Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Materials

2.2. Chemical Treatment and Development of Wood Micro Particles

2.3. Development of Wood-PLA Biocomposite Filament

2.4. 3D Printing of Wood-PLA Biocomposite Filament

| Printing parameter or reinforcing parameter | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Infill pattern | Rectilinear | Gyroid | Honeycomb |

| Infill density (%) | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Printing temperature (°C) | 180 | 190 | 200 |

| Printing speed (mm/sec) | 40 | 50 | 60 |

| Experiments | Infill pattern | Infill density (%) |

Printing temperature (°C) | Printing speed (mm/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRC-1 | Rectilinear | 50 | 180 | 40 |

| PRC-2 | Rectilinear | 75 | 190 | 50 |

| PRC-3 | Rectilinear | 100 | 200 | 60 |

| PRC-4 | Hexagon | 50 | 190 | 60 |

| PRC-5 | Hexagon | 75 | 200 | 40 |

| PRC-6 | Hexagon | 100 | 180 | 50 |

| PRC-7 | Gyroid | 50 | 200 | 50 |

| PRC-8 | Gyroid | 75 | 180 | 60 |

| PRC-9 | Gyroid | 100 | 190 | 40 |

| Parameters | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle size | mm | 0.4 |

| Shell thickness | mm | 0.4 |

| Top/bottom layer thickness | mm | 0.6 |

| Initial layer height | mm | 0.1 |

| Layer thickness | mm | 0.12 |

| Bed temperature | °C | 55 |

| Raster angle | (°) | 0 |

2.5. Characterization of Wood Microparticles

2.6. Characterization of Wood-PLA Wood Filament

2.7. Characterization of Wood-PLA 3D Printed Sample

2.8. Optimization of 3D Printed Parameters Using MCDM Technique

2.8.1. Shannon Entropy Method

2.8.2. TODIM Method

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Wood

3.2. Characterization of Developed Wood-PLA Filament

