Introduction

Subway systems play a vital role in urban transportation across the United States, supporting the daily commutes of millions. However, subway-related injuries (SRIs) present a significant public health concern, especially in densely populated cities like New York City (NYC), where the subway system transported 2,027,286,000 passengers in 2023 [

1]. From 1990 to 2003, NYC recorded over 668 fatalities related to subway incidents, with numerous injuries leading to severe trauma, such as extremity fractures and amputations [2-4]. As subways continue to serve as a vital mode of transportation for millions, accidents within these systems result in a wide variety of traumatic injuries that demand specialized medical attention. The complexity of these injuries, ranging from severe head trauma to intricate fractures, often requires coordinated efforts across multiple clinical disciplines, especially in high-level trauma centers.

Injury patterns commonly observed in subway accidents often include traumatic brain injuries (TBI), such as subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), epidural hemorrhage (EDH), and subdural hemorrhage (SDH), all of which carry the potential for long-term neurological deficits [5-8]. Fractures of facial bones, ribs, and the skull base also occur frequently, further complicating patient outcomes. Additionally, soft tissue injuries such as lacerations of the scalp and lung contusions, alongside serious conditions like traumatic pneumothorax, highlight the broad scope of trauma experienced by subway accident victims [5-8]. These patterns emphasize the critical role of trauma centers in not only treating these injuries but also in collecting and analyzing data to inform future prevention and treatment strategies.

Research indicates that the most common isolated severe injury was in the lower extremity, and the most common combinations of severe injuries were in the head and lower extremity, and head and thorax [

9]. Furthermore, Lin and Gill examined subway-related fatalities in NYC between the years 2003 and 2007. They found rates of head injury, torso injury, and amputation of 88%, 76%, and 33%, respectively [

10]. A study conducted at Bellevue Hospital in New York revealed that from a patient pool of 254, 17 were from suicide, 3 were from assault, 49 were hit by a train, and 44 fell onto the tracks [

11]. This study expanded on the type and location of injuries.

Despite the growing recognition of subway-related trauma, the body of research on clinical outcomes and injury patterns remains sparse. Studies focusing on the mechanisms and consequences of such accidents are crucial for improving patient care, enhancing trauma system readiness, and guiding public health interventions aimed at reducing the incidence and severity of these events. By delving into the specific injury patterns seen in subway-related incidents, particularly within the context of a level 1 trauma center, this study seeks to expand the current understanding of these complex cases and that of the development of more effective clinical outcomes.

Methods

This is a single-center, retrospective study of patients with subway-related trauma between January 1, 2016- December 31, 2023, inclusive. Protected Health Information (PHI) was requested from the National Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (NTRACS) trauma data registry. Patients were identified based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) injury description and AIS body region. The severity of traumatic injuries was determined using the Injury Severity Score (ISS) method. The Abbreviated Injury Severity (AIS) regions for patients were also evaluated, with regions of interest being head, face, neck, thorax, abdomen, spine, upper extremity, lower extremity, and external injuries. Furthermore, the mechanisms of injury were studied: Assault, Fall, Suicide, and Train struck. The types of subway-related trauma were analyzed under the mechanisms of injury. The types of subway-related trauma include the sum of facial fractures, vertebral fractures, SAH, SDH, Skull, Solid Organ Injury, Traumatic thoracic injuries, EDH, Hand/Foot fractures, Abdominal Injury, and diffuse TBI. Also, gender, race, age, and ethnicity data were collected under the mechanisms of injury. Furthermore, the clinical outcomes were collected under the mechanisms of injury. The clinical outcomes include Discharge Home/Shelter, Hospice, Inpatient Psychiatry Care, Left Against Medical Advice, Met brain death criteria, Mortality, Other Acute Care Hospital Emergency Department (ED) or, Police Custody/Jail/Prison, Skilled Nursing Facility, and Sub Acute Rehabilitation / Inpatient Rehabilitation.

