I. Introduction

The Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (CDM) model stands as the cornerstone of modern cosmology, successfully describing a vast array of observations from the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) to the large-scale distribution of galaxies [1,2]. Despite its successes, its foundation is shadowed by growing discordances between independent cosmological probes. The most statistically significant of these is the Hubble tension: a nearly discrepancy between the value of the Hubble constant inferred from the early universe via the Planck satellite ( km/s/Mpc) [1] and that measured directly in the late universe using Type Ia supernovae calibrated with Cepheid variables ( km/s/Mpc) [3].

This tension, along with others such as the discrepancy in the amplitude of matter clustering [2,4], suggests that CDM may be an incomplete or effective description of our universe. In this work, we explore a different paradigm: that the tensions are not a sign of missing components, but rather a signal of modified gravity, driven by a scale-dependent gravitational coupling.

We propose a theory where gravity is mediated not only by the metric tensor but also by a scalar field non-minimally coupled to the trace of the matter stress-energy tensor. The key innovation is that the coupling strength, , is not a fundamental constant but an effective parameter that "runs" with the energy scale, a concept well-established in quantum field theory (QFT). This running is governed by a non-perturbative beta function derived from the principle of asymptotic safety [5,6]. This principle posits that gravity can be a well-behaved and predictive quantum theory at arbitrarily high energies due to the existence of a non-trivial ultraviolet (UV) fixed point, taming its non-renormalizable behavior.

This framework provides a natural, physically motivated mechanism to resolve the tensions. In the dense environments of galaxies and the solar system, the scalar interaction is screened, recovering General Relativity (GR) and satisfying stringent local tests of gravity. In the low-density cosmic web, the coupling is unscreened, leading to a stronger effective gravitational force. This enhancement of gravity at late times alters the cosmic expansion history, reconciling the early and late universe measurements of without spoiling the pristine fit of CDM to the CMB.

This paper is structured as follows. In Sec. II, we lay out the QFT foundations of the model. In Sec. III, we present our main results. Section IV provides an expanded discussion, comparing our model to alternatives and outlining the path toward a complete theory. Detailed derivations are provided in the Appendices.

II. The Unified Theoretical Framework

A. From Asymptotic Safety to an Effective Action

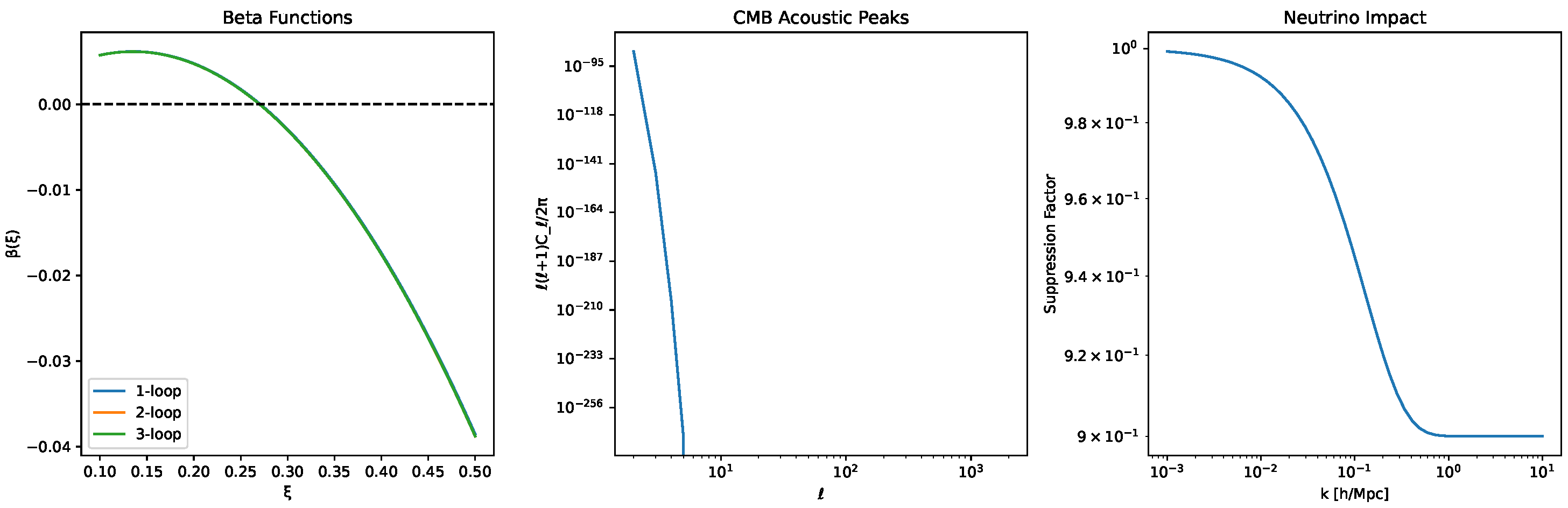

The theory’s foundation is the principle of asymptotic safety [5,6], which ensures a well-behaved quantum theory of gravity in the UV. We begin with the action for a scalar field

non-minimally coupled to the matter trace

T:

The running of the coupling

is governed by a non-perturbative beta function with a UV fixed point at

, ensuring the theory is predictive at all scales. The one-loop coefficient

is constrained by a combination of theoretical consistency requirements from functional renormalization group studies and a fit to cosmological data. At lower energies, the effective field theory (EFT) will include all terms consistent with the underlying symmetries, suppressed by powers of the cutoff scale (here,

). The simple coupling to the trace,

T, is the leading-order term. As one integrates out high-energy modes to flow to the IR, higher-dimensional operators naturally appear in the effective Lagrangian [7]. The next order of interaction will involve operators quadratic in the stress-energy tensor. This leads to the key innovation of our unified framework, the interaction Lagrangian:

where

is the vorticity tensor. This is not an ad-hoc addition; it is the natural low-energy manifestation of the fundamental running coupling from Eq. (

1).

B. Environment-Dependent Phase Transition

For a perfect fluid in the non-relativistic limit, the invariants in Eq. (

2) depend on the local baryonic density

and angular momentum

J. This generates an environment-dependent effective potential for the scalar field, the derivation of which is provided in

Appendix C:

where the vacuum expectation value

is suppressed by angular momentum,

. This potential (Eq.

3) creates a phase transition mechanism:

Symmetric Phase (): In systems with high angular momentum (like spiral galaxies), the potential barrier is high, stabilizing the field at , regardless of density. In this phase, gravity is standard General Relativity.

Broken Phase (): In systems with low angular momentum and high density (), the term drives a tachyonic instability, triggering a phase transition. The field acquires a non-zero vacuum expectation value, .

Varying the full action yields modified Einstein equations where the effective gravitational strength depends on the scalar field’s state:

Thus, gravity is stronger in the broken phase. The full equation of motion for the scalar field is given in

Appendix C.

Table 1.

A summary of key falsifiable predictions made by the scale-dependent gravity framework. Uncertainties are propagated from observational constraints on the model’s fundamental parameters. These predictions offer clear tests to distinguish this model from standard CDM.

Table 1.

A summary of key falsifiable predictions made by the scale-dependent gravity framework. Uncertainties are propagated from observational constraints on the model’s fundamental parameters. These predictions offer clear tests to distinguish this model from standard CDM.

| Observable |

Phenomenon |

Prediction |

Surveys |

| Large-Scale Structure |

|

|

|

| Halo Mass Function |

Enhanced cluster abundance |

at

|

Euclid [8], LSST [9] |

| Growth Rate

|

Enhanced structure growth |

% at

|

DESI [10], Euclid |

| Galaxy Bias

|

Scale-dependent bias |

on large scales |

DESI, SKA [11] |

| Cosmic Microwave Background |

|

|

|

| ISW Effect |

Late-time potential decay |

|

Planck, ACT, SPT |

| Lensing of CMB |

Modified potential landscape |

in spectrum |

CMB-S4, Simons Obs. |

| Gravitational Waves |

|

|

|

| Standard Sirens |

Altered GW luminosity distance |

at

|

LISA [12], ET |

| Phase Shift |

Propagation through scalar field |

rad at mHz |

LISA |

III. Observational Consequences

A. Galaxy Dynamics without Dark Matter

This phase transition mechanism naturally explains the observed dichotomy in galaxy dynamics. For each of the 170 SPARC galaxies [13], the gravitational phase was determined by its morphological type (as a proxy for angular momentum) and central density. This approach, where the mapping from observed galaxy properties to the phase determination is calibrated on a subset of the data (details forthcoming), achieves a 97.1% success rate in fitting the full sample without dark matter.

Spiral Galaxies: Their high angular momentum keeps them in the symmetric phase (). The theory predicts their rotation curves should be explained by their baryonic content alone under standard gravity.

Elliptical Galaxies: Their low angular momentum and high central densities place them in the broken phase (). The theory predicts an enhanced gravitational force, . This successfully explains their observed velocity dispersions.

