Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

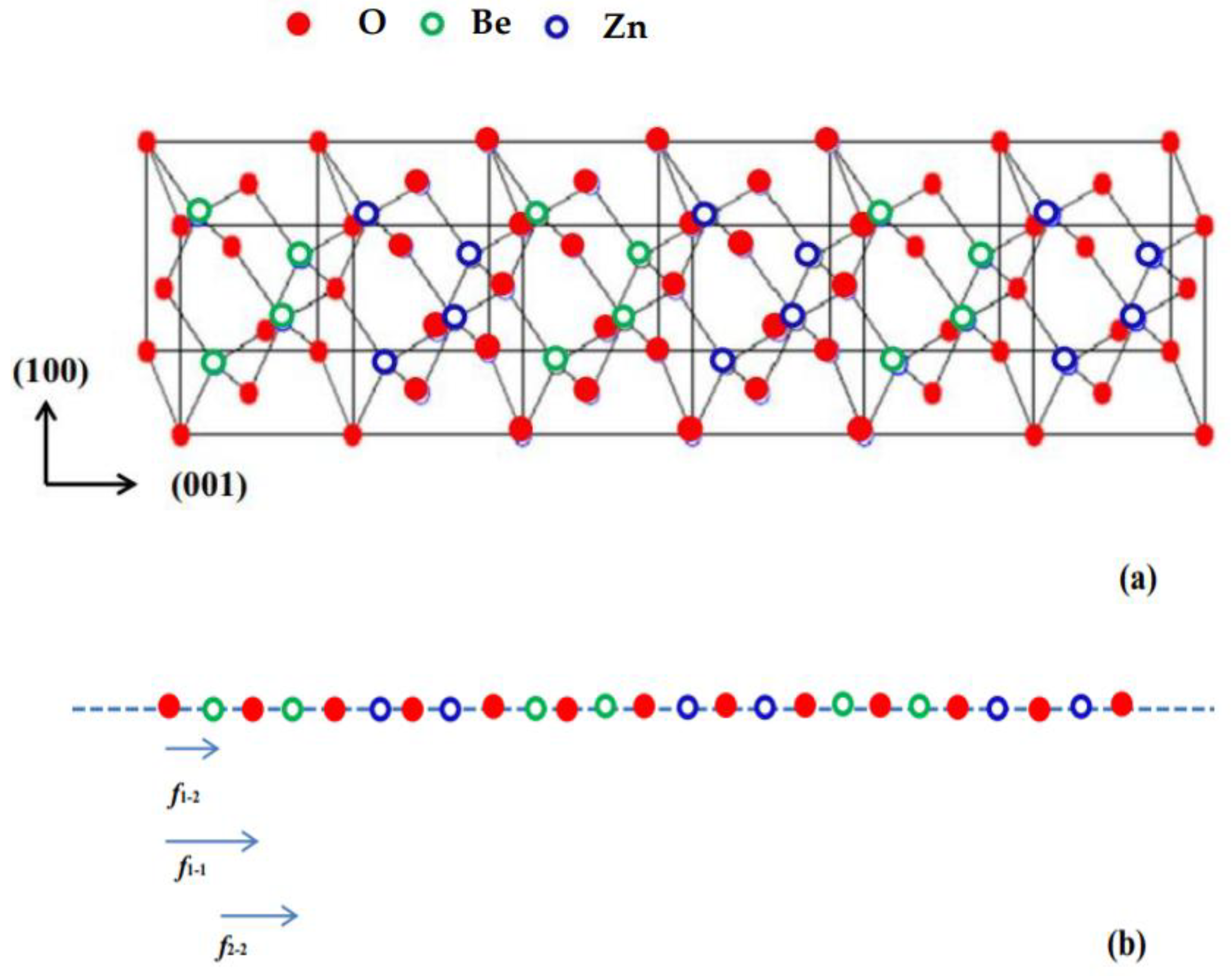

2.2. Phonons in zb (BeO)m/(ZnO)n SLs

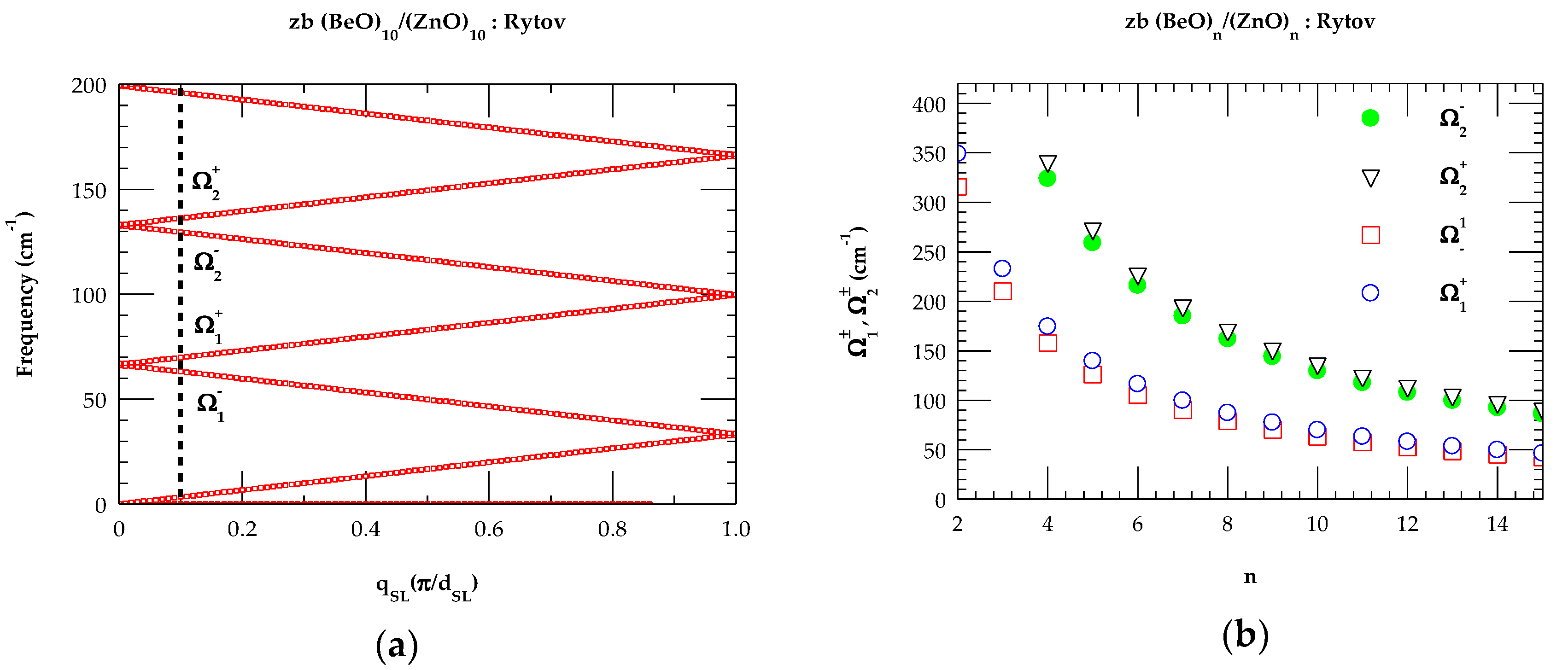

