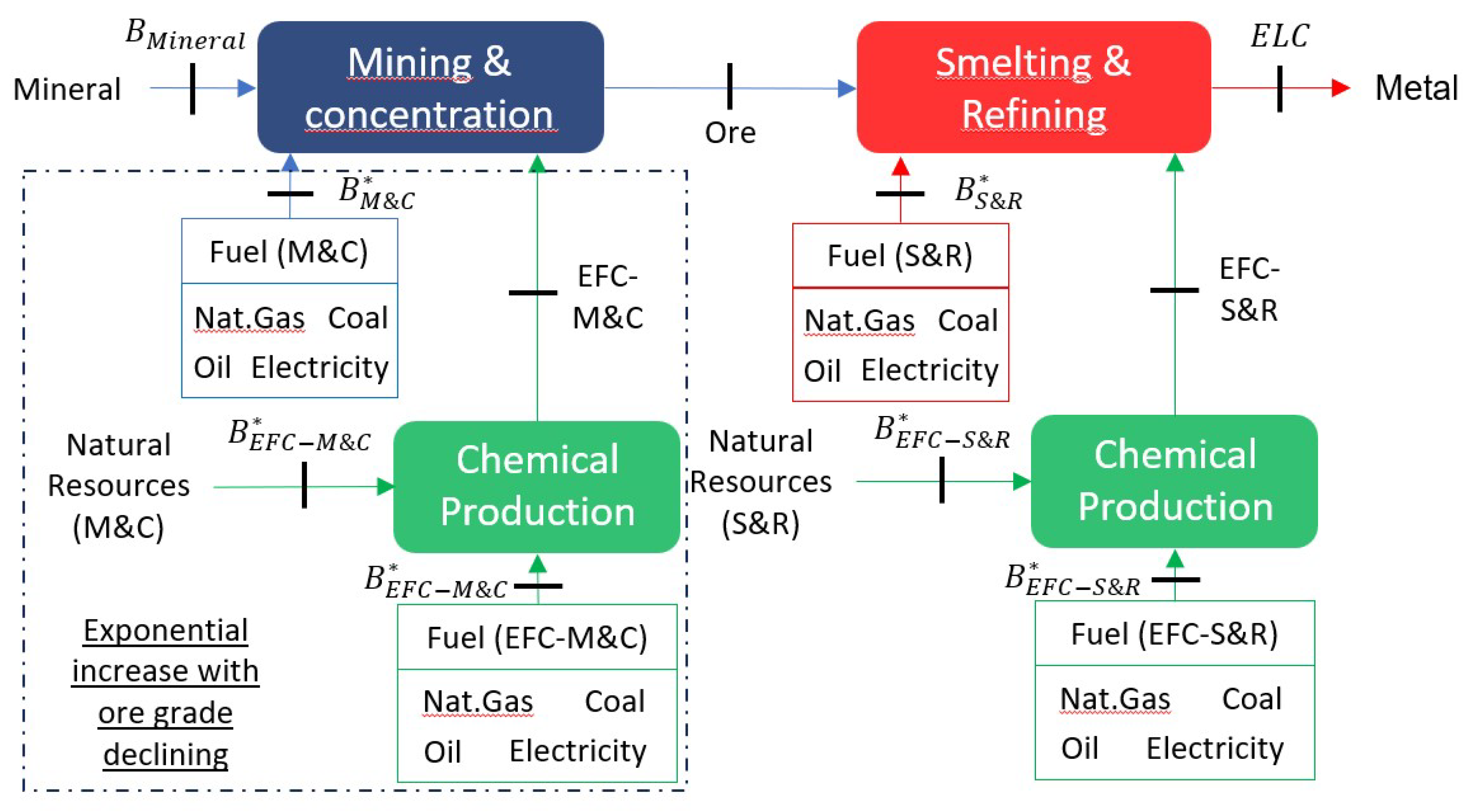

First, we show the total exergy cost of metals under different exergy allocation criteria, both for primary and secondary production. Secondly, we present the exergy cost of the previous section but disaggregated depending on the origin of the exergy. Finally, we show the complete cycle of metals assuming their use in PCBs, through Sankey diagrams to draw the main conclusions of circularity.

3.1. Exergy or Exergy cost allocations?

Table 4 shows the chemical exergy (

, obtained from [

34]),

and

(calculated in this article) and the ERC (from the reference [

44]) of the four metals studied. The four allocation criteria during the recycling process are applied using the values in

