Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Novelty

- The focused approach on the interplay between the three domains, to achieve specific outcomes (optimized mineral recovery and a resilient CE, is a central novel aspect.

- The paper provides a comprehensive analysis by examining the environmental, economic, and technological aspects of E-waste recovery. It also investigates innovative strategies for improving material recovery and sustainability, considering regulatory frameworks, technological innovations, and economic incentives. This multi-faceted approach to understanding the challenges and opportunities in transitioning to a CE for electronics, with a specific focus on mineral recovery, adds to its novelty.

- The manuscript highlights the significant gap between E-waste generation and material recovery efforts and seeks to propose pathways for sustainable resource management by addressing current inefficiencies in E-waste recycling systems. This focus on identifying and proposing solutions to existing gaps contributes to the novelty.

- The study aims to contribute to the broader discourse on enhancing sustainability and CE principles in mineral resource utilization. This ambition to not only analyze E-waste but also to link it to wider sustainability and CE principles in the context of mineral resources suggests a novel contribution beyond a narrow technical analysis.

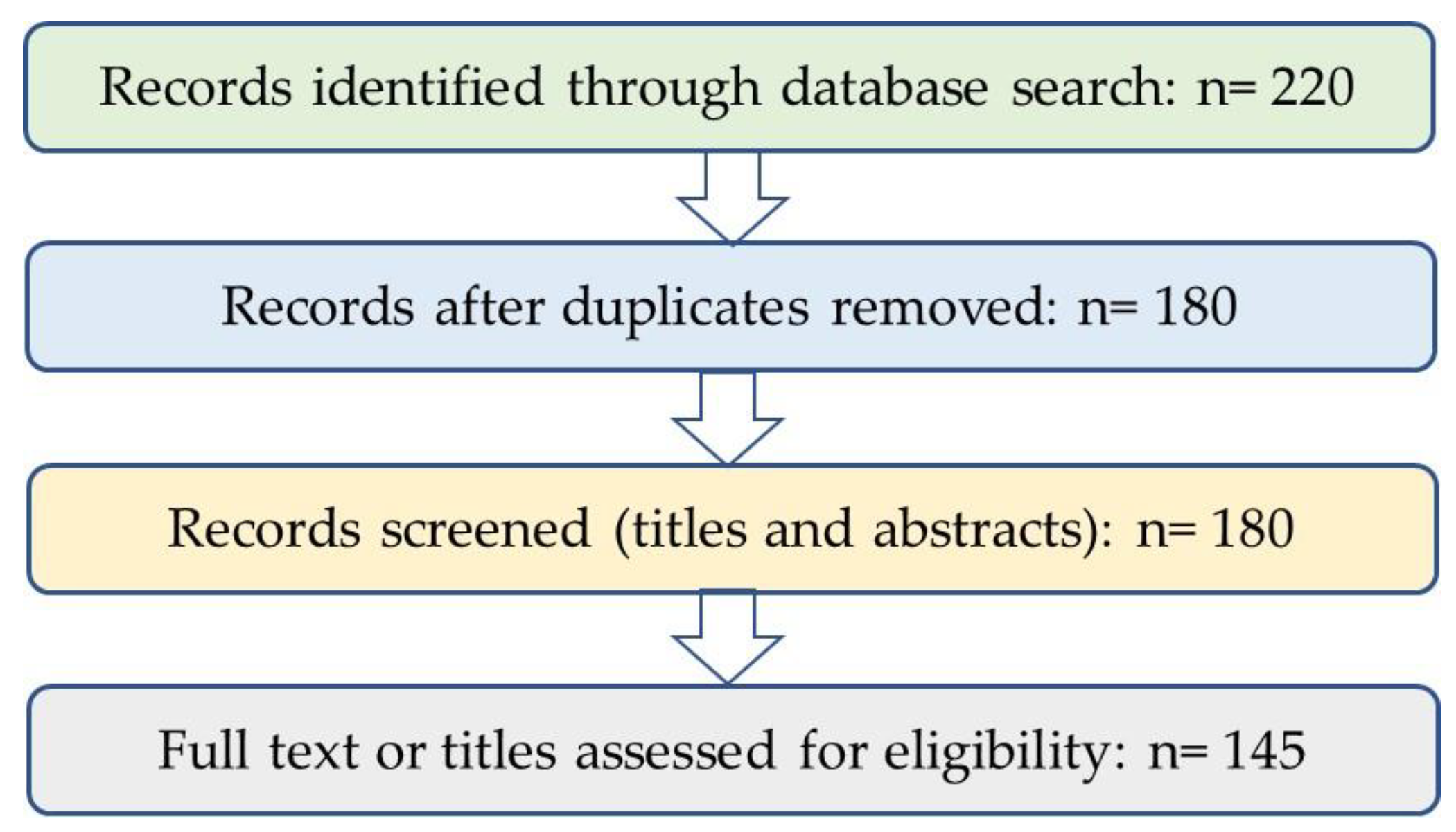

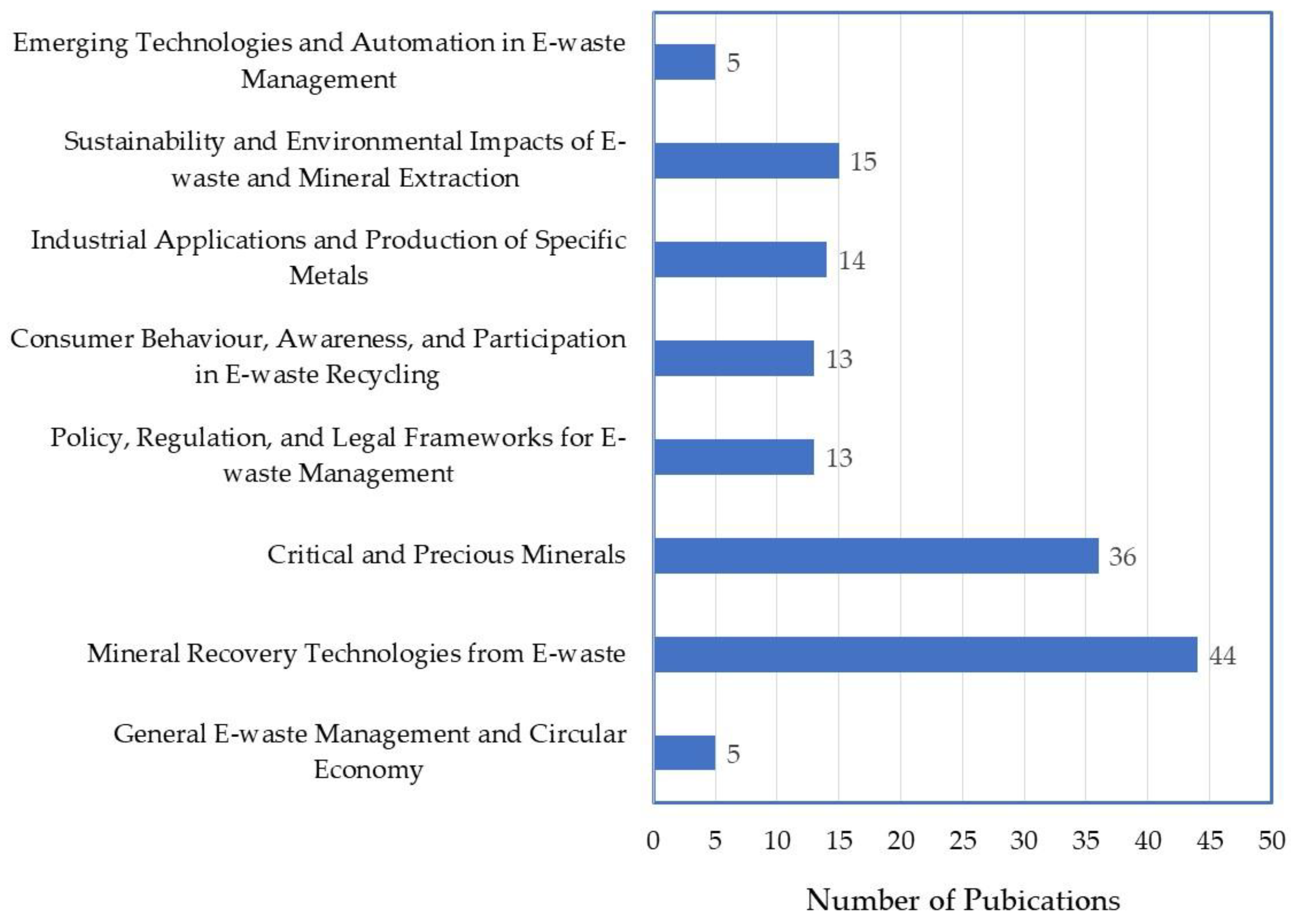

3. Methodology and Data Analysis

3.1. Identification of Sources

3.2. Screening and Eligibility Analysis

3.3. Data Analysis and Synthesis of Results

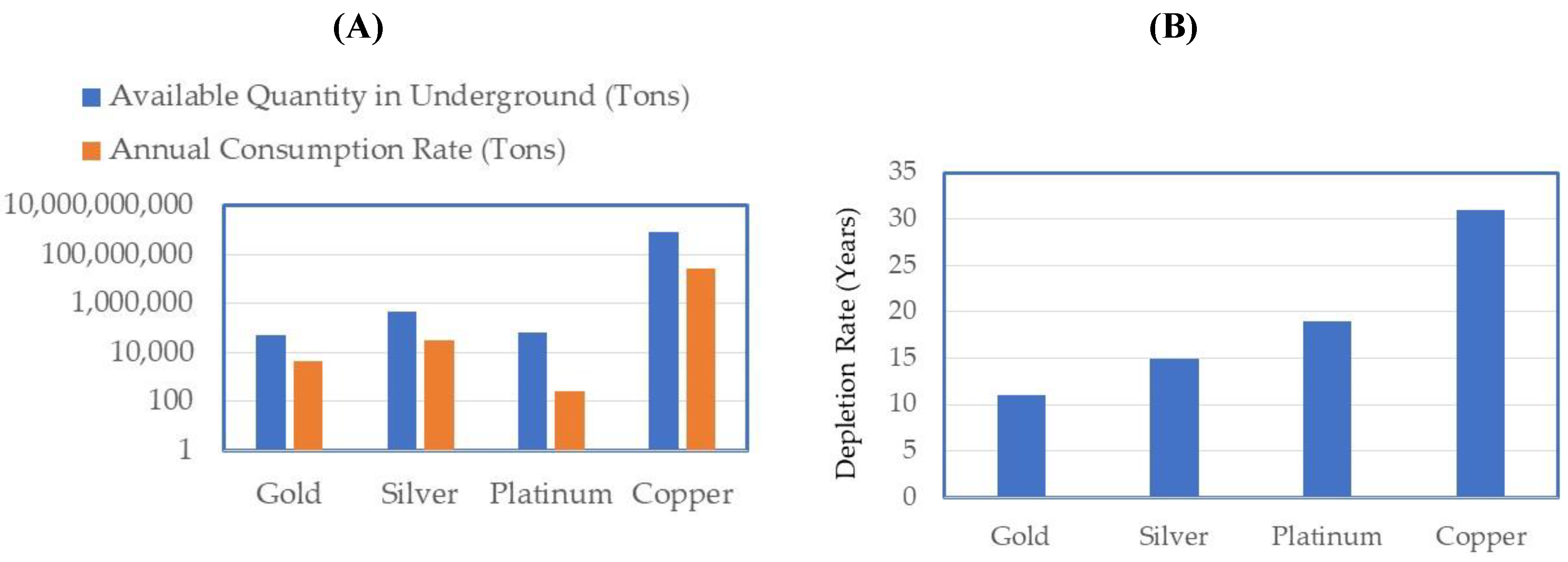

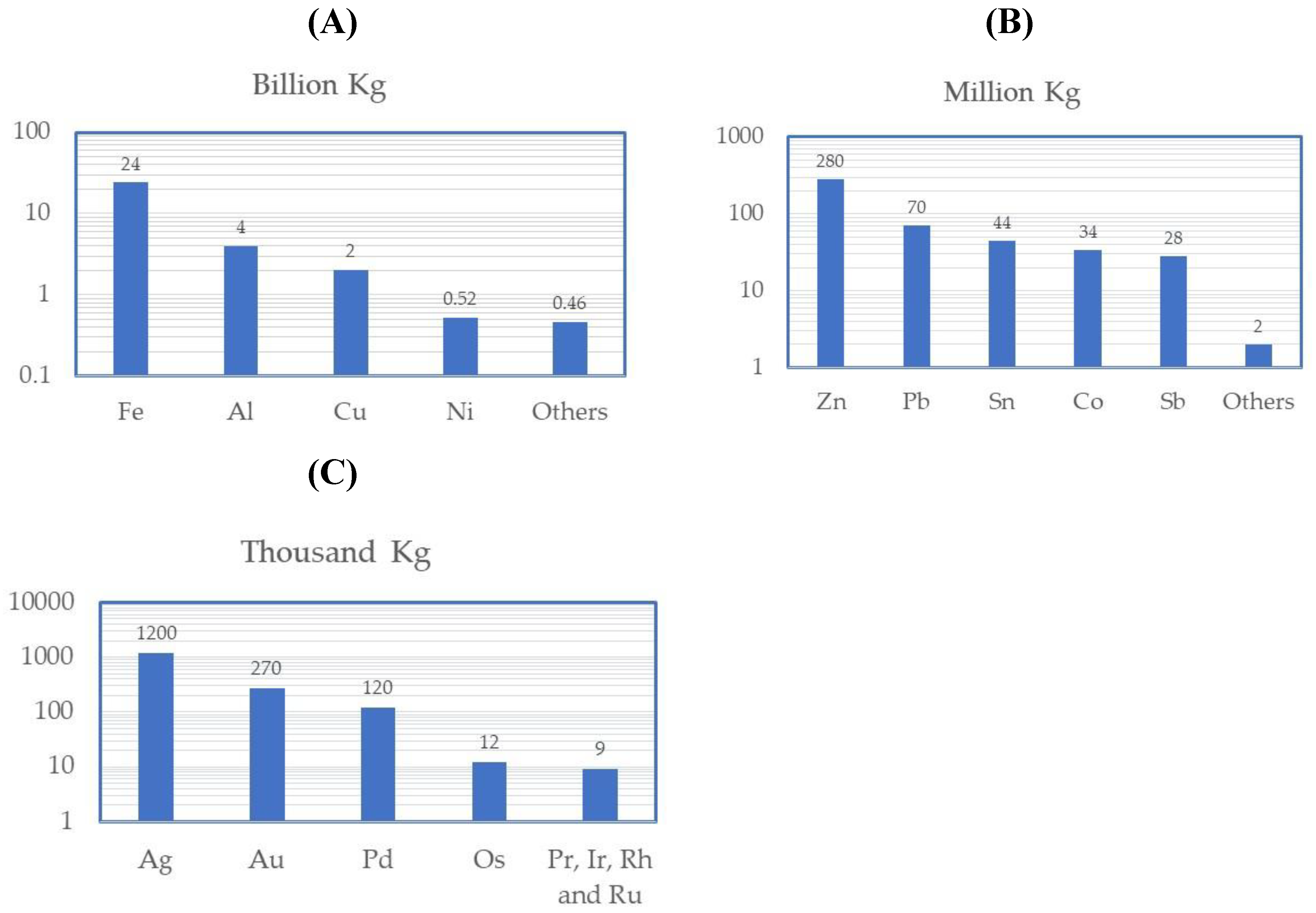

4. Critical and Precious Minerals

4.1. Industrial Significance, Major Producers, and Potential Environmental Impact from Primary Resource Extraction Processes

4.2. E-Waste as a Sustainable Resource for Critical and Precious Minerals

4.2.1. Secondary Resource Potentials

4.2.2. Environmental Benefits

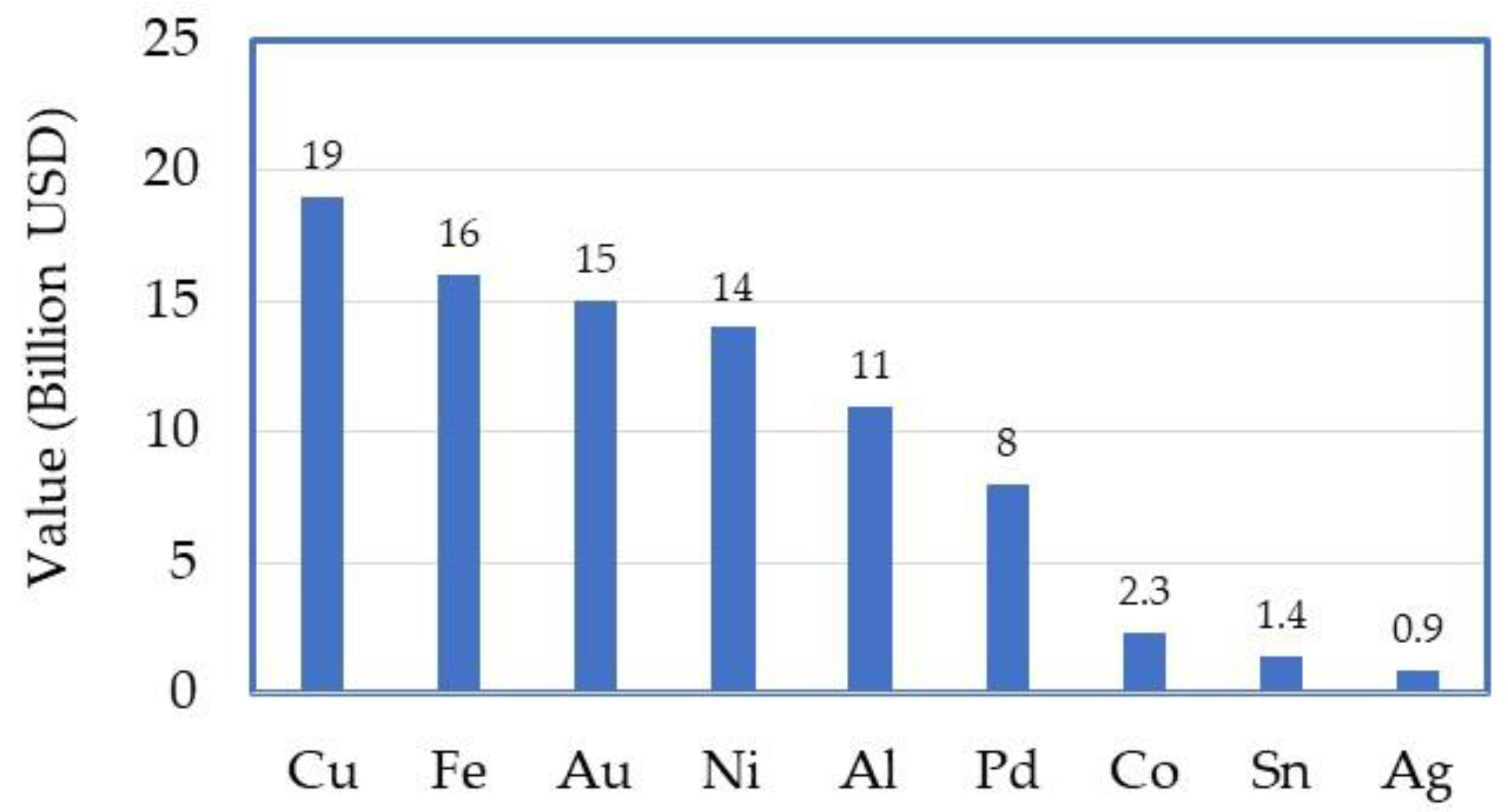

4.2.3. Economic Benefits

5. Technologies for Mineral Recovery from E-waste

5.1. Physical and Mechanical Separation

5.2. Pyrometallurgical Processes

5.3. Hydrometallurgical Processes

5.4. Bio-Metallurgy

5.5. Electrochemical Processes

5.6. Advantages/Disadvantages and Efficiency of Mineral Recovery Processes from E-Waste

- Gold (Au) and Silver (Ag): They are among the most valuable metals found in E-waste. They are best recovered through hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical methods, both of which are highly effective in extracting these precious metals. Additionally, electrochemical processes can also be used to recover Au and Ag with high purity, ensuring that these valuable materials are efficiently separated and refined.

