Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

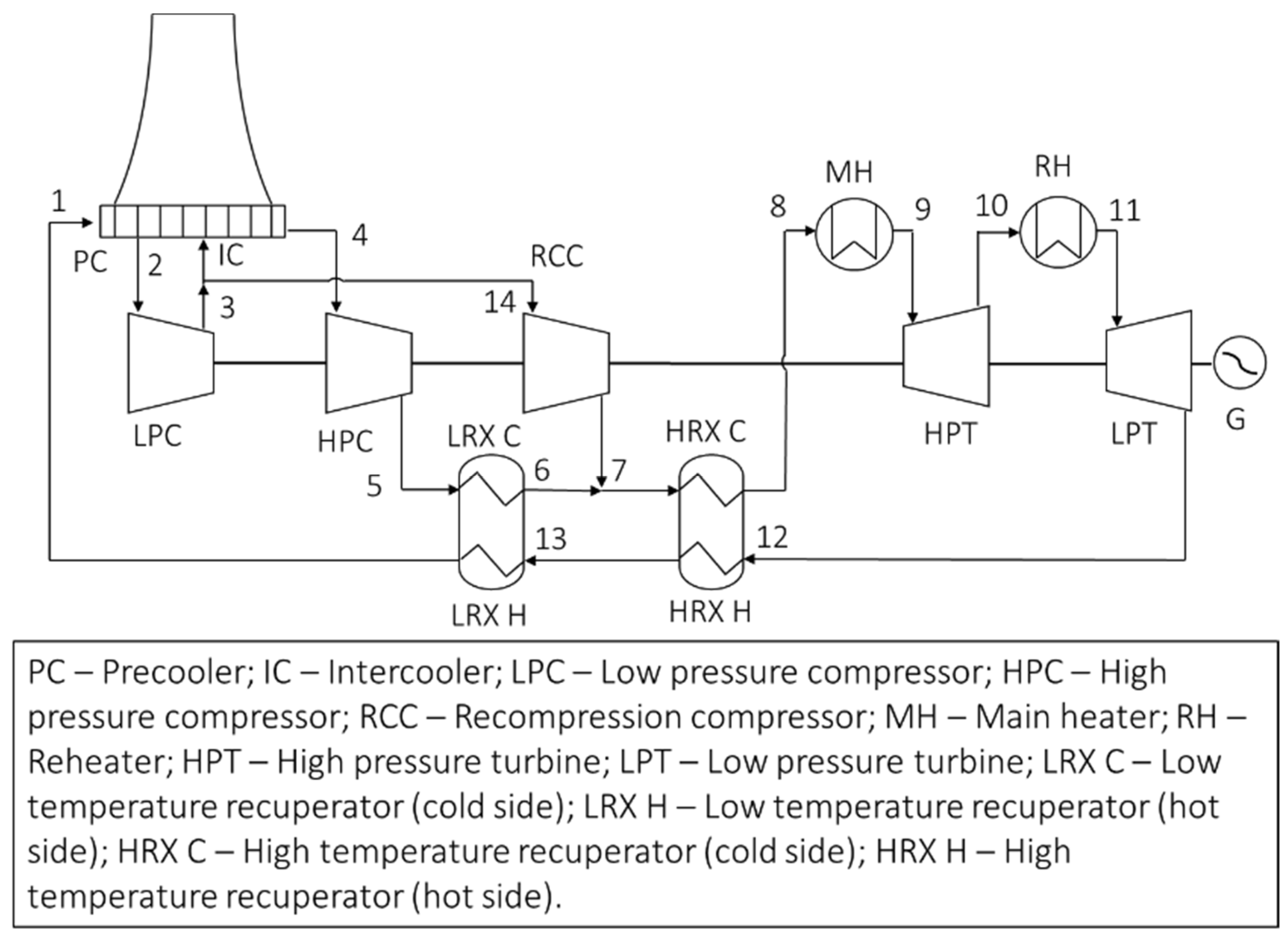

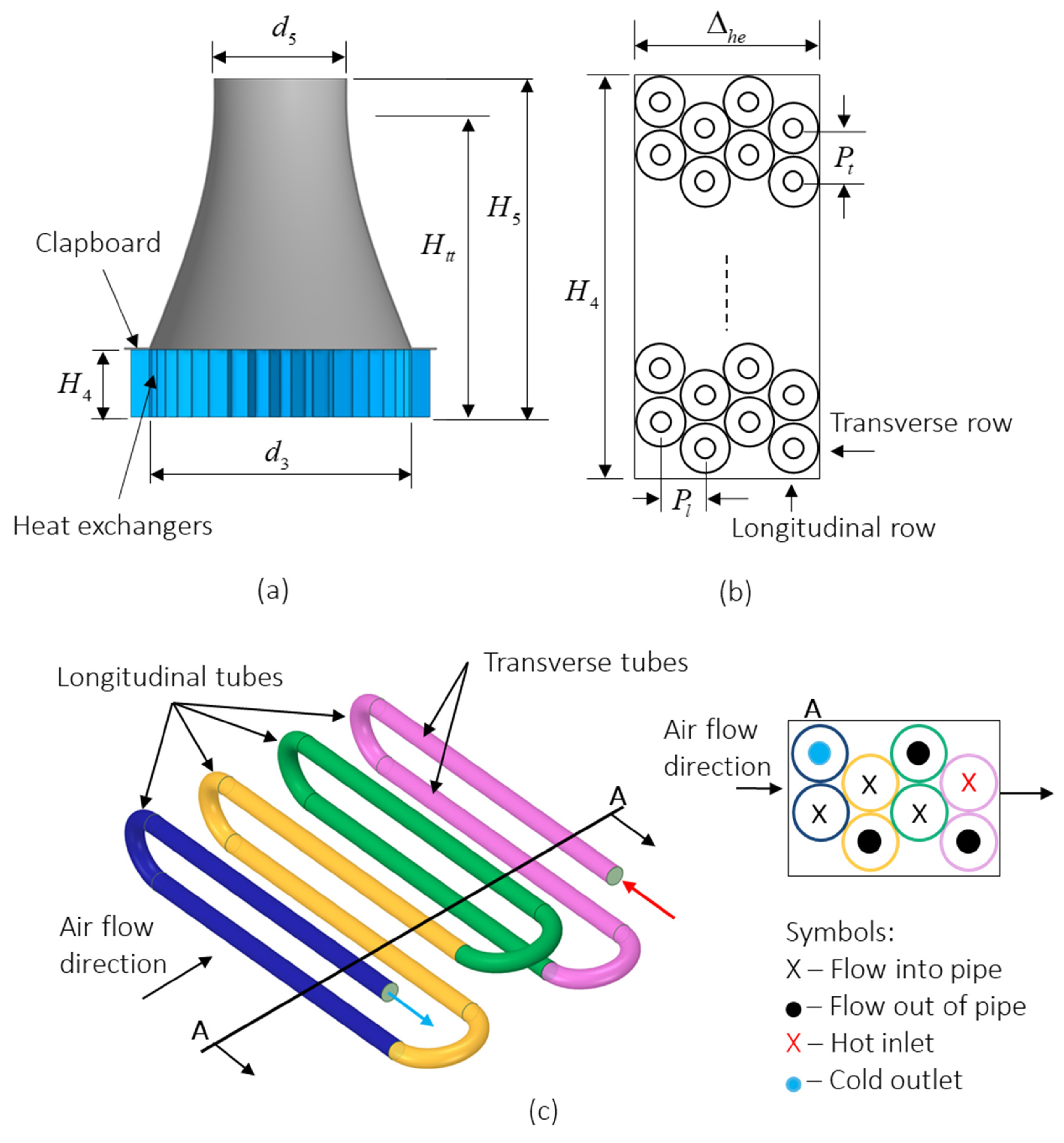

2. Case Study: Power Cycle and System Geometry

