Introduction

Venous thromboembolic events (VTEs) is a major complication in cancer patients, contributing to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare burden [

1]. The prothrombotic state associated with malignancy is primarily driven by tumor-mediated coagulation activation, chemotherapy-induced endothelial injury, and immobility [

2].

Central venous catheters (CVCs), commonly used for chemotherapy administration, further elevate the risk of VTEs due to mechanical vascular irritation and stasis [

3,

4]. Compared with external CVCs, implantable central venous access devices (ICVADs), offer several advantages, including being less visible and more acceptable for the patients, requiring less special care, and lower risk of complications including VTEs, which have markedly improved patients’ quality of life [

5].

However, the reported incidence of VTEs in cancer patients with ICVADs varies widely across the literature, depending on study design, patient population, and methods used to detect thromboembolic events. Most studies focus specifically on catheter-related thrombosis, with incidence rates ranging from 0.3% to 11.5% [

6,

7]. Only a few studies have reported the overall incidence of VTEs, with estimates ranging from 11% to 15% [

8,

9].

Several risk assessment models (RAMs) have been developed to stratify cancer patients based on their risk for VTEs. The Khorana score [

10] remains the most widely validated and utilized model in clinical practice [

11], and endorsed by several clinical practice guidelines [

12,

13]. However, it has shown limited sensitivity in some cancer subtypes and clinical contexts [

14]. More recent models, such as the COMPASS-CAT [

15] and ONCOTEV [

16] scores, have attempted to improve predictive performance by incorporating additional clinical, laboratory, and treatment-related variables. Nevertheless, the utility of these models specifically in patients receiving chemotherapy through ICVADs remains inadequately studied.

Despite the well-recognized thrombotic risk in this setting, the role of prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with ICVADs remains questionable. Clinical trials evaluating routine thromboprophylaxis in cancer patients with CVCs have yielded mixed results, with no clear consensus on efficacy [

17,

18]. The heterogeneity of patient populations, variations in cancer types and stage, and inconsistent risk stratification methods may have contributed to these inconclusive findings.

Given these limitations, our study aims to evaluate the incidence and risk factors for VTEs in a cohort of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy via ICVADs. We also assessed the predictive performance of the Khorana, COMPASS, and ONCOTEV RAMs in this population, with the goal of identifying a model that can reliably guide prophylactic strategies and improve patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Adult patients (≥18 years) with pathologically confirmed diagnosis of solid cancer who had ICVAD inserted, treated, and followed up at our institution between January 2021 and December 2023 were identified. Data were collected from the hospital databases and electronic medical records.

The following variables were recorded: age, sex, cancer type, personal history of VTE, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, smoking history, and treatments administered via the ICVAD. Baseline complete blood count, body mass index (BMI) at the time of ICVAD insertion were documented. Cancer stage was categorized as localized, locally advanced, or metastatic (as defined in the COMAPSS-CAT RAM or as binary classification of localized/locally advanced vs. metastatic) and presence of vascular or lymphatic compression were determined based on the most recent evaluation prior to device insertion. Patients receiving therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulation at the time of ICVAD insertion were excluded. However, those receiving antiplatelet agents were not excluded.

The Khorana and ONCOTEV RAMs were calculated, and patients were categorized into risk groups as previously described [

8,

13,

14]. For the COMPASS-CAT score, all components were retained, including the 3 points assigned for the presence of a CVC, since all patients in our cohort had an ICVAD. Given this uniform presence of a heavily weighted risk factor, we explored the use of ROC curve analysis to identify an optimal cut-off point for risk stratification. However, the ROC curve did not yield a meaningful threshold with acceptable discrimination,

Supplementary Figure S1. Therefore, patients were categorized into low-risk (score ≤9) and high-risk (score >9) groups. No routine imaging for screening of VTE was performed. VTE diagnosis was based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by radiological imaging - Doppler ultrasound for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and computed tomography (CT) angiography for pulmonary embolism (PE) for symptomatic patients.

Patients were followed from the time of ICVAD insertion until death, last follow-up, or up to six months after device removal, whichever occurred later. VTE was defined as any event if diagnosed any time after ICVAD insertion and up to six month after its removal. VTEs were considered ICVAD-related if they occurred in anatomical proximity to the catheter or venous territory affected by the device. Major bleeding, as a complication of anticoagulation, was defined as fatal bleeding and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical organ and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of ≥2.0 g/dL or leading to transfusion of two or more units of red blood cells.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize patients at baseline. Continuous variables were presented as median (range), and categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentages). The cumulative incidence (CI) of VTE was estimated using the Fine and Gray method, accounting for competing risks. Death occurring before the diagnosis of VTE in patients who did not undergo ICVAD removal, or within six months of ICVAD removal without prior VTE, was considered a competing event. Group comparisons of CI were performed using Gray’s test, and independent predictors of VTE were identified using Fine-Gray sub distribution hazard regression. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log rank test. All p-values were two-sided, and values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 446 patients were included in the analysis with a median age of 56 (range: 19-81) years, and almost equal sex distribution. The most common malignancies were colorectal (n=132, 29.6%), gastric cancer (n=116, 26%), pancreatic cancer (n=82, 18.4%), and breast cancer (n=62, 13.9%). 29 (6.5%) received anthracycline-based or hormonal therapy, and 84 patients (18.8%) were treated with novel therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors,

Table 1.

