1. Introduction

Understanding the kinetics of competitive and incompatible chemical reactions remains one of the central challenges in modern physical chemistry. Classical models, including Langmuir adsorption kinetics, power-law approximations, and rate equations derived from mass-action principles, have provided powerful but limited frameworks [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These approaches often assume isotropy, independence of pathways, and purely Markovian dynamics, which restricts their applicability when anisotropy, memory effects, or strong correlations emerge in complex systems [

5,

6,

7].

Recent advances in nonequilibrium thermodynamics and information theory have emphasized the need for generalized operators that integrate uncertainty, entropic contributions, and non-Markovian dynamics [

8,

9,

10]. In particular, quaternionic algebra provides a natural mathematical structure to represent directional and anisotropic interactions, as its non-commutative nature encodes correlations between pathways beyond scalar kinetics [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Complementarily, fractional calculus has emerged as a robust tool to incorporate memory kernels into thermodynamic and kinetic descriptions, bridging anomalous diffusion and persistence phenomena observed in heterogeneous catalysis and biochemical systems [

15,

16,

17,

18].

In this work, we propose a quaternionic–fractional kinetic operator that unifies three critical dimensions of entropy-based modeling:

- (i)

uncertainty quantification, through an angular error operator capturing deviations between theoretical and experimental orientations;

- (ii)

complexity and correlations, by quaternionic weights and interference terms describing anisotropic couplings between pathways; and

- (iii)

entropic memory, introduced by fractional chemical potentials consistent with non-Markovian persistence.

This unified formalism provides an extended framework that recovers classical kinetics as limiting cases, while systematically incorporating entropy as both a geometric and temporal correction. By embedding anisotropy, correlation, and memory into a single operator, the proposed model addresses the limitations of existing kinetic laws and establishes a general platform for studying competitive and incompatible chemical reactions.

2. Theoretical Framework.

2.1. Quaternionic Representation of Reaction Probabilities

A quaternion (1) can be separated into a scalar part and a vector part (, , ). In the context of reaction kinetics, the scalar term is associated with the overall magnitude of a measurable property (e.g., concentration or probability amplitude), while the vector part encodes directional preferences in a multidimensional property space (e.g., selectivity, affinity, or steric orientation).

This formalism allows each reaction pathway to be represented as a quaternionic weight. Its non-commutative algebra naturally accounts for anisotropic interactions, where the outcome of one pathway may influence another in a directionally dependent manner [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This goes beyond classical models that only consider scalar quantities.

2.2. Entropy and Angular Error as Uncertainty Operator

Entropy provides a natural framework for quantifying uncertainty. Following Shannon, entropy is defined as:

where

probabilities of microscopic outcomes. In reaction kinetics, entropy thus measures the uncertainty associated with the distribution of pathways.

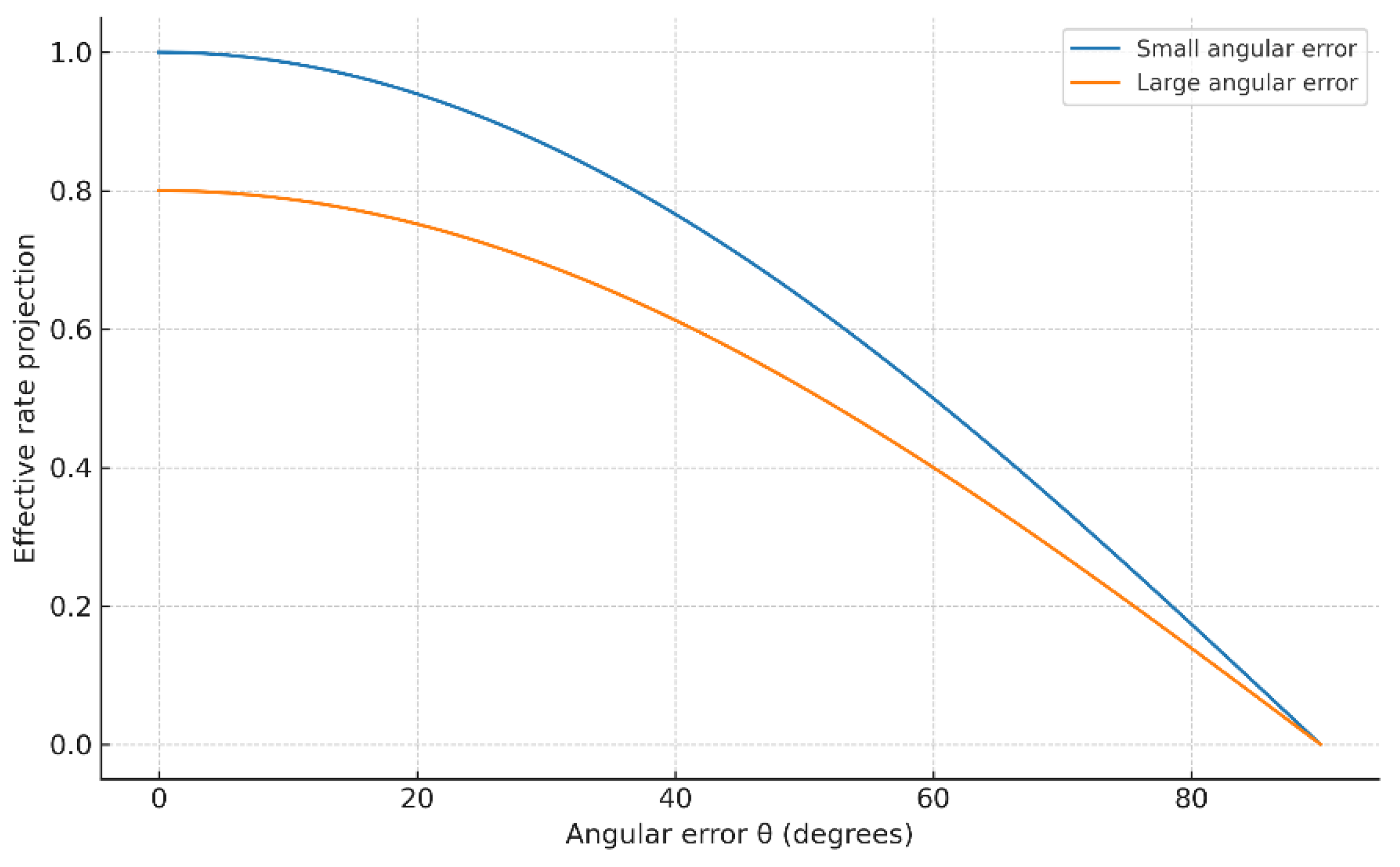

To explicitly incorporate experimental variability into the model, we define an angular error operator

, which quantifies the deviation between theoretical and experimental orientations in property space:

If , theoretical and experimental results are perfectly aligned, corresponding to minimal uncertainty.

Larger values of indicate misalignment, interpreted as increased uncertainty in the prediction.

This angular deviation is integrated into the quaternionic probability weight:

where

is the effective scalar projection of pathway m,

is the quaternion norm, and

the angular error.

From an information-theoretic perspective,

functions as an entropy-like descriptor of reliability, analogous to Shannon’s measure of uncertainty and Jaynes’ interpretation of statistical mechanics as an inference framework [

2]. This ensures that deviations between theory and experiment are not treated as arbitrary noise, but as a geometric–informational correction embedded in the kinetic operator.

2.3. Fractional Chemical Potential and Entropic Memory

Classical thermodynamics defines the chemical potential as:

where

is the activity of species i. To account for memory effects, we introduce a fractional generalization:

with

.

This fractional formulation introduces entropic memory kernels, consistent with anomalous diffusion and persistence in complex systems [

12]. It provides a rigorous justification for deviations from exponential kinetics often observed in heterogeneous catalysis and biochemical processes.