3. Materials and Methods

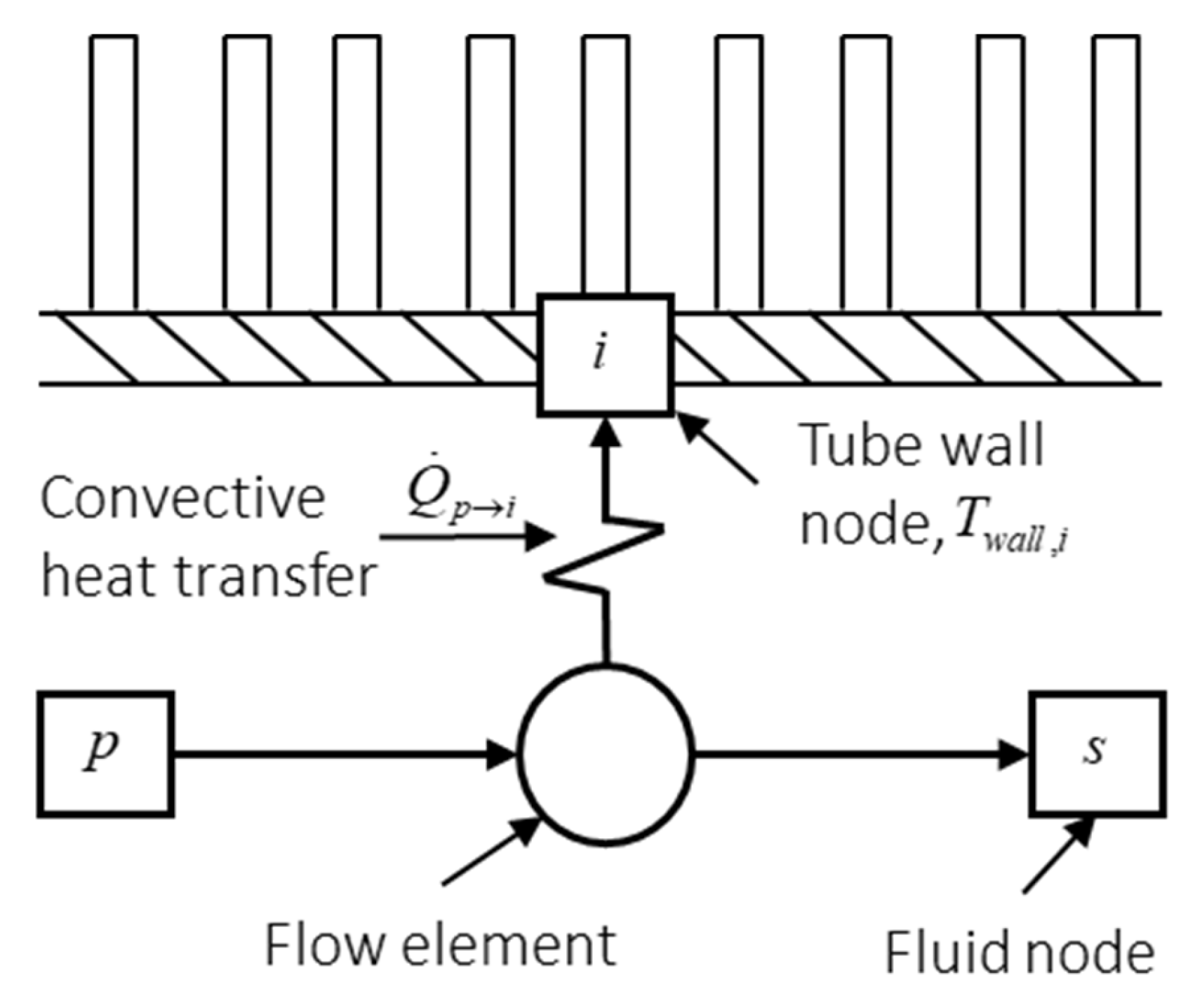

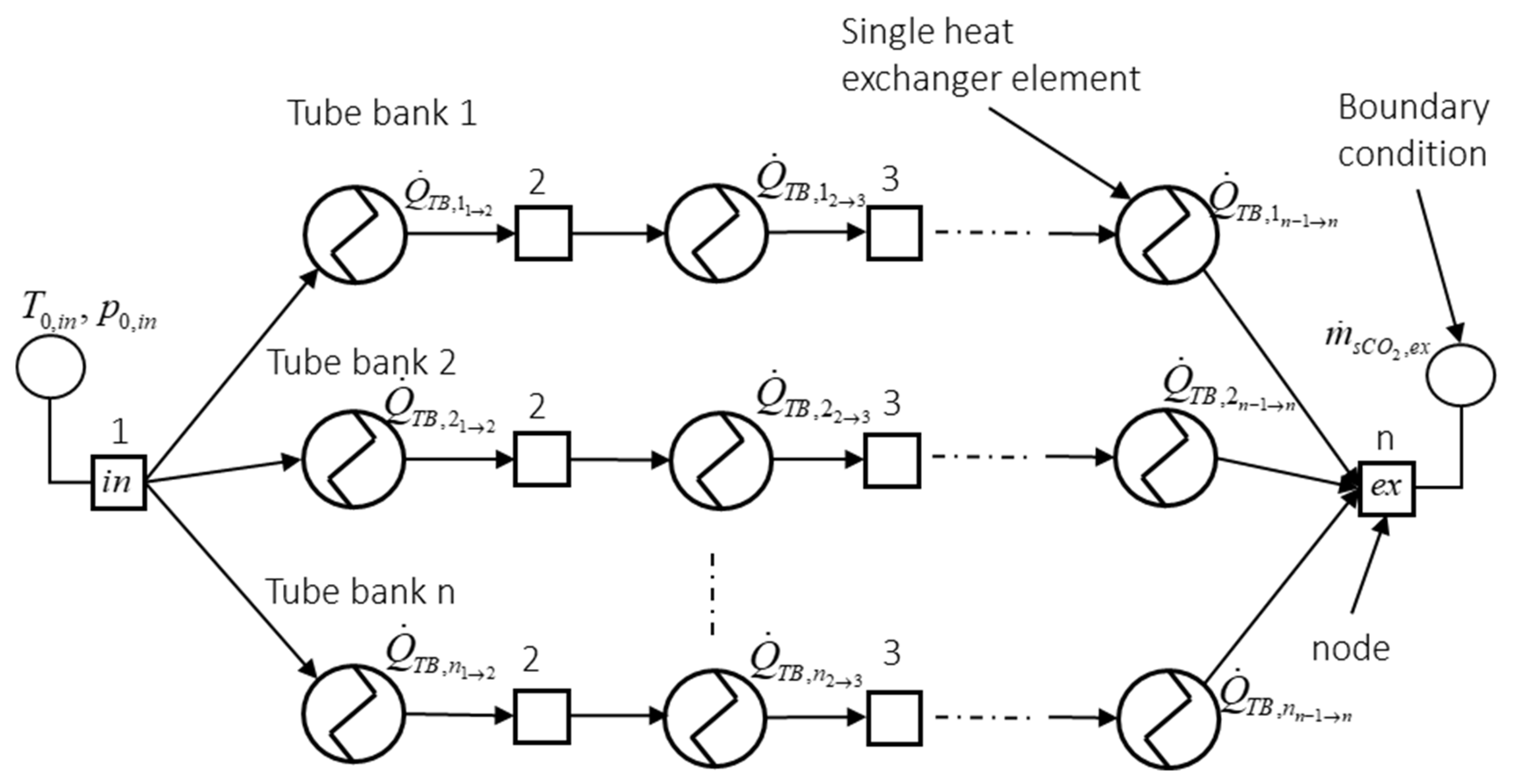

3.1. sCO2-Side Process-Level Modelling

3.1.1. Governing Equations

