1. Introduction

In recent years, research has put more focus on investigating the fabrication of Mycelium-Based Composites (MBC) for building interior applications, as they hold the potential to be more affordable compared to petroleum based-materials [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These composites are bio fabricated through the growth of fungal mycelium forming a dense network of hyphae that binds organic substrate materials into new composites. The performance of these materials is dependent on three key factors; the mycelium species, substrate material, and fabrication growth parameters [

1]. MBC properties can be engineered by altering the growth parameters to improve the performance and application range [

6,

7]. Architects have shown strong interest in MBC for insulation, particularly as acoustic absorbers in building and interior applications [

8,

9]. Acoustic absorbers are typically fibrous and porous materials, including foams and various organic and inorganic fibers. MBC are excellent sound absorbers, offering strong low-frequency absorption similar to cork and commercial ceiling tiles yet showing low mechanical strength which is especially critical for suspended absorbers [

10,

11].

Research has demonstrated that growth parameters significantly impact the mechanical and acoustic properties of MBC, which can be managed through environmental, temporal, and physical factors [

1]. Environmental conditions like temperature, CO₂ levels, and pH affect growth patterns and vary with each fungal strain [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Time influences material density and porosity [

16,

17]. Physical parameters—including moisture, nutrients, pressure, cutting, and drying—can be used to enhance or alter growth [

1,

18,

19]. To broaden the application field of MBC, digital biofabrication is researched to enhance the growth and shape of mycelium materials [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. The hypothesis suggests that growth parameters can be controlled to localize specific material properties, enabling a shift from single-property optimization to the creation of graded materials. For instance, porosity is essential for sound absorption, but longer growth periods may reduce this quality by increasing mycelium density [

8]. While increased density can initially boost mechanical strength in MBC, this strength often decreases over time due to substrate degradation. This challenge has sparked interest in digital biofabrication techniques for optimizing MBC during incubation, enabling precise control over growth conditions to balance both mechanical strength and acoustic performance. By carefully tuning growth parameters, this approach allows for the integration of multiple locally optimized properties within a single material. Consequently, graded materials can deliver complex, multifunctional performance, making them especially valuable in fields like construction, where a single component often requires diverse properties such as strength and sound absorption. We introduce the use of non-woven mats as a promising substrate material, offering several advantages, including greater design flexibility, initial mechanical properties, and cost reduction, as they eliminate the need for full surface molds during production. We hypothesize that liquid spawn can be more accurately applied to non-woven mats, promoting uniform mycelial growth and enabling better control over the growth mechanisms of the mycelium across the substrate. Besides being easier to integrate in a digital biofabrication system, studies have shown that liquid spawn enhances mechanical strength [

1].

This paper explores the deposition of liquid spawn on non-woven hemp mats. Our choice of hemp is because of its growing availability in Flanders, making it a local resource [

27]. The goals is to understand the first steps in the production process and the growth kinetics of both grain and liquid spawn on non-woven mats. Through the understanding of the adaptability of mycelium growth, researcher can harness this feature to design and fabricate with. This is the first study undertaking an analysis of liquid inoculation on non-woven hemp mats by characterizing its growth rate.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach focusses on monitoring the growth of local liquid inoculation of G. lucidum and P. ostreatus on non-woven hemp mats. The effect of two liquid nutrient media in a static and shaking incubation on mycelium growth as a preculture and respective dilutions have been mapped and compared by analyzing the surface colonization rate against grain spawn inoculation. During this approach the ease of inoculation between both inoculation method has been compared and visually analysis has been used to understand potential material properties using specific mycelium species.

This experiment was part of a two-stage protocol designed to cultivate mycelium in liquid media, followed by using these precultures to grow mycelium on non-woven hemp mats. The procedure consists of two primary stages, carried out in succession:

- (1)

Development mycelium-based liquid spawn.

- (2)

Monitoring growth on non-woven mats.

2.1. Fungal Species and Materials

G. lucidum (M9726) and P. ostreatus (M2191) are both white-rot species and their grain spawn was purchased from Mycelia bvba (Veldeken 38A,9850 Nevele, Belgium). The species were conserved on a grain mixture at 4 °C in a breathing Microsac 5 L bag (Sac O2 nv, Nevele, Belgium). The studies were performed on 100% natural, non-woven hemp mats “HempFlax Felt” obtained from HempFlax (Groningen, Netherlands)

2.2. Preparation of Liquid Spawn

Grain spawn of both fungal strains were inoculated on a yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) 2% glucose agar plate. Subsequently, these plates were incubated at 27 °C for 7 days. Once the mycelium was fully matured on the agar plates, liquid spawn was prepared in either a liquid YPD (2% glucose) or liquid complete yeast medium (CYM).

