Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Ethical Statement and Patient Consent

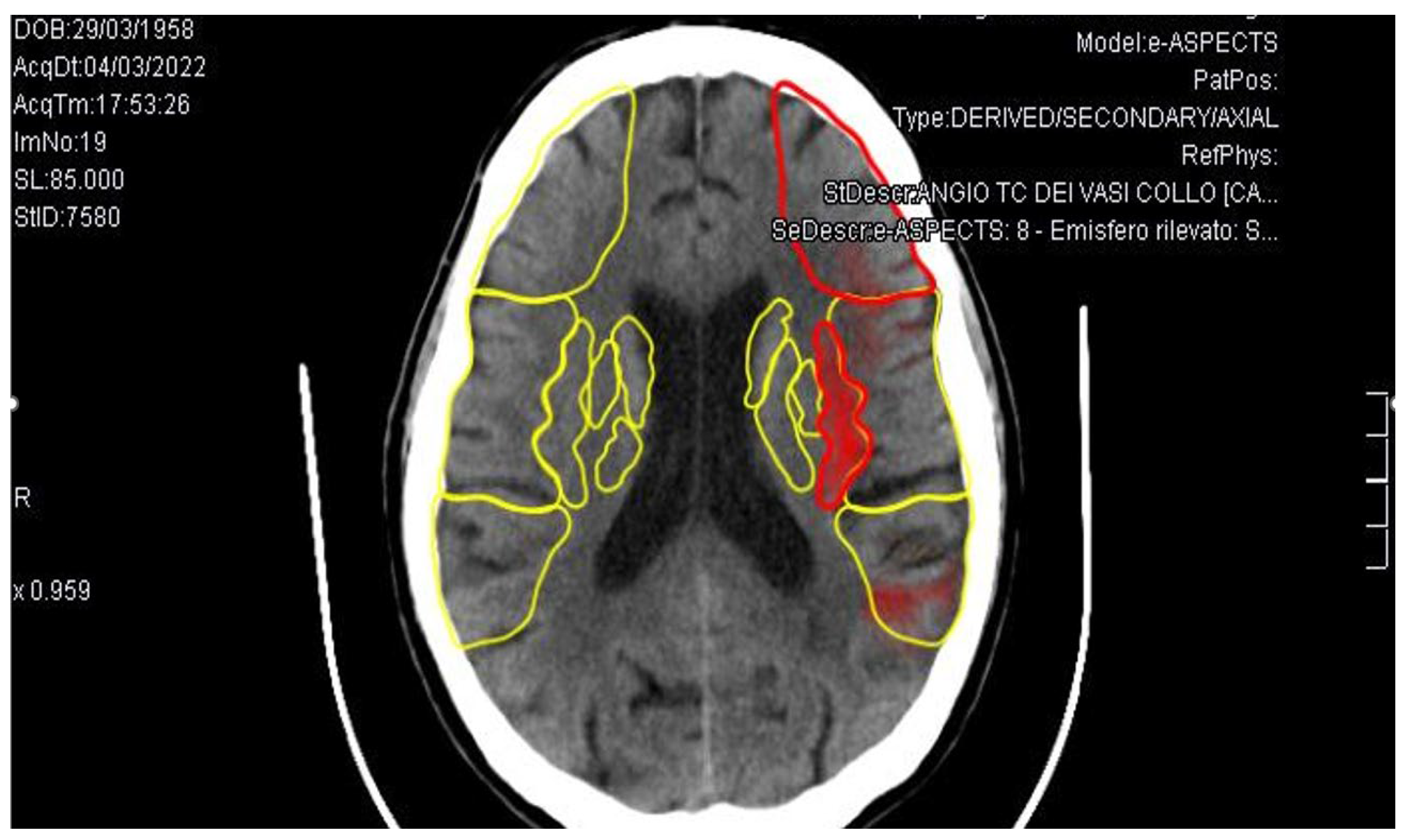

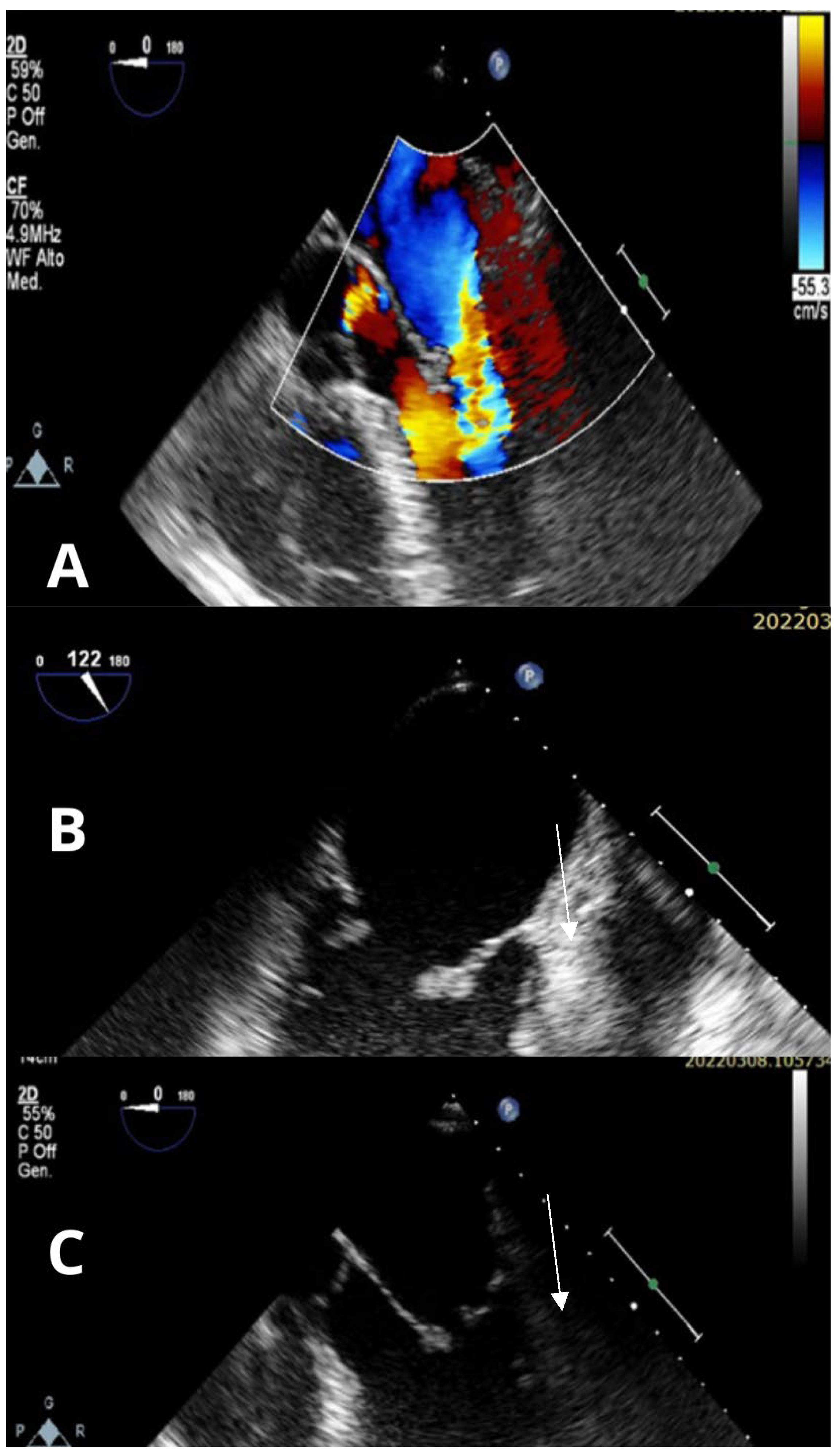

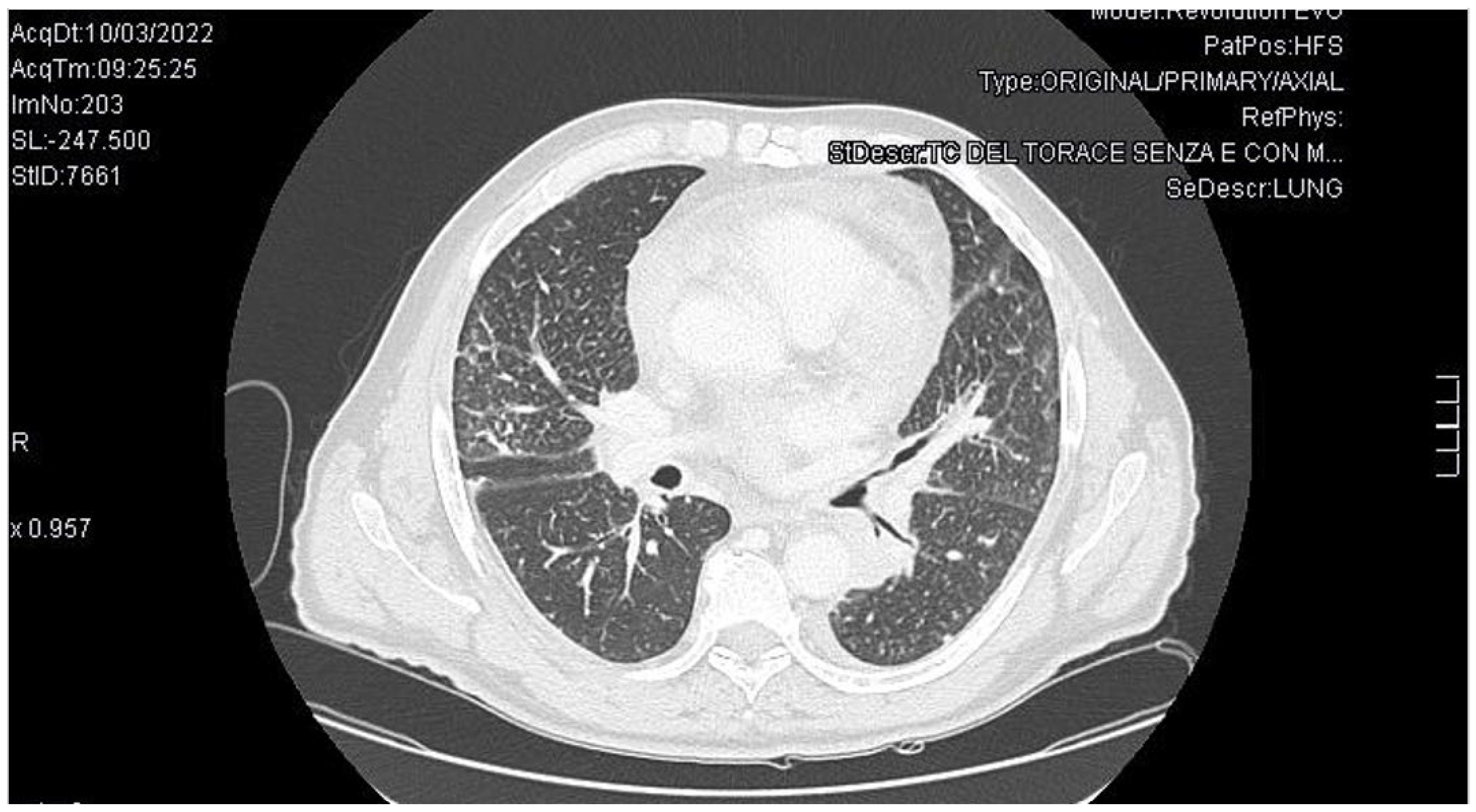

3. Case Report

4. Discussion

| Therapy | Indications | Advantages | Limitations/Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) | First-line for treatment and prevention of VTE in cancer patients. | Proven efficacy, reduced VTE vs warfarin, easy dosing | Injection route, bleeding risk, impaired renal function. |

| Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)#break# (edoxaban, rivaroxaban, apixaban) |

Alternative to LMWH in selected patients. | Oral administration, non-inferior efficacy. Apixaban don not increased bleeding risk. | Avoid in unresected GI/GU cancers, CrCl <15, platelets <50k, recent surgery, bleeding risk |

| Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs) | Alternative if DOACs/LMWH not suitable | Oral, long experience | Drug–food interactions, INR monitoring required, less preferred |

| Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) | Hospitalized patients, rapid reversal needed | Short half-life, reversible | Requires monitoring (aPTT), IV route |

| Anticoagulation Duration | ≥6 months recommended (individualized) | Reduces recurrence | Reassess bleeding periodically, especially in advanced cancer |

| Category | Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Patient-related | Older age, immobility, comorbidities (e.g., hypertension), history of thrombosis |

| Tumor-related | Histological type (especially adenocarcinoma), tumor burden, metastasis |

| Biological mediators | Tissue factor (TF), mucins, PAI-1, cytokines, hypoxia |

| Treatment-related | Chemotherapy (e.g., platinum compounds), hormonal therapy, antiangiogenics |

| Drug interactions | DOAC metabolism affected by CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitors (e.g., tyrosine kinase inhibitors) |

| Procedural | Central venous catheters (CVCs), recent surgery |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANA: | antinuclear antibodies |

| ASCO: | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| CAT: | Cancer associated thromboses |

| CRP: | C-reactive protein |

| CVC: | Central Venous Catheter |

| DDIs: | drug–drug interactions |

| DOAC: | Direct oral anticoagulant |

| ED: | Emergency department |

| ENA: | extractable nuclear antigens |

| ESC: | European Society of Cardiology |

| EEU: | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Equivalent Units |

| GI: | gastrointestinal |

| GU: | genitourinary |

| ICI: | immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| LMWH: | low-molecular-weight heparin |

