1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) accounts for approximately 5% of female cancer-related mortality globally [

1]. It is the most lethal malignancy in gynecology with less than 20% 5-year overall survival in advance stage [

2]. OC is characterized by high frequent mutation of TP53, a well-known tumor suppressor. For high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC), over 96% of patients were found to carry TP53 gene mutations [

3]. Mutant P53 (mtP53) proteins are associated with either loss tumor-suppressive function (loss-of-function, LOF) or acquire oncogenic activities (gain-of-function, GOF), relating to tumor progress [

4]. Therefore, P53 became a hot target for HGSC treatment and intensive efforts have been made to restore wild type P53 (wtP53) activity for OC therapy [

5,

6,

7].

As a potent anti-cancer natural compound, Arctigenin (ATG) suppresses a number of cancer types [

8]. However, its biological effects on OC are barely reported. Initially, we aimed to study the effect of ATG on OC cell proliferation, and found ATG inhibited OC cells proliferation depending on low glucose condition. Then we studied the influence of ATG on P53 expressions using several OC cell lines. Surprisingly, ATG treatment reversely regulated P53 expression across these cell lines. To reveal the underlying mechanism of P53 regulation by ATG, we systematically analyzed its activities involved in human diseases treatments [

9] and validated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) accounted for the ATG-mediated P53 regulations.

In early stage, GSK3β was considered as a driving force in OC progress [

10]. However, its exact biofunction in OC is now a matter of controversial debate. It exerts both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing effects on OC [

11], indicating GSK3β could not be defined as a simple tumor-promotor or tumor-suppressor for OC. In anti-tumor side, GSK3β inhibits cancer development via impeding multiple tumor biological process, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion and therapy resistance [

12]. A recent study showed its anti-tumor potential also involved DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway [

13]. In this study, we not only showed the role of GSK3β in P53 regulation, but also confirmed its activity in homogenous recombination (HR) pathway for DNA damage repair. Moreover, we uncovered GSK3β governed the Aurora A (Aur-A)/PLK1 axis which closely related to DDR and P53 expression and further validated the synergistic anti-OC effects via double inhibition of GSK3β and PLK1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

A2780 (RRID:CVCL_0134), ES-2 (RRID:CVCL_3509), OVCAR-8 (RRID:CVCL_1629), Hey (RRID:CVCL_0297) , OVCAR-3 (RRID:CVCL_0465) and Kuramochi (RRID:CVCL_1345) cells were purchased from Immocell Biotechnology company (Xiamen, China). All cell lines were authenticated using short tandem repeat profiling by ATCC or the Roswell Park Core. Cells were cultured as recommended by the instructions from ATCC.

2.2. Chemicals and Antibodies

MK2206 (A3010, APExBIO, USA), Pifithrin-α (A4206, APExBIO, USA), KU-55933 (A4605, APExBIO, USA), Bleomycin sulfate (A8331, APExBIO, USA), Etoposide (A1971, APExBIO, USA) were obtained from APExBIO Technology. TWS-119 (601514-19-6, Tsbiochem, USA) was obtained from TargetMol Chemicals. Alisertib (S80032, MedMol, China) was obtained from Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology. GSK461364 (929095-18-1, MCE, USA) was obtained from MedChemExpress LLC. The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: β-actin (811115-1-RR, Proteintech, China), p-PLK1 (Thr210) (AB155095, Abcam, UK), PLK1 (4513, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), GAPDH (60004-1-Ig, Proteintech, China), p-GSK3β (Ser9) (5558, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), GSK3β (12456, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), P53 (10442-1-AP, Proteintech, China), p-AKT (Ser473) (9271, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), AKT (9272, Proteintech, China), Aurora A (14475, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), p-H2AX (Ser139) (9718, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Cleaved Caspase-3 (ASP175) (9661, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), P53 (2524, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), FLAG (DDDK-tag) (AB1162, Abcam, UK).

2.3. CCK-8 Assay

Cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 1104/well for 24 hours, and then cell culture medium was renewed and agents were added to treat cells. 48 hours later, cell proliferation was determined by cell counting kit-8 assay (CK04-100T, Dojindo, Japan). Data were obtained by measuring the optical density at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Cytation5, Biotek, USA).

