1. Introduction

The relentless populational growth, combined with the improvements in life expectancy, promotes, worldwide range, an increasingly greater energy demand. The energy system, as it is currently, is fossil fuel-based, with about 80% of the world’s primary energy supply covered by this source [

1]. Fossil fuels, however, are not a renewable source, and geologists and petroleum engineers estimate that over 40% of the available petroleum reserves have already been used [

2]. In this scenario, finding new ways to produce energy is a critical issue. Moreover, the increase in energy demand is not the only challenge. As the evidence of the effects of global warming and climate change is overwhelming, the quality of energy as a clean, sustainable, and renewable source will be a priority as well.

Amidst the diverse alternatives that arise for new forms of clean energy, hydrogen stands out, since it has some advantages over other fuels. Some of the advantages can be listed: (a) it is simpler chemically than other fuels; (b) hydrogen combustion in engines or its uses in fuel cells does not release CO2 as a product, only water; (c) feedstock for hydrogen production is plentiful; (d) it can be produced with zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions with water electrolysis; (e) in the liquid form it has high lower heating value (LHV) of 120 MJ/kg, about 2.5 greater than gasoline; and (f) it can be used as chemical storage of electrical energy [

1,

3].

Due to the investments in technological advances, renewable and clean power plants like hydroelectric, wind power, and solar power plants are increasingly economically competitive [

4]. Nonetheless, some obstacles remain in the renewable electrical energy application. Firstly, some of the natural sources, like wind or sunlight, are not available continuously; thus, when lacking of means for clean energy production, the energy still has to be obtained from nonrenewable resources [

4]. To produce and store energy as much as possible during a certain period and use the storage when in need would be a solution, but it faces the impossibility of energy storage in electrical form. Despite physical and chemical ways of energy storage being available, electrical generating plants usually do not have a storage system and are submitted to a generation matching the energy demand [

5].

In this scenario, hydrogen as an energy carrier, produced by the electrolysis of water, has great prospects. Despite the initial gaseous form of the hydrogen produced, adding a hydrogen liquefaction after the electrolysis cycle would guarantee a low volume-consuming way to store energy in a high-energy content and low-weight form, considering the aforementioned liquid hydrogen LHV [

6]. The liquefaction of the hydrogen also ensures a more cost-effective way to transport hydrogen, since pipelines are not efficient in long-distance transportation [

7].

Nevertheless, liquid hydrogen has some economic drawbacks regarding the boil-off in storage and transportation, and liquefaction energy cost [

8]. The transportation and storage of hydrogen in liquid form suffer from the constant heat absorption from the environment, causing the hydrogen to evaporate, a phenomenon called “boil off”. Compared with liquefied natural gás (LNG), hydrogen has an 18 times lower heat of vaporization [

9], thus requiring special design vessels to prevent the boil-off, which can consume up to 40% of the hydrogen combustion energy [

10]. Recent and active studies have approached methods to mitigate hydrogen boil-off losses, and a revision of the three main methods employed, hydrogen compression, zero boil-off, and hydrogen reliquefaction, is made by Morales-Ospino, Celzard, and Fierro (2023) [

9]. Not only, hydrogen liquefaction is also a highly cost-intensive process, given that hydrogen is the second hardest gas to liquefy, with a liquefaction temperature of about 20 K at ambient pressure, and only having a greater liquefaction temperature than helium, whose boiling point is 4 K.

Furthermore, hydrogen liquefaction has another specificity regarding the hydrogen molecular property, which is the occurrence of two isomeric forms: ortho-hydrogen and para-hydrogen [

8]. The isomers differ by the nuclear spin: while ortho-hydrogen presents both protons with the same direction spins, implying a higher energy state, in the para form, hydrogen has protons with opposite spins and has a lower energy state [

11]. At ambient temperature, hydrogen is a mixture composed of about 75% ortho-hydrogen and 25% para-hydrogen (also known as normal hydrogen), but with a temperature decrease, the equilibrium shifts toward an increase in the para-hydrogen content. Since the ortho-para reaction heat is about 0.388 kcal/mol, overcoming the hydrogen evaporation heat of approximately 0.213 kcal/mol, the ortho-para conversion must be carried out in the cooling/liquefaction process; otherwise, the reaction heat of the posterior conversion would be enough to evaporate all the liquefied gas [

12]. The liquefiers, therefore, have ortho-para conversion systems, with appropriate catalysts, usually packaged inside the heat exchangers [

8], to favor the increase of para-hydrogen content and reduce storage losses [

13].

Historically, hydrogen liquefaction is a relatively new process, since it was first achieved only in 1898 by J. Dewar, overruling the previous “permanent gas” status of hydrogen [

14,

15]. Proven that hydrogen liquefaction was a possibility, the race for creating liquefaction cycles started. The Linde-Hampson cycle (with a precooling section), developed in 1895, and the Claude (or Simple Claude) cycle, developed in 1902, were the first systems able to liquefy hydrogen [

16], and since then, other cycles or variations, like Kapitza, Joule-Bryton, dual pressure Claude, pre-cooled Claude, pre-cooled mixed refrigerant cycles, among others, were designed to achieve a more efficient process. Despite those efforts, all existing and operating liquefaction plants still use versions of the pre-cooled Claude cycle and have not presented major improvements in the last 50 years [

7,

8].