3.1.2. Component Characteristics

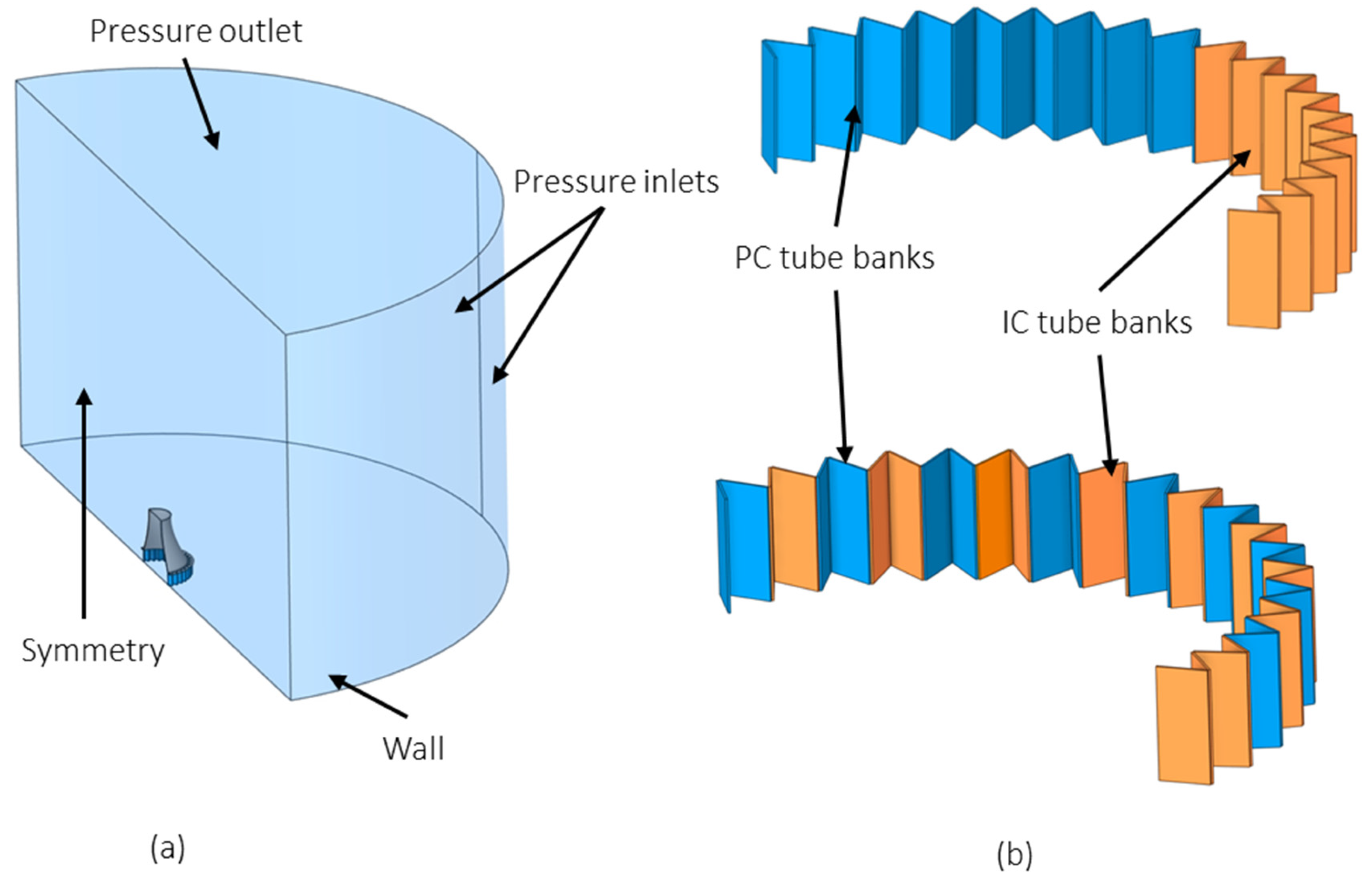

3.2. Air-Side CFD Modelling

3.2.1. Transport Equations

3.2.2. Turbulence Modelling

3.2.3. Atmospheric Conditions

