1. Introduction

Growing industrialization and increased competitiveness have contributed to the growth in the volume of electronic products manufactured across a variety of market segments. Nowadays, large volumes of electronic products are sold worldwide. As a result of this growth, electronic waste has become a major problem in the disposal process, presenting itself as a critical and aggressive situation for the environment [

1]. This challenge, has triggered the in Brazil, in 2010, the Law 12.305/2010 that was enacted on the National Solid Waste Policy. This is acknowledged as the most specific concerning reverse logistics and recycling of WEEE. Its principle is to develop a reverse chain in order to promote shared responsibility for the life cycle of electrical and electronic equipment among the players in the chain. Article 33 of the aforementioned Law stipulates the obligation of manufacturers, distributors, traders, recyclers and importers to structure their reverse logistics systems for the return of post-consumer WEEE [

2]. Reverse logistics aims to provide a final destination for the return to the business cycle in an environmentally correct way, supported by legal terms.

It should be noted that in October 2019 also a sectoral agreement was signed, aiming at sharing responsibilities for WEEE management between manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers in São Paulo, Brazil. Oliveira Neto et al. [

3] mention that electronics manufacturers are responsible for implementing post-consumer WEEE reverse logistics, aiming at WEEE circularity through remanufacturing, repair, reuse, recycling and/or sale to the secondary market. But the manufacturers do not have the capacity to simultaneously carry out production and remanufacturing. As such, a common strategy has been to hire a WEEE manager responsible for allocating collection points, reverse logistics, receiving, disassembling, segregating and disposing of appropriate recyclers, as well as reseeeling for the secondary market.

Thus, it is considered relevant to incorporate the principles of Circular Economy in the reverse logistics operations associated with WEEE [

4], namely to consider the players in the reverse chain [

5], and seeking the circularity of WEEE through remanufacturing, repair, reuse, recycling and/or or sale to the secondary market. This is to be done [

3] in compliance with the regulation of local policies aimed at eliminating the disposal of WEEE in landfills, allowing the reduction of CO², in addition to improving the recovery rate, capacity of the facilities in relation to the total profit expected [

6]. By implementing cyclic material flows it is possible to limit the production flow to levels that nature tolerates, respecting its natural reproduction rates [

7], generating system sustainability [

8].

To promote the implementation of the principles of Circular Economy in the reverse WEEE chain – stimulated by the mandatory adoption of reverse logistics in São Paulo by the electronics sector - it is timely and relevant to conduct studies that can agument the knowledge about how to improve such systems [

3]. As such it In this context, it is important to carry out the simulation for economic and environmental optimization of the WEEE reverse network (manufacturers, waste managers, collection points and recyclers in São Paulo). With this, the use of technology for simulation will allow the development of optimal routes in economic and environmental terms. Simulation is an industry 4.0 technology, being used for real-time data analysis, offering opportunities for adjustments in complex systems through knowledge, information and accurate estimates about the system [

9], it is important to adopt information technology infrastructure [

10]. The use of the computational simulation approach with the circular economy for the economic and environmental optimization of a WEEE reverse chain generates economic and environmental benefits in operations [

11].

A systematic review of the literature was carried out, addressing 23 scientific studies selected for including the use of simulation approaches to identify the optimal way to optimize the WEEE reverse logistics network in economic and environmental terms, as shown in

Table 1. The fisrt step in the analsyis invoved the characterization of the computational simulations applied in the selected work. Among these, 9 studies used mixed integer linear programming for the simulation exercise - as shown by Achillas et al., [

12]; Qiang; Zhou [

13]; Kilic et al. [

14]; Bal; Satoglu [

15]; Elia et al. [

16]; Mar-Ortiz et al. [

17]; Gomes et al. [

18]; Alumur et al. [

19] and Assavapokee and Wongthatsanekorn [

20]. Also, other 3 studies used multicriteria objective linear programming, in line with Achilles et al., [

21]; Achillas et al., [

22] and Yu and Solvang, [

23]; and 2 studies dealt with discrete event simulation - Gamberini et al. [

24] and Shokohyar and Mansour, [

25]. One piece of esearch adopted linear and non-linear optimization problems, in discrete or continuous variables Dat et al. 2012[

26], and another used stochastic programming - Ayvaz et al. [

27]. There were also some studies that combined more than one computational simulation, namely the nonlinear gray Bernoulli model with the convolution integral NBGMC improved by Particle Swarm Optimization Duman et al. [

28], and multi-objective models are computed using the two-phase fuzzy compromise approach. Tosarkani et al. [

6], based on the Kriging Lv and Du method, [

29], multi-objective stochastic model and bi-objective mixed-integer programming model under uncertainties Moslehi et al. [

30], system dynamics and a mixed integer nonlinear programming model Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4], convolutional neural network-based quality prediction and closed-loop control Zhang et al. [

31] and agent-based modeling, system dynamics and discrete event simulation Guo and Zhong, [

5].

