1. Introduction

Group-X transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs), with the general formula MX

2 (where M = Pt or Pd, and X = S, Se, or Te), have garnered considerable attention due to their tunable bandgaps, which range from the visible spectrum in monolayers to the mid-infrared in multilayer forms [

1]. These materials also exhibit high electron mobility [

2] and exceptional chemical stability under ambient and aqueous conditions [

3,

4], making them ideal candidates for a wide range of optoelectronic applications. Their unique properties have enabled progress in technologies such as broadband photodetectors [

5], light-emitting devices [

6], field-effect transistors [

7], label-free biosensors [

4,

8], holographic systems [

9], and nanoscale optical components like ultrathin lenses [

10]. A thorough understanding of their optical properties is therefore essential for optimizing their integration in advanced device architectures.

Among these TMDCs, platinum diselenide (PtSe

2) and platinum disulfide (PtS

2) stand out for their versatile electronic and optical behavior. PtSe

2 displays a thickness-dependent band structure, transitioning from a semiconducting monolayer to a semimetallic bulk phase. This feature enables precise tuning of its conductivity and bandgap, making it suitable for nanoelectronic applications. Furthermore, its high electron mobility and strong spin–orbit coupling make it a promising material for logic circuits, photodetectors, and spintronic devices [

11]. In contrast, PtS

2 retains semiconducting behavior even in multilayer configurations, with a notable indirect bandgap and high photoresponsivity under visible light [

12]. Both materials exhibit excellent ambient stability, which is critical for practical deployment. Optically, PtSe

2 and PtS

2 demonstrate strong light–matter interactions, high absorption coefficients across the visible to near-infrared range, and fast photoresponse times, rendering them attractive for broadband photodetection, optical modulation, and flexible sensing applications [

13,

14]. Additionally, their compatibility with layered heterostructures enables fine-tuning of optical responses through interlayer coupling and dielectric engineering.

The role of dielectric substrates, particularly polar materials such as silicon dioxide (SiO

2) and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), is pivotal in the fabrication of van der Waals heterostructures involving PtSe

2 and PtS

2. SiO

2, widely used in microelectronics as a gate dielectric, has a relatively low dielectric constant (~3.9), a wide bandgap (~9 eV), and supports surface optical (SO) phonon modes that can interact with charge carriers in adjacent 2D layers. This interaction, particularly via the long-range Fröhlich mechanism, can significantly influence carrier mobility, scattering processes, and the optical response of the TMDC layers, especially under high electric fields or elevated temperatures [

15,

16]. In contrast, hBN provides an atomically flat, chemically inert surface with high thermal conductivity and a wide bandgap (~6 eV). Its low defect density helps preserve the intrinsic properties of TMDC monolayers, while reducing charge in homogeneities and suppressing non-radiative recombination [

17,

18]. Understanding and tailoring the interaction between substrate phonons and 2D materials is therefore critical for enhancing charge transport and optical performance in TMDC-based heterostructures.

When integrated with insulating substrates such as SiO

2 and hBN, platinum-based TMDCs can form heterostructures with enhanced performance. PtSe

2/SiO

2 systems, for example, exhibit high carrier mobility and thickness-dependent bandgap transitions, enabling efficient photodetection across the visible to infrared range [

19]. Similarly, PtS

2 films grown on SiO

2 maintain stable semiconducting behavior and structural uniformity, making them suitable for field-effect transistors and optoelectronic devices [

12]. On the other hand, the use of hBN as a substrate offers considerable advantages due to its atomically smooth surface, wide bandgap, and chemical inertness. PtSe

2/hBN and PtS

2/hBN heterostructures preserve the intrinsic properties of the active TMDC layers while minimizing substrate-induced disorder and charge trapping effects [

20,

21]. These combinations result in improved electrical stability, enhanced optical performance, and low-noise operation, which are crucial for applications in flexible electronics, photodetectors, and spintronic devices.

Recent experimental and theoretical studies have shed light on the structural and functional characteristics of PtSe

2 and PtS

2 on dielectric substrates such as SiO

2 and hBN. Ullah et al., demonstrated the fabrication of high-performance PtSe

2/SiO

2 photodetectors with broadband sensitivity and ultrafast response, attributed to the high carrier mobility and tunable band structure of the PtSe

2 layer [

19]. In parallel, Aftab et al., reported on the deposition of environmentally stable PtS

2 thin films on SiO

2, highlighting their uniform morphology and sustained semiconducting nature, which are essential for integration into optoelectronic and FET devices [

12].

On the hBN side, Jia et al., achieved epitaxial growth of PtSe

2 on hBN using molecular beam epitaxy, demonstrating enhanced photodetector performance and reduced defect scattering due to the flat and inert nature of the substrate [

20]. Kim et al., also investigated charge transport in PtS

2/hBN heterostructures and observed low-noise performance and efficient carrier mobility, critical attributes for next-generation low-power and flexible devices [

21]. These combined efforts underscore the synergy between experimental and theoretical approaches in the design and optimization of Pt-based van der Waals heterostructures for advanced optoelectronic, sensing, and spintronic applications.

This study presents a detailed theoretical investigation of electron–surface optical phonon (SOP) interactions in monolayer platinum disulfide (PtS2) and platinum diselenide (PtSe2) deposited on polar dielectric substrates, namely silicon dioxide (SiO2) and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN). These interactions play a critical role in shaping the electronic and optical behavior of two-dimensional (2D) materials integrated into heterostructures. Our study begins with an analysis of the substrate-induced electron–phonon coupling mechanisms, followed by a quantitative evaluation of the resulting polaronic oscillator strength. This allows us to assess the extent to which the dielectric environment modifies the optical response of the monolayers. We further examine the temperature dependence of the polaronic scattering rate to elucidate the impact of thermal fluctuations on carrier dynamics. In addition, we analyze how the van der Waals (vdW) separation between the monolayer and the substrate influences SOP-mediated scattering, offering deeper insight into the interplay between interfacial geometry and many-body effects in 2D material systems.

