1. Introduction

1.1. Global Developments in Hydrogen Energy

Hydrogen is being more widely recognized as a crucial component in the transition to a sustainable energy future, with numerous countries developing national hydrogen strategies strategies[

1]. Global hydrogen demand reached a record high in 2023 (up 2.5% from 2022) and is expected to continue growing in the coming years[

2]. By mid-century, hydrogen could meet an estimated 18% of the world’s final energy demand, helping to prevent about 6 Gt of CO₂ emissions annually. Projections show that by 2050, China’s hydrogen demand will be nearly 60 million tons annually, over 10% of its end-use energy, potentially reducing about 700 million tons of CO₂ emissions. This global and national momentum highlights hydrogen's broad potential to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors (e.g., heavy transport, industry) and to store and distribute renewable energy at scale. [

1].

However, realizing a “hydrogen economy” will require building a substantial hydrogen value chain, including large-scale transport and storage infrastructure. Unlike fossil fuels, hydrogen has very low energy density at ambient conditions (~3 Wh/L)[

3], making its distribution challenging. Pipeline networks for hydrogen remain limited (for example, the U.S. has ~2500 km of H₂ pipelines and the EU ~1600 km, whereas China has only ~100 km). Transporting hydrogen over long distances or in bulk will therefore likely rely on liquid hydrogen (LH₂), which drastically increases energy density. Indeed, liquefaction and intermediate cryogenic storage are expected to play a crucial role in future international hydrogen trade and long-distance delivery systems. In this context, the development of efficient hydrogen liquefaction technology and infrastructure has become a critical enabling step in the global hydrogen supply chain.

1.2. Hydrogen Liquefaction Technology

The process of liquefying hydrogen is crucial for developing hydrogen liquefaction systems. In 1898, James Dewar achieved this by cooling hydrogen after pressurizing it to 20 megapascals and then throttling it. As modern technology has advanced, hydrogen liquefaction technology has evolved into various processes. Currently, three processes are primarily employed: the Linde-Hampson (L-H) cycle, helium expansion refrigeration, and hydrogen expansion refrigeration. Recently, several new hydrogen liquefaction methods have been developed that effectively decrease the energy use of hydrogen liquefaction. Micro-liquefaction units with G-M type gas reheat cryocoolers are mainly used as cold sources, not for large-scale hydrogen storage and transport. Hydrogen liquefaction efficiency impacts overall energy use. Traditional hydrogen liquefaction involves nitrogen pre-cooling, hydrogen pressurization, and expansion refrigeration. This is followed by helium expansion refrigeration, which results in relatively high energy consumption.

Table 1 compares various hydrogen liquefaction processes.

The Linde–Hampson cycle, developed in the late 1800s by Carl von Linde and William Hampson, is a basic method for gas liquefaction, mainly suited for gases like nitrogen that can expand and cool at ambient temperatures. Due to the high theoretical specific work required for liquefaction, which was calculated to be as high as 68.10 kWh/kg, it is currently virtually unused. The Joule–Thomson refrigeration cycle, also called the throttling cycle, uses the Joule–Thomson effect to cool high-pressure gas through a throttle valve. The resulting transferred to the feed gas via a heat exchanger to achieve liquefaction. Since the Joule–Thomson coefficient of some gases is negative at high temperatures, the gas must be pre-cooled to enable effective throttling and cooling. This cycle has a simple structure and low equipment investment but low efficiency, making it suitable for small to medium-sized liquefaction units. In contrast, the Joule–Thomson + expansion refrigeration cycle, also known as the Claude cycle, adds an expansion machine to the throttling cycle. Part of the gas undergoes adiabatic expansion in the expansion machine to generate additional cooling capacity, thereby further improving cycle efficiency and reducing energy consumption. This cycle fully utilizes both throttling and expansion cooling mechanisms and is the mainstream process for large-scale liquefaction units. Since the single-pressure Claude cycle has a specific energy consumption of about 30 kWh/kg using liquid nitrogen pre-cooling, Baker[

4] proposed a two-pressure process that reduces energy in hydrogen liquefaction. The theoretical demand is 10.85 kWh/kg, common in large plants.

Currently, in practical applications, the energy consumption of the two-stage Claude cycle remains relatively high, typically exceeding 10 kWh/kg. To decrease the energy use in hydrogen liquefaction, new process configurations have been developed recently, such as mixed working fluid precooling, J-B (Joule-Brayton) cycles, and LNG precooling technologies. Traditional isothermal cold sources used for precooling cause large temperature differences between hot and cold fluids, leading to energy losses. In hydrogen liquefaction pre-cooling, about 80% of the cooling load is from feed hydrogen, and pre-cooling uses around 40% of total energy. Therefore, developing new pre-cooling methods, such as mixed working fluids, is crucial to better match temperatures and lower energy use.

