Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemical Treatment and Development of Banana Microfiber

2.3. PLA and Banana Microfiber Composite Filament Making

2.4. 3D-Printing of Composite Filament

| Printing parameter or reinforcing parameter | Level | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Infill density (%) | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Raster Angle (°) | 0 | 45 | -45/+45 |

| Infill pattern | Rectilinear | Triangular | Honeycomb |

| Filler density (%) | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| Experiments | Infill density (%) | Raster Angle (°) | Infill pattern | Filler density (%) |

| Exp-1 | 50 | 0 | Gyroid | 3 |

| Exp-2 | 50 | 45 | Rectilinear | 6 |

| Exp-3 | 50 | +45/-45 | Honeycomb | 9 |

| Exp-4 | 75 | 0 | Rectilinear | 9 |

| Exp-5 | 75 | 45 | Honeycomb | 3 |

| Exp-6 | 75 | +45/-45 | Gyroid | 6 |

| Exp-7 | 100 | 0 | Honeycomb | 6 |

| Exp-8 | 100 | 45 | Gyroid | 9 |

| Exp-9 | 100 | +45/-45 | Rectilinear | 3 |

| Parameters | Units | Value |

| Nozzle size | mm | 0.4 |

| Shell thickness | mm | 0.4 |

| Top/bottom layer thickness | mm | 0.6 |

| Initial layer height | mm | 0.1 |

| Layer thickness | mm | 0.12 |

| Bed temperature | °C | 55 |

| Printing temperature | °C | 190 |

| Printing speed | mm/sec | 50 |

2.5. Characterisation of Treated and Untreated Banana Microfiber

2.6. Characterisation of Composite Filament

2.7. Characterization of 3D Printed Composites

2.8. Optimising Printing Parameters Using the MCDM Technique

2.8.1. Shannon Entropy Method

2.8.2. VIKOR Process

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Banana Microfiber

| Microfiber | Stage-I weight loss (%) | Stage-II weight loss (%) | Stage-III weight loss (%) | Stage-IV weight loss (%) | Residual mass (%) |

| Untreated Banana | 7.98 | 11.12 | 61.42 | 18.66 | 25.66 |

| Treated Banana | 1.16 | 11.03 | 52.83 | 11.05 | 36.91 |

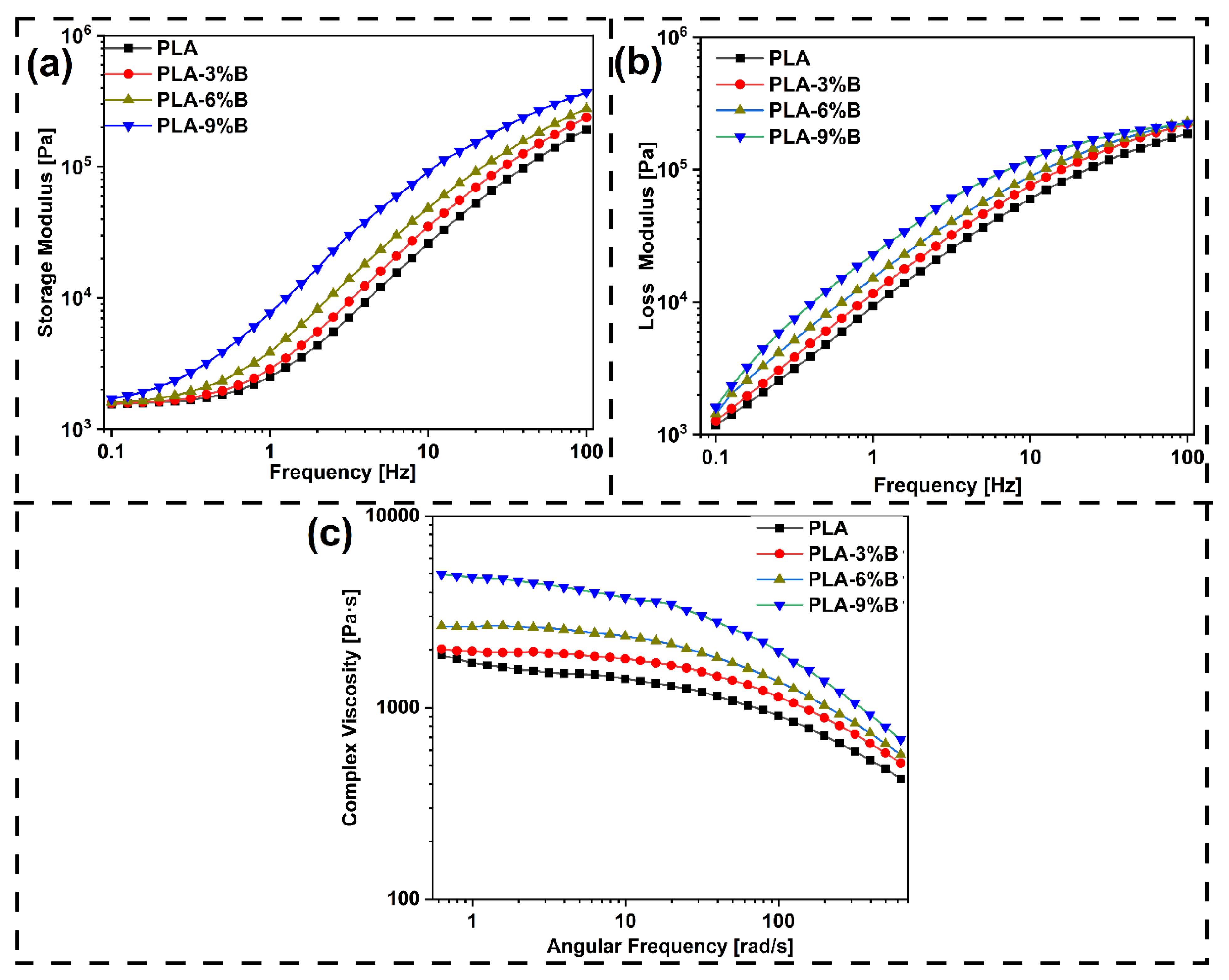

3.2. Characterization of Banana Microfiber Blend PLA Filament

| Banana microfiber (%) |

Tg (°C) |

TCC (°C) |

Tm (°C) |

Enthalpy (J/g) |

Crystallinity (%) |

| 0 | 58.99 | 116.21 | 155.01 | 9.31 | 10.02 |

| 3 | 62.92 | 116.47 | 154.26 | 9.41 | 10.47 |

| 6 | 65.97 | 116.78 | 153.25 | 9.89 | 11.32 |

| 9 | 67.99 | 117.02 | 152.10 | 10.26 | 12.13 |

| Filament type | η0 (Pa s) | σ0 (Pa) | n |

| Neat PLA | 1869 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| 3% Banana+PLA | 2010 | 0.35 | 0.40 |

| 6% Banana+PLA | 2719 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| 9% Banana+PLA | 3470 | 0.43 | 0.51 |

