1. Introduction

Multiple trauma is defined as injuries involving at least two of the following regions: the head and neck, thorax, abdomen, or extremities. Alternatively, it can be defined as fractures of at least two long bones [

1]. Various scoring systems, such as the Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), are utilized to assess the severity of injuries in trauma patients [

2]. Each scoring system has its strengths and limitations. For instance, the ISS is calculated by summing the squares of the highest AIS values from the three most severely injured body regions; it considers only one injury per region, which may limit its clinical applicability [

3,

4]. Moreover, despite similar scores across different body regions, variations in mortality rates and hospital stay durations can occur [

4].

The Revised Trauma Score (RTS) is a physiological scoring system that utilizes easily measurable parameters such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), systolic blood pressure, and respiratory rate, enabling the rapid assessment of trauma patients, particularly in emergency departments. Its advantage lies in its quick applicability, aiding in the prioritization of critically injured patients. However, compared to anatomical scoring systems, the RTS may have limitations in predicting long-term outcomes [

5].

Numerous studies have evaluated the relationship between trauma scores and mortality. For instance, a study conducted in South Korea demonstrated that higher NISS values are significantly associated with longer hospital stays [

3]. Similarly, research on the APACHE II score has revealed a statistically significant correlation between its value and mortality in trauma patients receiving intensive care [

6]. Although the literature presents extensive studies on the impact of trauma scores on mortality [

7,

8,

9,

10], the majority have been conducted in intensive care units or trauma centers. Our study distinguishes itself by being emergency department-based, encompassing a broader patient population, and evaluating multiple trauma scoring systems.

In this research, we calculated the ISS, NISS, AIS, GCS, RTS, and APACHE II values for multiple-trauma patients admitted to the emergency department due to traffic accidents. We assessed the effectiveness of these scores in predicting mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted between April 1, 2022, and April 1, 2023, at the Emergency Department of XXXXXXXX University XXXXX Training and Research Hospital. We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of various trauma scoring systems (ISS, NISS, AIS, GCS, RTS, and APACHE II) in predicting mortality in patients presenting with traffic accident-related multiple trauma. Ethical approval was obtained from the XXXXXXX Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Decision No: 2022/05-10, Date: 20.04.2022).

