Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

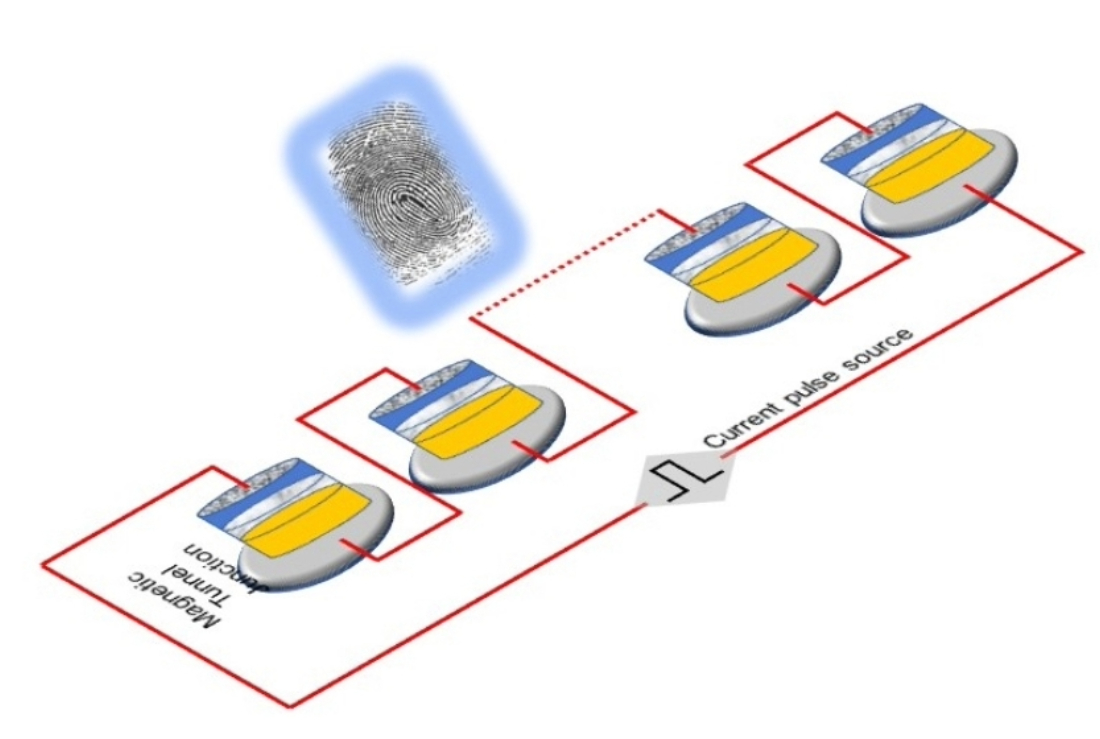

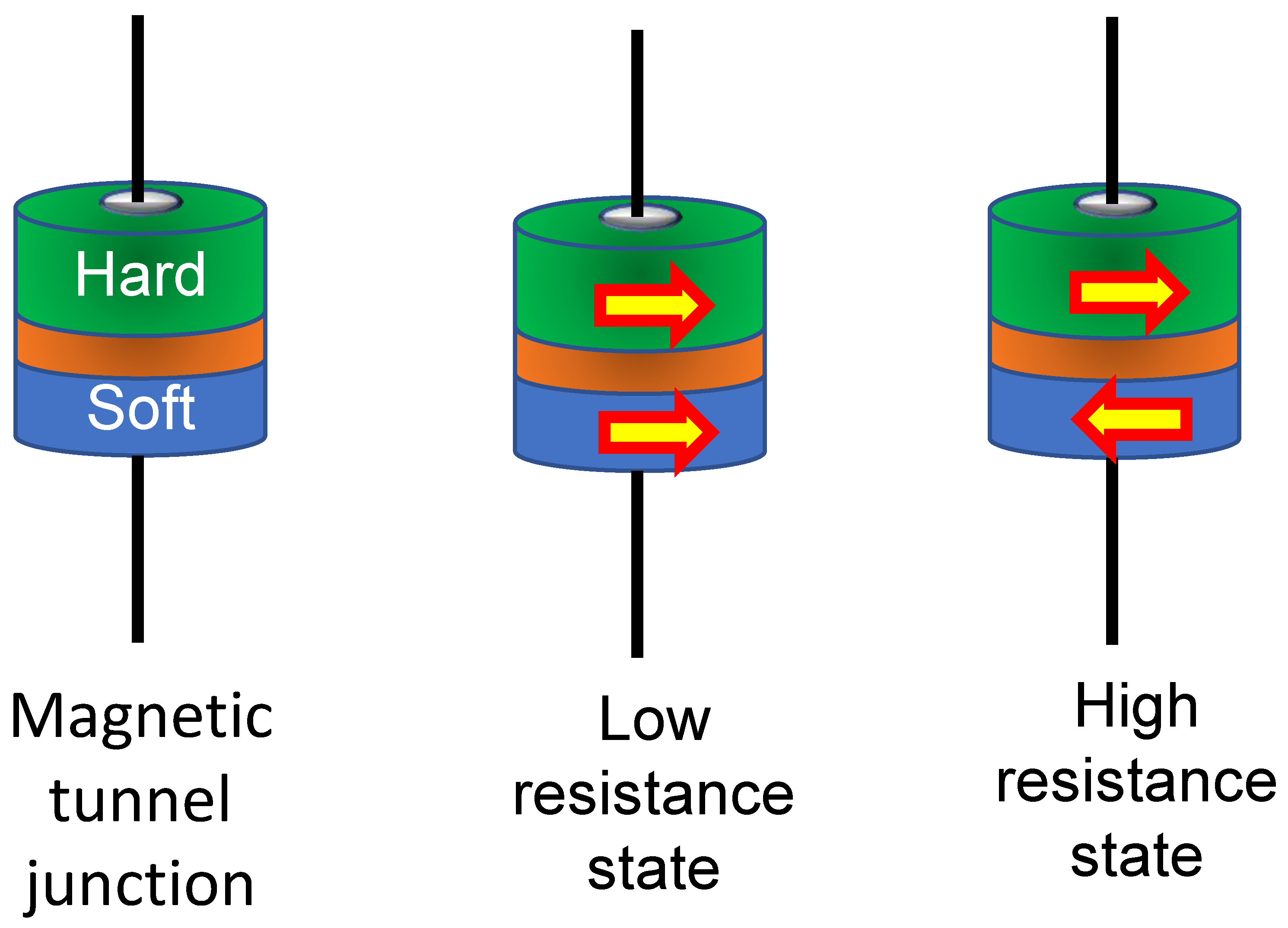

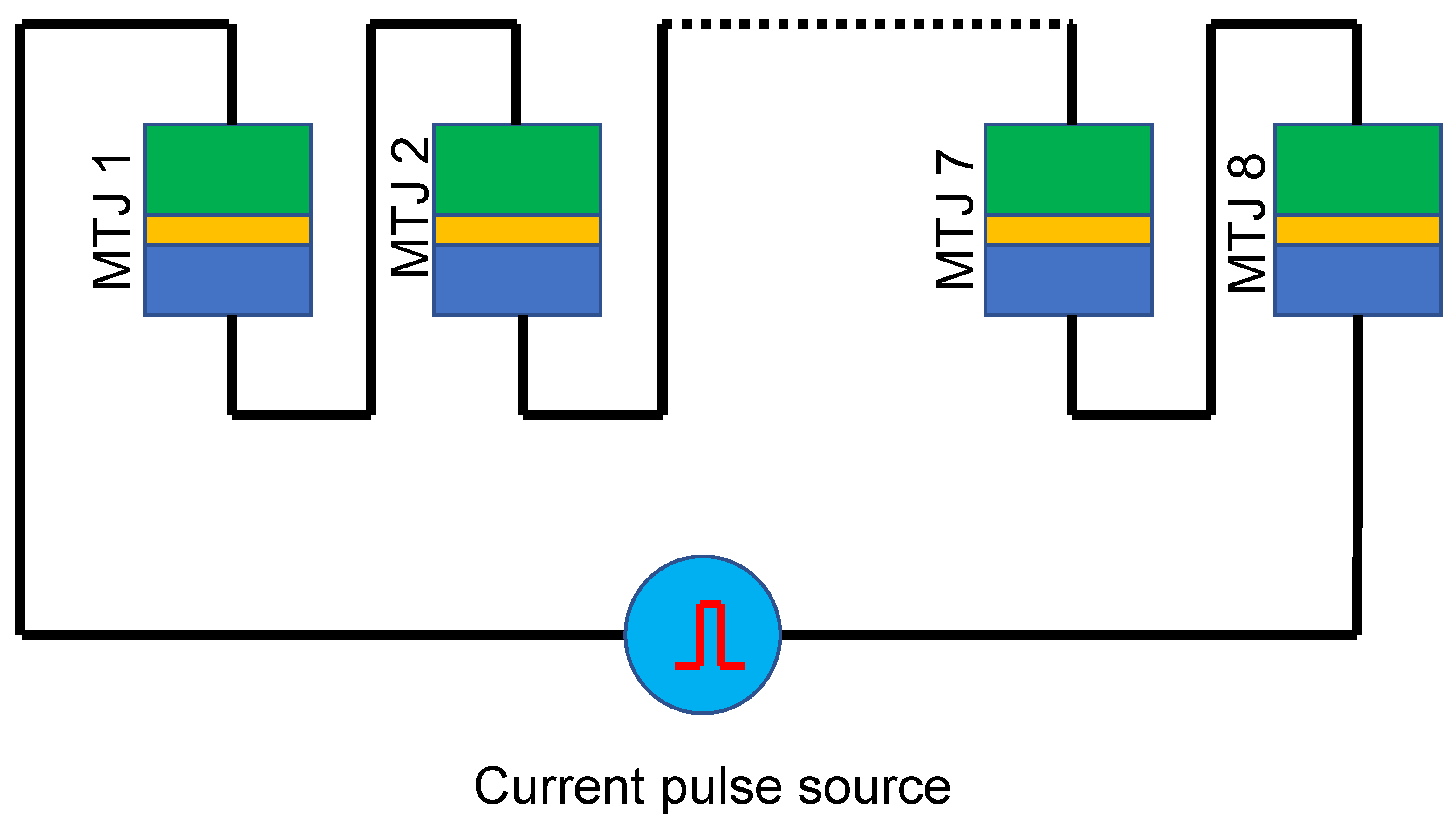

2. PUFs Based on Magnetic Tunnel Junctions

2.1. Threshold Current Based PUF

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

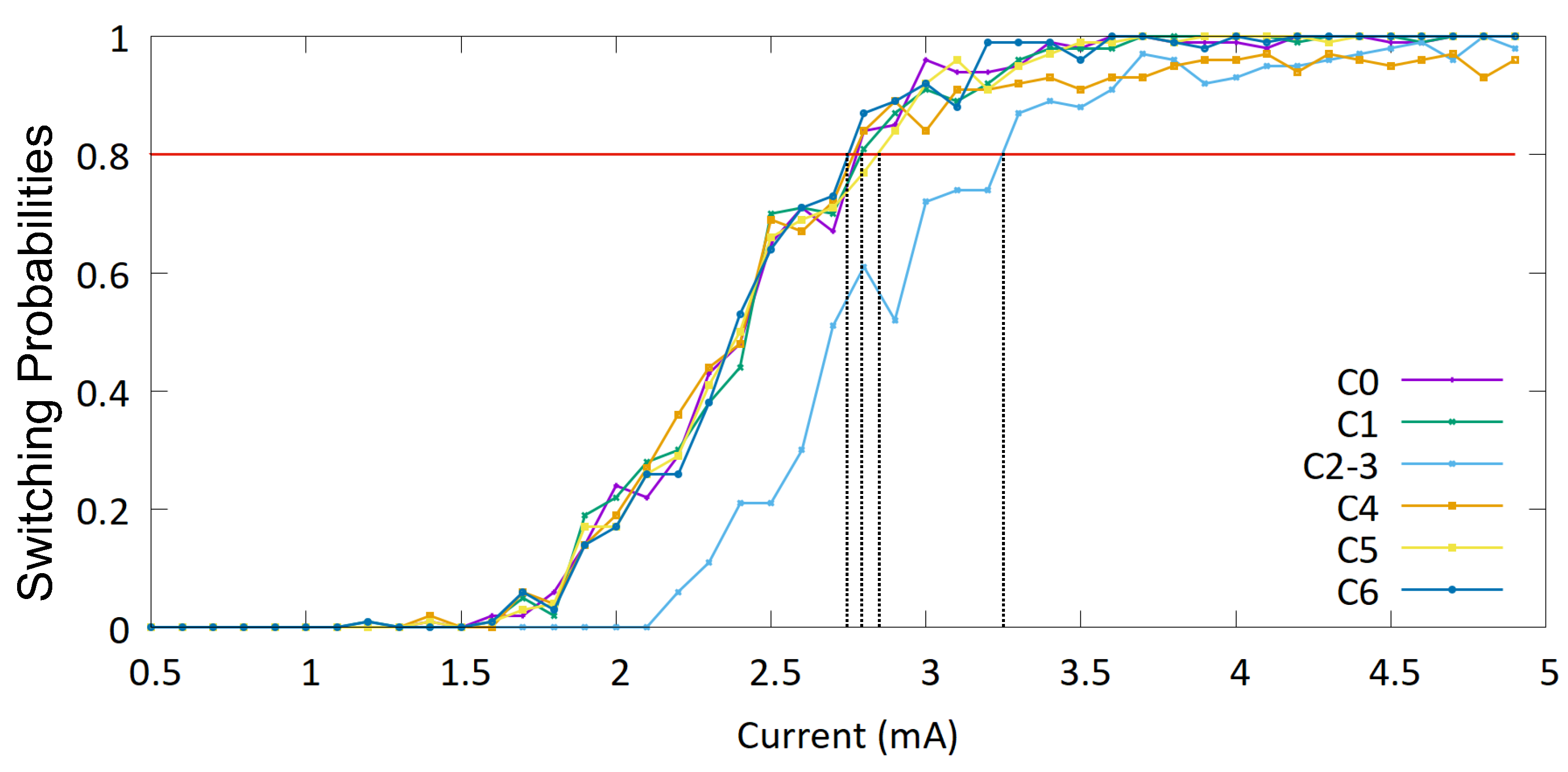

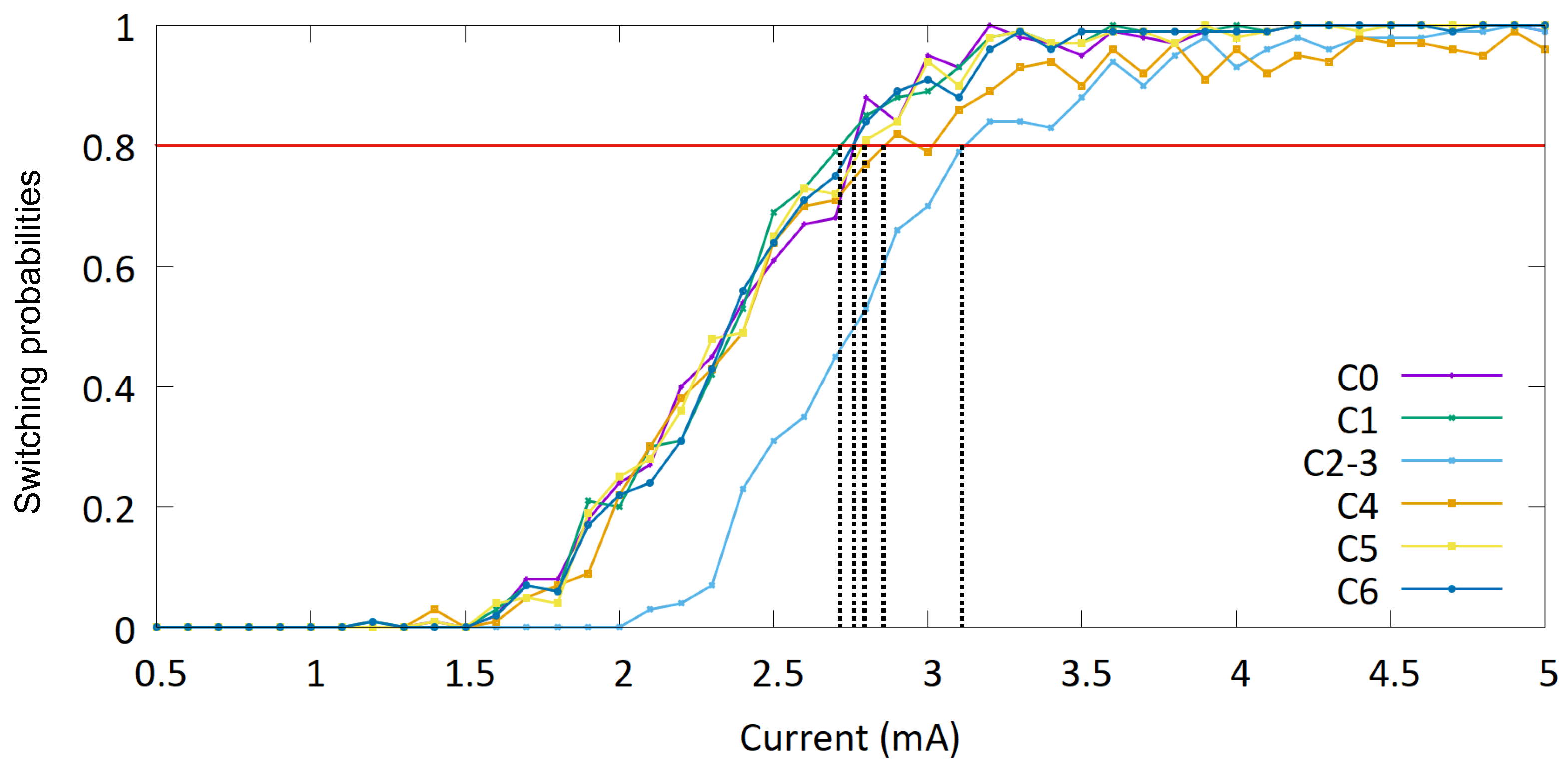

4.1. PUF Behavior

4.2. Inter-Hamming Distance

4.3. Sensitivity to Temperature and Intra-Hamming Distance

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Herder, C.; Yu, M-D.; Farinaz, K. and Devadas, S. Physical Unclonable Functions and Applications: A Tutorial. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 1126. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, M.; Guo, Z.; Li, R.; Zou, Q.; Luo, S.; Zhang, S.; Luo, Q.; Hong, J. and You, L. Highly Secure Physically Unclonable Cryptographic Primitives Based on Interfacial Magnetic Anisotropy. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 7211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z. et al. Reconfigurable Physical Unclonable Function Based on Spin-Orbit Torque Induced Chiral Domain Wall Motion. IEEE Elec. Dev. Lett. 2021, 42, 597. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sahay, S. and Suri, M. Switching-Time Dependent PUF Using STT-MRAM. 2018, 31th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2018 17th International Conference on Embedded Systems (IEEE).

- Das, J.; Kevin, S., Srinath, R.; Drew, B. and Bhanja, S. MRAM PUF: A novel geometry based magnetic PUF with integrated CMOS. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2015, 14, 436–443. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fong, X.; Chang, C. H.; Kong, Z. H. and Roy, K. Feasibility study of emerging non-volatile memory based physical unclonable functions. IEEE 6th International Memory Workshop, 2014, pp. 1-4.

- Marukame, M.; Tanamoto, T. and Mitani, Y. Extracting physically unclonable function from spin transfer switching characteristics in magnetic tunnel junctions. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Vatajelu, E.I.; Natale, G.D.; Barbareschi, M.; Torres, L.; Indaco, M. and Prinetto, P. STT-MRAM-based PUF architecture exploiting magnetic tunnel junction fabrication-induced variability. ACM Journal on Emerging Technologies in Computing Systems (JETC) 2016, 13, 5. [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. S.; McDonald, N.; Yan, L-K. and