Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Methods

Inclusion Criteria

- Adults with severe trauma (ISS>15) with TBI

- Treated at HGUGM

- Trauma occurring between 1993 and 2018

- Accessible data

Variables Analyzed

Specific Variables Included:

- Epidemiological: age, sex, trauma date

- Medical history and trauma characteristics: type (blunt/penetrating), intent (accidental/self-inflicted/assault)

- Trauma cause: traffic accidents (car, motorcycle, pedestrian), falls, assaults, others

- Severity indicators and protective factors: seatbelt/helmet use, fall height, prehospital vital signs, care by emergency medical teams (SAMUR-061), initial shock, cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intubation, lactate, fluid resuscitation

- In-hospital: vital signs, emergency surgery, transfusions, injury location and severity (AIS, ISS, NISS)

- Outcomes: ICU admission, complications, and mortality (day 1, 30-day, overall), including preventable deaths

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Analysis

3.2. Initial Care

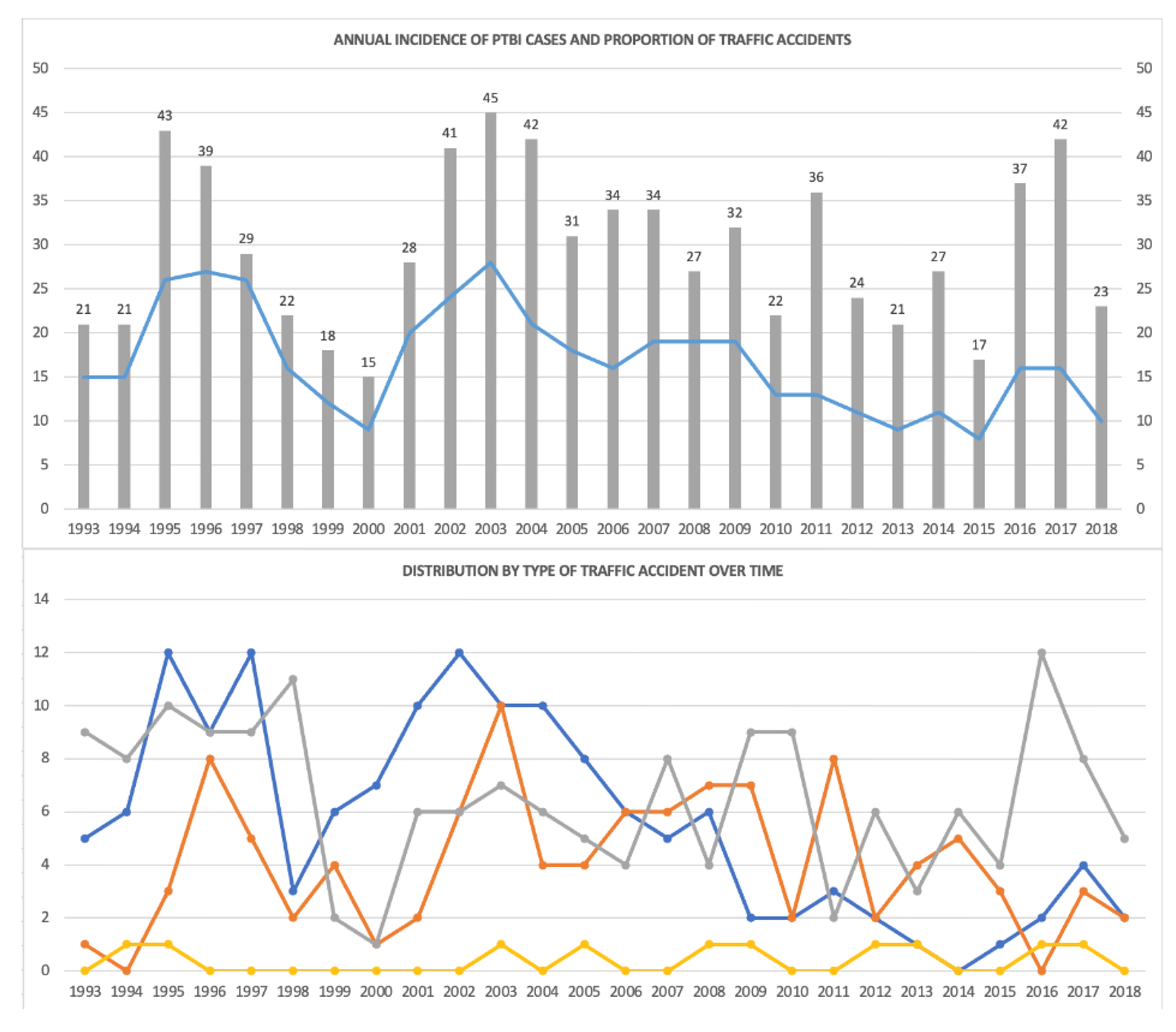

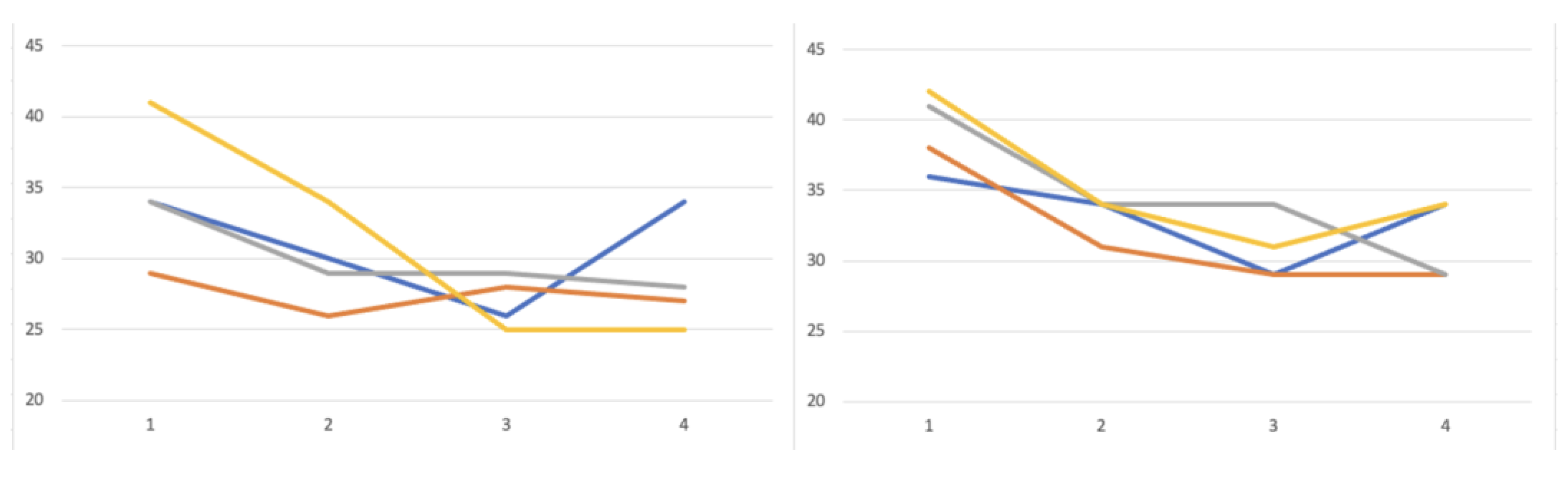

3.3. Period-Base Analysis