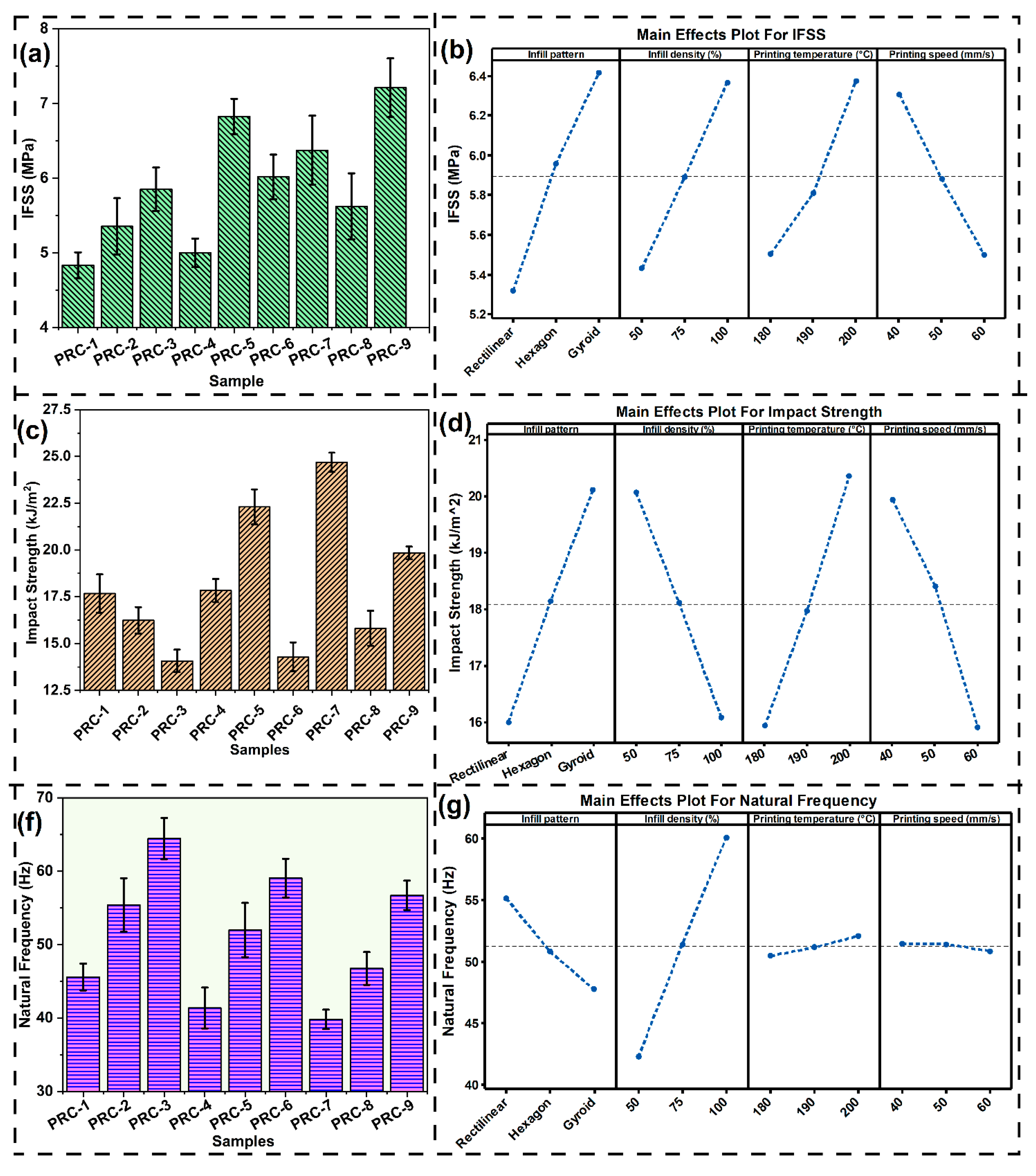

3.3. Mechanical Characterization of Wood-PLA 3D Printed Composite

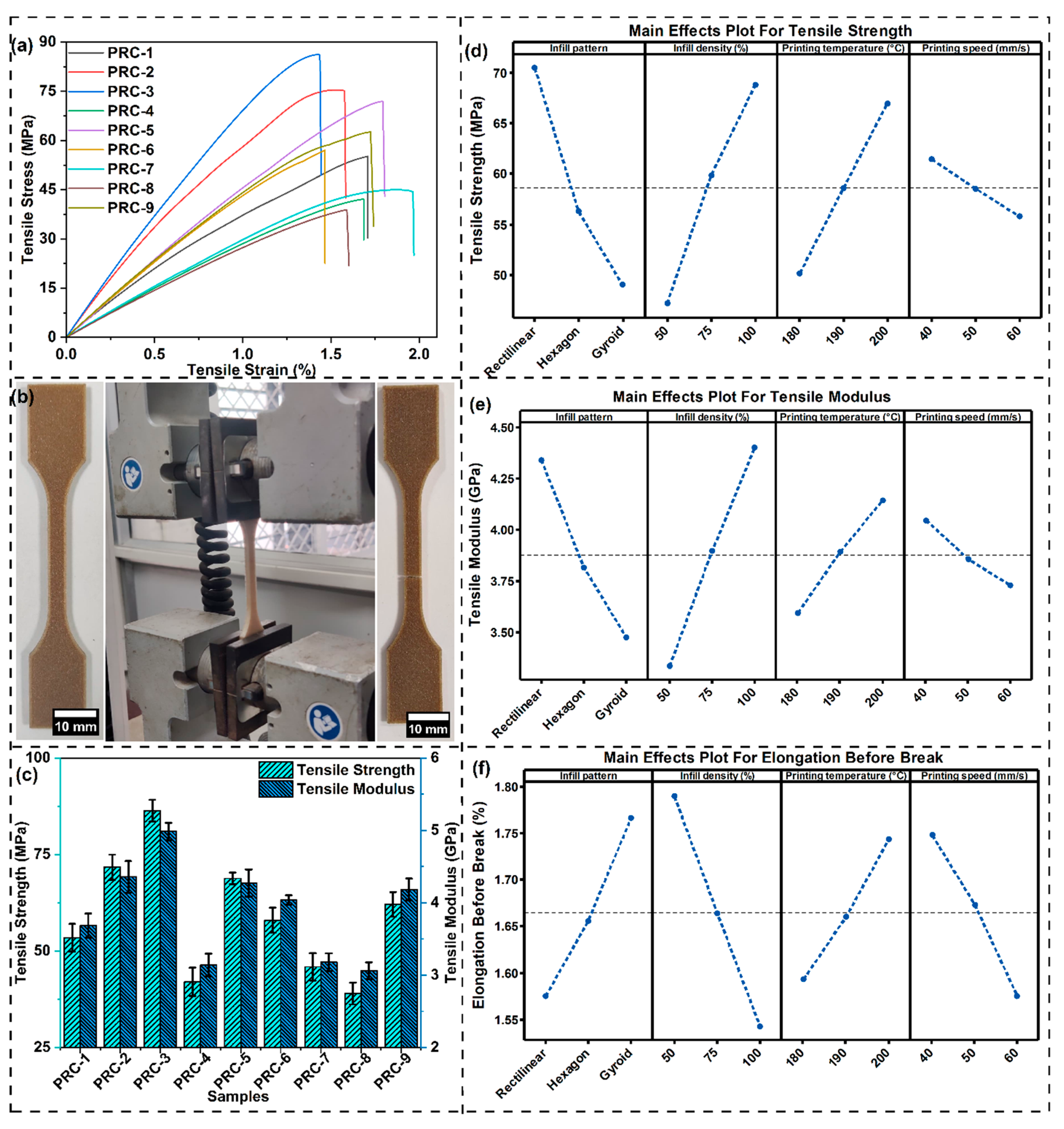

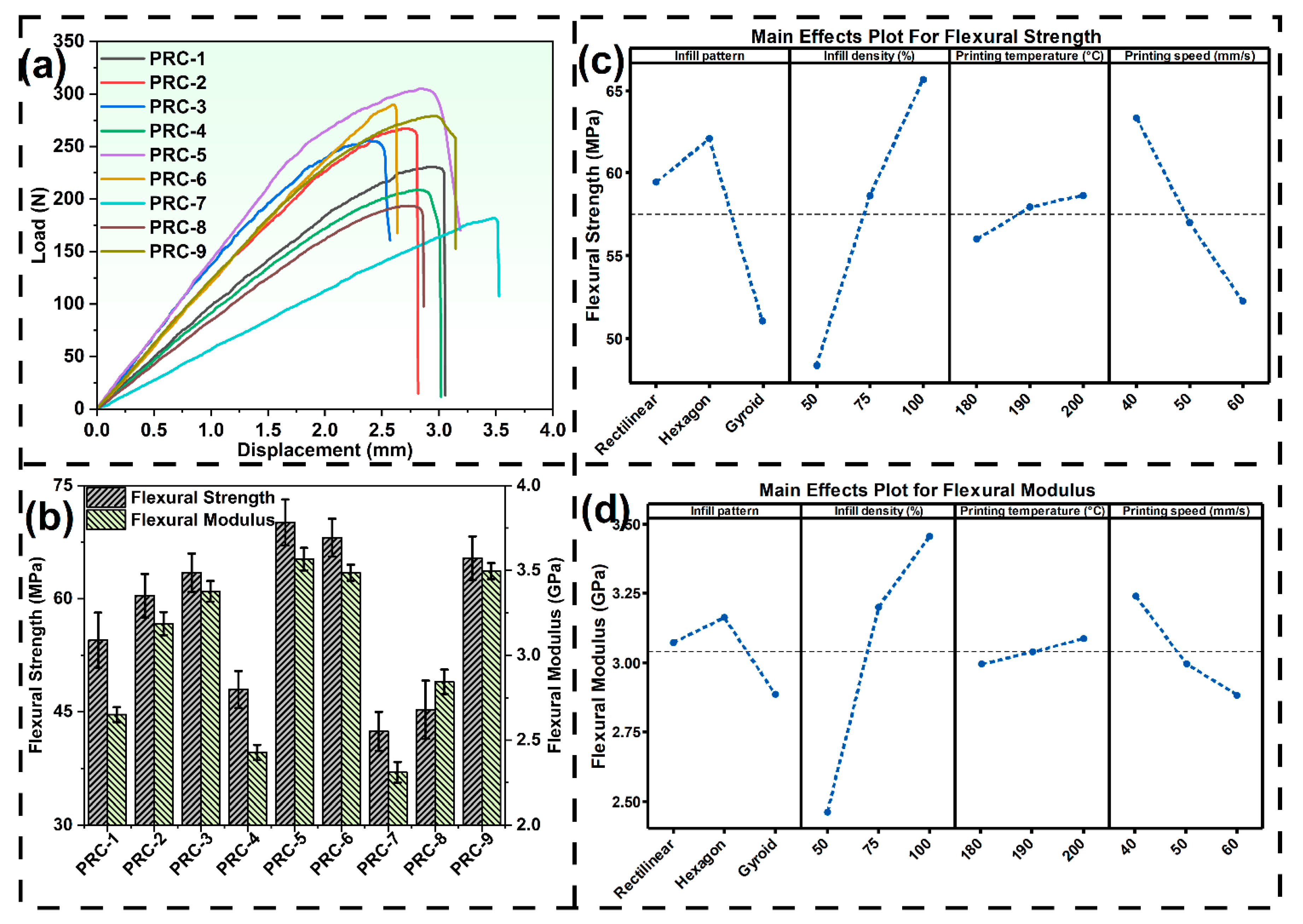

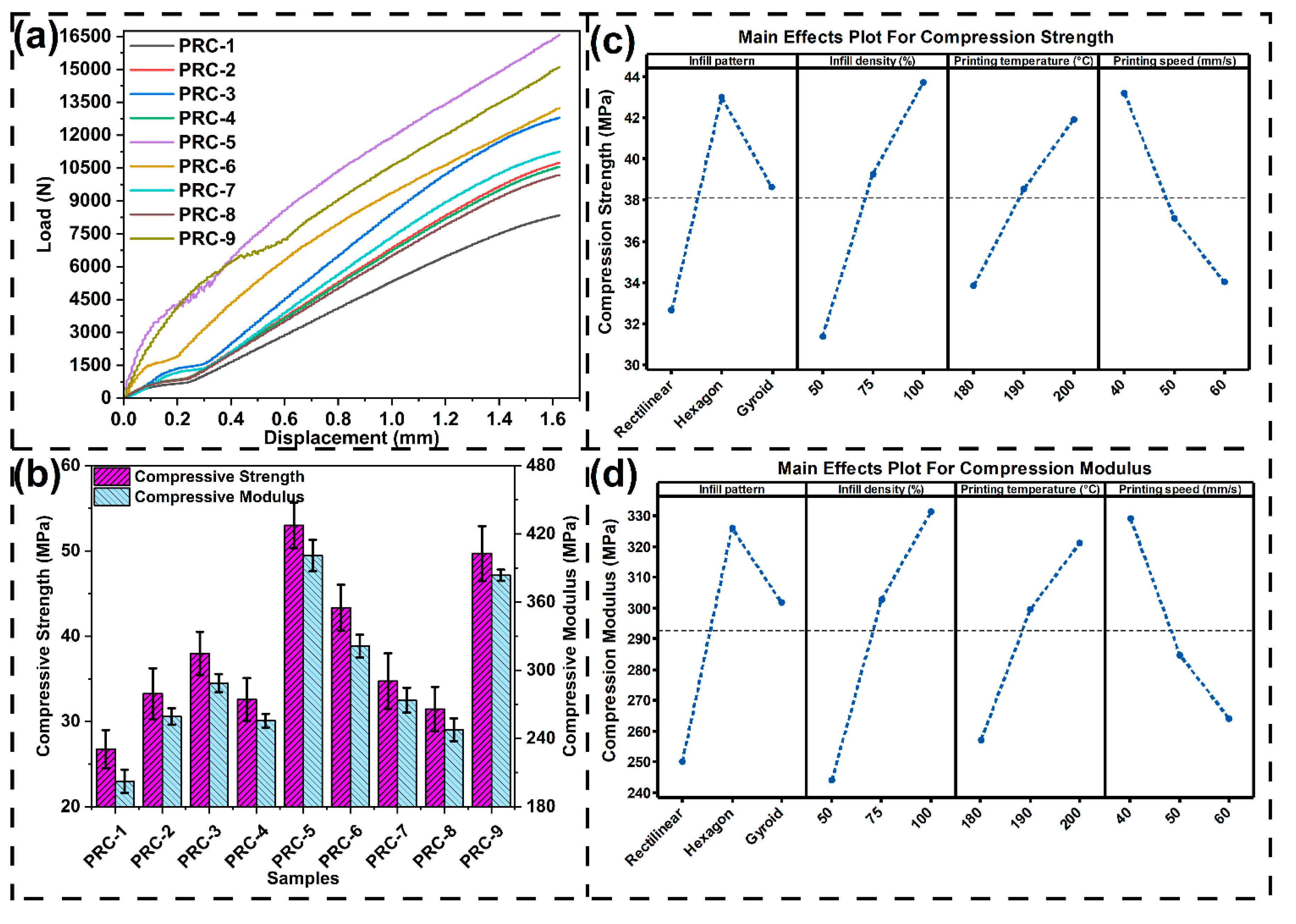

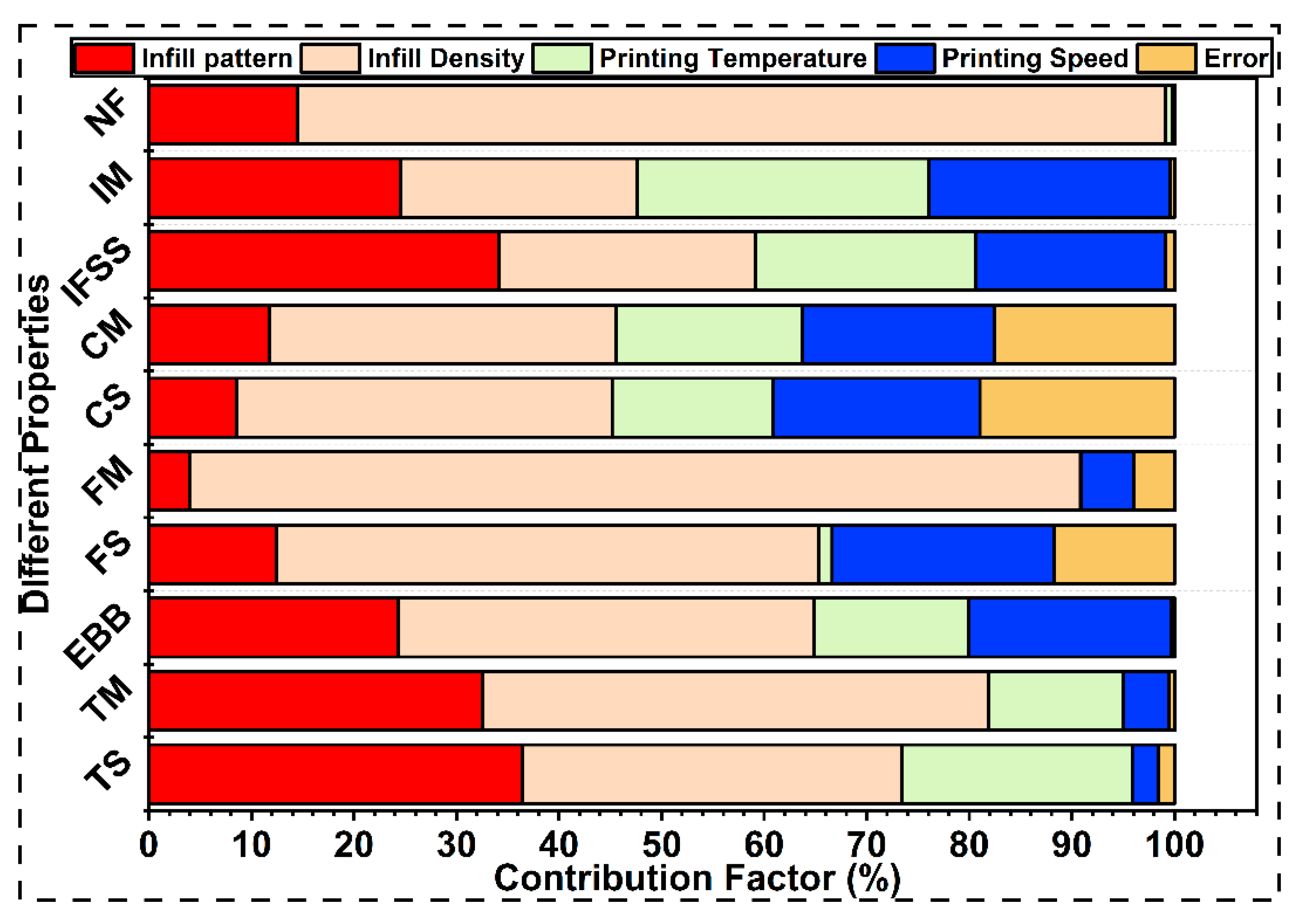

3.3.1. Effect of Infill Pattern on Different Mechanical Properties

3.3.2. Effect of Infill Density on Different Mechanical Properties

3.3.3. Effect of Printing Temperature on Different Mechanical Properties

3.3.4. Effect of Printing Speed on Different Mechanical Properties

3.3.5. Cumulative Effect of Different Printing Parameters and Regression Analysis

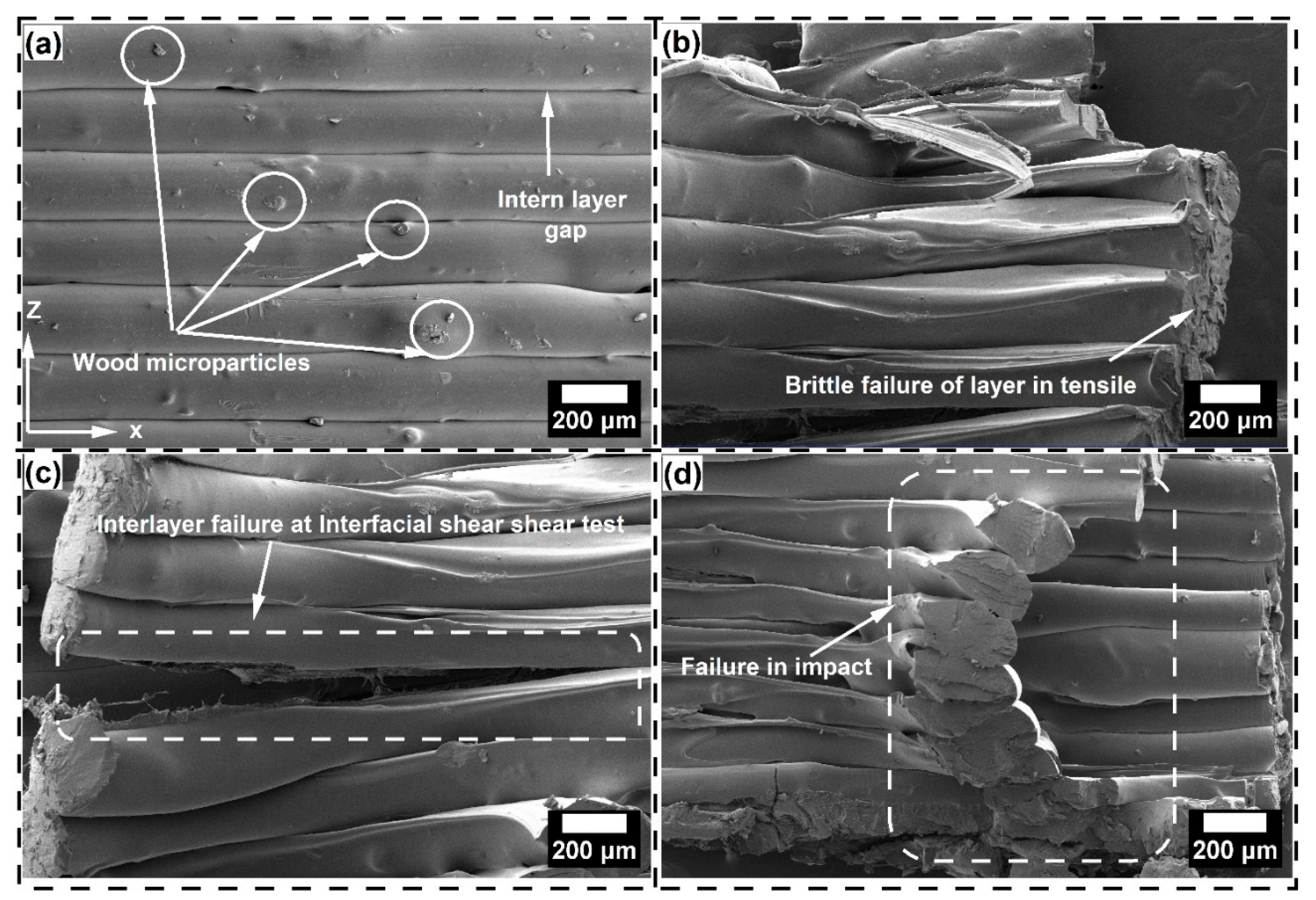

3.3.6. Surface Morphology of 3d Printed Tested Sample

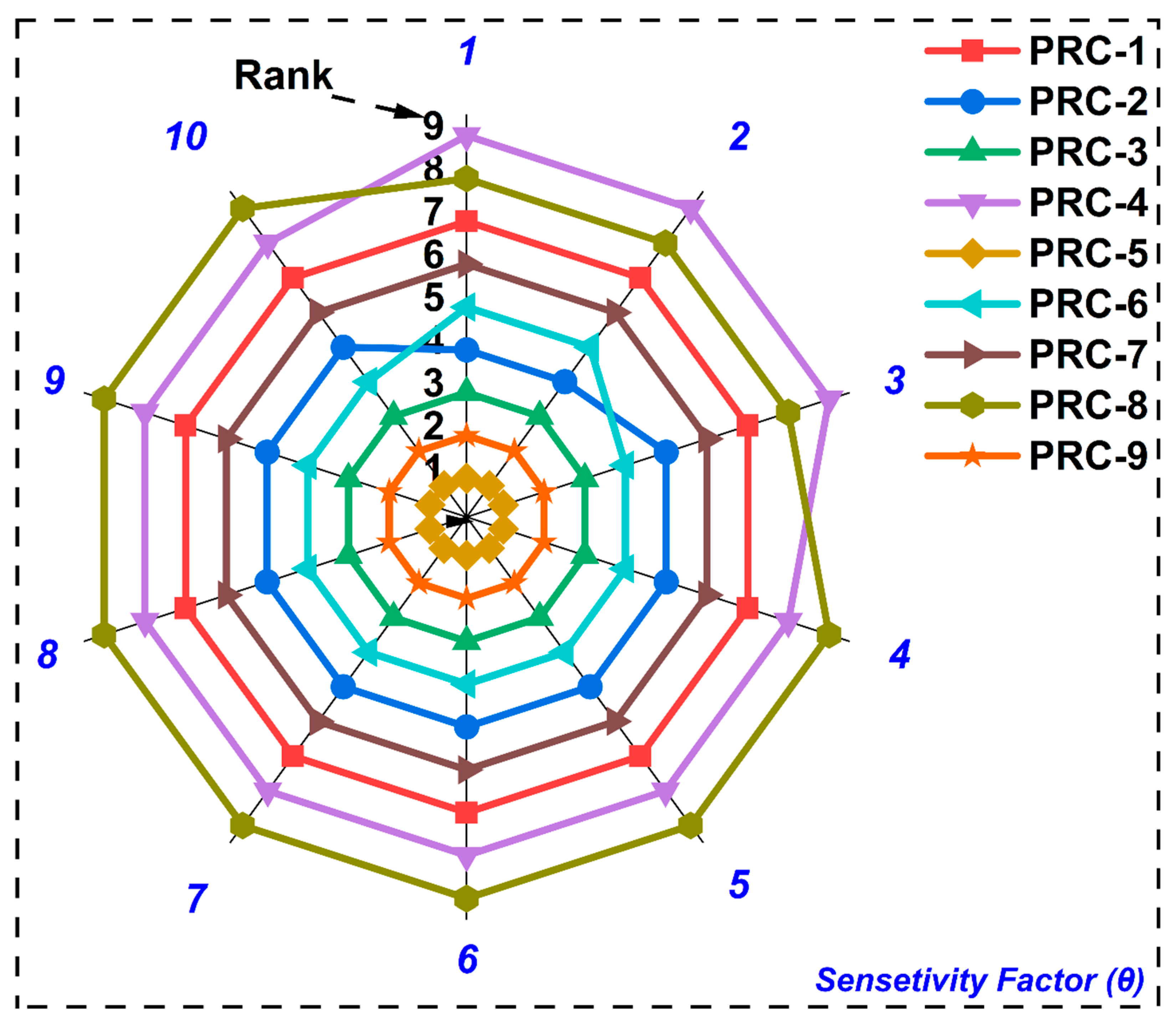

4. MCDM Based Optimization of Different Printing Parameters

5. Conclusion

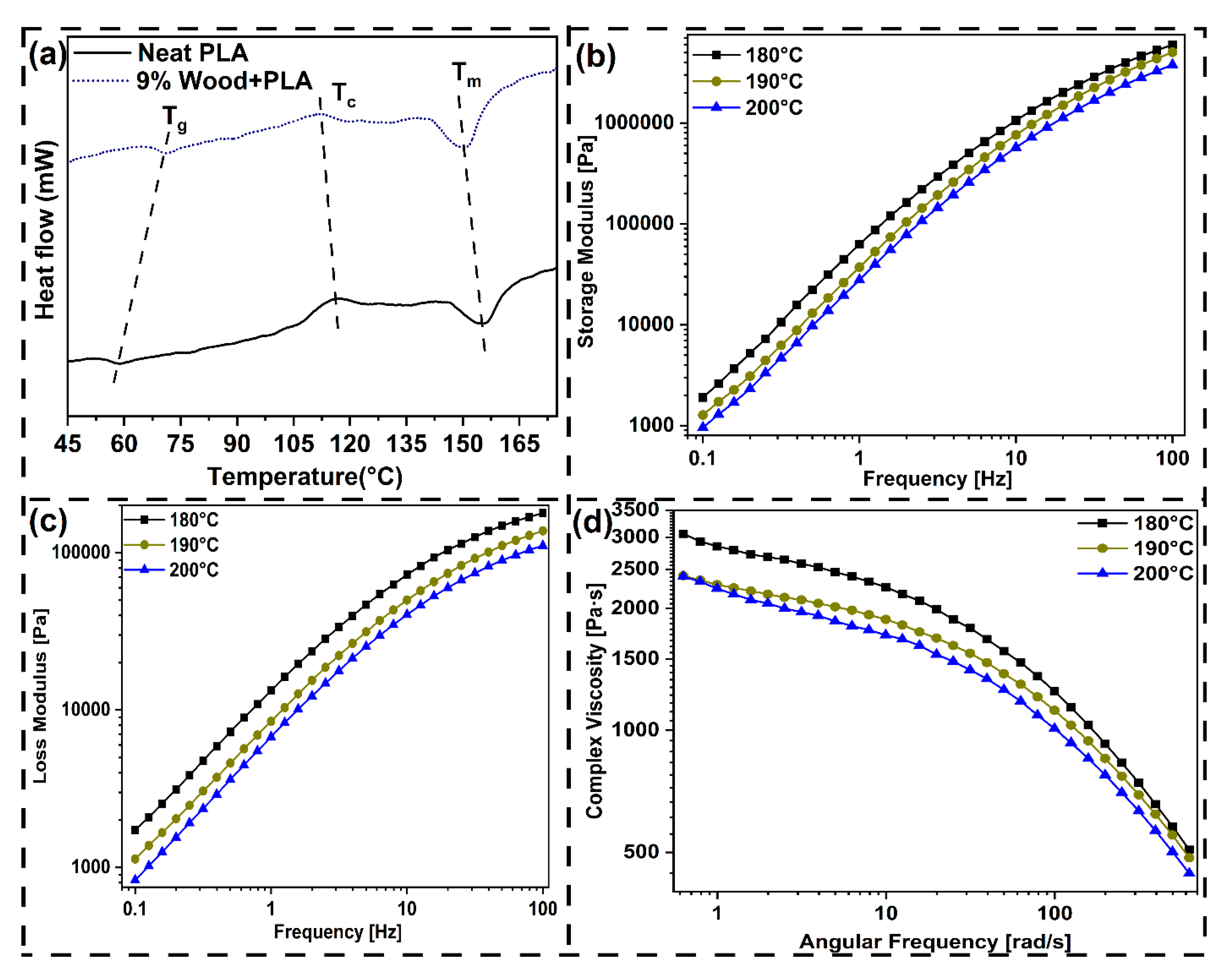

- Alkali treatment of wood microparticles enhanced the crystallinity index by removing hemicellulose and extractive component from the wood, and thus their compatibility with the PLA matrix increased. Addition of wood microparticles to PLA raised the glass transition temperature (Tg), decrease the cold crystallization temperature (Tcc), and exhibited a declining trend in melting temperature (Tm) with respect to virgin PLA.

- Increasing the printing temperature, decrease the storage modulus, loss modulus, and complex viscosity of the composite filaments. The flow behaviour index (n) was still below 1, reaffirming shear-thinning behaviour conducive to extrusion-based 3D printing.

