1. Introduction

The integration of biometric authentication into smart devices has become pervasive, providing an appealing alternative to traditional credential-based methods. Modern secure devices commonly employ facial recognition [

1,

2], iris scanning [

3,

4], or fingerprint analysis [

5] as primary authentication mechanisms, capitalizing on the inherent uniqueness and non-reproducibility of biometric traits. These identifiers, rooted in distinctive facial features or fingerprint patterns, not only reduce the risk of unauthorized access to sensitive data [

6,

7,

8] but also eliminate the cognitive overhead associated with passwords and PINs. As a result, biometric systems streamline user authentication, promote seamless access to digital resources, and drive wider adoption of secure smart devices across diverse sectors [

9].

Despite their advantages, the deployment of biometrics in authentication frameworks exposes several critical vulnerabilities. The centralized storage of biometric templates introduces a substantial risk: a successful breach may lead to irrevocable compromise of personal identifiers, as biometric information cannot be reset or revoked like conventional credentials [

10]. Furthermore, biometric modalities are increasingly targeted by sophisticated spoofing strategies—including the use of high-resolution images, 3D masks, or adversarial inputs—that seek to deceive recognition systems [

11]. The recent proliferation of AI-driven attacks, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) producing hyper-realistic deepfakes, and template inversion techniques capable of reconstructing original biometric inputs from stored data, has underscored these security and privacy concerns.

To address these multifaceted threats, this work proposes a post-quantum, privacy-preserving authentication protocol for smart devices. Our approach eliminates the reliance on stored biometric templates by generating templateless, high-entropy cryptographic keys from stabilized biometric features, and integrates PUFs with zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) techniques. ZKP enables verification of a claim’s validity without disclosing any underlying secret or error source. By combining these innovations, the proposed protocol strengthens resilience against spoofing, inversion, and quantum attacks—offering a scalable, user-friendly security solution suitable for next-generation smart device ecosystems.

2. Background Information

Biometrics has significantly advanced Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) systems by enhancing security and making it increasingly challenging for criminals to compromise these systems [

6]. Among the various biometric methods, fingerprint scanning has been one of the most widely adopted. The effectiveness of MFA systems is closely tied to metrics like the False Rejection Rate (FRR) and False Acceptance Rate (FAR), which are critical in determining the accuracy and reliability of user identification [

12]. By optimizing these metrics, the overall performance of MFA systems can be significantly improved, leading to more secure authentication processes [

6,

13]. Historically, various methods have been employed in MFA, starting with the use of Personal Identification Numbers (PINs) or passwords [

6]. Over time, these were combined with tokens, such as cards, to provide an additional layer of security. The latest advancements in MFA technology have integrated biometric methods, particularly facial recognition, with traditional tokens or PINs to create more robust authentication systems. Research has also explored how factors like age, gender, and cognitive abilities impact the effectiveness of these authentication methods, highlighting the need for adaptable and inclusive security solutions. These developments underscore the evolving nature of MFA and the critical role that biometrics plays in its ongoing improvement [

12,

13].

A prominent example of biometric authentication in use today is facial recognition. This technology employs various techniques to identify individuals, including analysis of facial features and even the retina. However, recent advancements have also led to new security challenges, such as facial spoofing and deepfake attacks. In [

14], researchers combined facial recognition with a One-Time Password (OTP) system, where an OTP is sent via SMS to the user’s phone as a secondary authentication step. The system first scans the user’s face, and if a match is found in the database, it proceeds to send an OTP to the registered mobile number for verification [

14]. Despite its potential, this approach has several limitations. One significant issue is that the system lacks the ability to confirm whether an OTP has already been sent, leading to repeated and unnecessary OTP transmissions. This flaw reduces the system’s reliability and user experience. Furthermore, the hardware used in this system, particularly the microcontrollers, limits its scalability. These components have limited processing power, which can impede the system’s deployment in large-scale environments. Another critical vulnerability involves SIMJacker attacks, where attackers send malicious messages containing vulnerable links or code to gain access to SIM cards. This exploitation can allow attackers to intercept OTPs intended for device verification, leading to significant security breaches. These challenges highlight the need for more robust and scalable biometric authentication systems that can better withstand emerging threats.

Another study explored a multi-factor authentication system that combines fingerprint recognition with a secret key (S

k) to enhance security [

15]. In this system, the secret key S

k is used to generate a user-specific random matrix, which is stored on a smart card. During enrollment, both the S

k and the user’s fingerprint are used to create a unique vector, which is then stored in a central database [

15]. For authentication, the user asserts their identity and inputs both their fingerprint and the S

k. The system then generates a verification vector using the same process. If this verification vector matches the one stored in the database, the user is successfully authenticated. However, this system has some critical vulnerabilities. If the secret key S

k is compromised, it can lead to unauthorized access, as fraudsters could potentially generate the correct vector and gain access to the system. Additionally, the need to store sensitive information such as the vectors in a centralized database raises significant security concerns. If this database is breached, attackers could steal the stored vectors and use them to impersonate users, potentially gaining access to sensitive information such as financial information, medical records, personal identification information. Theft of such data can lead to severe consequences, including financial loss, identity theft, and long-term damage to the user’s personal and professional life.

Recent studies have highlighted the vulnerability of face recognition systems to template inversion(TI) attacks, where adversaries attempt to reconstruct face images from stored biometric templates. In particular, [

16] demonstrated that high resolution, realistic face images can be generated from facial templates using only synthetic training data. Their method employed StyleGAN to map biometric templates back into the generator’s latent space, enabling the recovery of detailed facial characteristics without relying on real datasets. The reliance on centralized storage also introduces risks of data corruption, where any alteration in the stored information could lead to failed authentications or unauthorized access. This highlights the potential security pitfalls of storing both the secret key and biometric data, emphasizing the need for more secure and decentralized approaches to biometric authentication.

In [

17,

18] by Cambou, Bertrand et al., describes a method of using Challenge-Response-Pair (CRP) to secure digital files. The subset protocol presented for securing digital files in distributed and zero-trust environments leverages a CRP mechanism that uniquely harnesses each digital file as a source of entropy for cryptographic operations. In this approach, the protection and verification of file authenticity occur both at distributed storage nodes and on terminal devices operating amid weak signals and obfuscating electromagnetic noise. By introducing nonces into the process, the message digests generated from hashed files become unique and unclonable, effectively enabling the files themselves to serve as PUFs within challenge-response protocols. During enrollment, randomized challenges elicit distinct subset responses used for secure cryptographic key generation and distribution while subsequent verification cycles repeat the CRP process for file authentication and decryption. Building on the subset protocol explained in [

17] through file specific CRP mechanisms, we have extended this technology to the domain of biometric authentication.

By harnessing the inherent uniqueness of human facial data, our approach utilizes biometric landmarks and the computed distances between them as PUF, seamlessly integrating this with the optimized subset protocol for biometric data. This methodology significantly elevates the security framework of biometric authentication systems by eliminating the need for permanent storage of facial data or cryptographic keys—both are generated dynamically for each authentication instance. The objective of this solution is

To develop a novel, templateless biometric authentication protocol that dynamically generates ephemeral cryptographic keys from stable facial landmarks using a subset challenge response mechanism ensuring neither biometric templates nor sensitive keys are ever stored, and all data remains irreversible and resistant to inversion attacks.

To enhance authentication security and resiliency against next-generation threats including deepfakes, spoofing, and quantum adversaries, by promoting expression based authentication, injecting noise into the key generated in the biometric process, leveraging post-quantum cryptographic (PQC) algorithms for data protection, and integrating machine learning based liveness detection.

To implement robust MFA by binding biometric-derived cryptographic key and key generated from SRAM PUF to further strengthen security against cloning, replay, and side-channel attacks in distributed, zero-trust environments.

This paper is organized to provide a detailed, end-to-end account of the proposed authentication protocol and its empirical evaluation.

Section 2 offers a comprehensive review of prior work on MFA, PUF, and biometric security, outlining the challenges of template storage, emerging threats such as deepfakes, and recent developments in secure cryptographic protocols.

Section 3 presents the core protocols in depth, encompassing both the 2D and 3D facial biometric key generation and recovery workflows, landmark stability analysis, challenge-response subset algorithms, noise injection, and the integration of MFA via SRAM PUF. Cryptographic key generation/recovery and error correction techniques are explicitly detailed, along with methods for liveness assurance and resilience against template inversion attacks.

Section 4 delivers a thorough performance and security analysis, including entropy calculations, robustness under variable environmental and operational scenarios, detailed error rate characterization (FAR, and FRR), and comparative benchmarking against existing methods. This structure culminates in a discussion synthesizing practical deployment insights, operational guidance for threshold and scenario selection, and directions for future research on privacy-preserving, post-quantum biometric authentication.

3. Templateless Biometrics

3.1. Enrollment of Face

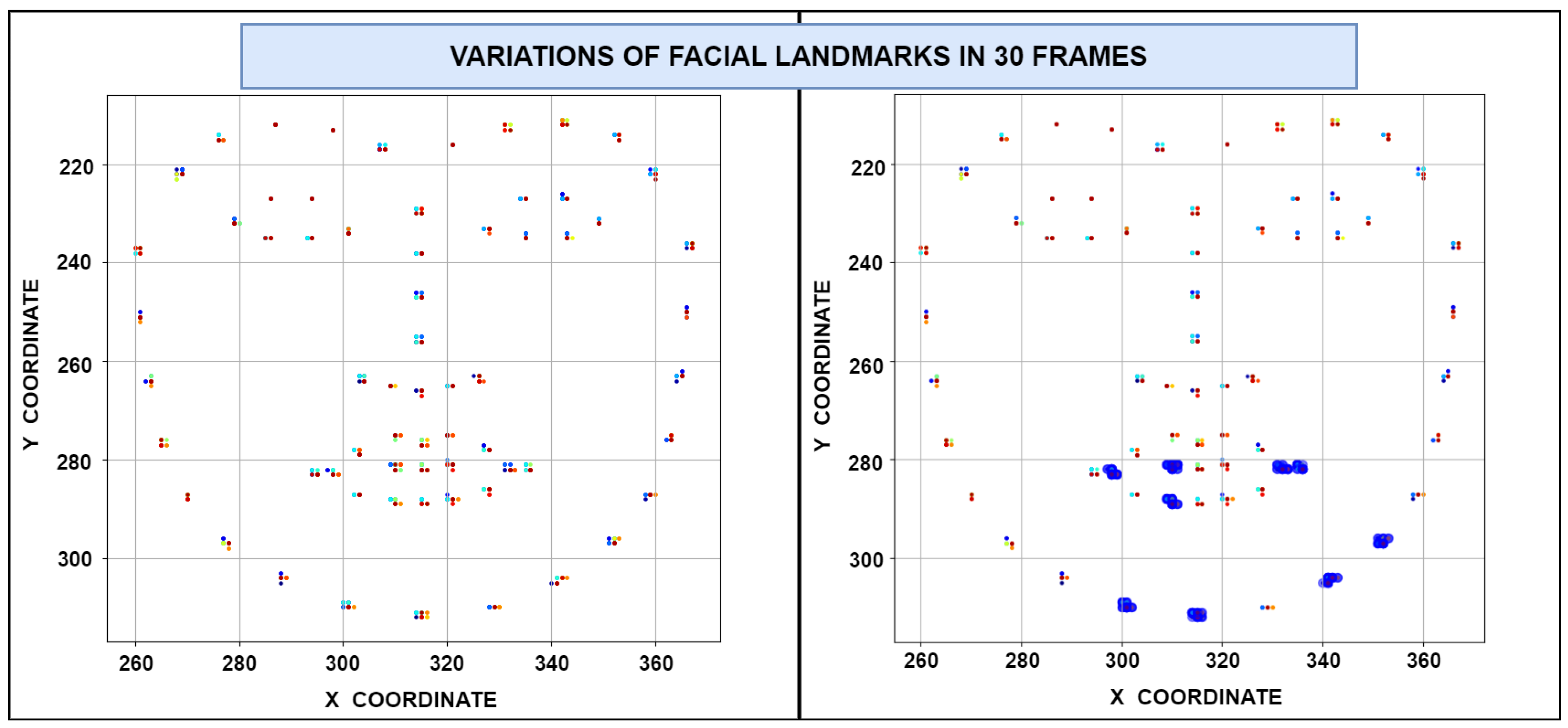

The resources needed to utilize biometric data include a camera. This camera can be sourced from a variety of devices such as mobile phones or laptops, making it a convenient and accessible tool for implementing biometric-based authentication systems on every smart device. The face enrollment procedure utilizes the "dlib" or "mediapipe" python package, employing 68 or 468 landmark respectively to pinpoint various facial features such as the eyes, nose, chin, and ears. These landmarks serve as key identifiers for individuals. During the initial face enrollment, multiple frames of the face are captured, and landmarks are applied to each frame. These landmark positions are then compared across all images, with areas obscured by shadows or inadequate lighting masked out from consideration in the authentication process. Additionally, comparisons are made between landmarks from each frame, with those exhibiting the greatest variations being masked as shown in

Figure 1. These masked landmarks are excluded from authentication, effectively lowering the rates of FAR and FRR.

To ensure that the individual enrolling or authenticating is a living person and not an image or a replica, a liveliness test is conducted. This protocol employs an open-source code that leverages the blinking of the eyes to measure variation. If the variation falls below 2, it confirms that the user is a real person and not a replica [

19]. Additionally, machine learning models integrated within the deepfake python package further analyze subtle facial movements and micro-expressions, enhancing the detection of AI-generated media and spoofing attacks. By combining physiological measurements with advanced machine learning-based behavioral analysis, the protocol delivers robust liveliness detection, effectively mitigating both traditional and deepfake presentation threats.

3.2. Key Generation and Recovery Using 2D Facial Data

As the name of our protocol implies, this protocol is "templateless" meaning that the stored data used for key recovery cannot be easily reverse-engineered into exploitable biometric information. This approach significantly enhances privacy and reduces the risks of identity theft and spoofing, as the databases do not store any retrievable data on the user’s biometric identities. Instead, they only hold response information required to recover a user’s key, which is useless without both the legitimate user’s face and their two-factor authentication password. From an attacker’s standpoint, such a database offers little incentive for compromise, especially since it would be encrypted following standard best practices for digital information security.

3.2.1. Initial Enrollment/Registration

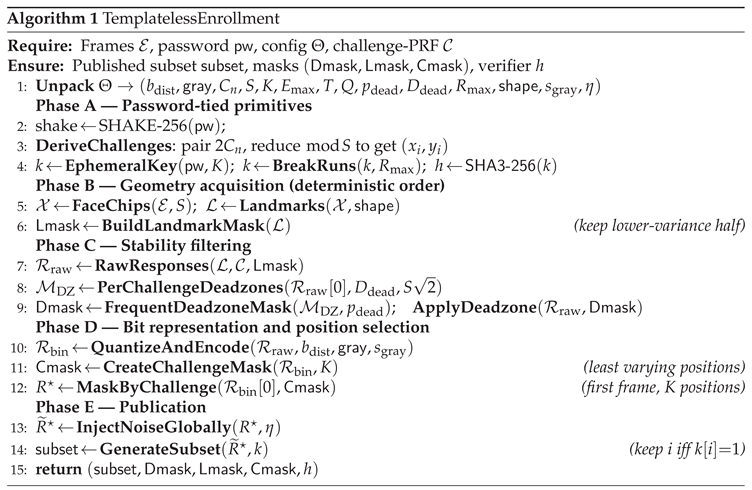

The initial enrollment process involves the steps outlined in

Section 3.1. Multiple frames of the user’s face are captured, and landmarks are recorded.

