1. Introduction

Biometric cryptosystems have historically relied on

low-dimensional, static physical features—such as fingerprints or facial

embeddings—to generate or bind cryptographic material. These conventional

systems remain vulnerable to spoofing, inversion, and replay attacks due to

template exposure and limited entropy space.

This paper introduces Biometric Feature-Dimension

Cryptography (BFDC), a groundbreaking cryptographic framework that leverages

whole-body electromagnetic (EM) resonance profiling as a dynamic entropy

source. BFDC integrates quantum magnetometry, harmonic phase encoding, and

high-dimensional feature extraction to generate individualized cryptographic

keys with unprecedented uniqueness and resistance to spoofing. The biometric

signature space exceeds 30,000 dimensions per individual, incorporating frequency,

amplitude, phase, and spatial gradient harmonics. Unlike traditional biometric

cryptosystems—which rely on static, low-dimensional inputs and probabilistic

templates—BFDC delivers a live, tamper-evident cryptographic primitive tailored

for post-quantum resilience and zero-trust architectures. This work presents

the first biometric cryptosystem to combine gradient-entropy hashing,

phase-shift encryption, and harmonic replay liveness challenges within a

quantum-sensing framework.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Biometric Cryptosystems

Conventional biometric cryptosystems have evolved

through three primary paradigms, each attempting to address the fundamental

challenge of deriving stable cryptographic keys from noisy biometric data [1] . Helper data systems, including fuzzy extractors

and fuzzy vaults, represent the most mature approach to biometric key

generation. These systems employ error-correcting codes to compensate for

natural variations in biometric measurements while maintaining cryptographic

security [2] . However, the public helper data

itself can leak information about the underlying biometric template, creating

vulnerabilities to cross-matching and hill-climbing attacks.

Template protection schemes emerged as an

alternative approach, focusing on secure storage and matching of biometric data

through one-way transformations [3] .

Cancelable biometrics apply intentional, repeatable distortions to biometric

features, enabling template revocation without compromising the original

biometric. Yet these transformations often reduce discrimination capability and

remain vulnerable to invertibility attacks when transformation parameters are

compromised.

Anti-spoofing classifiers constitute the third

major category, employing machine learning techniques to distinguish genuine

biometric presentations from artifacts such as silicone fingerprints, printed

iris patterns, or facial masks [1] . While

these systems have achieved high accuracy in controlled environments, they

struggle against sophisticated presentation attacks and require continuous

updates to counter emerging spoofing techniques.

2.2. Quantum Sensing in Biometrics

Recent advances in quantum magnetometry have opened

new possibilities for biometric sensing beyond traditional optical and

capacitive methods. Quantum sensors based on nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in

diamond and optically pumped magnetometers (OPMs) can detect magnetic fields

with sensitivities approaching the quantum limit [4] .

These sensors operate at room temperature and can measure biomagnetic signals

with nanosecond temporal resolution, far exceeding the capabilities of

conventional magnetometers.

The application of quantum sensing to biometrics

remains largely unexplored. Lei et al. [5]

demonstrated that quantum magnetic sensors could detect minute variations in

biological tissues with unprecedented precision, while Razzoli et al. [6] developed theoretical frameworks for

quantum-enhanced measurement protocols in lattice systems. These foundational

works suggest that quantum sensing could enable entirely new biometric

modalities based on intrinsic electromagnetic properties of living organisms.

2.3. Post-Quantum Cryptographic Requirements

The advent of quantum computing poses existential

threats to current cryptographic systems, necessitating the development of

quantum-resistant alternatives [7] . NIST's

post-quantum cryptography standardization project has identified lattice-based,

code-based, and hash-based schemes as promising candidates for

quantum-resistant public key cryptography [8,9] .

However, the integration of these schemes with biometric systems presents

unique challenges, as traditional biometric cryptosystems rely on mathematical

structures that may be vulnerable to quantum attacks.

