1. Introduction

Generative AI has become increasingly prevalent and ubiquitous across disciplines and applications, from the use of GPT for generating written text to Latent Diffusion Models (LDM) for creating realistic imagery and videos. These techniques are increasingly being applied in architectural research, influencing automated ideation in design practice and reshaping design workflows and design education. Despite the increasing realism of synthetic imagery, several research gaps have emerged, including model alignment with human perceptions, the plausibility of the synthetic image, the explainability of the model, and the controllability of image editing. Our study focuses on exploring the alignment with human perceptions to support architectural design processes and create façades that resonate with human perceptions. We ask: (1) Can accessible and open source pretrained generative vision models such as Stable Diffusion (SDXL) produce geographically aligned architectural counterfactuals of façades in urban settings? (2) Do AI-generated façades align with human perceptual descriptions ranging from objective to affective descriptors?

2. Related Works

Generative Urban Design GUD is a well-studied area in architectural computation [

1,

2,

3] and can be broadly categorise into rule-based methods, optimisation-based methods and AI-based methods [

4,

5,

6,

7]. For example, procedural models such as CityEngine [

8,

9] employ a set of predefined rules/grammers to automate city and building generation. These models are scalable, interpretable, and can easily integrate with explicit urban design rules and guidelines in practice. More recently, we have seen the use of vision-based generative models for architectural and urban design ideation, which is the primary focus of this study [

7,

10].

2.1. Vision-Based Generative Design

Early efforts include the use of Generative Adversarial Networks GAN [

11] that uses a generator to synthesize images and a discriminator that improves the image quality [

12,

13]. Examples in architecture and urban design include its use to synthesize street network patches [

14], architectural floor plans [

15,

16], building footprint[

17] and street scenes [

18]. For example, [

18] edits the latent space of a VAEGAN in synthesising plausible streetviews that adheres to different image classifier. While GAN-based image synthesis methods demonstrate early promises, they are often unstable to train, lack image diversity and offer limited control over the output.

Recent research have shifted toward Denoising Diffusion Models such as Latent Diffusion [

19,

20], for text-to-image generation, which offer improved fidelity, diversity, and controllability in generative outputs. Several studies have integrated these models into their architectural and urban design research. [

21,

22,

23,

24]. This includes its use in controllable floorplan generation [

25,

26], urban footprint generation [

21], architectural facade generation [

27], image inpainting of historic architectural details [

28], generating urban design renders [

24], 3D urban blocks [

23] and holistic urban environments [

22]. Despite their potential, limited research studied the perceptual alignment of these models in architectural facade design.

2.2. Leveraging Urban Imagery for Human Perception Studies

Interests in evaluating perceptual quality of urban imagery have increased significantly, driven by the growing availability of street-level imagery (e.g., Google Street View, Mapillary) and advances in computer vision [

29,

30]. A seminal example is StreetScore [

31,

32], which collected crowd-sourced image ratings and developed machine learning models to predict the perceptual quality of streetscapes [

33]. However, despite this progress, limited research evaluated the alignment of generative street views with human perceptions. One exception is [

27] which compared real and synthetic facade imagery from Antonio Gaudi according to its authenticity, attractiveness, creativity, harmony, and overall preferences. Such research has primarily emphasized on aesthetic quality rather than providing a more comprehensive understanding of perceptual alignment.

2.3. Perceptual and Affective Quality of Our Environment

The perceptual and affective quality of our environment, whether built or natural settings, is well-studied in cognitive science and environmental psychology, highlighting the influence of context on human cognition and emotional responses [

34,

35]. For example, top-down processing theories [

36,

37] illustrate how prior knowledge and expectations shape our interpretation of sensory information in an environment. While insights in embodied cognition highlight how physical interactions with our environments shape our emotional responses to different architectural features, underscoring the role of bodily experience in shaping perceptions. Appraisal theories [

38], further explain how individuals evaluate and interpret environmental stimuli, linking these appraisals to affective responses. Despite growing interest in using generative AI for architectural design and well-established theory in visual processing, limited research explored the extent to which these artificially generated image quantitatively align with human perception and emotional response.

These related works and cognitive theories have inspired this research, which aims to investigate how accessible and open-source pretrain generative image models align with human perception. The research conducts two experiments: the first examines geographical consistencies, and the second compares objective and affective perceptual characteristics of synthetic imagery.

3. Methodology

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) [

39] have emerged as a widely-used generative model for text-to-image generation in architectural design [

7]. One popular variant is the Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) [

19], which performs the diffusion process over a learned latent representation of the image (obtained via a pre-trained Variational Autoencoder VAE) instead of directly in pixel space. In a LDM, a U-Net architecture [

40] is then tasked with predicting the Gaussian noise added to the latent representation at each diffusion step

t. By iteratively subtracting the predicted noise in reverse (starting from a noisy latent and moving toward a clean latent), the model progressively denoises the latent and eventually reconstructs the image. The LDM is trained using a squared loss to match the predicted noise to the true noise added at each step. Formally, this is given by;

where

is the Gaussian-distributed

noise added to the latent,

is the predicted noise from a pretrained UNet[

40] at each time step t. Here,

is the latent embedding of the image

x from the encoder

of a pretrained Variational Autoencoder [

41] and

c is the condition information, in this case the text-prompt that guides the generation. The text prompt is encoded using a CLIP-based text encoder with cross-attention layers.

In this research, we leverage on the popular and accessible LDM called SDXL [

42] pretrained on the LAION-5B dataset [

43], to study the alignment between generated architectural imagery and human descriptions. SDXL is a LDM from StabilityAI, which uses a larger backbone than previous Stable Diffusion Variant such as SD1.5 resulting in improve performance. For more details please see [

42].

Other deep generative models were consider including Stabe Diffusion variants such as SD3 and recent Flow-based architecture such as Flux [

44]. SDXL [

42] is selected as it achieves high image quality while being more open-source

1, more mature and more accessible than other Stable Diffusion and Flow-based variant. We also did not consider entirely close-source, commercial tools like MidJourney, due to costs and reproduceability, but plan to benchmark against these commercial image generators in future research.