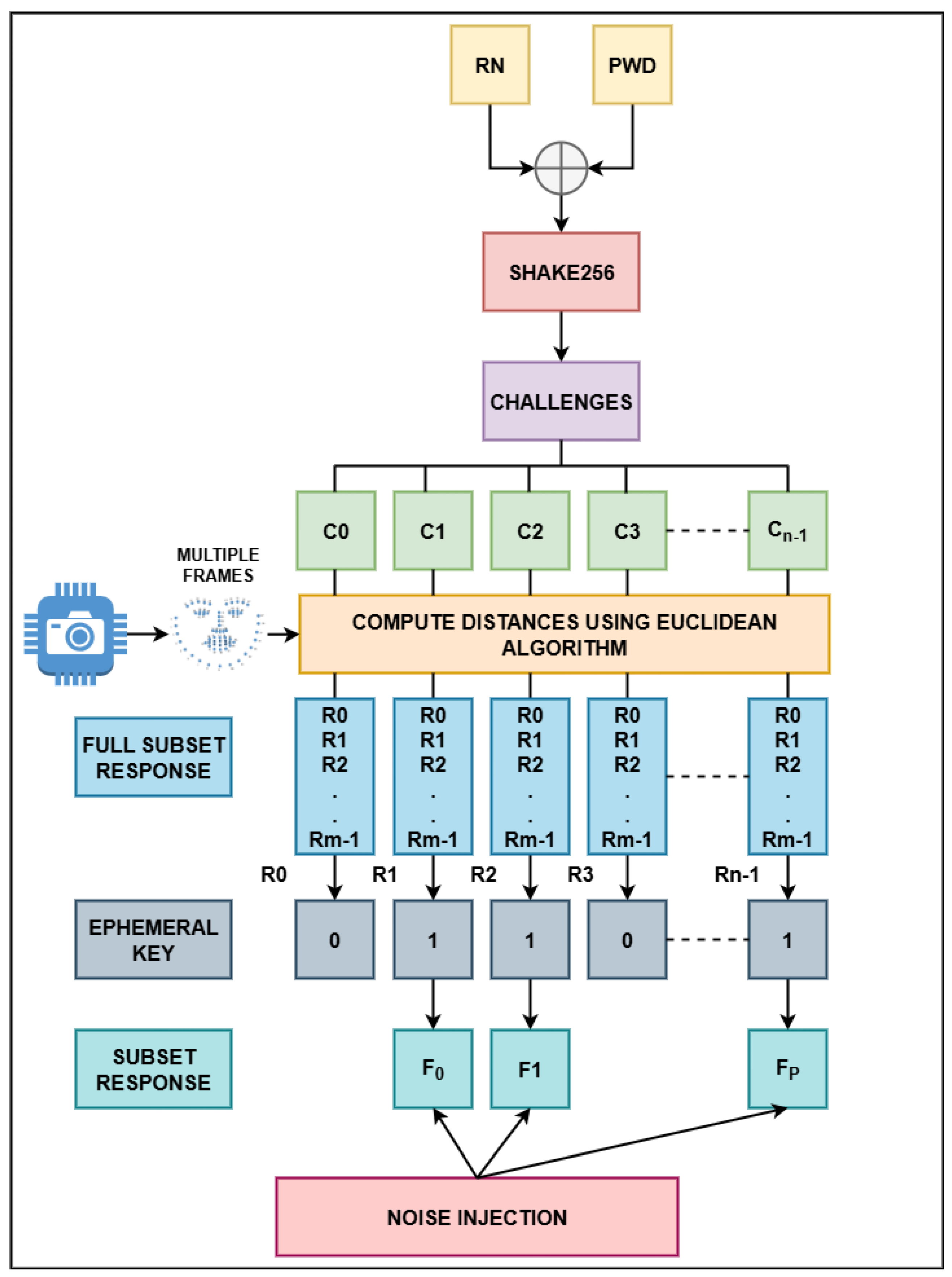

Figure 2 illustrates the enrollment/registration process where first, a random number

is combined with the user’s password

using an XOR operation to create a stream of bits, which is subsequently hashed with SHA3-512 and SHAKE256 to produce a message digest. This digest is then used to generate a set of

n challenges, represented as facial landmark coordinates

. For each captured frame, facial landmarks are analyzed to identify those with high variance and these unstable landmarks are excluded during key generation. Each generated challenge corresponds to a coordinate on a

frame, and the Euclidean distance between challenges and the stable landmarks is calculated, with additional masking applied to exclude distances near predefined transition points.

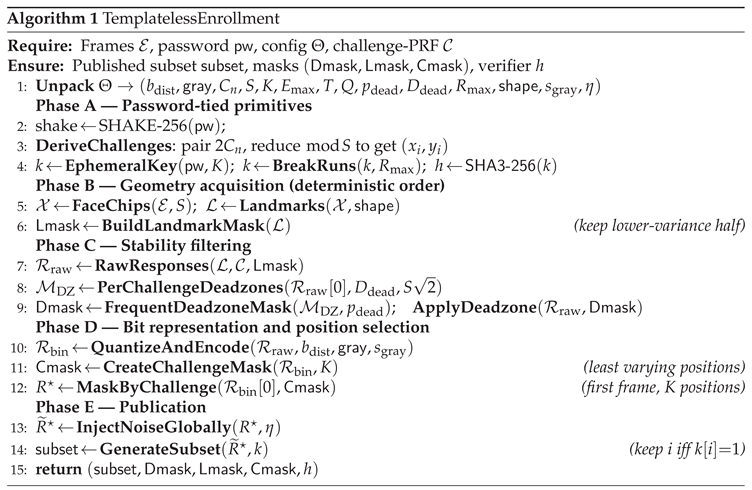

Next, the response distances are encoded using gray codes to will reduce the bit error rate, and each challenge thus produces a binary will reduce the bit error rate between consecutive, resulting in a collection of subset responses . A cryptographically secure ephemeral key K is generated from these responses, and if K contains long runs of consecutive zeros or ones exceeding a threshold, it is adjusted to randomize these runs. The ephemeral key K is then used for cryptographic operations, such as encrypting files or other sensitive data. From the ephemeral key, a subset of landmark responses corresponding to the set bits is selected. Random number , the hash of and the subset of the responses , are securely stored and all other intermediate data is deleted. Detailed flow of this is shown in Algorithm 1.

To further strengthen the resilience of the authentication protocol against inversion and side-channel attacks, two additional cryptographic obfuscation mechanisms are employed:

After quantizing and gray-coding the calculated distances between facial landmarks, a random subset of bits is removed while the order of the remaining bits is preserved. By incorporating only these selected segments of the encoded biometric representation into the final key material enhances security and minimizes the risk of information leakage from the overall biometric dataset.

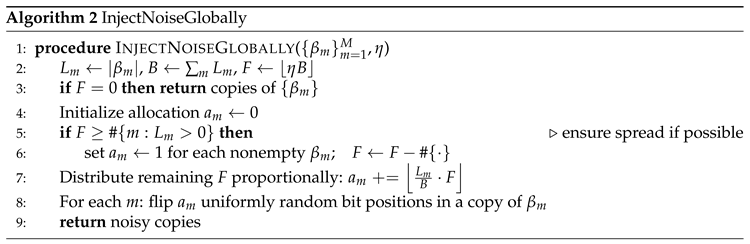

The second additional step is noise injection. After masking and encoding the per-challenge bitstrings for the selected enrollment frame (as depicted in

Figure 2) and before gating by the ephemeral key

K, noise is injected across the entire collection of encoded responses. The detailed description of the method is explained in the Algorithm 2. This obfuscation is applied only during the enrollment phase, ensuring that while additional uncertainty is injected into the stored representations, legitimate key recovery during authentication remains unaffected.

Together with rigorous liveliness testing, gray code bit selection, double masking and noise injection, these techniques significantly harden the system against AI driven attacks, statistical analysis and direct attacks on the biometric keying process.

Algorithm for Key Generation is as follows:

Inputs: Password

(bytes), frames

(enrollment) or

(recovery), and config

where

= bits per distance,

,

challenges,

S face-chip size (px),

K key length (bits),

uncertainty budget,

T matching tolerance,

Q threshold for entering error correction,

deadzone percentage,

deadzone density,

max zero-run length in key,

,

,

optional Gray bit-slicing seed, and

noise-injection rate.

Password binds three invariants reused at recovery: (i) challenge points , (ii) landmark order (via password-seeded shuffle), (iii) gating pattern of the one-time key k. Stability pipeline (landmark selection → deadzones → identical quantization) ensures comparable bits across sessions.

-

Password-tied primitives & helpers

- -

DeriveChallenges: Expand with SHAKE-256 long enough for coordinates. Read the values and reduce to get coordinates. Same method is used in the recovery.

- -

BreakRuns: A sliding window of length scans sequence k, and if the window contains only zeros, one bit is flipped to 1 to prevent extended zero runs and enforce distributed activations.

- -

HashKey: Hash representation of k which uses SHA-256 and SHAKE-256.

- -

GenerateSubset: Given an ordered list of responses, 50% of the responses are stored while the rest are deleted.

- -

GrayCode bit selection/Pick3: After converting distance s to binary using gray code, we deterministically selects g bit indices from . This returns the remaining indices in increasing order, preserving bit order.

-

Face Detection & Geometry

- -

FaceChips: Detect a single face per frame and align it to a square chip.

- -

Landmarks: Extract 2D landmarks for each face chip using . Coordinates are pixel positions in the chip reference frame.

- -

BuildLandmarkMask: Landmarks with high variance in their location across all frames are masked and the stable ones are used.

-

Challenge Responses

- -

RawResponses: For each challenge , compute Euclidean distances to landmarks with and collect them into a list. The output per frame is a list of lists (one list per challenge).

-

Deadzones (stability gating)

- -

PerChallengeDeadzones: Partition into equal bins. For each challenge, identify indices that fall near transition boundaries and mark them as unstable, with stable regions left unmarked.

- -

FrequentDeadzoneMask: Aggregate these instability markings across all challenges and construct a global mask that flags the most frequently unstable positions for exclusion.

- -

ApplyDeadzone: Apply in every frame/challenge, drop distances where so later quantization avoids unstable indices.

-

Global noise injection:

-

Final Step

- -

GenerateSubset: After noise injection, publish only the responses whose indices are selected; this yields the stored subset.

- -

MaskGeneration: Deadzone/challenge masks use , . Landmark mask uses (selected landmarks)

