Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

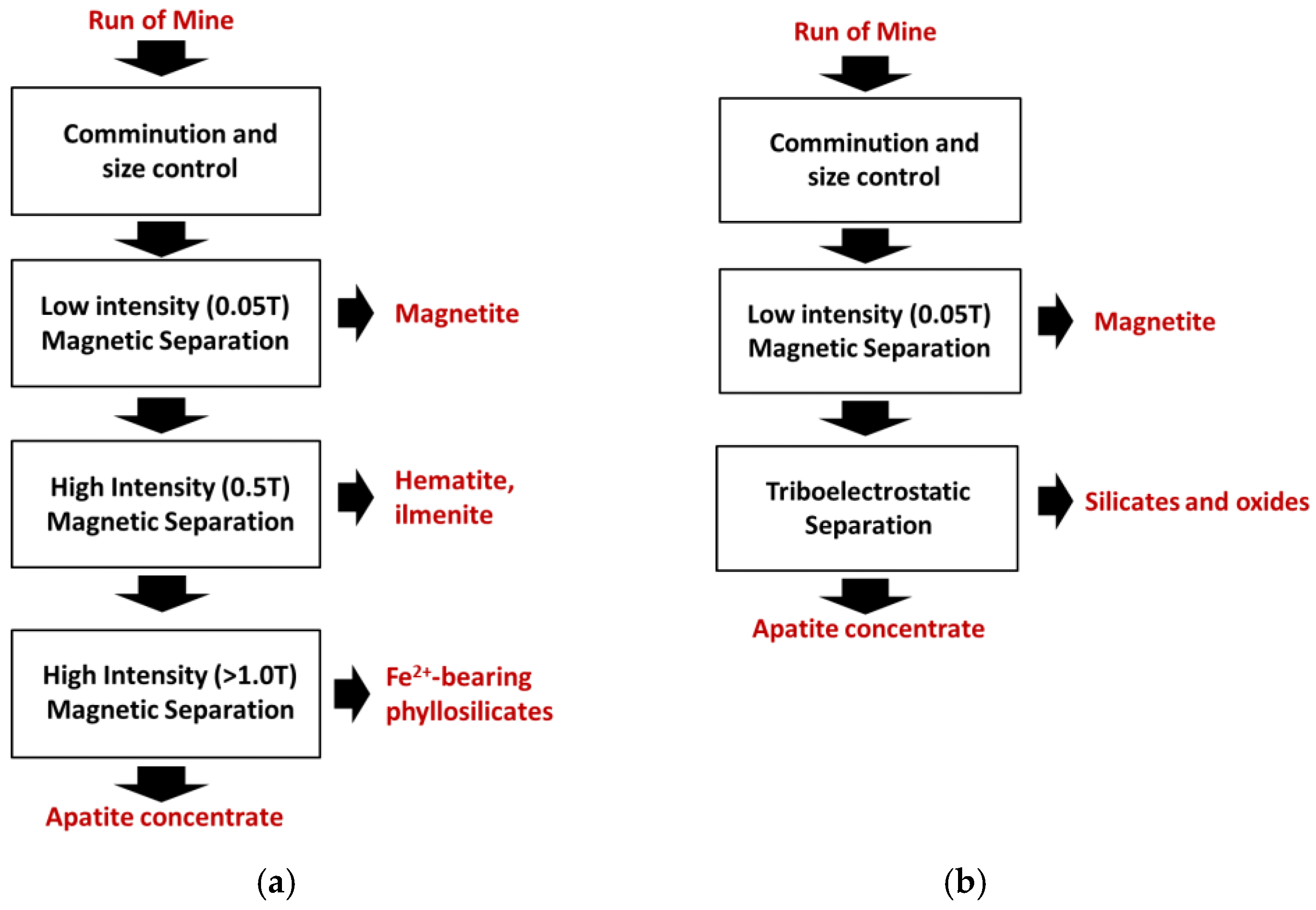

2. Background

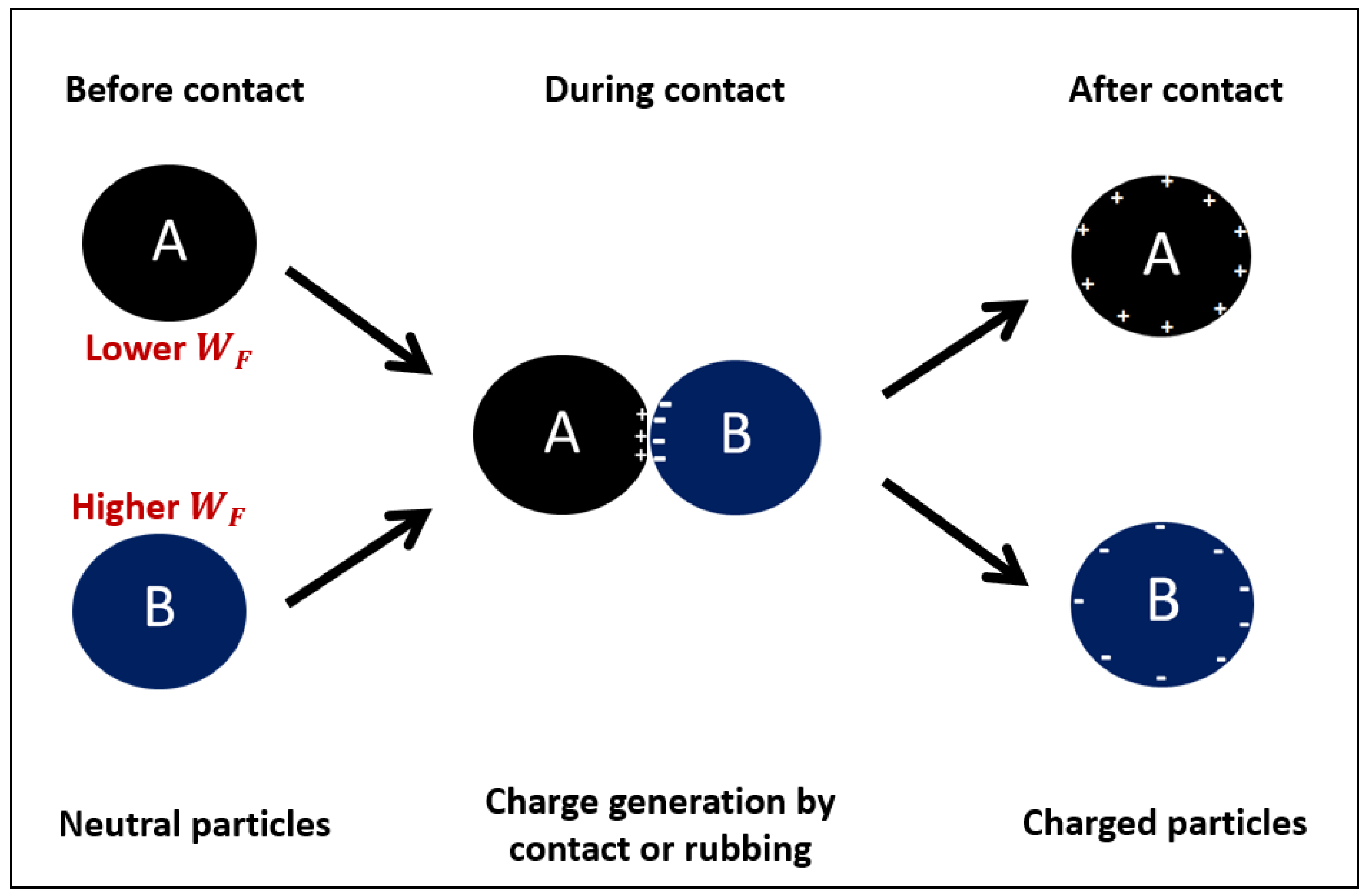

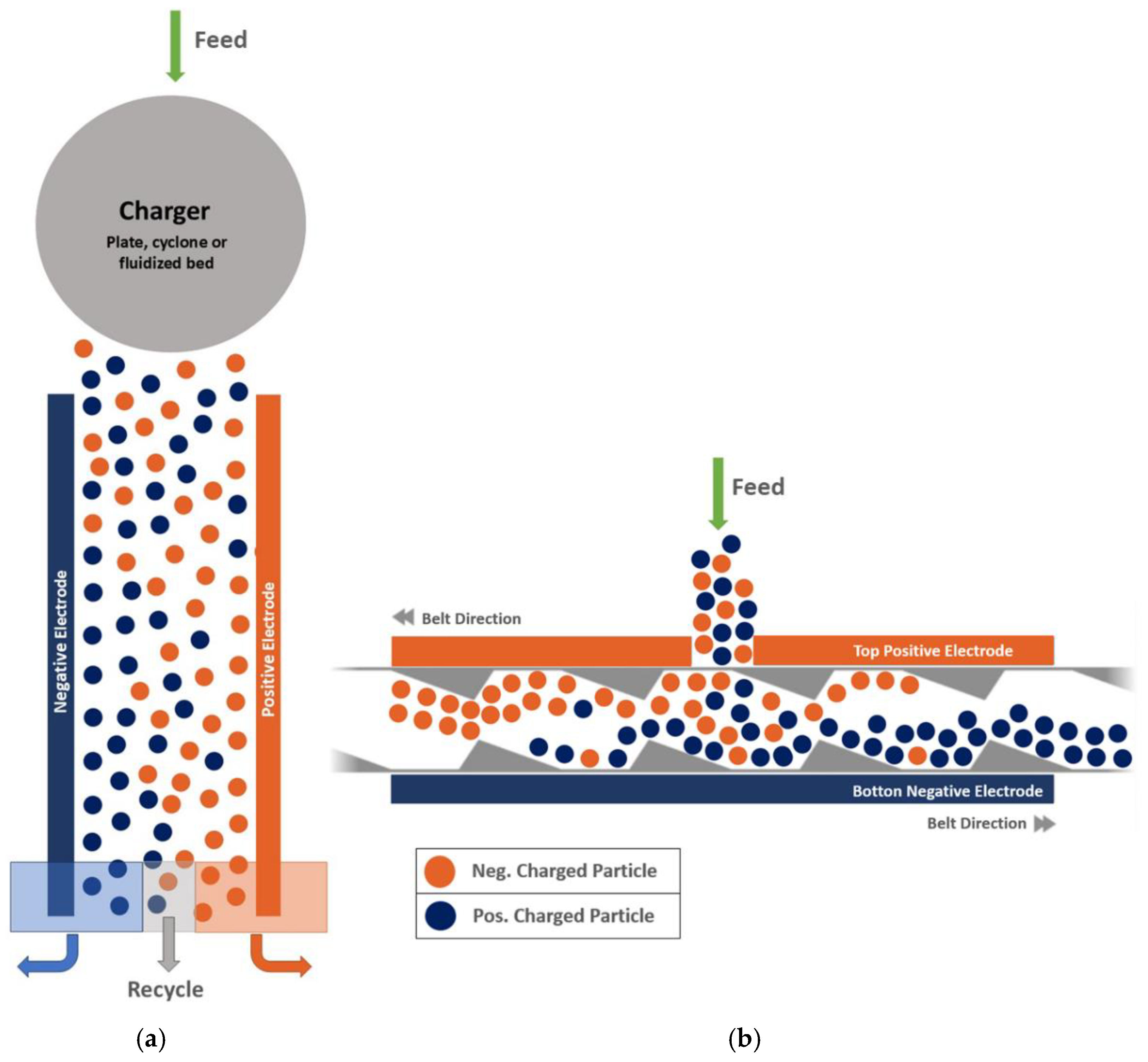

2.1. Factors Influencing the Separation Process

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Mineral Sample That Fed the Pilot Tests

