Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GP ID | Gramm positive identification card |

| GN ID | Gramm negative identification card |

| PS | Pulled samples |

| n | number |

References

- Dent D.; Binks, R. H. Insect pest management. 2020, Cabi, pp 1-11.

- Boneva-Marutsova, B. Study on the Distribution and Evaluation of the Efficiency of the Control Methods of Synanthropic Cockroach Species in Animal Farms and Food Processing Plants in Bulgaria; Ph.D. Thesis, Trakia University, Stara Zagora, Bulgaria, 2024.

- Alesho N. A. Synanthropic cockroaches of Russia. Proceedings of the International Colloquia on Social Insects. 1997, Volume 3-4., 45-50 ref. 37.

- Roth L. M.; Willis, E. R. The medical and veterinary importance of cockroaches. Smirhsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 1957, pp. 134 : 137.

- Czajka E. ; Pancer K,; Kochman , M.; Gliniewicz , Al.; Sawicka, B.; Rabczenko, D.; Stypułkowska-Misiurewicz, H. Characteristics of bacteria isolated from body surface of German cockroaches caught in hospitals. Przegl Epidemiol. 2003., 57 (4), 655-62.

- Odinets, A.A.; Seradzhi, V.E.; Degtyareva, L.A.; Odinets, O.L. The level of social organization of synanthropic cockroaches. Proceedings of the Colloquia on Social Insects, St. Petersburg. 1993, Vol. 2, pp. 221–222. Available online: http://pestkiller.ru/sochrorganizachiya.shtml (accessed on 1 August 2025) (RU).

- Donets, A.V. Problematic issues in cockroach control in medical and preventive institutions. Bulletin of Hygiene and Epidemiology. 2004, 8(1), 116–120 (RU).

- Vatev, N.T.; Kevorkyan, A.K.; Rakadzhieva, T.A.; Stoilova, Y.D. Manual for Practical Exercises in the Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases. Raikov Publishing, 2006. pp. 26–27 (BG).

- Vahabi A.; Rafinejad J.; Mohammadi, P.; Biglarian, F. Regional evaluation of bacterial contamination in hospital environment cockroaches. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2007, 4, 57–60.

- Patel A.; Jenkins M.; Rhoden K.; Barnes, A. N. A systematic review of zoonotic enteric parasites carried by flies, cockroaches, and dung beetles. Pathogens. 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Merad Y.; Belkacemi, M.; Merad, Z.; Bassaid, A.; Benmansour, Z.; Matmour D.; Belmokhtar Z. Fungal carriage of hospital trapped cockroaches: A prospective study. New Microbes New Infect. 2023, 52, 101086. [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Yu, H.; Zhao, T.; Li, C. The Medical Importance of Cockroaches as Vectors of Pathogens: Implications for Public Health. Zoonoses. 2025, 5(1), 982. [CrossRef]

- Pai H. H.; Chen W. C.; Peng C. F. Isolation of bacteria with antibiotic resistance from household cockroaches (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica). Acta Trop. 2005, 93 (3), 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Blazar J.M.; Lienau E.K.; Allard, M.W. Insects as vectors of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews. 2011, 4 (1), 5-16. [CrossRef]

- Fila M.; Woźniakowski, G. African swine fever virus – the possible role of flies and other insects in virus transmission. Journal of Veterinary Research. 2020, 64 (1-7). [CrossRef]

- Yoon H.; Hong, S.-K; Lee Il.; Lee, E.-S. Insects as potential vectors of African swine fever virus in the Republic of Korea. Authorea Preprints. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Medrano M. A literature review to gather the scientific evidence for an African Swine Fever virus (ASFV) exposure assessment of US domestic pigs raised in total confinement and/or with outdoor access to ASFV-infected feral swine. 2023, https://conservancy.umn.edu/items/4c8f4b8a-c992-4d4f-a911-53096ccabf77.