3.2.4. Porous Media Heat Exchanger

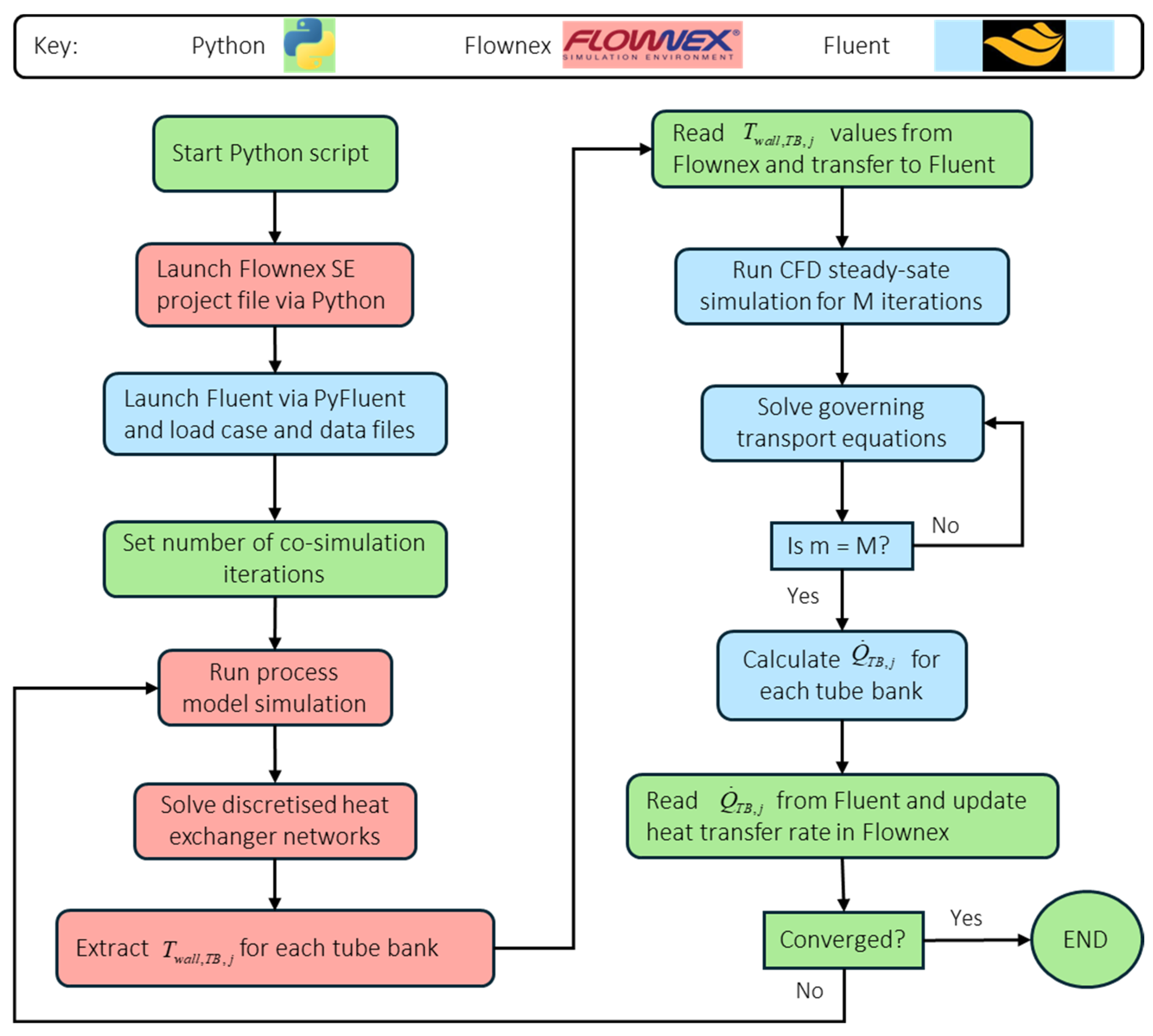

4. Model Development

4.1. Coupling of Simulation Codes

4.2. Process-Model

4.3. Air-Side CFD Model