The agar plates are prepared by mixing 10 g of granulated yeast extract, 20 g of bacteriological peptone, 50 ml of 40% glucose, and 20 g of agar into 950 ml of demineralized water. The liquid YPD medium is made using the same ingredients but without the addition of agar. The liquid CYM medium consists of 2 g of granulated yeast extract, 2 g of bacteriological peptone, 0.5 g of MgSO₄, 1 g of K₂HPO₄, 0.46 g of KH₂PO₄, and 50 ml of 40% glucose, also added to 950 ml of demineralized water. All solutions are sterilized in an autoclave for 15 minutes at 121 °C, with the glucose added afterward to each solution. The YPD agar is poured into petri dishes and allowed to solidify. All three media are then stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for the duration of the experiment.

To create the liquid spawn, seen in

Figure 1, a mycelium section of 1.5 cm

2 was transferred from the agar plate to a falcon tube containing glass beads and 20 mL of liquid media. To ensure thorough homogenization of the mycelium the falcon tube was vortexed. From the homogenized mycelium, 2 mL was transferred to a new falcon tube containing 18 mL of the according medium and placed at 27 °C in a static or shaking incubator for a period of 5 days.

2.3. Inoculation of Both Mycelium Species on Non-woven Hemp Mats.

The hemp non-woven mats were cut into 5 cm2 squares. After cutting the non-woven mats, the dry weight was measured, enabling the calculation of moisture content introduced during the sterilization (121°C for 15 minutes). After 5 days of growing liquid spawn statically (ST) and shaking (SH), 4 different precultures were made: ST YPD, SH YPD, ST CYM, and SH CYM for both mycelium strains. It was necessary to vortex the SH condition before making the 4 dilutions. After preparing the preculture a 1:10, 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 dilutions from each one, three biological repeats were made for each dilution, and each non-woven mat was inoculated with 3 mL applied to the center, with three technical repeats conducted per mat. After inoculation, all samples were stored in an incubator at 27°C for 14 days. After 14 days of incubation, the mats were dried at 60°C for 15 hours to terminate the mycelium growth, allowing for their preservation for future research.

2.4. Surface Colonisation Rate Measurement and Analysis

To monitor mycelium growth during incubation, the samples were photographed every 24 hours for 14 days. A photobox setup was arranged beneath the laminar flow hood, shown in

Figure 2, to minimize the risk of contamination during photography. The images were captured with a Canon EOS R10 and a CA-Dreamer Macro 2x lens, positioned 46 cm above the samples. The aperture was set to f/8 with a focus distance of 0.37 to 1 m. A red mark on the petri dish and tape in the photobox ensured proper alignment of the samples.

Analysis of the mycelium extension rate was conducted by measuring the surface area covered by the mycelium. Images were imported into ImageJ, where the scale was set using the petri dish diameter. The average diameter was calculated by averaging both the horizontal and vertical measurements. From this average diameter, the area was calculated and then expressed as a percentage of the total area of the mat on which it was growing. This percentage was then plotted against time (days) to generate the growth curve.

3. Results

To obtain more insights into whether the growth of mycelium strains was dependent on preculture medium, shaking or static conditions, and the dilution of inoculants on non-woven mats, we aimed to identify differences in growth efficiency. This analysis was conducted because understanding the growth of liquid spawn on non-woven mats would pave the way for printing with and controlling its growth through robotic manipulations during incubation. This production method will allow us to produce graded biomaterials. This was the first step in understanding how this production method could be achieved using mycelium liquid spawn.

3.1. Mycelium Growth in Liquid Media

It was observed, shown in

Figure 3, that the ST grew in a cloudy shape, whereas the mycelium in the SH condition grew in a spherical form.