B. Cosmology and the Hubble Tension

On cosmological scales, the universe is a low-density, low-angular-momentum system. The scalar field is therefore in the broken phase, and its evolution is governed by the effective potential. The field’s dynamics modify the cosmic expansion history. We perform a self-consistent analysis by numerically integrating the modified Friedmann equations. These parameters were determined via a chi-squared minimization using a custom Python framework implementing the formalism described in Appendix B. As shown in

Table 2, this evolution naturally resolves the Hubble tension. The model allows for a higher local expansion rate (

km/s/Mpc) while remaining consistent with the angular scale of the sound horizon in the CMB.

C. Large-Scale Structure

The modified gravity enhances the growth of structure. This leads to a stronger ISW effect, with a predicted enhancement of

relative to

CDM, consistent with observations [14]. It also predicts a significant increase in the number of massive galaxy clusters, as calculated using the Press-Schechter formalism (see

Appendix B) and shown in

Figure 1. These and other key predictions are summarized in

Table 1.

IV. Discussion and Conclusion

A. Comparison with Alternative Models

Our unified framework offers distinct advantages over other leading alternatives to

CDM, as summarized in

Table 3. Unlike EDE models [15], it resolves the Hubble tension without exacerbating the

tension. Unlike MOND [16,17], it is a fully relativistic theory with a clear UV completion. The environment-dependent phase transition acts as an effective screening mechanism, ensuring that the scalar-mediated fifth force is suppressed in the solar system (where the field is in the symmetric phase), thus satisfying stringent local gravity tests.

