1. Introduction

The measurement problem in quantum mechanics remains one of physics’ most profound challenges. Despite the theory’s extraordinary predictive success, the transition from quantum superposition to classical measurement outcomes, governed by the Born rule [

1], lacks a mechanistic explanation. The Schrödinger equation describes deterministic, unitary evolution, yet measurements yield probabilistic, irreversible outcomes, prompting interpretations including Copenhagen [

2], many-worlds [

3], pilot wave [

4], and objective collapse theories [

5]. Each addresses specific issues but leaves fundamental questions unresolved.

Recent advances in quantum information theory suggest reality’s fundamentally informational nature, as proposed by Wheeler’s “it from bit” conjecture [

6]. Rigorous derivations of quantum mechanics from information-theoretic principles [

7,

8] and the remarkable efficiency of quantum computers in simulating quantum systems [

9] suggest deep connections between computation and physical reality. These developments, combined with advances in generative artificial intelligence [

10], inspire a radically new approach.

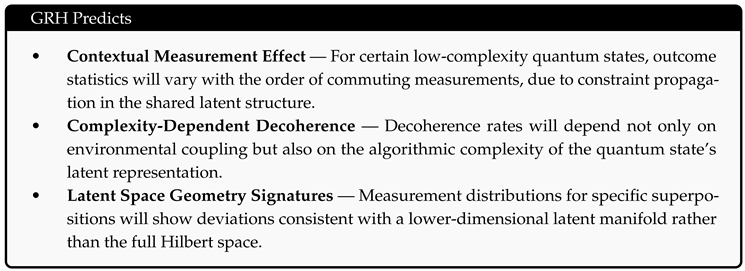

We propose the Generative Reality Hypothesis (GRH): physical reality operates as a generative information-processing system, where quantum mechanics represents the computational architecture underlying this process. Quantum superposition corresponds to latent representation spaces in generative models, measurements trigger generative sampling events, and the Born rule defines the fundamental sampling algorithm of reality. While mathematical equivalence can be established between different formalisms, the value of GRH lies in its potential to provide a mechanistic, ontological foundation for quantum processes, moving beyond abstract state spaces to a model of reality as an active computation.

This framework recasts the measurement problem by reinterpreting quantum superposition as computational potential rather than multiple co-existing physical realities. It provides a mechanistic explanation for quantum entanglement via shared latent representations and for wave-particle duality as a “process duality” between latent evolution and generative sampling. Most importantly, GRH makes specific, testable predictions about decoherence scaling, measurement dynamics, and information flow that can be experimentally verified with current quantum technologies.

These core predictions provide experimentally testable consequences that distinguish GRH from standard quantum mechanics:

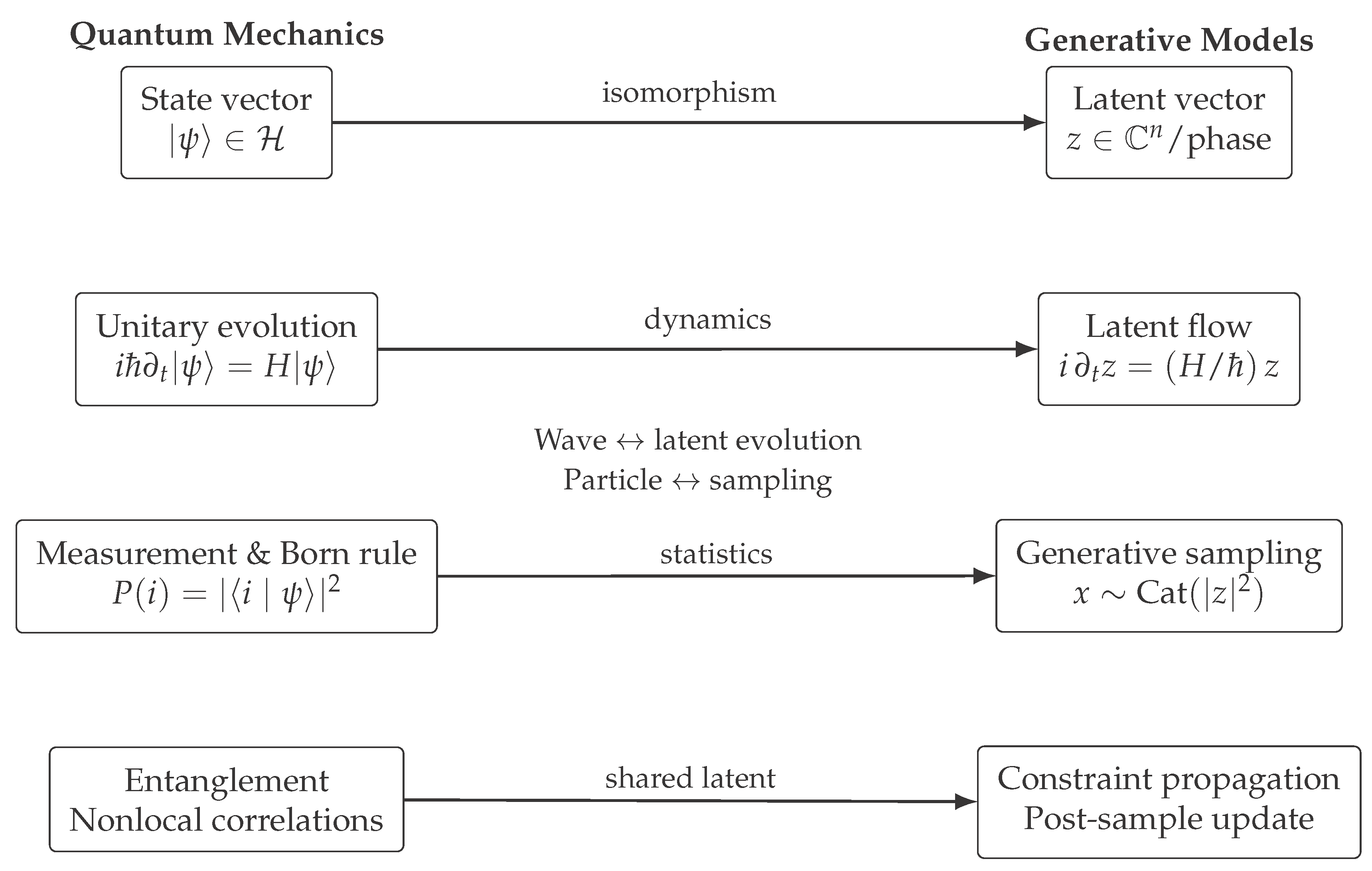

Figure 1.

High-level GRH mapping between quantum mechanics and generative models.

Figure 1.

High-level GRH mapping between quantum mechanics and generative models.

2. Mathematical Foundations

2.1. Exact Equivalence Framework

We begin by establishing precise mathematical equivalences between quantum mechanics and generative models, starting with the simplest possible systems and building toward more complex scenarios.

2.1.1. Single Qubit as Discrete Generative Model

Consider a qubit evolving under a time-independent Hamiltonian

. The quantum state evolves as

We establish an exact equivalence with a temporal generative model by defining a latent variable

where

The generative distribution is then

Theorem 1. The quantum amplitude evolution is isomorphic to the latent space trajectory of this generative model.

Proof. Let . Define the mapping . Up to global phase, this mapping is bijective because normalized complex coefficients uniquely specify , and vice versa. Probabilities are preserved: . Inner products are preserved: .

Quantum evolution obeys the Schrödinger equation

which in the

basis reduces to

Equivalently,

which is the latent flow equation in the generative framework. Thus the mapping preserves dynamics, probabilities and geometry (both evolve on

), establishing the isomorphism. □

2.1.2. Measurement as Conditional Sampling

For observable

with eigenstates

, measurement probabilities are

In the generative framework define sampling operation

that draws from the categorical distribution

The post-measurement latent update is

and

is the

k-th standard basis vector. Measurement statistics coincide exactly with generative sampling statistics.

2.2. Two-Qubit Entanglement as Correlated Generation

2.2.1. Mathematical Formulation

This corresponds to the latent representation

Marginal sampling on qubit

A yields

Upon observing outcome

, the latent vector undergoes constraint propagation:

where

projects onto the subspace consistent with

k. Subsequent sampling uses

as the generative source.