Table 4. The difference between

and

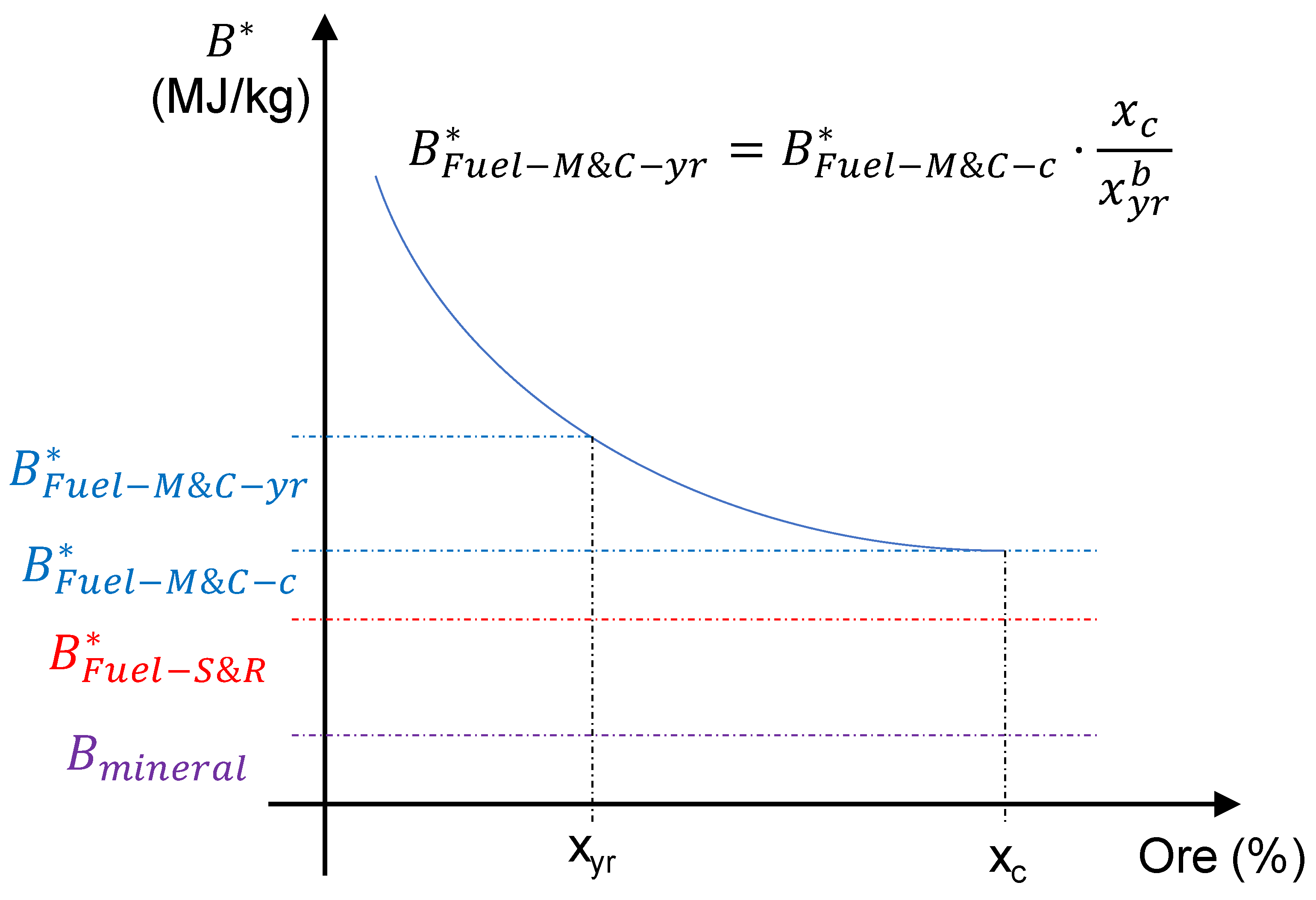

is the increase in exergy cost due to the decrease in ore grade expected between 2020 and 2050 (see

Figure 4) and the delining .

The exergy allocation under the exergy cost theory uses the exergy of the flows to allocate exergy cost [

19]. This criterion is meaningful in energy production plants since their exergy content determines the value of the flows since their function provides energy. However, using this criterion for products whose purpose is not energy production is not consistent.

Table 4 shows that copper has 10 times more exergy than gold since it is more environmentally reactive than gold. However, gold is much scarcer (and more valuable) than copper. On the other hand,

shows the exergy destroyed during the metal production processes, and the

shows the exergy that will be destroyed as the ore grade of the metals decreases, being a measure of the mineral scarcity [

32]. Conclusively, chemical exergy does not reflect the "usefulness" of metals, while

and

indicate the resources destroyed during the production process (either current

or future

), so their use is more consistent.

Table 5 shows the total exergy costs of primary production with primary exergy (

), and of the recycling process (

) analyzed in this study under the allocation criteria with exergy (

B), exergy life cycle cost (

) and Exergy Replacement Cost (

), for both 2020 and 2050. We observed that the primary exergy cost

of primary production is lower in 2050 than in 2020 in the cases of Cu, Ag and Pd, despite a decrease in their ore grade. This is because in 2050 we have assumed a strong penetration of renewable energies, according to the NZE scenario of the IEA [

2]. Renewable energies are much more efficient in the transformation of exergy [

20,

31], so despite an increase in

due to the decrease in ore grade, there is a decrease in the use of primary resources.

Table 6 shows the percentage of savings of secondary production with respect to primary production under the different proposed exergy criteria, i.e., it represents the ratio of

to

in

Table 5.