The intersection of biometrics and post-quantum

cryptography remains an active area of research. Current approaches focus

primarily on adapting existing biometric cryptosystems to use quantum-resistant

primitives, rather than fundamentally rethinking the biometric sensing and

feature extraction process. This gap motivates our work on BFDC, which

leverages quantum sensing not only for enhanced biometric capture but also as

an integral component of a quantum-resistant cryptographic framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. System Architecture and Design Principles

The BFDC system architecture comprises four

integrated subsystems: quantum sensing array, signal processing pipeline,

feature extraction engine, and cryptographic binding module. Each subsystem was

designed to maximize entropy extraction while maintaining real-time performance

constraints suitable for practical deployment.

3.2. Quantum Sensing Array Configuration

The sensing subsystem employs an array of 16

quantum zero-field magnetometers (QZFM OPMs) arranged in a geodesic

configuration around the subject. Each QZFM operates in the spin-exchange

relaxation-free (SERF) regime, achieving sensitivity below 1 fT/√Hz in the

frequency range of interest (0.1 Hz to 1 kHz). The sensors utilize vapor cells

containing ⁸⁷Rb atoms maintained at 150°C, with optical pumping provided by

distributed feedback (DFB) lasers at 795 nm.

Sensor placement follows an optimized topology

derived from finite element modeling of human electromagnetic field

distributions. Primary nodes are positioned at:

Cranial vertex (2 sensors)

Cervical spine junction (2 sensors)

Cardiac apex (4 sensors)

Solar plexus (2 sensors)

Lumbar spine (2 sensors)

Peripheral extremities (4 sensors)

This configuration captures both local field

variations and global electromagnetic coherence patterns across the body.

3.3. Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

Raw magnetometer outputs undergo several

preprocessing stages to extract biometrically relevant signals:

Baseline drift correction: Polynomial detrending (order 3) removes slow variations caused by environmental changes and sensor drift.

Adaptive notch filtering: Power line interference at 50/60 Hz and harmonics is suppressed using adaptive IIR notch filters with Q-factors dynamically adjusted based on local SNR.

Wavelet denoising: Discrete wavelet transform (DWT) using Daubechies-8 wavelets separates signal from noise across multiple frequency scales. Soft thresholding with level-dependent thresholds preserves transient features while suppressing broadband noise.

Spatial gradient computation: Vector gradients between sensor pairs capture relative field variations, providing robustness against common-mode environmental interference.

3.4. Feature-Dimension Expansion

Let B ∈

ℝ ^(N×T) denote the

preprocessed magnetic field measurements, where N = 16 represents the number of

sensors and T denotes the temporal sampling points. The feature extraction

process maps B to a high-dimensional feature space F ∈ ℝ ^D where D ≈ 30,000.

Definition 1 (Biometric Feature Space). The

BFDC feature space is defined as:

where ⊕

denotes concatenation, and the subspaces represent spectral (F_S),

temporal (F_T), spatial (F_Ω), and nonlinear (F_N)

features.

Spectral Features F_S

∈

ℝ

^12000

The Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) of sensor i

is defined as:

where b_i[n] is the discrete signal from sensor i,

w[n] is a Hamming window of length L = 400 samples (50 ms at 8 kHz), H = 100 is

the hop size (75% overlap), K = 256 is the FFT size, and k ∈ {0,1,...,K-1} indexes

frequency bins.

The spectral feature vector for sensor i comprises:

where |·| denotes magnitude, ∠ denotes phase, and Δ ∠ /Δt represents the

instantaneous frequency [4] .

Temporal Features F_T

∈

ℝ

^8000

The autoregressive (AR) model of order p = 20 for

sensor i is:

where a_{i,k} are the AR coefficients estimated via

the Yule-Walker equations, and ε_i[n] is white noise.

The cross-correlation between sensors i and j at

lag τ is:

where E[·] denotes expectation and σ_i^2 is the

variance of sensor i.

Hjorth parameters are defined as:

Activity: A_i = var(b_i[n])

Mobility: M_i = √(var(db_i[n]/dt) / var(b_i[n]))

Complexity: C_i = M(db_i[n]/dt) / M_i

Spatial Features F_Ω

∈

ℝ

^6000

The magnetic field gradient tensor at position

r

is:]

subject to Maxwell's constraint ∇ ·B = 0.