- Copper (Cu): It is commonly found in E-waste, particularly in circuit boards and wiring. It can be efficiently extracted using hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy, and electrochemical methods. These processes ensure high recovery rates of Cu, which is a key material in electronics due to its excellent conductivity and recyclability.

- Rare Earth Elements (REEs): The recovery of REEs, such as neodymium and dysprosium, is a more challenging task, as traditional recovery methods often struggle to extract these elements efficiently. While bio-metallurgy (using microorganisms to extract metals) shows promise for REE recovery, it requires further research and optimization to enhance its effectiveness and scalability.

- Platinum Group Metals (PGMs): PGMs, including platinum, palladium, and rhodium, are highly valuable but are typically found in smaller quantities in E-waste. The most effective recovery methods for PGMs are hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy, which allow for the extraction of these metals with high efficiency.

- Ferrous Metals (Fe, Ni, Co): They are best recovered using physical separation methods, such as magnetic separation, or through pyrometallurgical techniques. These methods effectively separate ferrous metals from other materials, ensuring that they can be recycled and reused.

- Aluminum (Al): It is widely used in electronics, particularly in housings and casings. The most efficient recovery methods for aluminum include physical separation techniques, such as eddy current separation, or through pyrometallurgy. These methods are effective in extracting aluminum with minimal loss and ensuring that it can be reused in new products.

5.7. Challenges and Barriers of Mineral Recovery Processes from E-Waste

- Technical challenges related to complexity of material composition and the requirements of advanced recovery methods are: (a) The heterogeneous composition of E-waste and the miniaturization of components make the recovery of critical and precious minerals highly complex. Devices often contain multilayered structures, composite materials, and intricate alloys that are difficult to dismantle and separate efficiently; and (b) Techniques like hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy, and bioleaching are needed to extract valuable metals, each with their own technological limitations and process complexities.

- Environmental challenges concerning toxicity byproducts and chemical pollution, air pollution from high-temperature processes, and secondary waste stream management are (a) Hydrometallurgical processes use acids and cyanide-based solutions, generating hazardous liquid waste that risks soil and water contamination if mismanaged; (b) Pyrometallurgical techniques release toxic gases such as dioxins, sulfur dioxide, and heavy metal vapors, contributing to air pollution and long-term ecological damage, and (c) Processes generate residuals like slags, sludges, and spent acids that require careful disposal or treatment. Poor management can lead to heavy metal leaching into ecosystems.

- Occupational health and safety challenges involving exposure to hazardous substances, and health risks are: (a) Workers handling E-waste are at risk from toxic elements such as lead, mercury, arsenic, and brominated flame retardants, and (b) Improper handling can result in respiratory diseases, neurological disorders, and cancer. Ensuring adequate protection and proper handling protocols is critical for worker safety.

- Energy and climate impact in view of high energy consumption, and trade-offs of low-energy alternatives are: (a) Pyrometallurgical processes are energy-intensive, significantly contributing to GHG emissions and climate change, and (b) While bioleaching and electrochemical recovery are more energy-efficient, they are often slower and less effective in extracting metals, limiting industrial viability.

- Waste Management challenges relating to residual waste disposal, and lack of sustainable strategies are: (a) The byproducts of mineral recovery often require further treatment to prevent environmental contamination, and (b) Many current waste treatment methods are insufficiently sustainable, increasing the ecological burden of recycling operations.

- Efficiency and scalability challenges concerning low selectivity and purity, reliance on primary mining, scalability of emerging technologies, and balancing recovery and sustainability are: (a) Existing recovery methods often yield low-purity metals and suffer from inefficient selective separation, requiring additional refining, (b) Inefficiencies in recycling contribute to continued dependence on virgin resource extraction, (c) Biological techniques like bioleaching face hurdles such as slow reaction times, inconsistent yields, and limited scalability, posing challenges for industrial-scale adoption, and (d) Achieving high recovery rates while minimizing environmental harm and maintaining cost-effectiveness remains a persistent research and development hurdle.

- Advanced material separation technologies: Implementing innovative separation techniques such as hydrometallurgical and bioleaching processes can enhance the recovery of valuable metals and rare earth elements from E-waste. Additionally, the use of AI-powered robotic sorting systems can improve material classification and reduce contamination.

- Robust collection and reverse logistics networks: Establishing efficient take-back schemes and drop-off points for consumers, combined with digital tracking systems, can ensure higher recovery rates and minimize improper disposal.

- Economic incentives and policy measures: Governments and industry stakeholders should introduce financial incentives such as tax breaks, subsidies, and extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs to encourage manufacturers to design recyclable products and invest in CE initiatives.

- Industry collaboration and standardization: Strengthening partnerships among manufacturers, policymakers, and recyclers is crucial for developing unified standards for material recovery, ensuring consistency, and fostering innovation in recycling technologies.

6. Economics

6.1. Investment Costs and Capital Expenditures

6.2. Operational Costs and Ongoing Expenses

6.3. Market Volatility and Financial Returns

6.4. Comparative Cost Advantage of Primary Mining vs. Recycling

6.5. Balancing Costs and Sustainable Growth

7. Regulatory and Policy

8. Stakeholder Engagement

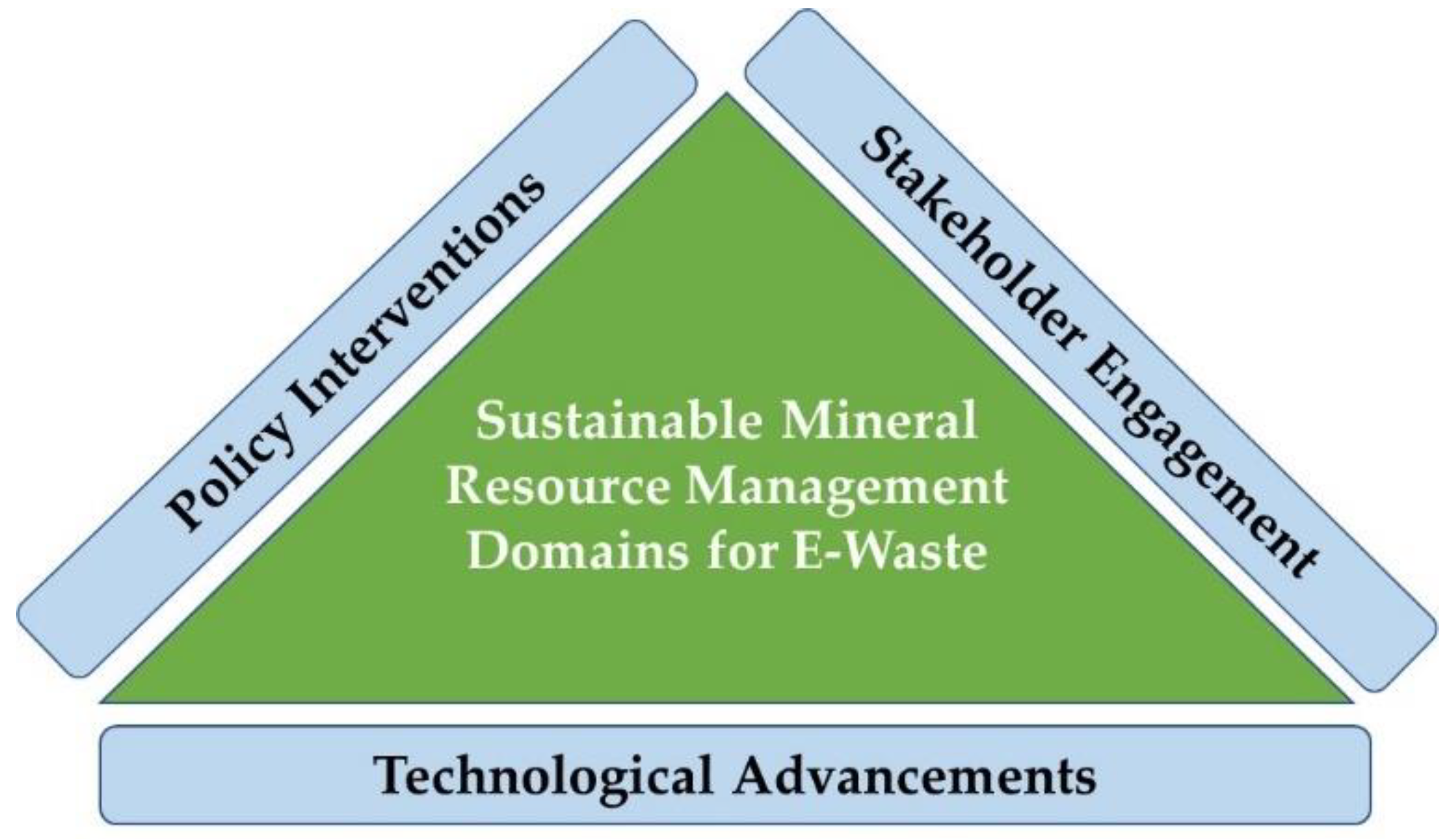

9. Synergistic Leverage for Sustainable E-waste Management

9.1. Technological Advancements

9.2. The Impact of Policy Interventions

9.3. The Crucial Role of Stakeholder Engagement

9.4. Proposed Implementation Roadmap

10. Conclusion and Future Outlook

- (1)