3.3. Characterization of 3D Printed Composite

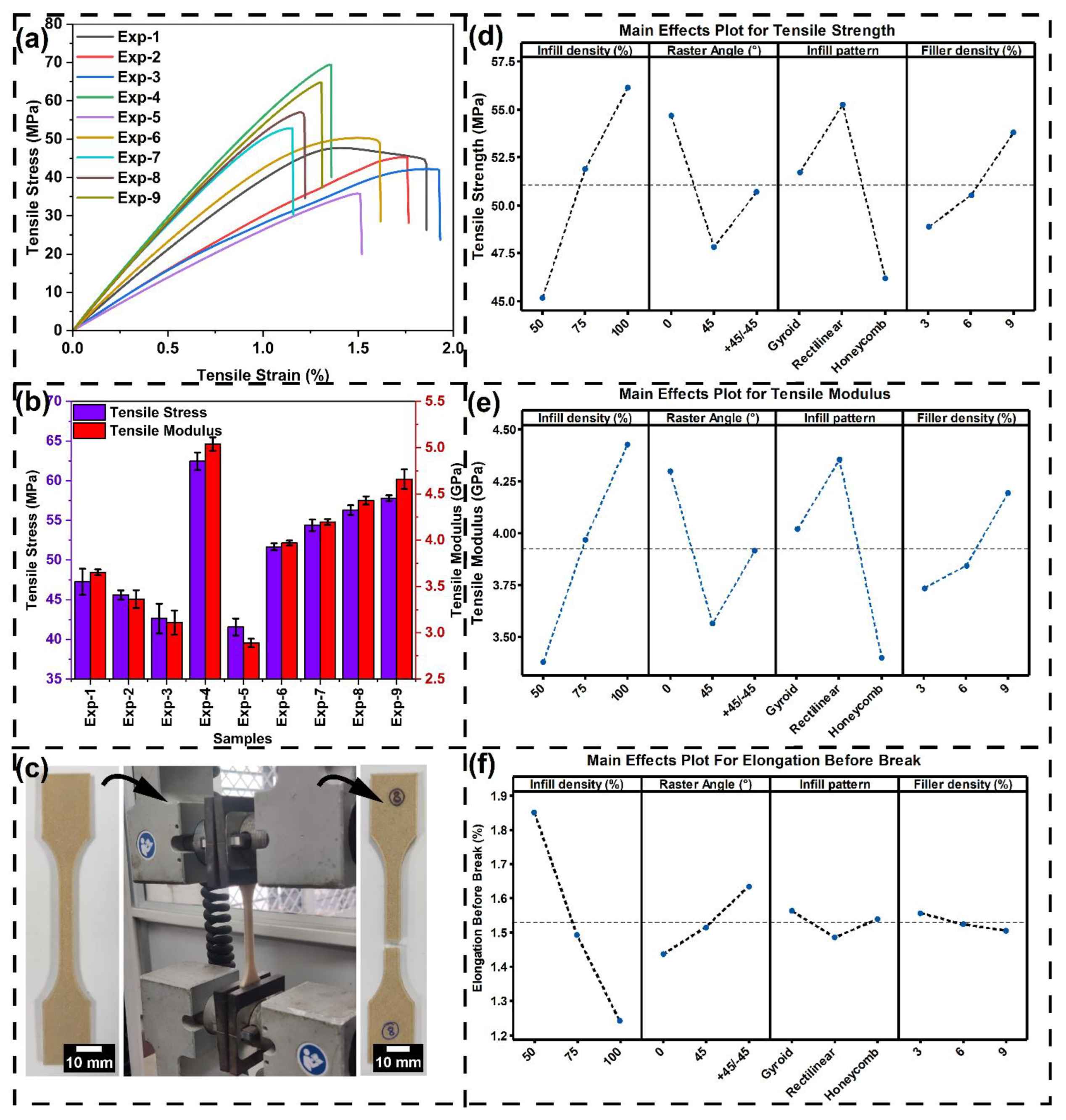

3.3.1. Tensile Testing

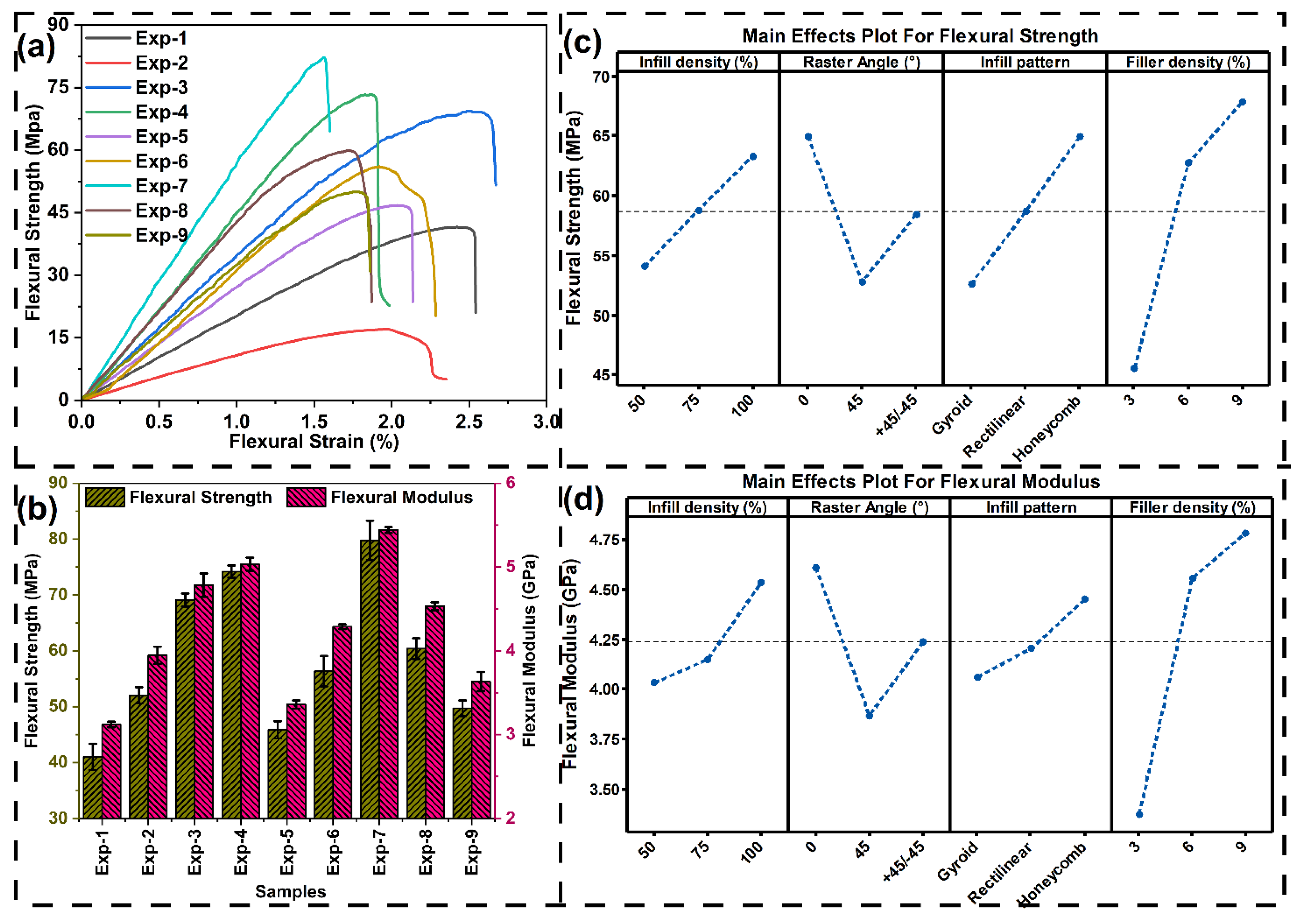

3.3.2. Flexural Testing

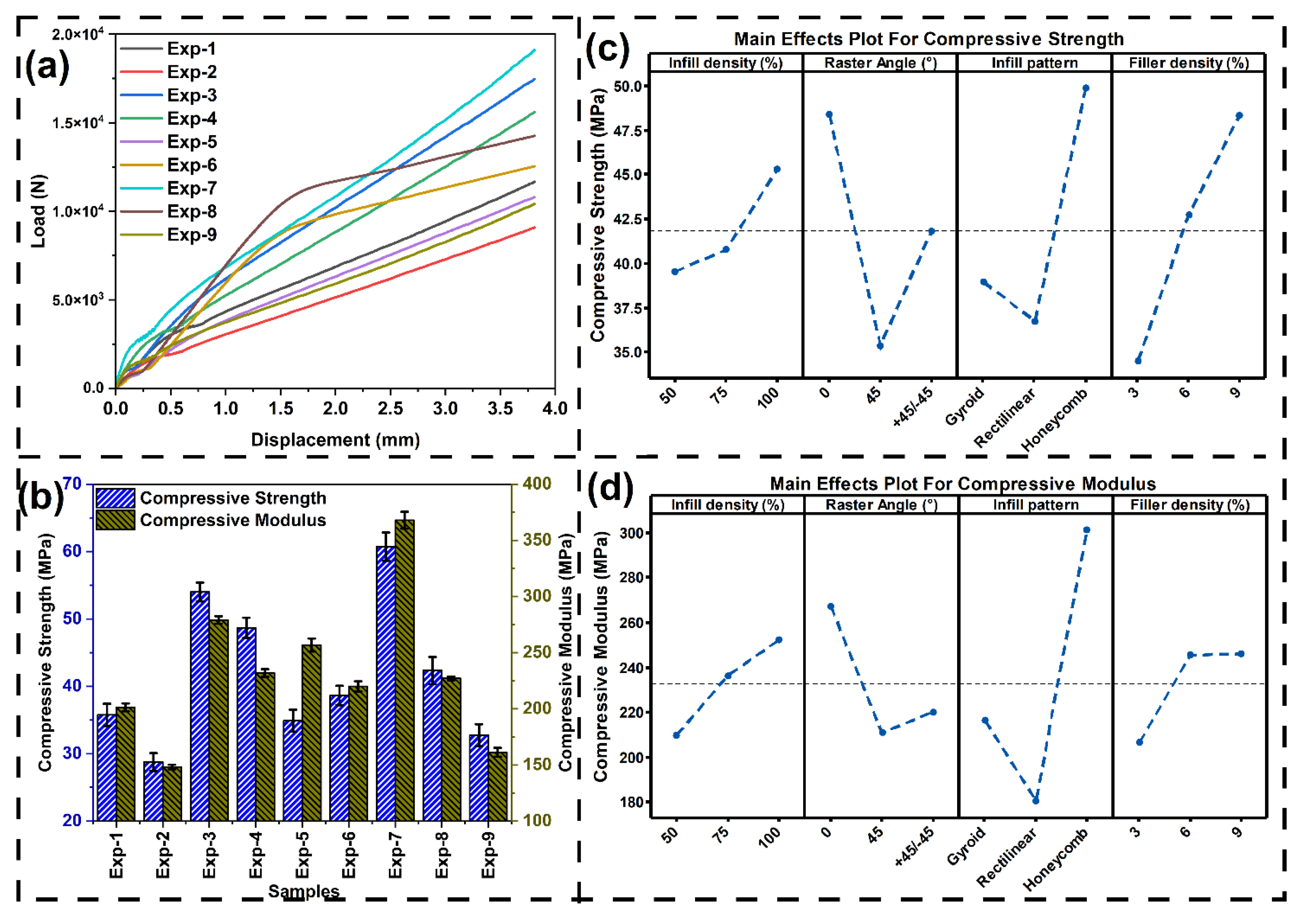