3.2. Characterization of the TM and Products Yielded by the TES

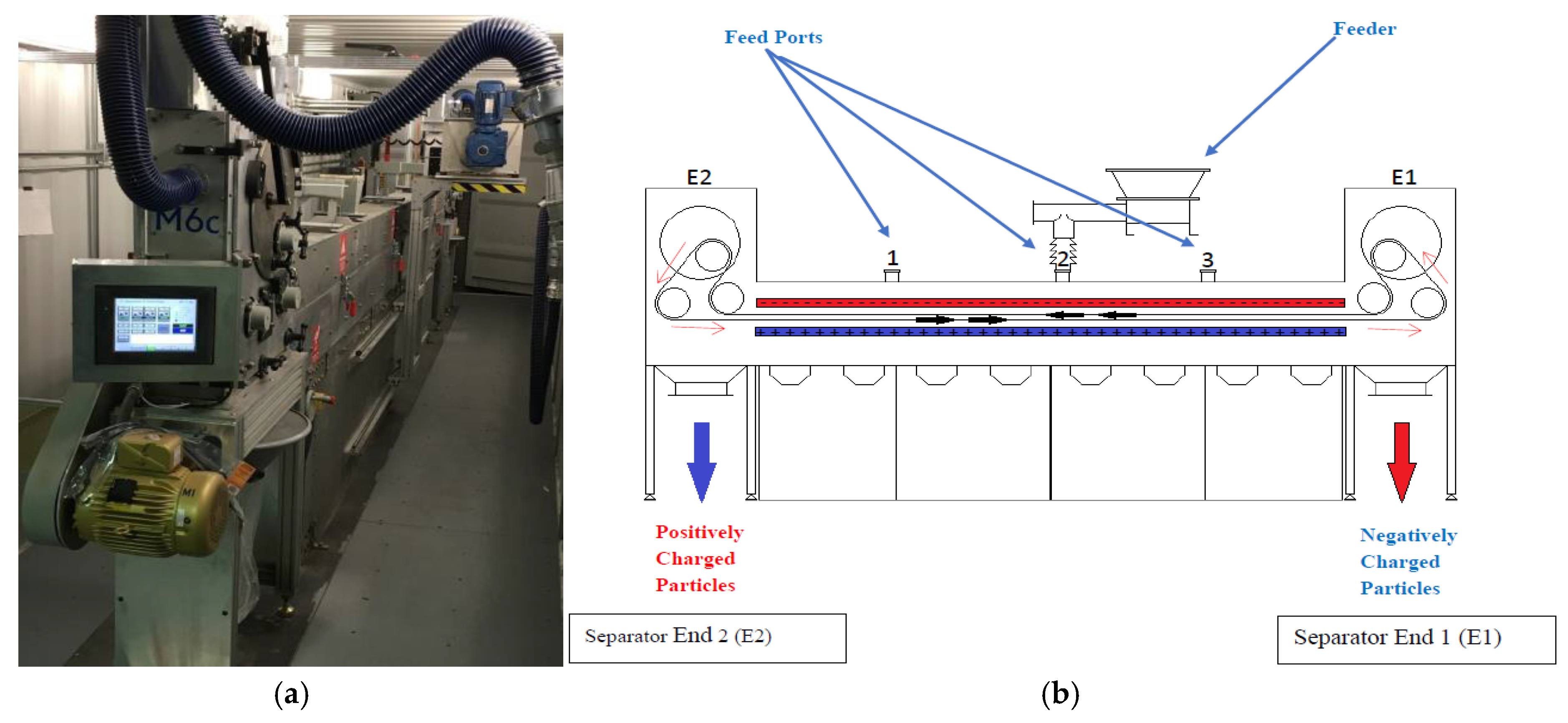

3.3. Triboelectrostatic Belt Separator (TBS): Description and Mode of Operation

3.4. Pilot Tests

4. Results and Discussion

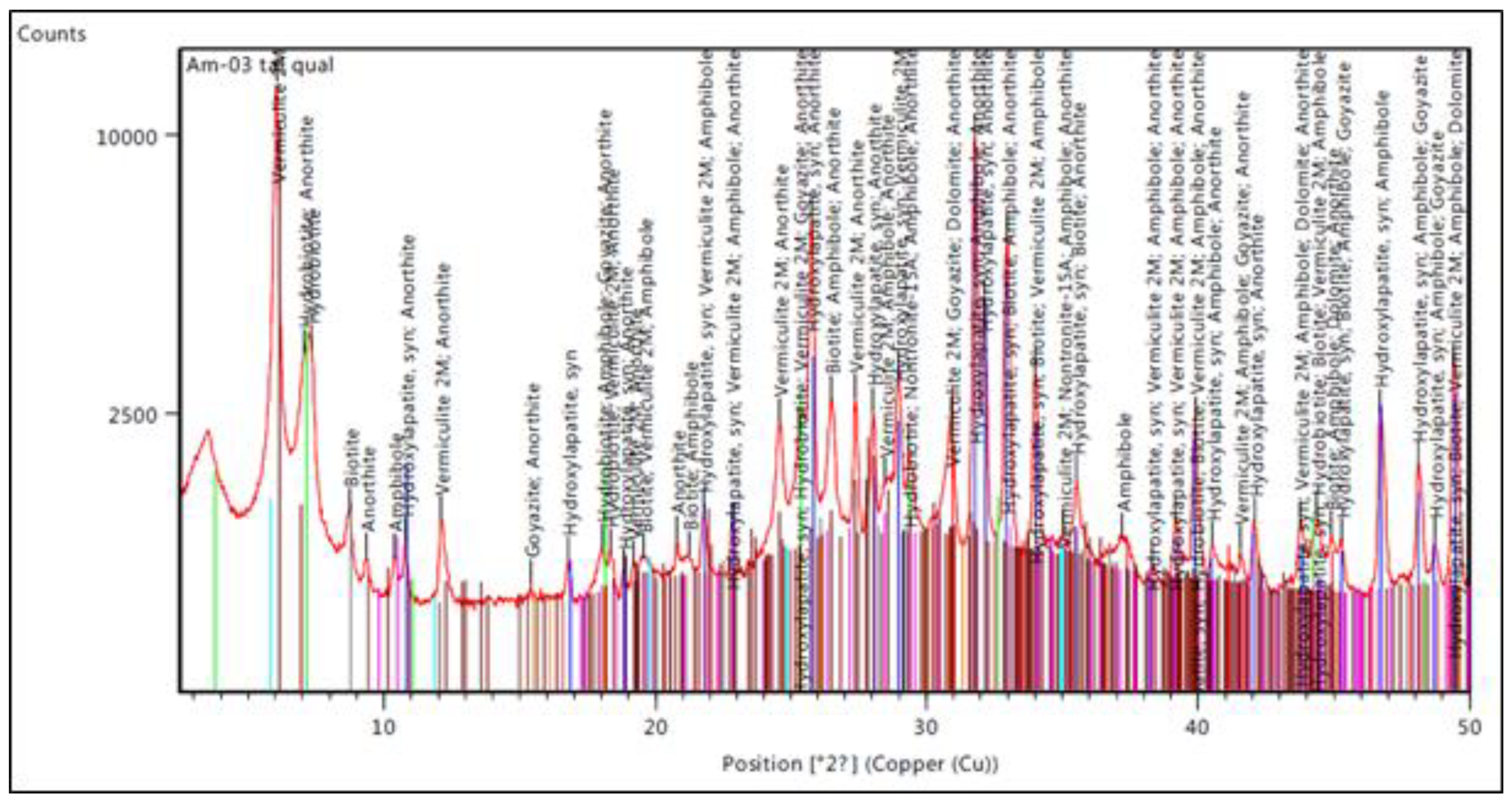

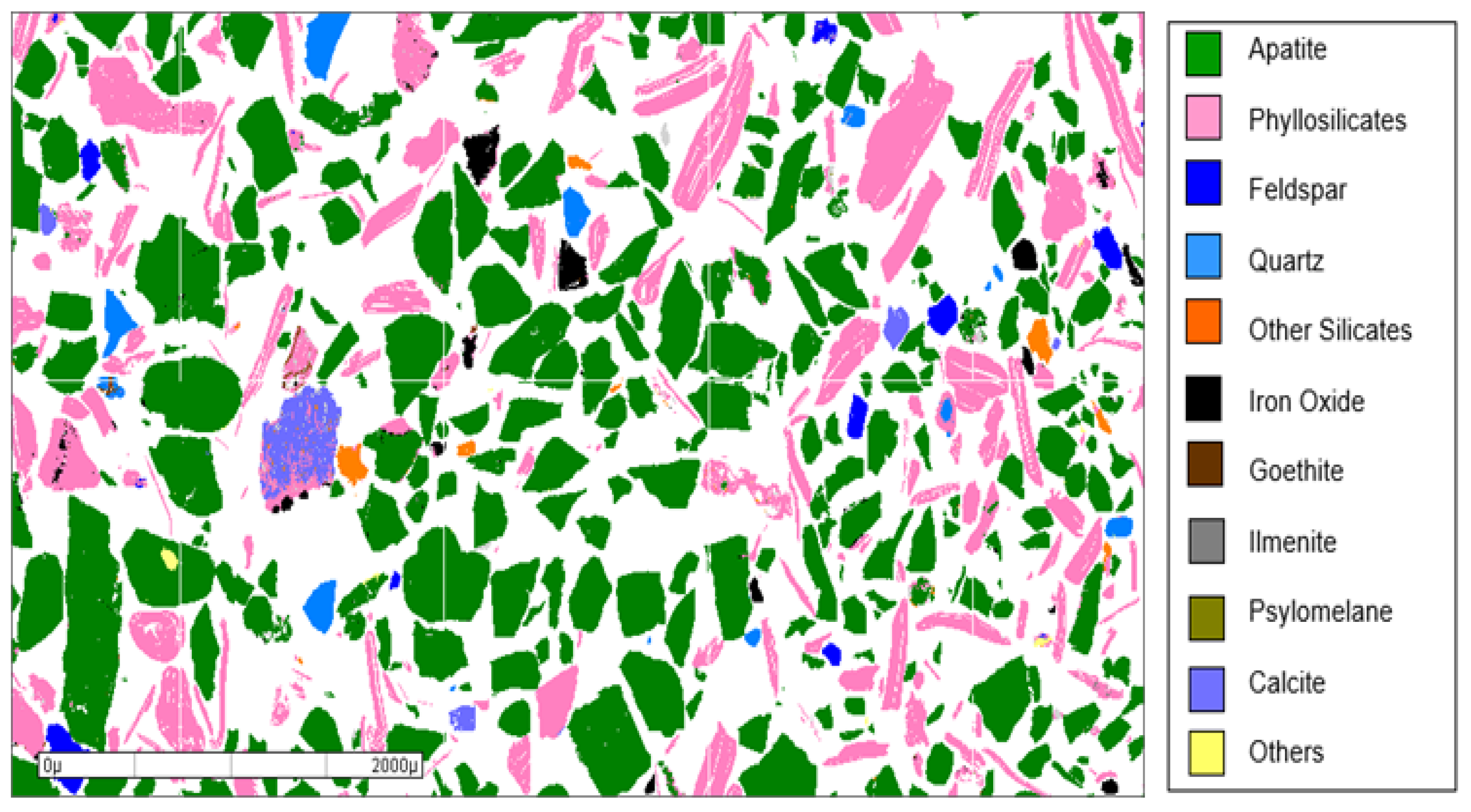

4.1. Characterization of the Testing Material (TM)

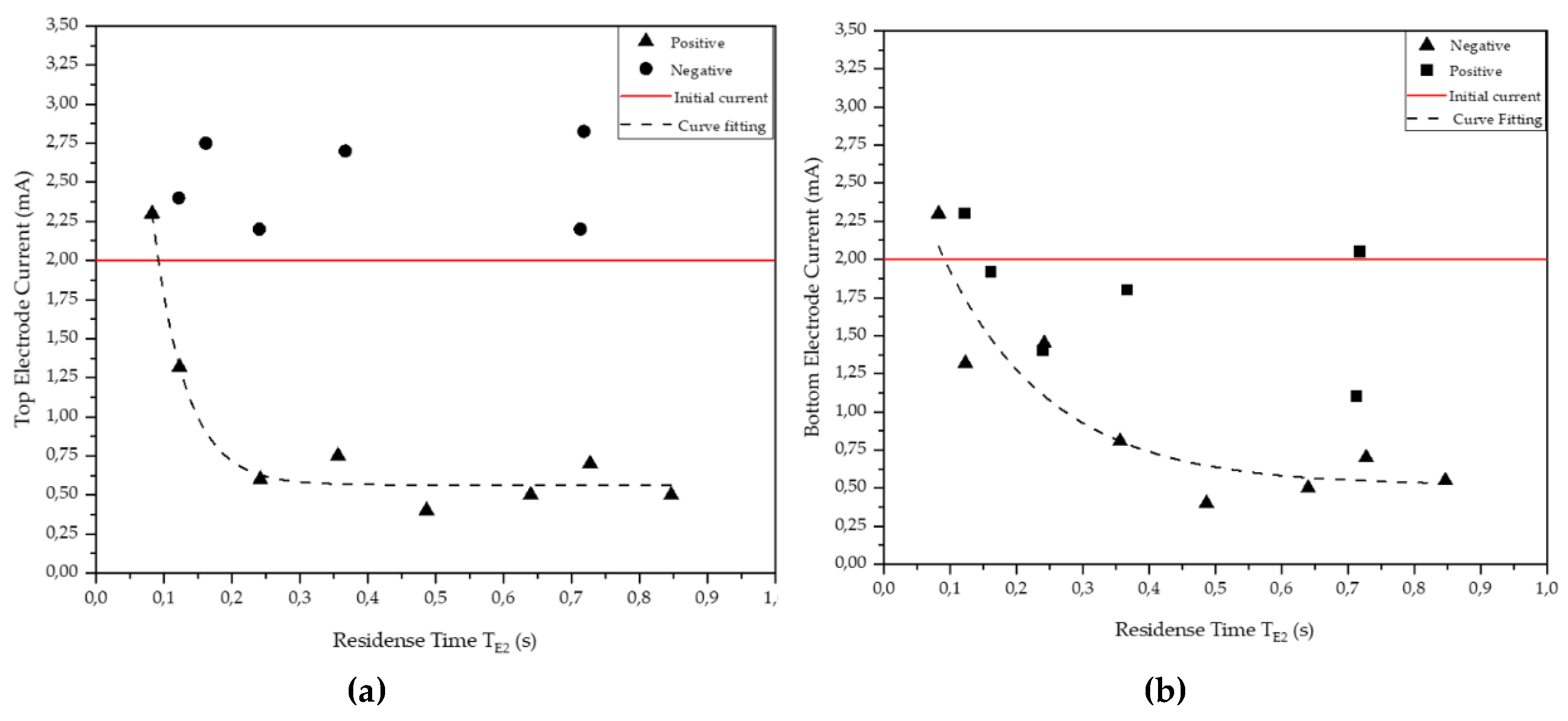

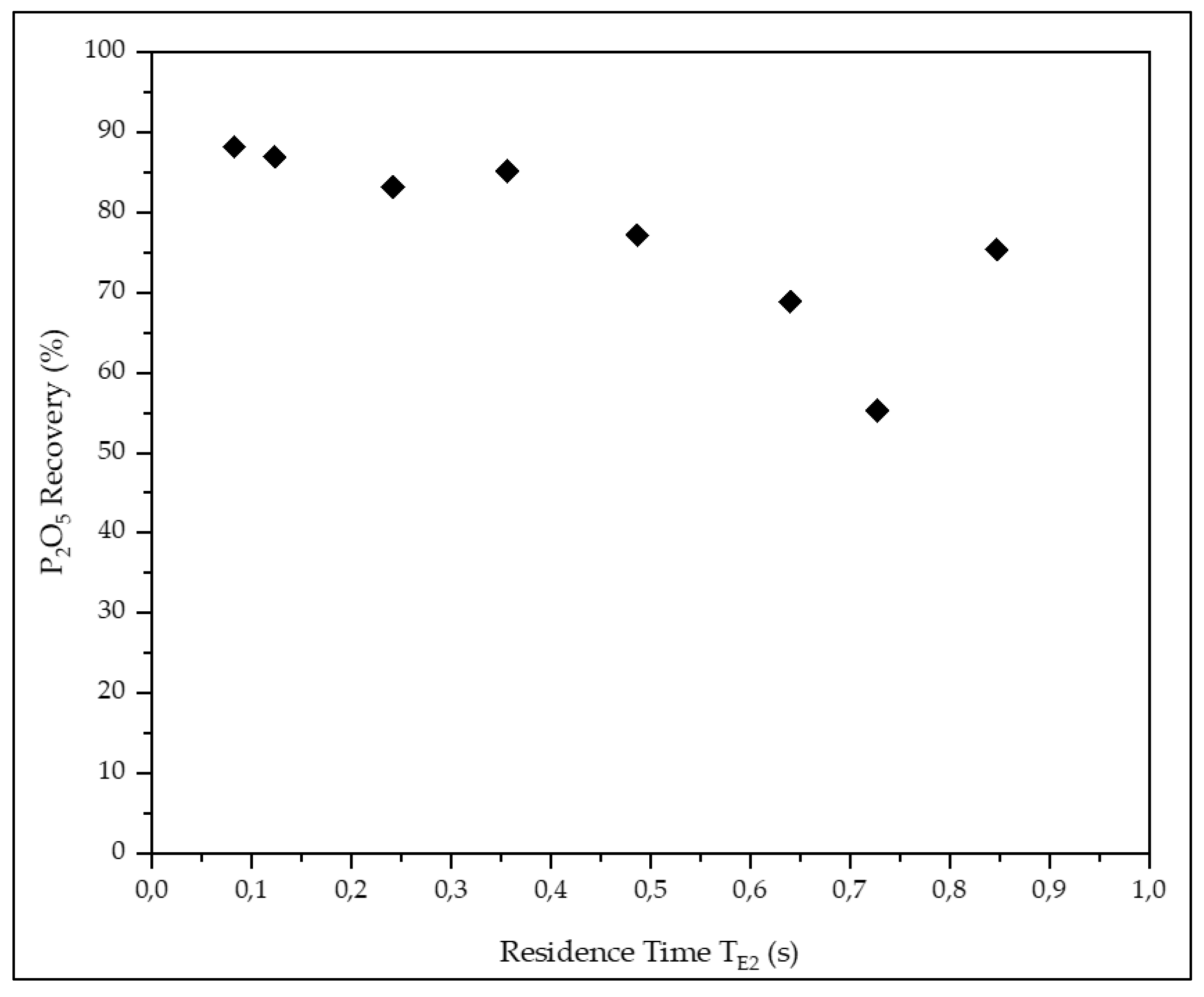

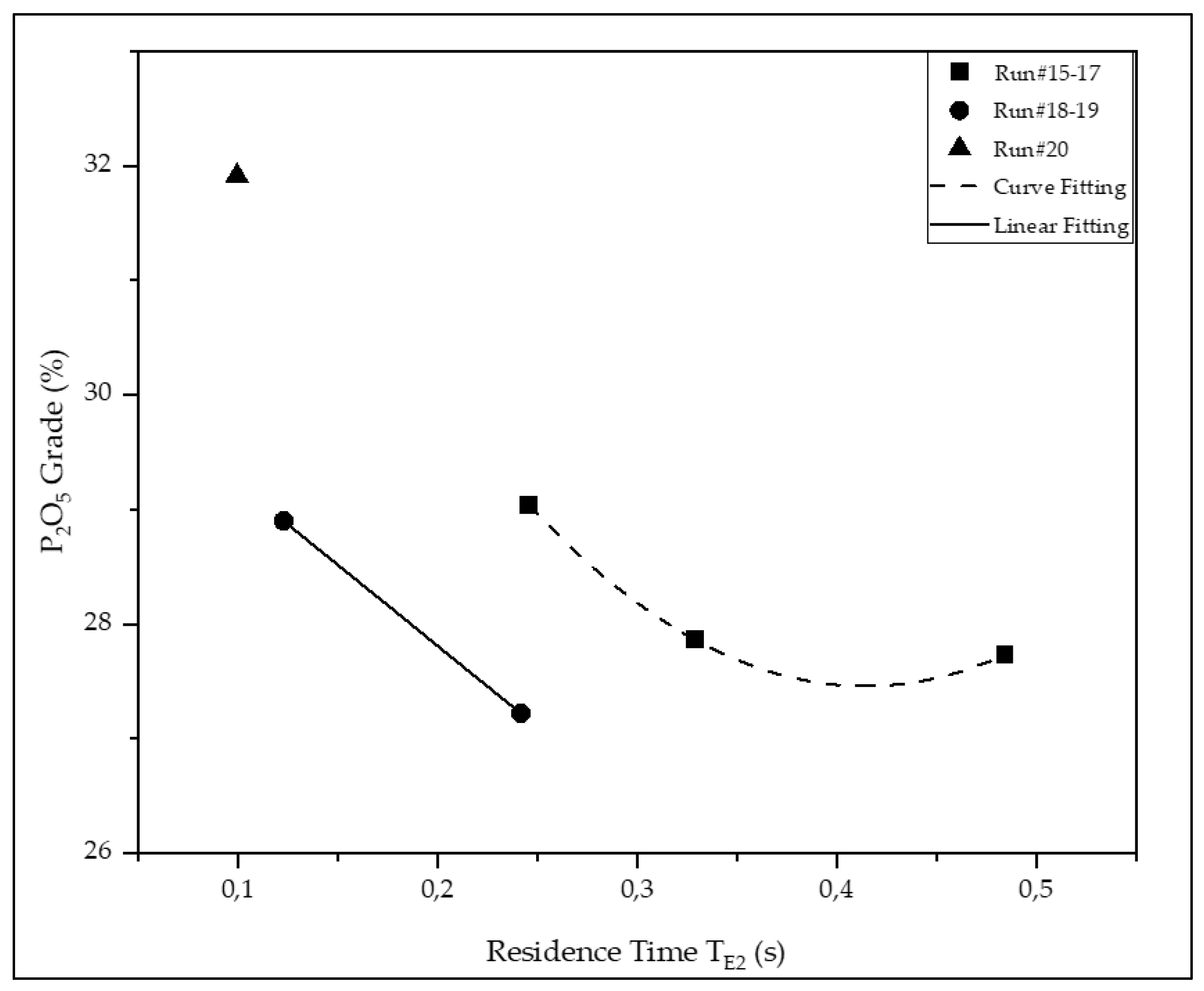

4.2. Results from Triboelectrostatic Separation Tests

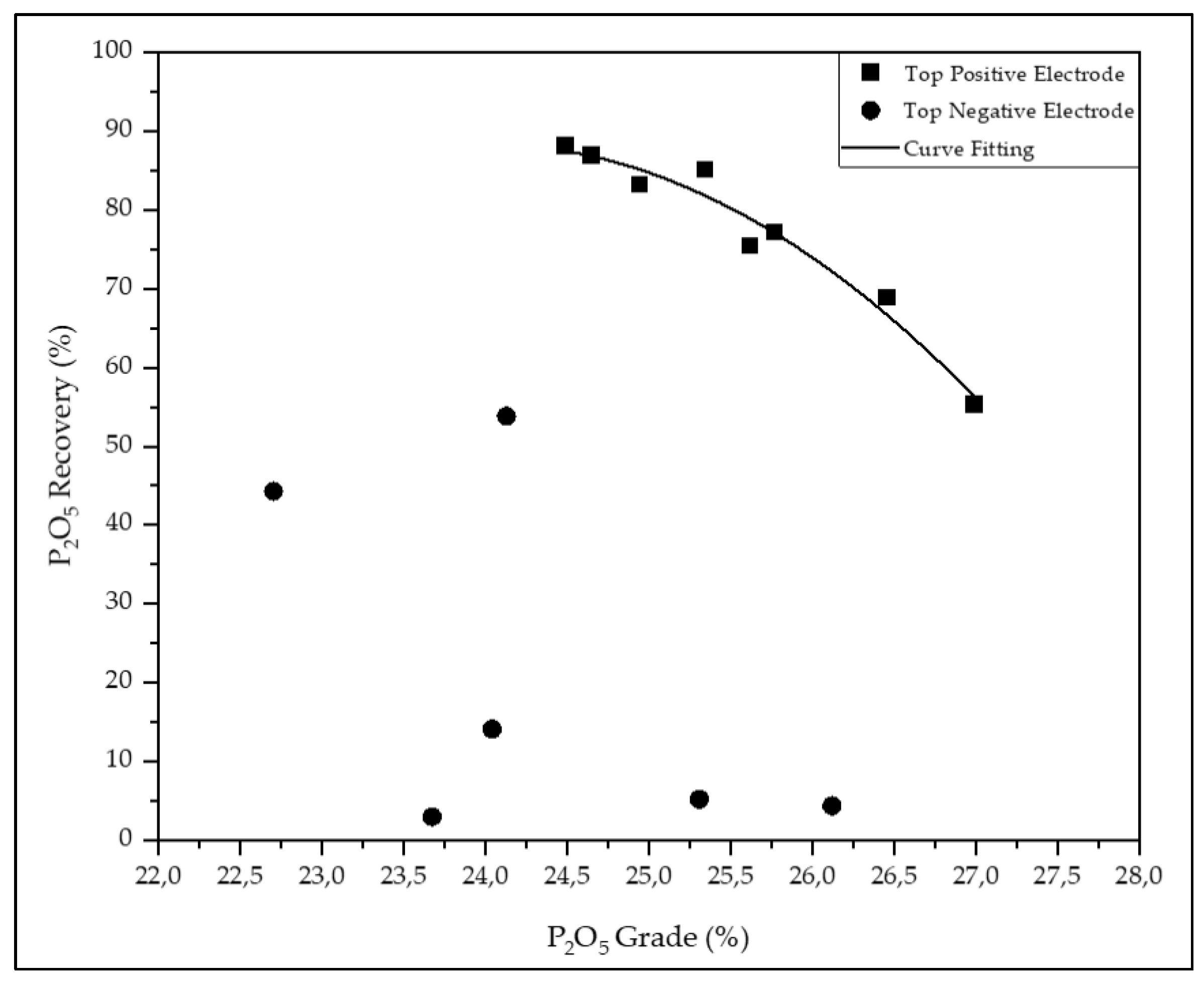

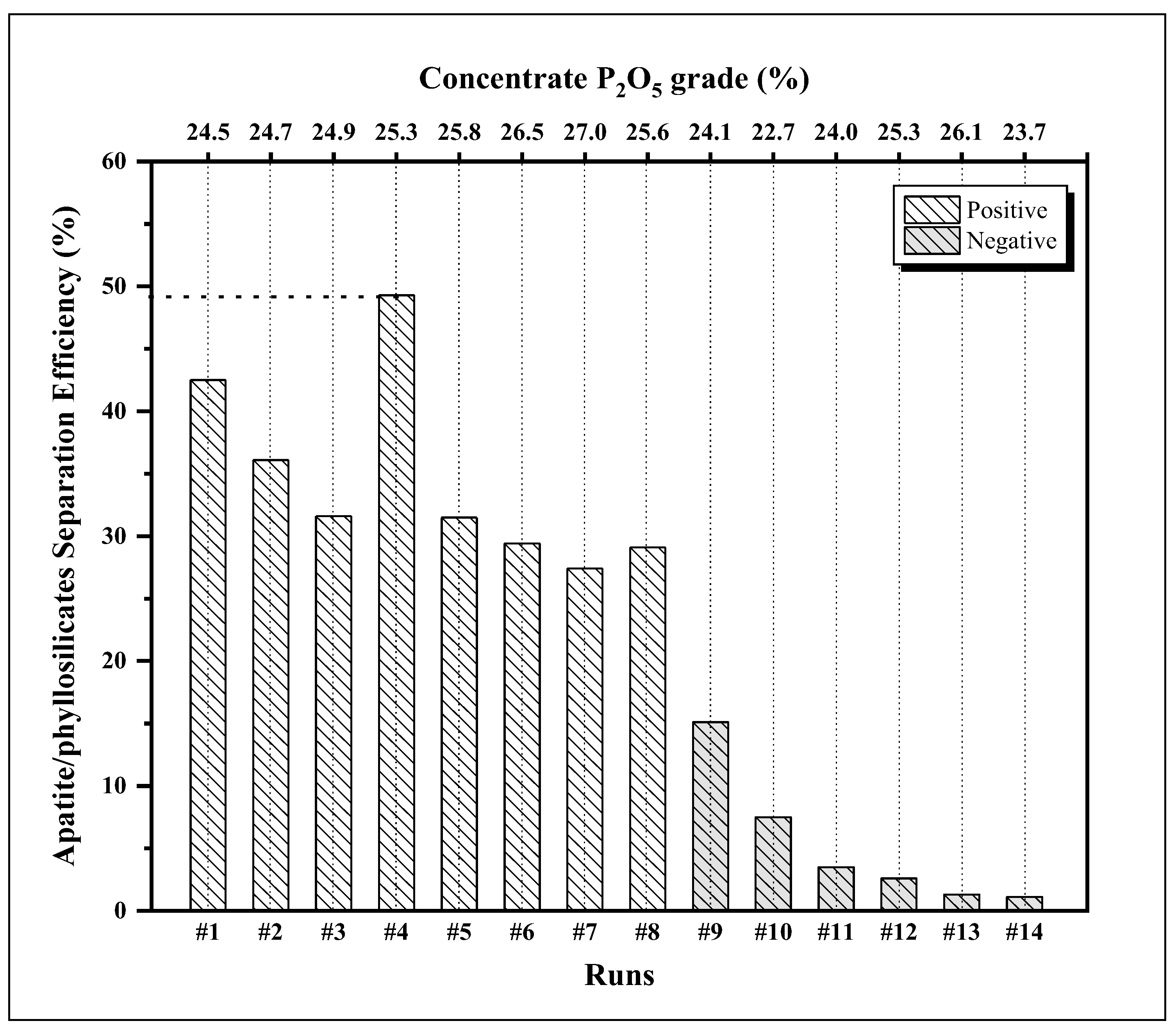

4.2.1. Rougher Stage

4.2.2. Cleaner Stage

4.2.3. Full Circuit Configuration Rougher/Cleaner

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBS | Triboelectrostatic Belt Separator |

| TES | Triboelectrostatic Separation |

| UMA | Unidade de Mineração de Angico |

| FSS | Free Settling Separators |

| TM | Testing Material |

| STET | ST Equipment & Technology LLC |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ICDD | International Center for Diffraction Data |

| ICSD | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database |

| EDS | Energy Dispersion X-ray Spectrometer |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| MLA | Mineral Liberation Analyzer |

References

- Notholt, A.J.G.; Sheldon, R.P.; Davidson, D.F. Phosphate deposits of the world - phosphate rock resources. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1969; 1, 565.