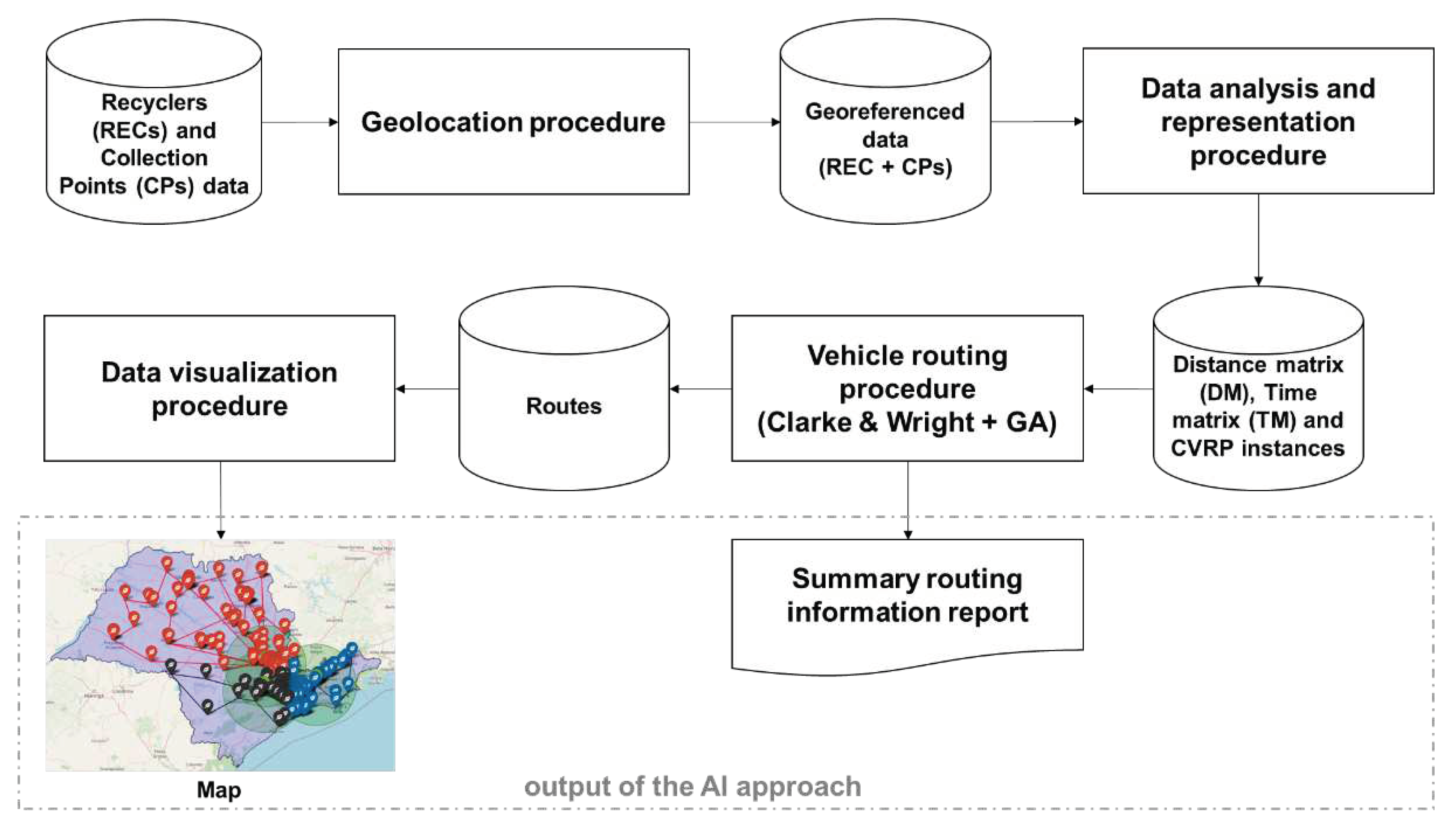

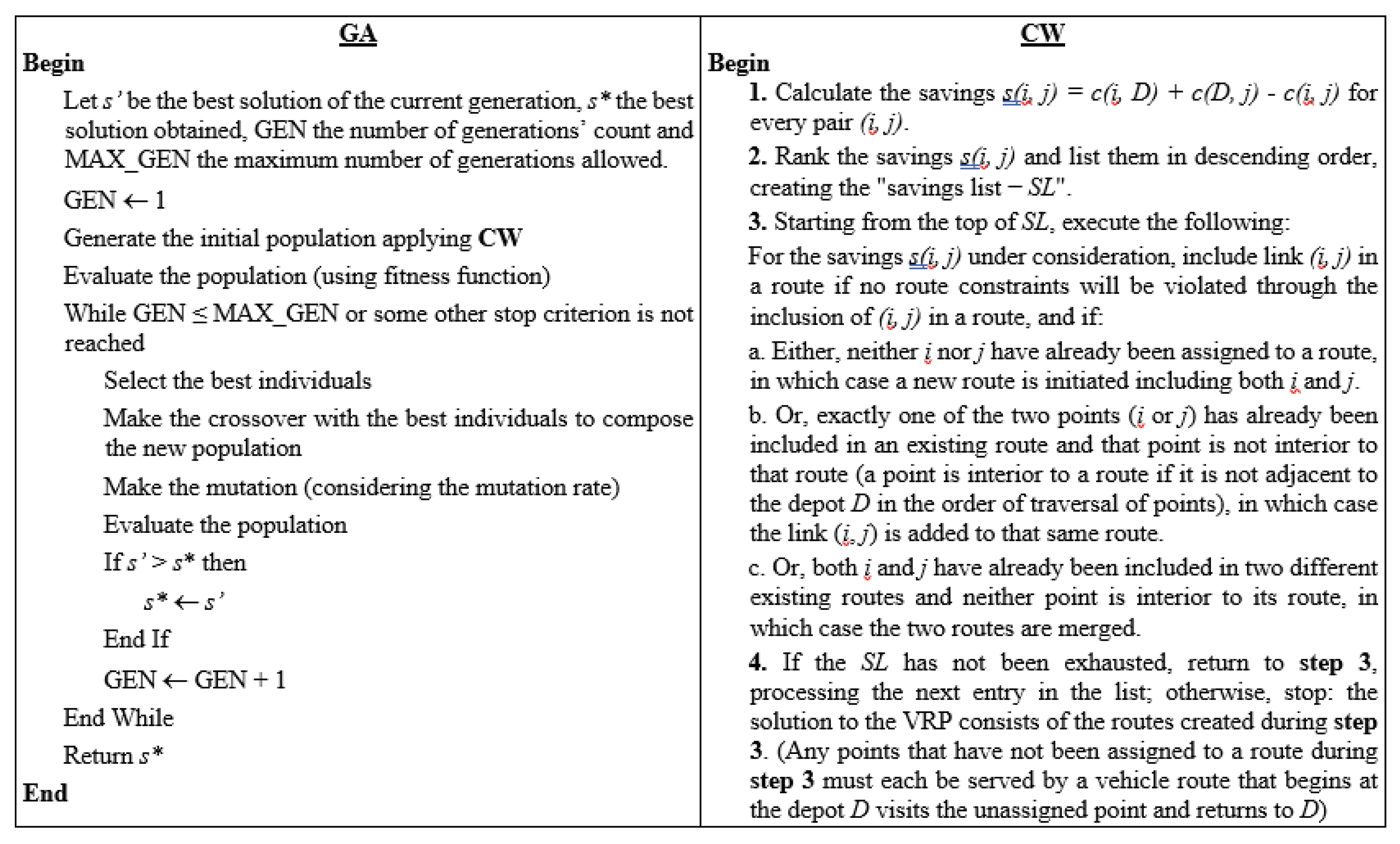

The first gap identified after the analysis of the published works was that no research applied simulation with computational intelligence techniques using artificial intelligence through genetic algorithm, for the economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network, considering manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers. It should be noted that the choice of techniques to compose the proposed simulation model to obtain better routes and destinations is based on the fact that both have shown good results (optimal or suboptimal solutions) for routing problems and other related problems of combinatorial optimization. In addition is also allows for handling a large number of constraints, including time windows and capabilities present in the problem Koç et al., [

32]. Nevertheless, the use of heuristic algorithms, such as the one by Clarke & Wright [

33], to populate the initial population of the Genetic Algorithm with feasible solutions has proven to be a good alternative for solving routing problems, as demonstrated in the works of Lima et al. [

34] and Lima & Araújo [

35].

A second step in the research analysis was understand the procedure used to present the environmental gains in the selected studies. In this regard, the studies that presented an environmental assessment – listed in

Table 1 - only offered a quantification in percentage using data extracted from the computer simulation. These studies generally emphasized the reduction of WEEE disposal in landfills and the reduction of CO², such as in: Gamberini et al. [

24]; Achilles et al., [

21]; Achilles et al., [

22]; Assavapokee and Wongthatsanekorn [

20], ; Shokohyar and Mansour, [

25]; Yu and Solvang, [

23]; Bal and Satoglu, [

15]; Elia, et al. [

16]; Duman et al.[

28]; Tosarkani et al. 2020[

6]; Llerena-Riascos et al. 2021[

4]; Lv and Du, [

29]; Moslehi et al.[

30]; Guo and Zhong, [

5]. From this, the second gap identified was that no research evaluated the reduction of environmental impacts in the abiotic, biotic, and water dimensions, using the Material Intensity Factor, which is a relevant tool for global assessment of the minimization of environmental impacts, not just using percentage data.

Thirdly, the procedure used by the surveys to develop the economic evaluation was analyzed. Surveys use only percentage data to measure transportation and storage cost savings and profitability without a detailed explanation of the data. Thus, the third research gap addressed in this study consists in the fact that no research was identified that presented the calculation of cost and time reduction in detail, in addition to measuring the improvement in the volume of vehicles, being a primordial aspect in the optimization and orientation of transport managers. It should be noted that complex optimization scenarios without detailing make it impossible for managers to apply them in practice.

The fourth aspect analyzed in the research was the country of application of computer simulations for optimization of the WEEE reverse chain. Five surveys were carried out in China by Dat et al. [

26], Qiang and Zhou [

13], Yu and Solvang [

23], Lv and Du [

29] and Guo and Zhong [

5]; three surveys conducted in Greece by Achillas et al., [

12], Acillas et al., [

21], Acillas et al., [

22]; three in Türkiye by Ayvaz et al. [

27], Kilic et al. [

14], Bal and Satoglu [

15]; two in Italy by Gamberini et al. [

24] and Elia et al. [

16]; two studies in the USA by Assavapokee and Wongthatsanekorn [

20] and Duman et al. [

28]; two in Iran by Shokohyar and Mansour [

25] and Moslehi et al. [

30] and one each in Spain by Mar-Ortiz et al. [

17], Portugal by Gomes et al. [

18], Germany by Alumur et al. [

19], Canada by Tosarkani et al. [

6], Colombia by Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] and Belgium by Zhang et al. [

31]. Thus, the fourth gap for research was the lack of studies carried out in Brazil and mainly in São Paulo on the use of simulation for economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network, considering manufacturers, waste managers, collection points and recyclers.

The fifth content analysis carried out on the articles concerned the use of the circular economy approach in research. Tosarkani et al. [

6] mentioned circular economy only in relation to the passage of Bill 151 and the development of circular economy strategies in Ontario, Canada, greater attention was directed towards recycling electronics (OES annual report, 2017). Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] incorporated the principles of circular economy to maximize economic benefits in relation to environmental ones and Guo and Zhong [

5] mentioned circular economy superficially, in addition to not performing optimal optimization in the WEEE reverse chain. Therefore, no research on circular economy was identified that evaluated the environmental impact and economic gain with details of the adoption of computer simulation for optimization of the WEEE reverse chain, denoting the fifth gap to be explored in this study. Hidalgo et al. [

11] concluded that the use of simulation for the management of WEEE in the reverse network does not guarantee eco-efficiency, because it is important to use the circular economy approach to obtain economic and environmental benefits in operations, because it is about promoting the circularity of WEEE.

