Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

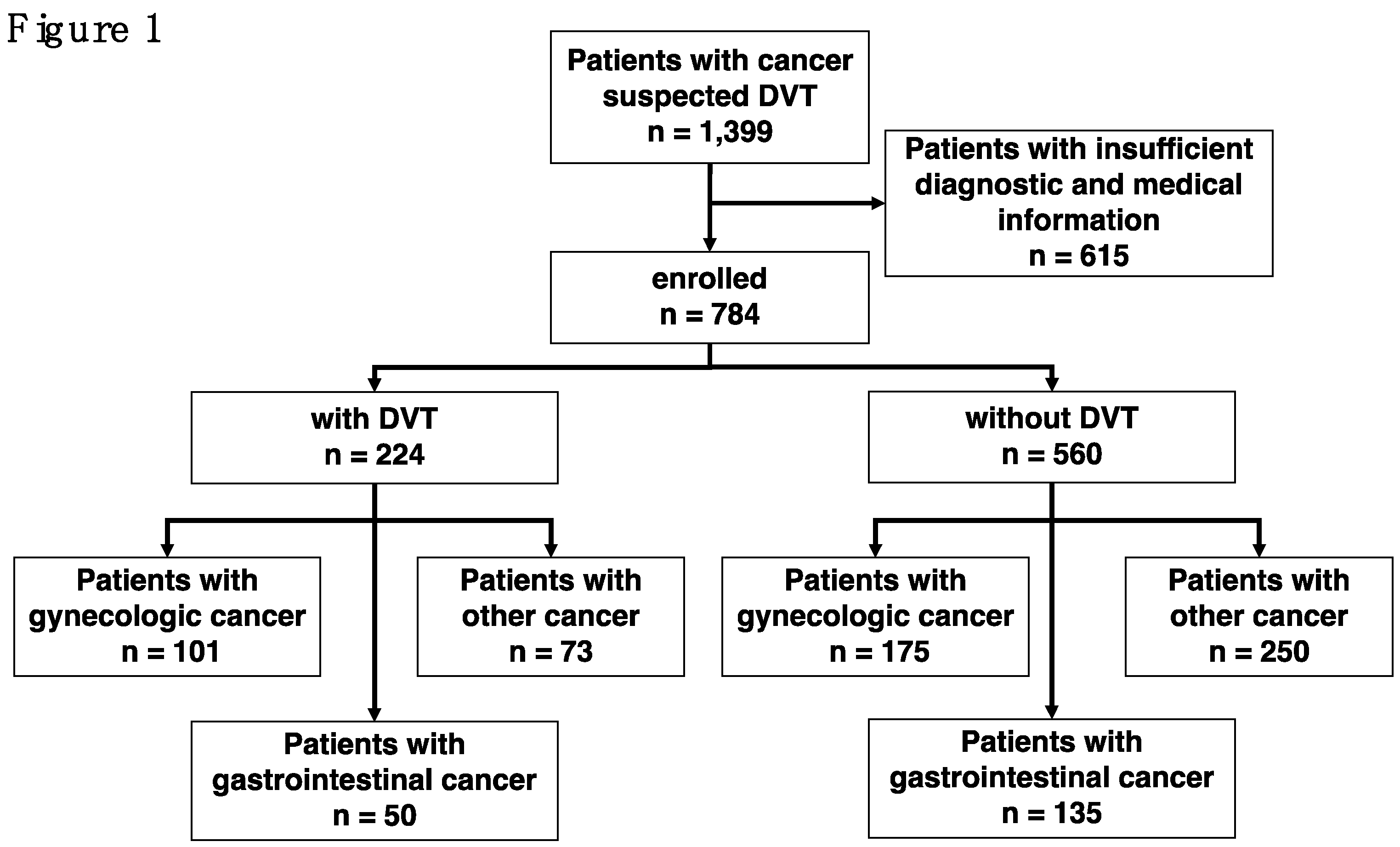

2.1. Studied Patients and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Analysis of Cancer Patients and Their Survival in Relation to Prognostic Factors

