Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background & Significance

1.2. Objective of the Study

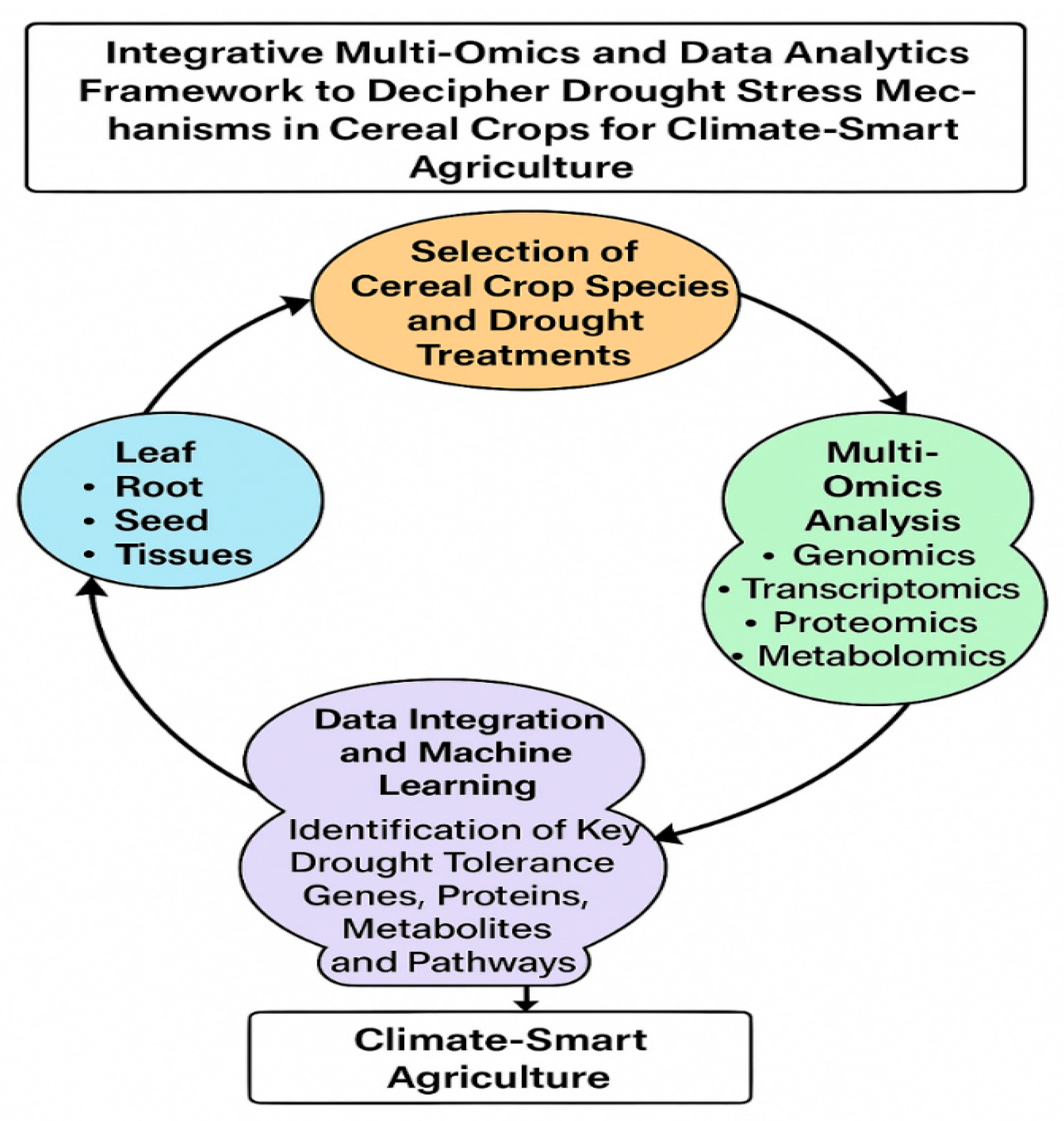

- To utilize an integrative multi-omics and data analytics framework to understand drought stress responses in cereal crops

- To identify key genes, proteins, metabolites, and pathways involved in drought tolerance

- Utilize an integrative multi-omics approach to analyze the complex interactions between genes, proteins, and metabolites in drought-stressed cereal crops.

- Identify key genes, proteins, and metabolic pathways that contribute to drought resistance, facilitating the development of climate-resilient crop varieties.

- Apply advanced data analytics and computational tools to uncover hidden patterns in large-scale omics datasets, enabling precise predictions of drought-responsive traits.

- Bridge the gap between fundamental research and practical crop improvement by translating multi-omics insights into actionable breeding and biotechnological strategies for sustainable agriculture.