At the time of ICVAD insertion, 136 (30.5%) patients had a localized disease, 63 (14.1%) had locally advanced disease, and 247 (55.4%) had metastatic disease. The median time from initial cancer diagnosis to ICVAD insertion was 1.2 (range: 0.5 – 177) months. Within 30 days prior to ICVAD insertion, 109 patients (24.4%) were hospitalized, and 71 (15.9%) had evidence of vascular or lymphatic compression on imaging. All ICVDs were silicon ports and were inserted into the subclavian vein.

3.2. Venous thromboembolism

VTEs were reported in 82 (18.4%) patients, corresponding to an incidence of 0.46 events per 1000 catheter days (95% CI: 0.36-0.56). Among these, 43 (9.6%) were ICVAD-related (41 upper limb DVT and 2 both upper limb DVT and PE), corresponding to an incidence of 0.19 events per 1000 catheter days (95% CI: 0.13-0.25). Non-ICVAD related VTEs included isolated lower limb DVT in 17 (20.7%), lower limb DVT with PE in 2 patients (2.4%), isolated PE in 11 (13.4%) patients, and 9 patients (2%) had abdominal vein thrombosis: four in the inferior vena cava, three in the splenic veins, one in the hepatic vein, and one involving both the ovarian and renal veins.

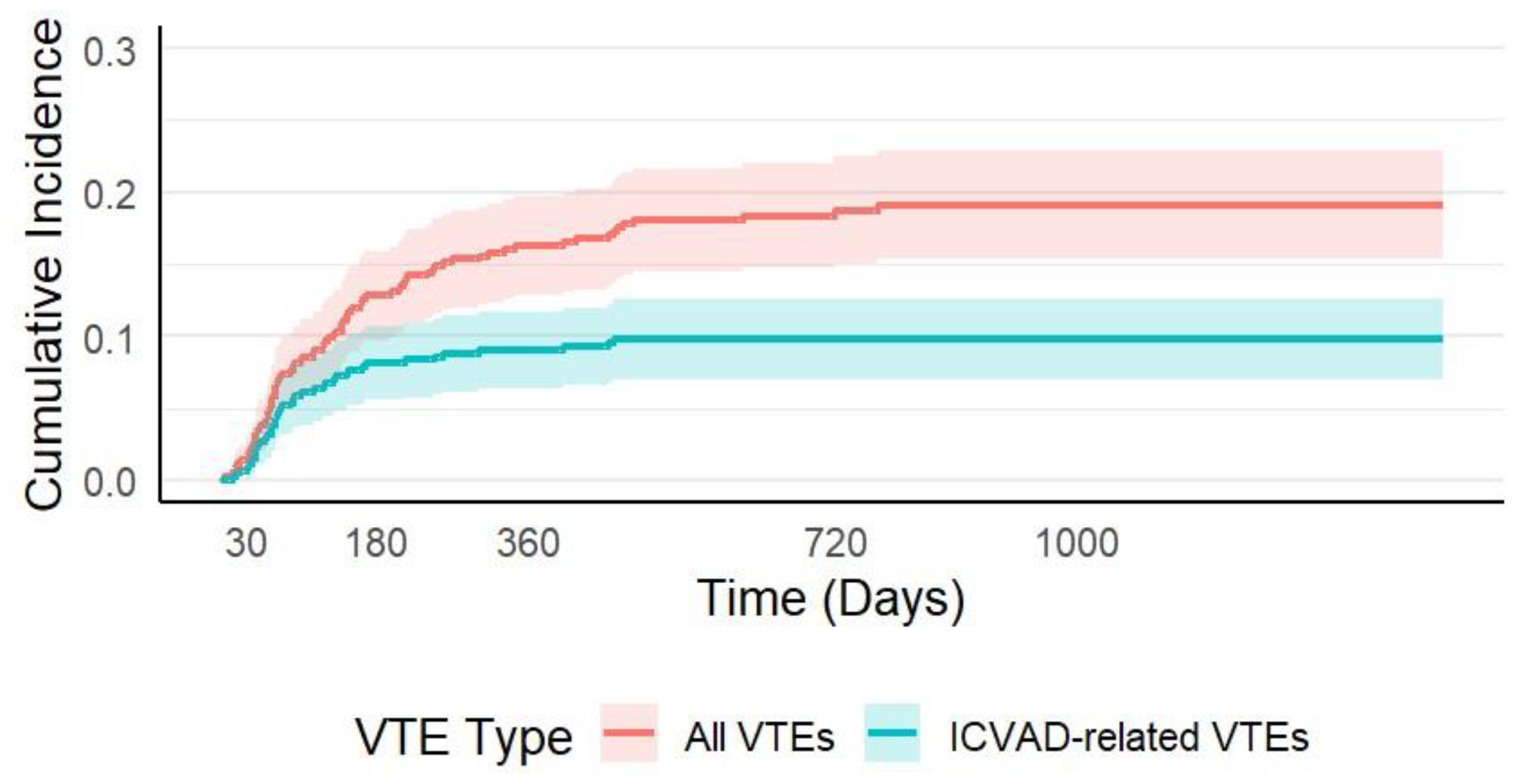

The median time from ICVAD insertion to the diagnosis of any VTE was 117 days (range: 3–768), while the median time to ICVAD-related VTE was shorter, at 68 days (range: 13–459). The CI of VTE progressively increased over time following ICVAD insertion. At 30 days, the CI of VTE was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.02–1.77%), rising to 5.84% (95% CI: 3.66–8.03%) at 