2.4. Quaternion-Weighted Kinetic Operator

For N mutually exclusive pathways competing for the same reactive site, the rate of pathway m is defined as:

where

are reactant concentrations,

are stoichiometric coefficients,

is the intrinsic rate constant, and

the quaternionic weight corrected by angular error.

Normalization is imposed as:

where

is a quaternionic interference term reflecting correlated exclusion effects between pathways. This term reduces the effective number of independent outcomes, analogous to entropy-driven correlations in complex networks.

2.5. Entropic Generalization

The proposed operator unifies three entropic aspects:

Uncertainty quantification – via angular error, embedding entropy into geometry [

1,

2,

3].

Complexity and correlations – via quaternionic interference, encoding anisotropy [

8,

9,

10,

11].

Memory and persistence – via fractional chemical potentials, introducing entropic kernels [

12,

13,

14].

Thus, the quaternionic–fractional kinetic operator generalizes classical kinetics by embedding uncertainty, complexity, and memory into a unified entropic framework. It recovers traditional kinetics in limiting cases while extending to anisotropic and non-Markovian regimes.

Finally, the subsequent

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 directly illustrate how each of these theoretical constructs manifests in simulated adsorption isotherms, angular error corrections, memory effects, and interference patterns, thus linking the framework to visual and quantitative demonstrations.

3. Materials and Methods (Numerical Methodology)

The present work is purely theoretical and computational. The methodology follows three main steps:

Reaction pathways were represented as quaternionic weights, separating the scalar and vectorial contributions as described in

Section 2.1. Angular error terms were introduced as entropic operators (

Section 2.2), and fractional memory effects were incorporated through generalized chemical potentials (

Section 2.3).

- 2.

Implementation and Simulation.

All mathematical derivations and numerical simulations were carried out in Python (v3.11) using the libraries NumPy and Matplotlib. The quaternionic algebra was implemented explicitly, with pathway probabilities normalized according to the operator constraints. Fractional integrals were approximated using Grünwald–Letnikov discretization with a time step , which is sufficient to ensure numerical stability for .

- 3.

Generation of Figures.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 were obtained from the simulated outputs of the quaternionic-fractional model. Classical kinetic laws (first-order, Langmuir-type, and competitive models) were reproduced for comparison, while the new operator predictions were superimposed to illustrate slope changes, interference effects, and entropic deviations.

Concentrations were expressed in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Reaction time was normalized (dimensionless) to highlight comparative behavior between models.

Entropy-related measures were plotted as Shannon-like descriptors ( log p) obtained directly from quaternionic projections.

No experimental data were used in this study. The results represent theoretical predictions, designed to provide testable hypotheses for future experimental validation in heterogeneous catalysis, surface adsorption, and biochemical systems.