1.3. Research Questions

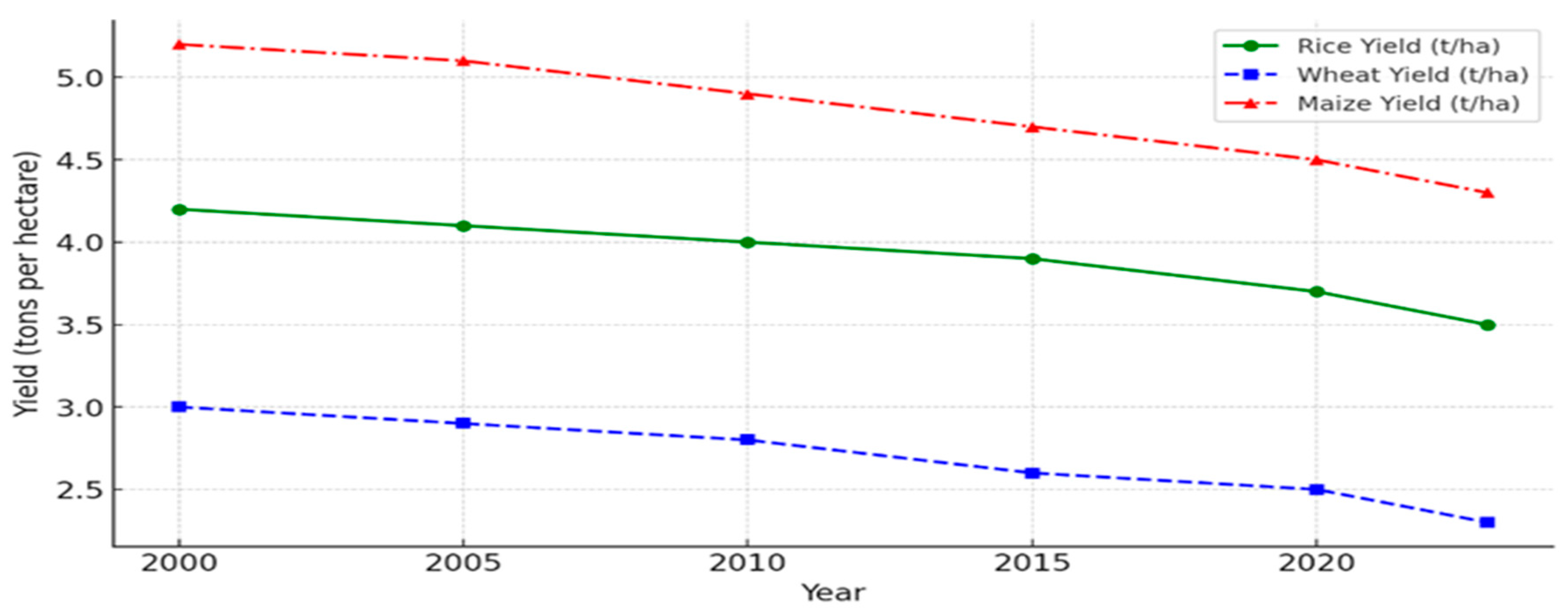

2.1. Drought Stress in Cereal Crops

2.2. Multi-Omics Approaches in Plant Science

2.3. Advances in Data Analytics for Crop Improvement

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Multi-Omics Data Collection

- Genomics & Transcriptomics

- Proteomics & Metabolomics

- Phenomics

3.3. Data Integration and Analysis

4. Results & Discussion

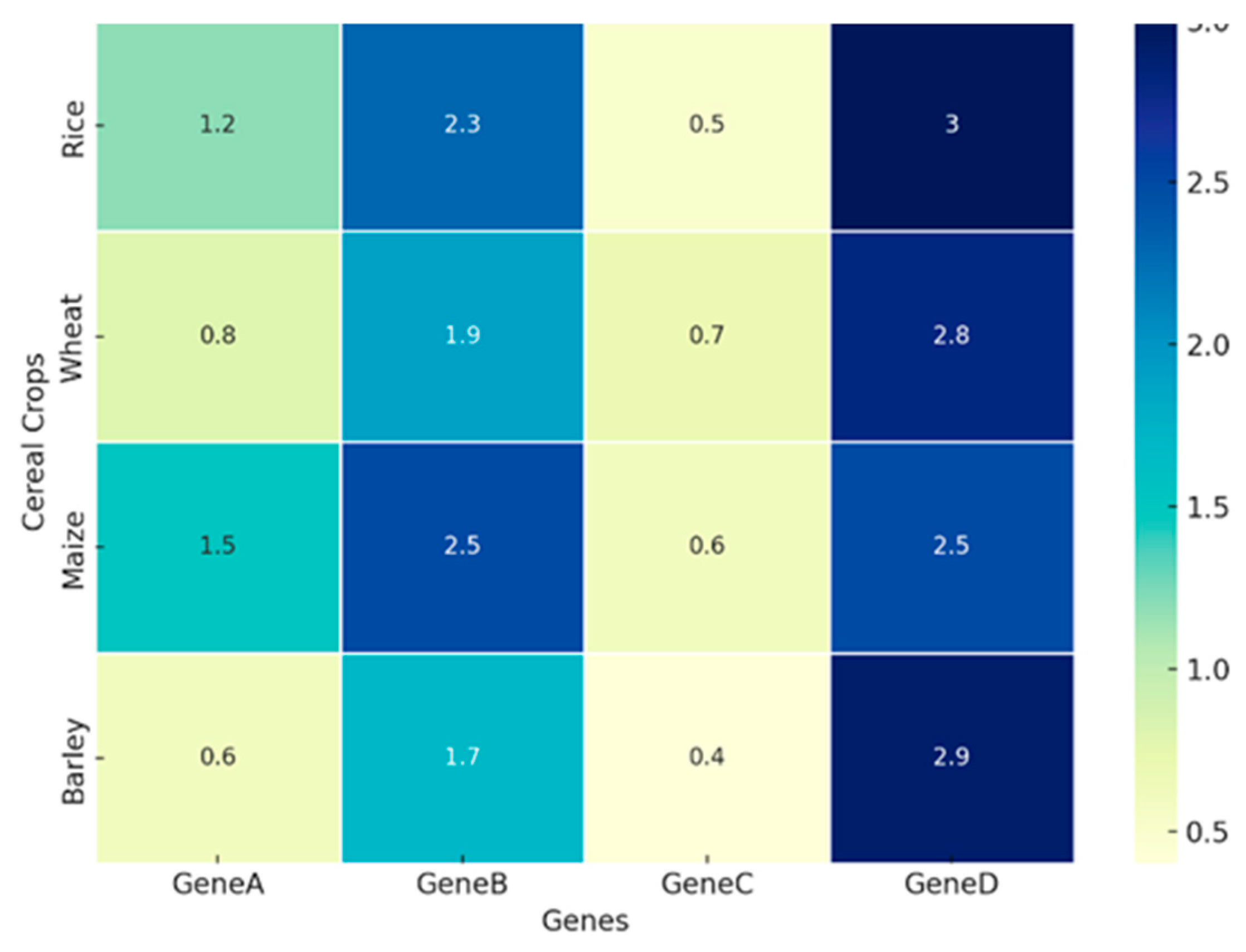

4.1. Key Findings from Multi-Omics Analysis

| Omics Layer | Key Components Identified | Function/Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | SNPs linked to DREB, NAC, MYB genes via GWAS | Associated with drought stress signaling and regulation | Xu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021 |

