Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

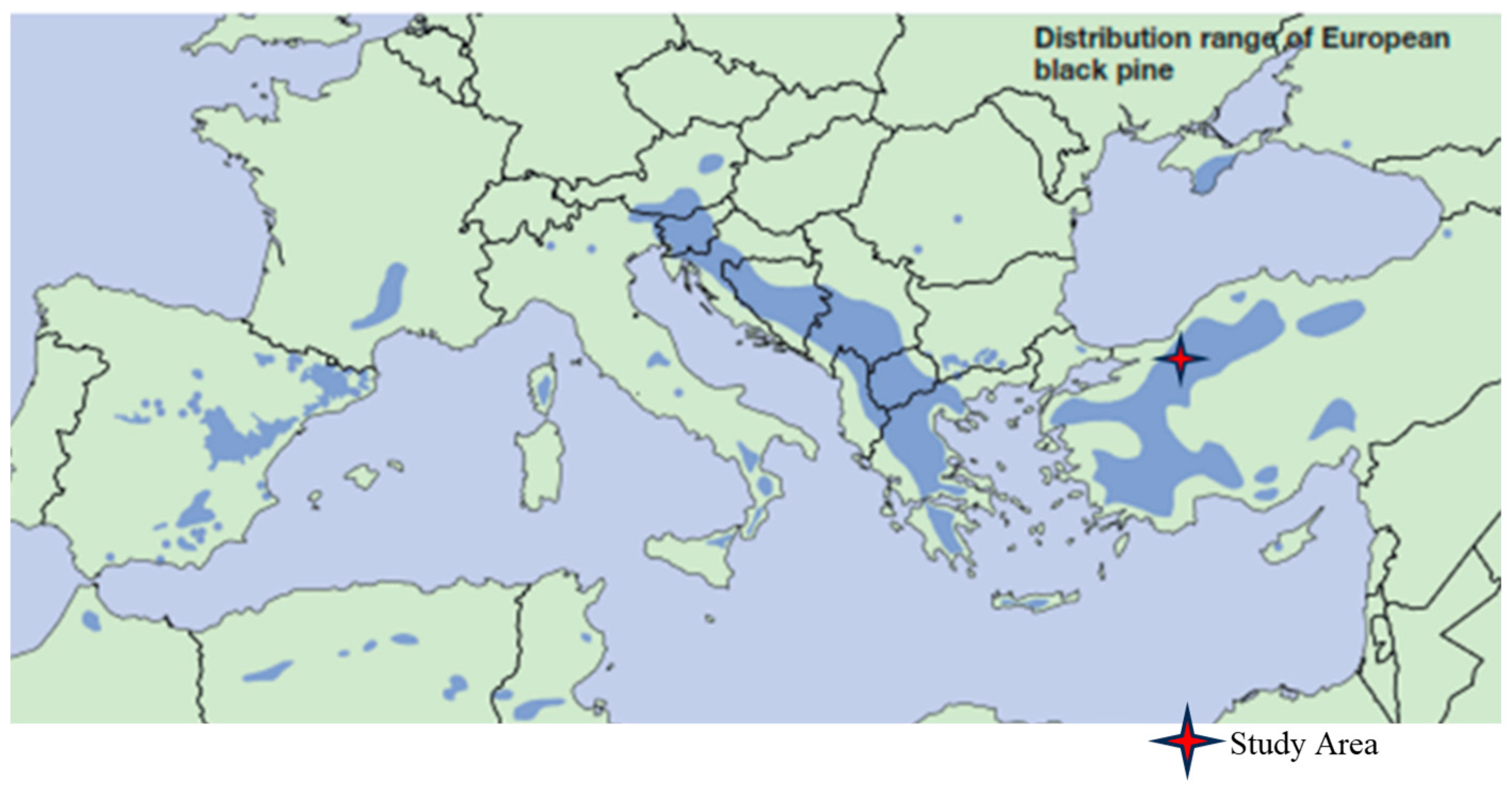

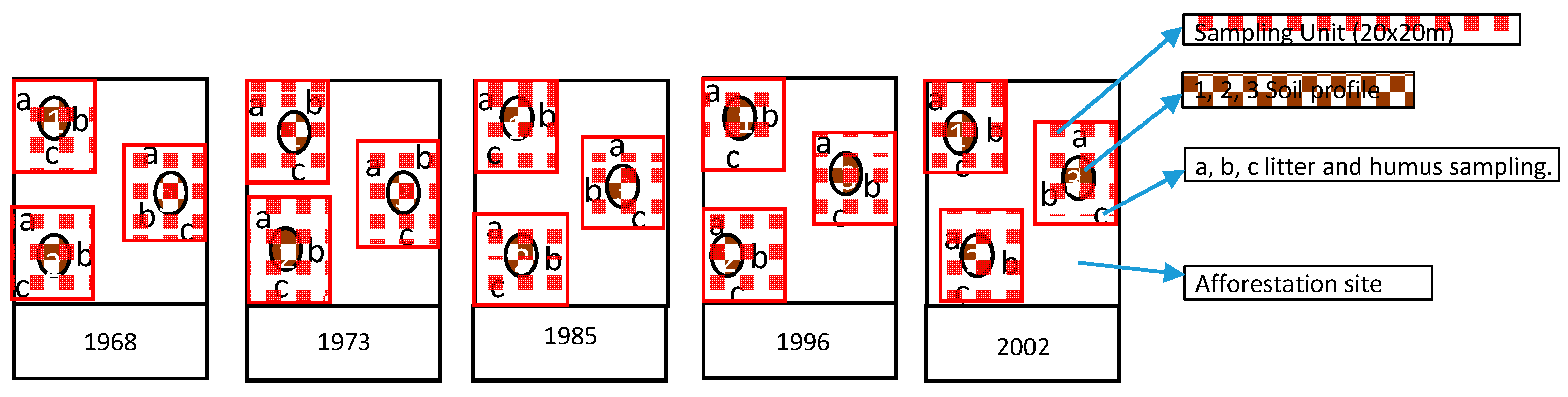

2.1. Study Area and Sampling

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC), pH, EC, and Total Lime (CaCO3) Concentrations