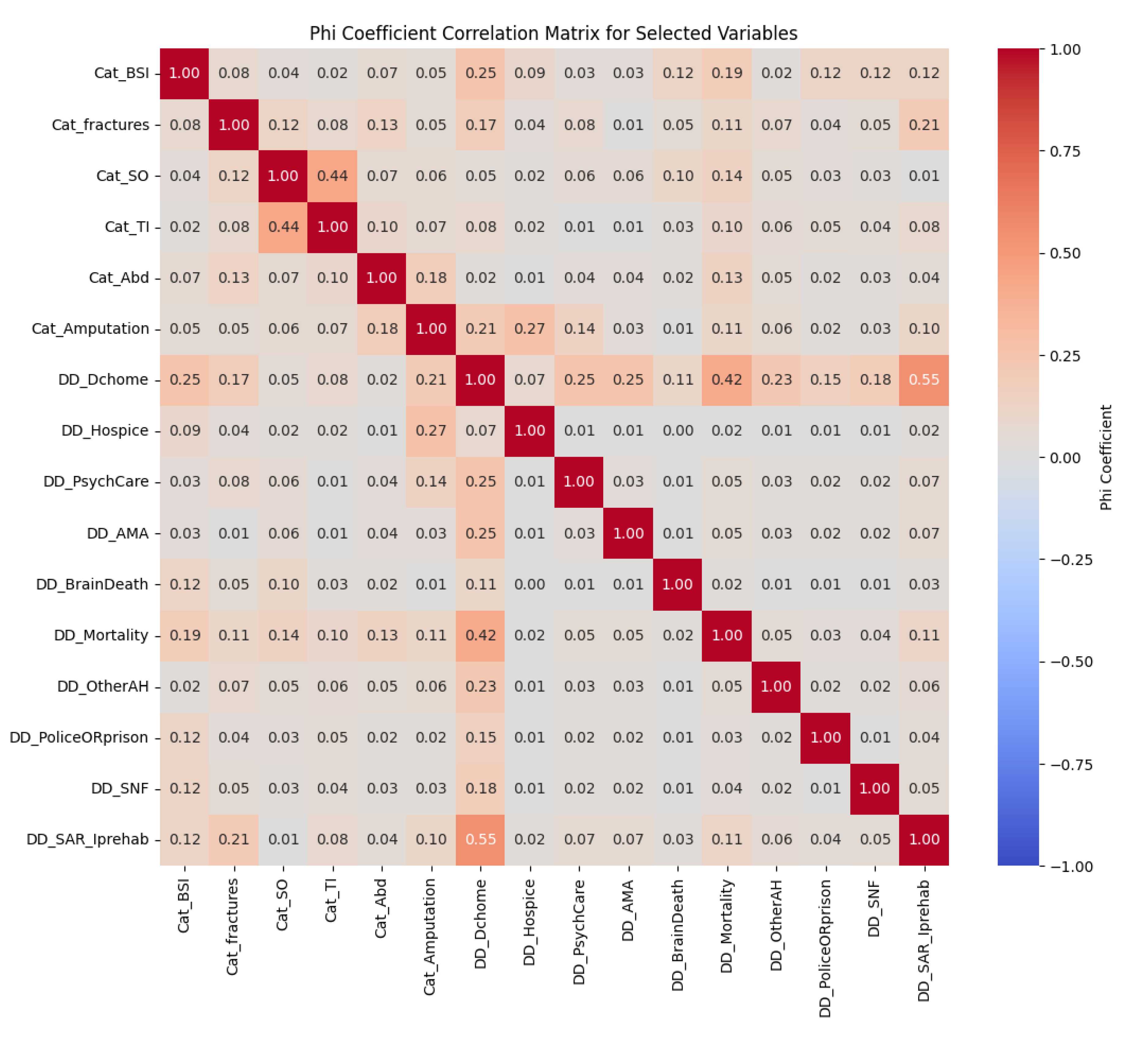

In this study, we used the Phi coefficient correlation matrix to examine relationships between trauma injury patterns associated with subway trauma and clinical outcomes based on discharge disposition. Injury trends and discharge outcomes, such as discharge to a skilled nursing facility, home, subacute rehabilitation, and hospice, were abstracted for the electronic medical record. First, we evaluated connections using the Chi-Square test. However, this approach was limited by assumptions that were not met, such as the mutual exclusion of some discharge dispositions and low predicted frequencies in some cells. We recorded all variables as binary indicators to better capture associations and computed Phi coefficients for every pair. A heatmap displayed the results, highlighting important connections between injury trends and discharge outcomes that can guide post-discharge care and resource allocation.