3.1. Model Pipeline

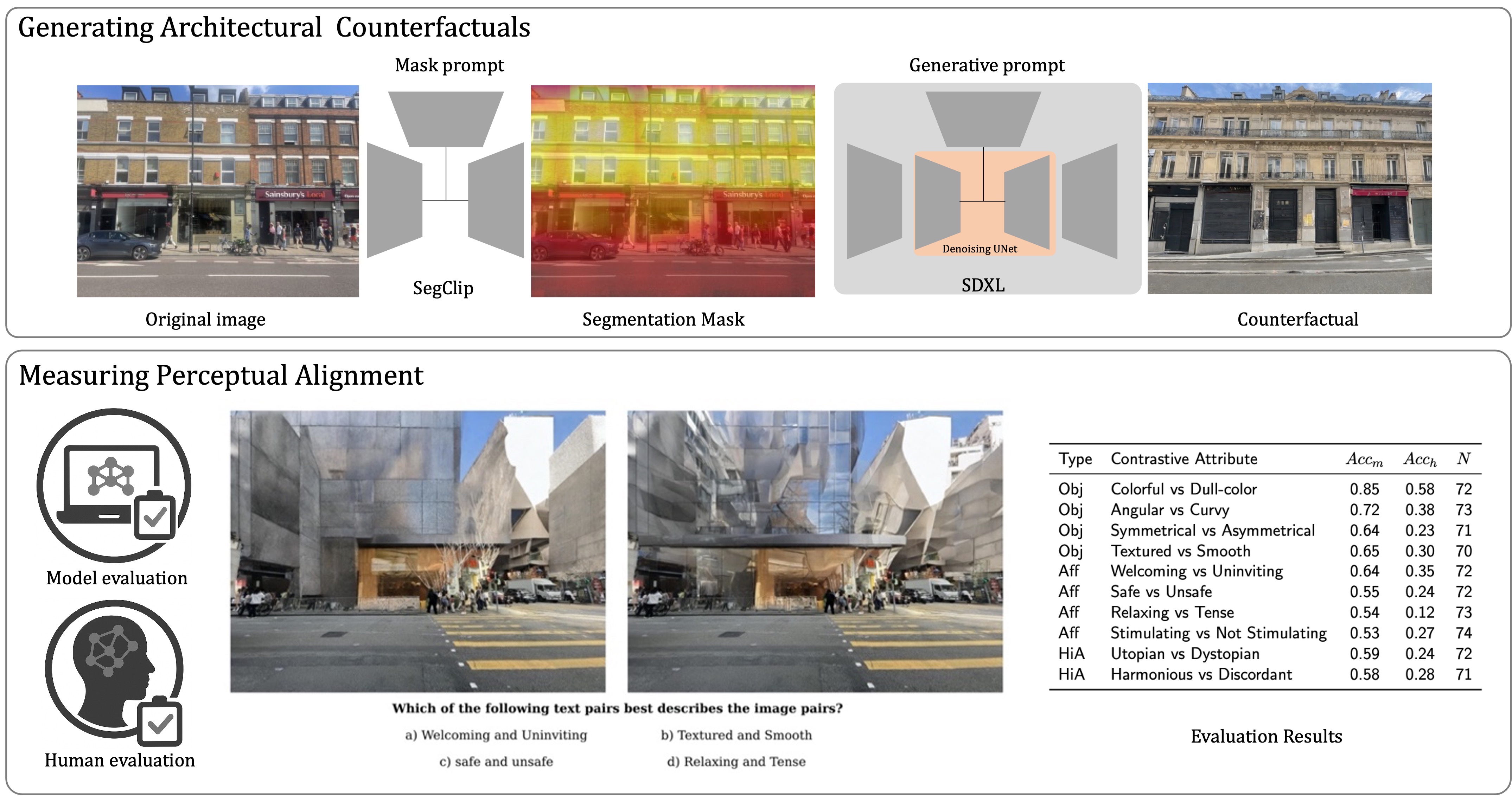

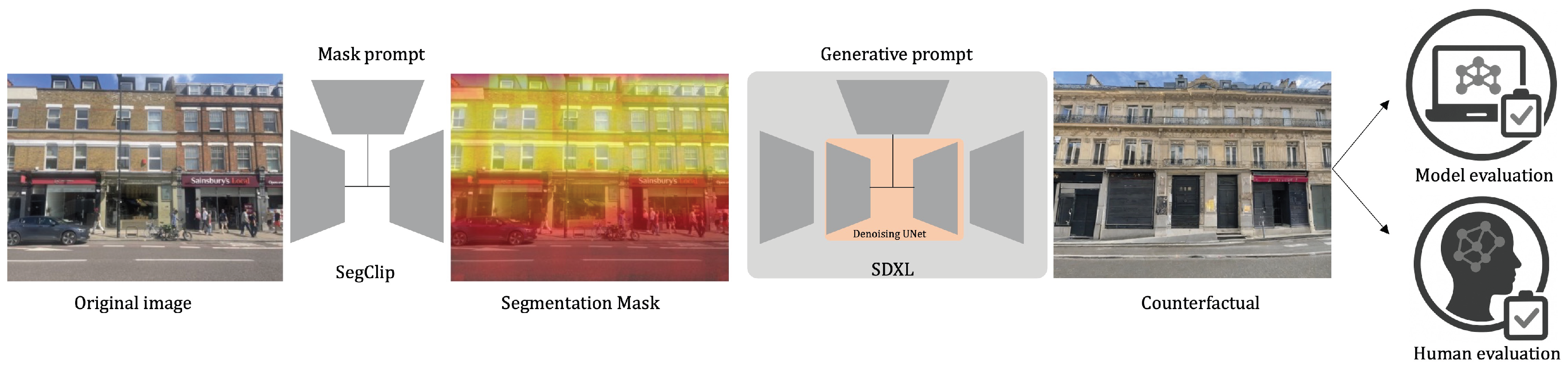

The end-to-end model pipeline generates a counterfactual image on the basis of three inputs, namely: the original image, a mask text-prompt and a generative text prompt as shown in

Figure 1. The pipeline consists of three components: (1) the image segmentation module, (2) the image generation module and (3) the image evaluation module. We tested the end-to-end model pipeline to assess the alignment abilities of these generative models. We focus on open-source-weight and lightweight models for all components due to greater control over model parameters, lower computational costs, reproducibility, and accessibility.

The image segmentation module (1) is based on a semantic segmentation model called ClipSeg due to its simplicity [

45]. The model generates a segmentation mask given a mask prompt which is then use to localise the image generation in the next stage. The modular design of the pipeline enables the integration of alternative segmentation modules in future work, including the widely adopted GroundingDINO approach.[

46].

The image generation module (2) is based on a variant of LDM called SDXL [

42]. The model takes the mask generated in (1), a generative text prompt and the original image to generate a localise counterfactual (inpainting) of the original image. We use default components for the model including a pretrained VAE as the encoder-decoder, a pretrained denoising UNet for the diffusion process. We qualitatively select two hyper-parameters (guidance scale, strength) based on image quality as shown in the parameter study section. We also experiment with Lora [

47] for parameter efficient fine tuning and ControlNet [

48] for control generation with a canny edge map. We decide first to focus on pretrain model results to better understand the performance and biases of accessible and open source generative image model and secondly to exclude the canny-edge map controls, as it was restrictive given some of the affective text prompts and unnecessary as inpainting is applied.

The image evaluation module (3) consists of two types of validation. The first is model-based evaluation, where we evaluate using a pretrained vision model to test whether the generated image predicted class matches the ground-truth class. The second is a human-based evaluation where evaluators will judge whether the generated image aligns with the ground-truth class or not. Accuracy, between ground truth and the predicted, is the main evaluation metric for text-to-image alignment given the largely balanced class. Before describing the experiments, parameter analysis is first conducted.

4. Parameter Analysis

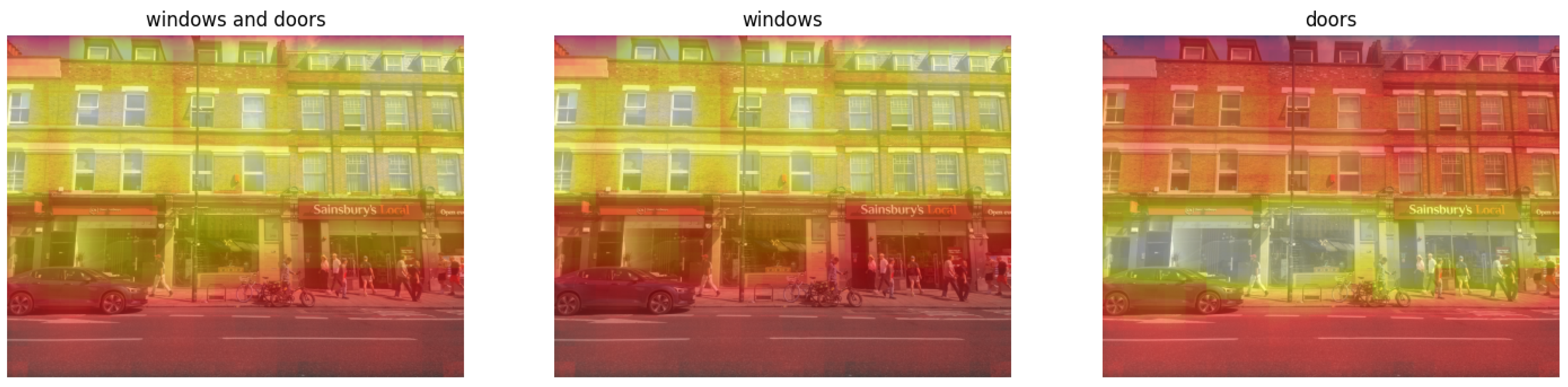

4.1. Mask Prompt for Localised Inpainting

To restrict edits to building façades while preserving the rest of the scene, the modelling pipeline employs targeted inpainting using a mask prompt with SegClip.

Figure 2 shows three prompt variants namely; ’windows’, ’windows and doors’, and ’doors’. ’Windows and doors’ is selected as the base prompt as it covers both the upper floors and ground floors.

Figure 3 presents the original image from Amsterdam alongside two synthesize counterfactual images whose building facade has been transform to Hong Kong: one without localise inpainting, which introduce unrealistic global changes (such as concrete covering the canal or changing the shape of the road), and another produced with inpainting, which successfully constrain alterations to architectural features on the building facade.

Here is another example.

Figure 4 shows the original image from San Francisco alongside two synthesize counterfactual images of Kyoto: one generated without localise inpainting, resulting in the entire road changing shape, and another produce with targeted inpainting, effectively limiting the alterations exclusively to the building facade.