2.2.1. Rytov’s Model

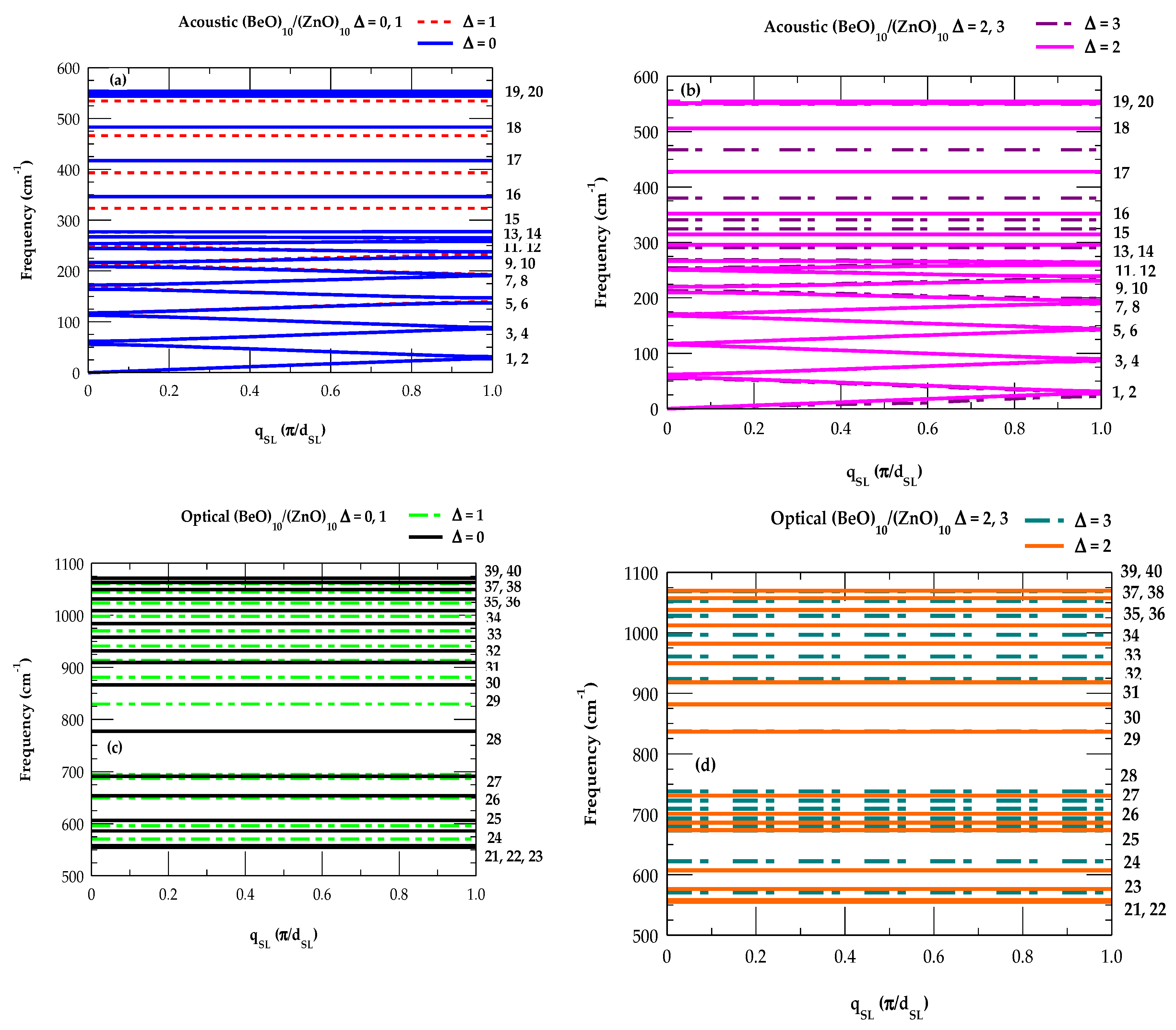

2.2.2. Phonon Dispersions in Superlattices

2.2.3. Raman Intensity Profiles in Superlattices