Usually, the specific energy consumption (SEC) is the main parameter to compare cycle efficiency. While more classical cycles, such as Claude and Precooled Linde-Hampson, present an SEC of 27.8 kWh/kg

LH and 72.2 kWh/kg

LH [

17], respectively, actual operating plants like Paxair’s, in the United States, and Linde’s, in Germany, already achieved SEC in the range of 12 to 15 kWh/kg

LH [

12,

16], using a modification of the pre-cooled Claude cycle. Additionally, plenty of research has been published with new conceptual plants with more promising SEC. The WE-NET, a Japanese project that was proposed in 1993 to develop and establish the technology for a global hydrogen-based energy network [

18], indicates three conceptual liquefaction cycles, based on Claude, Helium Brayton, and Neon Brayton cycles that would be capable of reaching an SEC of 8.5

[

19]. Further, Quack (2002)[

20] proposed a cycle with two refrigeration systems: a propane refrigeration system, used for inter-compression cooling, and a Helium-Neon cycle for cryogenic cooling. An SEC of 7.0 kWh/kg

LH was obtained for large-scale hydrogen liquefaction with the consideration of hydrogen feed and storage pressure of 1 bar, and about 5.0

for hydrogen feed of 20 bar and storage at 3 bar [

20].

Furthermore, Valenti and Macchi (2008) [

21] proposed a liquefaction system with a Helium recuperative Joule-Brayton cycle and achieved an SEC of 5.04

, and found out that the majority of the exergy losses occur in the helium compression system, followed by the heat exchangers. The lower SEC for hydrogen liquefaction, 4.41

, is reported by Sadaghiani and Mehrpooya (2017), who developed a system combining two refrigeration systems. The first refrigeration cycle with a mixed refrigerant composed of methane, ethane, n-butane, hydrogen, nitrogen, propane, n-pentane, R-14, and ethylene, reduces the hydrogen temperature to -193 °C. The second refrigeration, with hydrogen, neon, and helium, achieved a hydrogen refrigeration to -253 °C [

22].

It is visible from the aforementioned studies that, compared with the thermodynamical ideal SEC for the hydrogen liquefaction of 3.92

[

23,

24], the conceptual plants already present a performance close to the ideal limit, and, therefore, there is not much more expectation for the development of concepts on new cycles [

12]. However, advances in technology for achieving the practical application of the new concepts are still needed. More about hydrogen liquefaction can be found in the review articles of Aasadnia and Mehrpooya (2018) and Krasae-in et al. (2010) [

12,

16].

Despite the rapid improvement in the conceptual plants, a significant amount of the studies focused on the development of new and conceptual designs and the determination of optimal conditions for achieving better efficiency to the detriment of a more complete analysis of real cycles performance in a wide range of operations conditions, which could provide a better understanding of these systems at a fundamental level. Some examples of analysis beyond the SEC value would be exergy destruction, exergy destruction distribution, the temperature profile in the heat exchangers, the influence of ortho-para conversion, and their behavior under different operating conditions. Yang et al. (2023) [

25], for example, compared Claude and Brayton cycles, which are the basis for most of the operating hydrogen liquefaction plants, using sensitivity analysis to optimize operating conditions and assessed both cycles regarding their SEC, refrigerant use, and exergy efficiency. The authors reported an SEC of 5.62 kWh/kg

LH and 5.87 kWh/kg

LH for the Claude and Brayton cycles, respectively. With regard to exergy efficiency, in the study, Claude was also more effective, with a 6.6% lower exergy destruction.

On the same path as the aforementioned study, in the present study, an analysis of other hydrogen liquefaction cycles, like Linde-Hampson, Single Mixed, and Dual Mixed refrigerants, is proposed.

