1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Value and Digital Transformation

In established heritage conservation charters and guidelines, the principles of 'authenticity' and 'legibility of interventions' are recognized as fundamental tenets.These principles are of paramount importance and are widely adopted to guide practices in the specialized field of architectural heritage preservation and historic urban regeneration. Consequently, these guiding principles generally discourage the adoption of direct stylistic mimicry or verbatim replication in the repair and retrofitting of historic buildings. Such an approach is typically discouraged to prevent the distortion of historical narratives, the conflation of different historical layers, and any compromise to the integrity of the original fabric [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, in complex real - world scenarios, architectural entities often suffer severe deterioration due to various factors, putting historic urban landscapes at significant risk of extensive degradation. Under these circumstances, an overly rigid adherence to the aforementioned principles may, paradoxically, exacerbate the loss of historic cities and their architectural character if the 'completeness' or 'integrity' of the built heritage cannot be effectively maintained or restored. In these challenging contexts, a controlled and well - informed 'stylistic restoration' or 'emulation' of historic building facades—coupled with the flexible adaptation and reinterpretation of their constituent elements—can emerge as a more proactive and efficacious strategic approach. This is particularly pertinent during the preliminary design phases, where the rapid evaluation of multiple design alternatives is crucial [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This approach transcends mere mechanical reproduction. Instead, it relies on a creative 'typological transcoding' [

10,

11] rooted in a profound understanding of historical architecture and rigorous typological analysis. The primary aim is to perpetuate the stylistic characteristics and genius loci of specific historical periods. This concept is exemplified by Viollet - le - Duc's restoration of Notre - Dame Cathedral. His work demonstrated that, at times, restoration may necessitate a degree of 'idealized' creation. Such creation, based on a thorough comprehension of the original style's essence, seeks to reinstate the building's 'complete state' as perceived for that particular historical era [

12,

13,

14].

The scholarly investigation of 'stylistic emulation' in historic building facades extends far beyond the mere replication of existing structures.This concept broadly encompasses the nuanced and variously focused stylistic reinterpretation of historic facades, predicated upon a thorough comprehension of their architectural typology. Such reinterpretation may involve, inter alia: (i) the extraction of critical facade elements—such as composition, proportion, decorative motifs, and material texture—for application within novel design contexts; (ii) the flexible adaptation and recombination of historical prototypes to meet contemporary functional requirements; and (iii) innovative 're - creation' that respects the core principles of the original style. This broader view of 'stylistic emulation' is particularly relevant during the conceptual and schematic phases of architectural design. It facilitates the rapid generation and comparative analysis of multiple design proposals imbued with specific historical stylistic connotations, thereby enabling more effective design development and refinement. This approach is particularly valuable inprojects seeking to balance historicalcontinuity with modern functional demandsamid rapid urbanization.

Furthermore, the research and application of 'stylistic emulation' for historic architecture offers a value proposition that extends beyond the traditional domains of physical heritage conservation and historic urban area regeneration. The advent and proliferation of digital technologies have significantly broadened its application landscape. For instance, in the digital reconstruction of historical and cultural exhibitions, 'stylistic emulation' techniques facilitate the virtual recreation of lost or severely damaged architectural settings, providing the public immersive historical experiences. Similarly, in the development of virtual engines and game environments, architectural style generation predicated on 'stylistic emulation' enables the efficient construction of virtual worlds imbued with specific historical atmospheres and a high degree of verisimilitude, substantially enriching the content and experiential quality of digital entertainment and virtual tourism [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Consequently, the pursuit of efficient, precise, and interpretable methodologies for 'stylistic emulation' of historic building facades not only holds tangible significance for the stewardship of the tangible built environment but also provides critical technological support for the advancement of emerging fields such as digital humanities and virtual heritage.

1.2. From GANs to Diffusion: Technological Foundations from a Typological Perspective

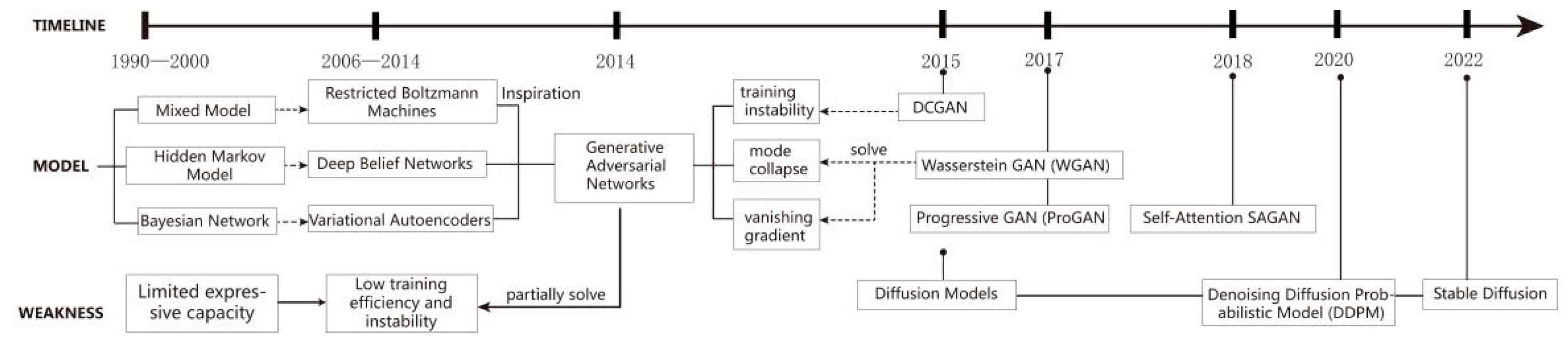

Traditionally, conventional methodologies for emulating architectural facades have predominantly relied on aesthetic intuition and accumulated empirical knowledge. The effectiveness of these processes was often constrained by the cognitive frameworks and technical repertoires of individual architects, lacking robust mechanisms for efficient information processing and feedback. This limitation manifested as insufficient dynamic adaptability and information handling capabilities, potentially resulting in mechanistic and monolithic stylistic reproductions that struggled to achieve fluid and meaningful stylistic innovation. However, with the advent of substantially enhanced computational power ushering in the era of Artificial Intelligence (AI), interdisciplinary research has increasingly integrated AI technologies into architectural practice. This convergence has progressively addressed the inherent shortcomings of traditional workflows, thereby infusing new potentialities into the evolution of architectural research methodologies (See

Figure 1).

The rapid advancements in deep learning technologies, particularly Generative Artificial Intelligence (Generative AI) models such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [

21] and Diffusion Models [

22], have introduced transformative potential within the architectural design domain. Intriguingly, the developmental trajectories and core operational mechanisms of these technologies resonate, to a certain extent, with the fundamental principles of Architectural Typology. This resonance lies in the shared conceptual approach of learning from extensive corpuses of existing built precedents, abstracting underlying principles, and subsequently generating novel forms and spaces that follow specific generative rules and established typological frameworks.

Early generative models, such as those predicated on Boltzmann Machines (RBMs) [

23,

24] and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures [

25], exhibited considerable limitations concerning the quality, resolution, and diversity of generated imagery. The advent of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) marked a significant inflection point in this trajectory. Leveraging a unique adversarial training mechanism involving a generator and a discriminator, GANs demonstrated the capacity to learn and emulate the latent distributions of complex data, thereby facilitating the synthesis of highly photorealistic images. While subsequent advancements, including Wasserstein GANs (WGANs) [

26], BigGANs [

27], DCGANs [

28], ProGANs [

29], and CycleGANs [

30], partially mitigated persistent challenges such as mode collapse and training instability, the direct applicability of GANs to text - to - image generation tasks remains constrained. This is particularly evident in scenarios demanding precise control and nuanced semantic understanding, where their inherent stochasticity and pronounced sensitivity to input conditioning impede their straightforward deployment for the emulation of intricate architectural styles. Bachl and Ferreira (2019) employed GANs to learn architectural features of major cities and subsequently generate images of non - existent buildings. However, their findings revealed that both standard GAN and Conditional GAN (CGAN) struggled to effectively capture and reproduce the complex geometric configurations, diverse stylistic attributes, and fine - grained details characteristic of built environments. Consequently, these frameworks were deemed unsuitable for direct application in such generative tasks [

31].

Diffusion Models emerged alongside the evolution of GANs. These models learn data distributions through an iterative 'noising-denoising' process. This approach has shown superior performance in generating high-quality and diverse imagery. It surpasses GANs in certain generative capabilities [

32]. Later optimizations, including Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) [

33] and Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) [

34], further improved these models. These advancements not only enhanced generation efficiency but also offered more adaptable frameworks for conditional image synthesis. However, conventional Diffusion Models face challenges without explicit semantic guidance. Their outputs can sometimes lack relevance and controllability. This limitation is especially evident when generating images from intricate textual descriptions or specific stylistic directives.

Against this backdrop, the advent of multimodal learning models was pivotal. Particularly, Contrastive Language - Image Pretraining (CLIP) [

35] emerged as a crucial bridge, facilitating a deeper integration between AI generative technologies and typological principles. CLIP models undergo contrastive learning on extensive datasets of image-text pairs. This training enables them to map both images and text into a shared embedding space. As a result, these models can comprehend the semantic correlations between visual and textual information. Such robust semantic alignment capabilities are critical. They allow the models to guide the image generation process with greater precision based on textual prompts. This is essential for tasks requiring the generation of images that conform to specific architectural styles or typological concepts. Furthermore, technologies like ControlNet [

36] have advanced this control. By incorporating supplementary conditional inputs, such as edge maps, pose skeletons, or depth maps, ControlNet significantly enhances the fine - grained manipulation of image layout and structure. This, in turn, reduces the stochasticity inherent in the generation process.

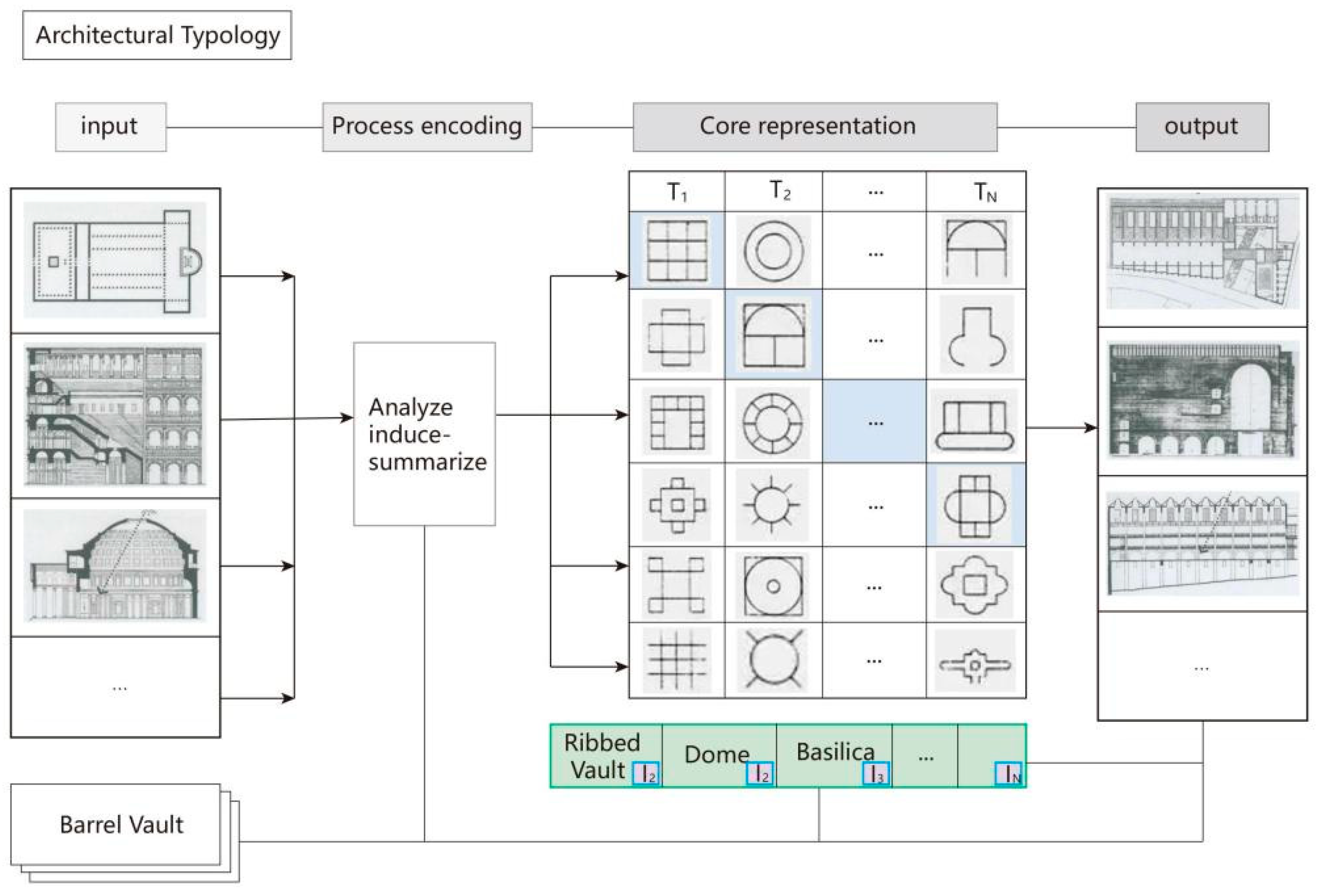

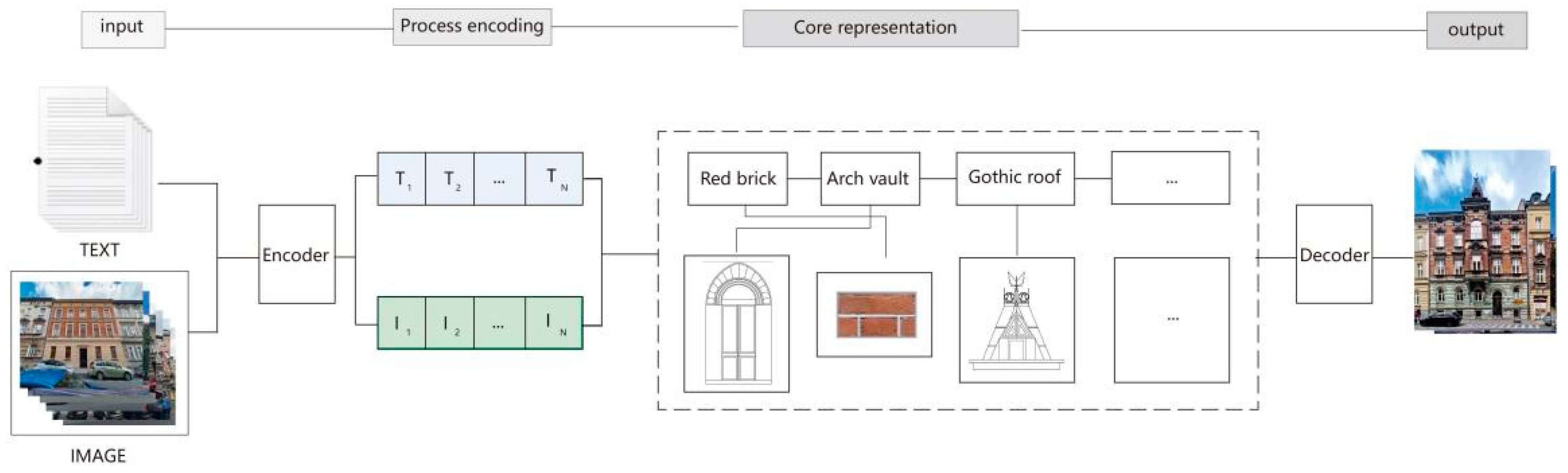

Deep learning's optimization and evolution represents a progressive approximation towards an intrinsic encoding and decoding of visual information (See

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This encompasses adversarial image generation with GANs, diffusion processes in Diffusion Models, and CLIP's semantic matching capabilities. Throughout this developmental trajectory, models incrementally learn to encode latent structural regularities within data. During the generation phase, they effectively reconstruct images that closely emulate the data distribution of real-world examples. This continuous endeavor to approach the essence of an image and discern its inherent generative principles parallels the objectives of architectural typology. Architectural typology strives to abstract immutable 'prototypes' (Types) from extensive collections of built precedents, identifying their core organizational logic and variable constituent elements.