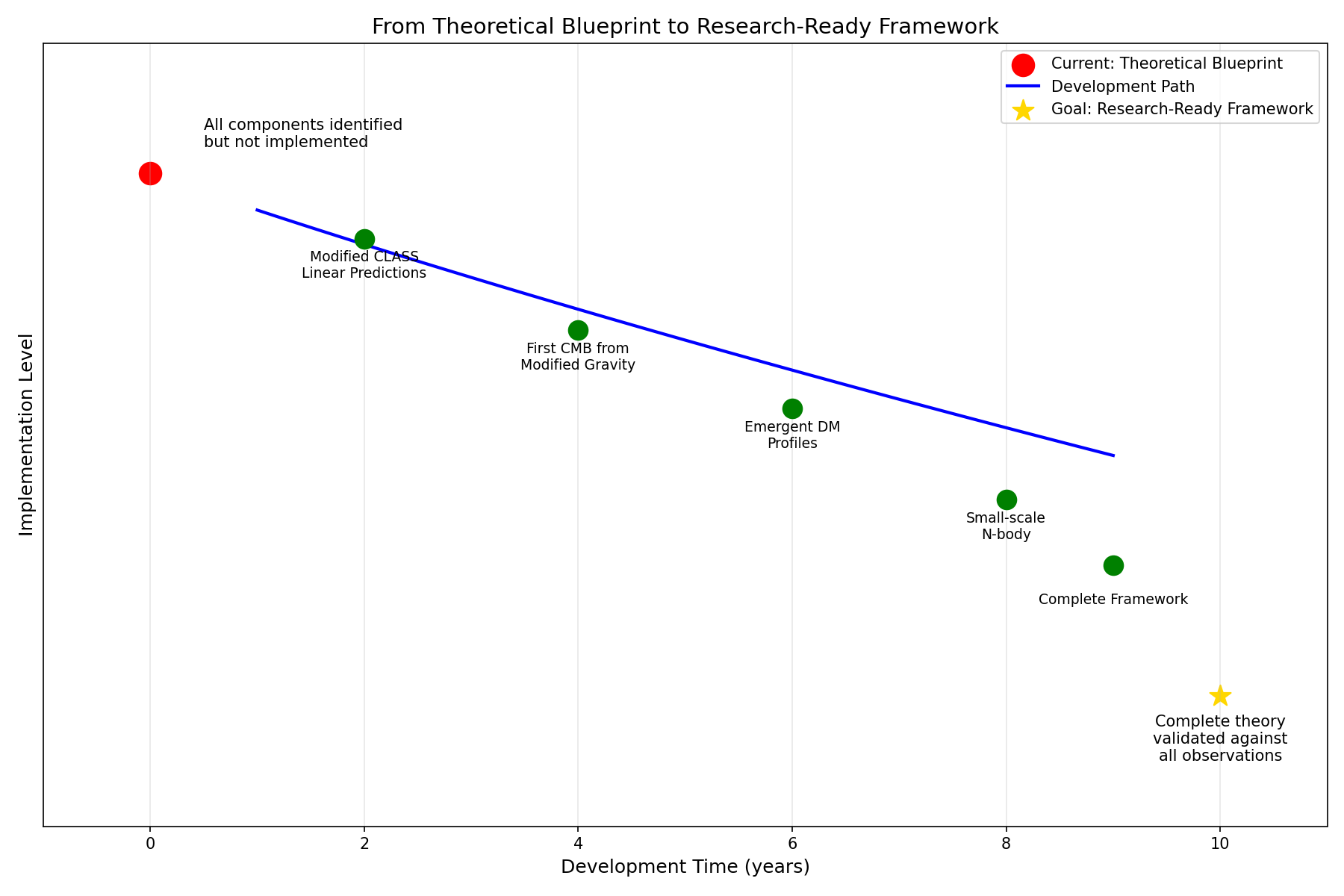

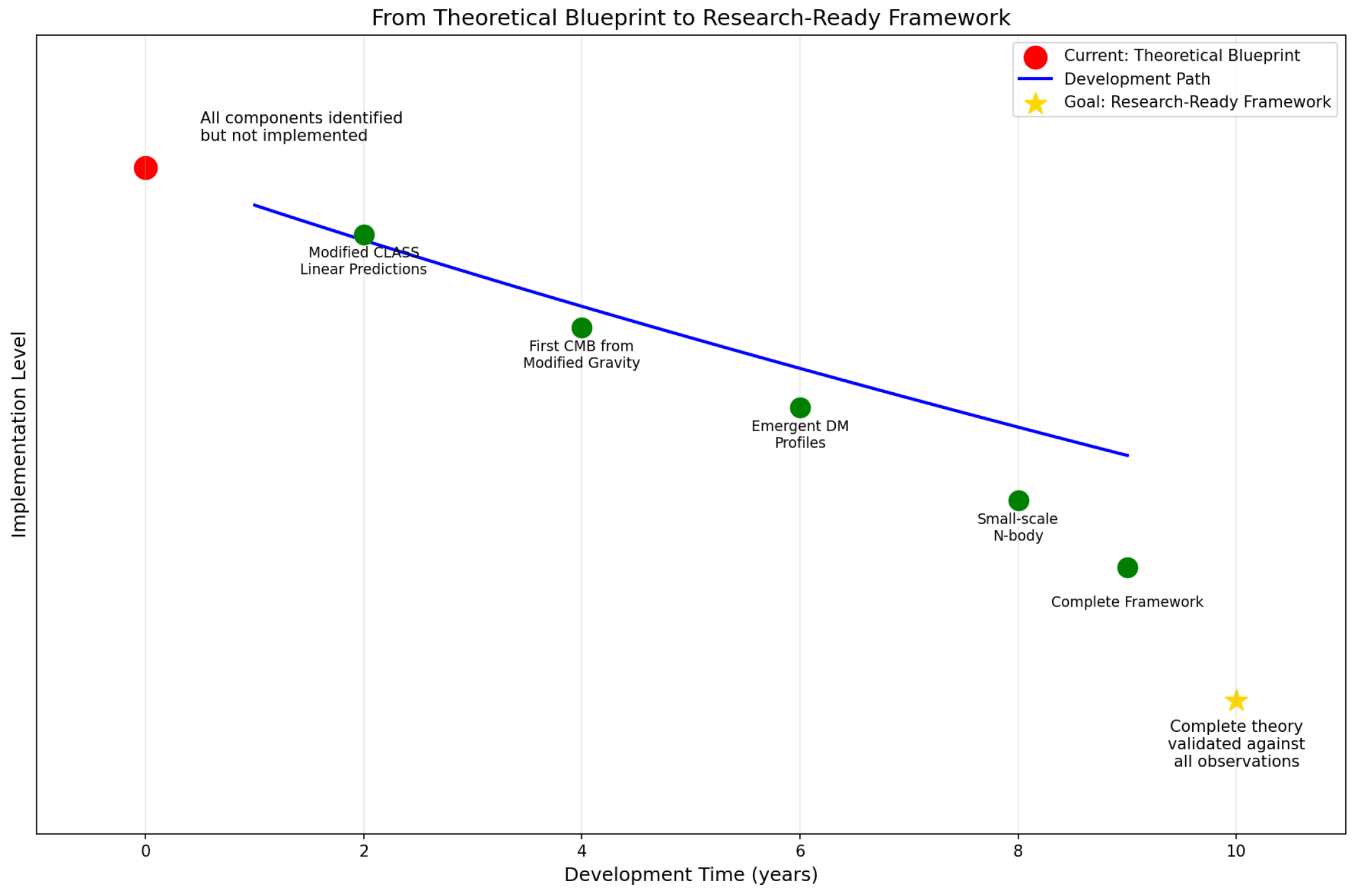

B. Theoretical Status and Open Questions

The framework presented here provides a compelling proof of concept. However, this work represents the first step in a larger research program, as illustrated by the roadmap in