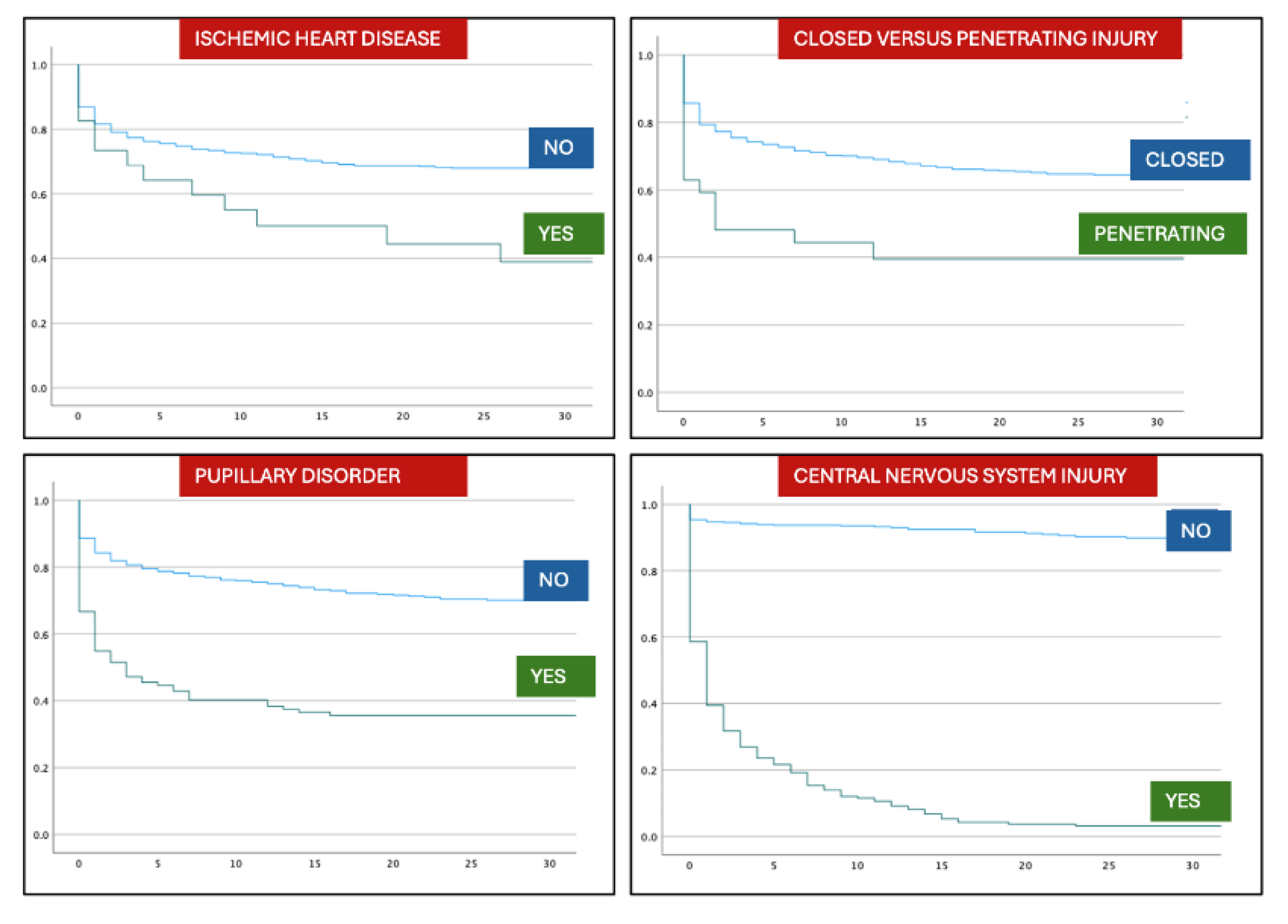

3.3. Mortality Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Abbreviated Injury Scale |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRASH | Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Score |

| HDUDM | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon |

| IMPACT | International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ISS | Injury Severity Score |

| NISS | New Injury Severity Score |

| PTBI | Polytrauma with Traumatic Brain Injury |

| RTA | Road Traffic Accidents |

| SAMUR-061 | Madrid Emergency Medical Service |

| TBI | Traumatic Brain Injury |

| TRISS | Trauma and Injury Severity Score |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- F.D. Schubert, L. J. Gabbe, M. A. Bjurlin, and A. Renson, “Differences in trauma mortality between ACS-verified and state-designated trauma centers in the US,”. Injury 2019, 50, 186–191. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Spahn, B. Bouillon, V. Cerny, J. Duranteau, D. Filipescu, and B. J. Hunt, “Guia europea sangrado y coagulación,”. Crit Care 2019, 23, 1–74. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, “The global burden of disease : 2004 update,” WHO overview. Accessed: Aug. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563710.

- M.Chico-Fernández et al., “Epidemiología del trauma grave en Espa ˜ na. REgistro,” . Med Intensiva, 2015, 40. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Clark, S. Neumann, S. Hopkins, A. Kostopoulos, L. Hagerman, and M. Dobbins, “Changes to Public Health Surveillance Methods Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review,”. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2024, 10, e49185. [CrossRef]

- L. Moore et al., “Trends in Injury Outcomes Across Canadian Trauma Systems,”. JAMA Surg 2017, 152, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K.Scarborough, “Reduced Mortality at a Community Hospital Trauma Center,”. Archives of Surgery 2008, 143, 22. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad-Asuntos Sociales-Igualdad, “Lesiones en España Análisis de la legislación sobre prevención de lesiones no intencionales,” Ministerio de Sanidad, Asuntos Sociales e Igualdad. Accessed: Aug. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/lesiones/legislacion/docs/LESIONES_Espana.pdf.