Therefore, the application of computer simulation using artificial intelligence with the use of genetic algorithm for economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network, considering manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers to promote circular economy, was, at the date of the study relatively unnadressed in the scientific literature,. The exploratory analysis of the literature allowed for the identification of five important research gaps, critical for both theory and managerial practice. The following research question was formulated: How can the application of simulation and computational intelligence techniques, with the use of artificial intelligence and genetic algorithm, for economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network (manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers of São Paulo) promote circular economy?

The study contributes to this research gap, and highlights that the optimal configuration of the reverse WEEE network should promote economic gains and reduction of environmental impacts for the actors in the network (manufacturer, waste manager and recyclers in São Paulo). The economic gains are evaluated considering the opportunity to reduce transport costs. The reduction of environmental impacts is measured by evaluating the intensity of the material in the abiotic, biotic, water, land and air compartments in relation to the minimization of fuel consumption and CO² emission. This study is justified by the contribution to theory, organizational practice and society.

2. A simulation Approach for Optimizing the WEEE Reverse Logistics Network

A preliminary overview of the extant literature is organized in

Table 1, displaying the research work that used computer simulation to identify the optimal path for optimizing the WEEE reverse logistics network in economic and environmental terms. Three surveys carried out in Greece, three in China, three in Turkey, two in Italy, and one in each, considering Spain, Portugal, Germany, USA and Iran, were identified. All surveys aim to reduce transport costs and half aim to reduce CO² emissions. Likewise, in China additional five studies were identified. Dat et al. [

26] developed a model to minimize the total cost of the WEEE recycling network in China, which is the sum of the transport cost, operation cost, fixed cost, disposal cost minus the revenue generated from the sale of recyclable materials. and renewables and components. Also based on the proposed model, the ideal locations of the facilities and the material flows in the reverse logistics network were determined. Qiang and Zhou [

13] developed a robust mixed integer linear programming simulation model for WEEE reverse logistics network to optimize the handling process, which was affected by recovery uncertainty based on risk preference coefficient and risk coefficient. penalty diverted from restrictions, that could allow decision makers to fine-tune operating system robustness and risk preferences. The result showed an opportunity to reduce transport costs.Yu and Solvang [

23] developed a stochastic mixed integer-programming model to design and plan a multi-source, multi-echelon, capable and sustainable reverse logistics network for managing WEEE under uncertainty. The model takes into account economic efficiency and environmental impacts in decision-making, and environmental impacts are evaluated in terms of carbon emissions. Lv and Du [

29] developed a simulation based on the Kriging method to predict the amount of WEEE returned in reverse logistics in China. The proposed model can accurately predict the amounts of WEEE returned from unknown locations, as well as those from the entire area through data from the known location, which is important for compliance with environmental legislation. Guo and Zhong [

5] applied Agent based modeling, system dynamics and discrete event simulation is constructed in China for the simulation of a closed-loop supply chain based on the Internet of Things, allowing to generate more profit and can reduce more greenhouse gas emissions and contamination by heavy metals, in addition to offering protection of people from diseases caused by heavy metals present in WEEE. It should be noted that this study mentions adequate management of WEEE through the use of IoT, installation of sensors in the truck, barcode on the product and trash can on the sidewalk and the pre-selection center, in addition to the technology adopted by the manufacturer. However, this study does not perform optimal optimization and mentions circular economy superficially.

Three works in Greece were identified. Achillas et al., [

12] used the mixed integer linear programming model to adapt the model in order to optimize and minimize total costs of transporting WEEE between collection points and recycling units, optimizing the use of containers and storage containers of WEEE, cost reduction on WEEE storage deposits in Macedonia and Greece. This suggests that some network nodes (i.e. collection and recycling points) can be strategically modified, in such a way as to promote considerable cost reductions in the WEEE reverse logistics network. Achilles et al. [

21] adopted multicriteria objective linear programming to identify the optimal location for the installation of waste recycling plants for two cities in Greece: Messologhi and Kavala. The study aimed to address legal standards and goals for the collection of WEEE. Specificallly the goal was to minimize the environmental impact by reducing the possibility of WEEE being dumped in landfills, in addition to reducing pollutants from fossil fuels (CO²) in the atmosphere. Moreover it documented the generation of an economic advantage of 235,000 Euros due to the recycling and reuse of WEEE and the minimization of fuel consumption. Achillas et al., [

22] used multicriteria objective linear programming for weighted optimization of WEEE collection and recycling processes in order to minimize total logistic costs and reduce fuel consumption in the region of Central Macedonia, Greece. The results showed a 5% reduction in CO² pollutants (from fossil fuels), in addition to an economic gain of 545 thousand Euros,

Two surveys were carried out in Italy. Gamberini et al., [

24] developed discrete event simulation and lifecycle analysis for the optimization of the WEEE transport network in northern Italy. The authors used vehicle routing methods and heuristic procedures for creating different scenarios for the system, simulation modeling to obtain solutions that satisfy technical performance measures, life cycle analysis to assess the environmental impact of such solutions, multicriteria decision methods to select the best choice under the joint technical and environmental perspective. With this, opportunities to reduce transport costs were identified, in addition to minimizing CO² emissions in the environment. Elia et al. [

16] do not mention aroute optimization considering the reverse chain in terms of recycling and reuse. They only mention ollection and direct option or determination of another path in Italy. With this, the simulation was adopted to compare different alternatives for a WEEE collection service. A dynamic collection scheme (i.e. with varying collection frequencies based on the actual level of waste stream) is simulated in two different logistical configurations, i.e. one based on direct connection and the other based on a network. The impact of the adoption of electric vehicles is also evaluated. Alternatives are compared using key economic and environmental performance indicators to assess the level of sustainability. The simulation was adopted to compare different alternatives for a WEEE collection service. A dynamic collection scheme (i.e. with varying collection frequencies based on the actual level of waste stream) is simulated in two different logistical configurations, i.e. one based on direct connection and the other based on a network. The impact of the adoption of electric vehicles is also evaluated. Alternatives are compared using key economic and environmental performance indicators to assess the level of sustainability. Simulation was emplyed to compare different alternatives for a WEEE collection service. A dynamic collection scheme (i.e. with varying collection frequencies based on the actual level of waste stream) is simulated in two different logistical configurations, i.e. one based on direct connection and the other based on a network. The impact of the adoption of electric vehicles is also evaluated. Alternatives are compared using key economic and environmental performance indicators to assess the level of sustainability. one based on direct connection and one based on a network. The impact of the adoption of electric vehicles is also evaluated. Alternatives are compared using key economic and environmental performance indicators to assess the level of sustainability. one based on direct connection and one based on a network. The impact of the adoption of electric vehicles is also evaluated. Alternatives are compared using key economic and environmental performance indicators to assess the level of sustainability.

Assavapokee and Wongthasanekorn [

20] used the mathematical model of mixed integer linear programming for process optimization in terms of the most adequate choice for the implantation of recycling units in Texas – USA through discrete variables, representing the decisions such as locations and capacity allocation. Overal they also addressed decisions about the material flows of the reverse logistics network. The model considered the obsolescence estimates for the products (e.g. computers, monitors, televisions), the sales volume of the products and analyzed the logistics transport costs. This reduced the logistics costs of transporting waste in terms of fuel and reduced storage costs for waste deposits, in addition to the percentage indication of the reduction in the amount of CO².

Other authors [

28] proposed nonlinear gray Bernoulli model with convolution integral NBGMC(1,n) improved by Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with the aim of presenting a new prediction technique for e-waste for the US with multiple inputs in the presence of limited historical data. It was concluded that it is possible to improve decision-making in reverse logistics planning, allowing the proper collection, recycling and disposal of electronic waste, generating elimination of WEEE disposal in landfills and CO² reduction.

Shokohyar and Mansour [

25] designed a WEEE recovery network to determine the best locations for collection centers and also recycling plants for total WEEE management in Iran, so that the government can simultaneously trade-off between environmental issues and economic and social impacts. Moslehi et al. [

30] applied the multi-objective stochastic model. bi-objective mixed-integer programming model under uncertainties with the aim of modeling the reverse logistics process of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) to Iran. A case study of an electronic equipment manufacturer in Esfahan, Iran, was included, making it possible to minimize the disposal of WEEE in landfills and reduce CO², in addition to reducing transportation costs.