3.3.3. Compression testing

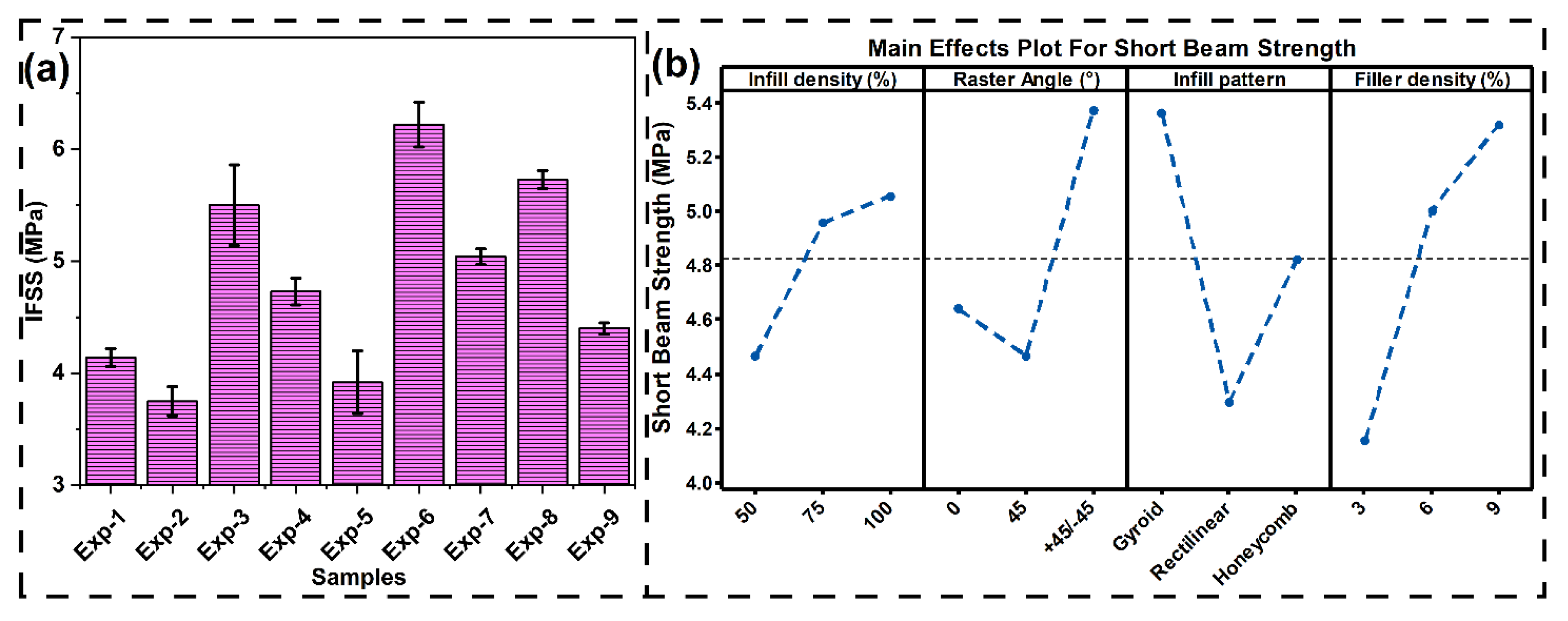

3.3.4. Short Beam Shear Testing

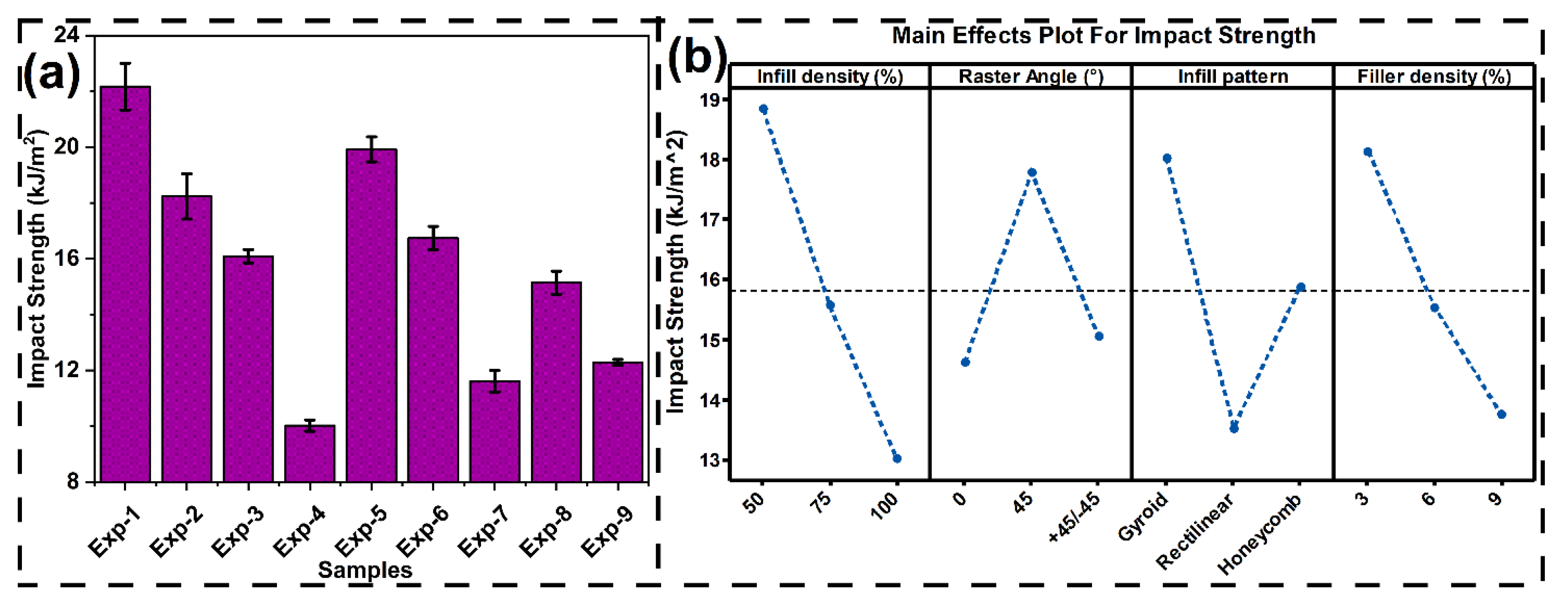

3.3.5. Impact Testing

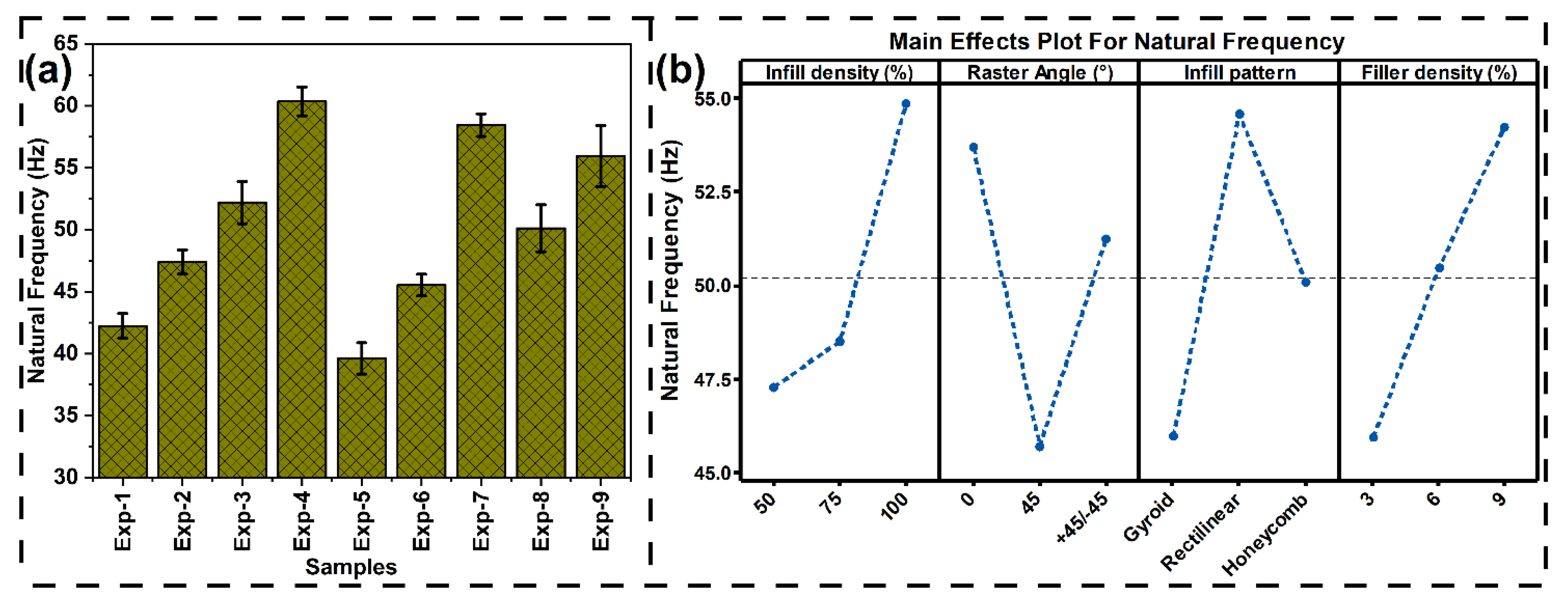