- M.-A. R. Pineda-Jaramillo J, Barrera-Jimenez H, “Unveiling the relevance of traffic enforcement cameras on the severity of vehicle-pedestrian collisions in an urban environment with machine learning models,” . J Safety Res 2022, 81, 225–238. [CrossRef]

- L. Aharonson-Daniel et al., “Different AIS triplets: Different mortality predictions in identical ISS and NISS,”. Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care 2006, 61, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Serviá et al., “Machine learning techniques for mortality prediction in critical traumatic patients: anatomic and physiologic variables from the RETRAUCI study,” . BMC Med Res Methodol 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.M. Lossius, M. Rehn, K. E. Tjosevik, and T. Eken, “Calculating trauma triage precision: effects of different definitions of major trauma,” . J Trauma Manag Outcomes 2012, 6, 1. [CrossRef]

- Q.Deng et al., “Comparison of the ability to predict mortality between the injury severity score and the new injury severity score: A meta-analysis,” . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- L. A.Santiago, B. C. Oh, P. K. Dash, J. B. Holcomb, and C. E. Wade, “A clinical comparison of penetrating and blunt traumatic brain injuries,”. Brain Inj 2012, 26, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.A. Hyder, C. A. Wunderlich, P. Puvanachandra, G. Gururaj, and O. C. Kobusingye, “The impact of traumatic brain injuries: A global perspective,” . NeuroRehabilitation 2007, 22, 341–353. [CrossRef]

- I.R. Maas et al., “The Lancet Neurology Commission Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research Executive summary The Lancet Neurology Commission,” . Lancet Neurol 2017, 16, 987–1048.

- D.Benz and Z. J. Balogh, “Damage control surgery: Current state and future directions,”. Curr Opin Crit Care 2017, 23, 491–497. [CrossRef]

- J.B. Holcomb et al., “Damage control resuscitation: Directly addressing the early coagulopathy of trauma,” . ournal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care 2007, 62, 307–310. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Hynes et al., “Staying on target: Maintaining a balanced resuscitation during damage-control resuscitation improves survival,” . J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2021, 91, 841–848. [CrossRef]

- E.Picetti et al., “WSES consensus conference guidelines: Monitoring and management of severe adult traumatic brain injury patients with polytrauma in the first 24 hours,”. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2019, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- H.C. Pape and L. Leenen, “Polytrauma management - What is new and what is true in 2020 ?,”. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021, 12, 88–95. [CrossRef]

- H.-C. Pape et al., “The definition of polytrauma revisited: An international consensus process and proposal of the new ‘Berlin definition’.,”. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014, 77, 780–786. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Border, J. LaDuca, and R. Seibel, “Priorities in the management of the patient with polytrauma.,” . Prog Surg, 1975, 14, 84–120. [CrossRef]

- M. Hardy, N. Enninghorst, K. L. King, and Z. J. Balogh, “The most critically injured polytrauma patient mortality: should it be a measurement of trauma system performance?,” Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2024, 50, 115–119. [CrossRef]

- V.Hamill, S. J. E. Barry, A. McConnachie, T. M. McMillan, and G. M. Teasdale, “Mortality from head injury over four decades in Scotland,” . J Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 689–703. [CrossRef]

- K.Menon and C. Zahed, “Prediction of outcome in severe traumatic brain injury,”. Curr Opin Crit Care 2009, 15, 437–441. [CrossRef]

- K. Y. Ahmed N, “Prediction of Trauma Mortality Incorporating Pre-injury Comorbidities into Existing Mortality Scoring Indices. Am Surg 2022, 2. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Beaulieu E, Naumann RB, Deveaux G, Wang L, Stringfellow EJ, Lich KH, “Impacts of alcohol and opioid polysubstance use on road safety: Systematic review,”. Accid Anal Prev 2022, 173, 106713. [CrossRef]