3.2. Mycelium Growth and Surface Colonization

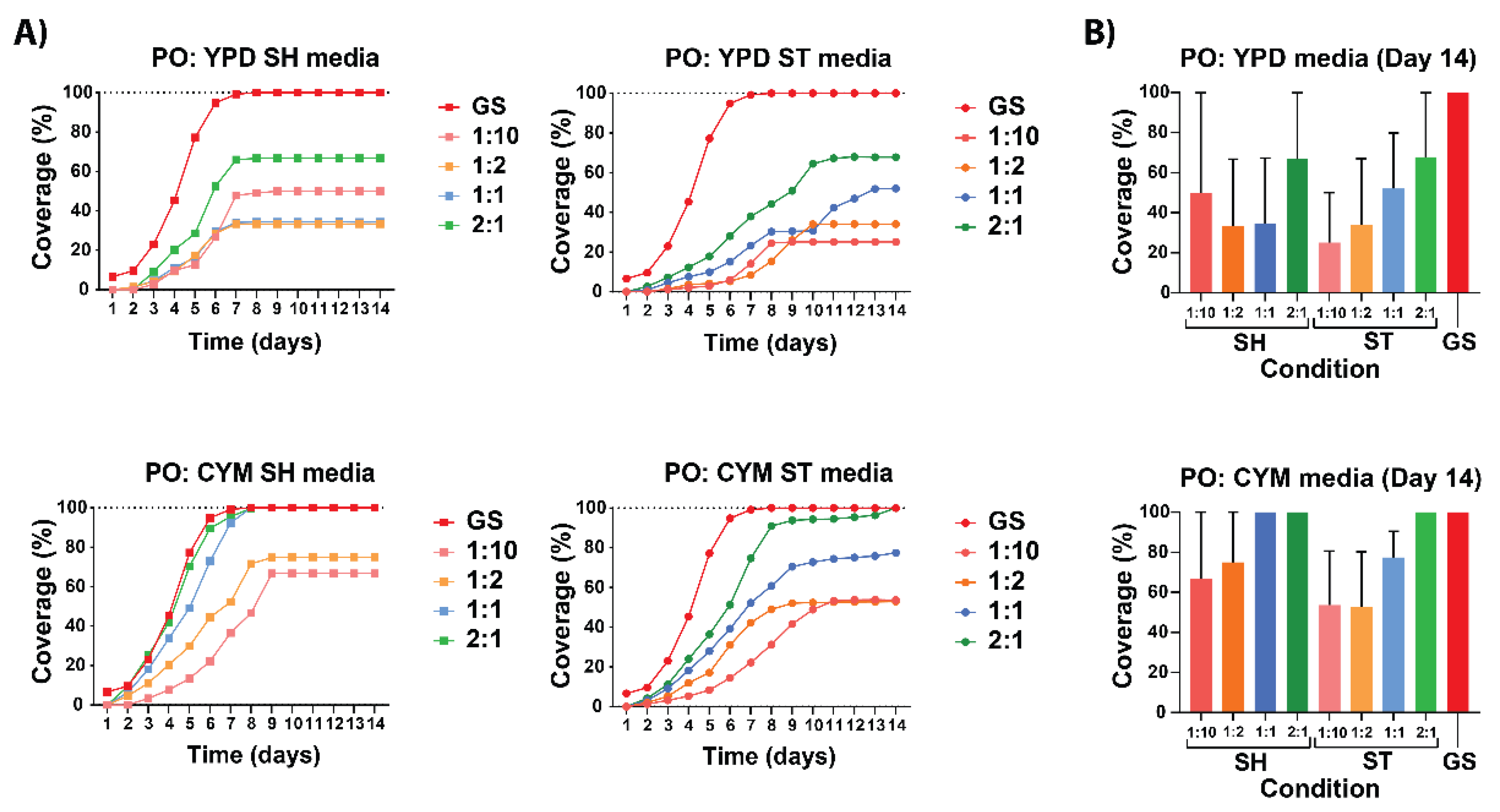

The results show that the dilution and liquid media composition influence the growth of hyphae. To assess the influence of the dilution and liquid media composition, different growing conditions and dilutions were made, compared to each other and grain spawn used for comparison. The first observation is that the growth curves of grain spawn of both species did not start at zero due to the initial detectable biomass. The liquid spawn growth curves began at zero due to the absence of observable growth on the day of inoculation. The main results from the growth curves of both species (

Figure 4 & 6), as expected, is that the lower the dilution the faster and more likely the hyphae will achieve 100% coverage. The grain spawn samples had the fastest growth rate and were the most reliable to achieve 100% coverage, likely because of the initial amount of biomass compared to the liquid media. They achieved full coverage on day 7 for P. ostreatus and G. lucidum whereas the liquid media achieved the stationary phase between day 7 and day 11. The coverage on day 14 suggested that G. lucidum is more reliable than P. ostreatus to achieve 100% coverage over all conditions. The growth curves of both species indicated that CYM improved the growth of hyphae across all dilutions compared to YPD and a closer examination revealed that the shaking conditions achieved a closer fit to the grain spawn growth curve over their static counterpart.

3.2.1. Growth Kinetics of P. ostreatus on Non-woven Hemp Mats

When comparing liquid media with grain spawn for

P. ostreatus (

Figure 4), The preculture in CYM medium was found to enhance growth more effectively than a preculture in YPD and mycelium from shaking conditions came closer to the growth curve of the grain spawn then the static conditions. The SH media of P. ostreatus showed similar growth rates achieving the stationary phase between day 7 and day 9. Whereas the ST media achieved it between day 8 and day 11. Interestingly, when examining the differences in culture media, the cultivation of

P. ostreatus in YPD media did not support full coverage of the hemp mats, while CYM media achieved full coverage. The comparison between static and shaking conditions showed that for the YPD and CYM media, the shaking condition had a higher growth rate on the non-woven mats. Notably, the YPD SH media displayed (

Figure 4A) an unexpected order among the dilutions, possibly due to the unoptimized sterilization protocol, which led to inconsistent differences in coverage percentages and artificially lowered the overall mean.

