1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage (III and IV), with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 25% [

1]. The standard treatment for advanced ovarian cancer (AOC) involves primary surgical cytoreduction followed by platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy [

2]. An alternative approach is neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by interval surgical cytoreduction, particularly in cases where complete cytoreduction is not feasible due to an extensive cancer burden [

3]. Numerous studies have assessed these two strategies, comparing their efficacy, safety profiles, and survival outcomes [

4,

5]. The non-inferiority trials of primary surgical cytoreduction versus NACT showed that tumor debulking to R0 was the most important indicator of overall survival (OS), and rates were higher in the NACT- interval surgical cytoreduction treatment arms [

6,

7,

8].

Therefore, the use of predictive models to assess surgical outcomes and prognosis is essential for optimizing patient selection and identifying those who are most likely to benefit from extensive surgical interventions. Among the potential prognostic factors being explored are the Cancer Antigen-125 (CA-125) ELIMination rate constant K (KELIM) and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).

The CA-125 KELIM (a kinetic parameter derived from CA-125 measurements within the initial 100 days of systemic chemotherapy) has been identified as a predictor of tumor intrinsic chemosensitivity [

9]. KELIM represents the rate of CA-125 decline during chemotherapy, with higher KELIM values indicating greater chemosensitivity. It has been identified as a biomarker for survival outcomes, including progression-free survival (PFS) and OS [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, KELIM has been associated with the likelihood of complete resection at interval debulking surgery and the risk of subsequent platinum-resistant relapse [

13,

14].

Inflammation has been identified as a critical factor in the initiation and progression of various solid tumors [

15,

16]. A range of inflammatory serum markers has been studied to evaluate their association with clinical outcomes and prognosis across different cancer types [

17]. Among these, NLR has emerged as a potential marker for survival outcomes in ovarian cancer and other solid malignancies [

18,

19]. It is calculated as neutrophil count divided by lymphocyte count and can be easily derived from a Complete Blood Count (CBC). Elevated NLR values at the time of diagnosis are associated with poorer PFS and OS [

20,

21], greater disease severity and resistance to platinum-based therapy [

22,

23].

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the prognostic value of the KELIM score and the NLR values in predicting survival outcomes, including OS and PFS in women with high-grade serous AOC receiving NACT.

Our findings indicate that the KELIM score serves as a strong prognostic marker for both PFS and OS, while NLR demonstrates a week association. Notably, the assessment of these two markers enhances prognostic accuracy, suggesting their potential complementary role in clinical practice. To our knowledge, no prior study has directly compared these prognostic factors in this specific context, underscoring the novelty and clinical significance of our findings.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective, single-center cohort study was conducted at a tertiary institution, to examine patients with stage III or IV ovarian or fallopian tube cancer who received platinum-based NACT followed by IDS over an 11-year period (January 2013–December 2023). All surgeries were performed by two specialized gynecologic oncologists, adhering to the guidelines of the European Society of Gynecological Oncology (ESGO) and prioritizing maximal efforts to achieve no residual disease. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the hospital’s health ethics committee.

The inclusion criteria specified patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer of high-grade serous histology who had received 3 to 4 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, had recurrent ovarian cancer, incomplete registry data, or lack of follow-up attendance were excluded from the study.

During the study period, 324 patients were identified. Of these, 196 were excluded because they had undergone primary debulking surgery or presented with recurrent ovarian cancer. An additional 50 patients were excluded due to missing essential registry data or discontinuation of follow-up. Ultimately, 78 patients with high-grade serous advanced ovarian cancer met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis.

All data were collected within one month from the hospital’s computerized patient records system. Patients' demographic and clinical characteristics included age, Body Mass Index (BMI), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [

24], serial CA-125 values during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, KELIM score, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, Clavien-Dindo classification for postoperative complications [

25], length of hospital stay, residual disease status after debulking surgery based on the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) score, date of diagnosis, date of recurrence or disease progression, and date of last follow-up or death.

