1. Introduction

Given the widespread international consensus on the impact of humanity on global warming [

1], it is clear that a comprehensive overhaul of the power generation sector is imperative. The repercussions of global warming require a strategic pivot towards conserving vital resources such as water, which is expected to face severe scarcity with the projected increase in global mean temperature [

2]. Moreover, with the per capita energy demand expected to double by 2050 [

3], the power generation industry faces technical challenges ahead.

Dry cooling technologies offer inherent resource efficiency by minimising water wastage compared to wet cooling technologies [

4]. Widely embraced in arid and semi-arid regions, these systems typically fall into two categories: direct and indirect dry cooling systems.

Among direct dry cooling systems, the most commonly adopted technology is air-cooled condensers (ACCs). In this system, the expanded steam from the low-pressure turbine is directed into finned tube bundles. These bundles, arranged in A-frames, are subjected to airflow that is mechanically driven by large-diameter fans. This airflow facilitates the condensation of steam, which is reused within the power cycle.

Indirect natural draft dry cooling systems, in turn, are often preferred in various applications [

5]. These systems typically consist of two primary components: the cooling tower and the shell-and-tube condenser. In this configuration, the condenser receives expanded steam, facilitating condensation on the outer surface of the condenser tubes by transferring thermal energy to the water circulating within the tubes. The heated water is then pumped to the cooling tower, where it undergoes air cooling via finned tube bundles. As a result, the heated air rises, inducing an updraft that drives airflow through the cooling tower.

Much like ACCs [

6], indirect natural draft dry cooling towers suffer from decreased performance in the presence of crosswinds. The sensitivity of the tower to these winds is influenced by several factors, including its scale, finned tube attributes, geometric ratios, and heat exchanger arrangement [

7]. An extensively researched mitigation solution involves installing windbreaker walls [

8], which can be either internal or external. Internal windbreaker walls prove advantageous in high wind conditions [

9] and have demonstrated benefits for small-scale cooling towers as well [

10]. Additionally, swirl induction platforms have shown promise in reducing cold inflow effects and crosswind sensitivity in small-scale systems [

11]. On the other hand, external windbreaker walls perform well under lower crosswind speeds and are available in solid or radiator-type constructions [

12]. Furthermore, windbreaker walls enhance system performance in multi-tower arrangements [

13]. Lastly, contemporary wedged heat exchanger arrangements offer notable performance benefits [

14].

When comparing ACCs and indirect natural draft dry cooling systems, distinct features emerge. ACCs boast high thermal efficiencies and compactness, yet they require fans and fan drives for airflow, leading to elevated operational costs and frequent maintenance. Conversely, indirect natural draft dry cooling systems are sizable and include expensive shell-and-tube condensers, demanding substantial capital investment [

15]. However, they do not require fan drives, offering passive cooling with associated maintenance cost savings.

While both ACCs and indirect natural draft dry cooling systems are utilised worldwide, there’s a growing interest in developing a cooling system that combines the beneficial aspects of both mentioned technologies. This system would boast high thermal efficiency, eliminate the need for fan drives, forego separate components like shell-and-tube condensers, and significantly reduce operational costs. The natural draft direct dry cooling system (NDDDCS) has been proposed as a system that meets these objectives.

Foundational studies on the NDDDCS have explored various aspects, including heat exchanger arrangement [

16,

17,

18], tower shape [

19], the effectiveness of windbreaker walls [

20], and the scalability and relative performance of the system [

21], employing 3-D CFD simulations under steady-state conditions. Additionally, sensitivity studies on tower geometry have been conducted using 1-D models, building upon the groundwork laid by Kr

ger [

22,

23]. While these investigations offer insights into the steady-state performance of NDDDCSs under both calm and windy conditions, there is still considerable research to be done in this field.

In all the aforementioned 3-D CFD studies, a constant saturated steam temperature boundary condition was utilised to approximate the behaviour of the heat exchangers which are subjected to internal steam flow. While this approach is suitable for assessing relative NDDDCS performance, it diverges from actual operational conditions because the system would receive a variable steam supply rate from the associated power cycle.

Having investigated some of the major aspects of steady-state NDDDCS performance, the study of the transient performance of such systems follow logically. Additionally, the current work is motivated by a long-standing concern among power plant operators and cooling system contractors about the ability of NDDDCSs to support cold plant start-up. These concerns originate from the following argument: unlike indirect natural draft dry cooling systems, which can circulate water through their finned tubes, the NDDDCS relies on steam for this purpose, necessitating the creation of vacuum conditions within the finned tube bundles. ACCs typically utilise fans to generate airflow over the vacuum-induced finned tube bundles, facilitating start-up [

7]. However, the NDDDCS faces a unique challenge: it requires airflow across its heat exchangers to condense the steam, yet internal steam flow is needed to induce the natural draft-driven airflow. Insufficient heat rejection capability during cold-start conditions may result in an excessive build-up of steam back pressure due to inadequate condensation, potentially preventing the plant from starting up.

CFD studies focusing on small-scale indirect natural draft dry cooling towers, by Dong et al. [

24,

25,

26], provide insights that parallel the aforementioned research. These studies delineate four stages in the start-up process: stagnation, plume dominant, draft dominant, and overshoot. Furthermore, researchers utilise the Richardson number to discern between natural, mixed, and forced convection flow regimes. Results for their 1-D model [

25] indicate reduced start-up times with higher heat exchanger temperatures, albeit at the expense of increased transition (mixed convection) phases. Subsequently, a 2-D CFD model indicated reduced start-up times relative to those predicted by the 1-D model [

26], highlighting start-up enhancing 2-D airflow effects. Lastly, a 3-D CFD investigation [

24] showed that start-up performance is improved when either the natural draft or the crosswind dominates the draft driving potential of the system. Moreover, start-up time did not increase with crosswinds exceeding 9 m/s. In the investigated small-scale indirect natural draft dry cooling tower, horizontally arranged heat exchanger bundles were employed, aligning the direction of natural convection plumes parallel to the steady-state flow direction. However, the NDDDCS under scrutiny here utilises vertically arranged heat exchanger bundles. This configuration causes the direction of airflow to vary depending on the dominant convective flow regime.

This study aims to address the gap in the literature concerning the transient start-up characteristics of NDDDCSs. It does so by developing a transient co-simulation model, which integrates adapted versions of previously validated 1-D [

27] and 3-D CFD models [

21], to characterise the start-up performance of the NDDDCS under windless and windy conditions. The analysis considers a large-scale system (900 MWt) intended for a coal-fired power plant. Simulation results from the adapted transient 1-D model are compared with those from the transient co-simulation model, emphasizing their differences and revealing the limitations of the 1-D model. Both the transient 1-D and co-simulation models offer original contributions to the literature by simulating the transient start-up behaviour of the system in an operationally realistic manner, incorporating a variable steam supply rate as an independent boundary condition. The transient 3-D CFD model (forming part of the co-simulation model), adapted from a previous steady-state model [

21], incorporates its same features such as an atmospheric pressure gradient, a porous zone heat exchanger formulation, adaptive source terms triggered by reverse flow, and a user-defined scalar used as a transport equation for the upstream air temperature.

The manuscript is organized as follows:

Section 2 begins by defining the reference tower geometry for each system scale and the finned tube dimensions (

Section 2.1). It then details the equations used in the transient 1-D numerical model (

Section 2.2) and the setup of the transient 3-D CFD model (

Section 2.3), including boundary conditions (

Section 2.3.1), and the heat exchanger modelling approach (

Section 2.3.2). Following this, subsequent sections outline the co-simulation calculation procedure and program logic (

Section 2.4), discuss the convective flow regime monitoring approach (

Section 2.5), and covers the convergence criteria and solution initialization (

Section 2.6), respectively. Thereafter, the mesh independence and uncertainty analyses (

Section 2.7), as well as the time step independence analysis (

Section 2.8) and the validation of both the 1-D and co-simulation models (

Section 2.9), are respectively addressed.