3.2. Soil Texture (Sand, Clay, and Silt Concentrations) and Bulk Density (g cm-3)

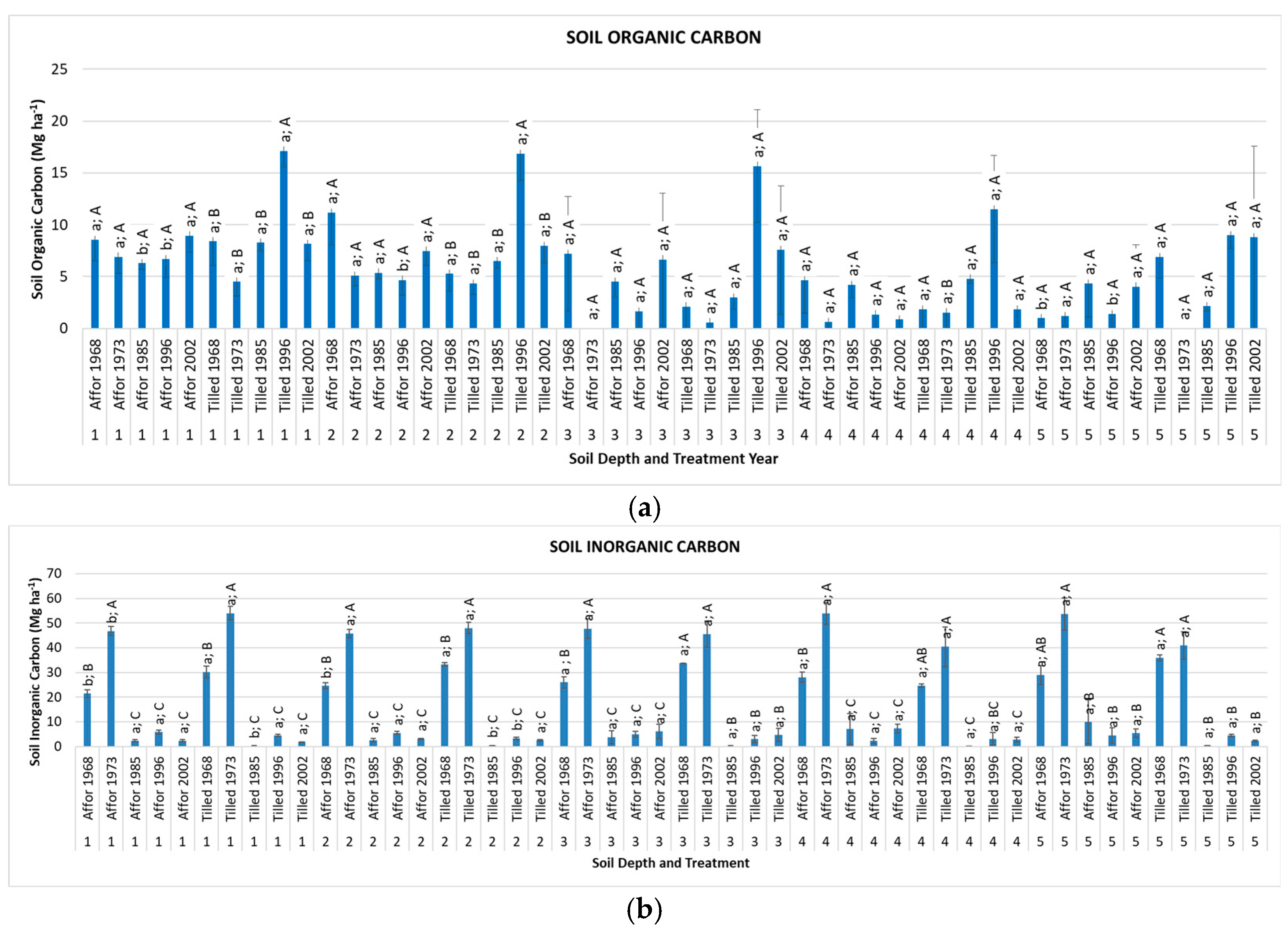

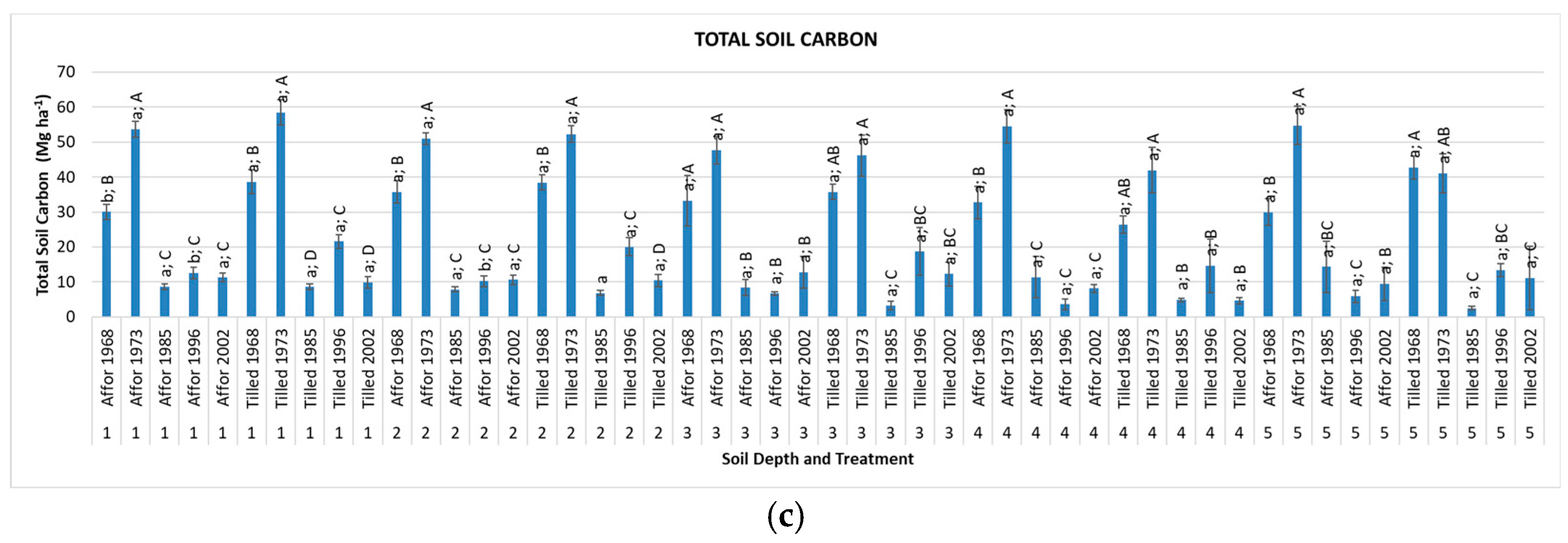

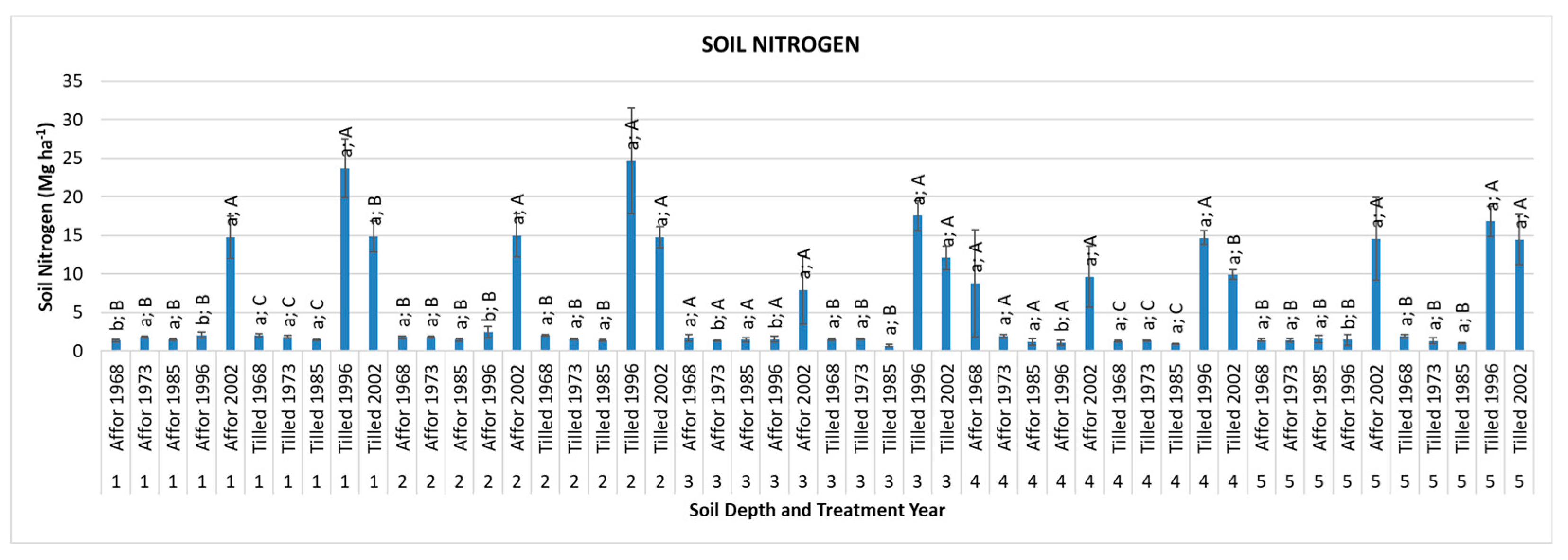

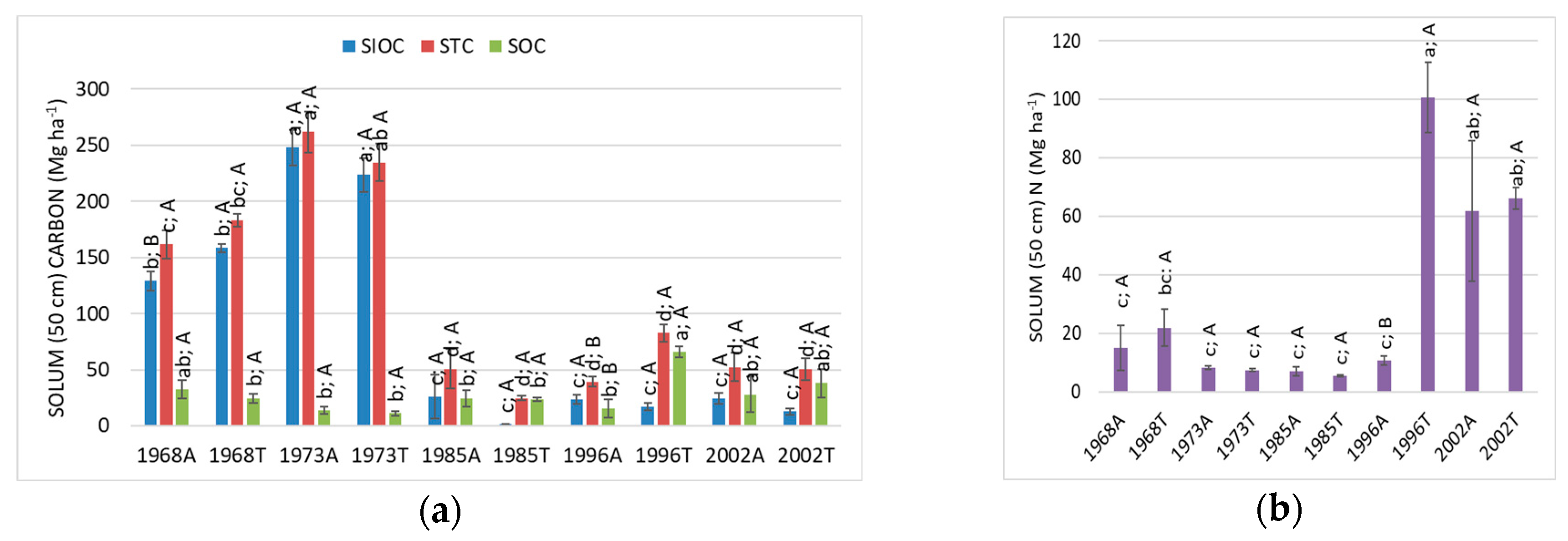

3.3. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen

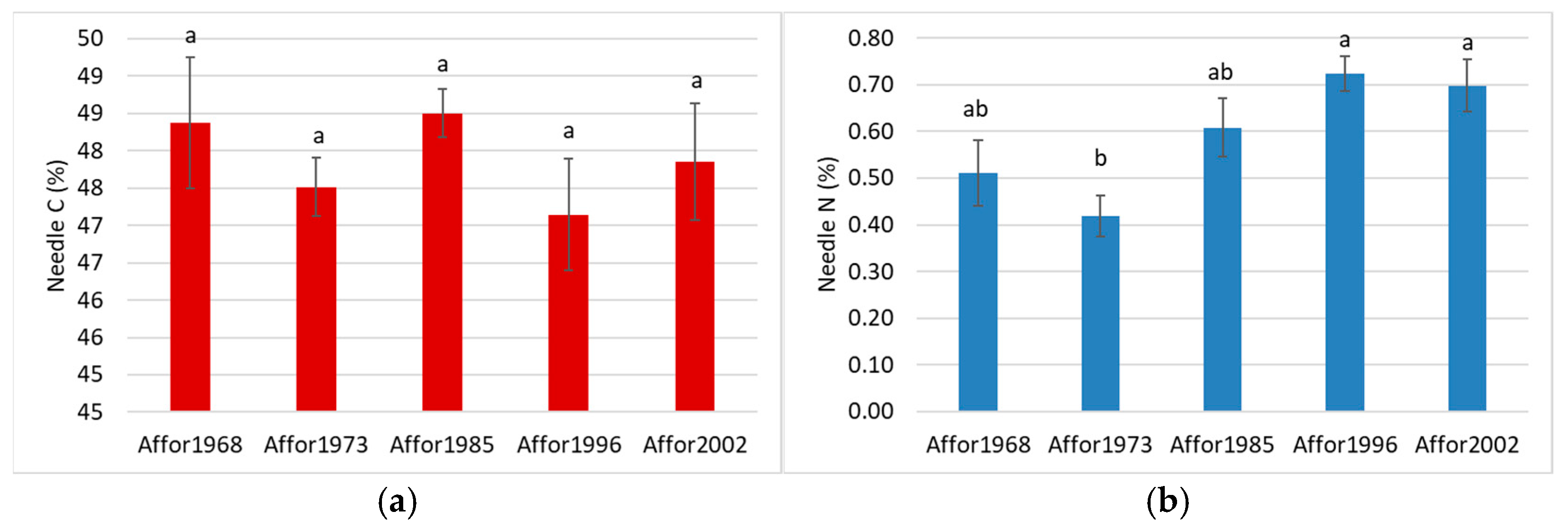

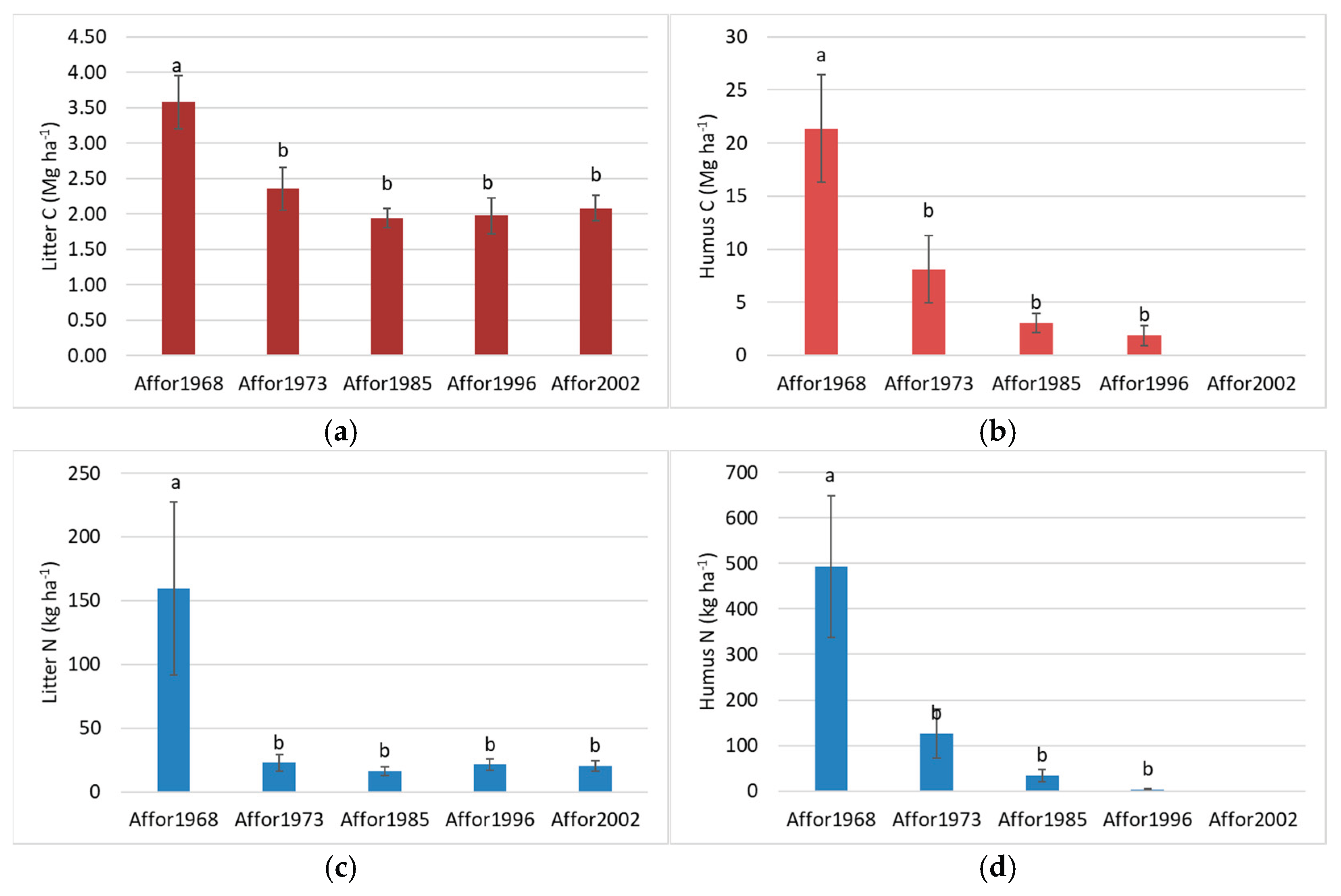

3.3. Carbon and Nitrogen Contents of Tree Needles, Litter and Humus

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M., N. G. Pricope, A. Toreti, E. Morán-Tejeda, J. Spinoni, A. Ocampo-Melgar, and A.D. E. Archer, T. Mesbahzadeh, N. H. Ravindranath, R. S. Pulwarty and S. Alibakhshi The Global Threat of Drying Lands: Regional and global aridity trends and future projections. A Report of the Science-Policy Interface. United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). 2024: Bonn, Germany.

- Rundel, P.W., et al., Arid and Semi-Arid Ecosystems, in The Physical Geography of South America. 2007, Oxford University Press. p. 0.

- Li, C., et al., Carbon stock and its responses to climate change in C entral A sia. Global change biology, 2015. 21(5): p. 1951-1967.

- Zerga, B., Rangeland degradation and restoration: A global perspective. Point Journal of Agriculture and Biotechnology Research, 2015. 1(2): p. 37-54.

- Yıldız, O.; Eşen, D.; Sargıncı, M.; Çetin, B.; Toprak, B.; Dönmez, A.H. Restoration success in afforestation sites established at different times in arid lands of Central Anatolia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, O.; Esen, D.; Karaoz, O.M.; Sarginci, M.; Toprak, B.; Soysal, Y. Effects of different site preparation methods on soil carbon and nutrient removal from Eastern beech regeneration sites in Turkey's Black Sea region. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2010, 45, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, E.P. and G.W. Barrett, Fundamentals of ecology. 5 ed. 2005: Thomson-Brooks/Cole.

