1. Introduction

Dwarf galaxies, especially the ultra-faint ones (UFDs), are mostly made of dark matter. They can have hundreds or even thousands of times more dark matter than visible matter [

1]. Because of this, they serve as exceptional natural environments for investigating dark matter and its gravitational in-fluence. By analyzing how stars move within these galaxies, astronomers can gather essential data to refine and test theoretical models of dark matter [

2]. Dwarf galaxies serve as important tools for testing the Cold Dark Matter (CDM) model, which is currently the most widely accepted framework in cosmology. There are ongoing challenges because simulations don't always match what we observe. For instance, there's the missing satellite problem, where we see fewer dwarf galaxies than predicted, and the core-cusp problem, which is a discrepancy in how dark matter is distributed within galaxy halos [

3]. These issues are crucial for improving our understanding of both dark matter behavior and galaxy formation processes [

4,

5].

Dwarf galaxies are regarded as the foundational components from which larger galaxies are assembled. According to the hierarchical model of galaxy formation, massive systems like the Milky Way have developed over time by merging with and absorbing numerous smaller dwarf galaxies [

6]. Due to their shallow gravitational potential wells, dwarf galaxies are particularly vulnerable to environmental influences such as tidal stripping and rampressure stripping caused by nearby massive galaxies [

7]. Examining these interactions provides valuable insights into how external conditions influence galaxy evolution. Dwarf galaxies also display diverse star formation histories from inactive to highly bursty phases and their low metal content and structural simplicity make them excellent subjects for exploring star formation processes, especially under extreme conditions [

1].

2. What Is Dwarf Galaxies?

Dwarf galaxies are currently a hot topic in astronomy because they offer crucial insights into several fundamental areas [

8,

9]. They were instrumental in developing the idea of stellar populations (groups of stars with similar origins), and they are key to understanding how elements evolve within galaxies and how dark matter is distributed. Furthermore, studying dwarf galaxies could be vital for unraveling the mysteries of galaxy formation and evolution. As a working definition all galaxies fainter than M

B≤-16 m (H

0=50) and more extended than global clusters are considered here as dwarfs. But this definition is artificial; the high-surface brightness elliptical M32 (M

B=-15.5 m) is rather an underluminous giant, and SMC (M

B=-17.0 m) may be classified as an overluminous dwarf. Indeed the physical meaning of dwarfs is probably much deeper. It seems that dwarfs form a separate class of galaxies [

10].

Dwarf galaxies stand apart from “giant” galaxies due to several distinct characteristics. They generally have lower stellar masses and are fainter in optical light. Structurally, they exhibit lower stellar concentration (meaning their surface brightness is less intense) and possess a unique morphological appearance [

11]. Because of these variations, the precise definition of a dwarf galaxy can differ slightly across scientific studies, depending on the specific property being examined.