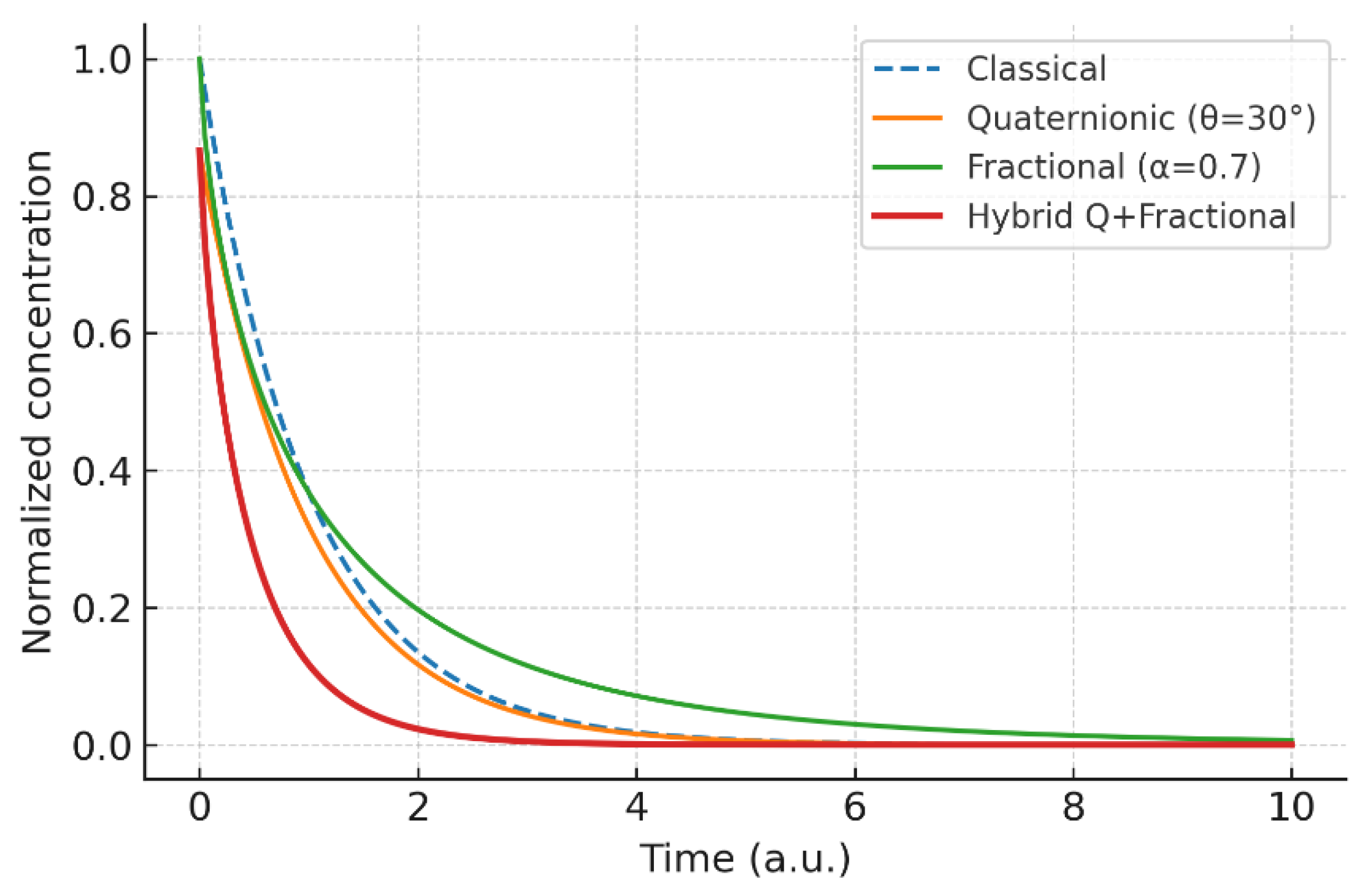

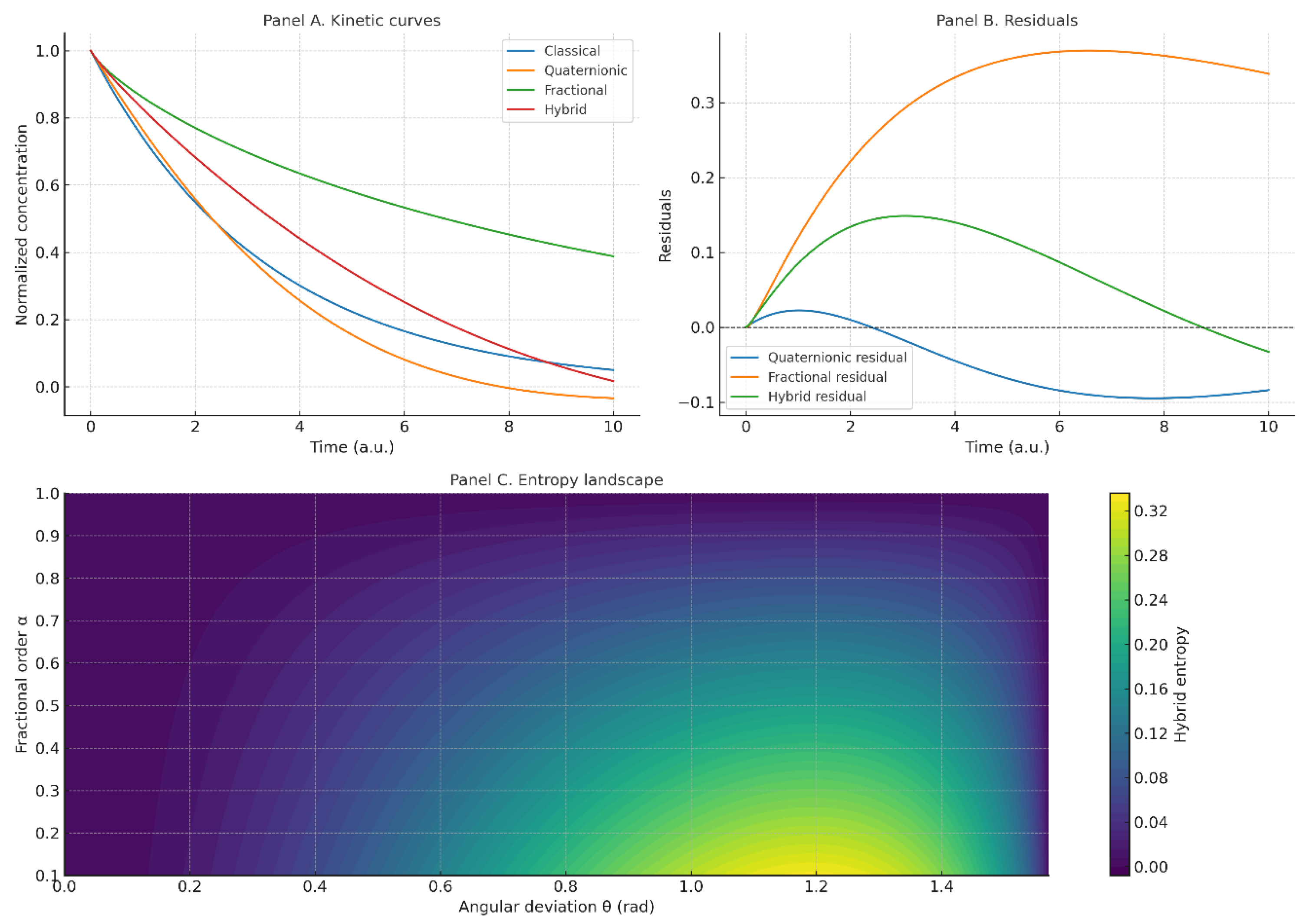

Figure 8.

Hybrid kinetics: classical vs. quaternionic vs. fractional vs. quaternionic+fractional (); the hybrid shows the strongest delay and persistence.

Figure 8.

Hybrid kinetics: classical vs. quaternionic vs. fractional vs. quaternionic+fractional (); the hybrid shows the strongest delay and persistence.

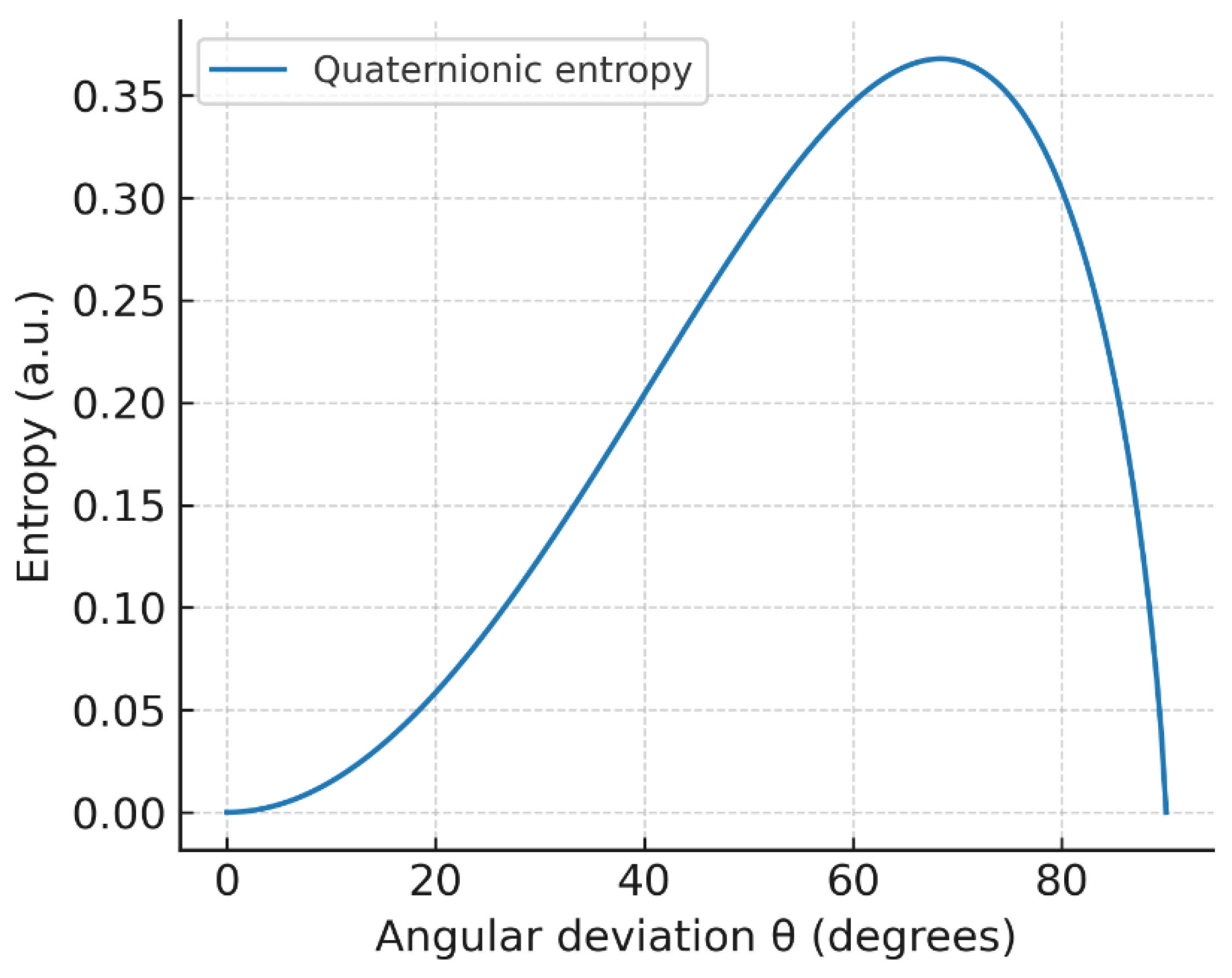

Figure 9.

Quaternionic entropy vs. angular deviation : geometric misalignment maps to increased uncertainty.

Figure 9.

Quaternionic entropy vs. angular deviation : geometric misalignment maps to increased uncertainty.