Quack [

5] et al. introduced a Joule-Brayton (J-B) pre-cooled Claude cycle using propane, with helium-neon as the refrigerant in the low-temperature stage. Its specific energy consumption varies with product needs and feed gas conditions, usually staying below 5-7 kWh per kg of LH2. Kuz'menko et al. [

6] designed a process utilizing nitrogen pre-cooling and helium refrigeration, which exhibits high safety and pollution-free characteristics. Stang et al.[

7] conducted simulations based on data from the Ingolstadt liquefaction plant in Germany and designed an experimental hydrogen liquefaction facility using MR system pre-cooling. They reported current industrial energy consumption in the range of 11.9–13.6 kWh/kg LH₂, and through MR pre-cooling designs, they achieved simulations yielding 6.15–6.48 kWh/kg LH₂. Valenti, Macchi et al. [

8] proposed a hydrogen liquefier employing four helium Joule–Brayton cycles for cooling, achieving a capacity of 10 kg/s with an efficiency of approximately 48%. Asadnia, Mehrpooya et al. [

9] designed a process capable of producing 100 tons per day. The process begins by pre-cooling hydrogen to -198.2°C using an MR cycle and a hydrogen expansion refrigeration cycle. It then cools the hydrogen further to -251.8°C via six Joule-Brayton cascade refrigeration cycles. The process consumes 7.69 kWh per kilogram of liquid hydrogen and operates at an efficiency of 39.5%. Sadaghiani, Mehrpooya, et al.[

10] examined the effectiveness of different mixed refrigerants in low-temperature hydrogen liquefaction, achieving an efficiency of up to 55.47%. Yin, Ju et al. [

11] employed Aspen HYSYS software to simulate and improve a hydrogen liquefaction system that uses liquid nitrogen pre-cooling and helium expansion refrigeration. They utilized a genetic algorithm to optimize system parameters, resulting in a reduction of energy use to 7.13 kWh/kg LH₂ and achieving an efficiency of 49.41%. Amjad, Muhammad et al. [

12] designed a process that employs a mixed-fluid cascade model using Aspen HYSYS. They utilized the cooling energy from LNG during the hydrogen pre-cooling stage. which markedly decreased the total refrigerant needed, cut the cooling requirement by approximately 50%, and reduced the specific energy use to 7.64 kWh per kg of LH₂. The process achieved an efficiency of 42.25%. Naquash et al. [

13] using three MR cycles and one CO₂ cycle, achieving energy consumption of 7.63 kWh/kg and efficiency of 31.4%. Wang Guocong et al. [

14] enhanced the MR refrigeration cycle with a genetic algorithm, achieving a 24.07% decrease in specific energy use. Wang Chao et al. [

15] used a particle swarm optimization algorithm to improve the MR pre-cooling process, lowering the specific energy consumption to 6.98 kWh/kg LH₂ after optimization. Xu and Lin [

16] proposed an integrated hydrogen and LNG production process using industrial by-product gases as feedstock, employing a two-stage helium reverse Brayton cycle. Bi et al. [

17] optimized a novel hydrogen liquefaction process using circulating hydrogen refrigeration, demonstrating improved energy efficiency. Naquash et al. [

18] improved hydrogen liquefaction efficiency by combining absorption refrigeration with an ORC-driven liquid air energy system. Zhang and Liu [

19] performed an in-depth design and analysis of a hydrogen liquefaction process, evaluating its energy efficiency, environmental effects, and economic feasibility across various setups.

Table 2 presents key performance indicators for hydrogen liquefaction cycles, measuring energy use, efficiency, and yield to compare process schemes.

Currently, many new hydrogen liquefaction processes remain in the theoretical research stage and have not yet been widely adopted in actual production. These processes are typically complex and involve significant equipment investment costs. For example, the typical J-B process employs a mixed working fluid pre-cooling cycle, primarily drawing on MRC technology from the large-scale natural gas liquefaction industry[

20], which requires the use of multi-stage oil-free compressors and other high-end equipment, significantly increasing overall costs. Compared to liquid nitrogen pre-cooling, these technologies may not offer obvious cost advantages, thereby limiting their application in commercial settings. On the other hand, liquid two-phase low-temperature expansion machines and low-temperature compressor technologies are still immature, and some new processes require these technologies, making it difficult to implement these processes in practice.

Table 3 presents a comparison of various simple basic hydrogen liquefaction processes.