To explore this further, we selected 5 random images and generated 10 synthetic geographical variants(similar to the first geolocalisation experiment), with and without inpainting. We then asked the question: to what extent do the synthesize image (with or without inpainting) largely preserve the contextual quality of the original image? The qualitative results show that 36 out of 50 images maintain a good level of contextual coherence without inpainting while all 50 out of 50 images with inpainting as expected. These results indicate that, inpainting is necessary to prevent significant alterations to the image context. However, these result also suggests that the current hyper-parameters and prompts largely preserve the original context without inpainting. In certain cases, the counterfactuals even introduce visual elements characteristic of the target context — for example, overhanging cables in Tokyo. As this research focuses specifically on generating counterfactuals of building facades, we decide to select the inpainting method to minimise significant contextual change. Future research can relax this assumption.

4.2. Image Diversity

We further study the diversity of generated images by varying the random seed during synthesis.

Figure 5 illustrates an example where an image of Shanghai’s building facade (left) was transformed into Paris, Tokyo, and Kyoto, each generated using two different random codes (between 0-

). The two rows of images for each target city display consistent, geo-specific urban features—such as the Haussmannian facades characteristic of Paris, Kyo-machiya architecture typical of Kyoto, and a mix of modern and traditional buildings in representing Tokyo.

To explore this further, we similarly selected 5 random images and generated 10 synthetic variants, each representing different geography with two random codes (between 0-). We then asked the question: to what extent do the synthesized pair of images produce different architecture while being consistent to the prompt? The qualitative results show that 50 out of 50 pair of images show significant architectural difference. These results demonstrate that the generated images are both plausible and well-align with their geographical prompts, while also exhibiting visual diversity. We will also be reporting the geolocalisation experiment using the random style code(between 0-) as an ablation.

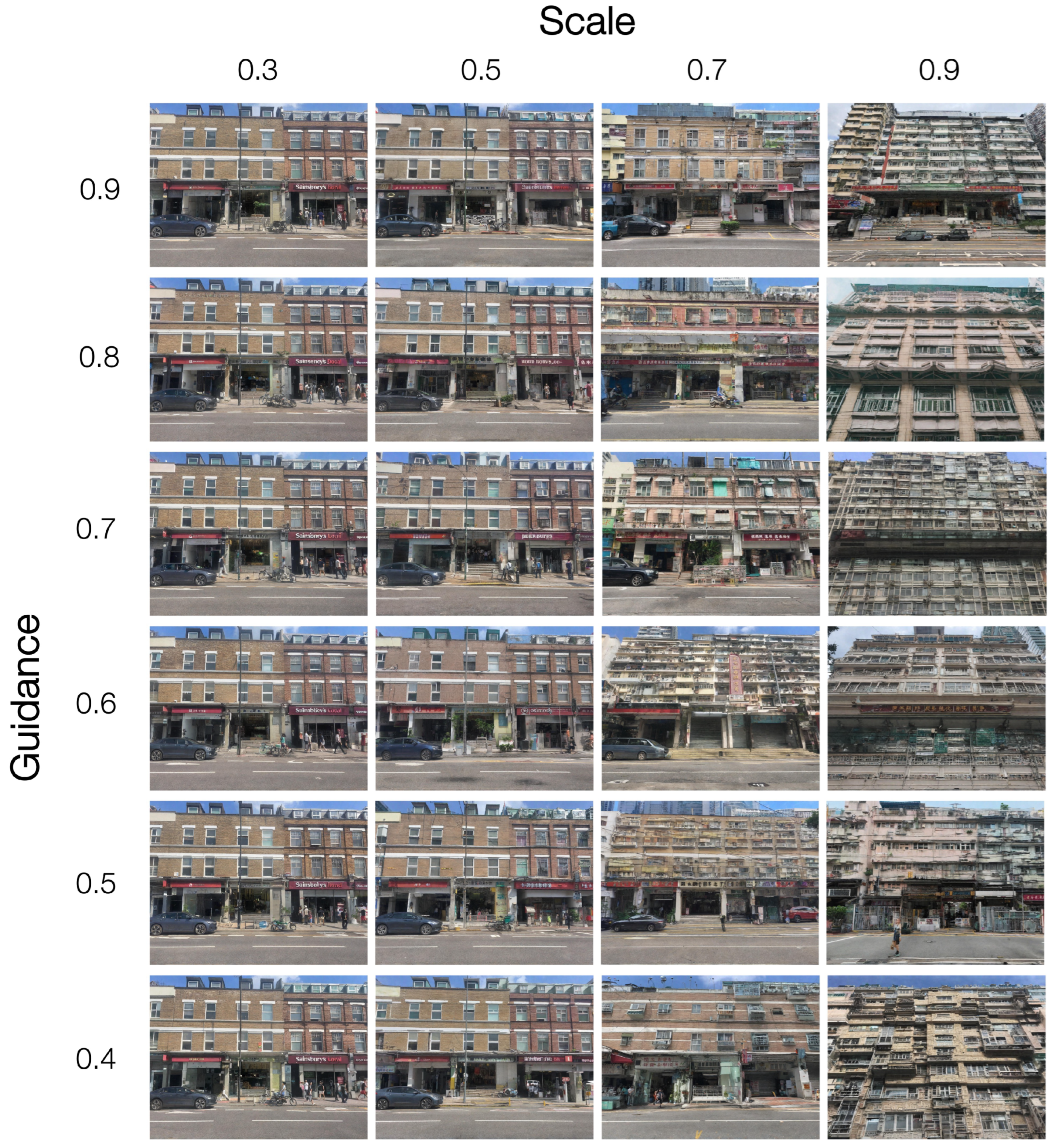

4.3. Guidance and Scale Parameters

Furthermore, we conducted a simple visual ablation study to describe the effects of varying the guidance (

g) and scale (

s) parameters on image generation. Higher guidance encourages the model to generate images that better align with the text prompt, while the scale parameter controls the degree of transformation apply to the reference image. We synthesize an image of London, modifying the building facades to resemble those in Hong Kong, using different combinations of these hyper-parameters as shown in

Figure 6. The results show that when

, the entire image changes excessively, while for

, the transformation is insufficient. Holding

constant, we observe that the generated images are more plausible when

. Based on these observations, we select

and

as the default parameters for our generative process.

5. Experiments

5.1. Geolocalisation Experiment

The ability to interpret and synthesize geo-aware architectural detail is important to both recognise regional biases but also in creating contextually-aware architectural designs. This connects to the broader field of planet-scale image geolocalisation which is an important task in GIScience and computer vision with use cases in autonomous driving, disaster management and human navigation. To test the model’s efficacy in producing geographically consistent street scenes, we conduct a geolocalisation(`GeoGuesser`) experiment. For this experiment, we curate a dataset of 120 architectural façade images from 10 cities: [’Hong Kong’, ’Seoul’, ’Tokyo’, ’Kyoto’, ’Shanghai’, ’San Francisco’, ’Paris’, ’Amsterdam, ’Vienna’, ’London’]. Using the model pipeline described in the methodology section, we generated

counterfactual images based on ten geo-specific text-prompts with one iteration using a fixed latent code and another using a random latent code. As there are no significant deviations between the two, subsequent experiments will use the single latent code for style consistency. The text prompts used for the synthesis are "a photo of a building in

" and the mask prompts are "windows and doors" to localise the image interventions on the building façade. Simple variants of the prompts are tested in the parameter study section. In the future, more optimise prompts will be tested [

49]. We then evaluated the alignment of the synthetic images with the geolocation text prompts using model-based evaluation. Specifically, we use a Clip-based contrastive learning model called GeoClip [

50], that was design to infer for each image the probabilities of its location as a ten-cities zero-shot classification problem. We validate the pretrain model on the original dataset as ground-truth, achieving an accuracy of

.

5.2. Perceptual Alignment Experiment

Understanding how humans perceive and respond to architectural features is important for evaluating AI-generated designs. This research will also study how AI-generated imagery from perceptual text prompts align with both human and machine evaluations. The theory-inspired perceptual text prompts are classified into three categories: (i) Objective Verbal Descriptors, (ii) Affective Verbal Descriptors, and (iii) Higher-order Affective Verbal Descriptors. These categorisation aligns with established theories of visual processing and cognition such as Feature Integration theory that supports the effectiveness of objective descriptors by explaining how basic visual features are detected and integrated, and Dual-Process Theories [

51,

52,

53] which highlight how affective descriptors engage automatic, emotional responses (System 1), while higher-order descriptors involve more deliberate, cognitive evaluation (System 2). This hierarchical structure effectively captures the progression from concrete, observable features to more abstract and emotionally nuanced interpretations, improving our understanding of human engagement in architecture. For this research, we hypothesized that AI-generated imagery will show stronger alignment with objective verbal descriptors, followed by affective and higher-order verbal descriptors. The reason being that AI models primarily rely on pattern matching, which makes them adept at generating objective architectural features but may overlook the subtleties and variance of human emotions and abstract cognitive evaluations derived from embodied lived experience.