Indeed, a methodological similarity exists between deep learning - based image generation and the study and application of 'Typology' in architecture. Both disciplines aim to unveil the underlying structures and generative mechanisms of objects. Architectural typology, through the systematic analysis of numerous built examples, distills fundamental spatial organizations, functional logics, and formal principles. This process culminates in an understanding of the 'grammar' governing specific architectural types or styles. Analogously, data - driven deep learning models apprehend the 'encoding' of the visual world by learning statistical regularities and structural patterns from images. In the generation phase, both fields leverage these encoded rules for decoding and re-creation. Architects utilize typological knowledge as 'prototypes,' adapting it to specific contexts to generate novel design variations. Similarly, AI models, guided by their learned rules, generate new images from latent representations, demonstrating an innovative aspect akin to typological transcoding.

Although technologies like CLIP and ControlNet now allow models to follow textual prompts and structural guides with far greater fidelity, they also introduce a new challenge: how to adapt these large-scale foundation models efficiently for domain-specific tasks.A key aspect is how to integrate user-defined stylistic preferences or object concepts into these models. Full fine-tuning of large-scale models to learn such specific concepts presents significant challenges. This approach is computationally expensive, demanding substantial GPU resources and considerable time. Moreover, it generates large model files, complicating the storage and dissemination of multiple customized versions. To address these limitations, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technology emerged [

37] providing a solution.LoRA has since been widely adopted to fine-tune large models across various tasks, including image generation. It complements the semantic guidance from CLIP and the structural control offered by ControlNet. Together, these technologies form a critical toolkit within current mainstream text-to-image generation. This toolkit enables highly controllable, high-fidelity, and personalized image generation. Consequently, it has further propelled the application and popularization of AI-Generated Content (AIGC) in fields such as artistic creation and design assistance.

Therefore, the evolution of deep learning models in image generation can be conceptualized as a computational, data-driven 'typological exploration'. Models, through large-scale learning, discover and encode the latent 'typological' regularities and generative rules of the visual world. This discovery process often occurs 'bottom-up,' particularly via contrastive learning techniques like CLIP, which involve continuous matching and training on extensive databases. The introduction of technologies such as LoRA and ControlNet then enhances this automated 'typological system'. These additions enhance its semantic understanding and capacity for external constraints. Consequently, the system can more precisely generate instances 'on-demand' that conform to specific 'types' or 'stylistic variations'.

1.3. Phenomenological Emulation via Deep Learning

As previously discussed, deep learning technologies, particularly GANs and Diffusion Models, have achieved significant advancements in image generation. These technologies have also demonstrated considerable potential for interdisciplinary applications across various architectural research domains. Furthermore, some studies have even encoded architectural constraints as graphical structures. This approach has been applied, for instance, in the study of architectural floor plans, scholars have employed GANs to recognize and generate architectural drawings. These enabled the automated generation of floor plans based on typological norms [

38]; networks learn and store the typological features of floor plans [

39](See

Figure 4). Regarding facade style transfer, the continuous optimization of Diffusion Models has led to their progressive application, alongside GANs, in addressing complex facade design challenges. Researchers have explored various technical approaches for specific tasks. For instance, CycleGAN has been employed for extracting historic urban block architectural styles and integrating them with new designs [

40]. Similarly, CGAN has been utilized for generating facades of rural and small-town buildings [

41]. More recent investigations have yielded positive outcomes. These studies compare the performance of different models, such as GANs versus Diffusion Models, in facade style transfer. They also focus on leveraging technologies like ControlNet and LoRA to enhance image generation accuracy and stylistic control [

42,

43].

This tendency to prioritize form over structure and appearance over substance is a prevalent limitation for many current generative AI applications in architecture. Consequently, even if AI-generated facades are visually captivating and stylistically accurate, considering them as complete architectural proposals can be problematic. Such proposals are likely to exhibit severe deficiencies in terms of intrinsic architectural rationality. This rationality encompasses aspects like the harmonious proportionality of components, the logical coherence of structural systems, and the sequential integrity of spatial narratives. These shortcomings highlight a critical bottleneck in the ongoing evolution of AI technology. Specifically, it underscores the challenge in transitioning from purely 'data-driven' generation to a more profound 'knowledge/principle-driven' paradigm. The core issue lies in an insufficient grasp and adherence to the essential characteristics of the subject matter.

Within this context, architectural typology presents a critical perspective and methodology to address such limitations. Typology's scope extends beyond formal diversity alone. It also prioritizes uncovering the underlying structural cores that inform formal expressions, alongside the organizational paradigms and generative logics tailored to specific requirements. This approach—encompassing the abstraction, analysis, and deduction of ‘Types’—has optimized AI-driven content generation. Consequently, it enhances both the quality and conceptual depth of the resultant outputs [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Therefore, profoundly integrating typological principles into the AI generation pipeline holds paramount importance. This integration is particularly crucial across key stages such as training data construction, model fine-tuning, and output evaluation. Such an approach enables AI models to transcend superficial stylistic mimicry. More significantly, it facilitates their capacity to learn and apply fundamental architectural principles and underlying design logics. Ultimately, this leads to the generation of architectural proposals that are not only stylistically congruent but also rational.

1.4. Research Objectives and Contributions

Informed by the recognized necessity of 'stylistic emulation' for historic architecture, the current trajectory and inherent limitations of AI generative technologies, and the prospective guiding influence of typological theory, this research aims to formulate a methodological framework. This framework aims to integrate architectural typological principles with advanced deep learning models—specifically Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) fine-tuning and Diffusion Models—to facilitate more efficacious and precise emulation, alongside innovative re-creation, of historic building facades. The focus is particularly on architecturally intricate and data-scarce styles, exemplified by Krakow's Eclecticism. The central objective of this research is to advance AI technology beyond mere visual 'phenomenological emulation.' We aim to guide its development towards a more profound 'stylistic transcoding' and 'typological re-creation'. This evolution incorporates the intrinsic logic and principles of architecture. Ultimately, this endeavor seeks to provide technological support of greater practical utility and theoretical depth for historic preservation, urban regeneration, and associated digital cultural heritage domains.

To achieve this objective, this study will focus on addressing the following key research questions:

How can architectural typological principles be systematically integrated into training dataset construction and the LoRA fine-tuning process for AI models, to enhance the accuracy and controllability of stylistic emulation for historic building facades? This encompasses determining how to perform image selection and label optimization informed by typological knowledge, as well as how to devise LoRA fine-tuning strategies to capture the essential characteristics of specific styles.

Compared to standard Diffusion Models or generic fine-tuning approaches, how does this typologically-guided LoRA fine-tuning technique perform in emulating historic architectural styles with data scarcity and stylistic complexity, such as Krakow's Eclecticism? Specifically, what are its performance characteristics in terms of realism, stylistic accuracy, and detail reproduction,as well as what are its discernible advantages and limitations?

Does this methodology enable AI models to learn and reproduce typological features beyond superficial visual resemblance, capturing deeper characteristics like compositional principles, proportional relationships, and the organizational logic of key decorative motifs? How can quantitative metrics (e.g., evaluation benchmarks from computer vision) be effectively combined with qualitative assessments (e.g., subjective evaluations by architectural experts) to thoroughly evaluate the efficacy of this 'deeper-level' stylistic learning?

Addressing the aforementioned research questions, the primary contributions of this paper are multifaceted. At the theoretical level, we explore and elucidate the foundational principles and inherent logic behind integrating architectural typological theory with AI image generation technologies. Particular emphasis is placed on LoRA and Diffusion Models. This investigation offers a novel theoretical perspective for AI-assisted architectural design and the digital preservation of historical heritage. Furthermore, it underscores a paradigm shift from 'phenomenological emulation' towards 'typological transcoding'. Methodologically, this paper proposes and validates a comprehensive workflow. This workflow systematically integrates typological analysis into both the training and application of LoRA models. It encompasses several key components: (i) dataset construction guided by typological principles, including image selection and label optimization; (ii) LoRA model fine-tuning strategies tailored for specific historical styles; and (iii) an evaluation framework for generated outputs that synthesizes quantitative metrics with qualitative assessments. At the practical level, using Krakow's Eclectic building facades as a specific case study, we successfully demonstrated the efficacy of our proposed methodology. This was particularly evident when addressing architecturally complex and data-scarce styles. Our approach not only generated high-quality 'stylistic emulation' images but also provided an open-source LoRA model. This model is specifically trained on a dataset of Krakow's Eclectic facades (available at

https://civitai.com/models/1576307?modelVersionId=1783732). It is intended to facilitate further experimentation and testing by subsequent researchers. Furthermore, we explored the potential application of this methodology in several domains. These include rapid design evaluation in preliminary architectural design, digital reconstruction for historical and cultural exhibitions, and the development of virtual engine and game environments. This exploration offers novel perspectives and opens new possibilities for applying AI technology more broadly within architecture and associated cultural heritage fields.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case-Study Selection: Krakow’s Eclectic Facades

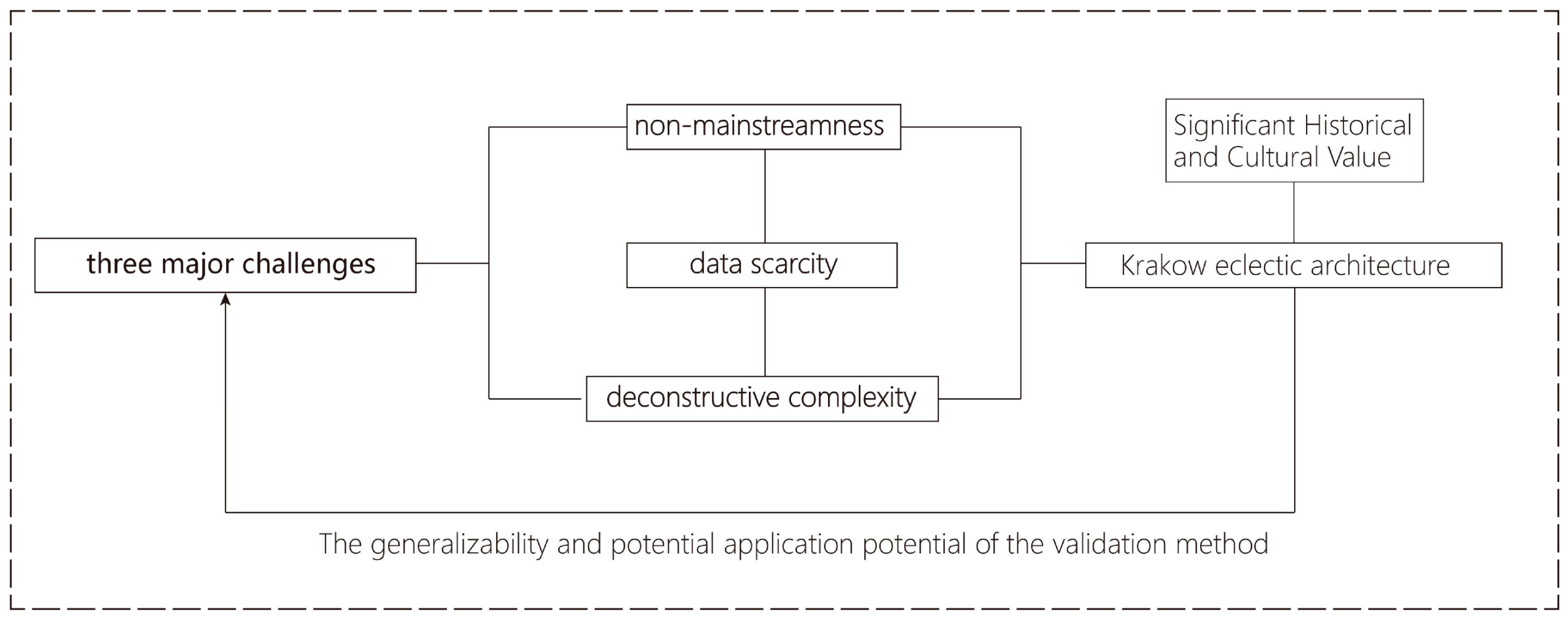

The selection of the research subject for this study involved careful deliberation, culminating in the choice of Eclectic building facades from the Krakow region of Poland (See

Figure 5) as the primary research specimens. This decision was guided by several factors (See

Figure 6), the first of which is the subject's relative non-mainstreamness. Unlike globally prominent and extensively documented architectural styles such as Gothic, Baroque, or Modernism, Krakow's Eclecticism is comparatively underrepresented within global architectural scholarship and computer vision. This is particularly significant in the specific context of stylistic transfer applications. Such a characteristic is advantageous for evaluating our proposed methodology's efficacy with minimal interference from pre-existing, large-scale datasets or established analytical precedents. Furthermore, the profound historical and cultural value of these buildings is self-evident. Serving as crucial symbols for late 19th and early 20th-century urban modernization and cultural renaissance, these buildings embody a rich heritage. Their study, therefore, holds dual significance for both academic research and the preservation of cultural heritage. Finally, selecting this challenging case serves a strategic purpose: to validate the generalizability and potential applicability of our proposed methodology. If this framework can successfully address such a demanding 'hard case,' its broader applicability and robustness will be strongly demonstrated. This would be particularly true when dealing with architectural types characterized by more abundant data or clearer stylistic definitions. Such an outcome would, in turn, augur well for its future prospects in AI-assisted architectural design and related fields.

To ensure the focused nature and representativeness of the research samples, this study further concentrated its investigation on Kraków's Wesoła District. This district served as the specific area for on-site surveys and image acquisition (See

Figure 7). The Wesoła District constitutes a significant component of the buffer zone for the Historic Centre of Krakow, a UNESCO World Heritage site inscribed in 1978. It covers an area of approximately 49.9 hectares. The Wesoła District has remarkably preserved the urban planning fabric of the 19th century. The Wesoła District has remarkably preserved the 19th-century urban planning fabric and retains the evolutionary trajectory of architectural technologies from that era. The area features a high concentration of Eclectic-style residential mansions. Many of these are listed in historical monument registers and inventories of ancient sites. Furthermore, its geographical proximity to the historic Old Town complex of Krakow is notable. Collectively, these factors provide this study with an abundant, concentrated, and high-quality corpus of empirical research material.