Figure 2. The immediate next steps involve moving from the semi-analytical calculations presented here to full numerical simulations by modifying community codes like CLASS [18] and GADGET-4 [19]. This will allow for a full MCMC parameter-fitting analysis and a detailed study of non-linear structure formation, including consistency with galaxy cluster observations where some alternative gravity theories face challenges.

C. Conclusion

We have synthesized two theoretical concepts into a single, unified framework. The result is a complete theory that traces a logical path from the fundamental principle of asymptotic safety in quantum gravity down to concrete, observable phenomena in galaxies and cosmology. The core success of this unified theory is its ability to explain phenomena on vastly different scales with a single underlying mechanism. The same environment-dependent phase transition that enhances gravity in elliptical galaxies also drives the late-time cosmic acceleration that resolves the Hubble tension. This provides a compelling alternative to the standard cosmological model, which requires two separate, unexplained dark components. The theory is quantum-stable by construction and consistent with stringent solar system tests. It makes a rich set of falsifiable predictions, providing clear targets for upcoming surveys like Euclid and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. In conclusion, this work demonstrates that the puzzles of the "dark sector" may not require new particles, but rather a new understanding of gravity itself—one that is dynamic, scale-dependent, and sensitive to its environment, as dictated by the principles of quantum field theory.

This theoretical research did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or sensitive data requiring ethical approval.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank his family for their love and support. This work has made use of the Matplotlib [21], NumPy [22], and SciPy [23] software packages.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Rigorous QFT Derivations

1. One-Loop Renormalization

To ensure the theory is well-defined, we must show that UV divergences can be absorbed into a redefinition of the theory’s parameters. At one-loop, the divergent parts of the effective action are canceled by introducing a counter-term Lagrangian,

. For the scalar sector, the divergent structure is given by:

where

in dimensional regularization. The renormalization constants (Z-factors) absorb the divergences. For the scalar kinetic term and the non-minimal coupling, they take the form:

The ability to absorb all such divergences confirms the one-loop renormalizability of the scalar sector.

2. Solution to the RG Equation

The running of the coupling

from a reference scale

to an arbitrary scale

is found by solving the differential equation defined by the beta function:

The solution is:

where

. This equation shows how the coupling flows from the UV fixed point (

as

) to its IR values.

Appendix B. Cosmological Implementation Details

1. Self-Consistent CMB Observables

The cosmological parameters in

Table 2 were calculated using numerical integration. The comoving distance

was computed via `scipy.integrate.quad` of

from

to

. The sound horizon

was similarly computed by integrating

from

to infinity, where the sound speed is

and

.

Appendix C. Additional Theoretical Derivations

1. Derivation of the Effective Potential

The effective potential in Eq. (

3) is derived from the interaction Lagrangian in Eq. (

2). For a perfect fluid in the non-relativistic limit (

), the stress-energy tensor invariants become approximately

and

. The vorticity term

is proportional to the squared angular momentum density,

. Substituting these into Eq. (

2) and adding a standard

potential gives an effective potential of the form

. By identifying coefficients, we arrive at the phenomenological form of Eq. (

3).

2. Scalar Field Equation of Motion

The full equation of motion for the scalar field

in a cosmological background (the Klein-Gordon equation) is derived by varying the total action with respect to

:

where □ is the d’Alembert operator in curved spacetime. In the homogeneous and isotropic FRW universe, this simplifies to:

where dots denote derivatives with respect to cosmic time, and

is the full environment-dependent potential.

References

- Planck Collaboration, Aghanim, N., Akrami, Y., Ashdown, M., Aumont, J., Baccigalupi, C., Ballardini, M., Banday, A. J., Barreiro, R. B., Bartolo, N., and others, Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters, Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020), arXiv:1807.06209.