5.3. Perceptual Text Prompts

From an initial list of 15 contrastive pairs, we selected 10 pairs based on maximising the cosine distance of the contrastive word embeddings [

54]. This is to ensure that the word-pairs are as different as possible, thereby minimising overlaps.

Objective Verbal Descriptors(4 pairs): These descriptors focus on tangible attributes such as "Colorful vs Dull", "Angular vs Curvy", "Symmetrical vs Asymmetrical" and "Textured vs Smooth" as they correspond well with with Low-Level Visual Processing theories such as Feature Integration Theory, which detects basic visual features.

Affective Verbal Descriptors(4 pairs): These descriptors like "tense vs. relaxing", "welcoming vs. uninviting", " stimulating vs. not stimulating" and "safe vs. unsafe" introduce an emotional dimension that aligns with Intermediate-Level Visual Processing and Affective Appraisal Theories. These descriptors engage in emotional responses that are more subjective but still fundamental in perception.

Higher-order Affective Verbal Descriptors(2 pairs): These descriptors such as "harmonious vs. discordant" and "utopian vs. dystopian" require deeper cognitive and emotional processing, fitting well with High-Level Visual Processing and Top-Down Processing Theories. These descriptors involve more complex interpretations often influenced by cultural and personal contexts.

5.4. Model-Based Evaluations

Using the same set of 120 architectural façade images, we generated 2400 counterfactual images by applying 10 contrastive text prompts ("colorful vs. dull"), each with a single latent code. Each synthetic image is created using the following text prompt, "a photo of a building with

façade and

architectural details", where the

correspond to the 10 perceptual text prompts defined in the last section. For model-based evaluation, we evaluate the extent each synthetic image aligns with its intended text prompts as opposed to its contrasting term using Siglip [

55], a more powerful variant of CLIP, as a zero-shot classifier.

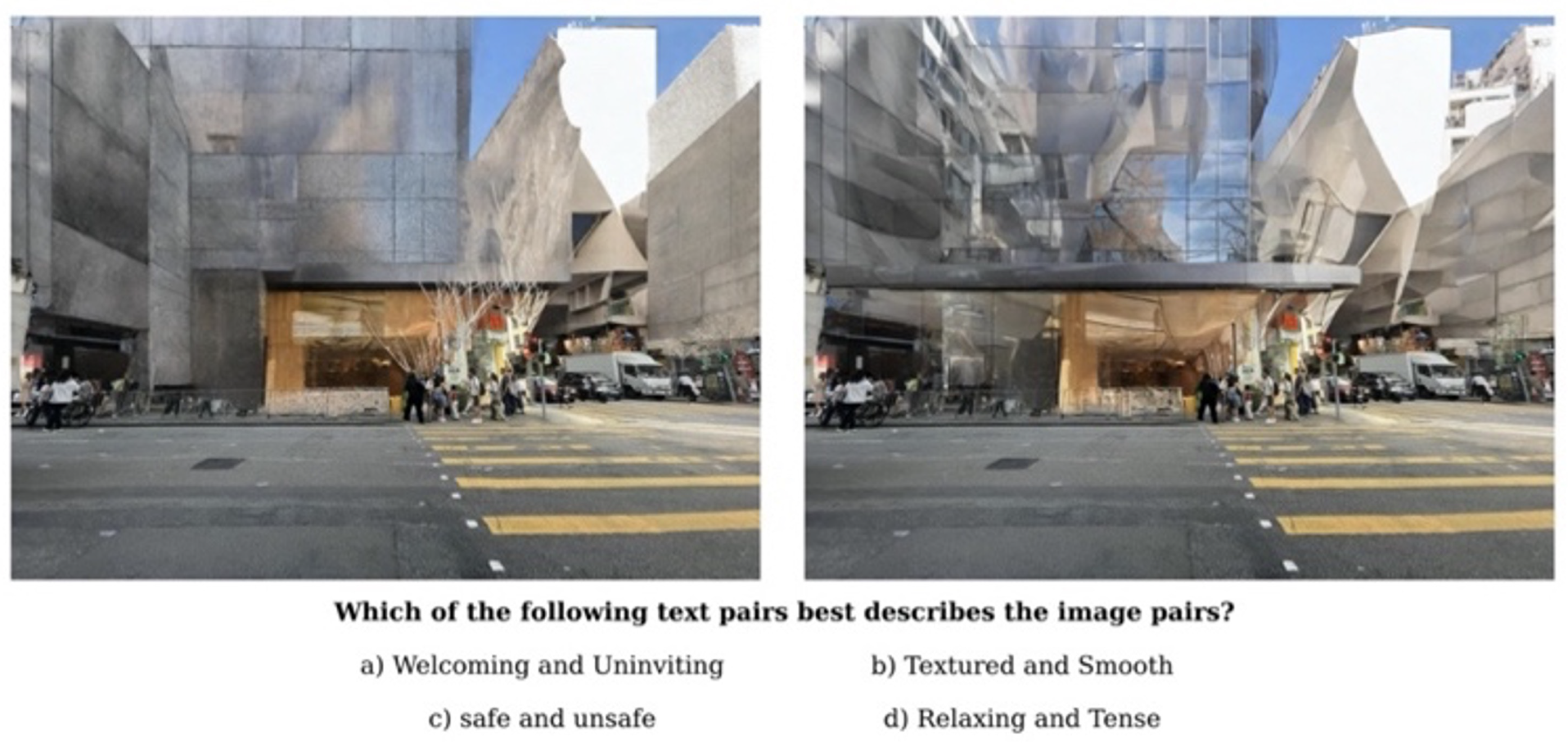

5.5. Human-Based Evaluation

To complement the model-based evaluations, we conducted a self-reported human-based evaluations, to gauge the perceptual response of the generated images. We designed a multiple-choice task as a pilot experiment in linking perceptual descriptors with the synthesize images. We proceed with the following procedures: (i) select 10 contrastive-text pairs (objective, affective, higher order affective); (ii) generate 30 image-pairs derived from 6 base images; (iii) for each image-pair, generate four multiple choice options (one correct and three incorrect answers shown in

Figure 2); (iv) present the image-pairs to 25 participants. After removing participants who complete only a single rating, we gathered a total of 720 user ratings. This was performed using AMT mechanical turk. An example of the multiple-chocie survey can be seen in

Figure 7. After both the model-based and human-based evaluation, we will explore how the two methods covary to generate preliminary insights and identify any systematic biases.