Section 3 describes the simulation protocols and specifications, while

Section 4 presents and discusses the simulation results.

Section 5 draws conclusions from the work, and

Section 6 discusses the study’s implications and limitations, while suggesting potential avenues and improvements for future research.

4. Results and Discussion

For the transient co-simulations performed in this section, a constant ambient temperature of 293.15 K (20°C) is prescribed. The atmospheric pressure gradient follows the definition given in Equation (

29), with the pressure at ground level set to 101.325 kPa. The design point (maximum) steam admission rates for the large-scale NDDDCS is 385.87 kg/s, calculated from steady-state simulations [

21] which utilised a constant saturated steam temperature of 323.15 K (50°C). The reference system dimensions are listed in

Table 1. Initial conditions for all transient no-wind and crosswind cold-start simulations are respectively obtained from an equivalent steady-state 3-D CFD simulation, where the saturated steam temperature is matched to the ambient temperature, eliminating heat transfer. For the sake of the discussion,

, will be noted as the steam-to-tube heat transfer rate,

, as the tube-to-air heat transfer rate and

as the air-side heat transfer rate.

Note that for all subsequent trends, the same inlet steam mass flow rate is specified between to co-simulation and 1-D models. This effectively equates the imposed heat load between the two simulation models, which provides a more sensible comparison.

4.1. No-Wind Results: Cold Start-Up Steam Admission Step Input

Results for the large-scale NDDDCS are presented in this section for a maximum permissible step input of steam admission under no-wind conditions. The maximum permissible condenser tube pressure is limited to 40 kPa(g) (141.325 kPa(a)), thus the step inputs are iteratively varied until a corresponding steam flow step input is found which makes the steam back pressure approach this limit.

The initial conditions for both scales are obtained from windless steady-state CFD simulations, where the saturated steam temperature is equated to the ambient temperature. The resulting initial air mass flow rate calculated for the large-scale NDDDCS is 33.41 kg/s. It is important to note that atmospheric air, under windless conditions, will commonly lack the required momentum to overcome the inertial resistance of a heat exchanger, thus this initial air mass flow rate is potentially non-physical. However, due to the adopted atmospheric pressure gradient, a static pressure differential (≈ 2 kPa for the large-scale NDDDCS) exists between the tower outlet and inlet, which possibly provides a minor driving force. This air mass flow rate accounts for only 0.08% of the steady-state operational air mass flow rate computed for the large-scale (44079.51 kg/s) system [

21], and is thus accepted as representing a no-flow condition.

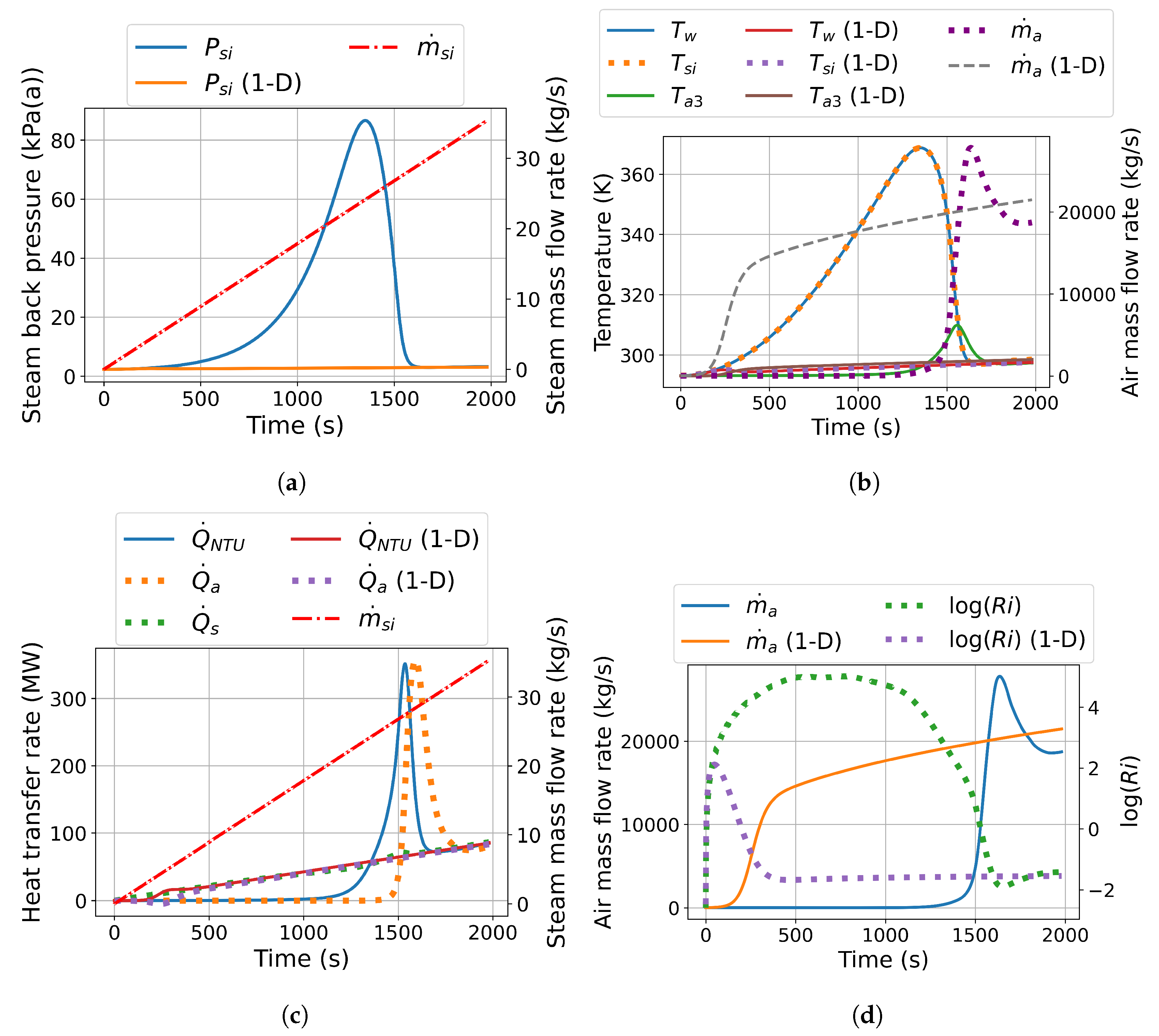

The overall transient responses predicted by the co-simulation and the 1-D models are shown in

Figure 5. Major differences are evident between the 1-D and co-simulation results at both scales, due to the 1-D model having a rapid air-side responsivity. Due to the adopted derivation approach, outlined in

Section 2.2, the 1-D model assumes the entire NDDDCS flow volume as a singular control volume. Naturally, this approximation negates any of the complex 3-D airflow effects which the co-simulation accounts for. Furthermore, the transportation of heated airflow throughout the NDDDCS flow volume is negated by this 1-D approach, and intricate flow field development effects are omitted.

The large-scale system exhibits a limited tolerance to a steam admission step input under these windless conditions. A minor steam admission step input of 5.8% of its maximum steam admission rate results in a pronounced rise in steam back pressure (

Figure 5 (a)), which narrowly avoids the condenser tube pressure limit. In stark contrast, for the same steam admission step input, the 1-D model computes a peak steam back pressure of 16 kPa(a).