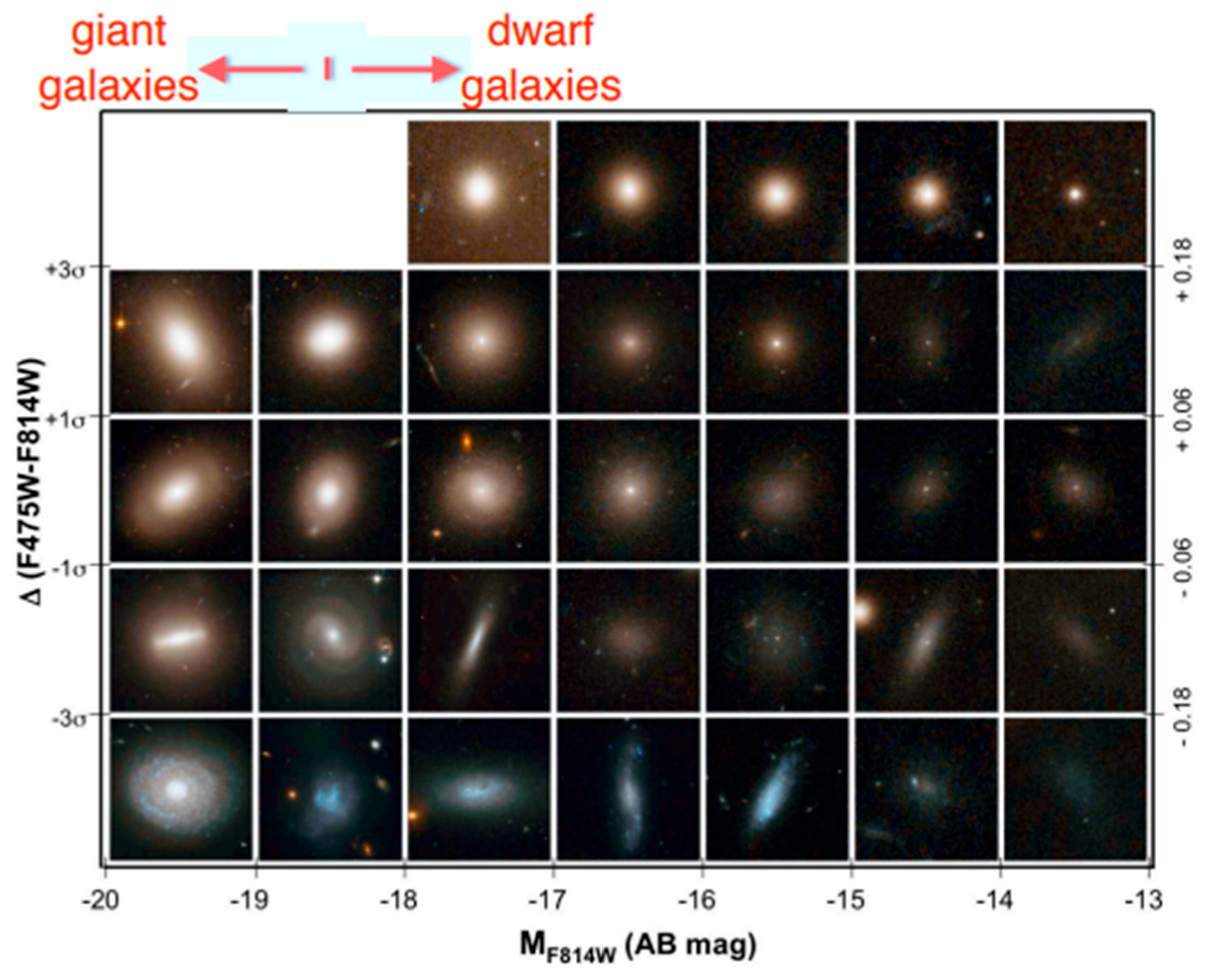

Figure 1 illustrates these differences using an optical Color-Magnitude Diagram (CMD) for galaxies in the Coma cluster.

This CMD replaces data points with actual image cutouts from high-resolution Hubble Space Telescope observations, showcasing typical examples across various regions of color space. The middle row of the CMD represents the “red sequence” of galaxies. A significant challenge in studying dwarf galaxies becomes evident in this figure: their decreasing surface brightness at fainter optical magnitudes makes them harder to detect and analyze [

12].

An examination of the Palomar Sky Survey images of galaxy clusters reveals a group of faint objects that can be identified based on two main features:

A) they have low surface brightness, and

B) they show little or no central light concentration on the red images.

Since these objects appear more commonly in galaxy clusters than in the general field, it is likely that they are dwarf galaxies. This assumption is further supported by their resemblance to known dwarf galaxies in the Local Group. Most objects meeting both criteria A and B are likely dwarf galaxies. However, it’s important to note that not all known or suspected dwarf galaxies meet both conditions [

13].

Dwarf galaxies are key to studying galaxy formation, dark matter, and stellar evolution.They are characterized by low luminosity, low mass, and diffuse structure. Classification is complex, with overlaps between dwarfs and underluminous giants. Observational challenges arise from their faintness, requiring advanced detection methods. More research is needed to understand their full significance in astrophysics.

Globular clusters and dwarf galaxies are both systems of stars held together by gravity, yet they differ notably in terms of structure, composition, and development. Globular clusters are dense, spherical groupings of stars, generally only a few parsecs in size, and contain up to a few million ancient, metal-poor stars [

14]. They typically have low mass-to-light ratios and show minimal signs of dark matter [

15]. Dwarf galaxies, on the other hand, are much larger—ranging from hundreds to thousands of parsecs—and have more intricate star formation histories, often including multiple stellar generations and a broad range of metallicities. A key trait of dwarf galaxies is their high mass-to-light ratios, suggesting significant dark matter content [

16]. Unlike the more compact and dynamically evolved globular clusters, which often show signs of mass segregation, dwarf galaxies are more diffuse and evolve more slowly, with less evidence of internal mass sorting. While globular clusters are usually thought to have formed within larger galaxies, dwarf galaxies are believed to have originated independently within their own dark matter halos. Some objects, like Omega Centauri, challenge this classification and may actually be the stripped cores of former dwarf galaxies [

17]. Thus, for example, if the absolute magnitude M

V of the host galaxy is equal to or brighter than -22.5 m, then its globular cluster systems can be assigned to the brightest systems, while if it is fainter than -17.5 m, then it is among the faintest or dwarf systems [

18].

3. Morphological Types of Dwarf Galaxies

Dwarf galaxies are generally categorized into three principal types: dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSph), dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrr), and dwarf elliptical galaxies (dE). Among these, dSphs are particularly distinctive, as their stellar masses are comparable to those of Galactic globular clusters, yet they possess significantly larger spatial extents. The shallow gravitational potentials and low average densities of dSphs render them highly susceptible to environmental influences; even low levels of star formation can substantially affect the structural evolution of their gaseous progenitors. Consequently, this study focuses on examining the mech-anisms of star formation within these systems [

19].

3.1. Dwarf Spiral Galaxies

Dwarf spiral galaxies are a type of galaxy that falls within the S0 to Sd range. They are characterized by a low central surface brightness (μ

V≥23 mag arcsec

-2), low hydrogen (HI) mass (M

HI ≤ 10

9 M

⊙), and high mass-to-light ratios. These galaxies are at the heavier end of the dwarf galaxy spectrum. Earlier types of these galaxies have rotation curves that are typical of rotating disks, while later types either spin slowly or rotate as a single solid body. These galaxies typically experience gradual, ongoing star formation. Later-type dwarf spirals generally contain less gas and metals compared to earlier types. The most extreme late-type spirals might be evolving into irregular galaxies. Dwarf spirals can be found both in galaxy clusters and in isolated (field) environments [

20].

3.2. Blue Compact Dwarf Galaxies (BCD)

Blue compact dwarf galaxies (BCDs) are small galaxies known for their rapid star formation, which is concentrated in the center. This concentration of gas and stars makes them look very compact, powers their starburst activity, and gives them a high central surface brightness (μ

V ≥ 19 mag arcsec⁻²). Some BCDs are also classified as HI-rich galaxies, blue amorphous galaxies, or low-mass Wolf-Rayet galaxies. They have hydrogen (HI) masses of M

HI ≤ 10⁹ M⊙, which can be greater than their stellar mass. While the inner regions of BCDs rotate like a solid body, the extended gas around them may move independently. These galaxies are often found in relatively isolated areas, away from crowded galaxy clusters [

20].