- Odum, E.P. and G.W. Barrett, Fundamentals of ecology. 1971: Thomson-Brooks/Cole.

- McAlpine, C., et al., Integrating plant-and animal-based perspectives for more effective restoration of biodiversity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2016. 14(1): p. 37-45.

- Yıldız, O., D. Eşen, and M. Sargıncı, Orman yangınlarının besin elementleri ve ekosistem verimliliğine etkileri. Tabiat ve İnsan,(3-4), 2004: p. 56-63.

- O. Yıldız, D.E., M. Sarginci, and B. Toprak, Batı Karadeniz Bölgesi'nde orman açmalarının toprak karbonu ve makro-besin yoğunluğuna etkisi (Effects of forest clearings on soil carbon and macronutrient density in the Western Black Sea Region), in IX. Ulusal Ekoloji ve Çevre Kongresi (IX: National Ecology and Environment Congress). 2009: Nevşehir, Türkiye. p. 81.

- Rotenberg, E.; Yakir, D. Contribution of Semi-Arid Forests to the Climate System. Science 2010, 327, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNCCD, Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twelfth session. 12-23 October 2015: Ankara, Türkiye.

- Tolunay, D. and A. Çömez, Orman topraklarında karbon depolanması ve Türkiye’deki durum (Carbon sequestration in forest soils and the sitiuation in Türkiye), in Küresel İklim Değişimi ve Su Sorunlarının Çözümünde Ormanlar Sempozyumu (Forests in the Solution of Global Climate Change and Water Problems Symposium). 13-14 December 2007: İstanbul, Türkiye.

- Penuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Filella, I.; Estiarte, M.; Llusià, J.; Ogaya, R.; Carnicer, J.; Bartrons, M.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Grau, O.; et al. Impacts of Global Change on Mediterranean Forests and Their Services. Forests 2017, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, B., et al., Climate and environmental change in the Mediterranean basin–current situation and risks for the future. First Mediterranean assessment report. 2020.

- Gumus, B.; Oruc, S.; Yucel, I.; Yilmaz, M.T. Impacts of Climate Change on Extreme Climate Indices in Türkiye Driven by High-Resolution Downscaled CMIP6 Climate Models. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, A., et al., Defining climate-smart forestry. Climate-Smart Forestry in Mountain Regions, 2022: p. 35-58.

- Diaz, J., et al., Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin-Current Situation and Risks for the Future. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin–Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report, 2020.

- epel, N., Yokettiğimiz ormanlarımız kayboılan fonksiyonel değerler ve zamanımızn orman ölümleri [Forests we eradicated, functional values we lost and current forest diebacks]. 1995: TEMA Vakfı.

- Turkes, M., Vulnerability of Turkey to desertification with respect to precipitation and aridity conditions. Turkish Journal of Engineering and Environmental Science, 1999. 23(5): p. 363-80.

- Türkeş, M., BM Çölleşme İle Savaşım Sözleşmesi’nin İklim, İklim Değişikliği ve kuraklık açısından çözümlenmesi ve Türkiye’deki uygulamalar (Analysis of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification with respect to the Climate, Climate Change and Drought, and Applications in Turkey)’. Çölleşme İle Mücadele Sempozyumu Tebliğler Kitabı, 2010: p. 17-18.

- Vacek, Z.; Cukor, J.; Vacek, S.; Gallo, J.; Bažant, V.; Zeidler, A. Role of black pine (Pinus nigra J. F. Arnold) in European forests modified by climate change. Eur. J. For. Res. 2023, 142, 1239–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñas, R.A., et al., Pinus pinea in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats. European atlas of forest tree species, 2016: p. 204.

- GDF), R.o.T.M.o.A.a.F.G.D.o.F. Forestry Statistics 2023.zip. [Zip file] 2023 [cited 2025 03.06]; Available from: https://www.ogm.gov.tr/en/e-library/official-statistics.

- Saatçioğlu, F., Türkiye Silvikültüründe Yapraklı Ağaç Türleri Meselesi. Journal of the Faculty of Forestry, Istanbul University, 1969.

- Karaçam, ed. B.T. Orhan Sevgi, Taner Okan. 2022, Tuna Caddesi No: 5/8 Kızılay-Ankara: Türkiye Ormancılar Derneği (The Foresters’ Association of Turkey).

- Güner, D. and K. Özkan, Türkiye’deki karaçam ağaçlandırma alanlarında besin stoklarının belirlenmesi. Ormancılık Araştırma Dergisi, 2019. 6(2): p. 192-207.

- Bulut, S., Günlü, and S. Keles, Assessment of the interactions among net primary productivity, leaf area index and stand parameters in pure Anatolian black pine stands: A case study from Türkiye. Forest Systems, 2023. 32(1): p. e003-e003.

- Hong, S.; Yin, G.; Piao, S.; Dybzinski, R.; Cong, N.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Peñuelas, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, A. Divergent responses of soil organic carbon to afforestation. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkanç, S.Y. Effects of afforestation on soil organic carbon and other soil properties. CATENA 2014, 123, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-F.; He, Z.-B.; Zhu, X.; Du, J.; Yang, J.-J.; Li, J. Impacts of afforestation on plant diversity, soil properties, and soil organic carbon storage in a semi-arid grassland of northwestern China. CATENA 2016, 147, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, Q.; Huang, F.; Li, L. Dynamics of soil carbon and nitrogen stocks after afforestation in arid and semi-arid regions: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 618, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Tariq, A.; Graciano, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Keyimu, M.; Cong, M.; Zhao, G.; Yan, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Afforestation-driven soil organic carbon stabilization in a hyper-arid desert: nonlinear dynamics and microbial drivers across a 22-year chronosequence. Environ. Res. 2025, 282, 121989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wei, C.; Adamowski, J.F.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Zhu, G.; Dong, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Feng, Q. Could arid and semi-arid abandoned lands prove ecologically or economically valuable if they afford greater soil organic carbon storage than afforested lands in China’s Loess Plateau? Land Use Policy 2020, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, C.; Jiménez, M.; Nieto, O.; Navarro, F.; Fernández-Ondoño, E. Changes in soil organic carbon over 20 years after afforestation in semiarid SE Spain. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 381, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, M.; Zhao, X. Variable response of inorganic carbon and consistent increase of organic carbon as a consequence of afforestation in areas with semiarid soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., et al., Recovery of soil carbon and nitrogen stocks following afforestation with xerophytic shrubs in the Tengger Desert, North China. Catena, 2022. 214: p. 106277.

- Gelfand, I.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Yakir, D. Slowing of nitrogen cycling and increasing nitrogen use efficiency following afforestation of semi-arid shrubland. Oecologia 2011, 168, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Shi, W.; Li, Y.; Guo, Q. Afforestation with xerophytic shrubs accelerates soil net nitrogen nitrification and mineralization in the Tengger Desert, Northern China. CATENA 2018, 169, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Directorate of Forestry, Ankara Forest Regional Directorate, Nallıhan Forest Enterprise Directorate Nallıhan Forest Enterprise Chiefship, Functional Forest Management Plan 2012-2031. 2012.

- General Directorate of Forestry, Ankara Forest Regional Directorate, Nallıhan Forest Enterprise Directorate Uluhan Forest Enterprise Chiefship, Functional Forest Management Plan 2012-2031. 2012.

- Dostbil, Y., Ağaçlandırma Çalışmalarının Uygulama Tekniği (Application technics of Plantation Activities), in Ağaçlandırma (Plantation), İ. Özkahraman, Editor. 1986, T.C. Tarım Orman ve Köyişleri Bakanlığı Orman Genel Müdürlüğü Ağaçlandırma ve Silvikültür Dairesi (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Affairs, General Directorate of Forestry, Department of Afforestation and Silviculture) Gelişim Press: Ankara. p. 25-40.

- Atalay, I. and R. Efe, Structural and distributional evaluation of forest ecosystems in Turkey. Journal of Environmental Biology, 2010. 31(1): p. 61.

- Atalay, I.; Efe, R.; Öztürk, M. Ecology and Classification of Forests in Turkey. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 120, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Climate According to Thornthwaite. Ministry of Environment, Urbanisation and Climate Change, Turkish State Meteorological Service [Image of Turkish Climate According to Thornthwaite] [cited 2025 07.06.2025]; Available from: https://www.mgm.gov.tr/iklim/iklim-siniflandirmalari.aspx.

- Aksoy, N., Karakiriş Dağı (Seben-Nallıhan) florası (Flora of Karakiriş Mountain (Seben-Nallıhan)). Düzce Üniversitesi Ormancılık Dergisi, 2009. 5(2): p. 104-125.

- Kantarcı, M.D., Toprak İlmi (Soil Science). 2 ed. 2000, İstanbul, Türkiye: İstanbul Üniversitesi Orman Fakültesi Yayınları Yayın No: 4261.