2. Electron-Surface Optical Phonon Interaction in ML PtSe2 and PtS2 on Polar Substrates

Monolayer PtS

2 and PtSe

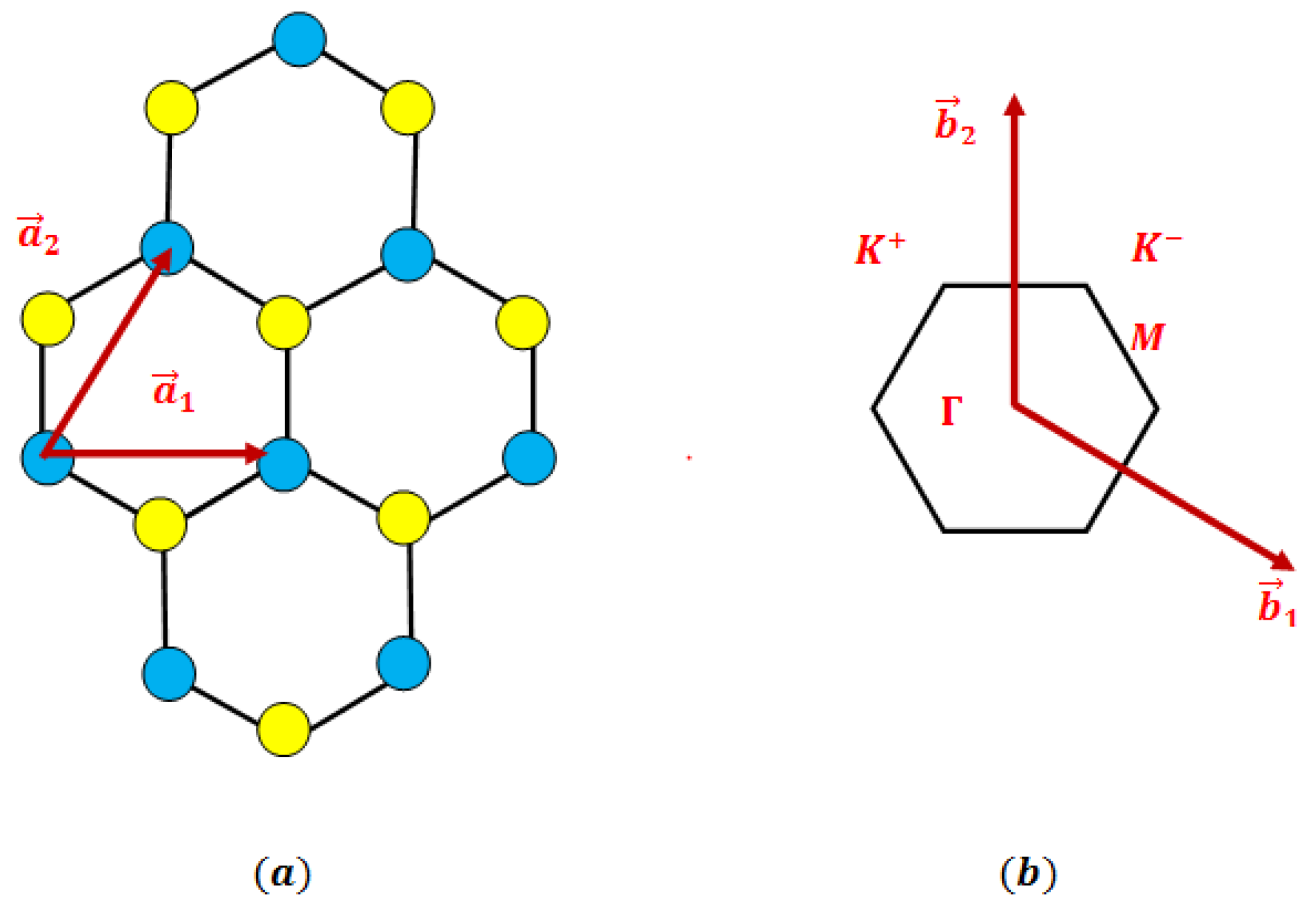

2 are part of the group-10 transition metal dichalcogenides and adopt a 1T-phase structure, where a central layer of platinum (Pt) atoms is sandwiched between two layers of chalcogen atoms—either sulfur (S) or selenium (Se). These atoms form a hexagonal lattice in which the Pt atoms are arranged in a two-dimensional triangular Bravais lattice, with the chalcogen atoms occupying aligned positions above and below the Pt plane. The real-space lattice is defined by the primitive vectors

and

, where

is the lattice constant (see

Figure 1. (a)). In reciprocal space, the structure is also triangular, with reciprocal lattice

and

(see

Figure 1. (b)). The first Brillouin zone is hexagonal and contains high-symmetry points such as Γ at the center, K

+ and K

− at the corners, and M at the midpoints of the edges. These points play a crucial role in determining the electronic, optical, and vibrational properties of PtS

2 and PtSe

2, particularly in the context of band structure and excitonic phenomena.

The corresponding reciprocal lattice also forms a hexagonal structure, with the first Brillouin zone exhibiting high-symmetry points labeled Γ, K, and M. These points play a crucial role in the electronic band structure. These points are critical for understanding the electronic band dispersion and optical transitions, particularly in the context of interband transitions and electron–phonon interactions. Notably, unlike other TMDCs such as MoS

2, PtSe

2 and PtS

2 exhibit an indirect band gap in their monolayer form, with the valence band maximum located at the Γ point and the conduction band minimum near the M point. This distinct band alignment influences their optical and transport properties, making them suitable for specific optoelectronic and sensing applications. The high-symmetry points denoted as

are defined as follows:

Near the K

+ point, the behavior of the conduction and valence band states with parallel spin

can be described using an effective

2×2 Hamiltonian, expressed as follows [

22,

23,

24]:

Here, represents the in-plane wave vector measured relative to the point. The parameter is proportional to the square of the interband momentum matrix element and is given by where denotes the effective mass of the electron, and corresponds to the band gap energy.

For spin sublevels with in the same valley, the Hamiltonian retains the structure of Equation (1), but with the band gap replaced by , where accounts for the combined spin–orbit splitting of the conduction and valence bands. In the valley, the corresponding effective Hamiltonian is obtained from Equation (1) by replacing with .

The energy dispersion relation obtained from the Hamiltonian in Equation (1) exhibits a Dirac-like form:

In this context, and refer to the conduction and valence bands, respectively. For the sake of computational feasibility, our study assumes idealized conditions with uniform, defect-free interfaces between the PtSe2 and PtS2 monolayers and the underlying dielectric substrates, an approximation commonly adopted in theoretical modeling and simulation.

In this study, we investigate the interaction between electrons and surface optical phonons (SOPs) in monolayer (ML) PtSe

2 and PtS

2 supported on SiO

2 and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) substrates, within the framework of long-range Fröhlich coupling. This model provides a solid theoretical foundation for describing electron–SOP interactions in these 2D materials on polar substrates. However, it involves several simplifying assumptions. For instance, it relies on the Born–Oppenheimer approximation [

25] and neglects short-range electron–phonon interactions, which may play a role in non-polar environments [

26]. The model also assumes a constant effective electron mass, and typically disregards non-linear effects and multi-phonon processes [

27]. Furthermore, it does not account for the presence of impurities, defects, or other sources of disorder [

25,

28]. Phonon dispersion is often approximated as linear, which may not be valid across all phonon branches or substrate types [

29]. Finally, the analysis usually focuses on a single dominant phonon mode, potentially overlooking contributions from other relevant modes.

For simplicity, the phonon spectrum is treated as isotropic, allowing us to classify phonons as either longitudinal or transverse. The electron–phonon interaction described by the Fröhlich Hamiltonian involves a scattering event in which an electron transitions from an initial momentum state

to a final state

, due to the emission or absorption of a phonon. In both processes, the conservation of total momentum holds and can be written as:

The term

represents the phonon energy contribution, accounting for both longitudinal optical (LO) and surface optical (SO) phonon modes, and is given by:

In this expression,

,

, denote the creation and annihilation operators, respectively, for a phonon with wave vector

, while

represents the phonon frequency associated with mode

. The second term,

, describes the electron–phonon interaction Hamiltonian [

30]:

The Fröhlich Hamiltonian, which describes the long-range interaction between electrons and polar optical phonons, is given by:

The interaction between charge carriers in monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2 and the surface optical phonons is described by the second term in Equation (6). The coupling matrix element

in the Fröhlich Hamiltonian quantifies the strength of the interaction between an electron in the monolayer and a surface optical phonon mode of the polar substrate. It is given by the following expression [

31,

32,

33]:

In this context,

denotes the strength of the polarization field associated with phonon mode

and is determined by the Fröhlich coupling constant [

34]:

Here,

and

are the static (low-frequency) and high-frequency dielectric constants of the polar substrate, respectively (see

Table 1). The parameter

represents the vertical separation between the monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2 and the polar substrate (see

Table 2). The quantity

corresponds to the energy of the surface optical (SO) phonons, with

denoting the two phonon branches.