3. Numerical Simulations, Results and Discussions

3.1. Folded Acoustic Modes Elastic Continuum Model

3.2. Modified Linear Chain Model

3.2.1. Phonon Dispersions

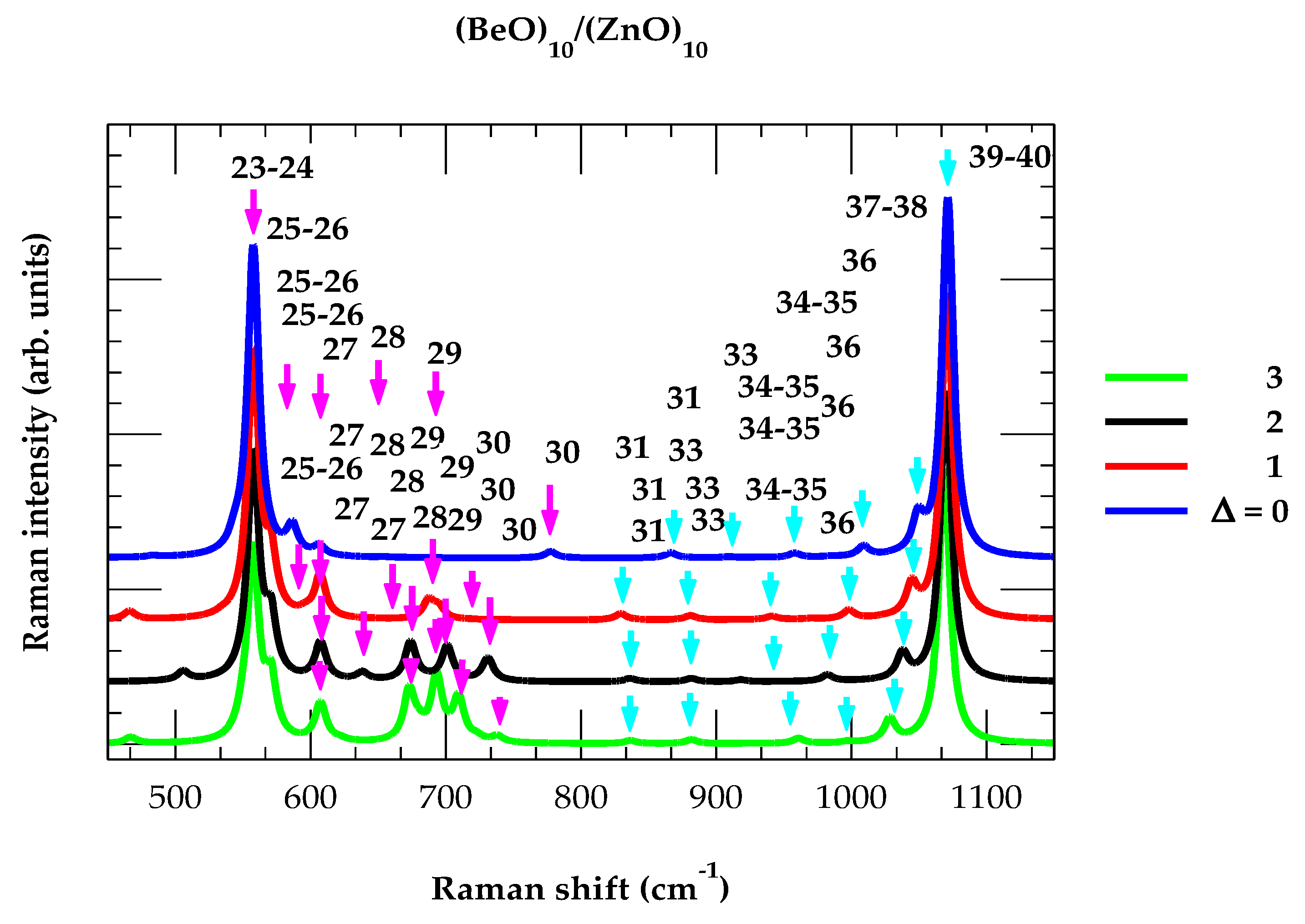

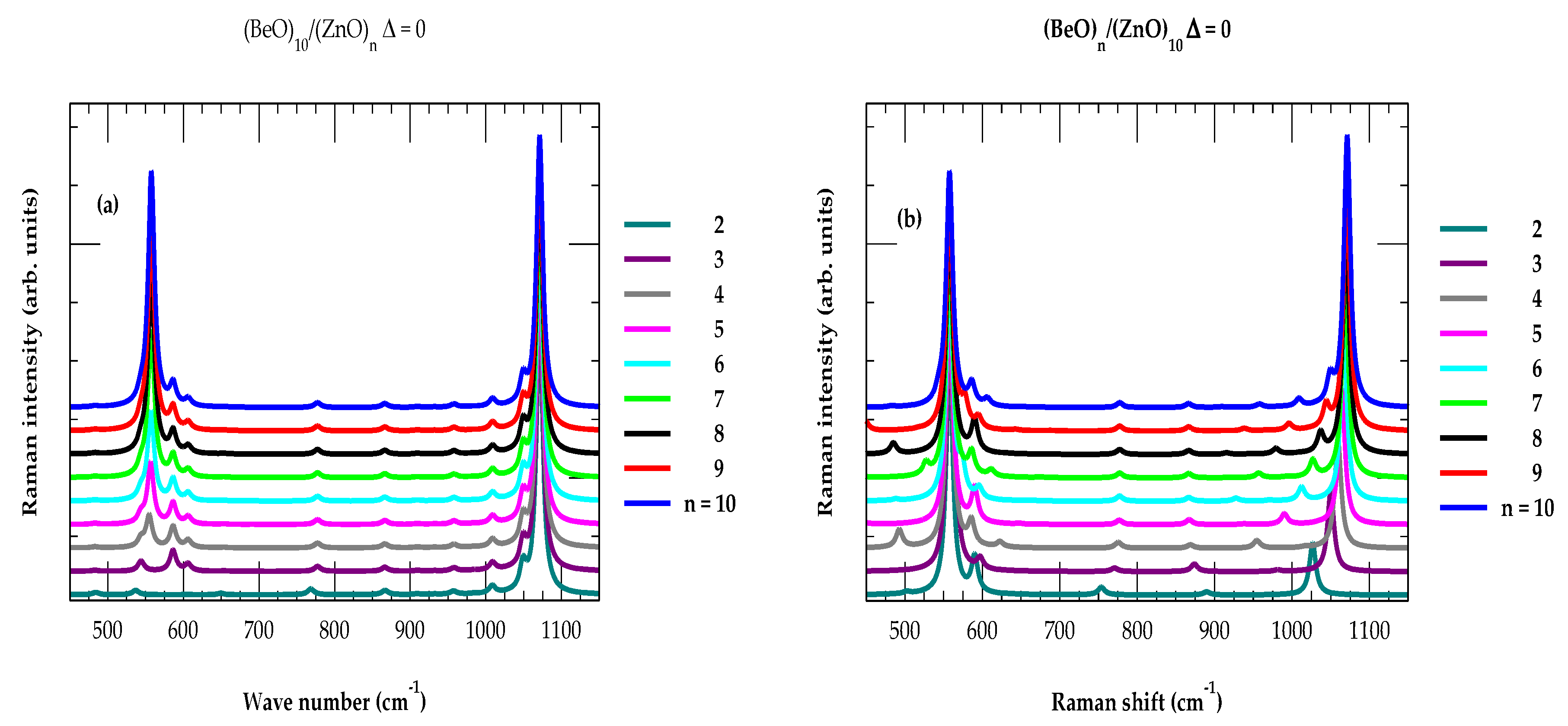

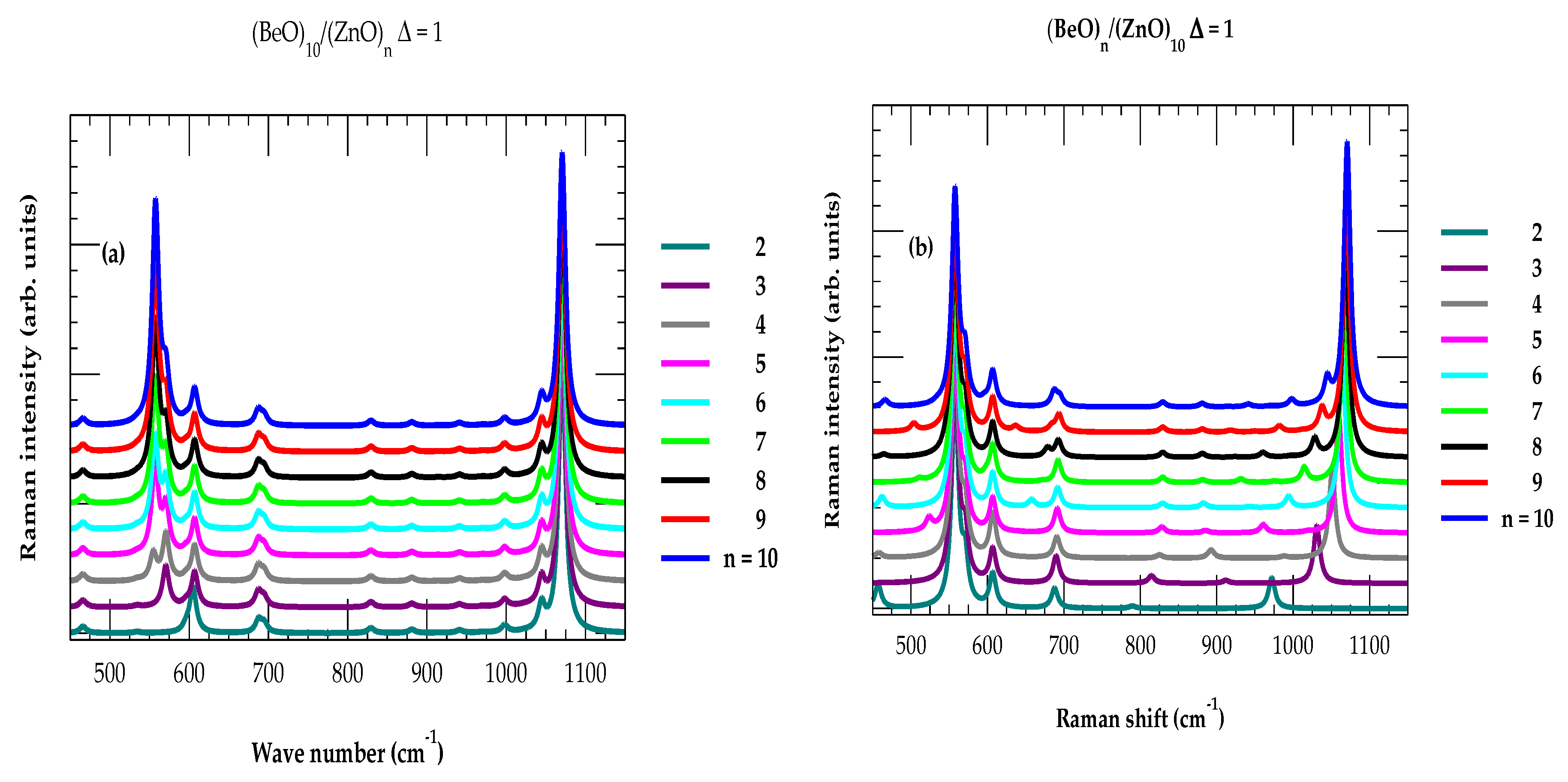

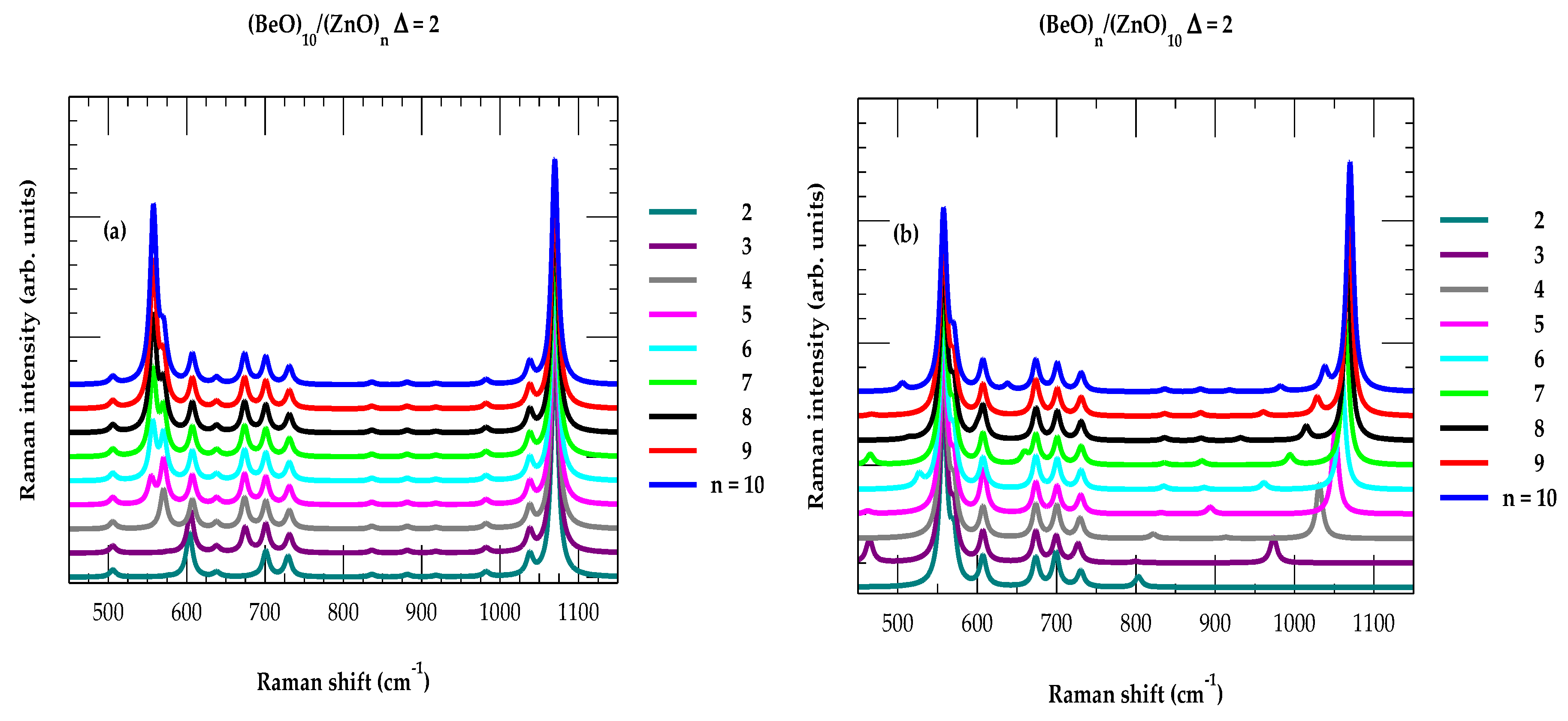