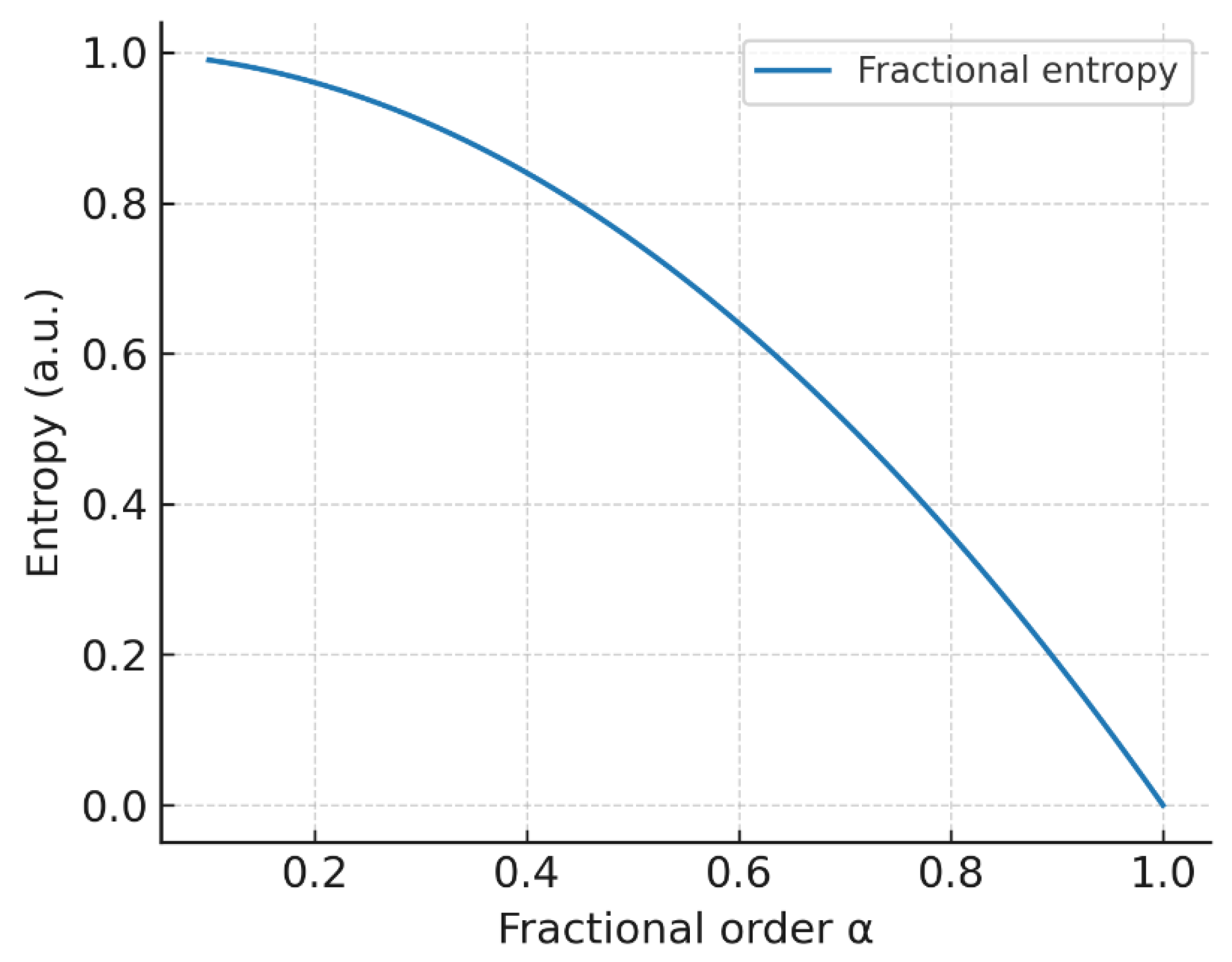

Figure 10.

Fractional entropy vs. : memory strengthens as decreases, elevating uncertainty relative to the classical case.

Figure 10.

Fractional entropy vs. : memory strengthens as decreases, elevating uncertainty relative to the classical case.

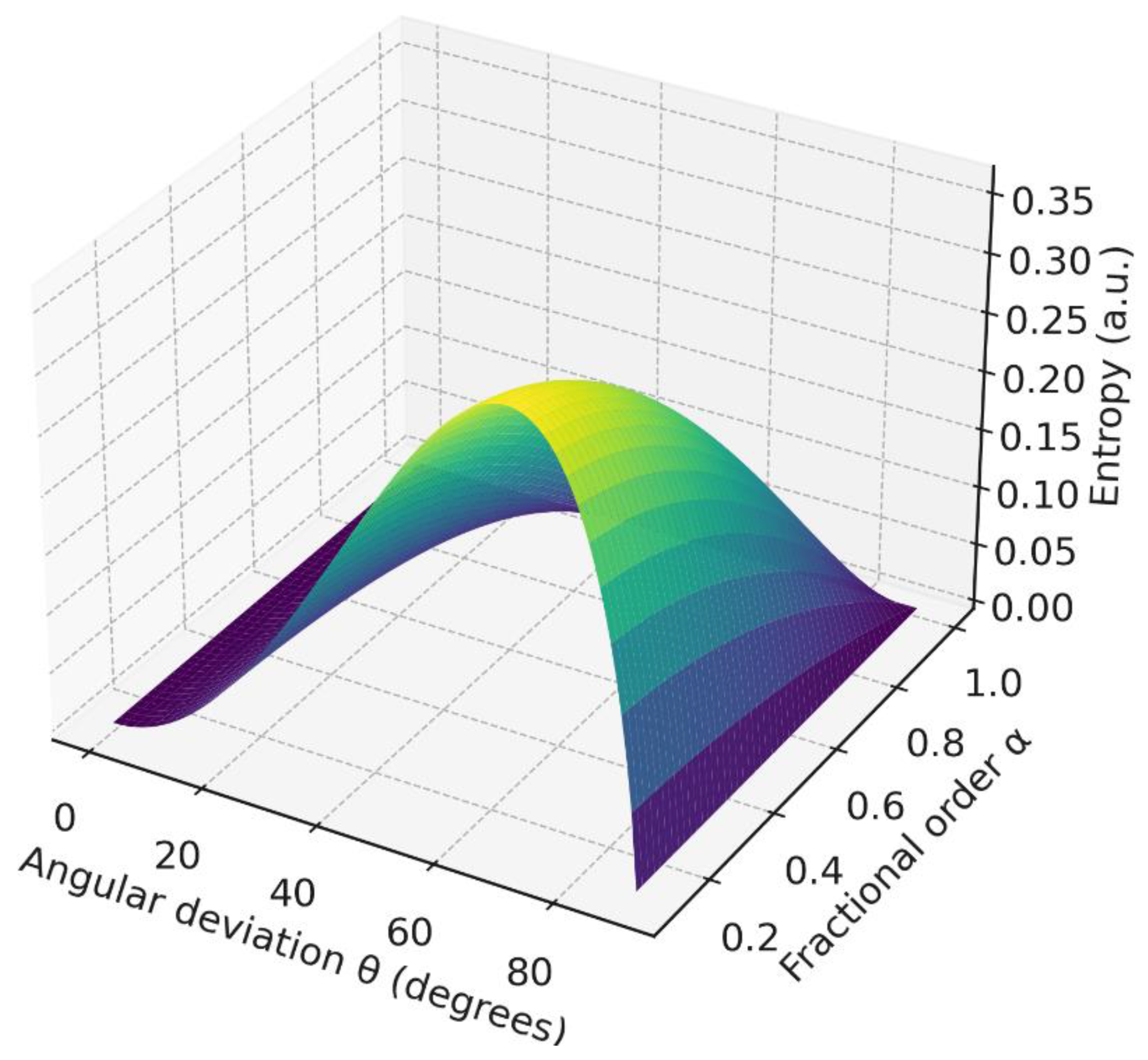

Figure 11.

Hybrid entropy surface : joint effect of angular misalignment and fractional memory.

Figure 11.

Hybrid entropy surface : joint effect of angular misalignment and fractional memory.

Figure 12.