- Moges F.; Eshetie, S.; Endris M. Cockroaches as a source of high bacterial pathogens with multidrug resistant strains in Gondar Town, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2016, 2825056. [CrossRef]

- Liu J.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, L.; Lin, C.; Ye, C.; Liu J.; Liu H. Intestinal pathogens detected in cockroach species within different food-related environment in Pudong, China. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14 (1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Fang W.; Fang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Zhang X.; Peng, H.; Xiao, Y. Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial community in the gut of American cockroach (Periplaneta americana). Wei Sheng wu xue bao=Acta Microbiologica Sinica. 2013, 53 (9), 984-994.

- Fotedar R.; Shriniwas U. B.; Verma, A. Cockroaches (Blattella germanica) as carriers of microorganisms of medical importance in hospitals. Epidemiol Infect. 1991, 107 (1), 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Solomon F.; Belayneh F.; Kibru G.; Ali, S. Vector potential of Blattella germanica (L.) (Dictyoptera: Blattidae) for medically important bacteria at food handling establishments in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. BioMed Research International. 2016, (1), 3490906. [CrossRef]

- Alikhani M. Y.; Parsavash S.; Arabestani M. R.; Hosseini , S. M. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance and class 1 integrons in clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017, 4 (4): 12086. [CrossRef]

- Haile T.; Mariam, A.T.; Kiros S.; Teffera, Z. Cockroaches as carriers of human gastrointestinal parasites in Wolkite Town, southwestern Ethiopia. J Parasitol Vector Biol. 2018, 10 (2), 33‒38. [CrossRef]

- Davari B.; Hassanvand, A. E.; Salehzadeh, A.; Alikhani, M. Y.; Hosseini, S. M. Bacterial Contamination of Collected Cockroaches and Determination their Antibiotic Susceptibility in Khorramabad City, Iran. Journal of Arthropod-Borne Diseases. 2023, 17 (1), 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Alyas S. S.; Ibrahim R. K.; Kareem, A. A. Study the pathogenicity of the bacteria associated with Periplanta americana cockroach on Gelleria mollonella. L worm larva. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2021. (Vol. 1999, No. 1, p. 012032). IOP Publishing.

- Bizzini A.; Jaton, K.; Romo, D.; Bille, J.; Prod’hom G.; Greub, G. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry as an alternative to 16S rRNA gene sequencing for identification of difficult-to-identify bacterial strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 693–696. [CrossRef]

- Rettinger A.; Krupka, I.; Grunwald, K.; Dyachenko, V.; Fingerle, V.; Konrad, R.; Heribert, R.; Busch U. et al. Leptospira spp. strain identification by MALDI TOF MS is an equivalent tool to 16S rRNA gene sequencing and multi locus sequence typing (MLST). BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 185. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Sancho M.; Vela, A.I.; Garcıa-Seco, T.; Gottschalk, M.; Domınguez L.; Fernandez-Garayzabal, J.F. Assessment of MALDI-TOF MS as alternative tool for Streptococcus suis identification. Front Public Health. 2015. 3, 202. [CrossRef]

- Singhal N.; Kumar M.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF MS in clinical parasitology: applications, constraints and prospects. Parasitology. 2016, 143, 1491–1500. [CrossRef]

- Manukumar H.M.; Umesha, S. MALDI-TOF-MS based identification and molecular characterization of food associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Mehainaoui A.; Menasria, T.; Benouagueni, S.; Benhadj, M.; Lalaoui R.; Gacemi-Kirane, D. Rapid screening and characterization of bacteria associated with hospital cockroaches (Blattella germanica L.) using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Journal of applied microbiology. 2021, 130 (3), 960-970. [CrossRef]

- Cloarec A., Rivault, C.; Fontaine F.; Le Guyader, A. Cockroaches as carriers of bacteria in multi-family dwellings. Epidemiology & Infection. 1992, 109 (3), 483-490. [CrossRef]

- Al-bayati N. Y.; Al-Ubaidi A. S.; Al-Ubaidi, I. K. Risks associated with cockroach Periplaneta americana as a transmitter of pathogen agents. Diyala Journal of Medicine. 2011, 1 (1), 91-97.