- FAO. Soil Map of The World - Europe. [PDF] 1992 [cited 2025 22 June]; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/soils/docs/Soil_map_FAOUNESCO/acrobat/Europe_V.pdf.

- USDA. Soil Taxonomy. A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys. [PDF] 1999 [cited 2025 22 June]; United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service]. Available from: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/Soil%20Taxonomy.pdf.

- Isajev, V., B. Fady, H. and S.a.V. Andonovski, EUFORGEN Technical Guidelines for genetic conservation and use for European black pine (Pinus nigra). 2004: International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy.

- Day, P.R., Particle fractionation and particle-size analysis. Methods of soil analysis: part 1 physical and mineralogical properties, including statistics of measurement and sampling, 1965. 9: p. 545-567.

- Sparks, D.L., et al., Methods of soil analysis, part 3: Chemical methods. 2020: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gee, G.W. and J.W. Bauder, Particle-size analysis. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1 Physical and mineralogical methods, 1986. 5: p. 383-411.

- Thomas, G.W., Soil pH and soil acidity. Methods of soil analysis: part 3 chemical methods, 1996. 5: p. 475-490.

- Rhoades, J., Salinity: Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. Methods of soil analysis: Part 3 Chemical methods, 1996. 5: p. 417-435.

- Loeppert, R.H. and D.L. Suarez, Carbonate and gypsum. Methods of soil analysis: Part 3 chemical methods, 1996. 5: p. 437-474.

- Hamid, Y., Determine CaCO3 in different soil horizons using the Scheibler's Calcimeter. 2007.

- Gorbov, S.N.; Minaeva, E.N.; Tagiverdiev, S.S.; Skripnikov, P.N.; Nosov, G.N.; Besuglova, O.S. Comparison of Different Carbonate Methods for Determining Calcic Chernozems. Biol. Bull. 2024, 51, S384–S394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M.E. and W.P. Miller, Cation exchange capacity and exchange coefficients. Methods of soil analysis: Part 3 Chemical methods, 1996. 5: p. 1201-1229.

- Nelson, D.W. and L.E. Sommers, Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties, 1982. 9: p. 539-579.

- Nelson, D.W. and L.E. Sommers, Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods of soil analysis: Part 3 Chemical methods, 1996. 5: p. 961-1010.

- Gentilesca, T.; Battipaglia, G.; Borghetti, M.; Colangelo, M.; Altieri, S.; Ferrara, A.M.S.; Lapolla, A.; Rita, A.; Ripullone, F. Evaluating growth and intrinsic water-use efficiency in hardwood and conifer mixed plantations. Trees 2021, 35, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarcı, M., et al., An assessment on the adaptation of 6 tree species to steppe habitat during Konya-Karapinar sand-dune afforestations. 2011.

- Yildiz, O.; Altundağ, E.; Çetin, B.; Güner, Ş.T.; Sarginci, M.; Toprak, B. Experimental arid land afforestation in Central Anatolia, Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, S., C. Yücedag, and B. Simovski, A major tool for afforestation of semi-arid and anthropogenic steppe areas in Turkey: Pinus nigra JF Arnold subsp. pallasiana (Lamb.) Holmboe. Journal of Forest Science, 2021. 67(10): p. 449-463.

- ALIŞKAN, S. and M. Boydak, Afforestation of arid and semiarid ecosystems in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2017. 41(5): p. 317-330.

- Kaya, Z. and A. Temerit, Genetic structure of marginally located Pinus nigra var pallasiana populations in central Turkey. Silvae Genetica, 1994. 43(5): p. 272-276.

- Yildiz, O.; Sarginci, M.; Eşen, D.; Cromack, K. Effects of vegetation control on nutrient removal and Fagus orientalis, Lipsky regeneration in the western Black Sea Region of Turkey. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 240, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacisalihoglu, S. Semi-Arid Plantation by Anatolian Black Pine and Its Effects on Soil Erosion and Soil Properties. Turk. J. Agric. - Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 6, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, T., Soil compaction and soil management–a review. Soil use and management, 2009. 25(4): p. 335-345.

- Kara, O.; Babur, E.; Altun, L.; Seyis, M. Effects of afforestation on microbial biomass C and respiration in eroded soils of Turkey. J. Sustain. For. 2016, 35, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, R.; Smettem, K. Runoff change induced by vegetation recovery and climate change over carbonate and non-carbonate areas in the karst region of South-west China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, O. and V.K. Kharche, Soil salinity and sodicity. Soil science: an introduction, 2018. 12: p. 353-384.

- Sumner, M.E. Sodic soils—New perspectives. Soil Res. 1993, 31, 683–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Pandey, V.C.; Singh, B.; Singh, R. Ecological restoration of degraded sodic lands through afforestation and cropping. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 43, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Niu, S.; Luo, Y. Global patterns of the dynamics of soil carbon and nitrogen stocks following afforestation: a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiedt, E.; Verheyen, K.; De Smedt, P.; Ponette, Q.; Baeten, L. Early Tree Diversity and Composition Effects on Topsoil Chemistry in Young Forest Plantations Depend on Site Context. Ecosystems 2021, 24, 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Chen, F.; Chen, Q.; Tang, Y. Change of soil K, N and P following forest restoration in rock outcrop rich karst area. CATENA 2020, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, L.; Al-Quraishi, A.M.F.; Branch, O.; Gaznayee, H.A.A. New approaches: Use of assisted natural succession in revegetation of inhabited arid drylands as alternative to large-scale afforestation. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberg, J.; Robinson, D.T.; Trant, A.J.; Richardson, P.J.; Murphy, S.D. Direct topsoil transfer to already planted reforestation sites increases native plant understory and not ruderals. Restor. Ecol. 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I. Seeking Environmental Sustainability in Dryland Forestry. Forests 2019, 10, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M.E.; Franklin, J.F.; Beschta, R.L.; Crisafulli, C.M.; DellaSala, D.A.; Hutto, R.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Swanson, F.J. The forgotten stage of forest succession: early-successional ecosystems on forest sites. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, K.; Tichý, L.; Lencová, K.; Adámek, M.; Koutecký, T.; Sádlo, J.; Bartošová, A.; Novák, J.; Kovář, P.; Jírová, A.; et al. Does succession run towards potential natural vegetation? An analysis across seres. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.C., H.H. Shugart, and D. Botkin, Forest succession: concepts and application. 2012: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Steele, R., The role of succession in forest health, in Assessing forest ecosystem health in the inland west. 2018, Routledge. p. 183-190.

- Bonser, S.P.; Ladd, B. The evolution of competitive strategies in annual plants. Plant Ecol. 2011, 212, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, H.L.; Good, J. Effects of afforestation on upland plant communities and implications for vegetation management. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 79, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Fadhil Al-Quraishi, A., New approaches: Use of assisted natural succession in revegetation of inhabited arid drylands as alternative to large-scale aforestation. SN Applied Sciences, 2022.

- Moro, M.J.; Domingo, F.; Escarré, A. Organic Matter and Nitrogen Cycles in a Pine Afforested Catchment with a Shrub Layer ofAdenocarpus decorticansandCistus laurifoliusin South-eastern Spain. Ann. Bot. 1996, 78, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Afforestation Year | Stand Age (~) | Solum (cm) | Coordinates (UTM) | Elevation (m) |

| 1968 | 47 | 100 | 343763 4461477 | 926 |

| 47 | 100 | 343745 4461549 | 950 | |

| 47 | 100 | 343771 4461653 | 944 | |

| 1973 | 42 | 100 | 379463 4454728 | 1086 |

| 42 | 100 | 379499 4454664 | 1077 | |

| 42 | 100 | 379496 4454622 | 1074 | |

| 1985 | 30 | 50 | 380702 4454140 | 1168 |

| 30 | 60 | 380711 4454140 | 1164 | |

| 30 | 50 | 380698 4454204 | 1163 | |

| 1996 | 19 | 50 | 382765 4453174 | 1193 |

| 19 | 80 | 382746 4453165 | 1184 | |

| 19 | 50 | 382724 4453119 | 1180 | |

| 2002 | 13 | 70 | 378729 4458427 | 1422 |

| 13 | 50 | 378781 4458462 | 1429 | |

| 13 | 50 | 378807 4458476 | 1430 |

| Depth Level | Treatment | CEC (cmolc kg-1) | PH | EC (µS cm-1) | Total Lime (CaCO3%) |

| 1 | Affo1968 | 22.2 ± 1.37aDC | 7.54 ± 0.04aAB | 155.8 ± 9.66bA | 22.62 ± 1.13bB |

| 1 | Affo1973 | 28.75 ± 0.9aBC | 7.5 ± 0.02aAB | 129.04 ± 4.21bB | 46.19 ± 1.16bA |

| 1 | Affo1985 | 33.69 ± 0.84aAB | 7.38 ± 0.09aB | 116.68 ± 8.54aBC | 2.62 ± 0.58aD |