The surface optical phonon (SOP) energies are derived from the bulk longitudinal optical (LO) phonon modes using the following relation [

30]:

The screening of the Coulomb interaction by the surrounding polar dielectric environment is accounted for using the parameter

. Due to the weak screening of the out-of-plane electric field in monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2,

is taken to be 1 [

43].

On polar substrates, surface optical phonons (SOPs) generate an electric field that interacts with electrons in the adjacent monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2. Based on equations (7) and (8), the SOP coupling strength can be expressed as:

The summation is carried out over a single spin orientation and a single valley. Here, represents the area of the two-atom unit cell, with being the lattice constant.

In this work, we adopt the same theoretical approach as outlined in our previous studies [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. To investigate the interaction between electrons and surface optical phonons in monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2, we focus on the electronic states

and

, associated with electron energies

and

, respectively. Additionally, we consider an effective 2×2 Hamiltonian that describes the conduction and valence band states with parallel spin projections

, in the vicinity of the

point of the hexagonal Brillouin zone.

The space of polaronic states arises from the tensor product of the electronic and phononic state subspaces. Consequently, we define new states, referred to as polaronic states, given by:

The polaronic electron energies

for the states

in monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2, on polar substrates are expressed as follows [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]:

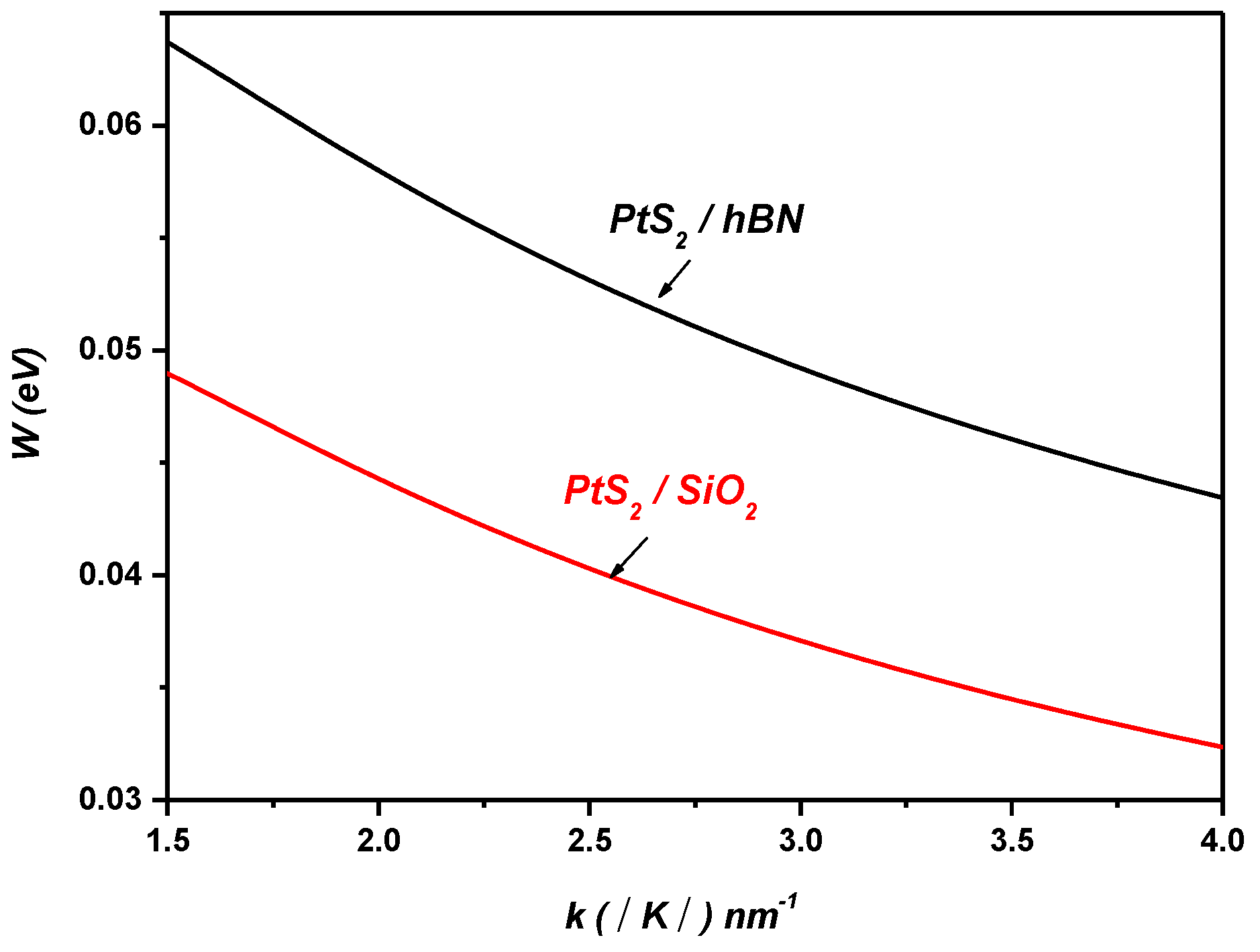

Figure 2 illustrates the strength of the surface optical (SO) coupling between the electronic states ⟩

and

as a function of the wave vector

in monolayer PtS

2 on SiO

2 and hBN polar substrates. As shown in

Figure 2, it is clear that the coupling with surface optical phonons is strongly dependent on the type of polar substrate.