- Boujlel, H.; Daldoul, G.; Tlil, H.; Souissi, R.; Chebbi, N.; Fattah, N.; Souissi, F. The Beneficiation Processes of Low-Grade Sedimentary Phosphates of Tozeur-Nefta Deposit (Gafsa-Metlaoui Basin: South of Tunisia). Minerals 2019, 9, 2. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, L.S.; Assis, S.M.; Araujo, A.C.; Chaves, A.P. Process mineralogy studies for optimizing the flotation performance of two refractory phosphate ores. Minerals Engineering 1993, 6, 907-917. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, A.J.; Harbort, G.J.; Nelson, M.G. History of flotation. AusIMM, Carlton-Australia, 2010; 1, 348.

- Steiner, G.; Geissler, B.; Watson, I.; Mew, M.C. Efficiency developments in phosphate rock mining over the last three decades. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2015, 105, 235-245. [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, A.M. Physical and thermal treatment of phosphate ores – an overview. International Journal of Mineral Processing 2008, 85, 59-84. [CrossRef]

- Northey, S.A.; Mudd, G.M.; Wener, T.T.; Jowitt, S.M.; Haque, N.; Yellishety, M.; Weng, Z. The exposure of global base metal resources to water criticality, scarcity and climate change. Global Environmental Change 2017, 44, 109-124. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, J.D.; Gasiorowski, S.A.; Hrach, F.J.; Guicherd, H. Electrostatic beneficiation of phosphate ores: review of past work and discussion of an improvised separation system. Procedia Engineering 2015, 1, 1-11.

- Luciano, R. L.; Godoy, A. M. Geologia do complexo metacarbonatítico de Angico dos Dias. 2017. Geociências, vol. 1891, p. 301–314.