Table 6 shows the disadvantages of using the exergy criterion (B), since copper accounts for a very high percentage of the cost (represented by a saving between 31% and 54%), compared to a very high saving percentage for the case of gold (more than 99.99%). This is because the chemical exergy of copper is 10 times higher than gold (see

Table 4). The method showing the most balanced savings is the exergy cost method, with an almost constant saving of 97% for all metals. This result is consistent since we are comparing the recycling exergy costs

using the exergy life cycle cost allocation (

), with the primary exergy costs themselves

, which are calculated from

. Regarding the

criterion, we observe that Pd accounts for a higher percentage of the cost, with savings around 84%, while the rest of the metals present much higher savings. This result is caused because the ERC of Pd is very high (i.e. 8,983,377 MJ/kg,

Table 4) compared to the rest of the metals (i.e. 553,250, 7,371, and 292 MJ/kg for Au, Ag and Cu, respectively,

Table 4) due to the elevated scarcity of this element in nature.

The exergy cost allocation criteria ( and ) obtained the most satisfactory results. These criteria show the most balanced savings. Recycling aims to save the exergy of primary production; therefore, it is consistent to consider the life cycle of metals for allocation, through their exergy cost, both present () or future ().

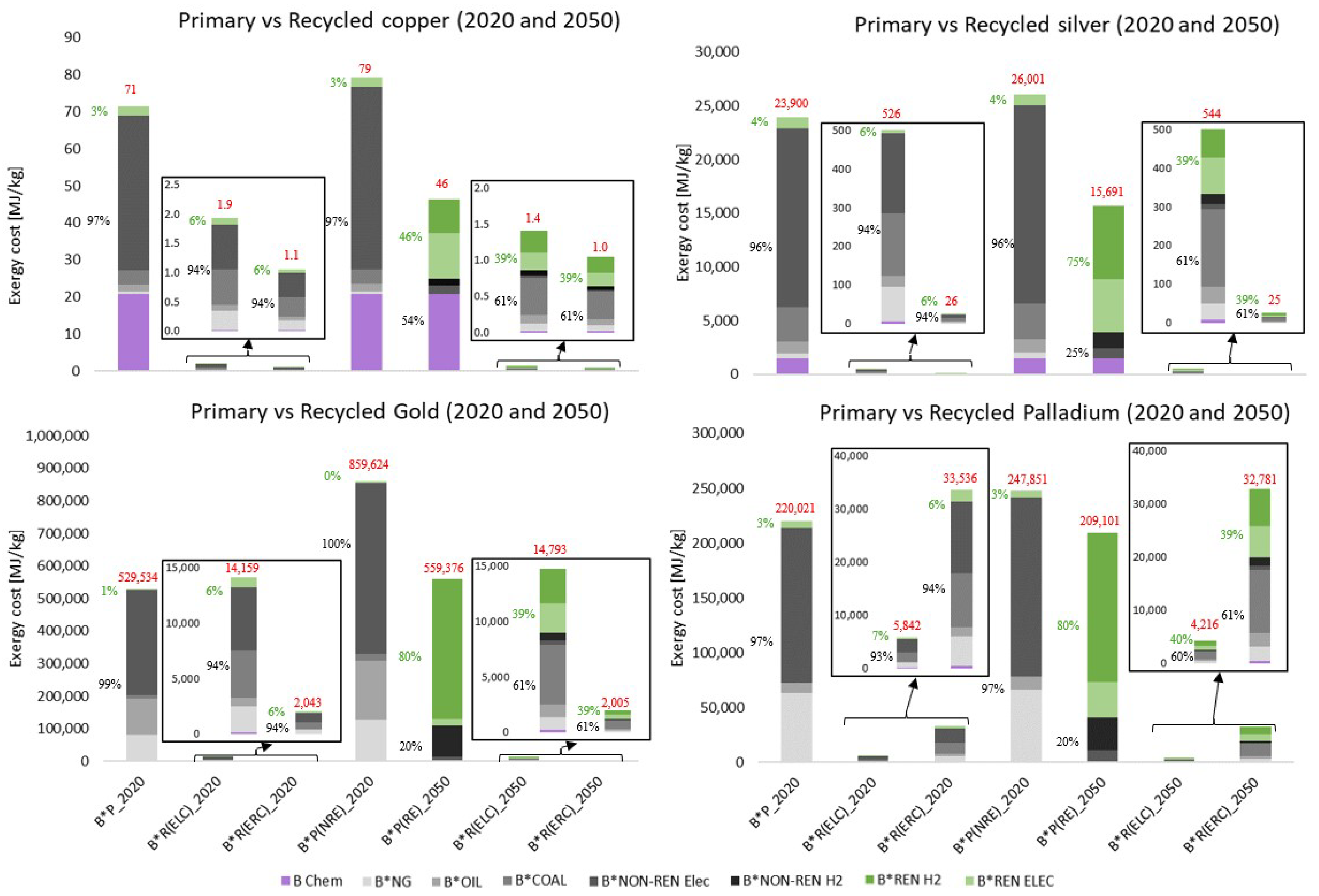

3.2. Non-renewable and renewable exergy cost of metals

Figure 5 shows the primary exergy cost of

Table 5 for the four studied metals, both primary production and recycling, disaggregated according to the origin of the exergy. We excluded the exergy allocation (B) since the most interesting ones were the exergy cost allocation (

and

), as explained in the previous section. We divided the exergy into the chemical exergy of minerals (

), the exergy cost of natural gas, oil, and coal (

,

,

, respectively), the non-renewable part of electricity and hydrogen (

), and the renewable part of the above (

).