6. Results

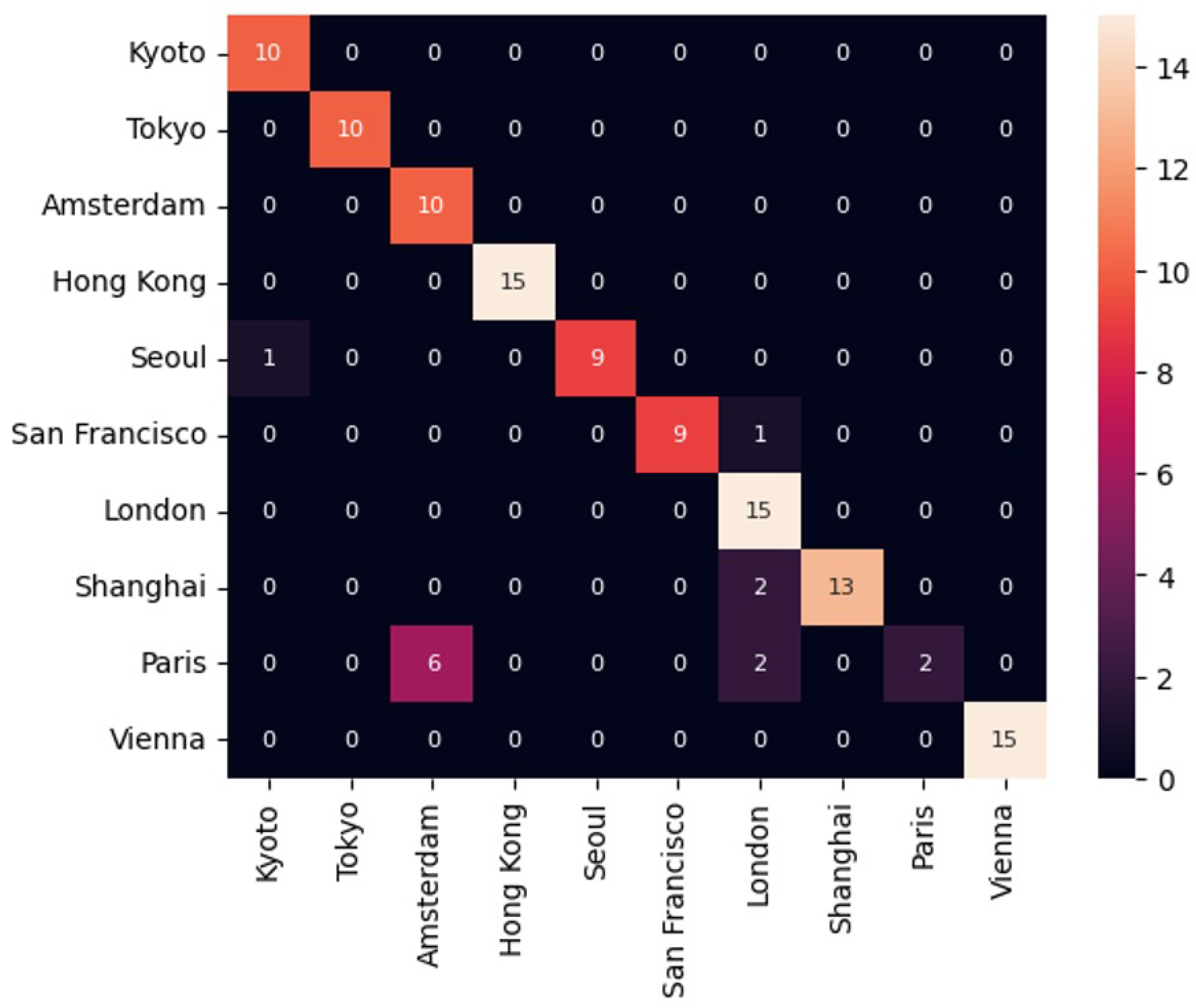

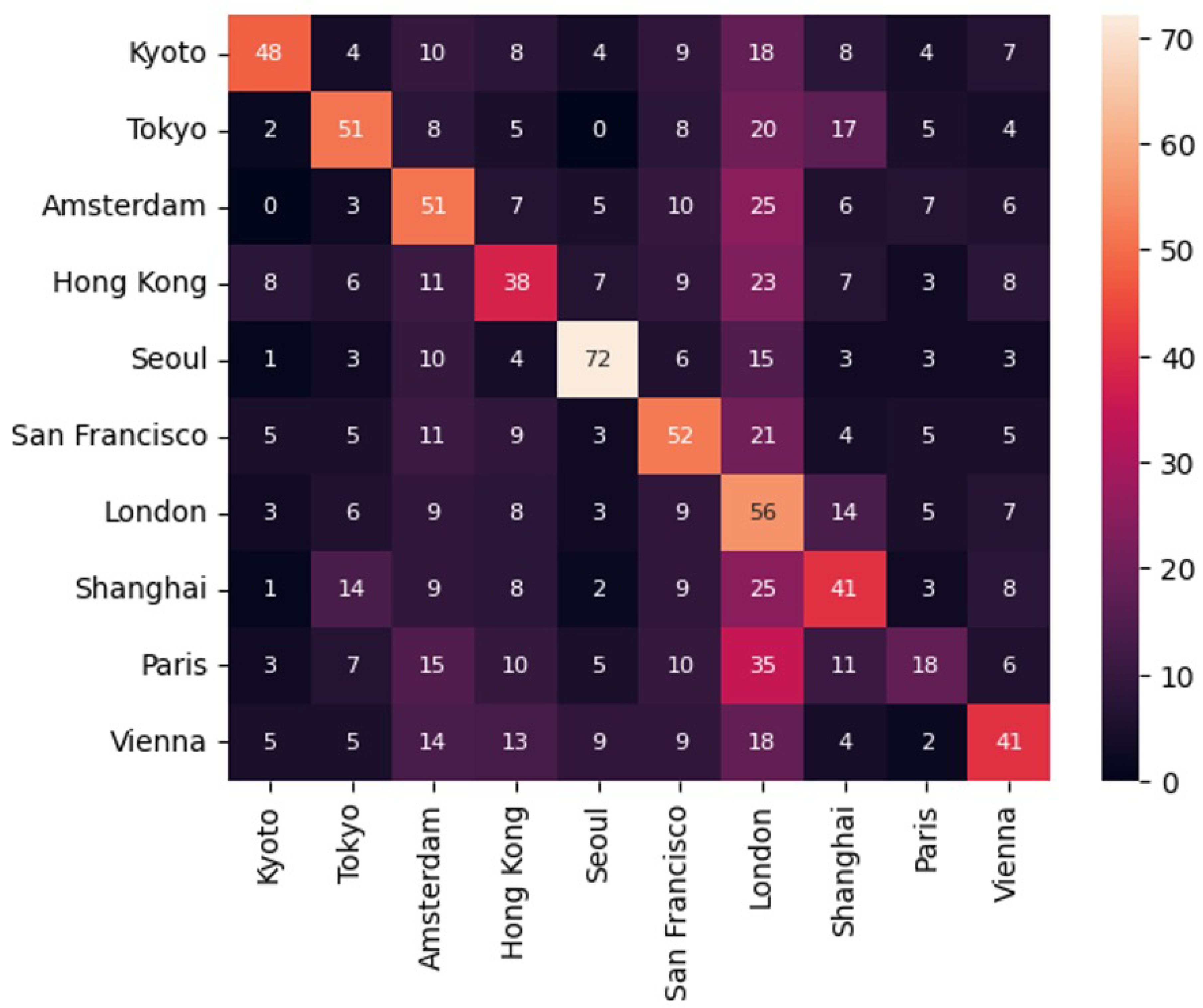

6.1. Geolocalisation Experiment

The results of the geolocalisation experiment show that the generative model achieve an accuracy of

across the ten cities, reflecting a moderate capability of generating geographically plausible counterfactuals. This performance remains below that of the baseline model on existing images, which achieve an accuracy of

.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 presents the confusion matrix for the existing and the generated images, where the model is visibly over-predicting for London counterfactuals. We further conduct subgroup analysis for the five East Asian cities and five Western cities. The Western subset shows higher accuracy (acc

) compare to the East Asian counterparts(acc

). These results suggest the generative models possibly illustrate some regional biases in its pretraining data. To explore these patterns, we visualise a successful and failure example, with the left image as the original image, follow by generated images of London and Kyoto respectively. The top row of

Figure 10 shows a neoclassical building in Paris as the original, alongside a similar neoclassical building in London and a more distinct East Asian style building for Kyoto. These results highlight the nuance and similarities between London and Paris but also demonstrating the model’s capacity to produce architectural details that are more distant away like in Kyoto. In contrast, the bottom row as shown in

Figure 11, presents a mixed-use building in Shanghai as the original, while the two geographical counterfactuals lack distinctive design features that emphasize this difference.

6.2. Perceptual Experiment

The perceptual experiment results are summarise in

Table 1. Starting with model evaluation, we observe that prompts involving objective descriptors - those requiring less visual processing - tend to achieve higher accuracy such as colourful/dull (acc

) and angular/curvy (acc

). In contrast, affective prompts which require more nuanced visual processing show lower accuracy, such as relaxing/tense (acc

) and harmonious/discordant (acc

). For multi-class problem, objective descriptors such as colours (acc

) and materials (acc

) have notably higher accuracy compare to more complex affect descriptors

2 (acc

).

Table 1.

Classification Accuracy for Contrastive Attributes. Objective descriptors (Obj) consistently outperform affective (Aff)and higher-order affective descriptors(HiA) in both human() and model() accuracy, indicating AI models can reproduce observable visual patterns more reliably than abstract perceptual experiences.

Table 1.