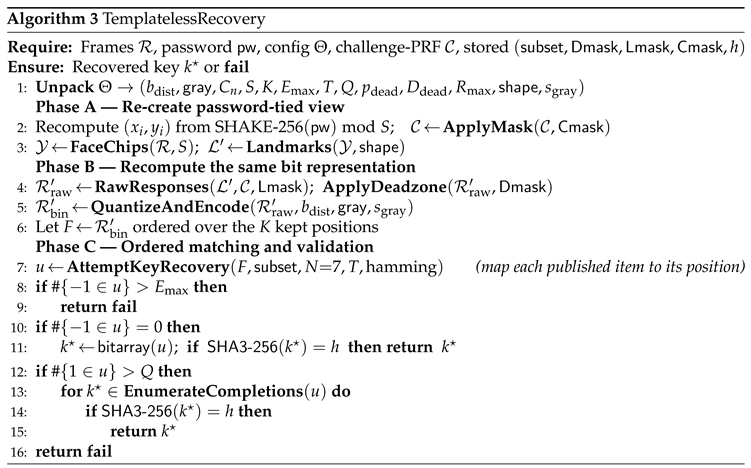

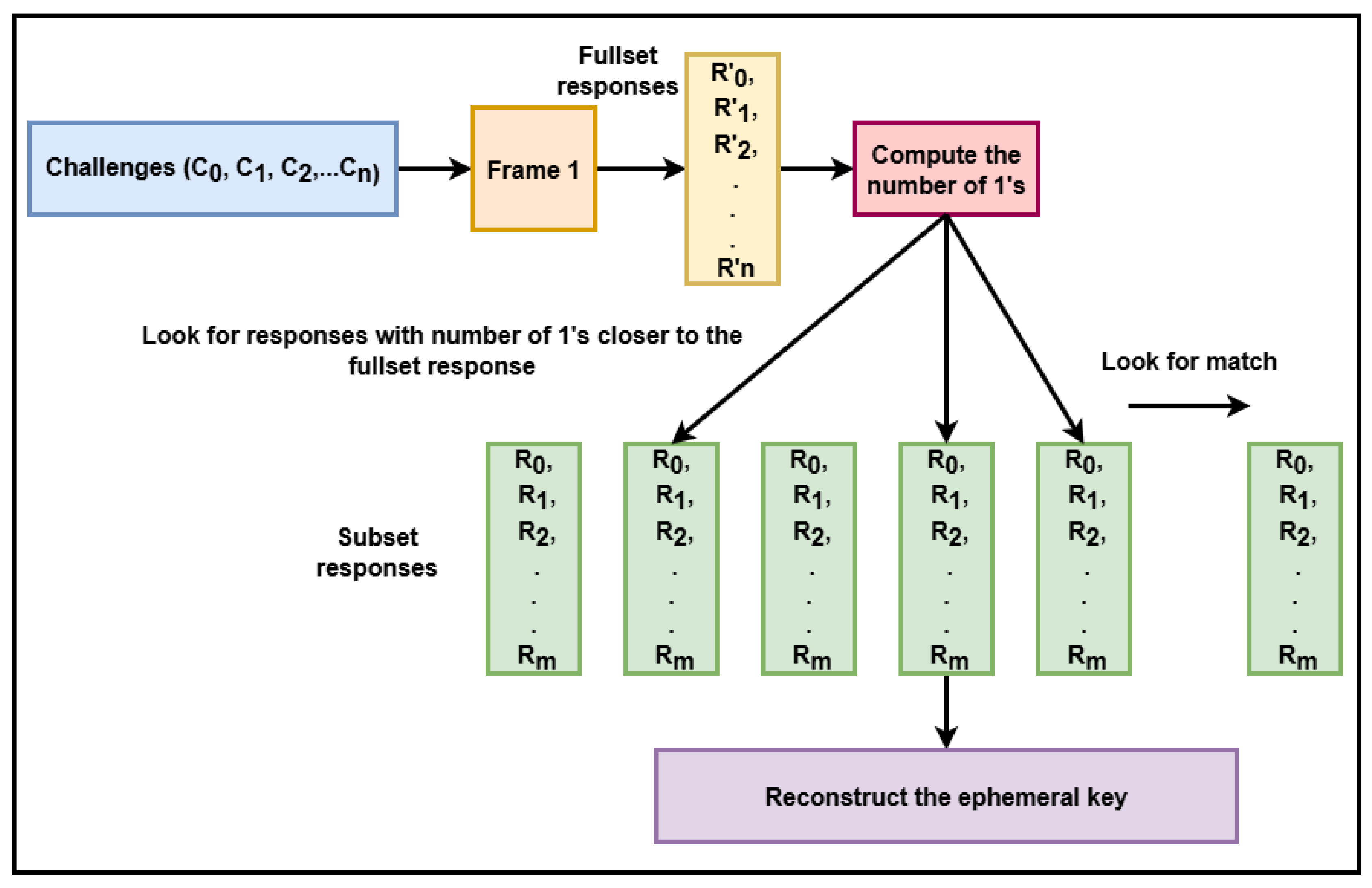

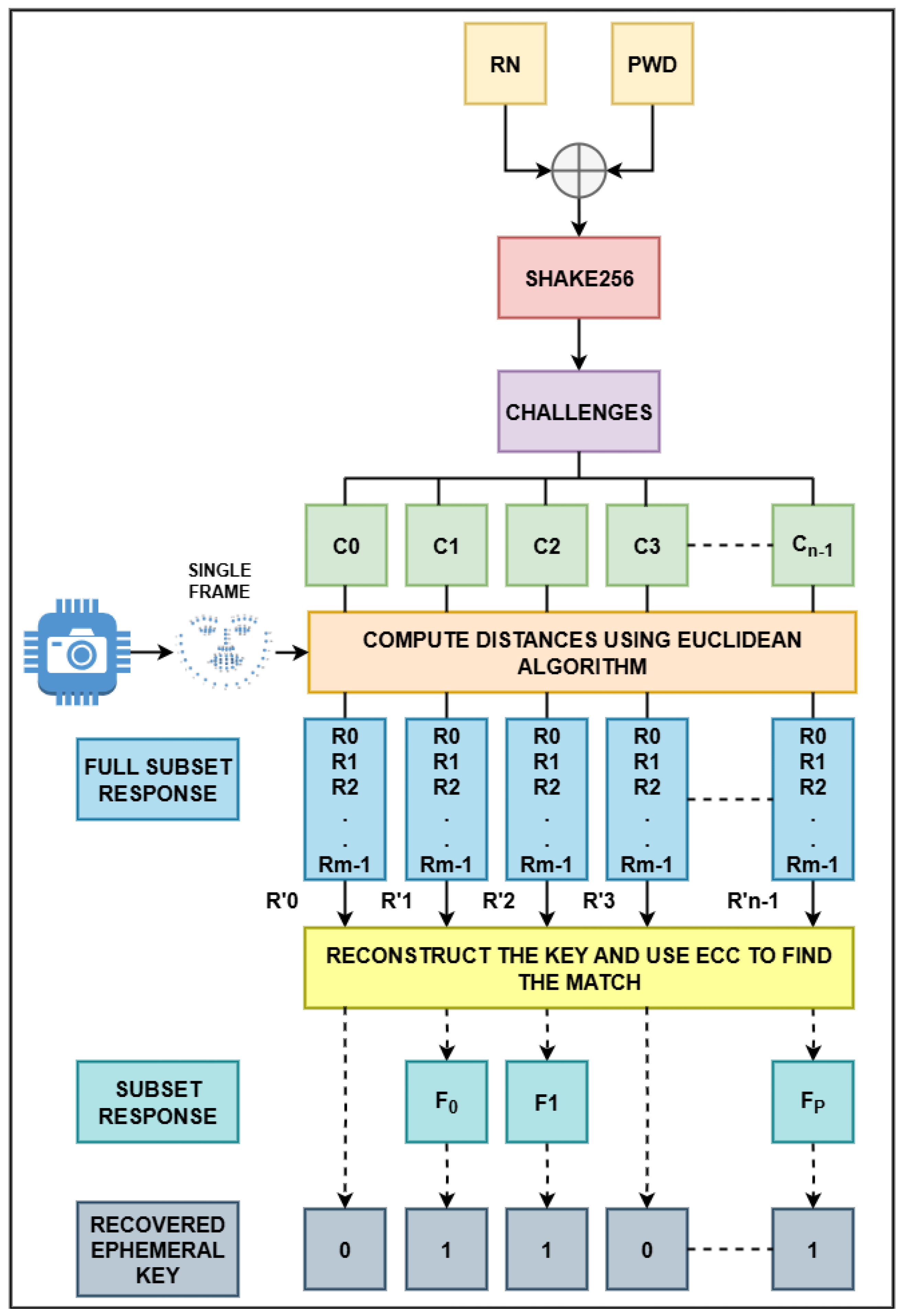

3.2.2. Key Recovery

When an authentication request is initiated, the system utilizes the stored subset of responses, the random number

, and the hash of the enrollment key

for key recovery, as illustrated in

Figure 3. During authentication, a single frame of the user’s face is captured and facial landmarks are mapped. Consistent with the enrollment procedure,

and the password

undergo an XOR operation to produce a bit stream, which is subsequently hashed with SHA3-512 and SHAKE256 to yield a message digest. This digest is then used to generate a set of

n challenge coordinates on the face. The distances between these challenges and the detected landmarks are computed, producing a new set of responses

. Assuming an error-free scenario, each stored subset response

is compared with the corresponding component in the authentication responses; if they match, the associated bit in the reconstructed ephemeral key

is set to 1, and if not, to 0. If the number of 1’s in

exceeds a set threshold, its hash is compared to the stored

. A successful match confirms the identity and authorizes decryption using

. In the event of discrepancies, error correction mechanisms are employed to facilitate key recovery. The detailed description of this process is shown in Algorithm 3.

Algorithm for Key Recovery is as follows:

3.2.3. Error Correction

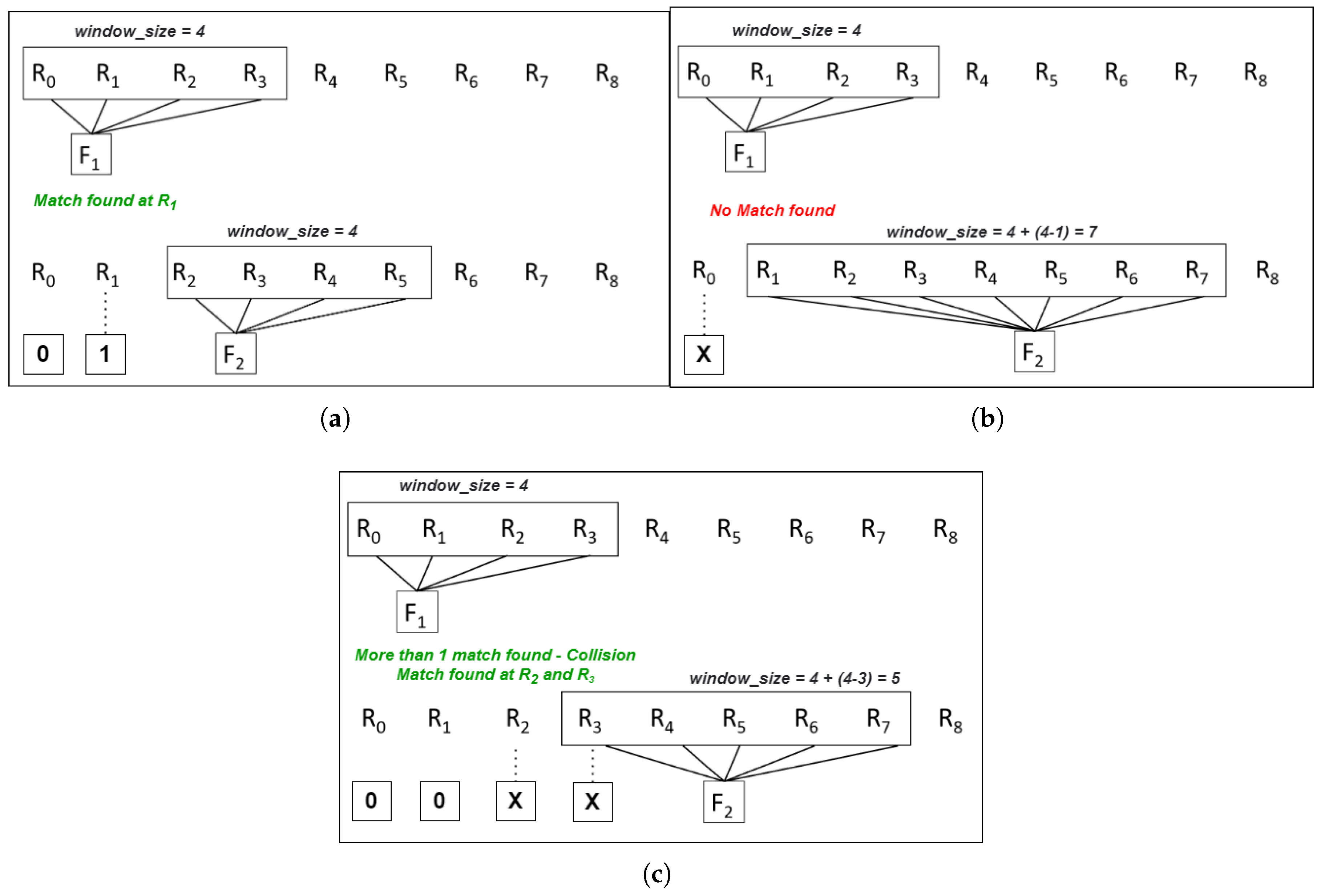

In the event that the initial key recovery does not produce the correct ephemeral key, error correction is used. Initial steps involve marking the binary stream positions 0 and 1 where we are certain and the unsure positions, which could either be 0 or 1, are set as "X". A window is defined to match the client-generated full responses with the subset response, in accordance with the threshold number of consecutive 0’s an ephemeral key can have. It is assumed that every window will have at least one match.

Let’s consider, , and The error correction handles three cases:

-

Case 1: One match found.

Consider we have 8 responses as shown in

Figure 4(a). In this scenario, the search begins by finding a match for subset

. The comparison starts with

and considers the first 4 full subset responses generated by the client. It is observed that a match is found at

, i.e.,

, so the binary stream at the

location is set to "1", and the other unmatched locations before

are set to "0". To continue the search, the

remains unchanged, but

.

-

Case 2: No match found.

Figure 4(b) illustrates the scenario when no match is found. Considering

and , while attempting to find a match for subset , the first 4 full subset responses are examined for a match. Since no matches are found, the window is shifted by one, i.e., is set to 1, and is marked as "X". The window size is expanded to . This expansion accounts for the possibility that might find a match in either , , or . Assuming that every window has one match, the search extends to the next 4 values of the full subset response to find a match for .

-

Case 3: More than one match found.

Figure 4(c) depicts the scenario when more than one match is found. Considering

and

, while attempting to find a match for subset

, the first 4 full subset responses are examined. When multiple matches occur, it is termed a collision. In this example, matches were found at

and

, indicating a potential presence of a 1 at either of these positions. Therefore, both positions are marked as "X", and the responses before the first match are set to 0. In this case,

is set to 3,

is set to

, and the window size is adjusted to

.

After generating the ternary key, the system generates an exhaustive set of keys by changing the values of the uncertain position to 0 and 1. The hash of these keys is generated and compared with

to find a match. In cases where a match is not found, the system denies authentication, and the entire recovery process is re-initiated. For a detailed description of the key recovery protocol, the readers are referred to [

20,

21].

3.3. Key Generation and Recovery Using 3D Facial Data

While 2D facial recognition provides a valuable foundation for biometric authentication and remains widely adopted in many security systems, the integration of 3D facial recognition offers additional capabilities that further enhance accuracy, security, and robustness [

22]. By incorporating depth and geometric data, 3D facial recognition enables natural resistance to common presentation attacks such as those involving photos or digital images, due to its ability to capture the structural intricacies of the human face [

19]. This added dimensionality and adaptability make 3D technology exceptionally well-suited for a wide variety of applications, ranging from personal device security to mission-critical environments like law enforcement, border control, and high-security access management.

The core protocol for the proposed 3D key generation and recovery from biometric data remains consistent with the algorithm described in

Section 3.2. The principal distinction is the increased number of frames and diversity of angles captured during enrollment, as illustrated in

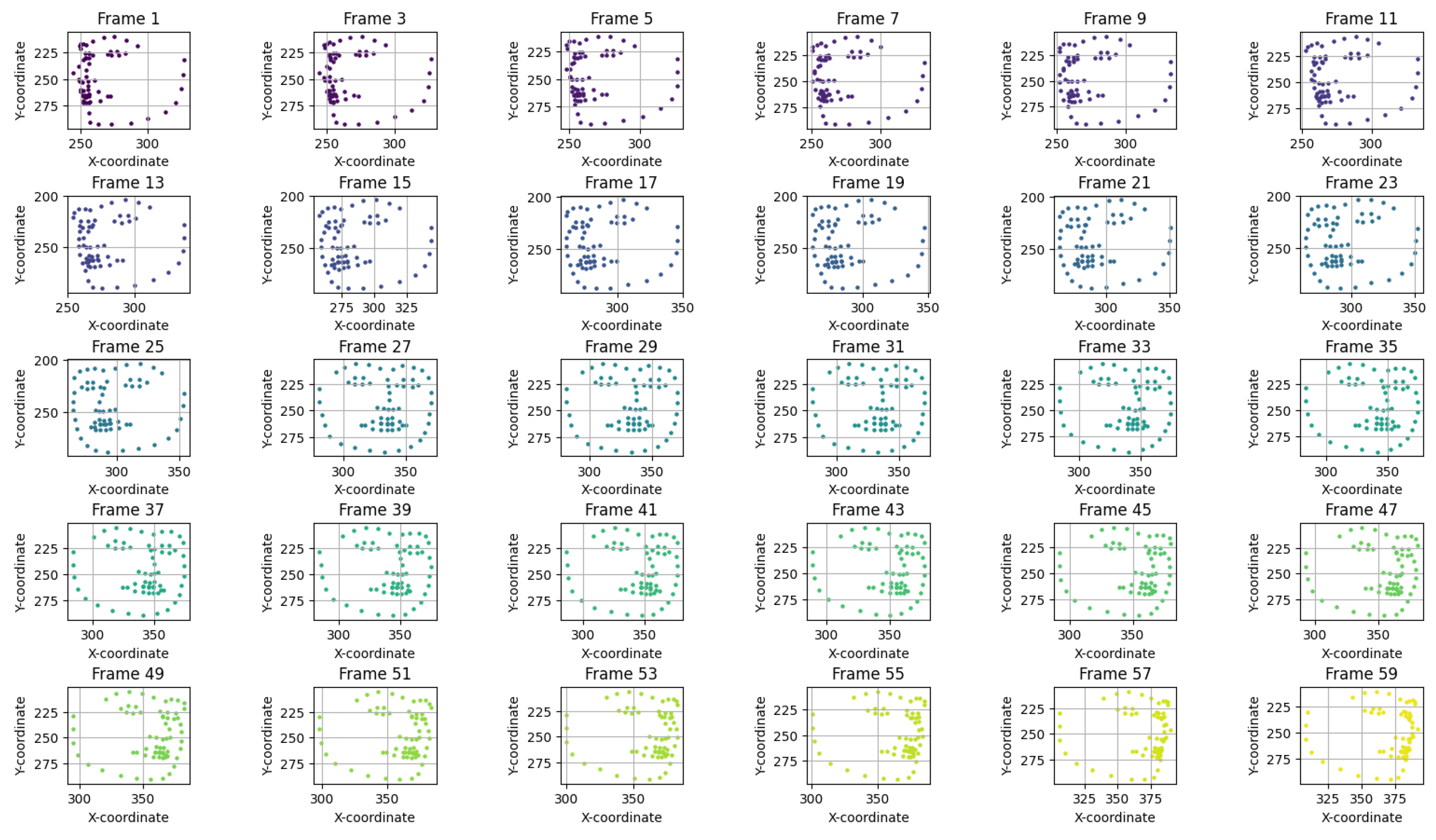

Figure 5. Multiple frames are systematically acquired from various angles to robustly characterize the subject’s facial geometry. For each captured frame, facial landmarks are meticulously extracted and recorded, forming the basis for generating robust subset responses.

