1. Introduction

The Lesser Antillean Bullfinch (

Loxigilla noctis) is a tanager (family Thraupidae) endemic to the Lesser Antilles, with distinct subspecies across its range. The species is currently listed as Least Concern by the IUCN due to its stable population, adaptability to modified habitats, and widespread distribution across suitable Caribbean islands [

3].

L. n. dominicana, the subspecies occurring in Guadeloupe and Dominica, represents one of nine recognized subspecies, each showing subtle morphological variation while maintaining consistent ecological traits. The species is a widespread island tanager that frequently exploits human-modified habitats, yet quantitative breeding data remain sparse.

A recent St Lucia note [

1] described nest building over eight days for a single pair, with materials and courtship elements recorded during construction; however, it did not provide a full “first material → first egg → hatch → fledge” timeline or quantitative microsite architecture on human-made structures. Regional works [

2,

3] summarize clutch size and phase durations, but lack site-scale measurements. A complete, photo-anchored timeline and dimensional nest measurements are presented for suburban Guadeloupe, adding quantitative evidence from human structures. While this study is limited to intensive monitoring of two pairs, to our knowledge it represents the first continuous photographic documentation of complete breeding cycles for

L. noctis. These are presented as detailed case studies that establish baseline data and methodological approaches for future population-level research. The depth of observation (daily documentation over 150+ days per pair) provides novel insights that complement broader but less detailed survey approaches typically used in tropical ornithology.

Figure 1.

Lesser Antillean Bullfinches (L. noctis dominicana)—Pair A.

Figure 1.

Lesser Antillean Bullfinches (L. noctis dominicana)—Pair A.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study System and Focal Pairs

Observations were made in Les Abymes, suburban Guadeloupe, coordinates 16.229011, -61.522544 (subspecies

L. noctis dominicana). This case study focused on intensive monitoring of two focal pairs (Pair A and Pair B) selected based on nest accessibility for camera placement and minimal disturbance potential. Additional pairs (C–E) occurred nearby and provided supplementary observations but were not systematically monitored with cameras. While the sample size limits population-level inferences, the continuous monitoring approach enabled unprecedented documentation of complete breeding cycles. Individuals were not banded; identification relied on plumage nuances, behavior, and consistent territories.

Figure 2.

A) Map of study area with marked pairs territories (A, B and C) and nest positions (x); B) Outside view of the area; C) Pair A territory and prime feeding area; D) Pair A nesting area and overlap with Pair B’s territory; E) Pair B territory with the female present.

Figure 2.

A) Map of study area with marked pairs territories (A, B and C) and nest positions (x); B) Outside view of the area; C) Pair A territory and prime feeding area; D) Pair A nesting area and overlap with Pair B’s territory; E) Pair B territory with the female present.

2.2. Documentation

Mounted camera GoPro Session 4 was used at Pair A’s nest. Panasonic TZ80 and Samsung Galaxy S9 Plus were used for regular photos and video clips for Pairs A and B. Microsite descriptions include human-made niches such as: an empty wall lamp box, a broken stair lamp, selected for base support and side cover. Individual identification relied on a combination of morphological and behavioral markers: (1) subtle plumage variations including extent of rufous coloration in males and distinctive feather patterns; (2) behavioral characteristics including specific perch preferences, approach routes to nests, and vocalization patterns; (3) consistent territory boundaries maintained throughout the study period. Pair A male temporarily exhibited a missing tail feather that aided identification during that period, though identification was primarily based on consistent territory and behavioral patterns, while Pair B female showed consistent presence of lighter feathers on the left side of her face. These individual markers were documented and verified across multiple observation sessions to ensure consistent identification.

2.3. Observation Effort and Environmental Conditions

Total observation effort exceeded 1000 hours across the specific for this study period (November 2019–September 2020), with daily monitoring sessions conducted between 05:30-18:30, during morning and evening peak activity periods. Focal observations were supplemented with opportunistic monitoring throughout daylight hours. The study period encompassed the transition from dry season (December-May) to wet season (June-September) in Guadeloupe’s tropical climate. Based on regional climate data for Les Abymes, conditions during the main breeding period included: March-April (nest building phase) with mean temperatures of 26-27°C, relative humidity 74-76%, and monthly rainfall of 53-97 mm; May-June (incubation/early nestling) with temperatures of 27-29°C, humidity 76-78%, and rainfall increasing to 108-134 mm; July-August (fledgling phase) with temperatures of 29-31°C, humidity 78-81%, and rainfall of 105-147 mm. The dry season conditions during territory establishment and nest construction potentially facilitated continuous observation and camera operation, while increased precipitation during late nestling and post-fledgling periods may have influenced parental provisioning patterns and fledgling development.