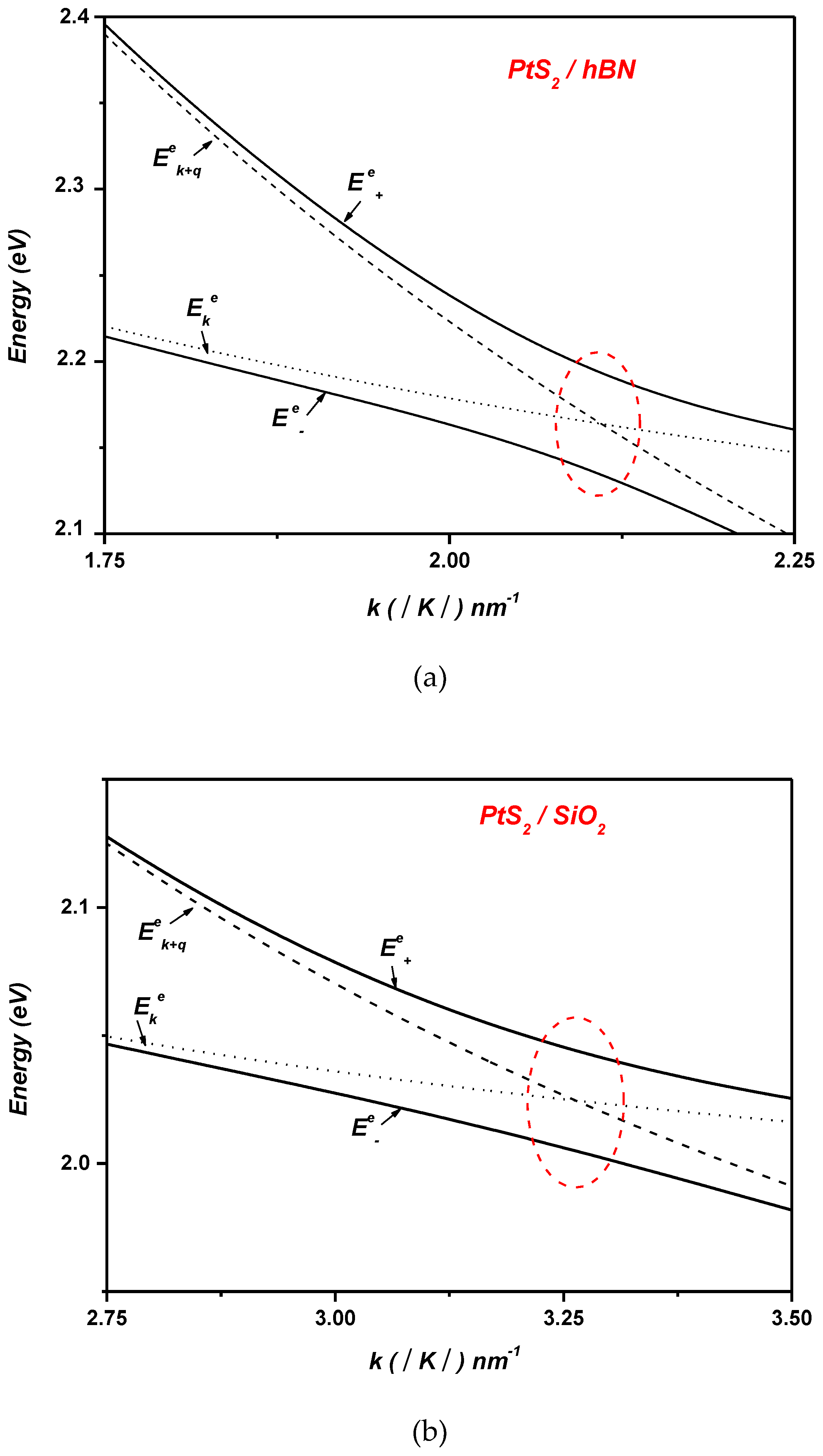

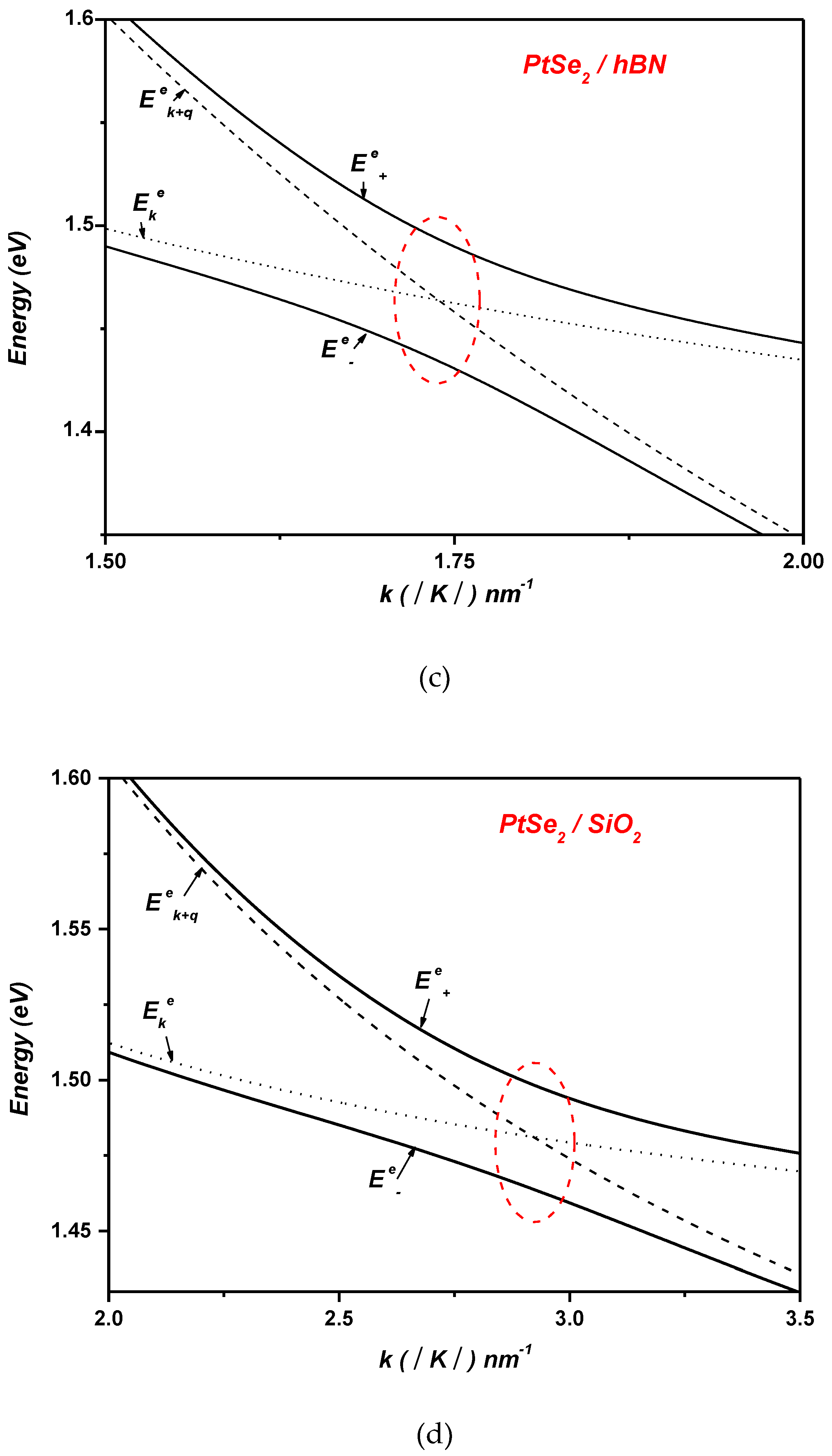

Figure 3 illustrates the polaronic electron energy dispersion as a function of the wave vector

for monolayer (ML) PtS

2 and PtSe

2 deposited on polar substrates, specifically SiO

2 and hBN. For reference, the corresponding non-interacting electronic states

and

are plotted alongside the interacting dispersion. In the case of PtS

2, the non-interacting energy branches intersect near

on SiO

2 and

on hBN, indicative of a resonant condition where the energy spacing between the electronic states coincides with the optical phonon energy

, which equals

for SiO

2 and

for hBN. These resonances lead to the emergence of pronounced anticrossings in the interacting spectrum, replacing the bare-level crossings and evidencing strong electron–phonon coupling. The resulting Rabi splittings reach approximately

on SiO

2 and

on hBN.

A similar behavior is observed for PtSe

2: the non-interacting states intersect around

on SiO

2 and

on hBN. Again, the condition for resonant coupling is met, with energy separations matching the corresponding phonon energies. The strong coupling regime manifests as anticrossings, with Rabi splittings of about

and

for SiO

2 and hBN, respectively. As highlighted in

Figure 3, the magnitude of the Rabi splitting is notably larger on hBN compared to SiO

2, underscoring an enhancement of the electron–phonon interaction strength in the hBN-supported configurations.

In polar substrates, surface optical (SO) phonons generate electric fields that penetrate into the adjacent monolayer, where they couple directly with electrons in PtSe2 and PtS2, layers via dipole interactions. This coupling significantly enhances the electron–phonon interaction strength, leading to a renormalization of the electronic states. As a result, the energy splitting between hybridized polaronic states increases, manifesting as an enhanced Rabi splitting.

The observed variation in Rabi splitting between silicon dioxide (SiO

2) and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) substrates (

Figure 3) arises from the distinct surface phonon characteristics, dielectric properties, and phonon energy scales of the two materials. hBN, for example, exhibits a higher static dielectric constant compared to SiO

2, which leads to stronger electric fields associated with its surface phonons at the interface. This results in a more pronounced coupling with monolayer PtSe

2 and PtS

2, electronic states, thereby amplifying the strength of the electron–phonon interaction and yielding a larger Rabi splitting.