2.4. Construct

cDNAs encoding full-length ORFs of GSK3β was amplified by PCR using total RNA of OVCAR-8 cell and cloned into NotI and XhoI restriction site of pEF-BOS using In-fusion cloning (638910, TaKaRa, Japan). A Flag tag sequence was inserted between the start codon and the N-terminus of GSK3β.

2.5. Lentiviral Transduction

pLKO.1 puro lentiviral vector (8453, Addgene, USA) was used to express short hairpin RNA (shRNA). GSK3β shRNAs are targeting the following sequences: 5′-CATGAAAGTTAGCAGAGACAA-3′ (shRNA.1) and 5′-GTGTGGATCAGTTGGTAGAAA-3′ (shRNA.2). An shRNA with the nontargeting sequence 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTAA-3′ was used as a negative control.

Cancer cell lines and were transduced with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. 48 hours after transduction, cells were selected with puromycin (3 mg/ml) for 3 days.

2.6. RNA Isolation, RT-qPCR and RNA-seq

RNA was isolated using a RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, 74134) and then used for cDNA synthesis (6210A, Takara, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a SYBR Green master mix (MQ10401S, Monad, China) and β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene. The following primer pairs were used: β-actin forward CAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCCGATC and reverse CATCCATGGTGAGCTGGCGGCG;P53 forward AAGTCTGTGACTTGCACGTACTCC and reverse GTCATGTGCTGTG-ACTGCTTGTAG; MDM2 forward GGGAGTGATCAAAAGGACCT and reverse CC-AAATGTGAAGATGAAGGTTTC; CDKN1A forward CTTGTACCCTTGTGCCTCGC and reverse GCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGAAATCTGT; PIDD1 forward CTCACCCACCT-GTACGCAC and reverse CAGAGCGATGAGGTTCACAC. Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol Reagent (15596026, Thermo Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. For library preparation, total RNA was used as input for RNA sequencing library preparation utilizing the KCTM mRNA Library Prep Kit (Seqhealth Tech, Wuhan, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The library preparation included the enrichment of PCR products corresponding to fragments ranging from 200 to 500 base pairs. The enriched libraries were quantified and sequenced on a DNBSEQ-T7 platform (MGI, China) using the PE150 sequencing mode to generate paired-end reads.

2.7. Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested with RIPA buffer (AR0102, BOSTER, China) with protease inibitor mixtures (P8340, Sigma, USA). Samples were separated on 8-12.5% SDS PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (88520, Thermo Fisher, USA), which were subsequently blocked with skim milk (D8340, Solarbio, China) for 60 minutes. Afterwards, membranes were probed with the primary antibodies, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse (SA00012-1, Proteintech, China) or anti-rabbit (SA00001-2, Proteintech, China) secondary antibody diluted 1:5000-10000. The intensity of protein bands was quatified by Image Lab (ChemiDoc MP, BioRad, USA) and data were analyzed by ImageJ (SCR_003070, USA).

2.8. Flow Cytometry

Apoptotic cells were identified by an annexin V and PI staining kit Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis kit (KGA108, KeyGen Biotech, China) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Percentages of cells in different phases of cell cycle analyzed by a cell cycle analysis kit (KGA511) were detected by flow cytometer (CytoFLEX, Beckman, USA) and data were processed using FlowJo 10.0.7 (FlowJo LLC, USA).

2.9. Immunofluorescence Staining

A DNA damage detection kit (Dojindo, DK02) were utilized for visualizing γH2AX staining. Cells were seeded onto confocal dishes (20mm, NEST) at a density of 2.5105/well and fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Dishes were washed with PBS for three times. Permeabilization was performed for 5 min with 0.1% Triton in PBS. After washing the dishes with PBS for 3 times, cells were blocked with 1% BSA for 20 min. Cells were incubated with anti-γH2AX (1:50) antibody for 1 hour at dark, and subsequently incubated with the secondary antibody staining solution for 1 hour. Afterwards, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 5 min (Beyotime, China), the fluorescence signal was visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany)

2.10. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software version 9 (SCR_002798, USA) was used to conduct statistical analyses and produce graphs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Unpaired t-tests, Mann-Whitney and one-way ANOVA were used for the comparison of significant differences between groups.