2.2.2. Non-Locality as Computational Consistency

Theorem 2. The generative model reproduces Bell inequality violations exactly.

Proof sketch For measurement settings at angles on the Bell state the quantum correlation is . The generative model samples A, applies a constraint to the shared latent z, and then samples B conditioned on the constrained latent. Because constraint propagation acts within the complex Hilbert geometry rather than a classical probability simplex, the model reproduces the quantum correlation functions, and thus violates CHSH with . A full derivation is presented in Appendix A. □

2.3. Dynamics: Hamiltonian Evolution as Latent Flow

2.3.1. Continuous Generative Dynamics

The Schrödinger equation

maps to the latent-space flow

so quantum evolution corresponds to geodesic flow on complex projective space

, and generative evolution represents flow on an isomorphic latent manifold.

2.3.2. Decoherence as Stochastic Latent Diffusion

Environmental decoherence, described by the Lindblad master equation,

maps to a stochastic differential equation for the state vector,

where

are independent Wiener processes. Environmental decoherence corresponds to noise in the latent space.

2.4. Complexity-Dependent Decoherence

We propose that decoherence rates depend on the computational complexity of maintaining quantum states. For a pure state

, define a complexity ansatz

where

is the von Neumann entropy across a chosen bipartite split and the second term captures descriptive amplitude complexity (coding cost).

Rationale. The additive form reflects two orthogonal contributions: (i) entanglement structure (captured by

) and (ii) amplitude coding cost, which penalizes non-uniform superposition structure. We considered alternatives (e.g., Kolmogorov complexity of the wavefunction), but they are not experimentally accessible with current platforms;

balances physical interpretability with measurability and supports regression-based tests across diverse state families.

Hypothesis:

where

is a universal constant characterizing the computational cost of coherence. This implies that sufficiently complex states spontaneously decohere even absent environmental coupling.

2.5. Wave-Particle Duality as a Process Duality

In GRH, wave-particle duality is a duality of process modes.

Wave behavior (latent evolution)

When a system propagates unmeasured, its latent vector evolves continuously:

In a double-slit experiment the post-slit latent vector is a coherent superposition

, and detection probabilities follow

which yields interference.

Particle behavior (generative sampling)

A which-path measurement triggers a discrete sampling event:

After sampling interference terms vanish and the distribution reduces to single-slit contributions.

3. Information-Theoretic Foundations

3.1. The Born Rule as Optimal Sampling Algorithm

Theorem 3. Under assumptions of definite outcomes, probabilities depending only on state, and no-signaling for composites, the Born rule is uniquely determined as the optimal sampling algorithm for extracting classical information from quantum latent representations.

Sketch. Following Masanes et al. [

7] and Hardy [

8], operational constraints on measurements imply the Born rule. From a computational perspective the Born rule minimizes extractable statistical bias while preserving consistency and no-signaling, making it the natural sampling prescription for an objective generative substrate. □

3.2. Wheeler’s “It from Bit” and Computational Reality

Wheeler’s conjecture that reality emerges from binary information [

6] aligns with GRH’s informational ontology. The “it from bit” principle finds concrete expression in discrete sampling operations that extract classical “its” from quantum “bits”.

3.3. Quantum Error Correction and Computational Optimization

Quantum error correction thresholds highlighting[

12] mirror GRH’s computational perspective: natural systems transition to classicality when the computational cost of maintaining coherence exceeds available resources.

4. Experimental Predictions and Falsifiability

GRH makes five specific, quantitative predictions that differ measurably from standard quantum mechanics (SQM).

4.1. Latent Space Geometry Test

Prediction

If quantum states are points in a generative latent space, pairwise distances must follow the Fubini–Study metric:

Protocol

Prepare states on superconducting qubits; use process tomography to measure transition probabilities; construct empirical distance matrix; test conformity to Fubini–Study with a analysis.

4.1.0.5. Falsifiability

Systematic deviations exceeding falsify GRH’s geometric foundations.

Required precision

State preparation fidelity >99%, tomography accuracy .