| Transcriptomics | Upregulation of genes like RD29A, LEA, NCED, P5CS | Involved in ABA biosynthesis, Osmo protection, and stress adaptation | Rame Gowda et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018 |

| Proteomics | Increased abundance of dehydrins, heat shock proteins, and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT) | Protection against protein damage and oxidative stress | Taji et al., 2004; Sunkar et al., 2012 |

| Metabolomics | Accumulation of proline, trehalose, raffinose, and abscisic acid (ABA) | Maintain osmotic balance and regulate stress response | Yoshiba et al., 2004; Figueroa et al., 2016 |

| Phenomics | Enhanced root length, stomatal regulation, canopy temperature, and chlorophyll fluorescence | Indicators of improved drought avoidance and photosynthetic efficiency | Finkelstein, 2013; Schmitz et al., 2019 |

| Integrated Insights | Cross-layer correlation of transcriptomic and phenomic traits | Helps in identifying biomarkers and breeding targets for drought resilience | Finkelstein et al., 2002; Simmonds et al., 2020 |

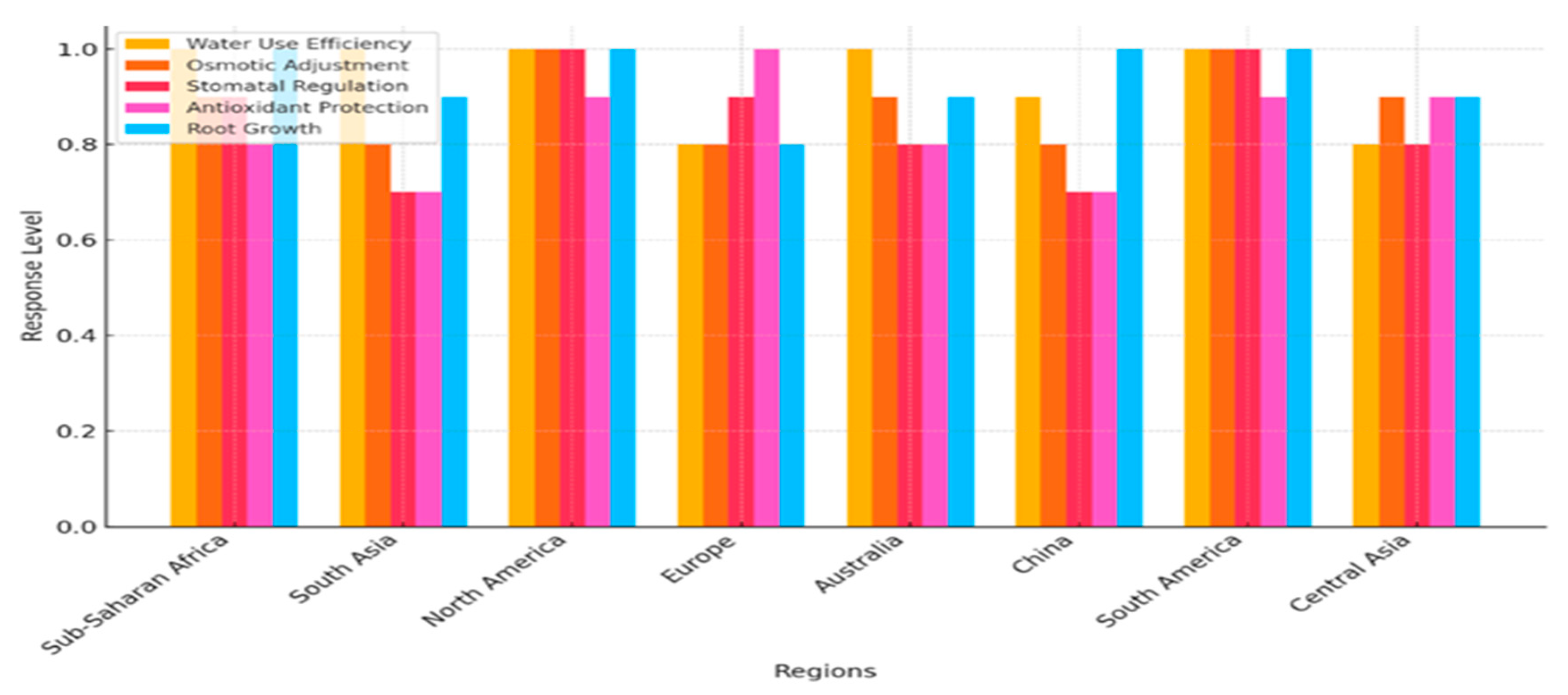

4.2. Comparative Analysis Across Cereal Crops

| Region/Country | Cereal Crop | Key Drought Response Mechanisms | Species-Specific Adaptations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) | Efficient water uses via C4 photosynthesis, osmotic adjustment with proline accumulation | High drought tolerance due to deep root system and efficient stomatal regulation | Finkelstein, 2013; Schmitz et al., 2019 |

| South Asia | Rice (Oryza sativa) | Upregulation of ABA biosynthesis genes like NCED, osmotic regulation with proline and glycine betaine | Submergence tolerance via SUB1A gene, enhanced water-use efficiency in drought-prone areas | Xu et al., 2020; Rame Gowda et al., 2014 |