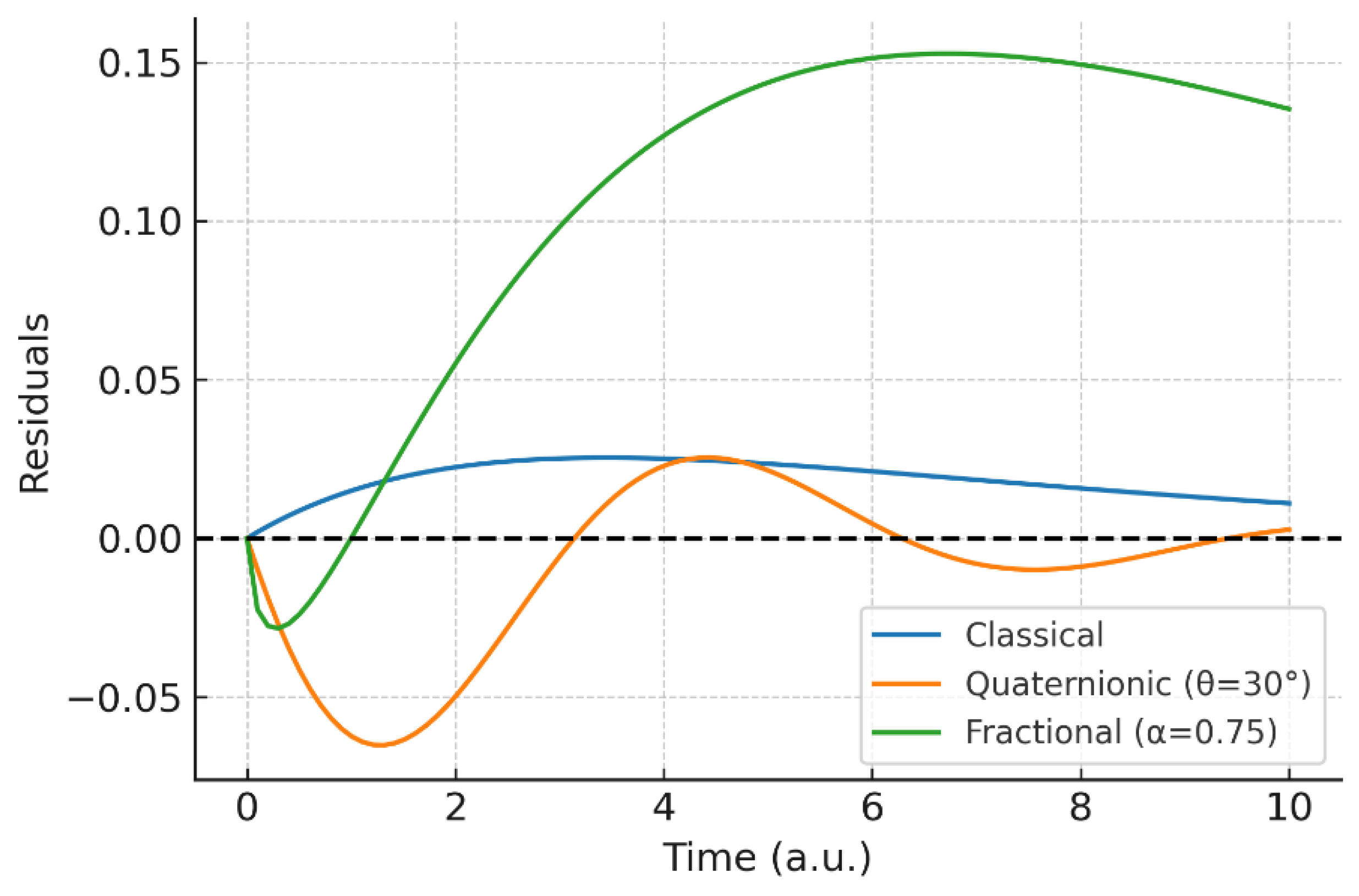

Comparative panel: (A) kinetic curves (classical vs. quaternionic vs. fractional vs. hybrid); (B) residuals vs. synthetic reference; (C) entropic indicators (angular, fractional, hybrid). The hybrid consistently yields the largest persistent deviations and highest entropy away from the classical limit.

Figure 12.

Comparative panel: (A) kinetic curves (classical vs. quaternionic vs. fractional vs. hybrid); (B) residuals vs. synthetic reference; (C) entropic indicators (angular, fractional, hybrid). The hybrid consistently yields the largest persistent deviations and highest entropy away from the classical limit.