As indicated in

Figure 5 (b), the stagnation in air mass flow rate computed by the co-simulation strongly coincides with the large peak in steam back pressure. Due to the lack of airflow in the initial 750 s predicted by the co-simulation, the system must raise the steam saturation temperature (and associated steam back pressure), in order to match the imposed steam flow step input. The 1-D simulation predicts a rapid rise in the air mass flow rate, which already settles within the first 500 s, thus explaining the dramatic differences observed for the steam-side responses in

Figure 5 (a).

Furthermore, the tube-to-air heat transfer rate (

) of the 1-D model peaks at 50 s, whereas the corresponding peak for the co-simulation model only occurs at 1100 s (

Figure 5 (c)). The air-side heat transfer rate (

) strongly trends with the air mass flow rate, which along with the minor air temperature difference (

Figure 5 (b)) explains the delay in peak air-side heat rejection (1200 s).

The large-scale co-simulation Richardson number response highlights the overt reliance the system has on natural convection, especially in the first 750 s. Moreover,

upon cold start-up, which is several orders of magnitude away from the mixed and forced convection flow regimes. The natural convective currents, which flow in the vertical direction, cause a blocking effect at the outlet of the heat exchangers, illustrated in

Figure 6 (a) and (b). Downstream of the heat exchangers, the unheated internal airflow recirculates, as a small amount of heated air flows along the internal tower shell wall surfaces. Furthermore, these buoyant plumes collide with the inner face of the clapboard, causing a localised stagnation of air as depicted in

Figure 6 (a). Some heated air flows around the outer edge of the clapboard, exiting the NDDDCS flow volume. This thermal energy is effectively wasted in the cold start-up process, as it does not contribute to the system’s draft driving potential. Adjustment of the tower-to-heat exchanger arrangement is recommended to mitigate these effects.

At 960 s, bulk flow initiates through the heat exchangers of the large-scale NDDDCS, coinciding with mixed convection effects becoming significant, illustrated in

Figure 6 (c). In contrast, the 1-D model is already within the forced convection stage at 960 s (

Figure 5 (d)). As predicted by the co-simulation model, the lower regions of the NDDDCS flow volume remain unheated at this stage. The colder, denser air in these regions effectively impose a flow resistance on the incoming air, which is accelerated along the inner surfaces of the tower shell wall, shown in

Figure 7 (a). The leading edges of these high-velocity air streams mix and collide with the colder regions of air above it, and more toward the tower centre, leading to flow separation and the formation of recirculation zones.

Pronounced overshoots in the air mass flow rate and outlet air temperature are predicted by the large-scale co-simulation as seen in

Figure 5 (b). These overshoots are significantly larger than those predicted by the 1-D model. As the steam-to-tube heat transfer rate rises almost instantly along with the imposed heat load, it remains unmatched by the tube-to-air heat transfer rate (

). This rise in steam saturation temperature elevates the condenser tube wall temperature, leading to a peak in outlet air temperature. The overshoot in outlet air temperature temporary boosts the system draft driving potential, culminating in an inertia-driven overshoot for the air mass flow rate. This effect has also been observed for a small-scale indirect system in another study [

26].

Figure 5 (d) reveals significant differences in the transition times between the convective flow regimes as predicted by the co-simulation versus the 1-D model. By 100 s, both systems remain in the natural convection regime, but the Richardson number differs by more than three orders of magnitude between the two models. Notably, the co-simulation predicts a sharp rise and subsequent plateau in the Richardson number for the first 400 s, a feature much less evident in the 1-D model. The 1-D model shows a transition to forced convection around 250 s, whereas the co-simulation reaches this stage only after approximately 1100 s.

Despite forced convection dominating for the co-simulation beyond 1100 s, the flow field remains underdeveloped even at 1140 s, as shown in

Figure 7 (b). It is evident that the majority of the NDDDCS thermal flow field development occurs once the forced convection regime begins (

).

Figure 7 (b) illustrates how airflow becomes more organized near the inner tower walls, contrasting with the chaotic downward flow in the core, which converges toward the heat exchangers and interacts with the incoming forced airflow, creating recirculation zones.

Figure 8 illustrates the start up process and the NDDDCS transitions through the various convective flow regimes. At 1050 s (

Figure 8 (c)), the outlet air temperature from the heat exchangers is relatively high due to low air velocities, resulting in higher heat exchanger effectivenesses. As plume formation initiates around 1080 s (

Figure 8 (d)), a choking effect occurs at the NDDDCS outlet which forces heated air downward, subsequently mixing with the cooler air in the middle region of the NDDDCS flow volume. This mixing suddenly decreases the air density throughout much of the tower flow volume, which rapidly augments the system’s draft driving potential. Resultantly, a sharp rise in air mass flow rate from 1500 kg/s at 1050 s (

Figure 8 (c)) to 28600 kg/s at 1140 s (

Figure 8 (f)), is observed. This sudden surge causes an inertia-driven overshoot in air mass flow rate, consistent with observations by others [

26].

The subsequent increase in air velocity leads to a sharp drop in the heat exchanger outlet air temperature. Between 1050 s and 1200 s (

Figure 8 (c) to (h)), the last remnants of cold air become trapped between the incoming airflow from the heat exchangers and the merging flow from the upper regions of the tower, resulting in thorough mixing. Consequently, the air temperature at the centre of the tower is slightly lower than near the inner tower wall surfaces. Plume stabilization occurs between 1080 s and 1170 s, after which the thermal flow field is fully developed.

4.2. No-Wind Results: Cold Start-Up Steam Admission Load Ramp

This section presents the simulation results for the large-scale NDDDCS subjected to windless conditions and a load ramp. The initial windless condition is identical to that used in the previous section, utilising a no-wind CFD simulation where the saturated steam temperature is equated to the ambient temperature.