2.11. Data Availability

All raw data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

4. Discussion

In this study, we tried to explain the differentiated regulation of P53 by ATG in OC cells and revealed the vital role of GSK3β in P53 regulation. We focused on P53 because it had broad roles in OC malignancy and gained enduring attentions on target therapy grounded in it [

7]. Initially, we studied the P53 expression profiles in OC cells following ATG treatment and found the inverse effects of GSK3β on P53 regulation. To explore the underlying mechanisms, we put forward some hypotheses and obtained some findings. Importantly, we confirmed GSK3β inhibition induced DNA damages in all OC cells (

Figure 3A and B). Comparative transcriptomics between control and TWS-119-treated groups in A2780 cells showed HR pathway was significantly impaired by GSK3β inhibition (

Figure 3F). Errors during DNA replication frequently causes endogenous DNA damages giving rise to double-strand break (DSB) which requires HR pathway for high-fidelity repair [

35]. Therefore, the impaired HR pathway by GSK3β could impede repairing for DSB and inevitably increased DNA damage. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) responses to DSB repair and activates downstream P53 signaling [

36]. A specific ATM kinase inhibitor completely blocked the upregulated P53 by GSK3β inhibition in both A2780 and ES-2 cells (

Figure 3G), demonstrating the GSK3β-mediated P53 upregulation pertained to DDR pathway.

For OVCAR-8 and Kuramochi cells, it was surprising that although DNA damages were markedly induced following GSK3β inhibition, P53 was downregulated (

Figure 1E and F). P53 activity had a role in protection against DNA damage, as shown in A2780 and ES-2 cells (

Figure 4C). To test whether P53 failed to response to DNA damage in OVCAR-8 cells, we used some exogenous DNA damage-inducing agents for treating cells. P53 responses to these agents in OVCAR-8 cells were markedly less sensitive than A2780 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1B), indicating the DNA damage-mediated P53 signaling was faint but still alive in OVCAR-8 cells. However, facing the DNA damage caused by GSK3β inhibition, OVCAR-8 and Kuramochi cells decided to downregulate P53 expression and the underlying biological significance remains to be investigated. Here, we validate GSK3β have dual effects on P53 regulation and the correlation between GSK3β and P53 could be either positive or negative. In human primary OV cells, GSK3β and P53 are positively correlated, suggesting the positive regulation of P53 by GSK3β is dominant in human primary OV cells (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Regretfully, our efforts failed to disclosed the mechanism underlying the GSK3β-mediated P53 downregulation. In this sense, our work could be defined as more descriptive than explanative. Nevertheless, our study generated some interesting and valuable findings. we identified the GSK3β/Aur-A/PLK1 axis functioning in DDR pathway, which was previously unreported, to best of our knowledge. Double inhibition of GSK3β and PLK1 cooperatively induce DNA damage and cell apoptosis in some OC cells, which provided a novel therapy strategy for OC. As drug synergy effect was not evident in Kuramochi cells, one explanation is Kuramochi cells proliferates more slowly than other OC cells (data not shown). As fast DNA replication inevitably brings about DNA damage [

37], cells of low proliferation rate could have more opportunity for dealing with DNA damage thus reducing its accumulation.

Targeting GSK3β for OC therapy has been intensively studied and some inhibitors specific to GSK3β were applied for clinical studies [

11]. However, the role of GSK3β in OV development aroused a controversy and some researchers believed activation of GSK3β helped to impede OV progress [

11]. This disagreement revealed that for better use of GSK3β inhibitors for OC treatment, its overall effects should be comprehensively considered. Our findings demonstrated activated PLK1 was activated upon GSK3β suppression. Considering PLK1 is overexpressed and associated with poor prognosis in many cancers [

38], double inhibition of GSK3β and PLK1 could be reasonable if their in-vivo drug toxicities were tolerable. Moreover, given the GOF function of some mtP53s in OC progress such as R172H and R248 [

39,

40] and a majority of OC samples were determined as P53-mutant [

7], to lower down mtP53 level in OC cells by GSK3β might have benefits for therapy. Taken together, our study favored the GSK3β inhibitor for OV therapy and highlighted the GSK3β/Aur-A/PLK1 axis in DDR pathway. We believe double inhibition of GSK3β and PLK1 could be a promising therapeutic intervention for OC and plan to validate its in-vivo anti-tumor effect in future.

