Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Emissions Assessment Methodology

2.2. Comparable Cadmium Reduction Processes

2.2.1. Electroslag Reduction Method: 700 °C, KCl-NaCl Slag, Carbon, No Cd Evaporation

- Mass of CdO: 128 g (1 mol)

- Mass of carbon (C): 500 g (50 mol)

- Reaction:

2.2.2. Pyrometallurgy (Distillation)

- heat treatment of cadmium oxide in an open furnace, followed by condensation to produce cadmium oxide powder;

- distillation in a closed furnace atmosphere, yielding metallic cadmium powder and an Fe–Ni alloy;

- chlorination of batteries under a chlorine gas atmosphere or in hydrochloric acid at 960 °C to form cadmium chloride.

2.2.3. Hydrometallurgy

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship, and SMEs. (2023). Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023: Final report (M. Grohol & C. Veeh, Assistants). Publications Office of the European Union. [CrossRef]

- Daosan, M.; Novoderezhkin, V.V.; Tomashevskij, F.F. Production of Electrolytic Accumulators (Прoизвoдствo Электрических Аккумулятoрoв in Russian); Visshaja Shkola: Moscow, Russia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, W.; El-Shaer, A.; Abdelfatah, M. Phase transition of Cd(OH)2 and physical properties of CdO microstructures prepared by precipitation method for optoelectronic applications. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 956, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, R.N.; Katz, D.L. V Liquid-Metals Handbook; NAVEXOS P; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Y.Y.; Yin, L.T.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, C.T.; Tsai, C.H.; Kuo, Y.M. Recycling of spent nickel–cadmium battery using a thermal separation process. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumbergs, E.; Maiorov, M.; Bogachov, A.; Platacis, E.; Ivanov, S.; Gavrilovs, P.; Pankratov, V. (2025). A Green Electroslag Technology for Cadmium Recovery from Spent Ni-CD Batteries Under Protective Flux with Electromagnetic Stirring by Electrovortex Flows. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Waste Statistics-Recycling of Batteries and Accumulators. Eurostat 2021, 1–12. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics_-_recycling_of_batteries_and_accumulators#Recycling_of_batteries_and_accumulators (accessed on 31 july 2025).

