Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Video Surveillance and Analysis

2.3. Incubation Attentiveness, Egg Ventilation and Egg-Turning

2.4. Number and Time of Nest Departures

2.5. Relationship Between Ambient Temperature and Egg-Turning Frequency and Ventilation Time

2.6. Frequency of Male Food Deliveries and Female Feeding During Incubation

2.7. Statistical Analyse

3. Results

3.1. Breeding History

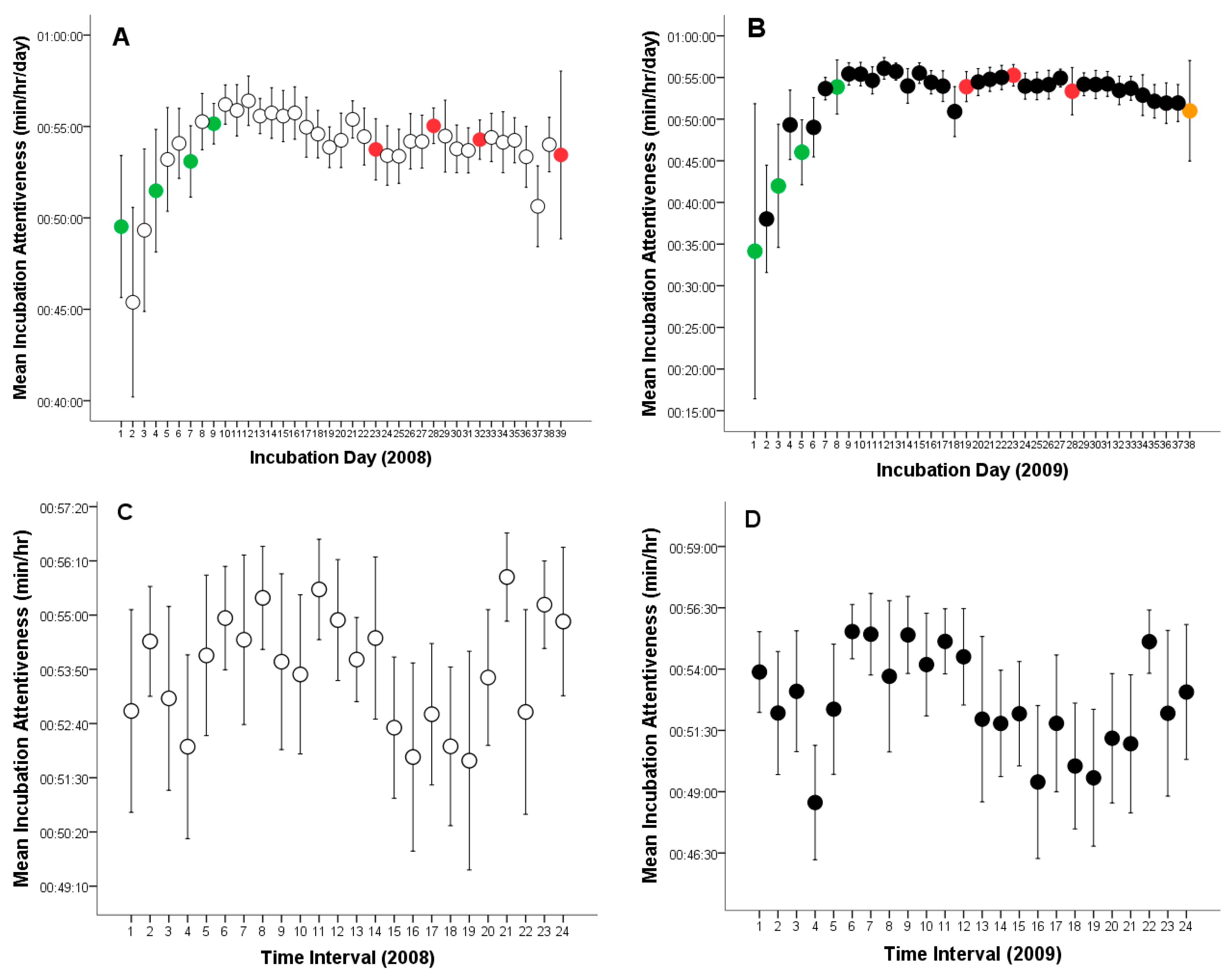

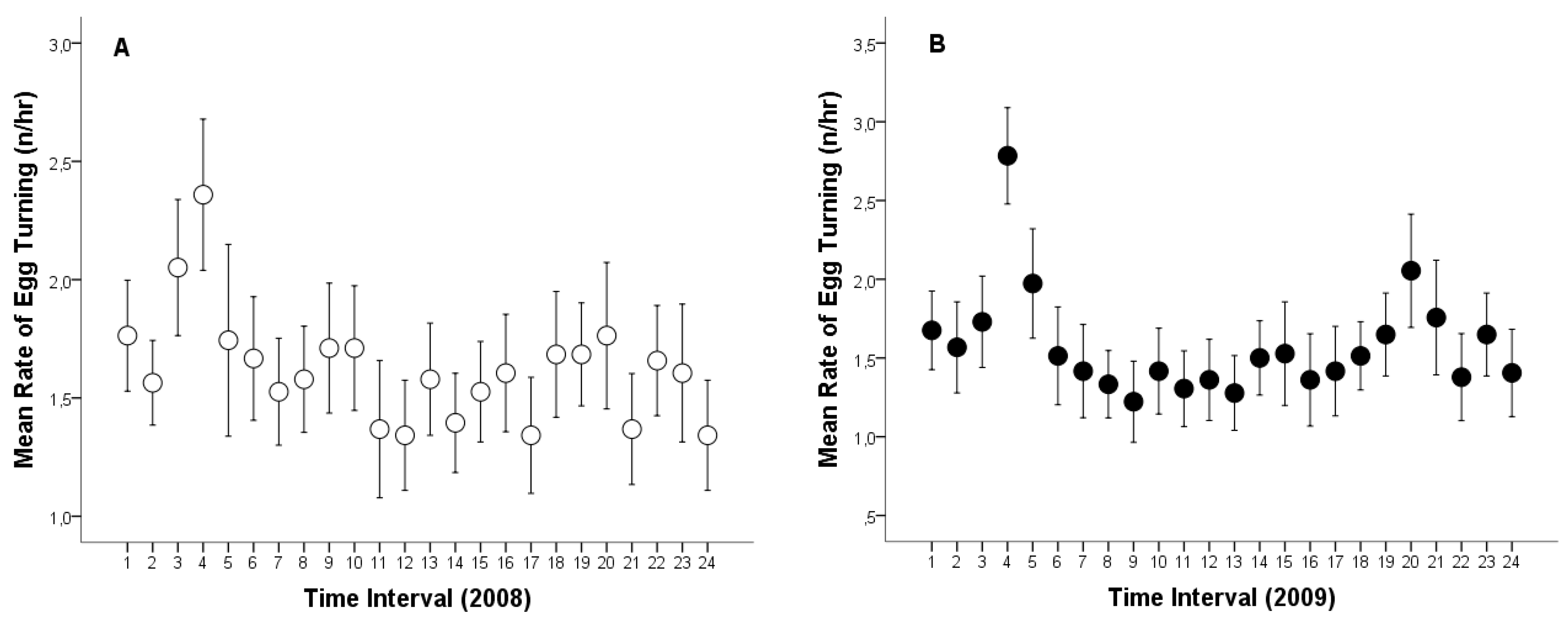

3.2. Incubation Attentiveness, Egg Ventilation and Egg-Turning

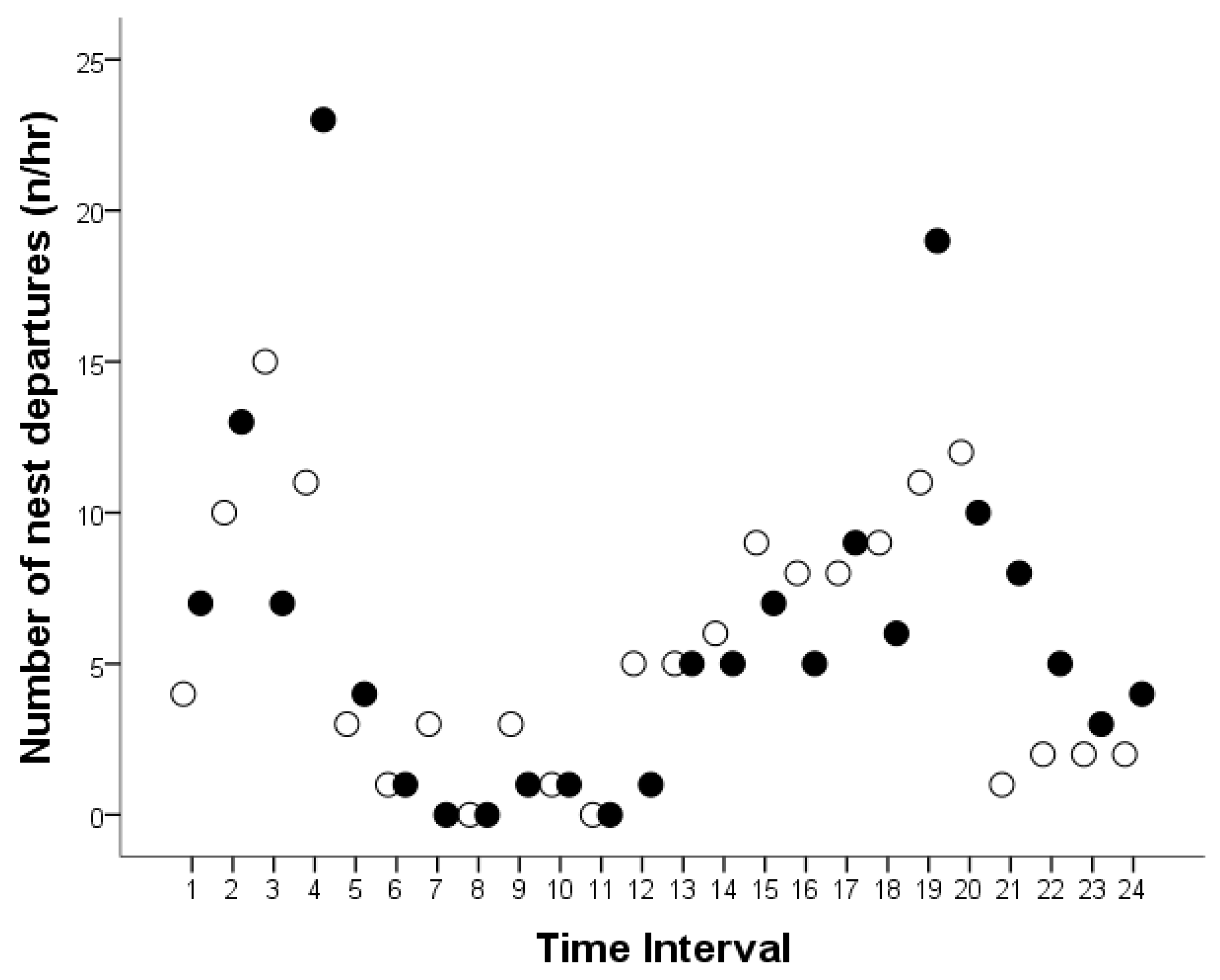

3.3. Number and Time of Nest Departures

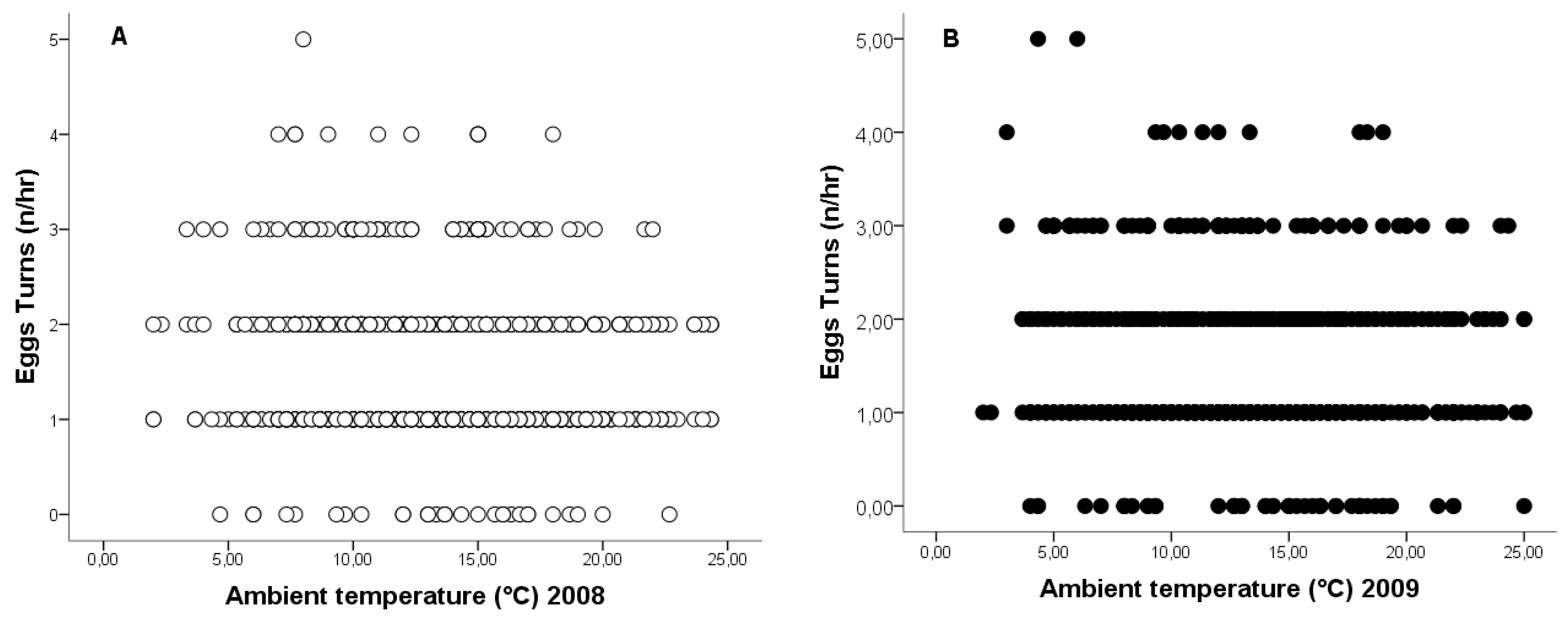

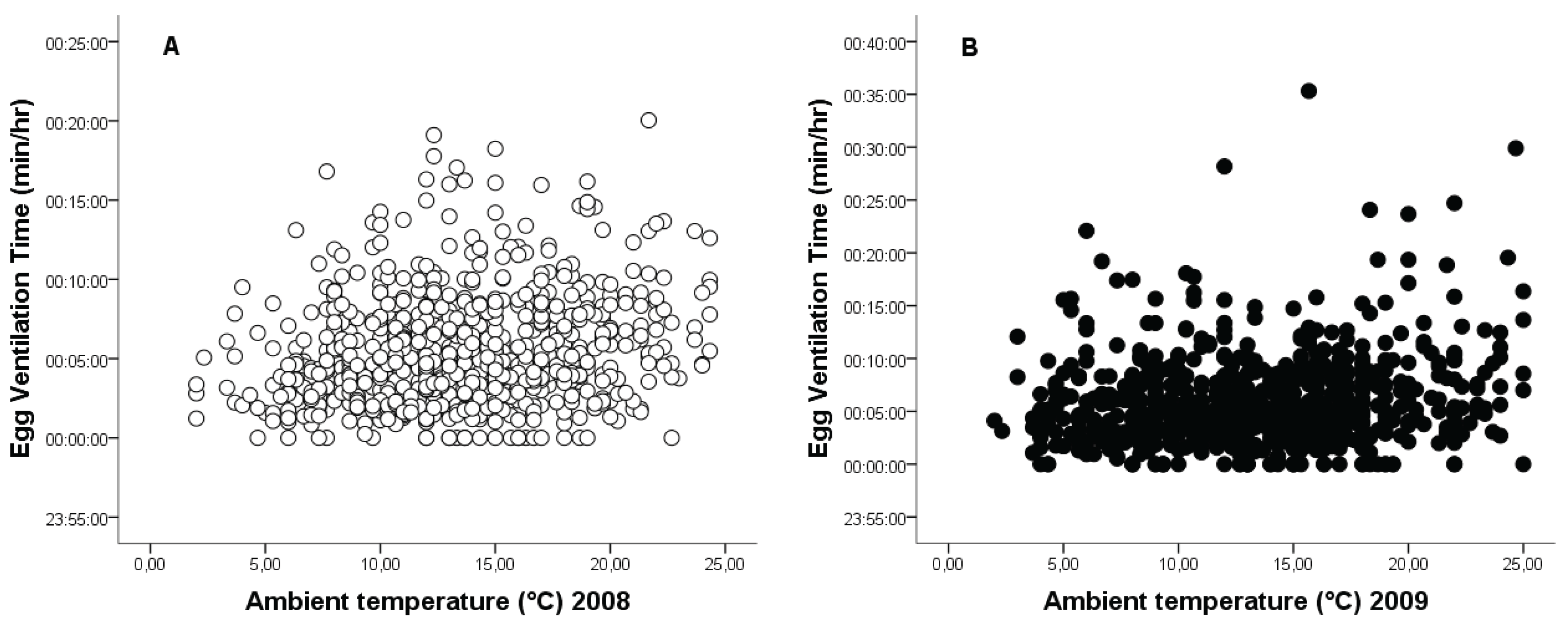

3.4. Relationship Between Ambient Temperature and Egg-Turning Frequency and Ventilation Time