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

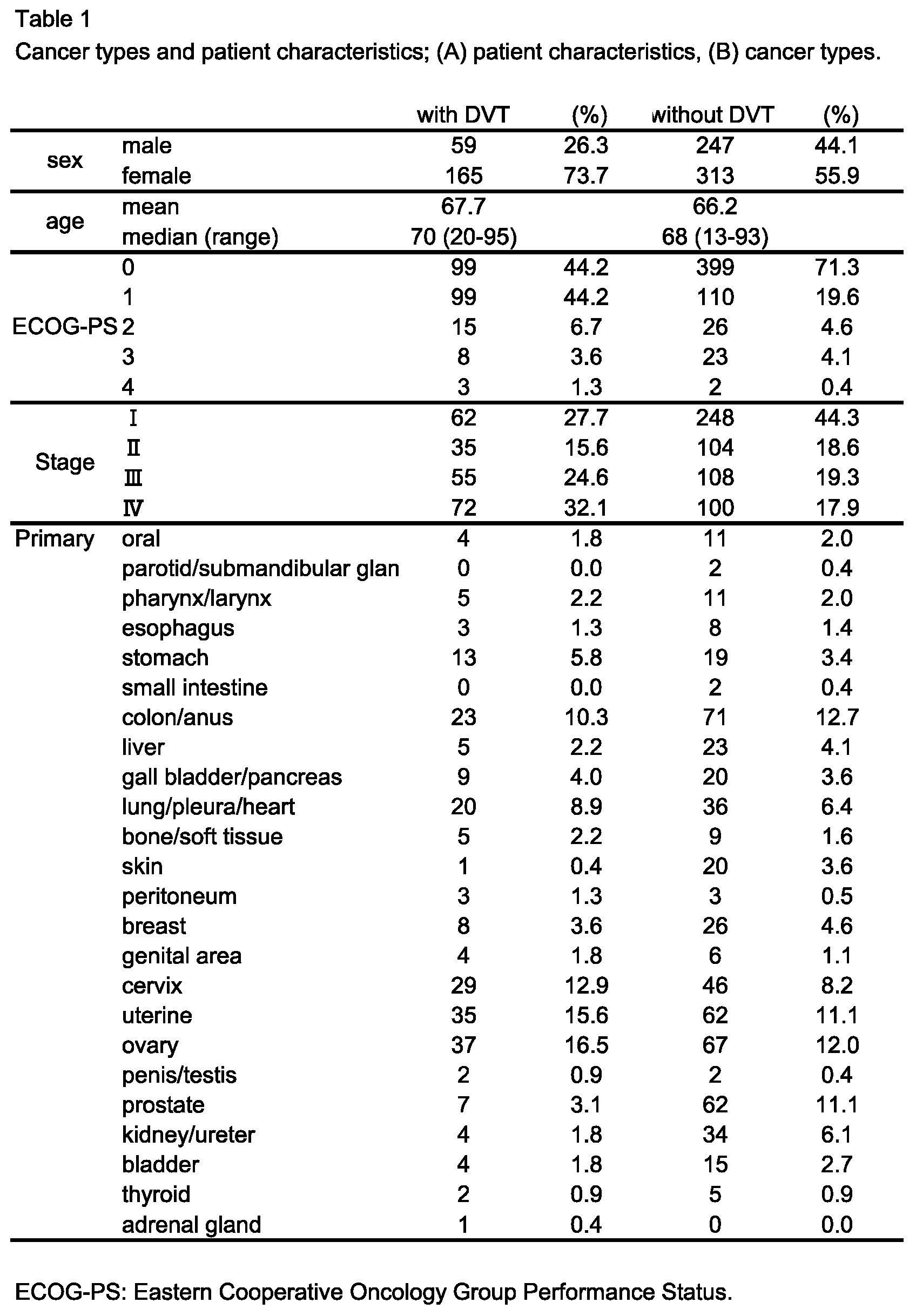

3.1. Patient Demographics

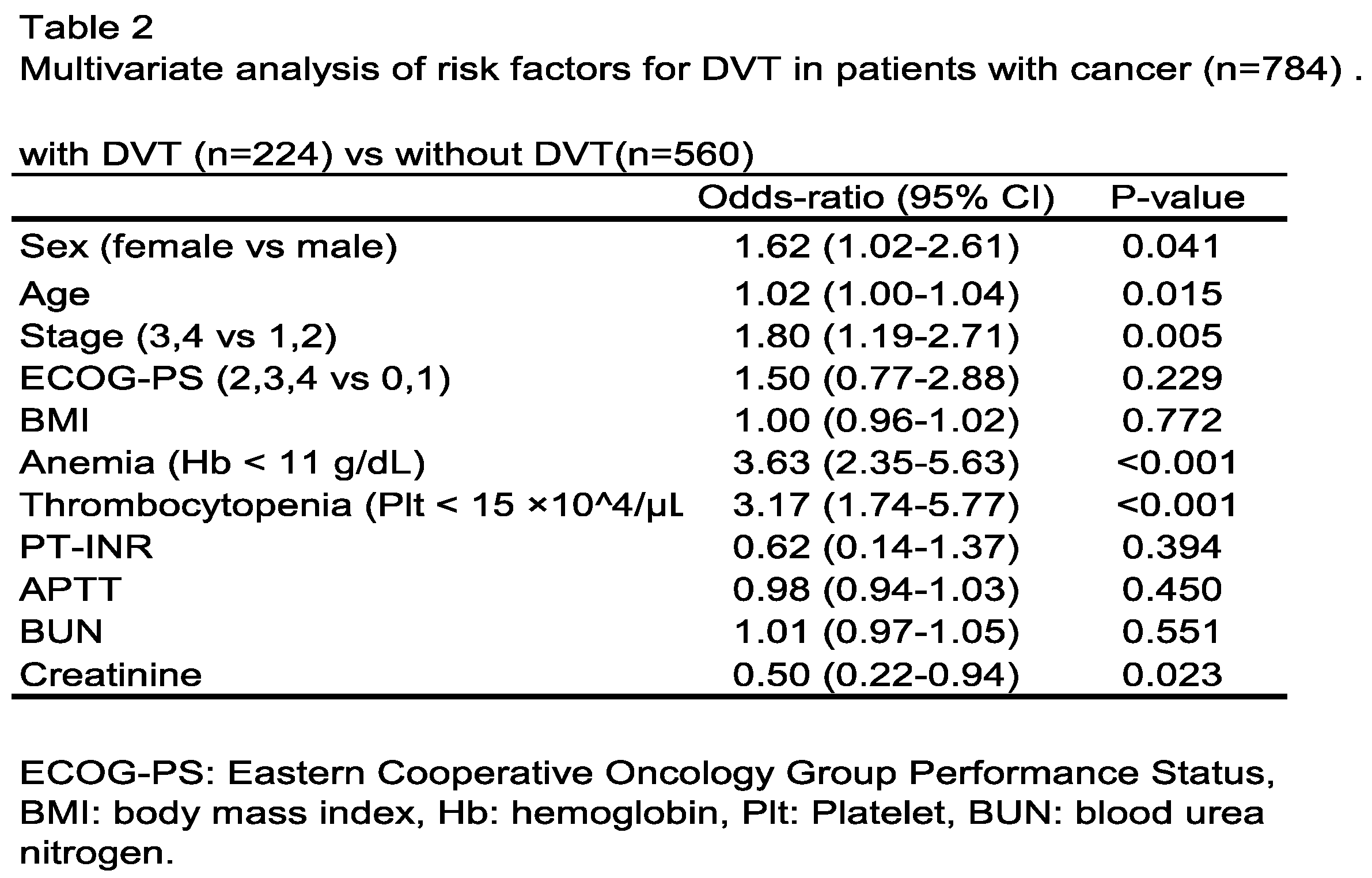

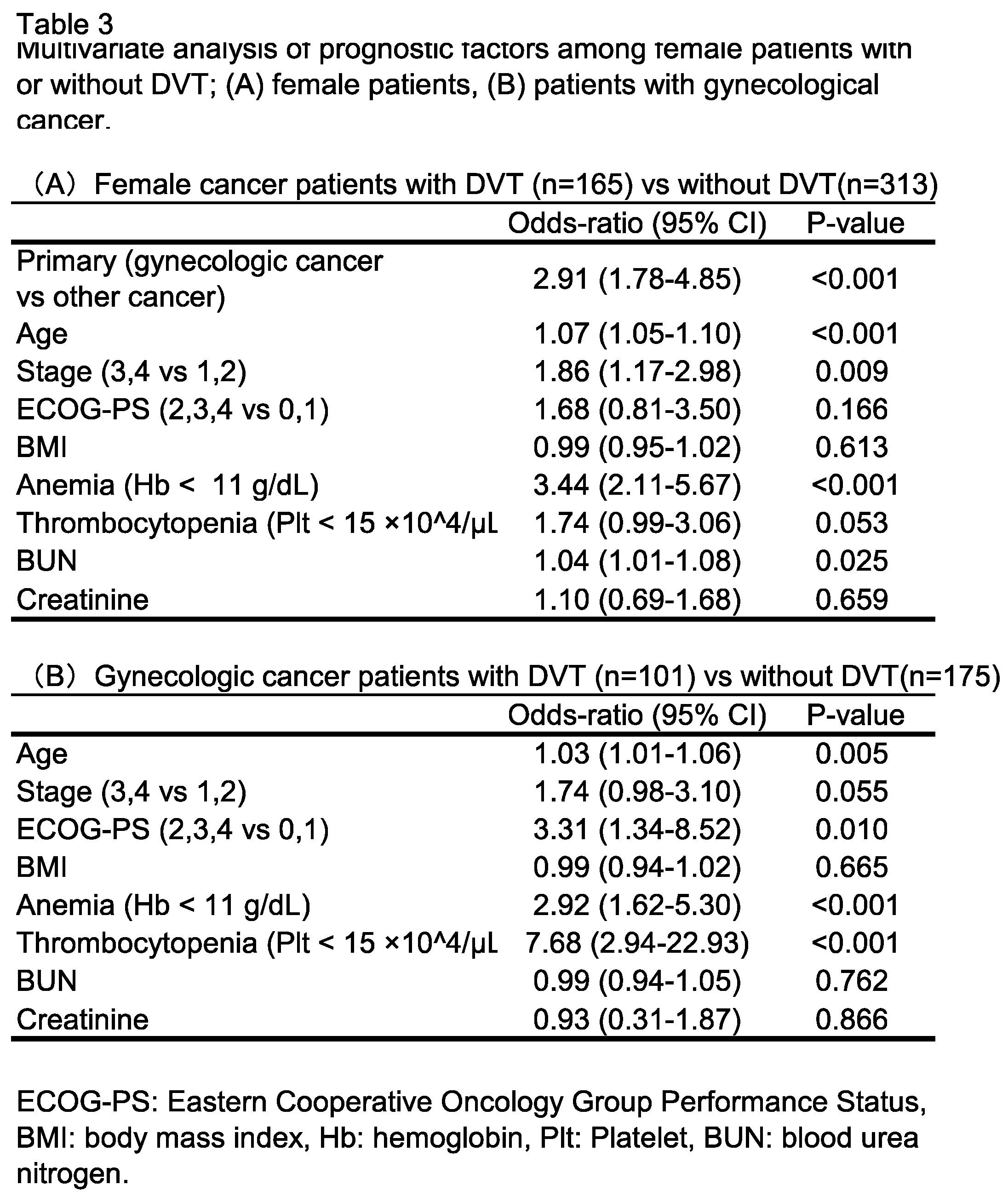

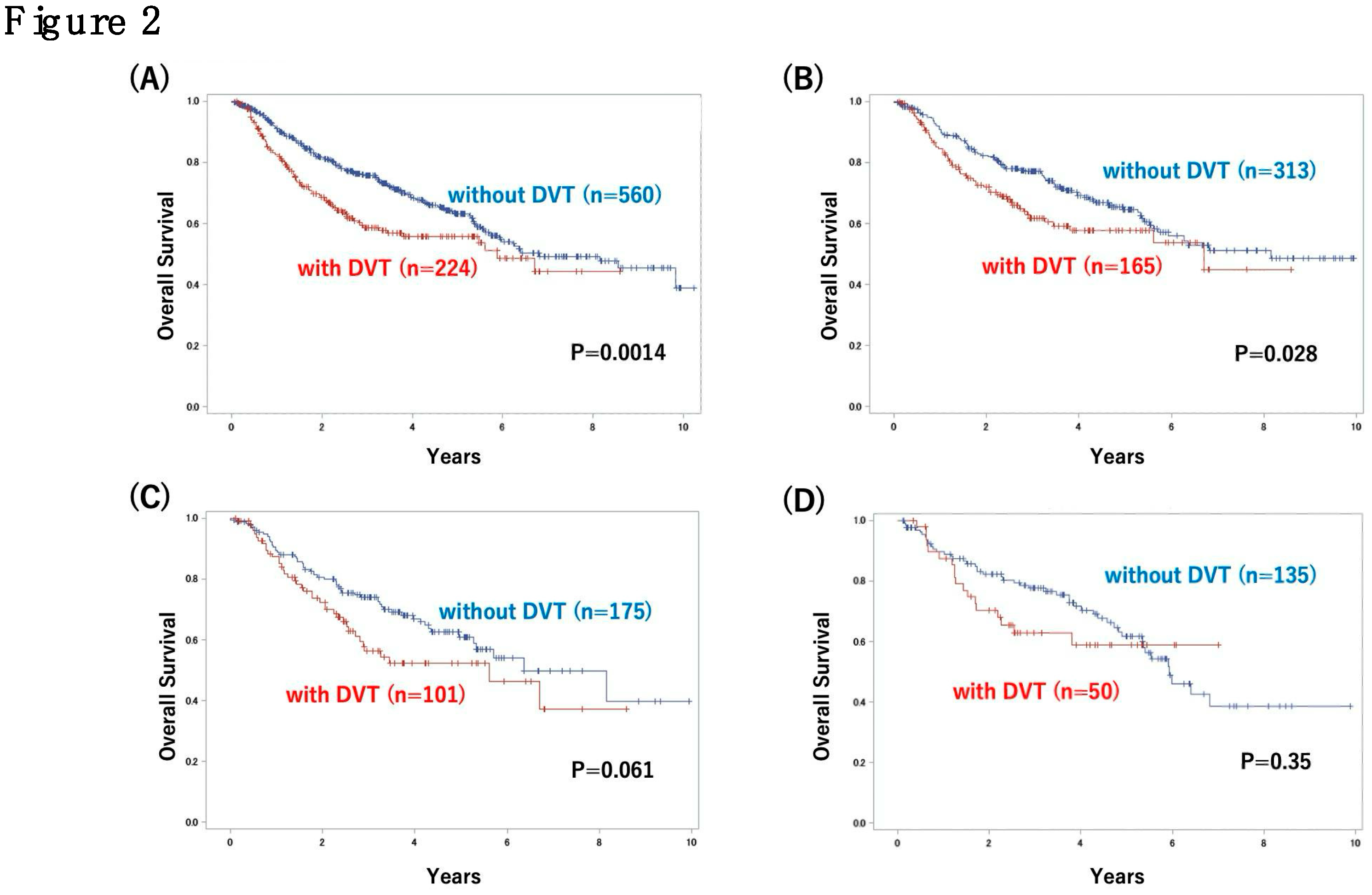

3.2. Analysis of Outcome in Patients with or Without DVT and Risk Factors for DVT

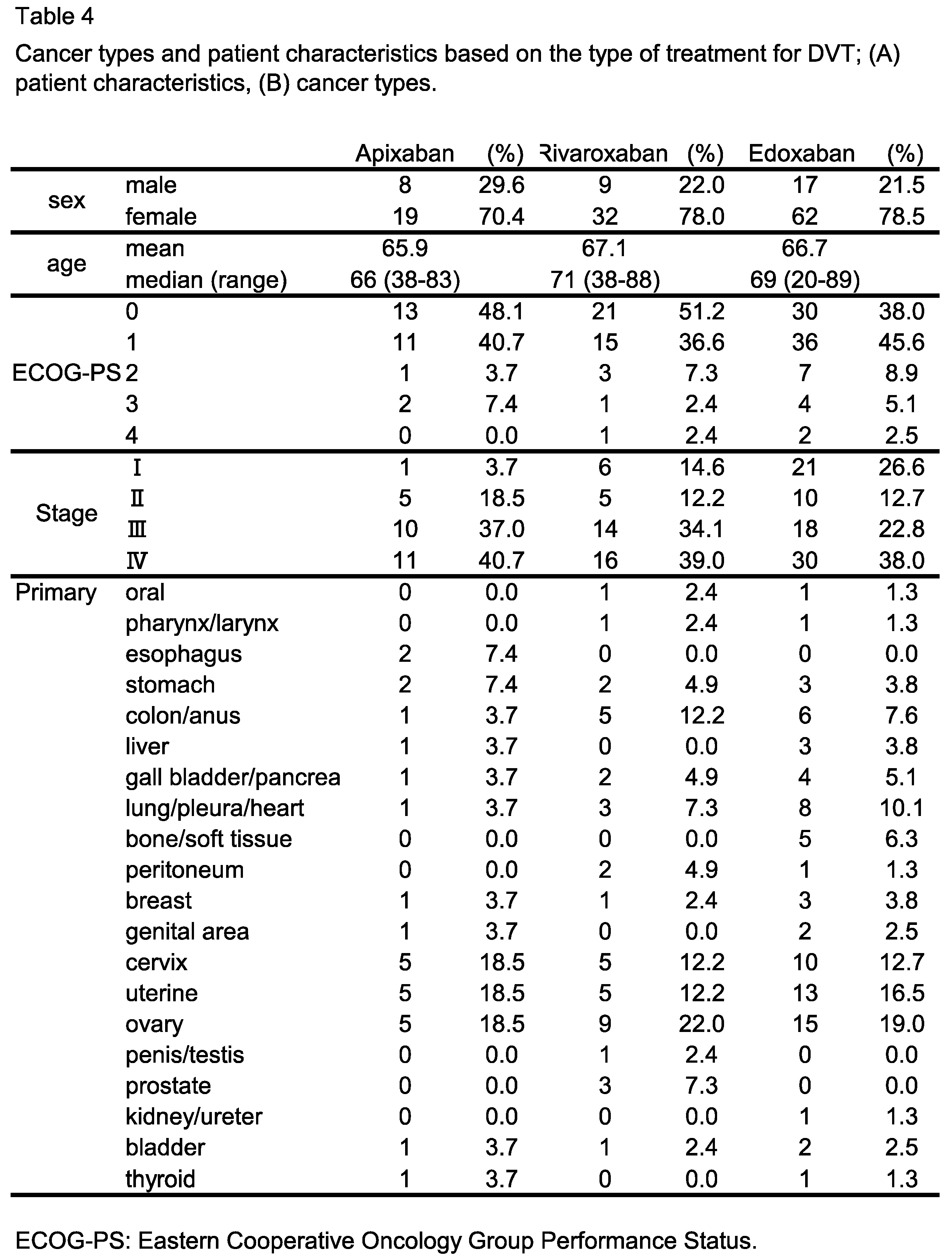

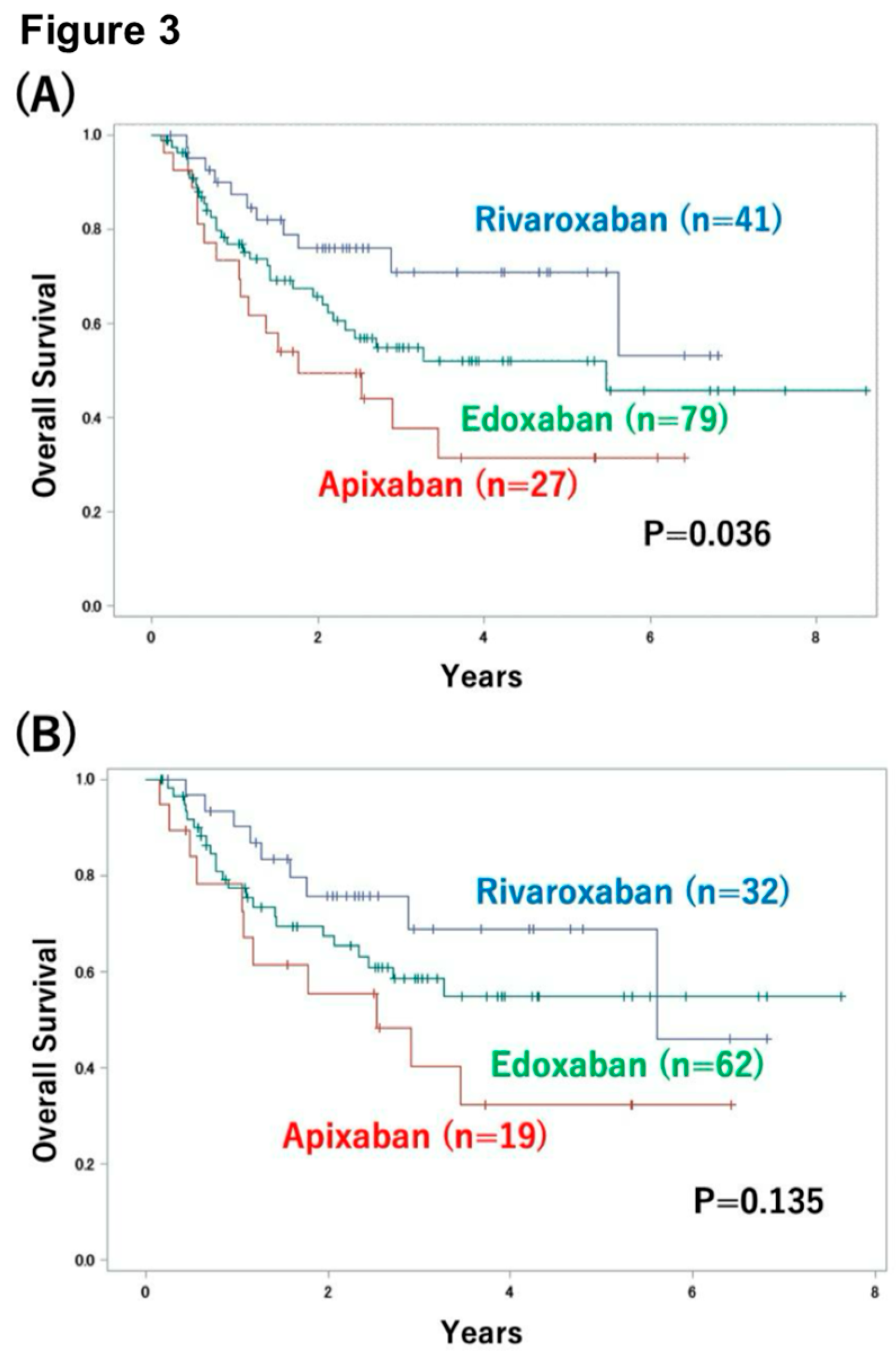

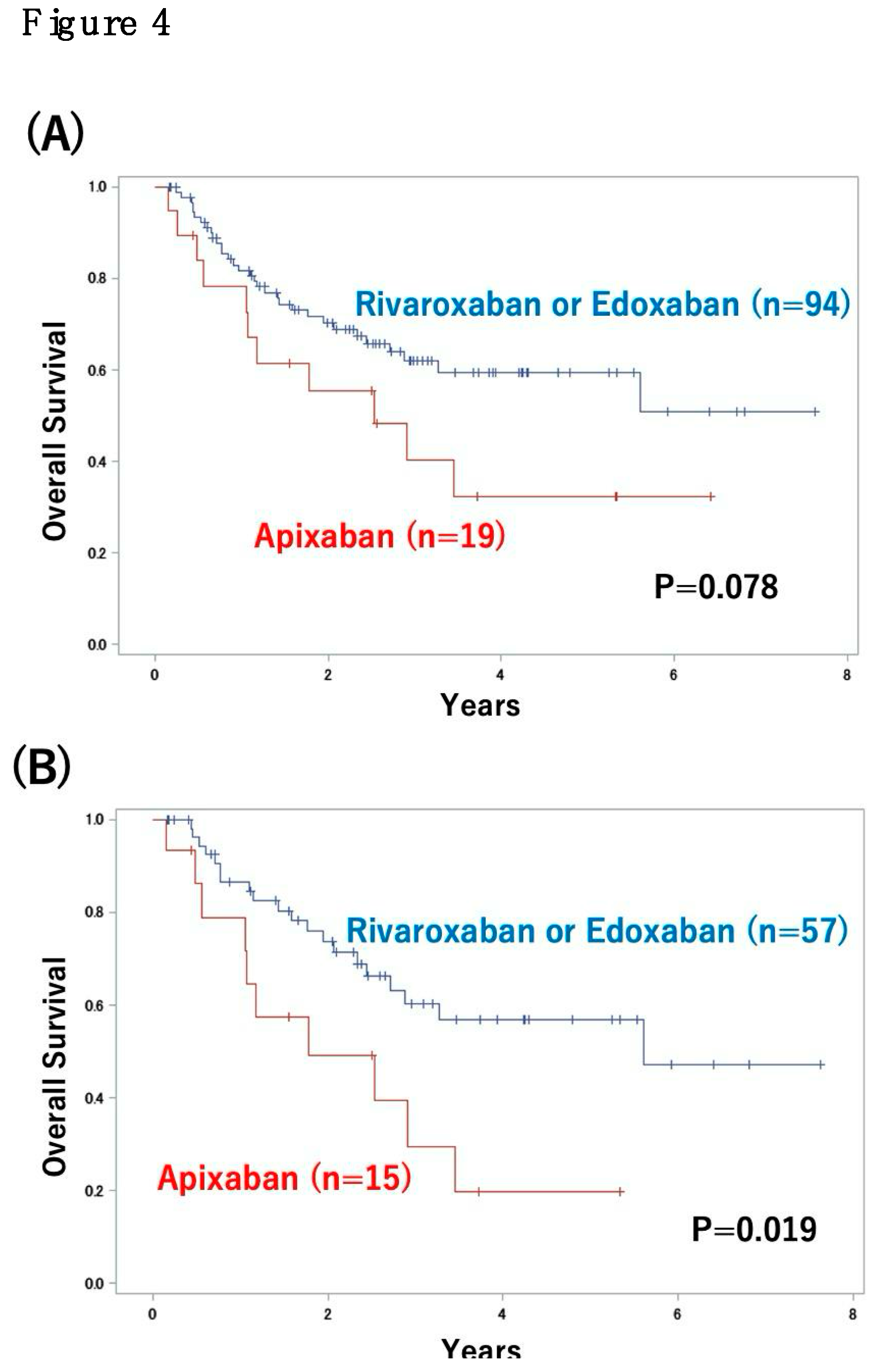

3.3. Impact of DVT Treatment with Oral Anticoagulants on Patient Outcome

4. Discussion

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Competing interests

Funding

Author contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Heit, J.A. Epidemiology of Venous Thromboembolism. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyman, G.H. Venous Thromboembolism in the Patient with Cancer: Focus on Burden of Disease and Benefits of Thromboprophylaxis. Cancer 2011, 117, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandoni, P.; Falanga, A.; Piccioli, A. Cancer and Venous Thromboembolism. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elting, L.S.; Escalante, C.P.; Cooksley, C.; Avritscher, E.B.C.; Kurtin, D.; Hamblin, L.; Khosla, S.G.; Rivera, E. Outcomes and Cost of Deep Venous Thrombosis among Patients with Cancer. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; Culakova, E.; Lyman, G.H.; Francis, C.W. Development and Validation of a Predictive Model for Chemotherapy-Associated Thrombosis. Blood 2008, 111, 4902–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Nakamura, F.; Shibata, A.; Emori, Y.; Nishimoto, H. The National Database of Hospital-Based Cancer Registries: A Nationwide Infrastructure to Support Evidence-Based Cancer Care and Cancer Control Policy in Japan. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 44, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pung, L.; Moorin, R.; Trevithick, R.; Taylor, K.; Chai, K.; Garcia Gewerc, C.; Ha, N.; Smith, S. Determining Cancer Stage at Diagnosis in Population-Based Cancer Registries: A Rapid Scoping Review. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1039266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisato, T.; Hashiguchi, T.; Sarker, K.P.; Arimura, K.; Asano, M.; Matsuo, K.; Osame, M.; Maruyama, I. Highly Accumulated Platelet Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Coagulant Thrombotic Region. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 1, 2589–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezono, K.; Sarker, K.P.; Kikuchi, H.; Nasu, M.; Kitajima, I.; Maruyama, I. Bioactivity of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Trapped in Fibrin Clots: Production of IL-6 and IL-8 in Monocytes by Fibrin Clots. Haemostasis 2001, 31, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, J.; Kaider, A.; Marosi, C.; Prager, G.W.; Eichelberger, B.; Assinger, A.; Pabinger, I.; Panzer, S.; Ay, C. Decreased Platelet Reactivity in Patients with Cancer Is Associated with High Risk of Venous Thromboembolism and Poor Prognosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenmotsu, H.; Notsu, A.; Mori, K.; Omori, S.; Tsushima, T.; Satake, Y.; Miki, Y.; Abe, M.; Ogiku, M.