| 1 | Affo1996 | 36.05 ± 3.02aA | 7.61 ± 0.05aA | 138.58 ± 3.24aAB | 7.55 ± 0.91aC |

| 1 | Affo2002 | 18.96 ± 1.06aD | 7.43 ± 0.02aAB | 94.12 ± 2.6aC | 2.07 ± 0.32aD |

| 1 | Tilled 1968 | 22.22 ± 0.67aCD | 7.59 ± 0.05aA | 202.75 ± 6.99aA | 28.35 ± 1.27aB |

| 1 | Tilled 1973 | 26.22 ± 1.2aBC | 7.55 ± 0.04aA | 154.55 ± 11.38aB | 49.9 ± 0.77aA |

| 1 | Tilled 1985 | 36.9 ± 1.81aA | 7.34 ± 0.07aB | 76.75 ± 6.56bC | 0.39 ± 0.07bD |

| 1 | Tilled 1996 | 31.39 ± 0.91aB | 7.41 ± 0.06bAB | 92.93 ± 5.34bC | 4.7 ± 0.38bC |

| 1 | Tilled 2002 | 18.32 ± 1.5aD | 7.34 ± 0.03bB | 78.95 ± 1.92bC | 1.55 ± 0.17aD |

| 2 | Affo1968 | 21.5 ± 1.82aCD | 7.58 ± 0.03aA | 128.63 ± 3.9bAB | 23.55 ± 1.1bB |

| 2 | Affo1973 | 28.45 ± 1.47aBC | 7.49 ± 0.02bA | 127.85 ± 2.62bAB | 45.73 ± 0.89bA |

| 2 | Affo1985 | 34.25 ± 0.88aAB | 7.44 ± 0.07aA | 114.79 ± 10.17aB | 2.76 ± 0.7aD |

| 2 | Affo1996 | 36.38 ± 3.14aA | 7.61 ± 0.04aA | 136.52 ± 3.65aA | 7.36 ± 0.95aC |

| 2 | Affo2002 | 20.72 ± 1.07aD | 7.46 ± 0.03aA | 89.84 ± 1.66aC | 2.6 ± 0.21aD |

| 2 | Tilled 1968 | 22.5 ± 0.53aDC | 7.67 ± 0.06aA | 171.01 ± 3.85aA | 30.21 ± 0.76aB |

| 2 | Tilled 1973 | 27.16 ± 0.99aBC | 7.57 ± 0.02aAB | 158.31 ± 12.52aA | 49.63 ± 1.4aA |

| 2 | Tilled 1985 | 34.02 ± 1.46aA | 7.28 ± 0.04aC | 75.48 ± 7.85bB | 0.49 ± 0.08bD |

| 2 | Tilled 1996 | 30.44 ± 1.77aAB | 7.36 ± 0.08bBC | 93.48 ± 3.13bB | 3.9 ± 0.51bC |

| 2 | Tilled 2002 | 19.44 ± 1.56aD | 7.34 ± 0.04bC | 78.18 ± 4.2bB | 2.28 ± 0.51aDC |

| 3 | Affo1968 | 19.45 ± 3.9aA | 7.51 ± 0.09aA | 112.5 ± 4.9bA | 26.25 ± 1.73aB |

| 3 | Affo1973 | 26.49 ± 2.09aA | 7.56 ± 0.06aA | 121.3 ± 4.11aA | 51.04 ± 2.45aA |

| 3 | Affo1985 | 35.05 ± 1.79aA | 7.36 ± 0.19aA | 106.17 ± 16.48aA | 5.17 ± 3.9aC |

| 3 | Affo1996 | 42.58 ± 11.86aA | 7.66 ± 0.06aA | 131.43 ± 11.65aA | 6.48 ± 1.59aC |

| 3 | Affo2002 | 18.92 ± 1.17aA | 7.43 ± 0.03aA | 89.93 ± 4.65aA | 5.47 ± 2.33aC |

| 3 | Tilled 1968 | 21.48 ± 1.99aA | 7.62 ± 0.05aA | 149.7 ± 0.3aA | 31.77 ± 0.04aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1973 | 28.65 ± 2.26aA | 7.61 ± 0.03aA | 146.1 ± 33.2aA | 46.84 ± 6.22aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1985 | 38.6 ± 12.78aA | 7.27 ± 0.03aA | 54.6 ± 11.9aA | 0.29 ± 0.21aB |

| 3 | Tilled 1996 | 31.93 ± 0.11aA | 7.32 ± 0.26aA | 88.2 ± 13.3aA | 3.73 ± 0.92aB |

| 3 | Tilled 2002 | 19.32 ± 0.15aA | 7.37 ± 0.11aA | 82.2 ± 14.3aA | 5.78 ± 4.01aB |

| 4 | Affo1968 | 19.51 ± 3.9aA | 7.54 ± 0.08aA | 108 ± 6.18bA | 27.19 ± 1.36aB |

| 4 | Affo1973 | 25.9 ± 2.99aA | 7.55 ± 0.02aA | 114.13 ± 5.28aA | 51.6 ± 4.5aA |

| 4 | Affo1985 | 33.18 ± 1.13aA | 7.44 ± 0.21aA | 108.7 ± 16.08aA | 9.69 ± 8.54aBC |

| 4 | Affo1996 | 27.01 ± 8.23aA | 7.65 ± 0.11aA | 120.03 ± 6.61aA | 2.89 ± 1.71aC |

| 4 | Affo2002 | 19.56 ± 1.71aA | 7.48 ± 0.06aA | 86.7 ± 1.88aA | 7.29 ± 2.42aBC |

| 4 | Tilled 1968 | 21.62 ± 0.73aA | 7.62 ± 0.06aA | 156.45 ± 5.05aA | 26.1 ± 2.67aB |

| 4 | Tilled 1973 | 30.08 ± 3.11aA | 7.6 ± 0.05aA | 139.85 ± 30.35aA B | 45.66 ± 4.84aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1985 | 32.28 ± 0.26aA | 7.21 ± 0.01aA | 59.8 ± 11.6aB | 0.21 ± 0.12aC |

| 4 | Tilled 1996 | 33.35 ± 5.53aA | 7.41 ± 0.29aA | 99.75 ± 12.85aA B | 4.44 ± 2.71aC |

| 4 | Tilled 2002 | 24.67 ± 2.78aA | 7.4 ± 0.07aA | 81.8 ± 12.3aA B | 3.84 ± 1.98aC |

| 5 | Affo1968 | 18.74 ± 3.4aA | 7.5 ± 0.06aA | 103.7 ± 1.38bA | 27.84 ± 2.1aAB |

| 5 | Affo1973 | 24.43 ± 2.84aA | 7.53 ± 0.05aA | 82.57 ± 35.6aA | 53.56 ± 3.93aA |

| 5 | Affo1985 | 34.31 ± 0.76aA | 7.53 ± 0.22aA | 122.97 ± 18.36aA | 12.39 ± 11.4aB |

| 5 | Affo1996 | 23.3 ± 13.28aA | 7.68 ± 0.15aA | 116.55 ± 1.85aA | 4.49 ± 2.73aB |

| 5 | Affo2002 | 22 ± 3.61aA | 7.39 ± 0.09aA | 84.4 ± 4.87aA | 5.11 ± 1.71aB |

| 5 | Tilled 1968 | 20.19 ± 0.07aC | 7.7 ± 0.1aA | 146.9 ± 3.2aA | 31.56 ± 2.1aB |

| 5 | Tilled 1973 | 34.54 ± 3.92aAB | 7.59 ± 0.03aA | 146.35 ± 32.95aA | 43.49 ± 1.41aA |

| 5 | Tilled 1985 | 32.2 ± 3.45aABC | 7.18 ± 0.01aB | 59.55 ± 12.45aA | 0.42 ± 0.08aD |

| 5 | Tilled 1996 | 36.6 ± .aA | 7.66 ± .aA | 111.5 ± .aA | 7.35 ± .aC |

| 5 | Tilled 2002 | 21.95 ± 1.23aB C | 7.31 ± 0.03aB | 87.4 ± 4.3aA | 2.44 ± 0.25aCD |

| Depth Level | Treatment | Sand % | Clay % | Silt %. | Soil Bulk Density (g cm-3) |

| 1 | Affo1968 | 53.75 ± 3.01aBC | 21.59 ± 1.69aB | 24.66 ± 3.27aA | 1.21 ± 0.03aB |

| 1 | Affo1973 | 58.84 ± 2.13aABC | 28.8 ± 1.17aA | 12.36 ± 1.61aB | 1.05 ± 0.02aC |

| 1 | Affo1985 | 63.06 ± 3.29aAB | 19.4 ± 3.13aBC | 17.54 ± 2.08aAB | 1.04 ± 0.03aC |