3.5. Frequency of Male Food Deliveries and Female Feeding During Incubation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deeming, D.C. (Ed.) Avian incubation: behaviour, environment, and evolution; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Deeming, D.C. (Eds.) Nests, Eggs, and Incubation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wojczulanis-Jakubas, K.; Jakubas, D.; Kośmicka, A. Body mass and physiological variables of incubating males and females in the European Storm Petrel (Hydrobates P. pelagicus). The Wilson J. Ornithol. 2016, 128, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkhead, T.R.; Thompson, J.E.; Biggins, J.D.; Montgomerie, R. The evolution of egg shape in birds: selection during the incubation period. Ibis 2019, 161, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.D.; Groothuis, T.G.G. Egg quality, embryonic development, and post-hatching phenotype: an integrated perspective. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Birchard, G.F.; Deeming, D.C. Egg allometry: influences of phylogeny and the altricial-precocial continuum. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hepp, G.R.; DuRant, S.E.; Hopkins, W.A. Influence of incubation temperature on offspring phenotype and fitness in birds. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Conwey, C.J.; Martin, T.E. Effects of ambient temperature on avian incubation behavior. Behav. Ecol. 2000, 11, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nager, R.G. The challenges of making eggs. Ardea 2006, 94, 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mainwaring, M.C.; Hartley, I.R. The energetic costs of nest building in birds. Avian Biol. Resea. 2013, 6, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nord, A.; Williams, J.B. The energetic costs of incubation. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 152–170. [Google Scholar]