1.3. Global Liquid Hydrogen Plant Projects

Recently, the United States, South Korea, and China have been actively developing liquid hydrogen facilities and growing their hydrogen energy infrastructure. For example, Air Products' liquid hydrogen plant in La Porte, Texas, began operation in October 2021, producing roughly 30 tons daily. The company is also developing China's first large-scale commercial liquid hydrogen plant in Haiyan, Zhejiang Province, with a planned daily capacity of 30 tons. Originally set to begin operations in 2022, it will be Asia's first liquid hydrogen plant of this magnitude. Plug Power launched the largest electrolyzed hydrogen plant in the United States in early 2024 in Georgia, with a daily capacity of around 15 tons, supported by PEM electrolyzers and cryogenic liquefaction for uses like hydrogen-powered forklifts. South Korea's first commercial liquid hydrogen plant, built by Doosan Enerbility, was finished in August 2023 and started operations in early 2024, with a daily output of about 5 tons. The project is backed by local government funding for developing a hydrogen refueling station network. Additionally, South Korea plans to construct a liquid hydrogen plant in Ulsan in collaboration with Hyosung Group and Linde (planned daily production of approximately 36 tons) and an Incheon project (planned daily production of approximately 82 tons). Hydrogen liquefaction facilities are located in countries including the United States, Canada, Japan, and China. Air Products, established in 1942 and headquartered in the United States, provides more than half of the hydrogen liquefaction units in the country, but it has not yet entered the Chinese market. Meanwhile, Plug Power, a provider of hydrogen energy solutions, is actively expanding its involvement in the hydrogen liquefaction industry.

2. Simulation Tools and Process Design

The simulation software used in this paper, Aspen HYSYS V14, is a comprehensive and powerful process simulation software developed by Aspen Tech, Inc. in the United States. HYSYS provides a wealth of physical property data, dynamic simulation capabilities, energy analysis tools, safety system design, and control system design functionality.

2.1. Ortho- and Para-Hydrogen Properties

Diatomic hydrogen has two spin isomers: ortho-hydrogen (parallel proton spins) and para-hydrogen (antiparallel spins). They differ in energy and properties, with ortho-hydrogen higher in energy and predominant at room temperature. At low temperatures, ortho converts to para, releasing heat. It’s important to consider these spin isomers when handling liquid hydrogen.

Under ideal conditions, oxygen concentration during liquefaction should be balanced to release conversion heat at the highest temperature. However, integrating the catalytic bed and heat exchanger is relatively challenging. In modern hydrogen liquefaction technology, to enhance efficiency and optimize energy consumption, most hydrogen liquefaction units employ multi-stage conversion processes to approximate a continuous conversion process. In these processes, hydrogen gas or liquid hydrogen undergoes catalytic conversion through a bed of solid catalyst. Catalytic conversion reactions can generally be classified into the following three categories:

- (1)

Isothermal reaction: In this process, no external cooling source is used; instead, the heat produced by the reaction itself raises the temperature of the hydrogen gas. To effectively manage the heat generated in this scenario, a multi-stage temperature control approach is typically employed, using multiple isothermal conversion beds to gradually remove heat and maintain thermal equilibrium in the system.

- (2)

Isothermal reactions: These reactions occur in fine tubes or channels filled with catalyst, using liquid nitrogen or liquid hydrogen for external cooling to maintain a constant temperature during the reaction process. Although this method has relatively high energy consumption, its reactor design is simple, operation is convenient, and it requires less catalyst, making it suitable for applications requiring precise temperature control.

- (3)

Continuous reaction: In this mode, the catalyst is filled into the heat exchanger channels to achieve continuous cooling and conversion of the feed gas. Although this method has the lowest energy consumption, it is structurally complex, requires a large amount of catalyst, and has high flow resistance, making design and maintenance more complicated. In fact, an integrated catalyst heat exchanger has been developed and tested, and this design has been applied in hydrogen liquefaction facilities in Ontario and California, demonstrating its effectiveness in achieving near-ideal continuous conversion processes.

Common measures include using catalysts (such as iron hydroxide and chromium oxide) to speed up the conversion of para-hydrogen during hydrogen liquefaction, thereby reducing boiling during storage. Since the HYSYS software does not include a normal-isomeric hydrogen converter module, this module is represented in this paper by a heat exchanger and a heater.

2.2. Purification of Hydrogen Feed Gas

The sources of raw hydrogen are diverse, including water electrolysis, catalytic cracking of ammonia or methanol, synthesis gas from ammonia production, natural gas reforming, refinery off-gas, coke oven gas, and chemical process off-gas. The hydrogen supplied from these sources varies significantly in hydrogen content and impurity levels.For example, the hydrogen gas volume fraction obtained from synthetic ammonia feed gas is typically around 70%, but it also contains a significant amount of nitrogen and carbon monoxide; hydrogen produced via natural gas reforming can achieve a volume fraction of 95%, though it also contains methane and carbon monoxide; hydrogen generated through water electrolysis is relatively pure but may still contain trace amounts of nitrogen and oxygen impurities.These impurities can have adverse effects on catalysts, such as reducing catalyst efficiency, causing incomplete conversion, or leading to blockage of conversion pathways. In particular, hydrogen with high oxygen content may form solid oxygen at lower temperatures, and accumulated solid oxygen could trigger explosions. Therefore, thorough purification treatment before hydrogen enters the conversion or liquefaction stage is critical.