- Increasing infill density minimised internal porosity and enhanced load transfer, thereby enhancing tensile, flexural, and compressive strengths. But the concomitant increase in stiffness slightly decreased the impact energy absorption capability of the material.

- The gyroid infill pattern had the greatest impact resistance due to its smooth and curved shape that allowed effective energy dissipation. Honeycomb infill pattern exhibited excellent compressive strength and rectilinear patterns had better stiffness and strength but relatively lower capacity for impact absorption.

- Increasing in printing temperature, improved mechanical strength and stiffness due to enhanced interlayer bonding, better fiber–matrix wetting, and reduced voids; however, temperatures beyond the optimal range may cause polymer degradation and fiber damage, leading to property deterioration.

- Increased print speed led to reduced mechanical properties since high-speed deposition lowers polymer chain diffusion time, reduces interlayer bonding, and promotes void formation; as a result, strength and modulus reduce relative to specimens printed at reduced speeds.

- The multi-criteria decision-making using the TODIM method identified condition PRC-5 (hexagon infill pattern with 75% infill density, 200°C printing temperature and 40mm/sec printing speed) as the most promising combination for achieving balanced and improved mechanical performance.

- The use of wood micro particles, an agro/industrial waste product, minimized the total cost of the composite because PLA is still the major expense. Moreover, the hydrophilic character of the biomass favours moisture absorption, thus enhancing the biodegradation process and the environmental friendliness of wood/PLA composites.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgement

References

- Montalvo Navarrete JI, Hidalgo-Salazar MA, Escobar Nunez E, Rojas Arciniegas AJ. Thermal and mechanical behavior of biocomposites using additive manufacturing. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing 2018;12:449–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-017-0411-2. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Sultana J, Rahman MM, Ahmed A, Azam A, Mushtaq RT, et al. A Sustainable and Biodegradable Building Block: Review on Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fibre Reinforced PLA Polymer Composites and Their Emerging Applications. Fibers and Polymers 2022;23:3317–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-022-4871-z. [CrossRef]

- Veeman D, Sai MS, Sureshkumar P, Jagadeesha T, Natrayan L, Ravichandran M, et al. Additive Manufacturing of Biopolymers for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: An Overview, Potential Applications, Advancements, and Trends. Int J Polym Sci 2021;2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4907027. [CrossRef]

- Leon-Becerra J, González-Estrada OA, Sánchez-Acevedo H. Comparison of Models to Predict Mechanical Properties of FR-AM Composites and a Fractographical Study. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14173546. [CrossRef]

- Ree BJ. Critical review and perspectives on recent progresses in 3D printing processes, materials, and applications. Polymer (Guildf) 2024;308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127384. [CrossRef]

- Cheng P, Peng Y, Wang K, Le Duigou A, Ahzi S. 3D printing continuous natural fiber reinforced polymer composites: A review. Polym Adv Technol 2024;35. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.6242. [CrossRef]