- Marasco, V.; Spencer, K.A. Improvements in our understanding of behaviour during incubation. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, G.S. Avian incubation. Egg temperature, nest humidity and behavioral thermoregulation in hot environment. Orn. Monogr. 1982, 30, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D. Incubation temperatures and behavior of Crowned, Black-winged, and Lesser Black-winged Plovers. Auk 1990, 107, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, B.C.; Mills, H. New software for quantifying incubation behavior from time-series recordings. J. Field Ornithol. 2005, 76, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, M.; Butcher, N.; Sharpe, F.; Stevens, D.; Fisher, G. Remote monitoring of nests using digital camera technology. J. Field Ornithol. 2007, 78, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Cooper, C.B.; Reynolds, S.J. Advances in techniques to study incubation. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty, T.D.; Elmore, R.D.; Fuhlendorf, D.S.; Loss, R.S. Influence of olfactory and visual cover on nest site selection and nest success for grassland-nesting birds. Ecology and Evolution. 2017, 7, 6247–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. (Ed.) Population limitation in birds; Academic Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliainen, E.; Loisa, K. Breeding biology and food of the Great Grey Owl, Strix nebulosa, in a north-eastern Finnish forest, Lapland. Aquilo Ser. Zool. 1977, 17, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hilden, O.; Helo, P. The Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa - a bird of the northern taiga. Ornis Fenn. 1981, 58, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola, H. (Eds.) Der Bartkauz Strix nebulosa; Die Neue Brehm-Bucherei 538: 1 -124. A. Ziemsen Verlag: Wittenberg-Lutherstadt, German, 1981.