- Addressing under-researched areas: The review of publications highlighted that topics such as public engagement and the institutional and legal structures governing E-waste practices, and digital technologies and automation in E-waste management. Future research could focus on gaining a deeper understanding of the complex global flow of E-waste, including the dynamics of illegal exports and the environmental and social impacts in receiving countries. Investigating the geochemical aspects of metals in E-waste and their potential long-term environmental consequences would also be valuable. Furthermore, exploring the specific role of E-waste recycling in supporting the clean energy transition and the material requirements of renewable energy technologies warrants further investigation.

- (2)

- Optimizing existing recovery technologies: While various technologies for mineral recovery exist, there is room for improvement and optimization. Future research should focus on: (a) Enhancing the selectivity and efficiency of hydrometallurgical processes while minimizing the use of hazardous chemicals and improving wastewater treatment methods. Research into greener leaching agents and more efficient solvent extraction techniques is needed; (b) Reducing the energy consumption and air pollutant emissions of pyrometallurgical processes through innovative furnace designs and advanced emission control technologies; (c) Improving the efficiency and scalability of bio-metallurgical approaches to make them more viable for industrial applications. This includes optimizing microbial activity and developing cost-effective bioreactor designs; and (d) Further developing and integrating electrochemical processes with other methods to achieve high-purity metal recovery with minimal environmental impact and lower energy requirements. Investigating novel electrode materials and cell designs could be beneficial.

- (3)

- Advancing automation and digitalization: The integration of Industry 4.0 solutions holds significant potential for E-waste management. Future research could focus on: (a) Developing more sophisticated AI and machine learning algorithms for improved automated disassembly and sorting of complex electronic devices; (b) Exploring the use of digital twins to simulate and optimize entire E-waste recycling processes before physical implementation, thereby enhancing efficiency and reducing risks; (c) Investigating the application of blockchain technology for enhancing the traceability and transparency of the E-waste supply chain; and (d) Addressing the significant gap between E-waste generation and recycling requires better collection systems. Future research could explore: (i) Developing and evaluating the effectiveness of different take-back schemes and deposit-refund systems in various socio-economic contexts; (ii) Investigating the role of digital technologies and IoT in optimizing reverse logistics networks and improving collection rates; and (iii) Identifying and addressing the barriers to consumer participation in formal recycling programs through behavioral studies and targeted interventions.

- (4)

- Policy and economic frameworks: Research into effective policy interventions and economic incentives is crucial for driving the CE for electronics. This includes: (a) Analyzing the impact and effectiveness of different EPR models and identifying best practices for implementation and enforcement. Research should address inconsistencies in definitions and implementation across regions; (b) Investigating the role of economic incentives, such as subsidies, tax breaks, and material recovery credits, in making E-waste recycling more financially competitive with primary mining; and (c) Developing harmonized international standards and regulations for E-waste management to combat illegal exports and promote responsible recycling practices globally.

Appendix A: E-Waste Recycling Financial Model for the United Arab Emirates (UAE)

| Item | Cost (USD) | Notes |

| Facility Setup (Lease + Modifications) | 218,000 | Includes electricals, ventilation, floor reinforcement, etc. |

| Processing Equipment | 817,000 | Shredders, eddy current separators, smelters, and crushers |

| Pollution Control & Waste Treatment | 109,000 | Fume scrubbers, liquid waste neutralization systems |

| Safety Equipment & PPE | 27,000 | For handling hazardous materials |

| Software & Digital Infrastructure | 41,000 | Inventory, traceability, compliance systems |

| Regulatory Licenses & Certifications | 20,000 | UAE environmental permits, EAD/ESMA approval |

| Vehicles (collection & transport) | 95,000 | 2 trucks and one support van |

| Total CAPEX | 1,327,000 |

| Item | Cost (USD/year) | Notes |

| Staff Salaries (12–15 staff) | 327,000 | Includes technical and admin staff |

| Facility Lease | 82,000 | Based on UAE industrial area average |

| Utilities (Power, Water) | 54,000 | Depends on energy use intensity |

| Maintenance & Repairs | 41,000 | Equipment upkeep |

| Waste Disposal Fees | 27,000 | Residuals from processing |

| Regulatory Compliance | 14,000 | Audits, reporting, testing |

| Transportation | 41,000 | Collection & logistics |

| Insurance | 11,000 | Property, liability, and worker safety |

| Marketing & Outreach | 16,000 | Community awareness, contracts |

| Total OPEX | 613,000 |

| Revenue Stream | Amount (USD/year) | Assumptions |

| Precious Metal Recovery (Au, Ag, Pd, etc.) | 681,000 | From PCBs, connectors (based on market rates and yield) |

| Base Metal Sales (Cu, Al, Fe) | 490,000 | Shredded and sorted materials |

| Plastic & Secondary Sales | 82,000 | Sorted plastics and resins |

| Recycling Service Fees (corporate/govt) | 272,000 | Disposal and compliance services for institutions |

| Total Revenue | 1,525,000 |

| Metric | Amount (USD) |

| Total Capital Investment | 1,327,000 |

| Operating Cost (Year 1) | 613,000 |

| Total Revenue (Year 1) | 1,525,000 |

| Net Profit (Year 1) | 912,000 |

| Payback Period | ~2 years |

Appendix B: Estimated Costs for Primary Mining of Critical Minerals

| Project | Mineral | CAPEX (USD) | Notes |

| Cobre Panama | Copper | $10 billion | One of the largest foreign investments in Panama, processing 85–100 million tonnes of ore annually. |

| Reko Diq (Pakistan) | Copper & Gold | $5.6 billion | Revised from $4 billion; aims to process 45–90 million tonnes per year. |

| Oyu Tolgoi (Mongolia) | Copper & Gold | $10 billion | Costs escalated from an initial estimate of $4.6 billion; significant contributor to Mongolia's GDP. |

| Sentinel Mine (Zambia) | Copper | $2.3 billion | Produces approximately 300,000 tonnes of copper annually. |

| Falchani Project | Lithium | $2.57 billion | Total project capital cost over the life of mine. |

| Grasberg Mine (Indonesia) | Copper & Gold | $175 million | Initial construction cost in the 1970s; significant infrastructure development included. |

| Project | Mineral | OPEX Estimate | Notes |

| Key Mining Corp. | Copper | $36.09 per tonne milled | Average operating cost over the life of mine, including mining, processing, and administrative expenses. |

| Australian Nickel Mining | Nickel | $20,000 per tonne | Higher production costs leading to competitiveness issues compared to Indonesian producers. |

| Indonesian Nickel Industry | Nickel | $5,000–$7,000 per tonne | Lower production costs due to technological advancements and significant investments. |

References

- Murthy, V.; Ramakrishna, S. A Review on Global E-Waste Management: Urban Mining towards a Sustainable Future and Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEMG - Environment Management Group. A New Circular Vision for Electronics: Time for a Global Reboot. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum (WEF). 2019. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_A_New_Circular_Vision_for_Electronics.pdf (Accessed 17 April 2025).

- Elgarahy, A.M.; Eloffy, M.; Priya, A.; Hammad, A.; Zahran, M.; Maged, A.; Elwakeel, K.Z. Revitalizing the circular economy: An exploration of e-waste recycling approaches in a technological epoch. Sustain. Chem. Environ. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti V, Baldé CP, Kuehr R, Bel G. The global E-waste monitor 2020. Bonn/Geneva/Rotterdam: United Nations University (UNU), International Telecommunication Union (ITU) & International Solid Waste Association (ISWA); 2020. p. 120. https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GEM_2020_def_july1_low.pdf (Accessed 17 April 2025).