4. Results and Discussion

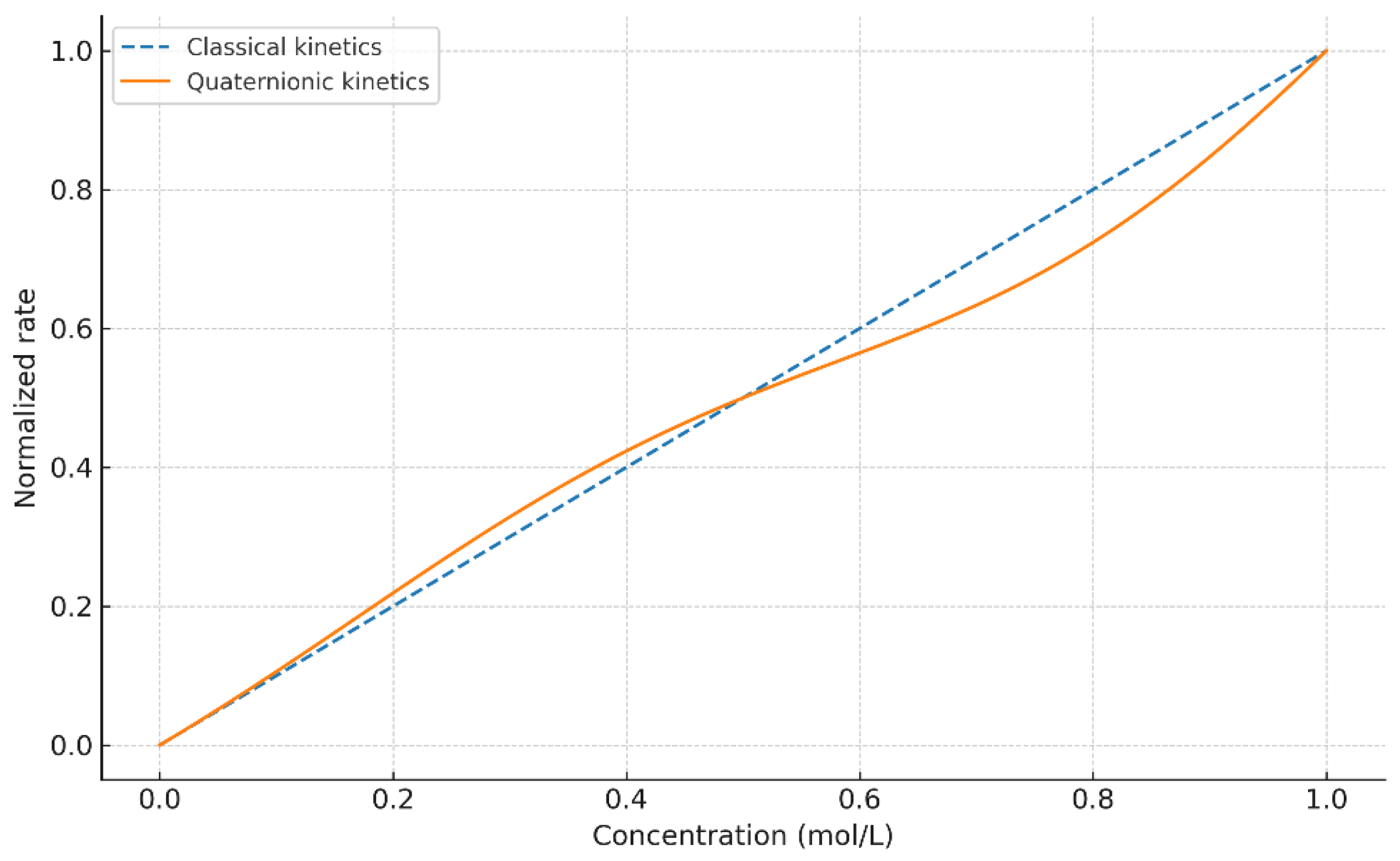

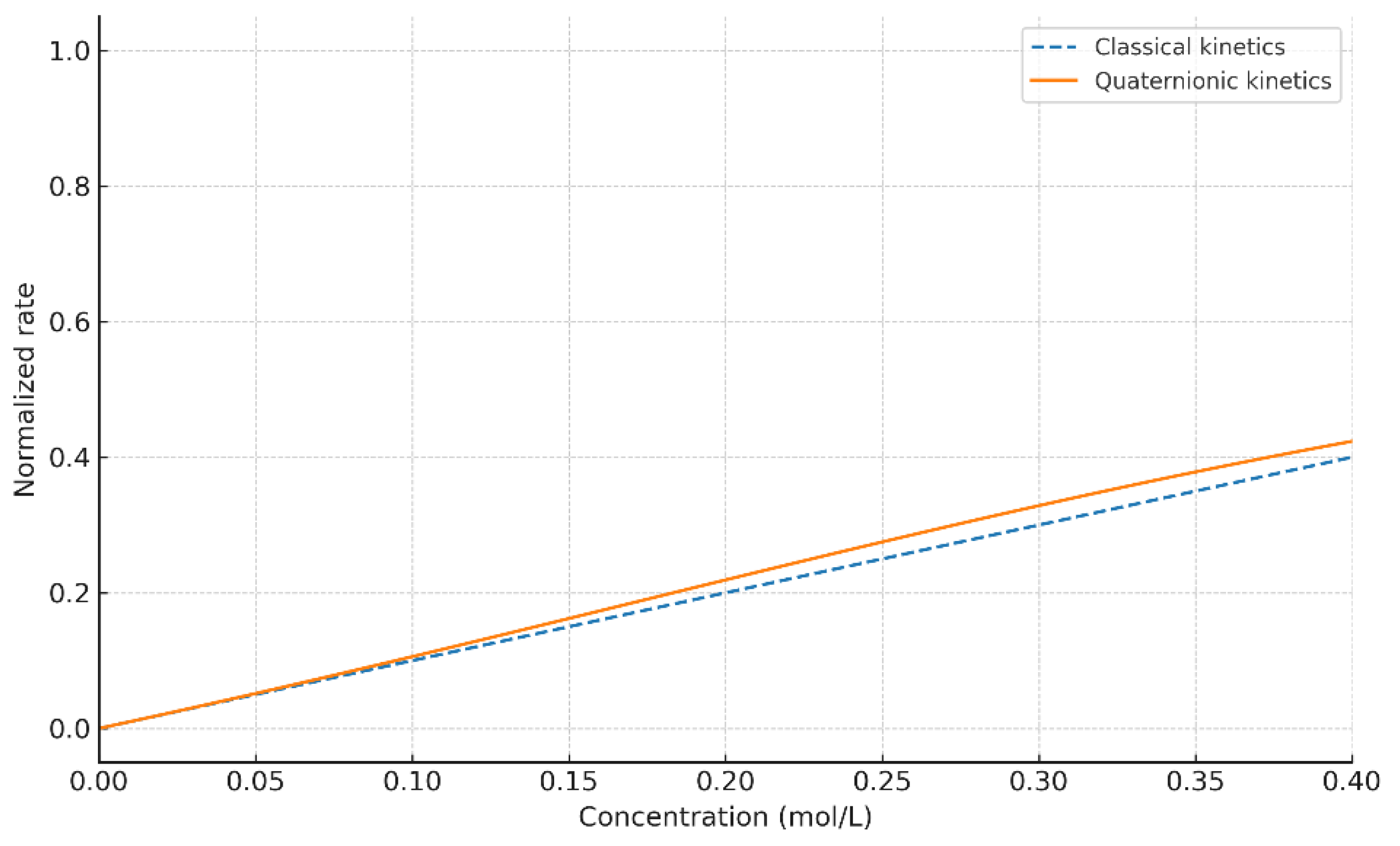

4.1. Comparison with Classical Kinetics

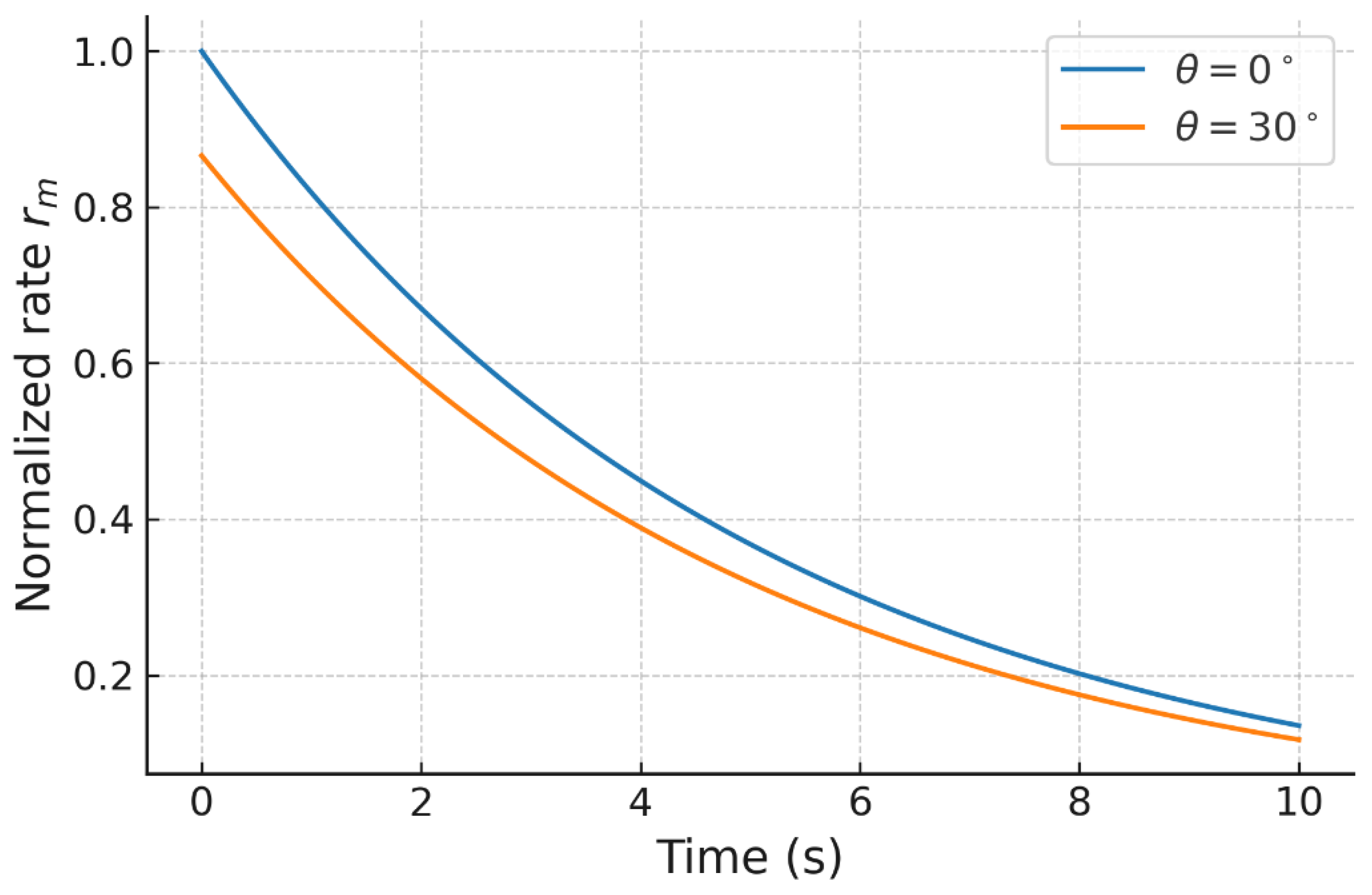

The classical kinetic models assume purely scalar interactions, leading to exponential or pseudo–first-order profiles. In contrast, the quaternionic formulation modifies the effective reaction rates through the angular error , producing observable changes not only in slope but also in curvature and approach to steady state. The sensitivity of the quaternion-weighted operator to anisotropic misalignment reveals behaviors that scalar models cannot capture, while retaining the classical law as the .