- Espinosa, D.C.R.; Mansur, M.B. Recycling batteries. In Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, D.C.R.; Tenório, J.A.S. Fundamental aspects of recycling of nickel–cadmium batteries through vacuum distillation. J. Power Sources 2004, 135, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, D.C.R.; Tenório, J.A.S. Recycling of nickel–Cadmium batteries using coal as reducing agent. J. Power Sources 2006, 157, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, J.; Xu, Z. Characterization and recycling of cadmium from waste nickel–cadmium batteries. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 2292–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, D.C.R.; Bernardes, A.M.; Tenório, J.A.S. An overview on the current processes for the recycling of batteries. J. Power Sources 2004, 135, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Fray, D.J. Recycling of cadmium from domestic, sealed NiCd battery waste by use of chlorination. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 1999, 108, C153–C158. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes, A.M.; Espinosa, D.C.R.; Tenório, J.A.S. Recycling of batteries: A review of current processes and technologies. J. Power Sources 2004, 130, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anulf, T. SAB-NIFE recycling concept for nickel-cadmium batteries—An industrialised and environmentally safe process. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Cadmium Conference, Capri, Italy, 10–12 April 1990; pp. 161–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hanewald, R.H.; Schweyer, L.; Hoffman, M.D. High temperature recovery and reuse of specialty steel pickling materials and refractors at INMETCO. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electric Furnace, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–7 November 1991; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- INMETCO. High Temperature Metal Recovery Process; INMETCO: Ellwood City, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Liotta, J.J.; Onuska, J.C.; Hanewald, R.H. Nickel-Cadmium Battery Recycling through the INMETCO High Temperature Metals Recovery Process. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Battery Conference on Applications and Advances, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–13 January 1995; p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- Blumbergs, E.; Serga, V.; Platacis, E.; Maiorov, M.; Shishkin, A. Cadmium Recovery from Spent Ni-Cd Batteries: A Brief Review. Metals 2021, 11, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweers, M.E.; Onuska, J.C.; Hanewald, R.H. A pyrometallurgical process for recycling cadmium-containing batteries. In Proceedings of the HMC-South ’92 Exhibitor Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–28 February 1992; Hazardous Materials Control Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 333–335. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, C.A.; Margarido, F. Recycling of spent Ni-Cd batteries by physical-chemical processing. In Proceedings of the 2006 TMS Fall Extraction and Processing Division: Sohn International Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 27–31 August 2006; Volume 5, pp. 305–312. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, L.; Frank, J.; Elwert, T. Industrial Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries—A Critical Review of Metallurgical Process Routes. Metals 2020, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, F.; Tedjar, F.; Amouzegar, K.; Houlachi, G.; Bouchard, P.; Demopoulos, G.P.; Zaghib, K. Progress and Status of Hydrometallurgical and Direct Recycling of Li-Ion Batteries and Beyond. Materials 2020, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Zulkapli, N.S.; Kamyab, H.; Taib, S.M.; Din, M.F.B.M.; Majid, Z.A.; Chaiprapat, S.; Kenzo, I.; Ichikawa, Y.; Nasrullah, M.; et al. Current technologies for recovery of metals from industrial wastes: An overview. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E.; Nikiel, M. Hydrometallurgical recovery of cadmium and nickel from spent Ni–Cd batteries. Hydrometallurgy 2007, 89, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erkel, J. Recovery of Cd and Ni from Batteries. U.S. Patent 5,407,463, 18 April 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa, N.S.; Gharami, K.; Kumar, M. Leaching kinetics of spent nickel–cadmium battery in sulphuric acid. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 165, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindermann, W.; Dombrowsky, C.H.; Sewing, D.; Muller, M.; Engel, S.; Joppien, R. The Batenus process for recycling battery waste. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Impurity Control and Disposal in Hydrometallurgical Processes, Toronto, ON, Canada, 21–24 August 1994; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tanong, K.; Coudert, L.; Mercier, G.; Blais, J.-F. Recovery of metals from a mixture of various spent batteries by a hydrometallurgical process. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 181, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza Khayati, G.; Dalvand, H.; Darezereshki, E.; Irannejad, A. A facile method to synthesis of CdO nanoparticles from spent Ni–Cd batteries. Mater. Lett. 2014, 115, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanong, K.; Tran, L.-H.; Mercier, G.; Blais, J.-F. Recovery of Zn (II), Mn (II), Cd (II) and Ni (II) from the unsorted spent batteries using solvent extraction, electrodeposition and precipitation methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.R.; Priya, D.N.; Park, K.H. Separation and recovery of cadmium(II), cobalt(II) and nickel(II) from sulphate leach liquors of spent Ni–Cd batteries using phosphorus based extractants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2006, 50, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.A.; Margarido, F. Nickel–Cadmium batteries: Effect of electrode phase composition on acid leaching process. Environ. Technol. 2012, 33, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Afonso, J.C.; Bourdot Dutra, A.J. Hydrometallurgical route to recover nickel, cobalt and cadmium from spent Ni–Cd batteries. J. Power Sources 2012, 220, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefi, M.; Maroufi, S.; Mayyas, M.; Sahajwalla, V. Recycling of Ni-Cd batteries by selective isolation and hydrothermal synthesis of porous NiO nanocuboid. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4671–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Mahandra, H.; Gupta, B. Recovery of zinc and cadmium from spent batteries using Cyphos IL 102 via solvent extraction route and synthesis of Zn and Cd oxide nanoparticles. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.R.; Priya, D.N. Chloride leaching and solvent extraction of cadmium, cobalt and nickel from spent nickel–Cadmium, batteries using Cyanex 923 and 272. J. Power Sources 2006, 161, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Thi, L.D.; Qureshi, T.I. Recycling of NiCd batteries by hydrometallurgical process on small scale. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 2011, 33, 853–857. [Google Scholar]

- Thinkstep GaBi. Hydrogen peroxide production, EU-28 mix. Available online: https://gabi.sphera.com (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Ecoinvent v3.8. Sulfuric acid production dataset. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org (accessed on 31 July 2025).