3.3. Dwarf Irregular Galaxies (dIrr)

Dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrr) have a disorganized appearance. In optical images, they often feature scattered bright H II regions. When observed using hydrogen (HI) data, these galaxies reveal a complex, fractal-like structure of gas, containing many shells and clumps. In more massive dIrrs, the HI gas typically extends far beyond even the oldest stars. Some of these galaxies also show signs of gas accretion. In lower-mass dIrrs, the HI gas may be misaligned with the distribution of starlight—either shifted from the center or forming a ring-like shape with a central gap. dIrr are characterized by (μ

V≥23 mag arcsec

-2, M

HI ≤ 10

9 M

⊙), and Mtot≤ 1010 M

⊙. In more massive dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrrs), chemical enrichment tends to increase in younger stellar populations. In contrast, low-mass dIrrs often show clear differences between the spatial distribution and motion of gas and stars. Solid-body rotation is typical in higher-mass dIrrs, while some low-mass ones may lack any detectable rotation. dIrrs are found in various environments, including clusters, groups, and isolated (field) regions, but they are not strongly clustered around large galaxies. Massive dIrrs can sustain star formation over the course of a Hubble time, whereas very low-mass, gas-deficient dIrrs might be transitioning into dwarf spheroidal galaxies [

20].

Dwarf irregular (dIrr) galaxies share several characteristics with dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies, yet they are distinguished by the presence of neutral hydrogen (HI) gas—often comprising a significant portion of their mass and ongoing or recent star formation activity. Both types of galaxies harbor an older stellar population. It has been suggested that dIrr galaxies might represent dSph galaxies in a more active evolutionary phase. A small dIrr galaxy that ceases star formation for several hundred million years could resemble a dSph. Nonetheless, dIrr galaxies generally exhibit a more continuous and stable star formation rate (SFR) over time and tend to reach higher metallicities compared to dSph. This may be due to their greater mass, allowing them to retain their interstellar medium (ISM) despite supernova-driven outflows, or due to reduced environmental disruption, as they are often located farther from massive galaxies. These factors enable dIrr galaxies to maintain prolonged, albeit low-level, star formation throughout their evolution [

21].

3.4. Dwarf Elliptical Galaxies (dE)

Dwarf elliptical (dE) galaxies are spherical or elliptical in shape, compact, and have high central stellar densities. They are typically fainter than M

V=-17 mag, with a surface brightness of μ

V≥21 mag arcsec

-2, a hydrogen (HI) mass of M

HI ≤ 10⁵ M

⊙, and a total mass of Mtot ≤ 10⁹ M⊙. These galaxies are usually found close to larger galaxies, contain very little to no gas, and generally lack rotational support. If gas is present, it might be unevenly distributed, less extended than the starlight, and may move differently from the main galaxy structure. Some dEs have a noticeable nucleus, which can account for up to 20% of the galaxy's light. More luminous dEs are more likely to have a nucleus. The surface density profiles of dEs and their nucleated counterparts (dE(N)s) are best described by Sersic's [

22] generalization of a de Vaucouleurs r

1/4 law and exponential profiles [

20].

3.5. Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxies (dSph)

Dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSphs) are very faint, low-mass galaxies with little central light concentration and almost no gas. They have a total magnitude of M

V≥-14 mag, a surface brightness of µ

V≥21 mag arcsec

-2, and a total mass of Mtot ≈10⁹ M

⊙. These are the faintest and least massive galaxies we know of. They are typically found near larger galaxies and don't show signs of rotation. Their velocity dispersions suggest that they contain a lot of dark matter. The different locations of dSphs and dEs compared to dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrrs) is called morphological segregation, which suggests that their environment plays a role in how they evolve [

20].

Dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies represent the smallest and least luminous galaxy type currently known. Within the Local Group, they predominantly exist as satellites orbiting more massive galaxies, such as the Milky Way and M31. While some dSph galaxies formed the entirety of their stellar content over 10–12 billion years ago and have remained inactive since, others formed most of their stars during intermediate epochs, approximately 6–8 billion years ago. A small subset has undergone star formation as recently as 1–2 billion years ago. Despite this diversity, all dSph galaxies contain a population of ancient stars. Even those considered the oldest and most quiescent exhibit complex star formation histories (SFHs), and despite similarities in their SFHs, their color–magnitude diagrams (CMDs) often differ, possibly due to variations in environmental conditions. The evolution of dSph galaxies is likely shaped, perhaps significantly, by their interactions with the Milky Way. Orbital dynamics, particularly dynamical friction, may influence their star formation rates. Currently, none of the Milky Way’s dSph satellites shows clear evidence of retaining inter-stellar medium (ISM) [

21,

23].

3.6. Ultra-Faint Dwarf Galaxies (UFD)

Ultra-faint dwarf galaxies (UFDs) are the faintest galaxies known in the Universe, with, by definition, a V-band luminosity of fainter than L

V=10

5 L

⊙, M

V<-7,7. Some of these galaxies, such as Triangulum II or Segue II, can be extremely faint—just a few hundred times the luminosity of the Sun. Ultra-faint dwarf galaxies (UFDs) are composed mainly of very old stars, older than 10 billion years. Their structure and shape have been the subject of ongoing debate for more than 15 years. It was soon discovered that UFDs are generally elongated, with an average ellipticity of around 0.4. Such a relatively elongated shape has been postulated to result from tidal interaction with the Milky Way [

24].