2.4. Milestones and Timing

From field notes were extracted: time of establishing a territory, time of formation of pair, time of prospecting nest sites, first visible transport of material to chosen nest site and end of fledgling care. From media timestamps were extracted: (i) “structural closure” (globular dome complete with side entrance); (ii) first egg date; (iii) last egg date; (iv) clutch completion; (v) hatch dates; (vi) fledge dates. Phase durations were calculated as:

Build duration = date(structural closure)—date(first material)

Incubation = date(first hatch)—date(last egg laid)

Nestling = date(fledge)—date(first hatch)

2.5. Behavioral Observation Protocols

Observations were conducted daily to establish precise timing of breeding phases and document nest construction progress. Daily morning (05:30-09:00) and evening (15:00-18:30) observations were supplemented with regular observations throughout daylight hours, totaling over 1000 hours of observation effort across the study period. For establishing breeding chronology, were recorded: first appearance of specific birds in the territory, first sign of pair formation, first observation of prospecting nest sites (browsing suitable places with nest material in beak), first observation of integrating transported nest material, completion of nest structure (dome closure with formed entrance), onset of incubation (continuous nest attendance), hatching, last day female brooding on nestling, fledgling events (emergence from nest), last seen fledgling close to parents begging and tolerated, last appearance of fledgling in the vicinity of the observed space. The mounted camera at Pair A’s nest provided verification of these transitions through regular still image extraction. Construction progress was documented regularly to track structural stages: platform formation, wall building and dome completion.

Disturbance was minimized through: (1) camera installations during pair absence, completed in <1 minute; (2) observation distances of 5-50 m using binoculars and superzoom camera. Neither focal pair showed signs of disturbance-related disruption to their breeding cycle following equipment installation or during regular monitoring, which was facilitated by the species exceptional natural tameness.

2.6. Microsite Measurements

Dimensions were measured directly on the nests during the process and after being abandoned, using measuring tape. Reported metrics: nest height above ground (m), external width/height (cm), entrance diameter (cm), wall thickness (cm). Materials were identified visually (grass, twigs, leaves, cotton fibers).

2.7. Data Analysis and Reproducibility

Due to the intensive case study design (n=2 focal pairs), analyses were descriptive rather than statistical. Phase durations are presented as observed ranges to indicate individual variation. All temporal data were cross-validated between field notes and timestamped media to ensure accuracy (±1 day resolution for some of the key transitions). Because Pair A provides the most complete record (>600 hours of observation, continuous video and photographic coverage), Pair B is presented as partial replication (>300 hours, intermittent video and photographic coverage). Observational effort per phase was: territories establishment and pair formation (>400 hours), nest building (~100 hours), incubation (~200 hours), nestling (~200 hours), post-fledgling (>100 hours). The large number of observation hours was possible because of the coinciding COVID-19 lock-down on the island of Guadeloupe and the following closure of many businesses.

3. Results

3.1. Nest Architecture and Microsite Use on Human-Made Structures

All nests observed in the focal area, were placed in sheltered, semi-enclosed human structures providing base support, lateral cover and partial overhead cover (eaves, lamp housings), consistent with anti-predator microsite selection. Pairs also incorporated anthropogenic fibers (cotton/thread) into dome and wall elements.