Results

The occurrence of injuries by body region with an AIS score of three or greater, which is considered a severe traumatic injury per trauma patient, was evaluated.

Table 1 represents common combinations of severe injuries per body region. The head region is the highest, followed by thorax region injuries and lower extremity injuries.

Table 1 of this paper presents the distribution of trauma types (blunt, burn, and penetrating) among subway-related injury cases. A total of 360 cases were included. Blunt trauma accounted for the majority of cases (93.9%), while penetrating trauma represented 5.8%, and burn injuries made up 0.3%.

The distribution of the ISS provides insights into the frequency of injuries based on their severity levels within the study population. Overall, the mean ISS of 10.69, with a standard deviation of 11.33, suggests a broad range of traumatic injuries. Most patients (suffered from minor injuries, the ISS of which is between 1 and 9. In total, these patients constitute 60.8% (219 cases). Meanwhile, around 17.5% (63 cases) were observed with moderate injuries, the ISS score between 10 and 16. Severe injuries (the ISS of 17-24) comprised 9.2% of the study cohort (33 cases).

Table 2 of this paper presents the demographic breakdown of subway-related trauma cases based on different mechanisms of injury (MOI), including falls, assaults, train strikes, suicides, and other causes (such as electric injuries, strikes against objects, and other unspecified injuries). Age is reported as the mean and standard deviation, while gender, race, and ethnicity are displayed as counts and percentages. The data show that individuals involved in falls had an average age of 52.51 years, the oldest among the groups, while those in the "other" injury category had the youngest average age (33.62 years). Males were the predominant gender in all MOI categories, with the highest percentage in the assault category (92.60%). Regarding race, the majority of patients across most MOI groups were classified as "Other," with the highest proportion observed in the assault category (74.10%). The ethnicity data reveal that Hispanic origin was most common in the assault group (64.80%). This demographic information helps to contextualize the characteristics of patients based on their injury mechanisms.

Table 3 of this paper outlines the injury patterns associated with various MOI in subway-related trauma incidents, specifically focusing on assaults, falls, other causes (such as electric injuries and being struck against objects), suicides, and train strikes. The table provides counts and percentages for different types of injuries, including brain-specific injuries, fractures, solid organ injuries, traumatic thoracic injuries, abdominal injuries, and traumatic amputations.

Notably, falls accounted for the highest percentage of brain-specific injuries (65.60%) and fractures (67.50%), indicating their prevalence in this MOI. Assaults showed a significant occurrence of traumatic thoracic injuries, with 28.90% of cases reporting these injuries. Suicide attempts demonstrated a high percentage of traumatic amputations (30.80%), indicating a unique pattern in injury presentation. Overall, this data highlights the diverse injury patterns associated with different MOI, emphasizing the need for tailored clinical approaches for each category.

Table 4 of this paper summarizes the clinical outcomes for trauma patients categorized by their MOI, including assault, falls, other injuries (such as electrical or blunt force), suicides, and train-related incidents. It presents the frequency and percentage of various dispositions, illustrating the diverse trajectories patients experience following trauma.

The data reveals significant variations in outcomes across different injury mechanisms. For instance, a substantial percentage of patients from fall incidents (72.50%) were discharged home or to shelters, while only 1.30% of patients from assault and suicide incidents experienced similar outcomes. The mortality rate was notably high among suicide victims (37.90%), indicating the severity of injuries in this category. Other clinical outcomes include transfers to inpatient psychiatric care, skilled nursing facilities, and rehabilitation services, reflecting the multifaceted needs of trauma patients. This table highlights the critical role of targeted interventions and the necessity for tailored care pathways based on the MOI.

Table 5 of this paper presents the distribution of ED dispositions among patients involved in trauma cases. It details the frequency and percentage of various outcomes, including admissions, fatalities in the ED, deaths on arrival, deaths within 15 minutes, routine discharges to home or self-care, and transfers to other hospital ED.

The majority of patients (69.4%) were admitted for further care, while a smaller percentage experienced fatal outcomes, with 0.5% dying in the ED, 0.5% dying on arrival, and 1.04% dying within 15 minutes of arrival. Routine discharges accounted for 18.54% of the cases, indicating that a significant number of patients were stabilized and released. The data underscores the critical role of the ED in managing trauma cases, highlighting both the successful admissions and the challenges faced in life-threatening situations.