4. Mass of Dwarf Galaxies and Methods for Determining Mass

To determine a galaxy's kinematic mass, we need to measure its velocity dispersion (for galaxies supported by pressure) or its rotation velocity (for galaxies supported by rotation). We also need to determine an appropriate scale length and the galaxy's luminosity density or total luminosity to calculate its mass-to-light ratio [

25,

26]. The scale length chosen for the calculation depends on the dynamic model. For non-rotating dwarf galaxies, the King core radius or exponential scale length is used, while for rotating galaxies, the scale is derived from the rotation curve [

27,

28].

dSph galaxies. Because they generally lack an ISM component, and because they have such low surface brightnesses, the internal kinematics of most LG dSph galaxies are based on high precision spectroscopic radial velocities of individual stars. At least four ongoing criticisms have been raised regarding the reliability of dSph kinematic measurements obtained using this approach.

dIrr galaxies. Established methods are available for constructing rotation curves of dwarf irregular (dIrr) galaxies both within and outside the Local Group. We only see dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrrs) in the Local Group where rotation isn't the primary force governing their movement at every radius. For example, GR 8 shows rotational motion in its inner parts but shifts to pressure support in the outer regions. In gas-rich dIrr galaxies that lack rotation, velocity dispersion is typically measured using the width of the 21-cm hydrogen line [

29].

Precisely mapping the mass distributions of low-mass dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies provides a way to test predictions from dark matter (DM) theories. So far, most of these studies have focused on the satellite galaxies of the Milky Way. In contrast, although the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) hosts 35 known dwarf galaxies, only two have been thoroughly mass modeled. To gain deeper insights into the nature of dark matter, a broader investigation of Local Group dwarf galaxies is needed. In this context, the authors have conducted a dynamical analysis of two relatively luminous Andromeda satellites: Andromeda VI (And VI) and Andromeda XXIII (And XXIII). Author’s infer an enclosed mass for And XXIII of M(r < r

h) = (3.1 ± 1.9) × 10

7 M

⊙, corresponding to a mass-to-light ratio of [

M/

L]

rh = (90.2 ± 53.9) M

⊙/L

⊙. Using the dynamical Jeans modeling tool, GravSphere, we determine And VI and And XXIII’s dark matter density at 150 pc, finding

ρDM,VI (150 pc) = (1.4 ± 0.5) ×10

8 M

⊙ kpc

−3 and

ρDM,XXIII (150 pc) =0.5+0.4 −0.3 × 10

8 M

⊙ kpc

−3 . The authors' findings identify Andromeda VI (And VI) as the first M31 satellite to exhibit a cuspy central dark matter profile based on mass modeling, whereas Andromeda XXIII (And XXIII) shows a lower central density. This lower density may indicate either a cored dark matter distribution or a reduction in density caused by tidal interactions. Since And XXIII was quenched early in its evolution, the formation of a dark matter core through repeated gas inflows and outflows driven by cooling and stellar feedback is unlikely. This places And XXIII among a growing number of M31 dwarf galaxies with central densities lower than those of most Milky Way dwarfs, and also lower than predicted for isolated dwarfs under the Standard Cosmological Model. One possible explanation is that M31’s dwarf satellites have undergone stronger tidal effects than those orbiting the Milky Way [

30].

5. Formation and Evolution Dwarf Galaxies

Dwarf galaxies rank among the smallest and most numerous galactic systems in the cosmos and play an essential role in the hierarchical process of galaxy formation. The ΛCDM model suggests that they originated from the early gravitational collapse of localized dark matter concentrations, which subsequently attracted baryonic matter that cooled and triggered star formation [

31]. These systems typically underwent brief, intense bursts of star formation early on, leading to the creation of metal-poor stars [

32]. However, mechanisms like cosmic reionization and stellar feedback often curtailed further star formation by heating or expelling the gas needed to form new stars [

33]. Environmental influences, such as tidal forces and ram pressure from larger galaxies, also played a significant role in reshaping these systems, frequently halting star formation altogether and converting gas-rich dwarf irregular galaxies into gas-poor dwarf spheroidals [

34]. Although small in mass, dwarf galaxies possess rich and varied chemical evolution patterns, including evidence for multiple generations of stars and complex enrichment processes. Their dark matter-dominated structures, vulnerability to feedback, and diverse developmental paths make them powerful tools for studying galaxy evolution and the nature of dark matter on smaller cosmic scales.

The formation and evolution of dwarf galaxies appear to diverge significantly from that of “normal” galaxies. However, the standard theory of galaxy evolution suggests that all galaxies, except for the very smallest, are constructed through the successive mergers and accretions of smaller collections of stars, gas, and dark matter. A major component of the universe, 90% of its matter, is dark matter detectable only through its gravitational effects and still largely a mystery. If this dark matter is “cold” and present when Big Bang light propagated across galactic distances, then the universe’s expansion would have caused initial density fluctuations to become gravitationally bound and stable. Unlike dark matter, the gas in these early proto-galaxies can cool down by releasing energy. This allows the gas to gather and form dense cores within the dark matter halos. Once this gas becomes dense and cool enough, star formation begins, marking the birth of a galaxy. The hierarchical growth of cosmic structures like galaxies and galaxy clusters occurs as these small, dense regions merge. This implies that the matter we observe in a bright galaxy today is a composite of many original protogalactic fragments [

35].

The dwarf galaxies we see now are those that escaped absorption by larger galaxies, making them “survivors”. It’s possible that these modern dwarf galaxies differ fundamentally from most of the early fragments that combined to create massive galaxies. Nonetheless, studying the features of contemporary dwarf galaxies provides vital data for evaluating the theory of hierarchical structure formation. A rapid onset of star for motion after gravitational collapse of dense regions would imply that the stars in these surviving local dwarf galaxies are very old, given that their surrounding dark matter halos would have been among the universe’s earliest formations [

36].