Figure 1.

ATG differently shapes P53 protein abundance across OV cell lines. (A) OVCAR-8 and (B) A2780 cells were cultured in DMEM low glucose (1.0g/L) or DMEM high glucose (4.5g/L) and treated by ATG (5-50 μM) for 48 hours, and then cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay with control group (0 μM ATG, low glucose) normalized as 1. (C) A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose culture (4.5g/L glucose) and treated by ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay with each control groups (0 μM ATG) were normalized as 1. Cell viability was presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, unpaired Student t test, compared with viability controls. (D) Western blot of P53 in A2780 cells exposed to ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours under low and high glucose conditions. (E) Western blot of P53 in OVCAR-8 and HEY cells exposed to ATG for 24 hours. (F) Western blot of P53 in ES-2, OVCAR-3 and Kuramochi cells exposed to ATG for 24 hours.

Figure 1.

ATG differently shapes P53 protein abundance across OV cell lines. (A) OVCAR-8 and (B) A2780 cells were cultured in DMEM low glucose (1.0g/L) or DMEM high glucose (4.5g/L) and treated by ATG (5-50 μM) for 48 hours, and then cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay with control group (0 μM ATG, low glucose) normalized as 1. (C) A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose culture (4.5g/L glucose) and treated by ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay with each control groups (0 μM ATG) were normalized as 1. Cell viability was presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, unpaired Student t test, compared with viability controls. (D) Western blot of P53 in A2780 cells exposed to ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours under low and high glucose conditions. (E) Western blot of P53 in OVCAR-8 and HEY cells exposed to ATG for 24 hours. (F) Western blot of P53 in ES-2, OVCAR-3 and Kuramochi cells exposed to ATG for 24 hours.

Figure 2.

GSK-3β regulates P53 protein in OV cells. (A) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and HEY cells exposed to ATG (50 μM) for 24 hours. MG132 (10 μM) was supplemented 6 hours prior to cell harvest. (B) A2780 cell were treated by ATG (50 μM) for 24 hours, and then stained by DCFH-DA according to manuscription. ROS level was assessed by flow cytometry. (C)Western blot of phospho-AKT (ser473) and AKT in A2780 after exposure to ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. (D) Western blot of phospho-GSK3β (ser9), GSK3β in OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells exposed to ATG (50 μM). (E) Western blot of P53 and GSK3β in OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells transfected with lentivirus-shCtrl (control shRNA) or shGSK3β (1# and 2#). (F) OVCAR-8 cells (5×105 cells/group) were transfected with vector control or GSK3β-FLAG-expressing vector (0.5-2μg) for 24 hours and then P53, FLAG-GSK3β expressions were detected by western blot. (G) Western blot of P53 in A2780 exposed to MK2206 (1-20 μM) for 24 hous. (H) Western blot of P53 in A2780, ES-2, OVCAR-8 and Kuramochi cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (I) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells exposed to ATG (50 μM), TWS-119 (5 μM) alone or combination of ATG (50 μM) and TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. A, ATG. T, TWS-119.

Figure 2.

GSK-3β regulates P53 protein in OV cells. (A) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and HEY cells exposed to ATG (50 μM) for 24 hours. MG132 (10 μM) was supplemented 6 hours prior to cell harvest. (B) A2780 cell were treated by ATG (50 μM) for 24 hours, and then stained by DCFH-DA according to manuscription. ROS level was assessed by flow cytometry. (C)Western blot of phospho-AKT (ser473) and AKT in A2780 after exposure to ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. (D) Western blot of phospho-GSK3β (ser9), GSK3β in OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells exposed to ATG (50 μM). (E) Western blot of P53 and GSK3β in OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells transfected with lentivirus-shCtrl (control shRNA) or shGSK3β (1# and 2#). (F) OVCAR-8 cells (5×105 cells/group) were transfected with vector control or GSK3β-FLAG-expressing vector (0.5-2μg) for 24 hours and then P53, FLAG-GSK3β expressions were detected by western blot. (G) Western blot of P53 in A2780 exposed to MK2206 (1-20 μM) for 24 hous. (H) Western blot of P53 in A2780, ES-2, OVCAR-8 and Kuramochi cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (I) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and OVCAR-8 cells exposed to ATG (50 μM), TWS-119 (5 μM) alone or combination of ATG (50 μM) and TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. A, ATG. T, TWS-119.