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Cumulative Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Advanced Cancer in Prospective Observational Study. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temraz, S.; Moukalled, N.; Gerotziafas, G.T.; Elalamy, I.; Jara-Palomares, L.; Charafeddine, M.; Taher, A. Association between Radiotherapy and Risk of Cancer Associated Venous Thromboembolism: A Sub-Analysis of the COMPASS-CAT Study. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, K.; Moeini, A.; Machida, H.; Fullerton, M.E.; Shabalova, A.; Brunette, L.L.; Roman, L.D. Significance of Venous Thromboembolism in Women with Cervical Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Tsuruga, T.; Taguchi, A.; Tanikawa, M.; Sone, K.; Mori-Uchino, M.; Iriyama, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Hiraike, O.; Hirota, Y.; et al. Comorbid Thrombosis as an Adverse Prognostic Factor in Patients with Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma Regardless of Staging. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Tsurimoto, S.; Tada, T.; Yamamura, R.; Katoh, H.; Noji, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Fujino, S. Venous Thromboembolism in Japanese Patients with Gynecologic Cancer. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2023, 29, 10760296221124120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Marshall, A.; Thirlwall, J.; Chapman, O.; Lokare, A.; Hill, C.; Hale, D.; Dunn, J.A.; Lyman, G.H.; Hutchinson, C.; et al. Comparison of an Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2017–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Es, N.; Coppens, M.; Schulman, S.; Middeldorp, S.; Büller, H.R. Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared with Vitamin K Antagonists for Acute Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence from Phase 3 Trials. Blood 2014, 124, 1968–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, G.; Buller, H.R.; Cohen, A.; Curto, M.; Gallus, A.S.; Johnson, M.; Masiukiewicz, U.; Pak, R.; Thompson, J.; Raskob, G.E.; et al. Oral Apixaban for the Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EINSTEIN Investigators; Bauersachs, R.