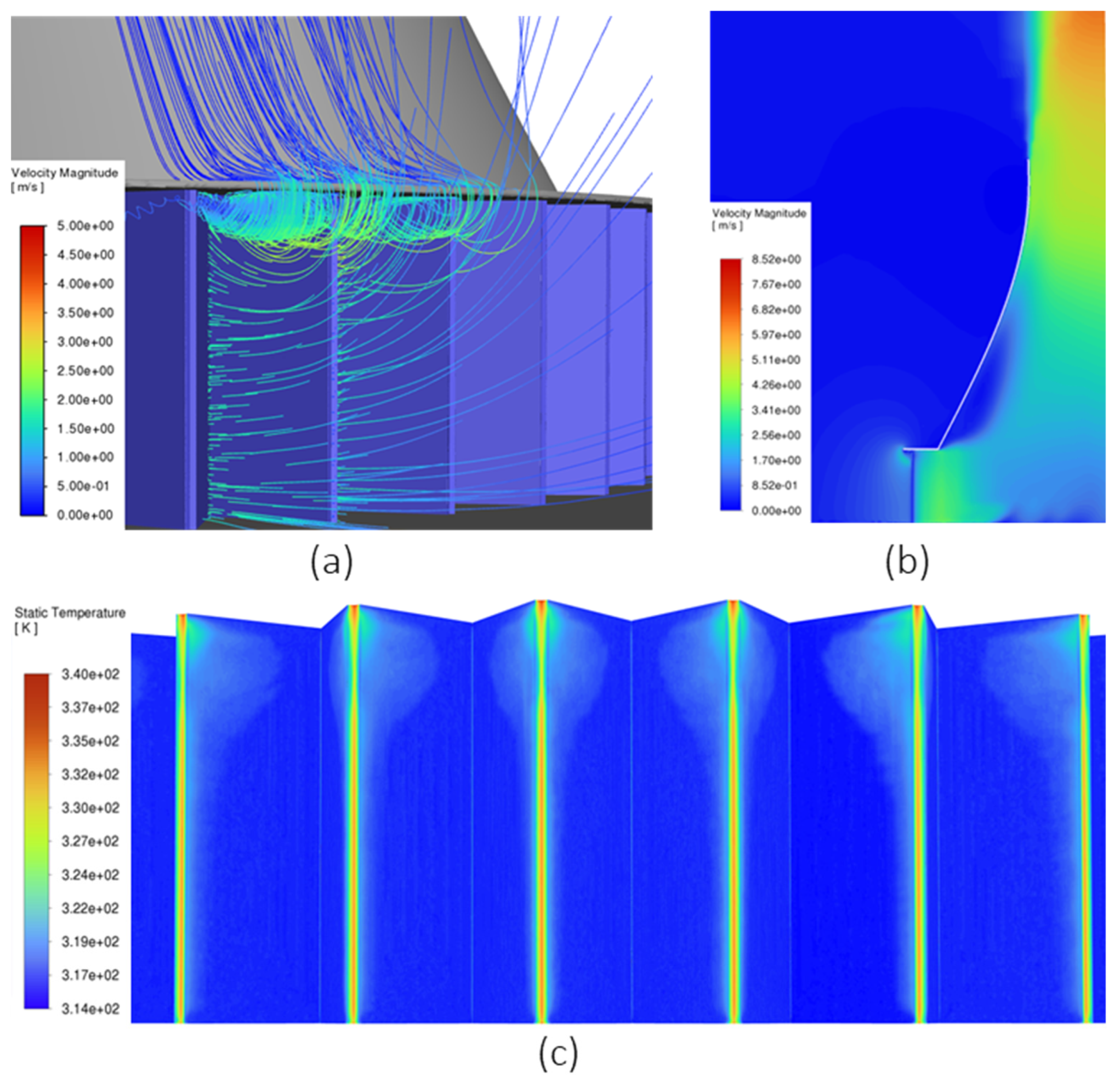

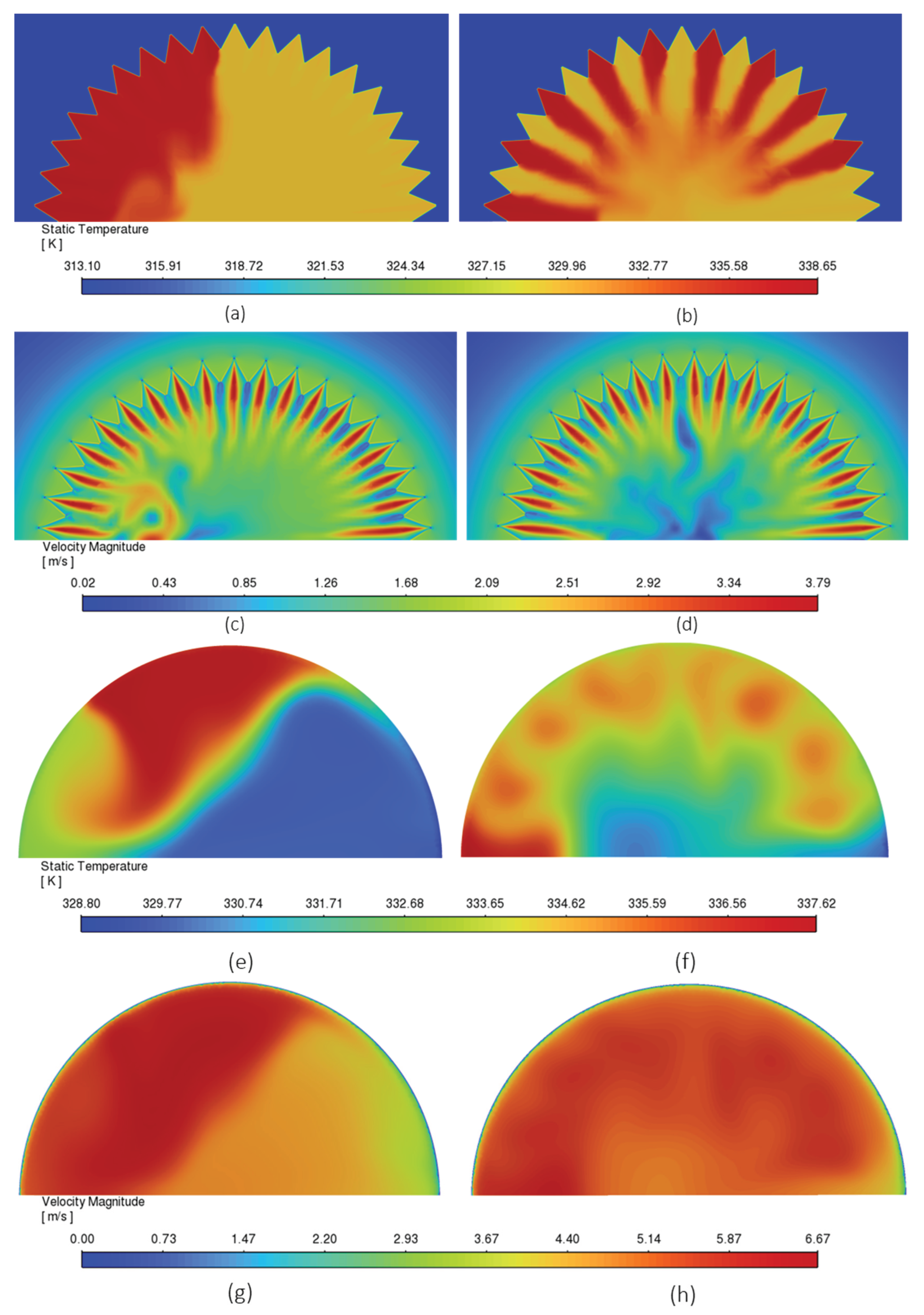

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Mesh Sensitivity and Uncertainty