90 days, and 8.10% (95% CI: 5.56–10.65%) at 180 days. By 12 months (365 days), the CI reached 9.02% (95% CI: 6.35–11.69%) and continued to increase to 18.4% (95% CI: 14.4–22.2%) at two years. The cumulative incidence of ICVAD-related VTE followed a similar early rise. It was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.02–1.77%) at 30 days, 5.8% (95% CI: 3.66–8.03%) at 90 days, 8.1% (95% CI: 5.56–10.65%) at 180 days, and 9.0% (95% CI: 6.35–11.69%) at 360 days. However, by two years, the cumulative incidence of ICVAD-related VTE was 9.3% (95% CI: 6.55–12.01%),

Figure 1.

In univariate analysis, the CI of VTE was significantly higher in patients with diabetes (1-year 20.7% vs. 14%; p=0.02), metastatic disease (1-year 18.4% vs. 12.6%; p=0.02), white blood cell count (WBC) >11 × 10

9/L (1-year 29.1% vs. 14.4%; p=0.007), and vascular or lymphatic compression (1-year 29.9% vs. 13.1%; p=0.01),

Table 1.

In multivariate analysis, only vascular or lymphatic compression remained independently associated with VTE risk (HR: 2.1, 95%CI 1.3–3.5); p=0.004),

Table 2.

Treatment of VTEs included low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in 54 (65.9%) patients, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in 23 (28%) patients. Five patients (6.1%) did not receive anticoagulation because of bleeding and coagulopathy. The median duration of anticoagulation was 5.2 (range: 1-12) months. Anticoagulation was complicated by bleeding in 10 (12.2%) patients, was major in 3 (3.6%) patients, and one patient developed heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