Wysocki, B. A write-time based memristive puf for hardware security applications. Proc. IEEE/ACM Int. Conf. Comput.-Aided Design, 2013, pp. 830–833.

- https://www.ugent.be/we/solidstatesciences/dynamat/en/mumax.

- Winters, D.; Abeed, M. A.; Sahoo, S.; Barman, A. and Bandyopadhyay, S. Reliability of magnetoelastic switching of nonideal nanomagnets with defects: A case study for the viability of straintronic logic and memory. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 034010. [CrossRef]

- Brown Jr. W. F. Thermal Fluctuations of a Single-Domain Particle. Phys. Rev. 1963, 130, 1677. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S. Magnetic Straintronics An Energy-Efficient Hardware Paradigm for Digital and Analog Information Processing, Synthesis Lectures on Engineering, Science and Technology, Springer Nature, New York, 2022.

| Defect | Threshold current (mA) | Threshold current density (A/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.75 | 3.89×1011 | |

| 2.78 | 3.93×1011 | |

| 3.26 | 4.61×1011 | |

| 2.78 | 3.93×1011 | |

| 2.82 | 3.98×1011 | |

| 2.78 | 3.93×1011 |

| Defect distribution | Response bit stream |

|---|---|

| Unit 1: | 110 |

| Unit 2: | 101 |

| Unit 3: | 110 |

| Unit 4: | 101 |

| Unit 5: | 011 |

| Unit 6: | 011 |

| Defect | Threshold current (mA) | Threshold current density (A/m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.75 | 3.89×1011 | |

| 2.72 | 3.84×1011 | |

| 3.12 | 4.41×1011 | |

| 2.82 | 3.99×1011 | |

| 2.80 | 3.95×1011 | |

| 2.75 | 3.88×1011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).