- Bi X, Huang R. 3D printing of natural fiber and composites: A state-of-the-art review. Mater Des 2022;222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111065. [CrossRef]

- Ecker JV, Kracalik M, Hild S, Haider A. 3D - Material Extrusion - Printing with Biopolymers: A Review. Chemical and Materials Engineering 2017;5:83–96. https://doi.org/10.13189/cme.2017.050402. [CrossRef]

- Arif MF, Alhashmi H, Varadarajan KM, Koo JH, Hart AJ, Kumar S. Multifunctional performance of carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets reinforced PEEK composites enabled via FFF additive manufacturing. Compos B Eng 2020;184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107625. [CrossRef]

- Hanon MM, Alshammas Y, Zsidai L. Effect of print orientation and bronze existence on tribological and mechanical properties of 3D-printed bronze/PLA composite. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2020;108:553–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-020-05391-x. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui MAS, Rabbi MS, Ahmed RU, Billah MM. Biodegradable natural polymers and fibers for 3D printing: A holistic perspective on processing, characterization, and advanced applications. Cleaner Materials 2024;14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2024.100275. [CrossRef]

- Gyawali B, Haghnazar R, Akula P, Alba K, Nasir V. A review on 3D printing with clay and sawdust/natural fibers: Printability, rheology, properties, and applications. Results in Engineering 2024;24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103024. [CrossRef]