3.3. Risk Assessment Models

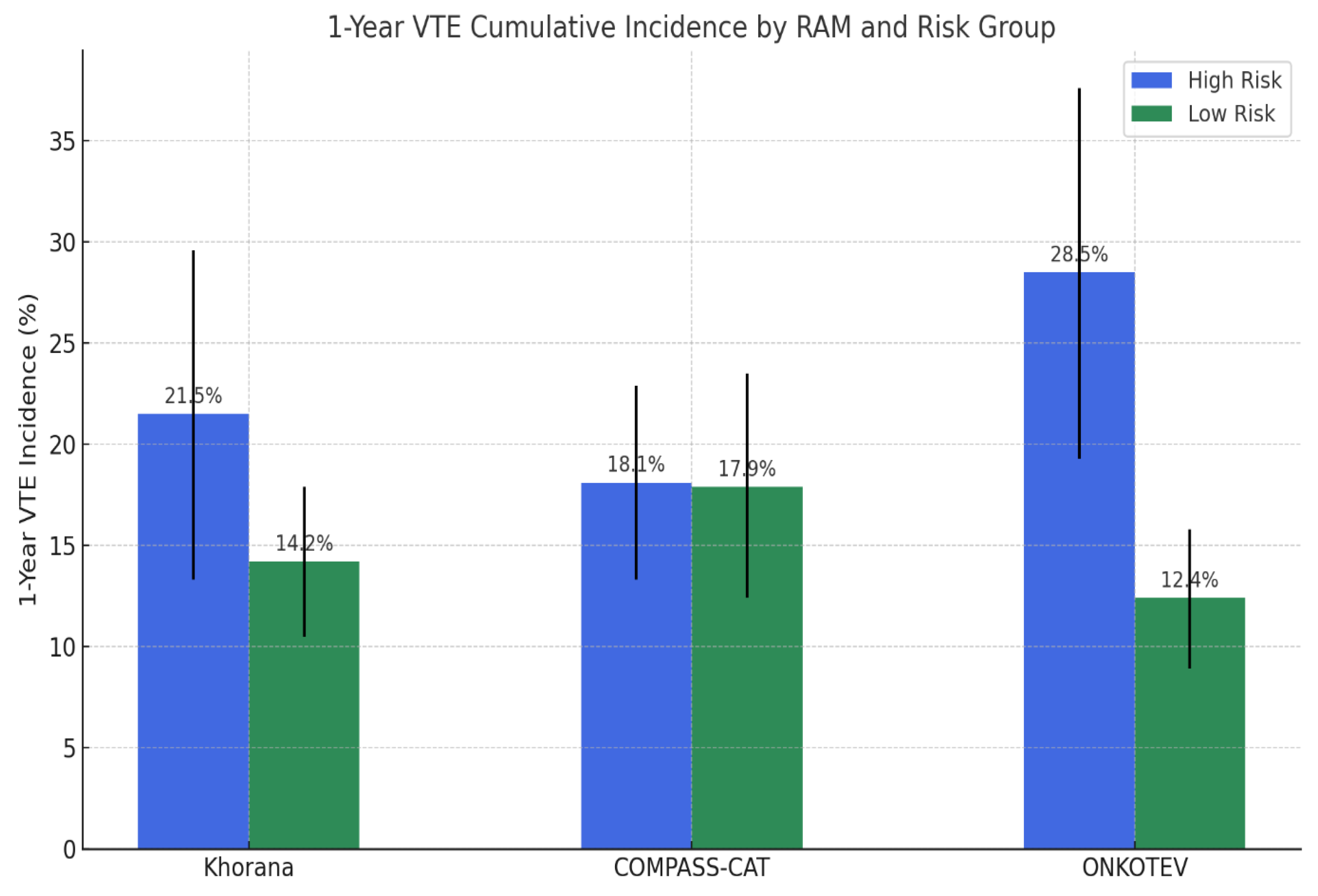

The performance of the Khorana, COMPASS-CAT, and ONKOTEV RAMs in predicting VTEs is summarized in

Figure 2 and

Table 3.

According to the Khorana RAM, 99 patients (22.2%) were classified as high risk (score ≥2), with a 1-year VTE incidence of 21.5% (95% CI: 13.3%–29.6%) compared to 14.2% (95% CI: 10.5%–17.9%) in the low-to-intermediate risk group (p = 0.12). While specificity was relatively high (83.0%), sensitivity was limited (23.2%), and overall accuracy was 69.7%. Only 28% of VTEs occurred in the high-risk category. The COMPASS-CAT RAM categorized 82 patients (18.4%) as high risk (score >9), with a 1-year VTE incidence of 18.1% (95% CI:13.3–22.9%) versus 17.9% (95% CI:12.4–23.5%) in the low-risk group (p= 0.76). Despite showing higher sensitivity (57.3%) and negative predictive value (81.9%), its specificity (43.4%) and overall accuracy (46.0%) was the lowest among the three models. The ONKOTEV score classified 96 patients (21.5%) as high risk (score ≥2), in whom the 1-year VTE incidence was significantly higher at 28.5% (95% CI:19.3%–37.6%), compared to 12.4% (95% CI: 8.9%–15.8%) in the low-risk group (p < 0.001). It demonstrated the best overall performance, with the highest accuracy (74.4%) and specificity (85.7%), and a sensitivity of 33.3%. Moreover, 39% of VTEs occurred in the high risk group.