- F. Hildebrand et al., “Management of polytraumatized patients with associated blunt chest trauma: a comparison of two European countries.,”. Injury 2005, 36, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- T. Brinck, M. Heinänen, T. Söderlund, R. Lefering, and L. Handolin, “Does arrival time affect outcomes among severely injured blunt trauma patients at a tertiary trauma centre?,”. Injury 2019, 50, 1929–1933. [CrossRef]

- J. MacKenzie and F. P. Rivara, “A National Evaluation of the Effect of Trauma-center Care on Mortality,” Journal of Trauma Nursing 2006, 13, 150. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Larkin EJ, Jones MK, Young SD, “Interest of the MGAP score on in-hospital trauma patients: Comparison with TRISS, ISS and NISS scores. Injury 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Salehi, S. A. T. Dezfuli, S. S. Namazi, M. D. Khalili, and M. Saeedi, “A new injury severity score for predicting the length of hospital stay in multiple trauma patients,”. Trauma Mon 2016, 21, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- W. Kirkpatrick and S. K. D’Amours, “The RAPTOR: Resuscitation with angiography, percutaneous techniques and operative repair. Transforming the discipline of trauma surgery,” Canadian Journal of Surgery 2011, 54. [CrossRef]

- Carver, A. W. Kirkpatrick, S.D’Amours, S. M. Hameed, J. Beveridge, and C. G. Ball, “A Prospective Evaluation of the Utility of a Hybrid Operating Suite for Severely Injured Patients: Overstated or Underutilized?,”. Ann Surg 2020, 271, 958–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. e I. M. Sanidad, “Lesiones en España Análisis de la legislación sobre prevención de lesiones no intencionales,” Ministerio de Sanidad, Asuntos Sociales e Igualdad.

- Spain. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo., Revista española de salud pública., vol. 79, no. 2. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, 2005. Accessed: Jun. 04, 2020. [Online]. Available: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext>pid=S1135-57272005000200005>lng=es>nrm=iso>tlng=es. 1135.

- Q. Yuan et al., “Coagulopathy in Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Correlation with Progressive Hemorrhagic Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” . J Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1279–1291. [CrossRef]

- M. Chico-Fernández et al., “Epidemiology of severe trauma in Spain. Registry of trauma in the ICU (RETRAUCI). Pilot phase.,”. Med Intensiva 2016, 40, 327–347. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Presidencia, “RD 1428/2003 para aprobación de la ley sobre tráfico, circulación de vehículos a motor y seguridad vial,” Madrid, Dec. 2003. Accessed: Aug. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2003-23514.

- Ministerio del Interior, “Real Decreto Legislativo 6/2015, de 30 de octubre, por el que se aprueba el texto refundido de la Ley sobre Tráfico, Circulación de Vehículos a Motor y Seguridad Vial,” BOE. Accessed: Aug. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-11722.

- Blanco, “El suicidio en España. Respuesta institucional y social,” Revista de Ciencias Sociales, DS-FCS 2020, 33, 79–106. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, “Preventing suicide,” WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data 2014, 89.

| PATIENTS (n/%) | INITIAL NEUROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 43 | 20 | Pupillary disfunction (n/%) | 129 | 17 |

| Male | 548 | 71 | Deficit (n/%) | 52 | 7 |

| Female | 220 | 29 | INJURIES BY REGION AND SEVERITY (median, IQR) | ||

| Number of comorbidities | Head AIS | 4 | 3-5 | ||

| 0 | 409 | 53 | Face AIS | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 145 | 19 | Thorax AIS | 2 | 0-3 |

| ≥2 | 158 | 28 | Abdomen AIS | 0 | 0-2 |

| Type of comorbidities | Extremities AIS | 2 | 0-3 | ||

| Hypertensión | 65 | 9 | Skin AIS | 0 | 0-1 |

| Cardiopathy | 23 | 3 | ISS | 27 | 19-38 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 23 | 3 | NISS | 34 | 24-41 |

| Diabetes | 32 | 4 | INITIAL SURGERIES (n/%) | ||

| Anticoagulation | 33 | 4 | Chest tube | 169 | 22 |

| Substance abuse | 38 | 5 | Emergent surgery | 388 | 51 |

| Alcoholism | 32 | 4 | Neurosurgery | 193 | 25 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 61 | 8 | MORTALITY (n/%) | ||