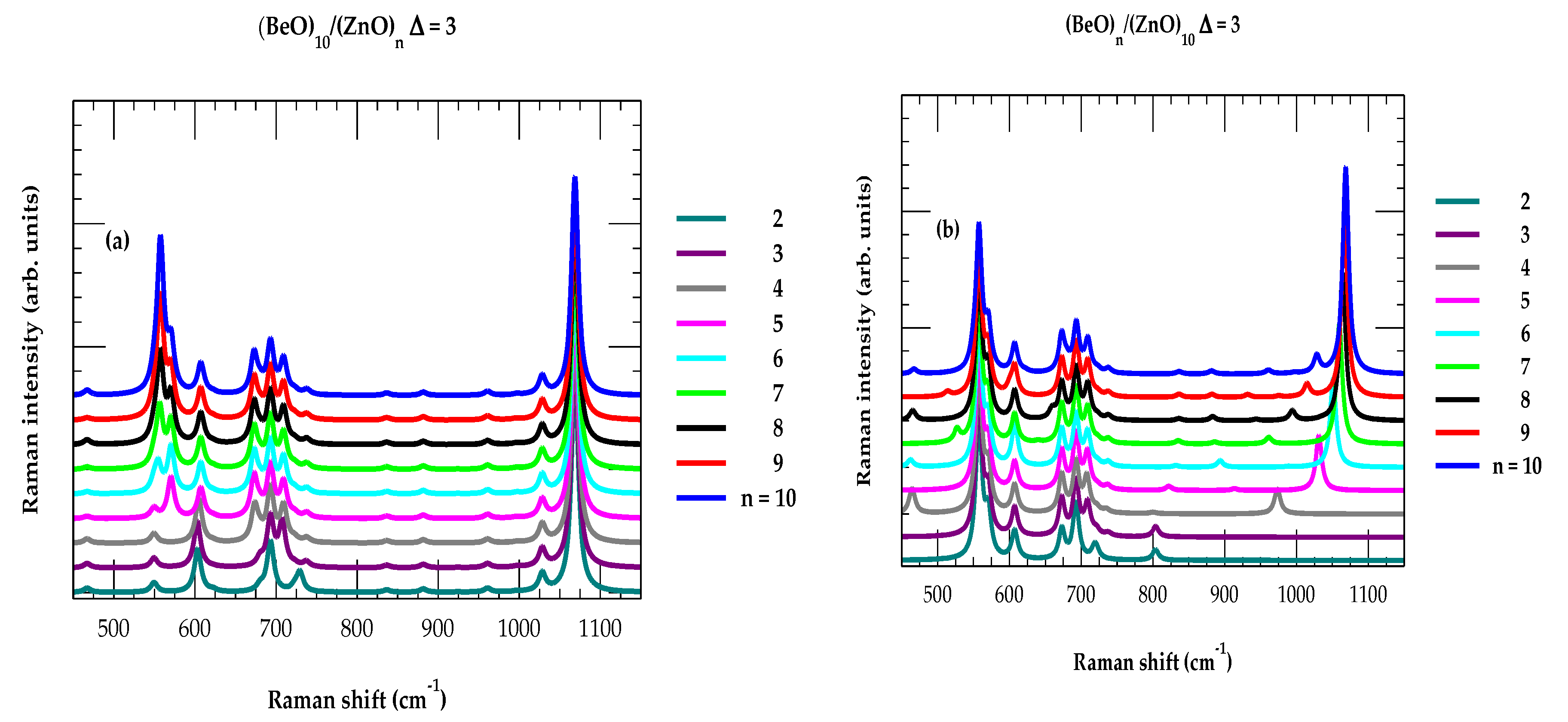

3.2.3. Raman Scattering

- (a)

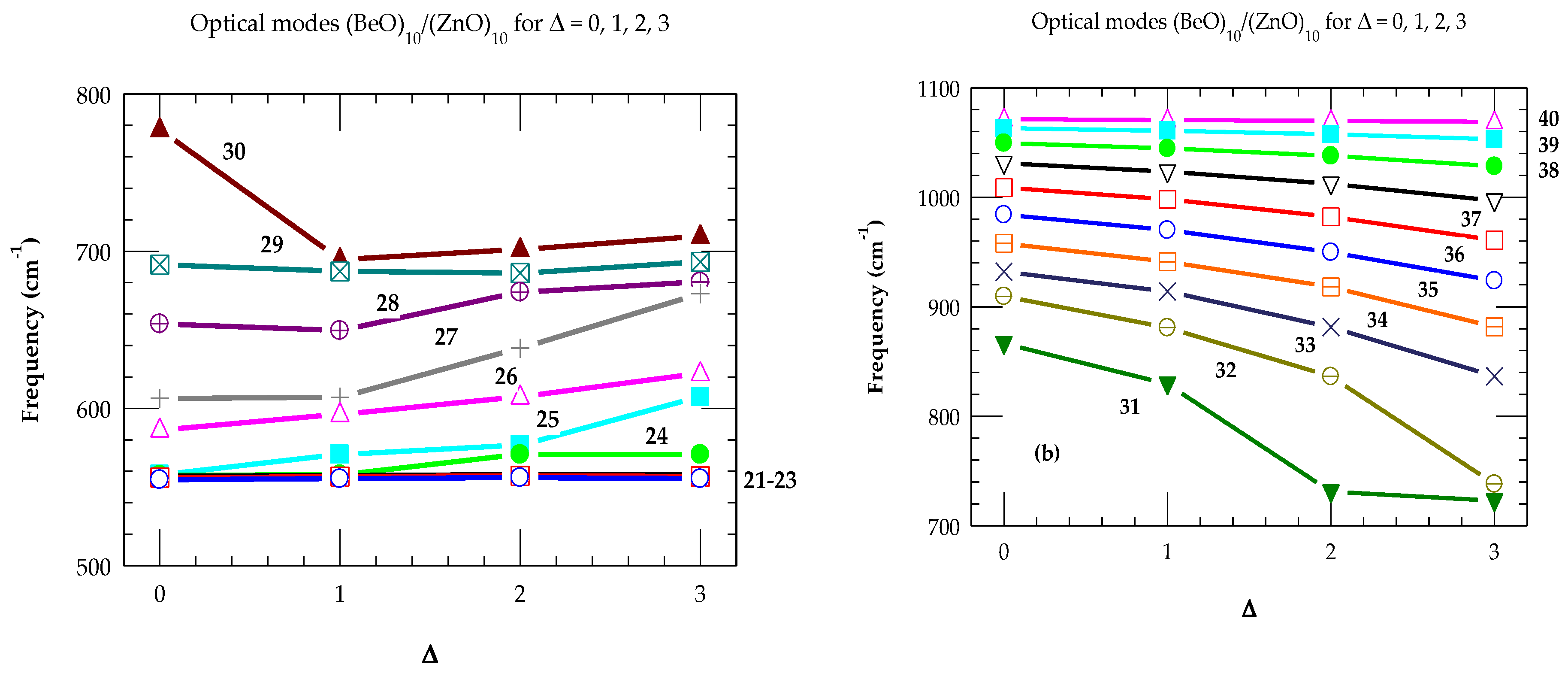

- Impact of Interfacial Widths

- (b)

