Appendix A.1. Emotional criteria.

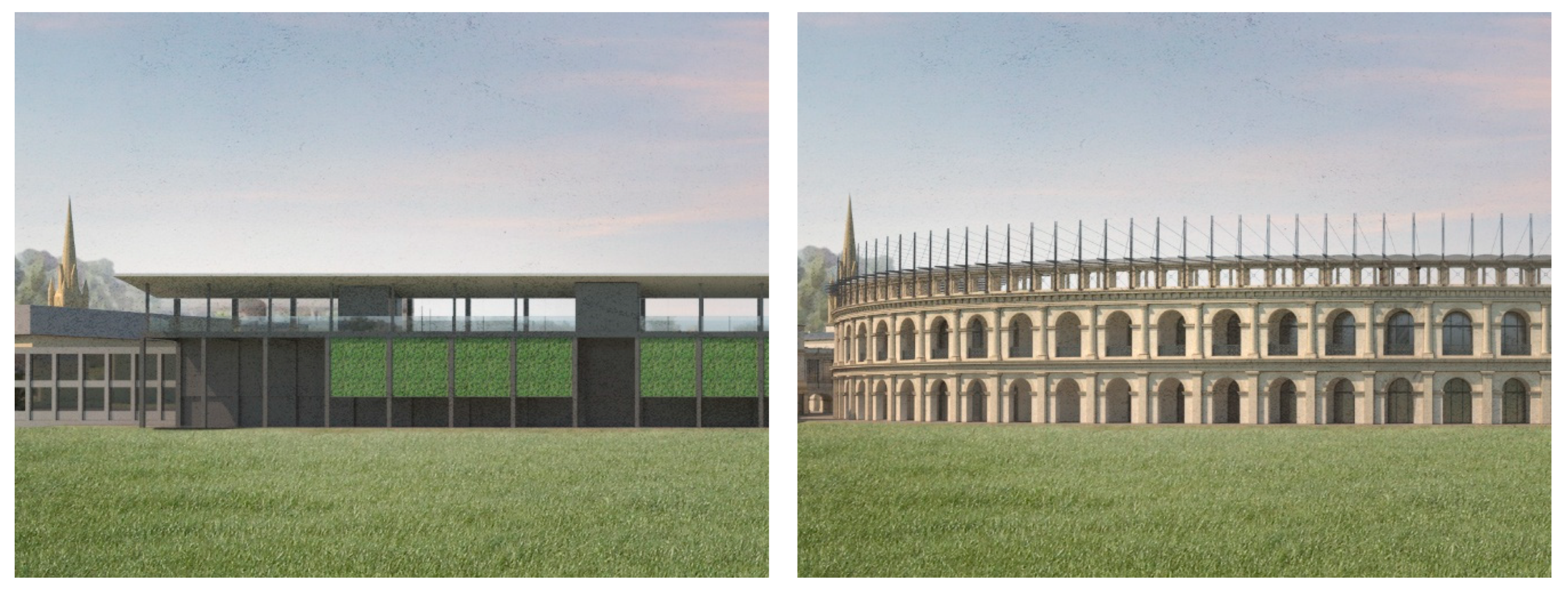

A reliability assessment helps to identify the consistency and dependability of the LLM-based architectural evaluation tool. The inherently stochastic nature of generative AI systems means that identical prompts can yield different responses. A test-retest reliability analysis is conducted by querying ChatGPT-4o ten times with identical prompts for the same architectural pair in

Figure 1. The standard deviation from the mean is the simplest consistency measure. (A test-retest reliability coefficient

r is not useful here because successive trials vary randomly and are not supposed to converge). This version of ChatGPT was chosen for this test because it is the most widely used at the time of writing.

A slightly modified prompt is employed, and each query is entered as a new chat:

“Use the set of ten qualities {beauty, calmness, coherence, comfort, empathy, intimacy, reassurance, relaxation, visual pleasure, well-being} (“beauty–emotion cluster”) that elicit a positive-valence feeling from a person while physically experiencing a built structure, to investigate the two uploaded pictures of similar buildings. Evaluate the conjectured relative emotional feedback by comparing the two images in a binary preference (1 for the preferred image and 0 for the rejected image for each of the 10 qualities) to give a preference for one over the other. The sum of the values for each image should be 10. Give the answer as (LHS, RHS).”

This LLM produced the following results when evaluating for the emotional criteria:

(LHS, RHS) = (0, 10) seven times and (1, 9) three times.

Mean = (0.3, 9.7) and standard deviation = (0.46, 0.46).

The lesson for researchers is that, to improve reliability, an evaluation should be repeated several times.

Extensive trials indicated that the best model to use for this comparative analysis is the more advanced ChatGPT 4.5, not 4o, which is what the body of the paper quotes for the emotional evaluation. The reason for this choice is that the detailed explanations given by ChatGPT 4.5 proved to be incisive and unbiased, and not because the numbers agreed with the authors’ expectations. According to ChatGPT, version 4.5 is slower but more deterministically reliable in structured scoring tasks than 4o, because 4.5 has lower stochastic entropy and is better aligned with fixed evaluation frameworks.