Mar-Ortiz et al. [

17] developed a survey in Spain with the aim of optimizing the design of the WEEE logistics network. Thus, firstly, an installation location problem was formulated and solved using a mixed integer linear programming; in the second phase, a new integer programming formulation for the corresponding heterogeneous fleet vehicle routing problem is presented, and an economics-based heuristic algorithm is developed to efficiently solve the related collection routing problems; in the third phase, a simulation study of the collection routes is carried out to evaluate the overall performance of the recovery system. The results show a good performance of the proposed procedure, and an improved configuration of the recovery network in relation to the one currently in use,

Gomes et al. [

18] developed a generic mixed integer linear programming model that was proposed to represent this network, which is applied to its design and planning in Portugal, where the best locations for the collection and sorting centers are chosen simultaneously with the definition of network tactical planning. Some analyzes were carried out to provide more information on the selection of these alternative sites. The results support the company's strategic expansion plans for the opening of a large number of centers and for their location close to the main sources of WEEE, with a main focus on reducing operating costs. Alumur et al.

Tosarkani et al. [

6] applied efficient solutions of the multi-objective model are computed using the two-phase fuzzy compromise approach, aiming to optimize and configure a Canadian WEEE reverse logistics network, considering the uncertainty associated with fixed and variable costs, the amount of demand and return and the quality of returned products. The study mentions that with the passage of Bill 151 and the development of circular economy strategies in Ontario, greater attention has been directed towards recycling electronics (OES annual report, 2017). With this, it is necessary to implement a reverse chain for environmental compliance to reduce pollution and eliminate the disposal of WEEE in landfills, allowing the reduction of CO², in addition to improving the recovery rate,

Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] applied simulation using system dynamics and mixed integer nonlinear programming to design sustainable policies for WEEE management systems, incorporating circular economy principles to maximize economic benefits in relation to environmental ones. This led to a 33% increase in profit and a 65% increase in environmental benefits. It should be noted that despite mentioning the circular economy, it does not quantify the economic and environmental gains based on a real case, presenting percentage data.

Zhang et al. [

31] applied computer simulation using Convolutional Neural Network-based quality prediction and Closed-Loop control, with the aim of presenting a closed-loop capture planning method for the random collection of WEEE products in Belgium, reducing costs in the collection and pre-processing process.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. The Reverse Chain of WEEE in Brazil

After the interviews with 4 electronics manufacturers located in Brazil, it was found that they did not have information on the players in the reverse WEEE chain, which includes a survey of the volume collected, locations of recyclers and collection points in the region of São Paulo. The manufacturers mentioned that after the approval of the sectoral agreement in 2019, requiring the implementation of WEEE reverse logistics, a joint decision was taken between the manufacturers on hiring a WEEE manager, mentioning that she would have all the necessary information. The manager mentioned that she was unable to produce and handle WEEE simultaneously, due to lack of operational capacity. Thus, it was necessary to focus on manufacturing, its core competence.

In this interview, it was identified that the WEEE manager hired 3 recyclers for dismantling, recycling, preparation for the sale of WEEE to the secondary market. The WEEE manager also referred us to a manager from one of the recyclers, emphasizing that he knew the process as a whole, including the estimated values needed to carry out the simulation. Thus, consequently, an interview was conducted in São José dos Campos (R1).

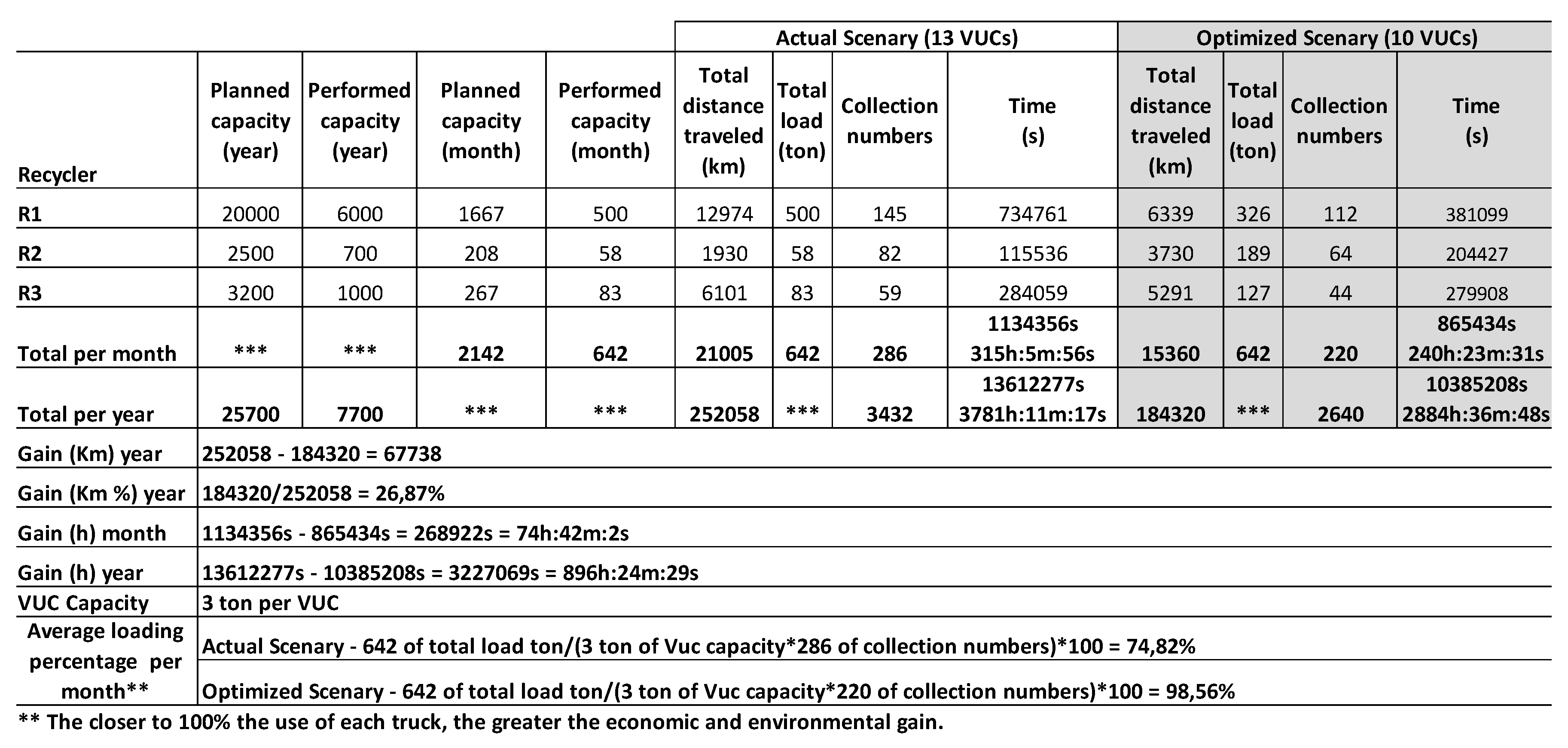

In this interview, the locations of recyclers and collection points were verified, as well as the volume of WEEE collected, as shown in

Table 4. R1 has a planned capacity of 20,000 ton/year and a realized capacity of 6,000 ton/year. Recycler 2 (R2) is located in Sorocaba, with a planned capacity of 2500 ton/year and realized capacity of 700 ton/year and Recycler 3 (R3) is installed in Nova Odessa (R3) with a planned capacity of 3200 ton/year and realized capacity of 1000 ton/year. The location of 554 collection points was also identified, as well as the volume of WEEE collected, ranging from 8 to 60 ton/year, which are distributed throughout Brazil. In this context, knowledge of the WEEE reverse chain used in São Paulo is new to the scientific literature. Also, the practical structuring of this WEEE reverse chain through simulation will contribute to the strategic actions of the circular economy, which aims to reduce, recycle, reuse and recover as much WEEE as possible. However, it will not be possible to promote close-loop, an aspect encouraged by circular economy actions, but it will be optimized as much as possible, and the computational technique can be applied over time, always looking for the most optimized scenario. This finding denotes a relevant theoretical and practical contribution because the research by Guo and Zhong [

5] carried out in China, Tosarkani et al. [

6] in Canada and Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] in Colombia, only used the term “circular economy”, but did not show the application with details showing the environmental and economic benefits, as this study elucidates.

Another aspect observed was that the WEEE manager does not have its own fleet of trucks for collection. She outsourced the transport to a carrier specializing in reverse logistics. The required vehicle was a VUC truck with a capacity of 3 ton because most collections are carried out in the metropolitan region and in cities at collection points (stores, malls, parks, large and small supermarkets, etc.), not allowing the circulation of trucks with capacities greater than 3 tons. This finding shows that the manufacturers outsourced the reverse logistics of WEEE to a waste manager, which considers 3 recyclers and 554 collection points located in São Paulo. Thus, the manufacturers considered WEEE reverse logistics as a support activity and therefore outsourced it, innovating the state of the art.