KELIM score was calculated in the neoadjuvant setting using an available online tool [

26]. It was evaluated both as a continuous variable and as a binary index, with a cut-off of ≥1 indicating a favorable outcome. The dates of each chemotherapy cycle, along with the corresponding CA-125 values recorded within the first 100 days from the initiation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were input for analysis. Preferably, CA-125 values obtained before the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th chemotherapy cycles were used for the calculation. However, when these values were unavailable, the CA-125 measurement taken prior to the first chemotherapy cycle (within 7 days of starting neoadjuvant chemotherapy) was used. This adjustment was necessary for only seven patients.

NLR was determined using CBC data obtained from all patients before the initiation of chemotherapy. NLR was calculated by dividing the absolute neutrophil count by the absolute lymphocyte count. Consistent with prior research, an NLR greater than 3 was considered elevated and associated with unfavorable outcomes [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Standard descriptive statistics were performed for both quantitative (mean and standard deviation) and qualitative variables (frequency and percentage). Kaplan-Meier curves were developed for PFS and OS according to KELIM score and NLR values. The Log Rank test was used to compare the corresponding survival distributions. For KELIM score, the threshold of 1 was applied, and it was assessed as a binary variable (0: <1, 1: ≥1). For NLR, the threshold of 3 was used, and it was similarly assessed as a binary variable (0: <3, 1: ≥3). Univariable Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the risk of recurrence (PFS) and OS according to KELIM score and NLR values. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 for all analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS V22 and R V4.2.2..

3. Results

A total of 78 patients with high-grade serous advanced ovarian cancer were included. The mean age at diagnosis was 61.45 ± 12.32 years, and the mean BMI was 28 ± 5.92 kg/m² (

Table 1). The performance status of the patients, assessed using the CCI, revealed that 38 out of 78 patients (48.7%) had a CCI score of ≥ 3, indicating that nearly half of the cohort had mild to moderate comorbidities (

Table 1). Among the included patients, 63 were diagnosed with stage III disease, and 15 had stage IV disease. Regarding treatment, 70 patients received 3 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy, while 8 received 4 cycles.

Residual disease was assessed using the PCI, calculated both at the start and end of cytoreductive surgery. Fifty-eight patients (70%) achieved complete cytoreduction with no residual disease, 14 patients had residual disease measuring <1 cm, and 6 patients underwent suboptimal debulking surgery with residual disease ≥1 cm.

Postoperative complications were evaluated using the Clavien–Dindo classification system, with a median score of 22.6 and an interquartile range (IQR) of 12.2–32. Fourteen patients required ICU admission, and the median hospital stay was 8 days, with an IQR of 6.5–9 days (

Table 1).