- Paleologos, E.K.; O Mohamed, A.-M.; Singh, D.N.; O’kelly, B.C.; El Gamal, M.; Mohammad, A.; Singh, P.; Goli, V.S.N.S.; Roque, A.J.; A Oke, J.; et al. Sustainability challenges of clean-energy critical minerals: copper and rare earths. Environ. Geotech. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.O., Paleologos, E.K., Mohamed, D. , Fayad, A., Al Nahyan, M.T (2025). Critical Minerals Mining: A Path Toward Sustainable Resource Extraction and Aquatic Conservation; Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, Q.; Li, J.; Zeng, X. Mapping Recyclability of Industrial Waste for Anthropogenic Circularity: A Circular Economy Approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 11927–11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Kotter, R.; Özuyar, P.G.; Abubakar, I.R.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Matandirotya, N.R. Understanding Rare Earth Elements as Critical Raw Materials. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.O. Sustainable recovery of silver nanoparticles from electronic waste: applications and safety concerns. Acad. Eng. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M. Recovery of metals and nonmetals from electronic waste by physical and chemical recycling processes. Waste Manag. 2016, 57, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhao, P.R.; Ahmad, E.; Pant, K.; Nigam, K.D.P. Advancements in the field of electronic waste Recycling: Critical assessment of chemical route for generation of energy and valuable products coupled with metal recovery. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.O. Nexuses of critical minerals recovery from e-waste. Acad. Environ. Sci. Sustain. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, A.; Purchase, D.; Bisschop, L.; Chatterjee, D.; De Gioannis, G.; Garelick, H.; Kumar, A.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Piro, V.M.I.; Cera, M.; et al. 2002–2022: 20 years of e-waste regulation in the European Union and the worldwide trends in legislation and innovation technologies for a circular economy. RSC Sustain. 2024, 3, 1039–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32012L0019.

- Althaf, S.; Babbitt, C.W.; Chen, R. The evolution of consumer electronic waste in the United States. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 25, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. The role of critical minerals in clean energy transitions. World Energy Outlook special report. Paris: International Energy Agency; 2022. 281p. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions.

- Müller, D.; Groves, D.I.; Santosh, M.; Yang, C.-X. Critical metals: Their applications with emphasis on the clean energy transition. Geosystems Geoenvironment 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, R. 2020 - Geothermal Energy, Editor(s): Trevor M. Letcher, Future Energy (Third Edition), Elsevier, 2020, Pages 431-445, ISBN 9780081028865. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Kong, Q. Green energy transition and sustainable development of energy firms: An assessment of renewable energy policy. Energy Econ. 2022, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D., Lathwal, P., Lopez Rocha, S.C., 2023. Unleashing the Power of Hydrogen For the Clean Energy transition. Sustainable energy For All. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/energy/unleashing-power-hydrogen-clean-energy-transition (accessed 17 April 2025).

- European Commission, 2023. Study on the critical raw materials for the EU 2023: final report; https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/publications/study-critical-raw-materials-eu-2023-final-report_en (accessed 17 April 2025).

- Fan, C.; Xu, C.; Shi, A.; Smith, M.P.; Kynicky, J.; Wei, C. Origin of heavy rare earth elements in highly fractionated peraluminous granites. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2022, 343, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries. Indium (2023), pp. 88-89; https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/mineral-commodity-summaries.

- Pandey, R.; Krmíček, L.; Müller, D.; Pandey, A.; Cucciniello, C. Alkaline rocks and their economic and geodynamic significance through geological time. Geol. Soc. London, Spéc. Publ. 2024, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wong, C.W.; Li, C. Circular economy practices in the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) industry: A systematic review and future research agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. The use of aluminum alloys in structures: Review and outlook. Structures 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G. Antimony production and commodities. In: mineral processing and extractive metallurgy handbook. Soc. Mining Metall. Expl. (SME) (2019), pp. 431-442; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299133344_Antimony_Production_and_Commodites.

- Zhao, G.; Li, W.; Geng, Y.; Bleischwitz, R. Uncovering the features of global antimony resource trade network. Resour. Policy 2023, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H., Rawal, N., and Mathew, B. The characteristics, toxicity and effects of cadmium. Int. J. Nanotech. Nanosci., 3 (2015), pp. 1-9; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305778858_The_characteristics_toxicity_and_effects_of_cadmium.

- Ahmad, N.I.; Kar, Y.B.; Doroody, C.; Kiong, T.S.; Rahman, K.S.; Harif, M.N.; Amin, N. A comprehensive review of flexible cadmium telluride solar cells with back surface field layer. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F.; Renzi, P.; Cavallo, C.; Gerbaldi, C. Caesium for Perovskite Solar Cells: An Overview. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12183–12205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, B.R.; Turnbull, D.; Ashworth, L.; McKnight, S. Geochemical characteristics and structural setting of lithium–caesium–tantalum pegmatites of the Dorchap Dyke Swarm, northeast Victoria, Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 70, 763–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, W. Research on the evolution of the global import and export competition network of chromium resources from the perspective of the whole industrial chain. Resour. Policy 2022, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, S.v.D.; Kleijn, R.; Sprecher, B.; Tukker, A. Identifying supply risks by mapping the cobalt supply chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinova, E.; Evans, C.; Lèbre, É.; Stringer, M.; Azadi, M.; Valenta, R. Will global cobalt supply meet demand? The geological, mineral processing, production and geographic risk profile of cobalt. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Nechaev, V.P.; French, D.; Graham, I.; Lang, Y.; Li, Z.; Dai, S. Enrichment of critical metals (Li, Ga, and rare earth elements) in the early Permian coal seam from the Jincheng Coalfield, southeastern Qinshui Basin, northern China: With an emphasis on cookeite as the Li host. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Steen, J.; Ali, S.; Valenta, R. Carbon-adjusted efficiency and technology gaps in gold mining. Resour. Policy 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Geng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, S. Uncovering the key features of gold flows and stocks in China. Resour. Policy 2023, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubchuk, A. Russian gold mining: 1991 to 2021 and beyond. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Mao, J.; Chen, W.; Shi, L. Indium in mainland China: Insights into use, trade, and efficiency from the substance flow analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.A.; Sanislav, I.V.; Cathey, H.E.; Dirks, P.H.G.M. Geochemistry of indium in magmatic-hydrothermal tin and sulfide deposits of the Herberton Mineral Field, Australia. Miner. Deposita 2023, 58, 1297–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; You, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Bi, L.; Liu, Z.; Tan, S. The enrichment mechanism of indium in Fe-enriched sphalerite from the Bainiuchang Zn-Sn polymetallic deposit, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, J. Lithium brine production, reserves, resources and exploration in Chile: An updated review. Ore Geol. Rev. 2021, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, A.; Alonso, R.N.; Lucassen, F.; Korte, L.; Kasemann, S.A. Lithium and Sr isotopic composition of salar deposits in the Central Andes across space and time: the Salar de Pozuelos, Argentina. Miner. Deposita 2021, 57, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelstein, K. Globally sustainable manganese metal production and use. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3736–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, F. Insights into the global flow pattern of manganese. Resour. Policy 2020, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henckens, M.; Driessen, P.; Worrell, E. Molybdenum resources: Their depletion and safeguarding for future generations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outteridge, T.; Kinsman, N.; Ronchi, G.; Mohrbacher, H. Editorial: Industrial relevance of molybdenum in China. Adv. Manuf. 2019, 8, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, D.; Wang, C. Analysis of international nickel flow based on the industrial chain. Resour. Policy 2022, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilshara, P.; Abeysinghe, B.; Premasiri, R.; Dushyantha, N.; Ratnayake, N.; Senarath, S.; Ratnayake, A.S.; Batapola, N. The role of nickel (Ni) as a critical metal in clean energy transition: applications, global distribution and occurrences, production-demand and phytomining. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Beecham, J. A Study of Platinum Group Metals in Three-Way Autocatalysts. Platin. Met. Rev. 2013, 57, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, K., Okabe, T.H. (2024) Platinum group metals production. Treatise Process Metallurgy Vol. 3 Industrial Processes (2nd ed.): 751–770; 10.1016/B978-0-323-85373-6.00029-6.

- Dostal, J. Rare Earth Element Deposits of Alkaline Igneous Rocks. Resources 2017, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Qiu, K., Diao, X., Ma, J., Yu, H., An, M., Zhi, C., Krmicek, L., Deng, J. (2024) The giant Baerzhe REE-Nb-Zr-Be deposit, Inner Mongolia, China, an Early Cretaceous analogue of the Strange Lake rare-metal deposit, Quebec. In: Pandey, R., Pandey, A., Krmicek, L., Cucciniello, C., Müller, D. (Eds) Alkaline Rocks and Their Economic and Geodynamic Significance Through Geological Time. Geol. Soc. London Spec. Publ. 551 (in press).

- Funari, V.; Gomes, H.I.; Coppola, D.; Vitale, G.A.; Dinelli, E.; de Pascale, D.; Rovere, M. Opportunities and threats of selenium supply from unconventional and low-grade ores: A critical review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-W.; Cheng, T.-M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yueh, K.-C.; Tang, S.-Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, C.-L.; Tsai, H.-S.; Yu, Y.-J.; Lai, C.-H.; et al. High-yield recycling and recovery of copper, indium, and gallium from waste copper indium gallium selenide thin-film solar panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G.; Tremouli, A.; Tsakiridis, P.; Remoundaki, E.; Lyberatos, G. Silver Recovery from End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels Based on Microbial Fuel Cell Technology. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2023, 15, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, N.T.; Kim, H.; Frenzel, M.; Moats, M.S.; Hayes, S.M. Global tellurium supply potential from electrolytic copper refining. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katepalli, A.; Wang, Y.; Shi, D. Solar harvesting through multiple semi-transparent cadmium telluride solar panels for collective energy generation. Sol. Energy 2023, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B. Formation of tin ore deposits: A reassessment. Lithos 2020, 402-403, 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qin, W.; Li, J.; Tian, Z.; Jiao, F.; Yang, C. Tracing the global tin flow network: highly concentrated production and consumption. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Hu, B.; Zhao, L.; Liu, S. Titanium alloy production technology, market prospects and industry development. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldybayev, G.; Korabayev, A.; Sharipov, R.; Al Azzam, K.M.; Negim, E.-S.; Baigenzhenov, O.; Alimzhanova, A.; Panigrahi, M.; Shayakhmetova, R. Processing of titanium-containing ores for the production of titanium products: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hong, H.; Zhang, H. The evolution and influencing factors of international tungsten competition from the industrial chain perspective. Resour. Policy 2021, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluzo, B.M.T.C.; Kraka, E. Uranium: The Nuclear Fuel Cycle and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, D.E., 2019. Vanadium. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/vanadium/mcs-2019-vanad.