3.3.1. Initial Enrollment

As depicted in

Figure 6, the enrollment process involves capturing a comprehensive set of 60 frames from a broad range of facial angles. Landmarks are detected in each frame, and the templateless key generation method, as outlined in

Section 3.2.1, is applied to yield unique subset responses per frame.

For each frame the same challenge is formed by hashing a random nonce (RN) with the user’s password (PWD).

For each challenge, a unique subset response is generated and used to derive an ephemeral key

K, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The key generation methodology follows the process detailed in

Section 3.2.1.

Similar to the 2D the essential subset responses, RN, and the hash of the ephemeral key are securely stored. All other enrollment data, including raw landmarks, are promptly deleted to ensure privacy and security.

3.3.2. Key Recovery

During authentication, a live frame is captured, and the stored subset responses, together with the corresponding and , are utilized to reconstruct the ephemeral key K. The recovery process unfolds as follows:

The challenge is regenerated from the

and

and applied to the live capture, producing a fresh set of responses using the methodology from

Section 3.2.2.

To reconstruct K, a subset response is randomly selected. If the ephemeral key generated () closely matches the expected response profile (i.e., the number of 1’s is near the subset length with low uncertainty), the recovery continues with this set. If not, another subset is randomly chosen, and the process repeats.

This iterative matching substantially reduces latency in key recovery; however, to prevent extended search times, a threshold is enforced. If recovery exceeds the allotted time, access is denied and the user must re-initiate authentication.

Once a ternary key with the appropriate number of 1’s and minimal ambiguity is identified, an exhaustive search is conducted by toggling uncertain positions. All candidate keys are hashed and compared to the stored . A match grants access; otherwise, the process is restarted.

This methodology enables effective utilization of 3D facial data from multiple angles during authentication, significantly improving recognition accuracy even under challenging conditions such as variable lighting, expressions, or occlusions. Furthermore, the protocol’s versatility allows its extension beyond facial biometrics to general object recognition, subject to landmark accessibility. Its adaptability and security make it a powerful solution for a wide array of scenarios, from rapid, secure identification in high-stakes environments like airports and border crossings to reliable biometric authentication in diverse digital applications, offering tangible benefits in security, operational efficiency, and user convenience.

Figure 7.

Authentication of face from an angle and reconstruction of ephemeral key.

Figure 7.

Authentication of face from an angle and reconstruction of ephemeral key.

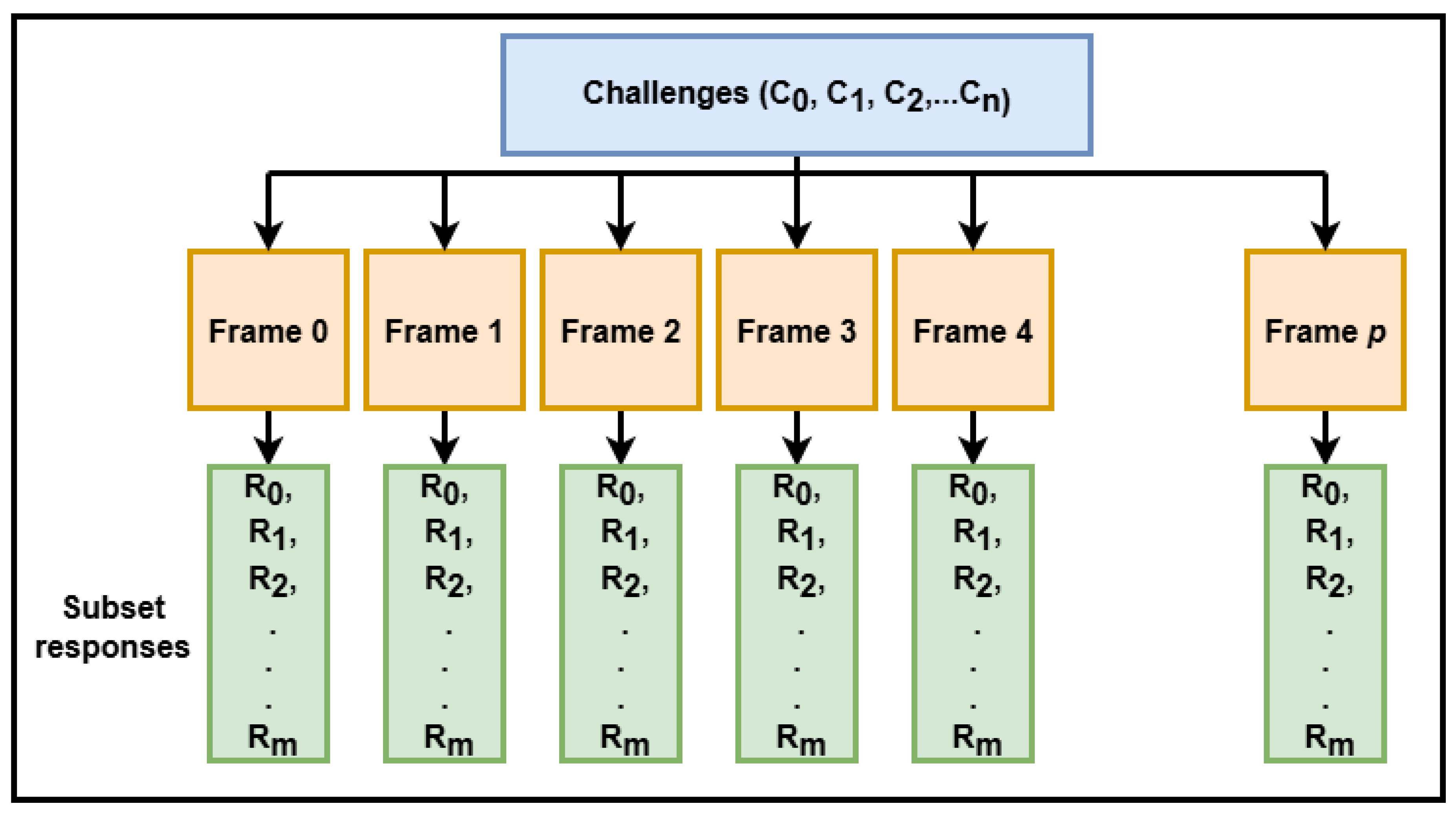

3.4. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) with 2D/3D Biometry and SRAM PUF

MFA is a security process requiring users to present two or more distinct forms of identification before accessing a system, relying on three primary factors: inherence (e.g., fingerprint scanning, facial recognition), knowledge (e.g., passwords, PINs), and possession (e.g., smart cards, OTP tokens) [

6,

23]. By integrating multiple authentication factors, MFA provides a robust defense against attacks; even if an attacker compromises a user’s password, they would still need additional factors to succeed [

24,

25]. To further mitigate risks such as modeling or spoofing attacks, this paper proposes an MFA protocol design that leverages the CRP mechanism [

26,

27], utilizing templateless key generation and recovery through subset responses with biometric data and liveliness factor (Inherence Factor) as discussed in

Section 3.2. This approach also incorporates CRP mechanism using a SRAM PUF token (Possession Factor) [

27,

28,

29] as shown in

Figure 8, and a password (Knowledge Factor) for authentication.

The method of using SRAM PUF for key generation and recovery is inspired from paper by Jain, Saloni et al. [

30]. This paper proposes an optimized protocol for enhancing industrial IoT device security by integrating SRAM-based PUF, error correction codes (ECC) or Response Based Cryptography (RBC) [

31], PQC algorithms, and ZKP systems to efficiently generate and recover one-time cryptographic keys with low latency and minimal error rates. Advanced techniques such as stable cell filtering and addressing schemes maximize key entropy and randomness from PUF responses, while flexible key lengths and integration with CRYSTALS-KYBER and CRYSTAL-DILITHIUM provide quantum-resistant security.

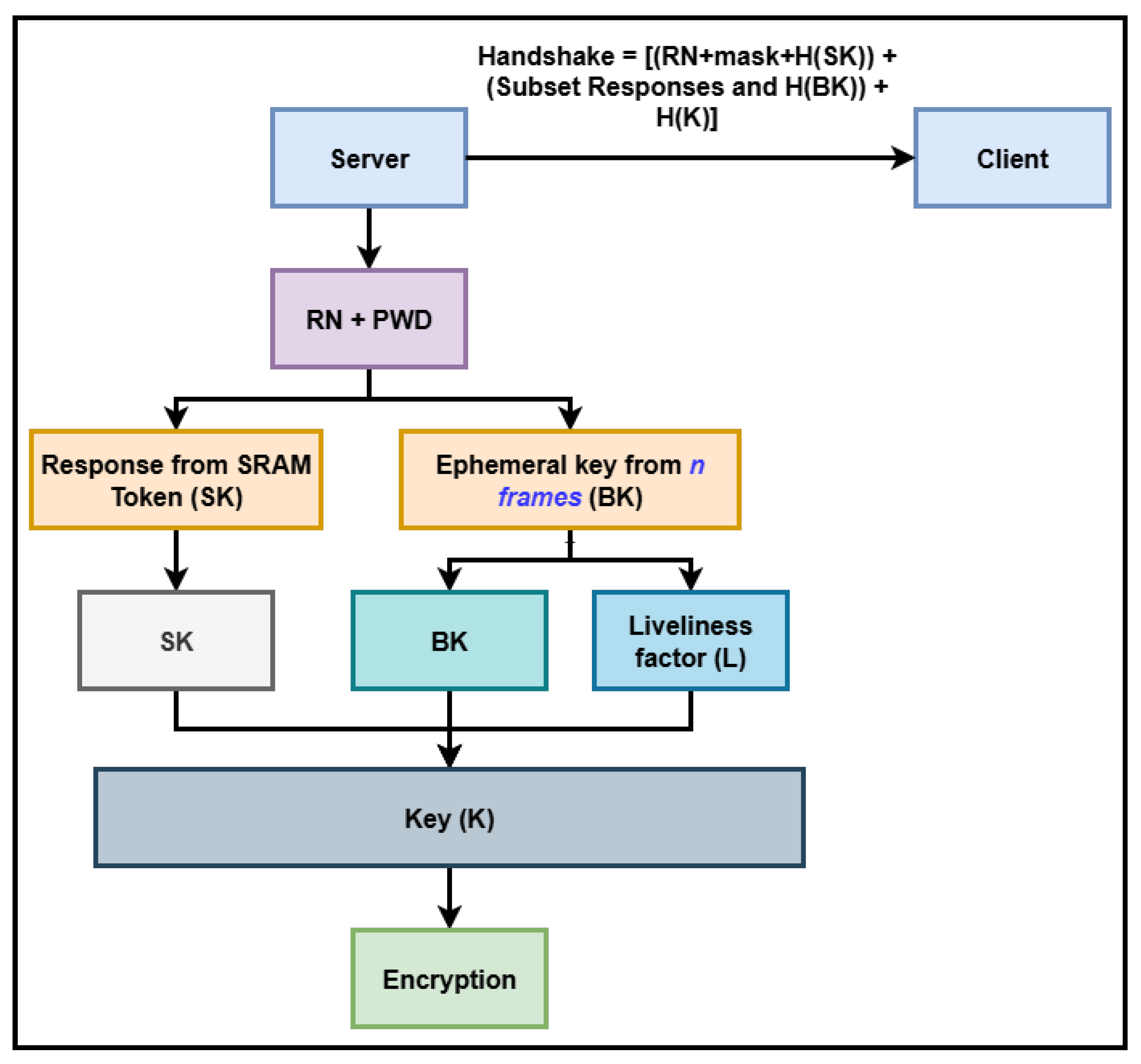

3.4.1. MFA Protocol Design

The enrollment process for this protocol involves two main steps: the enrollment of the SRAM PUF, and the enrollment of the user’s biometric data. The key generation process, illustrated in

Figure 9, proceeds as follows:

For SRAM PUF enrollment, the SRAM PUF is read multiple times to filter unstable cells, and stable responses are used to generate high entropy responses.

The key generation process initiates with the server generating a RN, while the user provides a PWD. These inputs undergo hashing using SHA3-512 and SHAKE256, resulting in a message digest.

Further, challenge-response pair mechanism (CRPM) utilizing SRAM PUF is employed to generate challenges. These challenges are utilized to determine the addresses of the cells that need to be read from the SRAM [

30,

32].

The SRAM PUF utilizes the enrollment to generate a response, denoted as .

Next with the biometric data, the hash is utilized to generate challenges, facilitating the calculation of the distance between each challenge and the landmarks of the user’s face. This process results in the generation of a full set of responses as detailed in

Section 3.2.

Following this, the protocol generates an ephemeral key, denoted as , and produces a subset response utilized during the recovery process.

During the process of ephemeral key generation using the biometric data, a liveliness test is conducted to ensure the absence of any spoofing attacks. The outcome of this liveliness test is denoted as L and is utilized in the generation of the final key, denoted as K.

The final key

K is generated by combining

,

, and

L through an XOR operation followed by a modulo operation. This resulting key

K is then employed in encryption algorithms such as AES, Double Encryption using AES, CRYSTAL-KYBER, or CRYSTAL-DILITHIUM [

33] to secure digital files.

During this process the , hash of the SRAM PUF response , subset responses and hash of the ephemeral key is stored as handshake. This handshake is shared with the client during the authentication process.