- Mikkola, H. (Ed.) Owls of Europe; T & A.D Poyser Ltd.: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Korpimäki, E. Niche relationships and life-history tactics of the three sympatric Strix owl species in Finland. Ornis Scan. 1986, 17, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, L.E.; Mark, G.M.; Henjum, G.M.; Rohweder, S.R. Home range and dispersal of Great Gray Owl in Northeastern Oregon. J. Raptor Res. 1988, 22, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, L.E. , Mark, G.M., Henjum, G.M., Rohweder, S.R. Nestling and foraging habitat of Great Gray Owl. J. Raptor Res. 1988, 22, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, A. Breeding biology of the Great Gray Owl in Southeastern Idaho and Northwestern Wyoming. Condor. 1988, 90, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, L.E.; Henjum, G.M. Ecology of the Great Gray Owl. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR 265. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR: USA. 1990; pp. 39. [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, H.; Estafiev, A.A.; Kotchanov, S.K. Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa. In The EBBC Atlas of European Breeding Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance; Hagemeijer, E.J.M., Blair, M.T., Eds.; T&AD Poyser: London, UK, 1997; pp. 414–415. [Google Scholar]

- Sulkava, S.; Kuhtala, K. . The Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa) in the changing forest environment of northern Europe. J. Raptor Res. 1997, 31, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson, O. Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa. In Methods of Research and Protection of Owls; Mikusek, R., Ed.; FWIE: Kraków, Poland, 2005; pp. 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Chodkiewicz, T.; Woźniak, B. Great Grey Owl Strix nebulosa – a new breeding species in Poland. Ornis Pol. 2011, 52, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, R.; Stefansson, O. Life span, dispersal and age of nesting Great Grey Owls Strix nebulosa lapponica in Sweden. Ornis Svec. 2016, 26, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, E.L.; Duncan, R.J. Great Gray Owl (Strix nebulosa), version 1.0. In Birds of the World; Billerman, S.M., Ed.; Cornell Lab of Ornithology: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślak, M.; Kwieciński, Z. Moult and Breeding of Captive Northern Hawk Owls Surnia ulula. Ardea. 2009, 97, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, M.J.; Bentley, G.E. Stress, captivity, and reproduction in a wild bird species. Horm Behav. 2014, 66, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyahi, S.; Björklund, M.; Mateos-Gonzalez, F.; Sena, J.C. Personality and urbanization: behavioural traits and DRD4 SNP830 polymorphisms in great tits in Barcelona city. J. Ethol. 2017, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwieciński, Z.; Tryjanowski, P.; Zduniak, P. Intersexual patterns of the digestive tract and body size are opposed in a large bird. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Regan, H.J; Kitchener, A.C. The effects of captivity on the morphology of captive, domesticated and feral mammals. Mammal Rev. 2005, 35, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwieciński, Z.; Tryjanowski, P. Differences in digestive efficiency of the white stork Ciconia ciconia under experimental conditions. Folia Biol. 2009, 57, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herborn, K.A.; Macleod, R.; Miles, W.T.S.; Schofield, A.N.B.; Alexander, L; Arnold, K.E. Personality in captivity reflects personality in the wild. Animal Behav. 2010, 79, 835–843. [CrossRef]

- Rosin, M.Z.; Kwieciński, Z. Digestibility of prey by the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) under experimental conditions. Ornis Fenn. 2011, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelier, F.; Parenteau, C.; Trouve, C.; Angelier, N. Does the stress response predict the ability of wild birds to adjust to short-term captivity? A study of the rock pigeon (Columbia livia). R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwieciński, Z.; Rosin, Z.; M., Dylewski, Ł.; Skórka, P. Sexual differences in food preferences in the white stork: An experimental study. Sci. Nat. 2017, 104, 39. [CrossRef]

- Kwieciński, Z. , Krawczyk, A.; Ćwiertnia, P. Effect of ambient temperature on selected aspects of incubation behaviour in the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos under aviary conditions. Ornis Pol. 2009, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, M.; Zink, R.; Beissmann, H.; François Sarrazin, F.; Arlettaz, R. When to end releases in reintroduction programs: demographic rates and population viability analysis of bearded vultures in the Alps. J. App Ecol. 2009, 46, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknecht, R.; Jacobs, S.; Müller, J.; Zink, R.; Frey, H.; Solheim, R.; Vrezec, A.; Kristin, A.; Mihok, J.; Kergalve, I.; Saurola, P.; Kuehn, R. Phylogeographic analysis and genetic cluster recognition for the conservation of Ural Owls (Strix uralensis) in Europe. J Ornithol. 2013, 155, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeming, D.C.; Jarrett, N.S. Applications of incubation science to aviculture and conservation. In Nests, Eggs, and Incubation. Deeming, D.C, Reynolds, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger, J.; Lukaszewicz, E.; Kowalczyk, A.; Deeming, D.C.; Rzonca, Z. Nesting behaviour of Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) females kept in aviaries. Ornis Fenn. 2016, 93, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skutch, A.F. 1962. The constancy of incubation. Wilson Bull. 1962, 74, 115–152. [Google Scholar]