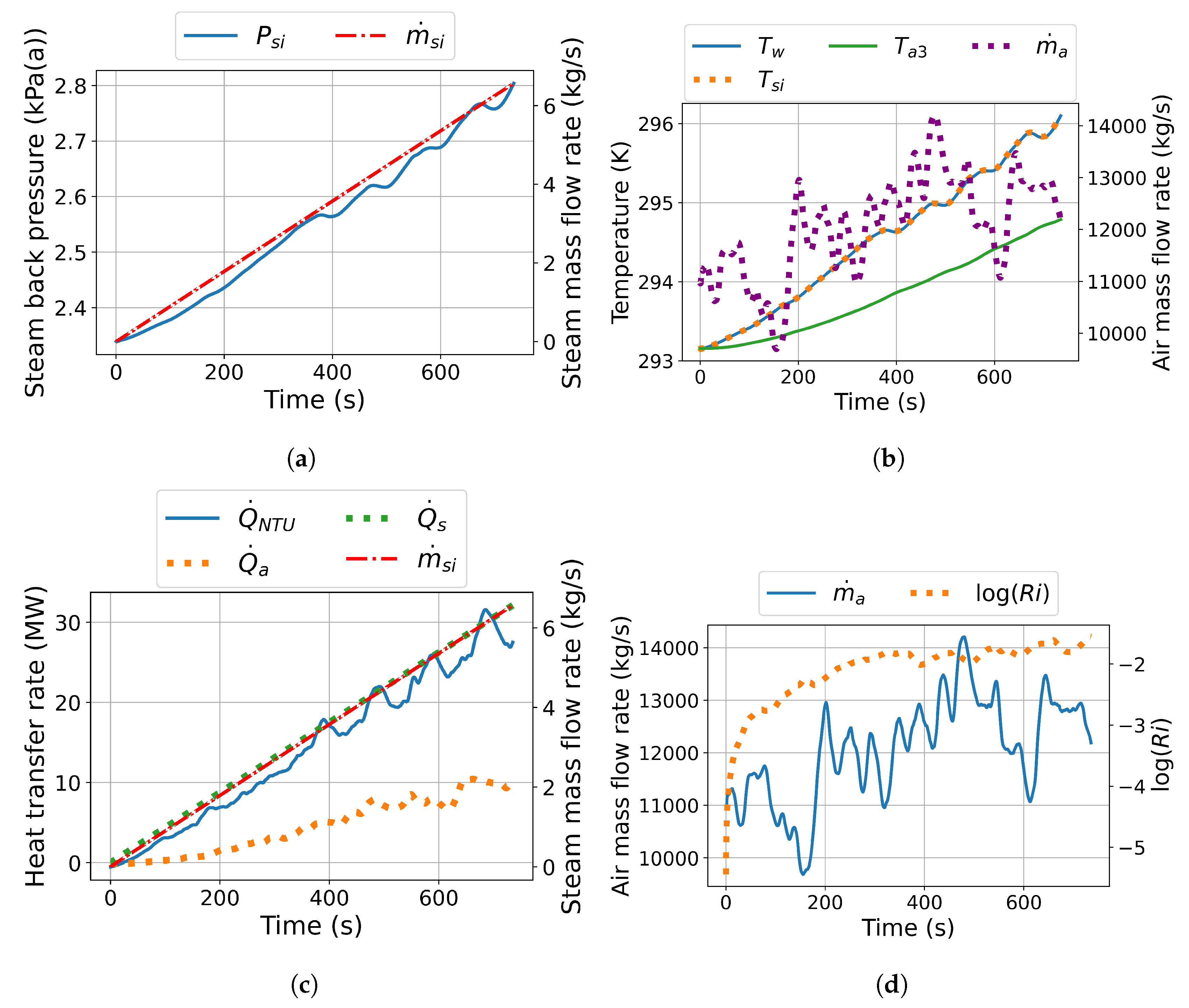

Figure 9 shows the transient co-simulation response of the large-scale system. The co-simulation predicts a surge in steam back pressure to a maximum of 87 kPa(a), about 1350 s after initial steam admission, as illustrated in

Figure 9 (a). In contrast, the 1-D simulation computes only a slight increase in steam back pressure which promptly subsides as the air mass flow rate quickly rises, as shown in

Figure 9 (a) and (b). Similar to the steam admission step input results, the 1-D simulation responds significantly faster than the co-simulation. This difference in response time is due to the 1-D model’s inability to capture complex air-side phenomena, such as plume blocking, flow field development, and air mixing, which play a pivotal role during the cold start-up process.

The tube-to-air (

) heat transfer rate predicted by the co-simulation model significantly trails behind that of the 1-D simulation, as shown in

Figure 9 (c). The co-simulation also indicates that the air-side (

) heat transfer rate is nearly negligible, primarily due to the minimal air mass flow through the heat exchanger and the small air temperature difference. The large discrepancy between the steam-to-tube and tube-to-air heat transfer rate results in an overt reliance on the thermal storage capacity of the condenser tube walls, leading to an excessive increase in tube wall temperature. This restricts the steam-to-tube heat transfer rate, which in turn limits the steam condensation rate, thus increasing the steam back pressure, and associated steam saturation temperature. As a result, a substantial mass imbalance arises between the steam entering and the condensate leaving the condenser tubes, causing the steam back pressure to surge. The exceedance of the steam back pressure limit of 40 kPa(g) is avoided by the large thermal energy sink provided by the condenser tube wall, thus avoiding further rises in steam back pressure. However, as the results indicate, improper selection of the condenser tubes - and subsequent thermal storage sink provided by them - could lead to system overpressure.

During the initial cold start-up phase, the predicted Richardson number of the large-scale co-simulation remains stagnant for the entire period up to 1200 s, as depicted in

Figure 9 (d). At this same time instance, the Richardson number for the step input, shown in

Figure 5 (d), is lower (

) = -1.5) than for the load ramp (

) = 3.8), indicating that airflow in the large-scale NDDDCS relies less on natural convection during the steam admission step input scenario. As the steam supply rate in the steam admission load ramp eventually surpasses that of the step input, the NDDDCS encounters a higher heat load. However, the system is less equipped to reject this heat to the ambient air due to its reliance on natural convection. Beyond 1200 s, the escalating heat load in the load ramp scenario exacerbates the system’s dependence on natural convection, the only available convective heat transfer mechanism at this stage. This reliance intensifies plume blocking effects and continues to stall the Richardson number, due to the low air velocities and elevated condenser tube wall temperatures. These observations highlight the intricate relationship between NDDDCS start-up performance, flow field development and the steam admission rate.

These findings underscore the critical role of air-side flow field development in the NDDDCS for effective heat rejection and steam condensation, which are essential for preventing system overpressure during cold start-up. The load ramp profile employed here results in lower thermal heat transfer to the air-side compared to the more abrupt heat load imposed by steam flow step inputs. While step inputs immediately introduce a substantial heat load to the NDDDCS, load ramps gradually increase the heat load. This gradual increase delays the development of the flow field, causing the steam back pressure to spike to 87 kPa(a) before the system can achieve start-up. Although the large-scale NDDDCS does not pose any limitation on power plant start-up under these conditions, the corresponding thermal sink provided by the condenser tubes should be seen as an important design parameter for avoiding system overpressure under no-wind conditions.

4.3. 9 m/s Crosswind Results: Cold Start-Up Steam Admission Load Ramp

This section presents the co-simulation results for a cold start-up scenario under a 9 m/s crosswind and a load ramp steam admission rate. The initial condition is established by calculating the steady-state flow field for the NDDDCS with a 9 m/s crosswind, where the steam temperature matches the ambient temperature, resulting in no initial heat transfer. The transient response of the large-scale NDDDCS under these conditions is illustrated in