4.2. Complexity-Dependent Decoherence Scaling

Prediction

Decoherence rates scale with computational complexity, not just qubit number

N and entanglement entropy

S. One candidate scaling:

with universal constants

.

Protocol

Prepare entangled states of varying complexity on trapped ions; measure via Ramsey interferometry while controlling environmental noise; perform multivariate regression.

Falsifiability

Absence of predicted scaling with confidence would falsify GRH.

Required precision

>100 distinct states; coherence measurements accurate to ; systematic errors <0.1% of predicted effect.

4.3. Temporal Structure of Measurement

Prediction

Collapse exhibits temporal structure rather than instantaneous transitions. GRH provides a model for collapse statistics.

Protocol

Continuous weak measurements on superconducting qubits; record measurement current with ns resolution; reconstruct quantum trajectories .

GRH prediction

Inter-collapse intervals follow an exponential distribution; collapse duration scales as .

Statistical test

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test comparing observed collapse statistics to GRH versus alternatives.

4.4. Contextual Measurement Effects

Prediction

Measurement outcomes exhibit weak dependence on global experimental context beyond the measured observable.

Protocol

Prepare a three-qubit system, vary operations on unmeasured qubit 3 while measuring correlation between qubits 1 and 2; control classical crosstalk and artifacts.

GRH prediction

shows detectable () dependence on qubit 3’s state even if unentangled.

SQM prediction

is independent of qubit 3 for unentangled systems.

Required precision

Correlation accuracy ; repetitions per configuration.

4.5. Information Recovery from Decoherence

Prediction

Information undergoes redistribution, not destruction, enabling recovery beyond standard thresholds.

Protocol

Implement a surface code on superconducting qubits; apply controlled decoherence; perform error correction.

GRH prediction

Recovery possible at error rates a factor 2– above standard threshold.

Falsifiability

Recovery fidelity at threshold with significance supports GRH.

Experimental Roadmap (practical order).

A feasible progression is: (1) Latent-space geometry (lowest complexity, quick tomography loops); (2) Contextual measurement effects on small registers with aggressive artifact controls; (3) Temporal structure of measurement using existing weak-measurement hardware; (4) Complexity-dependent decoherence via curated state families and regression; (5) Information recovery in surface codes at elevated noise rates.

5. Relationship to Existing Interpretations

Copenhagen

GRH provides a mechanistic foundation: collapse is generative sampling. The classical-quantum boundary becomes a computational interface.

Many-worlds

GRH avoids multiplicity by treating superposition as computational potential rather than literal branching universes.

Pilot-wave

GRH replaces hidden variables with computational processes; the guidance equation may emerge as an effective description of sampling dynamics.

Objective collapse

Spontaneous localization in GRW-like models can be reinterpreted as computationally triggered sampling when complexity becomes prohibitive.

QBism

Unlike QBism [

23], GRH posits an observer-independent computational substrate.

6. Advanced Mathematical Connections

6.1. Quantum Information Geometry

The Fisher information metric maps to the Riemannian structure of the generative latent manifold.

6.2. Topological Quantum Computation

Topologically protected states correspond to generative models with topologically stable latent representations; braiding maps to homotopy-invariant transformations.

6.3. AdS/CFT and Holographic Information Storage

Holographic emergence of spacetime from entanglement [

13,

14,

15] finds a natural analog in GRH: output geometry arises from latent-space entanglement structure.

7. Quantum Field Theory Extension

7.1. Field Operators as Continuous Generative Functions

In QFT the field operator

becomes a continuous generative mapping from latent codes to spatial configurations:

7.2. Path Integral as Generative Process Integral

The Feynman path integral

corresponds to an integration over generative process trajectories,

7.3. Spacetime Emergence

Note (speculative). The following subsection outlines conjectural structures intended as research directions rather than a completed formalism.

We conjecture that spacetime geometry emerges from the computational graph structure of the underlying generative model. The metric tensor may be expressed formally as

where

S is the generative process “action”. This is speculative; achieving full Lorentz covariance is a primary challenge for future development.