Conversely, SiO2, due to its relatively lower dielectric constant, generates weaker electric fields associated with its surface optical phonons. As a result, the electron–phonon coupling with the PtSe2- and PtS2-monolayer is comparatively weaker, leading to a reduced Rabi splitting. This comparison highlights the crucial influence of the polar substrate in modulating the electron–phonon interaction strength, and consequently, in tuning the optical response and performance of monolayer PtSe2- and PtS2-based optoelectronic devices.

At the anticrossing points, the electronic wave functions become hybridized, enabling multiple transition pathways such as:

,

and

. This behavior indicates that the interaction between electrons and surface optical phonons (SOPs) cannot be treated within the weak-coupling regime. Instead, the strong coupling gives rise to Rabi splitting of the electronic levels. Theoretical calculations thus support the occurrence of energetically resonant coupling between electronic subbands and surface vibrational modes in monolayer TMDCs interfaced with the considered polar substrates. The resulting hybrid states, or polarons, can be expressed as:

The weight of the electronic component

and the weight of the one-phonon component

of the polaron states ± vary with the polaron energies

. The expressions detailing these dependencies are as follows [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]:

Here

is the SO coupling strength between the electronic states

[

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

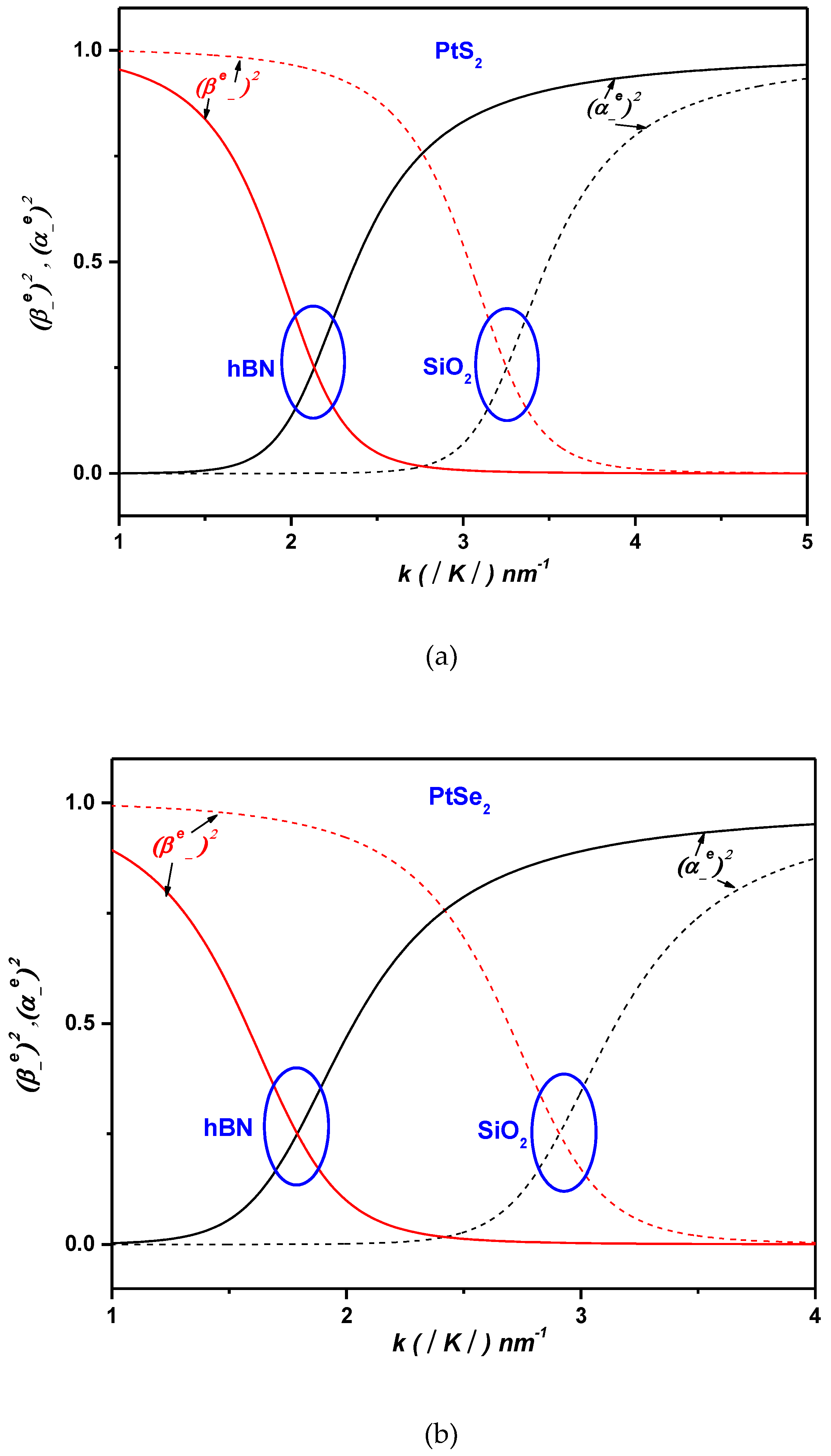

Figure 4 illustrates the variation of the electronic and one-phonon component weights of the lower polaron state

in monolayer (ML) PtS

2 and PtSe

2, supported on SiO

2 and hBN polar substrates, as a function of the wave vector

. Notably, for ML PtS

2 on hBN (refer to

Figure 4), the one-phonon component for the lower polaron state

becomes dominant near

, with its weight significantly exceeding that of the electronic component

. This behavior highlights the strong influence of surface optical phonons (SOPs) at the ML PtS

2/hBN interface, which facilitate resonant coupling between the non-interacting states

and

, thereby enabling polaron formation [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Similar trends are observed for the other configurations involving ML PtS

2 and PtSe

2 on both SiO

2 and hBN substrates (refer to

Figure 4).

3. Polaronic Oscillator Strength of ML PtS2 and PtSe2 on SiO2 and hBN Dielectric Polar Substrates

In this section, we present a theoretical analysis of the polaronic oscillator strength (OS), a key parameter characterizing light–matter interactions in these systems. Drawing an analogy with interband transitions in quantum dots, we evaluate the OS for interband transitions in ML PtS

2 and PtSe

2 placed on polar substrates. In the regime of strong confinement, the OS is directly related to the spatial overlap between polaronic states and is expressed in terms of the square modulus of the overlap integral,

, as given by the following relation [

53,

54]:

where

denotes the Kane energy, and

represents the emission energy associated with a single optical phonon in ML PtS

2 and PtSe

2 on polar substrates. The latter is given by:

Here,

is the energy of the lower polaron branch of the electron,

corresponds to the energy of the emitted optical phonon, and

denotes the electronic band gap of ML PtS

2 and PtSe

2. The oscillator strength (OS) has been calculated for the lower polaronic state

, which arises as a coherent superposition of the two basis states

and

:

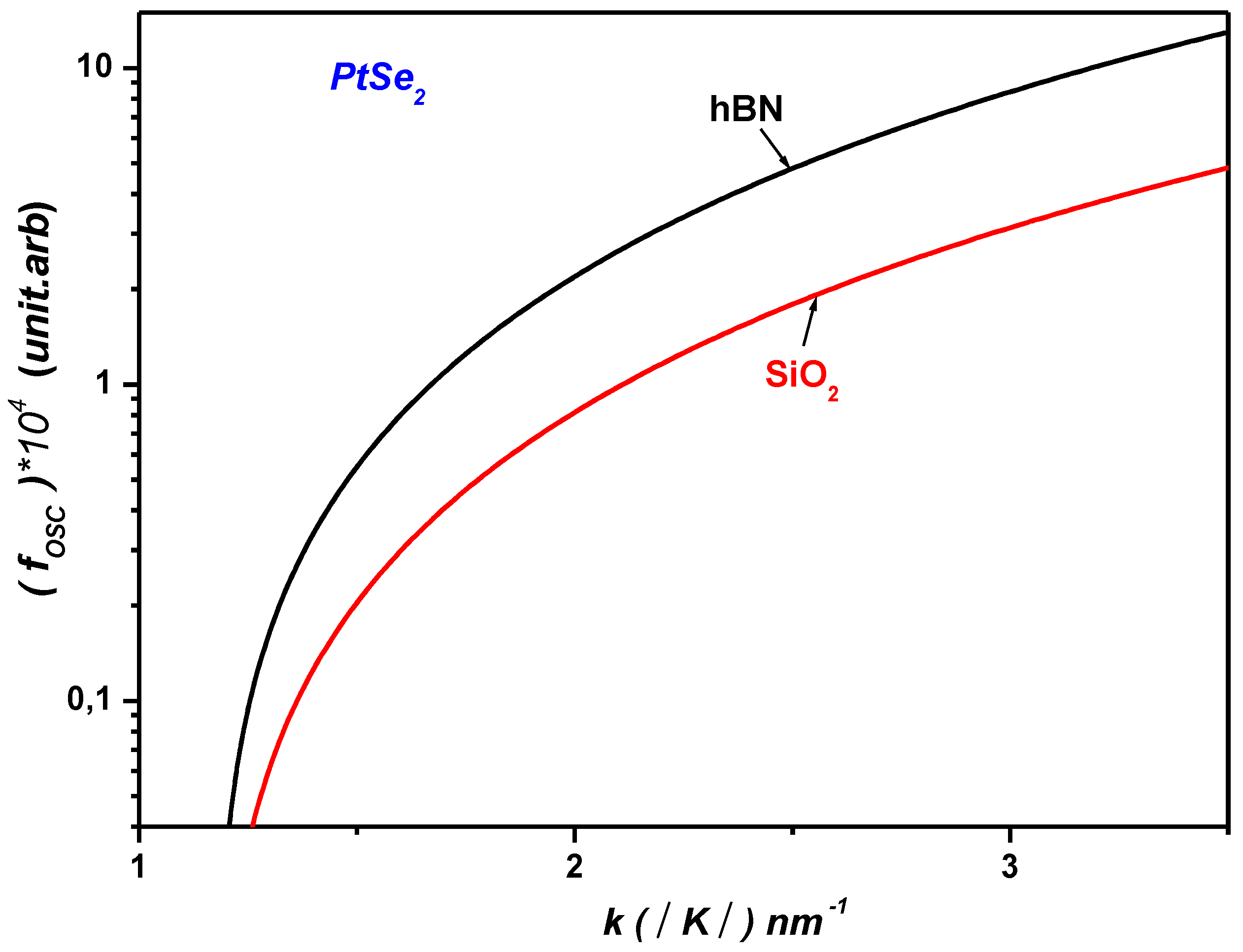

Figure 5 presents the calculated polaronic oscillator strength (OS) for monolayer PtSe

2 on SiO

2 and hBN substrates as a function of the wave vector

. Our theoretical analysis reveals that the polaronic OS is highly sensitive to the optical phonon modes of the surrounding dielectric environment. This sensitivity arises from the dependence of the phonon emission energy,

, on both the material’s band structure and the phonon characteristics of the substrate. Specifically, the emission energy is given by

, where

is the band gap and

is the lower polaron energy. Consequently, the strongest oscillator strength is observed for the substrate with the highest longitudinal optical phonon energy, confirming that

.

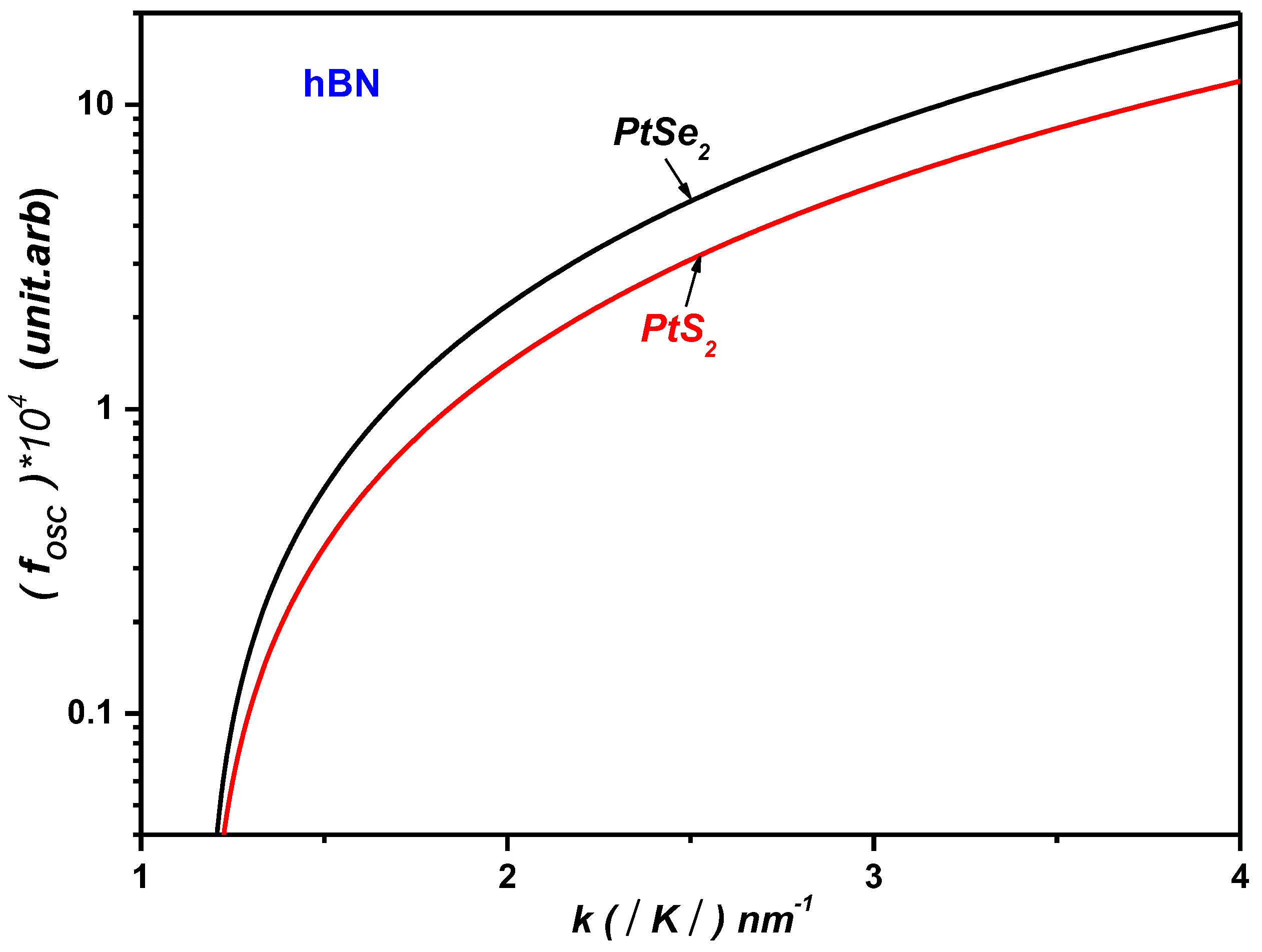

Using the same approach, it can be readily demonstrated that for monolayer PtS

2, the polaronic oscillator strength satisfies the inequality:

This behavior is attributed to the higher dielectric constant of

and the greater longitudinal optical (LO) phonon energy compared to that of

, (see

Table 1). Consequently, the polarization field induced at the ML–substrate interface is stronger for

, resulting in a more pronounced polaronic optical response in ML PtS

2 and PtSe

2 supported on hBN. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 6, the oscillator strength in ML PtSe

2 exceeds that in ML PtS

2:

This result is explained by the difference in the effective electron masses in the two materials. Heavier electrons, as found in ML PtS2, lead to reduced polaronic oscillator strength near the ML /dielectric interface. In contrast, lighter electrons, such as in ML PtSe2, result in a significant enhancement of the oscillator strength, particularly in the regime of strong confinement.