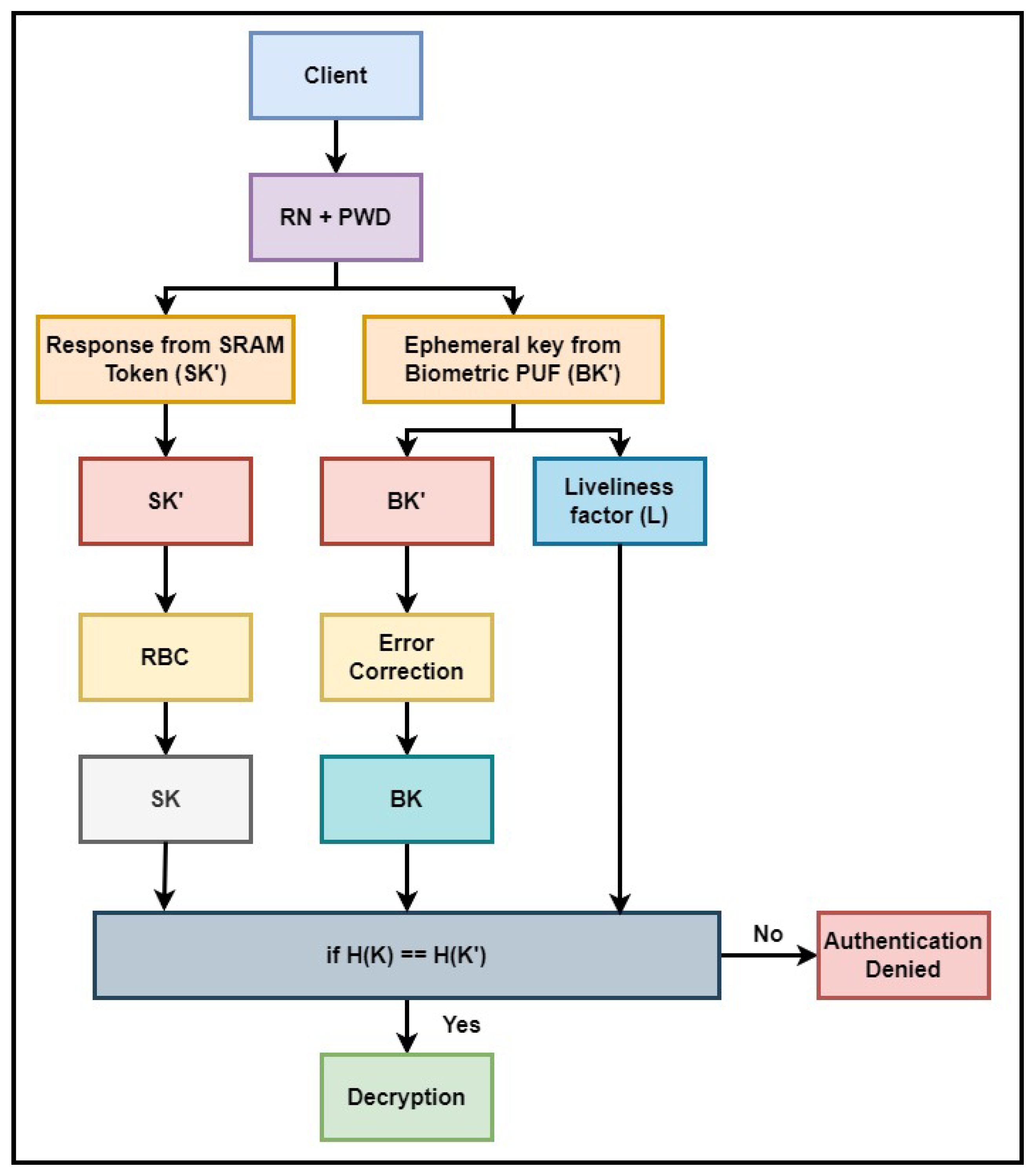

In the key recovery process for authentication, successful authentication requires the user to possess both the SRAM token and their biometric information along with the personal password. The authentication process, depicted in

Figure 10, involves a sequential flow detailed below:

Utilizing the handshake, the client extracts the RN, while the user inputs the PWD, both of which undergo one-way hashing to produce a message digest. This message digest is employed to generate challenges for extracting responses from the SRAM PUF and ephemeral keys from the biometric data.

The SRAM PUF generates a response , while the biometry data produces two outputs: the potential ephemeral key and the liveliness factor L.

undergoes error management methods like Response Based Cryptography [

34] to identify and manage errors and extract

. Similarly, the subset response method generates the potential ephemeral key

with uncertain positions as detailed in

Section 3.2.2, which is passed through the error correction method detailed in

Section 3.2.3 to determine the ephemeral key

.

Combining , , and L generates the final key . The hash of is then compared with . If a match is found, decryption of the digital file is initiated; otherwise, authentication is denied.

The complexity of generating the final key K from multiple factors in the MFA system makes it impossible to pinpoint which specific factor contributed to any errors resulting in authentication failure.

The lack of knowledge regarding which factor caused authentication failure and enhanced entropy of the keys makes this multi-layered authentication system effective in enhancing the security of various applications.

4. Results

4.1. Entropy Analysis

Entropy represents the measure of unpredictability and randomness critical to the security of biometric and token-based authentication systems.

Biometric Computation: For landmark-based face biometrics, entropy analysis considers both the immense combinatorial possibilities from grid selection and landmark combinations, and the impact of the key length on effective security. In the proposed system, the biometric entropy is a function of:

The selection of k unique coordinates from grid .

-

The assignment of l facial landmarks from a total set L to each selected point. Entropy Computation is represented as:

Key length generated is:

256 unique grid coordinates selected:

For each coordinate, consider l = 32 stable landmarks out of the L = 68 or 468 landmarks:

The resulting entropy is:

Using the above equation, with 68 available landmarks, selecting 32 stable landmarks within a grid results in approximately bits of entropy, representing the number of possible key combinations. Increasing the grid size or the number of chosen landmarks both raise this value; for example, using 468 landmarks instead of 68 with the same selection size boosts the entropy to around bits. This protocol is designed to be flexible; its parameters, such as the number of landmarks and selections, grid size, key length, can be easily adjusted to suit different applications and security requirements, allowing for scalability as needed.

When the system extracts a binary key of length m (for eg., 128, 256, 512, or 1024 bits) by quantizing and encoding selected distances, the effective entropy is limited by both the number of reliably recoverable key bits and the combinatorial selection space. For a 256-bit key, the attacker must search for possible values, but if the raw entropy from landmark selection and grid choices exceeds 256 bits, the full keyspace is utilized. So, as the key length increases, the entropy from the landmark/grid combination must be sufficient to populate all the key bits with true randomness. Here, the use of hundreds of landmark/grid pairs accelerates the growth in possible combinations, easily supporting very large, quantum-safe keys. With 68 landmarks, even a conservative subsets provide entropy far exceeding i.e., the minimum for post-quantum secure authentication. With 468 landmarks, the number of possible landmark subsets per coordinate grows from to , providing orders-of-magnitude greater entropy. For landmark choices for each response, entropy becomes effectively unbounded for practical purposes, supporting extremely long keys (512, 1024 bits) without risk of entropy exhaustion.

Combined Token and Biometric Entropy: For an SRAM-based token system, the token entropy

is derived from the number of cells in the SRAM PUF. Let

be the total number of SRAM cells, and

the number of cells used to compute each response. The token entropy can be expressed as:

The combined entropy is represented by :

Ensuring the upper bound is always at least as strong as the most secure subsystem, and vastly exceeding modern cryptographic standards.

Practical Implication: This analysis confirms that by increasing the number of landmarks (especially to 468), and with flexible, high key lengths, the system achieves an astronomically large keyspace and an entropy margin that robustly withstands both classical and quantum adversaries. This scalability in entropy directly translates to higher security assurances for both current and future cryptographic requirements.

4.2. Error Rate

Comprehensive analysis of error rates is fundamental for evaluating the security, resilience, and user experience of any biometric authentication protocol. The ability to quantify, interpret, and manage error probabilities directly influences system optimization. This prompts refinements in both algorithm design and hardware implementation. Excessive error rates can not only undermine security but also erode user trust, making robust error management essential for system acceptance and operational reliability.

At the core of our approach is a carefully defined error tolerance, which determines the maximum permissible bit error in ephemeral key reconstruction while maintaining successful authentication. This parameter is tunable: a more permissive threshold allows for greater adaptation to environmental noise and user variability (ideal for consumer electronics or public access points), whereas a stricter threshold enforces fine-grained matching-suitable for high-security environments such as military installations or banking vaults.

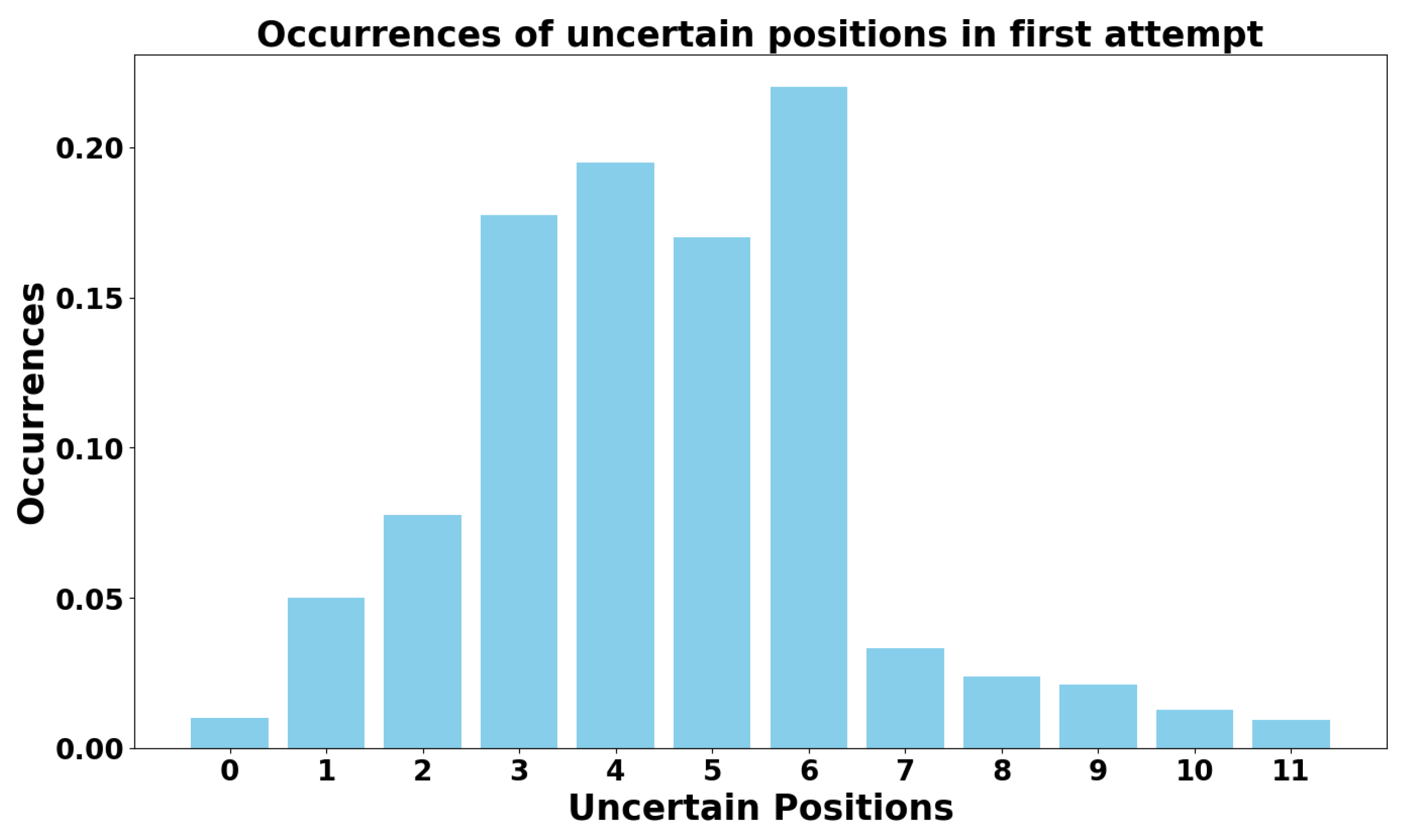

Figure 11.

Probability of occurrences of uncertain positions in the key when authentication is tried for the first time after enrollment.

Figure 11.

Probability of occurrences of uncertain positions in the key when authentication is tried for the first time after enrollment.

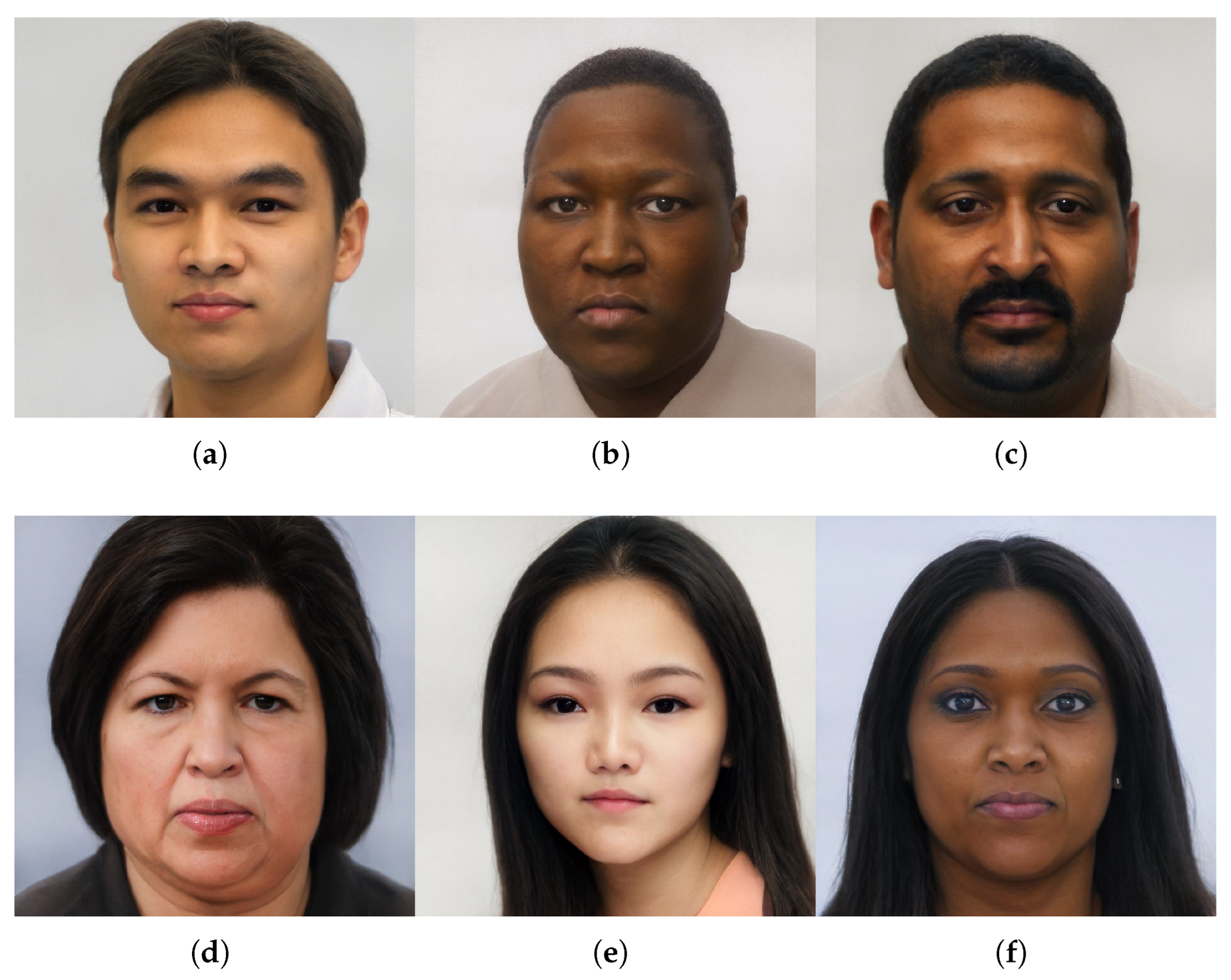

Testing was conducted on devices featuring Intel Core i7 and i9 processors, equipped with 16GB and 32GB RAM respectively and 1TB SSDs, enabling thorough protocol validation across high performance platforms with robust computational and graphics support. The facial frames used for testing are AI-generated images representing diverse genders, age groups, and ethnic backgrounds, as depicted in the

Figure 12.