| 1 | Affo1996 | 48.87 ± 2.33aC | 28.8 ± 0.98bA | 22.32 ± 1.72aA | 0.98 ± 0.03aC |

| 1 | Affo2002 | 66.97 ± 1.41aAB | 12.72 ± 0.53aC | 20.32 ± 1.14aAB | 1.38 ± 0.03aA |

| 1 | Tilled 1968 | 66.49 ± 5.26bA | 26.09 ± 4.51aA | 7.41 ± 1.81bB | 1.21 ± 0.04aB |

| 1 | Tilled 1973 | 52.35 ± 1.73bB | 22.63 ± 1.89bA | 25.02 ± 1.73bA | 1.14 ± 0.04aB |

| 1 | Tilled 1985 | 49.28 ± 1.14bB | 27.84 ± 0.5bA | 22.89 ± 0.91aA | 1.04 ± 0.05aB |

| 1 | Tilled 1996 | 70.02 ± 2.19bA | 9.2 ± 0.85aB | 20.78 ± 1.69aA | 1.1 ± 0.04bB |

| 1 | Tilled 2002 | 64.87 ± 1.35aA | 13.16 ± 0.55aB | 21.97 ± 1.16aA | 1.45 ± 0.07aA |

| 2 | Affo1968 | 53.45 ± 3.92aB | 22.82 ± 2.27aBC | 23.73 ± 3.29aA | 1.28 ± 0.03aB |

| 2 | Affo1973 | 51.64 ± 2.09aB | 34.05 ± 1.37aA | 14.31 ± 1.45aC | 1.09 ± 0.03aC |

| 2 | Affo1985 | 64.4 ± 3.53aA | 20.04 ± 3.09aDC | 15.55 ± 1.87aBC | 1.05 ± 0.03aC |

| 2 | Affo1996 | 47.43 ± 1.45aB | 29.51 ± 0.92aAB | 23.05 ± 1.16aAB | 1.05 ± 0.02aC |

| 2 | Affo2002 | 67.56 ± 1.14aA | 12.97 ± 0.64aD | 19.47 ± 1.27aABC | 1.46 ± 0.05aA |

| 2 | Tilled 1968 | 67.84 ± 3.35bA | 25.76 ± 3.1aA | 6.4 ± 1.06bB | 1.29 ± 0.04aB |

| 2 | Tilled 1973 | 47.4 ± 2.51aB | 27.85 ± 2.31bA | 24.75 ± 1.3bA | 1.1 ± 0.03aC |

| 2 | Tilled 1985 | 46.27 ± 1.28bB | 28.81 ± 0.7bA | 24.92 ± 1.06bA | 1.01 ± 0.04aC |

| 2 | Tilled 1996 | 69.25 ± 2.54bA | 10.14 ± 1.07bB | 20.61 ± 1.87aA | 1.14 ± 0.04aBC |

| 2 | Tilled 2002 | 66.44 ± 1.59aA | 12.87 ± 0.67aB | 20.69 ± 1.05aA | 1.5 ± 0.06aA |

| 3 | Affo1968 | 52.94 ± 12.33aA | 24.71 ± 6.94aAB | 22.35 ± 7.32aA | 1.22 ± 0.12aA |

| 3 | Affo1973 | 41.95 ± 2aA | 38.87 ± 2.33aA | 19.18 ± 1.58aA | 1.09 ± 0.07aA |

| 3 | Affo1985 | 72.16 ± 5.22aA | 10.98 ± 3.05aB | 16.87 ± 2.6aA | 1.05 ± 0.07aA |

| 3 | Affo1996 | 51.44 ± 8.04aA | 25.43 ± 5.98aAB | 23.13 ± 3.46aA | 1.02 ± 0.03aA |

| 3 | Affo2002 | 73.59 ± 1.72aA | 10.69 ± 1.03aB | 15.71 ± 1.25aA | 1.36 ± 0.06aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1968 | 61.6 ± 6.17aA | 26.03 ± 2.35aA | 12.36 ± 3.82aA | 1.19 ± 0.04aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1973 | 65.23 ± 8.12bA | 16.94 ± 1.17bAB | 17.83 ± 9.3aA | 1.08 ± 0.03aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1985 | 46.49 ± 2.48bA | 26.05 ± 2.83bA | 27.46 ± 5.31aA | 1.07 ± 0.02aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1996 | 66.13 ± 4.06aA | 10.59 ± 0.08aB | 23.28 ± 4.14aA | 1.07 ± 0.13aA |

| 3 | Tilled 2002 | 69.81 ± 2.05aA | 12.27 ± 2.3aB | 17.92 ± 0.25aA | 1.4 ± 0.07aA |

| 4 | Affo1968 | 56.43 ± 15.96aA | 22.93 ± 7.3aAB | 20.65 ± 8.9aA | 1.23 ± 0.06aAB |

| 4 | Affo1973 | 50.77 ± 6.34aA | 38.66 ± 1.85aA | 10.58 ± 4.49aA | 1.14 ± 0.07aAB |

| 4 | Affo1985 | 65.97 ± 5.84aA | 18.33 ± 6.1aAB | 15.71 ± 2.64aA | 0.94 ± 0.08aB |

| 4 | Affo1996 | 61.74 ± 6.29aA | 19 ± 3.64aA B | 19.25 ± 2.67aA | 1.1 ± 0.01aB |

| 4 | Affo2002 | 74.71 ± 2.39aA | 8.92 ± 1.52aB | 16.37 ± 0.88aA | 1.61 ± 0.2aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1968 | 69.4 ± 3.64aA | 26.18 ± 2.57aAB | 4.42 ± 1.07aB | 1.04 ± 0.04aB |

| 4 | Tilled 1973 | 54.58 ± 7.51aA | 16.92 ± 1.29bBC | 28.49 ± 6.21aA | 1 ± 0.08aB |

| 4 | Tilled 1985 | 48.79 ± 2.68aA | 30.07 ± 1.42aA | 21.13 ± 4.1aAB | 1.01 ± 0.01aB |

| 4 | Tilled 1996 | 70.21 ± 0.24aA | 9.28 ± 1.21aC | 20.52 ± 1.45aAB | 1.26 ± 0.08aAB |

| 4 | Tilled 2002 | 73.62 ± 5.98aA | 11.12 ± 3.69aC | 15.26 ± 2.28aAB | 1.46 ± 0.11aA |

| 5 | Affo1968 | 57.27 ± 10.42aAB | 22.88 ± 6.67aAB | 19.85 ± 4.44aA | 1.28 ± 0.07aAB |

| 5 | Affo1973 | 43.06 ± 5.76aB | 38.72 ± 3.29aA | 18.22 ± 3.69aA | 1.09 ± 0.08aB |

| 5 | Affo1985 | 65.11 ± 6.45aAB | 21.14 ± 5.5aAB | 13.76 ± 1.07aA | 1.09 ± 0.09aB |

| 5 | Affo1996 | 58.92 ± 10.48aAB | 20.4 ± 2.12aAB | 20.68 ± 12.6aA | 1.1 ± 0.01aB |

| 5 | Affo2002 | 75.52 ± 2.75aA | 8 ± 0.7aB | 16.48 ± 2.1aA | 1.53 ± 0.1aA |

| 5 | Tilled 1968 | 73.32 ± 2.66aA | 20.92 ± 2.67aAB | 5.76 ± 0.01aC | 1.21 ± 0.02aAB |

| 5 | Tilled 1973 | 51.83 ± 2.72aA | 19.43 ± 1.28bAB | 28.74 ± 1.44aA | 1.06 ± 0.09aB |

| 5 | Tilled 1985 | 56.79 ± 7.97aA | 24.85 ± 3.82aA | 18.35 ± 4.15aAB | 1.09 ± 0.1aB |

| 5 | Tilled 1996 | 70.02 ± .aA | 8.01 ± .aB | 21.97 ± .aA B | 1.14 ± .aB |

| 5 | Tilled 2002 | 77.25 ± 4.81aA | 8.52 ± 3.56aB | 14.23 ± 1.25aBC | 1.55 ± 0.02aA |

| Depth Level | Treatment | SIOC (%) | TSC (%) | SOC (%). | N (%) |

| 1 | Affo1968 | 2.71 ± 0.14aB | 3.82 ± 0.22aB | 1.1 ± 0.25aA | 0.17 ± 0.02aB |

| 1 | Affo1973 | 5.54 ± 0.14aA | 6.36 ± 0.21aA | 0.82 ± 0.2aA | 0.21 ± 0.01aB |

| 1 | Affo1985 | 0.31 ± 0.07aD | 1.18 ± 0.09aC | 0.86 ± 0.06aA | 0.2 ± 0.01aB |

| 1 | Affo1996 | 0.91 ± 0.11aC | 1.91 ± 0.23aC | 1.01 ± 0.26aA | 0.32 ± 0.05bB |

| 1 | Affo2002 | 0.25 ± 0.04aD | 1.23 ± 0.15aC | 0.98 ± 0.18aA | 1.61 ± 0.29aA |

| 1 | Tilled 1968 | 3.4 ± 0.15bB | 4.38 ± 0.34aB | 0.98 ± 0.27aB C | 0.23 ± 0.02aC |