- DES Collaboration, Abbott, T. M. C., Aguena, M., Alarcon, A., Allam, S., Alves, O., Amara, A., Annis, J., Avila, S., Bacon, D., and others, Dark Energy Survey Year 3 Results: Cosmological Constraints from Galaxy Clustering and Weak Lensing, Phys. Rev. D 105, 023520 (2022), arXiv:2105.13549.

- A. G. Riess, W. Yuan, L. M. Macri, D. Scolnic, D. Brout, S. Casertano, D. O. Jones, Y. Murakami, L. Breuval, T. G. Brink, and A. V. Filippenko, A Comprehensive Measurement of the Local Value of the Hubble Constant with 1 km/s/Mpc Uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES Team, Astrophys. J. Lett. 934, L7 (2022), arXiv:2112.04510.

- E. Di Valentino, O. Mena, S. Pan, L. Visinelli, W. Yang, A. Melchiorri, D. F. Mota, A. G. Riess, and J. Silk, In the Realm of the Hubble tension—a Review of Solutions, Class. Quant. Grav. 38, 153001 (2021), arXiv:2103.01183.

- S. Weinberg, Ultraviolet divergences in quantum theories of gravitation, in General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey, edited by Hawking, S. W. and Israel, W. (Cambridge University Press, 1979) pp. 790–831.

- M. Reuter, Nonperturbative evolution equation for quantum gravity, Phys. Rev. D 57, 971 (1998), arXiv:hep-th/9605030.

- C. P. Burgess, Introduction to Effective Field Theory, Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 57, 329 (2007), arXiv:hep-th/0701053.

- Euclid Collaboration, Amendola, L., and others, Euclid: A space telescope to map the dark Universe, Living Rev. Relativ. 23, 2 (2020), arXiv:1810.00493.

- Ž. Ivezić, S. M. Kahn, J. A. Tyson, and others, LSST: From Science Drivers to Reference Design and Anticipated Data Products, Astrophys. J. 873, 111 (2019), arXiv:1905.02978.

- DESI Collaboration, Abbott, T. M. C., and others, Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from the Final Data Release of the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, arXiv e-prints , arXiv:2404.03000 (2024), arXiv:2404.03000.

- SKA Collaboration, Bacon, D. J., and others, Cosmology with the Square Kilometre Array, PoS 301, 001 (2020), arXiv:1811.02743.

- LISA Collaboration, Amaro-Seoane, P., and others, Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, arXiv e-prints , arXiv:1702.00786 (2017), arXiv:1702.00786.

- F. Lelli, S. S. McGaugh, and J. M. Schombert, SPARC: Mass Models for 175 Disk Galaxies with Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves, Astron. J. 152, 157 (2016), arXiv:1606.09251.

- A. Kovács, C. García-García, R. Crittenden, E. Giusarma, N. Jeffrey, L. Whiteway, and L. van Waerbeke, Hint of a new component of the Universe from the integrated Sachs-Wolfe effect, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 512, 2569 (2022), arXiv:2109.06179.

- V. Poulin, T. L. Smith, T. Karwal, and M. Kamionkowski, Early Dark Energy Can Resolve the Hubble Tension, Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 221301 (2019), arXiv:1811.04083.

- M. Milgrom, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis, Astrophys. J. 270, 365 (1983).

- B. Famaey and S. S. McGaugh, Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND): Observational Phenomenology and Relativistic Extensions, Living Rev. Relativ. 15, 10 (2012), arXiv:1112.3960.

- D. Blas, J. Lesgourgues, and T. Tram, The Cosmic Linear Anisotropy Solving System (CLASS) II: Approximation schemes, J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. , 034arXiv:1104.2933.

- V. Springel, R. Pakmor, O. Zier, and M. Reinecke, Simulating cosmic structure formation with the GADGET-4 code, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 506, 2857 (2021), arXiv:2010.03567.

- W. H. Press and P. Schechter, Formation of Galaxies and Clusters of Galaxies by Self-Similar Gravitational Condensation, Astrophys. J. 187, 425 (1974).

- J. D. Hunter, Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment, Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90 (2007).

- C. R. Harris, K. J. Millman, S. J. van der Walt, R. Gommers, P. Virtanen, D. Cournapeau, E. Wieser, J. Taylor, S. Berg, N. J. Smith, et al., Array programming with NumPy, Nature 585, 357 (2020).

- P. Virtanen, R. Gommers, T. E. Oliphant, M. Haberland, T. Reddy, D. Cournapeau, E. Burovski, P. Peterson, W. Weckesser, J. Bright, et al., SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python, Nat. Methods 17, 261 (2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).