| NBTE: | non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis |

| NIHSS: | National Institutes of health Stroke Scale |

| PAI-1: | plasminogen activator inhibitor |

| PE: | Pulmonary embolism |

| PICC: | peripherally inserted central catheter |

| P-gp: | P-glycoprotein |

| TF: | tissue factor |

| TKIs: | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| TOE: | transesophageal echocardiogram |

| TTE: | Transthoracic echocardiography |

| UFH: | unfractioned heparin |

| VKA: | vitamin K antagonists |

| VTE: | venous thromboembolism |

| WBC: | white blood cell |

References

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 4229–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, F.I.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; van Es, N.; et al. Risk scores for occult cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: Results from an individual patient data meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 2622–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trousseau, A. Lectures on Clinical Medicine; The New Sydenham Society: London, UK, 1868; Volume 5, pp. 281–331. [Google Scholar]

- Varki, A. Trousseau’s syndrome: Multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood 2007, 110, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimine, K.; Ooka, Y.; Ochi, N.; et al. Trousseau’s Syndrome in Lung Cancer Patients: A Retrospective Study in a Japanese Community Hospital. Cureus 2024, 16, e68400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brice, P.; Bastion, Y.; Lepage, E.; et al. Comparison in Low-Tumor-Burden Follicular Lymphomas Between an Initial No-Treatment Policy, Prednimustine, or Interferon Alfa: A Randomized Study From the Groupe D’Etude Des Lymphomes Folliculaires. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; de Waha, S.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.Y.; Levine, M.N.; Baker, R.I.; et al. Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin versus a Coumarin for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, S.; Lee, A.Y.Y.; Kakkar, A.K.; et al. Low-molecular-weight-heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in high- and low-risk patients with active cancer: A post hoc analysis of the CLOT Study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2019, 47, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskob, G.E.; van Es, N.; Verhamme, P.; et al. Edoxaban for the Treatment of Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Marshall, A.; Thirlwall, J.; et al. Comparison of an Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2017–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, G.; Becattini, C.; Meyer, G.; et al. Apixaban for the Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism Associated with Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.S.; Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2373–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahé, I.; Meyer, G.; Puglisi, R.; et al. Extended Reduced-Dose Apixaban for Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, N.S.; Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 38, 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; Culakova, E.; Lyman, G.H.; Francis, C.W. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008, 111, 4902–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Winter, M.A.; van Es, N.; van den Berg, M.E.L.; et al. Estimating Bleeding Risk in Patients with Cancer-Associated Thrombosis: Evaluation of Existing Risk Scores and Development of a New Risk Score. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Lin, L.; Li, C.; et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality in Trousseau syndrome: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Thromb. J. 2025, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, H.T.; Mellemkjaer, L.; Olsen, J.H.; Baron, J.A. Prognosis of cancers associated with venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 343, 1846–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikushima, S.; Ono, R.; Fukuda, K.; Sakayori, M.; Awano, N.; Kondo, K. Trousseau’s syndrome: Cancer-associated thrombosis. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 46, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzeszcz, K.; Rhone, P.; Kwiatkowska, K.; Ruszkowska-Ciastek, B. Hypercoagulability State Combined with Post-Treatment Hypofibrinolysis in Invasive Breast Cancer: A Seven-Year Follow-Up Evaluating Disease-Free and Overall Survival. Life 2023, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, N.; Colombo, E.; Tenconi, M.; Baldessin, L.; Corsini, A. Drug-Drug Interactions of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs): From Pharmacological to Clinical Practice. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioretti, A.M.; Tartaglia, D.; Silvestri, M.; et al. Prevention of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC)-Associated Vein Thrombosis in Cancer: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, Y.; Kano, Y. Three-territory sign in Trousseau’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e250640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.X.; Cheng, J.O.S.; Sharip, M.T.; Hlaing, H.H.; Allison, M. Trousseau’s syndrome with non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) in a patient with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin. Med. 2023, 23, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeng, C.; Takx, R.A.P. Cancer-associated marantic endocarditis: a rare but relevant complication. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, 1627–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengo, V.; Denas, G.; Zoppellaro, G.; et al. Rivaroxaban vs Warfarin in High-Risk Patients with Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Blood 2018, 132, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmaili, M.; Alzubi, J.; Lo Presti Vega, S.; Ababneh, E.; Xu, B. Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis: A state-of-the-art contemporary review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 74, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).