2.2. Participants

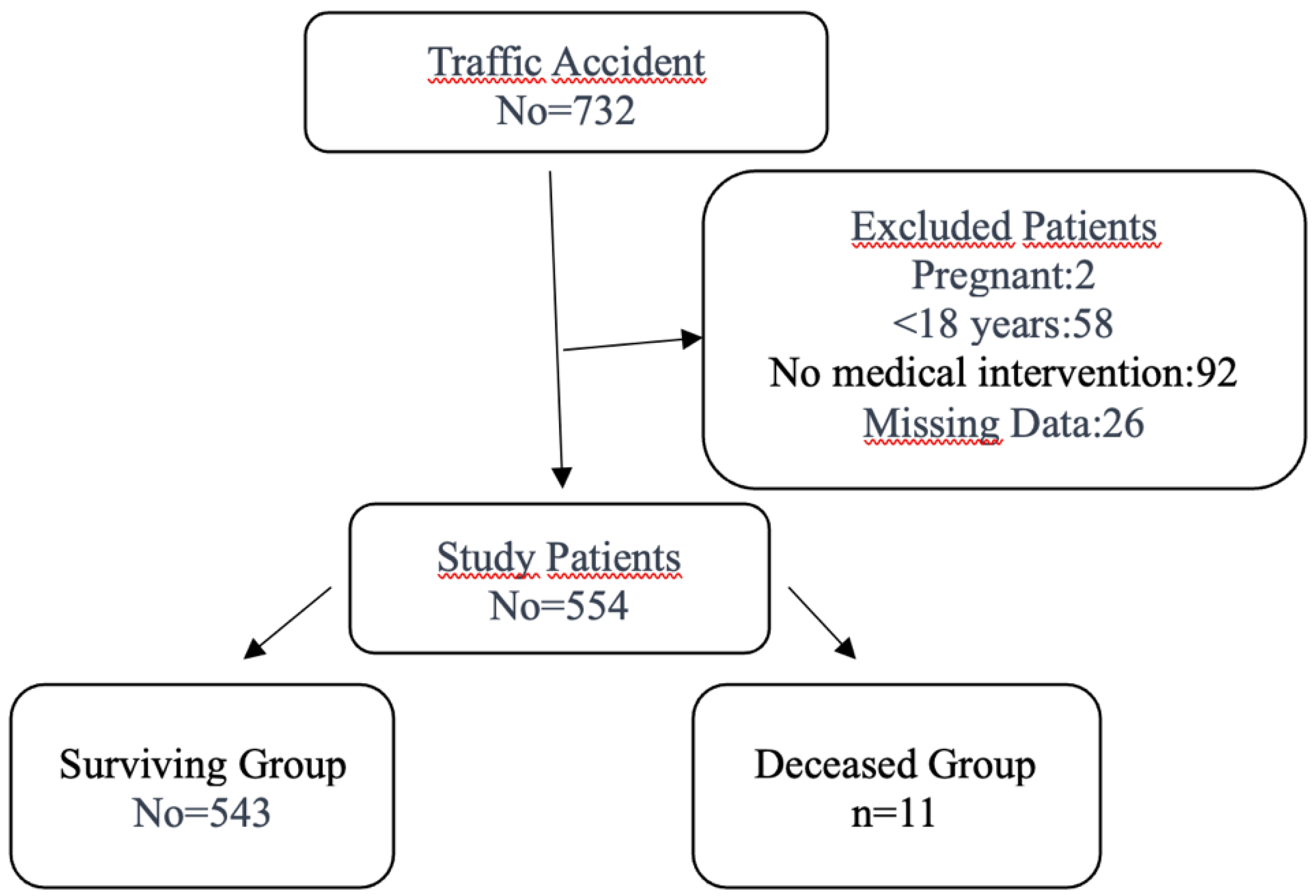

Patients aged 18 years and older who presented to the emergency department with multiple trauma caused by traffic accident-related injuries were included in the study. The exclusion criteria encompassed patients younger than 18 years and those with isolated injuries requiring no medical intervention. Out of 732 patients evaluated after traffic accidents, 178 were excluded: 2 due to pregnancy, 58 because they were under 18 years of age, 92 because they required no medical intervention, and 26 due to incomplete or missing data. A total of 554 patients were enrolled. To ensure a representative sample and minimize selection bias, patients were consecutively recruited during the study period. The patient selection process is summarized in the flow diagram (

Figure 1).

2.3. Variables

The primary variables of interest included the results of trauma scoring systems (ISS, NISS, AIS, GCS, RTS, and APACHE II), mortality outcomes, and patient demographic characteristics (age and gender). The secondary variables included the presence of comorbid chronic diseases. Additionally, laboratory parameters were collected to explore their potential association with mortality.

2.4. Data Sources and Measurement

Trauma scores were calculated at the time of the patients' initial presentation. Anatomical scores (ISS, NISS, and AIS) were determined using the AIS 15 guide, based on the most severe injuries recorded for each patient. Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the hospital's electronic health record system to ensure accuracy and completeness.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Quantitative variables with a normal distribution are expressed as means ± standard deviations, while those without normal distribution are presented as medians (interquartile ranges: IQRs). Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were conducted using Student's t-test for normally distributed quantitative variables, the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed quantitative variables, and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between the trauma scoring systems. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of Patients

A total of 554 patients were included in the analysis, comprising 374 males (67.5%) and 180 females (32.5%). The median age of the cohort was 36 years (interquartile range: 25–54 years). Comorbidities were documented in 45 patients (8.1%), with hypertension and diabetes mellitus being the most reported conditions. The most frequently observed trauma types were extremity injuries (61.7%), followed by head and neck trauma (44%), thoracic trauma (29.9%), and abdominal trauma (16.6%). The detailed demographic characteristics and trauma-related findings are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Laboratory Findings and Trauma Scoring Systems

The comparative analysis revealed significant differences in the laboratory parameters between the deceased and surviving groups. The deceased group had significantly higher median values for the white blood cell (WBC) count and creatinine, and significantly lower values for the hematocrit and bicarbonate levels. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for the sodium and potassium levels. These findings highlight specific physiological markers that may be associated with poorer outcomes (

Table 2).

Similarly, significant differences were noted in the trauma scoring system results between the two groups. The deceased group exhibited significantly higher median scores for the APACHE II, AIS, ISS, and NISS systems, whereas significantly lower median scores were recorded for the RTS and GCS. These results suggest that higher scores in anatomical and physiological scoring systems are strongly associated with increased mortality risk. Detailed comparisons of the trauma scores between the two groups are provided in

Table 3.