4. Polaronic Scattering Rate in ML and on Polar Substrates

We now examine the temperature dependence of the polaronic scattering rate induced by surface optical (SO) phonons. The SO phonon scattering rate, which quantifies the rate of momentum relaxation for polarons interacting with interface phonons, is expressed as follows [

55]:

Here,

denotes the Bose–Einstein occupation number of the phonons,

is the angle associated with the direction of the wave vector

, and

represents the squared modulus of the electron–phonon interaction matrix element, defined as:

The summation symbol ∑ is replaced by the integral

, which accounts for integration over the Brillouin zone while incorporating both spin and valley degrees of freedom. Here,

denotes the area of the elementary unit cell containing two atoms. Accordingly, the expression transforms into:

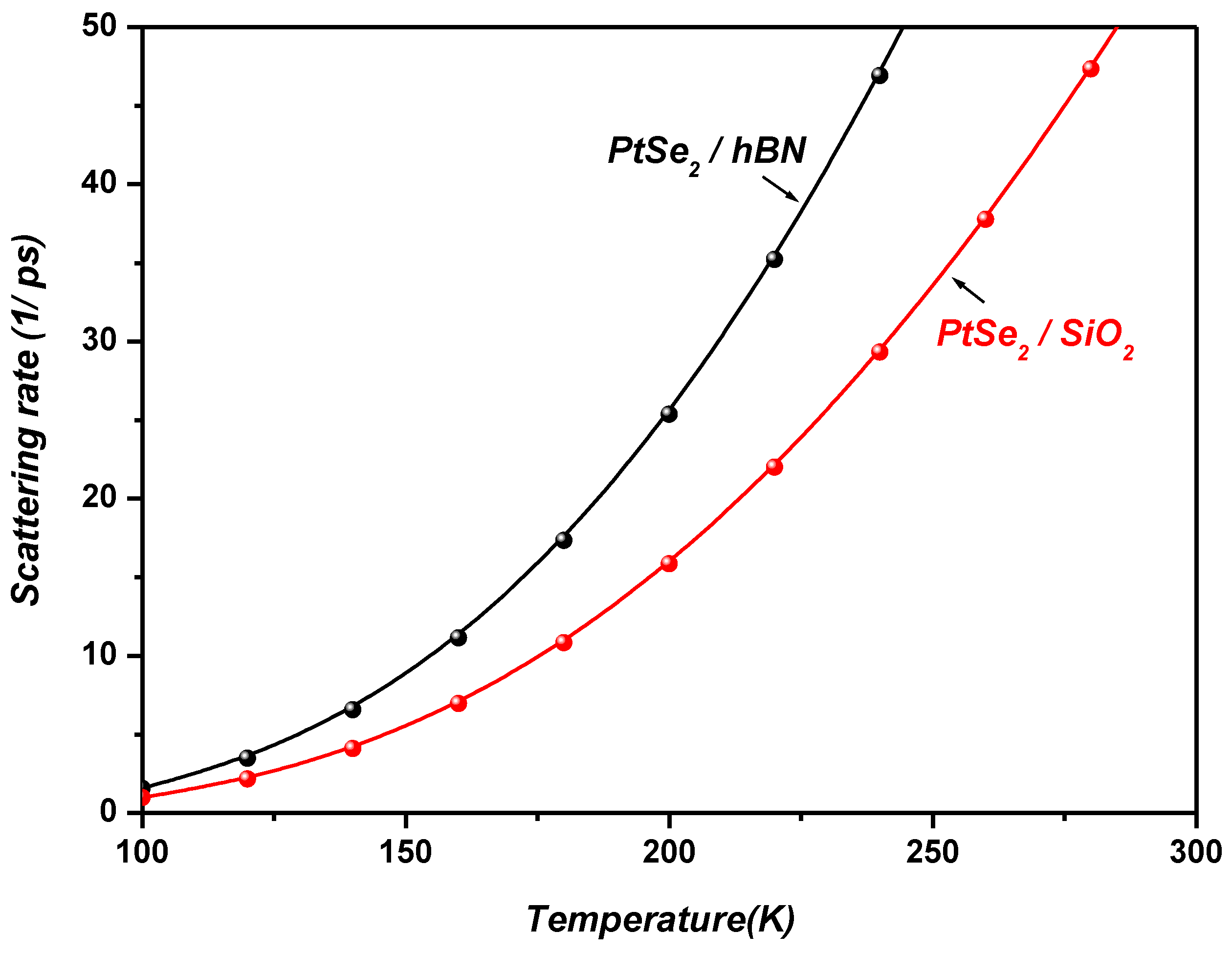

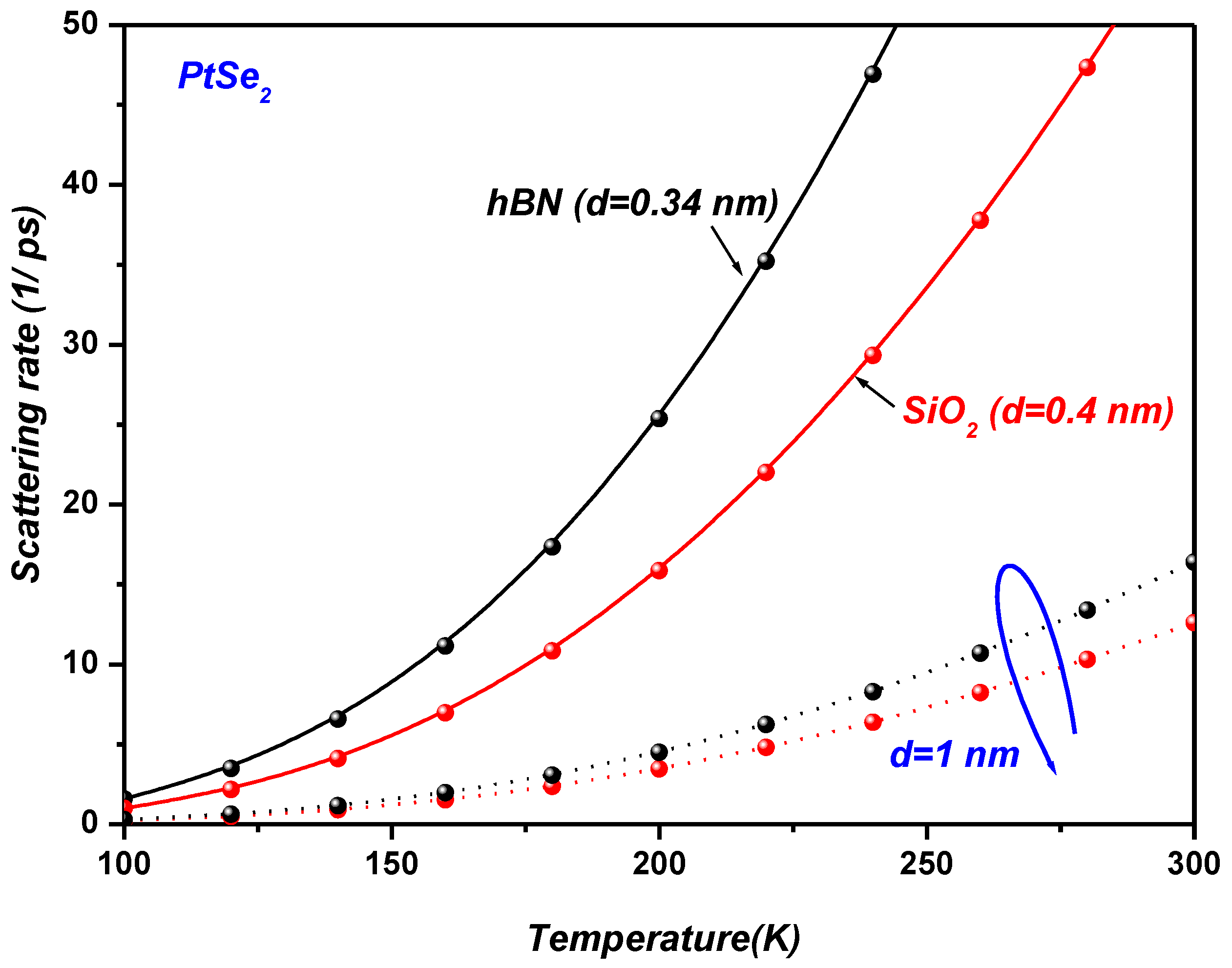

Figure 7 illustrates the temperature dependence of the surface optical (SO) phonon scattering rate in monolayer PtSe

2 on SiO

2 and hBN polar substrates. It is clearly observed that at temperatures above room temperature, the SO phonon scattering rate increases with temperature, reflecting the enhanced phonon population. In contrast, at low temperatures, the scattering rate remains negligible due to the weak phonon occupation. Furthermore,

Figure 7 indicates that the scattering rate is consistently higher for the hBN substrate compared to SiO

2 across the entire temperature range. This behavior is attributed to the higher LO phonon energy and stronger polarization field associated with the hBN substrate, which enhance electron–phonon interactions at the interface.

Figure 7 further reveals that the surface optical (SO) phonon scattering rate in monolayer PtSe

2 is strongly influenced by the dielectric properties of the underlying polar substrate. Specifically, the scattering rate follows the relation:

This behavior arises from the larger dielectric mismatch and stronger polarization fields at the PtSe2/hBN interface, which enhance the Fröhlich-type electron–phonon coupling, thereby increasing the scattering rate.

Ultimately, by selecting an appropriate polar dielectric substrate, it is possible to optimize and enhance the surface optical (SO) phonon scattering rate in monolayer PtSe2 and PtS2, thereby tuning their polaronic and transport properties.

We now explore how the van der Waals (vdW) separation affects the surface optical phonon (SOP) scattering in monolayer PtS

2 and PtSe

2 with polar substrates, specifically SiO

2 and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) (see

Figure 8). At typical interface distances (d = 0.4 nm for SiO

2, d = 0.34 nm for hBN as reported in

Table 2), strong electron–phonon coupling is observed due to the proximity of the 2D layer to the SOP field. However, as the vdW distance increases to d = 1.0 nm, the SOP-induced scattering rate drops significantly—by more than an order of magnitude—due to the exponential decay of the electric field away from the substrate. This reduction leads to enhanced carrier mobility and improved optoelectronic properties. These results underscore the critical importance of interfacial spacing as a tunable parameter for engineering electron–phonon interactions in two-dimensional materials, with direct implications for next-generation optoelectronic device design.

A thorough understanding of electron–surface optical phonon (SOP) interactions in monolayer PtS

2 and PtSe

2 necessitates close attention to the dielectric environment—especially when these materials are supported on polar substrates such as SiO