All metals show very significant exergy savings when comparing primary and secondary production. The difference in exergy costs is high enough to zoom into the graphs to see the recycling composition. Disaggregation allows us to analyze the savings in non-renewable exergy. Thus, in the case of copper, 23.2-76.1 Non-Renewable MJ/kg are saved with respect to primary production. In the case of silver, the savings are between 3,310 and 25,011 Non-Renewable MJ/kg. Gold recycling saves between 96,249 and 854,313 Non-Renewable MJ/kg. Finally, recycled Pd saves between 9,649 and 239,068 Non-Renewable MJ/kg. Saving non-renewable exergy should be the priority of recycling since non-renewable exergy represents all resources that are not renewable, i.e., that cannot be replaced by nature in a short timescale.

The savings in non-renewable resources are also evident in primary production.

Figure 5 shows two primary production scenarios for 2050: one that maintains the 2020 energy mix (NRE, since it is mostly non-renewable energy) and another that is based on the IEA-NZE scenario [

2], with more renewables (RE). The comparison of these two scenarios allows us to appreciate the effect of the decrease in ore grade (lower in 2050 than in 2020) on the increase in the non-renewable energy costs of all metals when the energy mix is maintained (NRE scenarios). For example, it increases by 11.3% for Cu, 9.2% for Ag, 62.4% for Au, and 13.0% for Pd. However, considering the RE scenario, the non-renewable exergy cost decreases by 64% for Cu, 83% for Ag, 79% for Au, and 81% for Pd. The smaller decrease in the case of copper is due to the high chemical exergy of the mineral from which it is obtained: chalcopyrite.

The use of renewable energies in the recycling processes also reduces the non-renewable energy cost. Thus, in the case of copper, the exergy cost using allocation (1.9 MJ/kg) is reduced from 1.8 Non-Renewable MJ/kg to 0.9 Non-Renewable MJ/kg, representing a decrease of 52%. Using renewable energies to recycle silver also shows a notable decrease in the non-renewable energy cost of 32%. In the case of gold, the decrease in the exergy cost amounts to 32%, while for Pd, it is 54%.

Table 7 shows only the non-renewable exergy costs and their possible reduction from the case of primary extraction in 2050 with the current energy mix, representing the worst-case scenario.

Table 7 considers the allocation scenarios with the exergy life cycle cost (

) and all metals studied. It shows that implementing renewable energies in primary extraction would reduce the non-renewable exergy cost between 67% and 87%. Copper would be the metal with the lowest reduction due to the high chemical exergy of chalcopyrite that is destroyed in the production process. However, primary extraction would still require the extraction of natural resources from the mines, which would be depleted in the mining process, and their ore grade would decrease. Recycling would, therefore, save these resources for future generations. In addition, recycling, even with fossil technologies (

2020), would reduce the consumption of non-renewable resources even further, reaching reductions of 97.6% to 98.5%. However, the highest savings are obtained in the case of recycling using renewable energies. In this case, non-renewable exergy savings of 98.7% to 99.0% are achieved. Therefore, the most favorable cases are always those of recycling versus primary production, regardless of the energy sources used.