- Menasria T.; Moussa, F.; El-Hamza, S.; Tine, S.; Megri R.; Chenchouni H. Bacterial load of German cockroach (Blattella germanica) found in hospital environment. Pathog Glob Health. 2014a, 108 (3), 141– 147. [CrossRef]

- Menasria T.; Tine, S.; Souad, E.; Mahcene, D.; Moussa, F.; Benammar L.; Mekahlia, M. N. A survey of the possible role of German cockroaches as a source for bacterial pathogens. J Adv Sci Appl Eng. 2014b, 1 (1), 67–70.

- Molewa M. L.; Barnard T.; Naicker, N. A potential role of cockroaches in the transmission of pathogenic bacteria with antibiotic resistance: A scoping review. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2022, 16 (11), 1671-1678. [CrossRef]

- Alhajeri N.; Alharbi J. S.; El-Azazy, O. M. The Potential Role of the American Cockroach (Periplaneta americana) as a Vector of Enterobacteriaceae in Kuwait. Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences E Medical Entomology & Parasitology. 2023, 15 (1). [CrossRef]

- Mariam S. H. Isolation and Characterization of Gram-Negative Bacterial Species from Pasteurized Dairy Products: Potential Risk to Consumer Health. J Food Qual. 2021, 17, 1‒10. [CrossRef]

- Popova T.; Trencheva K.; Tomov, R. Investigation on the microflora of the Brazilian cockroach Blaberus giganteus (L.)(Blattodea: Blaberidae) with a view to assess its epizootiological significance. Ecology and Future-Journal of Agricultural Science and Forest Science. 2010, 9 (3), 30-33.

- Zarchi A. A. K.; Vatani H. A survey on species and prevalence rate of bacterial agents isolated from cockroaches in three hospitals. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2009, 9 (2), 197-200. [CrossRef]

- Holakuie Naieni, K.; Ladonni, H.; Asle Soleimani, H.; Afhami, Sh.; Shayeghi, M. The role of German cockroach in hospital infection. J Sch Public Health. 2004, 2, 43–54.

- Rivault C.; Cloarec A.; Le Guyader A. Bacterial load of cockroaches in relation to urban environment. Epidemiology & Infection. 1993, 110 (2), 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Vythilingam I.; Jeffery, J.; Oothuman, P.; AR A. R.; Sulaiman, A. Cockroaches from urban human dwellings: isolation of bacterial pathogens and control. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 1997, 28 (1), 218-222.

- Schapheer, C.; González, L. M.; Villagra, C. Microorganism Diversity Found in Blatta orientalis L.(Blattodea: Blattidae) Cuticle and Gut Collected in Urban Environments. Insects. 2024, 15 (11), 903. [CrossRef]

- Fotedar R.; Banerjee, U.; Samantray, J. C. Vector potential of hospital houseflies with special reference to Klebsiella species. Epidemiology and infection. 1992a, 109 (1), 143.

- Grübel P.; Hoffman, J. S.; Chong, F. K.; Burstein, N. A.; MePani C.; Cave, D. R. Vector potential of houseflies (Musca domestica) for Helicobacter pylori. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997, 35 (6), 1300-1303. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi M.; Sasaki, T.; Saito, N.; Tamura, K.; Suzuki, K.; Watanabe H.; Agui, N. Houseflies: not simple mechanical vectors of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1999, 61 (4), 625-629. [CrossRef]

- Pai H.H.; Chen W. C.; Peng, C. F. Isolation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria from hospital cockroaches (Periplaneta americana). J Hosp Infect. 2003, 53 (3), 224–228. [CrossRef]

- Zurek L.; Schal, C. Evaluation of the German cockroach (Blattella germanica) as a vector for verotoxigenic Escherichia coli F18 in confined swine production. Veterinary Microbiology. 2004, 101 (4), 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother J. M. Neonatal Escherichia coli diarrhea. Diseases of swine. 1999, 8, 433-441.