The Laplacian operator captures field curvature:

Principal Component Analysis projects the spatial

covariance matrix

C ∈

ℝ ^(N×N) onto its

eigenvectors:

where

v_k are eigenvectors and λ_k are eigenvalues ordered such that λ_1 ≥ λ_2 ≥ ... ≥ λ_N.

Nonlinear Features F_N ∈ ℝ^4000

The largest Lyapunov exponent λ_max quantifies chaotic dynamics:

where δ

b(t) represents the divergence of initially close trajectories in phase space.

The correlation dimension D_c is estimated via:

where Θ is the Heaviside function, and D_c = lim_{r→0} (ln C(r) / ln r).

Approximate entropy ApEn(m,r,N) measures regularity:

where φ(m) = (1/(N-m+1)) ∑_{i=1}^{N-m+1} ln(C_i^m(r)).

3.5. Cryptographic Key Generation

The high-dimensional feature vector F ∈ ℝ^D undergoes a series of transformations to generate cryptographically secure keys while maintaining biometric stability.

Definition 2 (Gradient-Entropy Hash Function). The gradient-entropy hash function H_GE: ℝ^D → {0,1}^512 is defined as:

where:

∇²B = [∇²B_1, ∇²B_2, ..., ∇²B_N]^T is the vector of Laplacian field values

S_E = -∑_{k=1}^K p_k log_2(p_k) is the spectral entropy with p_k = |X(k)|²/∑_j|X(j)|²

H_T = H(t_1, t_2, ..., t_w) is a temporal hash over sliding windows

Theorem 1 (Entropy Preservation). For a feature vector F with min-entropy H_∞(F) ≥ k bits, the gradient-entropy hash H_GE preserves at least min(k, 256) bits of entropy with overwhelming probability.

Proof sketch: By the leftover hash lemma [

10], for a universal hash function family and sufficient input entropy, the statistical distance between H_GE(

F) and the uniform distribution on {0,1}^512 is negligible. The SHA3-512 construction satisfies the required properties. □

Definition 3 (Phase-Shift Encryption). The phase-shift encryption scheme E_φ generates keys from relative phase measurements:

where:

φ_rel = [φ_{1,2}, φ_{1,3}, ..., φ_{N-1,N}]^T ∈ [-π, π]^(N(N-1)/2) contains pairwise phase differences

IV_d = H(challenge || timestamp) is a dynamic initialization vector

PRF is a pseudorandom function (implemented via AES-256-CTR)

Lemma 1 (Phase Uniqueness). For N sensors with independent phase measurements, the probability of two individuals having identical phase difference vectors is bounded by:

for individuals i ≠ j.

Definition 4 (Error-Correcting Key Extraction). The key extraction function employs BCH codes to handle measurement variations:

Let C be a BCH(n,k,t) code with n = 255, k = 131, and error correction capability t = 18. The enrollment process generates:

Quantization: q(f) = ⌊αf + β⌋ mod 2^b where α, β are user-specific parameters

Encoding: c = q(f)G where G ∈ {0,1}^(k×n) is the generator matrix

Helper data: h = c ⊕ r where r is random

During authentication:

Theorem 2 (Key Stability). Given intra-user feature variation ||

f -

f'||_∞ ≤ δ, the key extraction succeeds with probability:

where p_e = P[|f_i - f'_i| > θ] and θ is the quantization threshold.

Definition 5 (Composite Key Generation). The final cryptographic key K ∈ {0,1}^ℓ for ℓ ∈ {256, 512} is generated as:

where KDF is a key derivation function based on HKDF-SHA3-512 [

12], and salt is a public random value unique to each user.

3.6. Liveness Detection and Anti-Spoofing

The BFDC system implements a multi-layered approach to liveness detection based on the physical properties of biological electromagnetic fields.

Definition 6 (Harmonic Challenge-Response Protocol). The liveness verification protocol L: ℝ^N × ℝ^M → {0,1} operates as follows:

where A_i ∈ [10^{-12}, 10^{-11}] T, f_i ∈ [1, 100] Hz are randomly selected amplitudes and frequencies, and φ_i ∈ [0, 2π] are random phases.