- Balla VK, Tadimeti JGD, Sudan K, Satyavolu J, Kate KH. First report on fabrication and characterization of soybean hull fiber: polymer composite filaments for fused filament fabrication. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2021;6:39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-020-00138-2. [CrossRef]

- Bhagia S, Lowden RR, Erdman D, Rodriguez M, Haga BA, Solano IRM, et al. Tensile properties of 3D-printed wood-filled PLA materials using poplar trees. Appl Mater Today 2020;21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100832. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli G, Lamberti P, Tucci V, Kotsilkova R, Ivanov E, Menseidov D, et al. Nanocarbon/poly(lactic) acid for 3D printing: Effect of fillers content on electromagnetic and thermal properties. Materials 2019;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12152369. [CrossRef]

- Müller M, Šleger V, Kolář V, Hromasová M, Piš D, Mishra RK. Low-Cycle Fatigue Behavior of 3D-Printed PLA Reinforced with Natural Filler. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14071301. [CrossRef]

- Jahan I, Zhang G, Bhuiyan M, Navaratnam S. Circular Economy of Construction and Demolition Wood Waste—A Theoretical Framework Approach. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710478. [CrossRef]

- David G-M, Druță R-M, Nan L-M, Bacali L. CIRCULARITY PRACTICES RELATED TO THE RECYCLING OF WOOD WASTE FROM INDUSTRIAL PROCESSES: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE. vol. 22. 2023.

- Ferede E. Evaluation of mechanical and water absorption properties of alkaline-treated sawdust-reinforced polypropylene composite. Journal of Engineering (United Kingdom) 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3706176. [CrossRef]

- Gomes RM, Gonçalves Tibiriçá AC, Franco de Carvalho JM, Nalon GH, Pedroti LG, Oliveira de Paula M. Wood waste quantification from the furniture industry in Ubá (Brazil) and its reuse prospects in civil construction. Front Built Environ 2025;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2025.1623281. [CrossRef]

- Tümer EH, Erbil HY. Extrusion-based 3d printing applications of pla composites: A review. Coatings 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11040390. [CrossRef]

- Chawla VK, Seshasayee V, Yadav R. Sustainable Development of Particle Board from Lignocellulosic Agri Waste (Corchorus capsularis-Jute). Agricultural Science Digest - A Research Journal 2023. https://doi.org/10.18805/ag.d-5585. [CrossRef]

- Vigneshwaran K, Venkateshwaran N, Shanthi R, Kannan G, Kumar BR, Shanmugam V, et al. The acoustic properties of FDM printed wood/PLA-based composites. Composites Part C: Open Access 2024;15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2024.100532. [CrossRef]

- Faidallah RF, Abd-El Nabi AM, Hanon MM, Szakál Z, Oldal I. Compressive and bending properties of 3D-printed wood/PLA composites with Re-entrant honeycomb core. Results in Engineering 2024;24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103023. [CrossRef]

- Sultana J, Rahman MM, Wang Y, Ahmed A, Xiaohu C. Influences of 3D printing parameters on the mechanical properties of wood PLA filament: an experimental analysis by Taguchi method. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2024;9:1239–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-023-00516-6. [CrossRef]

- Krapež Tomec D, Schwarzkopf M, Repič R, Žigon J, Gospodarič B, Kariž M. Effect of thermal modification of wood particles for wood-PLA composites on properties of filaments, 3D-printed parts and injection moulded parts. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2024;82:403–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-023-02018-2. [CrossRef]

- Brackett J, Cauthen D, Condon J, Smith T, Gallego N, Kunc V, et al. The impact of infill percentage and layer height in small-scale material extrusion on porosity and tensile properties. Addit Manuf 2022;58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.103063. [CrossRef]

- Kesavarma S, Kong CK, Samykano M, Kadirgama K, Pandey AK. Bending properties of 3D printed coconut wood-PLA composite. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng, vol. 736, Institute of Physics Publishing; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/736/5/052031. [CrossRef]

- Hikmat M, Rostam S, Ahmed YM. Investigation of tensile property-based Taguchi method of PLA parts fabricated by FDM 3D printing technology. Results in Engineering 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2021.100264. [CrossRef]

- Fischer D, Eßbach C, Schönherr R, Dietrich D, Nickel D. Improving inner structure and properties of additive manufactured amorphous plastic parts: The effects of extrusion nozzle diameter and layer height. Addit Manuf 2022;51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102596. [CrossRef]

- Butt J, Bhaskar R, Mohaghegh V. Analysing the effects of layer heights and line widths on FFF-printed thermoplastics. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022;121:7383–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-09810-z. [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi MS, Elsayed AE. How Surface Roughness Performance of Printed Parts Manufactured by Desktop FDM 3D Printer with PLA+ is Influenced by Measuring Direction. American Journal of Mechanical Engineering 2017;5:211–22. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajme-5-5-4. [CrossRef]

- Frunzaverde D, Cojocaru V, Bacescu N, Ciubotariu CR, Miclosina CO, Turiac RR, et al. The Influence of the Layer Height and the Filament Color on the Dimensional Accuracy and the Tensile Strength of FDM-Printed PLA Specimens. Polymers (Basel) 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15102377. [CrossRef]

- Zharylkassyn B, Perveen A, Talamona D. Effect of process parameters and materials on the dimensional accuracy of FDM parts. Mater Today Proc, vol. 44, Elsevier Ltd; 2021, p. 1307–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.332. [CrossRef]

- Nabavi-Kivi A, Ayatollahi MR, Rezaeian P, Razavi N. Investigating the effect of printing speed and mode mixity on the fracture behavior of FDM-ABS specimens. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2022;118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2021.103223. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal KM, Shubham P, Bhatia D, Sharma P, Vaid H, Vajpeyi R. Analyzing the Impact of Print Parameters on Dimensional Variation of ABS specimens printed using Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM). Sensors International 2022;3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100149. [CrossRef]

- Yang TC, Yeh CH. Morphology and mechanical properties of 3D printed wood fiber/polylactic acid composite parts using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM): The effects of printing speed. Polymers (Basel) 2020;12:1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM12061334. [CrossRef]

- Bhayana M, Singh J, Sharma A, Gupta M. A review on optimized FDM 3D printed Wood/PLA bio composite material characteristics. Mater Today Proc 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.029. [CrossRef]

- BioRes_16_3_5467_Narlioglu_SA_3D_printed_Wood_PLA_Composite_Pine_Sawdust_18907 n.d.

- Baiamonte M, Rapisarda M, Mistretta MC, Impallomeni G, La Mantia FP, Rizzarelli P. Wood flour and hazelnut shells polylactide-based biocomposites for packaging applications: Characterization, photo-oxidation, and compost burial degradation. Polym Compos 2024;45:9802–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.28439. [CrossRef]

- Guessasma S, Belhabib S, Nouri H. Microstructure and mechanical performance of 3D printed wood-PLA/PHA using fused deposition modelling: Effect of printing temperature. Polymers (Basel) 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111778. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda-reinforced different biopolymer matrix green composites and MCDM-based sustainable material selection for automobile applications. Environ Dev Sustain 2025;27:10655–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04327-1. [CrossRef]

- Zindani D, Maity SR, Bhowmik S, Chakraborty S. A material selection approach using the TODIM (TOmada de Decisao Interativa Multicriterio) method and its analysis. n.d.