- Petranikova, M.; Tkaczyk, A.; Bartl, A.; Amato, A.; Lapkovskis, V.; Tunsu, C. Vanadium sustainability in the context of innovative recycling and sourcing development. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.S.; Head, I.; Premier, G.C.; Scott, K.; Yu, E.; Lloyd, J.; Sadhukhan, J. A multilevel sustainability analysis of zinc recovery from wastes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 113, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostek, L.; Pirard, E.; Loibl, A. The future availability of zinc: Potential contributions from recycling and necessary ones from mining. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D., Groves, D. I., and Santosh, M. (2024). Metallic Mineral Resources: The Critical Components for a Sustainable Earth. University of Western Australia, 10.1016/C2023-0-51506-X.

- Nanjo, M., Urban mine, Bulletin of the Research Institute for Mineral Dressing and Metallurgy at Tohoku University, Tohoku University, 1987, pp 239–241. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T., and Halada, K. Urban Mining Systems, Springer Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology, Springer, Japan, Tokyo, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Fornalczyk, A., Willner, J., Francuz, K., and Cebulski, J. (2013). E-waste as a source of valuable metals. October 2013. Archives of Materials Science and Engineering 63(2):87-92; http://www.amse.acmsse.h2.pl/vol63_2/6325.pdf.

- Baldé, C.P., Kuehr, R., Yamamoto, T., McDonald, R., D’Angelo, E., Althaf, S., Bel, G., Deubzer, O., Fernandez-Cubillo, E., Forti, V., Gray, V., Herat, S., Honda, S., Iattoni, G., Khetriwal, D.S., di Cortemiglia, V.L., Lobuntsova, Y., Nnorom, I., Pralat, N., and Wagner, M. (2024). International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). 2024. Global E-waste Monitor 2024. Geneva/Bonn. Pdf version: 978-92-61-38781-5; https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GEM_2024_18-03_web_page_per_page_web.pdf (accessed 17 April 2025).

- Rawat S, Verma L, Singh J. Environmental hazards and management of E-waste. Environmental concerns and sustainable development. Amsterdam: Springer; 2020. p.381–98.; 10.1007/978-981-13-6358-0_16.

- Ahirwar, R.; Tripathi, A.K. E-waste management: A review of recycling process, environmental and occupational health hazards, and potential solutions. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiella, F.; D’adamo, I.; Koh, S.L.; Rosa, P. Recycling of WEEEs: An economic assessment of present and future e-waste streams. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, L. Metallurgical recovery of metals from electronic waste: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 158, 228–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Rhamdhani, M.A.; Brooks, G.; Masood, S. Metal Extraction Processes for Electronic Waste and Existing Industrial Routes: A Review and Australian Perspective. Resources 2014, 3, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Rhamdhani, M.A.; Brooks, G.; Masood, S. Metal Extraction Processes for Electronic Waste and Existing Industrial Routes: A Review and Australian Perspective. Resources 2014, 3, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Pahlevani, F.; Levick, K.; Cole, I.; Sahajwalla, V. Synthesis of copper-tin nanoparticles from old computer printed circuit boards. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; Jadhao, P.R.; Pant, K.; Nigam, K. Novel technologies and conventional processes for recovery of metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment: Challenges & opportunities – A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rene, E.R.; Sethurajan, M.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Kumar, G.; Dung, T.N.B.; Brindhadevi, K.; Pugazhendhi, A. Electronic waste generation, recycling and resource recovery: Technological perspectives and trends. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, M.M.; Myneni, V.R.; Gudeta, B.; Komarabathina, S. Toxic Metal Recovery from Waste Printed Circuit Boards: A Review of Advanced Approaches for Sustainable Treatment Methodology. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramprasad, C.; Gwenzi, W.; Chaukura, N.; Azelee, N.I.W.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Naushad, M.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Strategies and options for the sustainable recovery of rare earth elements from electrical and electronic waste. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelle. United States Energy Association: critical material recovery from E-waste. Final report. Subagreement no. 633-2023-004-01; 2023. Available from: https://usea.org/sites/default/files/USEA633-2023-004-01_CMfromEwaste_FINAL_REPORT.

- Shahabuddin, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Chowdhury, J.I.; Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Uddin, M.A. A review of the recent development, challenges, and opportunities of electronic waste (e-waste). Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 20, 4513–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, Z. A review of current progress of recycling technologies for metals from waste electrical and electronic equipment. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Xia, F.; Xia, Y.; Xie, B. Recycle Gallium and Arsenic from GaAs-Based E-Wastes via Pyrolysis–Vacuum Metallurgy Separation: Theory and Feasibility. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 6, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, F.; Golmohammadzadeh, R.; Pickles, C.A. Potential and current practices of recycling waste printed circuit boards: A review of the recent progress in pyrometallurgy. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-F.; Chou, S.-L.; Lo, S.-L. Gold recovery from waste printed circuit boards of mobile phones by using microwave pyrolysis and hydrometallurgical methods. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2022, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasker, P. A., McCleverty, J. A., Plieger, P. G., Meyer, T. J., and West, L. C. 9.17 Metal Complexes for Hydrometallurgy and Extraction, in Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II, Elsevier, 2004, vol. 9, pp. 759–807.; https://www.academia.edu/79331550/Metal_Complexes_for_Hydrometallurgy_and_Extraction (accessed 17 April 2025).

- Akcil, A.; Erust, C.; Gahan, C.S.; Ozgun, M.; Sahin, M.; Tuncuk, A. Precious metal recovery from waste printed circuit boards using cyanide and non-cyanide lixiviants – A review. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunsu, C.; Petranikova, M.; Gergorić, M.; Ekberg, C.; Retegan, T. Reclaiming rare earth elements from end-of-life products: A review of the perspectives for urban mining using hydrometallurgical unit operations. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 156, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, F.-R.; Weng, H.; Qi, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.-S.; Chen, M. A novel recovery method of copper from waste printed circuit boards by supercritical methanol process: Preparation of ultrafine copper materials. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatariants, M.; Yousef, S.; Sakalauskaitė, S.; Daugelavičius, R.; Denafas, G.; Bendikiene, R. Antimicrobial copper nanoparticles synthesized from waste printed circuit boards using advanced chemical technology. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglio, F., and Birloaga, I. (editors) Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Recycling: Aqueous Recovery Methods, Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials, Woodhead Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier, Duxford, United Kingdom; Cambridge, MA, United States, 2018a, I. (editors) Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Recycling: Aqueous Recovery Methods, Woodhead Publishing Series in Electronic and Optical Materials, Woodhead Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier, Duxford, United Kingdom; Cambridge, MA, United States, 2018; 10.1016/B978-0-08-102057-9.

- Yousef, S.; Tatariants, M.; Makarevičius, V.; Lukošiūtė, S.-I.; Bendikiene, R.; Denafas, G. A strategy for synthesis of copper nanoparticles from recovered metal of waste printed circuit boards. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shang, H.; Ren, Y.; Yue, Y.; Li, H.; Bian, Z. Systematic Assessment of Precious Metal Recovery to Improve Environmental and Resource Protection. ACS ES&T Eng. 2022, 2, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, T.; Yang, J.; Aromaa-Stubb, R.; Zhu, Q.; Lundström, M. Process simulation and life cycle assessment of hydrometallurgical recycling routes of waste printed circuit boards. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, D.; Joshi, D.; Upreti, M.K.; Kotnala, R.K. Chemical and biological extraction of metals present in E waste: A hybrid technology. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villares, M.; Işıldar, A.; Beltran, A.M.; Guinee, J. Applying an ex-ante life cycle perspective to metal recovery from e-waste using bioleaching. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.M.; Mirkouei, A.; Reed, D.; Thompson, V. Current nature-based biological practices for rare earth elements extraction and recovery: Bioleaching and biosorption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yang, M.; Wan, A.; Yu, S.; Yao, Z. Bioleaching of Typical Electronic Waste—Printed Circuit Boards (WPCBs): A Short Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokarian, P.; Bakhshayeshi, I.; Taghikhah, F.; Boroumand, Y.; Erfani, E.; Razmjou, A. The advanced design of bioleaching process for metal recovery: A machine learning approach. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaashikaa, P.; Priyanka, B.; Kumar, P.S.; Karishma, S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Indraganti, S. A review on recent advancements in recovery of valuable and toxic metals from e-waste using bioleaching approach. Chemosphere 2022, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithya, R.; Sivasankari, C.; Thirunavukkarasu, A. Electronic waste generation, regulation and metal recovery: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 1347–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Das, R.; Abraham, J. Bioleaching of heavy metals from spent batteries using Aspergillus nomius JAMK1. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 17, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Timilsina, A.; Gautam, A.; Adhikari, K.; Bhattarai, A.; Aryal, N. Phytoremediation: Mechanisms, plant selection and enhancement by natural and synthetic agents. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, F.-R.; Zhang, F.-S. Preparation of nano-Cu2O/TiO2 photocatalyst from waste printed circuit boards by electrokinetic process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.; Zhang, Z.; E Shine, A.; Free, M.L.; Sarswat, P.K. E-wastes derived sustainable Cu recovery using solvent extraction and electrowinning followed by thiosulfate-based gold and silver extraction. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyapour, H.; Mohammadnejad, S. Optimization of the operating parameters in gold electro-refining. Miner. Eng. 2022, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italimpianti, n.d ; https://www.italimpianti.it/en/catalogue/refining/precious-metals-electrolysis/electrolytic-gold-refining-plant-type-iao-a (accessed 24 February 2025).