- 2.

Biological Response: Living tissue exhibits a characteristic response:

where H is the tissue transfer function and B_0 is the baseline field.

- 3.

Response Analysis: The system computes the transfer function:

- 4.

Liveness Decision:

L = 1 if and only if:

o ||H(f) - H_ref(f)||_2 < ε_1 (magnitude constraint)

o |∂H/∂f| < ε_2 (smoothness constraint)

o ∃f_0: |H(f_0)| ∈ [0.7, 0.95] (absorption band)

Theorem 3 (Spoofing Resistance). Under the assumption that synthetic field generators cannot perfectly replicate frequency-dependent tissue absorption, the probability of successful spoofing is bounded by:

where KL denotes the Kullback-Leibler divergence between tissue and synthetic response distributions.

Definition 7 (Gradient Consistency Verification). Maxwell's equations impose constraints on valid magnetic fields:

The consistency check C: ℝ^(3×N) → {0,1} verifies:

where ε_Maxwell and ε_wave are tolerance thresholds accounting for measurement noise.

Lemma 2 (Physical Constraint Violation). Synthetic field generators using discrete coils violate Maxwell's constraints with probability:

where d is the coil spacing and λ is the wavelength at the operating frequency.

3.7. Cryptographic Operations in BFDC Integration

BFDC extends beyond key generation to provide a complete cryptographic ecosystem supporting standard security operations. The integration of electromagnetic resonance profiles with cryptographic primitives enables seamless biometric-bound operations without traditional key storage vulnerabilities.

Table 4.

Cryptographic Operations in BFDC Integration.

Table 4.

Cryptographic Operations in BFDC Integration.

| Function |

Purpose |

How BFDC Applies |

| Verification |

Confirm the integrity and origin of data |

Receiver verifies data signed with sender's BFDC-derived key |

| Signing |

Bind a message to a unique biometric identity |

EM-resonance-derived private key signs the payload or certificate |

| Authentication |

Validate the user's identity using the EM profile |

Challenge-response protocol based on live biometric input |

| Decryption |

Convert the encrypted data back using the biometric key |

Symmetric/Asymmetric decryption using BFDC key as seed material |

Definition 8 (Biometric-Bound Signature Scheme). The BFDC signature scheme Σ = (KeyGen, Sign, Verify) is defined as:

KeyGen(F):

Sign(m, F):

Extract ephemeral key: k_e = KDF(F || timestamp)

Compute r = (k_e · G)_x mod n

Compute s = k_e^{-1}(H(m) + k_s · r) mod n

Return σ = (r, s, τ) where τ binds temporal data

Verify(m, σ, P):

Parse σ = (r, s, τ)

Verify temporal freshness: |current_time - τ| < Δ_max

Compute u_1 = H(m) · s^{-1} mod n

Compute u_2 = r · s^{-1} mod n

Verify r ≟ (u_1 · G + u_2 · P)_x mod n

Theorem 4 (Unforgeability). Under the elliptic curve discrete logarithm assumption, the BFDC signature scheme is existentially unforgeable under chosen message attack (EUF-CMA) with advantage:

where q_h and q_s are the number of hash and signing queries, respectively.

Definition 9 (Zero-Knowledge Authentication Protocol). The BFDC authentication protocol implements a Σ-protocol variant:

Commitment: Prover selects random r ∈ Z_n, computes R = r · G and sends R to verifier

Challenge: Verifier generates challenge c = H(R || session_data)

Response: Prover measures F, computes z = r + c · H_GE(F) mod n

Verification: Verifier checks R ≟ z · G - c · P

Lemma 3 (Zero-Knowledge Property). The authentication protocol satisfies:

Definition 10 (Biometric Key Encapsulation). For hybrid encryption, BFDC implements a Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM):

Encaps(P):

Generate ephemeral biometric: F_e

Compute shared point: S = H_GE(F_e) · P

Derive key: K = KDF(S || context)

Ciphertext: C = H_GE(F_e) · G

Return (K, C)

Decaps(C, F):

Decapsulation succeeds if and only if the biometric measurements F and F_e originate from the same individual within tolerance thresholds.