3. Results and Discussion

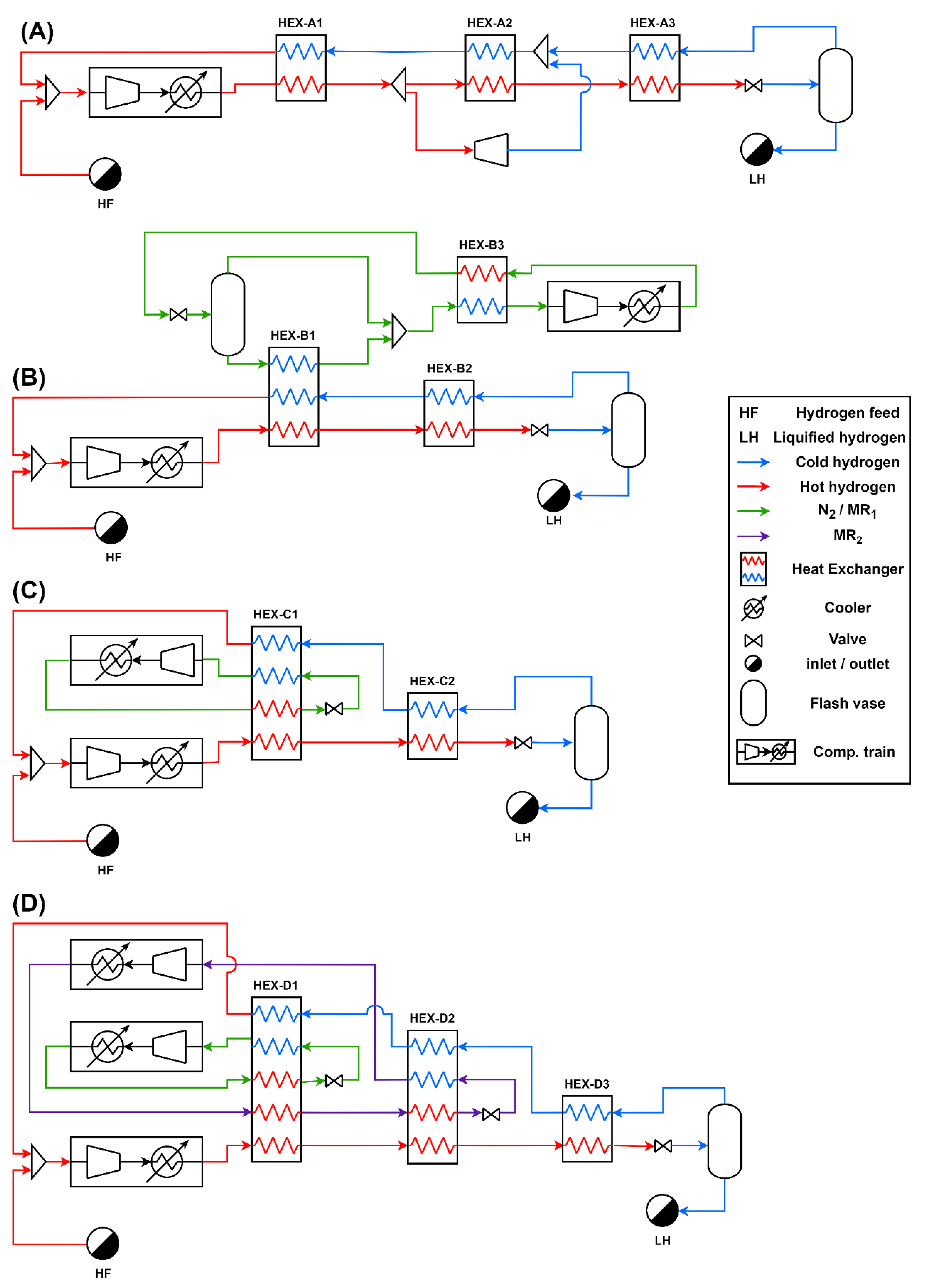

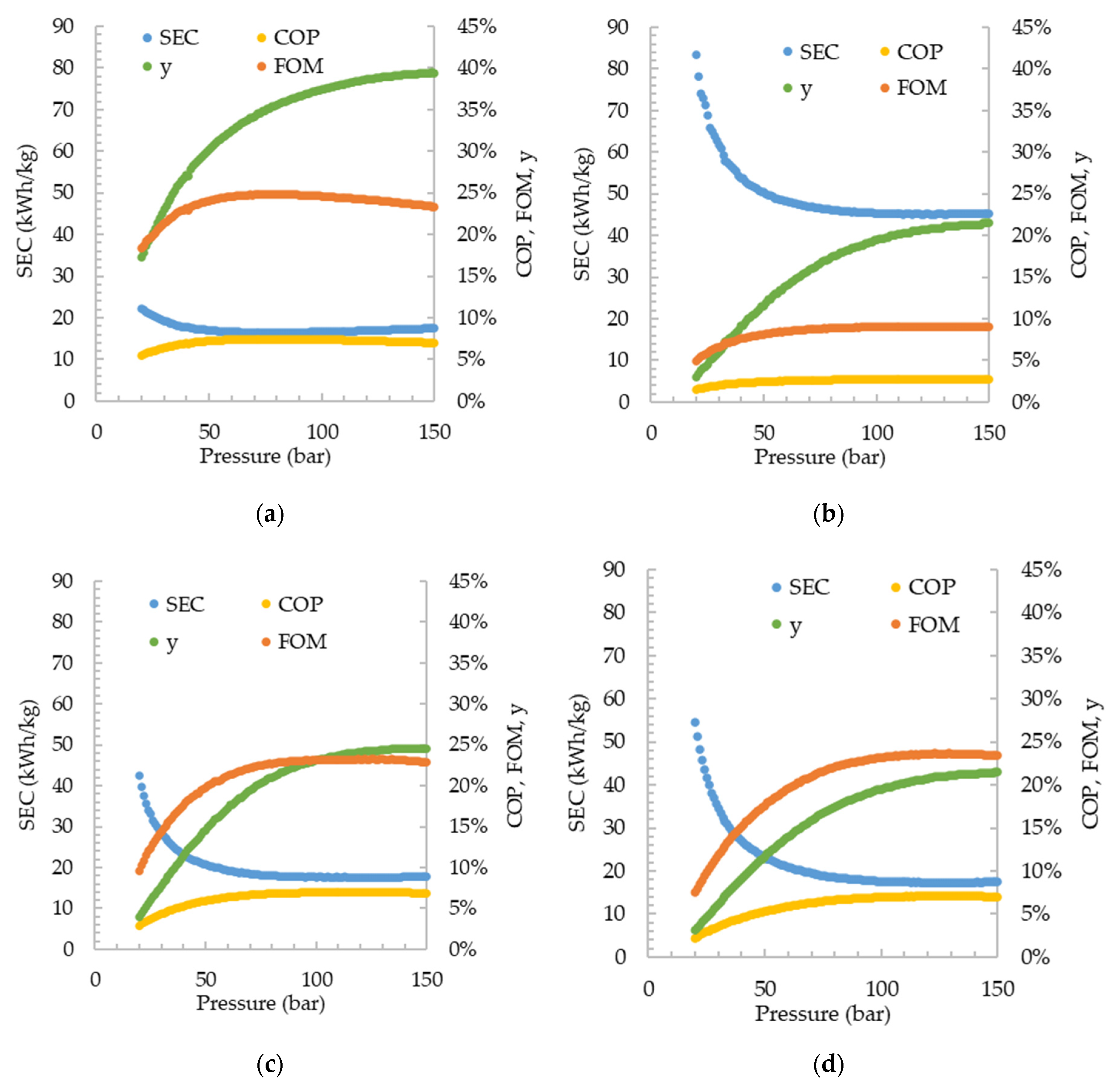

From the simulations carried out, the process efficiency indicators, SEC, COP, and FOM, as well as the fraction of liquefied hydrogen after expansion in the valve, are shown in

Figure 2. The pressure range for which the results were plotted varies between 20 to 150 bar with a 1 bar interval. Among the cycles, the Claude cycle presented the best energy efficiency, with a minimum SEC of 16.47 kWh/kg

LH, and a maximum FOM of 24.85%, when the high pressure of the cycle is 78 bar. Among the pre-cooled cycles, the DMR showed better results, with an SEC of 17.30 kWh/kg

LH, at 123 bar, followed by the SMR cycle, with an SEC of 17.58 kWh/kg

LH, at 125 bar, and finally the PLH with an SEC of 45.07 kWh/kg

LH, operating at 124 bar. Despite the different efficiencies, all cycles presented the same behavior regarding the increase in the high pressure, improving energy consumption up to a limit beyond which the increase in irreversibility implies greater exergy losses than facilitates liquefaction. For a comparison effect,