- Deeming, D.C. Behavior patterns during incubation. In Avian incubation: behaviour, environment, and evolution. Deeming, D.C, Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, C.B.S.; Davis, S.K. Incubation and nesting behaviour of the Chestnut-collared Longspur. J Ornithol. 2013, 154, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeming, C.D. Patterns and significance of egg turning. In Avian incubation: behaviour, environment, and evolution. Deeming, D.C, Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. (Ed.) Biostatistical analysis; Prantice Hall: New Jersey, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hałupka, K. Incubation feeding in Meadow Pipit Anhus pratensis affects female time budget. J. Avian Biol. 1994, 25, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloskowski, J. Prolonged incubation of unhatchable eggs in Red-necked Grebes (Podiceps grisegena). J. Ornithol. 1999, 140, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, J.S. Prolonged in Cubation by a Long-eared Owl. J. Field Ornithol. 1983, 54, 14. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/jfo/vol54/iss2/14.

- Margalida, A.A.; Arroya, B.E.; Bortolotti, G.R.; Bertran, J. Prolonged incubation in raptors: adaptive or nonadaptive behavior? J. Raptor Res. 2006, 40, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drent, R. Incubation. In Avian Biology Vol 5. Farner, D.S., King J.R, Eds.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1975; pp. 333–420. [Google Scholar]

- Wuczyński, A. Prolonged Incubation and Early Clutch Reduction of White Storks (Ciconia ciconia). The Wilson J. Ornithol. 2012, 124, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, S. Prolonged Incubation Behavior in Common Loons. Wilson Bull. 1982, 94, 20. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/wilson_bulletin/vol94/iss3/20.

- Holcomb, L.C. Prolonged incubation behaviour of Red-winged Blackbird incubating several egg sizes. Behaviour. 1970, 74-83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4533320.

- Afik, D.; Ward, D. Incubation of Dead Eggs. The Auk. 1989, 106, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Weeb, D.R. Thermal tolerance of avian embryos: A review. Condor. 1987, 89, 874–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstom, P.W. Incubation temperatures of Wilson’s Plovers and Killdeers. Condor. 1989, 91, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.; Rahn, H.; Parisi, P. 1980. Calories, water, lipid and yolk in avian eggs. Condor. 1980, 82, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P.D.; Wheelwright, N.T. Egg neglect in the Procellariiformes: reproductive adaptations in the Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel. Condor. 1979, 81, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeming, D. C et al. Factors affecting thermal insulation of songbird nests as measured using temperature loggers. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2020, 93, 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuRant, S.E.; Hopkins, W.A.; Hepp, G.R.; Walters, J.R. Ecological, evolutionary, and conservation implications of incubation temperature-dependent phenotypes in birds. Biol. Reviews, 2013, 88, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftorn, S. Incubating female passerines do not let the egg temperature fall below the ‘physiological zero temperature’ during their absences from the nest. Ornis Scan. 1988, 19, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.B.; Voss, M.A. Avian incubation patterns reflect temporal changes in developing clutches. PLOS ONE, 2013, 8, e65521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsman, D. Ageing and moult in Western Palearctic Hawk Owls Surnia u. ulula L. Ornis Fenn. 1980, 57, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, R.B. 1972. Mechanisms and control of moults. In Avian Biology Vol 2. Farner, D.S., King J.R, Eds.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1972; pp. 103–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, P. Flight-feather moult patterns and age in North American Owls. Monogr. Field Ornithol. 1997, 2. [Google Scholar]

| Behaviour | Infertile Eggs1 | Successful Hatching2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total Time of observation3 | 917:00:00 (100%) | 877:00:00 (100%) |

| Incubation Attentiveness | 822:55:42 (90%) | 769:14:12 (86%) |

| Egg Ventilation Time | 94:04:18 (10%) | 107:45:48 (14%) |

| In this: | ||

| Nest Departure Time | 13:53:19 (15%) | 19:31:52 (18%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).