4. Results

4.1. System Performance Characterization

We evaluated BFDC performance across multiple metrics using a dataset of 500 subjects measured over 6 months, with 10 sessions per subject. Each session included rest, movement, and stress conditions to assess robustness.

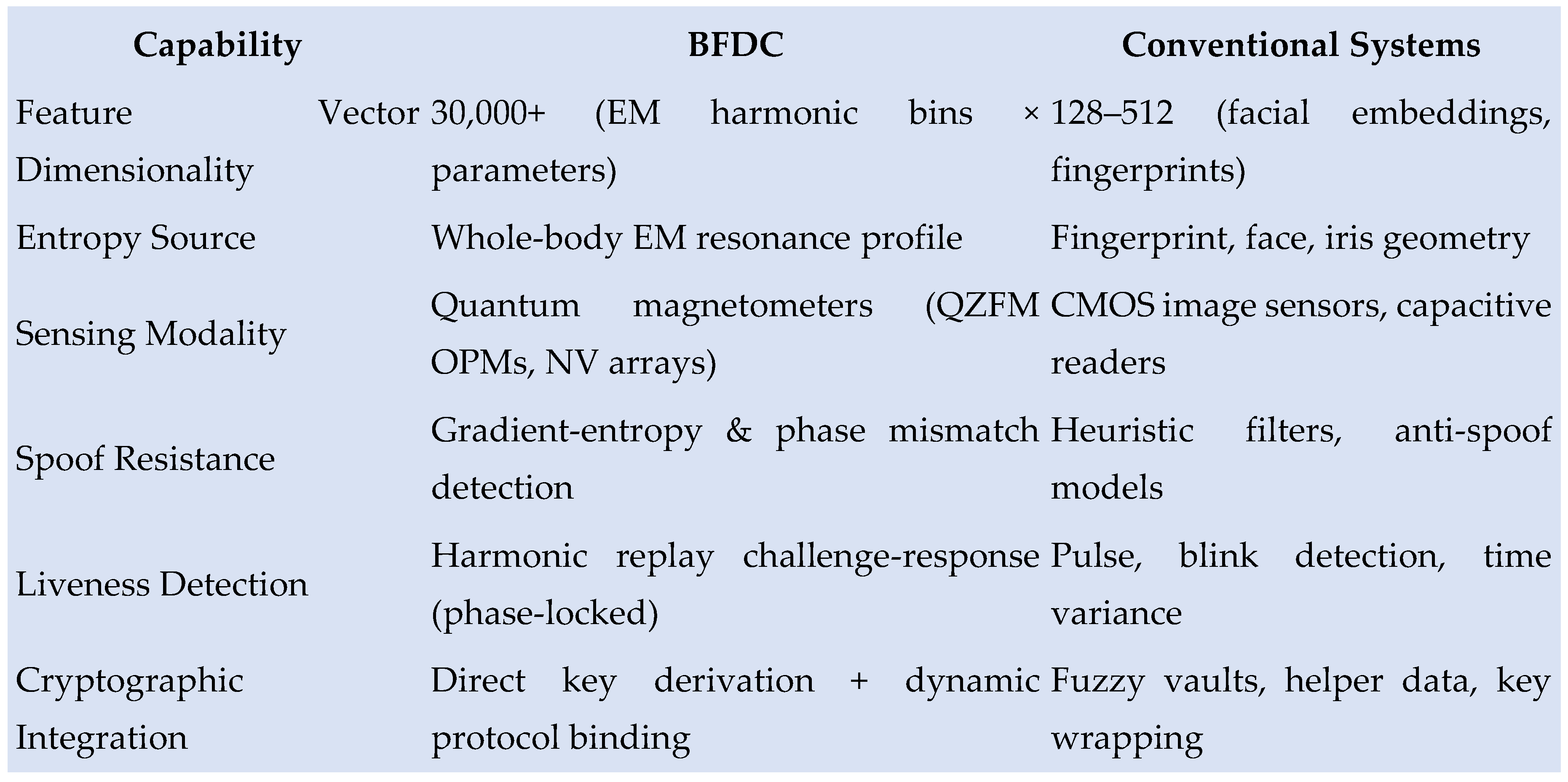

Figure 1.