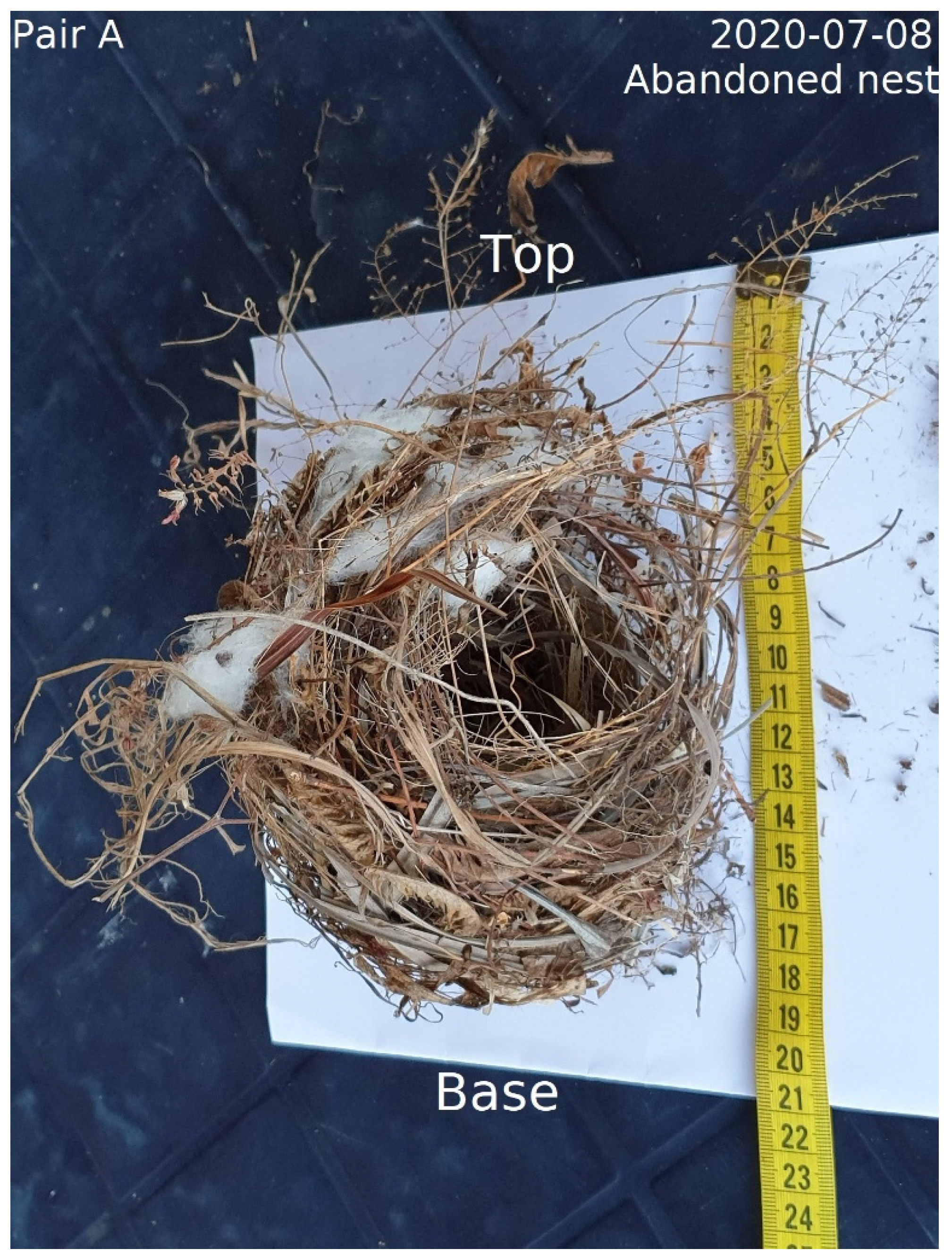

3.1.1. Measured Dimensions

Pair A—Height ~8 m from ground and ~2 m from the level 3 floor of the house; external width 13 cm; external height 17 cm; entrance diameter 5 cm; wall thickness 4 cm; materials: dry grass, small twigs, dry leaves, cotton pieces; globular dome with distinct lateral entrance. Notable is 5 cm infill made of dry grass below the nest during the first 3 days of the construction; the nest itself sits on top of the infill and it is not strongly woven into it.

Figure 3.

Pair A abandoned nest with measuring tape.

Figure 3.

Pair A abandoned nest with measuring tape.

Pair B—Height ~5 m from the ground of the house; external width 16 cm; external height 13 cm; entrance 6 cm; wall thickness 5 cm; nest placed on top an exterior lamp on a stairwell on the remains of an abandoned nest; difficult access for terrestrial predators.