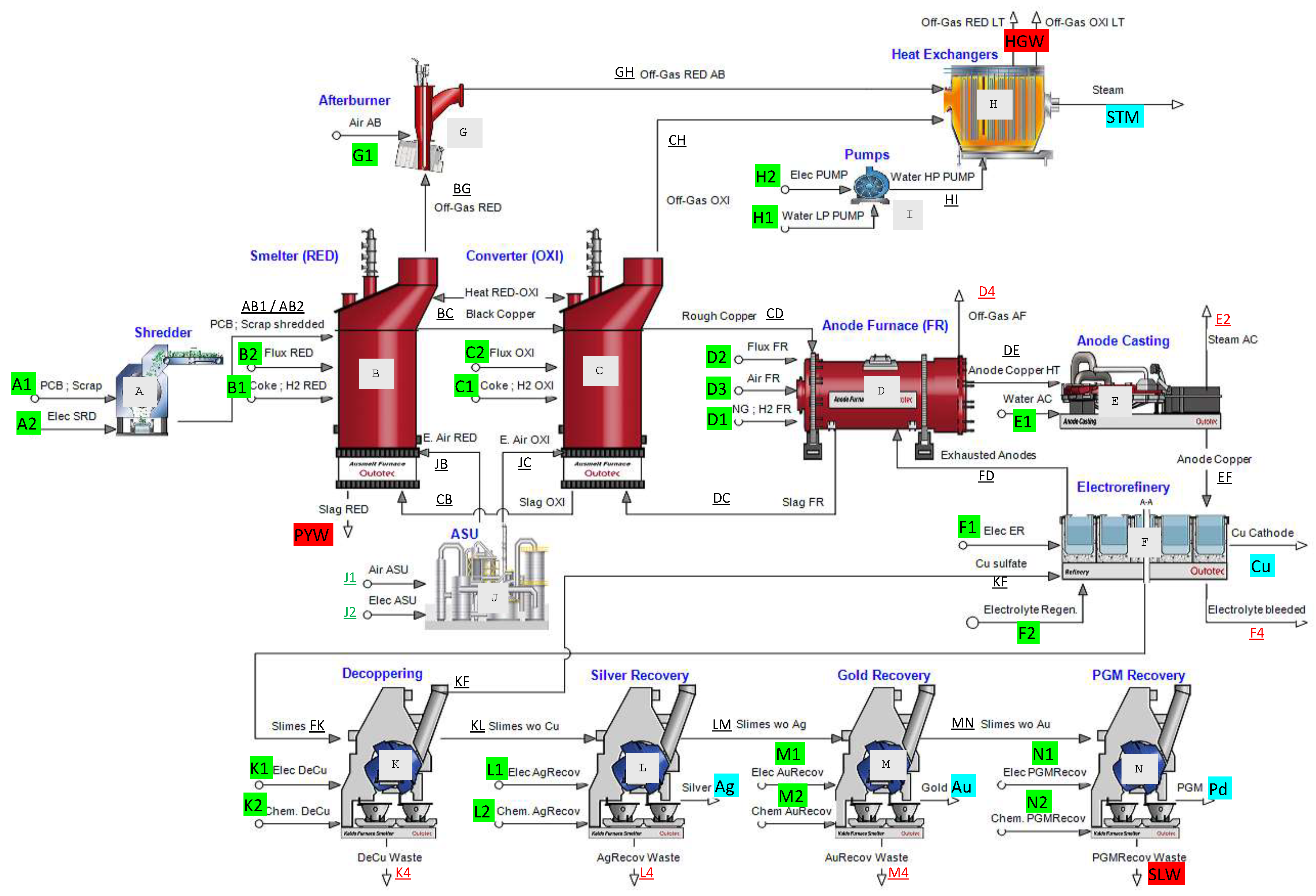

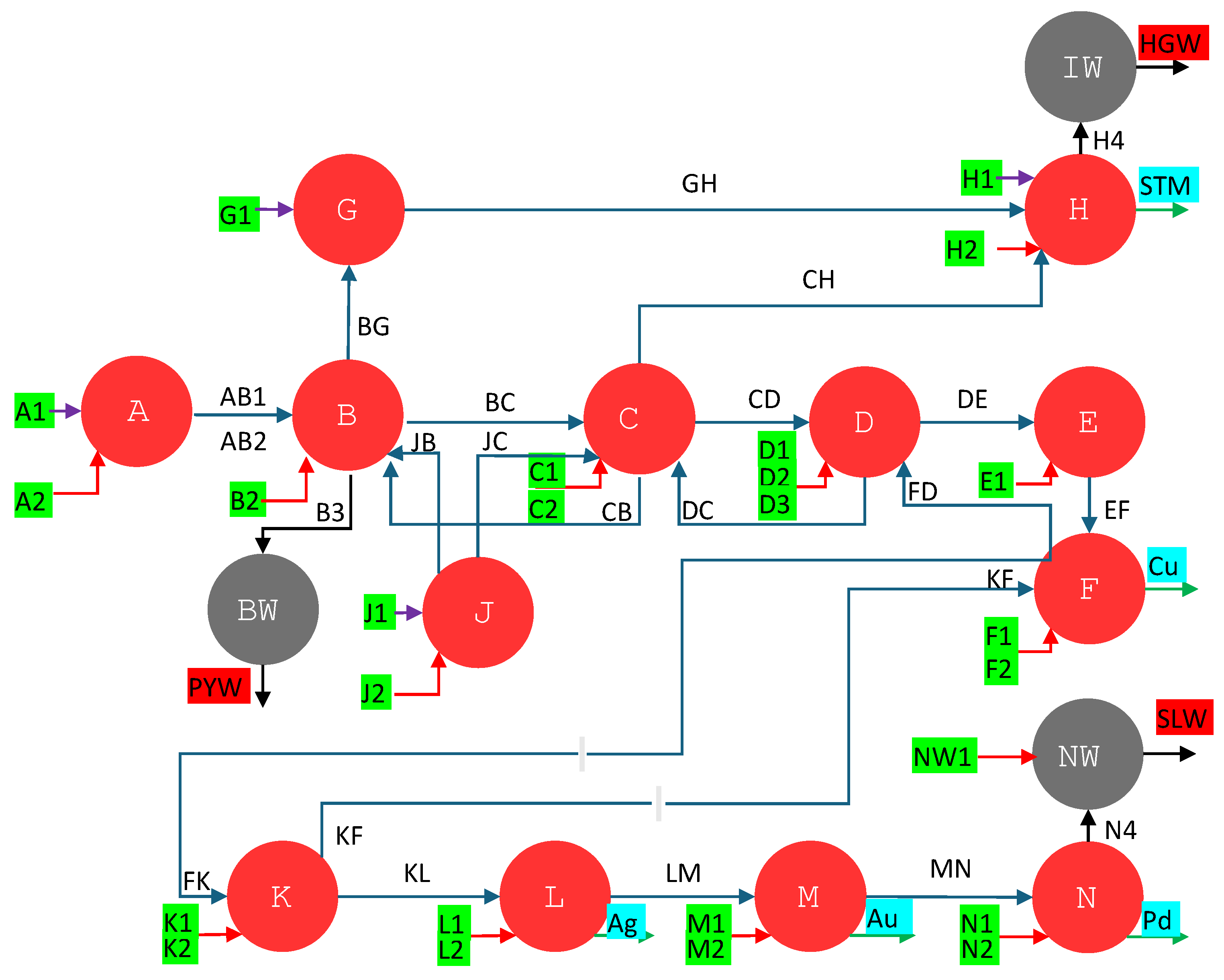

3.3. Circular thermoeconomics

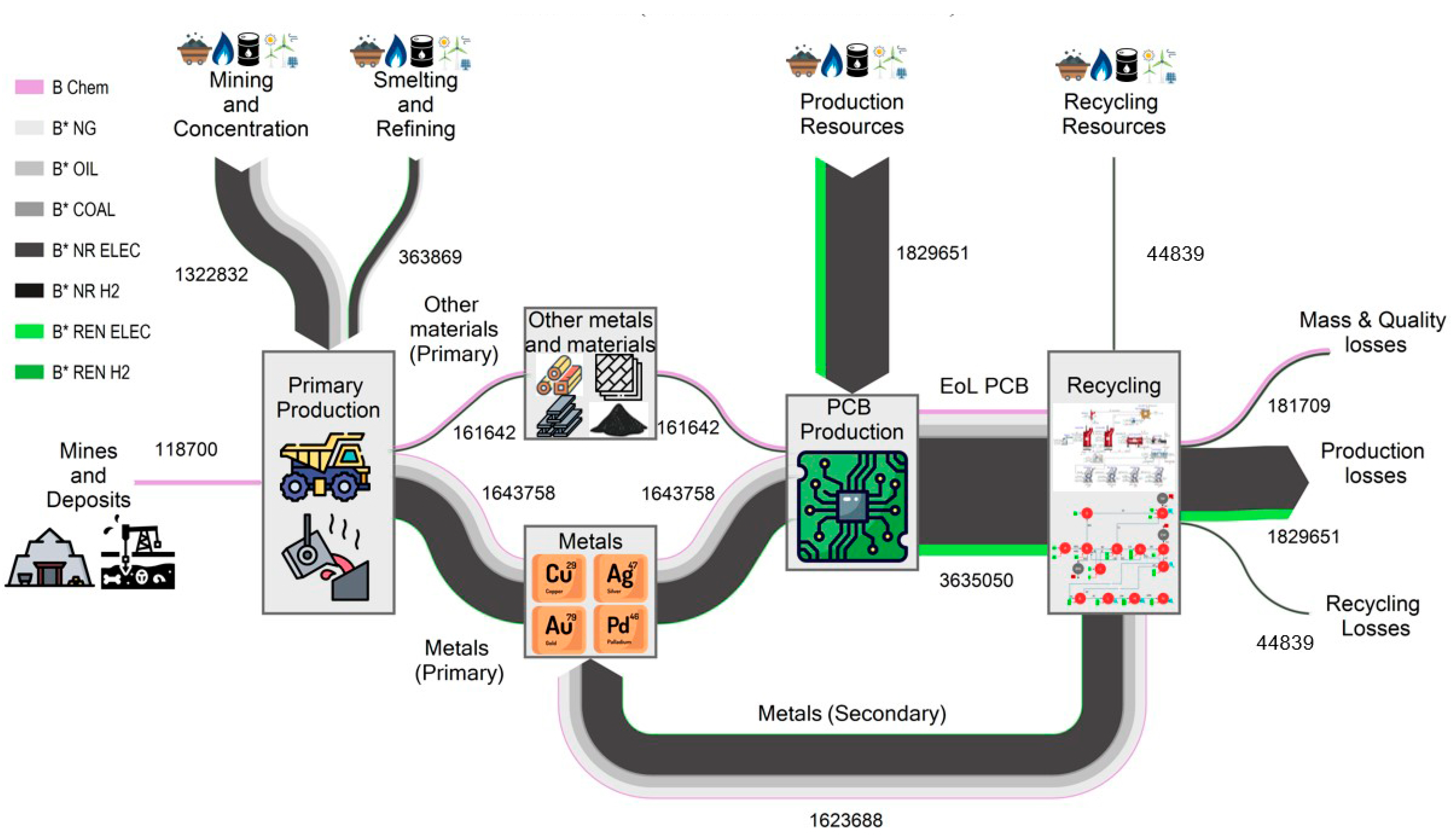

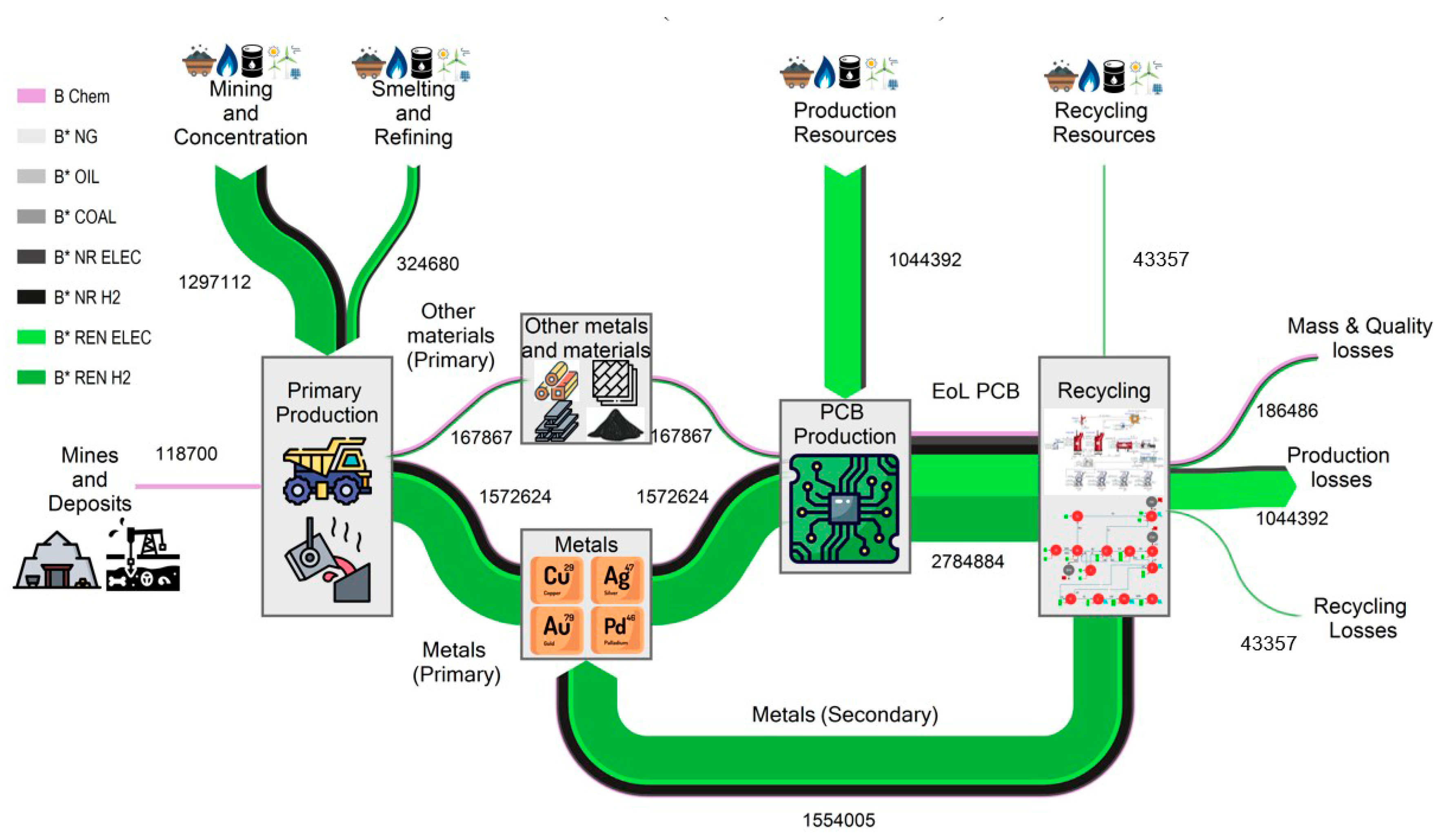

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show two Sankey diagrams showing the complete life cycle of the metals and materials embedded in the PCBs, from their extraction in the mine to their recycling, through the exergy cost (measured in kWh). The exergy cost is divided into categories therefore we can differentiate between its non-renewable and renewable contributions.

Figure 6 shows the 2020 case, which uses conventional resources, while

Figure 7 shows the 2050 scenario, which uses renewable resources in all stages.

The primary production stages distinguish between the chemical exergy from ores and fuels, the exergy cost of mining and concentrating the ores, and the smelting and refining exergy cost of transforming the ores into metals. We can observe that mining and concentrating costs are higher than smelting and refining. This is due to the significant contribution of gold mining, which accounts for 89% of the non-renewable exergy cost of this step. In the remaining metals (Cu, Ag, and Pd), the non-renewable exergy cost of smelting and refining represents the largest part: between 88.3% and 92.3%. On the other hand, chemical exergy from mines and deposits comes mainly from plastics embedded in PCBs (73%).