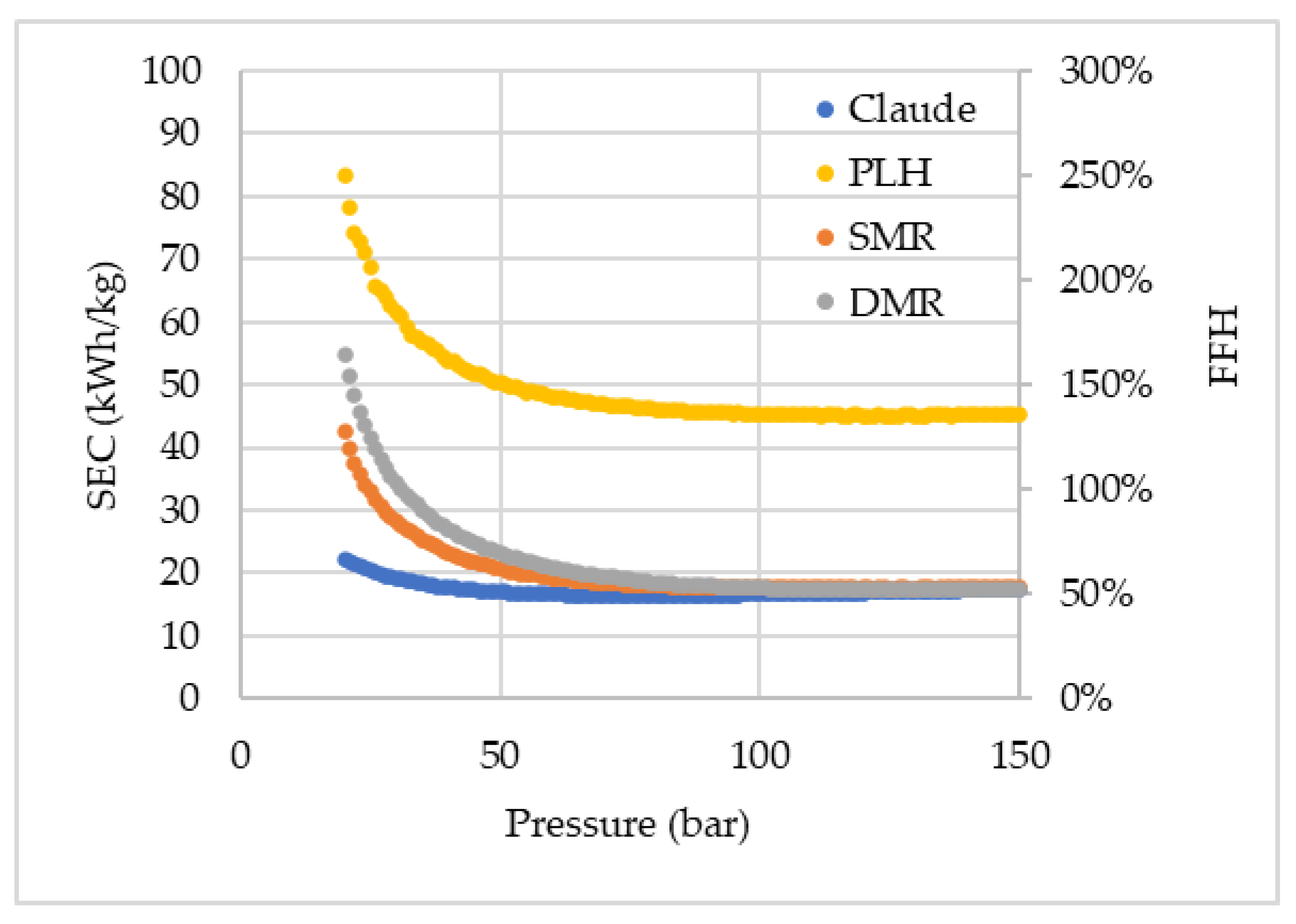

Figure 3 shows the SEC and the FFH of all simulated cycles, and only Claude, SMR (operating above 25 bar), and DMR (operating above 32 bar) cycles were found to exhibit FFH lower than 100%, i.e., presenting a lower energy cost for hydrogen liquefaction than hydrogen itself contains. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight that the FFH alone cannot provide enough information for evaluating the worthiness of the liquefaction cycle, being only a cycle efficiency indicator, as the SEC. Since liquefaction is an alternative for storing and transporting hydrogen, especially over long distances, its cost, therefore, should be compared to gas hydrogen transportation through pipelines, for example. In the graphs, no perfect tendency of the points is observed, which is caused by the recycle and adjust blocks, and even multi-current heat exchangers, which have a tolerance for the simulation’s convergence.

It can be noticed a significant superiority of the Claude cycle over the other cycles. This is essentially due to the presence of the expander, which always guarantees more effective cooling than the isenthalpic expansion in the valves. The expander makes the addition of a pre-cooling cycle unnecessary and concomitantly produces work that can be integrated and used in the process compression or other operations, and also reduces the net power consumption by the system. The SEC found (16.47 kWh/kgLH) even approaches the current SEC of operating hydrogen liquefaction plants (12-15 kWh/kgLH).