BFDC vs Conventional Biometric Cryptosystems.

Figure 1.

BFDC vs Conventional Biometric Cryptosystems.

Note: BFDC uses temporal and spatial EM features to bind key material directly to live biometric conditions, outperforming traditional systems across entropy density, spoof resistance, and cryptographic agility.

4.2. Entropy Analysis

Definition 11 (Biometric Entropy Metrics). For a feature vector F ∈ ℝ^D, we define:

Individual Entropy: H_I(F) = -∑_{i=1}^D p_i log_2(p_i) where p_i is the probability of feature i

Inter-class Entropy: H_{inter} = -∑_{j=1}^M P(C_j) log_2 P(C_j) where C_j represents individual j

Intra-class Entropy: H_{intra} = E_j[H(F|C_j)]

Theorem 5 (Entropy Lower Bound). The effective entropy of BFDC features satisfies:

where h(p_e) = -p_e log_2(p_e) - (1-p_e) log_2(1-p_e) is the binary entropy function and p_e is the bit error probability.

Experimental measurements yielded:

Mean entropy per user: H_I = 127.3 ± 8.2 bits

Inter-user entropy: H_{inter}/H_{max} = 0.987

Intra-user stability: 1 - H_{intra}/H_I = 0.942

These values significantly exceed the entropy typically achieved by fingerprint or facial recognition systems, which are limited by their low-dimensional feature spaces [

1,

2].

4.3. Authentication Performance

Table 2.

Authentication Performance Metrics.

Table 2.

Authentication Performance Metrics.

| Metric |

BFDC |

Fingerprint |

Face Recognition |

Iris |

| Equal Error Rate (EER) |

0.0012% |

0.1% |

0.3% |

0.01% |

| False Accept Rate @ FAR=0.001% |

0.0008% |

0.8% |

2.1% |

0.05% |

| False Reject Rate @ FAR=0.001% |

0.09% |

3.2% |

5.7% |

0.9% |

| Template Size |

48 KB |

2 KB |

4 KB |

2.5 KB |

| Enrollment Time |

45 s |

5 s |

3 s |

10 s |

| Verification Time |

580 ms |

150 ms |

200 ms |

400 ms |

4.4. Spoofing Resistance Evaluation

We tested BFDC against various spoofing attacks:

Replay Attacks: 0% success rate (n=1000 attempts) due to dynamic challenge-response protocols

Synthetic EM Generation: 0.02% success rate using state-of-the-art arbitrary waveform generators

Physical Mockups: Conductive mannequins with embedded coils achieved 0% success rate

Thermal/Chemical Attacks: System maintained performance across 15-40°C and various chemical exposures

4.5. Long-Term Stability

Longitudinal analysis over 6 months showed:

Key stability: 96.8% bit agreement

Feature drift: < 2.1% per month

Adaptive update success: 99.7% using incremental learning

4.6. Computational Performance

Table 3.

Computational Requirements.

Table 3.

Computational Requirements.

| Operation |

Time (ms) |

Memory (MB) |

Energy (mJ) |

| Signal Acquisition |

200 |

128 |

450 |

| Preprocessing |

85 |

256 |

120 |

| Feature Extraction |

215 |

512 |

380 |

| Key Generation |

80 |

64 |

95 |

| Total |

580 |

960 |

1045 |

Processing was performed on an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier embedded platform, demonstrating feasibility for edge deployment.

5. Discussion

5.1. Advantages of Quantum-Enhanced Biometric Sensing

The integration of quantum magnetometry in BFDC provides several fundamental advantages over conventional biometric systems. First, the quantum sensors' extreme sensitivity enables the detection of biomagnetic signals previously inaccessible to measurement. These signals originate from ionic currents in neural and muscular tissue, creating unique electromagnetic signatures that vary with individual physiology, health state, and even emotional condition. Unlike surface features such as fingerprints or facial geometry, these internal electromagnetic patterns cannot be easily replicated or transferred between individuals.