Figure 1 of this paper represents the Phi coefficient correlation matrix for injury patterns and hospital disposition in subway-related trauma. The Phi coefficient correlation matrix provides valuable insights into associations between various binary clinical outcomes, informing patient care planning and resource allocation. Although discharge to home and discharge to subacute rehab are theoretically mutually exclusive options. Trauma patients are usually discharged to either one or the other, not both. A high correlation is observed between these two variables. Positive correlations were found between Thoracic injury patterns and Solid organ injuries, with a coefficient of 0.44, suggesting that patients with Thoracic injuries are moderately likely associated with solid organ injuries. This association aligns with clinical expectations, where thoracic injuries often involve solid organs.

Additionally, other meaningful associations were observed. There was a moderate positive correlation between amputation and discharge to hospice care (0.27), indicating that patients who undergo amputation may often be dealing with severe or end-of-life conditions and poor prognosis, underscoring the importance of hospice care planning for these patients. Negative associations were also notable, particularly between discharge to home and both mortality (-0.42). These associations imply that patients discharged to home are generally in more stable conditions. Many other variable pairs showed weak or minimal correlations, such as solid organ injury patterns and psychiatric care discharge disposition outcomes, indicating that these factors may operate independently in this dataset.

Overall, the correlation matrix highlights expected clinical patterns, such as the relationship between discharge destinations and patient stability, while also revealing the importance of how data is coded, especially for mutually exclusive outcomes like discharge to home and rehab. This correlation analysis allows clinicians to better anticipate patient needs post-discharge and make informed decisions about resource allocation.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the injury patterns and clinical outcomes resulting from subway-related accidents, a critical area of research given the vast number of passengers utilizing urban transportation systems daily. With the ongoing advancements in subway infrastructure, the incidence of SRIs has notably increased, making it essential to understand the mechanisms, demographics, and clinical outcomes involved in these injuries.

Our findings indicate a significant prevalence of traumatic head injuries, specifically SAH, EDH, and SDH, which accounted for a cumulative total of 78 cases among the 360 patients studied. Head injuries are particularly concerning, as they often result in long-term neurological deficits and complications.

Furthermore, the percentage of patients presenting with an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) score ≥ 3 in the head region (23%) does not reflect the percentage of patients with severe head injuries (12%) from a 2020 Canadian Study [

12]. The percentage of patients presenting with (AIS) score ≥ 3 in the thorax region (16%) is also reflective of the percentage of patients with severe thorax injuries (8%) from the same 2020 study. Conversely, both studies report a similar prevalence of severe lower extremity injuries at 14%, underscoring a shared concern regarding these types of injuries across different populations. These findings underscore the need for a nuanced understanding of injury severity assessments and their implications for clinical outcomes and management strategies in trauma care.

Moreover, the study reveals that blunt trauma constituted the majority of cases (93.99%), with only 5.74% categorized as penetrating trauma. This pattern is consistent with previous research indicating that most SRIs arise from blunt forces associated with falls, collisions, or being struck by a train. In a 2009 study, a majority of cases were classified as blunt trauma (98%) [

12]. The findings of a median ISS of 8, with an interquartile range of 10, indicate a broad range of injury severity, further reinforcing the necessity for trauma centers to be equipped to handle complex cases.

Our study reveals significant differences in the mechanisms and types of injuries sustained across various contexts: assault, fall, suicide, train strike, and other injury types. Notably, brain-specific injuries were most prevalent among fall cases, comprising 65.60% of all instances. This contrasts sharply with assault cases, where only 4.20% of injuries were brain-specific. Brain-specific injuries include SAH, EDH, SDH, Diffused TBI, and other intracranial injuries. Comparing this to the Bellevue Hospital study, they classified inter-cranial hemorrhage injury with 27% of patients [

11]. Even though the study does not specify the MOI, it can be inferred that most of this data are from falling and train strikes because 49% and 44% of the patient population were classified as hit by a train and falling onto tracks, respectively. Furthermore, our study exhibits that fractures were predominantly associated with falls (67.50%), aligning with the Bellevue Hospital study data that indicates a 49% incidence of at least one fracture among patients [

11]. To elaborate, both studies show that the most prevalent types of fractures are facial and vertebral fractures. Conversely, solid organ injuries were primarily observed in fall cases (65.70%) and somewhat in assault cases (8.60%). This distribution mirrors the Bellevue Hospital study’s indication of a 17% solid organ injury rate, highlighting the necessity for further investigation into the underlying causes and mechanisms that contribute to such injuries in different contexts [

11]. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of understanding the relationship between injury mechanisms and clinical outcomes to inform effective prevention strategies.