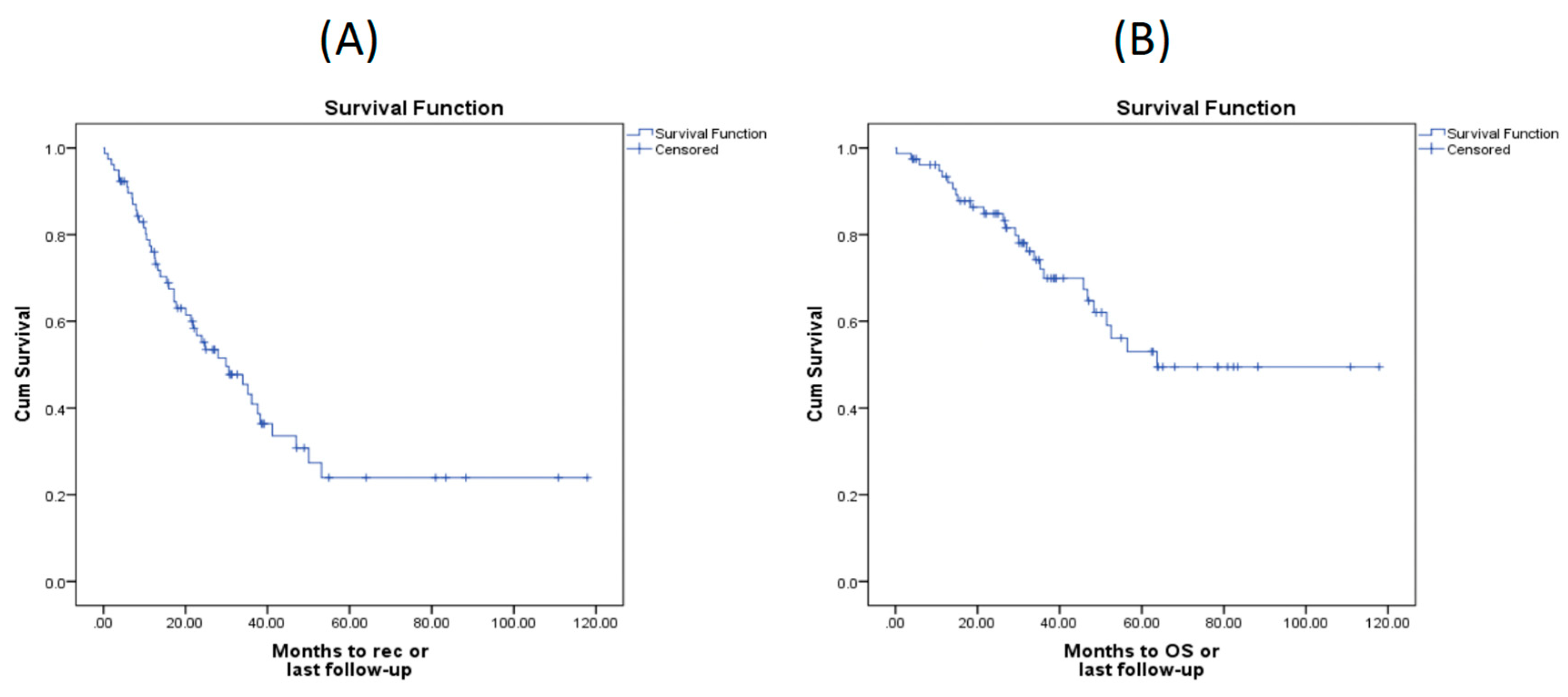

The median PFS and OS times were found to be 29.86 and 63.74 months, respectively, in the whole cohort (

Table 1). The corresponding Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in

Figure 1.