- Bosworth B.T.; Casey, T. Procedure for multiplex PCR for porcine E. coli. In: Proceedings of the 97th ASM General Meeting, Miami Beach, FL. 1997, May 4–8.

- Bertschinger H.U. Postweaning Escherichia coli diarrhea and edema disease. In: Straw, B.E., D’Allaire, S., Mengeling, W.L., Taylor, D.J. (Eds.), Disease of Swine. Iowa University Press, Ames, IA. 1999, pp. 441–454.

- Moon H.W.; Hoffman, L.J.; Cornick, N.A.; Booher S.L.; Bosworth, B.T. Prevalence of some virulence genes among Escherichia coli isolates from swine presented to a diagnostic laboratory in Iowa. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1999, 11, 557-560. [CrossRef]

- Waldvogel M. G.; Moore, C. B.; Nalyanya, G. W.; Stringham, S. M., Watson, D. W.; Schal, C. O. B. Y. Integrated cockroach (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae) management in confined swine production. In Proceedings of the 3rd international conference of urban pests. Prague (Czech Republic): Graficke Zavody Hronov, 1999, July, pp. 183-188.

- Zurek L.; Gore, J.C.; Stringham, S.M.; Watson, D.W.; Waldvogel M.G.; Schal, C. Boric acid dust as a component of an integrated cockroach management program in confined swine production. J. Econ. Entomol. 2003, 96, 1362–1366. [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh A.; Tavacol, P.; Mahjub, H. Bacterial, fungal and parasitic contamination of cockroaches in public hospitals of Hamadan, Iran. J Vector Borne Dis 2007, 44, 105-110.

- Vazirianzadeh B.; Mehdinejad, M.; Dehghani, R. Identification of bacteria which possible transmitted by Polyphaga aegyptica (Blattodea: Blattidae) in the region of Ahvaz, SW Iran. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology. 2009, 2 (1).

- Schauer C.; Thompson C. L.; Brune, A. The bacterial community in the gut of the cockroach Shelfordella lateralis reflects the close evolutionary relatedness of cockroaches and termites. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2012, 78 (8), 2758-2767. [CrossRef]

- Schauer C.; Thompson C.; Brune, A. Pyrotag sequencing of the gut microbiota of the cockroach Shelfordella lateralis reveals a highly dynamic core but only limited effects of diet on community structure. PLoS One. 2014, 9 (1), e85861. [CrossRef]

- Lampert N.; Mikaelyan A.; Brune, A. Diet is not the primary driver of bacterial community structure in the gut of litter-feeding cockroaches. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19 (1), 238. [CrossRef]

- Gorwitz R.J.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; McAllister, S.K.; McQuillan, G.; McDougal, L.K.; Fosheim, G.E.; Jensen, B.J.; Killgore, G.; Tenover F. C.; Kuehnert, M. J. Changes in the prevalence of nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2001–2004. J Infect Dis. 2008, 197 (9):1226–1234. [CrossRef]

- Islam A.; Nath, A. D.; Islam, K.; Islam, S.; Chakma, S.; Hossain, M. B.; Al-Faruq A.; Hassan, M. M. Isolation, identification and antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus in cockroaches (Periplaneta americana). J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2016, 3 (3), 221–228. [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki Z.; Mashak, Z.; Safarpoor Dehkordi, F. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance in the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from hospital cockroaches. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control. 2019, 8 (1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Cotton M. F.; Wasserman, E.; Pieper, C. H.; Theron, D. C.; Van Tubbergh, D.; Campbell G.; Barnes, J. Invasive disease due to extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal unit: the possible role of cockroaches. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000, 44 (1), 13-17. [CrossRef]

- Robertson A. R. The Isolation and Characterization of the Microbial Flora in the Alimentary Canal of Gromphadorhina portentosa Based on rDNA Sequences. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2007, Paper 2069. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2069.