However, even when interviewing the WEEE manager and recyclers, it was not possible to identify the current scenario with the details of the routes carried out by the VUCs, denoting the lack of global knowledge of the process, which could lead to future problems. In addition, the lack of knowledge of the environmental and economic gains of this action, related to the circular economy strategy.

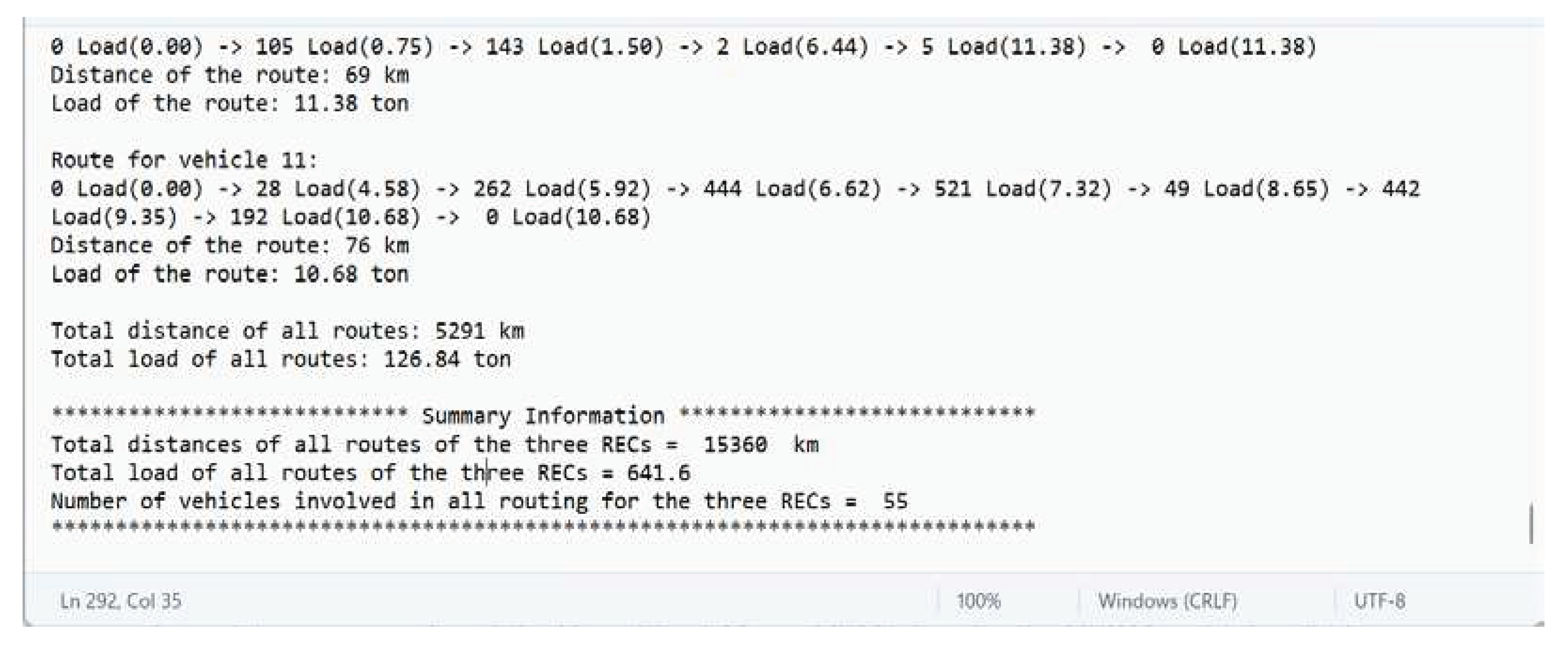

In this context, the interviewee mentioned that the carrier performs 286 collections per month with 13 VUCs, considering 22 working days including vehicle rotation, summing up 21005 km driven. R1 performs 132 collections of 500ton per month with 12974 km. The R2 performs 76 collections of 58tons per month, consuming 1930 km. The R3 transports 83tons through 53 collections over 6101 km. This information formed the current scenario, which considers the 3 recyclers and 554 collection points (

Table 5). Thus, based on this information, a computational tool was applied to simulate the WEEE reverse chain, making it possible to present the optimization in economic and environmental terms.

4.2. WEEE Reverse Chain Simulation for Economic and Environmental Optimization

Initially, location information was entered for plotting the map, and the association of each collection point to one of the 3 recyclers was assigned considering the shortest distance between them, respecting the limit of the recyclability capacity of each recycler and the capacity of the vehicle for transport. Thus, if a collection point is closest to a recycler and it has reached maximum capacity, then that collection point is associated with the recycler with the second shortest distance.

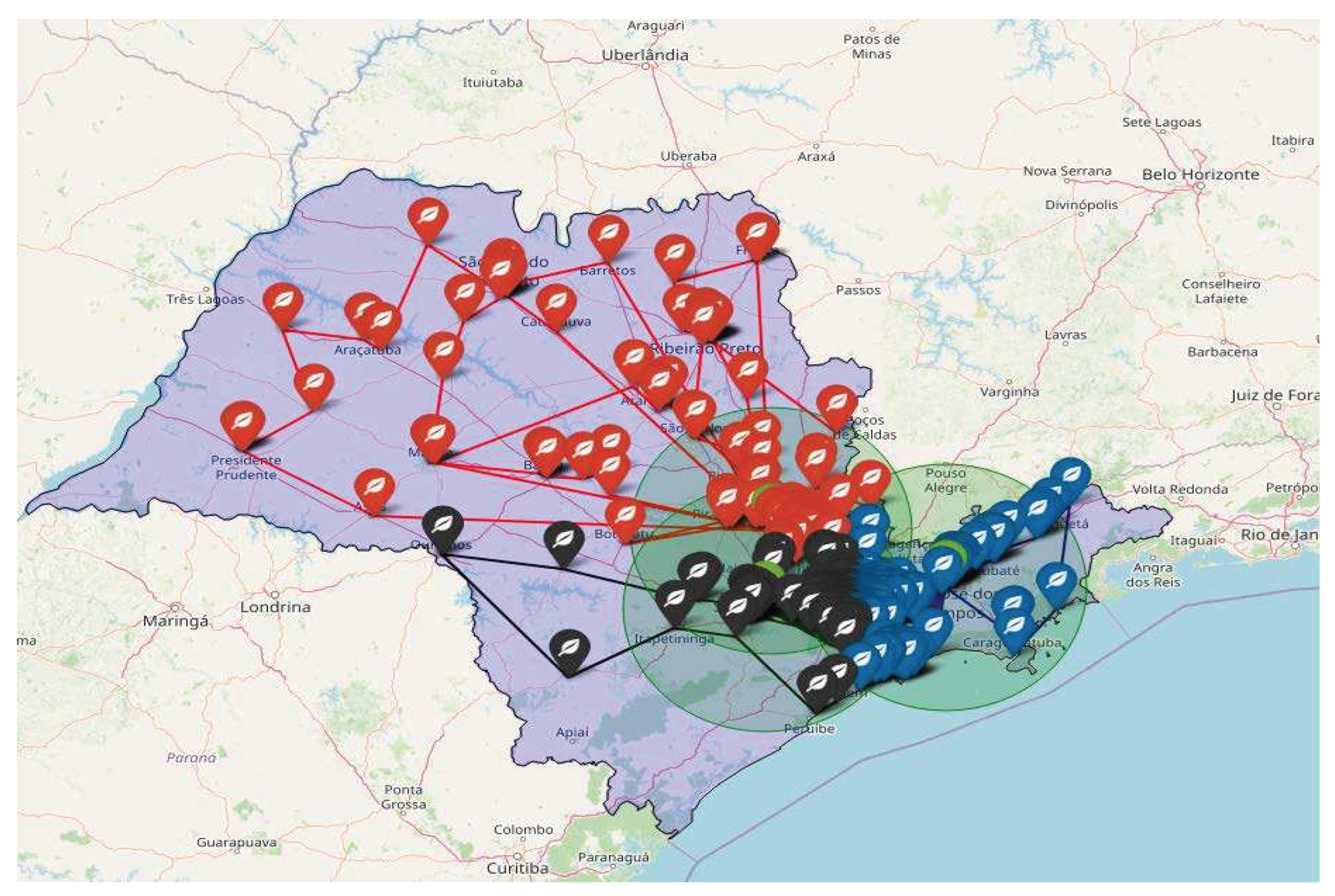

The map of the State of São Paulo shows 3 recyclers in green, being related to R1 of São José dos Campos with 270 collection points (blue), R2 of Sorocaba with 164 collection points (black) and R3 of Nova Odessa with 120 points of collection (red), as shown in

Figure 5. It should be noted that distance and real times computed using OSRM were considered. This finding is also innovative for research, for example, Achillas et al. [

12], Achilles et al. [

21], Achilles et al. [

22], Ayvaz et al. [

27], Kilic et al. [

14], Duman et al. [

28], Tosarkani et al. [

6]. Research on the subject usually only presents complex optimization scenarios directly using artificial intelligence, but they do not explain in detail the construction of knowledge and mainly do not mention that the adoption of WEEE reverse logistics is a strategic action at the meso level of the circular economy. Thus, an operations manager could easily understand the process performed for optimization, enabling its replication in organizational practice, contributing to actions to reduce, recycle, reuse and recycle in the circular economy.