The SEC of the Claude cycle operated at a high pressure of 21 bar was 21.86 kW/kg

LH, which is significantly higher than the value reported by Yang et al. (2023) [

25] of 5.62 kW/kg

LH. The contrast in values is due to differences in the construction of the liquefaction cycle model. While those authors considered pre-cooling external to the hydrogen liquefaction line (using nitrogen), in the present work, the Claude cycle did not consider the use of a refrigerant. Furthermore, the designs differ regarding the number of compressors and expanders applied in series, as well as the number of splits of the hydrogen stream for temperature reduction in expanders. In addition, those authors assumed that the hydrogen supplied to the cycle would be at a pressure of 21 bar, compared to the ambient pressure (1 bar) considered in this work. Considering a hydrogen feed pressure of 21 bar to the cycle, the SEC value would be 20.40 kW/kg

LH, and the reduction would progress with the increase of the high pressure of the cycle, since a greater fraction of the hydrogen is liquefied, and therefore a greater quantity of high-pressure hydrogen would be fed to the cycle and not pressurized internally.

The lower SEC obtained in the mixed refrigerants cycles in comparison with PLH, is because, using a non-pure refrigerant, the saturation temperature of the refrigerant at the lower pressure level of the cycle will be lower than the lowest saturation temperature between the components of the refrigerant, that is, nitrogen saturation temperature, as is the case in PLH. Therefore, much lower refrigerant compression is required in the SMR and DMR cycles, as defined in

Table 2.

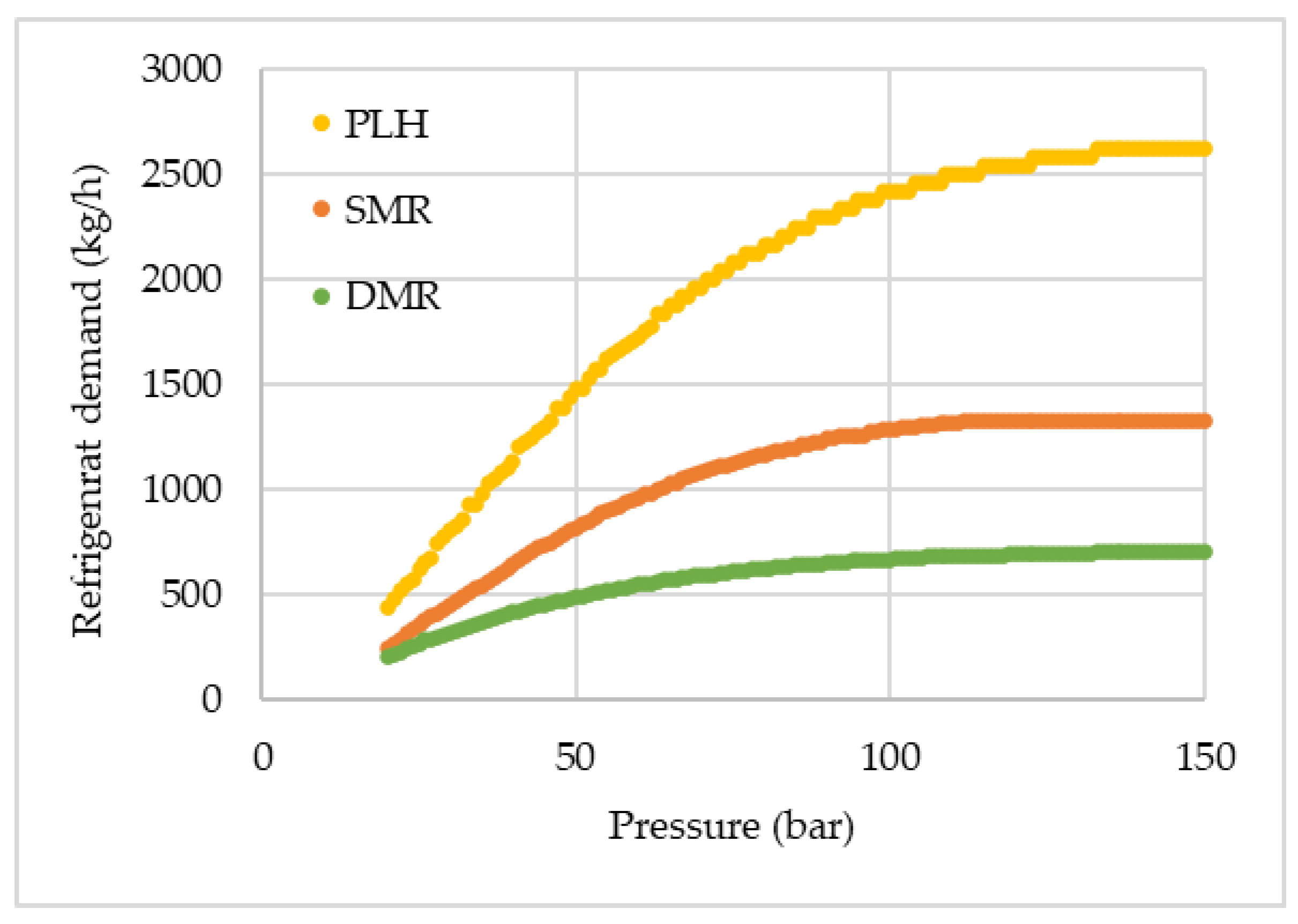

The refrigerant demands for each pre-cooled cycle are presented in

Figure 4. An increase in the demand can be verified as the pressure increases, proportionally to the liquefied hydrogen fraction. With the reduction of the non-liquefied hydrogen, the amount of heat that can be removed by the recycled hydrogen also decreases, and the cooling, previously provided by the cold hydrogen, has to be supplied by the additional refrigerant. For the DMR cycle, since WMR and CMR were set to have the same mass flow rate, only one data set is shown. Considering both WMR and CMR, the total refrigerant demand in SMR and DMR is almost identical, while in PLH, the nitrogen needed for pre-cooling is close to two times the amount needed in the other two pre-cooled cycles.

Furthermore, in terms of exergy, the SMR system has a significant advantage over the PLH.