These results are generated by extensive testing, spanning 100,000 authentication keys generated at a 10.5% error tolerance with 20 facial frames demonstrate that the proportion of uncertain bits per authentication event is typically within the 0-10.5% range, with the highest likelihood concentrated between 0.5% and 3% uncertainty with a stable background and no other factors intervening, as depicted in

Figure 11. These uncertainties primarily stem from challenging real-world conditions and increase, as variations in lighting, facial pose, expression, or imaging quality changes.

To effectively manage these uncertainties, the protocol incorporates an exhaustive error correction process (

Section 3.2.3) that reliably resolves errors, enabling robust ephemeral key recovery even under adverse circumstances. Notably, increasing the error tolerance threshold to 15.5% with the same number of frames significantly increases the tolerance of error rates exceeding 7.5%. As the threshold is raised, the overall ability to tolerate bit error frequency increases, further enhancing both the reliability and user convenience of the system.

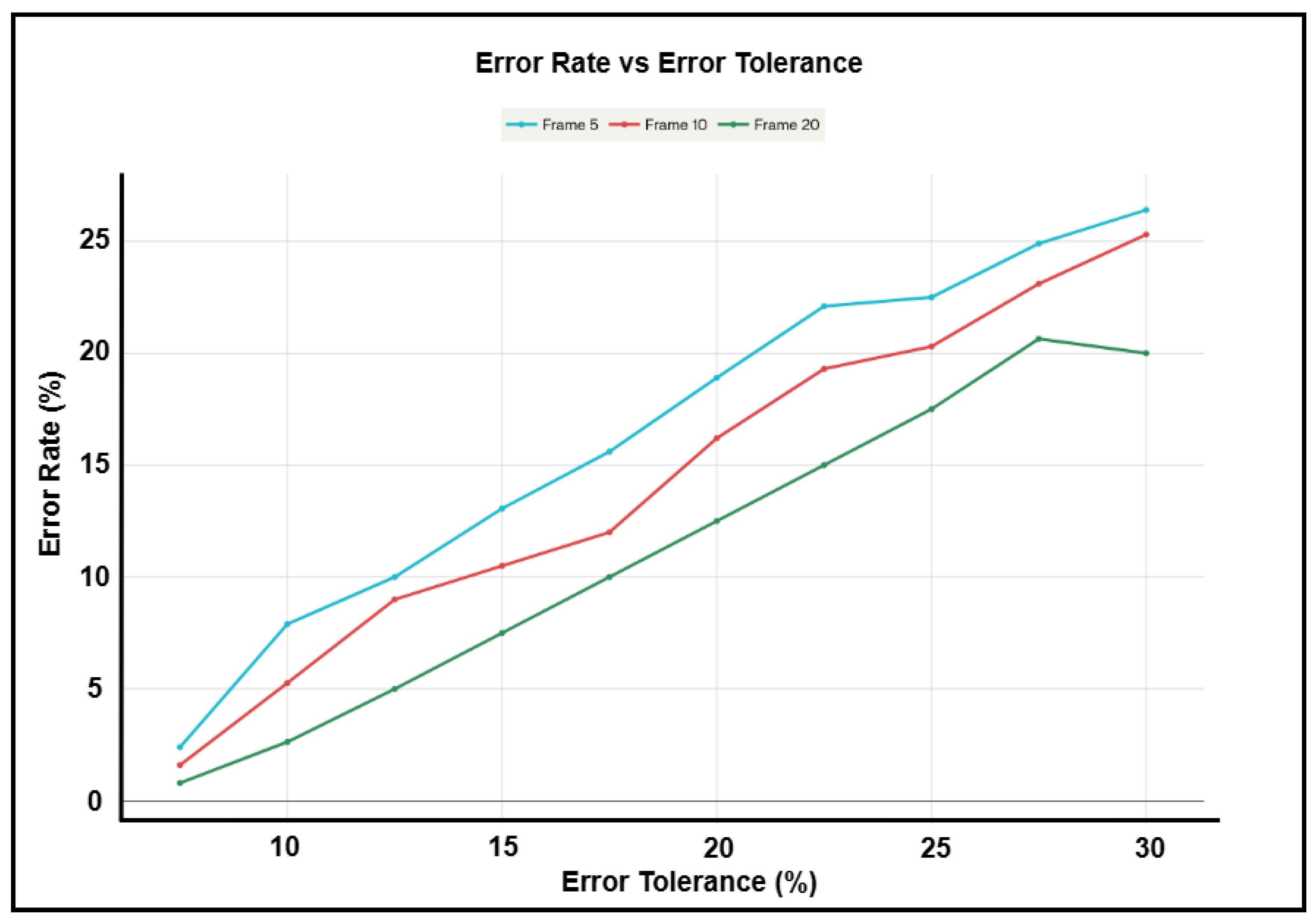

Figure 13 illustrates how average error rates vary with error tolerance for systems using 5, 10, and 20 frames. As the error tolerance increases from 7.5% to 37.5%, all systems show an increased capacity to handle error, with those utilizing more frames (like 20) consistently achieving better accuracy than those with fewer frames. This evaluation was performed without adding noise or applying gray code bit selection. For the 20-frame system, the error rate starts at roughly 0.8% with a 7.5% tolerance, rises to 3% at 10.5% tolerance, and approaches 8% at 15.5% tolerance. These error rate values are measured up to the point where the system starts to exhibit increased rates of false rejection or false acceptance at higher threshold values. These results indicate that lower tolerance settings demand greater precision, which increases authentication stringency.

The system demonstrates its most reliable expression-based authentication performance within the 7.5% to 12.5% tolerance range, making it well-suited for stable, controlled environments such as secure or military zones. In contrast, increasing error tolerance allows the system to remain effective in more variable and uncontrolled environments. Higher frame counts enhance enrollment and authentication robustness; 20 frames are ideal for high-security uses, while 10 frames strike a good balance for general applications. The data presented are based on AI-generated images incorporating diverse races and genders; however, some variation is observed when tested with real human subjects under natural conditions.

When the protocol is extended to MFA scenarios using SRAM PUF, testing over 300 enrollment cycles at a 12.5% error tolerance and 20 frames consistently yields an error rate between 0% and 2.9% per authentication event. In instances where minor uncertainties remain, the integrated error management routines resolve these efficiently, ensuring a seamless and reliable user experience.

Compared to conventional systems, which often struggle with high error rates under increased key lengths, landmark counts, or noisy deployment conditions, our protocol stands out delivering high error resilience, dynamic adaptability, and consistent user satisfaction. This foundational reliability is a critical factor that both differentiates our approach and ensures its suitability for deployment in diverse real-world security scenarios.

4.3. FAR and FRR

False Acceptance Rate (FAR) measures the likelihood that an unauthorized user is incorrectly accepted as legitimate by the biometric system, while False Rejection Rate (FRR) measures the probability that a genuine user is incorrectly rejected. When evaluated using images generated and authenticated in controlled, consistent conditions, without any background, expression, lighting, or presentation variations, FAR and FRR offer a clear baseline of system accuracy under ideal circumstances.

2D Biometric Analysis:

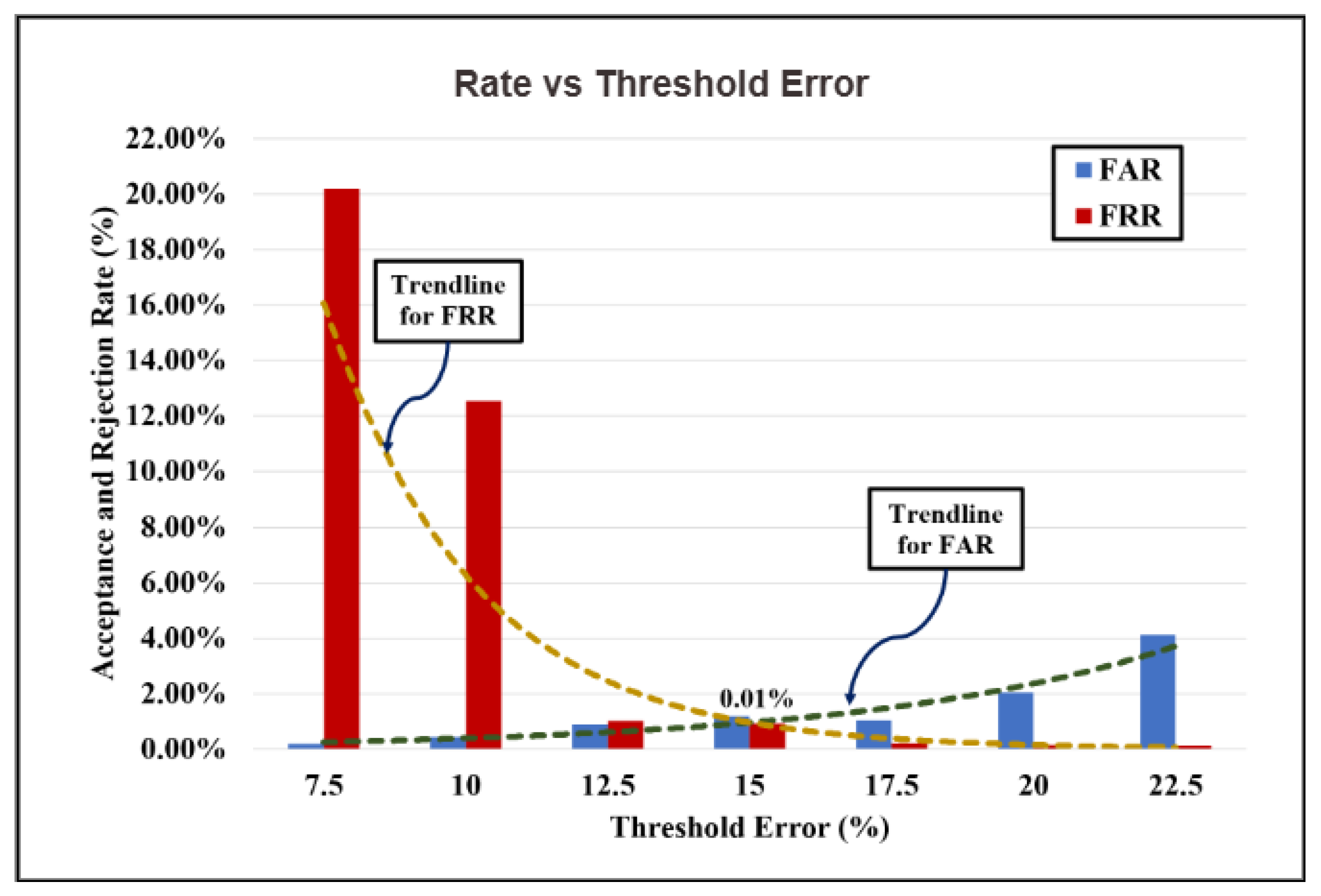

Figure 14 shows the baseline FAR and FRR for different error threshold percentages under controlled, no-variation conditions. The FRR starts high at low error thresholds (e.g., 20.17% at 7.5%) and decreases sharply as the threshold increases, while FAR remains very low across all thresholds but rises slightly at higher tolerances. At strict thresholds, the system tends to be overly conservative, resulting in a higher rejection rate even for legitimate users. With increasing error tolerance, genuine users are more readily accepted since higher number of errors can be corrected using the error correction method, but the system also becomes more permissive, causing a gradual increase in false acceptances. Notably, at a 15% error threshold, both FAR and FRR converge near zero, indicating an ideal operating point where the system achieves high security and usability under invariant conditions. The intersection and trends of these rates reflect the classic trade-off in biometric security as tightening the threshold reduces the risk of false acceptance but increases inconvenience to legitimate users, whereas loosening it enhances user convenience but slightly elevates the risk of false acceptance.

Impact of Noise Injection:

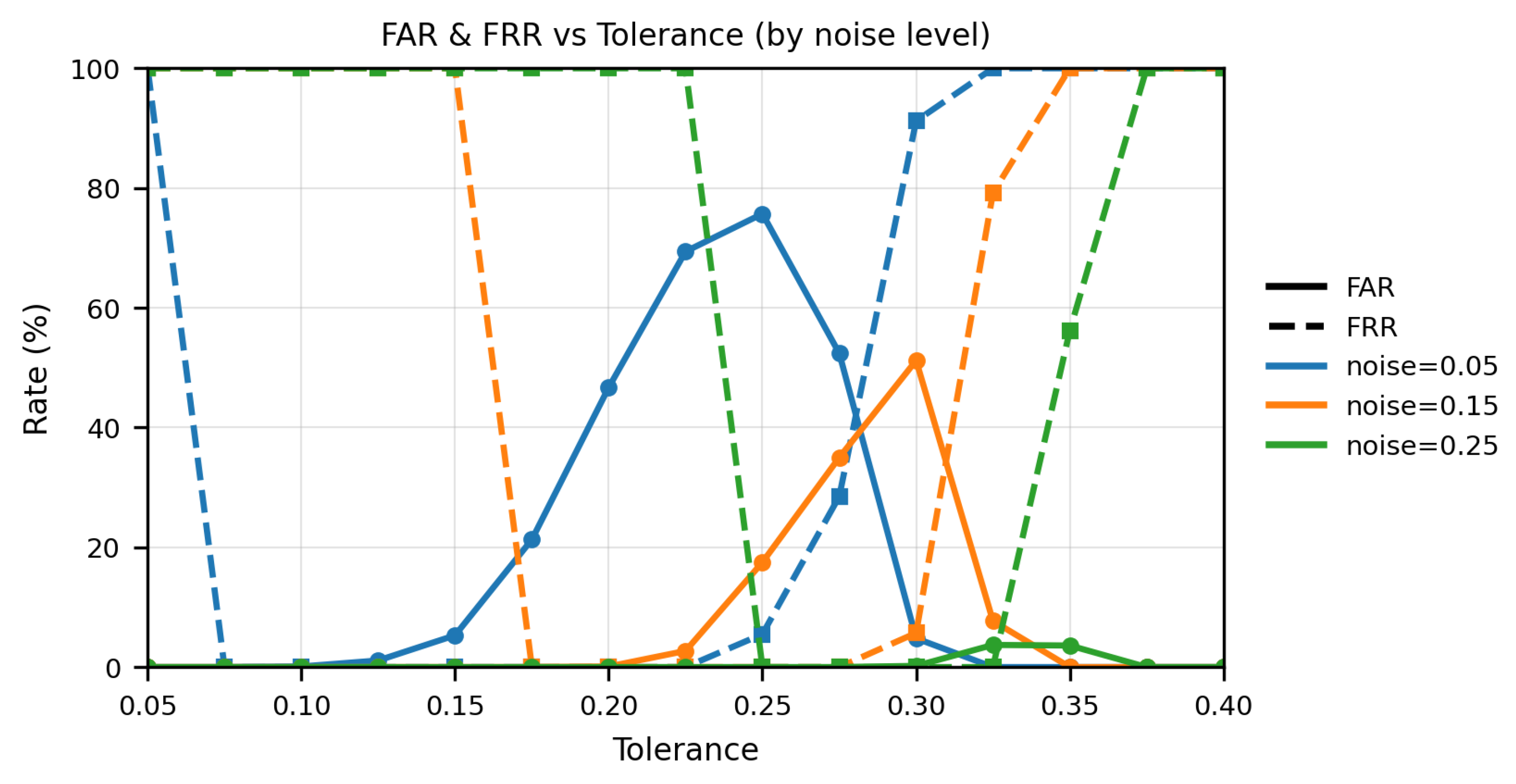

Figure 15 presents the relationship between the FAR, FRR, and error tolerance for three different noise levels: 0.05%, 0.15%, and 0.25%. Across all noise levels, as tolerance increases, there is a consistent trend where FRR sharply decreases while FAR increases. At the highest noise level (0.25) shown in the graph, the system still achieves near-zero error across a practical range of tolerances, with the minimum FAR and FRR is observed between error tolerance of 0.25 and 0.395 i.e., 25% to 39.5%. The error rate (ER) varies with noise severity: for noise = 0.05, ER is approximately 29.3% at a tolerance of 0.280; for noise = 0.15, ER is about 50.2% at a tolerance of 0.300; and for noise = 0.25, ER drops to roughly 0.63% at a tolerance of 0.245. Notably, the performance envelope reveals that near to zero FAR can be reached at a tolerance of 0.395, and zero FRR at 0.340, with the best operating point near 0.355 tolerance where the average error is about 0.05%. At higher noise (0.30 and 0.35), the trend diverges: at 0.30 the curves still admit a low-error operating band in the same tolerance region, whereas at 0.35 the FRR remains high across most tolerances, driving the ER up and leaving little practical room for operation. These findings confirm that by carefully adjusting the tolerance, the system can be tuned such that FAR approaches zero while FRR is simultaneously minimized, maintaining robust performance even under significant noise conditions.