The second reliability assessment checks whether different LLM versions, and distinct LLMs, will produce comparable results. Inter-version reliability is established by comparing evaluations across ChatGPT-4o, o3, o4-mini, o4-mini-high, 4.5, and 4.1 using the image set in

Figure 1. The evaluation trial is extended to include the LLMs Copilot and Perplexity (neither of which has its own AI engine but relies on those of other LLMs). The following numbers will of course change over repeated runs, so this is merely an indication of what to look for in a reliability check.

Single-trial results from ChatGPT-4o, o3, o4-mini-high, 4.5, 4.1, Copilot, and Perplexity were all equal for this case: (LHS, RHS) = (0, 10), whereas ChatGPT o4-mini scored (2, 8).

Mean = (0.25, 9.75) and standard deviation = (0.66, 0.66).

Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Kimi K1.5 — LLMs with their own AI engines — gave inconsistent results with the above simple prompt. This was due to their conjecturing of effects for the emotional qualities that amounted to speculation. There is an evident training data bias that conflates aesthetic and emotional criteria. Those LLMs’ detailed explanations revealed that their results were not based strictly on documented psychological feedback but were influenced by opinions on contemporary aesthetics and styles. To use those LLMs, a more detailed prompt will be necessary to prevent the LLM from picking subjective opinions instead of searching through scientific data. An experiment with Gemini 2.5 Pro gave better results, as detailed below in

Appendix A.3.

This exercise in response consistency is not a rigorous reliability test for the emotional evaluation module. It simply points out what researchers must do in a systematic manner to validate this model for future investigations. Another important point that came out of this is that distinct LLMs answer questions differently, by drawing upon different sources that may indeed be biased. For this reason, it is essential to ask the LLM for a detailed justification for each number in the evaluation and to check this for impartiality.

Appendix A.2. Geometric criteria.

The test-retest reliability analysis was repeated for the 15 fundamental properties by querying ChatGPT-4o ten times with an identical prompt for the same architectural pair in

Figure 1. Each query was entered as a new chat. A slightly modified prompt was used this time, along with the descriptive list of the 15 properties:

“Evaluate these two images of buildings, using the 15 criteria uploaded as Alexander’s Fifteen Fundamental Properties of living geometry. The relative comparison should be presented as a set of numbers (LHS, RHS), where LHS = total score for the relative presence (dominance) of the properties in the LHS image, and RHS = total for score for the relative presence (dominance) of the properties in the RHS image. Score the pair of images as follows: if one property is clearly dominant in one of them, give a 1 to it and 0 to the other. If both images have comparable degrees of one property, or the difference is very small, give a 0 to both. For this reason, the totals could come out to be LHS + RHS < 15.”

ChatGPT-4o produced the following results when evaluating the geometrical criteria ten consecutive times (listed here in no particular order):

(LHS, RHS) = (0, 15), (0, 13), (1, 13), (2, 12) four times, (3, 10) twice, (3, 11).

Mean = (1.8, 12.0) and standard deviation = (1.1, 1.4).

The second reliability assessment compared evaluations across ChatGPT-4o, o3, o4-mini, o4-mini-high, 4.5, 4.1, Gemini 2.5 Pro, and Perplexity using the image set in

Figure 1. The scores of single trials are as follows (again, repeated trials using new chats will inevitably give varied results):

ChatGPT-4o (LHS, RHS) = (0, 13), o3 = (3, 11), o4-mini = (0, 14), o4-mini-high = (0, 15), 4.5 = (0, 15), 4.1 = (4, 11), Gemini 2.5 Pro = (0, 14), Perplexity = (1, 12).

Mean = (1, 13) and standard deviation = (1.5, 1.5).

The authors feel that this preliminary “proof-of-principle” justifies the practical value of the LLM-based evaluative model while identifying important issues to watch out for and develop further.

Appendix A.3. The occasional need for a more detailed prompt.

As already noted in

Appendix A.1, the LLM Gemini 2.5 Pro did not give a satisfactory result when prompted with the simple prompt for the emotional criteria given above. (Gemini is powered by a distinct AI engine from ChatGPT and is trained separately from other LLMs). A more detailed prompt elicited an accurate scoring for the emotional evaluation of

Figure 1 as (LHS, RHS) = (2, 8) supported by the detailed explanations reproduced in full below.

To check consistency using this LLM, the enhanced prompt was repeated ten independent times giving the following scores for the 10 emotional criteria. Only the readout from the first trial is recorded below. However, the variance over ten evaluations discourages using this LLM for the objective diagnostic model — ChatGPT 4.5 is preferred for now. (Improvement while using Gemini 2.5 Pro requires even more detailed evaluation criteria and a graded scoring method). The ten scores are:

Gemini 2.5 Pro: (LHS, RHS) = (2, 8), (3, 7), (2, 8), (4, 6), (1, 9), (2, 8), (4, 6), (1, 9), (5, 5), (3, 7).

Mean = (2.7, 7.3) and standard deviation = (1.27, 1.27).