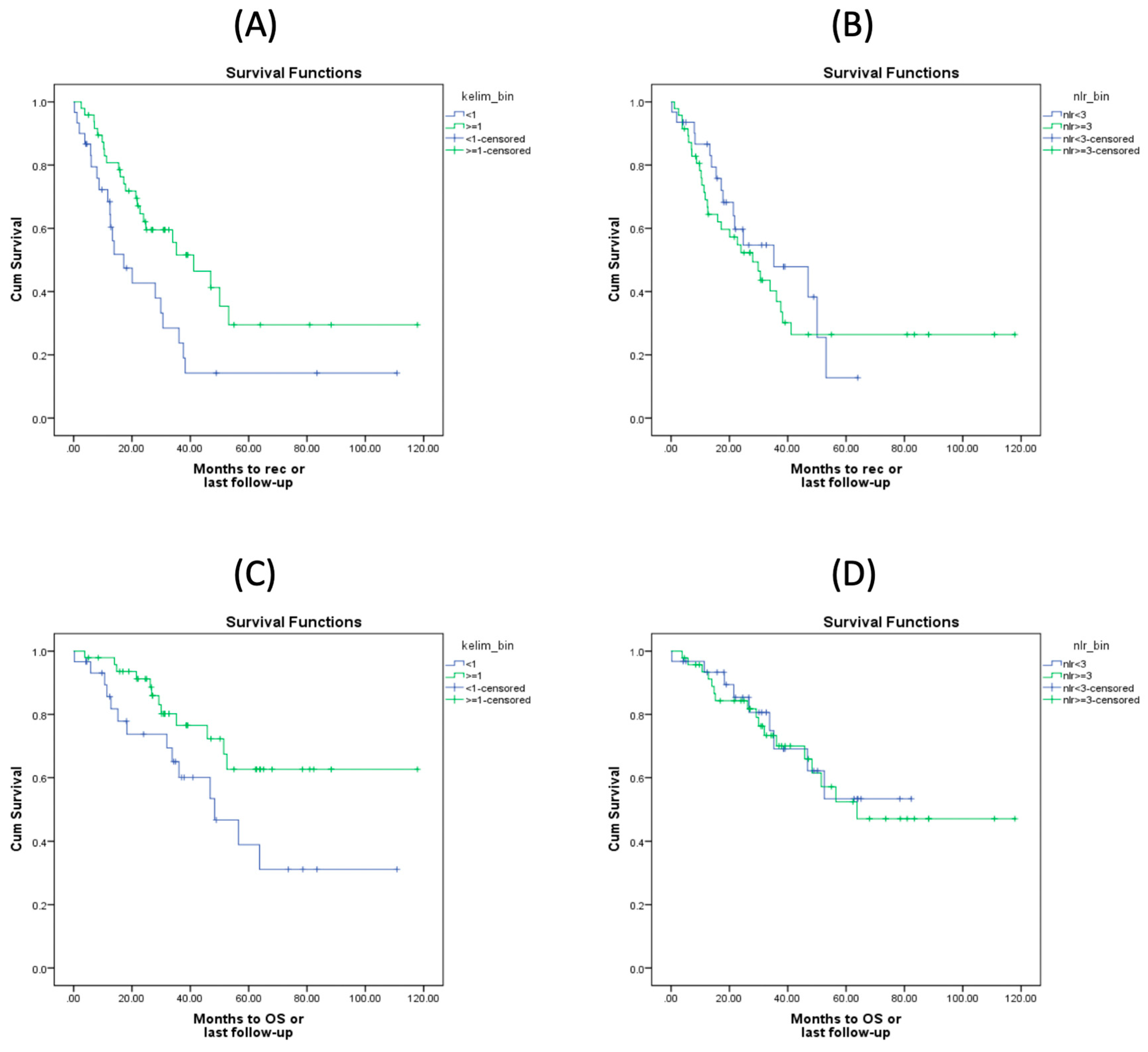

Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS according to KELIM score and NLR values are shown in

Figure 2. Specifically, patients with a favorable KELIM score (

1) exhibited statistically significantly better PFS compared to those with an unfavorable score (<1) (

Figure 1A), with median survival times of 41.13 months and 17.18 months, respectively (Log Rank test p-value=0.012). In contrast, no statistically significant difference in PFS was observed based on NLR values, with patients with NLR

3 exhibiting worse PFS compared to those with NLR <3 (

Figure 1B), with median survival times of 27.99 months and 35.22 months, respectively (Log Rank test p-value=0.527). When assessing OS, patients with a favorable KELIM score had statistically significantly better outcomes compared to those with an unfavorable score (

Figure 1C), with median OS times of not-yet-reached and 48.30 months, respectively (Log Rank test p-value=0.039). However, no statistically significant difference in OS was observed between patients with NLR

3 and those with NLR <3 (

Figure 1D), with median OS times of 63.74 months and not-yet-reached, respectively (Log Rank test p-value=0.764).

In addition, univariable Cox regression analysis was performed for KELIM score and NLR values regarding PFS and OS, and the results are displayed in

Table 2. The analysis showed that the estimated hazard ratio (HR) was statistically significantly lower for patients with a KELIM score ≥1 compared to those with a KELIM score <1 (reference category) in both recurrence and OS. Specifically, the HR values were 0.480 (95% CI: 0.266-0.864, p=0.015) for recurrence and 0.453 (95% CI: 0.209-0.981, p=0.045) for OS (

Table 2). In other words, patients with a favorable KELIM score had less than half the hazard for both recurrence and death compared to those with an unfavorable KELIM score.

On the other hand, patients with an NLR ≥ 3 did not show a statistically significant difference in HR for recurrence or overall survival compared to those with an NLR <3 (reference category). More specifically, the estimated HR was 1.218 (95% CI: 0.660-2.245, p=0.528) for recurrence, and 1.132 (95% CI: 0.504-2.541, p=0.764) for overall survival. Although, the HR was greater than 1 in both cases, indicating a potential tendency toward a higher risk for both recurrence and death for patients with an NLR ≥ 3, this result was not supported by statistical significance.