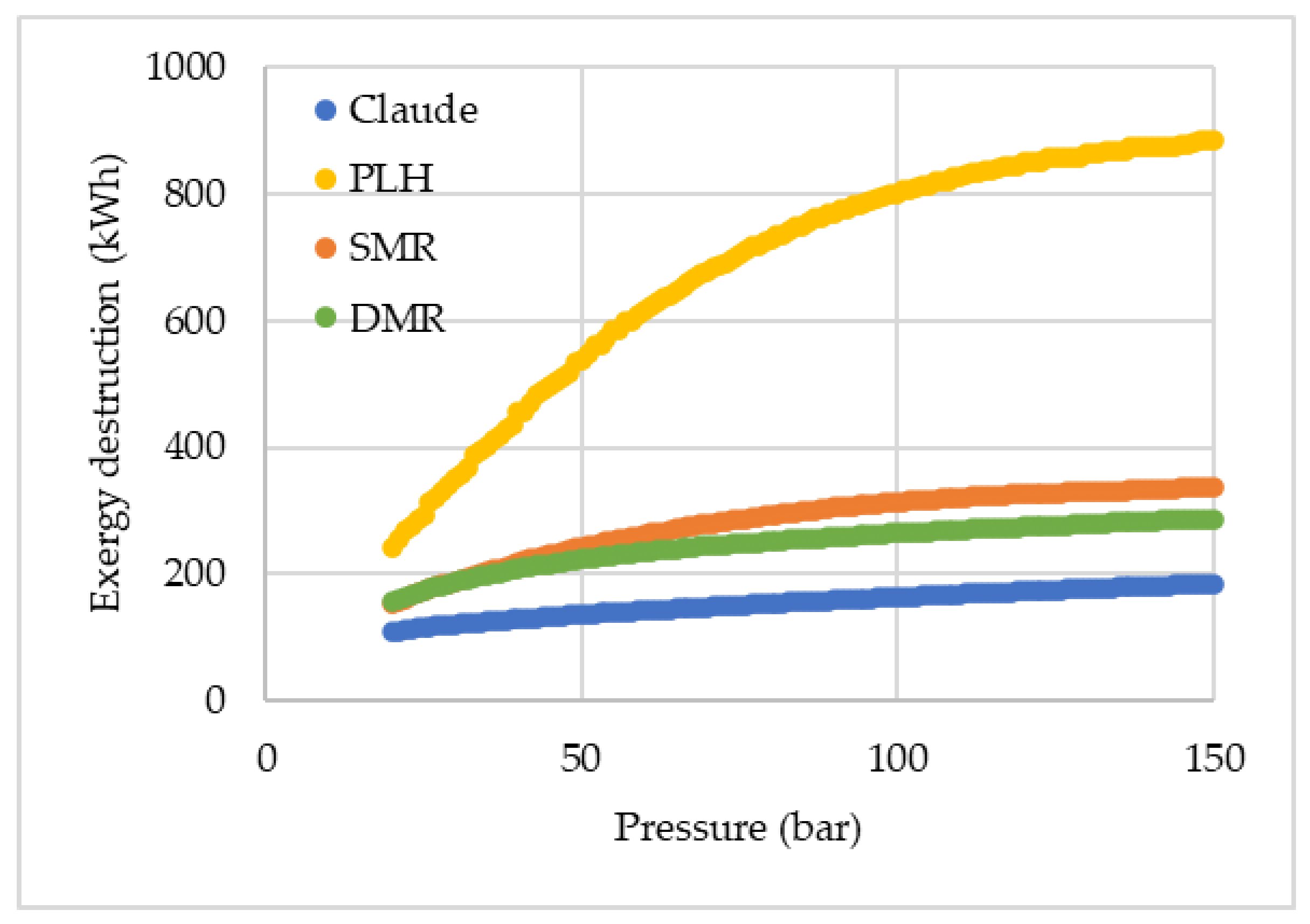

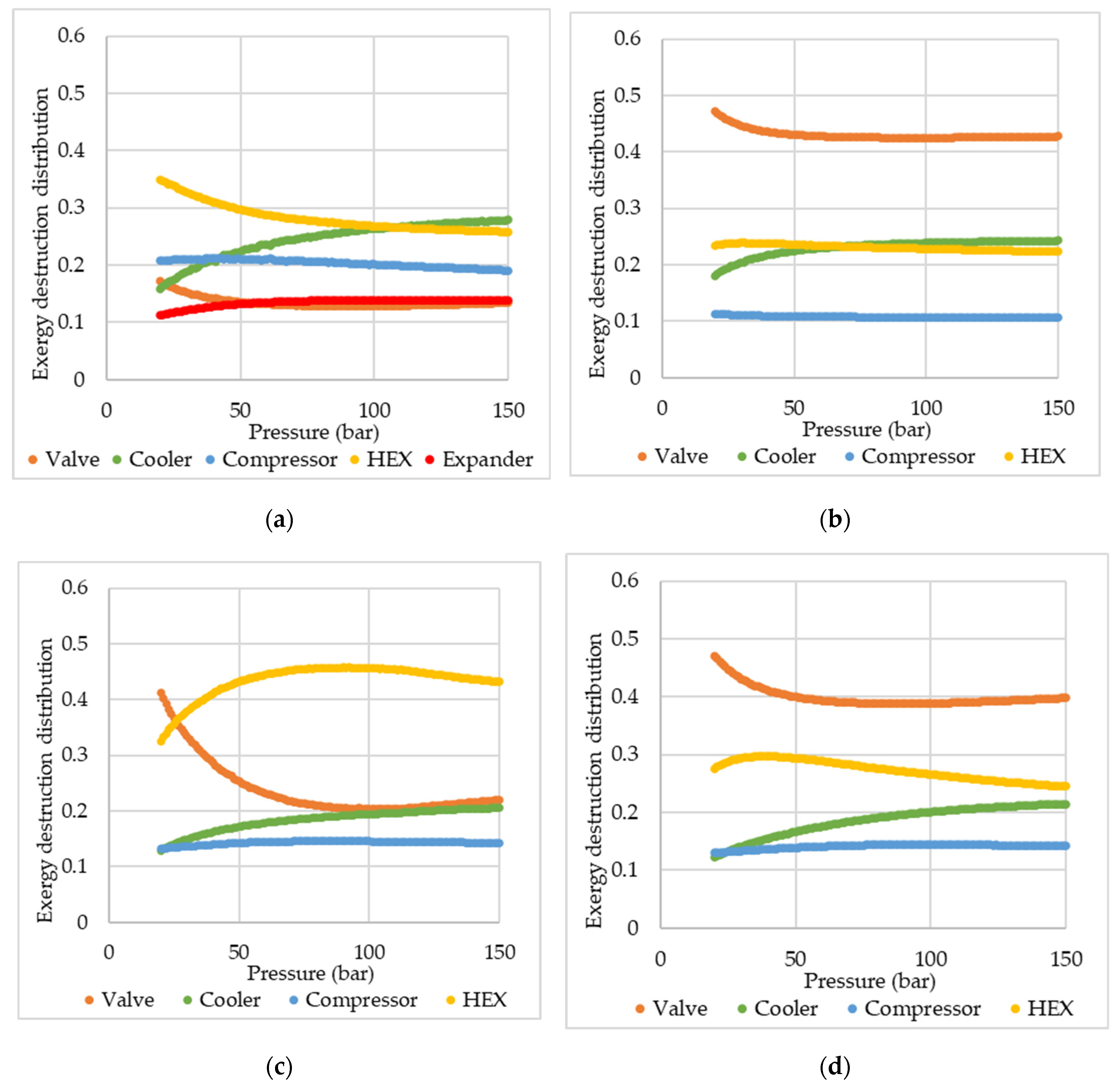

Figure 5 presents a comparison of the total exergy destruction among the cycles, while

Figure 6 presents the distribution profiles of exergy destruction among the pieces of equipment. In the exergy destruction distribution, the fractions of exergy destruction in mixers, splitters, and flash vessels are negligible and therefore are not shown in

Figure 6.

It is noted that in the PLH cycle, exergy destruction is more intense in the valves, while for the SMR, exergy destruction occurs more significantly in the heat exchangers. Even though heat exchangers are the device that has the greatest relative contribution to exergy destruction in the SMR, when absolute values are analyzed, the exergy destruction is slightly inferior in the mixed refrigerant cycle. With a multi-component refrigerant, the temperature glide allows the adjustment of the hot and cold composite curves more properly, considering that the refrigerant varies its temperature throughout its boiling.

Comparing SMR and DMR exergy distribution profiles (

Figure 6), there is an inversion in the device with the major contribution to the exergy destruction, changing from the heater exchangers in the SMR to the valves in the DMR. In the DMR, with the addition of a new refrigeration cycle, another valve was added, increasing, therefore, the exergy destruction in this piece of equipment. The increase is not verified in the same intensity on the heat exchanger due to the fact that hydrogen is cooled equally in both cases, i.e., essentially there is no increase in the heat exchanger duty, being the suiting of the composition curve the main factor in changes of the exergy destruction in this device. Nonetheless, it is noticeable that DMR presented a lower or close total exergy destruction than SMR. This result is expected, as increasing the number of pre-cooling cycles, thus, performing the hydrogen liquefaction through a greater number of stages, the process becomes closer to a reversible process, with less exergy destruction. Despite the close SEC found for the DMR and SMR, the lower exergy destruction in DMR is a clear indication that the cycle could be more efficient than SMR, as more suitable operating conditions were considered. These more appropriate conditions could be obtained by the optimization of the cycle specifications and MR compositions.

When comparing the exergy destruction results with those reported by Yang et al. (2023) [

25], it is visible that the participation of the valves in the exergy destruction was much more relevant in the present study. However, it is important to highlight that those authors conducted an optimization study to reduce SEC, which jointly reduces irreversibilities. Thus, the optimal conditions shift the cooling need to be mainly provided in heat exchangers at the detriment of valves, since isenthalpic expansion inherently has a significant irreversibility. In heat exchangers, irreversibility and exergy destruction can be more easily avoided by well-suited composite curves.