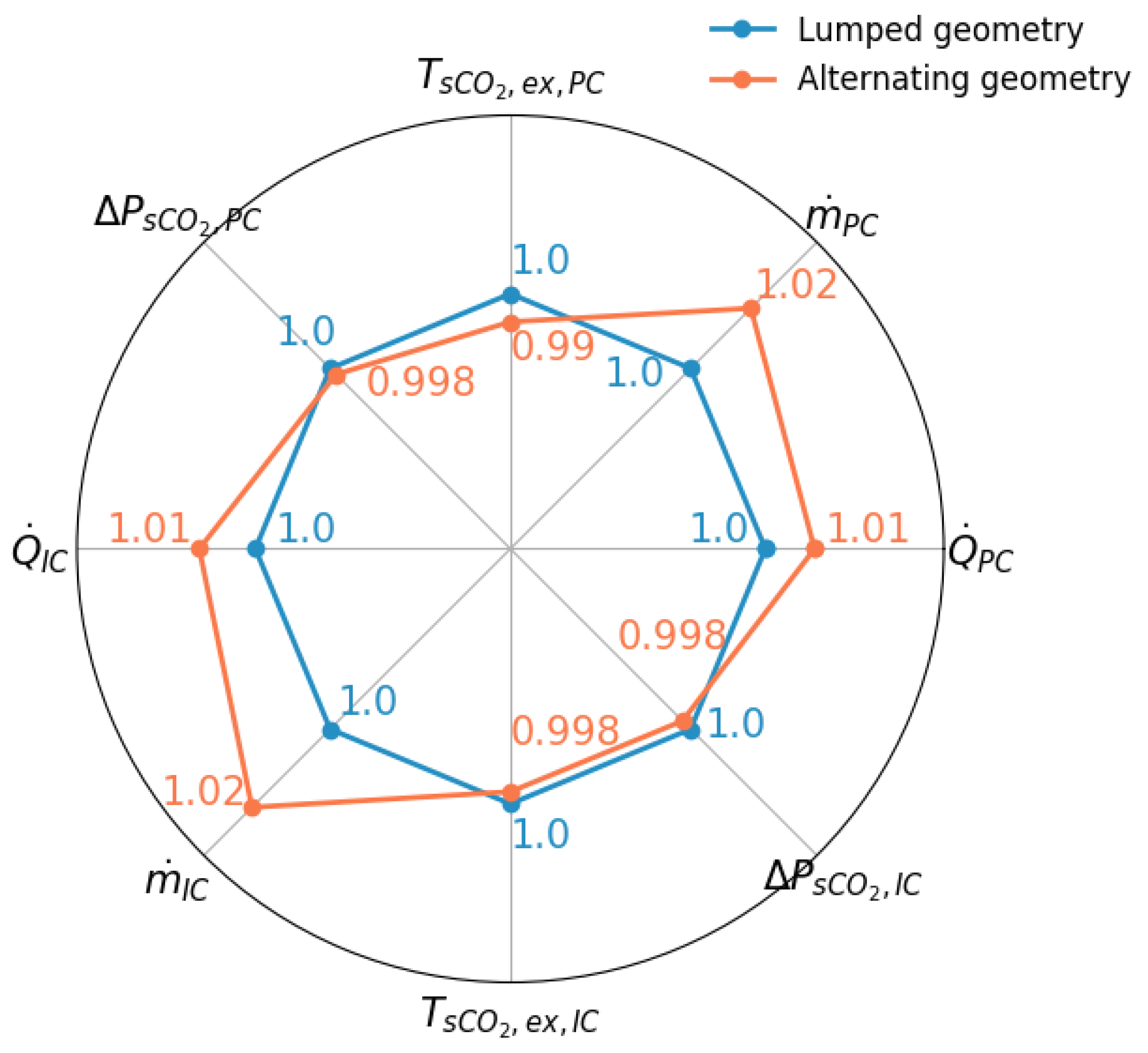

5.2. System Performance

6. Conclusions

References

- C. McGregor, J. P. Pretorius, A. Attieh, and J. Hoffmann, Techno-economic assessment of electricity generation from a medium-scale CSP-PV hybrid plant using long-duration storage, in SolarPACES Conference Proceedings, 2023, vol. 2.

- C. A. Pan and F. Dinter, Combination of PV and central receiver CSP plants for base load power generation in South Africa, Solar Energy, vol. 146, pp. 379-388, 2017.

- A. Boretti and S. Castelletto, Cost and performance of CSP and PV plants of capacity above 100 MW operating in the United States of America, Renewable Energy Focus, vol. 39, pp. 90-98, 2021.

- F. Crespi, G. Gavagnin, D. Sánchez, and G. S. Martínez, Supercritical carbon dioxide cycles for power generation: A review, Applied Energy, vol. 195, pp. 152-183, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Conboy, M. D. Carlson, and G. E. Rochau, Dry-cooled supercritical CO2 power for advanced nuclear reactors, Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, vol. 137, no. 1, p. 012901, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Njoku and O. E. Diemuodeke, Techno-economic comparison of wet and dry cooling systems for combined cycle power plants in different climatic zones, Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 227, p. 113610, 2021.

- S. Duniam, I. Jahn, K. Hooman, Y. Lu, and A. Veeraragavan, Comaprison of direct and indirect cooling tower of the sCO2 Brayton cycle for concentrated solar power plants, Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 130, pp. 1070-1080, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ehsan, Z. Guan, A. Klimenko, and X. Wang, Design and comparison of direct and indirect cooling system for 25 MW solar power plant operated with supercritical CO2 cycle, Energy conversion and management, vol. 168, pp. 611-628, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Lock, K. Hooman, and G. Zhiqiang, A detailed model of direct dry-cooling for the supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton power cycle, Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 163, p. 114390, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang et al., Numerical study on cooling heat transfer of turbulent supercritical CO2 in large horizontal tubes, International journal of heat and mass transfer, vol. 126, pp. 1002-1019, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Z. Guan, H. Gurgenci, K. Hooman, A. Veeraragavan, and X. Kang, Computational investigations of heat transfer to supercritical CO2 in a large horizontal tube, Energy conversion and management, vol. 157, pp. 536-548, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. H. van Niekerk, J. P. Pretorius, and R. Laubscher, Thermofluid network simulation of a natural draft direct dry cooling system for a 50MWe sCO2 power cycle for a CSP application in 6th Edition of the European Conference on Supercritical CO2 (sCO2) for Energy Systems: April 09-11,2025, Delft, Netherlands, Conference Proceedings of the European sCO2 Conference, pp. 68-78. [CrossRef]