3.1.2. Material Selection and Structural Composition

Both nests exhibited a consistent gradient in material selection corresponding to structural requirements. The foundation and outer walls incorporated coarser materials (stems 2-3 mm diameter, rigid twigs up to 10 cm length), providing structural integrity. Wall construction progressed inward with increasingly fine materials, with the innermost surface composed of tightly woven fine grass stems (<1 mm diameter). No distinct lining materials were observed; instead, the interior showed neat, dense weaving of the finest grass stems available, creating a smooth surface. Cotton and cotton-like synthetic fibers were concentrated on the dome exterior and upper wall portions (comprising approximately 15-20% of visible external surface area), suggesting a weatherproofing function rather than structural support, however this is only a hypothesis. These materials were interwoven with the grass framework, but not incorporated into the interior surfaces. The white coloration of these fibers may also provide thermal benefits by reflecting solar radiation. The selective placement of cotton-like materials on rain-exposed surfaces, suggests waterproofing.

Table 1.

Nest architecture and microsite metrics.

Table 1.

Nest architecture and microsite metrics.

| Metric |

Pair A |

Pair B |

Measurement method |

Notes |

| Microsite |

Under eaves / wall lamp housing |

Over stair lamp housing |

- |

Semi-enclosed; overhead and lateral cover |

| Height (m) |

8 |

5 |

measuring tape, ±0.25 m |

Measured1

|

| External width (cm) |

13 |

16 |

measuring tape, ±0.5 cm |

Completed dome |

| External height (cm) |

17 |

13 |

measuring tape, ±0.5 cm |

Measured1

|

| Entrance diam. (cm) |

5 |

6 |

measuring tape, ±0.5 cm |

Lateral entrance |

| Wall thickness (cm) |

4 |

5 |

measuring tape, ±0.5 cm |

Measured2

|

| Principal materials |

grass, twigs, leaves, cotton |

grass, twigs, leaves, cotton |

visual assessment |

Anthropogenic fibres evident |

| Material gradient |

Coarse outside → finer inside |

Coarse outside → finer inside |

Visual assessment |

Consistent pattern |

| Cotton fiber location |

Upper part (10-15%) |

Dome and walls (<10%) |

Visual estimate |

Probably ext. weatherproofing |

| Interior lining |

None (fine grass woven) |

None (fine grass woven) |

Direct observation |

Smooth woven surface |

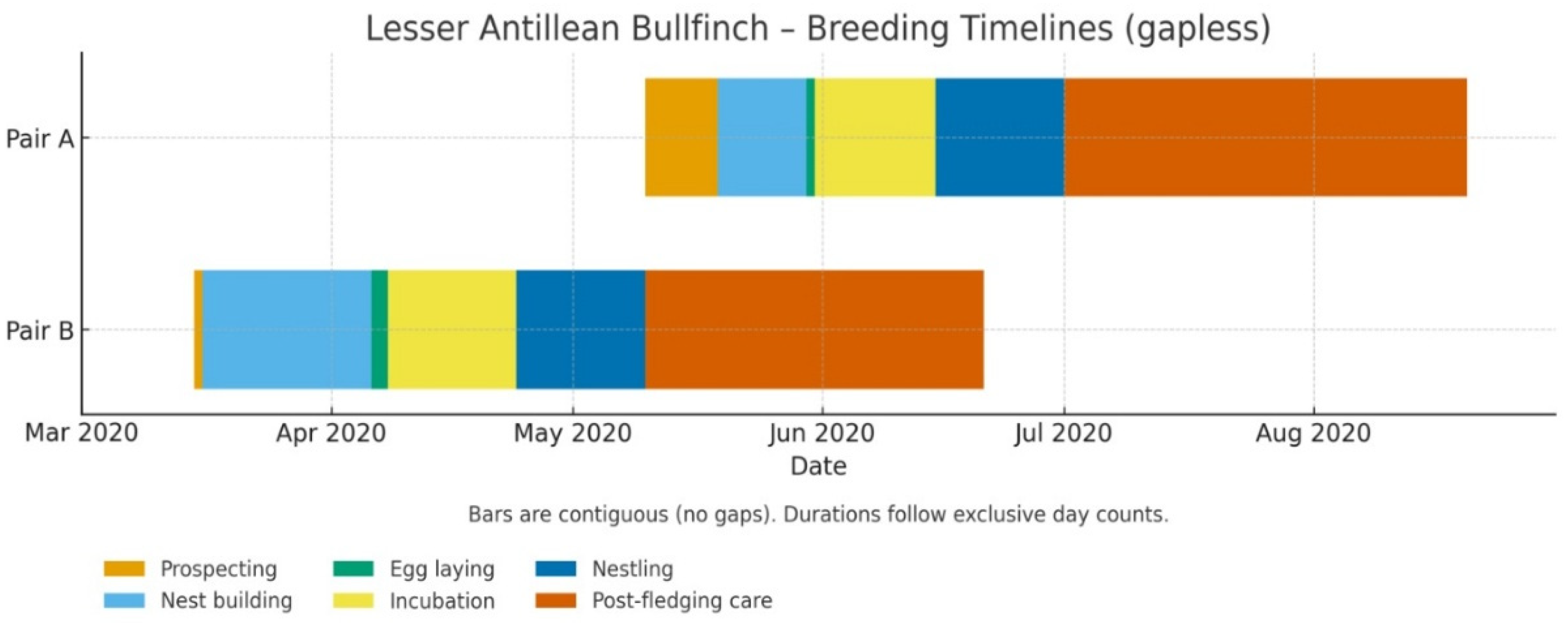

3.2. Construction Tempo and Complete Breeding Timeline

The intensive monitoring of our two focal pairs revealed both consistent patterns and notable individual variation in breeding phenology. Nest construction lasted 10 days for Pair A (19-29 May 2020) and 21 days for Pair B (16 Mar-6 Apr 2020). Egg-laying occurred over 2-3 days (Pair A: 2 eggs; Pair B: 3 eggs). Incubation was 15-16 days, and nestlings remained 16 days before fledging; females brooded up to ~6 days post-hatch. Post-fledging care persisted for ~6-7 weeks. The complete, date-resolved timeline is provided in

Table 2.

Figure 4.