| North America | Maize (Zea mays) | Deep root growth, ABA signaling for stomatal closure, upregulation of stress-responsive genes (RD29A, LEA) | Extensive root system for water uptake, NCED gene upregulation for drought tolerance | Zhang et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2018 |

| Europe (Mediterranean) | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Stomatal closure to reduce transpiration, synthesis of heat shock proteins (HSPs), antioxidant enzyme activity | DREB2A and MYB genes for drought resistance, osmotic adjustment through proline | Finkelstein, 2013; Sunkar et al., 2012 |

| Australia | Barley (Hordeum vulgare) | Osmotic regulation through compatible solutes, protection from oxidative stress via antioxidant enzymes | High photosynthetic efficiency and water-use efficiency under drought conditions | Taji et al., 2004; Schmitz et al., 2019 |

| China | Rice (Oryza sativa) | Enhanced root development, accumulation of ABA, osmotic stress regulation with trehalose | Improved drought resistance in upland rice varieties, better root growth for water acquisition | Yoshiba et al., 2004; Figueroa et al., 2016 |

| South America (Brazil) | Maize (Zea mays) | Enhanced antioxidant activity, root expansion for water uptake, ABA and proline accumulation | Drought adaptation via root and shoot architecture modifications | Zhang et al., 2021; Simmonds et al., 2020 |

| Central Asia | Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Dehydration avoidance mechanisms, stomatal regulation, gene expression in response to drought stress | Drought-responsive genes (DREB, MYB), efficient water use under arid conditions | Rame Gowda et al., 2014; Finkelstein, 2013 |

4.3. Implications for Climate-Smart Agriculture

| Target for Genetic Improvement | Potential Impact (%) | Precision Breeding/Biotechnological Role |

|---|---|---|

| Drought Tolerance | 25% | Enhance genetic selection for water-efficient crops |

| Heat Resistance | 20% | Use gene editing and genomics for heat-resistant traits |

| Pest and Disease Resistance | 15% | Develop pest-resistant varieties through genetic modification and CRISPR |

| Nutrient Efficiency | 10% | Select for crops that utilize nutrients efficiently, reducing fertilizer dependency |

| Flood Tolerance | 10% | Use precision breeding to develop flood-tolerant crops |

| Carbon Sequestration | 10% | Genetic modification to enhance carbon absorption in soil |

| Soil Health and Microbial Interventions | 10% | Use biotechnology to promote soil health and nutrient cycling |