Consequently, the prognostic value of the KELIM score was much more evident than that of the NLR, when considering both PFS and OS as endpoints.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prognostic value of KELIM score and NLR in survival outcomes for AOC undergoing NACT. Results showed that a KELIM score ≥1 was statistically significantly associated with improved PFS and OS in these patients compared to those with a KELIM score <1. In addition, patients with a favorable KELIM score (≥1) had a reduced risk of both recurrence and death compared to those with an unfavorable score (<1). In contrast, no statistically significant difference was observed in PFS and OS among the patients based on NLR values. Although no statistically significant association was found between NLR values and the risk of recurrence or death, patients with NLR ≥3 exhibited a greater likelihood of recurrence and death compared to those with NLR <3, though this difference was not statistically significant.

The KELIM score has been widely used in several studies as a prognostic marker in ovarian cancer, serving as a predictor of chemosensitivity after primary debulking [

12,

33] or as a predictor of complete cytoreduction in the setting of IDS after NACT [

34]. In addition, its prognostic value is further supported by its impact on survival outcomes. In the present study, the association between PFS, OS and KELIM score was analyzed, revealing a statistically significant improvement in both PFS and OS among patients with a favorable KELIM score compared to those with an unfavorable score. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that a higher KELIM score (≥1) is associated with improved PFS and OS in patients undergoing IDS after NACT [

12,

35,

36]. Additionally, a meta-analysis has validated the KELIM score as a strong predictor of patient survival, regardless of surgical completeness [

11].

Increasing evidence suggests that systematic inflammation and immune cells play a crucial role in cancer progression and can serve as prognostic indicators for malignancies [

17]. Several components of a CBC, such as the NLR, have been explored in predicting cancer outcomes. Neutrophilia has been associated with pro-tumoral effects, like invasion, proliferation and metastasis. In contrast, lymphocytes play a crucial role in tumor defense and inhibition of tumor proliferation and migration [

37].

Kim et al. [

30] were the first to assess the prognostic value of pre-treatment NLR in patients with AOC undergoing NACT. Their study found that an elevated NLR (>3.81) was associated with poor overall survival, but not PFS. However, they found an association between the dynamic change of the NLR during NACT and PFS. Several studies have confirmed these findings [

32,

38], although different NLR cut-off values were used in each study. In contrary, a meta-analysis with 2892 patients showed that a high pre-treatment NLR was statistically significantly associated with shorter PFS and OS [

39].

However, the present study, which included patients that underwent IDS after receiving 3 or 4 cycles of NACT, failed to demonstrate a statistically significant association between NLR and survival outcomes. OS and PFS in these patients were explored based on NLR values, using a cut-off value of 3, as established in previous studies [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This finding suggests that NLR might not serve as a reliable predictor for survival outcomes in this specific patient cohort, or that the study's sample size and design limitations might have affected the statistical power to detect an effect. The strength of this study is that it included patients with AOC who underwent debulking surgery at a certified gynecological oncology center, accredited for advanced ovarian cancer surgery. The surgeries were performed by two proficient gynecological oncology surgeons. Furthermore, the chemotherapy treatments were administered at a certified medical oncology center, under the supervision of a professor of medical oncology, in accordance with the latest clinical guidelines. Patient follow-up was conducted as part of routine monitoring within the same hospital complex by the treating physicians. In addition, both the measurement of CA-125 levels for calculating the KELIM score and the analysis of CBC for NLR calculation, were conducted in the hospital's central laboratory, ensuring consistency in these measurements. However, certain limitations of our study should be considered. The retrospective design may introduce selection bias and confounding factors. Larger, multicenter studies would be essential to confirm the difference in their effectiveness as prognostic markers

5. Conclusions

KELIM score could be used as a predictive tool for survival outcomes in patients with AOC undergoing NACT. In our cohort, KELIM demonstrated better prognostic value than NLR. However, elevated NLR was not predictive of survival outcomes, in contrast to findings from previous studies. Given these discrepancies, further large-scale studies are essential to validate these findings and define the prognostic role of NLR in patients with AOC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.T., D.T. and E.T.; methodology, V.T., D.T.; software, V.T. T.M..; validation, V.T., K.K, K.C., P.T. and T.M.; formal analysis, V.T., T.M.; investigation, V.T., D.Z., I.T..; resources, V.T., I.T, C.A.; data curation, V.T, K.K..; writing—original draft preparation, V.T., K.K., T.M, D.T. E.T.; writing—review and editing, V.T., K.K., D.T., E.T., M.T.; T.M.; visualization, V.T.; supervision, G.G.; project administration, V.T.; funding acquisition, V.T; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As a retrospective review of anonymized patient data, this study has received formal ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of General Hospital of Thessaloniki "Papageorgiou" Greece.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study during their hospitalization for anonymous use of their data for scientific research