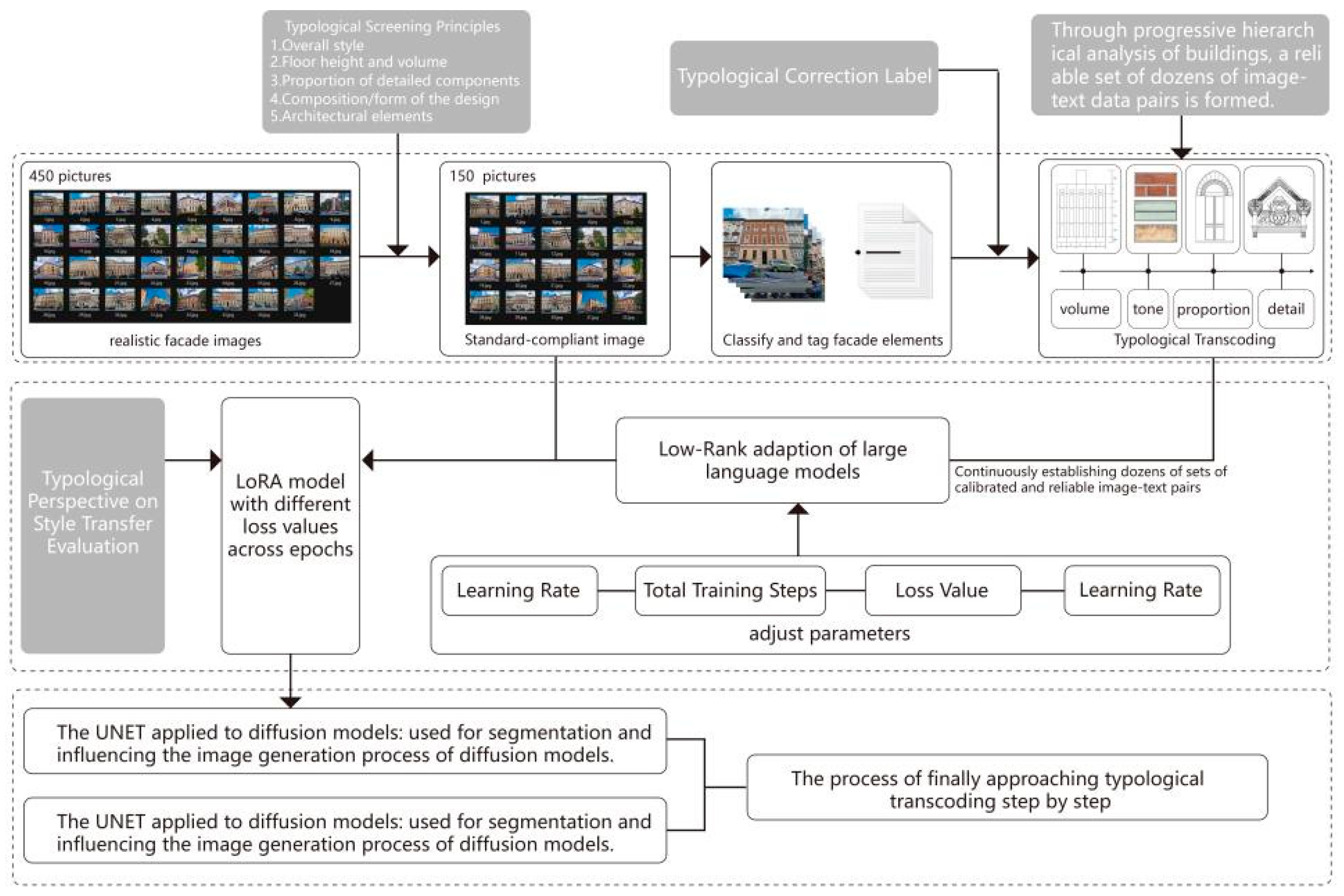

2.2. Image Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

To ensure that the subsequent LoRA model can accurately learn and effectively transfer the core typological features of Krakow's Eclectic building facades, this study adopted a rigorous and meticulous strategy during the image data acquisition and preprocessing phase.

2.2.1. Initial Collection and Screening Criteria for Image Samples

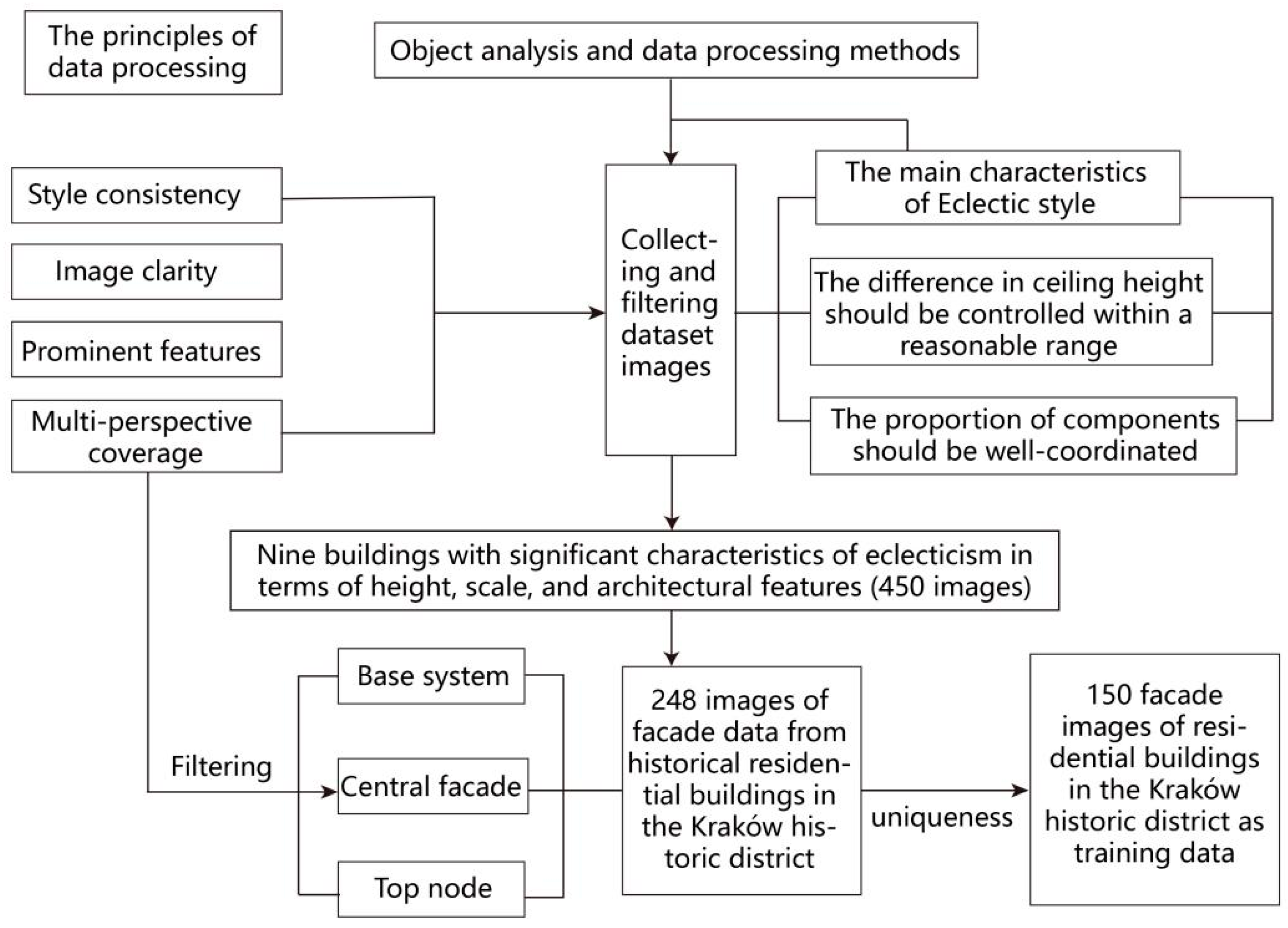

Initially, this research gathered approximately 450 images depicting Eclectic-style residential mansions in the Krakow region. This was achieved through a combination of on-site surveys and multi-source web data collection. However, the quality of these initially collected images was heterogeneous, and their stylistic representations also exhibited noticeable variations. To ensure the quality and representativeness of the dataset for model training, the research team implemented a rigorous screening process. This process incorporated classification and evaluation criteria grounded in typological theory (See

Figure 8). A primary principle of this screening was to ensure style consistency. Priority was given to facade images that clearly and consistently displayed the characteristic features of mainstream Krakow's Eclecticism. This selection aimed to mitigate suboptimal generation outcomes potentially caused by stylistic drift. Concurrently, image clarity was deemed essential. Selected images were required to possess high resolution and optimal illumination. Obscured or blurry images were excluded to ensure the model could acquire clear and complete visual information. Thirdly, the prominence of characteristic features was another critical consideration. Preference was given to images that clearly showcased key typological attributes of the style, such as symmetrical tripartite facade compositions and abundant decorative elements. Finally, achieving multi-perspective coverage was also pursued. We aimed to include diverse viewpoints of the buildings whenever possible. This included standard elevation views and street-level perspectives exhibiting some degree of perspectival distortion, thereby assisting the model in comprehensively learning three-dimensional morphological characteristics.

Following multiple rounds of screening and optimization informed by the aforementioned typological analysis, the research team refined the initial collection of 450 images. This process yielded 248 images that met the preliminary selection criteria. To further enhance the dataset's quality and specificity, the team identified thirty representative buildings from these 248 images. These selected buildings were considered most emblematic of the core typological characteristics—in terms of volume, constituent elements, and structural form—of Eclectic residential mansions in the region. From these thirty edifices, a final selection of 150 high-quality, highly representative images was curated. This curated set formed the foundational dataset for training the LoRA model.

The primary objective of this rigorous data screening and optimization process was to ensure that the model could effectively learn the most essential and archetypal typological features of Krakow's Eclectic building facades. This meticulous preparation not only established a solid data foundation for subsequent AI-driven stylistic emulation. It also provided a reliable repository of stylistic prototypes to inform further innovative design explorations.

2.2.2. Typology-Based Label Generation and Keyword Optimisation

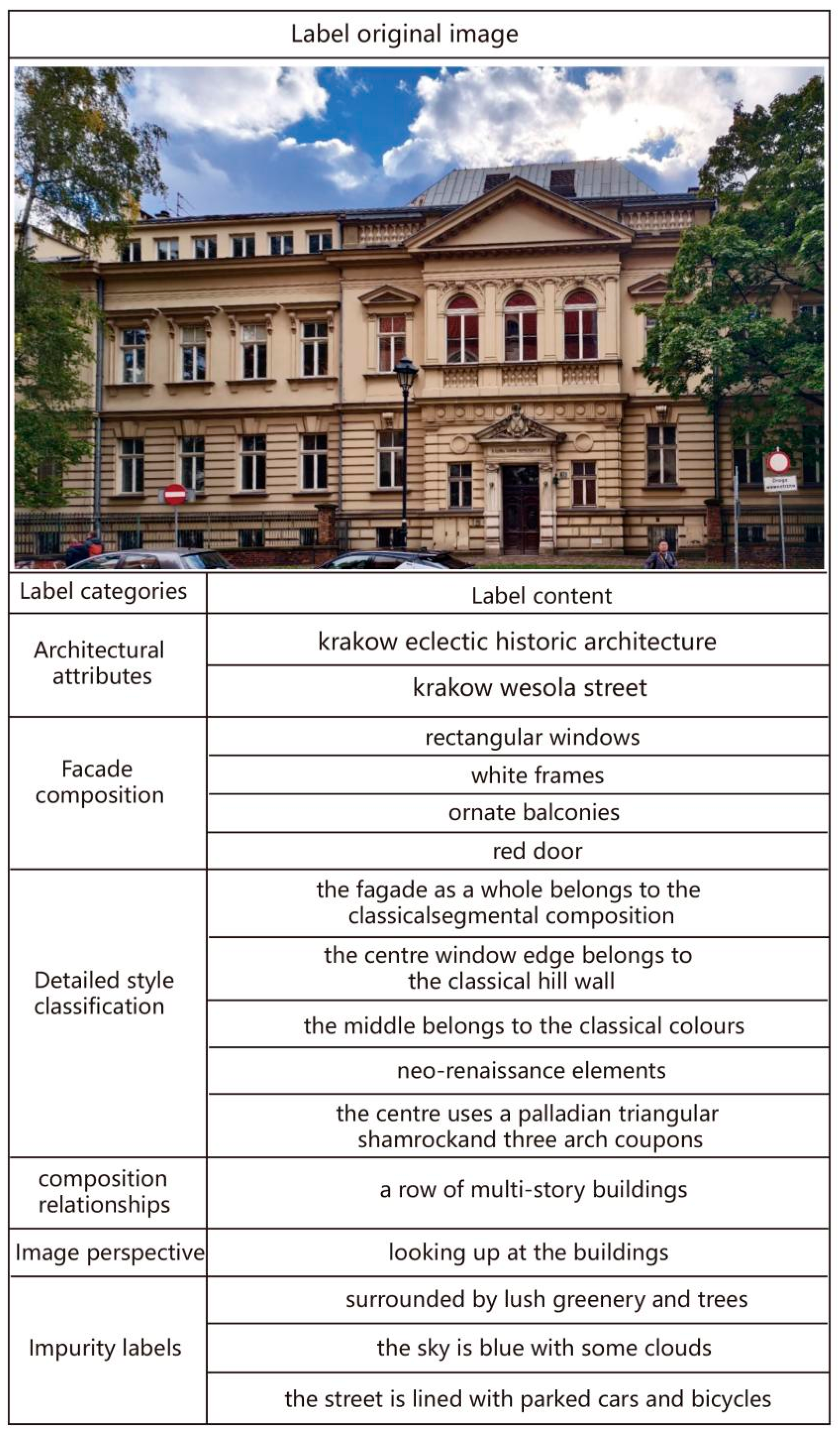

This study employed a hybrid strategy, combining automated annotation with expert correction, to construct a semantic labeling system for architectural facade images intended for LoRA model training. Initially, a pretrained CLIP model was utilized for the preliminary semantic annotation of the image dataset. This process generated descriptive labels encompassing foundational information such as architectural type, stylistic features, and material composition. However, the labels automatically generated by the CLIP model were often quite broad. They frequently lacked precise descriptions of the detailed features characteristic of architectural facades.For example, during the initial annotation of Krakow's Eclectic building facades, the CLIP model predominantly generated generic labels. These included terms such as 'building,' 'facade,' and 'architecture.' However, it struggled to accurately capture more specialized and fine-grained descriptions. Such descriptions are crucial for reflecting the specific typological affiliations and hybridized stylistic characteristics of these facades. Examples of these missed details include 'Neoclassical tripartite composition,' 'Gothic Revival pointed-arch windows,' and 'Baroque broken pediments.'