In the Leuna and IDEALHY hydrogen liquefaction projects, purifiers improve hydrogen purity, differing from the Ingolstadt plant. At Leuna and IDEALHY, purification happens in the pre-cooling heat exchanger instead of an independent nitrogen bath. This paper assumes the feed hydrogen is already purified to 99.9999%, crucial for process efficiency and safety.

2.3. Precooling Methods

During gas liquefaction, adding more pre-cooling stages usually lowers total energy use. However, this approach also increases equipment complexity and raises operational and maintenance costs. Therefore, it is essential to strike a balance between improving efficiency and controlling costs, and to select the appropriate number of pre-cooling stages. Typically, in lower conventional temperature zones, pre-cooling agents such as liquid ammonia or propane can reduce temperatures to 238–248 K. In lower temperature ranges, whether at atmospheric pressure or reduced pressure, liquid nitrogen is a commonly used pre-cooling agent, capable of lowering hydrogen temperatures to 65–80 K. In ammonia synthesis plants, liquid ammonia is frequently used as a pre-cooling agent due to its ease of availability, reducing temperatures to 223–233 K. However, some facilities producing liquid ammonia may opt for fluorocarbons, which pose greater potential environmental hazards, despite their higher costs. Additionally, within the temperature range between liquid ammonia and liquid nitrogen, liquefied natural gas (LNG) can also be used as a pre-coolant to further reduce hydrogen temperature to 110 to 120 K. Due to methane's significant Joule-Thomson (JT) effect during throttling expansion, its efficiency is two to three times that of other gases, making LNG the preferred pre-coolant. However, since liquid hydrogen production facilities typically do not produce LNG, its use is limited.

Considering that liquid nitrogen is relatively easy to obtain—it can be produced by repeatedly compressing and throttling air to obtain liquid air, followed by separation to obtain liquid nitrogen—and has lower costs, this study selected a liquid nitrogen system for pre-cooling. This method reduces hydrogen temperature and supports economic and environmental sustainability.

2.4. Refrigeration Methods

When designing small-scale hydrogen liquefaction equipment, priority should be given to simple refrigeration processes to ensure stable operation while also considering energy consumption. When designing large-scale hydrogen liquefaction plants, it is crucial to carefully consider low energy consumption, minimal investment costs, and operational safety and reliability.

- (1)

Helium Expansion Refrigeration

The helium expansion refrigeration process typically begins with liquid nitrogen pre-cooling, followed by further cooling of the raw hydrogen gas through a multi-stage helium expansion heat exchanger. Concurrently, catalytic conversion of normal hydrogen to deuterated hydrogen is performed to enhance liquefaction efficiency. Helium is recycled through multiple heat exchangers, expansion, compression, and cooling to maintain the system's low temperature. As an inert gas, helium offers high safety, remains gaseous at all times, has a simple design, and achieves high efficiency, making it suitable for liquid hydrogen production units with a daily output of less than 3 tons. This study selects helium expansion refrigeration as the primary cooling strategy.

- (2)

Hydrogen expansion refrigeration

Hydrogen expansion refrigeration is divided into two types: independent hydrogen cycle and split hydrogen cycle. In the independent cycle, hydrogen is compressed, water-cooled, and pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen before expanding to cool down, with part of the cooled hydrogen being recycled.The Japanese WE-NET project employs this process, combining cooling and expansion refrigeration into two steps, with liquid hydrogen ultimately stored stably at 20.4 K and 106 kPa. In the split-flow cycle, hydrogen gas is compressed, pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen, and divided into two streams. One stream expands to cool and form the cold stream, while the other undergoes heat exchange in a heat exchanger and undergoes normal-para conversion.The U.S. Praxair adopts this method, achieving efficient and safe liquefaction through precise thermal management and split control.

- (3)

Hydrogen throttling expansion

When hydrogen undergoes expansion via a throttle valve, cooling is achieved through the Joule–Thomson (J–T) effect. This phenomenon elucidates the temperature variation in real gases during isenthalpic throttling, driven by intermolecular forces. It is a widely employed cooling method in gas liquefaction processes.

2.5. Equations of State

In Aspen Plus software, users can select from a variety of cubic state equations, including options based on SRK (Soave-Redlich-Kwong) such as RK-SOAVE, RK-ASPEN, RKSMHV2, and RKSWS, as well as options based on PR (Peng-Robinson) such as Peng-Robinson, PRMHV2, and PRWS. The Peng-Robinson state equation is particularly suitable for mixtures containing non-polar and weakly polar components with light gases, and demonstrates superior performance in terms of computational accuracy. This makes it particularly suitable for simulating hydrogen liquefaction processes, enabling the accurate prediction of thermodynamic properties involving light components such as hydrogen, thereby optimizing the design and operation of these processes.