Figure 3.

DNA damage caused by GSK3β inhibition leads to increase P53 expression in A2780 and ES-2 cells. (A) Cells were exposed to DMSO or TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours and then γH2AX foci was visualized by immunofluorescence staining in A2780, ES-2, OVCAR-8, and Kuramochi cells. Scale bar, 100 μM. (B) Comparison of γH2AX expression between GSK3β knockdown and control groups derived from OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells. (C) *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 vs. vehicle. n = 3, Mann-Whitney test for A, (D) *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 vs. shControl. n = 3, Mann-Whitney test for (B). (E) GSEA of genes related to homologous recombination and regulation of response to DNA damage across genes ranked according to their expression level in A2780 cells treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours vs Vehicle. (F) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and ES-2 cells exposed to DMSO, TWS-119 (5 μM) or TWS-119 (5 μM) plus Ku-55933 for 24 hours.

Figure 3.

DNA damage caused by GSK3β inhibition leads to increase P53 expression in A2780 and ES-2 cells. (A) Cells were exposed to DMSO or TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours and then γH2AX foci was visualized by immunofluorescence staining in A2780, ES-2, OVCAR-8, and Kuramochi cells. Scale bar, 100 μM. (B) Comparison of γH2AX expression between GSK3β knockdown and control groups derived from OVCAR-8 and A2780 cells. (C) *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 vs. vehicle. n = 3, Mann-Whitney test for A, (D) *P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01 vs. shControl. n = 3, Mann-Whitney test for (B). (E) GSEA of genes related to homologous recombination and regulation of response to DNA damage across genes ranked according to their expression level in A2780 cells treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours vs Vehicle. (F) Western blot of P53 in A2780 and ES-2 cells exposed to DMSO, TWS-119 (5 μM) or TWS-119 (5 μM) plus Ku-55933 for 24 hours.

Figure 4.

P53 alleviates DNA damage caused by GSK3β inhibition in A2780 and ES-2 cells. (A) Bubble plot of top 12 items of biological process based on GO analysis of the upregulated genes in TWS-119-treated A2780 cells. (B) Venn diagram of the upregulated genes in TWS-119-treated A2780 cells relating to P53 signaling pathway and biological procession of DNA damage response by P53 class mediate. (C) Western blot of γH2AX in A2780 and ES-2 cells treated by Pifithrin-α (20 μM), TWS-119 (5 μM) or Pifithrin-α combined with TWS-119 for 24 hours. (D) and (E), Effects of TWS-119 on the mRNA levels of P53, MDM2, CDKN1A and PIDD1 in A2780 and ES-2 cells. qRT-PCR assay was performed with each gene in control group normalized as 1. Cells were treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. Fold changes was presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, unpaired Student t test, compared with controls. (F) A2780 and ES-2 cells treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours were labeled by DAPI and specific antibodies against P53, γH2AX for confocal microscopy analysis. Scale bar, 10 μM.

Figure 4.

P53 alleviates DNA damage caused by GSK3β inhibition in A2780 and ES-2 cells. (A) Bubble plot of top 12 items of biological process based on GO analysis of the upregulated genes in TWS-119-treated A2780 cells. (B) Venn diagram of the upregulated genes in TWS-119-treated A2780 cells relating to P53 signaling pathway and biological procession of DNA damage response by P53 class mediate. (C) Western blot of γH2AX in A2780 and ES-2 cells treated by Pifithrin-α (20 μM), TWS-119 (5 μM) or Pifithrin-α combined with TWS-119 for 24 hours. (D) and (E), Effects of TWS-119 on the mRNA levels of P53, MDM2, CDKN1A and PIDD1 in A2780 and ES-2 cells. qRT-PCR assay was performed with each gene in control group normalized as 1. Cells were treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. Fold changes was presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, unpaired Student t test, compared with controls. (F) A2780 and ES-2 cells treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours were labeled by DAPI and specific antibodies against P53, γH2AX for confocal microscopy analysis. Scale bar, 10 μM.