To address this limitation inherent in automated annotation, this study engaged a team of architectural experts. Their role was to manually correct and supplement the initial labels generated by the CLIP model. The core of this correction process involved the systematic review and refinement of labels, guided by the intellectual framework of architectural typology.Drawing upon their expertise in architectural typology, the expert team meticulously revised, refined, and augmented the label content. This ensured that the labels accurately reflected the unique characteristics of the building facades shown in the images. During this process, the experts not only rectified erroneous or ambiguous labels generated by the CLIP model but also supplemented these with a substantial number of missing architectural terminologies. Examples include terms such as 'sandstone plinth', 'Corinthian order', and 'molding'. This comprehensive revision significantly enhanced the accuracy and professional relevance of the labels, as illustrated in

Figure 9 (See

Figure 9).

During the optimization of the keyword dataset, particular emphasis was placed on the hierarchical analysis of architectural facade images. This hierarchical analytical approach is based on fundamental principles of architectural typology. It conceptualizes the building facade as an organic entity composed of multiple constituent levels. Progressing from macroscopic to microscopic scales, this analysis sequentially addresses aspects such as overall architectural type, stylistic composition, color and material palettes, compositional forms, and detailed elements. Specifically, the label classification system developed in this study primarily encompasses the following tiers:

Architectural Attributes-Label categories: e.g., historical residences, public buildings;

Facade Composition: e.g., Krakow eclectic architecture (predominantly neo-renaissance style), ornate balconies, Baroque-style window decoration ;

Material Attributes: e.g., red brick, beige stone, white window frames;

Facade Composition: e.g., symmetrical composition, classical segmental composition, a row of multi-story buildings;

Detailed Style Classification: e.g., orders (column types), cornices, pediments, moldings, spandrels (pier/window infill), corbels.

Image Perspective: e.g., front elevation, low-angle view (looking up at the buildings).

Impurity Labels : e.g., the sky is blue with some clouds, the street is lined with parked cars and bicycles.

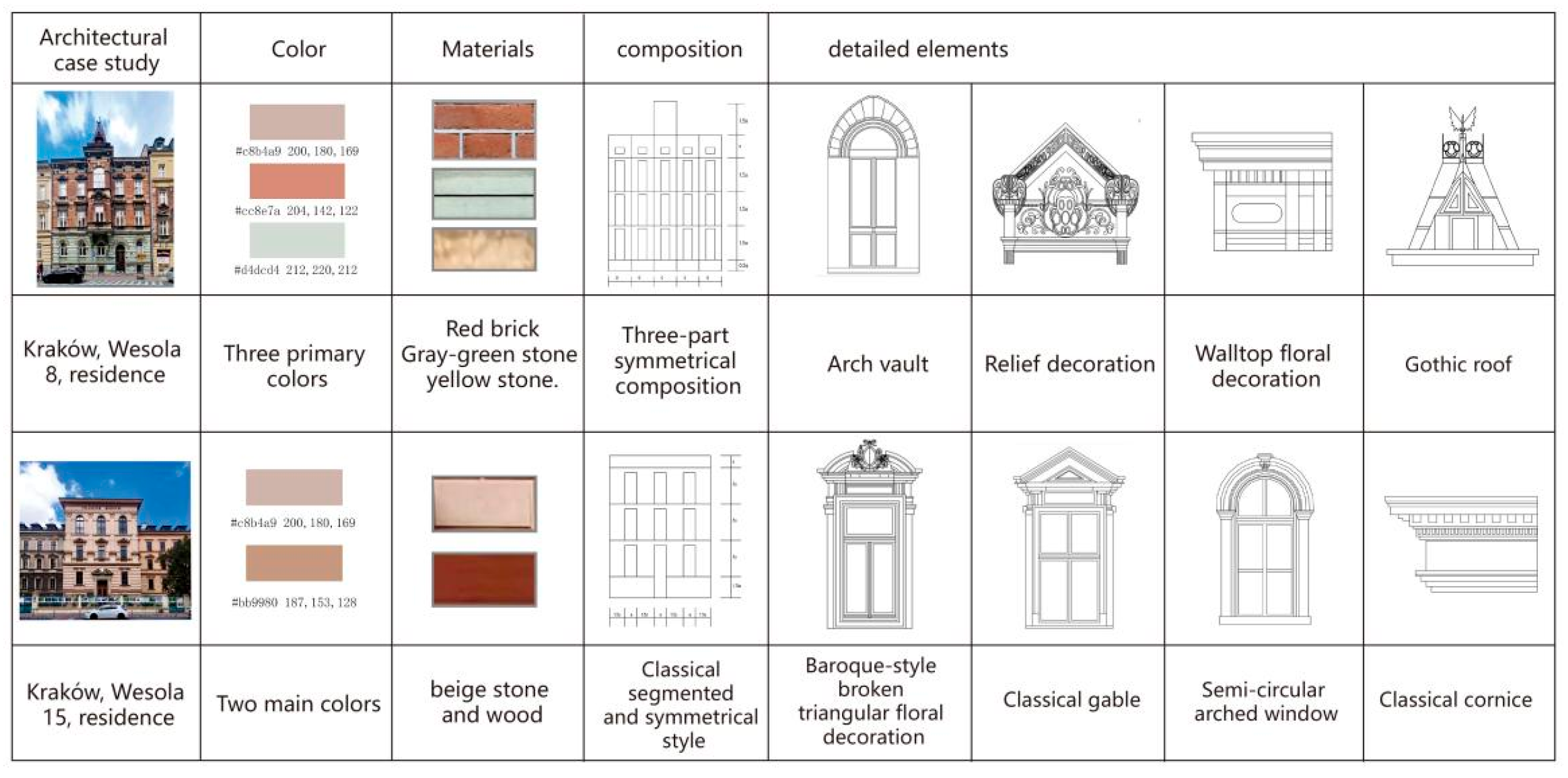

The application of hierarchical analysis is clearly illustrated by examining the facades of two residential mansions: Wesoła No. 8 and Wesoła No. 15 (See

Figure 10). Both edifices employ a tripartite compositional structure, a common feature in Classical architecture. This structure divides the facade into three distinct sections: the base, the main body, and the entablature (or cornice/eaves section). Regarding the compositional elements of the main body, both buildings exhibit a clear inter-story correspondence. Specifically, windows are vertically aligned across stories, often with identical dimensions. Fenestration patterns become progressively more intricate from the ground-floor openings to the attic, while decorative mouldings also grow correspondingly elaborate [

44]. However, while both edifices share commonalities in overall composition, gable ornamentation, and facade coloration that align with Classical styles, they also exhibit a fusion of disparate stylistic influences in their localized details. For instance, the central roof section of Wesoła No. 8 displays distinct Gothic stylistic characteristics. In contrast, Wesoła No. 15 features a ground-floor entrance lintel incorporating Baroque-style broken triangular and segmental pediments. This hierarchical analytical approach is instrumental in enabling the model to achieve a more profound comprehension of the facade's constituent elements and stylistic attributes. Consequently, this enhances both the accuracy and stylistic consistency of the generated images. Through iterative cycles of automated annotation, manual expert correction, and dataset optimization, this study curated 150 high-quality image-label pairs. These pairs formed the foundational data for the subsequent LoRA model training.

This hierarchically clear and comprehensively detailed labeling system is designed with a primary aim: to furnish AI models with richer and more structured learning information. The intention is to enable these models to transcend rudimentary pixel-level mimicry. Ultimately, this facilitates a more profound understanding and faithful reproduction of the stylistic essence inherent in historic architecture.

2.3. Typological Transcoding Framework

To achieve precise 'stylistic emulation' and innovative re-creation of Krakow's Eclectic building facades, this study formulated a typological transcoding framework. This framework integrates Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) fine-tuning techniques with a Stable Diffusion Model. The central principle of this framework is the application of typological analysis to guide both the training and inference processes of the AI model. The aim is to enable the model not merely to mimic visual phenomenology but also to comprehend and reproduce the underlying logic and compositional principles inherent in the architectural style.

2.3.1. Brief Introduction to Diffusion Models and LoRA Technology

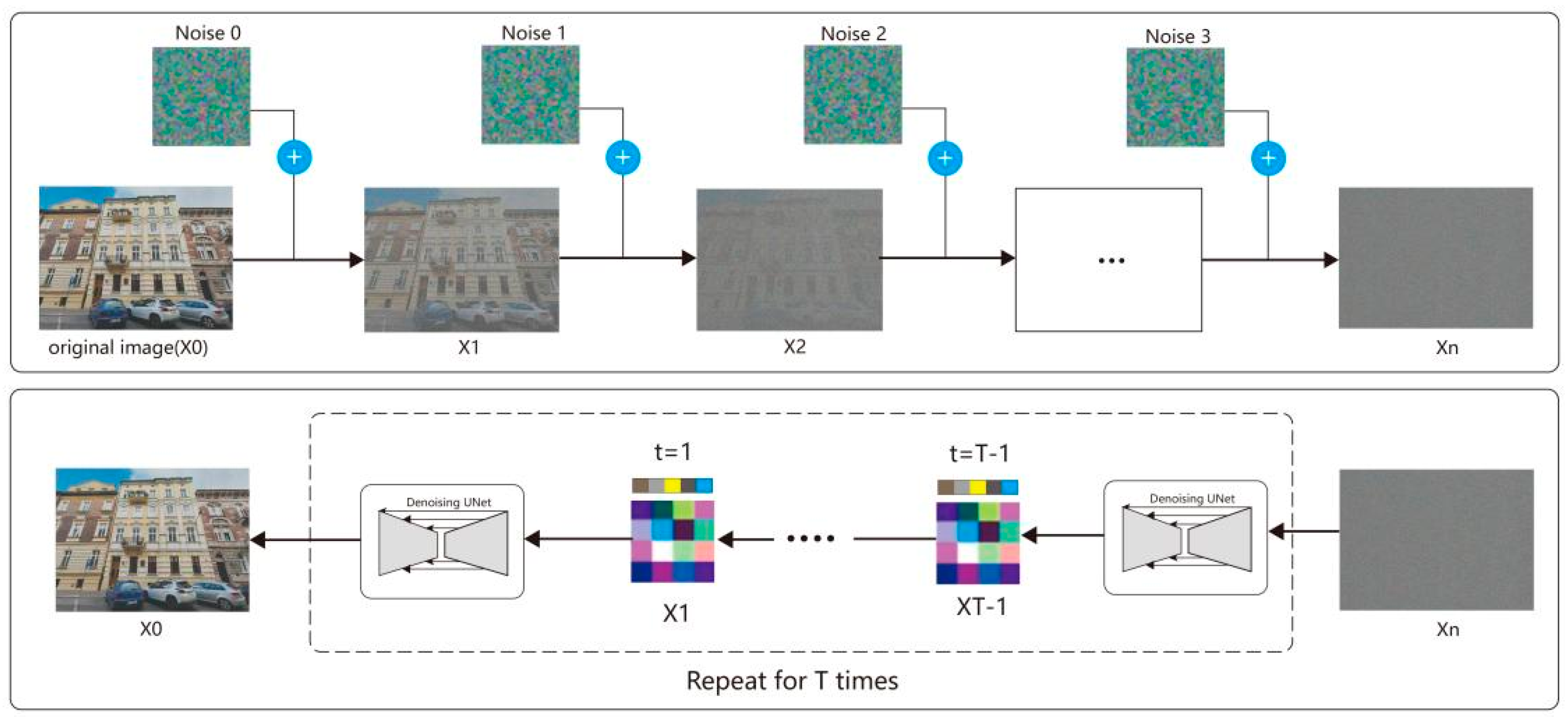

Diffusion Models

Diffusion Models represent a potent class of deep generative models. Their operational principle can be summarized as a bidirectional process. The initial phase is the 'forward diffusion process.' This involves the incremental addition of Gaussian noise to the original data (See

Figure 11) until it fully transforms into pure noise. Subsequently, the crucial 'reverse denoising process' takes place. In this phase, the model learns to progressively remove noise, starting from pure noise, to ultimately reconstruct a clear new sample that aligns with the original data distribution [

22,

33,

34]; Separately, the Stable Diffusion Model, an advanced iteration of diffusion models, operates by performing diffusion and denoising processes within a latent space. This operation is coupled with textual conditional guidance, often facilitated by models like CLIP [

35]. Consequently, Stable Diffusion achieves exceptional performance in text-to-image generation tasks. It is capable of producing high-resolution, highly detailed, and semantically pertinent images. Its robust generative capabilities and responsiveness to textual prompts make it an ideal foundational model for the stylistic transfer tasks investigated in this study.

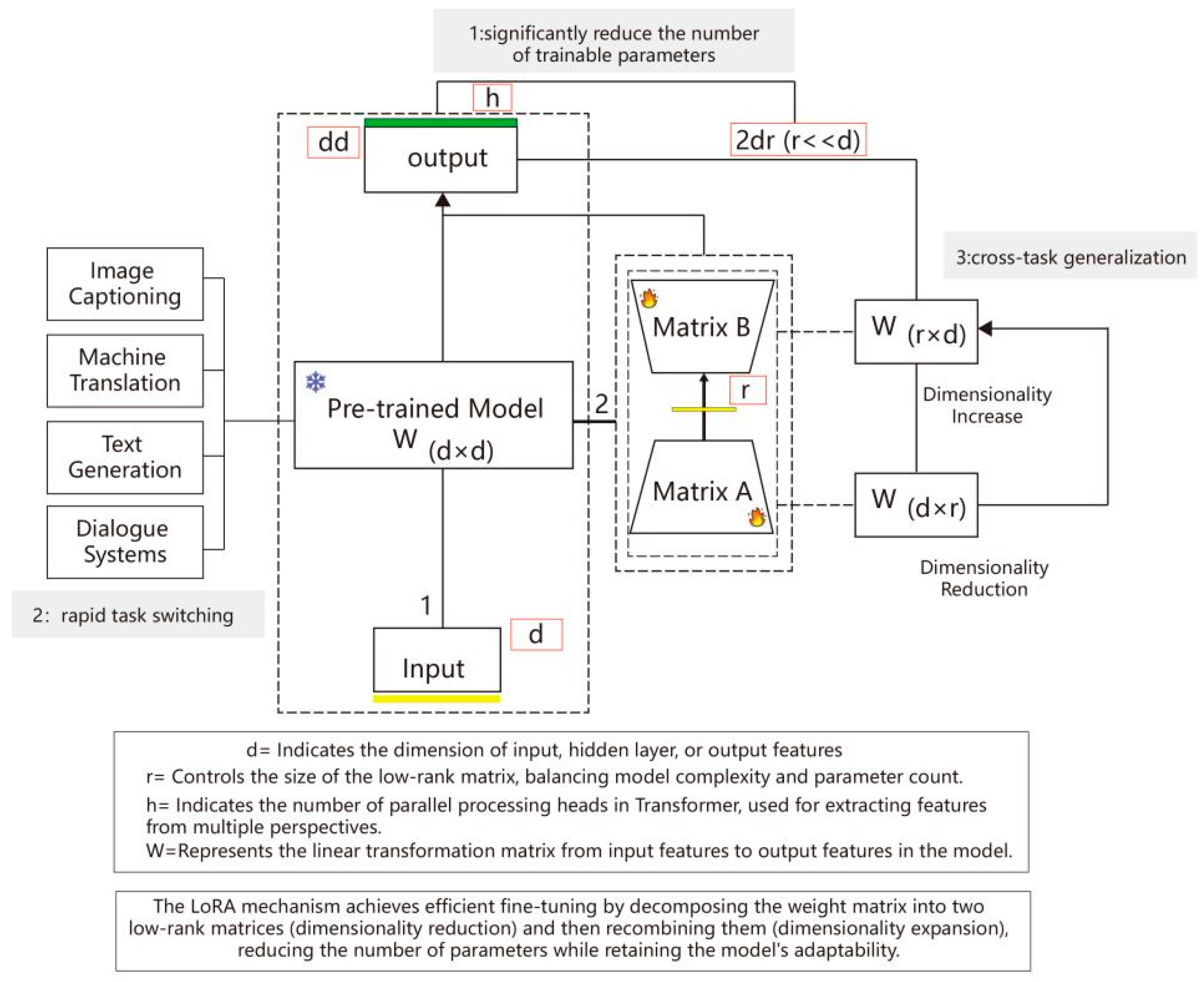

Low-Rank Adaptation

Although pretrained large-scale diffusion models, such as Stable Diffusion, possess robust general-purpose generative capabilities, their direct application to specific, nuanced styles often falls short. For instance, when applied to styles like Krakow's Eclectic architecture, achieving desired levels of precision and stylistic consistency can be challenging. Furthermore, full fine-tuning of these entire large models is computationally prohibitive. It also carries a significant risk of overfitting, particularly when training data is scarce. LoRA technology [

37] offers an efficient solution to these challenges. Its core principle involves injecting trainable, low-rank matrices alongside key layers of a pretrained model. These key layers include the weight matrices within attention mechanisms (See

Figure 12). During fine-tuning process, only the parameters of these low-rank matrices are updated. The main weights of the pretrained model remain frozen.