In hydrogen liquefaction processes, particularly when no complex chemical reactions are involved and the primary goal is to liquefy gases, the Peng-Robinson equation provides a reliable basis for property calculations. The specific form of this equation is as follows:

2.6. Optimization Methods

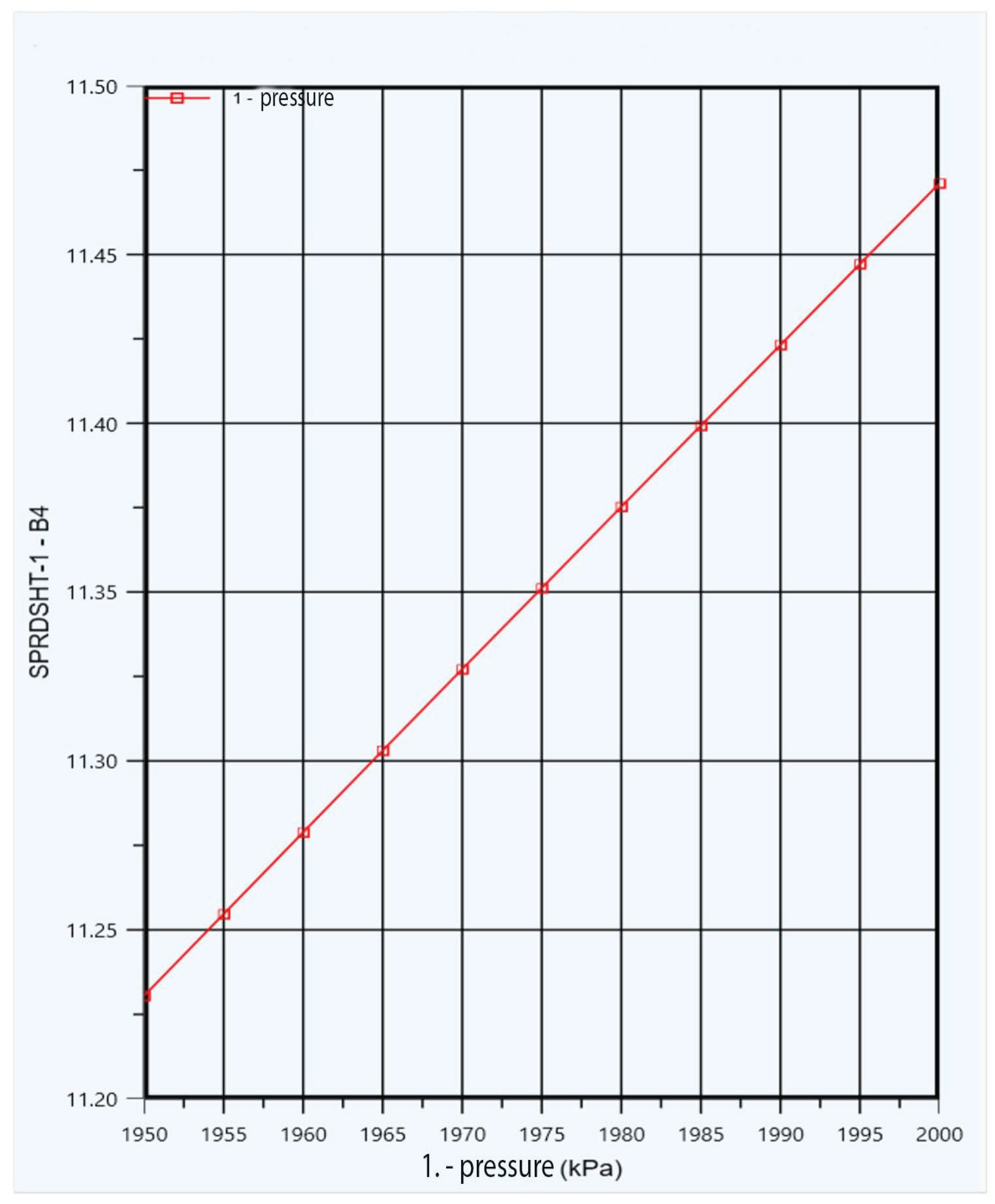

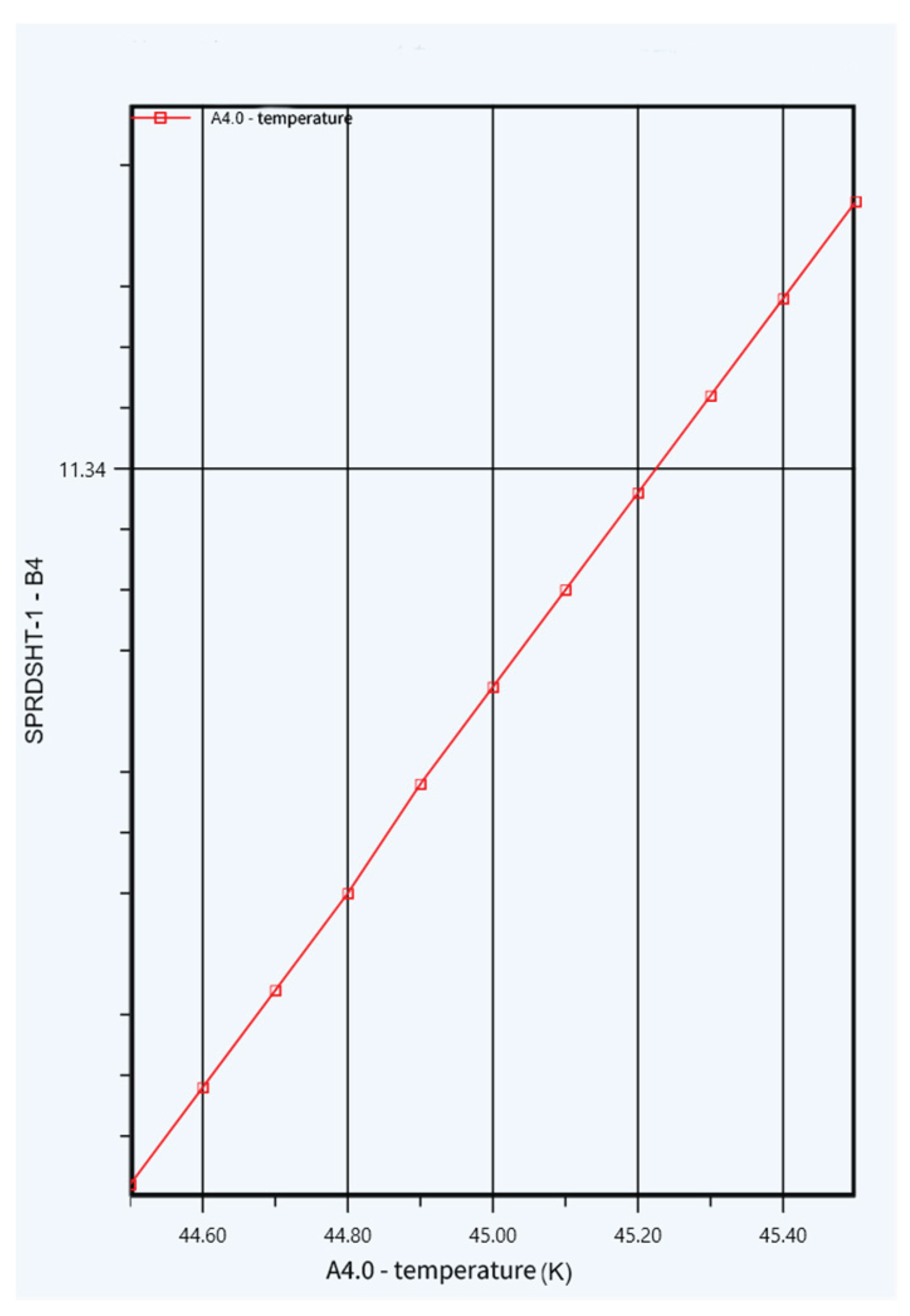

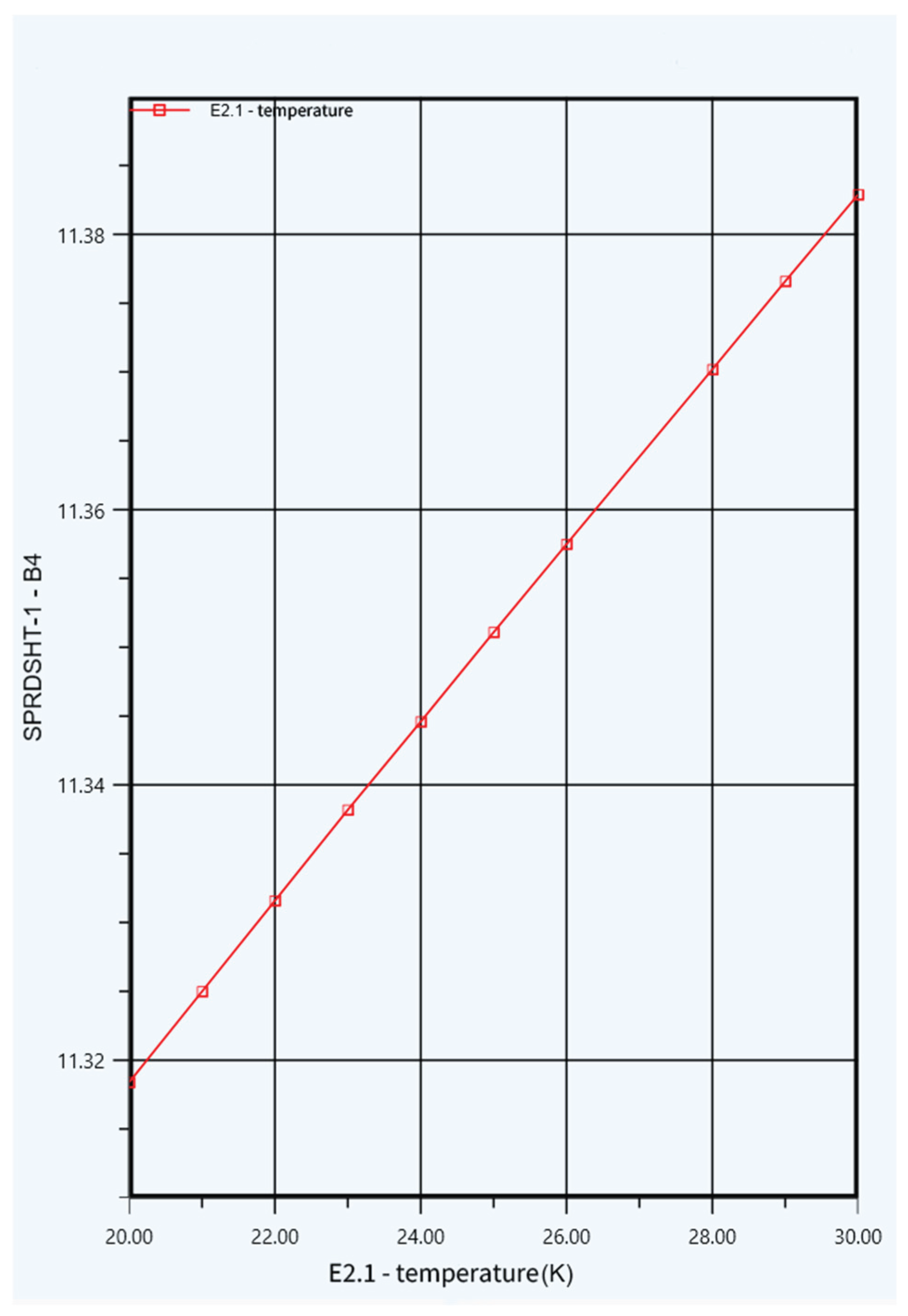

HYSYS has five optimizer modes: Original, Hyprotech SQP, MDC Option, Data Rccon, and Selected Optimization. Its built-in optimizer helps improve hydrogen liquefaction processes by minimizing specific energy consumption (SEC), a key efficiency measure. SEC is often defined as the amount of energy required to produce one unit of liquid hydrogen, calculated as follows:

Where: - total energy consumption of compressors (kWh); - energy output of expanders (kWh); - Mass flow rate of liquid hydrogen (kg).

In chemical thermodynamics, other indicators of the process irreversibility, such as exergy efficiency and exergy destruction, are often used to evaluate hydrogen liquefaction processes. Along with specific energy consumption (SEC), which represents energy efficiency, the two sets of indicators aim to encapsulate the thermodynamic optimization of the system, as well as represent how close the system's performance is to ideal performance.