3.3. Correlations Among Trauma Scoring Systems

The correlation analysis demonstrated a perfect positive correlation between the ISS and NISS values (Spearman’s Rho = 0.97, p < 0.001). The AIS values also showed very high positive correlations with both the ISS (Spearman’s Rho = 0.88, p < 0.001) and NISS (Spearman’s Rho = 0.87, p < 0.001), indicating a strong internal consistency between the anatomical scoring systems and underscoring their potential interchangeability in evaluating trauma severity. Additionally, APACHE II exhibited moderate positive correlations with the ISS (Rho = 0.24, p < 0.001), NISS (Rho = 0.23, p < 0.001), and AIS (Rho = 0.27, p < 0.001), reflecting its capability to capture injury severity through combined physiological and laboratory parameters. In contrast, the RTS was negatively correlated with all of the anatomical scores, particularly the ISS (Rho = –0.32, p < 0.001) and NISS (Rho = –0.31, p < 0.001), which is consistent with its inverse scoring direction in relation to severity. These findings highlight the complementary roles of anatomical and physiological scoring systems in trauma evaluation. The correlation coefficients for all trauma scoring systems are summarized in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

Traumas, especially traffic accidents, remain a leading cause of global mortality. In 2016 alone, traffic accidents caused 1.35 million deaths [

11]. Studies suggest that road traffic accidents are the eighth most common cause of death globally, and could potentially rise to the fifth position by 2030 [

11]. These alarming trends highlight the potential for road traffic injuries to become a global pandemic, necessitating robust systems for managing injury severity.

Anatomical and physiological scoring systems, such as the ISS, NISS, AIS, RTS, and GCS, are widely used for trauma assessment. Combined methods like the Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) enhance the predictive accuracy by integrating anatomical and physiological metrics. Each system has strengths and limitations. For example, the NISS provides more precise evaluations of patients with multiple severe injuries in the same anatomical region, while the RTS is rapid but has limitations, especially in pre-hospital settings. These disparities highlight the ongoing need for an ideal scoring system that balances accuracy, practicality, and applicability across diverse clinical scenarios.

Our study aligns with the literature while revealing unique observations. Male patients (67.5%) predominated, consistent with the higher traffic accident involvement among men due to increased exposure and risk-taking behaviors. The median age (36 years) aligns with global data on young and middle-aged adults. Notably, only 8.1% had comorbid conditions, lower than the figure reported in other studies, possibly due to socioeconomic and cultural variations.

Extremity injuries (61.7%) were the most common trauma type in our cohort, followed by head and neck injuries (44%), thoracic injuries (29.9%), and abdominal injuries (16.6%). These findings align with several studies reporting extremity injuries as the most frequent trauma site [

18]. However, other studies, such as a 9-year retrospective analysis by Noora K. et al., have identified thoracic and head–neck injuries as the most prevalent [

2]. These differences may be attributed to variations in vehicle types, injury mechanisms, and the use of protective equipment across regions. Moreover, the inclusion of minor injuries in our study, irrespective of severity, may have influenced the frequency distribution of trauma types. Similarly, Kenarangi et al. evaluated nearly 48,000 traffic accident injuries and reported that motorcycle-related incidents were the leading cause of trauma, predominantly affecting male patients, which may explain the high frequency of extremity injuries in both studies [

19].

The observed mortality rate of 2% in our study is notably lower than rates reported in studies focusing on intensive care unit (ICU) patients [

20]. This can be explained by our inclusion of patients treated in the emergency department, including those managed on an outpatient basis. This broader patient spectrum reflects the unique focus of our study on early-stage trauma evaluation and highlights differences in mortality rates based on patient selection criteria.

4.1. Laboratory Parameters and Trauma Scoring Systems

The laboratory findings in our study revealed significant differences between the deceased and surviving groups for the WBC count, hematocrit (Htc), creatinine, and bicarbonate levels. These parameters are integral to scoring systems such as APACHE II, which demonstrated a strong association with mortality in our cohort. Similar findings were reported in a prospective study by Shao Chun Wu et al., where the Htc, creatinine, and bicarbonate levels were significant predictors of mortality, while the sodium and potassium levels showed no such association [

21]. However, some studies suggest that the Htc levels are not always associated with mortality, reflecting variability between patient populations and study methodologies [

22].