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Brenner, B.; Buller, H.R.; Decousus, H.; Gallus, A.S.; Lensing, A.W.; Misselwitz, F.; Prins, M.H.; et al. Oral Rivaroxaban for Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2499–2510. [Google Scholar]

- Hokusai-VTE Investigators; Büller, H.R.; Décousus, H.; Grosso, M.A.; Mercuri, M.; Middeldorp, S.; Prins, M.H.; Raskob, G.E.; Schellong, S.M.; Schwocho, L.; et al. Edoxaban versus Warfarin for the Treatment of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, A.; AlQahtani, A.; Rayes, N.H.; AlQahtani, R.; Alkharras, R.; Alghethber, H. Direct Oral Anticoagulant: Review Article. J Family Med Prim Care 2022, 11, 4180–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Lv, M.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S.; Chen, M.; Fang, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Qian, J.; Xu, W.; Guan, C.; et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 10407–10420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oride, T.; Sawada, K.; Shimizu, A.; Kinose, Y.; Takiuchi, T.; Kodama, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Kobayashi, E.; Nakatani, E.; Kimura, T. Clinical Trial Assessing the Safety of Edoxaban with Concomitant Chemotherapy in Patients with Gynecological Cancer-Associated Thrombosis (EGCAT Study). Thromb. J. 2023, 21, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odajima, S.; Seki, T.; Kato, S.; Tomita, K.; Shoburu, Y.; Suzuki, E.; Takenaka, M.; Saito, M.; Takano, H.; Yamada, K.; et al. Efficacy of Edoxaban for the Treatment of Gynecological Cancer-Associated Venous Thromboembolism: Analysis of Japanese Real-World Data. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 33, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Jo, K.W.; Huh, J.W.; Oh, Y.M.; Lee, J.S. Comparison of Rivaroxaban and Dalteparin for the Long-Term Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Gynecologic Cancers. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, M.; Abou-Nassar, K.; Mallick, R.; Tagalakis, V.; Shivakumar, S.; Schattner, A.; Kuruvilla, P.; Hill, D.; Spadafora, S.; Marquis, K.; et al. Apixaban to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).