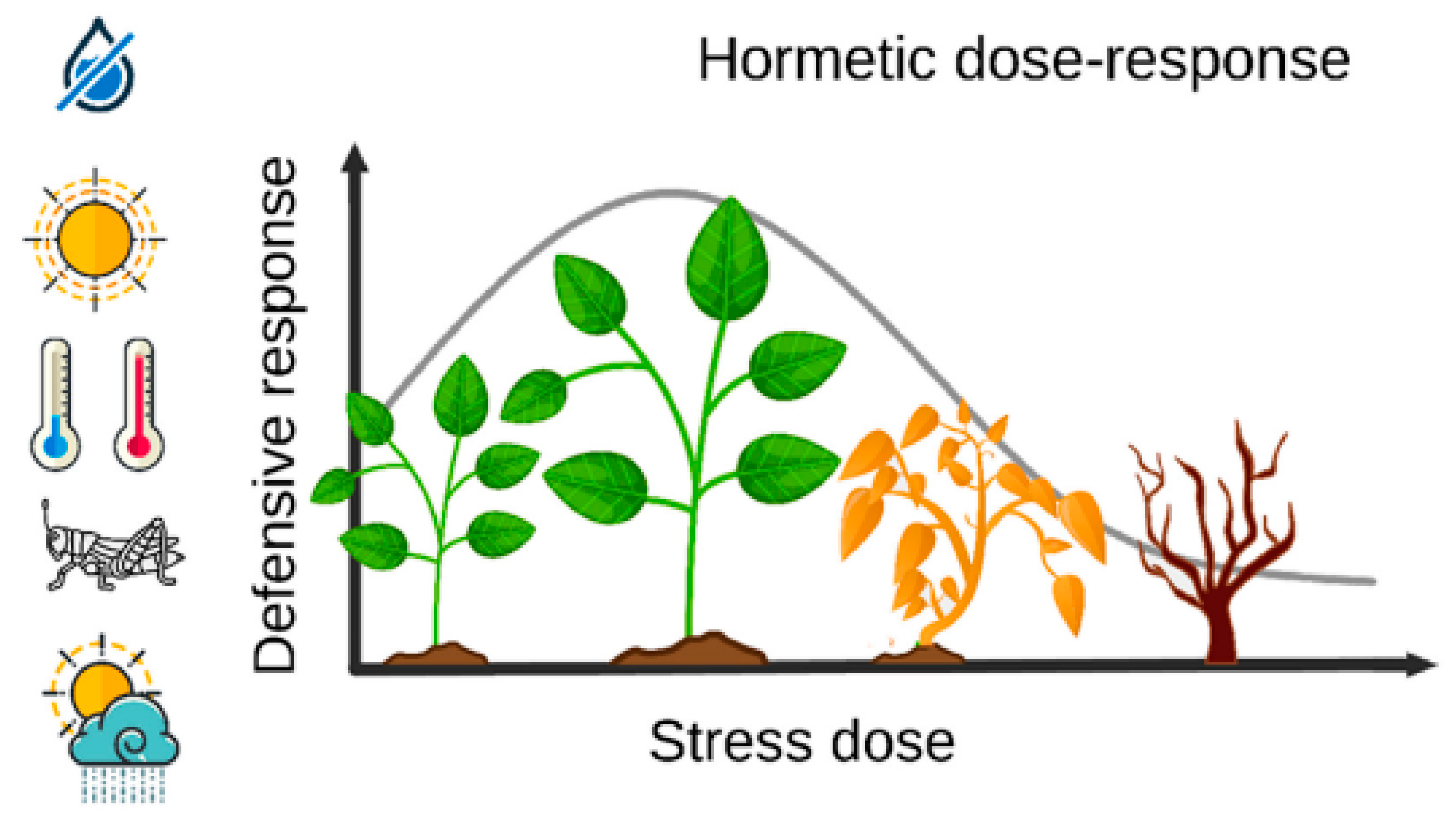

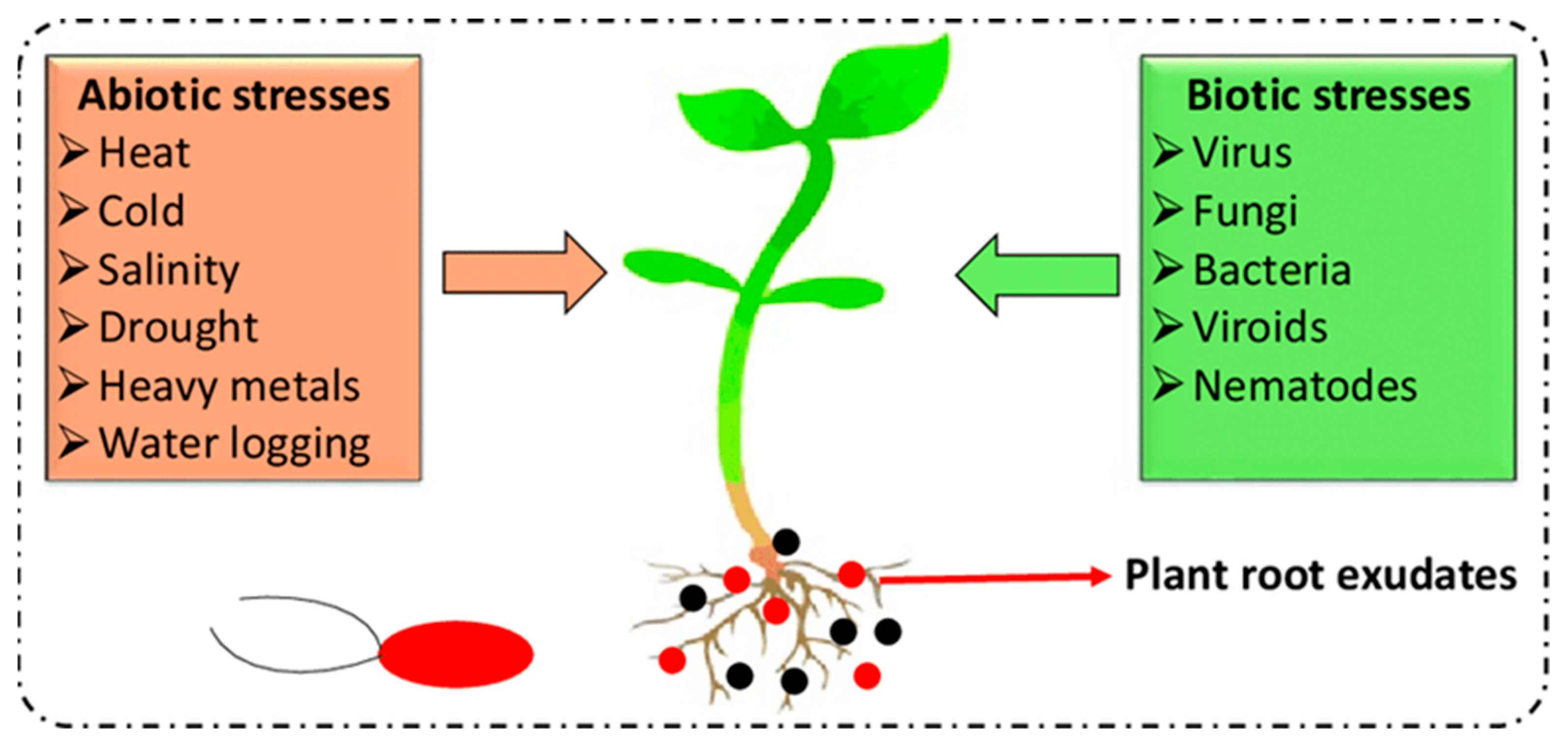

4.4. How Do Plants React to Environmental Stress Factors?

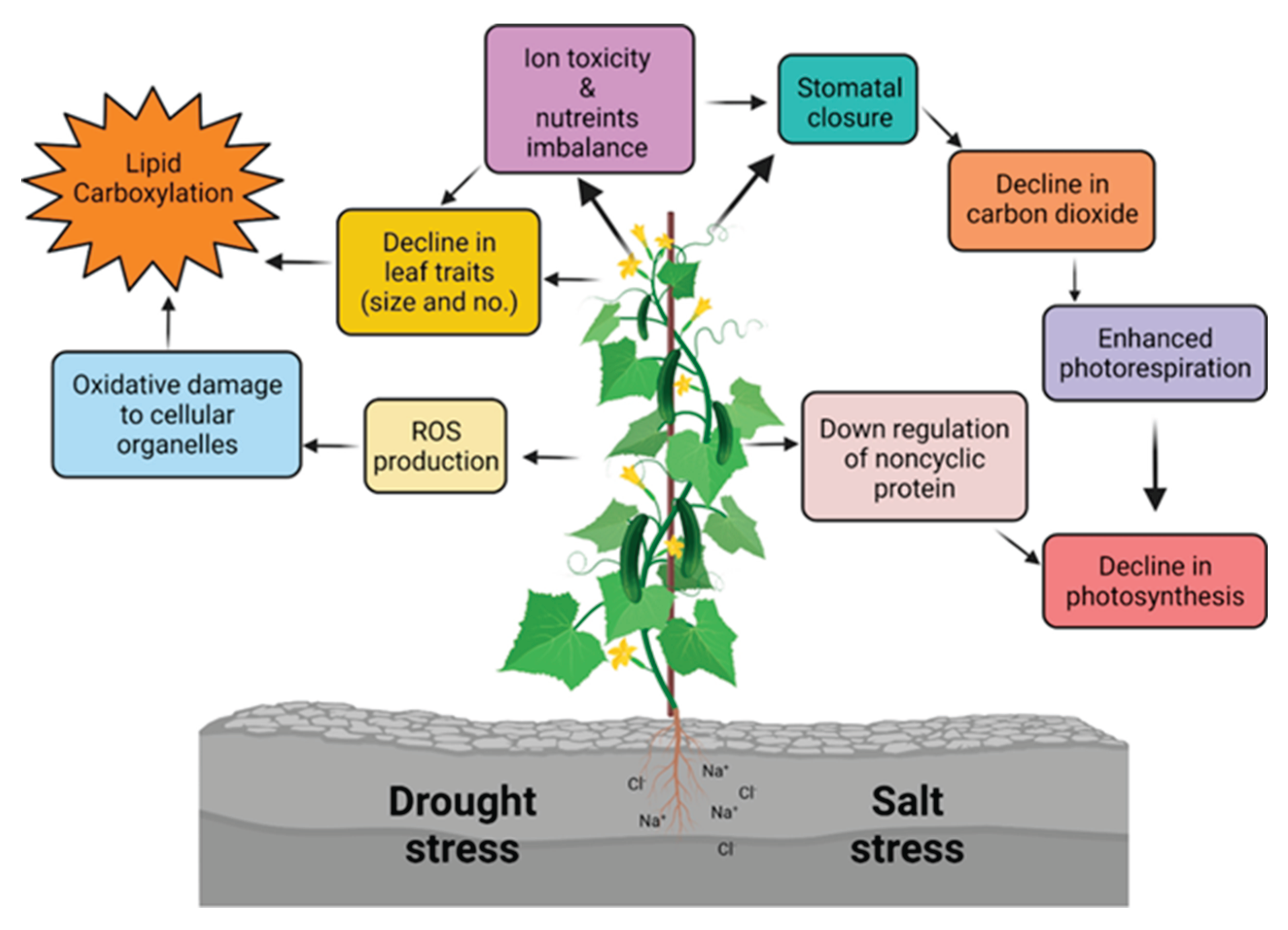

4.5. General Effects of Drought, Heat, and Salt Stress on Plant Growth and Development

5. Conclusions & Future Directions

5.1. Summary of Key Insights

5.2. Practical Applications

5.3. Future Research Directions

References

- Smith, A.; Johnson, B.; Brown, C.; Davis, D. Impact of Climate Change on Global Agriculture. Environmental Research Letters 2023, 58, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Povarnitsyna, A. V.; Savin, M. I. Impact of climate change on global agriculture. Trends Dev. Sci. Educ 2022, 84, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, G.; Lata, C.; Manjul, A. S.; Priti; Kumar, N. Integrating Multi-omics Strategies to Enhance Crop Resilience in a Changing Climate. In Cutting Edge Technologies for Developing Future Crop Plants; Singapore; Springer Nature Singapore, 2025; pp. 303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.; Chaudhary, N. Integrating Multi-omics Approaches for Crop Resilience Under Changing Climatic Conditions. In Microbial Omics in Environment and Health; Singapore; Springer Nature Singapore, 2024; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, U.; Mahmood, S.; Shahid, N.; Imran, M.; Siddique, M.; Abrar, M. Multi-omics approaches for strategic improvements of crops under changing climatic conditions. In Principles and practices of OMICS and genome editing for crop improvement; Cham; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, S. A. U.; Bashir, T.; Roberts, T. H.; Husaini, A. M. Ameliorating the effects of multiple stresses on agronomic traits in crops: Modern biotechnological and omics approaches. Molecular Biology Reports 2024, 51(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Khare, T.; Zhang, X.; Rahman, M. M.; Hussain, M.; Gill, S. S.; Varshney, R. K. Novel Strategies for Designing Climate-Smart Crops to Ensure Sustainable Agriculture and Future Food Security. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture and Environment 2025, 4(2), e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messmer, R. E. The genetic dissection of key factors involved in the drought tolerance of tropical maize (Zea mays L.). Doctoral dissertation, ETH Zurich, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- BYAKOD, M. Evaluation of maize genotypes for moisture stress condition. Doctoral dissertation, UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES, DHARWAD, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. S. Marker-assisted selection for terminal drought tolerance in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.). Doctoral dissertation, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, A. B. Genetic Diversity Analysis of Lowland Sorghum [Sorghum Bicolor (L.) Moench) Landraces Under Moisture Stress Conditions and Breeding for Drought Tolerance in North Eastern Ethiopia. Doctoral dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kole, C. (Ed.) Cereals and millets; Springer Science & Business Media, 2006; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap, S. K. Effect of crop establishment methods and irrigation scheduling on growth, yield and water productivity of wheat in rice-wheat system. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Agronomy Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Banaras Hindu University Varanasi, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, A.; Adhikari, C.; Manandhar, D.; Bhattarai, S.; Shrestha, S. Effect of abiotic stress in wheat: a review. Reviews In Food And Agriculture 2021, 2(2), 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, F.; Xin, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, X.; Qi, Z. Multi-omics techniques for soybean molecular breeding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(9), 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, R.; Zhao, Q. Multi-omics techniques in genetic studies and breeding of forest plants. Forests 2023, 14(6), 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hina, A.; Abbasi, A.; Arshad, M.; Imtiaz, S.; Shahid, S.; Bibi, I.; Abdelsalam, N. R. Utilization of Multi-Omics Approaches for Crop Improvement; OMICs-based Techniques for Global Food Security, 2024; pp. 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yue, D.; Hong, J.; Wu, J.; Chong, Y. Pan-omics in sheep: Unveiling genetic landscapes. Animals 2024, 14(2), 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Luo, J.; Xiao, Y. Multi-omics assists genomic prediction of maize yield with machine learning approaches. Molecular Breeding 2024, 44(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandohee, J.; Basu, R.; Dasgupta, S.; Sundarrajan, P.; Shaikh, N.; Patel, N.; Noor, A. Applications of multi-omics approaches for food and nutritional security. In Sustainable Agriculture in the Era of the OMICs Revolution; Cham; Springer International Publishing, 2023; pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, S. E.; Bae, D. Y.; Ki, J. S.; Ahn, C. Y.; Rhee, J. S. The importance of multi-omics approaches for the health assessment of freshwater ecosystems. Molecular & Cellular Toxicology 2023, 19(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhija, N.; Kanaka, K. K.; Goli, R. C.; Kapoor, P.; Sivalingam, J.; Verma, A.; Malik, A. A. The flight of chicken genomics and allied omics-a mini review. Ecological Genetics and Genomics 2023, 29, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, P. H.; Baiya, S.; Lee, C. W.; Tseng, C. W.; Chen, S. Y.; Huang, Y. H.; Kao, C. F. Identification of key drought-tolerant genes in soybean using an integrative data-driven feature engineering pipeline. Journal of Big Data 2025, 12(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Pramanik, R.; Chongder, D. B.; Bania, P.; Debnath, S. Integrated Molecular Strategies for Enhanced Production of Anti-Cancer Compounds from Medicinal Plants. In Biotechnology, Multiple Omics, and Precision Breeding in Medicinal Plants; CRC Press, 2025; pp. 270–286. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Li, R.; Zhao, Q. Multi-Omics Techniques for Forest Plant Breeding. Preprints. org 2023, 2023040549. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, T.; Singh, S. P.; Bhardwaj, A.; Srivastava, D.; Kumar, R. Prospects of microgreens as budding living functional food: Breeding and biofortification through OMICS and other approaches for nutritional security. Frontiers in genetics 2023, 14, 1053810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Ren, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Lei, C.; Chai, R.; Lu, D. Strategies to improve the efficiency and quality of mutant breeding using heavy-ion beam irradiation. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2024, 44(5), 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TWN, W.; Aleander, T. M.; Allard, P. M.; Capdevila, P.; Salguero-Gomez, R. The power of the metalobome for ecology. Journal of Ecology 2022, 110(1). [Google Scholar]