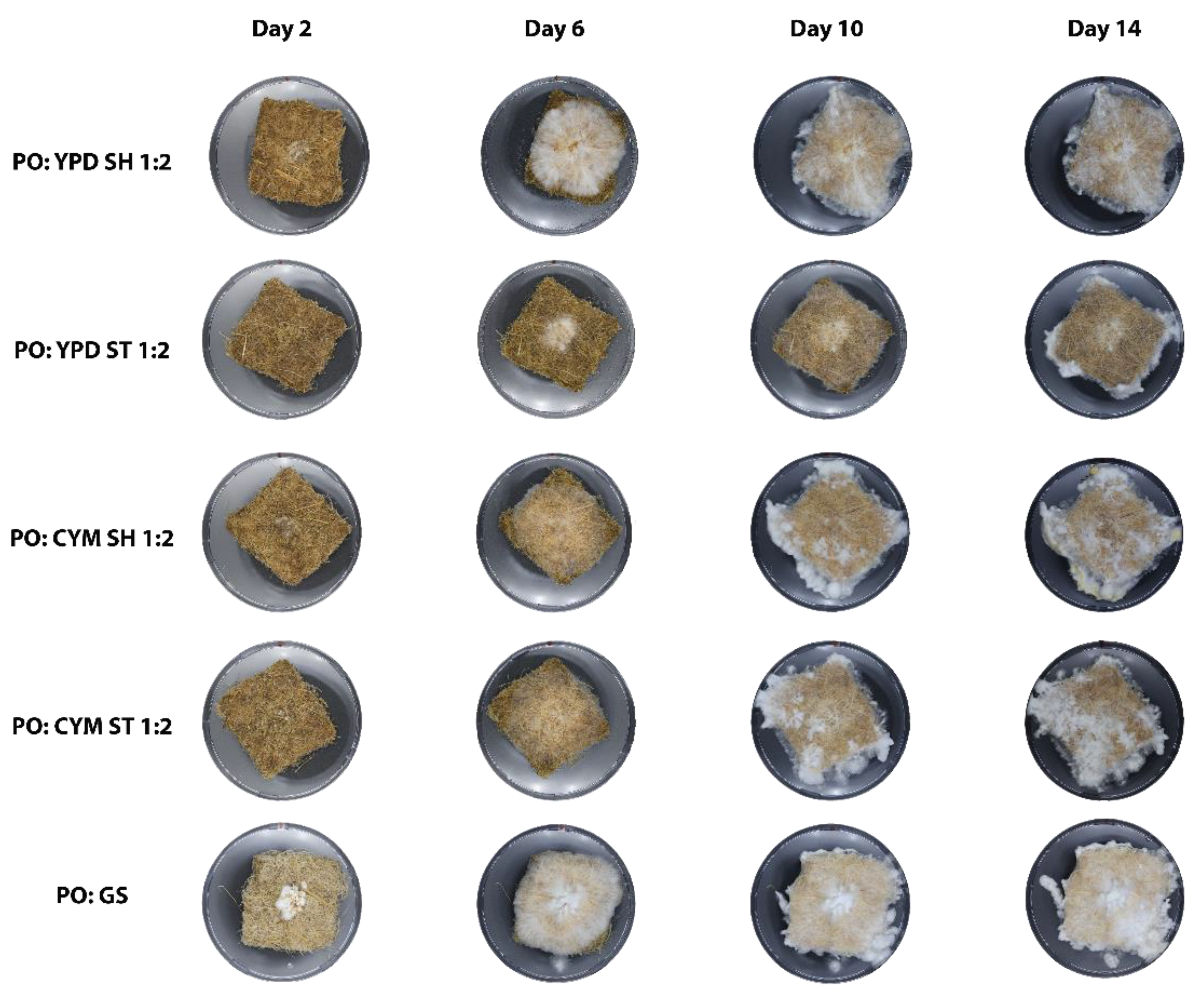

From a visual analysis (

Figure 5), P. ostreatus developed thin hyphae that spread across the mat until they reached the edges. By day 10, it began to produce aerial mycelium, as seen in

Figure 4 C, which appeared as a white, fluffy substance extending beyond the perimeter of the mats. Notably, P. ostreatus did not grow densely, allowing the non-woven structure of the mat to remain visible through the hyphae.