- Impact of Number of Monolayers

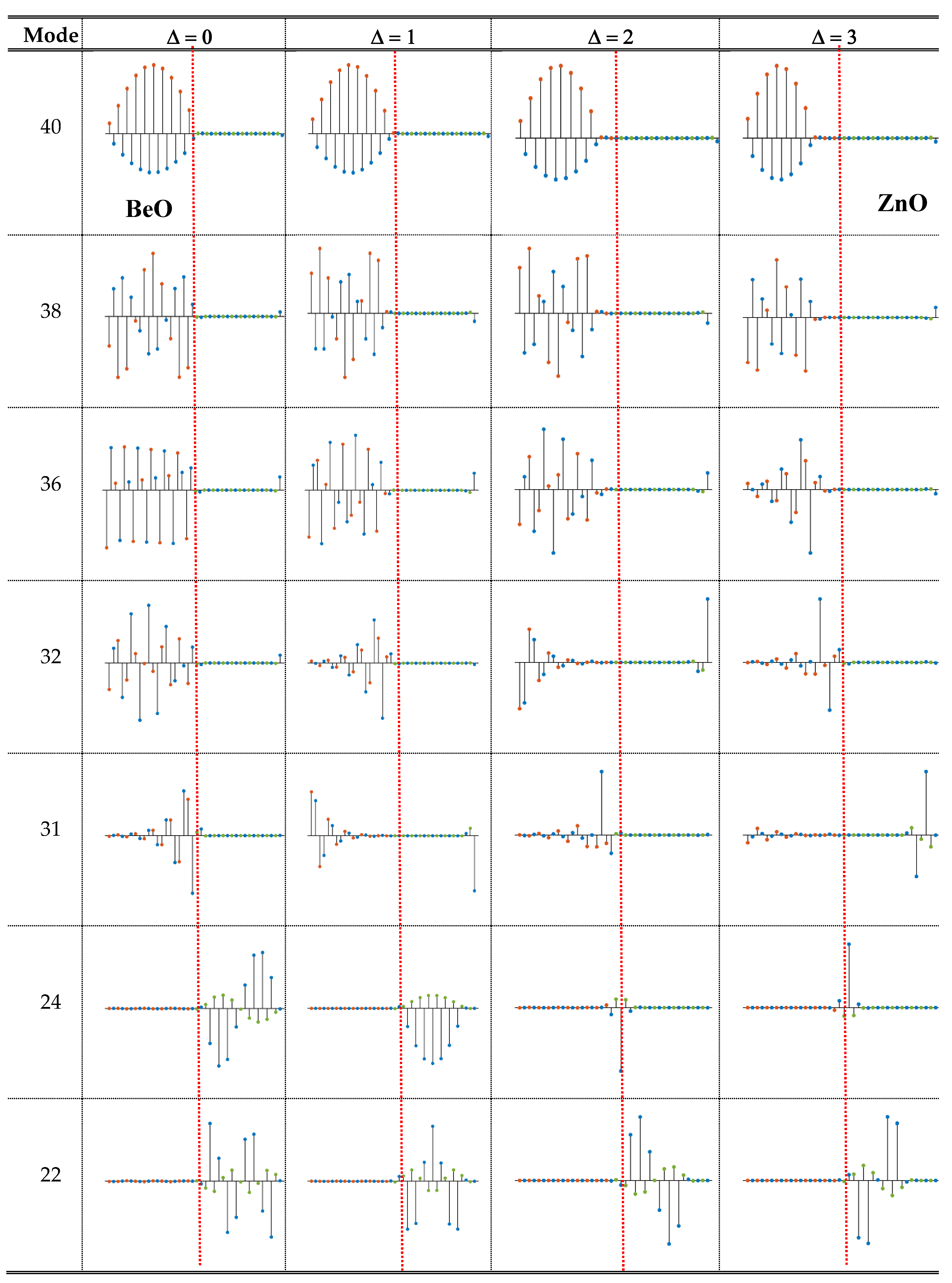

3.3. Atomic Displacements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data and Code Availability

Ethical approval

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

- Sharma, D.K.; Shukla, S.; Sharma, K. K.; Kumar, V., A review on ZnO: Fundamental properties and applications, Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 49, 3028–3035.

- Pushpalatha, C.; Suresh, J.; Gayathri, V.S.; Sowmya, S.V.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Albar, N. H. M.; Patil, S., Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review on Its Applications in Dentistry, Nanoparticles: A Review on Its Applications in Dentistry, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10: 917990. [CrossRef]

- Borysiewicz, M. A., ZnO as a Functional Material, a Review, Crystals 2019, 9, 505;. [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.; Norton, D.; Ip, K.; Heo, Y.; Steiner, T. Recentprogress in processing and properties of ZnO. Superlattices Microstruct. 2003, 34, 3–32.

- Schmidt-Mende, L.; MacManus-Driscoll, J. L. ZnO nanostructures, defects, and devices. Mater. Today 2007, 10, 40−48.

- Özgür, Ü.; Alivov, Ya. I.; Liu, C.; Teke, A.; Reshchikov, M. A.; Doğan, S.; Avrutin, V.; Cho, S.-J.; Morkoç, H., A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices, J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 041301.

- Yum, J.H.; Akyol, T.; Ferrer, D.A.; Lee, J.C.; Banerjee, S.K.; Lei, M.; Downer, M.; Hudnall, T.W.; Bielawski, C.W.; Bersuker, G. Comparison of the Self-Cleaning Effects and Electrical Characteristics of BeO and Al2O3 Deposited as an Interface Passivation Layer on GaAs MOS Devices. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2011, 29, 061501.

- Subramanian, M.A.; Shannon, R.D.; Chai, B.H.T.; Abraham, M.M.; Wintersgill, M.C. Dielectric Constants of BeO, MgO, and CaOUsing the Two-Terminal Method. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1989, 16, 741–746.

- Sashin, V.A.; Bolorizadeh, M.A.; Kheifets, A.S.; Ford, M.J. Electronic Band Structure of Beryllium Oxide. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2003, 15, 3567.

- Yim, K.; Yong, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Nahm, H.-H.; Yoo, J.; Lee, C.; Hwang, C.S.; Han, S. Novel High-κ Dielectrics for Next-Generation Electronic Devices Screened by Automated Ab Initio Calculations. NPG Asia Mater. 2015, 7, e190.

- Yum, J.H.; Akyol, T.; Lei, M.; Ferrer, D.A.; Hudnall, T.W.; Downer, M.; Bielawski, C.W.; Bersuker, G.; Lee, J.C.; Banerjee, S.K. Electrical and Physical Characteristics for Crystalline Atomic layer Deposited Beryllium Oxide Thin Film on Si and GaAs Substrates. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 3091–3095.

- Chandramouli, D.; Revankar, S.T. Development of Thermal Models and Analysis of UO2-BeO Fuel during a Loss of Coolant Accident. Int. J. Nucl. Energy 2014, 2014, 751070.