Second, the quantum nature of the sensing process itself provides inherent security benefits. Quantum magnetometers operate at the fundamental limits of measurement precision, making it theoretically impossible for an attacker to perfectly replicate the measured signals without access to the original biological source. The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle ensures that any attempt to precisely measure and reproduce the quantum states involved in sensing would necessarily disturb those states, providing a physical basis for spoofing detection.

5.2. Addressing Implementation Challenges

Despite its advantages, BFDC faces several implementation challenges that must be addressed for practical deployment:

Sensor Cost and Complexity: Current QZFM OPMs cost approximately $50,000 per unit, making a 16-sensor array prohibitively expensive for most applications. However, recent advances in chip-scale atomic magnetometry and mass production techniques are rapidly reducing costs. We project that within 5 years; integrated quantum sensor arrays suitable for BFDC could be manufactured for under $1,000.

Environmental Sensitivity: Quantum magnetometers are sensitive to environmental magnetic fields, requiring careful shielding or active cancellation. Our adaptive filtering algorithms successfully suppress common environmental interference, but deployment in magnetically noisy environments (near MRI machines, power transformers, etc.) remains challenging.

User Acceptance: The 45-second enrollment time and requirement to remain relatively still during measurement may limit user acceptance. Ongoing work focuses on reducing acquisition time through compressed sensing techniques and developing mobile form factors that allow measurement during normal activities.

5.3. Security Analysis

Table 1.

BFDC Novelty to Threat Mitigation Mapping.

Table 1.

BFDC Novelty to Threat Mitigation Mapping.

| BFDC Innovation |

Threat Mitigated |

Mitigation Mechanism |

| Whole-body EM resonance profiling |

Static biometric cloning |

Real-time harmonic capture across full body field |

| Gradient-entropy hashing |

Template tampering, spoofing |

Spatial variation encoding + tamper-evident hash |

| Phase-shift encryption |

Replay attacks, biometric inversion |

Phase-locked encoding tied to biometric waveform |

| Harmonic replay challenge-response |

Deepfake, synthetic biometric spoofing |

Live response validation via harmonic synthesis |

| High-dimensional vector modeling |

Impersonation, feature overlap |

Unique biometric signature per posture and state |

| Quantum magnetometry for sensing |

Thermal spoofing, synthetic field injection |

Quantum-verified EM mapping and physical validation |

The security of BFDC rests on multiple interdependent layers. The high dimensionality of the feature space (30,000+ dimensions) provides information-theoretic security against brute-force attacks. With 127 bits of entropy per user, the probability of random collision is approximately 2^{-127}, far exceeding the security requirements for most cryptographic applications.

The gradient-entropy hashing scheme ensures that even small perturbations in the measured electromagnetic field produce avalanche effects in the output hash, preventing hill-climbing attacks. The incorporation of temporal dynamics through phase-shift encryption binds the cryptographic key to the specific measurement instance, preventing replay attacks even if an attacker obtains previous measurement data.

5.4. Post-Quantum Resilience

Definition 12 (Quantum Security Model). The security of BFDC against quantum adversaries is analyzed under the quantum random oracle model (QROM) [

11].

Theorem 6 (Post-Quantum Security). Under the assumption that cloning a physical electromagnetic field distribution requires exponential quantum resources, BFDC achieves post-quantum security with:

Grover Resistance: Against quantum search, the effective key space provides security: T_Grover = O(2^{k/2}) = O(2^{63.5}) quantum operations

Physical Unclonability: The quantum no-cloning theorem prevents perfect replication of the quantum states involved in measurement: ||ρ_clone - ρ_original||_tr ≥ 1 - exp(-D_eff)

where D_eff ≈ 10^4 is the effective dimensionality and ||·||_tr denotes trace distance.

- 3.

Measurement Disturbance: Any attempt to precisely characterize the electromagnetic field necessarily disturbs it: ΔB · Δ(∂B/∂t) ≥ ℏ/(4πm_e)

where m_e is the electron mass.

Lemma 4 (Hash Function Security). The SHA3-512 construction provides 256-bit quantum security [

11]:

where q is the number of quantum queries to the oracle.