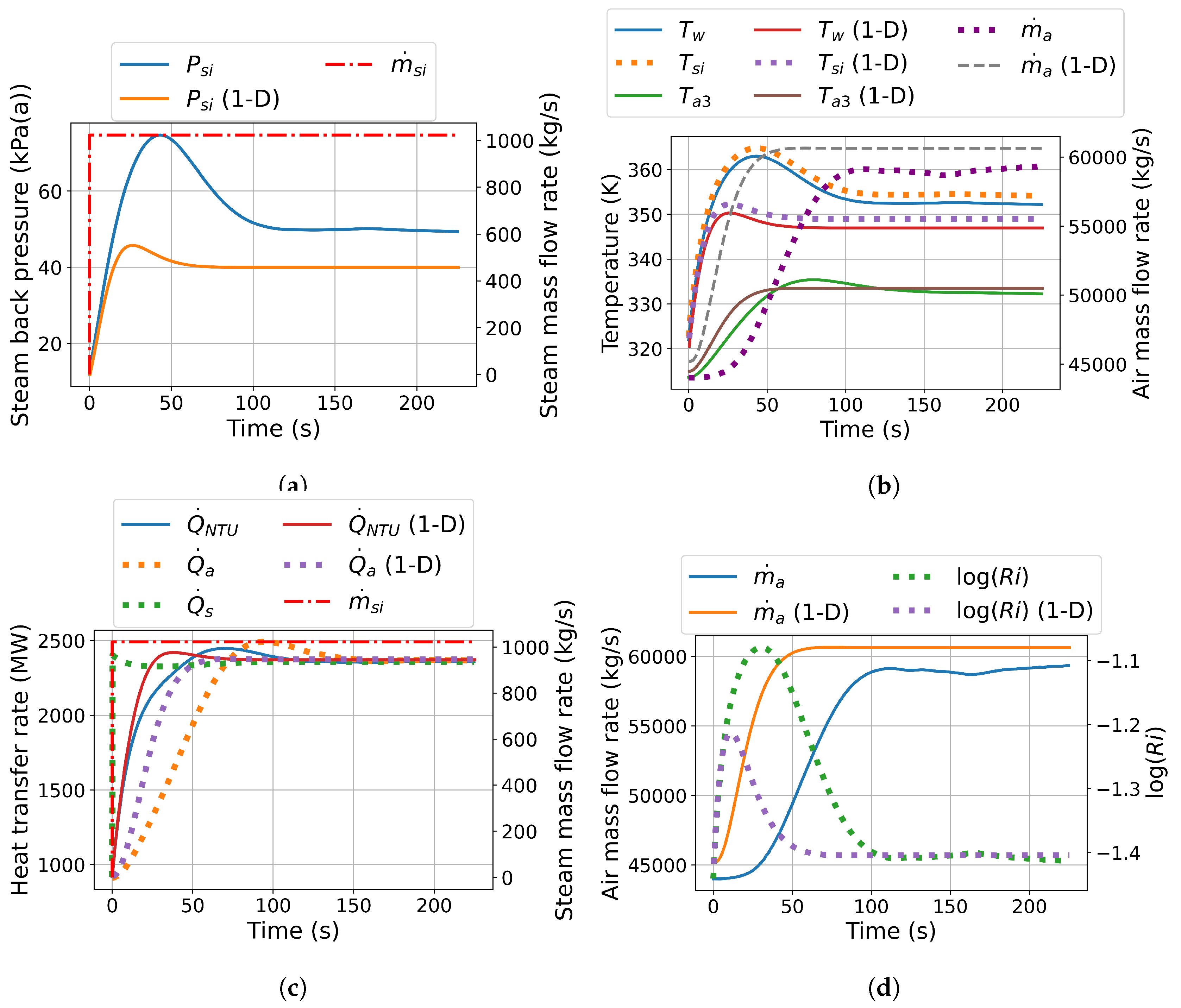

Figure 10.

The 9 m/s crosswind proves beneficial for the large-scale NDDDCSs, facilitating successful cold start-up. Despite the initial chaotic fluctuations in air mass flow rate following steam admission, as seen in

Figure 10 (b), the increased airflow from the crosswind allows the systems to effectively manage the imposed heat load dictated by the ramp profile.

The steam back pressure of the large-scale NDDDCS closely tracks the imposed steam admission load ramp profile, as shown in

Figure 10 (a), indicating that the system can effectively reject the required heat load under 9 m/s crosswind conditions. The observed oscillations in steam back pressure, following the load ramp curve, are attributed to constant flow separation and recirculation around the heat exchanger deltas, consistent with steady-state crosswind CFD results presented in previous work [

16,

17,

21].

The large-scale system reaches a pseudo steady-state, as evidenced by the alignment of the steam-to-tube (

) and tube-to-air (

) heat transfer rates with the load ramp profile in

Figure 10 (c). The air-side heat transfer rate (

) also increases in response to the steam admission load ramp curves, but trails behind. This indicates that at this stage in the NDDDCS start-up a notable amount of thermal energy is carried away by the crosswind, and thus does not contribute to the NDDDCS draft driving potential. Although the crosswind proves detrimental from the perspective of increasing the draft driving potential of the system, it nonetheless aids in providing adequate air-side heat rejection capacity to facilitate cold start-up.

For the large-scale system, the difference between the imposed steam mass flow rate and the calculated condensation rate is negligible by 400 s. Furthermore, the steam-to-tube and tube-to-air heat transfer rates trend closely, confirming that a pseudo steady-state condition is achieved beyond this point. The trend in the outlet air temperature shown in

Figure 10 (b), correlates with the air-side heat transfer rate. Furthermore, the outlet air temperature rises proportionally along with the tube wall temperature, driven by the increasing steam saturation temperatures. This air temperature rise facilitates a reduction in air density within the NDDDCS flow volume, which enhances the draft driving potential of the large-scale NDDDCS.

Initially, the system operates in the forced convection flow regime, as indicated in

Figure 10 (d), due to the lack of a temperature differential between the condenser tube walls and the ambient air, rendering buoyancy effects negligible compared to the inertial forces originating from the crosswind. As steam is introduced into the condenser tubes, the steam saturation temperature rises. This increase in temperature is reflected in the Richardson number, which drifts towards a maximum value of

in response to the expanding temperature differential. However, the Richardson number remains significantly lower than that computed under no-wind steam admission load ramp conditions, as shown by comparing

Figure 10 (d) with

Figure 9 (d). Moreover, the crosswind effectively mitigates the no-wind flow interference effects caused by rising buoyant plumes. By driving air horizontally through the heat exchangers, particularly on the windward side, the crosswind negates these detrimental effects.

These results demonstrate that under 9 m/s crosswind conditions with a steam admission load ramp, the start-up performance of the NDDDCS is significantly improved compared to equivalent no-wind scenarios. As a result, large-scale NDDDCSs do not pose any limitations on power plant start-up under these conditions, aligning with findings from [

24], which reported enhanced start-up performance when crosswinds dominate the system’s draft driving potential.

4.4. No-Wind Results: Full Load Turbine Islanding Scenario

This section presents the transient response of a large-scale NDDDCS subjected to a full-load islanding event, evaluated using both a 1-D numerical model and a co-simulation. Initially, the NDDDCS operates steadily at 100% of its rated steam admission rate (385.57 kg/s). A step increase in steam admission is then applied, simulating a sudden rise in thermal load. The steam admission rate was incrementally increased until a limiting step input was identified, corresponding to a rise in back pressure approaching the turbine protection threshold of 75 kPa(a).

Figure 11 presents the transient evolution of key system variables. Results indicate that the NDDDCS can accommodate a step change in steam load from 100% (385.57 kg/s) to 265% (1021.76 kg/s) - a 165% relative increase without exceeding the low-pressure turbine back pressure protection limit (

Figure 11 (a)). The 1-D model predicts a peak back pressure of 46 kPa(a). Additionally, the differences in the predicted steady-state steam back pressures between the 1-D and co-simulation models, under identical steam mass flow rate boundary conditions, are consistent with the validation results discussed in

Section 2.9.

Figure 11 (b) illustrates the temperature response. The 1-D model predicts a sharp increase in tube wall temperature from 323 K to 352 K within 20 s. The co-simulation mirrors this trend but with amplified values, reaching 365 K after 45 s. Steady-state conditions are achieved at 75 s and 125 s for the 1-D and co-simulation models, respectively. The discrepancy in final steam saturation temperatures is attributed to the lower air-side flow losses predicted by the 1-D model. This is reflected in a higher steady-state air mass flow rate and thus a reduced steam pack pressure. These dynamics are further evidenced in the outlet air temperature trends, where the 1-D model reaches steady-state after 55 s, compared to 200 s for the co-simulation.

Due to the thermal sink provided by the finned tubes, the steam-side heat transfer rate (

) rapidly equilibrates with the imposed heat load (

Figure 11 (c)). Both models show closely aligned heat transfer rate trends. The 1-D model predicts a faster response in

, with reduced overshoot compared to the co-simulation. A similar trend is observed for

, which rises slightly faster in the 1-D model, though overshoot magnitudes are comparable.

The enhanced responsiveness of the 1-D model is further supported by the predicted evolution of the Richardson number (

Figure 11 (d)). Upon islanding, both models show an increase in the Richardson number, but to different extents. The 1-D model predicts a peak value of -1.2, while the co-simulation reaches -1.08, approaching the transition to mixed convection flow.

Overall, these full-load islanding results demonstrate that once the NDDDCS flow field is fully developed - as it typically is under steady, windless operational conditions - the system can reliably accommodate significant and instantaneous load increases. The close agreement between the 1-D and co-simulation model transient predictions underscores the robustness and practical utility of the 1-D model for dynamic analysis of large-scale NDDDCS systems under critical operational scenarios.