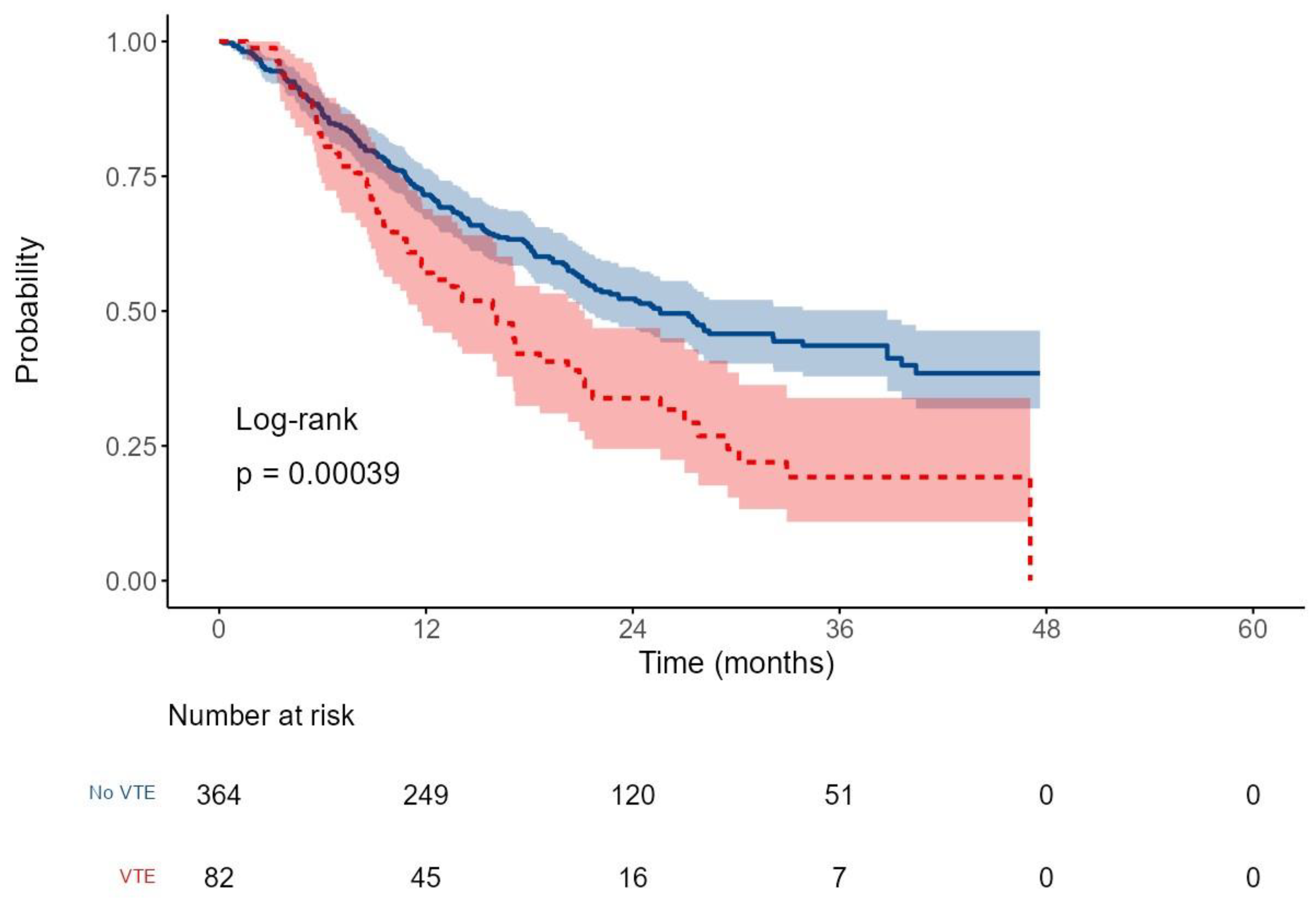

3.4. Survival outcomes

After a median follow-up of 16.5 months (range: 0.2–47.6), the median overall survival (OS) for the entire cohort was 22.2 months (95% CI: 20.2–27.5), with a 2-year OS rate of 48.8%. Patients who developed VTEs had significantly shorter survival, with a median OS of 16.1 months (95% CI: 11.5–21.2), compared to 25.6 months (95% CI: 21.3–38.8) in those without VTE. The corresponding 2-year OS rates were 33.8% versus 52.3%, respectively (HR: 1.7, p < 0.001;

Figure 3).

In the univariate analysis, several additional variables showed significant associations with OS, including history of DM (2-year OS 39% vs 52.3%, p=0.02), low body mass index (BMI) (p< 0.0001), metastatic disease (2-year OS 28.6% vs 74.2%, p<0.001), vascular compression (2-year OS 26.4% vs 52.9%, p<0.001), and use of novel therapy (2-year OS 65.3% vs 45.3%, p=0.049),

Supplementary Table S1.

In the multivariate analysis, metastatic disease (HR 4.6, p<0.001), use of novel therapy (HR 0.47, p<0.001), BMI (HR 0.94, p<0.001), and VTEs (HR 1.39, p= 0.037), remained statistically significant,

Supplementary Table S2.

4. Discussion

In this retrospective study, cancer patients receiving chemotherapy via ICVADs had a high incidence of VTEs (18.4%), with nearly half (9.6%) being device related. Among the three evaluated RAMs, only the ONKOTEV score demonstrated significant discriminatory ability to identify patients at higher risk. Additionally, the occurrence of VTE was independently associated with worse OS.

Limited number of studies have specifically reported the overall incidence of VTEs in cancer patients with ICVADs. In the ONCOCIP trial, the overall VTE rate was 13.1% [

8], and Hohl Moinat et al. reported a one-year incidence of 15.3% [

9]. The relatively higher rate observed in our cohort (18.4%) likely reflects the predominance of gastrointestinal malignancies, particularly gastric and pancreatic cancers, which are known to be associated with elevated thrombotic risk [

8]. The 9.6% incidence of ICVAD-related thrombosis also falls at the higher end of reported ranges (0.3%–11.5%) [

20,

21,

22,

23], indicating the clinically significant burden of these devices on development of VTEs in our cohort.