| INITIAL MANAGEMENT (n/%) | Total deaths | 262 | 34 | ||

| 061-SAMUR team | 722 | 94 | Death upon arrival | 64 | 8 |

| Prehospital status | Death on first day | 137 | 19 | ||

| Intubation | 488 | 64 | CAUSE OF DEATH (n/%) | ||

| CPR | 36 | 5 | CNS injury | 212 | 28 |

| Apnea | 115 | 15 | Exanguination | 40 | 5 |

| Shock | 136 | 9 | Sepsis | 13 | 2 |

| CAUSES OF SHOCK AT ADMISSION (n/%) | Multiorgan failure | 13 | 2 | ||

| CNS | 36 | 26 | Distributive shock | 5 | 0.7 |

| Multiple | 26 | 19 | Cardiorrespiratory injury | 14 | 2 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 20 | 15 | COMPLICATIONS (n/%) | ||

| Fractures | 12 | 9 | 1 | 252 | 33 |

| Other | 42 | 31 | >1 | 14 | 2 |

| STUDY PERIODS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| n | 184 | 206 | 191 | 187 |

| Age (mean, +/- SD) | 38 (+/- 17) | 38 (+/- 17) | 42 (+/-21) | 54 (+/-22) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 137 (75%) | 151 (73%) | 143 (75%) | 117 (63%) |

| Female | 47 (25%) | 55 (27%) | 48 (25%) | 70 (37%) |

| COMORBIDITY | ||||

| No history | 145 (79%) | 101 (49%) | 91 (48%) | 72 (39%) |

| Hypertension | 0 | 6 (3%) | 20 (10%) | 39 (21%) |

| Cardiopathy | 0 | 3 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 14 (7%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0 | 7 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 10 (5%) |

| Diabetes | 0 | 6 (3%) | 6 (3%) | 20 (11%) |

| Anticoagulation | 0 | 6 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 22 (12%) |

| Substance abuse | 6 (3%) | 16 (8%) | 8 (4%) | 8 (4%) |

| Alcoholism | 5 (3%) | 14 (7%) | 8 (4%) | 5 (3%) |

| Psychiatric disorder | 5 (3%) | 16 (8%) | 17 (9%) | 24 (13%) |

| CAUSE OF TRAUMA | ||||

| Car | 52 (28%) | 59 (29%) | 24 (13%) | 12 (6%) |

| Motorcycle | 24 (13%) | 31(15%) | 37 (19%) | 18 (10%) |

| Bicycle | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 5 (3%) |

| Pedestrian | 59 (32%) | 32 (16%) | 49 (26%) | 59 (32%) |

| Fall | 40 (22%) | 36 (17%) | 53 (28%) | 68 (36%) |

| Suicide | 0 | 6 (3%) | 10 (5%) | 25 (13%) |

| Firearm | 4 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 3 (2%) |

| Sharp weapon | 1 (0,5%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (0,5%) |

| TRAUMA BY CAR ACCIDENT | TRAUMA BY MOTORCYCLE ACCIDENT | |||||||

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| n | 52 | 59 | 24 | 12 | 24 | 31 | 37 | 18 |

| Age (mean +/- SD) | 34 (+/- 14) | 34 (+/- 14) | 26 (+/-8) | 41 (+/-21) | 24 (+/-6) | 29 (+/-12) | 33 (+/-13) | 37 (+/-14) |

| Seat-belt/Helmet n/%(n/%) | 7 (13%) | 18 (31%) | 12 (50%) | 9 (75%) | 8 (33%) | 11 (35%) | 21 (57%) | 16 (89%) |

| Scales | ||||||||

| •GCS | 5 (3-9) | 8 (5-12) | 7 (3-14) | 6 (4-15) | 4 (3-10) | 6 (3-11) | 7 (3-13) | 11 (6-15) |

| •IIS | 34 (24-50) | 30 (19-38) | 26 (20-34) | 34 (26-36) | 29 (22-42) | 26 (20-36) | 28 (22-24) | 27 (18-34) |

| •NISS | 36 (25-50) | 34 (25-43) | 29 (26-41) | 34 (29-41) | 38 (25-47) | 31 (25-41) | 29 (22-37) | 29 (22-34) |

| Mortality | ||||||||

| •Total | 17 (32%) | 18 (33%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (33%) | 5 (20%) | 9 (30%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (11%) |