6. Implications and Future Work

This study highlights the intricate cold start-up and operational performance characteristics of NDDDCSs utilising two different models, under both windless and windy conditions. A key finding is that the tower-to-heat exchanger arrangement should be adjusted to enhance NDDDCS start-up performance, ensuring that the rising natural convective currents flow directly into the NDDDCS flow volume under initial heat transfer from the heat exchangers. To achieve this, the heat exchanger bundles could potentially be vertically arranged within the perimeter of the NDDDCS tower shell wall (inlet diameter) or the clapboard could be extended.

The transient 1-D NDDDCS model employed in this study assumes a uniform air-side flow volume, encompassing the entire air-side control volume. This assumption overlooks the complex airflow effects predicted by the co-simulation. However, by discretising the air-side of the 1-D model, some of these effects could be captured, thereby enhancing the model’s predictive accuracy.

The co-simulation model combines the total condenser tube steam-side volume into a singular control volume. Future studies could divide the condenser tubes into distinct sectors, allowing for spatial variability in the steam back pressure, the corresponding steam saturation temperature and condenser tube wall temperature for every time step. Moreover, the 1-D steam-side of the co-simulation model can be extended to include momentum losses, which would result in a reduction in steam saturation pressure as the steam flows through the condenser tubes.

Finally, future work should explore integrating the co-simulation model approach into steady-state 3-D CFD models, allowing for coupled interaction between the steam- and air-sides, thereby providing a more accurate representation of NDDDCS operation.

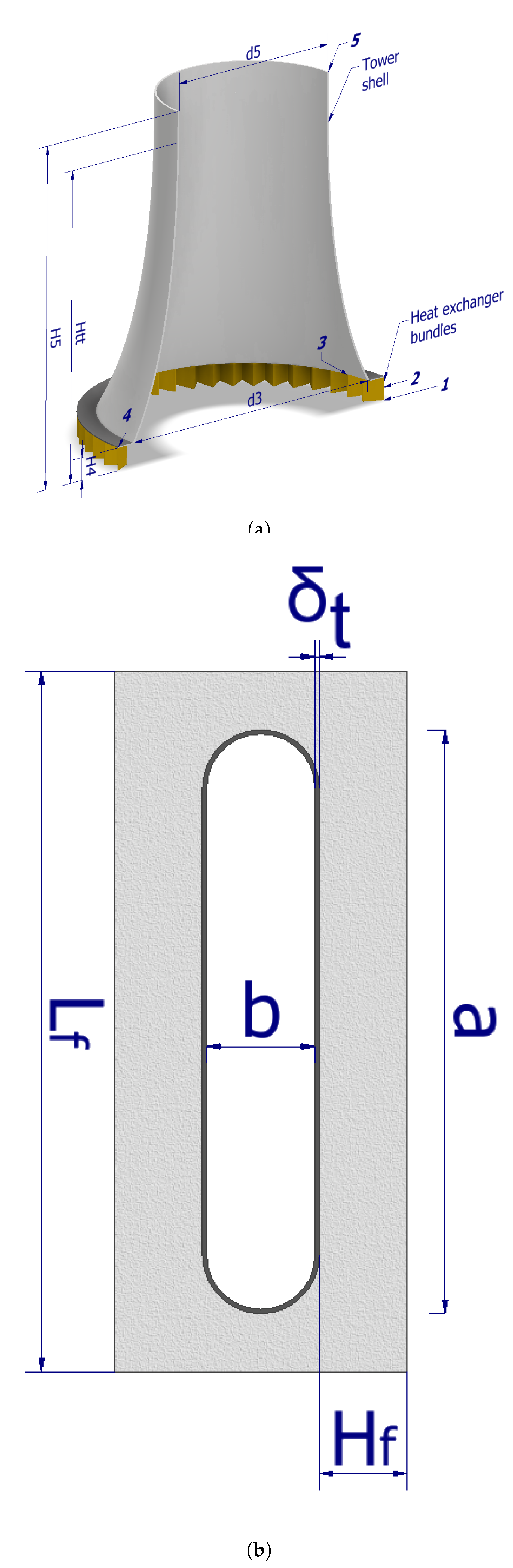

Figure 1.

Schematic of NDDDCS (a) and effective single-row finned tube (b).

Figure 1.

Schematic of NDDDCS (a) and effective single-row finned tube (b).

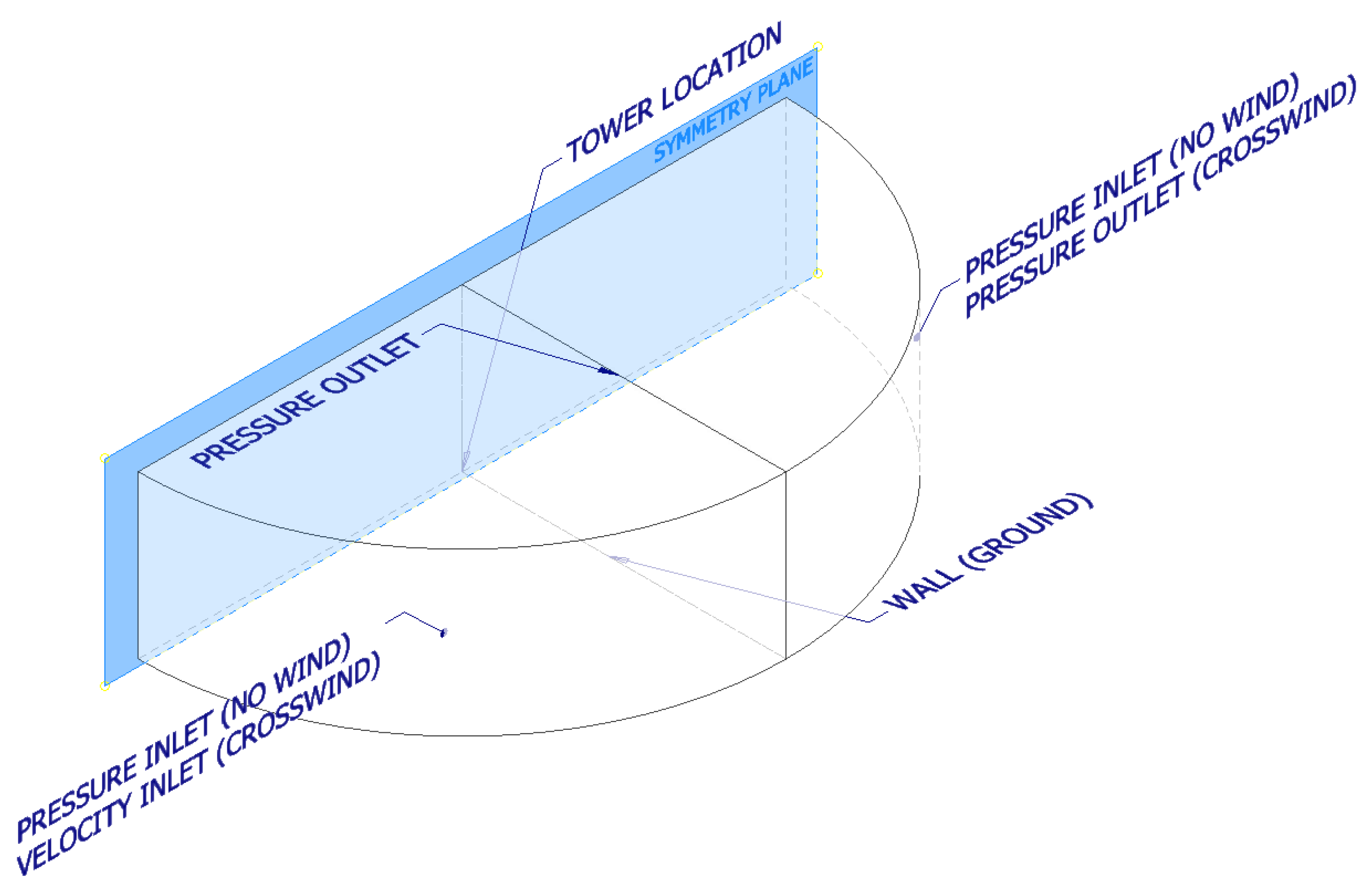

Figure 2.