Explaining the disparities between observed dwarf galaxies and the standard model of galaxy evolution necessitates unique astrophysical explanations for dwarf galaxy development compared to giant galaxies. Their low masses and shallow gravitational potential make dwarf galaxies inherently fragile. Processes such as radiation and supernovae from their earliest stars can lead to the breakdown, heating, and expulsion of gas, thus suppressing future star formation. Moreover, the strong background of ultraviolet photons during the universe's early “re-ionization” phase might have photo-ionized or even “photo-evaporated” their small gaseous halos. Finally, the history of star formation within dwarf galaxies can be shaped by their surrounding environment and interactions with other galaxies [

36].

6. Dwarf Galaxy Catalogs

One of the first catalogs of dwarf galaxies was created by Sidney van den Bergh [

13]. A catalog of dwarf galaxies located north of declination −23° was created using images from the Palomar Sky Survey. The results show that dwarf galaxies are not evenly spread across the sky. A notable cluster of dwarf irregular galaxies is observed near the galaxy M94 in the Canes Venatici constellation.

A catalog containing 846 dwarf galaxies within a 200 square degree area of the Virgo region has been compiled. Among them, 634 (75%) are classified as dwarf ellipticals, 137 (16%) as IC 3475 types, and 73 (9%) as dwarf spirals or irregulars. Additionally, two entries are identified as jets from typically bright galaxies. Notably, at least 20% of the dwarf ellipticals and 29% of the IC 3475 types exhibit stellar or quasi-stellar nuclei. The catalog is derived from nine deep-exposure images taken with the Palomar 48-inch (1.2 m) Schmidt telescope using IIIa-J plates, capturing galaxies with apparent diameters as small as 0.3 arcminutes and down to a limiting magnitude of approximately 19. For each galaxy, the catalog provides position coordinates (epoch 1950.0), apparent size, morphological type, an estimate of central light concentration, and a brightness assessment. The spatial distribution of the dwarf ellipticals and IC 3475 types closely resembles that of the standard galaxies comprising the Virgo Cluster, suggesting that these dwarf types are genuine members of the cluster. In contrast, dwarf spirals and possibly dwarf irregulars do not seem to be associated with the cluster. The catalog also briefly mentions the discovery of two new GR 8-type extreme dwarf irregular galaxies [

37].

A catalog presents 145 dwarf elliptical galaxies within the Fornax cluster and is considered complete down to a blue magnitude of 18.5, although some galaxies with luminosities two magnitudes fainter have also been identified. Compared to brighter galaxies, the dwarf ellipticals show a less concentrated distribution toward the cluster center. The proportion of dwarf ellipticals relative to normal ellipticals is notably lower in Fornax than in the Virgo cluster. However, the ratio of dwarf ellipticals to actively star-forming galaxies (such as spirals and irregulars) is comparable in both clusters. Interestingly, the velocity distribution of both the dwarf ellipticals and the star-forming galaxies in Fornax deviates from a Gaussian profile, whereas the velocity distribution for elliptical and lenticular (E/S0) galaxies does follow a Gaussian pattern. The E/S0 galaxies also show a relatively low velocity dispersion of around 300 km s

-1 [

38].

The dwarf galaxies within the Local Group provide an exceptional opportunity to study the detailed characteristics of the most prevalent galaxy type in the Universe. This review presents an updated census of Local Group dwarf galaxies, incorporating the latest measurements of distances and radial velocities. It explores various aspects of these systems, including: (a) their integrated photometric properties and optical structures, (b) the composition, nature, and spatial distribution of their interstellar medium (ISM), (c) heavy-element abundances inferred from both stellar populations and nebulae, (d) their diverse and complex star formation histories, (e) internal kinematics, with particular attention to their significance for the dark matter problem and alternative frameworks, and (f) evidence of interactions past, present, and potential future with other galaxies within and beyond the Local Group. In support of this discussion and to aid future research, the review includes comprehensive tables summarizing current observational data and knowledge gaps regarding these nearby dwarf galaxies. Despite significant advancements over the past decade, many unresolved questions remain, ensuring that the Local Group will continue to play a central role in the study of galaxy evolution [

29].

The Local Volume Database (LVDB) is introduced as a comprehensive catalog encompassing observed properties of dwarf galaxies and star clusters within the Local Group and the broader Local Volume. It compiles data on positional, structural, kinematic, chemical, and dynamical characteristics of these systems. Special attention is given to catalogs featuring faint and compact Milky Way systems with ambiguous classifications, newly identified Milky Way globular clusters and candidates, as well as globular clusters residing in nearby dwarf galaxies. The LVDB currently offers full coverage of known dwarf galaxies within approximately 3 megaparsecs, with ongoing efforts to extend its scope to include resolved stellar systems across the Local Volume. Publicly accessible examples and use cases of the LVDB are presented, focusing on the census and statistical properties of Local Group populations, alongside some theoretical implications. The coming decade is expected to be transformative for near-field cosmology, with upcoming missions and surveys including the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, the Euclid mission, and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope anticipated to both discover new systems and provide unprecedented detail on known dwarf galaxies and star clusters [

39].

This catalog [

40] presents a detailed compilation of the positional, structural, and dynamical properties of dwarf galaxies located within and around the Local Group. It includes over 100 nearby galaxies with reliably determined distances placing them within 3 Mpc of the Sun. These systems span a diverse range of environments, including satellites of the Milky Way (MW) and Andromeda (M31), quasi-isolated galaxies with-in the Local Group outskirts, and numerous isolated dwarfs beyond its boundaries. Galaxies associated with nearby groups such as Maffei, Sculptor, and IC 342 are intentionally excluded. The catalog compiles key observational parameters distances, velocities, luminosities, mean stellar metallicities, structural dimensions, and dynamical characteristics which have been homogenized where possible and organized into standardized tables. The provenance and potential uncertainties of the tabulated values are critically discussed. Addition-ally, the spatial structure and membership of the MW and M31 subgroups, as well as the Local Group as a whole, are explored. The morphological variety of the dwarf galaxy population and its subgroups is analyzed, along with estimated timescales related to orbital motions and interaction histories. Scaling relations and trends in mean stellar metallicity are examined, and a potential floor in central surface brightness and possibly in stellar metallicity at low luminosities is considered.