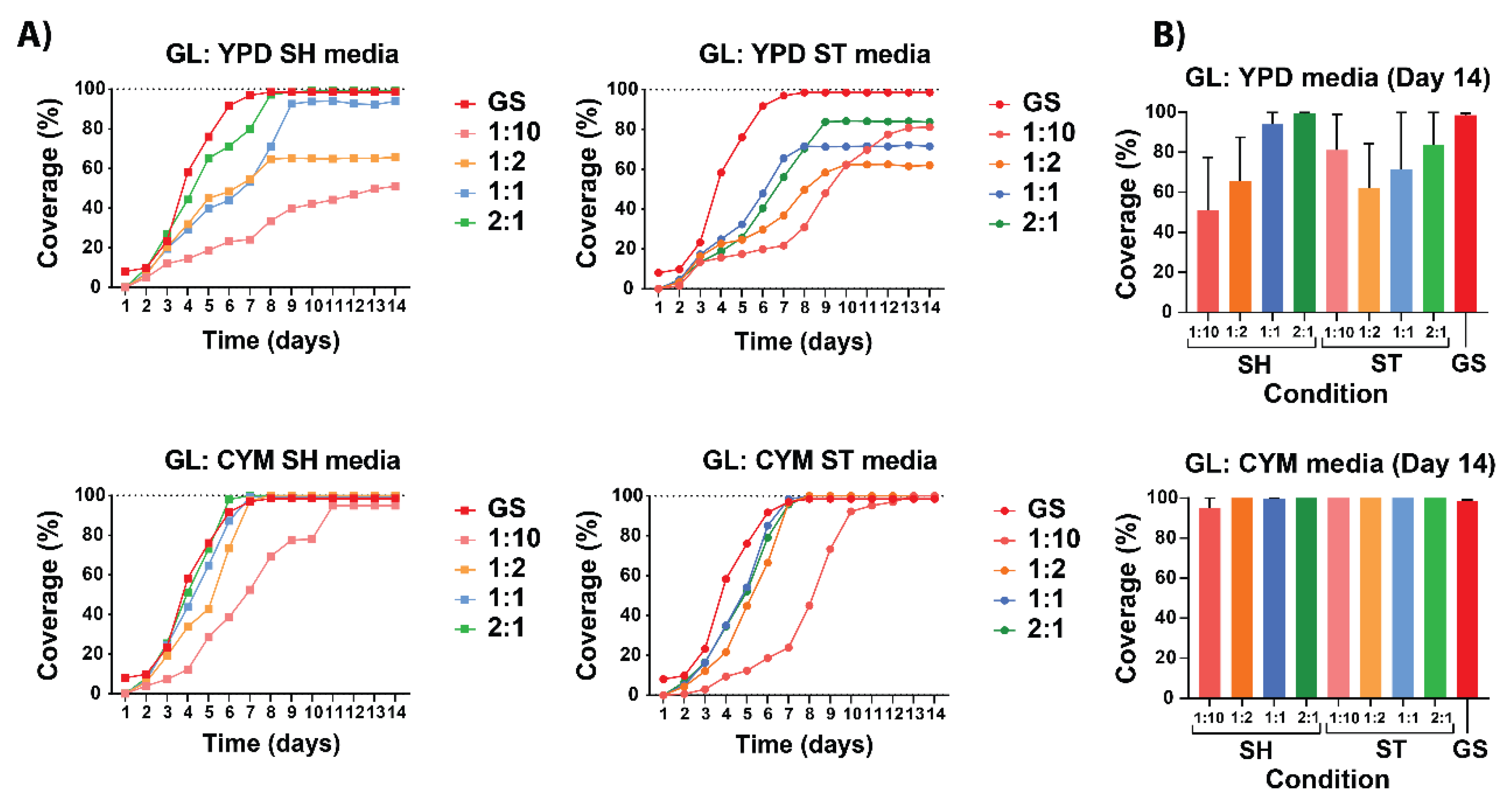

3.2.2. Growth Kinetics of G. lucidum on Non-woven Hemp Mats

When comparing liquid media with grain spawn for

G. lucidum (

Figure 6), CYM media clearly outperforms YPD. CYM achieved 100% coverage for both conditions and all dilutions and clearly fits in the growth curve of grain spawn. All conditions were able to achieve 100% coverage except for the YPD ST condition. In CYM media, the

G. lucidum species exhibited more consistent results in terms of growth rate and coverage compared to the grain spawn. Comparing the shaking and static conditions for both media it showed that shaking conditions achieves their maximum coverage between day 5 and day 8 whereas it is between day 7 and day 9 for ST.

Comparing all four conditions and dilutions, the same relationship as of P. ostreatus was observed during the exponential phase of the growth curve. Notably, the YPD ST media displayed an unexpected order among the dilutions similar to P. ostreatus YPD SH. YPD growth curves display distinct separation, with each curve reaching specific growth percentage levels at different rates. The CYM dilutions of 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1 showed similar growth curves, while dilution 1:10 had a noticeably lower growth curve.

G. lucidum primarily grew within the mat area and did not produce aerial mycelium (

Figure 7). It exhibited a denser growth pattern, with the mat’s structure covered by hyphae. Additionally, G. lucidum underwent color changes. For both YPD ST and SH conditions, G. lucidum started to change color between days 6 and 13, whereas in CYM ST and CYM SH, the color changes began between days 8 and 11. Similar to the liquid culture, the G. lucidum grain spawn began to change color between days 8 and 10.

4. Discussion

The understanding of the growing property as a design parameter will open digital biofabrication possibilities to produce graded materials. The results of this experiment are a first indication that the preculture media influences biomass growth and that the biomass in a liquid spawn can be used as a parameter to control mycelium growth through dilution. Using grain spawn on non-woven mats has certain limitations, including difficulty in achieving homogeneous mixing within the substrate and reduced precision during deposition. This is reflected in the initial coverage percentage, which indicates the average diameter of the grain spawn at the time of placement. In contrast, liquid spawn offers the potential for more precise deposition and mixing within the mats.