- Mata, C.E.D.; Sousa, P.L.R.; Pereira, C.A. Technological characterization of phosphate ore blended with the micacea and mafic typologies of the Angico dos Dias-BA alkaline-carbonatitic complex. Proceedings of the 28. ENTMME: Brazilian national meeting on ore treatment and extractive metallurgy. 2019, Belo Horizonte, pp. 4-8. Available at: http://www.entmme2019.entmme.org/trabalhos/084.pdf. Acesso em: 4 out. 2022.

- Mirkowska, M.; Kratzer, M.; Teichert, C.; Flachberger, H. Principal factors of contact charging of minerals for a successful triboelectrostatic separation process – a review. Berg und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte (BHM) 2016, 161, 359-382. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00501-016-0515-1.

- Leja, J. Surface chemistry of froth flotation. Plenum Press, New York, United States of America, 1982; 1, 758.

- Manouchehri, H.R.; Hanumantha Rao, K.; Forssberg, K.S.E. Review of electrical separation methods - Part 1: Fundamental aspects. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration 2000, 17, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gidaspow, D.; Wasan, D.T.; Electrostatic separation of powder mixture based on the work function of its constituents. Powder Technology 1993, 75, 79-87. [CrossRef]

- Turcaniova, L.; Soong, Y.; Lovas, M.; Mockcciakova, A.; Orinak, A.; Justinova, M.; Znamenackova, I.; Bezovska, M.; Marchant, S. The effect of microwave radiation on the triboelectrostatic separation of coal. Fuel 2004, 83, 2075-2079. [CrossRef]