Exergy efficiency is a quantitative measure of thermodynamic performance because it is defined as the real power delivered to the system divided by the maximum and theoretically possible power that could be delivered. Higher performance indicates better energy utilization and lower irreversible losses. This level of performance also significantly affects the economic and environmental performance of the system. The exergy efficiency can easily be determined as follows:

Where: h - specific enthalpy at the relevant state, kJ/kg; s - specific entropy at the relevant state, kJ/(kg·°C); - ambient temperature, 298.15 K.

In order to provide safety and stability to optimization calculations, use two constraints and a penalty function to resolutely secure hydrogen liquefaction. If any constraints are breached during optimization, the objective function's value will rise, and this value is considered the penalty function output. In this paper's specific application, the key constraint is ensuring that the minimum temperature difference between all heat exchanger levels remains above 2 K.

In the formula, the subscript ‘min’ represents the smallest allowable temperature difference for heat transfer in the heat exchanger, while the superscript ‘HEX1–8’ denotes heat exchangers 1 through 8.

2.7. Process Design

The entire hydrogen liquefaction process begins by introducing hydrogen into a cold box, where it undergoes multiple stages of pre-cooling and conversion to ensure efficient liquefaction. First, in the primary and secondary heat exchangers, hydrogen is successively cooled using cold nitrogen gas and liquid nitrogen. Next, the hydrogen undergoes isothermal chemical conversion in the first-stage normal-para conversion reactor, then flows through third- and fourth-stage heat exchangers for cooling, and undergoes adiabatic conversion in the second-stage normal-para conversion reactor, releasing heat to raise the hydrogen temperature. Subsequently, the hydrogen is recirculated to the fourth-stage heat exchanger for further cooling, thereby optimizing energy utilization. After further cooling through multiple heat exchangers, the hydrogen is throttled and cooled via a J-T valve, then undergoes another adiabatic conversion in the final stage before being stored in liquid hydrogen storage Dewar flasks for use or transportation.

Meanwhile, helium gas is discharged from the compressor under high pressure, first cooled, then further cooled through primary and secondary heat exchangers using cold nitrogen gas and liquid nitrogen, and finally undergoes adiabatic expansion cooling through two stages of series-connected turbines to produce low-temperature, low-pressure helium gas. This helium gas is recycled through heat exchangers to recover heat and circulates back to the compressor, optimizing energy use and ensuring efficient system operation.