The Khorana RAM showed limited ability to identify high-risk patients. Although VTEs incidence increased with higher scores (from 14.2 % in low-risk to 21.5% in high-risk), the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.12), and only 28% of VTEs occurred in the high-risk group. These findings align with a meta-analysis by Mulder et al., which reported that only 23.4% of VTEs occurred in patients classified as high risk [

24]. The score’s limited utility in our population may be explained by its underperformance in gastrointestinal cancers [

24,

25] and that it does not include catheter-related factors.

The COMPASS-CAT score demonstrated a relatively higher sensitivity (57.3%) and negative predictive value (81.9%), but it had lower specificity (43.4%) and the lowest overall accuracy among the three models (46.0%). Although the COMPASS-CAT model classified a similar proportion of patients as high risk (18.2%) compared to Khorana (22.2%) and ONKOTEV (21.5%), its performance remained inferior. This indicates that the model’s limited predictive utility in our cohort is not related to the size of the high-risk group but rather to inadequate risk discrimination and limited relevance of certain score components. The score was originally developed and validated in a population primarily composed of patients with breast, colorectal, and lung cancers [

26,

27], while nearly half of our cohort had gastric or pancreatic malignancies. Moreover, components that are heavily weighted in the score, such as anthracycline and hormonal therapies, were rarely used in our population, further diminishing its applicability.

By contrast, the ONKOTEV score demonstrated the best overall performance. It achieved the highest accuracy (74.4%) and specificity (85.7%) among the three models, with moderate sensitivity (33.3%) and a PPV of 39%. These results are consistent with previous validation studies in patients with different types of solid tumors [

28], in pancreatic cancer [

29], and in a recent study where ONKOTEV outperformed the Khorana score in guiding individualized prevention of VTEs in outpatients with cancer [

30]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the ONKOTEV model specifically in patients with ICVADs. Its improved performance likely reflects the inclusion of metastatic disease and vascular or lymphatic compression; two variables significantly associated with VTE in our analysis. However, the model missed a substantial proportion of VTEs, suggesting that further refinement is warranted.

An important observation in our study was the timing of VTEs. The cumulative incidence of ICVAD-related VTE plateaued by 6 months (8.1%), whereas overall VTE risk continued to rise, reaching 18.4% by two years. This pattern suggests that catheter-associated thrombosis is predominantly an early complication, while longer-term risk is driven by disease burden and ongoing therapy. These findings support the six-month time-limited approach to prophylaxis implemented in prospective trials like CASSINI [

31] and AVERT [

32] and emphasizing the importance of ongoing individualized risk assessment throughout cancer care.

Although the development of VTEs has been linked to more aggressive tumor biology, advanced stage, and certain cancer therapies [

33], multiple studies have reported an independent association between VTEs and increased mortality. For example, the prospective Scandinavian Thrombosis and Cancer (STAC) study demonstrated a 3.4-fold increase in the risk of death among cancer patients who developed VTEs, regardless of cancer type or severity [

34]. Our findings are consistent with these observations.

However, in the era of novel therapies, the impact of VTEs on survival may vary depending on tumor type, disease stage, and the timing of VTEs occurrence. A recent meta-analysis, for instance, found no significant association between cancer-related VTEs and OS in breast cancer patients [

35], while in pancreatic cancer, only early VTEs (within three months of diagnosis) were associated with worse survival outcomes [

36]. Individualized risk assessment and additional studies are warranted to clarify the prognostic role of VTEs across different cancer types and treatment settings.

Among patients who developed VTEs, 6.1% did not receive anticoagulation, while 12.2% experienced bleeding complications during treatment, including major bleeding in 3.6%. These rates are comparable to those reported in real-world studies [

13] and highlight the importance of balancing thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks, particularly in patients with gastrointestinal cancers.

Although this study provides one of the few real-world evaluations comparing three RAMs in cancer patients with ICVADs, it has important limitations that include its retrospective nature, potential underreporting of asymptomatic VTEs, and the single-center design, which may limit generalizability.

5. Conclusions

Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy through ICVADs are at increased risk of VTEs, which was independently associated with worse overall survival. Among the evaluated risk models, the ONKOTEV score demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy in this population, although its sensitivity remained limited. Further studies are needed to assess its role in guiding prophylactic anticoagulation strategies and improving outcomes in high-risk patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the COMPASS-CAT score in predicting venous thromboembolism in cancer patients with ICVADs; Table S1: Univariate analysis for overall survival, Table S2: Multivariate analysis for overall survival.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., M.J.A, Z.A, A.Z, and H.A.; methodology: M.M, and H.A; validation, M.M, H.F,M.A, M.E,A.Z, M.A, and T.G.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M, and H.A.; data curation, H.F, M.A, M.E, A.Z, R.H.M. T.G, and M.A; writing—original draft preparation, M.M, Z.A, M.J.A, M.A, and H. A; writing—review and editing, M.M, Z.A, M.J.A, H.F., M.E and H.A; visualization, M.M.; supervision, M.M, and H.A; project administration, H.A; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of King Hussein Cancer Center.