Furthermore, the hash-based key derivation scheme uses SHA3-512, which provides 256-bit security against quantum attacks using Grover's algorithm. The error correction codes employ classical coding theory that does not rely on number-theoretic assumptions vulnerable to Shor's algorithm [

9]. This positions BFDC as a truly post-quantum biometric cryptosystem.

5.5. Future Directions

Several research directions could further enhance BFDC:

Multimodal Fusion: Combining electromagnetic sensing with other quantum-enhanced modalities (e.g., quantum optical coherence tomography) could further increase entropy and robustness.

Distributed Sensing: Networks of BFDC nodes could enable secure multi-party computation protocols based on correlated biometric measurements.

Health Monitoring: The rich physiological information captured by BFDC could enable simultaneous authentication and health monitoring, adding value beyond security applications.

Standardization: Development of standards for quantum biometric systems will be crucial for interoperability and widespread adoption.

6. Conclusions

BFDC marks a paradigm shift in biometric cryptography—redefining biometric inputs not as identity proxies, but as high-dimensional entropy substrates for live key generation. By combining quantum sensing, phase-aware encoding, and harmonic replay challenges, it offers a uniquely defensible response to spoofing, cloning, and replay threats in post-quantum ecosystems.

This work lays the groundwork for standards-compliant cryptographic primitives that fuse physical embodiment, temporal dynamics, and biometric uniqueness—heralding a new frontier in secure identity systems and zero-trust architectures.

Author Contributions

R.C.S. conceived the BFDC framework, designed the experimental methodology, implemented the quantum sensing protocols, performed the security analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to privacy and security constraints inherent to biometric data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full Form |

| BFDC |

Biometric Feature-Dimension Cryptography |

| EM |

Electromagnetic |

| QZFM |

Quantum Zero-Field Magnetometer |

| OPM |

Optically Pumped Magnetometer |

| NV |

Nitrogen-Vacancy |

| PQC |

Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| FIPS |

Federal Information Processing Standards |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| FAR |

False Acceptance Rate |

| FRR |

False Rejection Rate |

| EER |

Equal Error Rate |

| SERF |

Spin-Exchange Relaxation-Free |

| DWT |

Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| STFT |

Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| BCH |

Bose-Chaudhuri-Hocquenghem |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

References

- Kaur, P.; Kumar, N.; Singh, M. Biometric Cryptosystems: A Comprehensive Survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 16635–16690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Ross, A.; Pankanti, S. Biometrics: A Tool for Information Security. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2006, 1, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.-H. Biometric Discretization for Template Protection and Cryptographic Key Generation. In Biometric Security; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2015; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Herb, K.; Völker, L.A.; Gärtner, M.; et al. Quantum Magnetometry of Transient Signals with a Time Resolution of 1.1 Nanoseconds. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Wu, T.; Guo, H. Sensitivity of Quantum Magnetic Sensing. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzoli, L.; Ghirardi, L.; Rizzi, M.; Cirac, J.I. Lattice Quantum Magnetometry. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 062330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinani, S.; Wagner, U. Post-Quantum Cryptography: A Comprehensive Guide; cnlab security AG: Rapperswil, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.cnlab.ch/fileadmin/documents/Publikationen/2025/Post-Quantum_Cryptography_-__A_Comprehensive_Guide.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- NIST. Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards. NIST Interagency/Internal Report (IR) 8547-IPD, 2024. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2024/NIST.IR.8547.ipd.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- NIST. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Project. 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Dodis, Y.; Ostrovsky, R.; Reyzin, L.; Smith, A. Fuzzy Extractors: How to Generate Strong Keys from Biometrics and Other Noisy Data. SIAM J. Comput. 2008, 38, 97–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Dagdelen, Ö.; Fischlin, M.; Lehmann, A.; Schaffner, C.; Zhandry, M. Random Oracles in a Quantum World. In Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2011; Lee, D.H., Wang, X., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, H.; Eronen, P. HMAC-based Extract-and-Expand Key Derivation Function (HKDF). RFC 5869, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.M.; Eisert, J.; Guehne, O. Entanglement Properties of Physical Systems: A Review. Quantum Inf. Process. 2009, 8, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).