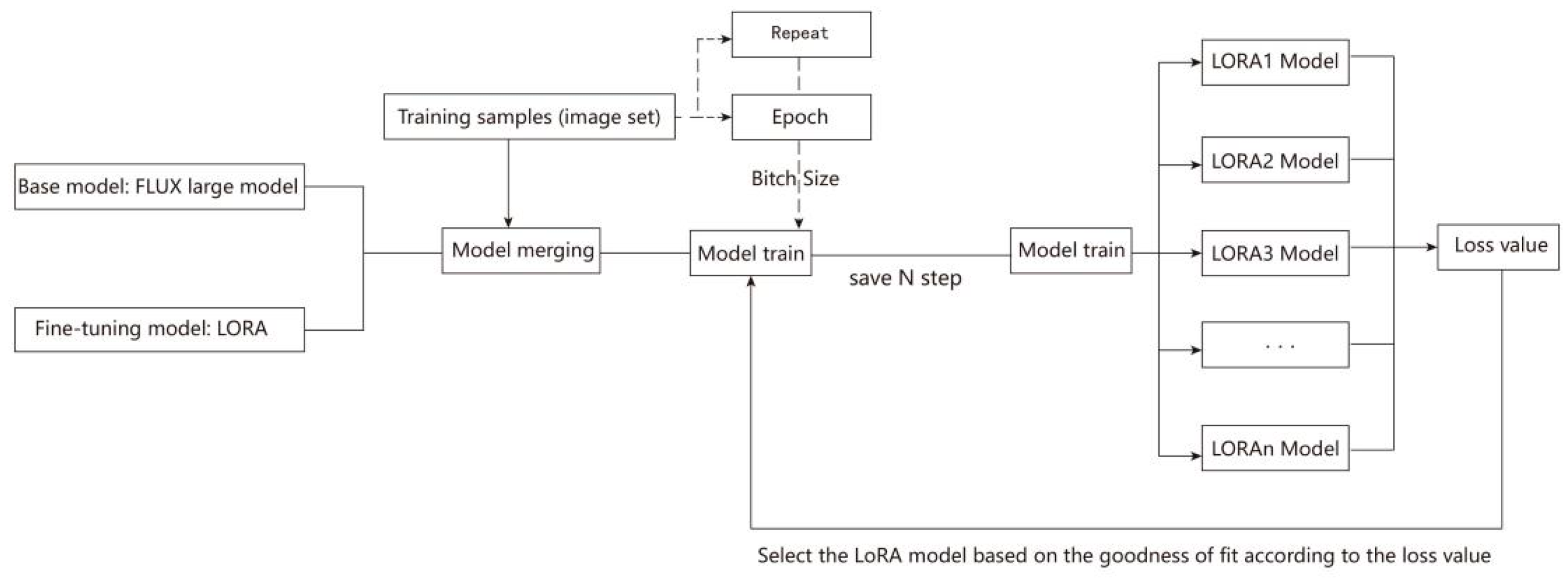

2.3.2. LoRA Model Training Workflow and Key Parameter Regulation

The training workflow for the LoRA model, specifically tailored for Krakow's Eclectic architectural style in this study, is illustrated in

Figure 13 (See

Figure 13). This workflow leverages the previously optimized image-label dataset. It employs a Stable Diffusion model—with FLUX selected as the foundational model architecture in this research—as its pretrained base.

During the training process, the meticulous adjustment of the following key hyperparameters is crucial for ensuring that the model effectively learns and generates high-quality, stylistically consistent facade images:

Learning Rate: This hyperparameter directly dictates the step size for model weight updates during training. While an excessively high learning rate can destabilize training or cause divergence, an overly low rate significantly prolongs training and risks entrapment in local optima. Consistent with common LoRA fine-tuning practices and prioritizing model stability, this study explored and set learning rates within a relatively narrow range (e.g., 1e-4 to 1e-5). This strategy aimed to effectively capture the nuanced characteristics of the target style while ensuring stable convergence [

45].

Total Training Steps: This parameter depends on the image count, total training epochs, repetitions per image, and batch size. It directly correlates with the depth of the model's learning from the training data. When training on complex styles such as Krakow's Eclecticism, achieving a balance between underfitting and overfitting is paramount [

46,

47,

48]. Underfitting occurs when the model fails to adequately learn stylistic elements, whereas overfitting involves excessive memorization of training sample details, thereby impairing generalization capabilities. Insufficient training steps can result in generated facades lacking typical stylistic details. Conversely, An excessive number of steps may lead the model to merely reproduce specific buildings from the training set, limiting its flexible application in novel design contexts. Therefore, a critical aspect of parameter tuning in this study involves judiciously planning the total training steps. This is coupled with the subsequent selection of optimal model checkpoints based on rigorous evaluation.

Loss Value Monitoring: The loss value is a metric quantifying the discrepancy between the model's predictions and the ground truth data. It directly reflects the model's training efficacy. During training, a diminishing loss value typically indicates that the model's predictions are aligning more closely with actual observations. Consequently, the monitoring and optimization of the loss value are linked to the model's learning efficiency and the quality of the generated images. For architectural style generation tasks, particularly in rendering the detailed nuances of Krakow's Eclecticism, optimizing the loss value is crucial. This ensures that the model capture the fine-grained characteristics of the architectural style, facilitating the generation of more realistic and precise design imagery.

Systematic adjustment and experimentation with the aforementioned key parameters aimed to identify the optimal training configuration (

Table 1). This configuration was sought to enable the LoRA model to efficiently and accurately learn the stylistic characteristics of Krakow's Eclectic architecture. For this study, LoRA model fine-tuning was performed on the previously described dataset of 150 image-label pairs. The FLUX architecture was used as the foundational model for this training, which was executed on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24GB of VRAM. Key training hyperparameters were configured as follows: Epochs = 20, Batch Size = 4, and Learning Rate = 1e-4. The entire training process spanned 17 hours, yielding 20 LoRA models, each with a file size of 584 MB.

2.3.3. The Guiding Role of Typological Theory in Training and Inference Processes

Relying solely on the intrinsic learning capabilities of AI models and the adjustment of the aforementioned technical parameters may still prove insufficient to fully overcome the limitations of 'phenomenological emulation'. Therefore, this study underscores the critical importance of integrating architectural typological thought as a consistent guiding force. This integration is emphasized throughout the entire training and inference pipeline of the LoRA model.

During the training data preparation phase, as detailed in

Section 2.2, typological principles guided both image selection and label construction. Image selection aimed to ensure stylistic consistency and feature typicality. Label construction focused on hierarchical and structured organization, identifying aspects such as architectural type, stylistic composition, compositional forms, and key elements. This structured approach provided the model with learning material richer in both structural and semantic information. Upon entering the LoRA model fine-tuning phase, although LoRA predominantly learns visual features, high-quality, typologically-informed labels can indirectly steer the model. These labels guide its attention towards visual patterns associated with specific typological concepts. For instance, by emphasizing labels such as 'tripartite composition,' the model may, during its learning process, focus more on the vertical organizational principles of the facade.

During the inference (image generation) phase, users can guide the model's generation trajectory through meticulously designed textual prompts. These prompts are deliberately imbued with typological concepts. Finally, in the result evaluation and iteration phase, subjective assessments by architectural experts are critical, complementing quantitative metrics from computer vision. These experts evaluate the generated outputs from a typological perspective, rather than focusing solely on superficial visual resemblance. They assess whether the results conform to the intrinsic logic, compositional principles, and cultural connotations (or significations) of the specific (or target) style, rather than relying solely on visual similarity. This feedback, grounded in typological knowledge, can inform the iterative refinement of the model or adjustments to the prompts.

In this manner, the present study endeavors to construct a framework that deeply integrates AI generation with typological theory (See

Figure 14). The overarching aim is to enable AI not merely to 'render accurately' but, more crucially, to 'think correctly' in an architectural sense. Consequently, this approach seeks to achieve a higher echelon of intelligence and creativity in both the 'stylistic emulation' and re-creation of historic architectural styles.

3. Results and Analysis

This chapter present and analyze in detail the experimental results obtained through the methodological framework proposed in this study. Initially, we investigate how key parameters of the LoRA model—specifically the loss value (LOSS) and application weights—influence the generation outcomes for Krakow's Eclectic building facade styles. Subsequently, a comparative analysis, both quantitative and qualitative, is conducted. This analysis evaluates the performance of the proposed typologically-guided and LoRA-fine-tuned AI model against several baseline models. These baselines include standard Stable Diffusion 3.5 and an unfine-tuned FLUX model, specifically within the context of stylistic emulation tasks.

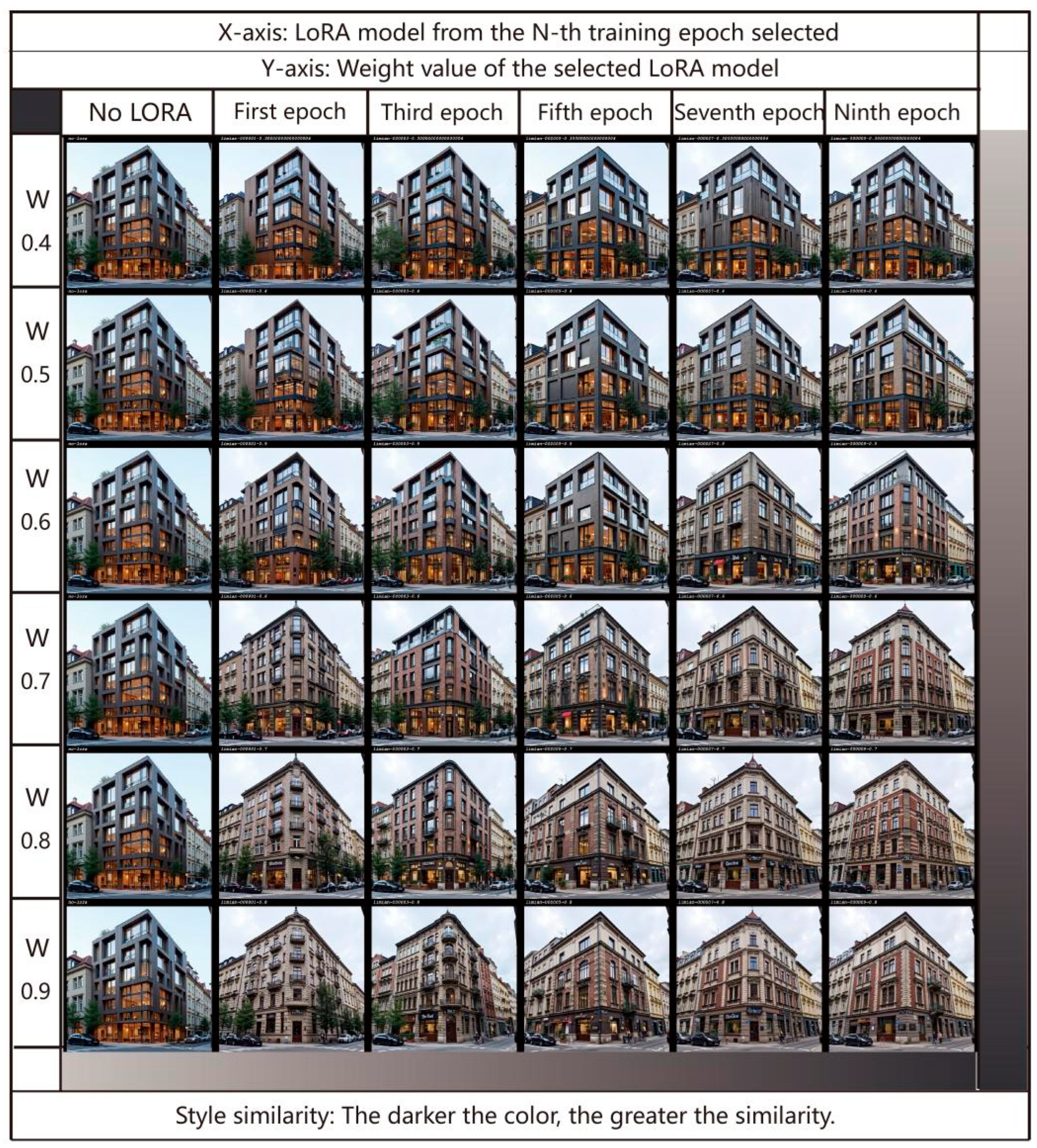

3.1. Influence of LoRA Model Parameters on Stylistic Generation Outcomes

Throughout the training and application phases of LoRA models, two pivotal parameters emerge: the loss value during the training stage and the LoRA weight applied during the inference stage. These parameters collectively exert a significant influence on both the accuracy and diversity of the stylistic attributes in the generated images.

LoRA Loss and Weight Tuning for Style Transfer

Training a LoRA model is fundamentally a learning endeavor wherein the model's proficiency in capturing a target historical style—Krakow's Eclecticism in this instance—typically enhances with an increasing number of training epochs. This enhancement is generally paralleled by a steady decline in the training loss value (LOSS), with lower LOSS values indicating a better fit of the model to the training data. Simultaneously, during inference for image generation, the applied LoRA weight (typically ranging from 0 to 1, though occasionally extending slightly beyond 1) dictates the degree to which the fine-tuned stylistic features influence the base model's output.