Data Availability Statement

We confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request. However, due to privacy concerns and in accordance with ethical standards and regulations, the data will be provided in a deidentified format to ensure patient anonymity. Requests for data should be directed to the corresponding author via email at theodoulidisvasilis@yahoo.gr.".

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Laboratory Department of "Papageorgiou" general hospital of Thessaloniki, for their valuable cooperation and technical assistance throughout this study. Additionally, we acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by our hospital, particularly for their invaluable assistance in data retrieval and management, which significantly contributed to the completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOC |

Advanced Ovarian Cancer |

| OS |

Overall Survival |

| PDS |

Primary Debulking Surgery |

| NACT |

NeoAdjuvant ChemoTherapy |

| IDS |

Interval Debulking Surgery |

| PFS |

Progression-Free Survival |

| NLR |

Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| KELIM |

ELIMination rate constant K |

| CBC |

Complete Blood Counts |

| ESGO |

European Society of Gynecological Oncology |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| PCI |

Peritoneal Cancer Index |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| IQR |

InterQuartile Range |

| CA-125 |

Cancer Antigen-125 |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016, 66, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, 16061, Published 2016 Aug 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.A.; Bohlke, K.; Armstrong, D.K.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer: Society of Gynecologic Oncology and American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. Gynecol Oncol. 2016, 143, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergote, I.; Tropé, C.G.; Amant, F.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, S.; Hook, J.; Nankivell, M.; et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015, 386, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, S.; Hook, J.; Nankivell, M.; Jayson, G.C.; Kitchener, H.; Lopes, T.; et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergote, I.; Tropé, C.G.; Amant, F.; Kristensen, G.B.; Ehlen, T.; Johnson, N.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2010, 363, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Y.A.; Reyes, H.D.; McDonald, M.E.; Newtson, A.; Devor, E.; Bender, D.P.; et al. Interval debulking surgery is not worth the wait: a National Cancer Database study comparing primary cytoreductive surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2020, 30, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, B.; Colomban, O.; Heywood, M.; et al. The strong prognostic value of KELIM, a model-based parameter from CA 125 kinetics in ovarian cancer: data from CALYPSO trial (a GINECO-GCIG study). Gynecol Oncol. 2013, 130, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Cho, H.W.; Park, E.Y.; et al. Prognostic value of CA125 kinetics, half-life, and nadir in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023, 33, 1913–1920, Published 2023 Dec 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbaux, P.; You, B.; Glasspool, R.M.; et al. Survival and modelled cancer antigen-125 ELIMination rate constant K score in ovarian cancer patients in first-line before poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor era: A Gynaecologic Cancer Intergroup meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2023, 191, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomban, O.; Tod, M.; Leary, A.; et al. Early Modeled Longitudinal CA-125 Kinetics and Survival of Ovarian Cancer Patients: A GINECO AGO MRC CTU Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5342–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.; Robelin, P.; Tod, M.; et al. CA-125 ELIMination Rate Constant K (KELIM) Is a Marker of Chemosensitivity in Patients with Ovarian Cancer: Results from the Phase II CHIVA Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4625–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouzoulas, D.; Tsolakidis, D.; Tzitzis, P.; et al. The Use of CA-125 KELIM to Identify Which Patients Can Achieve Complete Cytoreduction after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in High-Grade Serous Advanced Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? . Lancet. 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuntinarawat, P.; Tangmanomana, R.; Kittisiam, T. Association between alteration of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, cancer antigen-125 and surgical outcomes in advanced stage ovarian cancer patient who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2024, 52, 101347, Published 2024 Feb 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, M.G.; Templeton, A.J.; Maganti, M.; et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in biliary tract cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014, 50, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.R.; Park, J.C.; Park, C.H.; et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker to predict chemotherapeutic response and survival outcomes in metastatic advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2014, 17, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.A.; Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Terry, K.L.; et al. Prognostic significance and predictors of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014, 132, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Hur, H.W.