Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

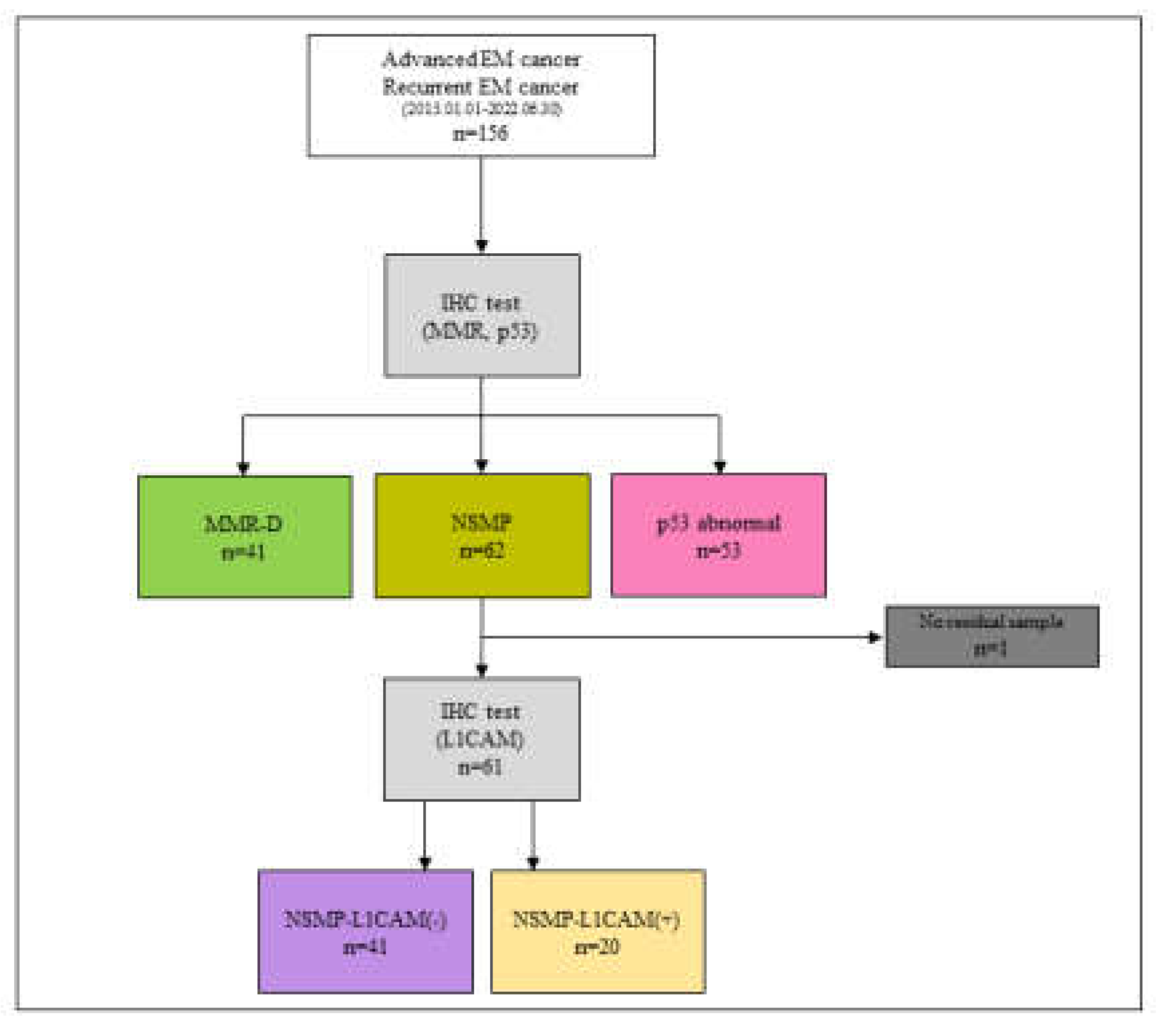

3.1. Flow Diagram (Figure 1)

3.2. Study Demographics(Table 1)

| MMR-D (N=41) |

MMR-proficient | Total (N=155) |

p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSMP-L1CAM(-) (N=41) |

NSMP-L1CAM(+) (N=20) |

p53abn (N=53) |

|||||

| Age(years) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 51.7(±9.5) | 55.6(±10.7) | 60.1(±9.4) | 59.6(±10.7) | 56.5(±10.7) | 0.001 | |

