Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

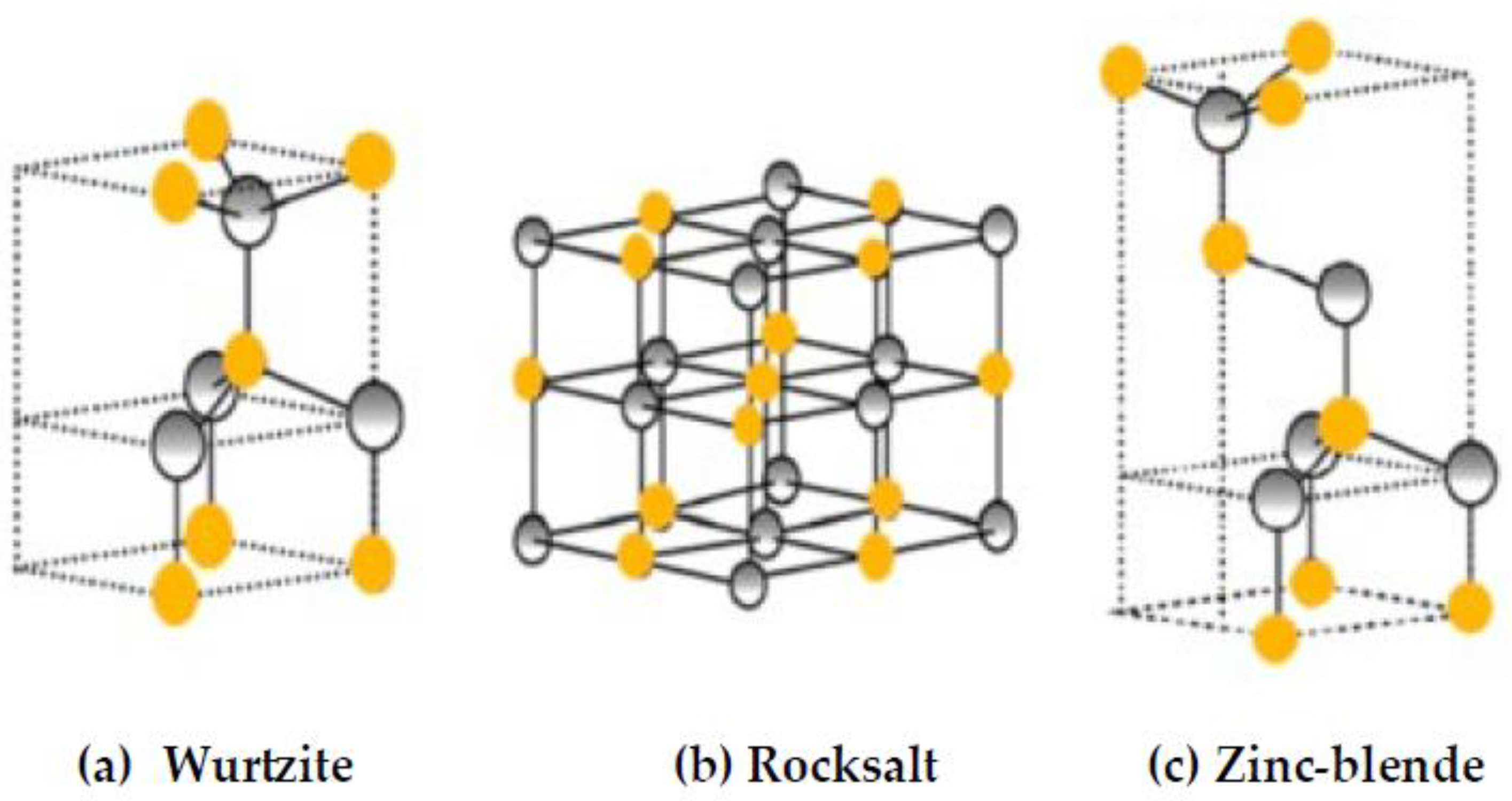

2.1. Structural Properties

2.2. Computational Methodology of Lattice Dynamics

2.2.1. Rigid-ion Model

2.2.2. The Quasi Harmonic Approximation

2.2.3. Interatomic Force Constants of zb BeO at P = 0 GPa

2.3. Thermodynamical properties

2.3.1. Thermodynamical properties

3. Numerical Computations, Results and Discussions

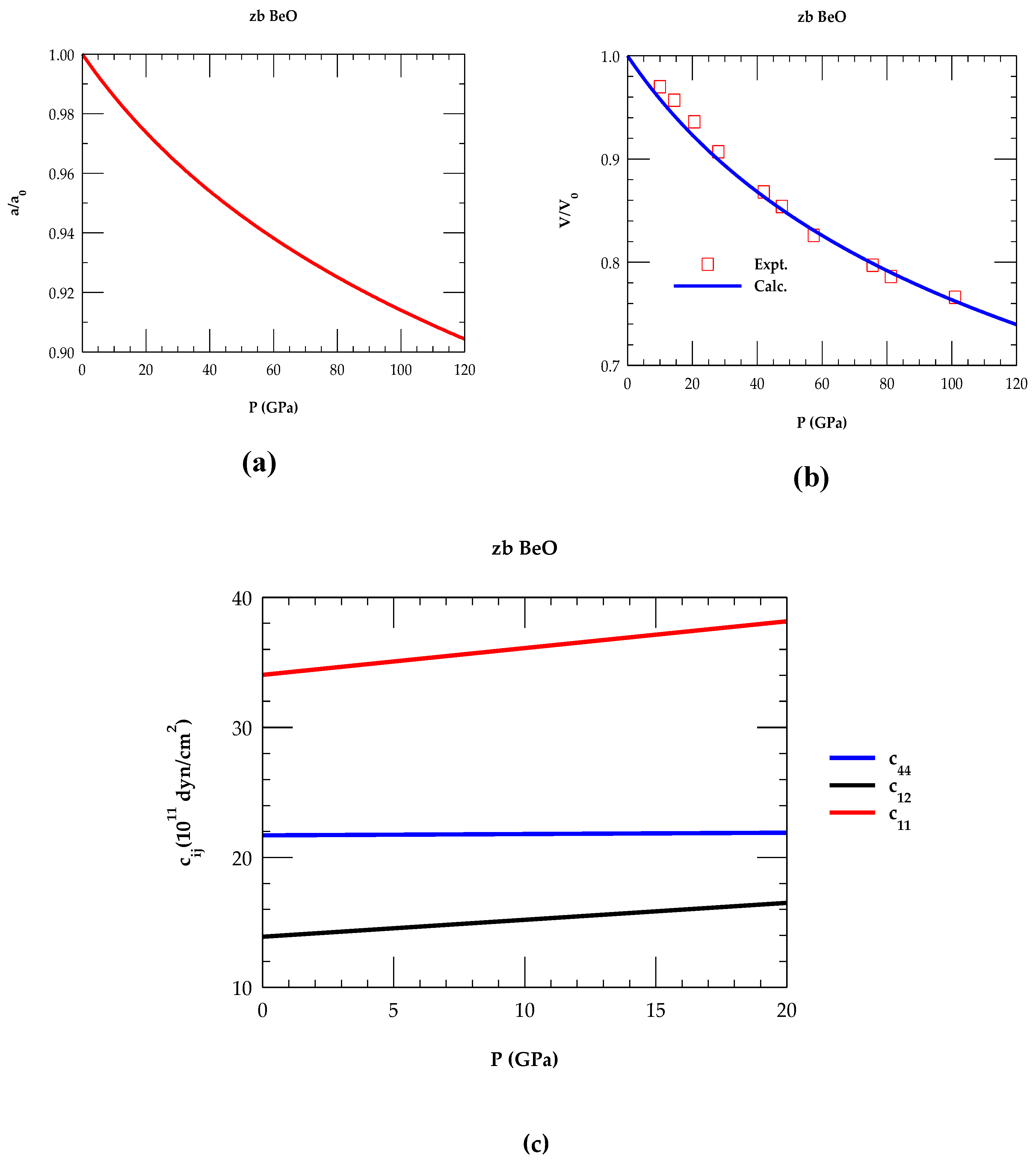

3.1. Pressure Dependent Lattice and Elastic Constabts of zb BeO

3.1.1. Interatomic Force Constants of zb BeO at P≠ 0 Gpa

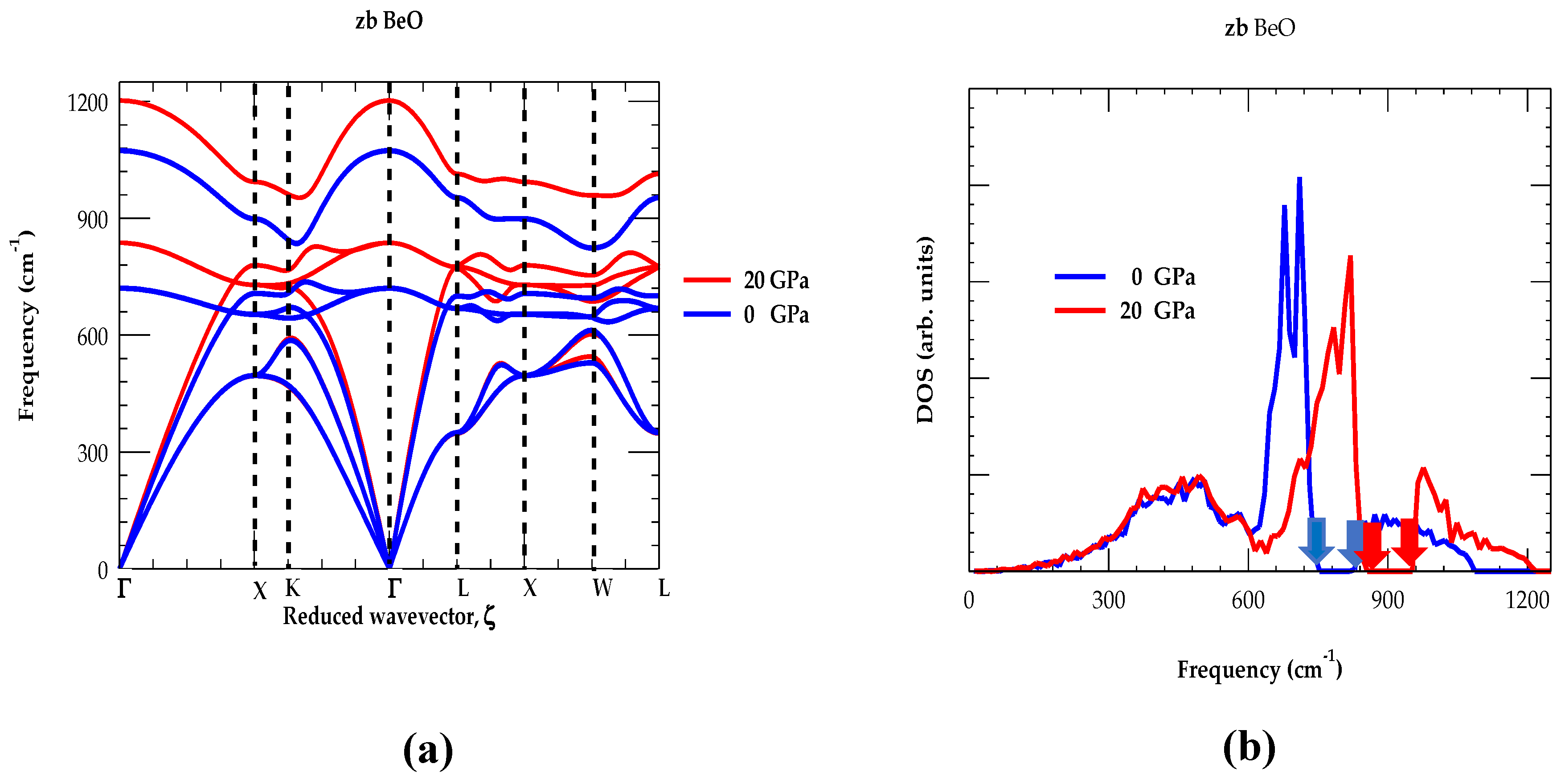

3.1.2. Phonon Dispersions and Density of States

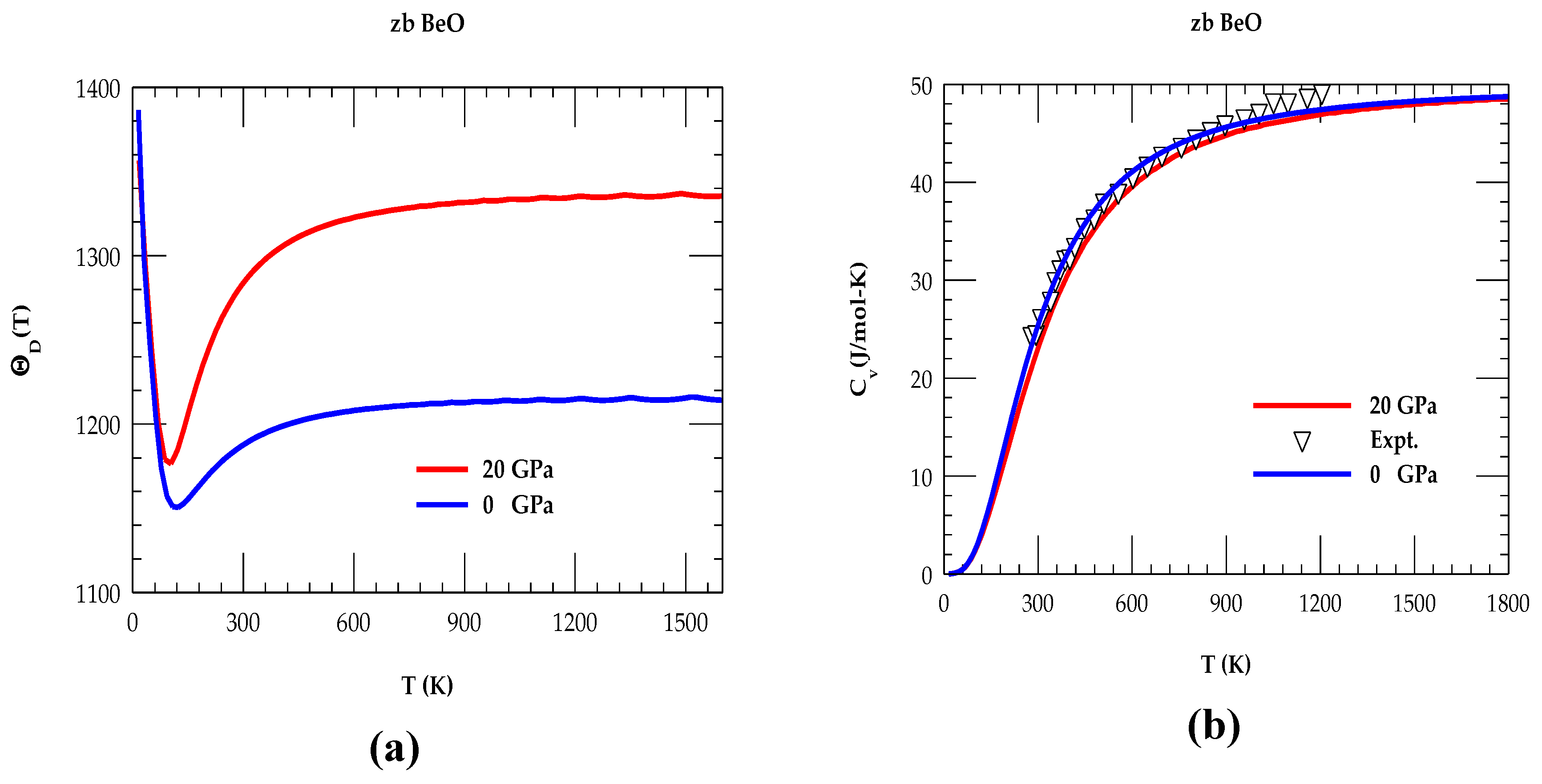

3.1.3. Debye Temperature and Specific Heat

3.2. Pressure Dependent Characteristics of zb BeO

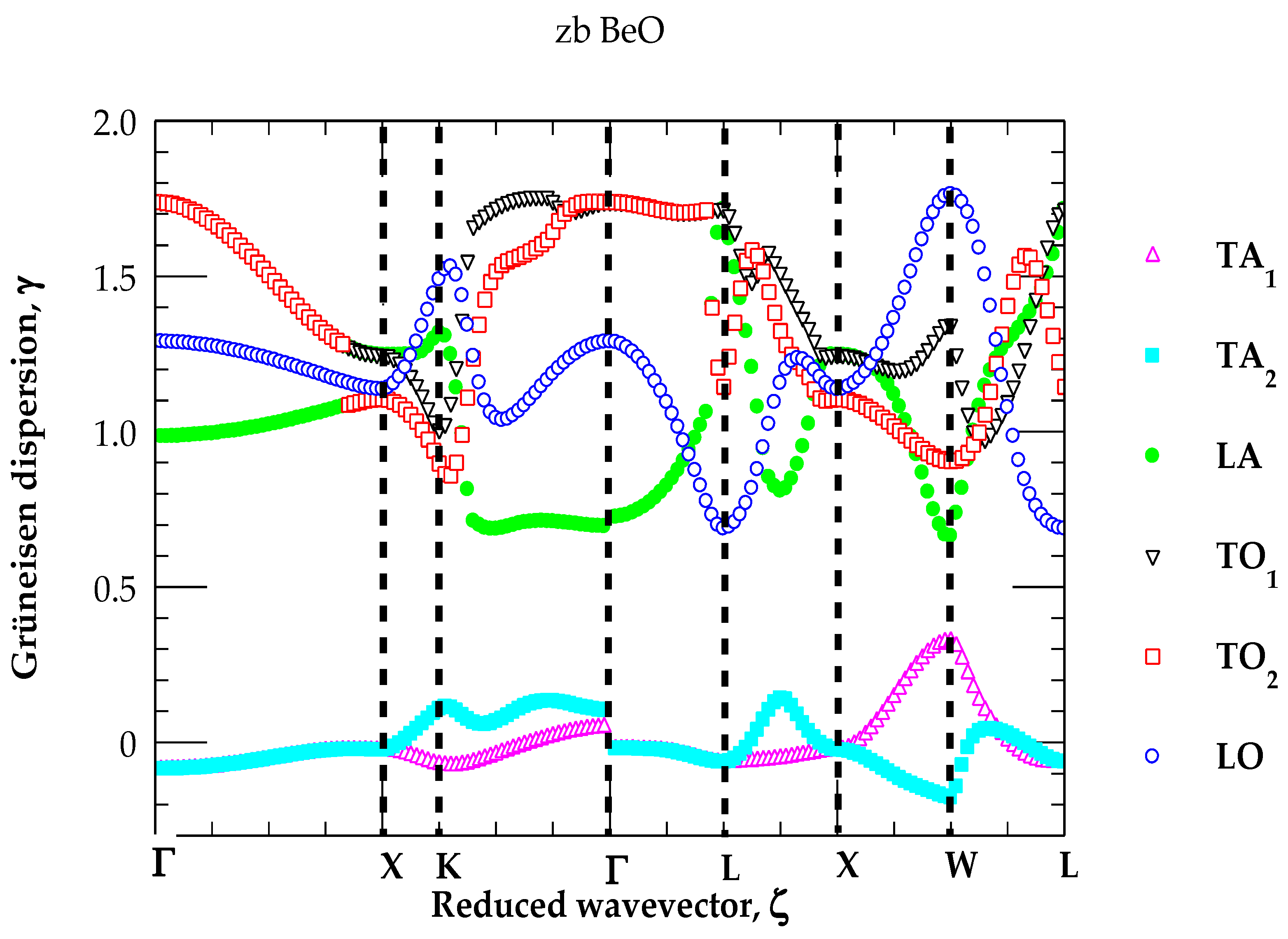

3.2.1. Grüneisen Dispersions

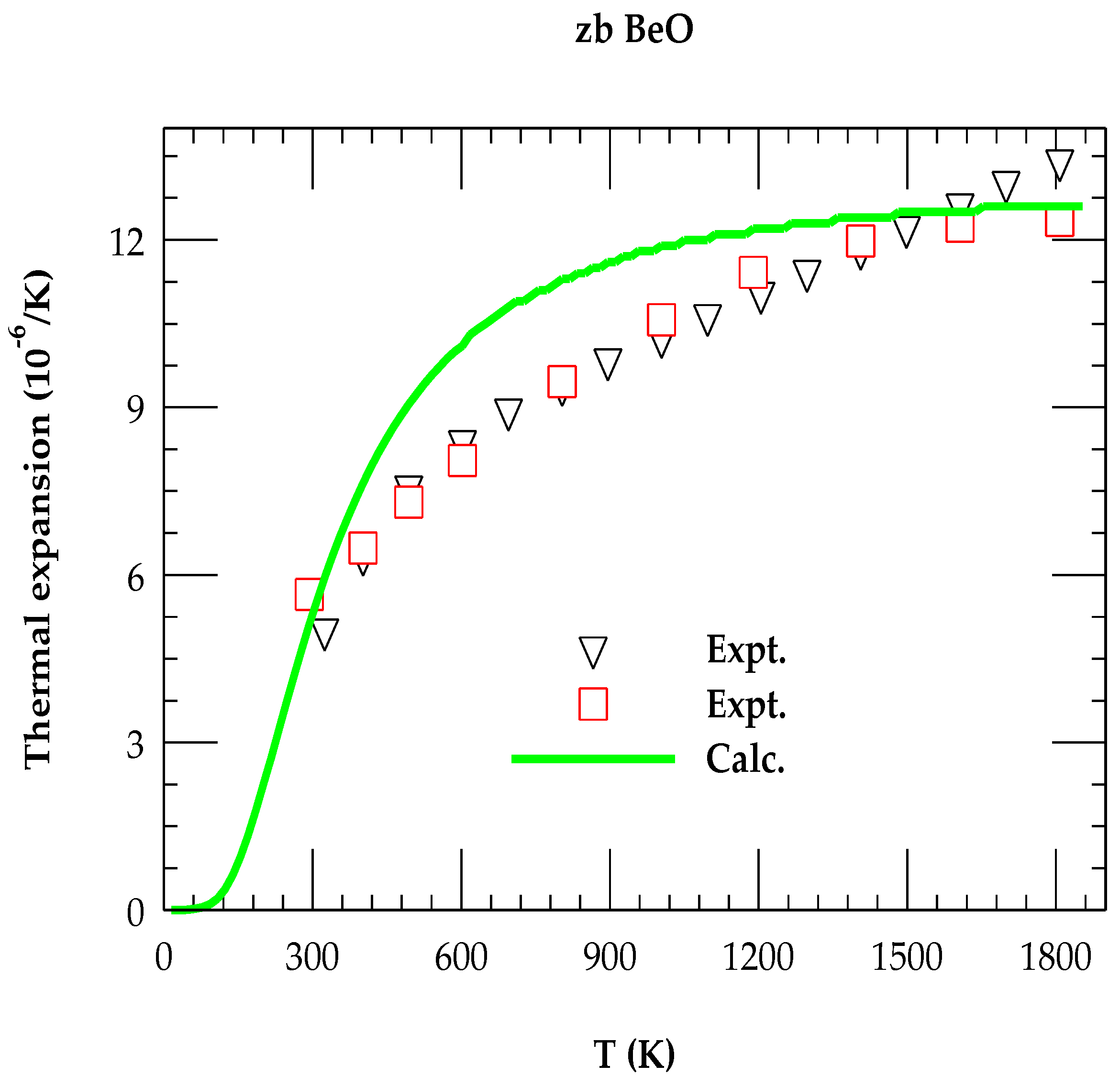

3.2.2. Thermal Expansion Coefficient

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Sharma, D.K.; Shukla, S.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, V. A review on ZnO: Fundamental properties and applications. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 49, 3028–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, C.; Suresh, J.; Gayathri, V.; Sowmya, S.; Augustine, D.; Alamoudi, A.; Zidane, B.; Albar, N.H.M.; Patil, S. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: A Review on Its Applications in Dentistry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 917990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysiewicz, M.A. ZnO as a Functional Material, a Review. Crystals 2019, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.; Norton, D.; Ip, K.; Heo, Y.; Steiner, T. Recentprogress in processing and properties of ZnO. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2005, 50, 293–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Mende, L.; MacManus-Driscoll, J.L. ZnO nanostructures, defects, and devices. Mater. Today 2007, 10, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgür, Ü.; Alivov, Y.I.; Liu, C.; Teke, A.; Reshchikov, M.A.; Doğan, S.; Avrutin, V.; Cho, S.-J.; Morkoç, H. A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Sashin, V.; A Bolorizadeh, M.; Kheifets, A.S.; Ford, M.J. Electronic band structure of beryllium oxide. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2003, 15, 3567–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.A.; Shannon, R.D.; Chai, B.H.T.; Abraham, M.M.; Wintersgill, M.C. Dielectric Constants of BeO, MgO, and CaOUsing the Two-Terminal Method. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1989, 16, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, K.; Yong, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Nahm, H.-H.; Yoo, J.; Lee, C.; Hwang, C.S.; Han, S. Novel high-κ dielectrics for next-generation electronic devices screened by automated ab initio calculations. NPG Asia Mater. 2015, 7, e190–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, J.; Akyol, T.; Lei, M.; Ferrer, D.; Hudnall, T.; Downer, M.; Bielawski, C.; Bersuker, G.; Lee, J.; Banerjee, S. Electrical and physical characteristics for crystalline atomic layer deposited beryllium oxide thin film on Si and GaAs substrates. Thin Solid Films 2011, 520, 3091–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, J.H.; Akyol, T.; Ferrer, D.A.; Lee, J.C.; Banerjee, S.K.; Lei, M.; Downer, M.; Hudnall, T.W.; Bielawski, C.W.; Bersuker, G. Comparison of the self-cleaning effects and electrical characteristics of BeO and Al2O3 deposited as an interface passivation layer on GaAs MOS devices. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2011, 29, 061501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarano, D.M.; Mansur, F.A.; Santos, A.M.M.; Ribeiro, L.S. Thermal Conductivity of UO2–BeO–Gd2O3 Nuclear Fuel Pellets. Int. J. Thermophys. 2019, 40, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouli, D.; Revankar, S.T. Development of Thermal Models and Analysis of UO2-BeO Fuel during a Loss of Coolant Accident. Int. J. Nucl. Energy 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yuan, C. Neutronic study of UO2-BeO fuel with various claddings. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.B.; Brito, R.A.; Ortega, L.H.; Malone, J.P.; McDeavitt, S.M. Manufacture of a UO2-Based Nuclear Fuel with Improved Thermal Conductivity with the Addition of BeO. Met. Mater. Trans. E 2017, 4, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolay, S.; Faÿ, S.; Ballif, C. Growth Model of MOCVD Polycrystalline ZnO. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 4957–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Shi, Z.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B. Nucleation and growth of ZnO films on Si substrates by LP-MOCVD. Superlattices Microstruct. 2014, 71, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdou, Z.; Shulin, G.; Jiandong, Y.; Wei, L.; Shunmin, Z.; Feng, Q.; Liqun, H.; Rang, Z.; Yi, S. , MOCVD Growth and Properties of ZnO and Znl-x,MgxO Films, IEEE 2003, 0-7803-7887-3/03/$17. 00 0 2003.

- Kadhim, G.A. Study of the structural and optical traits of In:ZnO thin films via spray pyrolysis strategy: Influence of laser radiation change in different periods. 2ND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE FOR ENGINEERING SCIENCES AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (ESIT 2022): ESIT2022 Conference Proceedings. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IraqDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 240006.

- Wei, X.H.; Li, Y.R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.B.; Ji, H. Epitaxial properties of ZnO thin films on SrTiO3 substrates grown by laser molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 151918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.H.; Li, Y.R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.B.; Ji, H. Epitaxial properties of ZnO thin films on SrTiO3 substrates grown by laser molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 151918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, M.; Geprägs, S.; Althammer, M.; Brenninger, T.; Gross, R. Laser molecular beam epitaxy of ZnO thin films and heterostructures. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2013, 47, 034002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauveau, J.-M.; Morhain, C.; Teisseire, M.; Laügt, M.; Deparis, C.; Zuniga-Perez, J.; Vinter, B. (Zn, Mg)O/ZnO-based heterostructures grown by molecular beam epitaxy on sapphire: Polar vs. non-polar. Microelectron. J. 2009, 40, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, T.; Takahashi, R.; Lippmaa, M. Pulsed laser deposition of epitaxial BeO thin films on sapphire and SrTiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 231608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triboulet, R.; Perrie`re, J. , Epitaxial growth of ZnO films, Progress in Crystal Growth and Characterization of Materials 2003, 47 65-138.