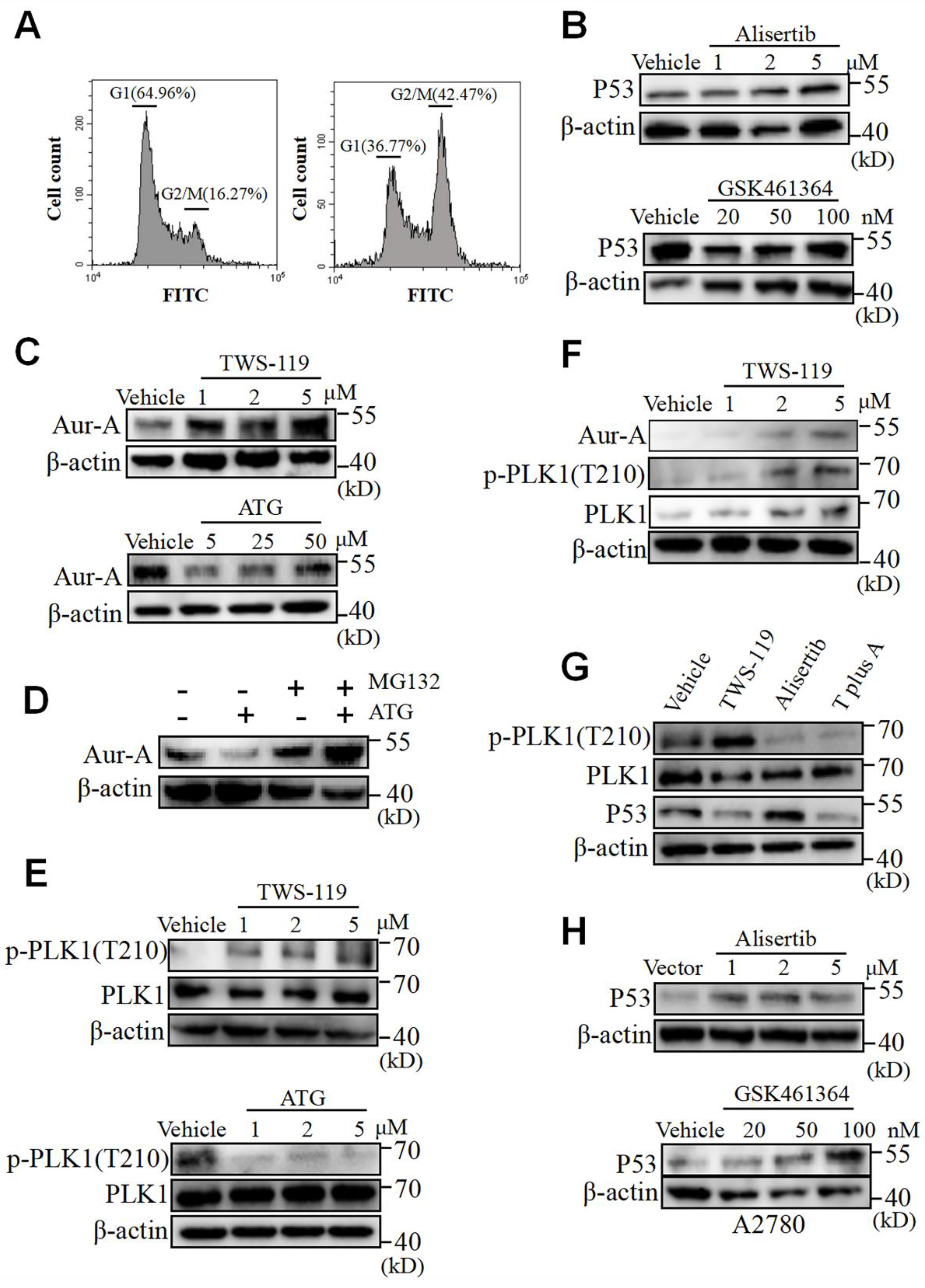

Figure 5.

