacity of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: The Progress and Mechanisms. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.; Rasko, J.E.J. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Graft Versus Host Disease. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, S.; Del Sordo, R.; Mancusi, A.; Terenzi, A.; Zei, T.; Iacucci Ostini, R.; Tricarico, S.; Piccinelli, S.; Griselli, M.; Marzuttini, F.; et al. Acute GvHD after HLA-Haploidentical Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation with Regulatory and Conventional T Cell Immunotherapy Does Not Adversely Affect Transplantation Outcomes. Blood 2021, 138, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadri, N.; Amu, S.; Iacobaeus, E.; Boberg, E.; Le Blanc, K. Current Perspectives on Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy for Graft versus Host Disease. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2023 20:6 2023, 20, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenneti, P.; He, J.; Lalli, P.; Tenneti, P.; Grunwald, M.R.; Copelan, E.A.; Avalos, B.; Sanikommu, S.R.R. Incidence and Risk Factors Associated with Fatal Graft Vs Host Disease after Solid Organ Transplantation in United Network of Organ Transplant Database. Blood 2021, 138, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Simon, J.A.; López-Villar, O.; Andreu, E.J.; Rifón, J.; Muntion, S.; Campelo, M.D.; Sánchez-Guijo, F.M.; Martinez, C.; Valcarcel, D.; Del Cañizo, C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Expanded in Vitro with Human Serum for the Treatment of Acute and Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: Results of a Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Haematologica 2011, 96, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringdén, O.; Uzunel, M.; Rasmusson, I.; Remberger, M.; Sundberg, B.; Lönnies, H.; Marschall, H.U.; Dlugosz, A.; Szakos, A.; Hassan, Z.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Therapy-Resistant Graft-versus-Host Disease. Transplantation 2006, 81, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Blanc, K.; Rasmusson, I.; Sundberg, B.; Götherström, C.; Hassan, M.; Uzunel, M.; Ringdén, O. Treatment of Severe Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease with Third Party Haploidentical Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Lancet 2004, 363, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Blanc, K.; Frassoni, F.; Ball, L.; Locatelli, F.; Roelofs, H.; Lewis, I.; Lanino, E.; Sundberg, B.; Bernardo, M.E.; Remberger, M.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treatment of Steroid-Resistant, Severe, Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease: A Phase II Study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherukuri, A.; Mehta, R.; Sharma, A.; Sood, P.; Zeevi, A.; Tevar, A.D.; Rothstein, D.M.; Hariharan, S. Post-Transplant Donor Specific Antibody Is Associated with Poor Kidney Transplant Outcomes Only When Combined with Both T-Cell-Mediated Rejection and Non-Adherence. Kidney Int 2019, 96, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, K.; Rasmusson, I.; Sundberg, B.; Götherström, C.; Hassan, M.; Uzunel, M.; Ringdén, O. Treatment of Severe Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease with Third Party Haploidentical Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Lancet 2004, 363, 1439–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hao, J.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Y.G.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, L.; Wu, J. Current Status of Clinical Trials Assessing Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Graft versus Host Disease: A Systematic Review. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandil, R.K.; Dhup, S.; Narayanan, S. Evaluation of the Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in Preclinical Models of Autoimmune Diseases. Stem Cells Int 2022, 2022, 6379161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, D. de C.; Araújo, L.T. de; Santos, G.C.; Damasceno, P.K.F.; Vieira, J.L.; Santos, R.R. dos; Barbosa, J.D.V.; Soares, M.B.P. Clinical Trials with Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies for Osteoarthritis: Challenges in the Regeneration of Articular Cartilage. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, C.; Layios, N.; Lambermont, B.; Lechanteur, C.; Briquet, A.; Bettonville, V.; Baudoux, E.; Thys, M.; Dardenne, N.; Misset, B.; et al. Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Severe COVID-19: Preliminary Results of a Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 932360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, K. Le; Dazzi, F.; English, K.; Farge, D.; Galipeau, J.; Horwitz, E.M.; Kadri, N.; Krampera, M.; Lalu, M.M.; Nolta, J.; et al. ISCT MSC Committee Statement on the US FDA Approval of Allogenic Bone-Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cytotherapy 2025, 27, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemeda, H.; Jakob, M.; Ludwig, A.K.; Giebel, B.; Lang, S.; Brandau, S. Interferon-Gamma and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Differentially Affect Cytokine Expression and Migration Properties of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev 2010, 19, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrum, J.A.; Ong, J.F.; Karp, J.M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Immune Evasive, Not Immune Privileged. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Blanc, K.; Tammik, C.; Rosendahl, K.; Zetterberg, E.; Ringdén, O. HLA Expression and Immunologic Propertiesof Differentiated and Undifferentiated Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Exp Hematol 2003, 31, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Megen, K.M.; Van ’t Wout, E.J.T.; Motta, J.L.; Dekker, B.; Nikolic, T.; Roep, B.O. Activated Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Process and Present Antigens Regulating Adaptive Immunity. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvites, R.; Branquinho, M.; Sousa, A.C.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Maurício, A.C. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Their Paracrine Activity—Immunomodulation Mechanisms and How to Influence the Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.A.; Mcdevitt, T.C. Pre-Conditioning Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Spheroids for Immunomodulatory Paracrine Factor Secretion. Cytotherapy 2014, 16, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.X.; Mao, G.X.; Zhang, J.; Wen, X.L.; Jia, B.B.; Bao, Y.Z.; Lv, X.L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, G.F. IFN-γ Induces Senescence-like Characteristics in Mouse Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv Clin Exp Med 2017, 26, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.X.; Mao, G.X.; Zhang, J.; Wen, X.L.; Jia, B.B.; Bao, Y.Z.; Lv, X.L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, G.F. IFN-γ Induces Senescence-like Characteristics in Mouse Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv Clin Exp Med 2017, 26, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, H.; Ducret, M.; Degoul, O.; Rodriguez, J.; Perrier-Groult, E.; Aubert-Foucher, E.; Pasdeloup, M.; Auxenfans, C.; McGuckin, C.; Forraz, N.; et al. Characterization of Different Sources of Human MSCs Expanded in Serum-Free Conditions with Quantification of Chondrogenic Induction in 3D. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 2186728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, J.; Farreras, C.; Sánchez-Tilló, E.; Vico, T.; Guerrero-Gonzalez, P.; Fernandez-Elorduy, A.; Lloberas, J.; Celada, A. Induction of CIITA by IFN-γ in Macrophages Involves STAT1 Activation by JAK and JNK. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuçi, Z.; Piede, N.; Vogelsang, K.; Pfeffermann, L.M.; Wehner, S.; Salzmann-Manrique, E.; Stais, M.; Kreyenberg, H.; Bonig, H.; Bader, P.; et al. Expression of HLA-DR by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in the Platelet Lysate Era: An Obsolete Release Criterion for MSCs? J Transl Med 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, C.; Pérez-Simón, J.A. Immunomodulatory Effect of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2010, 43, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.M.; Barry, F.P.; Murphy, J.M.; Mahon, B.P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Avoid Allogeneic Rejection. J Inflamm (Lond) 2005, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, K.; Davies, L.C. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and the Innate Immune Response. Immunol Lett 2015, 168, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouroupis, D.; Kaplan, L.D.; Huard, J.; Best, T.M. CD10-Bound Human Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Possess Immunomodulatory Cargo and Maintain Cartilage Homeostasis under Inflammatory Conditions. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valledor, A.F.; Sánchez-Tilló, E.; Arpa, L.; Park, J.M.; Caelles, C.; Lloberas, J.; Celada, A. Selective Roles of MAPKs during the Macrophage Response to IFN-γ. The Journal of Immunology 2008, 180, 4523–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, V.; Rovetta, A.I.; Alvarez, I.B.; Jurado, J.O.; Musella, R.M.; Palmero, D.J.; Malbrán, A.; Samten, B.; Barnes, P.F.; García, V.E. Phosphorylation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Contributes to Interferon γ Production in Response to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2012, 207, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kaplan, M.H. The P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Is Required for IL-12-Induced IFN-γ Expression. The Journal of Immunology 2000, 165, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, D.R.; Seo, K.W.; Roh, K.H.; Jung, J.W.; Kang, S.K.; Kang, K.S. REX-1 Expression and P38 MAPK Activation Status Can Determine Proliferation/Differentiation Fates in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, N.P.; Martin, K.M.; Gudas, L.J. The Putative Human Stem Cell Marker, Rex-1 (Zfp42): Structural Classification and Expression in Normal Human Epithelial and Carcinoma Cell Cultures. Mol Carcinog 2006, 45, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, A.J.; Horng, T. IL-6 Strikes a Balance in Metabolic Inflammation. Cell Metab 2014, 19, 898–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atreya, R.; Mudter, J.; Finotto, S.; Müllberg, J.; Jostock, T.; Wirtz, S.; Schütz, M.; Bartsch, B.; Holtmann, M.; Becker, C.; et al. Blockade of Interleukin 6 Trans Signaling Suppresses T-Cell Resistance against Apoptosis in Chronic Intestinal Inflammation: Evidence in Crohn Disease and Experimental Colitis in Vivo. Nat Med 2000, 6, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Gauldie, J.; Cox, G.; Baumann, H.; Jordana, M.; Lei, X.F.; Achong, M.K. IL-6 Is an Antiinflammatory Cytokine Required for Controlling Local or Systemic Acute Inflammatory Responses. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1998, 101, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, A.; Huang, S.; Ding, G.; Pan, X.; Chen, R. Interleukin-13 Inhibits Cytokines Synthesis by Blocking Nuclear Factor-ΚB and c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase in Human Mesangial Cells. J Biomed Res 2010, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Hébert, M.C.; Zhang, Y.E. TGF-β Receptor-Activated P38 MAP Kinase Mediates Smad-Independent TGF-β Responses. EMBO Journal 2002, 21, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giarratana, A.O.; Prendergast, C.M.; Salvatore, M.M.; Capaccione, K.M. TGF-β Signaling: Critical Nexus of Fibrogenesis and Cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine 2024 22:1 2024, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatetti, F.; Maccario, R.; Frassoni, F. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells, from Indifferent Spectators to Principal Actors. Are We Going to Witness a Revolution in the Scenario of Allograft and Immune-Mediated Disorders? Haematologica 2007, 92, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallis, P.; Siorenta, A.; Stamathioudaki, E.; Vrani, V.; Paterakis, G. Frequency Distribution of HLA Class I and II Alleles in Greek Population and Their Significance in Orchestrating the National Donor Registry Program. Int J Immunogenet 2024, 51, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegert, D.G.; Muntoni, F.; Murru, M.R.; Costa, G.; Francis, G.S.; Marrosu, M.G. HLA-DQA1 and -DQB1 Associations with Multiple Sclerosis in Sardinia and French Canada: Evidence for Immunogenetically Distinct Patient Groups. Neurology 1993, 43, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrosu, M.G.; Murru, M.R.; Costa, G.; Murru, R.; Muntoni, F.; Cucca, F. DRB1-DQA1-DQB1 Loci and Multiple Sclerosis Predisposition in the Sardinian Population. Hum Mol Genet 1998, 7, 1235–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olerup, O.; Hillert, J. HLA Class II-associated Genetic Susceptibility in Multiple Sclerosis: A Critical Evaluation. Tissue Antigens 1991, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbach, J.A.; Oksenberg, J.R. The Immunogenetics of Multiple Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Review. J Autoimmun 2015, 64, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, I.; Papakonstantinou, S.; Bempes, V.; Vasiliadis, H.S.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Pelidou, S.H. HLA Associations with Multiple Sclerosis in Greece. J Neurol Sci 2011, 308, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wucherpfennig, K.W.; Catz, I.; Hausmann, S.; Strominger, J.L.; Steinman, L.; Warren, K.G. Recognition of the Immunodominant Myelin Basic Protein Peptide by Autoantibodies and HLA-DR2-Restricted T Cell Clones from Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Identity of Key Contact Residues in the B-Cell and T-Cell Epitopes. J Clin Invest 1997, 100, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pette, M.; Fujita, K.; Kitze, B.; Whitaker, J.N.; Albert, E.; Kappos, L.; Wekerle, H. Myelin Basic Protein-Specific T Lymphocyte Lines from MS Patients and Healthy Individuals. Neurology 1990, 40, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacini, G.; Ieronymaki, M.; Nuti, F.; Sabatino, G.; Larregola, M.; Aharoni, R.; Papini, A.M.; Rovero, P. Epitope Mapping of Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein (MOG) Antibodies in a Mouse Model of Multiple Sclerosis: Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of the Peptide Antigens and ELISA Screening. J Pept Sci 2016, 22, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcellos, L.F.; Sawcer, S.; Ramsay, P.P.; Baranzini, S.E.; Thomson, G.; Briggs, F.; Cree, B.C.A.; Begovich, A.B.; Villoslada, P.; Montalban, X.; et al. Heterogeneity at the HLA-DRB1 Locus and Risk for Multiple Sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 2006, 15, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyment, D.A.; Herrera, B.M.; Cader, M.Z.; Willer, C.J.; Lincoln, M.R.; Sadovnick, A.D.; Risch, N.; Ebers, G.C. Complex Interactions among MHC Haplotypes in Multiple Sclerosis: Susceptibility and Resistance. Hum Mol Genet 2005, 14, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezstarosti, S.; Erpicum, P.; Maggipinto, G.; Dreyer, G.J.; Reinders, M.E.J.; Meziyerh, S.; Roelen, D.L.; De Fijter, J.W.; Kers, J.; Weekers, L.; et al. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Kidney Transplantation: Should Repeated Human Leukocyte Antigen Mismatches Be Avoided? Front Genet 2024, 15, 1436194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittoraki, A.G.; Fylaktou, A.; Tarassi, K.; Tsinaris, Z.; Siorenta, A.; Petasis, G.C.; Gerogiannis, D.; Lehmann, C.; Carmagnat, M.; Doxiadis, I.; et al. Hidden Patterns of Anti-HLA Class I Alloreactivity Revealed Through Machine Learning. Front Immunol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallis, P.; Boulari, D.; Michalopoulos, E.; Dinou, A.; Spyropoulou-Vlachou, M.; Stavropoulos-Giokas, C. Evaluation of HLA-G Expression in Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Vitrified Wharton’s Jelly Tissue. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—a Multiple Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Location | Reverse Sequence | Location | Amplicon Size |

| REX1 | CCCTGGAATACGTCCCCAAG | 718-737 | CATCCTGTGAGGACTGGACC | 1227-1208 | 510 |

| OCT4 | GTGTTCAGCCAAAAGACCATCT | 532-553 | GGCCTGCATGAGGGTTTCT | 687-669 | 156 |

| KLF4 | CGGACATCAACGACGTGAG | 563-581 | GACGCCTTCAGCACGAACT | 701-683 | 139 |

| NANOG | TTTGTGGGCCTGAAGAAAACT | 83-103 | AGGGCTGTCCTGAATAAGCAG | 198-178 | 116 |

| GAPDH | GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT | 108-128 | GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG | 304-282 | 197 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).