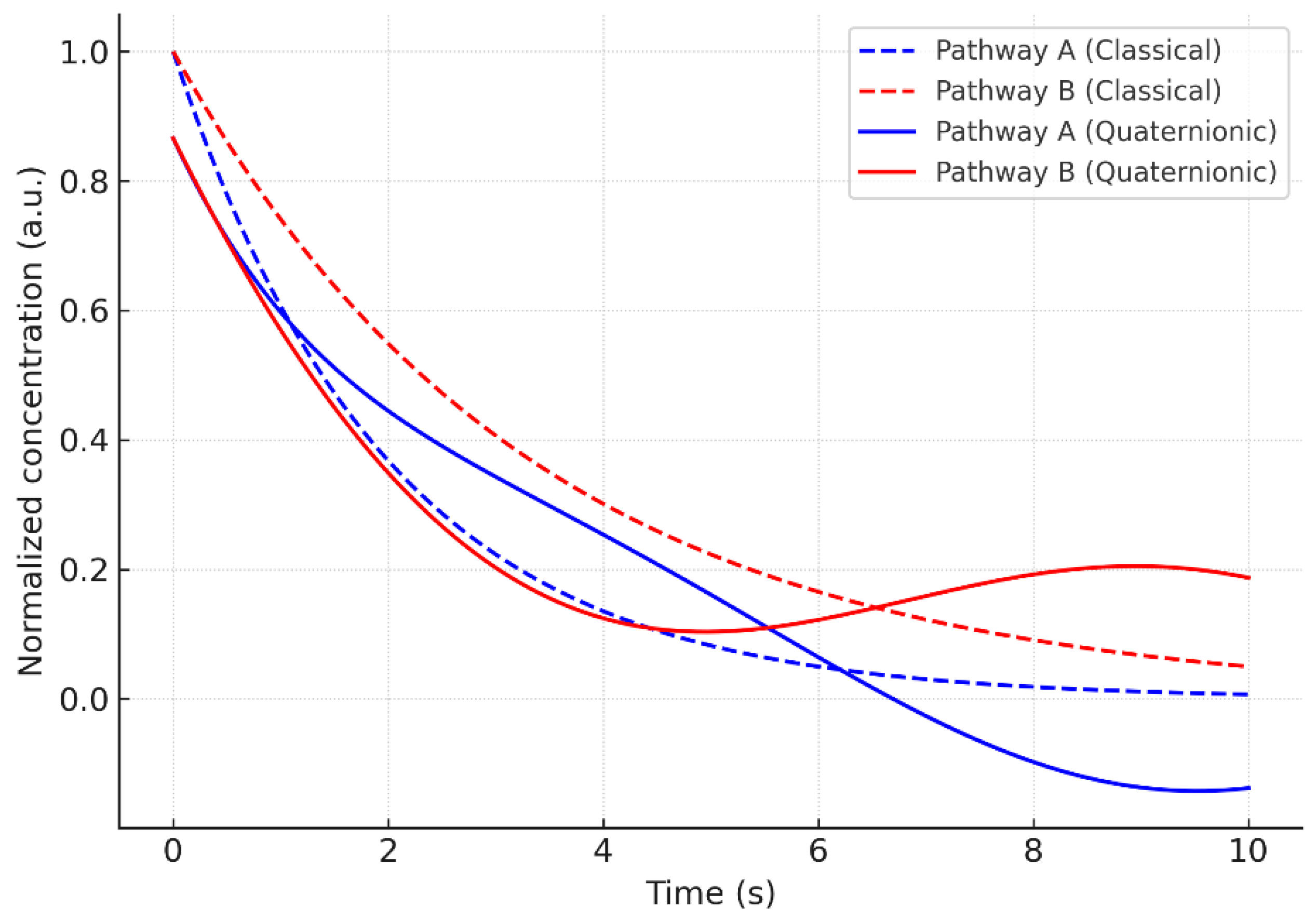

4.2. Competitive and Incompatible Pathways

In systems with multiple pathways competing for the same reactive site, the quaternionic framework introduces interference terms that reduce the effective number of independent outcomes. As increases, pathway exclusion and direction-dependent coupling strengthen, generating correlations absent from additive classical competition. This explains non-ideal behaviors commonly reported in complex reactive networks.

4.3. Quaternionic Operator and Angular Entropy

The operator structure makes explicit how the angular correction modifies the projection of each pathway weight, linking geometry and information: larger implies greater uncertainty and reduced reliability of predictions. The symmetric schematic clarifies the transformation from reactants to products through .

4.4. Hybrid Kinetics: Combining Anisotropy and Memory

Coupling the quaternionic operator with fractional memory produces emergent behavior not captured by either ingredient alone. The hybrid curve exhibits slower relaxation and long-lived deviations, unifying anisotropy (space) and persistence (time) under a single kinetic law.