Informed Consent Statement

The waiver of the written informed consent was granted due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Chat GPT 4o for the purposes of language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VTE |

Venous thromboembolic event(s) |

| ICVAD |

Implantable central venous access device |

| DVT |

Deep vein thrombosis |

| PE |

Pulmonary embolism |

| CI |

Cumulative incidence |

| WBC |

White blood cell count |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| LMWH |

Low molecular weight heparin |

| DOAC |

Direct oral anticoagulant |

| RAM |

Risk assessment model |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| PPV |

Positive predictive value |

| NPV |

Negative predictive value |

| CVC |

Central venous catheter |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

References

- Khorana, A.A.; Francis, C.W.; Culakova, E.; Kuderer, N.M.; Lyman, G.H. Thromboembolism is a leading cause of death in cancer patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, J.W.; Doggen, C.J.M.; Osanto, S.; Rosendaal, F.R. Malignancies, Prothrombotic Mutations, and the Risk of Venous Thrombosis. JAMA 2005, 293, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verso, M.; Agnelli, G. Venous Thromboembolism Associated With Long-Term Use of Central Venous Catheters in Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3665–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, V.; Anand, S.; Hickner, A.; Buist, M.; Rogers, M.A.; Saint, S.; A Flanders, S. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with peripherally inserted central catheters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, I.; Pulvirenti, E.; Mannino, M.; Toro, A. Increased Use of Percutaneous Technique for Totally Implantable Venous Access Devices. Is It Real Progress? A 27-Year Comprehensive Review on Early Complications. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Soh, K.L.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Huang, J. Risk of VTE associated with PORTs and PICCs in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb. Res. 2022, 213, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prandoni, P.; Campello, E. Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: Risk Factors and Prevention. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 47, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decousus, H.; Bourmaud, A.; Fournel, P.; Bertoletti, L.; Labruyère, C.; Presles, E.; Merah, A.; Laporte, S.; Stefani, L.; Del Piano, F.; et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis in patients with implanted ports: a prospective multicenter French cohort study (ONCOCIP). Blood 2018, 132, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moinat, C.H.; Périard, D.; Grueber, A.; Hayoz, D.; Magnin, J.-L.; André, P.; Kung, M.; Betticher, D.C. Predictors of Venous Thromboembolic Events Associated with Central Venous Port Insertion in Cancer Patients. J. Oncol. 2014, 2014, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; Culakova, E.; Lyman, G.H.; Francis, C.W. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood 2008, 111, 4902–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, F.I.; Candeloro, M.; Kamphuisen, P.W.; Di Nisio, M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Guman, N.; Smit, K.; Büller, H.R.; van Es, N. The Khorana score for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, N.S.; Khorana, A.A.; Kuderer, N.M.; Bohlke, K.; Lee, A.Y.; Arcelus, J.I.; Wong, S.L.; Balaban, E.P.; Flowers, C.R.; Francis, C.W.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 496–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farge, D.; Frere, C.; Connors, J.M.; Ay, C.; A Khorana, A.; Munoz, A.; Brenner, B.; Kakkar, A.; Rafii, H.; Solymoss, S.; et al. 2019 international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e566–e581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Es, N.; Di Nisio, M.; Cesarman, G.; Kleinjan, A.; Otten, H.-M.; Mahé, I.; Wilts, I.T.; Twint, D.C.; Porreca, E.; Arrieta, O.; et al. Comparison of risk prediction scores for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a prospective cohort study. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerotziafas, G.T.; Taher, A.; Abdel-Razeq, H.; AboElnazar, E.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; El Shemmari, S.; Larsen, A.K.; Elalamy, I.; on behalf of the COMPASS–CAT Working Group. A Predictive Score for Thrombosis Associated with Breast, Colorectal, Lung, or Ovarian Cancer: The Prospective COMPASS–Cancer-Associated Thrombosis Study. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Deng, L.; Lin, K.; Shi, X.; Zhaoliang, S.; Wang, Y. Febuxostat attenuates paroxysmal atrial fibrillation-induced regional endothelial dysfunction. Thromb. Res. 2017, 149, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthaus, M.; Kretzschmar, A.; Kröning, H.; Biakhov, M.; Irwin, D.; Marschner, N.; Slabber, C.; Fountzilas, G.; Garin, A.; Abecasis, N.G.F.; et al. Dalteparin for prevention of catheter-related complications in cancer patients with central venous catheters: final results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 17, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verso, M.; Agnelli, G.; Bertoglio, S.; Di Somma, F.C.; Paoletti, F.; Ageno, W.; Bazzan, M.; Parise, P.; Quintavalla, R.; Naglieri, E.; et al. Enoxaparin for the Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism Associated With Central Vein Catheter: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Study in Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4057–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, W.; Brown, C.; Wang, T.