- Jo, S.; Kadam, R.; Jang, H.; Seo, D.; Park, J. Recent Advances in Wastewater Electrocoagulation Technologies: Beyond Chemical Coagulation. Energies 2024, 17, 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajmi, F.; Al-Marri, M.; Almomani, F. Electrocoagulation Process as an Efficient Method for the Treatment of Produced Water Treatment for Possible Recycling and Reuse. Water 2024, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, B.A., Lokesh, N., Buradi, A., Santhosh, N., Praveena, B.L., Vignesh, R., 2022. A comprehensive review of emerging additive manufacturing (3D printing technology): Methods, materials, applications, challenges, trends and future potential. Mater. Today.: Proc. 52, 1309–1313. [CrossRef]

- Al Rashid, A.; Koç, M. Additive manufacturing for sustainability and circular economy: needs, challenges, and opportunities for 3D printing of recycled polymeric waste. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera, E.H.; Cremades, R.; van Leeuwen, E.; van Timmeren, A. Additive manufacturing in cities: Closing circular resource loops. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A. Analysing the role of Industry 4.0 technologies and circular economy practices in improving sustainable performance in Indian manufacturing organisations. Prod. Plan. Control. 2021, 34, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, C.L.; Al Aziz, R.; Ahmed, T.; Misbauddin, S.; Moktadir, A. Impact of industry 4.0 technologies on sustainable supply chain performance: The mediating role of green supply chain management practices and circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabelin, C.B.; Park, I.; Phengsaart, T.; Jeon, S.; Villacorte-Tabelin, M.; Alonzo, D.; Yoo, K.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N. Copper and critical metals production from porphyry ores and E-wastes: A review of resource availability, processing/recycling challenges, socio-environmental aspects, and sustainability issues. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://businessplan-templates.com/blogs/running-costs/e-waste-recycling?utm.

- https://www.iea.org/reports/global-critical-minerals-outlook-2024/outlook-for-key-minerals?

- Escobar-Pemberthy, N.; Ivanova, M. Implementation of Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Rationale and Design of the Environmental Conventions Index. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T. A comparative study of national variations of the European WEEE directive: manufacturer’s view. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 19920–19939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K.A.; Agbemabiese, L. E-waste legislation in the US: An analysis of the disparate design and resulting influence on collection rates across States. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 64, 1067–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, O.S.; Williams, I.D.; Shaw, P.J. Global E-waste management: Can WEEE make a difference? A review of e-waste trends, legislation, contemporary issues and future challenges. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, A. , Geeraerts, K., and Schweizer, J.-P. Illegal Shipment of E-waste from the EU: A Case Study on Illegal E-waste Export from the EU to China, 2015. https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2015/efface_illegal_shipment_of_e_waste_from_the_eu_0. 17 April.

- Patil, R.A.; Ramakrishna, S. A comprehensive analysis of e-waste legislation worldwide. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 14412–14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E-waste Management Rules, 2016, https://jaipurmc.org/PDF/Auction_MM_RTI_Act_Etc_PDF/E-WASTE%20MANAGMENT%20RULES%202016. 17 April.

- E-waste Management Rules, 2022; https://cpcb.nic.in/rules-6/ (accessed ). 17 April.

- Bagwan, W.A. Electronic waste (E-waste) generation and management scenario of India, and ARIMA forecasting of E-waste processing capacity of Maharashtra state till 2030. Waste Manag. Bull. 2023, 1, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A.; Govind, M. Emerging trends in consumers’ E-waste disposal behaviour and awareness: A worldwide overview with special focus on India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 117, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpour, K.; Jusoh, A.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Cavallaro, F.; Nor, K.M.; Zavadskas, E.K. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Intention to Return the End of Life Electronic Products through Reverse Supply Chain Management for Reuse, Repair and Recycling. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Belis, V.; Braulio-Gonzalo, M.; Juan, P.; Bovea, M.D. Consumer attitude towards the repair and the second-hand purchase of small household electrical and electronic equipment. A Spanish case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 158, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.; Soori, P.K.; Ghaith, F. Analysis of Households’ E-Waste Awareness, Disposal Behavior, and Estimation of Potential Waste Mobile Phones towards an Effective E-Waste Management System in Dubai. Toxics 2021, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Malodia, S.; Awan, U.; Sakashita, M.; Kaur, P. Extended valence theory perspective on consumers' e-waste recycling intentions in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanath, K.; Kumar, S.A. The role of communication medium in increasing e-waste recycling awareness among higher educational institutions. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 833–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thukral, S.; Shree, D.; Singhal, S. Consumer behaviour towards storage, disposal and recycling of e-waste: systematic review and future research prospects. Benchmarking: Int. J. 2022, 30, 1021–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I. Household's awareness and participation in sustainable electronic waste management practices in Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Shah, S.M.M.; Adeel, S.; Gilal, R.G.; Gilal, N.G. Consumer e-waste disposal behaviour: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 46, 1785–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, K.A.; Singh, A.; Siddiqua, A.; El Gamal, M.; Laeequddin, M. E-Waste Recycling Behavior in the United Arab Emirates: Investigating the Roles of Environmental Consciousness, Cost, and Infrastructure Support. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu T, Chen H, Guo YL. Investigating innovation diffusion, social influence, and personal inner forces to understand people’s participation in online E-waste recycling. J Retail Consum Serv. 2023;73:103366. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajan, P.; Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Hanifah, H.; Thurasamay, R. Sustaining the environment through e-waste recycling: an extended valence theory perspective. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 76, 1059–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, T.; Arnold, M.; Ulber, M. Circular value chain blind spot – A scoping review of the 9R framework in consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Important properties | Industrial utilization | Major producers | Supply risk | References |

| Aluminum | Conductive, flexible, durable, recycleable | Aerospace, defense, and infrastructure | China, India | Moderate | [26] |

| Antimony | Flame proofing compound | Flame retardants, batteries, and alloys | China, India | High | [27,28] |

| Cadmium | Fatigue and corrosion resistive | Solar panels and batteries | China, South Korea | High | [29,30] |

| Caesium | Higly reactive, pyrophoric | Atomic clocks, drilling fluids, and electronics | Canada, Australia | High | [31,32] |

| Chromite | Durability, hardness, wear resistance | Source of chromium, used in stainless steel and alloys | South Africa, Turkey | Very high | [33] |

| Cobalt | Wear resistance, high strength, magnetic | Batteries, superalloys, and magnets | Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia | High | [34,35] |

| Gallium | Conductive | Semiconductors and LEDs | China, Japan | High | [36] |

| Gold | Inert, high conductivity | Jewelry, electronics, and investment | China, Australia | Moderate | [37,38,39] |

| Indium | High conductivity, corrosion resistive, low melting point | Touchscreens, solar panels, and LCDs | China, South Korea | High | [40,41,42] |

| Lithium | Resistance to abrasion in synthetic rubber | Batteries and energy storage | Chile, Australia | High | [43,44] |

| Manganese | Corrosion resistive | Steel production and batteries | China, South Africa | Moderate | [45,46] |

| Molybdenum | Strength, corrosion resistive, conductivity | Steel alloys and catalysts | China, Chile | Moderate | [47,48] |

| Nickel | Corrosion resistive, toughness | Batteries, stainless steel, and alloys | Indonesia, Philippines | Moderate | [49,50] |

| Platinum Group Elements (PGEs) | Hardness, corrosion resitive, high melting points | Catalytic converters and hydrogen fuel cells | South Africa, Russia | Very high | [51,52] |

| Rare Earth Elements (REEs) | Magnetic, phosphorescent | Electronics, magnets, and defense applications | China, USA | Very high | [53,54] |

| Selenium | Photoconductive | Solar panels and electronics | China, Japan | High | [55,56] |

| Silver | High conductivity, antibacterial properties | Jewelry, electronics, and investment | Mexico, China | Moderate | [57] |

| Tellurium | Piezoelectric | Solar cells and thermoelectrics | China, Japan | High | [58,59] |

| Tin | Corrosion resistive, light weight | Soldering and electronics | China, Indonesia | Moderate | [60,61] |

| Titanium | Hardness, resistive, light weight, chemically inert | Aerospace, medical, and pigments | China, Mozambique | Moderate | [62,63] |

| Tungsten | High melting and boiling points, high density | Cutting tools, defense, and electronics | China, Russia | High | [64] |

| Uranium | High density, radioactive | Nuclear power and defense applications | Kasakhstan, Namibia | Moderate | [65] |

| Vanadium | Toughness, shock and vibration resistance | Steel alloys and redox flow batteries | China, Russia | Moderate | [66,67] |

| Zinc | Corrosion resistive | Galvanization and alloys | China, Peru | Low | [68,69] |

| General Processes | An example for IT and Telecommunication Equipment Separation Processes | |||

| Steps | Products | Manual Processing | Mechanical Processing | Products |

| A. Sorting and Dismantling | Separation of reusable parts | 1. Sorting | Capacitors, tuners, batteries | |

| B. Mechanical Processing (size reduction and sorting | Separation of metals, plastics, etc. | 2. Crushing | ||

| C. Eddy Current Separation | Separation of nonferrous metals | 3. Sorting | Valuable and hazardous components | |