- Kulkarni ND, Saha A, Kumari P. Utilizing multicriteria decision-making approach for material selection in hybrid polymer nanocomposites for energy-harvesting applications. Polym Compos 2024;45:6264–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.28194. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A, Zindani D. Agro-waste-based polymeric composite laminates for aerospace cabin interior and identification of their optimal configuration. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024;14:31907–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04914-2. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S. Effects of graphene nanoparticles with organic wood particles: A synergistic effect on the structural, physical, thermal, and mechanical behavior of hybrid composites. Polym Adv Technol 2022;33:3201–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.5772. [CrossRef]

- Bagla A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P, Saha A. Development and Characterization of a Sustainable Bamboo-Polyvinylidene Fluoride Electro Spun Piezoelectric Nanogenerator Device for Smart Health Monitoring. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2025;7:5584–97. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.5c00408. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni ND, Saha A, Kumari P. The development of a low-cost, sustainable bamboo-based flexible bio composite for impact sensing and mechanical energy harvesting applications. J Appl Polym Sci 2023;140. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.54040. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Graphene nanoplatelets/organic wood dust hybrid composites: physical, mechanical and thermal characterization. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2021;30:935–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13726-021-00946-5. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Yang W, Liu M, Wang Z, Liu X. Wood Species Identification and Property Evaluation of Archaeological Wood Excavated from J1 at Shenduntou Site, Fanchang, Anhui, China. Forests 2025;16. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16071173. [CrossRef]

- Vlata M, Rapti S, Boyatzis S, Bardet M, Lucejko JJ, Pournou A. Melamine-formaldehyde in the conservation of waterlogged archaeological wood: investigating the effect of the treatment on wood residual chemistry with FTIR, 13C NMR, Py(HMDS)-GC/MS and EGA-MS. Wood Sci Technol 2025;59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-024-01610-w. [CrossRef]

- Traoré M, Martínez Cortizas A, López-Costas O, Paolino F, Łucejko JJ. Combining infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) and analytical pyrolysis for assessing chemical degradation pathways in waterlogged Neolithic wood. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2025;191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2025.107197. [CrossRef]

- Christophersen TPB, Gebremariam K, Risbøl O, Peacock EE. Identification of low-concentration tar in wood samples from archaeological contexts by ATR-FTIR. J Cult Herit 2025;75:93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2025.07.010. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumari P. Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites. Polym Compos 2023;44:2449–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.27256. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda fiber-micro particle reinforced hybrid green composite: A sustainable solution for tomorrow’s challenges in construction and building engineering. Constr Build Mater 2024;441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137486. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda fiber-micro particle reinforced hybrid green composite: A sustainable solution for tomorrow’s challenges in construction and building engineering. Constr Build Mater 2024;441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137486. [CrossRef]

- Kumar R, Kumar K, Bhowmik S. Mechanical characterization and quantification of tensile, fracture and viscoelastic characteristics of wood filler reinforced epoxy composite. Wood Sci Technol 2018;52:677–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-018-0995-0. [CrossRef]

- Sarker R, Bari MA Al, Saad S, Akash NM, Gupta C, Mahmud CK, et al. Investigation of mechanical and physicochemical properties of additively manufactured underutilized wood-PLA biocomposites. Polym Compos 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.29989. [CrossRef]

- Ecker JV, Haider A, Burzic I, Huber A, Eder G, Hild S. Mechanical properties and water absorption behaviour of PLA and PLA/wood composites prepared by 3D printing and injection moulding. Rapid Prototyp J 2019;25:672–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-06-2018-0149. [CrossRef]

- Das A, Gilmer EL, Biria S, Bortner MJ. Importance of Polymer Rheology on Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Correlating Process Physics to Print Properties. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2021;3:1218–49. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.0c01228. [CrossRef]

- Hassan M, Mohanty AK, Misra M. Additive Manufacturing of a Super Toughened Biodegradable Polymer Blend: Structure-Property-Processing Correlation and 3D Printed Prosthetic Part Development. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024;6:3849–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.3c03150. [CrossRef]

- Sanchaniya JV, Kannathasan KR, Vejanand SR, Joshi J, Lasenko I. Effect of Infill Pattern Design on Tensile Strength of Fused Deposition Modelled Specimens. Environment Technology Resources - Proceedings of the 16th International Scientific and Practical Conference, vol. 4, RTU PRESS; 2025, p. 375–82. https://doi.org/10.17770/etr2025vol4.8409. [CrossRef]

- Wegner I, Campbell M. Variable-Density Gyroid Infill for Increased Strength and Stiffness of 3D Printed Components, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA); 2024. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2024-81359. [CrossRef]

- Hassan MR, Jeon HW, Kim G, Park K. The effects of infill patterns and infill percentages on energy consumption in fused filament fabrication using CFR-PEEK. Rapid Prototyp J 2021;27:1886–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-11-2020-0288. [CrossRef]

- Dubey D, Singh SP, Behera BK. Mechanical, thermal, and microstructural analysis of 3D printed short carbon fiber-reinforced nylon composites across diverse infill patterns. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2025;10:1671–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-024-00731-9. [CrossRef]

- Dudescu C, Racz L. Effects of Raster Orientation, Infill Rate and Infill Pattern on the Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Materials. ACTA Universitatis Cibiniensis 2017;69:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/aucts-2017-0004. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese L, Marabello G, Chairi M, Di Bella G. Optimization of Deposition Temperature and Gyroid Infill to Improve Flexural Performance of PLA and PLA–Flax Fiber Composite Sandwich Structures. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2025;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp9020031. [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan Gladys A, Damodaran A, Ezhilan J J, Raghavan M, Venkatesan N. Effect of infill patterns on carbon nylon 3D-printed composites under ballistic impact. Phys Scr 2025;100. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/add29f. [CrossRef]

- Greco A, De Luca A, Gerbino S, Lamanna G, Sepe R. Influence of infill pattern and layer height on surface characteristics and fatigue behavior of FFF-printed PEEK. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2024;47:4741–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/ffe.14450. [CrossRef]

- Dubey D, Singh SP, Behera BK. Mechanical, thermal, and microstructural analysis of 3D printed short carbon fiber-reinforced nylon composites across diverse infill patterns. Progress in Additive Manufacturing 2025;10:1671–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-024-00731-9. [CrossRef]

- Ecker JV, Haider A, Burzic I, Huber A, Eder G, Hild S. Mechanical properties and water absorption behaviour of PLA and PLA/wood composites prepared by 3D printing and injection moulding. Rapid Prototyp J 2019;25:672–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-06-2018-0149. [CrossRef]

- Cañero-Nieto JM, Campo-Campo RJ, Díaz-Bolaño I, Ariza-Echeverri EA, Deluque-Toro CE, Solano-Martos JF. Infill pattern strategy impact on the cross-sectional area at gauge length of material extrusion 3D printed polylactic acid parts. J Intell Manuf 2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-025-02579-4. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh MH, Lai CJ, Liu KY, Chung CF, Wang SH, Pan CY, et al. Effects of printing temperature and filling percentage on the mechanical behavior of fused deposition molding technology components for 3d printing. Polymers (Basel) 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13172910. [CrossRef]

- Vanaei HR, Raissi K, Deligant M, Shirinbayan M, Fitoussi J, Khelladi S, et al. Toward the understanding of temperature effect on bonding strength, dimensions and geometry of 3D-printed parts. J Mater Sci 2020;55:14677–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-05057-9. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monzó J, Cárdenas J, García-Segovia P. Effect of Temperature on 3D Printing of Commercial Potato Puree. Food Biophys 2019;14:225–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11483-019-09576-0. [CrossRef]

- Ulkir O, Ertugrul I, Ersoy S, Yağımlı B. The Effects of Printing Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2024;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14083376. [CrossRef]