This section uses Aspen HYSYS, a chemical engineering software, to simulate the process at steady state. The simulation employs the Peng-Robinson equation with these assumptions:

- (1)

The process remains steady, ignoring kinetic and potential energy effects.

- (2)

Since the HYSYS software does not include a normal-to-isoparaffin hydrogen converter module, the converter is represented by a heat exchanger and a heater;

- (3)

The feed gas is pure hydrogen (99.9999% purity), at 300 K, 2400 kPa pressure, and with a hydrogen concentration of at least 95%.

- (4)

The temperature differential across the multi-pass heat exchanger exceeds 2 K.

- (5)

The compressor's adiabatic efficiency is 80%, while the expander's isentropic efficiency is 75%.

- (6)

The pressure drop for both the water cooler and the multi-pass heat exchanger is set to zero.

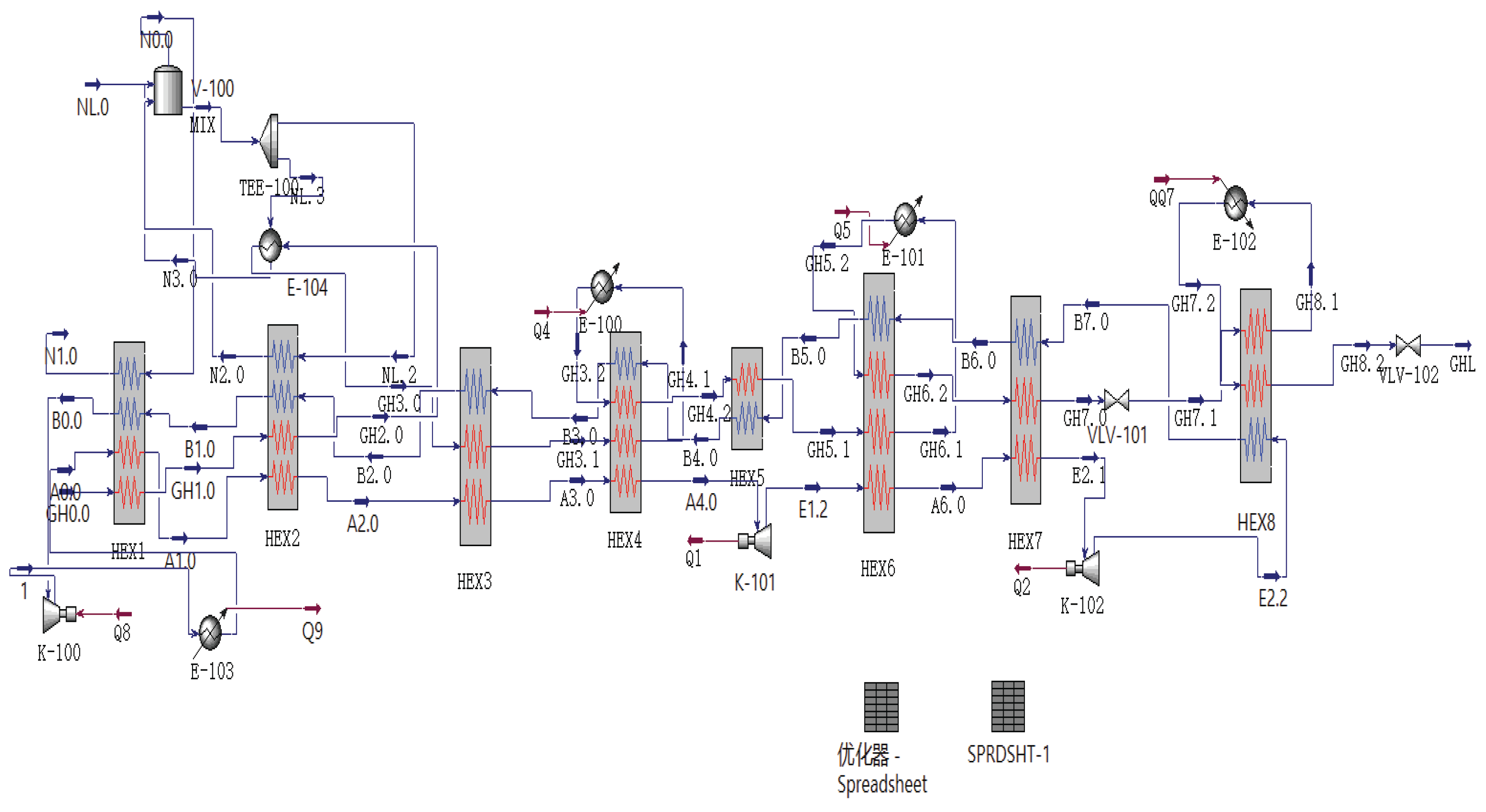

Based on the above six assumptions, a simulation was conducted, and the resulting flowchart is shown in

Figure 1.