Phase-resolved breeding timeline; bars are contiguous (exclusive day counts). Single-day phases are rendered at 1-day width for visibility.

Figure 4.

Phase-resolved breeding timeline; bars are contiguous (exclusive day counts). Single-day phases are rendered at 1-day width for visibility.

Figure 5.

Photo sequence of selected stills of Pair A breeding timeline: A) Nest building at early stage; B) Male brings and weave nest material; C) First egg; D) Male feeding brooding female; E) Hatching; F) Female brooding on nestlings; G) Male feeding nestling; H) Fledging.

Figure 5.

Photo sequence of selected stills of Pair A breeding timeline: A) Nest building at early stage; B) Male brings and weave nest material; C) First egg; D) Male feeding brooding female; E) Hatching; F) Female brooding on nestlings; G) Male feeding nestling; H) Fledging.

Figure 6.

Photo sequence of selected stills of Pair B breeding timeline. A) Nest in process of buildings; B) First hatchling; C) Nestling fed by the female; D) Fledging day 1.

Figure 6.

Photo sequence of selected stills of Pair B breeding timeline. A) Nest in process of buildings; B) First hatchling; C) Nestling fed by the female; D) Fledging day 1.

3.2.1. Breeding Disruptions and Outcomes

Both focal pairs experienced disruptions during breeding, though only one affected reproductive success. Pair B suffered partial brood reduction when one of two 8-day-old nestlings was depredated by Gray Kingbird (Tyrannus dominicensis) during parental absence. The parents continued provisioning the remaining nestling without observable change in attendance pattern, and this individual fledged successfully on schedule (day 16). Pair A experienced a non-fatal American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) attack on the male early in establishing its territory, resulting in temporary avoidance of the territory by all Lesser Antillean Bulfinches in the vicinity for approximately 3-4 days. Territorial defense was observed throughout the study, with Pair A maintaining the largest territory including the prime feeding area and actively excluding Pairs B and C from overlapping areas, particularly during territory establishment, nest construction, early incubation phases and later while present on their territory.

3.2.2. Arthropod Infestations and Fledging Timing

Both nests experienced ant infestations during the late nestling phase. In Pair B, ant activity intensified on days 14-15, causing visible nestling distress and possible premature fledging attempt (unable to sustain horizontal flight). The nestling was returned to the nest by a resident of the house and successfully fledged the following day (day 16), though flight capacity remained limited. Pair A’s nest infestation was mitigated by routine insecticide application to the building structure by the landlord (day 12), after which the nestlings showed reduced agitation and fledged on day 16 with competent flight ability. These infestations potentially influenced the observed 16-day nestling period in both nests.