Impact of Noise Injection and Selective Gray Code Bit Extraction:

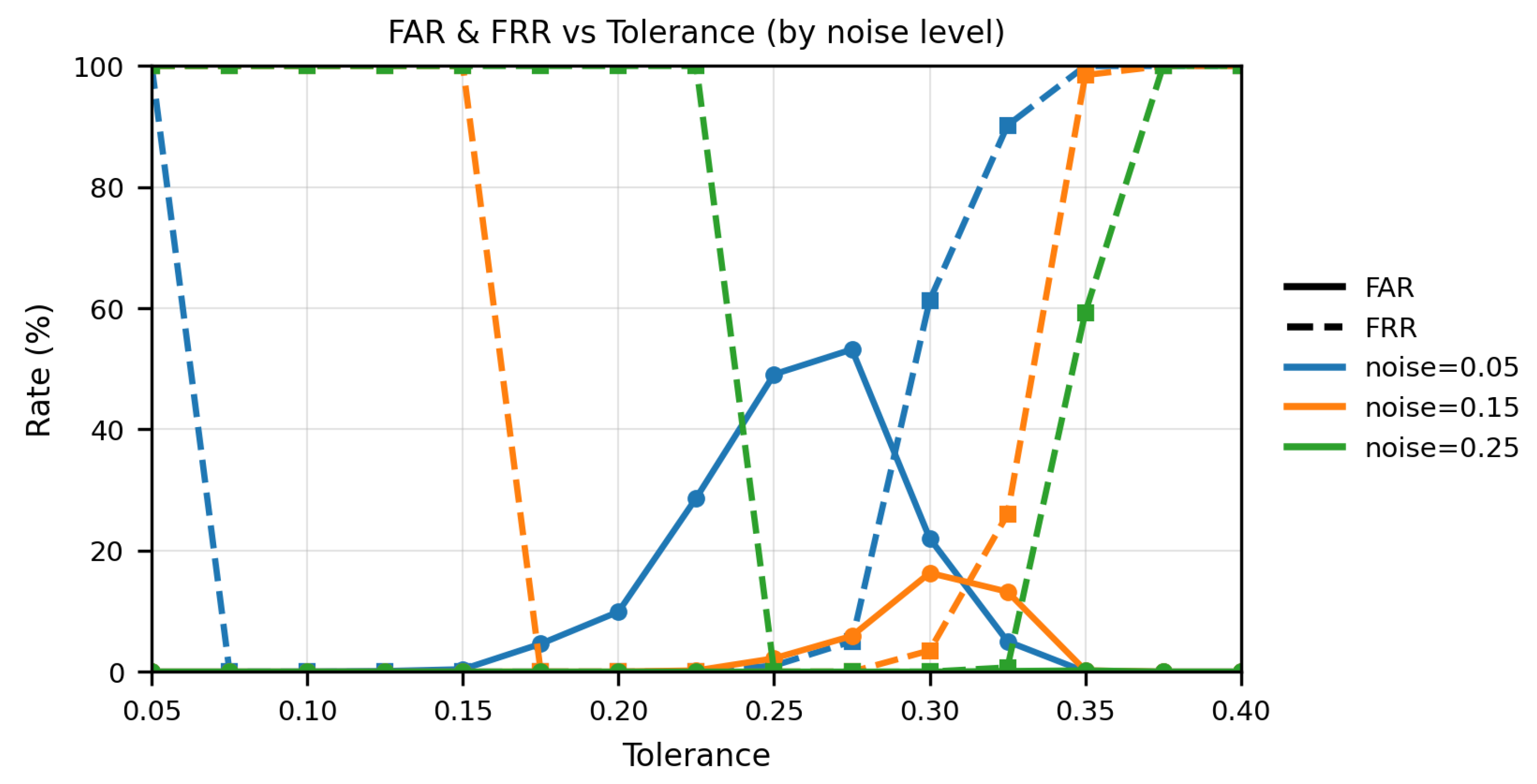

Figure 16 illustrate the impact of combining noise with the security feature of selectively removing bits in the gray coding method, as shown in the attached graph. The performance curves for all three noise levels (0.05, 0.15, 0.25) collapse near the origin i.e., both FAR and FRR reach

at low tolerance values and remain at or near zero across a practical tolerance range. The ER for each noise condition is also essentially

, occurring at tolerances around 0.075 for noise 0.05, 0.175 for noise 0.15, and 0.250 for noise 0.25. Extending to stronger noise (0.30 and 0.35), the selective bit strategy keeps FAR and FRR essentially at zero around low tolerances for 0.30, while at 0.35 the curves flatten with FAR near zero and FRR near saturation, so the ER is dominated by rejections. In essence, by integrating noise with selective gray code bit removal, the protocol achieves a broad region of negligible error, significantly enhancing both security and usability even in the presence of noise.

3D Biometric Analysis:

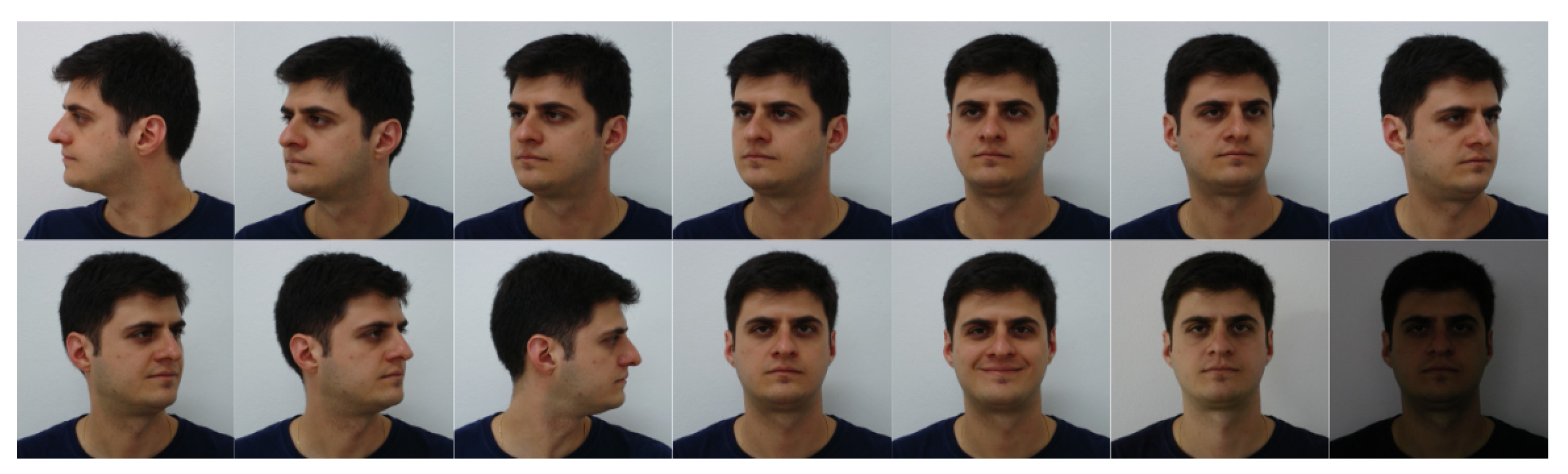

The verification performance of the proposed 3D biometric protocol was systematically evaluated through experiments using the FEI Face Database [

35]. This dataset includes images of 200 participants captured in upright poses with yaw rotations up to

and ∼10% scale variation, ages 19–40 (

Figure 17). The system’s accuracy was assessed at two key error tolerance thresholds, 7.5% and 12.5%. At 7.5% tolerance, the observed FAR was 4.25% and the FRR was 6.74%. When the tolerance was increased to 12.5%, FAR dropped sharply to 0.46% while FRR decreased to 2.75%. This concurrent reduction occurs because subset gating compares only the most stable, informative bits and ignores uncertain regions, which keeps genuine users patterns within a few bits of the enrolled reference while leaving impostor patterns much farther away. When the tolerance is relaxed slightly many near-miss genuine attempts succeed, lowering FRR. Impostors do not gain the same advantage because the bits that could help them are masked, and the comparison is anchored on stable features. This reduces accidental overlaps and lowers FAR at the same time. Accordingly, the 12.5% tolerance is selected as the operating point for the remainder of the study. It provides a balanced trade-off between security and usability under the multi-view protocol, reducing false decisions without conferring advantage to impostors.

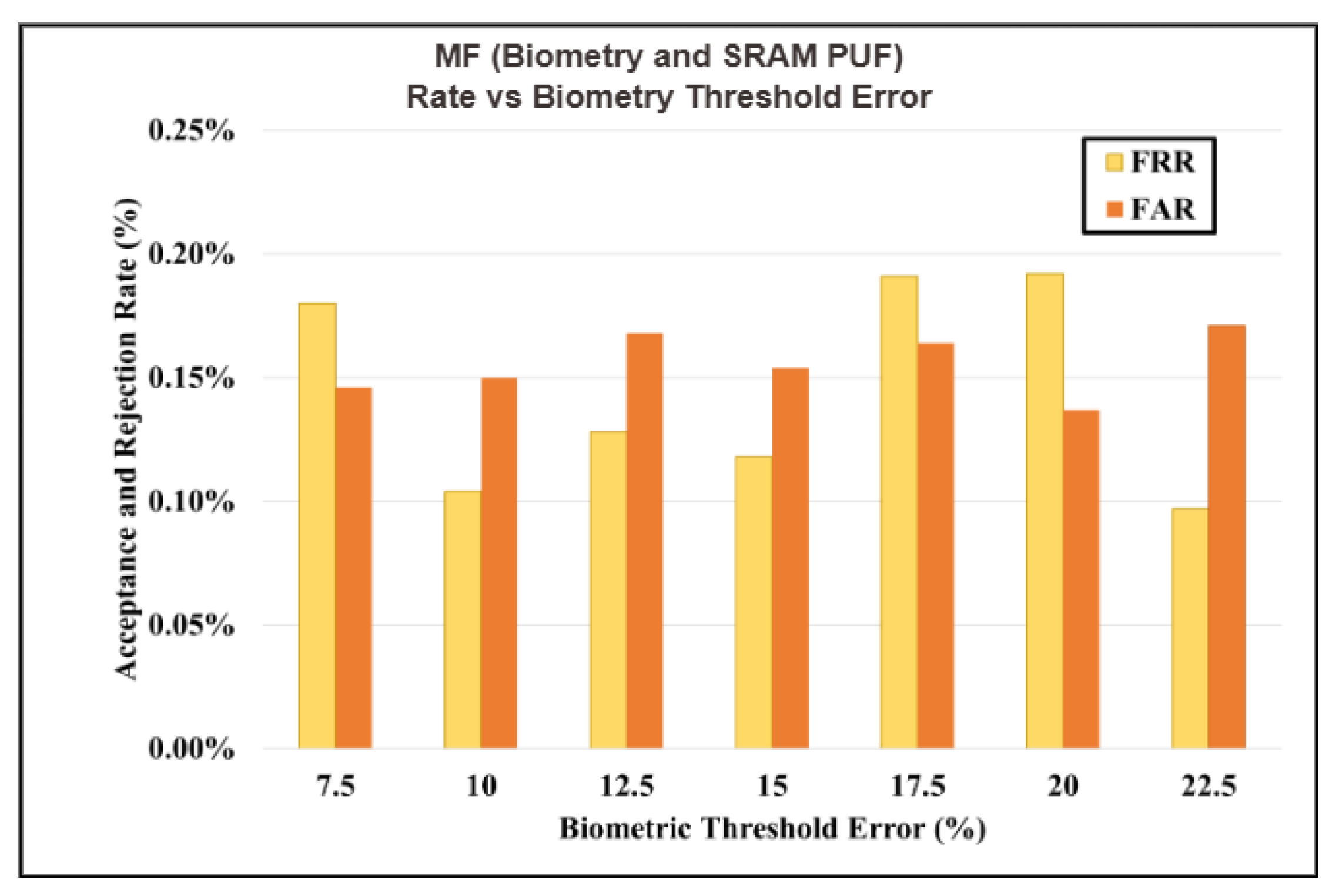

MFA with Biometry and SRAM PUF

When the 2D and 3D biometric protocol was applied using an SRAM token in a MFA setup, with data collected from 100 separate enrollment attempts. The FAR and FRR both dropped to nearly 0% as shown in

Figure 18. This performance can be attributed to the analysis of SRAM PUF, which has been shown in prior research [

30] to inherently produce very low FAR and FRR values. Our experiments with the same type of SRAM chip and biometric data confirmed these findings, as any observed errors primarily originated from the biometric component, not the SRAM. As a result, the system configuration described here represents an ideal case for authentication, demonstrating that combining strong biometric methods with robust hardware tokens like SRAM can yield extremely secure and reliable user verification when tested under controlled and uncontrolled conditions.

4.4. Latency

Latency is the time delay between starting and completing a cryptographic operation. Minimizing latency is essential for real-time decision-making and secure, efficient data handling, allowing for swift responses to security threats while maintaining data integrity.

When utilizing biometry data for generating keys from facial data, the latency is approximately 1.361 seconds. This latency increases during key generation as multiple frames are required to produce subsets of responses. Conversely, authentication latency is around 0.860 milliseconds when no uncertain positions are identified, and it extends from 0.860 seconds and 2.916 seconds when two or more uncertain positions are detected.