- Horn, G.D.; Smith, D.T.; Grabbe, A. Contact electrification induced by monolayer modification of a surface and relation to acid-base interactions. Nature 1993, 366, 442-443. [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.A.; Hopkins, D.W. Mineral Processing Technology - An Introduction to the Practical Aspects of Ore Treatment and Mineral Recovery. Pergamon Press, Oxford, England, 2013; 646.

- Shen, Y.; Tao, D.; Zhang, L.; Shao, H.; Bai, X.; Yu, X. An experimental study of triboelectrostatic particle charging behavior and its associated fundamentals. Powder Technology 2023, 429, 118880. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, J.D.; Flynn, K.P.; Hrach, F.J. Expanding applications in dry triboelectric separation of minerals. Proceedings of the XXVII International Mineral Processing Congress – IMPC 2014, Santiago, Chile, 2014, 216-230. Available online: https://steqtech.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMPC-2014-Bittner-et-al-revised-140808.pdf.

- Kelly, E.G.; Spottiswood, D.J. The theory of electrostatic separations: a review — part I. Fundamentals. Minerals Engineering 1989, 2, 33-46. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yao, J.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X. Effect of moisture content on charging and triboelectrostatic separation of coal gasification fine ash. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 333, 125976. [CrossRef]

- Lindley, K.S.; Rowson, N.A. Feed preparation factors affecting the efficiency of the electrostatic separation. Magnetic and Electrical Separation 1997, 8, 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Galembeck, F.; Burgo, T.A.L.; Balestrin, B.S.; Gouveia, R.F.; Silva, C.A.; Galembeck, A. Friction, tribochemistry and triboelectricity: recent progress and perspectives. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances 2014, 4, 64280-64298. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, D.N. A basic triboelectric series for heavy minerals from inductive electrostatic separation behavior. The Journal of The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 2010, 110, 75-78. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2225-62532010000200005&lng=en&nrm=iso.

- Fraas, F. Electrostatic separation of granular materials, US Bureau of Mines 1962, B603, 26.

- Inculet, I. Electrostatic mineral separation, electrostatics and electrostatic application series. Research Studies Press, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1994, 215p.

- He, J.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Guo, C.; He, X.; Yang, B. Recent advances in the intensification of triboelectric separation and its application in resource recovery: A review. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification, vol. 185, 2023, p. 109308. [CrossRef]

- Souza Pinto, T.C.; Lima, O.A.; Leal Filho, L.S. Sphericity of apatite particles determined by gas permeability through packed beds. Minerals & Metallurgical Processes 2009, 26, 105-108. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, W.J. Minerals, metals and sustainability. CRC Press/Balkema, Leiden - The Netherlands, 2011, 419p.