Researchers have compiled a substantial collection of observational data on dwarf galaxies, leading to the creation of a composite catalog covering systems located within 121 megaparsecs. This catalog documents key physical properties of 413 dwarf galaxies, including equatorial coordinates, distances, absolute stellar magnitudes, masses (in solar masses), redshifts, and apparent magnitudes in the X-ray spectrum. Statistical analysis of the dataset has revealed empirical correlations among major galaxy characteristics. In particular, linear relationships were identified between galaxy mass and absolute magnitude, as well as between mass and distance. The findings demonstrate that galaxy mass increases linearly with both distance and absolute magnitude. However, the study found no significant correlation between redshift and apparent magnitude. Additionally, the spatial distribution of dwarf galaxies shows two prominent groupings—within 10–40 Mpc and 95–120 Mpc—likely linked to the influence of nearby massive galaxies [

41].

7. Star Formation Dwarf Galaxies

Consistent star formation histories (SFHs) for 40 dwarf galaxies in the Local Group have been reconstructed by analyzing color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) generated from archival HST/WFPC2 imaging data. The study reports several key findings based on this analysis. A galaxy’s lifetime star formation history (SFH) can be reliably determined even from a color-magnitude diagram (CMD) that does not extend to the oldest main sequence turnoff (MSTO). When systematic uncertainties in stellar evolution models are properly accounted for, SFHs derived from such shallower CMDs remain consistent with those obtained from deeper CMDs that reach below the oldest MSTO. Nevertheless, only CMDs that include the oldest MSTO allow for precise constraints on the earliest periods of star formation. In the case of sparsely populated systems, such as ultra-faint dwarf galaxies, expanding the survey area or increasing the number of stars near the oldest main sequence turnoff (MSTO) provides more reliable constraints on star formation histories (SFHs) than extremely deep CMDs covering smaller regions. CMDs that extend significantly below the oldest MSTO exhibit similar levels of systematic uncertainty in SFH determination as those reaching the MSTO with moderate signal-to-noise (approximately 1 magnitude below the oldest MSTO). This similarity arises because stars below the oldest MSTO are not strongly sensitive to variations in SFH. Therefore, in low-density systems, the primary limitation on SFH precision is the number of stars present in age-sensitive regions of the CMD such as the subgiant branch (SGB) and MSTO. Consequently, CMDs that include a greater number of stars—usually obtained by covering wider regions—provide more precise and representative star formation histories (SFHs) compared to ultra-deep CMDs confined to smaller fields. On average, the SFHs of dwarf spheroidal (dSph) galaxies exhibit an exponentially decreasing trend, with a typical timescale of around 5 billion years [

42]. In contrast, dwarf irregulars (dIrrs), transition-type dwarfs (dTrans), and dwarf ellipticals (dE) are more accurately described by an exponentially declining star formation history (SFH) up to roughly 10 billion years ago, with characteristic timescales of approximately 3–4 billion years, after which they experienced a period of constant or rising star formation activity. Dwarf galaxies in the Local Group (LG) with stellar masses below 10⁵ solar masses formed over 80% of their total stellar content before redshift z ~ 2, which corresponds to approximately 10 billion years ago. In contrast, more massive LG dwarfs with stellar masses exceeding 10⁵ solar masses—had formed only about 30% of their stars by that same time [

43]. The study explores how this apparent “upsizing” trend could be influenced by observational selection effects and environmental factors within the Local Group. Dwarf spheroidal galaxies (dSphs) with lower luminosities tend to have less extended star formation histories (SFHs) compared to their more luminous counterparts. Nevertheless, the relatively small variation in SFHs among dSphs indicates that stellar mass alone does not fully explain this trend, and that external factors—such as a galaxy's interaction history—have likely played a significant role in shaping their evolution [

44]. Interestingly, some ultra-faint and classical dSph exhibit similar SFHs, suggesting that the distinction between these two categories is somewhat artificial. Furthermore, dwarf irregular galaxies (dIrr) in the Local Group formed a larger proportion of their stellar mass before redshift z = 2 than the star-forming galaxy population observed in the SDSS sample by Leitner [

45]. Although systematic uncertainties and selection effects were considered, no clear explanation was found for this inverse downsizing trend. Additionally, before z = 2, Local Group dIrrs had formed more stellar mass than predicted by the abundance matching models of Behroozi et al. [

46]. These findings highlight the limitations of extrapolating the properties of low-mass galaxies based on trends observed in more massive systems. One possible explanation for the observed discrepancy is that low-mass galaxies may have experienced higher-than-expected star formation efficiencies during the early stages of their evolution [

47].

Star formation in dwarf galaxies is influenced by a range of both external and internal processes. External mechanisms such as ram-pressure stripping, tidal interactions, and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the surrounding environment play a significant role, with the latter potentially inhibiting star formation in the lowest-mass systems. Internally, feedback from massive stars through UV radiation, stellar winds, and supernova explosions can suppress star formation efficiency. This suppression may help ad-dress various theoretical and observational challenges in galaxy formation. In this study, we present recent investigations into the relative significance of these diverse influences on the evolutionary pathways of dwarf galaxies [

48].

8. Conclusions

Although dwarf galaxies have low mass, they play an important role in understanding the evolution of the universe. Their diverse morphological types, star formation histories, and interactions with the environment make them one of the most relevant topics in astrophysics. In recent years, dynamical and photometric methods have been widely used to determine mass. However, there are significant differences between some of these methods, which may be related to observational accuracy and model parameters.