- Garcia, C.B.; Brito, R.A.; Ortega, L.H.; Malone, J.P.; McDeavitt, S.M. Manufacture of a UO2-Based Nuclear Fuel with Improved Thermal Conductivity with the Addition of BeO. Metall. Mater. Trans. E 2017, 4, 70–76.

- Camarano, D.M.; Mansur, F.A.; Santos, A.M.M.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Santos, A. Thermal Conductivity of UO2–BeO–Gd2O3 Nuclear Fuel Pellets. Int. J. Thermophys. 2019, 40, 110.

- Chen, S.; Yuan, C. Neutronic Study of UO2-BeO Fuel with Various Claddings. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 22, 100728.

- Nicolay, S.; Fay, S.; Ballif, C. Growth Model of MOCVD Polycrystalline ZnO. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 4957.

- Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Shi, Z.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B. Nucleation and growth of ZnO films on Si substrates by LP-MOCVD. Superlattices Microstruct. 2014, 71, 23–29.

- Youdou, Z.; Shulin, G.; Jiandong, Y.; Wei, L.; Shunmin, Z.; Feng, Q.; Liqun, H.; Rang, Z.; Yi, S. MOCVD Growth and Properties of ZnO and Znl-x,MgxO Films. In Proceedings of the Sixth Chinese Optoelectronics Symposium, Hong Kong, China, 14 September 2003.

- Kadhim, G.A. Study of the Structural and Optical Traits of In:ZnO Thin Films Via Spray Pyrolysis Strategy: Influence of laser Radiation Change in Different Periods. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2922, 240006.

- Wei, X.H.; Li, Y.R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.B.; Ji, H. Epitaxial properties of ZnO thin films on SrTiO3 substrates grown by laser molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 151918.

- Opel, M.; Geprags, S.; Althammer, M.; Brenninger, T.; Gross, R. Laser molecular beam epitaxy of ZnO thin films and heterostructures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 034002.

- Chauveau, J.-M.; Morhain, C.; Teisseire, M.; Laugt, M.; Deparis, C.; Zuniga-Perez, J.; Vinter, B. (Zn, Mg)O/ZnO-based heterostructures grown by molecular beam epitaxy on sapphire: Polar vs. non-polar. Microelectron. J. 2009, 40, 512–516.

- Peltier, T.; Takahashi, R.; Lippmaa, M. Pulsed laser deposition of epitaxial BeO thin films on sapphire and SrTiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 231608.

- Triboulet, R.; Perrière, J. Epitaxial growth of ZnO films. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 2003, 47, 65–138.

- Yıldırım, Ö.A.; Durucan, C. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles elaborated by microemulsion method. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 506, 944–949.

- Mao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhu, L.; Liao, G. Solvothermal synthesis and photocatalytic properties of ZnO micro/ nanostructures. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 1724–1729.

- Araujo, E.A., Jr.; Nobre, F.X.; Sousa, G.d.S.; Cavalcante, L.S.; Santos, M.R.M.C.; Souza, F.L.; de Matos, J.M.E. Synthesis, growth mechanism, optical properties and catalytic activity of ZnO microcrystals obtained via hydrothermal processing. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24263–24281.

- Brown, R.A.; Evans, J.E.; Smith, N.A.; Tarat, A.; Jones, D.R.; Barnett, C.J.; Maffeis, T.G.G. The effect of metal layers on the morphology and optical properties of hydrothermally grown zinc oxide nanowires. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 4908–4913.

- Kisielowski, C.; Weber, Z.L.; Nakamura, S. Atomic scale indium distribution in a GaN/In0.43Ga0.57N/Al0.1Ga0.9N quantum well structure. Jpn. J. Phys. 1997, 36, 6932.

- Behr, D.; Niebuhr, R.; Wagner, J.; Bachem, K.-H.; Kaufmann, U. Resonant Raman scattering in GaN/(AlGa)N single quantum wells, Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 363–365.

- Bogusławski, P.; Bernholc, J. Segregation effects at vacancies in AlxGa1-xN and SixGe1-x alloys, Phys. Rev. B 1987, 59, 1567-1570.

- Davydov, V.; Roginskii, E.; Kitaev, Y.; Smirnov, A.; Eliseyev, I.; Nechaev, D.; Jmerik, V.; Smirnov, M. Phonons in Short-Period GaN/AlN Superlattices: Group-Theoretical Analysis, Ab initio Calculations, and Raman Spectra. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 286.

- Davydov, V.Y.; Roginskii, E.M.; Kitaev, Y.E.; Smirnov, A.N.; Eliseyev, I.A.; Rodin, S.N.; Zavarin, E.E.; Lundin, W.V.; Nechaev, D.V.; Jmerik, V.N.; et al. Analysis of the sharpness of interfaces in short-period GaN/AlN superlattices using Raman spectroscopy data. In Proceedings of the International Conference PhysicA.SPb/2021, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 18–22 October 2021; Volume 2103, p. 012147.

- Jusserand, B.; Cardona, M. Light Scattering in Solids V. In Topics in Applied Physics; Cardona, M., Güntherodt, G., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; Volume 66, p. 49.

- Ruf, T. Phonon Raman Scattering in Semiconductors, Quantum Wells and Superlattices; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998.

- Dharma-Wardana, M.W.C.; Aers, G.C.; Lockwood, D.J.; Baribeau, J.M. Interpretation of Raman spectra of Ge/Si ultrathin superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 5319.

- Kim, Min-gab, Spectroscopic imaging ellipsometry for two-dimensional thin film thickness measurement using a digital light processing projector, Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 095016.

- Barker, A, S. Jr; Sievers, A. J., Optical studies of the vibrational properties of disordered solids, Rev. Mod. Phys. 1975, 47 Suppl. 1, 2. [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.V.; Gant, T.A.; Levi, D.; Zhang, S.-L. Raman Studies of Phonons in GaAs/AlGaAs Superlattices. Laser Opt. Condens. Matter 1988, 119-126.

- Silva, M.A.A.; Ribeiro, E.; Schulz, P.A.; Cerdeira, F.; Bean, J.C. Linear-chain-model interpretation of resonant Raman scattering in GenSim microstructures. Phs. Rev. B 1996, 53, 15871.

- Talwar, Devki, N. Computational phonon dispersions structural and thermo-dynamical characteristics of novel C-based XC (X = Si, Ge and Sn) materials. Next Mater. 2024, 4, 100198.

- Talwar, Devki, N. Composition dependent phonon and thermo-dynamical characteristics of C-based XxY1-xC (X, Y≡Si, Ge, Sn) alloys. Inorg. Inorg. 2024, 12, 100. [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N.; Semone, S.; Becla, P. Strain dependent effects on confinement of folded acoustic and optical phonons in shortperiod (XC)m/(YC)n with X,Y (≡Si, Ge, Sn) superlattices. Materials 2024, 17, 3082. [CrossRef]

- Talwar, Devki N.; Lenze, Benjamin A.; Czak, Jason E. Bensaoula, Abdelhak, Phonon modes and Raman intensity profiles in zinc-blende BN/GaN superlattices, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 015305.