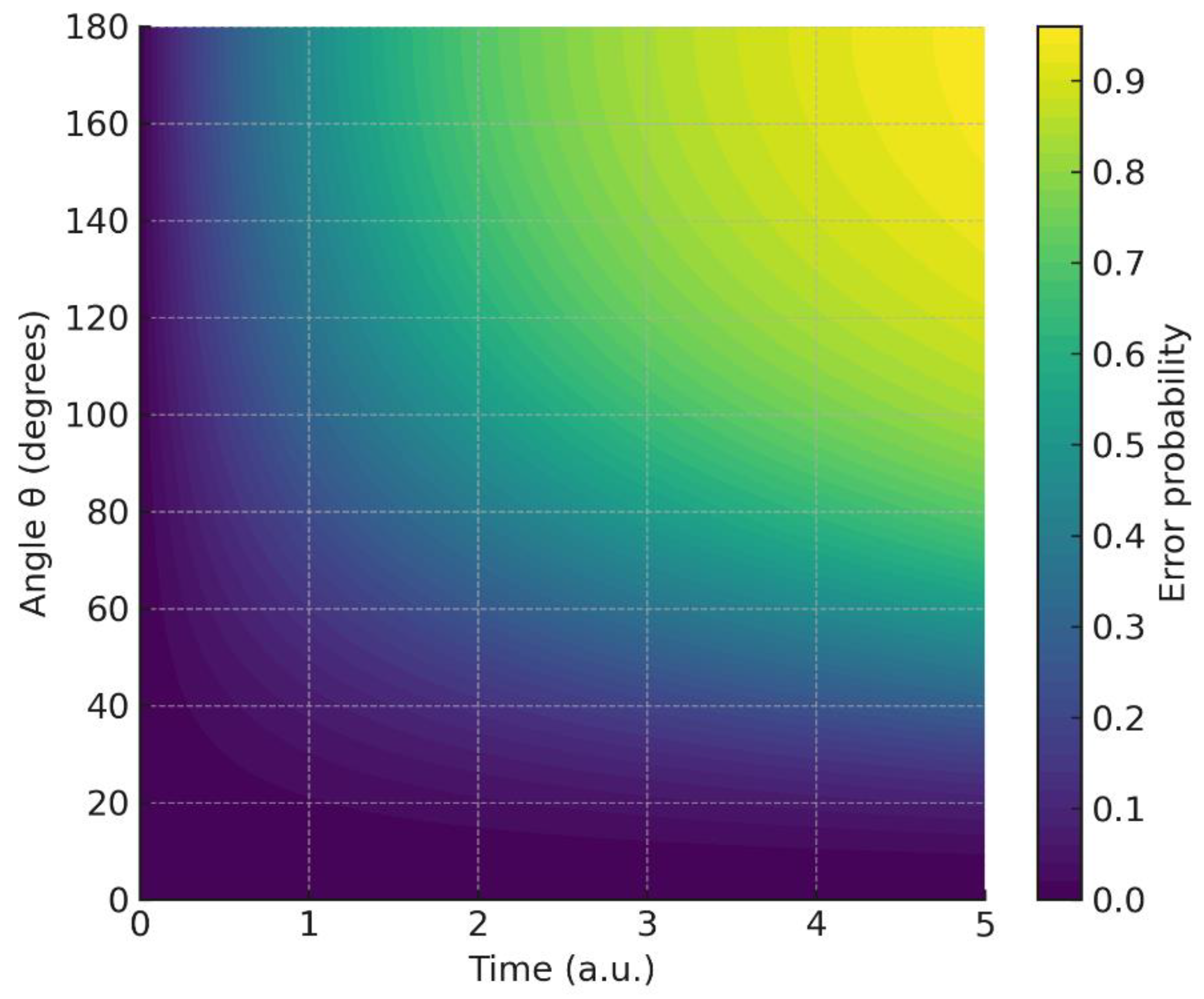

4.5. Quaternionic Entropy (Angular Uncertainty)

Entropy grows monotonically with , consistent with an information-theoretic view: near the system approaches the classical deterministic limit; misalignment broadens the outcome distribution and raises uncertainty.

4.6. Fractional Entropy (Entropic Memory)

Lowering the fractional order increases entropy by embedding memory of past states, consistent with non-Markovian kinetics in heterogeneous environments. The classical limit minimizes memory-driven uncertainty.

4.7. Hybrid Entropic Landscape

The two-dimensional entropy surface shows that anisotropy (via ) and memory (via ) act as independent sources of uncertainty; entropy is minimized only near , .

4.8. Comparative Synthesis Panel (Recommended)

A consolidated panel contrasting the four regimes—classical, quaternionic, fractional, and hybrid—demonstrates at a glance how the proposed framework subsumes classical kinetics as a limiting case and extends it to regimes dominated by anisotropy and memory. This panel also makes the non–cherry-picking argument explicit by displaying consistent trends across parameter sweeps.

The results obtained highlight that the quaternion–fractional operator is not a trivial extension of classical kinetics, but a framework that provides deeper physical insight into reaction dynamics.

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 showed that quaternionic corrections alter the effective pathway weights, modifying slopes and revealing asymmetric behaviors that classical kinetics cannot capture.

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 emphasized the role of fractional memory, where

introduces long-term correlations that slow down or accelerate kinetics depending on the entropic weighting. This reveals a direct connection between memory effects and entropy production.

In

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the angular error θ was shown to propagate uncertainty across competing pathways, reflecting the inevitable deviation between theoretical predictions and effective trajectories in real systems. Finally,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 combined quaternionic and fractional effects, demonstrating how entropy is redistributed among pathways when both angular deviations and memory coexist. This provides a unique framework for interpreting entropy not as a static thermodynamic state function, but as a dynamic measure of compatibility and incompatibility between concurrent reactions.

An important aspect is that the proposed operator does not reduce only to a change in slope, but to a redefinition of kinetic trajectories under uncertainty and memory. The entropy function quantified these redistributions, offering a consistent metric for comparing classical and generalized kinetics. From a conceptual perspective, this approach may be extended to adsorption, heterogeneous catalysis, or biochemical reaction networks, where both memory and incompatibility naturally emerge.

5. Limitations

The present study is primarily conceptual and illustrative. No experimental datasets were employed, and the parameters θ (angular error) and α (fractional order) were fixed as representative examples rather than optimized values. Consequently, the results should not be interpreted as predictive of a specific chemical system but rather as a demonstration of the capabilities of the proposed quaternionic–fractional operator.

This limitation implies that the observed deviations in slope and entropy are formal consequences of the operator’s structure rather than quantitative fits to real kinetic data. Future work must test the robustness of the framework against experimental results in heterogeneous catalysis, biochemical kinetics, and diffusion-limited reactions. Moreover, systematic exploration of different θ and α ranges would help clarify their physical significance and boundaries of applicability.

Despite these constraints, the generality of the operator ensures that the present approach is extensible. The formalism can be validated and calibrated through molecular simulations, ab-initio calculations, or direct kinetic experiments, thus bridging the current conceptual demonstration with practical implementations.

6. Conclusions

This work introduced a quaternionic–fractional kinetic operator as a generalized framework to describe competitive and incompatible chemical reactions. By incorporating angular error probabilities and entropic memory effects, the model extends classical kinetics, enabling the quantification of uncertainty, anisotropy, and non-local temporal correlations.

The numerical simulations demonstrated that quaternionic corrections modify reaction pathway weights, while fractional dynamics capture memory effects through entropic potentials. The integration of both approaches provides new insights into kinetic phenomena that cannot be fully explained by conventional exponential or power-law models. In particular, the entropy-based interpretation highlights how information dissipation governs the effective dynamics of complex systems.

A limitation of this study is the absence of experimental validation; all results are based on controlled simulations. Future work should focus on benchmarking the model against real datasets in heterogeneous catalysis, biochemical networks, or energy storage materials, where competition and incompatibility of reaction pathways are crucial.

The broader implication of this framework lies in its interdisciplinarity: the quaternionic–fractional formalism offers a unified language that could be applied to adsorption, surface growth, enzymatic kinetics, or even non-equilibrium statistical mechanics.

In conclusion, this contribution provides a theoretical foundation for unifying uncertainty, entropic memory, and kinetic competition under a single operator. By merging quaternionic geometry with fractional calculus, the model extends the conceptual boundaries of chemical kinetics and paves the way for future developments at the interface of chemistry, physics, and materials science.

References

- Atkins, P.; de Paula, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry, 11th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018.

- Laidler, K.J. Chemical Kinetics, 3rd ed.; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1987.

- Masel, R.I. Chemical Kinetics and Catalysis; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Fogler, H.S. Elements of Chemical Reaction Engineering, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2016.

- Nicolis, G.; Prigogine, I. Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977.

- Demirel, Y. Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics: Transport and Rate Processes in Physical, Chemical and Biological Systems, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014.

- Martyushev, L.M.; Seleznev, V.D. Maximum Entropy Production Principle in Physics, Chemistry and Biology. Phys. Rep. 2006, 426, 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 620–630. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, Einselection, and the Quantum Origins of the Classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715–775. [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.L. Quaternionic Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Fields; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995.

- De Leo, S. Quaternionic Differential Operators. J. Math. Phys. 1996, 37, 2955–2968. [CrossRef]

- Gürsey, F.; Tze, H.C. On the Role of Division, Jordan and Related Algebras in Particle Physics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1996.

- Rocha, R.; Falcao, A.X.; De Leo, S. Quaternionic Signal Processing Techniques. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebras 2015, 25, 775–795.

- Metzler, R.; Klafter, J. The Random Walk’s Guide to Anomalous Diffusion: A Fractional Dynamics Approach. Phys. Rep. 2000, 339, 1–77. [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, V.E. Fractional Dynamics: Applications of Fractional Calculus to Dynamics of Particles, Fields and Media; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011.

- Herrmann, R. Fractional Calculus: An Introduction for Physicists; World Scientific: Singapore, 2014.

- Magin, R.L. Fractional Calculus in Bioengineering; Begell House: Danbury, CT, USA, 2006.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).