When comparing our study's demographics with a 2009 study’s data, there are some key differences in age, gender, race, and ethnicity [

10]. The 2009 study does not specify the MOI. The mean age for falls in our study is higher (52.51 years) compared to other injuries like assaults (37.89 years), while the 2009 study does not provide age specifics. Racial and ethnic patterns differ notably. In our study, a majority of patients in falls and assaults belong to "Other" races (50.40% and 74.10%, respectively), whereas Caucasians dominate in the 2009 study (32%) [

10]. Hispanic patients are more prevalent in assault cases in our study (64.80%) compared to the 2009 study (28%) [

10]. These differences likely reflect regional variations and suggest the importance of tailoring injury prevention strategies to local demographics.

In our study, the frequency of traumatic amputations varies across injury mechanisms, with falls and train strikes accounting for the highest percentages of amputations (23.10% and 30.80%, respectively). Assaults, suicides, and other injury types contribute smaller portions, with 7.70% each. The majority of these amputations are lower extremity amputations.

According to Maclean, et al., their study presents more detailed classifications of amputation types, with the majority being lower extremity amputations, particularly below the knee (11 unilateral cases and 3 bilateral) [

12]. Upper extremity amputations and mixed upper and lower extremity amputations are less common [

13]. There are also a few cases of conversion from below-knee to above-knee amputations, highlighting the progression of injury severity in some patients.

While both datasets emphasize the prevalence of lower extremity amputations, the Maclean study provides more specificity regarding the level and type of amputation. Our study's broad categorization does not capture the nuanced patterns of injury severity and progression reflected in the comparison study's data.

The clinical outcomes in our study highlight the severity and complexity of trauma care. Among the 360 patients, a significant number required surgical interventions, such as craniotomies and orthopedic surgeries, emphasizing the severity of the injuries sustained. Despite this, the overall mortality rate remained relatively low, particularly among fall patients (17.20% mortality) compared to the higher rates observed in the suicide and train-struck groups (37.90% each). This suggests that timely and effective trauma care likely contributed to the favorable outcomes observed in many patients, with a large proportion of fall patients (72.5%) being discharged home or to a shelter.

In contrast, a 1987 London Underground study provided less detail on surgical interventions but showed several patients admitted to intensive care, neurosurgical wards, and psychiatric units, with some dying within hours of their injuries [

13]. The 1987 study, while lacking percentage breakdowns, highlights the immediate critical outcomes: 23 patients were admitted to psychiatric units, and 14 to general hospital wards [

13]. Deaths were relatively rare but significant, with 4 patients dying in the accident and ED within 4 hours, and others dying in various units like the operating theater and ICU [

13].

Additionally, a more recent study reviewed subway-related injury cases, revealing a mortality rate of 9.6% and that 25% of patients suffered extremity amputations, highlighting the severe nature of these injuries [14-16]. Of the survivors, 35.4% required transfer to psychiatric or rehabilitation services, with the remaining 53.4% discharged, aligning with the trends observed in our study regarding the need for extensive rehabilitation and psychiatric care [

14]. This data further emphasizes the importance of addressing long-term outcomes in subway-related trauma, including psychological and rehabilitative care, as many survivors face ongoing physical and cognitive challenges.

Gender trends are consistent across multiple studies, with males dominating in traumatic injuries—74.40% for falls and 92.60% for assaults in our study, similar to the 2009 study's 83% male rate. However, the 2009 study reports a higher percentage of female patients overall (52.6%), particularly compared to the 25.60% for falls in our study [10, 17-19]. This recurring gender pattern is not only associated with subway injuries but also with associated with road injuries [20-22], stab wounds [23-25], and gunshots [

24].