4.1. Non-Woven Hemp Mats Are Susceptible to Contamination

Notably, none of the repeats for either species, grown with grain spawn, experienced contamination, suggesting that grain spawn is more robust compared to liquid spawn. This robustness may be attributed to the initially higher mycelium biomass concentration in grain spawn and that slower growth of mycelium makes the substrate more prone to contamination [

28]. Though similar concentrations could potentially be achieved with liquid spawn if allowed to grow for a longer period, in a shaking condition or when an optimized nutrient medium is made [

29].

During our experiments, growth variations were observed in the technical repeats due to contamination during the incubation of the liquid spawn on the mats, arising from unoptimized sterilization processes. The sterilization method was modified to sterilize for longer times which resulted in less contamination aligning with previous research [

1]. Still, some repeats showed contamination, resulting in decreased or halting the growth and therefore were not used in the results. Contamination still occurred and should be further optimized to eliminate any interference with mycelium growth. The observed contamination appeared consistent with the characteristics of the

Aspergillus genus, a group of molds commonly found in diverse environments worldwide.

Aspergillus typically exhibits yellow, green, or black coloration, seen in

Figure 1A, with a fluffy texture due to spore production, supporting the assumption that this was the contaminant [

30]. Further investigating the sterilization protocol is of utmost importance to fully grasp the growth mechanisms without interference.

4.2. Precultures Have an Influence on Mycelium Growth

The results from both ST and SH conditions, along with their respective dilutions, provide valuable insights as a foundation for the digital biofabrication system. The shaking condition aligns with previous research, where mycelium tends to grow in spherical shapes due to the centrifugal forces exerted within the liquid media increasing mycelium biomass [

29,

31]. This impacts both the system’s energy use and the controllability of mycelium growth. Shaking conditions enhance biomass production through continuous oxygen exchange with the liquid, as demonstrated in our findings with P. ostreatus and G. lucidum, where shaking led to improved growth rates on the mats [

31]. However, shaking cultures must be vortexed before inoculation to prevent clogging caused by spherical growth forms, which can interfere with printing. This extra step increases energy consumption during fabrication, making static growth preferable, as it also supports effective mycelium development without the additional energy input.

The growth curves showed that CYM medium improved growth on hemp mats over YPD. Mycelium growth is dependent on the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N) within the medium. The results indicated that a lower C/N ratio, due to a higher amount of nitrogenous material, led to increased biomass production. [

29]. Since CYM has less nitrogenous material, it may have encouraged the mycelium to develop more adaptive, efficient growth forms. When inoculated onto the hemp mats, this adaptation could help the mycelium use the substrate’s nutrients more effectively, resulting in more effective colonization. To control the mycelium during fabrication it is preferred to have slow growth to have time for manipulation. Static conditions may offer more promise for practical use, as shaking precultures require additional energy to produce and the accelerated growth on the hemp mat reduces control over the mycelium, which could be a disadvantage in applications requiring precise growth manipulation. YPD media is therefore preferred over CYM and a higher dilution is recommended, as it has the least biomass, resulting in the slowest growth rate while still achieving comparable coverage percentages.

An important parameter for optimizing the digital biofabrication process is the nutrient composition in the liquid spawn, as it directly influences the growth rate and surface coverage of the mycelium. By adjusting nutrient dilution, the digital biofabrication system can precisely control whether the application requires rapid or slow growth, as well as full or partial surface coverage.

Key findings indicate that higher dilutions allow for slower growth and partial coverage, enabling finer control when precise growth patterns are needed. Lower dilutions, on the other hand, support rapid growth and complete surface coverage. Interestingly, the study shows that higher dilutions can sometimes achieve similar coverage percentages to lower ones, making it possible to generate more preculture from a single batch. This discovery has significant implications for material efficiency and cost reduction in production, enhancing the flexibility and sustainability of the digital biofabrication system.

By integrating nutrient composition adjustments as a variable, the digital biofabrication process becomes a more versatile and cost-effective tool for creating customized, graded mycelium-based composites.

4.3. Potential Material Properties to Control with P. ostreatus and G. Lucidum

From visual observations, potential material properties can be deduced.

P. ostreatus produces more aerial mycelium and exhibits a lower growth density on the non-woven mats, suggesting its suitability for bonding multiple layers together without compromising sound-absorbing qualities. This corresponds to previous research comparing

P. ostreatus and

G. lucidum on acoustic properties which concluded that

P. ostreatus is preferred for acoustic applications [

32]. On the other hand,

G. lucidum shows higher growth density and stronger attachment to the substrate, indicating its potential to enhance material strength over

P. ostreatus which also corresponds with previous research [

33]. This opens up the possibility of combining both species within the same material, allowing for an exploration of multi species fabrication and the development of graded materials.