3.3.6. Natural Frequency Analysis

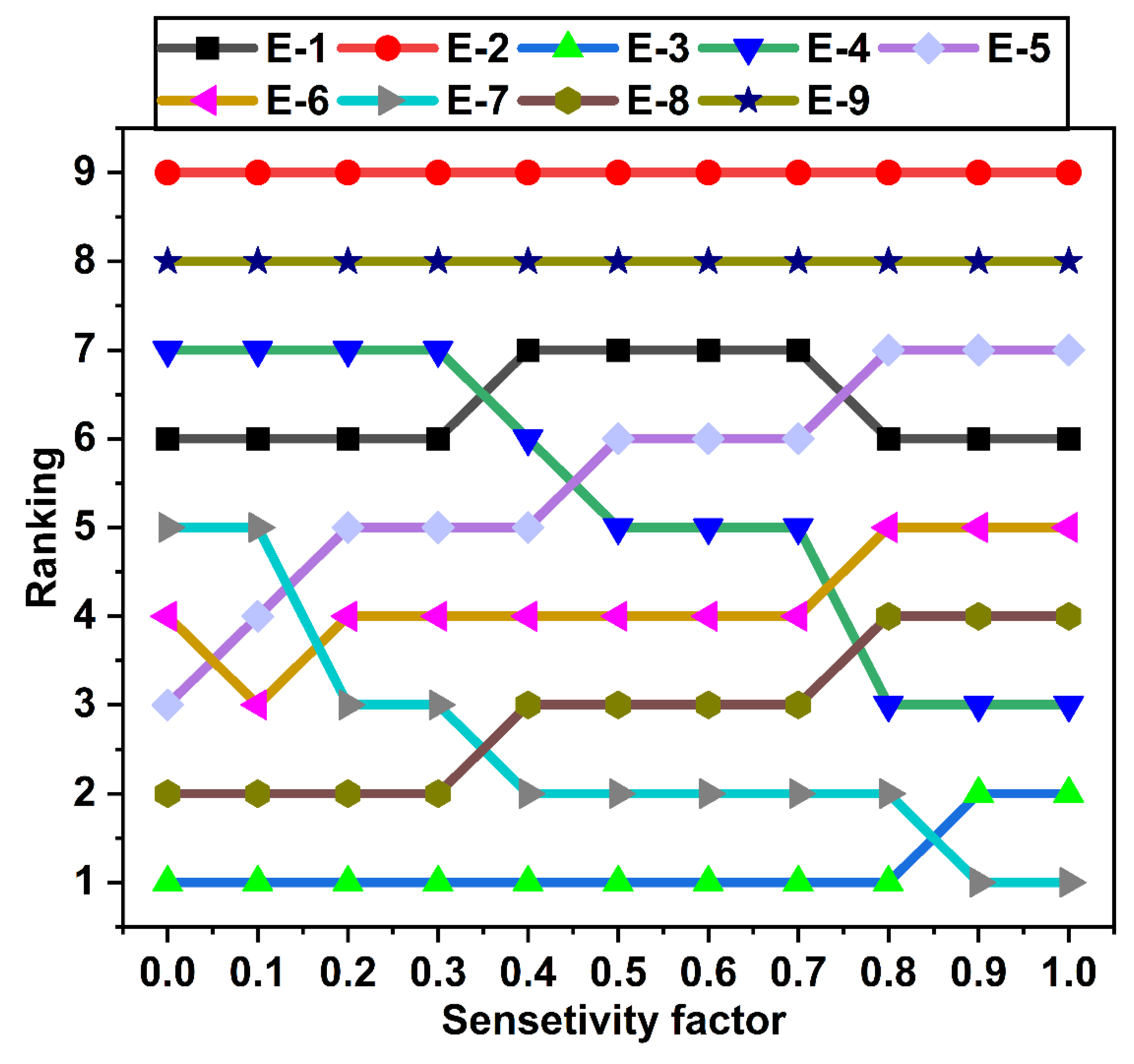

4. Optimisation of Printing Parameters Using VIKOR

| Criteria → | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 |

| Materials ↓ | Tensile Strength | Tensile Modulus | Elongation at break | Flexural Strength | Flexural Modulus | Compressive Strength | Compressive Modulus | IFSS | Impact Strength | Natural Frequency |