By experimenting with LoRA model checkpoints saved at various training epochs (corresponding to different LOSS values), in conjunction with diverse inference weight values, this study observed several discernible patterns (See

Figure 15); see also Figure A1 in Appendix A). During earlier training stages, characterized by higher LOSS values, or when lower LoRA application weights were employed, the resultant images exhibited greater 'creativity' and 'conceptuality.' The AI-generated facade styles tended to manifest as a fusion. This fusion typically involved the target historical style blended with either the inherent style of the base model or broader contemporary design elements. This characteristic offers designers a valuable opportunity for exploring stylistic fusion and seeking innovative expressions during the initial conceptual design phases. Conversely, in later training stages—marked by a significant decrease and convergence of the LOSS value—or when higher LoRA application weights are utilized, the AI-generated image outcomes demonstrate a more precise and stable replication of the target historical style. In such cases, these outputs exhibit a superior resemblance to authentic historical images from the training set, particularly concerning overall composition, decorative detailing, material rendering, and lighting effects. This latter approach is, therefore, more congruous with application scenarios that prioritize high-fidelity reproduction.

This dual control mechanism, comprising the LOSS value (indicative of training depth) and the LoRA weight (reflecting the intensity of fine-tuning influence), affords designers considerable flexibility and control throughout the stylistic emulation process. Designers can select and combine LoRA models from different training stages, along with their respective application weights, tailored to the evolving requirements of a project. This adaptability accommodates needs ranging from early-stage conceptual explorations of stylistic fusion to later-phase pursuits of high-precision stylistic expression. Consequently, AI tools can more effectively address diverse needs for both stylistic imitation and innovation within the design workflow.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge a core deficiency in this approach, which relies purely on understanding and applying technical parameters like LOSS values and LoRA weights. This deficiency lies in its primary effect being confined to the visual phenomenological level of the image. While reducing LOSS value and an increase in LoRA weight enhance the similarity of generated images to the training data—particularly concerning texture, color, lighting, and recognizable stylistic elements (e.g., specific column orders, window ornamentation)—this often occurs at a superficial level. Essentially, the model learns a visual pattern-matching mechanism, aiming for a 'looks like' resemblance. However, this does not guarantee that the model comprehends the underlying architectural principles. These include the structural logic, spatial organization paradigms, or specific construction techniques embedded within these visual elements. Consequently, even if the generated images exhibit high stylistic fidelity to the training data, they may still contain conspicuous fallacies concerning intrinsic architectural rationality. Such fallacies could manifest as, for instance, disproportionate component scaling, illogical structural relationships, or incoherent spatial circulation.Under such circumstances, AI-generated images might merely represent a rigid transplantation of 'stylistic phenomenology,' rather than constituting an architectural expression endowed with intrinsic coherence and buildability. This precisely underscores the inherent limitations of relying solely on AI's visual mimetic capabilities. It also highlights the imperative to integrate more profound architectural knowledge—such as typological principles—for both guidance and evaluation.

3.2. Comparison of Generated Facade Styles

To comprehensively and objectively evaluate the performance of our proposed typologically-guided LoRA fine-tuning methodology—specifically for stylistic transfer for Krakow's Eclectic building facades—we adopted a dual evaluation framework. This framework comprises two main components: (1) objective data analysis using established quantitative evaluation metrics in the field of computer vision, and (2) subjective qualitative assessment of the model-generated images by a panel of architectural experts. This combined approach aims to holistically validate the model's efficacy from both data-centric and expert-informed perspectives.

3.2.1. Quantitative Metrics

For quantitative evaluation, we selected three widely adopted objective metrics from the image generation domain. The first of these is the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID). FID assesses the similarity between the distributions of features extracted by an Inception network from both generated and real images. It measure the realism and diversity of the generated images. Notably, a lower FID value signifies higher quality in the generated imagery [

49]. Secondly, Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) was utilized. LPIPS employs deep learning models to quantify the perceptual similarity between two images. Its outcomes align more closely with human subjective judgments of image similarity. A lower LPIPS value indicates greater perceptual resemblance between images [

50]. Finally, Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) was included. PSNR is a widely used metric for assessing image distortion or the quality of image reconstruction. A higher PSNR value signifies less distortion and, consequently, better image quality [

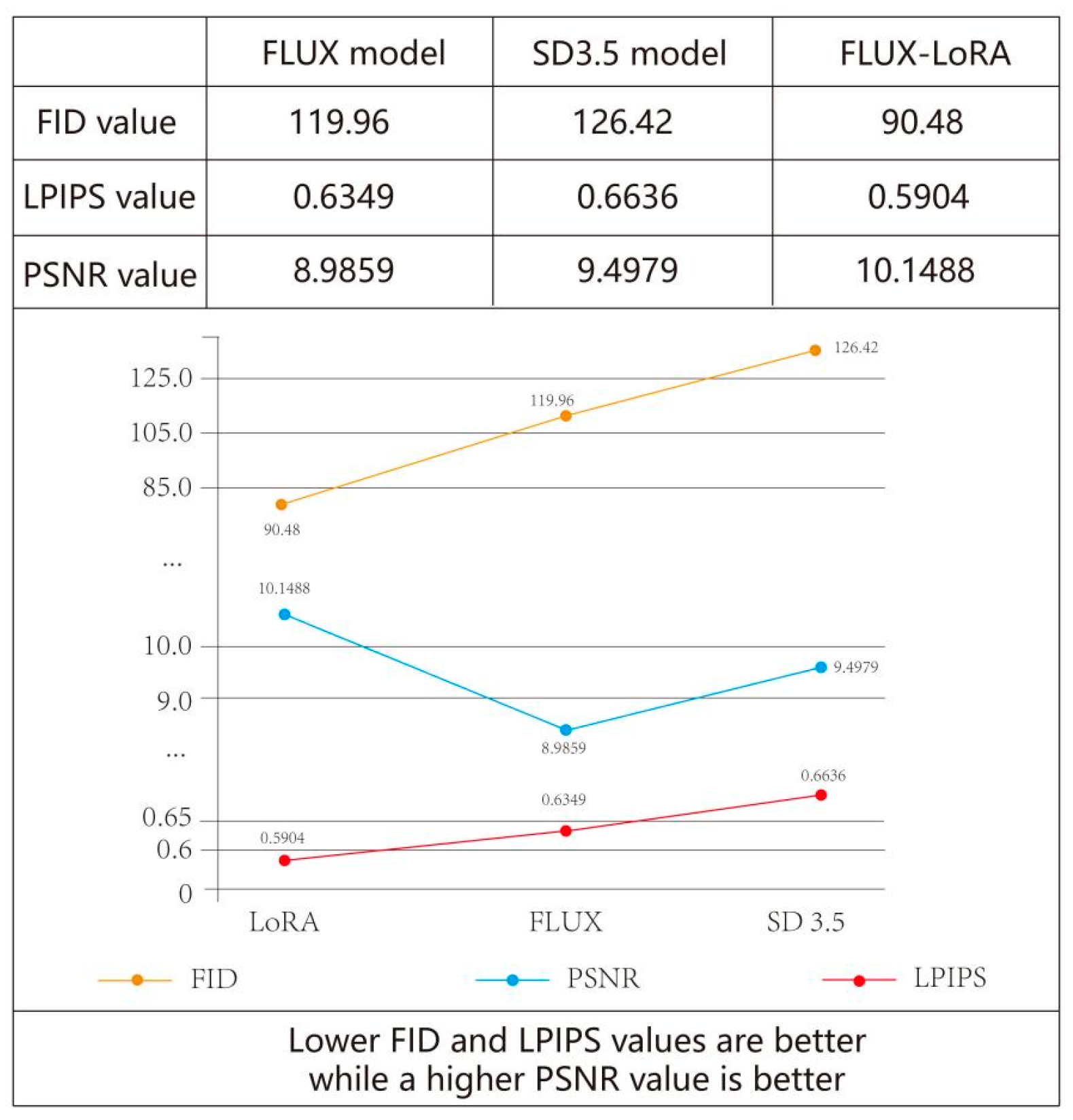

51]. We conducted a comparative analysis between our proposed model—typologically-guided and LoRA-fine-tuned (hereafter referred to as FLUX-LoRA)—and two baseline models. These baselines were: (a) a standard Stable Diffusion model without any fine-tuning (represented by SD3.5 in this study), and (b) the base FLUX large model utilized without LoRA fine-tuning (hereafter FLUX). All models generated images on an identical test set. Subsequently, the three aforementioned quantitative metrics were computed for these generated images.

The comparative results for all metrics, as depicted in

Figure 16 and 17, unequivocally demonstrate that the FLUX-LoRA model (See

Figure 16) (See

Figure 17), fine-tuned using the methodology proposed herein, exhibits a significant advantage across all selected quantitative indicators:

FID Improvement (Lower is Better): The FLUX-LoRA model achieved an FID value of 90.48. This represents an approximate improvement of 28.4% over the SD3.5 model's score of 126.42, and a 24.6% improvement over the base FLUX model's score of 119.96. These results indicate that the image set generated by FLUX-LoRA exhibits an overall feature distribution more closely aligned with that of authentic Krakow Eclectic building facades. Consequently, the generated images are more realistic and diverse.

LPIPS Improvement (Lower is Better): The FLUX-LoRA model attained an LPIPS value of 0.5904. This signifies an approximate improvement of 11.0% over the SD3.5 model's score of 0.6636, and a 7.0% improvement compared to the base FLUX model's score of 0.6349. These findings suggest that images generated by FLUX-LoRA exhibit greater similarity to real images at the human perceptual level. This implies a higher fidelity in reproducing both fine details and overall stylistic characteristics.

PSNR Improvement (Higher is Better): The FLUX-LoRA model registered a PSNR value of 10.1488 dB. This marks an approximate increase of 6.8% compared to the SD3.5 model's score of 9.4979 dB. Notably, the PSNR value for the base FLUX model (8.9859 dB) decreased in comparison. This observation further corroborates the superiority of the FLUX-LoRA model in terms of pixel-level image fidelity and the reproduction of stylistic details.

Collectively, the quantitative computer vision metrics unequivocally indicate that the methodology proposed herein—which integrates typology-guided dataset construction with LoRA fine-tuning strategies—significantly enhances the generated facade imagery. This enhancement is evident across authenticity, perceptual quality, and stylistic similarity.