Prompt to Gemini 2.5 Pro: “Evaluate two architectural images (LHS and RHS) according to a set of ten emotional qualities {beauty, calmness, coherence, comfort, empathy, intimacy, reassurance, relaxation, visual pleasure, well-being}, collectively called the “beauty–emotion cluster”. Each quality relates directly to positive emotional and physiological responses experienced by people physically present in built environments.

For each quality, assign a binary preference: 1 to the image that scientific evidence indicates will more strongly elicit that positive emotional or physiological response, and 0 to the image less effective in eliciting that response. The sum of values across all ten qualities must equal 10. Present your final result as: (LHS, RHS).

Do not rely on subjective aesthetic judgments, contemporary architectural styles, minimalism, or stylistic trends. Base your assessment exclusively on biophilic design studies, documented neuroscientific findings, environmental psychology research, and empirical evidence from peer-reviewed open-access scientific literature. Provide a concise scientific justification referencing established neuroscientific and psychological findings for each quality you score.”

Gemini 2.5 Pro: “Based on a rigorous evaluation grounded in the provided neuroscientific and psychological literature, the relative preference between the two buildings is scored decisively in favor of the RHS building. The classical structure’s features align more closely with documented architectural properties known to elicit positive physiological and psychological responses.

Final Result: (2, 8).

Scientific Justification per Quality.

Beauty: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Neuroaesthetics research indicates that aesthetic appreciation is linked to the activation of the brain’s emotion-valuation system, which includes the orbitofrontal cortex. Designs with harmony and symmetry can create feelings of happiness. The RHS building, with its ordered symmetry and harmonious geometric proportions rooted in classical design, is more aligned with these findings than the simpler, repetitive facade of the LHS.

Calmness: (1, 0).

Scientific Justification: Biophilic design, which incorporates natural elements, is strongly linked to stress reduction and promoting calm. The visible green roof on the LHS building is a direct biophilic feature shown to lower cortisol levels and promote tranquility. Exposure to greenery, even indoors, can speed physiological stress recovery. This provides a direct, documented pathway to inducing calmness.

Coherence: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Coherence is defined as the ease of organizing and comprehending a scene, and it is a key psychological dimension in the experience of architecture. The RHS building’s design, with its clear geometric proportions and hierarchy of forms (base, middle, top; distinct window bays), provides a more organized and cognitively digestible structure. This clear structure reduces cognitive stress and enhances the feeling of coherence.

Comfort: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Psychological comfort is associated with feelings of safety, familiarity, and well-being. Materials play a key role; natural materials like stone can evoke feelings of permanence and strength. Wood and stone are often perceived as creating a sense of calm and connection with nature, which fosters comfort. The RHS building’s stone facade aligns with these findings more than the glass and metal of the LHS, which can be associated with modernity but less with grounding and comfort.

Empathy: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Empathy in architecture is linked to an embodied, multi-sensory experience where the user feels a connection to the space. Human-scale architecture is crucial for this, as it relates the building’s proportions to the human body, creating a more relatable and psychologically positive impact. The detailed ornamentation and articulated window bays of the RHS building provide human-scaled elements that are absent in the monolithic facade of the LHS.

Intimacy: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Smaller, enclosed spaces tend to foster focus and intimacy, while larger, open spaces promote exploration. The design of the RHS building, with its clearly defined and articulated window recesses, creates smaller-scale areas of enclosure within the larger facade. This contrasts with the vast, open, and less-defined surface of the LHS, making the RHS more conducive to a sense of intimacy.

Reassurance: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Reassuring environments are often those that feel stable and permanent. Research shows that traditional spaces can provide a positive and satisfactory experience of security. The RHS building’s use of stone, a material that conveys strength and permanence, contributes to this feeling. Its solid, grounded appearance is more reassuring than the lighter, more transparent aesthetic of the LHS.

Relaxation: (1, 0).

Scientific Justification: Exposure to nature is a well-documented method for stress reduction and relaxation. Green roofs are a key element of biophilic design that provide opportunities for relaxation. Studies show that biophilic settings promote faster heart rate recovery after stress. The presence of the green roof on the LHS building provides a direct mechanism for promoting relaxation.

Visual Pleasure: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Research into fractal patterns in visual art and design shows that humans are "hard-wired" to respond positively to the kind of ordered complexity found in nature, which can reduce stress levels by up to 60%. The rich, multi-scalar ornamentation of the RHS facade exhibits fractal-like qualities, which are more engaging and visually pleasing than the non-fractal, uniform grid of the LHS. Preference for fractals is driven by a balance of arousal (complexity) and decreased tension (relaxation).

Well-being: (0, 1).

Scientific Justification: Overall well-being is a holistic measure affected by numerous factors, including a sense of connection, safety, and positive emotional stimulation. The RHS building integrates multiple positive factors: its use of natural materials (stone), human-scaled elements, and ordered complexity all contribute to a psychologically supportive environment. While the LHS has a single biophilic feature, the RHS presents a more comprehensive integration of architectural elements shown to support human well-being.”