4. Discussion

4.1. Novel Contributions to Caribbean Ornithology

This study provides the first complete photographic documentation of

L. noctis dominicana breeding biology with day-level resolution, extending from territory establishment through post-fledging care completion. While previous work from St Lucia documented an 8-day construction period for

L. n. sclateri [

1], our continuous monitoring reveals substantial intraspecific variation (10-21 days) and provides the first quantitative nest architecture measurements for the species on human-made substrates. The 15-16 day incubation period exceeds previously reported values of 13-14 days [

2] and warrants further investigation. This discrepancy may reflect either methodological limitations in earlier studies or genuine behavioral plasticity (lag of incubation start or onset of egg development start) in response to disturbance, urban environmental conditions or climatic variations. The complete timeline spanning approximately 150-210 days from pair formation to full independence of which approximately 100 day from nest prospecting to full independence represents a significant advance in understanding the reproductive investment of this endemic Caribbean thraupid.

4.2. Comparative Breeding Biology Within Thraupidae

The incubation values, while exceeding some published data for this species [

2], remain within the range observed for other small-bodied thraupids. while the nestling period (16 days) aligns with the one stated in the same source [

2]. The 10-day duration reported in [

3] appears erroneous, as nestlings at this stage have only developing pin-feathers and lack the mobility required for fledging. However, our values remain within the range observed for other small-bodied thraupids, suggesting possible behavior or methodological variation rather than anomalous development.. For comparison, the related slightly smaller Black-faced Grassquit (

Melanospiza bicolor) shows shorter incubation (12-14 days) and nestling periods (10-13 days) [

2], while the Bananaquit (

Coereba flaveola) exhibits comparable total durations, but different nest architecture [

2]. The globular dome construction with lateral entrance may represents a convergent strategy among tropical passerines, potentially offering superior protection against both precipitation and aerial predators compared to open-cup nests. The substantial wall thickness (4-5 cm) exceeds that reported for many similar-sized species, possibly reflecting adaptation to exposed microsite conditions.

4.3. Urban Nesting Ecology and Behavioral Plasticity

The exclusive use of human-made structures in our study area demonstrates remarkable ecological flexibility in L. noctis dominicana. This behavioral plasticity parallels urban adaptation patterns documented in other Caribbean endemics, though few species show such high degree of reliance on artificial substrates. The consistent selection of lamp housings and wall fixtures at 5-8 m height suggests these structures may offer optimal trade-offs between predator avoidance and microclimate regulation. The incorporation of anthropogenic materials (cotton fibers, synthetic threads) into nest construction further indicates adaptive exploitation of novel resources in urban environments.

The observed height placement (5-8 m) exceeds typical natural nest heights reported for the species (2-5 m) but still falls in the stated range of 1-10 m [

2,

3], potentially reflecting: (1) reduced terrestrial predator pressure in urban settings by the higher placement, (2) availability of suitable attachment points on buildings, or (3) avoidance of human disturbance at lower levels. The semi-enclosed nature of selected microsites (lamp housings, eave corners) provides overhead and lateral protection typically achieved through vegetation cover in natural habitats. The observed gradient in material selection, from coarse structural elements externally to fine interwoven grasses internally, parallels construction patterns in other dome-nesting species [

2] with some variations.

The extended incubation period observed in our urban study site may reflect behavioral adjustments to human-related disturbances, with incubating adults potentially spending more time off the nest due to human activity.

While human structures provide certain advantages, they also present novel challenges including arthropod infestations facilitated by the stable microclimate and protection from rain that benefits both birds and invertebrates. The observed ant infestations affecting both nests suggest that the 16-day nestling period may represent a compromise between development needs and mounting pressure from ectoparasites or commensal arthropods in these protected microsites.

The 6-7 week post-fledging care period, may have been artificially prolonged by increased human traffic and activities in the area (due to the COVID-19 lockdown coming to end), thereby delaying the initiation of subsequent breeding cycles.. This prolonged period, while energetically costly, may be facilitated by reliable food resources in suburban environments. Urban areas often provide consistent food sources compared to agricultural areas. The extended parental care could enhance juvenile survival during the critical transition to independence, potentially offsetting any costs associated with urban nesting.