- Yue, C.; Cao, H.; Zhang, S.; Shen, G.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Zeng, L. Multilayer omics landscape analyses reveal the regulatory responses of tea plants to drought stress. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, R.; Das, S. P.; Gupta, A.; Parihar, P.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Sarker, U.; Sudhakar, C. Multi-omics pipeline and omics-integration approach to decipher plant’s abiotic stress tolerance responses. Genes 2023, 14(6), 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Mehta, D.; Uhrig, R. G.; Brąszewska, A.; Novak, O.; Fontana, I. M.; Marzec, M. Multi-omics insights into the positive role of strigolactone perception in barley drought response. BMC Plant Biology 2023, 23(1), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, V.; Rajendran, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Runthala, A.; Madhesh, V.; Swaminathan, G.; Ramesh, M. Multi-Omics Approaches Against Abiotic and Biotic Stress—A Review. Plants 2025, 14(6), 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Tian, H.; Xiong, J.; Lu, J.; Liao, S.; Xie, Y. Multilayered omics reveals PEG6000 stimulated drought tolerance mechanisms in white clover (Trifolium repens L.). Industrial Crops and Products 2025, 226, 120722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, M. S.; Kunert, K. J.; Cullis, C. A.; Botha, A. M. Unlocking Wheat Drought Tolerance: The Synergy of Omics Data and Computational Intelligence. Food and Energy Security 2024, 13(6), e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Wei, X.; Sun, Y.; Dong, S. Molecular mechanism of drought resistance in soybean roots revealed using physiological and multi-omics analyses. Plant physiology and biochemistry 2024, 208, 108451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Yoshida, T.; Stiegert, S.; Jing, Y.; Alseekh, S.; Lenhard, M.; Fernie, A. R. Multi-omics approach reveals the contribution of KLU to leaf longevity and drought tolerance. Plant Physiology 2021, 185(2), 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Ai, X.; Li, R.; Yu, H. LncRNA-mediated ceRNA networks provide novel potential biomarkers for peanut drought tolerance. Physiologia Plantarum 2022, 174(1), e13610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, E.; Frugis, G.; Martinelli, F.; Benny, J.; Paffetti, D.; Buti, M. A comparative transcriptomic meta-analysis revealed conserved key genes and regulatory networks involved in drought tolerance in cereal crops. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(23), 13062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Ni, S. J.; Zhang, G. P. Transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals regulatory networks and key genes controlling barley malting quality in responses to drought stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 152, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosová, K.; Vítámvás, P.; Urban, M. O.; Klíma, M.; Roy, A.; Prášil, I. T. Biological networks underlying abiotic stress tolerance in temperate crops—a proteomic perspective. International journal of molecular sciences 2015, 16(9), 20913–20942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, A.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Dossa, K.; Zhang, X. Transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling of drought-tolerant and susceptible sesame genotypes in response to drought stress. BMC plant biology 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, B.; Golkari, S. Identification of gene expression signature for drought stress response in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) using machine learning approach. Current Plant Biology 2024, 39, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volyanskaya, A. R.; Antropova, E. A.; Zubairova, U. S.; Demenkov, P. S.; Venzel, A. S.; Orlov, Y. L.; Ivanisenko, V. A. Reconstruction and analysis of the gene regulatory network for cell wall function in Arabidopsis thaliana L. leaves in response to water deficit. Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding 2023, 27(8), 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Chaudhary, N. Integrating Multi-omics Approaches for Crop Resilience Under Changing Climatic Conditions. In Microbial Omics in Environment and Health; Singapore; Springer Nature Singapore, 2024; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zenda, T.; Liu, S.; Dong, A.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Duan, H. Omics-facilitated crop improvement for climate resilience and superior nutritive value. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 774994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. Strategic Short Note: Integration of Multiomics Approaches for Sustainable Crop Improvement. In IoT and AI in Agriculture: Smart Automation Systems for increasing Agricultural Productivity to Achieve SDGs and Society; Singapore; Springer Nature Singapore, 2024; Volume 5.0, pp. 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bohra, A.; Satheesh Naik, S. J.; Kumari, A.; Tiwari, A.; Joshi, R. Integrating phenomics with breeding for climate-smart agriculture; Omics Technologies for Sustainable Agriculture and Global Food Security, 2021; (Vol II), pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, A.; Bashir, S.; Khare, T.; Karikari, B.; Copeland, R. G.; Jamla, M.; Varshney, R. K. Temperature-smart plants: A new horizon with omics-driven plant breeding. Physiologia Plantarum 2024, 176(1), e14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Pierides, I.; Zhang, S.; Schwarzerova, J.; Ghatak, A.; Weckwerth, W. Multiomics for crop improvement. In Frontier technologies for crop improvement; Singapore; Springer Nature Singapore, 2024; pp. 107–141. [Google Scholar]