Computational interpretation of Lorentz invariance. Within GRH, spacetime geometry may be understood as an emergent property of the computational graph underlying the generative process. A natural interpretation of special relativity arises when we treat the invariant speed of light,

c, as the

maximum spatial update rate the generative system can sustain per unit of proper time. The Minkowski metric

can then be reinterpreted as a

computational resource constraint:

where

represents the processing cost of updating spatial coordinates, and

is the cost of temporal progression in the latent manifold. Increasing spatial velocity consumes more of the fixed budget for state evolution, leaving fewer computational steps available for temporal updates—observed phenomenologically as time dilation. This “spacetime exchange rate” perspective suggests that Lorentz invariance emerges naturally from a deeper invariance of computational bandwidth, with

c as the universal exchange constant between spatial and temporal computation.

8. Statistical Framework for Experimental Validation

8.1. Bayesian Model Comparison

Decision criteria: strong evidence for GRH; GRH falsified; inconclusive.

8.2. Multiple Testing Corrections

With five independent tests we apply Bonferroni correction: require individual significance to keep family-wise .

8.3. Required Sample Sizes

Power analysis indicates: geometry test state pairs; complexity scaling states; measurement dynamics trajectories; contextuality repetitions; information recovery trials.

9. Technological Implications

9.1. Quantum Computing Applications

GRH suggests quantum computers access reality’s computational substrate, enabling quantum-inspired generative algorithms, novel error correction, and hybrid quantum-classical models.

9.2. Artificial Intelligence Enhancements

The mathematical equivalences suggest quantum-enhanced variational autoencoders, coherent generative sampling, and entanglement-based data correlations for AI improvements.

10. Cosmological Implications

Note (speculative). The discussions in this section are exploratory and are offered to indicate potential directions rather than settled claims.

10.1. Universal Computation and Its Substrate

GRH raises the “computational substrate problem”: what physical system executes the universal computation? GRH aims to describe the operational logic—the “software”—not the ultimate hardware, similar to cosmology’s questions about “before” the Big Bang.

10.2. Information, Thermodynamics, and Computational Limits

The framework connects to Landauer’s principle [

25], suggesting that irreversible generative sampling (measurement) dissipates heat and contributes to the thermodynamic arrow of time. Furthermore, finite computational capacity implies constraints on evolution (e.g., Bekenstein bound [

26]).

In this light, the speed of light c may be understood as the ultimate computational exchange rate between spatial and temporal updates within the universe’s generative process. Just as Landauer’s principle bounds the thermodynamic cost of irreversible computation, c bounds the rate at which spatial information can be updated without sacrificing temporal coherence. This reinforces the idea that spacetime itself is a manifestation of finite computational capacity.

11. Future Research Directions

11.1. Theoretical Development

Priorities: (1) develop a fully relativistic QFT formalization consistent with Lorentz invariance under the computational constraint, (2) derive emergent spacetime models from computational graphs, (3) refine complexity measures theoretically and empirically, (4) explore cosmological applications.

11.2. Experimental Program

The five tests in

Section 4 form a validation program. Some tests may be feasible within 2–3 years; full program within 5–7 years given current technological trajectories.

11.3. Technological Development

Applications in quantum computing and AI represent immediate practical opportunities.

12. Conclusions

The Generative Reality Hypothesis provides a novel, mathematically rigorous framework for understanding quantum mechanics through the lens of computational generative processes. By establishing formal equivalences between quantum dynamics and specific generative models, we have developed a theory that: (1) recasts the measurement problem into computational sampling of latent spaces, (2) explains entanglement mechanistically via shared latent representations and constraint propagation, (3) resolves wave-particle duality as a process duality between latent evolution and generative sampling, (4) connects quantum mechanics to information theory and computational complexity, (5) makes precise, falsifiable predictions for experiment, and (6) suggests practical applications for QC and AI. The framework’s most significant contribution is its testability. If validated, GRH would indicate the universe operates as a vast generative information processor. If falsified, GRH will have provided precise, testable hypotheses that further our understanding of quantum foundations.

Appendix A. Full Proof of Theorem 2

Theorem A1. The generative model for the Bell state with latent representation reproduces Bell inequality violations exactly, matching quantum mechanical predictions.

Proof. We show the generative model’s conditional sampling reproduces the quantum correlation .