Schematic of domain and boundary conditions for NDDDCS simulation.

Figure 2.

Schematic of domain and boundary conditions for NDDDCS simulation.

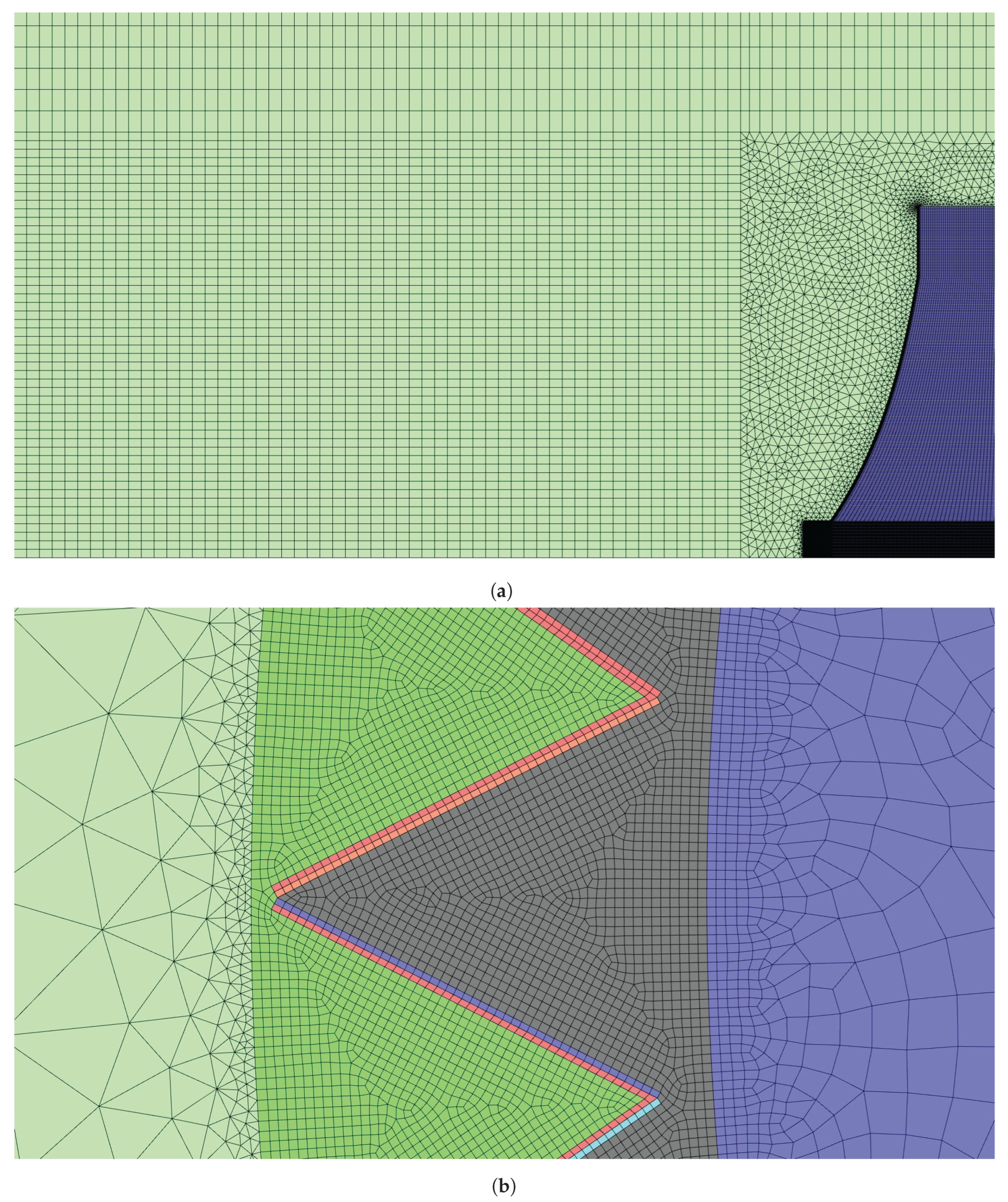

Figure 3.

Structured mesh in extended domain (8 m element size top region, 4 m element size lower region) and unstructured near-field mesh (4 m element size) (a) and local mesh around (0.25 m element size) and within (0.25 m element size) porous zone (b) for large-scale NDDDCS simulation.

Figure 3.

Structured mesh in extended domain (8 m element size top region, 4 m element size lower region) and unstructured near-field mesh (4 m element size) (a) and local mesh around (0.25 m element size) and within (0.25 m element size) porous zone (b) for large-scale NDDDCS simulation.

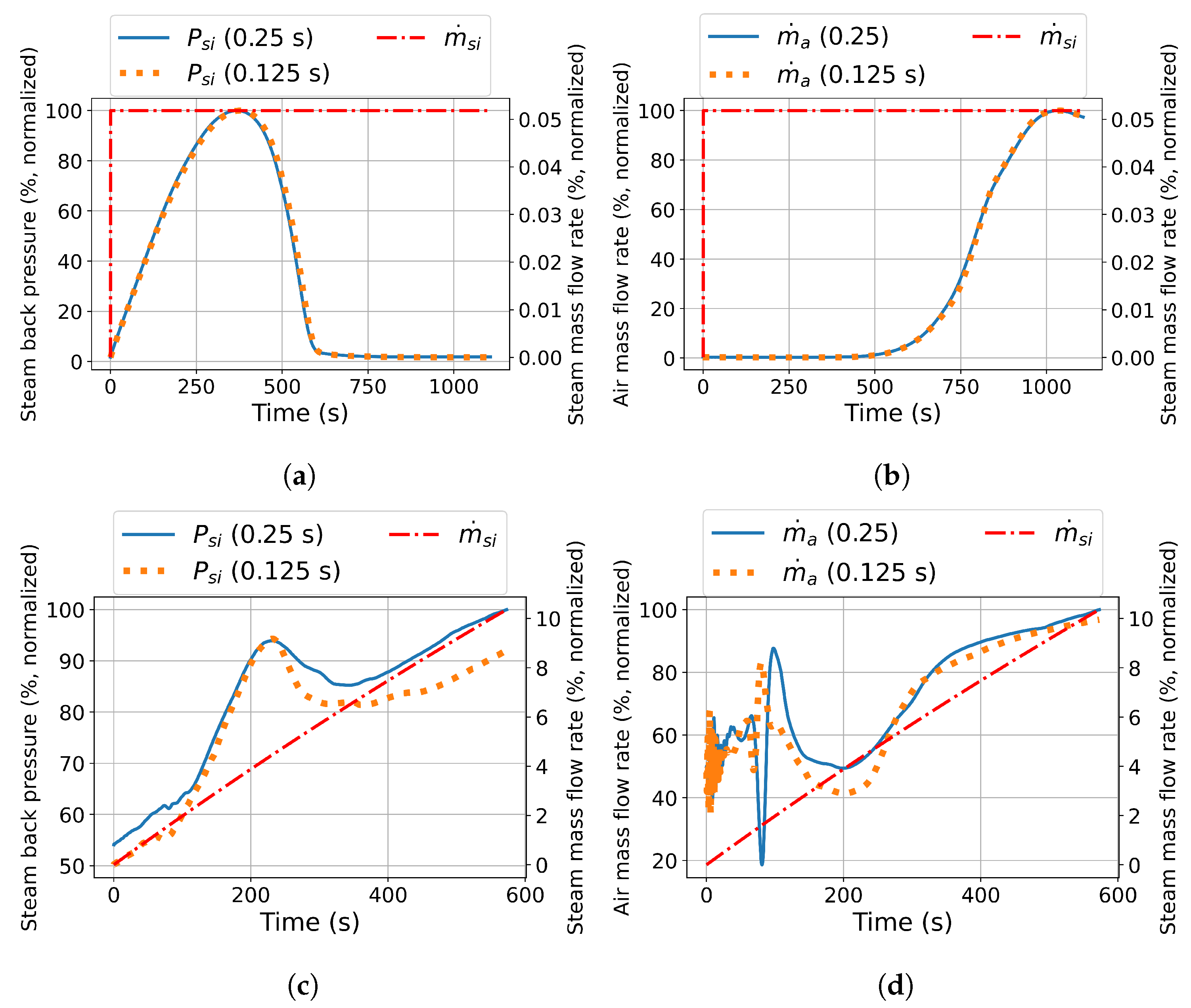

Figure 4.