GSK3β triggers Aurora A/PLK1 axis which regulates P53 expressions in OV cells. (A) OVCAR-5 was treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) or vehicle for 24 hours prior to detection of cell cycle distribution by flowcytometry. Percentages of cells at G1 and G2/M phases was determined by FlowJo software. (B) Western blot of P53 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to Alisertib (1-5 μM) or GSK461364 (1-5 μM) for 24 hours. (C) Western blot of Aurora A in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (1-5 μM) or ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. (D) Western blot of Aurora A in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) in the presence or absence of MG132 (10 μM). MG132 was supplemented to cell culture 6 hours prior to cell harvest. (E) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210) and total PLK1 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (F) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210), total PLK1 and P53 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM), Alisertib (5 μM), or TWS-119 combined with Alisertib for 24 hours. (G) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210) and total PLK1 in A2780 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (H) Western blot of P53 in A2780 cells exposed to Alisertib (1-5 μM) or GSK461364 (1-5 μM) for 24 hours.

Figure 5.

GSK3β triggers Aurora A/PLK1 axis which regulates P53 expressions in OV cells. (A) OVCAR-5 was treated by TWS-119 (5 μM) or vehicle for 24 hours prior to detection of cell cycle distribution by flowcytometry. Percentages of cells at G1 and G2/M phases was determined by FlowJo software. (B) Western blot of P53 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to Alisertib (1-5 μM) or GSK461364 (1-5 μM) for 24 hours. (C) Western blot of Aurora A in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (1-5 μM) or ATG (5-50 μM) for 24 hours. (D) Western blot of Aurora A in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) in the presence or absence of MG132 (10 μM). MG132 was supplemented to cell culture 6 hours prior to cell harvest. (E) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210) and total PLK1 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (F) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210), total PLK1 and P53 in OVCAR-8 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM), Alisertib (5 μM), or TWS-119 combined with Alisertib for 24 hours. (G) Western blot of Phospho-PLK1 (Thr210) and total PLK1 in A2780 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM) for 24 hours. (H) Western blot of P53 in A2780 cells exposed to Alisertib (1-5 μM) or GSK461364 (1-5 μM) for 24 hours.

Figure 6.

Double inhibition of PLK1 and GSK3β lead to synthetic lethality in OV cells. (A) Western blot of γH2AX in OVCAR-8, ES-2, Kuramochi and A2780 cells exposed to GSK461364 (20-100 nM) for 24 hours. (B) Western blot of γH2AX and Cleaved caspase-3 in OVCAR-8, ES-2, Kuramochi and A2780 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM), GSK461364 (100 nM) or combination of TWS-119 (5 μM) and GSK461364 (100 nM) for 24 hours. (C) Cells were treated by TWS-119 (5 μM), GSK461364 (100 nM) or combination of TWS-119 (5 μM) and GSK461364 (100 nM) for 36 hours prior to double staining with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI). Percentages of apoptotic cells were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001, n = 3, one-way ANOVA. (D) the landscapes of the combination responses for TWS-119 and GSK461364 based on loewe model.

Figure 6.

Double inhibition of PLK1 and GSK3β lead to synthetic lethality in OV cells. (A) Western blot of γH2AX in OVCAR-8, ES-2, Kuramochi and A2780 cells exposed to GSK461364 (20-100 nM) for 24 hours. (B) Western blot of γH2AX and Cleaved caspase-3 in OVCAR-8, ES-2, Kuramochi and A2780 cells exposed to TWS-119 (5 μM), GSK461364 (100 nM) or combination of TWS-119 (5 μM) and GSK461364 (100 nM) for 24 hours. (C) Cells were treated by TWS-119 (5 μM), GSK461364 (100 nM) or combination of TWS-119 (5 μM) and GSK461364 (100 nM) for 36 hours prior to double staining with Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI). Percentages of apoptotic cells were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; *** P < 0.001, n = 3, one-way ANOVA. (D) the landscapes of the combination responses for TWS-119 and GSK461364 based on loewe model.