| 2CdO | C | 2Cd | CO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n,mol | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ,kJ/mol | -259 | 0 | 0 | 393,51 |

| Cd(OH)2 | CdO | Н2О | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n,mol | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ,kJ/mol | -563 | -259 | -242 |

| Electricity source | Emission factor (kg CO2/kWh) |

Source |

|---|---|---|

| Latvia (Nowtricity) | 0.17 |

https://www.nowtricity.com/country/latvia/ Average 2024 year |

| Germany (Climatiq) | 0.33 | Climatiq Germany |

| Germany (UBA 2023) | 0.38 | UBA Germany |

| France (LCA) | 0.004 | https://www.sfen.org/rgn/les-emissions-carbone-du-nucleaire-francais-37g-de-co2-le-kwh/ |

| Nuclear (LCA ADEME) | 0.006 | ADEME France |

| Solar (UNECE) EU28 | 0.011-0.037 | UNECE LCA 2021 |

| Natural gas, EU28 | 0.43 | UNECE LCA 2021 |

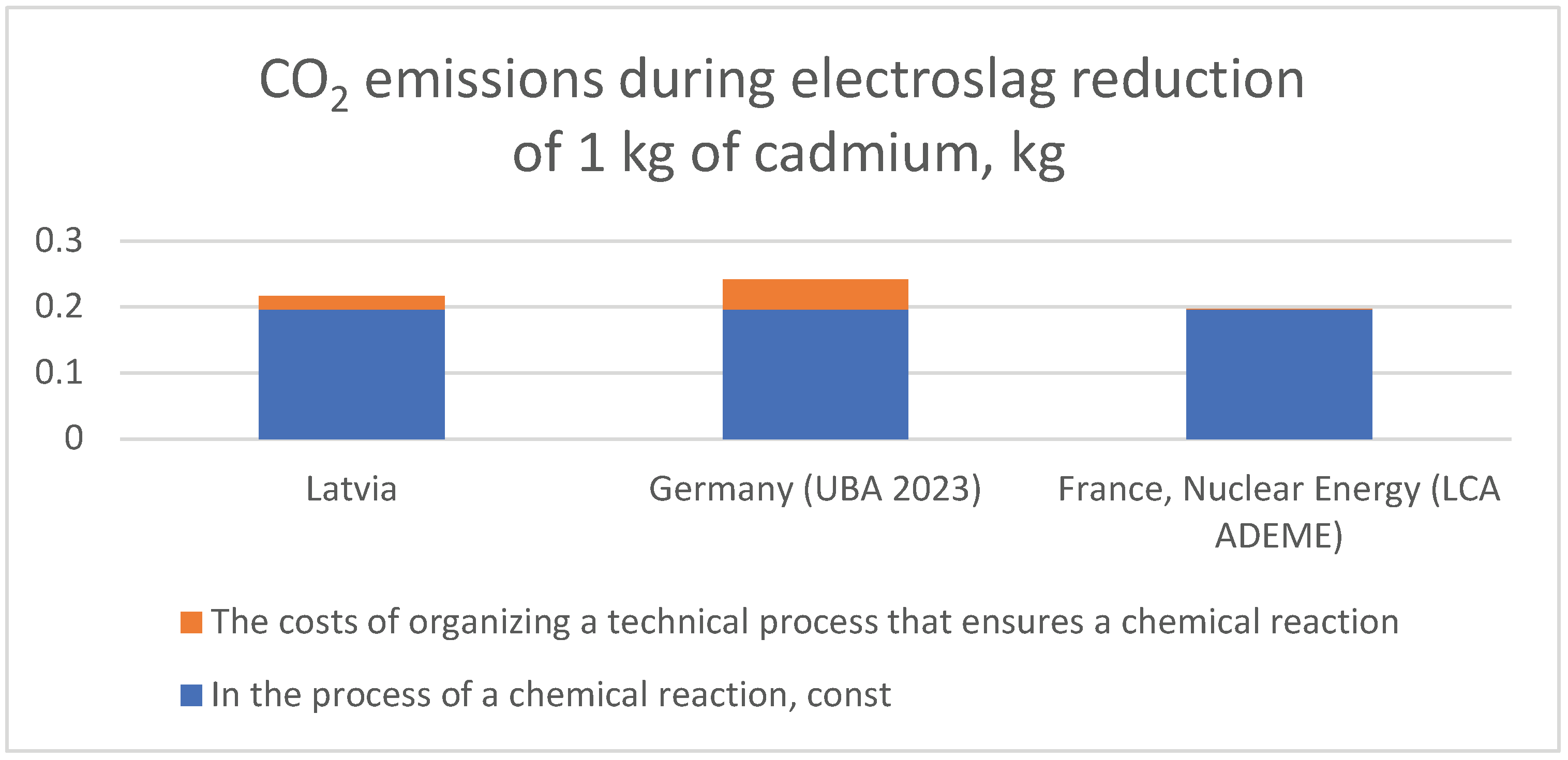

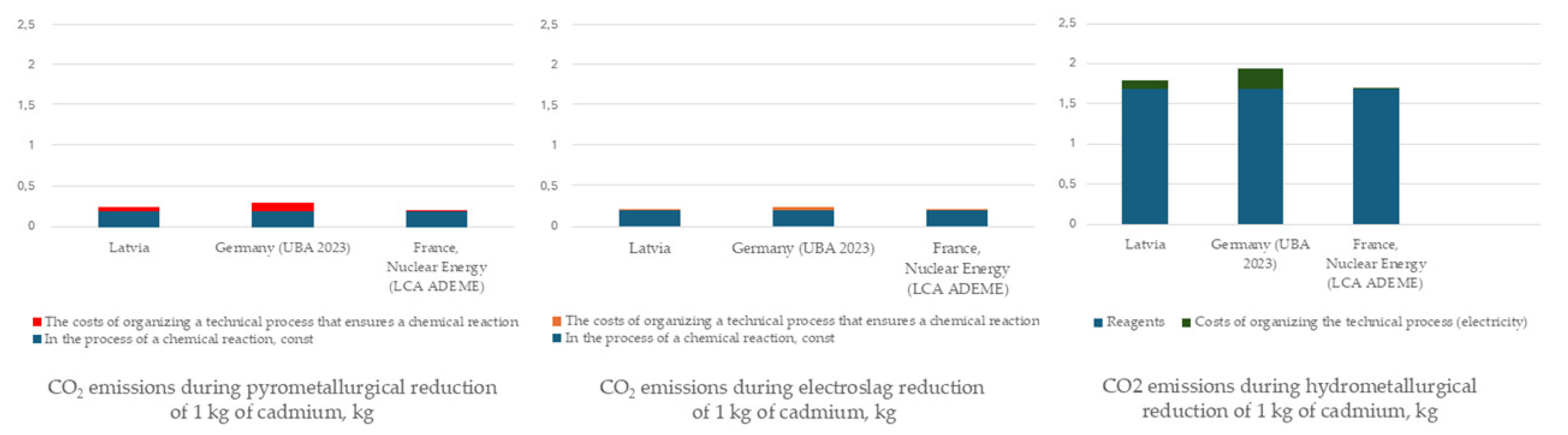

| Country | CO2 emissions for the reduction of 1 kg of cadmium with carbon using the electroslag reduction method, kg | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| During a chemical reaction, const | The costs of organizing a technical process that ensures a chemical reaction, variable | Total | |

| Latvia | 0,1958 kg | 0,17 kg CO2/kW h * 0,12 kW h = 0,0204 kg | 0,2162 kg |

| Germany (UBA 2023) | 0,1958 kg | 0,38 kg CO2/kW h * 0,12 kW h = 0,0456 kg | 0,2414 kg |

| France, Nuclear Energy (LCA ADEME) | 0,1958 kg | 0,004 kg CO2/kW h * 0,12 kW h = 0,0005 kg | 0,1963 kg |