2 and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN). The substrate’s dielectric response plays a dual role: it screens Coulomb interactions, thereby modulating excitonic binding energies and carrier mobility, while simultaneously introducing remote surface optical phonon modes that open additional scattering channels. Gopalan et al. [

56], through first-principles transport calculations, highlighted this trade-off by showing that although high-κ dielectrics can suppress intrinsic phonon scattering and enhance mobility, the presence of remote interfacial phonons from polar substrates can counteract these gains by reintroducing scattering pathways.

This interplay becomes particularly critical in PtS

2 and PtSe

2 due to their pronounced polarizability and quasi-flat electronic bands, which amplify sensitivity to substrate-induced perturbations. Experimental observations further corroborate this susceptibility. Chow et al. [

57] reported the emergence of symmetry-forbidden Raman modes in TMDC monolayers interfaced with hBN, attributing them to strong exciton–phonon coupling at the van der Waals interface. Similarly, Kizel et al. [

58] demonstrated that asymmetric dielectric environments in rhombohedral MoS

2 heterostructures induce polarization-dependent shifts in photoluminescence, resulting from exciton–trion rebalancing governed by Fermi level tuning—an effect potentially mirrored in Pt-based dichalcogenides.

These findings align with Giustino’s comprehensive theoretical framework [

59], which emphasizes that both short- and long-range dielectric screening profoundly modulate electron–phonon interactions in low-dimensional materials. Complementary insights are provided by Stier et al. [

60], who showed that excitonic properties in WSe

2 can be finely tuned via substrate engineering, with significant impacts on exciton binding energies and optical spectra.

Recent studies further underscore the importance of interfacial dielectric design. Adeniran and Liu [

61] investigated the spatially resolved screening profile at TMDC/hBN interfaces, revealing that screening strength evolves markedly from monolayer to bulk due to local-field effects. Their work underscores the role of interface-specific dielectric engineering in optimizing transport and optical response. Knobloch et al. [

62] further confirmed that hBN, thanks to its atomically flat surface and low impurity density, outperforms SiO

2 in enabling high-mobility, low-scattering device platforms—an essential requirement for PtS

2 and PtSe

2 integration. Lastly, Wang et al. [

63] demonstrated that substrate selection (e.g., SiO

2 vs. hBN) critically impacts carrier polarity and transport efficiency in 2D materials, reinforcing the idea that substrate-driven electron–phonon coupling is a tunable and decisive factor in device performance.

Altogether, these theoretical and experimental advances converge to highlight the critical role of dielectric engineering in governing SOP-mediated processes in PtS2 and PtSe2 monolayers. Substrate choice, especially when involving polar materials like SiO2 and hBN, emerges as a decisive factor for tailoring excitonic phenomena, phonon-assisted scattering, and overall optoelectronic performance in 2D heterostructures.

Furthermore, the interaction with surface optical phonon (SOP) modes leads to the formation of polaronic states, which play a critical role in the energy relaxation processes within PtS2 and PtSe2 monolayers. By adjusting the strength of this coupling—achievable through careful selection of the supporting polar substrate—it becomes possible to influence the dynamics of phonon-assisted hot carrier relaxation. This level of control is particularly advantageous for improving the performance of devices such as photodetectors and solar cells, where efficient energy dissipation and rapid carrier response are essential.