The results of our study demonstrated strong correlations between the anatomical scoring systems, with the ISS and NISS showing a near-perfect positive correlation (Spearman’s Rho = 0.97, p < 0.001). The AIS also showed very high correlations with both the ISS (Spearman’s Rho = 0.88, p < 0.001) and NISS (Spearman’s Rho = 0.87, p < 0.001), further validating their reliability. These findings are consistent with Orhon et al., who reported a high predictive accuracy for the ISS and NISS in trauma severity evaluation [

9]. Unlike Orhon et al., who relied on retrospective data, our prospective approach allowed for a more accurate assessment of the initial injury severity before treatment interventions.

The APACHE II scores were significantly higher in the deceased group, emphasizing its predictive value for mortality. This finding aligns with that of Serviá et al., who reported the utility of APACHE II in ICU patients [

19]. While their study focused on critically ill patients, our inclusion of emergency department patients underscores the versatility of APACHE II in evaluating a broader spectrum of trauma severity. Similarly, the RTS, which was significantly lower in the deceased patients, remains a valuable tool for rapid assessment, as it relies on easily measurable physiological parameters (median RTS: 4.09 vs. 7.84, p < 0.001). These results further corroborate its utility, as highlighted by Orhon et al. [

9].

In a recent study by Gupta et al. involving 240 trauma patients, APACHE II showed the highest accuracy in predicting mortality across time spans from admission, 24, to 48 hours, with an AUC of up to 0.965. It outperformed traditional trauma scores like the RTS and TRISS [

23]. In our cohort of 554 emergency department patients with multiple traffic accident-related trauma, the APACHE II score was significantly higher in the non-survivors. While Gupta et al. reported a moderate predictive value for the ISS, we observed higher ISS and NISS values among the deceased patients (median: 12 vs. 2, p < 0.001) and a strong correlation between them (Rho = 0.97). Interestingly, the RTS had a low predictive capacity in that study but was lower among the non-survivors in our study. The RTS remains relevant in emergency triage.

In our study, higher APACHE II, ISS, NISS, and AIS values and lower RTS and GCS values were significantly associated with mortality in traffic accident patients admitted to the emergency department. Similar findings were reported by Javali et al., where the ISS and NISS values were markedly higher in non-survivors (ISS: 20.85, NISS: 27.65), and the RTS values were lower (RTS: 5.43), with all scores showing an excellent predictive accuracy [

24]. These studies support our finding that trauma scores reflecting both the physiological and anatomical burden can reliably predict mortality, particularly in emergency settings.

Study Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, our single-center design may have limited the generalizability of our findings to other settings with differing patient populations and healthcare resources. Second, the relatively low number of deceased patients could have impacted the statistical power for mortality predictions. Third, the exclusion of pediatric patients and those with isolated injuries restricts the applicability of our findings to a broader trauma population. Future multicenter studies with larger and more diverse cohorts are needed to validate and expand upon these results.

5. Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the utility of multiple trauma scoring systems, including the NISS, ISS, RTS, and APACHE II, in predicting mortality among traffic accident-related trauma patients. Our comparative findings suggest that while the APACHE II score may offer superior accuracy, especially when lab data are available, simpler tools like the RTS still provide essential early risk stratification.

The NISS and ISS showed strong correlations and were effective in reflecting injury severity, while the RTS and APACHE II systems emerged as practical tools for early mortality prediction in emergency settings. Integrating these scoring systems into clinical practice can aid in timely risk stratification and improve decision making. Future research should focus on refining these tools and exploring their applicability in diverse healthcare settings to optimize trauma care globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and M.T.; methodology, M.K. and M.T.; software, H.Y. and M.T.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K. and M.U.; investigation, H.Y. and M.T.; resources, M.T.; data curation, H.Y. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y., M.U., and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.T. and M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, H.Y. and M.K.; project administration, H.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Y. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All authors declared that the research was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects”. This study was approved by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kütahya Health Sciences University (Approval No: 2022/05-10, Date: 20.04.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable since this study was based on medical record review and all of the individuals’ information was not included in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| RTS |

Revised Trauma Score |

| ISS |

Injury Severity Score |

| AIS |

Abbreviated Injury Score |

| NISS |

New Injury Severity Score |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| APACHE II |