4.4. Microclimate Considerations and Potential Fitness Benefits

Human structures may provide superior microclimatic conditions compared to natural sites, particularly in tropical urban heat islands. The thermal mass of concrete and metal fixtures could buffer against temperature extremes, while overhead coverage from eaves and lamp housings offers protection from intense midday radiation and tropical downpours. The measured nest dimensions, particularly the 4-5 cm wall thickness, suggest substantial insulation capacity. Future studies should incorporate temperature data logging to quantify these potential thermoregulatory advantages.

Despite the secluded nest placement, partial predation was documented, with Gray Kingbird successfully accessing Pair B’s nest during parental absence, suggesting that even human structures do not eliminate predation risk, though the successful fledging of the remaining nestling indicates resilience to partial brood loss.

4.5. Conservation Implications

These findings have important implications for urban biodiversity conservation in the Caribbean. The successful exploitation of human structures by L. noctis dominicana suggests that appropriately designed urban environments could support breeding populations of endemic species. However, this adaptation raises several conservation considerations: (1) dependency on specific architectural features that may change with building modernization, (2) potential ecological traps if structures are modified during breeding, and (3) unknown long-term fitness consequences of urban nesting.

Although L. noctis dominicana maintains relatively stable populations and Least Concern status, understanding its breeding ecology in urban environments has broader implications for Caribbean endemic avifauna facing increasing urbanization. The successful exploitation of human structures documented here suggests that urban-adaptable species may serve as indicator species for urban habitat quality in the Lesser Antilles.

The variation in construction duration (10 vs 21 days) between pairs might reflect individual experience, resource availability, or disturbance levels, highlighting the need for understanding factors influencing breeding success in urban environments. Conservation strategies should consider maintaining suitable nesting structures during urban development and potentially incorporating nest-friendly architectural features in new construction.

4.6. Methodological Advances, Study Rationale, Limitations, and Future Directions

The successful deployment of mounted cameras for continuous breeding monitoring represents a methodological advance for tropical ornithology, where high humidity and temperature traditionally challenge electronic equipment longevity. This approach enables precise phenological documentation while minimizing disturbance, critical for urban-nesting species subject to multiple stressors.

Future research priorities should include: (1) expanding sample sizes across urban-rural gradients to assess habitat-specific breeding parameters, (2) quantifying nest success rates and identifying primary failure causes, (3) conducting multi-season monitoring to detect temporal patterns and site fidelity, (4) incorporating genetic analyses to assess population connectivity between urban and natural habitats, (5) measuring microclimatic variables to test thermoregulation hypotheses, and (6) comparing breeding investment and success between subspecies across the Lesser Antilles.

The observed territorial interactions and predation events documented here warrant detailed investigation of social dynamics and predator-prey relationships in urban-nesting populations.

While our sample size of two continuously monitored pairs limits population-level inferences, the depth of observation (daily field notes and regular video and photographic documentation over complete breeding cycles) provides unprecedented detail for this species. The consistent patterns in incubation and nestling duration, despite variation in construction tempo, suggest our core findings are representative. The observations of additional territorial pairs (C-E), though not systematically monitored with video and photo equipment, supports the generality of human-structure nesting in this population. Future studies should aim for larger sample sizes while maintaining similar observation intensity to balance breadth with detail.

This study deliberately prioritized observation depth over sample breadth, following a case study approach that has proven valuable in establishing baseline natural history data for understudied species. The continuous daily monitoring of two pairs over complete breeding cycles (>300 combined observation days) provides temporal resolution unavailable in traditional survey approaches. While our sample size precludes statistical analyses and population-level generalizations, the detailed chronology and measurements establish critical baseline data for this Caribbean endemic. The consistent patterns observed between pairs for incubation (15-16 days) and nestling periods (16 days), despite variation in construction duration, suggest these parameters may be relatively fixed species traits. The variations in building tempo (10 vs 21 days) and incubation (stated 13-14 [

2] vs 15-16 days) highlights the importance of individual-level monitoring to detect behavioral plasticity that would be masked in population averages. Despite these limitations, this study establishes a robust foundation for understanding

L. noctis dominicana breeding ecology in general and in human-modified landscapes, contributing essential natural history data for this adaptable Caribbean endemic. Future studies should build upon this foundational work with larger sample sizes while attempting to maintain similar observation intensity.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first video and photographically documented, day-resolution breeding chronology for L. noctis dominicana from territory establishment through post-fledging care completion, spanning approximately 4-5 months per breeding attempt. The quantitative nest architecture measurements (external dimensions: 13-16 cm width, 13-17 cm height; entrance: 5-6 cm; wall thickness: 4-5 cm) establish baseline morphometric data for this subspecies on human-made substrates. Our continuous monitoring approach revealed substantial intraspecific variation in construction duration (10 vs 21 days), while incubation (15-16 days) and nestling periods (16 days) showed greater consistency between pairs.