The amount and distribution of dark matter in dwarf galaxies is still not fully understood. In addition, it is important to study the evolutionary processes of dwarf galaxies. Therefore, during our current research, observational data on more than 600 dwarf galaxies up to 121 Mpc were collected and a catalog was created. In our previous studies, regression equations and correlation coefficients between various physical parameters of dwarf galaxies were calculated using catalog data [

49,

50]. Comparable analyses have also been carried out on various other astrophysical systems [

51,

52,

53]. Such comparative research helps confirm the effectiveness of statistical approaches across diverse astronomical objects and offers a wider framework for understanding the findings related to dwarf galaxies.

In the future, the James Webb Space Telescope and other advanced observational instruments will enable a deeper study of the star formation history and chemical evolution of dwarf galaxies. Additionally, the creation of new catalogs of ultra-faint dwarf galaxies is expected to expand the current classification. The results discussed in this paper summarize existing knowledge on dwarf galaxies and serve as a methodological basis for future research.

References

- Simon, J.D. The Faintest Dwarf Galaxies. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2019, 57, 375-415.

- Richstein, H.; Kallivayalil, N. Revealing the Sparse Stellar Populations of Milky Way Ultra-Faint Dwarf Galaxies with Deep Hubble Space Telescope Imaging. American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts 2024, 56(2), 243.

- Del Popolo, A.; Le Delliou, M. Review of Solutions to the Cusp-Core Problem of the ΛCDM Model. Galaxies 2021, 9, 123. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, A. Finding the 99% Today: The Cosmological Role of Dwarf Galaxies. American Astronomical Society 2014, 223, 226.

- Louis, E.S. Galactic searches for dark matter. Physics Reports 2013, 531, 1-88.

- Henkel, C.; Hunt, L.K.; Izotov, Y.I. The Interstellar Medium of Dwarf Galaxies. Galaxies 2022, 10, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rey, S.-C.; Lee, Y. Evidence for Mass-dependent Evolution of Transitional Dwarf Galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. Astrophys. J. 2024, 977, 231. [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Llambay, A.; Navarro, J.F.; Abadi, M.G.; Gottlöber, S.; Yepes, G.; Hoffman, Y.; Steinmetz, M. DWARF GALAXIES AND THE COSMIC WEB. Astrophys. J. 2013, 763, L41. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, B.; Cai, J.; Qu, H.; Zheng, A.; Hao, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Xun, Y. An automatic detection method for small size dwarf galaxy candidates. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 696, A130. [CrossRef]

- Tammann, G.A. Dwarf Galaxies in the Past. European Southern Observatory conference and workshop 1994, 49, 3.

- Cignoni, M.; Sacchi, E.; Tosi, M.; Aloisi, A.; Cook, D.O.; Calzetti, D.; Lee, J.C.; Sabbi, E.; Thilker, D.A.; Adamo, A.; et al. Star Formation Histories of the LEGUS Dwarf Galaxies. III. The Nonbursty Nature of 23 Star-forming Dwarf Galaxies*. Astrophys. J. 2019, 887, 112. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, D.M. Dwarf galaxies in the coma cluster: Star formation properties and evolution. The Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, 2012, Phd thesis ISBN:9781267791672, 74, 166 p.

- Van den Bergh, S. A Catalogue of Dwarf Galaxies. Publications of the David Dunlap Observatory 1959, 2-5, 147-156.

- Harris, W.E. A Catalog of Parameters for Globular Clusters in the Milky Way. Astron. J. 1996, 112, 1487. [CrossRef]

- Gratton, R. G.; Carretta, E.; Bragaglia, A. Multiple populations in globular clusters. Evidence and implications. Astronomy & Astrophysics Review 2012, 20(1), 50.

- Tolstoy, E.; Hill, V.; Tosi, M. Star-Formation Histories, Abundances, and Kinematics of Dwarf Galaxies in the Local Group. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 47, 371–425. [CrossRef]

- Bekki, K.; Kenneth, C. F. Formation of Omega Centauri from an Ancient Nucleated Dwarf Galaxy in the Young Galactic Disc. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2003, 346, L11-L15.

- Tadjibaev, I.U.; Nuritdinov, S.N.; Ganiev, J.M. Globular Star Cluster Systems Around Galaxies. II. Spiral and Dwarf Galaxies. Astrophysics 2015, 58, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.N.; Murray, S.D. Star Formation in Dwarf Galaxies. European Southern Observatory Conference and Workshop Proceedings 1994, 49, 535-543.

- Grebel, E.K. Dwarf Galaxies in the Local Group and in the Local Volume. Dwarf galaxies and their environment 2001, 40, 45-53.

- Tolstoy, E. Dwarf galaxies: Important clues to galaxy formation. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2003, 284, 579–588. [CrossRef]

- Sersic, J.L. Atlas de Galaxias Australes. Observatorio Astronomico, Cordoba, Argentina, 1968, 142p.

- Hunter, D.A.; Hunsberger, S.D.; Roye, E.W. Identifying Old Tidal Dwarf Irregulars. Astrophys. J. 2000, 542, 137–142. [CrossRef]

- Revaz, Y. The compactness of ultra-faint dwarf galaxies: A new challenge? Astronomy and Astrophysics 2023, 679.

- González-Samaniego, A.; Bullock, J.S.; Boylan-Kolchin, M.; Fitts, A.; Elbert, O.D.; Hopkins, P.F.; Kereš, D.; Faucher-Giguère, C.-A. Dwarf galaxy mass estimators versus cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 472, 4786–4796. [CrossRef]

- Lelli, F.F.; Verheijian, M. Evolution of dwarf galaxies: a dynamical perspective. Astronomy and Astrophysics 2014, 563, A27.