With MFA, combining facial characteristics and SRAM PUF for the authentication process, key generation requires approximately 1.429 seconds, while key recovery takes around 2.966 seconds.

5. Real-Time Use-Cases

Both 2D and 3D biometric recognition present unique strengths that enable deployment across a wide array of real-world applications. 2D facial recognition remains advantageous where speed, low computational overhead, and seamless user experience are paramount. Examples include mobile device authentication, workplace access control, and secure payment systems, particularly in settings with controllable lighting and posture. 3D biometric recognition, by contrast, exhibits superior robustness to variations in angle, lighting, and user expression. This makes it uniquely suited for high-security and mission-critical applications, such as automated border control gates, immigration and customs screening, law enforcement identity verification, and aerospace facility access environments where resistance to sophisticated spoofing (including deepfakes) and high-accuracy matching are indispensable.

Emerging use cases further leverage the strengths of 3D modalities, such as expression-based authentication, where dynamic facial movements add a temporal dimension to security and enhance resilience against static spoofing attempts. The incorporation of SRAM PUF-based MFA introduces an additional possession factor, binding cryptographically unique hardware signatures to each authentication event, thereby strengthening defenses in distributed or high-risk infrastructures.

In healthcare, advanced 3D biometrics facilitate secure patient verification, seamless electronic health record access, and prevention of identity fraud. In finance, they underpin reliable onboarding, high-value transaction authorization, and ATM access in each case, supported by the added security of SRA-based MFA for regulatory compliance.

6. Discussion

The results of this study substantiate the working hypothesis that a post-quantum, templateless biometric authentication protocol enriched with 2D/3D facial recognition, liveness detection, and SRAM PUF-based MFA. It can deliver high-assurance, privacy-preserving identity verification without the persistent storage of sensitive biometric or cryptographic data. Our approach offers several advances when placed in context with previous studies.

First, the delineation of stable facial landmarks and multi-frame enrollment, coupled with gray code encoding and double masking, provides a marked reduction in both FAR and FRR relative to legacy template-based biometric systems [

36,

37,

38]. The joint use of gray coding, bit slicing, and tailored noise injection further expands tolerance to environmental variations enabling robust operation across diverse lighting, pose, or expression conditions that previously challenged usability and accuracy.

Second, the use of a cryptographically secure, ephemeral key created via challenge-response subset protocols and immediately deleted post verification addresses longstanding template inversion, spoofing, reverse engineering and data breach vulnerabilities that have hindered broad biometric deployment. This innovation aligns with recent calls in the field for storage-free, zero-knowledge-friendly biometric authentication suitable for high-security landscapes and emerging quantum threats.

Third, experimental evaluations confirm the protocol’s exceptional scalability. Both theoretical entropy calculations and empirical benchmarks demonstrate that by increasing the number of facial landmarks (e.g., from 68 to 468) and leveraging high-entropy grid/landmark pairs, the protocol supports quantum-resistant key lengths (256, 512, or 1024 bits and beyond) without exhaustion of the keyspace. Integration of SRAM PUF as a possession factor within the MFA framework provides a highly reliable, tamper-evident hardware anchor, with observed error rates dominated by biometric rather than the PUF component.

Furthermore, analysis across different error tolerances establishes that the protocol can be flexibly tuned: lower tolerances are ideal for controlled or secure settings, while higher tolerances enhance usability in unconstrained environments. This flexibility was confirmed by both simulated and human-subject studies, with performance largely preserved as operational settings shift.

Compared to alternative MFA and biometric schemes documented in recent literature [

6,

14,

15,

16], our method exhibits superior error resilience, heightened resistance to spoofing (including deepfake and template-inversion attacks), and eliminates the risk of static template compromise. The zero-knowledge, ephemeral keying strategy, combined with privacy-preserving enrollment and authentication, marks a significant step forward toward truly secure and user-centric identity management. The comparative analysis presented in

Table 1 further contextualizes the contributions of this work relative to recent state-of-the-art facial biometric authentication protocols.

In the broad scope, these findings suggest potential for direct application in domains such as secure device login, financial authentication, border control, and healthcare verification. The flexible parameterization further allows future adaptation to new biometric modalities and object recognition challenges, thus broadening the protocol’s real-world applicability.

7. Conclusion and Future Work

This study has introduced a novel, templateless biometric authentication protocol, robustly integrated with multi-factor authentication through SRAM PUF tokens. By eschewing the persistent storage of biometric templates and cryptographic keys, the proposed approach effectively mitigates critical vulnerabilities related to template inversion, impersonation, and large-scale database compromise. The comprehensive experimental evaluation demonstrates that the synergy of landmark stability analysis, gray-code encoding, noise injection, and advanced error correction achieves exceptionally low false acceptance and rejection rates, while maintaining minimal latency and operational efficiency, making the protocol well-suited for deployment in smart devices, IoT infrastructure, and distributed environments.

Looking forward, the research lays foundational groundwork for extending the subset response methodology to object identification technologies. Such advancements could enable the detection and analysis of objects of interest from space, potentially benefiting fields such as environmental monitoring, national security, and disaster management.

8. Patents

1. Cambou BF, Herlihy M, Tamassia R, Toussaint K, KRISHNA K, inventors; Northern Arizona University, Brown University, assignee. Protocols for protecting digital files. United States patent application US 19/064,331. 2025 Aug 28. [

18]

2. Cambou BF, Garrett ML, Partridge M, Ghanaimiandoab D, inventors; Northern Arizona University, assignee. Protocols with noisy response-based cryptographic subkeys. United States patent application US 18/885,226. 2025 May 22. [

21]

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and S.J.; methodology, B.C. and S.J.; software, S.J., A.B., M.C. and D.G.M; validation, S.J., A.B., M.C. and D.G.M; formal analysis,S.J., A.B., and M.C.; investigation, S.J., A.B., and M.C.; resources, S.J., A.B., M.C. and D.G.M.; data curation, S.J., A.B., and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.; writing—review and editing, S.J., A.B., M.C. and D.G.M; visualization,S.J., A.B., M.C. and D.G.M; supervision, B.C.; project administration, B.C.; funding acquisition, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Castle Shield Holdings, LLC.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets will be made available upon request through the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out in collaboration with Northern Arizona University and Castle Shield Holdings, LLC. We would like to thank Jeffrey Roney of Castle Shield Holdings, LLC for funding this work. We gratefully acknowledge Logan Garrett and Mahafujul Alam for their critical support in protocol understanding and for providing the AI-generated datasets employed in experimentation. We also extend special thanks to Ian Burke for assistance with the SRAM hardware token. The AI dataset used for biometric protocol testing was sourced from Generated Photos (

https://generated.photos/; accessed 5 January 2025). In addition, the FEI Face Database (

https://fei.edu.br/~cet/facedatabase.html) was employed as a benchmark dataset for 3D biometric analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRP |

Challenge Response Pair |

| ECC |

Error Correction Code |

| FAR |

False Acceptance Rate |

| FRR |

False Rejection Rate |

| GANs |

Generative Adversarial Network |

| MFA |

Multi Factor Authentication |

| OTP |

One Time Password |

| PINs |

Personal Identification Number |

| PQC |

Post Quantum Cryptography |

| PUF |

Physically Unclonable Functions |

| RBC |

Response Based Cryptography |

| SRAM |

Static Random Access Memory |

| TI |

Template Inversion |

| IoT |

Internet of Thing |

| RN |

Random Number |

| PWD |

Password |

| ZKP |

Zero Knowledge Proof |

References

- Chen, S.; Pande, A.; Mohapatra, P. Sensor-assisted facial recognition: an enhanced biometric authentication system for smartphones. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th annual international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services, 2014, pp. 109–122.

- Dabbah, M.; Woo, W.; Dlay, S. Secure authentication for face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE symposium on computational intelligence in image and signal processing. IEEE; 2007; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Assam, H.; Sellahewa, H.; Jassim, S. On security of multi-factor biometric authentication. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions. IEEE; 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, I.; Mookherjee, S.; Saha, S.; Ganguli, S.; Kundu, S.; Chakravarti, D. Advanced atm system using iris scanner. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Opto-Electronics and Applied Optics (Optronix). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, D.; Ray, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Fingerprint recognition system: design & analysis. In Proceedings of the conference international conference on scientific paradigm shift in information technology & management, SPSITM; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ometov, A.; Bezzateev, S.; Mäkitalo, N.; Andreev, S.; Mikkonen, T.; Koucheryavy, Y. Multi-factor authentication: A survey. Cryptography 2018, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahmudi, A.; Ugail, H. A framework for facial age progression and regression using exemplar face templates. The visual computer 2021, 37, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insan, I.M.; Sukarno, P.; Yasirandi, R. Multi-factor authentication using a smart card and fingerprint (case study: Parking gate). Indonesia Journal on Computing (Indo-JC) 2019, 4, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karimian, N.; Guo, Z.; Tehranipoor, F.; Woodard, D.; Tehranipoor, M.; Forte, D. Secure and reliable biometric access control for resource-constrained systems and IoT. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.09710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.M.; Ratha, N.K.; Chellappa, R. Cancelable biometrics: A review. IEEE signal processing magazine 2015, 32, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bian, W.; Jie, B.; Xu, D.; Zhao, J. A complete user authentication and key agreement scheme using cancelable biometrics and PUF in multi-server environment. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 5413–5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Sadik, M.; Sabir, E. Multi-factor authentication based on multimodal biometrics (MFA-MB) for Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACS 12th International Conference of Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA). IEEE; 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lipps, C.; Herbst, J.; Schotten, H.D. How to Dance Your Passwords: A Biometric MFA-Scheme for Identification and Authentication of Individuals in IIoT Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ICCWS 2021 16th International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, 2021, p. 168.

- Pramana, M.D.; Lestyea, A.; Amiruddin, A. Development of a Secure Access Control System Based on Two-Factor Authentication Using Face Recognition and OTP SMS-Token. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS). IEEE, 2020; pp. 52–57.

- Ibrokhimov, S.; Hui, K.L.; Al-Absi, A.A.; Sain, M.; et al. Multi-factor authentication in cyber physical system: A state of art survey. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st international conference on advanced communication technology (ICACT). IEEE; 2019; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Shahreza, H.O.; Marcel, S. Template inversion attack using synthetic face images against real face recognition systems. IEEE Transactions on Biometrics, Behavior, and Identity Science 2024, 6, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambou, B.; Philabaum, C.; Hoffstein, J.; Herlihy, M. Methods to encrypt and authenticate digital files in distributed networks and zero-trust environments. Axioms 2023, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambou, B.F.; Herlihy, M.; Tamassia, R.; Toussaint, K.; KRISHNA, K. Protocols for protecting digital files, 2025. US Patent App. 19/064,331.

- Dkhil, M.B.; Wali, A.; Alimi, A.M. Towards a new system for drowsiness detection based on eye blinking and head posture estimation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.00360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanai Miandoab, D.; Garrett, M.L.; Alam, M.; Jain, S.; Assiri, S.; Cambou, B. Secure Cryptographic Key Encapsulation and Recovery Scheme in Noisy Network Conditions. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambou, B.F.; Garrett, M.L.; Partridge, M.; Ghanaimiandoab, D. Protocols with noisy response-based cryptographic subkeys, 2025. US Patent App. 18/885,226.

- Jabberi, M.; Wali, A.; Chaudhuri, B.B.; Alimi, A.M. 68 landmarks are efficient for 3D face alignment: what about more? 3D face alignment method applied to face recognition. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 41435–41469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abhishek, K.; Roshan, S.; Kumar, P.; Ranjan, R. A comprehensive study on multifactor authentication schemes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computing and Information Technology: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Advances in Computing and Information Technology (ACITY) July 13-15, 2012, Chennai, India-Volume 2. Springer, 2013, pp. 561–568.

- Ometov, A.; Petrov, V.; Bezzateev, S.; Andreev, S.; Koucheryavy, Y.; Gerla, M. Challenges of multi-factor authentication for securing advanced IoT applications. IEEE Network 2019, 33, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, J. Multifactor authentication: Its time has come. Technology Innovation Management Review 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambou, B.; Gowanlock, M.; Heynssens, J.; Jain, S.; Booher, D.; Burke, I.; Garrard, J.; Philabaum, C. Blockchain Technology with Ternary Cryptography. Technical report, Northern Arizona University Flagstaff United States, 2020.

- Cambou, B.; Gowanlock, M.; Heynssens, J.; Jain, S.; Philabaum, C.; Booher, D.; Burke, I.; Garrard, J.; Telesca, D.; Njilla, L. Securing additive manufacturing with blockchains and distributed physically unclonable functions. Cryptography 2020, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Korenda, A.R.; Cambou, B.; Lucero, C. Secure Content Protection Schemes for Industrial IoT with SRAM PUF-Based One-Time Use Cryptographic Keys. In Proceedings of the Science and Information Conference. Springer; 2024; pp. 478–498. [Google Scholar]

- Cambou, B.F.; Jain, S. Key Recovery for Content Protection Using Ternary PUFs Designed with Pre-Formed ReRAM. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Korenda, A.R.; Bagri, A.; Cambou, B.; Lucero, C.D. Strengthening industrial IoT security with integrated puf token. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference. Springer, 2024, pp. 99–123.

- Jain, S.; Korenda, A.R.; Cambou, B. A Novel Approach to Optimize Response-Based Cryptography for Secure. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference (FTC) 2024, Volume 4. Springer Nature, 2024, Vol. 1157, p. 226.

- Jain, S. Secure and Reliable Zero-Knowledge Proof Cryptographic Systems for Real-World Applications. PhD thesis, Northern Arizona University, 2024.

- Partridge, M.; Jain, S.; Garrett, M.; Cambou, B. Post-quantum cryptographic key distribution for autonomous systems operating in contested areas. In Proceedings of the Autonomous Systems: Sensors, Processing and Security for Ground, Air, Sea, and Space Vehicles and Infrastructure 2023. SPIE, 2023, Vol. 12540; pp. 126–138.

- Cambou, B.; Philabaum, C.; Booher, D.; Telesca, D.A. Response-based cryptographic methods with ternary physical unclonable functions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Information and Communication: Proceedings of the 2019 Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Volume 2. Springer, 2020, pp. 781–800.

- Thomaz, C.E. FEI face database. FEI Face DatabaseAvailable 2012, 11, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, L.; Kamara, S.; Reiter, M.K. The Practical Subtleties of Biometric Key Generation. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium; 2008; pp. 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wati, V.; Kusrini, K.; Al Fatta, H.; Kapoor, N. Security of facial biometric authentication for attendance system. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 23625–23646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chandran, V. Biometric based cryptographic key generation from faces. In Proceedings of the 9th biennial conference of the Australian pattern recognition society on digital image computing techniques and applications (DICTA 2007). IEEE; 2007; pp. 394–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rathgeb, C.; Merkle, J.; Scholz, J.; Tams, B.; Nesterowicz, V. Deep face fuzzy vault: Implementation and performance. Computers & Security 2022, 113, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, A.; Umer, S.; Rout, R.K.; Sahoo, K.S.; Gandomi, A.H. Enhanced biometric template protection schemes for securing face recognition in IoT environment. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 23196–23206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddeti, V.N. Secure face matching using fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th international conference on biometrics theory, applications and systems (BTAS). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).