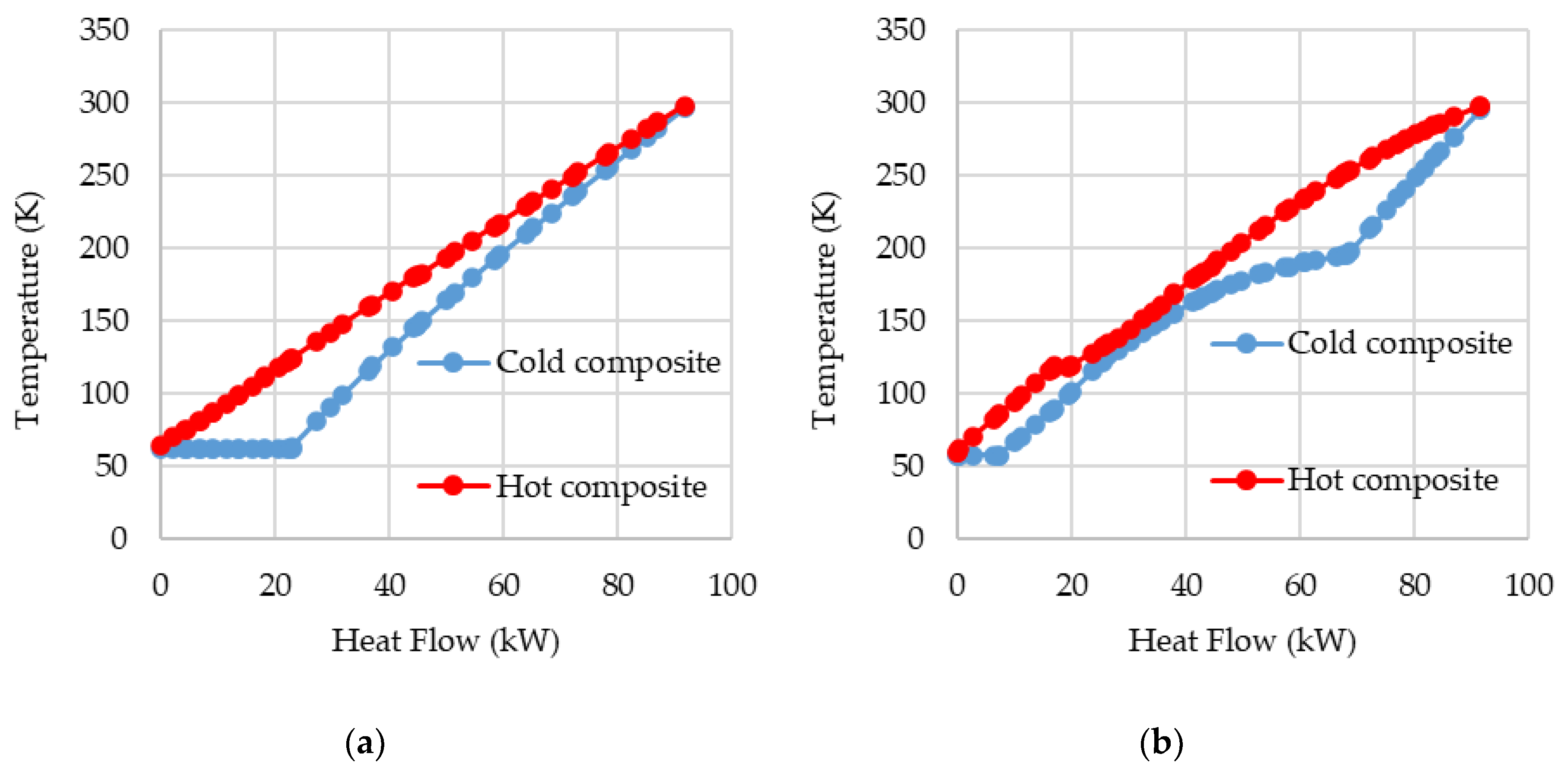

In

Figure 7, the composite curves for HEX-B1 and HEX-C1 are shown when both cycles, PLH and SMR, operate with a high pressure of 94 bar. It is notable that in lower temperatures, the composite curves are closer to each other in SMR than in PLH. That is because a multi-component refrigerant allows not only the temperature glide but also the adjustment of the specific heat capacity of that refrigerant. By optimizing the refrigerant composition, its specific heat capacity can be varied, and thus it would be possible to further decrease the distance between the hot and cold composite curves. The difference in both graphs is diminished as nitrogen cooling prior to the isenthalpic expansion is performed in HEX-B3. On the other hand, the mixed refrigerant pre-cooling is done in HEX-C1, the same heat exchanger that promotes the hydrogen pre-cooling. If both cycles were constructed analogously, i.e., with nitrogen pre-cooling, which is done separately at HEX-B3, being done at HEX-B1, as it is for the SMR cycle, a greater difference, regarding SMR’s greater effectiveness, would be perceived.

Still, in

Figure 7, it can be noticed that at higher temperatures, over 200 K, the mixed refrigerant in the SMR does not promote a well-suited cold composite curve, as the lightweight components of the refrigerant, despite their capacity to provide low temperatures for the cooling process, do not match the heat load needed in higher temperatures. Hence, using an external refrigeration cycle, with a refrigerant with heavier components, as in the DMR processes, would not only guarantee a well-suited curve in both temperature intervals but also a lower compression power [

7].

Despite those advantages, the DMR process presented SEC and exergy destruction values higher than expected, since with the increase in the degrees of freedom, the adjustment of the variables along the cycle without an optimization method is a more difficult procedure compared to the other simpler cycles. In addition, in neither the SMR nor DMR cycles was the refrigerant composition effect in the SEC analyzed. Thus, for future research, evaluating the effect of the refrigerant’s composition and its physical properties on the cycle performance, and even optimizing the refrigerants’ composition and cycle parameters, such as intermediate temperatures and/or refrigerant mass flow ratios for a proper comparison of the mixed refrigerant cycles, could be a possibility. Additionally, it is evident that the increase in the cycle complexity, i.e., increasing compression stages and the number of refrigerants and the number of refrigerant components, can improve its performance and reduce the SEC. Thus, to fully understand the applicability of the proposed cycles, in future studies, an economic analysis must be made. Moreover, optimization could also be performed from the economic point of view.

4. Conclusions

Despite the increasing research in hydrogen liquefaction, with the proposal of theoretical cycles that even approach the ideal efficiency, few studies fully investigate the behavior of hydrogen liquefaction cycles under varied conditions, only focusing on optimal points. In this study, therefore, four simple hydrogen liquefaction cycles, Claude, PLH, SMR, and DMR, were assessed regarding the influence of the cycle’s high operating pressure on energy efficiency parameters, exergy destruction, and its distribution along the pieces of equipment, and the influence of the hydrogen ortho-para conversion.

The Claude cycle presented the best SEC among the cycles, reaching 16.42 kWh/kgLH. Amidst the pre-cooled based cycles, the SMR presented the best efficiency, as, in contrast to PLH, it uses a non-pure refrigerant, and makes use of the temperature glide to promote a hydrogen pre-cooling to lower temperatures as well as a better suit of the composite curves. Nevertheless, the PLH cycle also presented a minimum SEC lower than the usually presented in the literature. The DMR cycle, notwithstanding its advantages of a better suit of the composite curve at higher temperatures and lower power consumption in its compression, as a function of its greater degrees of freedom, depends on optimization methods to achieve satisfactory results, with an SEC significantly lower than SMR. Further work could focus on the assessment of more complex cycles and employ optimization methods for some of the variables, along with the evaluation of the high-pressure impact on the cycle efficiency parameters.