| D. Magnetic Separation | Separation of ferrous metals | 4. Shredding | ||

| E. Density Separation | Separation of plastics | 5. Sorting | Valuable and hazardous components | |

| F. Electrostatic Separation | Separation of conductive metals from non-conductive materials | 6. Shredding | ||

| G. Disposal | Landfilling | 7. Eddy current separation | Nonferrous metals | |

| 8. Magnetic separation | Ferrous metals | |||

| Pyrometallurgical Processes | Description |

| ❖ Incineration | • E-waste is incinerated at high temperatures in a controlled environment, breaking down organic materials and combustibles while leaving metal-rich ash. |

| ❖ Smelting | • Ashes or shredded E-waste are melted in high-temperature furnaces, allowing metals to separate from non-metallic materials due to their lower melting points. • Valuable metals like copper, lead, and precious metals are collected in molten form. |

| ❖ Roasting | • Metal compounds are converted into oxides or sulfides for further refining |

| ❖ Plasma arc furnaces | • Metals are extracted using high-energy plasma. |

| ❖ Volatilization | • Certain metals like mercury and zinc are recovered through controlled evaporation |

| ❖ Cupellation | • The metal-rich material is heated in a cupel (a porous container) with a blast of air, which oxidizes impurities and leaves behind the precious metals. • It is used to recover precious metals like gold and silver. |

| Hydrometallurgical Processes | Description |

| ❖ Leaching | Chemicals such as sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), nitric acid, or cyanide (CN-) are used to dissolve specific metals. • H₂SO₄ is used to extract base metals like Zn, Fe, Co, Pb, Al, and Cu. HNO₃ is used to extract base metals (including REE) and noble metals (i.e. Ag, Pd, Cu, Hg). • Cyanide solutions are used especially for gold recovery, under strictly alkaline conditions in the presence of oxygen |

| ❖ Ammonia leaching | It is sometimes used for selective recovery of copper and nickel. With higher reduction potential metals, i.e. Cu and Ag, its action can be empowered by adding oxidants such as H2O2, (NH4)2S2O8, or others. |

| ❖ Solvent extraction (SX) | Solvent extraction selectively recovers specific metals using organic solvents that bind to target metal ions. • In copper recovery, the leachate containing dissolved copper ions is mixed with an organic solvent, such as a hydroxyoxime-based extractant, which selectively binds to copper. The copper-laden solvent is then separated and stripped using sulfuric acid to regenerate copper sulfate, which can be further processed into pure copper via electrowinning. • This method is also used to extract REEs from E-waste, such as neodymium and dysprosium from magnets in hard drives. |

| ❖ Ion exchange | Ion exchange relies on resins to capture specific metal ions from the solution. • Gold recovery from E-waste uses strong-base anion exchange resins that selectively adsorb gold cyanide complexes from the leachate. The resin is then stripped with a suitable eluent, such as thiourea or sodium thiosulfate, releasing gold for further refining. • Platinum group metals (PGMs) like palladium and platinum from catalytic converters in E-waste can be extracted using chelating resins designed to bind specifically to these elements. |

| ❖ Precipitation | Precipitation recovers metals by adjusting the pH of the solution using reagents that cause metal hydroxides or sulfides to form. For examples: • Gold precipitation: Sodium metabisulfite or ferrous sulfate is added to a gold-bearing solution, reducing gold ions to solid elemental gold; • Nickel and cobalt recovery: By adding sodium hydroxide, nickel and cobalt precipitate as hydroxides, which can be further refined; and • Lead and zinc removal: Sulfide precipitation using hydrogen sulfide gas or sodium sulfide helps recover lead and zinc as insoluble sulfides from E-waste processing solutions. |

| Technology | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| ❖ Physical & Mechanical Separation | • Low cost and energy-efficient • No use of hazardous chemicals • Effective for pre-processing |

• Ineffective for fine or mixed metal recovery • Cannot separate metals from complex compounds |

| ❖ Hydrometallurgical Processes | • High selectivity and metal recovery efficiency • Lower energy consumption compared to pyrometallurgy • Can recover multiple metals (gold, silver, copper, etc.) |

• Requires hazardous chemicals (e.g., cyanide, acids) • Generates wastewater that requires treatment • Slow processing |

| ❖ Pyrometallurgical Processes | • High recovery efficiency for various metals • Fast processing time • Can handle mixed metal compositions |

• High energy consumption • Air pollution from gas emissions • Requires pre-treatment to remove plastics and hazardous materials |

| ❖ Bio-metallurgy | • Environmentally friendly • Low energy consumption • Can recover metals from low-grade E-waste |

• Slow processing rate • Requires specific conditions for microbial activity • Limited scalability for industrial applications |

| ❖ Electrochemical Processes | • High-purity metal recovery • Low chemical waste • Can be integrated with hydrometallurgical processes |

• Requires significant electricity input • Slower compared to pyrometallurgy • Ineffective for complex metal mixtures |

| Technology | Gold (Au) | Silver (Ag) | Copper (Cu) | Rare Earth Elements (REEs) | Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) | Ferrous Metals (Fe, Ni, Co) | Aluminum (Al) |

| ❖ Physical & Mechanical Separation | ❌ Not effective | ❌ Not effective | ✅ Good efficiency (electrostatic, density separation) | ❌ Not effective | ❌ Not effective | ✅ Good efficiency (magnetic separation) | ✅ Good efficiency (eddy current separation) |

| ❖ Hydrometallurgical Processes | ✅ Very effective (cyanide leaching) | ✅ Very effective (acid leaching) | ✅ High efficiency (acid leaching, solvent extraction) | ❌ Limited effectiveness | ✅ High efficiency (chloride leaching) | ❌ Limited effectiveness | ❌ Inefficient |

| ❖ Pyrometallurgical Processes | ✅ High efficiency (smelting, refining) | ✅ High efficiency (smelting) | ✅ High efficiency (smelting, roasting) | ❌ Not commonly used | ✅ Effective (high-temperature refining) | ✅ Effective for ferrous metals | ✅ Effective (high-temperature recovery) |

| ❖ Bio-metallurgy | ✅ Possible (bioleaching) | ✅ Possible (bioleaching) | ✅ Good efficiency (bioleaching with bacteria) | ✅ Promising research (microbial bioleaching) | ❌ Limited research | ❌ Not effective | ❌ Inefficient |

| ❖ Electrochemical Processes | ✅ High purity recovery (electrowinning) | ✅ High purity recovery (electrowinning) | ✅ Effective (electrowinning, electrorefining) | ❌ Not effective | ✅ Effective (electrorefining for platinum) | ❌ Inefficient | ❌ Inefficient |

| Aspect | Primary Mining | E-Waste Recycling |

| Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) | Very high: Typically, $500 million–$10+ billion USD | Moderate: Typically, $2 million–$10 million USD for medium-scale facilities |

| Operating Expenditure (OPEX) |

Moderate to high: $20,000–$50,000 USD/tonne of refined critical metal | Lower: $10,000–$25,000 USD/tonne, depending on technology and material type |

| Ore/Material Grade | Often low-grade ore (0.5–3%), requiring processing of huge volumes | E-waste has high metal content (up to 40% by weight), e.g., gold in PCBs can be 100× richer than gold ore |

| Energy Consumption | High: Large-scale excavation, crushing, smelting | Lower: Mostly mechanical, chemical, and electrochemical processes |

| GHG Emissions | High: Emissions from mining operations, heavy fuel usage, and smelting | Lower: Potential for near-zero emissions if powered by renewables |

| Environmental Impact | Significant: Land degradation, tailings, water contamination | Much lower: Fewer emissions and no landscape disruption, but still requires hazardous waste management |

| Extraction Efficiency | Moderate: Depends on ore quality and technology (often < 90%) | High: Precious metals like Au, Pd, and Cu can be recovered with >90% efficiency with advanced methods |

| Resource Scalability | Limited by geology, geography, and permitting | Scalable in urban areas; urban mining becomes more viable with growing e-waste volumes |

| Time to Set Up Operations | Long: Often 5–10 years due to exploration, feasibility studies, permits | Short: Typically, 1–2 years for plant construction and operation setup |

| Economic Viability | Highly dependent on metal prices and mine life | Economically attractive at small scale, especially where recycling fees and metal recovery both generate value |

| Strategic Benefit | Supports supply independence, but geopolitically sensitive | Enhances circular economy, reduces import dependency, and supports critical mineral security |

| Step | Action | Key Stakeholders | Expected Outcome |

| 1. Improve Recycling Infrastructure | ❖ Invest in AI-powered sorting and robotics for automation | ❖ Governments, Recycling Firms | ❖ Higher efficiency, reduced labor risks |

| 2. Implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) | ❖ Mandate electronics manufacturers to finance E-waste collection and recycling | ❖ Government Regulators, Tech Industry | ❖ Higher collection and recycling rates |

| 3. Strengthen Consumer Awareness Campaigns | ❖ Launch educational programs and incentives for responsible recycling | ❖ NGOs, Tech Companies, Media | ❖ Increased participation in recycling programs |

| 4. Expand Public-Private Partnerships | ❖ Encourage collaboration between government and private sector in E-waste recycling | ❖ Municipal Authorities, Private Investors | ❖ Increased funding and infrastructure expansion |

| 5. Promote Eco-Design and Right-to-Repair Laws | ❖ Require manufacturers to produce repairable and recyclable devices | ❖ Policy Makers, Tech Industry | ❖ Reduced E-waste generation |

| 6. Introduce CE Initiatives | ❖ Encourage businesses to use recycled materials and modular design | ❖ Corporations, Researchers | ❖ Sustainable product life cycles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).