Once the metals and materials were produced, we distinguished between the exergy cost necessary to produce the four recycling metals: Cu, Ag, Au, and Pd, and the rest of the metals and materials. The metals selected for recycling comprise 91% of the entire non-renewable exergy cost, corresponding to 4.9% for Cu, 7.2% for Ag, 65.8% for Au, and 13.4% for Pd. Therefore, the recycling process is correctly focused since it can recover most of the exergy cost embodied in metals.

PCB production involves more resource consumption than raw materials since it is necessary to assemble all the components, such as integrated circuits, capacitors, and resistors. In this study, we have estimated the electricity needed for assembly at 87.5 kWh/kg of PCBs, obtained from the study of Yu et al. [

46]. This exergy consumption is almost of the same magnitude as that required for the primary production of the materials, representing 47% of the total non-renewable energy cost of production, the remaining 53% being due to the production of materials. This fact has important implications since all this exergy is destroyed during recycling because obtaining a new PCB will require consuming it again.

Once the PCB is produced, used and reaches the end of its lifetime (EoL PCB), we consider that it is collected and transported to the recycling plant we discussed in this study. However, not all EoL PCBs ends in plants suitable for recycling [

47]. Moreover, this is one of the main challenge for the circular economy, as much of the WEEE is either not collected or ends up in unknown locations [

9].

Recycling processes always consume resources. However, the non-renewable exergy cost of these resources is low compared to the exergy embedded in the materials recovered. In the case of 2020, 41,870 non-renewable kWh recovered 1,602,761 kWh embedded in copper, silver, gold, and palladium. Therefore, just taking the recycling view, we observe that they are very efficient processes since it is enough to invest 2.5% of non-renewable exergy to recover the remaining 97.5%. However, during the recycling process, there are more losses in addition to the resources used. On the one hand, all the exergy cost invested during assembly is lost since, in a new cycle, it will be necessary to consume this exergy cost. On the other hand, recycling processes are never 100% efficient due to mass (slag) and quality losses. Thus, if we take a complete view of the circular economy when recovering the 1,602,761 non-renewable kWh embedded in copper, silver, gold, and palladium, 1,795,200 non-renewable kWh are destroyed: mass and quality losses (9.8%), the exergy cost of recycling (2.3%) and the exergy cost of PCB production (87.9%). Therefore, considering only the recycling resources, it is enough to destroy 2.5% non-renewable exergy; however, when considering the complete life cycle, this exergy destruction amounts to 53%. In other words, in each circular economy cycle, more than half of the non-renewable resources are lost, despite considering 100% collections and having a process capable of recovering the most valuable metals (Cu, Ag, Au, and Pd), which make up 91% of the primary exergy cost of production.

One option to minimize the destruction of non-renewable exergy is to maximize the use of renewable energies in the primary production and recycling processes. However, renewable energies always have a non-renewable exergy cost due to their life cycle [

20,

21]. This scenario is depicted in

Figure 7. In this scenario, we observe a strong decrease in non-renewable exergy destroyed. Thus, the non-renewable exergy destroyed goes from 1,795,200 kWh in the 2020 case (

Figure 6 to 287,211 kWh in the 2050 case (

Figure 7), i.e., by using renewable energies, the non-renewable exergy cost is reduced by 84%. The distribution of these losses (285,797 kWh) differs from the 2020 case, with 45.2% coming from mass and quality losses, 45.9% from production, and 8.9% from recycling. The significant increase in mass and quality losses for the 2020 case (from 9.8% to 45.2%) is mainly because the recycling process uses plastics as fuel, and all its chemical exergy is lost in the process. On the other hand, as in the 2020 case, the percentage of exergy destruction throughout the life cycle remains significant. In the case of 2050, 287,211 non-renewable kWh are destroyed to recover the 326,281 kWh embedded in the materials, representing an efficiency of 47%.

In addition to recovering metals, steam is obtained during this process from the hot gases in the reduction and oxidation stages. The non-renewable unit energy cost of the steam produced is 0.21 kJ/kJ and 0.16 kJ/kJ for the 2020 and 2050 scenarios, respectively, much lower than steam produced in a conventional steam boiler or a cogeneration plant driven by fossil fuels.

The important difference between considering a metal-centric approach [

48] (with savings between 97.6-99.0%, depending on the metal considered,

Table 7) and product-centric approach [

48] (with only savings of 47-53%,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), reinforces the importance of accounting for the entire life cycle of products (in this case a PCB) and of designing specific recycling processes that minimize the loss of non-renewable exergy. On the other hand, the high losses (47-53%) of non-renewable exergy during recycling indicate that these processes should be delayed as much as possible, encouraging other measures such as reuse. Moreover, these results serve to measure the efficiency of the circular economy as a whole since losses during these processes are unavoidable. Therefore, the question arises: to what extent is it possible to refer to a circular economy if it is necessary to destroy non-renewable energy in order to return materials to the economy, even while maximizing renewable energies? Thus, Valero et al. proposed the term Spiral Economy [

49] with the aim of raising awareness of the inevitable losses of exergy during these processes, as established by the Second Principle of Thermodynamics.