Classification Accuracy for Contrastive Attributes. Objective descriptors (Obj) consistently outperform affective (Aff)and higher-order affective descriptors(HiA) in both human() and model() accuracy, indicating AI models can reproduce observable visual patterns more reliably than abstract perceptual experiences.

| Type |

Contrastive Attribute |

|

|

N |

| Obj |

Colorful vs Dull-color |

0.85 |

0.58 |

72 |

| Obj |

Angular vs Curvy |

0.72 |

0.38 |

73 |

| Obj |

Symmetrical vs Asymmetrical |

0.64 |

0.23 |

71 |

| Obj |

Textured vs Smooth |

0.65 |

0.30 |

70 |

| Aff |

Welcoming vs Uninviting |

0.64 |

0.35 |

72 |

| Aff |

Safe vs Unsafe |

0.55 |

0.24 |

72 |

| Aff |

Relaxing vs Tense |

0.54 |

0.12 |

73 |

| Aff |

Stimulating vs Not Stimulating |

0.53 |

0.27 |

74 |

| HiA |

Utopian vs Dystopian |

0.59 |

0.24 |

72 |

| HiA |

Harmonious vs Discordant |

0.58 |

0.28 |

71 |

Table 2.

Model-based Classification Accuracy for Different Multi-class Categories where similarly Objective descriptors (Obj) outperform affective (Aff) ones.

Table 2.

Model-based Classification Accuracy for Different Multi-class Categories where similarly Objective descriptors (Obj) outperform affective (Aff) ones.

| Type |

Multi-class Category |

|

| Obj |

Red-green-blue-yellow-purple-orange |

0.86 |

| Obj |

Brick-glass-stone-wood |

0.65 |

| Aff |

Exciting-depressing-calm-stressful |

0.36 |

We then present the human evaluation results whose accuracy is generally lower than the model evaluation counterparts suggesting the difficulty of the multiple choice task. Objective tasks show stronger alignment with human responses, as seen with colorful/dull (acc) and angular/curvy (acc) as compared to affective tasks such as safe/unsafe (acc) and stimulating/non-stimulating (acc). There are some outliers such as symmetrical/asymmetrical (acc) which display lower accuracy despite being an objective descriptor. Additionally, there are minimal differences between affective and higher-order affective descriptors for both model and human evaluations.

We similarly plot an objective counterfactual pairs (

Figure 12, left) and an affective pairs (

Figure 12, right). The results indicate that images generated from objective prompts are visually more distinctive than those generated from affective prompts. For example, images produced with the contrasting prompts such as "Stone and Glass" are more easily distinguishable than those produced with “calm and stressful”.

7. Discussion

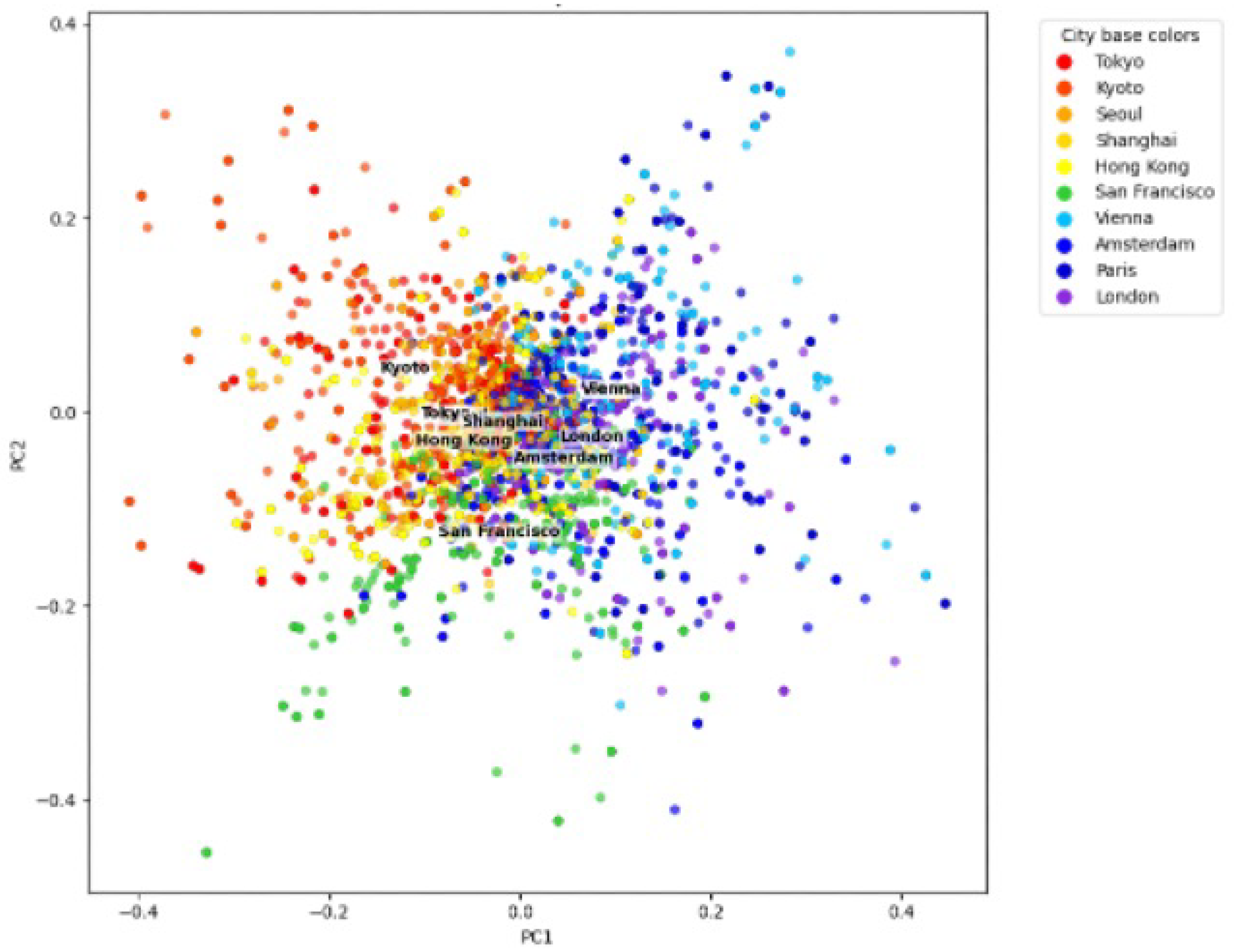

In summary, this study explores the extent to which generative architectural facade imagery aligns with two aspects of human architectural understanding: geographical location and perceptual descriptions. Results from the first experiment indicate that these generative models have implicitly learn some geographical context. Descriptively, the models successfully generated architectural details that are relevant for its location. For example, the neoclassical windows in European cities - "what makes Paris look like Paris?" [

57]. However, we also observe that these generative models performed better for certain regions. To further interpret, we visualised the first and second principal components of the counterfactual embeddings, colouring each point by its counterfactual city and labelling the centroid of each city cluster. As this is an inpainting exercise, we difference out its original city principal components value before visualising. The results show clustering between cities that are near to each other geographically like ’Kyoto’ and ’Tokyo’ or ’Shanghai’ and ’Hong Kong’ or ’London’ and ’Paris’ as shown in

Figure 13. However, the results also show entanglement between the geographical clusters. The underlying reason needs to be fully explore in future research but the model’s training dataset are likely to contain regional biases [

42] where more careful fine-tuning is needed.