- Yıldırım, Ö.A.; Durucan, C. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles elaborated by microemulsion method. J. Alloy. Compd. 2010, 506, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhu, L.; Liao, G. Solvothermal synthesis and photocatalytic properties of ZnO micro/nanostructures. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Jr, E.A.; Nobre, F.X.G.S.; Cavalcante, L.S.; Santos, M.R.M. C.; Souza, F. L.; de Matos, J.M.E. , Synthesis, growth mechanism, optical properties and catalytic activity of ZnO microcrystals obtained via hydrothermal processing, RSC Adv. , 2017, 7, 24263–24281. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.A.; Evans, J.E.; Smith, N.A.; Tarat, A.; Jones, D.R.; Barnett, C.J.; Maffeis, T.G.G. The effect of metal layers on the morphology and optical properties of hydrothermally grown zinc oxide nanowires. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 4908–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horio, Y.; Yuhara, J.; Takakuwa, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Abe, K. Polarity identification of ZnO(0001) surface by reflection high-energy electron diffraction. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bagnall, D.; Yao, T. ZnO as a novel photonic material for the UV region. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2000, 75, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.R.S.; Erni, R.; Lin, H.-Y.; Wang, R.-C.; Liu, C.-P. Characterization of wurtzite ZnO using valence electron energy loss spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaida, T.; Kamioka, K.; Ida, T.; Kuriyama, K.; Kushida, K.; Kinomura, A. Rutherford backscattering and nuclear reaction analyses of hydrogen ion-implanted ZnO bulk single crystals. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interactions Mater. Atoms 2014, 332, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.A.; Taha, K.K.; Modwi, A.; Khezami, L. , ZnO Nanoparticles: Surface and x-ray profile analysis, Journal of Ovonic Research 2018, 14, 381 – 393.

- Mohan, A.C.; Renjanadevi, B. Preparation of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and its Characterization Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and X-Ray Diffraction(XRD). Procedia Technol. 2016, 24, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Tomás, M.C.; Hortelano, V.; Jiménez, J.; Wang, B.; Muñoz-Sanjosé, V. High resolution X-ray diffraction, X-ray multiple diffraction and cathodoluminescence as combined tools for the characterization of substrates for epitaxy: the ZnO case. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 3951–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.-C.; Yang, S.-H. Growth and Auger electron spectroscopy characterization of donut-shaped ZnO nanostructures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 7162–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.; Li, X. Young’s modulus of ZnO nanobelts measured using atomic force microscopy and nanoindentation techniques. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 3591–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmse, H.; Sparenberg, M.; Zykov, A.; Sadofev, S.; Kowarik, S.; Blumstengel, S. Structure of p-Sexiphenyl Nanocrystallites in ZnO Revealed by High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 2789–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, S.; Deng, S.; Wei, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Q. Direct Observation of the Layer-by-Layer Growth of ZnO Nanopillar by In situ High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouf, D. , Synthesis and photoluminescence characterization of ZnO nanoparticles, Journal of Luminescence 2013, 134, 213–219.

- Saadatkia, P.; Ariyawansa, G.; Leedy, K.D.; Look, D.C.; Boatner, L.A.; Selim, F.A. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Measurements of Multi-phonon and Free-Carrier Absorption in ZnO. J. Electron. Mater. 2016, 45, 6329–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, B.; Gedvilas, L.; Li, X.; Coutts, T. Infrared spectroscopy of polycrystalline ZnO and ZnO:N thin films. J. Cryst. Growth 2005, 281, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, T.C.; Porto, S.P.S.; Tell, B. Raman Effect in Zinc Oxide. Phys. Rev. B 1966, 142, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, J.M.; Cardona, M. , Resonant raman scattering in ZnO, Phys. Rev. B 1977, 16, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjón, F.J.; Syassen, K.; Lauck, R. Effect of Pressure on Phonon Modes in Wurtzite Zinc Oxide. High Press. Res. 2002, 22, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokila, A. Jagannatha Reddy, M.K.; Nagabhushana, H.; Rao, J.L.; Shivakumara, C.; Nagabhushana, B.M.; Chakradhar, R.P.S.

- Combustion synthesis, characterization and Raman studies of ZnO nano powders, Spectrochimica Acta Part A 2011, 81 53–58.

- Serrano, J.; Manjón, F.J.; Romero, A.H.; Ivanov, A.; Cardona, M.; Lauck, R.; Bosak, A.; Krisch, M. , Phonon dispersion relations of zinc oxide: Inelastic neutron scattering and ab initio calculations, Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 174304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Romero, A.H.; Manjo’n, F.J.; Lauck, R.; Cardona, M.; Rubio, A. , Pressure dependence of the lattice dynamics of ZnO: An ab initio approach, Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 094306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Manjón, F.J.; Romero, A.H.; Ivanov, A.; Lauck, R.; Cardona, M.; Krisch, M. The phonon dispersion of wurtzite-ZnO revisited. Phys. Status solidi (b) 2007, 244, 1478–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohórquez, C.; Bakkali, H.; Delgado, J.J.; Blanco, E.; Herrera, M.; Domínguez, M. Spectroscopic Ellipsometry Study on Tuning the Electrical and Optical Properties of Zr-Doped ZnO Thin Films Grown by Atomic Layer Deposition. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.P.; Sapkota, D.R.; Ramanujam, B. Spectroscopic-ellipsometry study of the optical properties of ZnO nanoparticle thin films. MRS Commun. 2024, 14, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibueze, T. Ab initio study of mechanical, phonon and electronic Properties of cubic zinc-blende structure of ZnO. Niger. Ann. PURE Appl. Sci. 2021, 4, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.; Ahmed, S.; Shakil, M.; Choudhary, M.A. First-principles calculations of structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of ZnxO1−xSx alloys. Chin. Phys. B 2014, 23, 106108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Han, H.; Zhang, C.; Cai, T.; Song, C.; Gao, T. , Ab initio study of structural, dielectric, and dynamical properties of zinc-blende ZnX (X = O, S, Se, Te), Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2009, 471, 492–497.