Co-simulation time step sensitivity study: large-scale system steam back pressure (abs) (a) and air mass flow rate (b); downscaled system steam back pressure (abs) (c) and air mass flow rate (d) transient response (primary y-axis) under step input steam admission (secondary y-axis) and no-wind conditions.

Figure 4.

Co-simulation time step sensitivity study: large-scale system steam back pressure (abs) (a) and air mass flow rate (b); downscaled system steam back pressure (abs) (c) and air mass flow rate (d) transient response (primary y-axis) under step input steam admission (secondary y-axis) and no-wind conditions.

Figure 5.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under step input steam admission (secondary y-axis) and no-wind conditions.

Figure 5.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under step input steam admission (secondary y-axis) and no-wind conditions.

Figure 6.

Vector plot (a) and contour plot (b) coloured by temperature for large-scale NDDDCS inlet at 600 s, showing blocking effect due to rising plumes from natural convection () = 4.5); Vector plot (c) coloured by temperature for large-scale NDDDCS inlet at 960 s showing initiation of bulk flow () = 0.2).

Figure 6.

Vector plot (a) and contour plot (b) coloured by temperature for large-scale NDDDCS inlet at 600 s, showing blocking effect due to rising plumes from natural convection () = 4.5); Vector plot (c) coloured by temperature for large-scale NDDDCS inlet at 960 s showing initiation of bulk flow () = 0.2).

Figure 7.

Contour plot coloured by velocity magnitude for large-scale NDDDCS showing wall-bound flow at 960 s ()) = 0.2); Vector plot coloured by velocity magnitude for large-scale NDDDCS showing partially developed flow at 1140 s () = -1).

Figure 7.

Contour plot coloured by velocity magnitude for large-scale NDDDCS showing wall-bound flow at 960 s ()) = 0.2); Vector plot coloured by velocity magnitude for large-scale NDDDCS showing partially developed flow at 1140 s () = -1).

Figure 8.

Large-scale NDDDCS contour plots coloured by temperature showing development of thermal flow field under step input steam admission and no-wind conditions.

Figure 8.

Large-scale NDDDCS contour plots coloured by temperature showing development of thermal flow field under step input steam admission and no-wind conditions.

Figure 9.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under under no-wind load ramp.

Figure 9.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under under no-wind load ramp.

Figure 10.

Co-simulation: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under load ramp and 9 m/s crosswind conditions.

Figure 10.

Co-simulation: steam back pressure (a) and heat transfer rate (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); temperature (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under load ramp and 9 m/s crosswind conditions.

Figure 11.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and temperature (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); heat transfer rate (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under full load turbine islanding scenario.

Figure 11.

Co-simulation vs 1-D: steam back pressure (a) and temperature (b) (primary y-axis) vs steam mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); heat transfer rate (c) (primary y-axis) vs air mass flow rate (secondary y-axis); air mass flow rate (d) (primary y-axis) vs Richardson number (secondary y-axis) transient response for large-scale NDDDCS under full load turbine islanding scenario.

Table 1.

NDDDCS reference dimensions at the two scales under consideration.

Table 1.

NDDDCS reference dimensions at the two scales under consideration.

| Description |

Symbol |

Value (m) |

| Tower dimensions |

|

|

| Total tower height |

|

165.0 |

| Height of tower throat |

|

150.3 |

| Inlet height |

|

16.5 |

| Inlet diameter |

|

165.0 |

| Outlet/Throat diameter |

|

82.5 |

| Tower shell thickness |

|

1 |

| Finned tube dimensions |

|

|

| Base tube major axis |

a |

0.15 |

| Base tube minor axis |

b |

0.026 |

| Base tube thickness |

|

0.0015 |

| Tube pitch |

|

0.067 |

| Fin length |

|

0.18 |

| Fin height |

|

0.0195 |

| Fin thickness |

|

0.00025 |

| Fin pitch |

|

0.0023 |

Table 2.

Summary of governing equations.

Table 2.

Summary of governing equations.

| Description |

Equation |

| Continuity |

|

| X-momentum |

|

| Y-momentum |

|

| Z-momentum |

|

| Energy |

|

Table 3.

Mesh sensitivity analysis and grid convergence index results.

Table 3.

Mesh sensitivity analysis and grid convergence index results.

| Mesh |

(kg/s) |

(MW) |

| Coarse (7.3 M) |

44126.20 |

924.18 |

| Fine (11.3 M) |

44094.68 |

928.18 |

|

44058.27 |

932.80 |

|

(%) |

0.083 |

0.495 |

|

(%) |

0.248 |

1.493 |

Table 4.

Systematic validation of transient 1-D numerical model to 3-D CFD model by [

17].

Table 4.

Systematic validation of transient 1-D numerical model to 3-D CFD model by [

17].

| Variable |

(kg/s) |

(MW) |

(K) |

(kg/s) |

| 3-D CFD by Kong et al. [17] |

32557.97 |

1136.35 |

360.95 |

496.62 |

| Heat exchanger characteristics from Kong et al. [17] |

|

|

|

|

| 1-D steady-state model [22,23] |

31942.47 |

1130.02 |

360.95 |

493.70 |

| Heat exchanger characteristics from Krger [7] |

|

|

|

|

| 1-D steady-state model [22,23] |

33058.44 |

1305.60 |

360.95 |

570.41 |

| 1-D transient model |

31108.19 |

1142.08 |

356.43 |

496.62 |

Table 5.

Validation of steady-state NDDDCS 3-D CFD model under no-wind and 6 m/s crosswind conditions [

21].

Table 5.

Validation of steady-state NDDDCS 3-D CFD model under no-wind and 6 m/s crosswind conditions [

21].

| Variable |

(kg/s) |

(MW) |

| No-wind |

|

|

| CFD by Kong et al. [17] |

32557.97 |

1136.35 |

| 3-D NDDDCS model [21] |

32926.18 |

1080.42 |

| 6 m/s crosswind |

|

|

| CFD by Kong et al. [17] |

29499.58 |

1055.27 |

| 3-D NDDDCS model [21] |

29439.39 |

971.02 |

| Relative performance deterioration |

|

|

| CFD by Kong et al. [17] |

-9.39% |

-7.14% |

| 3-D NDDDCS model [21] |

-10.59% |

-10.13% |

Table 6.

Validation of transient co-simulation model under no-wind conditions.

Table 6.

Validation of transient co-simulation model under no-wind conditions.

| Model |

(K) |

(MW) |

(kg/s) |

(Pa) |

(kg/s) |

| 3-D NDDDCS model [21] |

323.15 |

927.51 |

44097.51 |

79.95 |

385.87 |

| Co-simulation model |

322.74 |

918.92 |

44015.73 |

78.24 |

385.87 |