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer and predicts survival after treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009, 58, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethier, J.L.; Desautels, D.N.; Templeton, A.J.; Oza, A.; Amir, E.; Lheureux, S. Is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio prognostic of survival outcomes in gynecologic cancers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017, 145, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Yan, Q.; Li, S.; Li, B.; Feng, Y. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio are predictive of chemotherapeutic response and prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Cancer Biomark. 2016, 17, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavien, P.A.; Barkun, J.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Vauthey, J.N.; Dindo, D.; Schulick, R.D.; de Santibañes, E.; Pekolj, J.; Slankamenac, K.; Bassi, C.; et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann. Surg. 2009, 250, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modeled CA-125 KELIM™ in Patients with Stage III–IV High Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinomas Treated in First-Line Setting with Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Available online: https://www.biomarker-kinetics.org/CA-125-neo (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Ethier, J.L.; Desautels, D.N.; Templeton, A.J.; Oza, A.; Amir, E.; Lheureux, S. Is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio prognostic of survival outcomes in gynecologic cancers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2017, 145, 584–594. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ma, J.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y. The combination of plasma fibrinogen concentration and neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (F-NLR) as a prognostic factor of epithelial ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 7283–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farolf, A.; Scarpi, E.; Greco, F.; et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictive factors for platinum sensitivity and as prognostic factors in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer patients: a MITO24 retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Lee, I.; Chung, Y.S.; Nam, E.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and its dynamic change during neoadjuvant chemotherapy as poor prognostic factors in advanced ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018, 61, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.A.; Labidi-Galy, S.I.; Terry, K.L.; Vitonis, A.F.; Welch, W.R.; Goodman, A.; et al. Prognostic significance and predictors of the neutrophil-to lymphocyte ratio in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014, 132, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liontos, M.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Koutsoukos, K.; Markellos, C.; Skafida, E.; Fiste, O.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and chemotherapy response score as prognostic markers in ovarian cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Journal of Ovarian Research 2021, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You B, Sehgal V, Hosmane B, Huang X, Ansell PJ, Dinh MH, Bell-McGuinn K, Luo X, Fleming GF, Friedlander M, Bookman MA, Moore KN, Steffensen KD, Coleman RL, Swisher EM. CA-125 KELIM as a Potential Complementary Tool for Predicting Veliparib Benefit: An Exploratory Analysis From the VELIA/GOG-3005 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Jan 1;41, 107-116. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.00430. Epub 2022 Jul 22. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2023 Mar 10;41, 1633. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.02888. PMID: 35867965; PMCID: PMC9788978. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Kim ET, Kim SI, Park EY, Park MY, Park SY, Lim MC. Prognostic Role of CA-125 Elimination Rate Constant (KELIM) in Patients with Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Who Received PARP Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Jun 26;16, 2339. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bouvarel B, Colomban O, Frenel JS, Loaec C, Bourgin C, Berton D, Freyer G, You B, Classe JM. Clinical impact of CA-125 ELIMination rate constant K (KELIM) on surgical strategy in advanced serous ovarian cancer patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024 Apr 1;34, 574-580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wagensveld L, Colomban O, van der Aa MA, Freyer G, Sonke GS, Kruitwagen RFPM, You B. Confirmation of the utility of the CA-125 elimination rate (KELIM) as an indicator of the chemosensitivity in advanced-stage ovarian cancer in a "real-life setting". J Gynecol Oncol. 2024 May;35, e34. Epub 2024 Jan 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008 Jul 24;454, 436–444. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman L, Sabah G, Jakobson-Setton A, Raban O, Yeoshoua E, Eitan R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in advanced stage ovarian carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020 Jan;148, 102-106. Epub 2019 Oct 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Yan, G.; Cheng, S.; Fathy, A.H.; Yan, N.; Zhao, Y. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Potential Prognostic Biomarker in Patients with Ovarian Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2017, 2017, 7943467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).