-F.; Tagalakis, V.; Shivakumar, S.; Ciuffini, L.A.; Mallick, R.; Wells, P.S.; Carrier, M. Efficacy and safety of apixaban for primary prevention of thromboembolism in patients with cancer and a central venous catheter: A subgroup analysis of the AVERT Trial. Thromb. Res. 2022, 216, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, A.; Bull, L.; Kinzie, M.; Andresen, M. Central catheter-associated deep vein thrombosis in cancer: clinical course, prophylaxis, treatment. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piran, S.; Ngo, V.; McDiarmid, S.; Le Gal, G.; Petrcich, W.; Carrier, M. Incidence and risk factors of symptomatic venous thromboembolism related to implanted ports in cancer patients. Thromb. Res. 2013, 133, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surov, A.; Jordan, K.; Buerke, M.; Arnold, D.; John, E.; Spielmann, R.-P.; Behrmann, C. Port Catheter Insufficiency: Incidence and Clinical-Radiological Correlations. Onkologie 2008, 31, 4–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knebel, P.; Lopez-Benitez, R.; Fischer, L.; Radeleff, B.A.; Stampfl, U.; Bruckner, T.; Hennes, R.; Kieser, M.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. Insertion of Totally Implantable Venous Access Devices. Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, F.I.; Candeloro, M.; Kamphuisen, P.W.; Di Nisio, M.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Guman, N.; Smit, K.; Büller, H.R.; van Es, N. The Khorana score for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overvad, T.F.; Ording, A.G.; Nielsen, P.B.; Skjøth, F.; Albertsen, I.E.; Noble, S.; Vistisen, A.K.; Gade, I.L.; Severinsen, M.T.; Piazza, G.; et al. Validation of the Khorana score for predicting venous thromboembolism in 40 218 patients with cancer initiating chemotherapy. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 2967–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Eldredge, J.B.; Anand, L.N.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, M.; Nourabadi, S.; Rosenberg, D.J. External Validation of a Venous Thromboembolic Risk Score for Cancer Outpatients with Solid Tumors: The COMPASS-CAT Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment Model. Oncol. 2020, 25, e1083–e1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladić, N.; Englisch, C.; Berger, J.M.; Moik, F.; Berghoff, A.S.; Preusser, M.; Pabinger, I.; Ay, C. Validation of Risk Assessment Models for Venous Thromboembolism in Cancer Patients Receiving Systemic Therapies. Blood Adv. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, C.A.; Knoedler, M.; Hall, M.; Arcopinto, M.; Bagnardi, V.; Gervaso, L.; Pellicori, S.; Spada, F.; Zampino, M.G.; Ravenda, P.S.; et al. Validation of the ONKOTEV Risk Prediction Model for Venous Thromboembolism in Outpatients With Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230010–e230010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godinho, J.; Casa-Nova, M.; Moreira-Pinto, J.; Simões, P.; Branco, F.P.; Leal-Costa, L.L.; Faria, A.; Lopes, F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Passos-Coelho, J.L. ONKOTEV Score as a Predictive Tool for Thromboembolic Events in Pancreatic Cancer—A Retrospective Analysis. Oncol. 2019, 25, e284–e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, C.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Hozo, I.; Lordick, F.; Bagnardi, V.; Frassoni, S.; Gervaso, L.; Fazio, N. Comparison of Khorana vs. ONKOTEV predictive score to individualize anticoagulant prophylaxis in outpatients with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 209, 114234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A.; Soff, G.A.; Kakkar, A.K.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; Riess, H.; Wun, T.; Streiff, M.B.; Garcia, D.A.; Liebman, H.A.; Belani, C.P.; et al. Rivaroxaban for Thromboprophylaxis in High-Risk Ambulatory Patients with Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, M.; Abou-Nassar, K.; Mallick, R.; Tagalakis, V.; Shivakumar, S.; Schattner, A.; Kuruvilla, P.; Hill, D.; Spadafora, S.; Marquis, K.; et al. Apixaban to Prevent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A. Venous thromboembolism and prognosis in cancer. Thromb. Res. 2010, 125, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crobach, M.J.T.; Anijs, R.J.S.; Brækkan, S.K.; Severinsen, M.T.; Hammerstrøm, J.; Skille, H.; Kristensen, S.R.; Paulsen, B.; Tjønneland, A.; Versteeg, H.H.; et al. Survival after cancer-related venous thrombosis: the Scandinavian Thrombosis and Cancer Study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 4072–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, U.T.; Walker, A.J.; Baig, S.; Card, T.R.; Kirwan, C.C.; Grainge, M.J. Venous thromboembolism and mortality in breast cancer: cohort study with systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K.; Duan, R.; Wu, Y. Prognostic value of venous thromboembolism in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1331706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).