| (MPa) | (GPa) | (%) | (MPa) | (GPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (kJ/m2) | (Hz) | |

| E1 | 47.26 | 3.65 | 1.82 | 41.01 | 3.12 | 35.77 | 201.33 | 4.14 | 22.17 | 42.23 |

| E2 | 45.59 | 3.36 | 1.79 | 52.03 | 3.95 | 28.76 | 148.23 | 3.75 | 18.23 | 47.40 |

| E3 | 42.63 | 3.11 | 1.94 | 69.10 | 4.78 | 54.02 | 279.07 | 5.50 | 16.09 | 52.20 |

| E4 | 62.45 | 5.04 | 1.33 | 74.18 | 5.03 | 48.68 | 231.87 | 4.73 | 10.02 | 60.36 |

| E5 | 41.56 | 2.89 | 1.52 | 45.85 | 3.36 | 34.91 | 256.81 | 3.92 | 19.92 | 39.62 |

| E6 | 51.66 | 3.97 | 1.63 | 56.35 | 4.29 | 38.64 | 219.90 | 6.22 | 16.74 | 45.53 |

| E7 | 54.39 | 4.20 | 1.15 | 79.78 | 5.44 | 60.73 | 367.89 | 5.04 | 11.61 | 58.44 |

| E8 | 56.31 | 4.43 | 1.24 | 60.38 | 4.53 | 42.34 | 227.13 | 5.73 | 15.14 | 50.11 |

| E9 | 57.79 | 4.66 | 1.33 | 49.71 | 3.63 | 32.75 | 161.25 | 4.40 | 12.29 | 55.94 |

| Criteria → | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 |

| Weightage → | 0.0460 | 0.0793 | 0.0778 | 0.1155 | 0.0793 | 0.1430 | 0.1908 | 0.0720 | 0.1488 | 0.0471 |

5. Conclusion

- The chemical treatment of banana fiber increases the crystallinity index of the lignocellulose fiber. Introduction of banana microfiber into the PLA matrix for composite filament enhances glass transition temperature (Tg), there are minor differences in cold crystalline temperature (Tcc), and a declining trend is observed with melting temperature (Tm) for composite filament in comparison with virgin PLA filament.

- Addition of Banana fiber into PLA matrix increases the value of storage modulus, loss modulus and complex viscosity. The flow behaviour index (n) value for composite filaments is found to be less than one, making it suitable for 3D printing.

- An increase in the proportion of banana microfiber within the filament increases stiffness and load-carrying capacity, leading to greater tensile, flexural, compressive, and interfacial shear strength and modulus. But brittleness was also enhanced, resulting in a decrease in elongation at break and lower impact strength of the printed composite.

- An increase in infill density decreases the internal voids and enhances the load distribution, therefore enhancing tensile, flexural, and compression strengths. Increased stiffness resulting from increased density, however, decreased the impact energy absorption capacity of the material to a limited degree.

- Specimens fabricated using a 45° raster angle had greater impact strength owing to the inclined filament path, permitting shear deformation and energy absorption during loading cycles. 0° and ±45° orientations, on the other hand, favoured tensile and flexural strength by orienting the filaments more orthogonally in the direction of the load path.

- The bioinspired gyroid architecture had the greatest impact strength owing to its continuous and curved nature, which serves to dissipate energy effectively. Honeycomb and rectilinear structures offered greater stiffness and strength but had lower energy absorption capacity under impact loading conditions.

- Multi-decision criteria, VIKOR, conclude the experimental condition E3 (50% infill density, with ±45° raster angle, honeycomb infill pattern and 9% banana microfiber loading) as the most effective printing condition to achieve overall better mechanical properties.

- Addition of banana fiber, an agro waste reduces the overall cost of the composite materials. For PLA-banana fiber composite the major cost comes from PLA. As the addition of banana fiber into PLA decreases the overall cost of materials and make the composite more affordable. Not only that most common biodegradability mechanism of materials depends on the moister sensitivity of the material. Addition of biomass make the composite hydrophilic, accelerated the rate of biodegradation.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Wang Y, Sultana J, Rahman MM, Ahmed A, Azam A, Mushtaq RT, et al. A Sustainable and Biodegradable Building Block: Review on Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fibre Reinforced PLA Polymer Composites and Their Emerging Applications. Fibers and Polymers 2022;23:3317–42. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran Royan NR, Leong JS, Chan WN, Tan JR, Shamsuddin ZSB. Current state and challenges of natural fibre-reinforced polymer composites as feeder in fdm-based 3d printing. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Kartal, Fuat, and Arslan Kaptan. Response of PLA material to 3D printing speeds: A comprehensive examination on mechanical properties and production quality. European Mechanical Science 8, no. 3 (2024): 137-144.

- Montalvo Navarrete JI, Hidalgo-Salazar MA, Escobar Nunez E, Rojas Arciniegas AJ. Thermal and mechanical behavior of biocomposites using additive manufacturing. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing 2018;12:449–58. [CrossRef]

- Leon-Becerra J, González-Estrada OA, Sánchez-Acevedo H. Comparison of Models to Predict Mechanical Properties of FR-AM Composites and a Fractographical Study. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- León-Becerra J, González-Estrada OA, Quiroga J. Effect of Relative Density in In-Plane Mechanical Properties of Common 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Lattice Structures. ACS Omega 2021;6:29830–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Ge J, Yu X, Li H. Environmental fate and impacts of microplastics in soil ecosystems: Progress and perspective. Science of the Total Environment 2020;708. [CrossRef]

- Arif ZU, Khalid MY, Sheikh MF, Zolfagharian A, Bodaghi M. Biopolymeric sustainable materials and their emerging applications. J Environ Chem Eng 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Kopparthy SDS, Netravali AN. Review: Green composites for structural applications. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021;6. [CrossRef]

- Petković B, Agdas AS, Zandi Y, Nikolić I, Denić N, Radenkovic SD, et al. Neuro fuzzy evaluation of circular economy based on waste generation, recycling, renewable energy, biomass and soil pollution. Rhizosphere 2021;19. [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa PR, Senthil Kumar P, Karishma S. Review on biopolymers and composites – Evolving material as adsorbents in removal of environmental pollutants. Environ Res 2022;212. [CrossRef]

- Natural Fiber Composite Market Size, Share and Trends_2025-2030. n.d.