Table 5 displays the comparison between the current scenario and the optimized scenario. The current scenario was identified in the interview as mentioned earlier, while the optimized scenario was extracted from the simulation using AI. It was found that it was possible to optimize the number of collections from 286 to 220, considering 642 tons per month. This reduced 26.87% of the distance covered from 21005 km to 15360 km in the WEEE collection process at collection points for recyclers. It should be noted that the solution to the problem investigated in this study was through the meta-heuristic model, which considers the process of evolutionary computation of economies and minimization of environmental impacts. These savings represent how much distance or transportation costs can be relatively optimized, reduced, grouping themselves to the nodes of the networks and their respective destinations. The reduction of the environmental impact represents the route that consumes less fuel, as well as reuses more WEEE, reducing environmental impacts in the abiotic, biotic, water and air compartments. An important finding was that the carrier fulfilled individual orders without a schedule for WEEE removal. Thus, the trucks returned most of the time with space to store more WEEE. In the optimization process, it considered the opportunity to develop the collection schedule, where each collection process the VUC passes through several points until it loads the truck as much as possible. With this, this study presents the detail of the researched scenario, contributing to the literature and organizational practice,

Thus, the optimization of 13 VUCs to 10 VUCs for the operation, considering that to collect 642 tons of WEEE per month in 22 working days, it is necessary to collect 29 tons per day in 10 VUCs of 3 tons each. As a result, it generated a reduction of 67,738 kilometers driven per year, representing a gain of 26.87%. In addition to the reduction in operating time from 315h:5m:56s to 240h:23m:31s, considering the operation of the WEEE reverse chain as a whole, generating savings of 74h:42m:2s. It should be noted that the optimization sought to reach 220 hours of operation to avoid overtime for drivers, but in the metropolitan region of São Paulo this was not possible due to traffic. This result is important for the theory because in optimizing a realistic scenario in a large metropolis, such as São Paulo, it is not possible to optimize 100% of overtime in transport, that is, it is not possible to program the route without traffic. It is noteworthy that this finding was not evidenced in any study on the subject, denoting innovation in terms of managerial implications for the WEEE reverse logistics process.

Also, after optimizing the reverse WEEE chain in Brazil, the VUCs occupancy rate improved from 74.82% to 97.21%, even using 3 VUCs less. This finding can be explained considering that each collection process of each VUC passes through several collection points, making it possible to better use the vehicle's cubage. Research on the subject indicates percentage data of optimizations, without detailing the reasons, for example, detailing the reduction in the volume of VUCs. This aspect is strategic for the transport area, being a relevant result for organizational practice, which also contributes to the circular economy. The reverse chain optimization reduced 3 VUCs, in addition to reducing the need to work a lot of overtime, due to better scheduling of collections at different points simultaneously respecting the use of VUC cubage with better effectiveness. This study contributes to the theory because we are not aware of any research that applied simulation and computational intelligence techniques with the use of artificial intelligence and genetic algorithm for economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network in Brazil, specifically in São Paulo, considering the manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers.

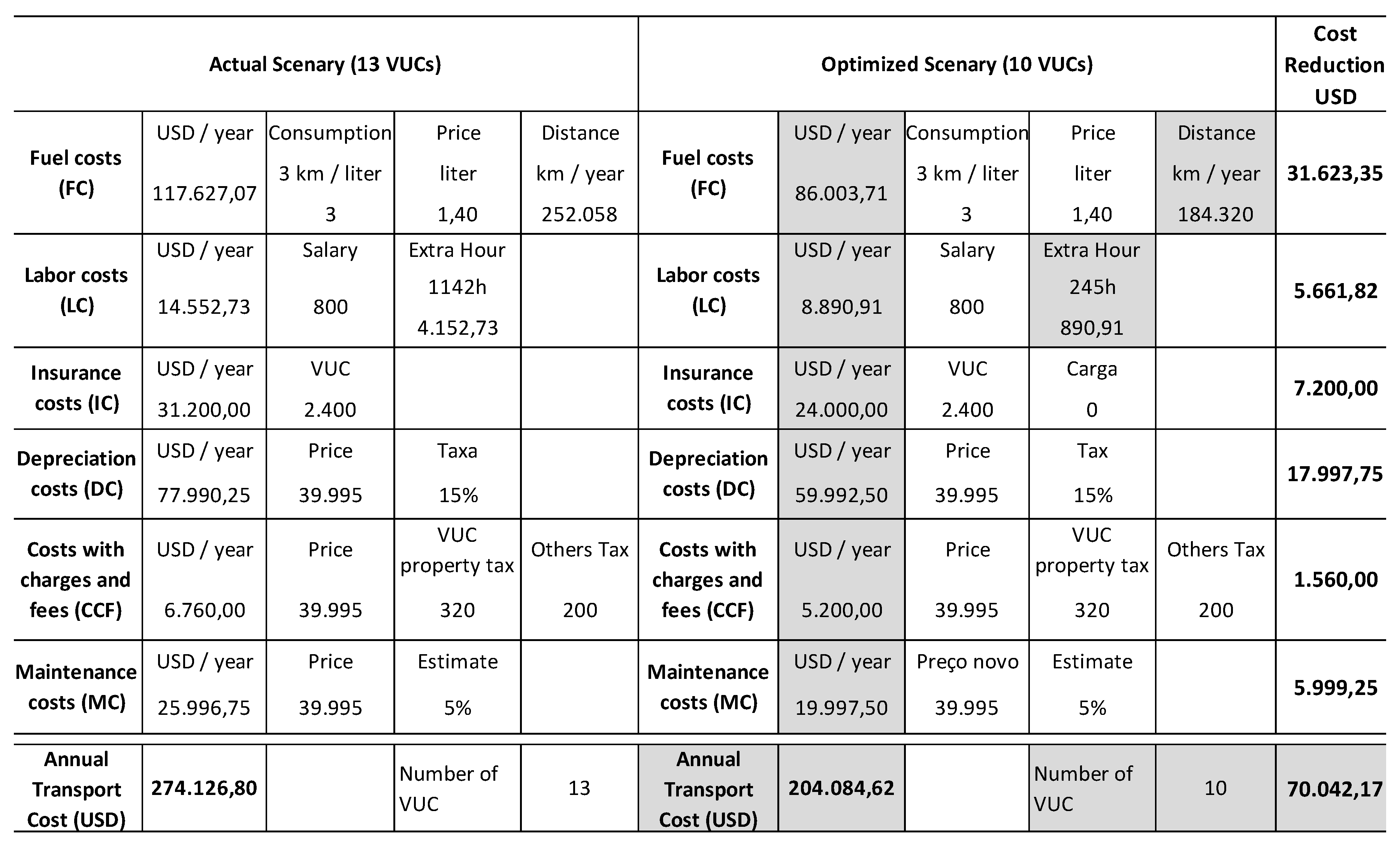

4.2.1. Economic Gain with WEEE Reverse Chain Optimization

The WEEE manager is responsible for the operation of the reverse chain, which decided to outsource transport for the collection of WEEE at the 554 collection and unloading points at the 3 recyclers. An average value of USD 109.81 per freight was agreed with the carrier, and in the current scenario there are 260 VUCs leaving for monthly WEEE collection, summing up the monthly cost of USD 28550.60 and annual cost of USD 342607.20. It should be noted that a profit of approximately 25% was agreed with the carrier on operating costs, which in the current scenario is USD 274,126.80 and monthly is USD 22,843.90.

Table 6 shows the cost assessment of the current and optimized scenario. With the optimization of the WEEE reverse chain transport, the distance traveled per year was minimized from 252058 to 184320 km, saving USD 31623.35 in fuel consumption.

It also reduced employee costs by USD 5661.82 due to optimization of VUCs from 13 to 10 and minimization of overtime by USD 3261.82 per year. This finding contributes to social gain, because due to better route planning, drivers spend less time in traffic or waiting to collect WEEE at collection points. The social gain is related to a better quality of life for drivers, who will be able to work without overtime, making better use of time spent with their families. This result is a relevant aspect to promote the circular economy.