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II |

| ED |

Emergency department |

References

- Turculeţ, C.Ş.; Georgescu, T.F.; Iordache, F.; Ene, D.; Gaşpar, B.; Beuran, M. Polytrauma: The European Paradigm. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2021, 116, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airaksinen, N.K.; Handolin, L.E.; Heinänen, M.T. Severe Traffic Injuries in the Helsinki Trauma Registry between 2009–2018. Injury 2020, 51, 2946–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Yun, J.S.; Jung, S.E.; Chae, C.S.; Chung, M.J. Characteristics of patients injured in road traffic accidents according to the New Injury Severity Score. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 40, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aharonson-Daniel, L.; Giveon, A.; Stein, M.; Israel Trauma Group (ITG); Peleg, K. Different AIS triplets: Different mortality predictions in identical ISS and NISS. J. Trauma 2006, 61, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Abe, T.; Kohshi, K. Revised trauma scoring system for estimating in-hospital mortality in the emergency department: Glasgow Coma Scale, Age, and Systolic Blood Pressure Score Critique. Maintenance 2011, 15, R191. [Google Scholar]

- Atik, B.; Kilinc, G.; Yarar, V. Predictive value of prognostic factors at multiple trauma patients in intensive care admission. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2021, 122, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossett, L.A.; Redhage, L.A.; Sawyer, R.G.; May, A.K. Revisiting the validity of APACHE II in the trauma ICU: Improved risk stratification in critically injured adults. Injury 2009, 40, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan Akbari, G.; Mohammadian, A. Comparison of the RTS and ISS scores on prediction of survival chances in multiple trauma patients. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 2012, 79, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhon, R.; Eren, S.H.; Karadayı, S.; Korkmaz, I.; Coşkun, A.; Eren, M.; Katrancıoğlu, N. Comparison of trauma scores for predicting mortality and morbidity on trauma patients. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2014, 20, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höke, M.H.; Usul, E.; Özkan, S. Comparison of Trauma Severity Scores (ISS, NISS, RTS, BIG Score, and TRISS) in Multiple Trauma Patients. J. Trauma Nurs. 2021, 28, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Road Safety Status Report 2018, World Health Organization 2018, Geneva (2022). https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2018/en/.

- Brenneman, F.D.; Boulanger, B.R.; McLellan, B.A.; Redelmeier, D.A. Measuring injury severity: Time for change? J. Trauma 1998, 44, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvagno, S.M., Jr.; Massey, M.; Bouzat, P.; et al. Correlation between the Revised Trauma Score and Injury Severity Score: Implications for prehospital trauma triage. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2019, 23, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, M.R.; Mackenzie, C.F.; DuBose, J.; et al. In predicting post-traumatic mortality, oxygen saturation and heart rate, which are continuously recorded during prehospital transport, outperform the initial measurement. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, T.; Baker, S.P.; Long, W. A modification of the Injury Severity Score that both improves accuracy and simplifies scoring. J. Trauma 1997, 43, 922–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.J.; Huang, X.F.; Xie, F.K.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.H.; Yu, A.Y. Road traffic mortality in Zunyi city, China: A 10-year data analysis (2013-2022). Chin. J. Traumatol. 2025, 28, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenarangi, T.; Rahmani, F.; Yazdani, A.; Ahmadi, G.D.; Lotfi, M.; Khalaj, T.A. Comparison of GAP, R-GAP, and new trauma score (NTS) systems in predicting mortality of traffic accidents that injure hospitals at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, T.; Miller, J.; Shreve, C.; Allenback, G.; Wentz, B. Comparison of injuries among motorcycle, moped and bicycle traffic accident victims. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2022, 23, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenarangi, T.; Rahmani, F.; Yazdani, A.; Ahmadi, G.D.; Lotfi, M.; Khalaj, T.A. Comparison of GAP, R-GAP, and new trauma score (NTS) systems in predicting mortality of traffic accidents that injure hospitals at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e36004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviá, L.; Badia, M.; Montserrat, N.; Trujillano, J. Severity scores in trauma patients admitted to ICU: Physiological and anatomic models. Med. Intensiva (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 43, 26–34.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C.; Chou, S.E.; Liu, H.T.; et al. Performance of prognostic scoring systems in trauma patients in the intensive care unit of a trauma center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baygeldi, S.; Karakose, O.; Özcelik, K.C.; et al. Factors affecting morbidity in solid organ injuries. Dis. Markers 2016, 2016, 6954758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.; Kshirsagar, S.; Naik, S.; Pande, A. Comparative evaluation of mortality predictors in trauma patients: A prospective single-center observational study assessing Injury Severity Score, Revised Trauma Score, Trauma and Injury Severity Score, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 28, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Javali, R.H.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Patil, A.; Srinivasarangan, M.; Suraj, S.; Sriharsha, S. Comparison of Injury Severity Score, New Injury Severity Score, Revised Trauma Score and Trauma and Injury Severity Score for mortality prediction in elderly trauma patients. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 23, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).