- Nazir A, Jeng JY. A high-speed additive manufacturing approach for achieving high printing speed and accuracy. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci 2020;234:2741–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954406219861664. [CrossRef]

- Žarko J, Vladić G, Pál M, Dedijer S. Influence of printing speed on production of embossing tools using fdM 3d printing technology. Journal of Graphic Engineering and Design 2017;8:19–27. https://doi.org/10.24867/JGED-2017-1-019. [CrossRef]

- Khosravani MR, Berto F, Ayatollahi MR, Reinicke T. Characterization of 3D-printed PLA parts with different raster orientations and printing speeds. Sci Rep 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05005-4. [CrossRef]

- Khosravani MR, Berto F, Ayatollahi MR, Reinicke T. Characterization of 3D-printed PLA parts with different raster orientations and printing speeds. Sci Rep 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05005-4. [CrossRef]

- Krapež Tomec D, Schwarzkopf M, Repič R, Žigon J, Gospodarič B, Kariž M. Effect of thermal modification of wood particles for wood-PLA composites on properties of filaments, 3D-printed parts and injection moulded parts. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2024;82:403–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-023-02018-2. [CrossRef]

- Veeman D, Palaniyappan S. Process optimisation on the compressive strength property for the 3D printing of PLA/almond shell composite. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2023;36:2435–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/08927057221092327. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Shafeer PP, Pitchaimani J, Doddamani M. A short banana fiber—PLA filament for 3D printing: Development and characterization. Polym Compos 2025;46:4863–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.28519. [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou A, Castro M, Bevan R, Martin N. 3D printing of wood fibre biocomposites: From mechanical to actuation functionality. Mater Des 2016;96:106–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.02.018. [CrossRef]

- Awad S, Siakeng R, Khalaf EM, Mahmoud MH, Fouad H, Jawaid M, et al. Evaluation of characterisation efficiency of natural fibre-reinforced polylactic acid biocomposites for 3D printing applications. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2023;36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00620. [CrossRef]

- Felix Sahayaraj A, Muthukrishnan M, Ramesh M. Experimental investigation on physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of jute and hemp fibers reinforced hybrid polylactic acid composites. Polym Compos 2022;43:2854–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.26581. [CrossRef]

| Microparticles | Stage-I weight loss (%) | Stage-II weight loss (%) | Stage-III weight loss (%) | Stage-IV weight loss (%) | Residual mass (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated wood | 5.19 | 1.81 | 63.77 | 34.88 | 21.96 |

| Treated wood | 1.55 | 1.14 | 21.26 | 66.50 | 25.67 |

| Wood particle (%) |

Tg (°C) |

TCC (°C) |

Tm (°C) |

Enthalpy (J/g) |

Crystallinity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 58.99 | 116.21 | 155.01 | 9.31 | 10.02 |

| 9 | 70.72 | 112.39 | 150.68 | 10.89 | 12.87 |

| Mechanical Properties | Equation | R2-value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength (MPa) (TS) | TS = -98.6 - 10.75 IP + 0.433 ID + 0.844 PT - 0.283 PS |

98.35 |

| Tensile modulus (GPa) (TM) | TM = -1.298 - 0.434 IP + 0.0214 ID + 0.028 PT - 0.016 PS | 99.39 |

| Elongation at break (%) (EBB) | EBB = 0.846 + 0.096 IP- 0.005 ID + 0.007 PT - 0.008 PS | 99.63 |

| Flexural strength (MPa) (FS) | FS= 42.1 - 4.21 IP + 0.347 ID + 0.135 PT - 0.556 PS | 88.25 |

| Flexural modulus (GPa) (FM) | FM = 1.96 - 0.112 IP + 0.021 ID+ 0.00189 PT - 0.012 PS |

96.01 |

| Compressive strength (MPa) (CS) | CS= -40.0 + 2.98 IP + 0.246 ID + 0.403 PT - 0.458 PS |

80.96 |

| Compressive modulus (MPa) (CM) | CM = -335 + 25.8 IP + 1.747 ID+ 3.20 PT - 3.25 PS |

82.37 |

| IFSS (MPa) | IFSS = -2.854 + 0.548 IP+ 0.018 ID + 0.043 PT - 0.040 PS |

99.47 |

| Impact strength (kJ/m2) (IS) | IS = -12.06 + 2.061 IP - 0.079 ID+ 0.222 PT- 0.202 PS |

99.04 |

| Natural Frequency (Hz) (NF) | NF= 18.03 - 3.693 IP + 0.356 ID + 0.081 PT - 0.028 PS |

99.80 |

| IP- Infill pattern, ID- Infill density, PT- Printing temperature, PS- Printing Speed | ||

| Criteria → | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition↓ | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Tensile Modulus (GPa) | Elongation at break (%) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Flexural Modulus (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Compressive Modulus (MPa) | IFSS (MPa) | Impact Strength (kJ/m^2) | Natural Frequency (Hz) |

| PRC-1 | 53.45 | 3.68 | 1.708 | 54.51 | 2.65 | 26.76 | 202.33 | 4.87 | 17.67 | 45.59 |

| PRC-2 | 71.71 | 4.36 | 1.576 | 60.40 | 3.19 | 33.25 | 259.33 | 5.21 | 16.23 | 55.41 |

| PRC-3 | 86.33 | 4.98 | 1.44 | 63.44 | 3.38 | 37.98 | 288.67 | 5.87 | 14.07 | 64.45 |

| PRC-4 | 42.01 | 3.14 | 1.684 | 47.95 | 2.43 | 32.58 | 255.67 | 5.01 | 17.83 | 41.37 |

| PRC-5 | 68.80 | 4.27 | 1.814 | 70.12 | 3.57 | 53.00 | 401.00 | 6.84 | 22.30 | 52.00 |

| PRC-6 | 57.97 | 4.04 | 1.468 | 68.10 | 3.49 | 43.34 | 321.33 | 6.02 | 14.29 | 59.08 |

| PRC-7 | 45.91 | 3.18 | 1.975 | 42.40 | 2.31 | 34.73 | 273.67 | 6.41 | 24.69 | 39.81 |

| PRC-8 | 39.00 | 3.06 | 1.602 | 45.28 | 2.84 | 31.44 | 247.67 | 5.62 | 15.81 | 46.76 |

| PRC-9 | 62.07 | 4.18 | 1.72 | 65.39 | 3.50 | 49.70 | 383.67 | 7.21 | 19.84 | 56.72 |

| Criteria → | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weightage→ | 0.195 | 0.082 | 0.029 | 0.094 | 0.076 | 0.148 | 0.137 | 0.054 | 0.109 | 0.077 |

| Sl. No. | Matrix | Reinforcement | Development Process |

Tensile Strength (MPa) |

Flexural Strength (MPa) |

Compressive Strength (MPa) |

Impact Strength | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | PLA | Wood | 3D printing | 68.80 | 70.12 | 53.00 | 22.30 kJ/m2 | Present study |

| 2. | PLA | Wood | 3D printing | 37.5 | -- | -- | -- | [81] |

| 3. | PLA | Wood | Injection moulding | 56.87 | -- | -- | -- | [81] |

| 4. | PLA | Almond shell | 3D printing | -- | -- | 28.748 | -- | [82] |

| 5. | PLA | Banana fiber | 3D printing | 16 | 29.2 | -- | -- | [83] |

| 6. | PLA | Wood | 3D printing | 65.80±1.39 | -- | -- | -- | [84] |

| 7. | PLA | Oil Palm | 3D Printing | 38.49 ± 2.63 | -- | -- | -- | [85] |

| 8. | PLA | Jute/hemp | Compression moulding | 69 | 145.40 | -- | 6.37 J | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).