- Sawala, T.; Guo, Q.; Scannapieco, C.; Jenkins, A.; White S. What is the (dark) matter with dwarf galaxies? Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2011, 413, 659-668.

- Ferrara, A.; Tolstoy, E. The role of stellar feedback and dark matter in the evolution of dwarf galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2000, 313, 291–309. [CrossRef]

- Mateo, M. Dwarf galaxies of the Local Group. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 1998, 36(1), 435-506.

- Pickett, C.S.; Collins, M.L.M.; Rich, R.M.; I Read, J.; E Charles, E.J.; Martin, N.; Chapman, S.; McConnachie, A.; Savino, A.; Weisz, D.R. Mass Modeling the Andromeda Dwarf Galaxies: Andromeda VI and Andromeda XXIII. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2025. [CrossRef]

- White, S.D.M.; Rees, M.J. Core condensation in heavy halos: a two-stage theory for galaxy formation and clustering. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1978, 183, 341–358. [CrossRef]

- Tolstoy, E.; Vanessa, H.; Monica, T. Star-Formation Histories, Abundances, and Kinematics of Dwarf Galaxies in the Local Group. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2009, 47, 371-425.

- Bullock, J.S.; Michael, B.K. Small-Scale Challenges to the ΛCDM Paradigm. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2017, 55, 343-387.

- Mayer, L.; Mastropietro, C.; Wadsley, J.; Stadel, J.; Ben Moore, B. Simultaneous ram pressure and tidal stripping; how dwarf spheroidals lost their gas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 369, 1021–1038. [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Brandt, W.N.; Ni, Q.; Zhu, S.; Alexander, D.M.; Bauer, F.E.; Chen, C.-T.J.; Luo, B.; Sun, M.; Vignali, C.; et al. Identification and Characterization of a Large Sample of Distant Active Dwarf Galaxies in XMM-SERVS. Astrophys. J. 2023, 950, 136. [CrossRef]

- Lotz, J.M. The history of the evolution of dwarf galaxies. Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, 2003, Phd thesis 3080717, 160 p.

- Reaves, G. A catalog of dwarf galaxies in Virgo. The Astrophysical journal supplement series 1983, 53, 375-395.

- Caldwell, N. Dwarf Elliptical Galaxies in the Fornax Cluster. I. A Catalogue and Luminosity Function. The Astronomical Journal 1987, 94, 116-1125.

- Pace, A.B. The Local Volume Database: a library of the observed properties of nearby dwarf galaxies and star clusters. eprint arXiv 2024, 2411.07424, 1-13.

- McConnachie, A.W. THE OBSERVED PROPERTIES OF DWARF GALAXIES IN AND AROUND THE LOCAL GROUP. Astron. J. 2012, 144. [CrossRef]

- Kutlimuratov, S.; Nuritdinov, S.; Tadjibaev, I. Special summary catalog of dwarf galaxies in Universe up to distance 121 Mpc. Uzbek Journal of Physics 2020, 22-4, 203-217.

- Roychowdhury, S.; Chengalur, J.N.; Begum, A.; Karachentsev, I. D. Star formation in extremely faint dwarf galaxies. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2009, 397, 1435-1453.

- Cole, A.A.; Weisz, D.R.; Dolphin, A.E.; Skillman, E.D.; McConnachie, A.W.; Brooks, A.M.; Leaman, R. DELAYED STAR FORMATION IN ISOLATED DWARF GALAXIES:HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPESTAR FORMATION HISTORY OF THE AQUARIUS DWARF IRREGULAR. Astrophys. J. 2014, 795. [CrossRef]

- Richard, I.D.; Hajime, S.; Martin, J.W. Star-forming regions in blue compact dwarf galaxies. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1998, 295, 43-54.

- Leitner, S.N. ON THE LAST 10 BILLION YEARS OF STELLAR MASS GROWTH IN STAR-FORMING GALAXIES. Astrophys. J. 2012, 745. [CrossRef]

- Behroozi, P.S.; Wechsler, R.H.; Conroy, C. ON THE LACK OF EVOLUTION IN GALAXY STAR FORMATION EFFICIENCY. Astrophys. J. 2012, 762, L31. [CrossRef]

- Weisz, D.R.; Dolphin, A.E.; Skillman, E.D.; Holtzman, J.; Gilbert, K.M.; Dalcanton, J.J.; Williams, B.F. The Star Formation Histories of Local Group Dwarf Galaxies. I. Hubble Space Telescope/Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 Observations. The Astrophysical Journal 2014, 789, 1-23.

- Murray, S.D.; Lin, D.N.; Dong, S. Star formation in dwarf galaxies:Life in a rough neighborhood. Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Ostiker, San Francisco, 2004, 323, 409 p.

- Tillaboev, K.; Tadjibaev, I.; Otojanova, N. Empirical dependencies for irregular dwarf galaxies. Astronomical and Astrophysical Transactions 2025. 35, (inpress).

- Tillaboev, K.T.; Tadjibaev, I.U. Empirical dependencies for irregular and elliptical dwarf galaxies. Moscow University Physics Bulletin 2025, 80, (inpress).

- Tadjibaev, I.; Tillaboev, K.; Otojanova, N. Investigation of globular cluster of irregular galaxies. EUREKA: Phys. Eng. 2023, 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Nuritdinov, S.N.; Tadjibaev, I.U. Globular Star Cluster Systems Around Galaxies. I. Search for Statistical Relationships. Astrophysics 2014, 57, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Kutlimuratov, S.; Otojanova, N.; Tadjibaev, I.; Tillaboev, K. A study of the dynamic evolution of spherical gravitating systems. EUREKA: Phys. Eng. 2024, 3–12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).