- W. Strydom, “Natural Draft Direct Dry Cooling System Performance at Various Application Scales Under Steady and Transient Conditions,” Ph.D., Stellenbosch University, 2024.

- W. Strydom, J. P. Pretorius, and J. E. Hoffmann, Natural draft direct dry cooling system performance at various application scales under windless and windy conditions, Applied Thermal Engineering, p. 123181, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kong, W. Wang, L. Yang, X. Du, and Y. Yang, Thermo-flow performances of natural draft direct dry cooling system at ambient winds, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 116, pp. 173-184, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kong, W. Wang, Y. Yang, X. Du, and Y. Yang, Annularly arranged air-cooled condenser to improve cooling efficiency of natural draft direct dry cooling system, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, vol. 118, pp. 587-601, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kong, W. Wang, Y. Yang, X. Du, and Y. Yang, Wind leading to improve cooling performance of natural draft air-cooled condenser, Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 136, pp. 63-83, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Kröger, Air-cooled Heat Exchangers and Cooling Towers. Tulsa Oklahoma: Pennwell Corp, 2004.

- C. F. du Sart, P. Rousseau, and R. Laubscher, Comparing the partial cooling and recompression cycles for a 50 MWe sCO2 CSP plant using detailed recuperator models, Renewable Energy, vol. 222, p. 119980, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Turchi, Z. Ma, T. W. Neises, and M. J. Wagner, Thermodynamic study of advanced supercritical carbon dioxide power cycles for concentrating solar power systems, Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, vol. 135, no. 4, p. 041007, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. W. Neises and C. S. Turchi, A comparison of supercritical carbon dioxide power cycle configurations with an emphasis on CSP applications, Energy Procedia, vol. 49, pp. 1187-1196, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Crespi, G. Gavagnin, D. Sánchez, and G. S. Martínez, Analysis of the thermodynamic potential of supercritical carbon dioxide cycles: a systematic approach, Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, vol. 140, no. 5, p. 051701, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ehsan, S. Duniam, J. Li, Z. Guan, H. Gurgenci, and A. Klimenko, A comprehensive thermal assessment of dry cooled supercritical CO2 power cycles, Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 166, p. 114645, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Du Plessis and M. Owen, Techno-economic analysis of hybrid ACC performance under different meteorological conditions, Energy, vol. 255, p. 124494, 2022.