- Barbhuiya S, Bhusan Das B, Kanavaris F. Biochar-concrete: A comprehensive review of properties, production and sustainability. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024;20. [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya S, Bhusan Das B, Kanavaris F. Biochar-concrete: A comprehensive review of properties, production and sustainability. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024;20. [CrossRef]

- Sathish Kumar RK, Sasikumar R, Dhilipkumar T. Exploiting agro-waste for cleaner production: A review focusing on biofuel generation, bio-composite production, and environmental considerations. J Clean Prod 2024;435. [CrossRef]

- Uppal N, Pappu A, Gowri VKS, Thakur VK. Cellulosic fibres-based epoxy composites: From bioresources to a circular economy. Ind Crops Prod 2022;182. [CrossRef]

- Maseko KH, Regnier T, Meiring B, Wokadala OC, Anyasi TA. Musa species variation, production, and the application of its processed flour: A review. Sci Hortic 2024;325. [CrossRef]

- Scott GJ. A review of root, tuber and banana crops in developing countries: past, present and future. Int J Food Sci Technol 2021;56:1093–114. [CrossRef]

- Garlotta D. A Literature Review of Poly(Lactic Acid). vol. 9. 2001.

- Joseph TM, Kallingal A, Suresh AM, Mahapatra DK, Hasanin MS, Haponiuk J, et al. 3D printing of polylactic acid: recent advances and opportunities. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023;125:1015–35. [CrossRef]

- Selvam A, Mayilswamy S, Whenish R. Strength Improvement of Additive Manufacturing Components by Reinforcing Carbon Fiber and by Employing Bioinspired Interlock Sutures. Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology 2020;26:511–23. [CrossRef]

- Yiga VA, Lubwama M, Pagel S, Benz J, Olupot PW, Bonten C. Flame retardancy and thermal stability of agricultural residue fiber-reinforced polylactic acid: A Review. Polym Compos 2021;42:15–44. [CrossRef]

- Yiga VA, Lubwama M, Pagel S, Benz J, Olupot PW, Bonten C. Flame retardancy and thermal stability of agricultural residue fiber-reinforced polylactic acid: A Review. Polym Compos 2021;42:15–44. [CrossRef]

- Zini E, Scandola M. Green composites: An overview. Polym Compos 2011;32:1905–15. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Shafeer PP, Pitchaimani J, Doddamani M. A short banana fiber—PLA filament for 3D printing: Development and characterization. Polym Compos 2025;46:4863–80. [CrossRef]

- Komal UK, Lila MK, Singh I. PLA/banana fiber based sustainable biocomposites: A manufacturing perspective. Compos B Eng 2020;180. [CrossRef]

- Shih YF, Huang CC. Polylactic acid (PLA)/banana fiber (BF) biodegradable green composites. Journal of Polymer Research 2011;18:2335–40. [CrossRef]

- Nazrin A, Sapuan SM, Zuhri MYM. Mechanical, physical and thermal properties of sugar palm nanocellulose reinforced thermoplastic starch (Tps)/poly (lactic acid) (pla) blend bionanocomposites. Polymers (Basel) 2020;12:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Suryanegara L, Yano H. Manufacture of Nanocomposites Based On Microfibrillated Cellulose and Polylactic Acid. 2015.

- Satriyatama A, Rochman VAA, Adhi RE. Study of the Effect of Glycerol Plasticizer on the Properties of PLA/Wheat Bran Polymer Blends. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2021;1143:012020. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Shafeer PP, Pitchaimani J, Doddamani M. A short banana fiber—PLA filament for 3D printing: Development and characterization. Polym Compos 2025;46:4863–80. [CrossRef]

- Stoof D, Pickering K, Zhang Y. Fused deposition modelling of natural fibre/polylactic acid composites. Journal of Composites Science 2017;1. [CrossRef]

- Felix Sahayaraj A, Muthukrishnan M, Ramesh M. Experimental investigation on physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of jute and hemp fibers reinforced hybrid polylactic acid composites. Polym Compos 2022;43:2854–63. [CrossRef]

- Ye G, Li Z, Chen B, Bai X, Chen X, Hu Y. Performance of polylactic acid/polycaprolactone/microcrystalline cellulose biocomposites with different filler contents and maleic anhydride compatibilization. Polym Compos 2022;43:5179–88. [CrossRef]

- Wasti S, Triggs E, Farag R, Auad M, Adhikari S, Bajwa D, et al. Influence of plasticizers on thermal and mechanical properties of biocomposite filaments made from lignin and polylactic acid for 3D printing. Compos B Eng 2021;205. [CrossRef]

- Tao Y, Wang H, Li Z, Li P, Shi SQ. Development and application ofwood flour-filled polylactic acid composite filament for 3d printing. Materials 2017;10. [CrossRef]

- Suteja J, Firmanto H, Soesanti A, Christian C. Properties investigation of 3D printed continuous pineapple leaf fiber-reinforced PLA composite. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2022;35:2052–61. [CrossRef]

- Vigneshwaran K, Venkateshwaran N. Statistical analysis of mechanical properties of wood-PLA composites prepared via additive manufacturing. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization 2019;24:584–96. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad ND, Kusmono, Wildan MW, Herianto. Preparation and properties of cellulose nanocrystals-reinforced Poly (lactic acid) composite filaments for 3D printing applications. Results in Engineering 2023;17. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Singh R, Singh TP, Batish A. Investigations of polylactic acid reinforced composite feedstock filaments for multimaterial three-dimensional printing applications. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci 2019;233:5953–65. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud MZ Al, Rabbi SMF, Islam MD, Hossain N. Synthesis and applications of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composites: A comprehensive review. SPE Polymers 2025;6. [CrossRef]

- Arunprasath K, Senthamaraikannan P, Suyambulingam I, Akash S, Karthic S, Vimal Chanth M, et al. Comprehensive review of advances in natural fiber composites for conductive and EMI shielding applications: Materials, mechanisms, and future prospects. Int J Biol Macromol 2025;320. [CrossRef]