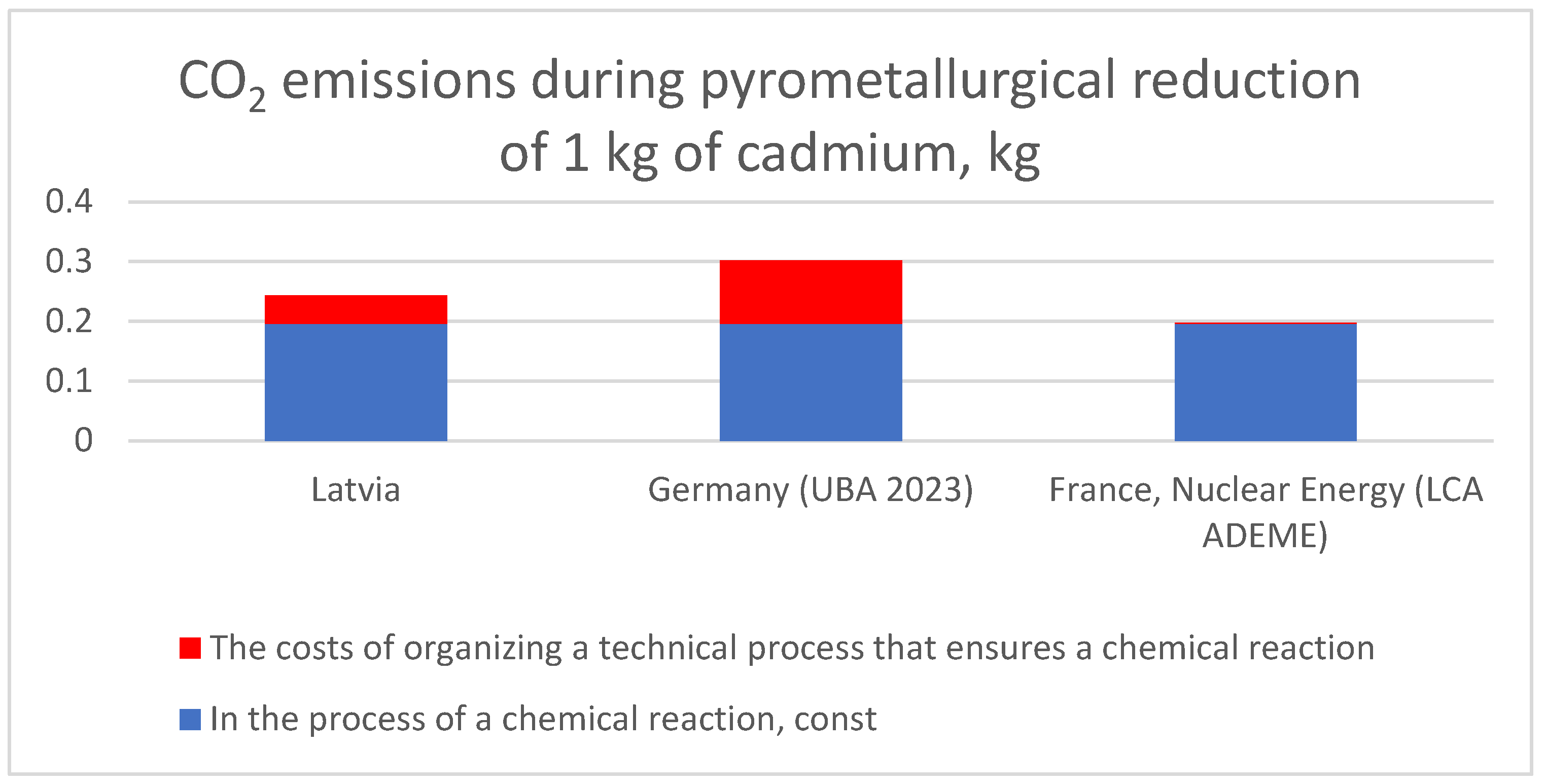

| Country | CO2 emissions during pyrometallurgical reduction of 1 kg of cadmium, kg | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| In the process of a chemical reaction, const | The costs of organizing a technical process that ensures a chemical reaction | Total | |

| Latvia | 0,1958 kg | 0,17 kg CO2/ kW h * 0,28 kW h = 0,0476 kg | 0,2434 kg |

| Germany (UBA 2023) | 0,1958 kg | 0,38 kg CO2/ kW h * 0,28 kW h = 0,1064 kg | 0,3022 kg |

| France, Nuclear Energy (LCA ADEME) | 0,1958 kg | 0,004 kg CO2/ kW h * 0,28 kW h = 0,0011 kg | 0,1969 kg |