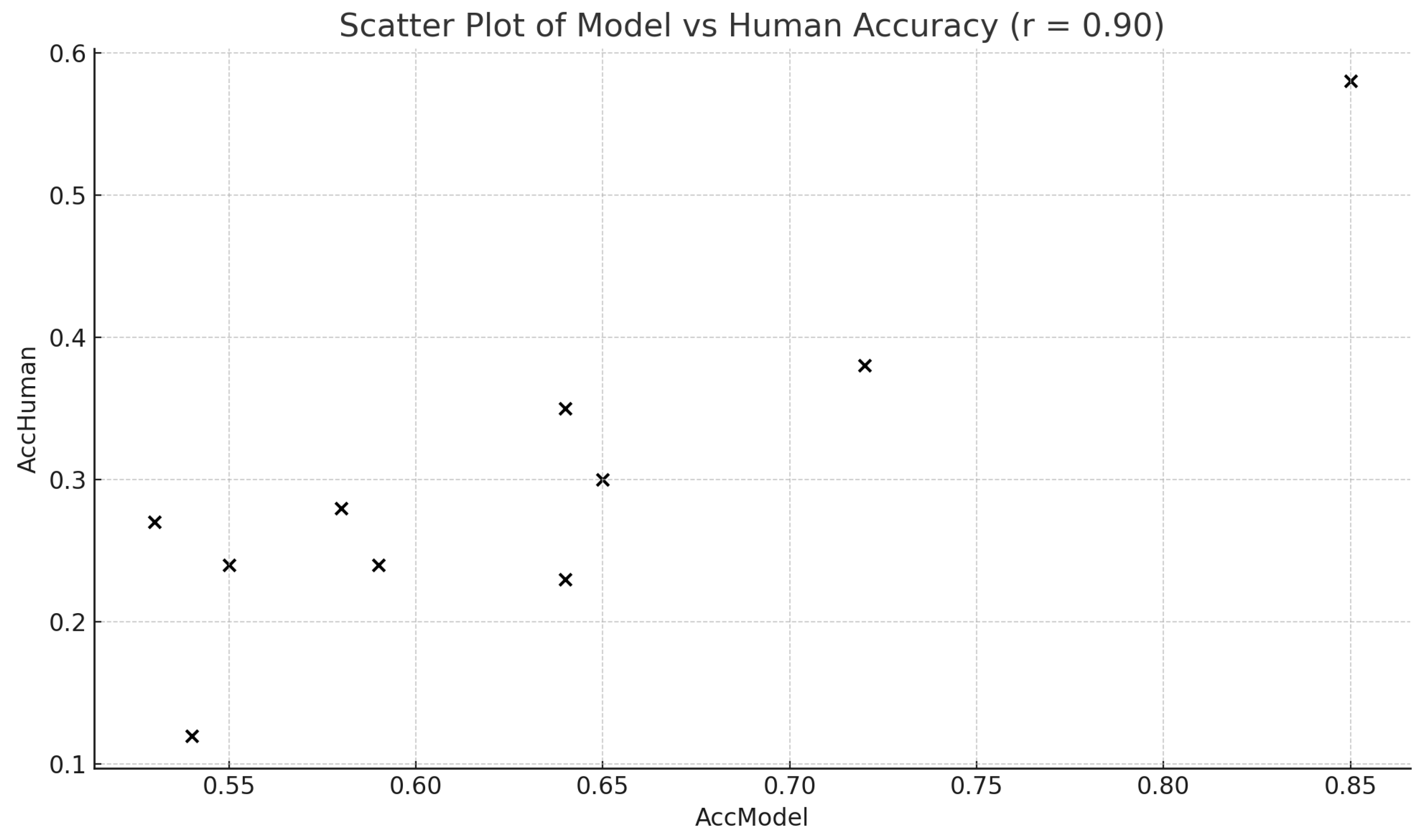

The results from the second experiment show that these generative models can produce images that are better at aligning with more objective descriptors (e.g., colourful/dull) and less well for affective descriptors (e.g., relaxing/tense) as hypothesized. Contrary to our initial conjecture, we found no significant difference between affective and higher-order affective descriptors. Despite some disagreements (e.g., symmetric/asymmetric), the overall trends between human-based and model-based assessments show relative correspondance as shown in

Figure 14(

). These results highlights and reaffirms the potential in leveraging "MLLM-as-a-Judge" [

58] to complement human evaluations and enhance the scalability of perceptual assessments.

8. Conclusion

Our study contributes to recent behavioural research in Generative AI by examining how well machine-generated architectural images align with human perceptions. Specifically, we found notable alignment but also discrepancies for both the geolocalisation task and the perceptual alignment task. The discrepancy in objective and affective alignment can be explained in multiple ways. Computationally, lower performance in the affective task may be related to model expressivity and training data biases, where open source LDM pretrained on the well established LAION-5B dataset [

43] may lack exposure to patterns of say stressful architecture (e.g. broken windows). This can potentially be further-study through other generative models including commercial ones (eg. MidJourney) and fine-tuning with human feedbacks on perceptual data in architecture [

59].

On the other hand, these discrepancies suggest architectural perception may involve higher-order top-down cognitive processes. Models without embodiment, experience, or memory are not expected to produce affective imagery, as these qualities shape how humans emotionally feel towards architecture. Affective imagery are likely to be more heterogenous and varied than the objective ones. For example, how we perceive "dystopian" or "stressful" can vary significantly dependent on our experience and culture. A deeper investigation can involve more embodied prompt reasoning, and the integration of multimodal inputs within these generative systems [

49] (eg. bio/neural-feedbacks).

Future research will continue to investigate these conjectures and examine whether more embodied AI systems can address these higher-order cognitive tasks. In exploring the alignment and discrepancies between AI-generated imagery and human perception, we emphasize the richness of human engagement with architectural spaces. This has particular relevance for automation in construction, where generative design tools should meaningfully support human-center design.

At the same time, we must be aware of the risks: AI-driven global standardisation can potentially limit design diversity and reduce context-aware cultural design principles (eg. erode vernacular building traditions) leading to potentially homogenous design solutions. Integrating these tools into automated design workflows will require careful attention to these perceptual gaps to ensure AI-generated outputs remain contextually and emotionally-aware. To address this, designers are encourage to treat AI as a context-aware design tool to assist (eg. automating routine tasks) rather than replace human creativity and critical thinking in the design loop. This is not only important in the design workflow but also in educating the next generation of designers.

By highlighting both the opportunities and limitations of current AI in fully capturing the complexity of lived experience, this paper offers not only a framework for evaluating perceptual and emotional alignment in synthetic imagery, but also serves as a reflection in human’s complex engagement with the built environment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT for grammar correction. The authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT by OpenAI for checking grammer. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, C. A new theory of urban design; Vol. 6, Center for Environmental Struc, 1987.

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The social logic of space; Cambridge university press, 1989.

- Batty, M.; Longley, P.A. Fractal cities: a geometry of form and function; Academic press, 1994.

- Koenig, R.; Miao, Y.; Aichinger, A.; Knecht, K.; Konieva, K. Integrating urban analysis, generative design, and evolutionary optimization for solving urban design problems. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 2020, 47, 997–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, T. Model-based Optimization for Architectural Design: Optimizing Daylight and Glare in Grasshopper. Technology|Architecture+Design 2017.

- Vermeulen, T.; Knopf-Lenoir, C.; Villon, P.; Beckers, B. Urban layout optimization framework to maximize direct solar irradiation. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2015, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Roh, H.; Lee, G. Generative AI in architectural design: Application, data, and evaluation methods. Automation in Construction 2025, 174, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, Y.I.; Müller, P. Procedural modeling of cities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, 2001, pp. 301–308.

- Müller, P.; Wonka, P.; Haegler, S.; Ulmer, A.; Van Gool, L. Procedural modeling of buildings. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2006 Papers; 2006; pp. 614–623.

- Jiang, F.; Ma, J.; Webster, C.J.; Chiaradia, A.J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X. Generative urban design: A systematic review on problem formulation, design generation, and decision-making. Progress in planning 2024, 180, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Communications of the ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2223–2232.

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Analyzing and improving the image quality of stylegan. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 8110–8119.

- Hartmann, S.; Weinmann, M.; Wessel, R.; Klein, R. Streetgan: Towards road network synthesis with generative adversarial networks 2017.

- Chaillou, S. Archigan: Artificial intelligence x architecture. In Proceedings of the Architectural intelligence: Selected papers from the 1st international conference on computational design and robotic fabrication (CDRF 2019). Springer, 2020, pp. 117–127.

- Wu, W.; Fu, X.M.; Tang, R.; Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.H.; Liu, L. Data-driven interior plan generation for residential buildings. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2019, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.N.; Biljecki, F. GANmapper: geographical data translation. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2022, 36, 1394–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.; Hasegawa, R.; Paige, B.; Russell, C.; Elliott, A. Explaining holistic image regressors and classifiers in urban analytics with plausible counterfactuals. International Journal of Geographical Information Science 2023, 37, 2575–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 10684–10695.

- Ma, H.; Zheng, H. Text Semantics to Image Generation: A method of building facades design base on Stable Diffusion model. In Proceedings of the The International Conference on Computational Design and Robotic Fabrication. Springer, 2023, pp. 24–34.