Also with the optimization of the fleet, the following reductions per year were: insurance costs of USD 7200.00, depreciation cost of USD 17997.75, costs with charges and fees of USD 1560.00 and maintenance costs of USD 5999.25 . This is the first study that presents the detail of the cost evaluation between the current and the optimized scenario, making it possible to clearly present the cost reduction with the optimization of the WEEE reverse chain. Research on the subject mostly presents total cost reductions without much detail, as is the case of research by Achillas et al.[

22] held in Greece with the economic gain of 545 thousand Euros; Mar-Ortiz et al.[

17] with a 29.2% reduction in transport costs in Spain; and Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] generating a 33% increase in profit in Colombia.

Based on this assessment, it was possible to require the carrier to reduce the operation costs to USD 255105.775 per year, and monthly to USD 21258.82. This result shows that it is important to provide contractual transparency in terms of operating costs between the contractor (WEEE manager) and the contractor (carrier). It also shows that it was important to add to the contract that the carrier's gain would be 25% on operating costs.

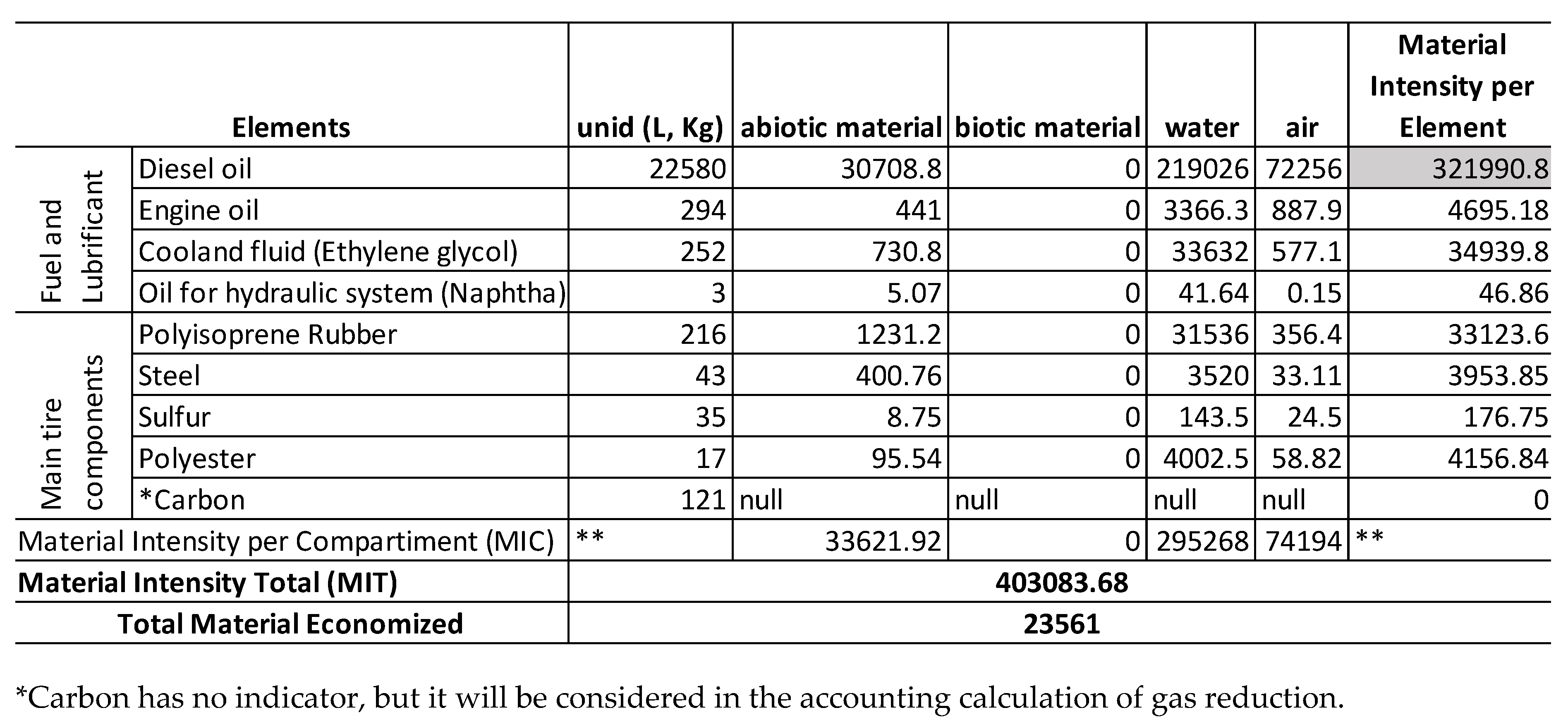

4.2.2. Environmental Gain with WEEE Reverse Chain Optimization

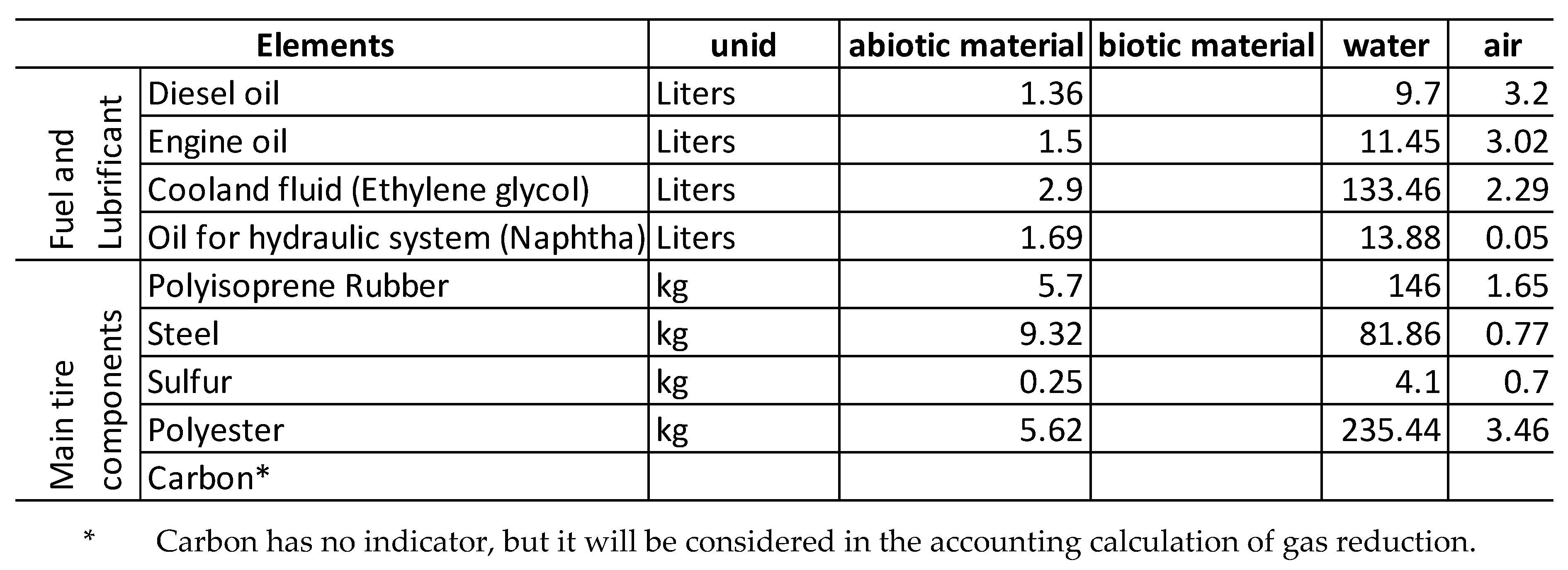

Table 7 shows the elements divided into fuel/lubricant and main components of the tire, which were optimized in the WEEE reverse logistics operation. Thus, there was a reduction of environmental impacts in the compartments: (i) abiotic in 33621.92 kg, which represents factors related to global warming, air quality and minimization of pollution in fauna and flora. It should be noted that these factors directly affect the health of society, increasing the social cost; (ii) water in 295268 kg, reducing pollution in the local water system; and (iii) reduction in air pollution by 74194 kg. With that, it generated global minimization of 403083.68 kg. In this context, this is the first study that calculates the reduction of environmental impacts in abiotic compartments, water and air due to the optimization of the WEEE reverse chain transport using artificial intelligence. For the environmental assessment, the Material Intensity Factor was used, which is a relevant tool for global assessment of the minimization of environmental impacts, not using only percentage data, for example, Achillas et al [

22] mentioned a 5% reduction in CO² pollutants ( from fossil fuels) and Llerena-Riascos et al. [