The exclusive use of human-made structures (lamp housings, wall fixtures) at heights of 5-8 m, combined with the incorporation of anthropogenic materials (cotton fibers) into nest construction, demonstrates remarkable behavioral plasticity in this species’ adaptation to suburban environments. The consistent selection of semi-enclosed microsites with overhead and lateral cover suggests these artificial substrates may provide comparable or superior protection to natural sites, with potential thermoregulatory advantages in tropical urban heat islands.

While limited to two focal pairs, this study establishes a methodological framework for future breeding biology research in the Lesser Antilles, where many endemic bird populations remain understudied. The successful application of mounted cameras for continuous monitoring proves feasible for tropical urban environments and could be expanded to examine fitness consequences of urban nesting, seasonal variation, and nest site fidelity. Our findings contribute essential natural history data for this Caribbean endemic, providing a foundation for comparative studies across the species’ range and informing urban biodiversity conservation strategies in the rapidly developing Caribbean region. Future multi-site, multi-season studies with larger sample sizes will be crucial to understand population-level patterns and the long-term viability of human-structure nesting in this adaptable thraupid.

Author Contributions

Todor Mishev: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No permitting was required for observational work at private residences; the study involved no capture, handling, or experimental manipulation of birds. Property-owner insecticide applications were routine building maintenance and were neither requested nor conducted by the author.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Prof. Dsc Dilian Georgiev (University of Plovdiv, Trakia University) for methodological advice and critical review of early manuscript drafts. Special thanks to Milena Lilova for assistance with daily monitoring, photographic documentation, field observations and English-language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marcuk, V.; de Boer, D. Note on the nest-building behaviour, socio-negative interactions and courtship display of the Lesser Antillean Bullfinch Loxigilla noctis sclateri in a suburban area of St Lucia. Biodivers. Obs. 2023, 13, 214–218. Available online: https://journals.uct.ac.za/index.php/BO/article/view/1342 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Benito-Espinal, É.; Hautcastel, P. Les oiseaux des Antilles et leur nid; PLB Éditions: Guadeloupe, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Buckmire, Zoya E. A.; Carter, Kenrith D. (2025). Lesser Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigilla noctis). Available online: https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/leabul1/cur/introduction (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Table 2.

Phase-resolved breeding timelines for L. noctis dominicana (exclusive day counts).

Table 2.

Phase-resolved breeding timelines for L. noctis dominicana (exclusive day counts).

| Phase |

Pair A |

Pair B |

| Start |

End |

Duration |

Start |

End |

Duration |

| Occupying territory |

~ Dec 2019 |

- |

- |

~ Mar 2019 |

- |

- |

| Couple formation start |

01 Apr 2020 |

- |

- |

20 Nov 2019 |

- |

- |

| First copulation observed |

15 May 2020 |

- |

- |

Not observed |

- |

- |

| Prospecting |

10 May 2020 |

18 May 2020 |

8 |

15 Mar 2020 |

15 Mar 2020 |

1 |

| Nest building |

19 May 2020 |

29 May 2020 |

10 |

16 Mar 2020 |

06 Apr 2020 |

21 |

| Egg laying |

30 May 2020 |

31 May 2020 |

2 |

06 Apr 2020 |

08 Apr 2020 |

3 |

| Incubation |

31 May 2020 |

15 Jun 2020 |

15 |

08 Apr 2020 |

24 Apr 2020 |

16 1

|

| Nestling |

15 Jun 2020 |

01 Jul 2020 |

16 |

24 Apr 2020 |

10May 2020 |

16 |

| Fledgling care |

01 Jul 2020 |

20 Aug 2020 |

~50 |

10May 2020 |

21 Jun 2020 |

~42 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).