Quantum baseline:

For observables

and

on qubits A and B, for

one finds

and mixed terms vanish, so

With CHSH angles the quantum value violates the classical bound 2.

Generative model:

Measure A in basis

where

. Marginal probabilities

. If A is

, the post-measurement (constrained latent) state is

. Measuring B in

yields conditional probabilities

and similar expressions for other outcomes. Compute joint probabilities:

Hence

matching quantum mechanics. Thus the generative sampling reproduces the CHSH violation exactly. □

Glossary (ML ↔ QM)

Latent space (ML) ↔ state vector / Hilbert space (QM)

Generative sampling (ML) ↔ measurement / Born rule (QM)

Latent flow (ML) ↔ unitary evolution / Schrödinger dynamics (QM)

Constraint propagation (ML) ↔ post-measurement update / projection (QM)

References

- M. Born, “Zur Quantenmechanik der Stoßvorgänge,” Zeitschrift für Physik, 37(12):863–867 (1926).

- W. Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science, Harper & Row (1958).

- H. Everett, “Relative state” formulation of quantum mechanics, Rev. Mod. Phys., 29(3):454–462 (1957).

- L. de Broglie, “La nouvelle dynamique des quanta,” in Electrons et Photons, Rapports et Discussions du Cinquième Conseil de Physique, 105–141 (1928).

- G. C. Ghirardi, A. Rimini, T. Weber, “Unified dynamics for microscopic and macroscopic systems,” Phys. Rev. D, 34(2):470–491 (1986).

- J. A. Wheeler, “Information, physics, quantum: The search for links,” Proc. 3rd Int. Symp. on Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, 354–368 (1989).

- L. Masanes, T. D. Galley, M. P. Müller, “The measurement postulates of quantum mechanics are operationally redundant,” Nat. Commun., 10:1361 (2019).

- L. Hardy, “Quantum theory from five reasonable axioms,” arXiv:quant-ph/0101012 (2001).

- S. Lloyd, “Universal quantum simulators,” Science, 273(5278):1073–1078 (1996).

- I. Goodfellow et al., “Generative adversarial nets,” Adv. in NIPS 27 (2014).

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge Univ. Press (2010).

- D. Aharonov and M. Ben-Or, “Fault-tolerant quantum computation with constant error rate,” SIAM J. Comput., 38(4):1207–1282 (2008).

- J. Maldacena, “The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity,” Int. J. Theor. Phys., 38(4):1113–1133 (1999).

- M. Van Raamsdonk, “Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement,” Gen. Relativ. Gravit., 42(10):2323–2329 (2010).

- S. Ryu, T. Takayanagi, “Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 96(18):181602 (2006).

- M. Schlosshauer, J. Kofler, A. Zeilinger, “A snapshot of foundational attitudes toward quantum mechanics,” Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. B, 44(3):222–230 (2013).

- W. H. Zurek, “Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical,” Rev. Mod. Phys., 75(3):715–775 (2003).

- A. M. Gleason, “Measures on the closed subspaces of a Hilbert space,” J. Math. Mech., 6(4):885–893 (1957).

- W. H. Zurek, “Pointer basis of quantum apparatus,” Phys. Rev. D, 24(6):1516–1525 (1981).

- M. Schlosshauer, Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition, Springer (2007).

- J. S. Bell, “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox,” Physics (N.Y.), 1(3):195–200 (1964).

- A. Aspect, J. Dalibard, G. Roger, “Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 49(25):1804–1807 (1982).

- C. M. Caves, C. A. Fuchs, R. Schack, “Quantum probabilities as Bayesian probabilities,” Phys. Rev. A, 65(2):022305 (2002).

- E. Fredkin, “An introduction to digital philosophy,” Int. J. Theor. Phys., 42(2):189–247 (2003).

- R. Landauer, “Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process,” IBM J. Res. Dev., 5(3):183–191 (1961).

- S. W. Hawking, “Breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse,” Phys. Rev. D, 14(10):2460–2473 (1976).

- J. Preskill, “Quantum information and precision measurement,” J. Mod. Opt., 45(2):305–316 (1998).

- D. P. Kingma, M. Welling, “Auto-encoding variational Bayes,”. arXiv:1312.6114 (2013).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).