G. lucidum offers greater aesthetic potential than

P. ostreatus due to its color-changing capability, which research has linked to environmental factors [

33]. Changes in temperature, humidity, nutrient levels, airflow, and light exposure can shift the mycelium’s color to yellowish, brownish, or even reddish tones [

34]. Gaining control over the color-shifting properties of

G. lucidum presents a unique opportunity to develop graded mycelium-based composites with both functional and aesthetic variations. By embedding this color variability directly into the fabrication process, architects and material scientists could create mycelium composites that vary not only in functional properties but also appearance. In essence, these graded mycelium-based materials offer customizable functional and aesthetic properties, expanding the potential applications in sustainable architecture and design.

5. Conclusions

This study proves feasibility and showcases potential for using liquid spawn for digital biofabrication. It provides an initial framework for applying liquid mycelium spawn on non-woven hemp mats, with findings that underscore the potential to produce graded Mycelium-Based Composites (MBC) for building interior applications. By examining both grain and liquid spawn, we demonstrated that liquid spawn offers greater precision in deposition and control over mycelium growth on non-woven substrates, making it well-suited for digital biofabrication systems. Our results reveal that liquid spawn can achieve faster and more uniform growth, enhancing mechanical strength while offering control over material properties essential for applications such as acoustic absorbers. Precultures grown under shaking conditions enhanced growth on non-woven mats but could increase overall energy use and fabrication costs. Lower mycelium dilutions in liquid spawn showed faster growth rates and higher coverage, with CYM media more effectively promoting mycelium growth than YPD. Additionally, a higher dilution allowed better control over growth due to its slower rate on hemp mats, a factor beneficial for digital biofabrication as it enables fine-tuning of material properties. The adaptability of mycelium growth was observed, particularly with lower spawn dilutions and CYM media, which promoted rapid growth and improved coverage on the hemp mats. This substrate material enables mycelium growth due to its local availability and flexibility in design applications local mycelium production is possible.

Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of controlling growth parameters—including environmental, temporal, and physical factors—within digital biofabrication systems to fine-tune the performance characteristics of MBC. Liquid spawn’s compatibility with non-woven mats supports targeted growth manipulation, enabling a promising route for creating graded materials that balance acoustic performance and mechanical strength. The distinct material properties of different fungal species, such as Pleurotus ostreatus’ potential for sound absorption and Ganoderma lucidum’s strength-enhancing qualities, suggest the feasibility of designing graded materials. G. lucidum’s unique aesthetic characteristics, such as its ability to change color, further highlight opportunities to integrate biological growth dynamics into architectural and material design, enabling both functional and aesthetic customization. Future research will focus on developing optimized protocols for liquid spawn application in 3D printing, exploring multi-species composites to enhance specific material qualities, and advancing digital biofabrication systems for precise, localized growth control. Together, these efforts aim to broaden MBC applications in interior architecture, enhancing the material’s functionality, sustainability, and design potential.

Supplementary Materials

TThe following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

A.B. conceived the study and carried out the test; A.B. and M.S. designed the experiments and analyzed the tests; A.B., M.S., and P.V.D interpreted results; A.B., M.S, P.V.D, and J.W. edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology of Prof. Patrick Van Dijck for their support and sharing their equipment and knowledge to conduct this experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

A: Three occurring contamination during the experiment. No analysis has been conducted on which microorganisms these are.

Figure A1.

A: Three occurring contamination during the experiment. No analysis has been conducted on which microorganisms these are.

References

- Elsacker, E. V. Mycelium matters-an interdisciplinary exploration of the fabrication and properties of mycelium-based materials. 2021.

- Bitting, S.; Derme, T.; Lee, J.; Van Mele, T.; Dillenburger, B.; Block, P. Challenges and Opportunities in Scaling up Architectural Applications of Mycelium-Based Materials with Digital Fabrication. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qahtani, S.; Koç, M.; Isaifan, R. J. Mycelium-based thermal insulation for domestic cooling footprint reduction: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Javadian, A.; Acosta, I.; Özdemir, E.; Nolte, N.; Saeidi, N.; Dwan, A.; Ren, S.; Vries, L.; Hebel, D. Wurm, J. and Eversmann, P. HOME: wood-mycelium composites for CO2-neutral, circular interior construction and fittings. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2022; IOP Publishing: Vol. 1078, p 012068. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Tajvidi, M.; Howell, C.; Hunt, C. G. Insight into mycelium-lignocellulosic bio-composites: Essential factors and properties. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2022, 161, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamood, R. M.; Akinlabi, E. T.; Shukla, M.; Pityana, S. L. Functionally graded material: an overview. 2012.