3.2.2. Qualitative Evaluation by Expert Panel

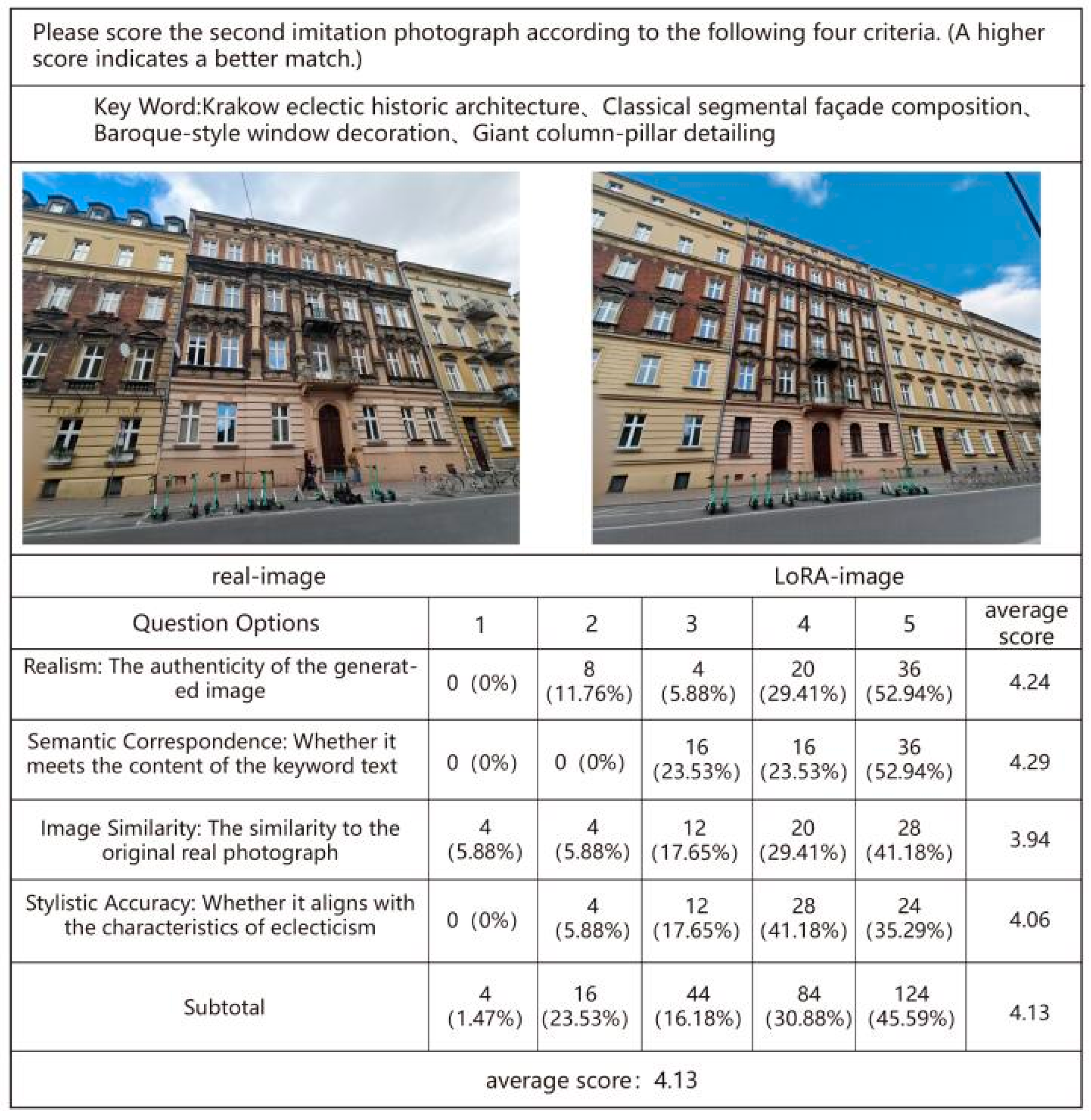

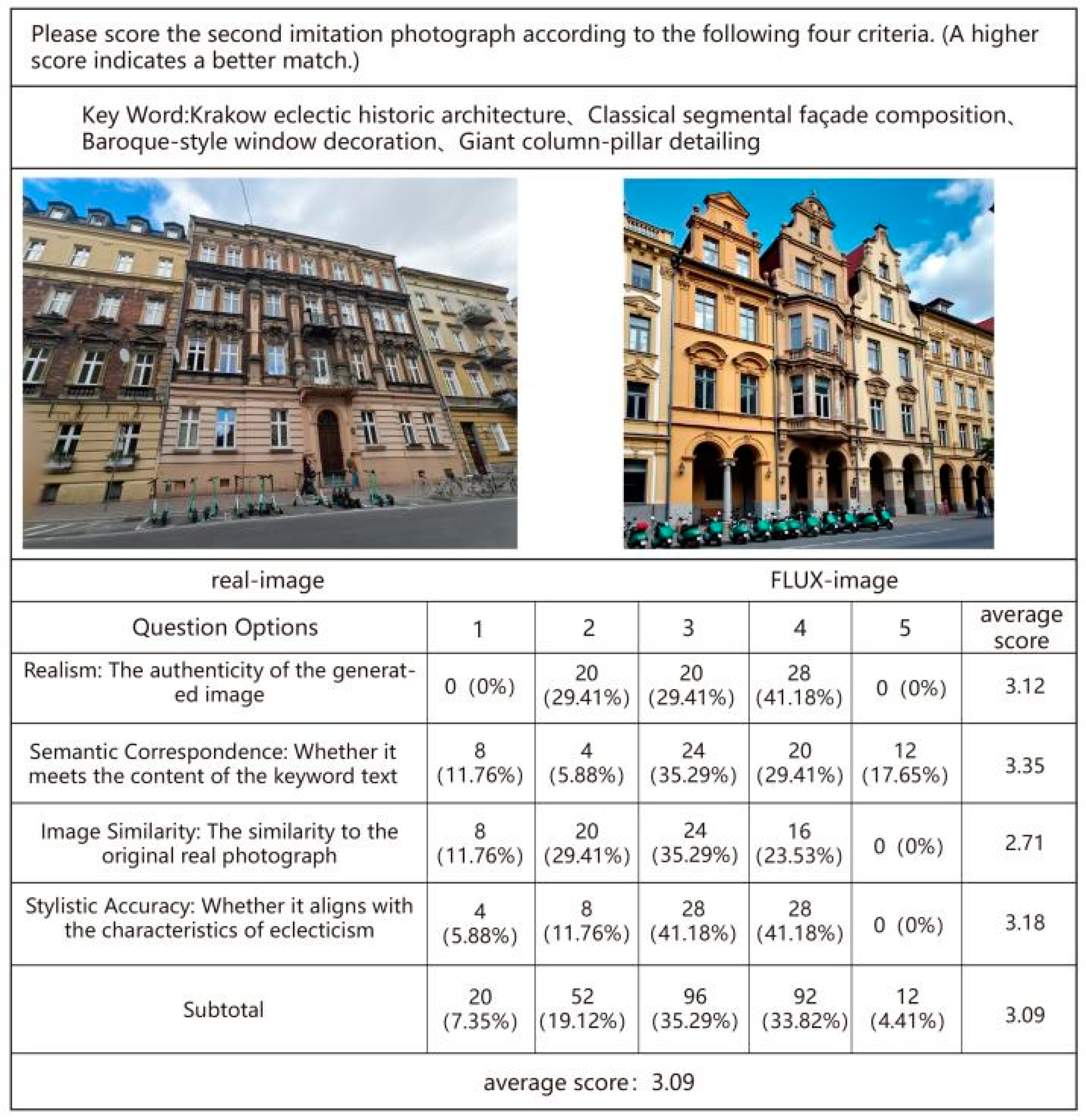

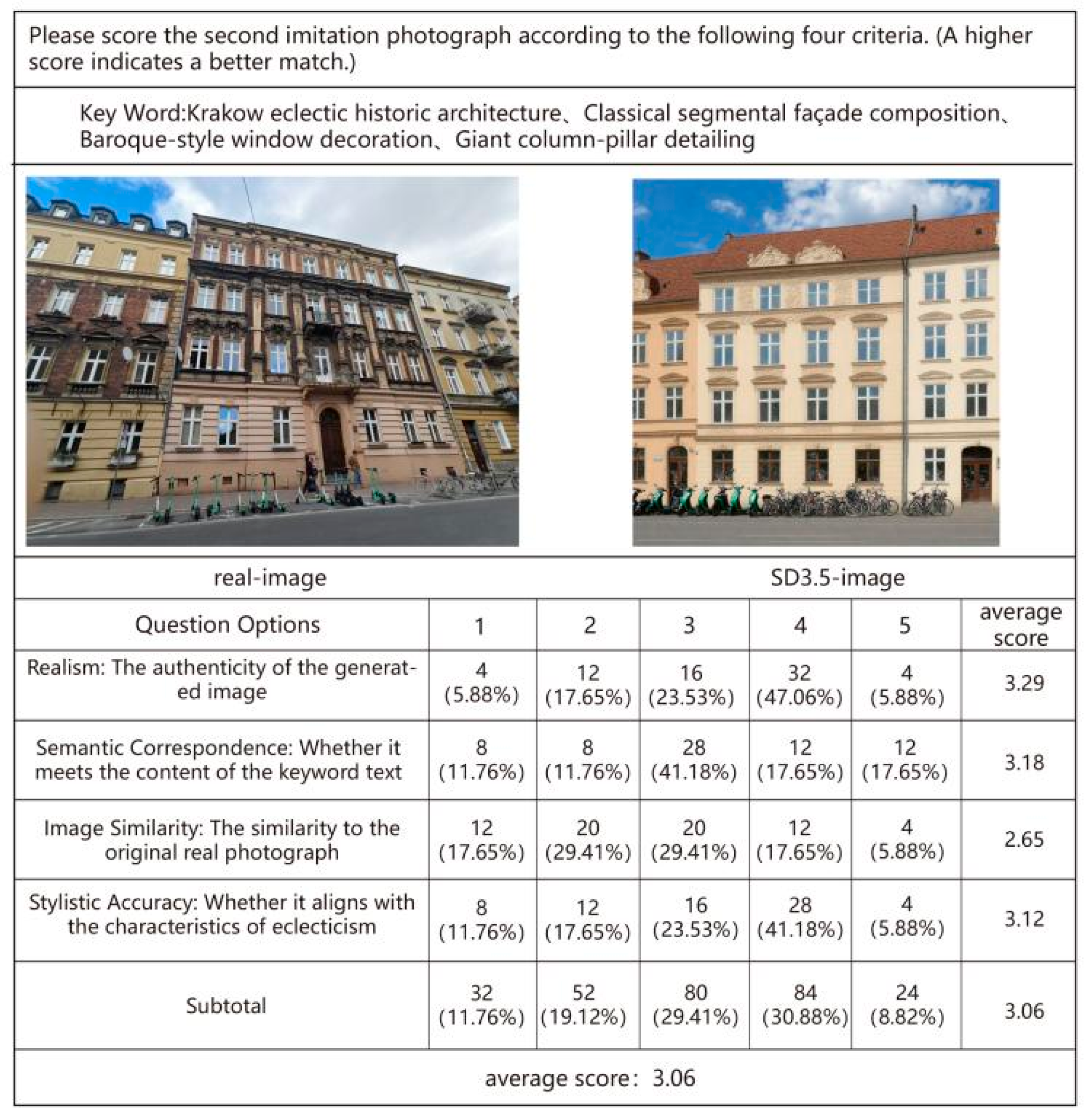

While quantitative metrics can objectively reflect image quality at a data level, a nuanced understanding of deeper issues remains reliant on subjective human judgment, particularly from individuals with specialized expertise. These issues include the accuracy of architectural style, the appropriateness of elements, and conformity to design intent. Consequently, this study convened an evaluation panel comprising 68 experts from the field of architecture. The panel members possessed diverse backgrounds, encompassing scholars engaged in historical building preservation and regeneration research, as well as professionals specializing in architectural design and its theoretical foundations. The expert panel was tasked with conducting subjective assessments of Krakow's Eclectic building facade images generated by different AI models.

During the evaluation process, experts initially observed a set of 'real images' presented in

Figure 16, which served as references. They then compared these with corresponding 'emulated images' generated by different models (FLUX, FLUX-LoRA, and SD 3.5). Throughout this assessment, the experts also consulted the 'semantic labels' (i.e., the textual prompts used during training) that were employed to generate the images, providing a basis for stylistic description. They rated each AI-generated image using a 1-5 point scale, where 5 represented the highest concordance with either the real image or the textual prompt. This rating considered four key dimensions: firstly, Realism, assessing whether the generated image appeared to be an authentic photograph of a building. Secondly, Semantic Correspondence evaluated whether the image accurately reflected the architectural style, key elements, and compositional features described in its semantic label. Thirdly, Image Similarity considered the degree of resemblance between the generated image and its corresponding 'real image' regarding overall style, composition, and critical details. Finally, Stylistic Accuracy involved scrutinizing whether the image faithfully reproduced the typical characteristics and nuanced distinctions of Krakow's Eclectic architectural style.

Based on the preliminary results from the expert scoring rubrics presented in

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 (which correspond to comparisons between real images and those generated by the FLUX-LoRA, FLUX, and SD3.5 models, respectively; one illustrative set of building comparison cases is detailed herein), the following preliminary conclusions can be drawn:

The FLUX-LoRA model demonstrated superior overall performance. In evaluations of this model (referred to as 'LoRA Faker' in the corresponding video; see quantitative results in

Figure 17 and qualitative scores in

Figure 18), its average scores across all four dimensions were significantly higher than those of the other two models. For instance, it achieved an average Realism score of 4.24 and a Stylistic Accuracy score of 4.06. Its performance was particularly prominent in the critical dimensions of 'Realism' and 'Stylistic Accuracy,' earning high commendation from the expert panel.Regarding the accurate capture of stylistic features, experts generally concurred that facades generated by the FLUX-LoRA model more precisely captured and reproduced the complexity and uniqueness inherent in Krakow's Eclectic architecture.For instance, a comparison of the first set of images in

Figure 16 reveals that the FLUX-LoRA model effectively reproduced several key features. These included the classic tripartite composition of the facade, the proportions and ornamentation of the windows, the rich stratification of cornice moldings, and volume. In contrast, images generated by the SD3.5 model appeared overly simplified and generalized. The base FLUX model, while better, was somewhat inferior in terms of detail coordination and stylistic purity.Notably, the experts also highlighted another strength of the FLUX-LoRA model. Its generated images not only visually emulated the target style proficiently but also demonstrated, to a certain extent, a capacity to respond to and reorganize typological elements embedded within the input textual prompts. Such elements included 'classical composition', 'Baroque-style ornamentation,' and 'colossal pilaster/colonnade-like decoration'. This observation aligns closely with the typologically-guided strategies emphasized in this study during dataset construction and label optimization.

A synthesis of quantitative computer vision metrics and subjective evaluations from the architectural expert panel confirms that our proposed methodology—integrating typological analysis with LoRA fine-tuning—has yielded encouraging results. This was observed in the task of stylistic transfer for Krakow's Eclectic building facades. The LoRA-fine-tuned model produced images that were more photorealistic and more aligned with the target distribution at a data level. More crucially, from the perspective of architectural experts, its generated facades demonstrated significantly superior performance. This superiority was evident in stylistic accuracy, elemental appropriateness, and the comprehension and expression of specific architectural 'types', compared to baseline models lacking targeted fine-tuning.

4. Discussion

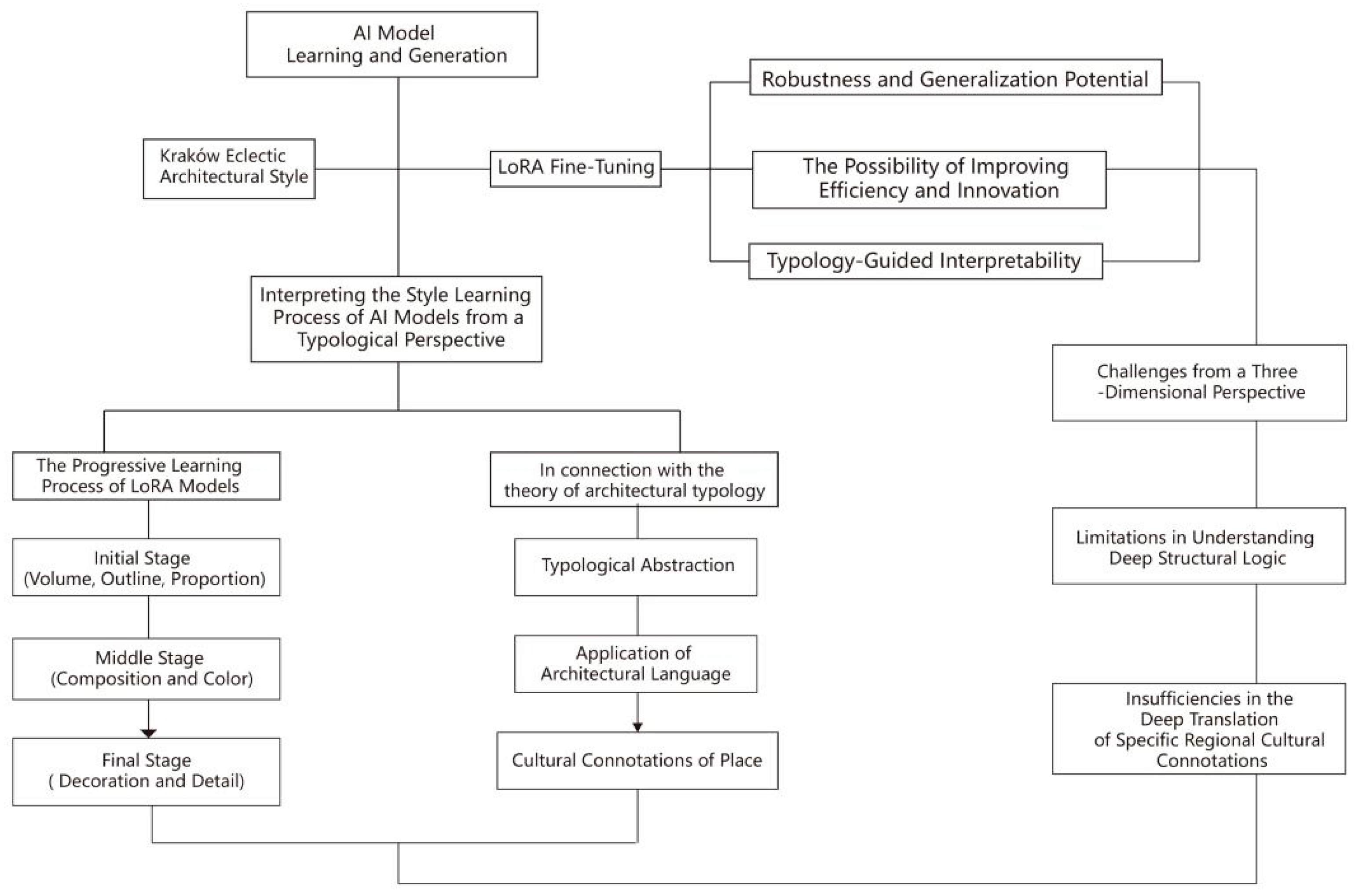

This chapter offers a deeper interpretation and discussion of the experimental results. Initially, we adopt an architectural typological perspective to thoroughly analyze the intrinsic mechanisms by which AI—particularly Diffusion Models fine-tuned with LoRA—learns and reproduces historic architectural styles. The relationship between these mechanisms and core typological theories is also explored. Subsequently, a comprehensive analysis is presented, evaluating the efficacy, value, and broader contextual significance of the methodology developed in this study. Finally, we address the current study's limitations and delineate promising avenues for future research.