- He Q, Tang T, Zeng Y, Iradukunda N, Bethers B, Li X, et al. Review on 3D Printing of Bioinspired Structures for Surface/Interface Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2024;34. [CrossRef]

- Siddique SH, Hazell PJ, Wang H, Escobedo JP, Ameri AAH. Lessons from nature: 3D printed bio-inspired porous structures for impact energy absorption – A review. Addit Manuf 2022;58. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Yang X, Li P, Huang G, Feng S, Shen C, et al. Bioinspired engineering of honeycomb structure - Using nature to inspire human innovation. Prog Mater Sci 2015;74:332–400. [CrossRef]

- Helms M, Vattam SS, Goel AK. Biologically inspired design: process and products. Des Stud 2009;30:606–22. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda fiber-micro particle reinforced hybrid green composite: A sustainable solution for tomorrow’s challenges in construction and building engineering. Constr Build Mater 2024;441. [CrossRef]

- Bagla A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P, Saha A. Development and Characterization of a Sustainable Bamboo-Polyvinylidene Fluoride Electro Spun Piezoelectric Nanogenerator Device for Smart Health Monitoring. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2025;7:5584–97. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Graphene nanoplatelets/organic wood dust hybrid composites: physical, mechanical and thermal characterization. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2021;30:935–51. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Utilization of coconut shell biomass residue to develop sustainable biocomposites and characterize the physical, mechanical, thermal, and water absorption properties. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024;14:12815–31. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumari P. Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites. Polym Compos 2023;44:2449–73. [CrossRef]

- Hassan M, Mohanty AK, Misra M. Additive Manufacturing of a Super Toughened Biodegradable Polymer Blend: Structure-Property-Processing Correlation and 3D Printed Prosthetic Part Development. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024;6:3849–63. [CrossRef]

- Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics 2014. [CrossRef]

- Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials 2015. [CrossRef]

- International A, indexed by mero files. Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties Of Rigid Cellular Plastics 1. n.d.

- International A, indexed by mero files. Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Adhesive Bonded Laminated Assemblies 1. n.d.

- Test Methods for Determining the Izod Pendulum Impact Resistance of Plastics 2010. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda-reinforced different biopolymer matrix green composites and MCDM-based sustainable material selection for automobile applications. Environ Dev Sustain 2025;27:10655–91. [CrossRef]

- Kumar M, Kulkarni ND, Saha A, Kumari P. Using multi-criteria decision-making approach for material alternatives in TiO2/P(VDF-TrFE)/PDMS based hybrid nanogenerator as a wearable device. Sens Actuators A Phys 2024;372. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni ND, Saha A, Kumari P. Utilizing multicriteria decision-making approach for material selection in hybrid polymer nanocomposites for energy-harvesting applications. Polym Compos 2024;45:6264–77. [CrossRef]

- Liu HC, You JX, You XY, Shan MM. A novel approach for failure mode and effects analysis using combination weighting and fuzzy VIKOR method. Applied Soft Computing Journal 2015;28:579–88. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumari P. Functional fibers from Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) and their potential for reinforcing biocomposites. Mater Today Commun 2022;31. [CrossRef]

- Lila MK, Komal UK, Singh Y, Singh I. Extraction and Characterization of Munja Fibers and Its Potential in the Biocomposites. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:2675–93. [CrossRef]

- Komal UK, Lila MK, Singh I. Processing of PLA/pineapple fiber based next generation composites. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2021;36:1677–92. [CrossRef]

- Das A, Gilmer EL, Biria S, Bortner MJ. Importance of Polymer Rheology on Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Correlating Process Physics to Print Properties. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2021;3:1218–49. [CrossRef]

- Gao X, Qi S, Kuang X, Su Y, Li J, Wang D. Fused filament fabrication of polymer materials: A review of interlayer bond. Addit Manuf 2021;37. [CrossRef]

- Bertolino M, Battegazzore D, Arrigo R, Frache A. Designing 3D printable polypropylene: Material and process optimisation through rheology. Addit Manuf 2021;40. [CrossRef]

- Bertolino M, Battegazzore D, Arrigo R, Frache A. Designing 3D printable polypropylene: Material and process optimisation through rheology. Addit Manuf 2021;40. [CrossRef]

- Veeman D, Palaniyappan S. Process optimisation on the compressive strength property for the 3D printing of PLA/almond shell composite. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2023;36:2435–58. [CrossRef]

- Aboelella MG, Ebeid SJ, Sayed MM. Layer combination of similar infill patterns on the tensile and compression behavior of 3D printed PLA. Sci Rep 2025;15. [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanasambandam A, Packkirisamy V, Narayanaswamy N, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S, Kechagias JD. Influence of infill patterns on the mechanical and antibacterial properties of 3D-printed polylactic acid reinforced with hydroxyapatite/magnesium oxide bone repair scaffolds. Emergent Mater 2025. [CrossRef]

- Goshtasbi A, Grignaffini L, Sadeghi A. Bio-inspired 3D printing approach for bonding soft and rigid materials through underextrusion. Sci Rep 2025;15. [CrossRef]

- Podroužek J, Marcon M, Ninčević K, Wan-Wendner R. Bio-inspired 3D infill patterns for additive manufacturing and structural applications. Materials 2019;12. [CrossRef]

- Silva C, Pais AI, Caldas G, Gouveia BPPA, Alves JL, Belinha J. Study on 3D printing of gyroid-based structures for superior structural behaviour. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2021;6:689–703. [CrossRef]

- Cañero-Nieto JM, Campo-Campo RJ, Díaz-Bolaño I, Ariza-Echeverri EA, Deluque-Toro CE, Solano-Martos JF. Infill pattern strategy impact on the cross-sectional area at gauge length of material extrusion 3D printed polylactic acid parts. J Intell Manuf 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cañero-Nieto JM, Campo-Campo RJ, Díaz-Bolaño I, Ariza-Echeverri EA, Deluque-Toro CE, Solano-Martos JF. Infill pattern strategy impact on the cross-sectional area at gauge length of material extrusion 3D printed polylactic acid parts. J Intell Manuf 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Tian W, Zhang T, Chen P, Li M. Strength and toughness enhancement in 3d printing via bioinspired tool path. Mater Des 2020;185. [CrossRef]

- Naik M, Thakur DG. Experimental investigation of effect of printing parameters on impact strength of the bio-inspired 3D printed specimen n.d.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).