| •On arrival | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| •CNS injury | 13 (24%) | 13 (24%) | 4 (16%) | 4 (33%) | 3 (12%) | 9 (30%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (11%) |

| PERIODS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| n | 184 | 206 | 191 | 187 |

| TRAUMA SCORES | ||||

| GCS | 3 (3-9) | 8 (3-12) | 7 (3-13) | 11 (6-15) |

| ISS | 34 (25-50) | 27 (17-36) | 25 (19-34) | 25 (16-34) |

| NISS | 41 (29-50) | 32 (22-41) | 29 (24-38) | 29 (22-38) |

| INJURY DISTRIBUTION PER REGION (AIS) | ||||

| Head | 5 (4-5) | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-5) |

| Face | 0 | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Thorax | 3 (0-4) | 3 (0-4) | 1 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) |

| Abdomen | 0 (0-2) | 0 | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Extremities | 2 (0-3) | 2 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) |

| Skin | 0 | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | 0 |

| INITIAL SURGERIES | ||||

| Chest tube | 43 (23%) | 44 (21%) | 39 (20%) | 43 (23%) |

| Emergent surgery | 95 (52%) | 114 (55%) | 99 (52%) | 80 (43%) |

| Neurosurgery | 27(15%) | 58 (28) | 57 (30%) | 34 (18%) |

| ICU ADMITTANCE | ||||

| ICU | 146 (79%) | 181 (88%) | 167 (87%) | 147 (79%) |

| MORTALITY | ||||

| Total | 75 (41%) | 73 (35%) | 58 (30%) | 57 (30%) |

| On arrival | 29 (16%) | 10 (5%) | 15 (8%) | 10 (5%) |

| First day | 61 (33%) | 53 (26%) | 26 (14%) | 27 (14%) |

| CAUSE OF DEATH | ||||

| CNS injury | 52 (28%) | 61 (30%) | 47 (25%) | 52 (28%) |

| Exsanguination | 9 (5%) | 14 (7%) | 14 (7%) | 3 (2%) |

| Sepsis | 2 (1%) | 6 3%) | 4 (2%) | 1 (0,5%) |

| Multiorgan failure | 3 (2%) | 8 (4%) | 1 (0,5%) | 1 (0,5%) |

| Cardio-respiratory | 2 (1%) | 8 (4%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (2%) |

| Distributive shock | 1 (0,5%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 |

| VARIABLE | p | HR | CI 95% |

| PATIENTS | |||

| Advanced age | <0,001 | 1,01 | 1,004 - 1,016 |

| Period 4 | <0,001 | 0,806 | 0,717 - 0,906 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0,017 | 1,977 | 1,128 - 3,463 |

| TYPE OF TRAUMA | |||

| Penetrating trauma | <0,004 | 2,118 | 1,276 - 3,517 |

| Motorcycle RTA | <0,001 | 0,457 | 0,289 - 0,721 |

| Fall from height | 0,005 | 1,458 | 1,124 - 1,892 |

| Fire weapon | <0,001 | 2,549 | 1,457 - 4,457 |

| INITIAL ASSISTANCE | |||

| Intubation | <0,001 | 2,677 | 1,950 - 3,674 |

| CPR | <0,001 | 6,323 | 4,344 - 9,202 |

| Initial Shock | <0,001 | 2,808 | 2,161 - 3,648 |

| Fixed pupil | <0,001 | 2,851 | 2,180 - 3,728 |

| GCS | <0,001 | 0,82 | 0,790 - 0,851 |

| Normal systolic pressure | <0,001 | 0,988 | 0,984 - 0,991 |

| ISS | <0,001 | 1,055 | 1,045 - 1,064 |

| NISS | <0,001 | 1,058 | 1,049 - 1,067 |

| INITIAL SURGERY | |||

| Chest tube | <0,001 | 1,544 | 1,185 - 2,011 |

| Emergent surgery | <0,001 | 0,394 | 0,303 - 0,511 |

| Limb surgery | <0,001 | 0,133 | 0,071 - 0,252 |

| Abdominal surgery | 0,002 | 1,785 | 1,231 - 2,588 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).