- Küppers, H.; Knauer, H. Electrostatic free fall separator. United States Patent 4,797,201, 1989. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4797201A/en.

- Bittner, J.D.; Hrach, F.J.; Gasiorowskia, S.A.; Canellopoulus, L.A.; Guicherd, H. Triboelectric belt separator for beneficiation of fine minerals. Procedia Engineering 2014, 83, 122 – 129. [CrossRef]

- Chelgani, S.C.; Neisiani, A.S. Dry mineral processing. Springer Verlag, Berlim, Germany, 2022; 1, 156.

- Lindley, K.S.; Rowson, N.A. Feed preparation factors affecting the efficiency of the electrostatic separation. Magnetic and Electrical Separation 1997, 8, 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.; Li, T.X.; Hower, J.C.; Schaefer, J.L.; Stencel, J.M. Dry triboelectrostatic beneficiation of fly ash. Fuel, 1997, 76, 801-805.

- Hrach, F.; Flynn, K.; Miranda, P.J. Beneficiation of industrial minerals using a triboelectrostatic belt separator. Canadian Institute of Mining Metallurgy and Petroleum, 2016. Available online: https://onetunnel.org/documents/beneficiation-of-industrial-minerals-using-a-tribo-electric-belt-separator.

- Bada, S.O.; Falcon, L.M.; Falcon, R.M.S.; Bergmann, C.P. Feasibility study on triboelectrostatic concentration of <105μm phosphate ore. The Journal South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2012, 112, 2-6. Available online: https://scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2225-62532012000500004.

- Ciccu, R.; Ghiani, M. M.; Ferrara, G.: Selective tribocharging of particles for separation, Kona, 11, 1993, 5–16. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/kona/11/0/11_1993006/_pdf.

- Shockley, W. Currents to conductors induced by a moving point charge. Journal of Applied Physics, 1938, 9, 635-636. [CrossRef]

- Ramo, S. Currents induced by electron motion. Proceedings of the IRE, 1939, 27, 584-585. [CrossRef]

- Parker, K. R. Applied Electrostatic Precipitation. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, United Kingdom, 1997; 1, 521.

- Keller, G. V. Section 26: Electrical properties of rocks and minerals. Handbook of Physical Constants, Geological Society of America, 1966, 1, 553, . [CrossRef]

- ST Equipment & Technology LLC. M6c Manual. Installation and Operation Manual, 2020, 50p.

- Whitlock, David R. Separating Constituents of a Mixture of Particles. United States Patent 4,839,032, 1989. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4839032A/en.

- Whitlock, David R. Separating Constituents of a Mixture of Particles. United States Patent 4,874,507, 1989. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4874507A/en.

- Schulz, N.F. Separation efficiency. Transactions of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, 1970, 247, 81-87.

| Attributes | Froth flotation [10] | TES [11,12,13,14] |

|---|---|---|

| Separating medium | Water | Air |

| Differentiating property | Wettability by water | Fermi level/work function |

| Variable that controls the differentiating property | Contact angle | Density and sign of the acquired surface charge. |

| Surface modification previous to separation | Conditioning with chemical reagents (collectors, frothers, modifiers). | Contact/friction between mineral/mineral, mineral/polymers, mineral/walls of equipment, assisted or not by gas adsorption and radiation. |

| Modus operandi of the mineral separation | Hydrophobic particles collide and adhere to air bubbles and float; Hydrophilic particles do not adhere to air bubbles and sink |

Negatively charged particles move to the positively charged electrode, vice-versa. |

| Intensity and relative signs of the acquired charge | Triboelectrostatic Series | |

|---|---|---|

| Fraas [25] | Ferguson [24] | |

| ++++++++++++++ | Siderite | |

| ++++++++++++ | Olivine | |

| +++++++++++ | Andracite | |

| ++++++++++ | Apatite | Apatite |

| +++++++++ | Nepheline | Carbonates |

| ++++++++ | Magnesite | Monazite |

| +++++++ | Allanite | Titanomagnetite |

| +++++ | Staurolite | Ilmenite |

| ++++ | Beryl | Rutile |

| +++ | Grossularite | Leucoxene |

| ++ | Eudialyte | Magnetite/Hematite |

| + | Sphene | Spinel |

| - | Stilbite | Garnet |

| -- | Netafite | Staurolite |

| --- | Diopside | Altered Ilmenite |

| ---- | Cryolite | Goethite |

| ------ | Hornblende | Zircon |

| ------- | Monazite | Epidote |

| -------- | Chromite (Spinel) | Tremolite |

| --------- | Euxenite | Hydrous Silicates |

| ----------- | Scheelite | Aluminosilicates |

| ------------- | Microcline | Tourmaline |

| -------------- | Albite | Actinolite |

| --------------- | Quartz | Pyroxene |

| ----------------- | Rinodolite | Titanite |

| ------------------- | Actinolite | Feldspar |

| --------------------- | Hexagonite | Quartz |

| ----------------------- | Glauconite | |

| Forces | Cause | Effect | Contribution to the Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic | Magnitude, density, and sign of mineral surface charge prior to separation [26]; Magnitude and polarity of the static field generated by the electrodes positioned within the separators [26,27]. |

Attractive/repulsive forces between mineral particles and the equipment’s electrodes [26,27]. | Different position of apatite versus silicates in the triboelectric series maintained by either Ferguson [24] or Fraas [25]. |

| Gravity | Volume (size) and specific gravity () of the particles involved in the separation [26,27]. | Larger, heavier particles settle more quickly than smaller, lighter ones despite their buoyancy [26,27]. | Apatite particles (>3,000 kg/m3) are denser than many silicates ( < 2,800 kg/m3) [29]. |

| Drag | Particles’ shape and air temperature [26,27]. | Particles of lower sphericity factor () settle at a lower rate than rounded particles [26,27,28]. | Apatite particles settle as rough tetrahedrons (0.62 < Ψ < 0.64), whereas mica and clay particles show a platy-shaped habit (Ψ < 0.3) [28]. |

| Size Fractions | Mass (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| (mm) | Retained | Accumulated |

| +0.600 | 9.8 | 9.8 |

| -0.600 +0.500 | 10.3 | 20.1 |

| -0.500 +0.300 | 14.6 | 34.7 |

| -0.300 +0.210 | 17.3 | 52.0 |

| -0.210 +0.150 | 14.5 | 66.5 |

| -0.150 +0.074 | 16.7 | 83.2 |

| -0.074 | 16.8 | 100.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | - |

| Variables | Units | Typical range |

|---|---|---|

| Top electrode polarity | - | Positive/negative |

| Electrode voltage | 6 (*) | |

| Belt speed (S) | 4.6-19.8 | |

| Feed port | - | 1, 2 and 3 |

| Electrode gap (G) | 1.0-1.5 (x10-2) | |

| Mass feed rate of solids (F) | 0.13-1.25 |

| Secondary variables | Units | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Cross sectional area (A) | Based on electrode gap (G) | |

| Solids volumetric flowrate (Q) | Equation 2 | |

| Solids flux velocity (V) | Equation 3 | |

| Total flux velocity () | Equation 4 | |

| Residence time (T) | s | Equation 5 |

| Electric current on the electrodes (I) | mA | Current meter (*) |

| Feed Port | LE1 (m) | LE2 (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.58 | 1.53 |

| 2 | 3.05 | 3.05 |

| 3 | 1.53 | 4.58 |

| Runs | Duty | Independent variables | Secondary variables | |||||||||

| Feed Port | Top Electrode Polarity |

Feed Rate (kg/s) |

Gap (x10-2 m) |

Belt speed (m/s) |

Solids flowrate (x 10-4 m3/s) |

Total flux velocity (m/s) |

Time to reach E2 (s) (*) | Time to reach E1 (s) (**) | Top Electrode Current (mA) |