- Singh, J.; Jain, V.K. , Structural, Electronic and Optical Properties of ZnO Material Using First Principle Calculation, Journal of Polymer & Composites 2023, 11, S27; ISSN: 2321-8525.

- Mohammadi, A.S.; Baizaee, S.M.; Salehi, H. , Density Functional Approach to Study Electronic Structure of ZnO Single Crystal, World Appl. Sci. J. 2011, 14, 1530–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Charifi, Z.; Baaziz, H.; Reshak, A.H. Ab-initio investigation of structural, electronic and optical properties for three phases of ZnO compound. Phys. Status solidi (b) 2007, 244, 3154–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, X.; Zhang, C.; Gong, J.; Chen, S. Ab initio study of photoelectric properties in ZnO transparent conductive oxide. Vacuum 2021, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-F.; Liu, H.-F.; Tian, E. Structural and thermodynamic properties of hexagonal BeO at high pressures and temperatures. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocharov, D.; Pudza, I.; Klementiev, K.; Krack, M.; Kuzmin, A. Study of High-Temperature Behaviour of ZnO by Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Simulations and X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Materials 2021, 14, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.; Czerner, M.; Edalati-Boostan, S.; Heiliger, C. Ab initio calculations of phonon transport in ZnO and ZnS. Eur. Phys. J. B 2012, 85, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Q. First-principles study of negative thermal expansion in zinc oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 063508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Xiang, B.; Gao, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, H. Ab initio study of lattice instabilities of zinc chalcogenides ZnX (X=O, S, Se, Te) induced by ultrafast intense laser irradiation. AIP Adv. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, A.; Nardelli, M.B. Dielectric properties and Raman spectra of ZnO from a first principles finite-differences/finite-fields approach. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, srep02999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Allen, P.B. Internal and external thermal expansions of wurtzite ZnO from first principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 154, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, S.; Sütlü, A.; Bağcı, S.; Tütüncü, H.M.; Srivastava, G.P. Structural, elastic, electronic, and phonon properties of zinc-blende and wurtzite BeO. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 033719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, K. Dynamique de réseau de composés ANB8-N présentant la structure de la blende. Ann. Phys. (Paris) 1973– 1974, 8, 319–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N. Computational phonon dispersions structural and thermodynamical characteristics of novel C-based XC (X = Si, Ge and Sn) materials. Next Mater. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N.; Vandevyver, M. Pressure-dependent phonon properties of III-V compound semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1990, 41, 12129–12139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N.; Becla, P. Microhardness, Young’s and Shear Modulus in Tetrahedrally Bonded Novel II-Oxides and III-Nitrides. Materials 2025, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, D.N.; Sherbondy, J.C. Thermal expansion coefficient of 3C–SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1995, 67, 3301–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N. Phonon excitations and thermodynamic properties of cubic III nitrides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 1553–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N. Pressure-dependent mode Grüneisen parameters and their impact on thermal expansion coefficient of zinc-blende InN. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 8379–8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnaghan, F.D. The Compressibility of Media under Extreme Pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1944, 30, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Niiya, N.; Ukegawa, K.; Mizuno, T.; Takarabe, K.; Ruoff, A.L. High-pressure X-ray structural study of BeO and ZnO to 200 GPa. Phys. Status solidi (b) 2004, 241, 3198–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, K.W.; Pohl, U.W. , Phonon-induced thermal properties, Semiconductor Physics DOI 10, 1007/978-3-319-06540-3_5-1 (Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014).

- Morkoç, H.; Özgür, Ü. Zinc Oxide: Fundamentals, Materials and Device Technology; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; ISBN 978-3-527-40813-9. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, B.; Cooper, R.F.; Kreitman, M.M. Low-Temperature Thermal Expansion of Zinc Oxide. Vibrations in Zinc Oxide and Sphalerite Zinc Sulfide. Phys. Rev. B 1971, 4, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibach, H. Thermal Expansion of Silicon and Zinc Oxide (II). Phys. Status solidi (b) 1969, 33, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, G.A.; Bartram, S.F. Thermal expansion of some diamondlike crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1975, 46, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskii, Y.M.; Stankus, S.V. Thermal expansion of beryllium oxide in the temperature interval 20−1550°C. High Temp. 2014, 52, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Cheng, Y.; Cai, L.C.; Chen, X.R. , Structure and thermodynamic properties of BeO: Empirical corrections in the quasi-harmonic approximation, J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 033517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowik, U.D. , Structural stability and thermal properties of BeO from the quasi-harmonic approximation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2010, 22, 045404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahariah, M.B.; Ghosh, S. Dynamical stability and phase transition of BeO under pressure. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 083520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.-R.; Yang, J.-W.; Guo, H.-Z.; Ji, G.-F.; Chen, X.-R. Phase transition and elastic properties of BeO under pressure from first-principles calculations. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2009, 404, 1940–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Zhang, P.; Song, H.F.; Liu, H.F. , Mean-field potential calculations of high-pressure equation of state for BeO. Chin. Phys. B 2008, 17, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Bosak, A.; Schmalzl, K.; Krisch, M.; van Beek, W.; Kolobanov, V. , Lattice dynamics of beryllium oxide: inelastic x-ray scattering and ab initio calculations, Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 224303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahariah, M.B.; Ghosh, S. , Ab initio calculation of lattice dynamics in BeO, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 395201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrani, B.; Hassan, F.E.H.; Akbarzadeh, H. First-principles investigations of the ground-state and excited-state properties of BeO polymorphs. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-F.; Liu, H.-F.; Tian, E. Structural and thermodynamic properties of hexagonal BeO at high pressures and temperatures. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2007, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wu, S.; Xu, R.; Yu, J. Pressure-induced phase transition and its atomistic mechanism in BeO: A theoretical calculation. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 184104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-J.; Lee, S.-G.; Ko, Y.-J.; Chang, K.J. Theoretical study of the structural phase transformation of BeO under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 13501–13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Van Camp, P.; E Van Doren, V. Ground-state properties and structural phase transformation of beryllium oxide. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 1996, 8, 3385–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettger, J.C.; Wills, J.M. Theoretical structural phase stability of BeO to 1 TPa. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 8965–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourouklis, G.A.; Sood, A.K.; Hochheimer, H.D.; Jayaraman, A. High-pressure Raman study of the optic-phonon modes in BeO. Phys. Rev. B 1985, 31, 8332–8334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karch, K.; Bechstedt, F. , Ab initio lattice dynamics of BN and AlN: Covalent versus ionic forces, Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavone, P.; Karch, K.; Schiitt, O.; Windl, W.; Strauch, D.; Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.

- Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 3156. [Google Scholar]

- Erba, A. On combining temperature and pressure effects on structural properties of crystals with standard ab initio techniques. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 124115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.-J.; Chen, X.-R.; Cui, H.-L.; Bai, Y.-L. First-principles calculations of elastic constants of c-BN. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2006, 382, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C. High-pressure lattice dynamics and thermodynamic properties of zinc-blende BN from first-principles calculation. Phys. Lett. A 2009, 373, 2082–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, B.A.; Zallen, R. , Pressure-Raman effects in covalent and molecular solids, in Light Scattering in Solids IV, edited by M. Cardona and G. Guntherodt, Topics in Applied Physics (Springer, Berlin, 1984), Vol. 54, pp. 463–527; see, especially, Table 8.1 and pp. 492–497 in this review.

- Wang, S.-M.; Wu, J.-X.; Gunawan, H.; Tu, R.-Q. Optimization of Machining Parameters for Corner Accuracy Improvement for WEDM Processing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D.N.; Becla, P. Composition-Dependent Structural, Phonon, and Thermodynamical Characteristics of Zinc-Blende BeZnO. Materials 2025, 18, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material |

a) and / |

B4→ B1 a) | Others a) | B3→ B1 a) | Othersa) | B4→ B3 a) | Others a) |

| BeO |

(GPa) |

137.3 147.0 |

21.7; 40.0; 95.0 | 139.0 95.0 |

94.0-147.0 94.0-96.0 |

74.0 91.0 |

62–91 |

|

(%) |

11.20 | 11.0 |

| zb BeO (our) a), | Others b) | |

|

|

1074 721 |

1060 683 |

|

|

899 653 707 496 |

900 655 708 493 |

|

|

953 669 701 349 |

902 663 702 310 |

|

|

3.81 | 3.72-3.83 |

|

|

34.2 | 34.2 |

|

|

13.9 | 13.9-14.8 |

|

|

21.7 | 20.8-21.7 |

| B0 | 207 | 201-229 |

|

|

3.7 | 3.65-3.96 |

| RIM a) | zb BeO | |

| Parameters | P = 0 GPa | P= 20 GPa |

| A | -0.62022 | -0.806 |

| B | -0.55000 | -0.74 |

| C1 | -0.06650 | -0.0715 |

| C2 | -0.09300 | -0.102 |

| D1 | -0.04144 | -0.02497 |

| D2 | -0.14900 | -0.1634 |

| E1 | -0. 10000 | -0.18 |

| E2 | 0.04000 | 0.04 |

| F1 | 0.15500 | 0.218 |

| F2 | -0.12500 | -0.106 |

| Zeff | 1.0133 | 1.056 |

|

Modes zb BeO |

Our RIMa) P = 0 Gpa |

Abinitio Calc.b) P = 0 Gpa |

Our RIMa) P = 20 Gpa |

RIM a) |

RIM a) |

|

|

1074 721 899 653 707 496 953 669 701 349 |

1060 683 900 655 708 493 902 663 702 310 |

1201 836 993 730 779 494 1013 775 777 347 |

6.35 5.75 4.70 3.85 3.60 -0.10 3.00 5.30 3.80 -0.10 |

1.29 1.74 1.14 1.25 1.10 -0.06 1.14 1.72 0.70 -0.06 |

| zb BeO Quantity | RIM, P = 0 GPaa) |

Others b) |

Others c) |

Others d) |

RIM, P = 20 GPaa) |

|

|

1390 | 1270; 1280 | 1370 | ||

|

|

1150 @ 124 K | 1177@ 93 K | |||

|

|

1187 | 1291 | |||

|

|

1214 @ 1000 K | 1335 @ 1850 K | |||

|

(100) |

3.17 | 2.67 | |||

|

(297) |

24.78 | 25.51-26.11 | 22.5 | ||

|

(High T) |

48.83 @ 1850 K | 48.72 @ 1150 K | 48.7 @ 1850 K | ||

|

|

5.12 | 5.65 @ 300 | 4.99 @ 293 | ||

|

|

7.64 | 6.48 @ 400 | 6.33 @ 373 | ||

|

|

9.24 | 7.30 @ 500 | 7.55 @ 473 | ||

|

|

12.5 | 12.25 @ 1600 | 12.60 @ 1573 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).