- Ren, L.; Wang, Z.; Ren, L.; Han, Z.; Liu, Q.; Song, Z. Graded biological materials and additive manufacturing technologies for producing bioinspired graded materials: An overview. Composites Part B: Engineering 2022, 242, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, T. S.; Rychtarikova, M.; Armstrong, R.; Piana, E.; Glorieux, C. Acoustic applications of bio-mycelium composites, current trends and opportunities: a systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Sound and Vibration; 2023; Society of Acoustics. [Google Scholar]

- Dwan, A. , Edvard Nielsen, J. and Wurm, J. Room acoustics of Mycelium Textiles: the Myx Sail at the Danish Design Museum. Research Directions: Biotechnology Design, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, M. G.; Holt, G. A.; Wanjura, J. D.; Greetham, L.; McIntyre, G.; Bayer, E.; Kaplan-Bie, J. Acoustic evaluation of mycological biopolymer, an all-natural closed cell foam alternative. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 139, 111533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biront, A.; Wurm, J. Reinforcement Techniques for Mycelium-Based Composites: A Review. Responsive Cities: Collective Intelligence Design - Symposium Proceedings 2023, Institut d’Arquitectura Avançada de Catalunya; Barcelona, 2023, pp. 266–79.

- Hoa, H. T.; Wang, C.-L. The effects of temperature and nutritional conditions on mycelium growth of two oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology 2015, 43, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, P. Method for producing fungus structures. Google Patents: 2016.

- Appels, F. V.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Lukasiewicz, C. E.; Jansen, K. M.; Wösten, H. A.; Krijgsheld, P. Hydrophobin gene deletion and environmental growth conditions impact mechanical properties of mycelium by affecting the density of the material. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwulski, M.; Sobieralski, K.; Górski, R.; Lisiecka, J.; Sas-Golak, I. Temperature and ph impact on the mycelium growth of Mycogone perniciosa and Verticillium fungicola isolates derived from polish and foreign mushroom growing houses. Journal of plant protection research 2011, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H. Cellulose-mycelia foam: Novel bio-composite material. University of British Columbia, 2016.

- Appels, F. V.; Camere, S.; Montalti, M.; Karana, E.; Jansen, K. M.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Krijgsheld, P.; Wösten, H. A. Fabrication factors influencing mechanical, moisture-and water-related properties of mycelium-based composites. Materials & Design 2019, 161, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, J.; Ali, M. A.; Ahmad, W.; Ayyub, C. M.; Shafi, J. Effect of different substrate supplements on oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) production. Food Science and Technology 2013, 1, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, A. The effect of different nitrogen sources on mycelial growth of oyster mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 2018.

- Chan, F. Robotic and Sand Dropping. Master’s Thesis, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dörfler, K.; Hack, N.; Sandy, T.; Giftthaler, M.; Lussi, M.; Walzer, A. N.; Buchli, J.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Mobile robotic fabrication beyond factory conditions: Case study Mesh Mould wall of the DFAB HOUSE. Construction robotics 2019, 3, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantenbein, S.; Colucci, E.; Käch, J.; Trachsel, E.; Coulter, F. B.; Rühs, P. A.; Masania, K.; Studart, A. R. Three-dimensional printing of mycelium hydrogels into living complex materials. Nature Materials 2023, 22, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J. J.; Ammu, S.; Vriend, V. D.; Kieffer, R.; Kleiner, F. H.; Balasubramanian, S.; Karana, E.; Masania, K.; Aubin-Tam, M. E. Growth, distribution, and photosynthesis of chlamydomonas reinhardtii in 3D hydrogels. Advanced Materials 2024, 36, 2305505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Large-scale robotic extrusion-based additive manufacturing with living mycelium materials. Sustainable Futures 2022, 4, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, A.; Vieira, F. R.; Pecchia, J. A.; Gürsoy, B. Three-dimensional printing of living mycelium-based composites: Material compositions, workflows, and ways to mitigate contamination. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goidea, A.; Floudas, D.; Andréen, D. Pulp Faction: 3d printed material assemblies through microbial biotransformation. In Fabricate 2020, 2020; UCL Press: pp 42-49.

- Ministerie van Landbouw, N. e. V. België: opkomst van alternatieve landbouwgewassen. agroberichtenbuitenland, 2020. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit. (accessed 14/10/2024).

- Elsacker, E.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Functional grading of mycelium materials with inorganic particles: The effect of nanoclay on the biological, chemical and mechanical properties. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursid, M. N.; Manulang, M.; Samiadji, J.; Marraskuranto, E. Effect of Agitation Speed and Cultivation Time on the Production of the Emestrin Produced by Emericella Nidulans Marine Fungal. Squalen Bulletin of Marine and Fisheries Postharvest and Biotechnology 2015, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, K. The Genus Aspergillus. In The Williams and Wilkins Co; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bermek, H.; Gülseren, İ.; Li, K.; Jung, H.; Tamerler, C. The effect of fungal morphology on ligninolytic enzyme production by a recently isolated wood-degrading fungus Trichophyton rubrum LSK-27. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2004, 20, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezer, E. D.; Kuştaş, S. Acoustic and Thermal Properties of Mycelium-based Insulation Materials Produced from Desilicated Wheat Straw-Part B. BioResources 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, F. A.; Reyes, J. C. Compressive strength and water absorption percentage of Pleurotus Ostreatus and Ganoderma Lucidum mycelium. LACCEI 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, J.; Carmen Limón, M. Biological Roles of Fungal Carotenoids. Current Genics 2014, 61, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).