- Bezerra, E.F.; Filho, A.G.S.; Freire, V.N.; Filho, J.M.; Lemos, V. Strong interface localization of phonons in non-abrupt InN/GaN superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 201306.

- Gaisler, V.A.; Govorov, A.; Kurochkina, T.V.; Moshegov, N.T.; Stenin, S.I.; Toropov, A.I.; Shebanin, A.P. Phonon spectrum of GaAs-lnAs superlattices. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1990, 98, 1081–109.

- Pokatilov, E.P.; Beril, S.I. Electron–Phonon Interaction in Periodic Two-Layer Structure, Phys. Status Solidi b 118 1983,118, 567–573.

- Camley, R.E.; Mills, D.L. Collective excitations of semi-infinite superlattice structures: Surface plasmons, bulk plasmons, and the electron-energy-loss spectrum Phys. Rev. B 1984, 29, 1695.

- Nakayama, M.; Ishida, M.; Sano, N. Raman scattering by interface-phonon polaritons in a GaAs/AlAs heterostructure Phys. Rev. B 1988, 38, 6348.

- Paudel, Tula R.; Lambrecht, Walter R. L. Computational study of phonon modes in short-period AlN/GaN superlattices, Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 104202.

- 2017; 7, 51. Kothari, Kartik; Maldovan, Martin, Phonon Surface Scattering and Thermal Energy Distribution in Superlattices, Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 5625 (2017).

- Hoglund1, Eric R.; Bao, De-Liang; O’Hara, Andrew; Makarem, Sara; Piontkowski, Zachary T.; Matson, Joseph R.; Yadav, Ajay K.; Haislmaier, Ryan C.; Engel-Herbert, Roman; Ihlefeld, Jon F.; Ravichandran, Jayakanth; Ramesh, Ramamoorthy; Caldwell, Joshua D.; Beechem, Thomas E.; Tomko, John A.; Hachtel, Jordan A.; Pantelides, Sokrates T.; Hopkins1, Patrick E.; Howe, James M., Emergent interface vibrational structure of oxide superlattices, Nature 2022, 601, 556-563.

- Rytov, S. M. Electromagnetic properties of laminated medium, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 1955, 29, 605–616.

- Van Velson, Nathan; Zobeiri, Hamidreza; Wang, Xinwei, Thickness-Dependent Raman Scattering from Thin-Film Systems, J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 2995−3004.

- Zhu, B.; Chao, K.A. Phonon modes and Raman scattering in GaAs/Ga1-xAlxAs. Phys. Rev. B 1987, 36, 4906.

- Talwar; Devki N., Becla, Piotr, Composition-Dependent Structural, Phonon, and Thermodynamical Characteristics of Zinc-Blende BeZnO, Materials 2025, 18, 3101 . [CrossRef]

- Talwar; Devki N., Becla, Piotr, Atypical Pressure Dependent Structural Phonon and Thermodynamic Characteristics of Zinc Blende BeO, Materials 2025, 18, 3671 . [CrossRef]

- Talwar; Devki N., Becla, Piotr, Systematic Simulations of Structural Stability, Phonon Dispersions, and Thermal Expansion in Zinc-Blende ZnO, Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 308 . [CrossRef]

- Talwar; Devki N., Becla, Piotr, Microhardness, Young’s and Shear Modulus in Tetrahedrally Bonded Novel II-Oxides and III-Nitrides, Materials 2025, 18, 494 . [CrossRef]

- Talwar; Devki N., Becla, Piotr, Impact of Acoustic and Optical Phonons on the Anisotropic Heat Conduction in Novel C-Based Superlattices, Materials 2024, 17, 4894. [CrossRef]

- Talwar; Devki N., Haraldsen, Jason T. Simulations of Infrared Reflectivity and Transmission Phonon Spectra for Undoped and Doped GeC/Si (001), Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1439. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Farias, G.A.; Freire, V.N. Interface related exciton-energy blueshift in GaN/AlxGa1-xN zinc-blende and wurtzite single quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 5705.

- Talwar, D.N.; Feng, Z.C.; Liu, C.W.; Tin, C.-C. Influence of surface roughness and interfacial layer on the infrared spectra of V-CVD grown 3C-SiC/Si (1 0 0) epilayers. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 115019.

- Esaki, L.; Tsu R., Nonlinear optical response of conduction electrons in a superlattice, Appl. Phys. Lett. 1971, 19, 246.

- Esaki, L., A bird’s-eye view on the evolution of semiconductor superlattices and quantum wells, IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics 1986, 22, 1611 – 1624, DOI: 10.1109/JQE.1986.1073162.

- Nizzoli, Fabrizio; Rieder, Karl-Heinz; Willis, Roy F. Editors: Dynamical Phenomena at Surfaces, Interfaces and Superlattices Proceedings of an International Summer School at the Ettore Majorana Centre, Erice, Italy, July 1–13, 1984 Springer Series in Surface Sciences (SSSUR, volume 3, 1984-85).

| Parameters | zb BeO | zb ZnO |

| 3.80 | 4.50 | |

| (1011dyn cm-2) | 34.2 | 19.19 |

| (g cm-3) | 3.0287 | 5.9339 |

| (105 cm s-1) | 10.626 | 5.6883 |

| (cm-1) | 1071 | 558 |

| (cm-1) | 899 | 551 |

| (cm-1) | 707 | 269 |

| N | ω0 | Δω10 | Δω20 | Δω30 |

| 21 | 554.7 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| 25 | 586.4 | 9.8 | 21.0 | 35.9 |

| 26 | 606.4 | 0.7 | 31.9 | 66.6 |

| 27 | 653.8 | -4.3 | 20.2 | 26.6 |

| 29 | 691.5 | -4.3 | -5.4 | 1.7 |

| 30 | 777.4 | -79.7 | -76.3 | -69.0 |

| 31 | 866.4 | -37.0 | -135.3 | -143.5 |

| 32 | 909.5 | -28.5 | -73.1 | -171.4 |

| 33 | 932 | -18.1 | -50.6 | -95.5 |

| 34 | 957.9 | -16.8 | -39.8 | -76.3 |

| 35 | 984.1 | -14.0 | -34.3 | -60.3 |

| 36 | 1008.9 | -10.8 | -26.7 | -48.1 |

| 37 | 1031.1 | -7.7 | -18.9 | -34.3 |

| 38 | 1049.4 | -4.8 | -11.6 | -21.0 |

| 40 | 1071.2 | -0.6 | -1.4 | -2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).