- R. Laubscher, P. Rousseau, J. van der Spuy, C. Du Sart, and J. P. Pretorius, Development of a 1D network-based momentum equation incorporating pseudo advection terms for real gas sCO2 centrifugal compressors which addresses the influence of the polytropic path shape, Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 55, p. 102921, 2024.

- Flownex, Flownex SE Theory Manual, 2024.

- S. H. Yoon, J. H. Kim, Y. W. Hwang, M. S. Kim, K. Min, and Y. Kim, Heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics during the in-tube cooling process of carbon dioxide in the supercritical region, International journal of refrigeration, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 857-864, 2003.

- F. Menter, R. Sechner, and A. Matyushenko, Best practice: RANS turbulence modeling in Ansys CFD, Ansys Germany GmbH A. Matyushenko, NTS, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2021.

- ANSYS, ANSYS Fluent theory guide, 2024.

- A. Ganguli, S. Tung, and J. Taborek, Parametric Study of Air-Cooled Heat Exchanger Finned Tube Geometry, AIChE Symposium Series, vol. 81, pp. 122-128, 1985.

- V. Gesellschaft, VDI Heat Atlas (Heat Transfer to Finned Tubes). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010.

- K. K. Robinson and D. E. Briggs, Pressure drop of air flowing across triangular pitch banks of finned tubes, in Chem. Eng. Prog. Symp. Ser, 1966, vol. 62, no. 64, pp. 177-184.

- R. Laubscher and P. Rousseau, Coupled simulation and validation of a utility-scale pulverized coal-fired boiler radiant final-stage superheater, Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 18, p. 100512, 2020.

- R. Engelbrecht, R. Laubscher, and J. van der Spuy, A Co-Simulation Approach to Modeling Air-Cooled Condensers in Windy Conditions, in Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, 2020, vol. 84058: American Society of Mechanical Engineers, p. V001T10A013.

- H. K. Versteeg and W. Malalasekera, An introduction to computational fluid dynamics: the finite volume method. Pearson education, 2007.

- B. Celik, U. Ghia, P. J. Roache, C. J. Freitas, H. Coleman, and P. E. Raad, Procedure for Estimation and Reporting of Uncertainty Due to Discretization in CFD Applications, Journal of Fluids Engineering, vol. 130, no. 7, 2008. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Tower height | 55.79 | |

| Heat exchanger inlet height | 11.14 | |

| Inlet diameter | 55.79 | |

| Outlet diameter | 27.89 | |

| Throat height | 50.81 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| PC element passes | - | 8 |

| No. of PC tube banks | - | 35 |

| IC element passes | - | 24 |

| No. of IC tube banks | - | 41 |

| Tube material | - | Mild steel |

| Fin material | - | Aluminium |

| Tube thermal conductivity | 50 W/m∙K | |

| Fin thermal conductivity | 204 W/m∙K | |

| Transverse pitch | 58 mm | |

| Longitudinal pitch | 50.22 mm | |

| Inner tube diameter | 21.6 mm | |

| Outer tube diameter | 25.4 mm | |

| Fin outer diameter | 57.2 mm | |

| Fin root diameter | 27.6 mm | |

| Mean fin thickness | 0.5 mm | |

| Fin pitch | 2.8 mm | |

| Air flow depth | 207.86 mm |

| Parameter | PC | IC | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet stagnation temperature | 95.35 | 72.75 | °C |

| Inlet stagnation pressure | 7.35 | 10.34 | MPa |

| Total design point mass flow rate | 275.5 | 179.1 | kg/s |

| Parameter | Mass flow rate (%) | Heat transfer rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse to medium mesh (21) | ||

| 0.548 | 0.426 | |

| 0.682 | 0.53 | |

| Medium to fine mesh (32) | ||

| 0.264 | 0.181 | |

| 0.33 | 0.226 |

| Parameter | Discretised 1-D model | Co-simulation model | % Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Heat rejection rate (MW) | 81.24 | 71.35 | 13.85 |

| Air mass flow rate (kg/s) | 3671 | 3455 | 6.25 |

| Driving potential (Pa) | 36.42 | 35.75 | 1.87 |

| Precooler | |||

| Heat rejection rate (MW) | 43.72 | 40.12 | 8.97 |

| Air mass flow rate (kg/s) | 1684 | 1583 | 6.35 |

| sCO2 pressure drop (kPa) | 13.53 | 14.59 | -7.25 |

| sCO2 outlet temperature (°C) | 45.89 | 48.88 | -6.12 |

| Intercooler | |||

| Heat rejection rate (MW) | 37.52 | 31.23 | 20.13 |

| Air mass flow rate (kg/s) | 1987 | 1871 | 6.17 |

| sCO2 pressure drop (kPa) | 50.09 | 54.54 | -8.16 |

| sCO2 outlet temperature (°C) | 46.09 | 48.5 | -4.97 |

| Parameter | Lumped geometry | Alternating geometry | % Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat rejection rate (MW) | 71.35 | 72.08 | 1.02 |

| Air mass flow rate (kg/s) | 3455 | 3520 | 1.88 |

| Driving potential (Pa) | 35.75 | 36.52 | 1.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).