Bottom Electrode Current (mA) |

||

| #1 | Rougher | 1 | + | 0.56 | 1.52 | 18.3 | 1.9 | 18.4 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| #2 | Rougher | 1 | + | 0.56 | 1.32 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 12.4 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| #3 | Rougher | 1 | + | 0.47 | 1.21 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 6.3 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| #4 | Rougher | 2 | + | 0.44 | 1.25 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 8.6 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| #5 | Rougher | 2 | + | 0.44 | 1.27 | 6.1 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| #6 | Rougher | 2 | + | 0.39 | 1.14 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| #7 | Rougher | 3 | + | 0.39 | 1.14 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| #8 | Rougher | 3 | + | 0.44 | 1.14 | 5.2 | 1.5 | 5.4 | 0.85 | 0.28 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| #9 | Rougher | 1 | - | 0.56 | 1.08 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 12.5 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| #10 | Rougher | 1 | - | 0.56 | 1.13 | 9.1 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| #11 | Rougher | 1 | - | 0.56 | 1.20 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 0.24 | 0.72 | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| #12 | Rougher | 3 | - | 0.56 | 1.14 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 12.5 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 2.7 | 1.8 |

| #13 | Rougher | 3 | - | 0.56 | 1.08 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.71 | 0.24 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| #14 | Rougher | 3 | - | 0.56 | 1.14 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 0.72 | 0.24 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| #15 | Cleaner | 1 | + | 0.22 | 1.33 | 15.2 | 0.7 | 15.3 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| #16 | Cleaner | 1 | + | 0.56 | 1.27 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 12.4 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| #17 | Cleaner | 1 | + | 0.56 | 1.27 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| #18 | Cleaner | 2 | + | 0.56 | 1.27 | 12.2 | 1.9 | 12.4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| #19 | Cleaner | 2 | + | 0.31 | 1.27 | 9.1 | 1.0 | 9.3 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| #20 | Cleaner | 2 | + | 0.48 | 1.23 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 8.3 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Size Fractions (mm) |

Mass (%) | Content of analytes (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained | Accum. (*) | P2O5 | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | TiO2 | K2O | LOI | CaO:P2O5 | |

| +0.30 | 34.7 | 34.7 | 25.1 | 33.8 | 15.4 | 4.35 | 4.79 | 6.76 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 4.08 | 1.35 |

| -0.30+0.21 | 17.3 | 52.0 | 26.5 | 35.5 | 14.1 | 3.81 | 5.01 | 5.56 | 0.49 | 1.03 | 3.73 | 1.34 |

| -0.21+0.15 | 14.5 | 66.5 | 27.3 | 36.6 | 12.9 | 3.40 | 5.29 | 4.95 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 3.51 | 1.34 |

| -0.15+0.074 | 16.7 | 83.2 | 25.0 | 33.9 | 15.1 | 4.01 | 7.09 | 5.26 | 0.51 | 0.99 | 4.12 | 1.36 |

| -0.74 | 16.8 | 100.0 | 11.4 | 16.3 | 27.4 | 8.51 | 14.6 | 7.39 | 0.71 | 1.34 | 7.67 | 1.43 |

| Head (TM) | 100.0 | - | 22.9 | 31.0 | 17.4 | 4.99 | 6.81 | 6.50 | 0.48 | 1.16 | 4.62 | 1.35 |

| Total Calc. | 100.0 | - | 23.3 | 31.6 | 16.8 | 4.76 | 6.94 | 6.15 | 0.54 | 1.11 | 4.55 | 1.35 |

| Mineral species | Content (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fraction +0.600mm | Fraction -0.600 +0.074mm | |

| Apatite | 61 | 60 |

| Phyllosilicates | 32 | 30 |

| Feldspar | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Quartz | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Pyroxene + amphibole | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| Iron oxides (*) | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Carbonates (**) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Titanium oxides (***) | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Psilomelane | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Others | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Minerals | P2O5 | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | TiO2 | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apatite | 100 | 97 | ||||||

| Phyllosilicates | <1 | 1 | 78 | 85 | 68 | 95 | 56 | 86 |

| Feldspar | 9 | 13 | 13 | |||||

| Quartz | 7 | |||||||

| Other Silicates | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | <1 | ||

| Hematite/magnetite | <1 | 23 | <1 | 8 | ||||

| Goethite | 3 | |||||||

| Ilmenite | 3 | 31 | ||||||

| Psilomelane | ||||||||

| Others | <1 | <1 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <1 | 5 |

| Runs | Concentrate composition (%) | Recovery (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | Mass | P2O5 | MgO | |

| #1 | 24.5 | 11.0 | 6.18 | 3.78 | 3.75 | 81.7 | 88.1 | 45.6 |

| #2 | 24.7 | 11.4 | 6.20 | 3.86 | 4.16 | 80.2 | 86.9 | 50.8 |

| #3 | 24.9 | 10.9 | 7.33 | 3.84 | 3.51 | 76.9 | 83.2 | 51.6 |

| #4 | 25.3 | 10.9 | 5.85 | 3.52 | 3.37 | 75.3 | 85.1 | 35.8 |

| #5 | 25.8 | 11.2 | 5.82 | 3.60 | 3.33 | 68.7 | 77.1 | 45.8 |

| #6 | 26.5 | 10.6 | 5.61 | 3.41 | 4.22 | 59.3 | 68.9 | 39.5 |

| #7 | 27.0 | 11.0 | 5.58 | 3.70 | 3.83 | 46.9 | 55.3 | 27.9 |

| #8 | 25.6 | 11.0 | 5.92 | 3.54 | 3.56 | 65.1 | 75.4 | 46.3 |

| #9 | 24.1 | 9.8 | 8.08 | 3.89 | 3.14 | 48.0 | 53.8 | 38.7 |

| #10 | 22.7 | 10.5 | 9.41 | 4.13 | 4.04 | 41.3 | 44.3 | 36.8 |

| #11 | 24.0 | 10.1 | 8.85 | 3.76 | 3.36 | 12.9 | 14.1 | 10.6 |

| #12 | 25.3 | 9.0 | 7.62 | 3.08 | 2.42 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 2.6 |

| #13 | 26.1 | 10.4 | 6.70 | 3.76 | 3.67 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 3.1 |

| #14 | 23.7 | 10.4 | 8.61 | 4.11 | 3.66 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| Analytes | s | (*) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | 25.8 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| SiO2 | 11.4 | 0.5 | 4.8 |

| Al2O3 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 5.0 |

| MgO | 3.8 | 0.3 | 8.8 |

| Runs | Concentrate composition (%) | Recovery (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | Mass | P2O5 | MgO | |

| #15 | 29.0 | 8.62 | 4.62 | 2.96 | 2.84 | 66.5 | 81.4 | 55.3 |

| #16 | 27.9 | 10.16 | 5.43 | 3.28 | 2.42 | 67.3 | 76.7 | 41.8 |

| #17 | 27.7 | 10.34 | 5.19 | 3.14 | 3.06 | 62.3 | 71.0 | 50.2 |

| #18 | 28.9 | 9.78 | 4.81 | 2.99 | 2.89 | 72.8 | 87.6 | 59.6 |

| #19 | 27.2 | 9.51 | 5.10 | 3.14 | 2.99 | 63.5 | 71.6 | 55.1 |

| #20 | 31.9 | 8.89 | 3.94 | 2.29 | 1.64 | 20.8 | 33.2 | 12.9 |

| Item | Chemical composition (%) | Overall recovery (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MgO | Mass | P2O5 | MgO | |

| Feed | 22.9 | 17.4 | 6.81 | 4.99 | 6.50 | - | - | - |

| Run#4 (*) | 25.3 | 10.9 | 5.85 | 3.52 | 3.37 | 75.3 | 85.1 | 35.8 |

| Run#15 (*) | 29.0 | 8.62 | 4.62 | 2.96 | 2.84 | 66.5 | 81.4 | 55.3 |

| Run#18 (*) | 28.9 | 9.78 | 4.81 | 2.99 | 2.89 | 72.8 | 87.6 | 59.6 |

| Total Option 1(**) | 29.0 | 8.62 | 4.62 | 2.96 | 2.84 | 50.0 | 69.3 | 19.8 |

| Total Option 2 (***) | 28.9 | 9.78 | 4.81 | 2.99 | 2.89 | 54.8 | 74.5 | 21.3 |

| Fosnor (****) | 29.5 | 9.51 | 4.94 | 3.13 | 1.98 | 36.3 | 55.7 | 27.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).