- Havrlentová, M.; Kraic, J.; Gregusová, V.; Kovácsová, B. Drought stress in cereals–a review. Agriculture 2021, 67(2), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenda, T.; Liu, S.; Duan, H. Adapting cereal grain crops to drought stress: 2020 and beyond, 2020.

- Hadebe, S. T.; Modi, A. T.; Mabhaudhi, T. Drought tolerance and water use of cereal crops: A focus on sorghum as a food security crop in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2017, 203(3), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begna, T. Impact of drought stress on crop production and its management options. Int. J. Res. Agron 2022, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, A.; Mastrangelo, A. M.; De Leonardis, A. M.; Galiba, G.; Roncaglia, E.; Ferrari, F.; Cattivelli, L. Transcriptional profiling in response to terminal drought stress reveals differential responses along the wheat genome. BMC genomics 2009, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, P. B. K.; Rajesh, K.; Reddy, P. S.; Seiler, C.; Sreenivasulu, N. Drought stress tolerance mechanisms in barley and its relevance to cereals; Biotechnological approaches to barley improvement, 2014; pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Monneveux, P.; Ramírez, D. A.; Pino, M. T. Drought tolerance in potato (S. tuberosum L.): Can we learn from drought tolerance research in cereals? Plant Science 2013, 205, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogawat, A.; Yadav, B.; Chhaya; Lakra, N.; Singh, A. K.; Narayan, O. P. Crosstalk between phytohormones and secondary metabolites in the drought stress tolerance of crop plants: a review. Physiologia Plantarum 2021, 172(2), 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M. A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W. B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F. Applications of multi-omics technologies for crop improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 563953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, S. G.; Gold, K. M.; Jiménez-Gasco, M. D. M.; Filgueiras, C. C.; Willett, D. S. A multi-omics approach to solving problems in plant disease ecology. PLoS One 2020, 15(9), e0237975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Marshall, R. S.; Li, F. Understanding and exploiting the roles of autophagy in plants through multi-omics approaches. Plant Science 2018, 274, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B. L.; Chen, L. H.; Chen, L. L.; Guo, H. Integrative Multi-Omics Approaches for Identifying and Characterizing Biological Elements in Crop Traits: Current Progress and Future Prospects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(4), 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, V.; Rajendran, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Runthala, A.; Madhesh, V.; Swaminathan, G.; Ramesh, M. Multi-Omics Approaches Against Abiotic and Biotic Stress—A Review. Plants 2025, 14(6), 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, T.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sharma, S.; Sohal, J. S.; Singh, S. V. Multi-omics approaches for understanding stressor-induced physiological changes in plants: An updated overview. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology 2023, 126, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, A. Multi-omics-based discovery of plant signaling molecules. Metabolites 2022, 12(1), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Saand, M. A.; Huang, L.; Abdelaal, W. B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F. Applications of multi-omics technologies for crop improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 563953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, I. N.; Remali, J.; Azizan, K. A.; Nor Muhammad, N. A.; Arita, M.; Goh, H. H.; Aizat, W. M. Systematic multi-omics integration (MOI) approach in plant systems biology. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X. Single-cell and spatial multi-omics in the plant sciences: Technical advances, applications, and perspectives. Plant Communications 2023, 4(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, T.; De Rybel, B.; Vandepoele, K. Charting plant gene functions in the multi-omics and single-cell era. Trends in Plant Science 2023, 28(3), 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B. L.; Chen, L. H.; Chen, L. L.; Guo, H. Integrative Multi-Omics Approaches for Identifying and Characterizing Biological Elements in Crop Traits: Current Progress and Future Prospects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(4), 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, F.; Xin, D.; Liu, C.; Wu, X.; Qi, Z. Multi-omics techniques for soybean molecular breeding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(9), 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P. E.; Sreedasyam, A.; Trivedi, G.; Desai, S.; Dai, Y.; Cseke, L. J.; Collart, F. R. Multi-omics approach identifies molecular mechanisms of plant-fungus mycorrhizal interaction. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 6, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).