4] reported that it generated 65% in environmental benefits. Thus, the researches do not present the reduction of impacts in the abiotic compartments, water and air, subject not explored in the scientific literature in the published simulation models. This result contributes to the adoption of a circular economy, due to the reduction of environmental impacts in transport,

Another relevant finding is that the tire components (rubber, steel, sulfur and polyester) are the most relevant in the optimization, minimizing 41411 kg, followed by the reduction of environmental impact due to diesel optimization in 321998.80 kg. It should be noted that carbon black was not considered in this calculation, because tire wear generates carbon particles, which are more related to the dust that affects breathing, being classified as emissions, which will be calculated later. Thus, by optimizing the use of VUCs, tire and fuel consumption was further minimized, an innovative aspect in research that adopted optimization with the use of artificial intelligence, which in most cases is concerned with the tool used and not with reducing impacts realistic environmental issues that promote circular economy,

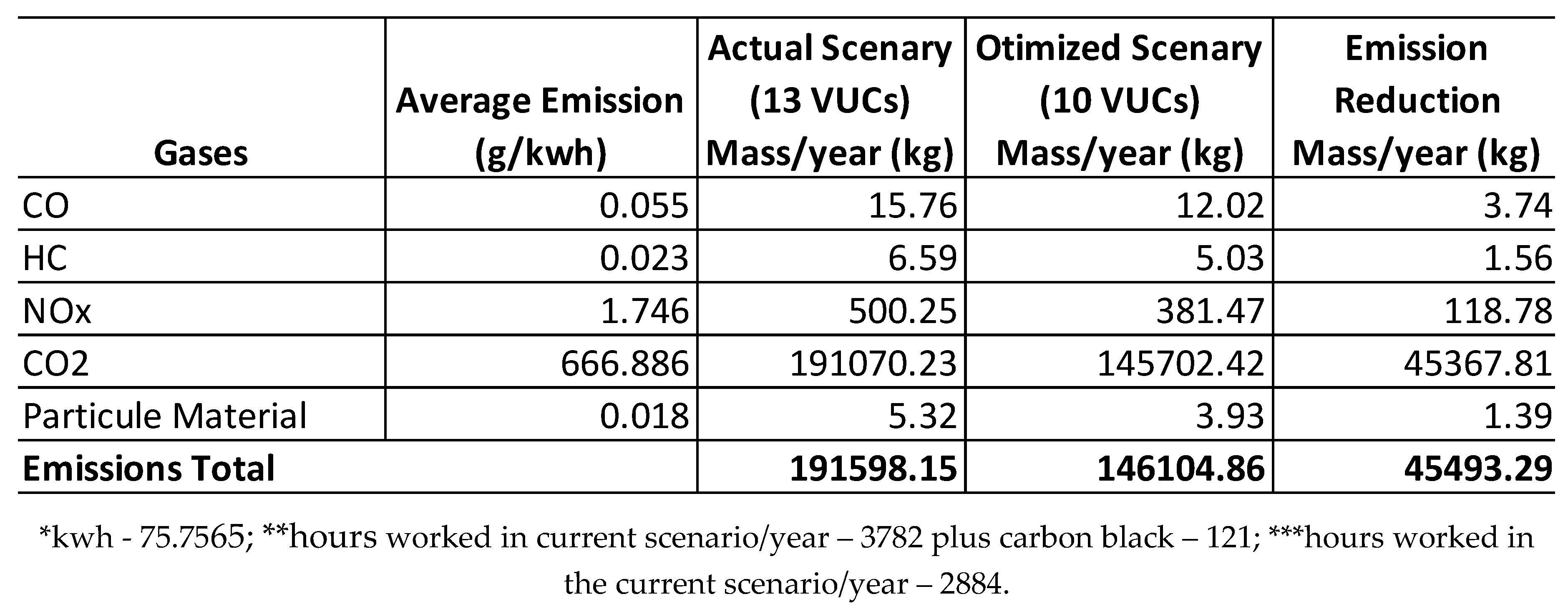

There was also a reduction in emissions of 45,493.25 kg of the main polluting gases resulting from the transport operation in São Paulo, as shown in

Table 8. Carbon dioxide is the main pollutant of the Earth's atmosphere, which affects the health of society; however, 45367.81 kg were optimized with the reduction of collections from 286 to 220, denoting an important contribution, despite not solving the problem in its entirety. This finding innovates the state of the art by measuring the reduction of emissions of the main gases responsible for the greenhouse effect due to the optimization of the transport of the reverse chain of WEEE to promote circular economy, as well as, it indicates to managers an important way to reduce gas emissions , mainly CO2, to contribute to the 2030 agenda.

Another interesting result was the reduction of particulate matter from 5.32 to 3.93 in air. Pollution from particles generated from carbon black from worn-out tires and gas emissions drastically affects the lungs, causing serious illnesses. The reduction generated was 1.39 kg per year, showing that the adoption of artificial intelligence for route optimization is a promising tool for reducing emissions of greenhouse gases and particles that contributes to the circular economy, denoting a relevant theoretical and practical contribution .

6. Conclusion

It is concluded that the optimization of the WEEE reverse chain for São Paulo using artificial intelligence generated economic and environmental gains, promoting a circular economy. The optimized scenario proved to be effective in reducing the number of collections when considering that each collection process the VUC passes through several collection points, making the most of the truck's cubage.

Thus, this study contributes to the theory by presenting the current functioning of the WEEE reverse chain in São Paulo, as well as presenting the optimized scenario with details after the adoption of artificial intelligence. In the current operation, it concluded that the manufacturers outsourced WEEE management and reverse logistics operation, denoting that WEEE management using reverse logistics is a support activity. Also, with the application of artificial intelligence, it was possible to present an optimized scenario that considered the programming for the removal of WEEE, where each collection process, the VUC passes through several points until it loads the truck as much as possible. This optimized WEEE reverse logistics schedule reduced the number of collections, 3 VUCs and overtime – improving the quality of life for drivers, generating economic and environmental benefits, promoting the circular economy. It should be noted that this is the first study that applied computer simulation with the use of artificial intelligence through genetic algorithm for economic and environmental optimization of the reverse WEEE network, considering manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers.

Thus, the cost reduction was concluded comparing the current scenario and the optimized one, forcing the contractor to reduce the freight price, as well as this is the first study that calculates the reduction of environmental impacts in the abiotic compartments, water and air on the subject, mainly evaluating the minimization of emissions of the main polluting gases generated by trucks, contributing to circular economy actions. Thus, this is the first study that presents the calculation of cost and time reduction in detail, in addition to measuring the improvement in the volume of vehicles, being a primordial aspect in the optimization and guidance of operations managers.

It also contributes to the organizational practice because it organized the WEEE reverse chain operations, an aspect that it was not possible to identify in the current scenario with operational details. It should be noted that complex optimization scenarios without detailing make it impossible for managers to apply them in practice. Thus, an operations manager could easily understand the process performed for optimization, enabling its replication in practice. The main problems found in practice that can be solved with this optimization are: (i) not answering requests for individual collections, but carrying out programmed collections at several collection points, taking advantage of the vehicle's volume as much as possible; (ii) it was not possible to optimize 100% of the extra hours of the transport operation due to traffic, but it was possible to optimize as much as possible; (iii) the lack of vision of the whole WEEE reverse chain made it difficult to study the reduction of 3 VUCs in the operation, generating environmental and economic gains. Another important aspect was the development of the contract with transparency in terms of costs, considering that the cost reduction would lead to a reduction in the freight price. In addition to the reduction of environmental impacts, and minimization of greenhouse gas emissions in a realistic scenario.

Also, this topic is relevant and emerging in the business environment of the electronics sector because the sectoral agreement was signed in October 2019 based on law 12,305 enacted in 2010 on the mandatory management of WEEE through reverse logistics aimed at sharing responsibilities for WEEE management between manufacturers, waste managers and recyclers in São Paulo, who are structuring the reverse chain.

The implementation of the reverse WEEE network in São Paulo also contributes to society, because the environmental impact resulting from the inadequate disposal of WEEE in common sanitary landfills and the generation of greenhouse gas emissions is being minimized, as well as several informal recyclers with ability to be part of the reverse WEEE network will be formalized, generating employment and, in particular, informal collectors may have the opportunity for formalized employment.

The main limitation of this study was the realization of the regional research in São Paulo, Brazil, justified because it is the first Brazilian State that has the obligation to implement WEEE reverse logistics. For future studies, it suggests carrying out this research in other states and countries with the aim of generating comparison between them, making it possible to generate relevant results for theory, practice and government actions.