- Haghi F. M.; Nikookar, H.; Hajati, H.; Harati, M. R.; Shafaroudi, M. M.; Yazdani-Charati J.; Ahanjan, M. Evaluation of bacterial infection and antibiotic susceptibility of the bacteria isolated from cockroaches in educational hospitals of Mazandaran University of medical sciences. Bull Env Pharmacol Life Sci. 2014, 3, 25-28.

- Kundera I. N.; Sapu E. H.; Bialangi, M. Identification of Bacteria on Cockroach Feet (Periplaneta americana) in Resident Bay of Palu Permai and Sensitivity Test Against Antibiotics. Techno Jurnal Penelitian. 2020, 9 (1), 353-362. [CrossRef]

- Saitou K.; Furuhata, K. Kawakami, Y.; Fukuyama M. Biofilm formation abilities and disinfectant-resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cockroaches captured in hospitals. Biocontrol science. 2009, 14 (2), 65-68. [CrossRef]

| Pathogen | Criteria | Farm 1 (n of PS = 10) |

Farm 2 (n of PS = 8) |

Farm 3 (n of PS = 10) |

Farm 4 (n of PS = 7) |

Total (n of PS = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

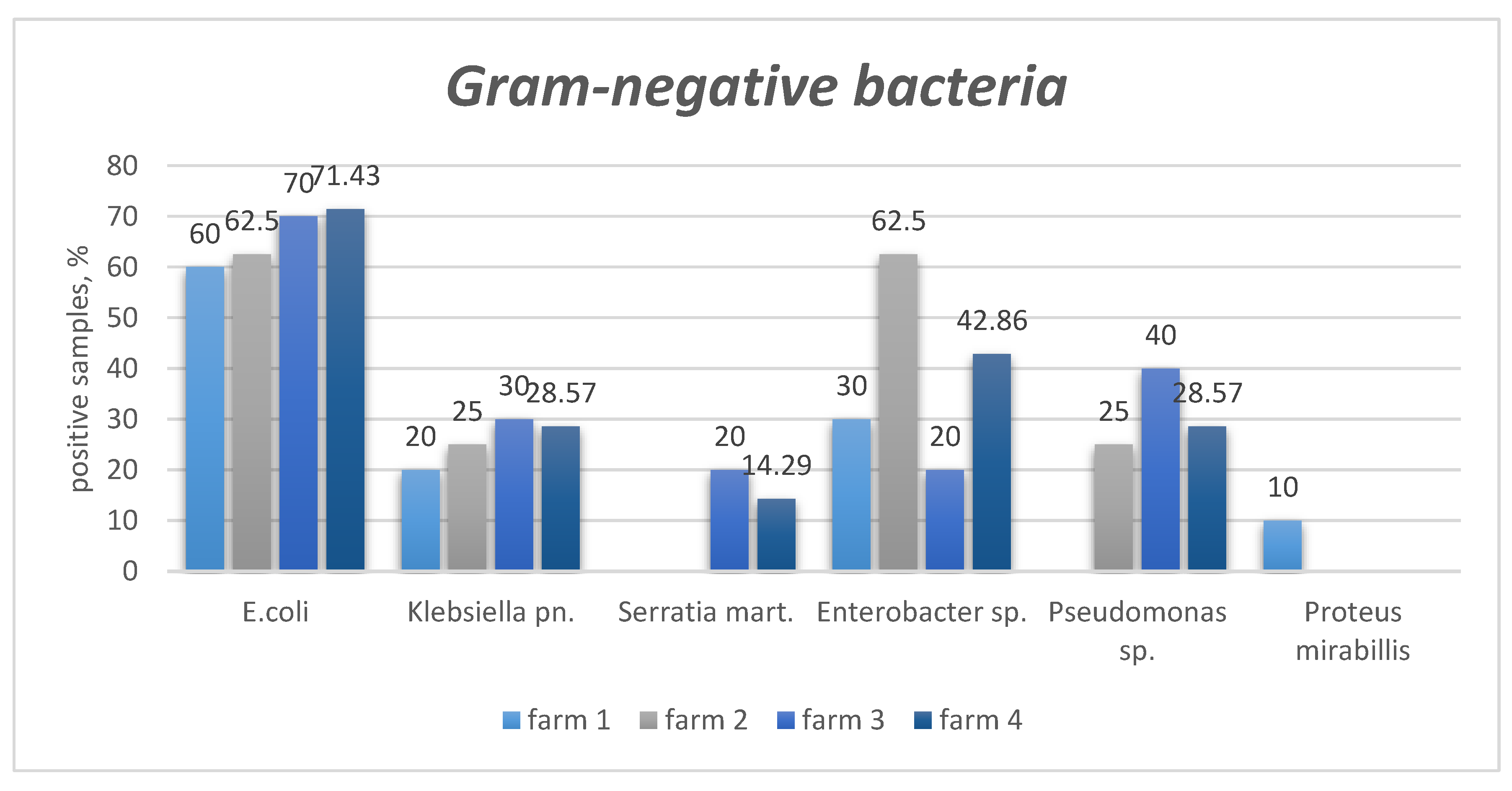

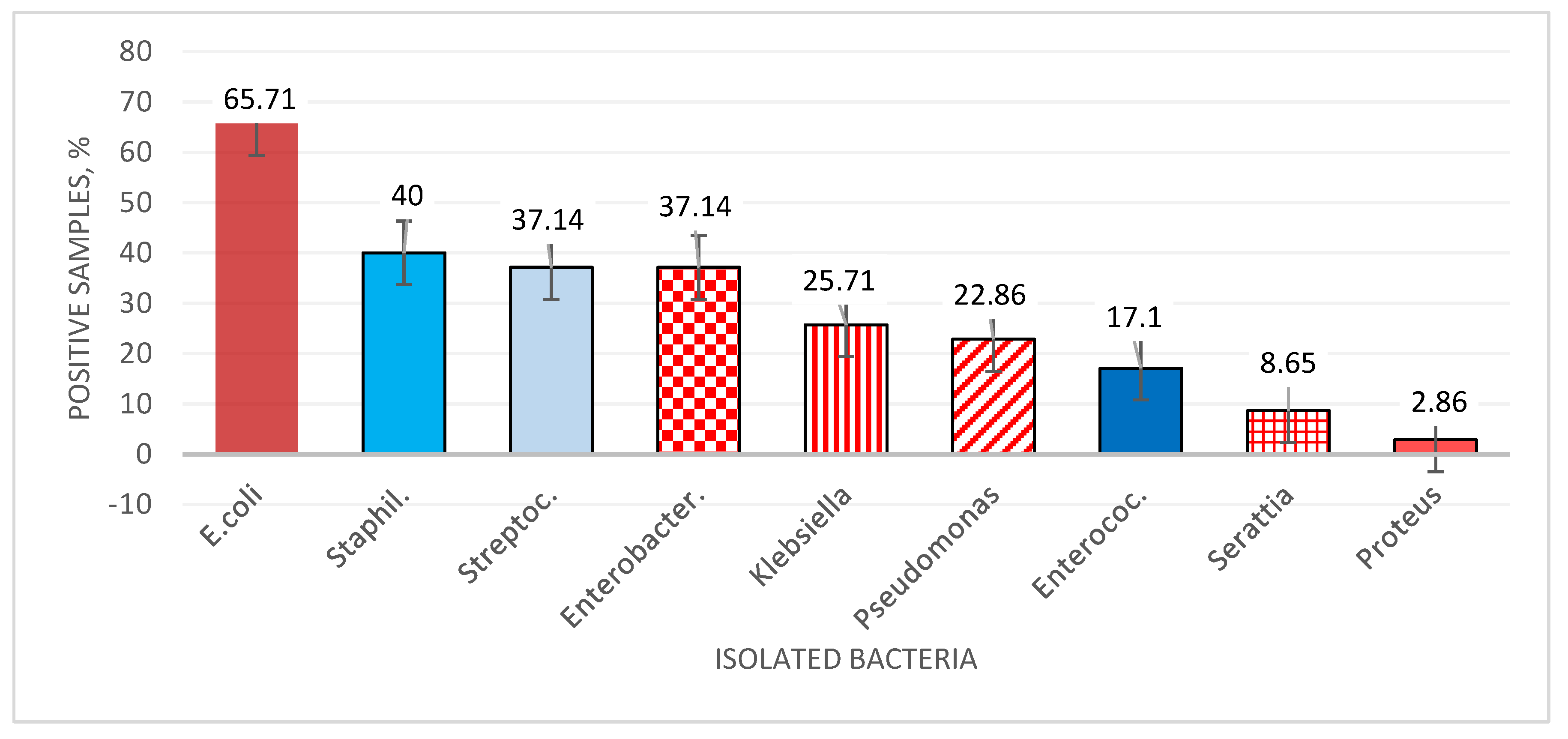

| Gram-negative bacteria | ||||||

|

E. coli |

presens | (6) 60% | (5) 62.5% | (7) 70% | (5) 71.4% | (23) 65.7% |

| absence | (4) 40% | (3) 37.5% | (3) 30% | (2) 28.6% | (12) 34.3% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.102; Sig. (p) = 0.047 | ||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | presens | (2) 20% | (2) 25% | (3) 30% | (2) 28.6% | (9) 25.7% |

| absence | (8) 80% | (6) 75% | (7) 70% | (5) 71.4% | (26) 74.3% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.092; Sig. (p) = 0.046 | ||||||

| Serattia marcescens | presens | (0) 0% | (0) 0% | (2) 20% | (1) 14.3% | (3) 8.6% |

| absence | (10) 100% | (8) 100% | (8) 80% | (6) 85.7% | (32) 91.4% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.323; Sig. (p) = 0.030 | ||||||

| Enterobacter spp. | presens | (3) 30% | (5) 62.5% | (2) 20% | (3) 42.9% | (13) 37.1% |

| absence | (7) 70% | (3) 37.5% | (8) 80% | (4) 57.1% | (22) 62.9% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.329; Sig. (p) = 0.028 | ||||||

| Pseudomonas spp. | presens | (0) 0% | (2) 25% | (4) 40% | (2) 28.6% | (8) 22.9% |

| absence | (10) 100% | (6) 75% | (6) 60% | (5) 71.4% | (27) 77.1% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.370; Sig. (p) = 0.018 | ||||||

| Proteus mirabillis | presens | (1) 10% | (0) 0% | (0) 0% | (0) 0% | (1) 2.9% |

| absence | (9) 90% | (8) 100% | (10) 100% | (7) 100% | (34) 97.1% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.271; Sig. (p) = 0.046 | ||||||