| 1 | Tilled 1973 | 5.99 ± 0.09bA | 6.47 ± 0.11aA | 0.48 ± 0.13aC | 0.2 ± 0.01aC |

| 1 | Tilled 1985 | 0.05 ± 0.01bD | 1.38 ± 0.12aD | 1.33 ± 0.12bB | 0.23 ± 0.01bC |

| 1 | Tilled 1996 | 0.56 ± 0.05bC | 2.78 ± 0.18bC | 2.22 ± 0.15bA | 3.08 ± 0.51aA |

| 1 | Tilled 2002 | 0.19 ± 0.02aD | 1.02 ± 0.14aD | 0.84 ± 0.13aB C | 1.56 ± 0.18aB |

| 2 | Affo1968 | 2.83 ± 0.13aB | 4.1 ± 0.35aB | 1.27 ± 0.34aA | 0.2 ± 0.02aB |

| 2 | Affo1973 | 5.49 ± 0.11aA | 6.11 ± 0.13aA | 0.62 ± 0.12aA | 0.21 ± 0.01aB |

| 2 | Affo1985 | 0.33 ± 0.08aD | 1.08 ± 0.08aC | 0.75 ± 0.07aA | 0.2 ± 0.01aB |

| 2 | Affo1996 | 0.88 ± 0.11aC | 1.61 ± 0.25aC | 0.73 ± 0.23aA | 0.36 ± 0.1aB |

| 2 | Affo2002 | 0.31 ± 0.03aD | 1.06 ± 0.12aC | 0.75 ± 0.14aA | 1.48 ± 0.25aA |

| 2 | Tilled 1968 | 3.63 ± 0.09bB | 4.18 ± 0.15aB | 0.55 ± 0.17aB | 0.22 ± 0.01aB |

| 2 | Tilled 1973 | 5.96 ± 0.17bA | 6.49 ± 0.14aA | 0.54 ± 0.13aB | 0.19 ± 0.01aB |

| 2 | Tilled 1985 | 0.06 ± 0.01bD | 1.14 ± 0.12aD | 1.08 ± 0.12bB | 0.22 ± 0.01aB |

| 2 | Tilled 1996 | 0.47 ± 0.06bC | 2.8 ± 0.26bC | 2.33 ± 0.27bA | 3.41 ± 0.75bA |

| 2 | Tilled 2002 | 0.27 ± 0.06aD C | 1.12 ± 0.24aD | 0.84 ± 0.2aB | 1.51 ± 0.13aB |

| 3 | Affo1968 | 3.15 ± 0.21aB | 3.88 ± 0.29aB | 0.73 ± 0.49aA | 0.2 ± 0.02aA |

| 3 | Affo1973 | 6.12 ± 0.29aA | 6.12 ± 0.29aA | 0 ± 0aA | 0.18 ± 0.01aA |

| 3 | Affo1985 | 0.62 ± 0.47aC | 1.24 ± 0.39aC | 0.62 ± 0.15aA | 0.2 ± 0.02aA |

| 3 | Affo1996 | 0.78 ± 0.19aC | 1.03 ± 0.09aC | 0.25 ± 0.25aA | 0.23 ± 0.05aA |

| 3 | Affo2002 | 0.66 ± 0.28aC | 1.38 ± 0.48aC | 0.72 ± 0.69aA | 0.82 ± 0.43aA |

| 3 | Tilled 1968 | 3.81 ± 0aA | 4.05 ± 0.24aA B | 0.24 ± 0.24aB | 0.17 ± 0.01aB |

| 3 | Tilled 1973 | 5.62 ± 0.75aA | 5.69 ± 0.82aA | 0.07 ± 0.07aB | 0.2 ± 0aB |

| 3 | Tilled 1985 | 0.03 ± 0.02aB | 0.55 ± 0.23aC | 0.51 ± 0.21aA B | 0.12 ± 0.02aB |

| 3 | Tilled 1996 | 0.45 ± 0.11aB | 2.79 ± 0.42bB C | 2.34 ± 0.31bA | 2.92 ± 0.96bA |

| 3 | Tilled 2002 | 0.69 ± 0.48aB | 1.52 ± 0.13aC | 0.83 ± 0.62aA B | 1.55 ± 0.11aA B |

| 4 | Affo1968 | 3.26 ± 0.16aB | 3.81 ± 0.52aA B | 0.54 ± 0.36aA | 0.95 ± 0.73aA |

| 4 | Affo1973 | 6.19 ± 0.54aA | 6.26 ± 0.55aA | 0.06 ± 0.06aA | 0.22 ± 0.02aA |

| 4 | Affo1985 | 1.16 ± 1.02aB C | 1.82 ± 0.95aB C | 0.65 ± 0.1aA | 0.18 ± 0.04aA |

| 4 | Affo1996 | 0.35 ± 0.21aC | 0.51 ± 0.22aC | 0.16 ± 0.16aA | 0.15 ± 0.05aA |

| 4 | Affo2002 | 0.88 ± 0.29aB C | 0.94 ± 0.22aC | 0.07 ± 0.07aA | 1.09 ± 0.54aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1968 | 3.13 ± 0.32aB | 3.38 ± 0.57aB | 0.25 ± 0.25aB | 0.16 ± 0aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1973 | 5.48 ± 0.58aA | 5.71 ± 0.35aA | 0.23 ± 0.23aB | 0.18 ± 0.01aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1985 | 0.03 ± 0.01aC | 0.98 ± 0.22aC | 0.96 ± 0.21aB | 0.19 ± 0.02aA |

| 4 | Tilled 1996 | 0.53 ± 0.33aC | 2.86 ± 0.5bB C | 2.33 ± 0.17bA | 3.7 ± 1.62bA |

| 4 | Tilled 2002 | 0.46 ± 0.24aC | 0.68 ± 0.02aC | 0.21 ± 0.21aB | 1.54 ± 0.44aA |

| 5 | Affo1968 | 3.34 ± 0.25aA B | 3.47 ± 0.32aB | 0.13 ± 0.07aA | 0.16 ± 0.01aB |

| 5 | Affo1973 | 6.43 ± 0.47aA | 6.58 ± 0.39aA | 0.16 ± 0.12aA | 0.16 ± 0.02aB |

| 5 | Affo1985 | 1.49 ± 1.37aB | 1.96 ± 1.16aB | 0.47 ± 0.31aA | 0.19 ± 0.03aB |

| 5 | Affo1996 | 0.54 ± 0.33aB | 0.75 ± 0.12aB | 0.21 ± 0.21aA | 0.18 ± 0.06aB |

| 5 | Affo2002 | 0.61 ± 0.2aB | 1.11 ± 0.61aB | 0.5 ± 0.5aA | 1.68 ± 0.68aA |

| 5 | Tilled 1968 | 3.79 ± 0.25aB | 4.52 ± 0.49aA B | 0.73 ± 0.24aA | 0.2 ± 0.03aC |

| 5 | Tilled 1973 | 5.22 ± 0.17aA | 5.22 ± 0.17aA | 0 ± 0aA | 0.17 ± 0.03aC |

| 5 | Tilled 1985 | 0.05 ± 0.01aD | 0.38 ± 0.13aC | 0.33 ± 0.12aA | 0.16 ± 0.02aC |

| 5 | Tilled 1996 | 0.88 ± .aC | 2.66 ± .aB C | 1.78 ± .aA | 3.32 ± .bA |

| 5 | Tilled 2002 | 0.29 ± 0.03aC D | 1.16 ± 0.84aC | 0.87 ± 0.87aA | 1.79 ± 0.05aB |

| Sample | Treatment | N (%) ± Std. Err. | C (%) ± Std. Err. |

| Litter | Affor1968 | 1.67 ± 0.65a | 45.41 ± 0.78a |

| Litter | Affor1973 | 0.41 ± 0.09b | 48.25 ± 1.21a |

| Litter | Affor1985 | 0.4 ± 0.09b | 47.9 ± 1.22a |

| Litter | Affor1996 | 0.51 ± 0.08a b | 46.68 ± 1.24a |

| Litter | Affor2002 | 0.46 ± 0.09a b | 47.58 ± 0.85a |

| Humus | Affor1968 | 1.12 ± 0.36a | 46.2 ± 0.78a |

| Humus | Affor1973 | 0.5 ± 0.13a b | 32.94 ± 8.33a b |

| Humus | Affor1985 | 0.3 ± 0.09b | 29.95 ± 7.52a b |

| Humus | Affor1996 | 0.02 ± 0.02b | 14.79 ± 7.4b c |

| Humus | Affor2002 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).