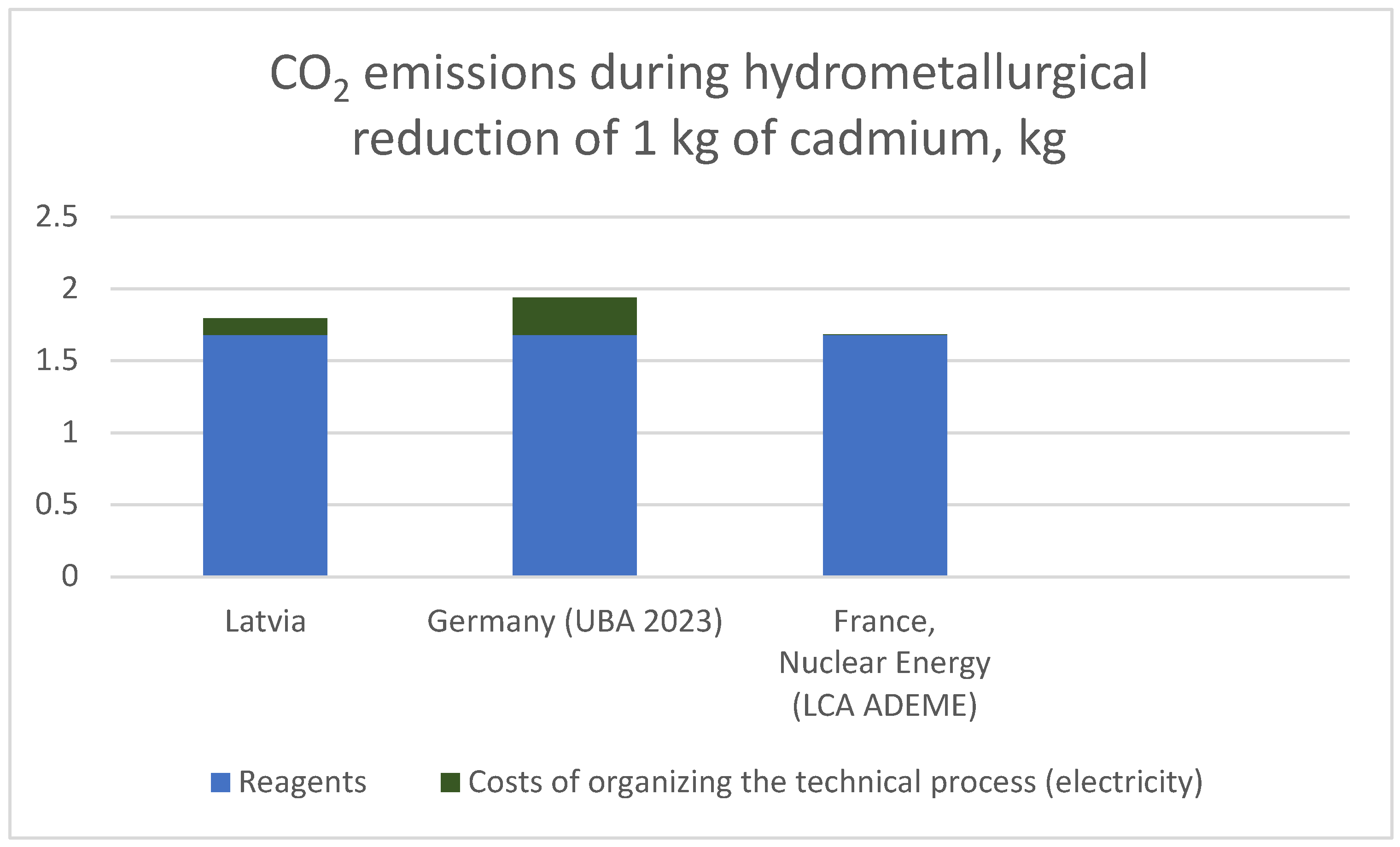

| Reagent | Mass (kg) | Specific emissions, kg CO2/kg | CO2, kg |

| H2SO4 | 0.6058 | 0.66 | 0.40 |

| H2O2 | 0.412 | 1.60 | 0.66 |

| TBP + ShellSol R | ~0.20 | 2.50 | 0.50 |

| Ion exchange resin | ~0.05 | 2.40 | 0.12 |

| Total | — | — | 1.68 |

| Country | Specific emissions, kg CO2/kW h | Total emissions from 0.68 kW h |

| Latvia | 0.17 | 0.116 kg CO2 |

| Germany | 0.38 | 0.258 kg CO2 |

| France | 0.004 | 0.0027 kg CO2 |

| Emission source | Latvia | Germany | France |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent | 1.68 | 1.68 | 1.68 |

| Electricity | 0.116 | 0.258 | 0.0027 |

| TOTAL (kg CO2) | 1.80 | 1.94 | 1.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).