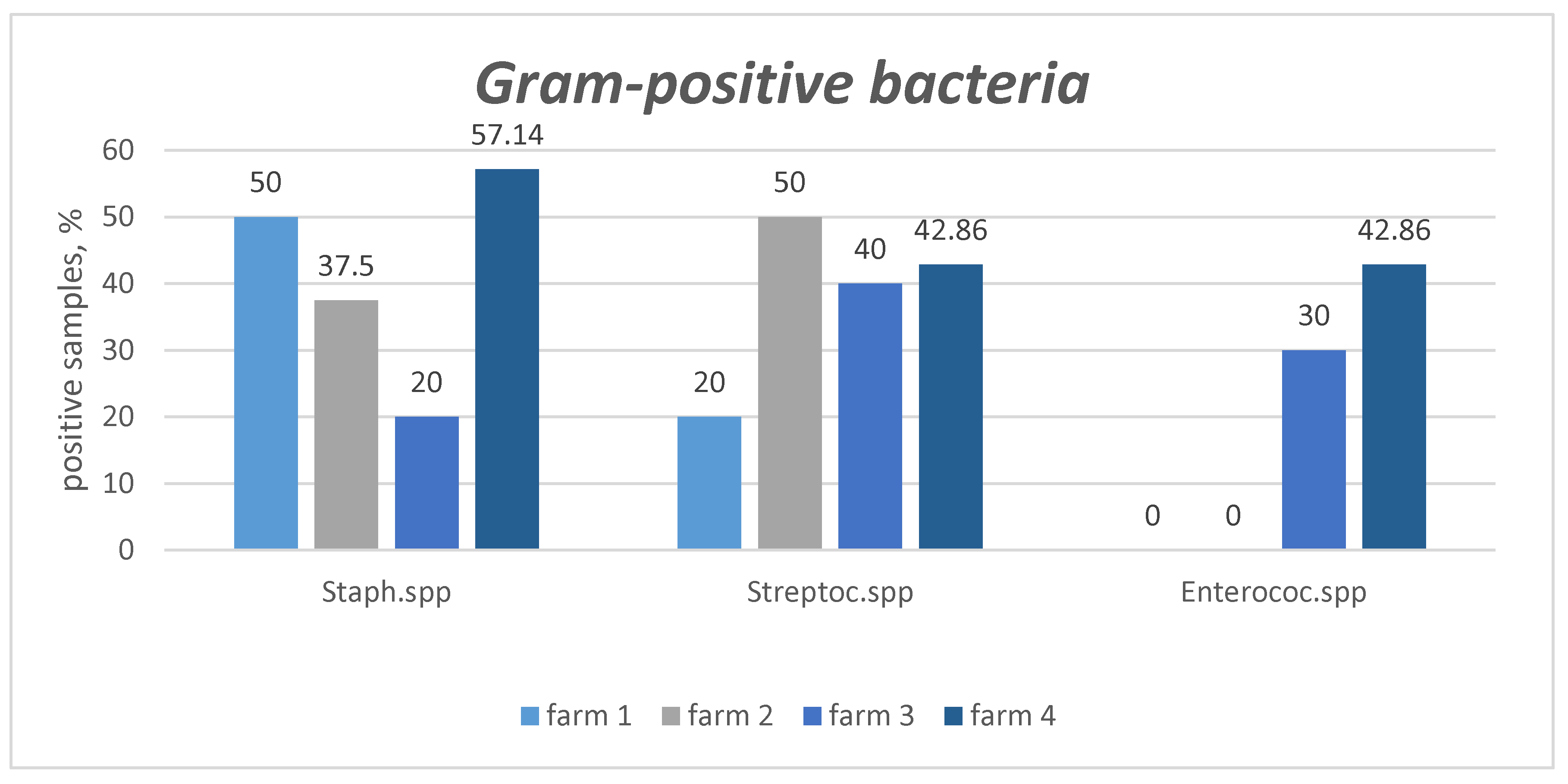

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||||

| Staphylococcus spp. | presens | (5) 50% | (3) 37.5% | (2) 20% | (4) 57.1% | (14) 40% |

| absence | (5) 50% | (5) 62.5% | (8) 80% | (3) 42.9% | (21) 60% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.291; Sig. (p) = 0.039 | ||||||

| Streptococcus spp. | presens | (2) 20% | (4) 50% | (4) 40% | (3) 42.9% | (13) 37.1% |

| absence | (8) 80% | (4) 50% | (6) 60% | (4) 57.1% | (22) 62.9% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.237; Sig. (p) = 0.051 | ||||||

|

Enterococcus spp. |

presens | (0) 0% | (0) 0% | (3) 30% | (3) 42.9% | (6) 17.1% |

| absence | (10) 100% | (8) 100% | (7) 70% | (4) 57.1% | (29) 82.9% | |

| Cramer’s V = 0.482; Sig. (p) = 0.043 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).