- Zhou, F.; Li, H.; Hu, R.; Wu, S.; Feng, H.; Du, Z.; Xu, L. ControlCity: A Multimodal Diffusion Model Based Approach for Accurate Geospatial Data Generation and Urban Morphology Analysis. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2409.17049 2024.

- Shang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, H.; Ding, J.; Feng, J.; Chen, J.; Tian, L.; Li, Y. UrbanWorld: An Urban World Model for 3D City Generation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2407.11965 2024.

- Zhuang, J.; Li, G.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Tian, R. TEXT-TO-CITY: controllable 3D urban block generation with latent diffusion model. In Proceedings of the ACCELERATED DESIGN, Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for ComputerAided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) 2024. Presented at the CAADRIA, 2024, pp. 169–178.

- Cui, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, S. Learning to generate urban design images from the conditional latent diffusion model. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, R. Generating accessible multi-occupancy floor plans with fine-grained control using a diffusion model. Automation in Construction 2025, 177, 106332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.A.; Hosseini, S.; Furukawa, Y. Housediffusion: Vector floorplan generation via a diffusion model with discrete and continuous denoising. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 5466–5475.

- Zhang, Z.; Fort, J.M.; Mateu, L.G. Exploringthe potential of artificial intelligence as a tool for architectural design: A perception study using gaudí’sworks. Buildings 2023, 13, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Chen, W.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H. Image inpainting using diffusion models to restore eaves tile patterns in Chinese heritage buildings. Automation in Construction 2025, 171, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.R.; Haworth, J.; Cheng, T. Understanding cities with machine eyes: A review of deep computer vision in urban analytics. Cities 2020, 96, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljecki, F.; Ito, K. Street view imagery in urban analytics and GIS: A review. Landscape and Urban Planning 2021, 215, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesses, P.; Schechtner, K.; Hidalgo, C.A. The collaborative image of the city: mapping the inequality of urban perception. PloS one 2013, 8, e68400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, N.; Philipoom, J.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C. Streetscore-predicting the perceived safety of one million streetscapes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2014, pp. 779–785.

- Dubey, A.; Naik, N.; Parikh, D.; Raskar, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. Deep learning the city: Quantifying urban perception at a global scale. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer, 2016, pp. 196–212.

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The experience of nature: A psychological perspective; Cambridge university press, 1989.

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the natural environment; Springer, 1983; pp. 85–125.

- Gregory, R.L. The intelligent eye. 1970.

- Neisser, U. Cognitive psychology: Classic edition; Psychology press, 2014.

- Scherer, K.R. Appraisal theory. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion/John Wiley & Sons 1999.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9 2015, proceedings, part III 18. Springer, 2015; pp. 234–241.

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 2013. Presented at the 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2014.

- Podell, D.; English, Z.; Lacey, K.; Blattmann, A.; Dockhorn, T.; Müller, J.; Penna, J.; Rombach, R. Sdxl: Improving latent diffusion models for high-resolution image synthesis. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2307.01952 2023.

- Schuhmann, C.; Beaumont, R.; Vencu, R.; Gordon, C.; Wightman, R.; Cherti, M.; Coombes, T.; Katta, A.; Mullis, C.; Wortsman, M.; et al. Laion-5b: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 25278–25294. [Google Scholar]

- Labs, B.F. FLUX. https://github.com/black-forest-labs/flux, 2024.

- Lüddecke, T.; Ecker, A. Image segmentation using text and image prompts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 7086–7096.

- Liu, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; et al. Grounding dino: Marrying dino with grounded pre-training for open-set object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2024; pp. 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2106.09685 2021.

- Zhang, L.; Rao, A.; Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp.

- Hao, Y.; Chi, Z.; Dong, L.; Wei, F. Optimizing prompts for text-to-image generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco Cepeda, V.; Nayak, G.K.; Shah, M. Geoclip: Clip-inspired alignment between locations and images for effective worldwide geo-localization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.S.B.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspectives on psychological science 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wason, P.C.; Evans, J.S.B. Dual processes in reasoning? Cognition 1974, 3, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011.

- Reimers, N. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.10084, arXiv:1908.10084 2019.

- Zhai, X.; Mustafa, B.; Kolesnikov, A.; Beyer, L. Sigmoid loss for language image pre-training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 11975–11986.

- Russell, J.A.; Weiss, A.; Mendelsohn, G.A. Affect grid: a single-item scale of pleasure and arousal. Journal of personality and social psychology 1989, 57, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doersch, C.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Sivic, J.; Efros, A.A. What makes paris look like paris? Communications of the ACM 2015, 58, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Sun, L. Mllm-as-a-judge: Assessing multimodal llm-as-a-judge with vision-language benchmark. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- Wallace, B.; Dang, M.; Rafailov, R.; Zhou, L.; Lou, A.; Purushwalkam, S.; Ermon, S.; Xiong, C.; Joty, S.; Naik, N. Diffusion model alignment using direct preference optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 8228–8238.

| 1 |

CreativeML Open RAIL++-M License |

| 2 |

Terms borrowed from the valence and arousal grid of [ 56] |

Figure 1.

Our Generative Facade pipeline has 3 components; (1)segmentation module using SegClip [

45], (2)image generation module using SDXL [

42] and (3) an evaluation module that consists of both human-based and machine-based evaluation

Figure 1.

Our Generative Facade pipeline has 3 components; (1)segmentation module using SegClip [

45], (2)image generation module using SDXL [

42] and (3) an evaluation module that consists of both human-based and machine-based evaluation

Figure 2.

segmentation mask from three different text prompts. From left to right, ’windows and doors’,’windows’,’doors’.

Figure 2.

segmentation mask from three different text prompts. From left to right, ’windows and doors’,’windows’,’doors’.

Figure 3.

Original Amsterdam image (left), a Hong Kong counterfactual with localise inpainting (middle), and an unrealistic counterfactual without inpainting where the canal is covered by concrete (right).

Figure 3.

Original Amsterdam image (left), a Hong Kong counterfactual with localise inpainting (middle), and an unrealistic counterfactual without inpainting where the canal is covered by concrete (right).

Figure 4.

Original San Francisco image (left), a realistic Kyoto counterfactual with targeted architectural inpainting (middle), and an unrealistic counterfactual without inpainting (right).

Figure 4.

Original San Francisco image (left), a realistic Kyoto counterfactual with targeted architectural inpainting (middle), and an unrealistic counterfactual without inpainting (right).

Figure 5.

Original image from Shanghai(left), and two counterfactual images of Paris, Kyoto and Tokyo with different random codes (top and bottom) showing good image diversity.

Figure 5.

Original image from Shanghai(left), and two counterfactual images of Paris, Kyoto and Tokyo with different random codes (top and bottom) showing good image diversity.

Figure 6.

Visualising the counterfactuals with different Guidance and Scale Parameters.

Figure 6.

Visualising the counterfactuals with different Guidance and Scale Parameters.

Figure 7.

An example of the Human Evaluation Self-reported Survey Question.

Figure 7.

An example of the Human Evaluation Self-reported Survey Question.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for geolocalisation of original images

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for geolocalisation of original images

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for geolocalisation of generated images

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for geolocalisation of generated images

Figure 10.

Geolocalisation counterfactuals that is more geographically consistent. Paris - Original (left) London (middle) and Kyoto (right)

Figure 10.

Geolocalisation counterfactuals that is more geographically consistent. Paris - Original (left) London (middle) and Kyoto (right)

Figure 11.

Geolocalisation counterfactuals that is less geographically consistent. Shanghai - Original (left) London (middle) and Kyoto (right)

Figure 11.

Geolocalisation counterfactuals that is less geographically consistent. Shanghai - Original (left) London (middle) and Kyoto (right)

Figure 12.

Perceptual alignment examples shows objective counterfactuals such as "Stone and Glass" on the left are more distinguishable than affective counterfactuals such as "Calm and Stressful" on the right

Figure 12.

Perceptual alignment examples shows objective counterfactuals such as "Stone and Glass" on the left are more distinguishable than affective counterfactuals such as "Calm and Stressful" on the right

Figure 13.

Counterfactual Embeddings show clustering between cities that are near to each other geographically.

Figure 13.

Counterfactual Embeddings show clustering between cities that are near to each other geographically.

Figure 14.

Scatterplot between Human Vs Model Evaluations show there is relative correspondance between human-based and model-based evaluations.

Figure 14.

Scatterplot between Human Vs Model Evaluations show there is relative correspondance between human-based and model-based evaluations.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).