| BMI | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 23.7(±4.5) | 25.4(±4.0) | 23.5(±3.9) | 25.2(±5.3) | 24.6(±4.6) | 0.201 | |

| Parity | |||||||

| 0 | 17(41.5%) | 11(26.8%) | 6(30.0%) | 10(18.9%) | 44(28.4%) | 0.117 | |

| 1 or more | 24(58.5%) | 30(73.2%) | 14(70.0%) | 43(81.1%) | 111(71.6%) | ||

| Diabetes | |||||||

| No | 35(85.4%) | 33(80.5%) | 17(85.0%) | 46(86.8%) | 131(84.5%) | 0.863 | |

| Yes | 6(14.6%) | 8(19.5%) | 3(15.0%) | 7(13.2%) | 24(15.5%) | ||

| Prior malignancies | |||||||

| No | 38(92.7%) | 41(100.0%) | 19(95.0%) | 45(84.9%) | 143(92.3%) | 0.053 | |

| Yes | 3(7.3%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(5.0%) | 8(15.1%) | 12(7.7%) | ||

| CA-125 at diagnosis | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 130.4(±24.0) | 95.5(±184.3) | 59.1(±67.6) | 154.0(±307.2) | 120.0(±220.1) | 0.338 | |

| Histology | |||||||

| Endometrioid | 37(90.2%) | 34(82.9%) | 15(75.0%) | 27(50.9%) | 113(72.9%) | 0.002 | |

| Serous | 0(0.0%) | 2(4.9%) | 1(5.0%) | 10(18.9%) | 13(8.4%) | ||

| Clear cell | 2(4.9%) | 1(2.4%) | 1(5.0%) | 4(7.5%) | 8(5.2%) | ||

| MMMT | 1(2.4%) | 2(4.9%) | 1(5.0%) | 11(20.8%) | 15(9.7%) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 0(0.0%) | 2(4.9%) | 2(10.0%) | 1(1.9%) | 5(3.2%) | ||

| Neuroendocrine | 1(2.4%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.6%) | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||||

| III | 28(68.3%) | 27(65.9%) | 12(60.0%) | 28(52.8%) | 95(61.3%) | 0.457 | |

| IV | 7(17.1%) | 4(9.8%) | 5(25.0%) | 13(24.5%) | 29(18.7%) | ||

| Recur | 6(14.6%) | 10(24.4%) | 3(15.0%) | 12(22.6%) | 31(20.0%) | ||

| Staging op pathological grade | |||||||

| 1 | 7(17.1%) | 12(29.3%) | 3(15.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 22(14.2%) | <0.001 | |

| 2 | 24(58.5%) | 19(46.3%) | 6(30.0%) | 14(26.4%) | 63(40.6%) | ||

| 3 | 9(22.0%) | 9(22.0%) | 10(50.0%) | 39(73.6%) | 67(43.2%) | ||

| none | 1(2.4%) | 1(2.4%) | 1(5.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 3(1.9%) | ||

| Staging op LVSI | |||||||

| No | 15(36.6%) | 22(53.7%) | 7(35.0%) | 19(35.8%) | 63(40.6%) | 0.055 | |

| Yes | 25(61.0%) | 19(46.3%) | 11(55.0%) | 34(64.2%) | 89(57.4%) | ||

| Missing | 1(2.4%) | 0(0.0%) | 2(10.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 3(1.9%) | ||