Comparing the two, our study shows a broader range of clinical outcomes, including long-term care needs like rehabilitation, which were less detailed in the 1987 study. Many survivors, particularly those in our cohort who were discharged to rehabilitation or psychiatric care, may face ongoing challenges with physical and cognitive functioning. This echoes the broader need for attention to long-term outcomes, which remain underexplored in both our data and the comparison study.

A limitation of this study is the potential misinterpretation from recoding categorical variables, especially for outcomes like discharge disposition and injury patterns. When mutually exclusive outcomes are recoded into binary indicators, unintended correlations may appear, as both categories can be flagged as “positive,” inflating associations. Similarly, recoding injury patterns into binary categories can oversimplify clinical nuances, masking important distinctions. This limitation highlights the need for careful data coding to ensure that exclusive and clinically distinct outcomes are accurately represented in future studies.

While this study provides valuable insights into the injury patterns and clinical outcomes resulting from subway-related accidents, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, as a single-center retrospective study, the findings may not be generalizable to other trauma centers or urban settings. The patient population treated at one trauma center may not capture the full spectrum of SRIs across different regions or hospitals. This limits the broader applicability of the results.

Our study's reliance on ICD injury descriptions and AIS body region classifications introduces the potential for bias. Differences in coding practices and documentation quality across clinicians can affect data accuracy, making it difficult to standardize injury descriptions or severity levels across all cases. Moreover, the retrospective nature of the study prevents the establishment of causal relationships between injury mechanisms and clinical outcomes, as it only captures information available in medical records.

Another limitation is the possibility of underreporting of cases, particularly for patients with less severe injuries who may not seek immediate medical attention or those whose injuries were not documented due to inconsistent reporting practices. Therefore, the true incidence of SRIs is likely underestimated.

Finally, although our study provides valuable data on immediate clinical outcomes, it does not address the long-term consequences or complications of these injuries. Understanding the long-term impact on survivors’ quality of life, cognitive functioning, and healthcare utilization would offer a more comprehensive picture of subway-related trauma.

Strengths

Despite these limitations, our study possesses several significant strengths. One key strength is the inclusion of clinical outcome data, which sets it apart from many prior studies that focused only on injury patterns. Our data reveal important clinical outcomes such as discharge destinations, mortality rates, and the need for rehabilitation, offering a holistic view of patient recovery and post-trauma needs. The comprehensive inclusion of surgical interventions such as craniotomies and orthopedic procedures further underscores the severity of injuries and the importance of trauma care in improving patient outcomes.

The large sample size of 360 patients enhances the statistical power of the study, allowing for a more nuanced analysis of the different injury mechanisms (assault, fall, suicide, train-struck, etc.) and their associated clinical outcomes. By exploring various injury types, the study provides valuable insights that can inform targeted prevention strategies and injury management protocols.

Additionally, the detailed demographic analysis, which covers age, gender, race, and ethnicity, is crucial for understanding how different populations are affected by subway-related trauma. This analysis is particularly important for tailoring public health interventions to vulnerable groups. Moreover, the study's multidimensional approach, which examines a broad range of injury mechanisms, offers critical insights into how different accidents contribute to SRIs.

Finally, the ability to compare clinical outcomes, such as discharge destinations and mortality rates, with historical studies like the 1987 London Underground study adds a valuable dimension of context. This comparison allows for a deeper understanding of the evolving nature of trauma care and highlights the differences in clinical care and injury outcomes over time.

Limitations

Data was collected from the NTRACS Trauma Registry, which may not always provide complete or detailed information. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. A multicenter study incorporating all emergency medical services’ data would provide a more accurate description of the injuries. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of the study and reliance on available medical records may introduce biases. The study does not consider potential confounding variables, such as patient comorbidities, trauma severity scoring variations, or treatment protocol differences that could impact outcomes. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to establish causal relationships between trauma characteristics and outcomes. Future studies should aim to include multi-center data and explore strategies to address trauma management-related quality issues related to prolonged length of stay of trauma patients, especially the ICU LOS and HLOS. These limitations suggest that further research, incorporating more comprehensive and geographically diverse data, is necessary to fully understand the epidemiology of SRIs in urban settings.