4.1. Interpreting Stylistic Learning in AI Models

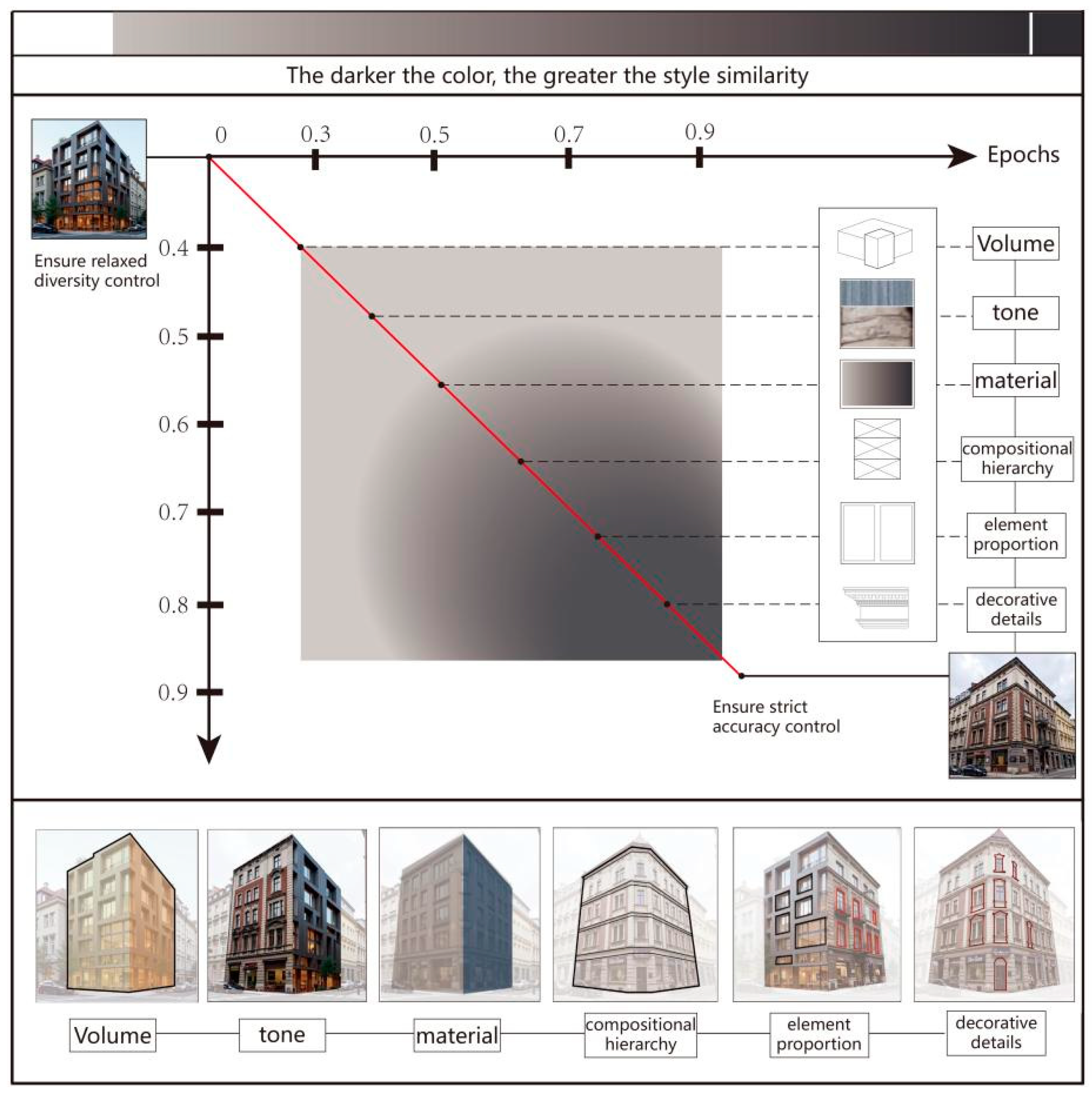

The core of this research lies in exploring how architectural typological principles can guide and optimize AI models for the 'stylistic emulation' and re-creation of historic architectural styles. Observations of Krakow's Eclectic building facade images, generated by the LoRA model at different training stages and with varying weight settings (See

Figure 14), clearly reveal a stylistic learning and reproduction process. This process progresses from macroscopic to microscopic levels and from overall to localized features. Notably, this developmental trajectory exhibits significant parallels with the analytical and comprehension methods employed in architectural typology for understanding building 'types' (See

Figure 21).

4.1.1. Progressive Learning in LoRA Models

The learning trajectory of LoRA models, particularly when acquiring specific architectural styles such as Krakow's Eclecticism, is not instantaneous. Instead, it is a process of gradual deepening and hierarchical progression. This progression is often concomitant with variations in technical parameters, such as decreasing loss values resulting from an increased number of training epochs, or an elevation in LoRA weights applied during inference. Specifically, this process can be generally categorized into several stages. During the initial stage, the model first captures the macroscopic features of the target style. These include aspects such as the overall building volume, approximate proportional relationships, and the primary compositional outlines of the facade. At this stage, generated images may begin to formally approximate the target. However, they typically exhibit indistinct details and rather generalized material and color palettes. This phase can be interpreted as the model establishing an initial 'first impression' or a foundational 'skeletal understanding' of the style. Progressing to the intermediate stage, with deepened training or increased LoRA weights, the model begins to learn and reproduce the principal compositional elements and chromo-material characteristics of the facade with greater precision. For instance, it becomes more adept at discerning different materialities (e.g., brickwork, stone, stucco) and starts to emulate the distinctive color schemes and lighting effects inherent to the target style. Concurrently, a more accurate articulation of primary facade compositional elements—such as tripartite divisions, fenestration patterns, and entablature treatments—becomes evident.In the later stage, characterized by comprehensive training or the application of higher LoRA weights, the model shifts its focus to learning finer decorative elements and the nuanced relationships between components. This includes the accurate reproduction of details such as period-specific orders (column types), window ornamentation, moldings, and sculptural details. Moreover, it captures the intrinsic logic governing the proportional, combinatorial, and spatial relationships among these elements. At this juncture, the generated images not only achieve high visual fidelity but also, to a certain extent, embody the 'compositional principles' of the target style.

This learning and reproduction trajectory, progressing from macroscopic to microscopic scales and from holistic to localized features, bears a striking resemblance to the cognitive process by which architects comprehend an architectural type or style. Architects typically first apprehend the overall form and spatial organization of buildings. Subsequently, they delve progressively deeper into materials, construction methods, and decorative detailing.

4.1.2. Correlation with Architectural Typological Theory

The stylistic learning and reproduction process exhibited by LoRA models shares profound intrinsic connections with core theories in architectural typology. This is particularly evident when considering the concepts of 'Type' and 'Urban Fabric' as articulated by Aldo Rossi in his seminal work,

The Architecture of the City [

11].

Abstraction and Reproduction of 'Type': Rossi conceptualized 'type' in architecture not as a static, immutable form, but as a profound organizational structure and generative logic that transcends specific formal manifestations. He argued that 'type' adapts to diverse socio-cultural contexts through the continuous 'transcoding' and 're-creation' of forms and elements over historical trajectories. This adaptation progressively shapes buildings with unique styles and local character. Similarly, LoRA models, by processing extensive image datasets, effectively attempt to abstract 'type' characteristics— latent organizational principles and constituent elements—of a specific style from its visual phenomenology. When generating new images, these models then engage in 'reproduction' and 'variation' of these learned 'type' features. The typology-guided dataset construction and label optimization employed in this study are specifically designed to assist AI models in more effectively identifying and learning this deeper 'type' information.

Acquisition and Application of 'Architectural Language': Rossi perceived architecture as a 'language,' possessing its own 'vocabulary' (architectural elements), 'grammar' (compositional rules), and 'context' (cultural background). The LoRA model's process of learning a specific style can be seen as acquiring a particular 'architectural visual language.' In the initial stages, it might only grasp a vague 'intonation' and 'outline.' During the intermediate phase, it begins to master the principal 'vocabulary' and 'syntactic structures.' By the later stages, it can more fluently utilize this 'language' to 'narrate stories' (i.e., generate photorealistic facade images) that conform to the specific style. The hierarchical processing of image labels in this study—progressing from overall type to detailed elements—helps the AI model in more systematically learning this 'architectural language'.

Place-making and Affective Dimensions: Typological theory also emphasizes that architecture transcends mere physical existence; it serves as a vessel for culture, memory, and history, possessing strong local character and profound affective dimensions [

52]. By learning lighting, materiality, and specific decorative elements, LoRA models, also engage with the capacity to evoke particular place-atmospheres and affective experiences. Although AI currently achieves this primarily through visual imitation, enhancements in the 'realism' and 'stylistic accuracy' of its generated outputs undeniably amplify the viewer's emotional resonance with specific historical places.

From a typological perspective, the LoRA-based stylistic transfer process in this study transcends mere visual replication. It can be more accurately understood as a computational process involving the learning, abstraction, transcoding, and reproduction of specific architectural 'types.' This typological lens offers valuable insights for a deeper comprehension of AI's generative mechanisms. Furthermore, it provides beneficial implications for future advancements, such as enabling AI to genuinely understand and apply the fundamental principles of architecture.

4.2. Methodological Efficacy and Value

The methodology proposed in this study, which integrates architectural typology-guided LoRA fine-tuning, has demonstrated significant efficacy in addressing the complexities of Krakow's Eclecticism—a style characterized by both intricacy and data scarcity. Furthermore, this approach possesses multifaceted applicative value.

4.2.1. Handling Complex, Data-Scarce Styles

Krakow's Eclectic architectural style is inherently characterized by a high degree of complexity. It combines formal languages and decorative elements from diverse historical periods, further shaped by regional cultural influences that have fostered unique micro-variations. Concurrently, high-quality, structured image datasets for such non-mainstream styles are comparatively scarce. These two factors collectively present formidable challenges to AI models concerning both learning and stylistic transfer.

Experimental results, as detailed in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, indicate that the methodology proposed in this study can effectively address these challenges. Firstly, even with a relatively limited training dataset, the FLUX-LoRA model—guided by typology and fine-tuned with LoRA—generated facade images superior to those from baseline models (i.e., standard Stable Diffusion and the unfine-tuned FLUX). This superiority was evident in visual realism, stylistic accuracy, and richness. This demonstrates the method's robust learning capability and style reproduction capacity when handling complex, data-scarce styles. Secondly, expert evaluation findings further corroborated these results. Images generated by the FLUX-LoRA model not only resembled authentic Krakow's Eclectic architecture. They also demonstrated an ability, to some extent, to respond to typological concepts embedded within textual prompts, thereby producing new variants with a degree of inherent rationality. This suggests that the method transcends simple overfitting, instead learning intrinsic stylistic regularities and possessing a degree of generalization potential.

4.2.2. The Role of Typological Guidance in Enhancing Generation Quality and Interpretability

A pivotal innovation of this research lies in the systematic integration of architectural typological principles throughout the entire AI model training and application pipeline. This guidance is crucial for enhancing both the quality of generated images and the interpretability of model behavior. On one hand, typology-driven image screening and label optimization provide AI models with more precise and structurally coherent learning materials.This not only enables the model to move beyondmere surface texture and color imitation but alsodirects it to focus on more profoundcompositional principles, proportionalrelationships, and the organizational logic ofarchitectural elements, thus enhancing the overall generation quality.As expert evaluations indicated, typologically-guided models performed superiorly in terms of 'Semantic Correspondence' and 'Stylistic Accuracy'. On the other hand, typology offers a theoretical framework for understanding and analyzing the AI model's stylistic learning process. As discussed in

Section 4.1, the LoRA model's learning trajectory can be likened to an architect's process of understanding and deducing 'types.' This comparison not only helps to clarify the AI’s 'perceptive' and 'learning' mechanisms but also offers valuable insights for optimizing the model and refining the generation process. Consequently, the 'black box' nature of AI becomes, to some extent, more 'transparent,' thereby enhancing its trustworthiness and controllability as a design assistance tool.

4.2.3. Potential Enhancements to Traditional 'Stylistic Emulation' Practices

Traditional practices for emulating historic architectural styles—whether executed through manual drafting or early computer-aided design—have historically relied on the individual designer's expertise, technical skill, and depth of understanding regarding historical precedents.These processes are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and yield inconsistent results. Consequently, ensuring stylistic accuracy and consistency has remained a persistent challenge.

The typology-guided AI 'stylistic emulation' methodology proposed in this study offers several improvements to traditional practices. For instance, once an AI model is effectively trained, it can rapidly generate a multitude of facade proposals adhering to specific stylistic requirements. This high efficiency is invaluable for multi-alternative comparisons and rapid iterations during preliminary design phases. Furthermore, because AI learning is predicated on unified datasets and explicit guidance, the stylistic consistency of its outputs may surpass that of traditional methods, which often rely purely on individual subjective judgment.

Moreover, systematic typological guidance enables AI models to acquire a more comprehensive and profound understanding of stylistic knowledge than might be achievable by some individual designers using traditional methods. This is particularly pertinent for non-mainstream styles or those with limited extant documentation. AI can distill subtle features and statistical regularities from extensive image corpuses that might be imperceptible to the human eye. Consequently, this capability could elevate the finesse and nuanced fidelity of stylistic reproduction to new echelons.

Although this research primarily focuses on 'stylistic emulation,' AI models guided by typology also unlock new potentialities for stylistic 're-creation' and innovative design. Through an abstracted comprehension of 'types' and a flexible 'transcoding' of elements, AI can assist designers. It aids in exploring novel stylistic expressions that are contemporary yet respectful of historical context. This capability allows a progression beyond mere replication, facilitating a genuine 'adaptation of historical precedents for contemporary use'.

In summary, the methodology proposed in this research, which combines architectural typology-guided LoRA fine-tuning, has demonstrated its efficacy in handling complex, data-scarce styles. More significantly, it provides a framework with greater theoretical depth and practical value for understanding and applying AI in architectural stylistic emulation and innovative design. This contribution not only improves the quality and interpretability of AI-generated imagery but also introduces new potentialities and insights for traditional architectural design practices.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

Despite the positive advancements achieved by the proposed methodology—which integrates architectural typology-guided LoRA fine-tuning for the 'stylistic emulation' and re-creation of Krakow's Eclectic building facades—it is imperative to acknowledge its limitations. These limitations not only reflect prevalent challenges in the current application of AI technology within architectural design but also highlight specific areas requiring further research efforts in the future.

4.3.1. Predominant Focus on 2D Facades and Significant Challenges in 3D Modeling

The core focus of this research has been on stylistic transfer for two-dimensional (2D) architectural facades. While the generating of high-quality 2D facades holds significant value for schematic representation and preliminary conceptual design, architecture is fundamentally a three-dimensional (3D) spatial entity. Extending the findings from 2D facade research to the automated generation of 3D architectural models remains a formidable challenge, primarily manifested in several aspects.Firstly, inferring or generating 3D geometry from 2D images requires addressing inter-view consistency and the complex topological and spatial adjacency relationships among architectural components.Current AI models often face difficulties in ensuring the accuracy and rationality of generated geometries when transitioning from 2D to 3D.[

36,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Secondly, compared to abundance of 2D image data, high-quality 3D architectural model datasets with detailed semantic annotations are considerably scarcer. This scarcity limits the depth and scope of AI model learning within the 3D domain. Thirdly, the generation and processing of 3D models typically require greater computational resources than their 2D counterparts, thereby imposing higher requirements on model training and inference efficiency.

Therefore, while the methodology of this study might offer some insights for the stylistic treatment of three-dimensional (3D) models—for instance, by attempting to combine stylized facades from multiple viewpoints—significant hurdles remain. Achieving truly AI-driven, intelligent generation of 3D architecture that accurately conforms to specific styles remains a long-term research challenge

4.3.2. Limitations in AI's Understanding of Deep Structural Logic and Functional Organization