| Radiotherapy | |||||||

| No | 16(39.0%) | 27(65.9%) | 11(55.0%) | 34(64.2%) | 88(56.8%) | 0.049 | |

| Yes | 25(61.0%) | 14(34.1%) | 9(45.0%) | 19(35.8%) | 67(43.2%) | ||

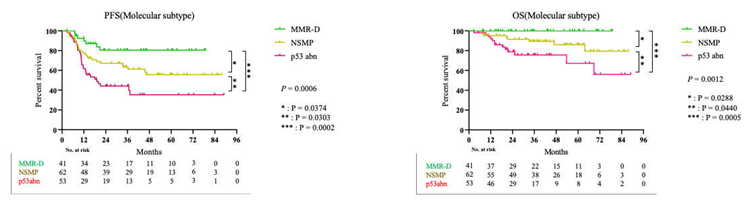

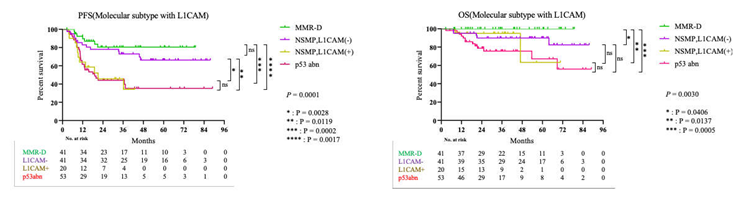

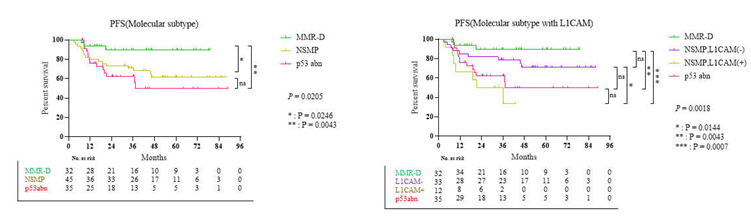

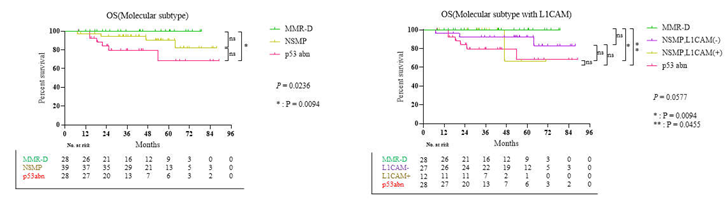

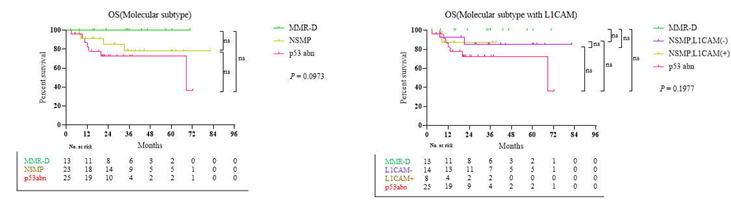

3.3. Survival Result and Multivariable Analysis by Molecular Classification in Advanced Stage and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.J.; Won, Y.-J.; Lee, J.J.; Jung, K.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Kong, H.-J.; Im, J.-S.; Seo, H.G. Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2019. Cancer Res Treat 2022, 54, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B. Associations between obesity, metabolic syndrome, and endometrial cancer risk in East Asian women. J Gynecol Oncol 2022, 33, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N.; Kandoth, C.; Schultz, N.; Cherniack, A.D.; Akbani, R.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Robertson, A.G.; Pashtan, I.; Shen, R.; et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature 2013, 497, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhouk, A.; McConechy, M.K.; Leung, S.; Yang, W.; Lum, A.; Senz, J.; Boyd, N.; Pike, J.; Anglesio, M.; Kwon, J.S.; et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: A simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommoss, F.K.; Karnezis, A.N.; Kommoss, F.; Talhouk, A.; Taran, F.A.; Staebler, A.; Gilks, C.B.; Huntsman, D.G.; Krämer, B.; Brucker, S.Y.; et al. L1CAM further stratifies endometrial carcinoma patients with no specific molecular risk profile. Br J Cancer 2018, 119, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeimet, A.G.; Reimer, D.; Huszar, M.; Winterhoff, B.; Puistola, U.; Azim, S.A.; Müller-Holzner, E.; Ben-Arie, A.; van Kempen, L.C.; Petru, E.; et al. L1CAM in early-stage type I endometrial cancer: results of a large multicenter evaluation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013, 105, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, M.R.; Chase, D.M.; Slomovitz, B.M.; dePont Christensen, R.; Novák, Z.; Black, D.; Gilbert, L.; Sharma, S.; Valabrega, G.; Landrum, L.M.; et al. Dostarlimab for Primary Advanced or Recurrent Endometrial Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, R.N.; Sill, M.W.; Beffa, L.; Moore, R.G.; Hope, J.M.; Musa, F.B.; Mannel, R.; Shahin, M.S.; Cantuaria, G.H.; Girda, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Advanced Endometrial Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, S.M.; Powell, M.E.; Mileshkin, L.; Katsaros, D.; Bessette, P.; Haie-Meder, C.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Ledermann, J.A.; Khaw, P.; D'Amico, R.; et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in women with high-risk endometrial cancer (PORTEC-3): patterns of recurrence and post-hoc survival analysis of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Pina, A.; Albert, A.; McAlpine, J.; Wolber, R.; Blake Gilks, C.; Kwon, J.S. Does MMR status in endometrial cancer influence response to adjuvant therapy? Gynecol Oncol 2018, 151, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMeekin, D.S.; Tritchler, D.L.; Cohn, D.E.; Mutch, D.G.; Lankes, H.A.; Geller, M.A.; Powell, M.A.; Backes, F.J.; Landrum, L.M.; Zaino, R.; et al. Clinicopathologic Significance of Mismatch Repair Defects in Endometrial Cancer: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 3062–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Angelico, G.; Travaglino, A.; Inzani, F.; Arciuolo, D.; Valente, M.; D'Alessandris, N.; Scaglione, G.; Fiorentino, V.; Raffone, A.; et al. New Pathological and Clinical Insights in Endometrial Cancer in View of the Updated ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, M.; Hasenburg, A.; Battista, M.J. The TCGA Molecular Classification of Endometrial Cancer and Its Possible Impact on Adjuvant Treatment Decisions. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Heerik, A.; Horeweg, N.; Nout, R.A.; Lutgens, L.; van der Steen-Banasik, E.M.; Westerveld, G.H.; van den Berg, H.A.; Slot, A.; Koppe, F.L.A.; Kommoss, S.; et al. PORTEC-4a: international randomized trial of molecular profile-based adjuvant treatment for women with high-intermediate risk endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020, 30, 2002–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarnthai, N.; Hall, K.; Yeh, I.T. Molecular profiling of endometrial malignancies. Obstet Gynecol Int 2010, 2010, 162363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbel, M.; Ronnett, B.M.; Singh, N.; Soslow, R.A.; Gilks, C.B.; McCluggage, W.G. Interpretation of P53 Immunohistochemistry in Endometrial Carcinomas: Toward Increased Reproducibility. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2019, 38 Suppl 1, S123–s131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardi, L.D.; Reczek, E.E.; Cosmas, C.; Demicco, E.G.; McCurrach, M.E.; Lowe, S.W.; Jacks, T. PERP, an apoptosis-associated target of p53, is a novel member of the PMP-22/gas3 family. Genes Dev 2000, 14, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, J.; Takenaka, M.; Okamoto, A. Molecular typing guiding treatment and prognosis of endometrial cancer. Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinical Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.S.; Woo, H.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, E.; Nam, E.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.T. Mismatch repair status influences response to fertility-sparing treatment of endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021, 224, 370–e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Kim, Y.N.; Lee, K.; Park, E.; Lee, Y.J.; Hwang, S.Y.; Park, J.; Choi, Z.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.; et al. Feasibility and clinical applicability of genomic profiling based on cervical smear samples in patients with endometrial cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 942735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Lee, S.K.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, K.; No, J.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, H. Clinical evaluation of a droplet digital PCR assay for detecting POLE mutations and molecular classification of endometrial cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 2022, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaah, A.S.; Salim, M.M.; Al-Haddad, H.S.; McAllister, K.A.; Yasseen, A.A. The frequency of POLE-mutation in endometrial carcinoma and prognostic implications: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Pathol Transl Med 2020, 54, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PFS, 61 of 154 Events | OS, 20 of 152 Events | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable [Ref] | HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.036(1.009-1.064) | 0.010 | |||

| Stage [III] | 0.009 | ||||

| IV | 2.137(1.098-4.160) | ||||

| Recur | 2.335(1.240-4.398) | ||||

| CA-125 | 1.001(1.000-1.002) | 0.061 | |||

| BMI | 0.866(0.768-0.976) | 0.018 | |||

| Radiotherapy[No] | 0.074 | ||||

| Yes | 0.367(0.122-1.101) | ||||

| Molecular classification [NSMP] | 0.039 | 0.172 | |||

| MMR-D | 0.579(0.258-1.300) | 0.000(0.000-5.407E173) | |||

| p53abn | 1.599(0.911-2.806) | 2.430(0.960-6.151) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).